Esslingen Branch

Roger P.Minert, “Esslingen Branch,” in Under the Gun: West German and Austrian Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 413–420.

The city of Esslingen had 48,732 inhabitants in the year 1939. [1] Six miles east of Stuttgart, it was the home of the second-largest LDS branch in the Stuttgart District at the time. Of the 117 members, twenty-seven were priesthood holders. Under branch president Karl Zügel, all programs of the Church were functioning as the war approached.

According to the branch directory, Brother Zügel’s counselors were Kurt Kirsch and Gottlob Maier. Johann Knödler led the Sunday School, Albert Heinemann the YMMIA and Paula Krieger the YWMIA. Friederika Heinemann was the president of the Primary and Lina Kugler the president of the Relief Society. Brother Kirsch was the Stern magazine representative and Brother Maier directed genealogical research among branch members. [2]

When the war began in September 1939, the branch was holding meetings in a house at Plochingerstrasse 4 in Esslingen. Sunday School began at 10:00 and sacrament meeting at 7:00 p.m. Mutual met on Tuesdays at 8:00 p.m. and the Primary on Wednesdays at 6:00 p.m., followed by Relief Society at 8:00. The genealogical study group met on the third Tuesday of the month at 8:00 p.m.

| Esslingen Branch [3] | 1939 |

| Elders | 9 |

| Priests | 6 |

| Teachers | 3 |

| Deacons | 9 |

| Other Adult Males | 22 |

| Adult Females | 58 |

| Male Children | 7 |

| Female Children | 3 |

| Total | 117 |

“I can remember the beginnings of the war very well,” recalled Ilse Neff (born 1929):

I was ten years old, and we lived in a street where everybody knew their neighbors very well. One night, we heard a loud noise outside, and we woke up. My parents went to see what was going on, and I was terribly scared. I saw a group of men knocking on everybody’s door and windows. I asked my father what that meant, and he explained to me that those men were soldiers and that they were looking for men to draft for a possible war. That scared me. . . . One night, we came back from helping my mother’s friend with her canning. Suddenly, we heard Hitler’s voice on the radio saying that beginning at [4:45 a.m.] Germany was shooting back. I can still hear that in my mind today. That was September 1, 1939. [4]

Ilse recalled that the meeting rooms at Plochingerstrasse were confiscated early during the war because the building had belonged to a Jewish family named Moses. Several homes became available for meetings during the war, but Ilse stated that there were no interruptions in the meetings when the locations changed.

Walter Tischhauser (born 1935) described the meeting rooms in the Moses building in these words: “It was quite a large building that was four or five stories high. The rooms were also large—a little bit like small halls. This building belonged to the Moses family, who were Jewish. We called the building the ‘Moses house.’ [5]

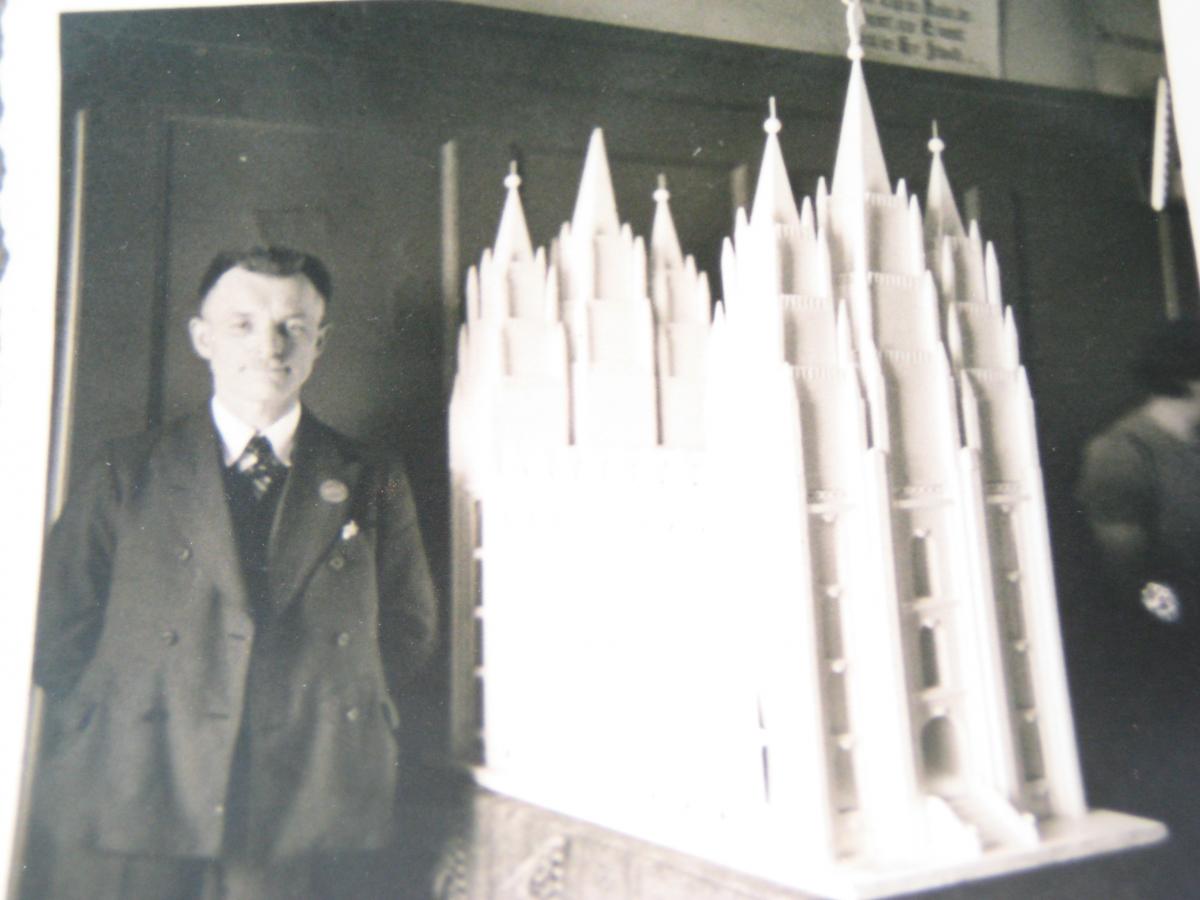

Fig. 1. Anita Neff’s father with his model of the Salt Lake Temple. (A. Neff Bauer)

Fig. 1. Anita Neff’s father with his model of the Salt Lake Temple. (A. Neff Bauer)

The walk to church took forty-five minutes for Lina Tischhauser and her children. Her husband was not a member of the Church, but he did not oppose their desire to attend meetings. Daughter Elsbeth (born 1932) remembered walking home after Sunday School, then back again for sacrament meeting in the evening. That meant a total of three hours on the way. “I think there were about fifty people in the meetings in those days,” she said. [6]

Fig. 2. The living room of the Oppermann home was one of several locations of branch meetings during the war. (Oppermann family)

Fig. 2. The living room of the Oppermann home was one of several locations of branch meetings during the war. (Oppermann family)

The Stuttgart District general minutes written by president Erwin Ruf include reports of his many visits among the Saints in Esslingen. His record of January 23, 1940, indicated that the meetings that Sunday had to be cancelled due to a lack of coal to heat the room. [7] A few months later (June 3), he wrote the following: “Attended the Sunday School and the fast meeting of the Esslingen Branch. Today the members of the Feuerbach and Stuttgart Branches were fasting and praying that the Esslingen Branch would be successful in locating new rooms to meet in.” [8] A month later, the meetings were still being held in the home of the Fingerle family while the search continued. It was not until December that a decision was made to designate the Fingerle home as the official venue for branch meetings: “[Erwin Ruf] visited the Esslingen Branch fast meeting and offered the dedicatory prayer on the rooms in the Fingerle home where meetings will be held.” [9]

The hostess, Bertha Pauline Fingerle, was Walter Tischhauser’s grandmother. He described the branch’s new location as follows:

On the main floor of her house, she emptied the living room in which up to twenty-five people could be accommodated. The classes for Sunday School were taught in smaller rooms in the house, for example the bedrooms. I remember sitting on the bed and being taught. This house was located at Mellinger Strasse 12a. During this time, the branch was not larger than twenty-five people usually.

Early in the war, an incident occurred that convinced some Church members in Esslingen that Germany’s government was willing to hurt its own citizens. Young Ilse Neff recalled her friendship with Helene Zügel, one of the ten children of the branch president. Helene was mentally retarded but was not socially inept. Ilse told this story:

The government ordered the family to send Helene to an institution, since they wanted to help her (or so they said). But one day, the family received a letter describing her sudden death. We all knew how she died and that it hadn’t been a sudden death. She must have been about [eighteen] years older than me. She could communicate well and would sometimes come to visit us in our home. She liked talking to my mother, although she had to walk a long way to get to our home from where she lived. She knew so many things. One time, she even explained to me what the Millennium would be like. I was so impressed about the way she explained it to me. She also sang Church hymns with me.

Fig. 3. A prewar photograph of the Esslingen Branch. (A. Neff Bauer)

Fig. 3. A prewar photograph of the Esslingen Branch. (A. Neff Bauer)

Helene was likely a victim of the heinous euthanasia program carried out by the government. The official cause of her death was given as “septic angina.” She was twenty-nine years old.

The district general minutes mention the deaths of several Esslingen Saints, notably Erwin Riecker, who was killed in Russia in March 1942. A memorial service was held in the branch for him. [10] He was, of course, only one of several men of this branch to give their lives for Germany.

Elsbeth Tischhauser recalled how the army put pressure on her brother Rudolf to join.

Every month, people from the [Nazi] party came and told my parents that my brother would be the perfect soldier because he was so tall. And they also said that if we won the war, he would have the best life possible. After all these things, my mother eventually said to my brother Rudolf that he should go. For us, it was a horrible time when my brother left, and we had to realize that many of the soldiers were killed in battle.

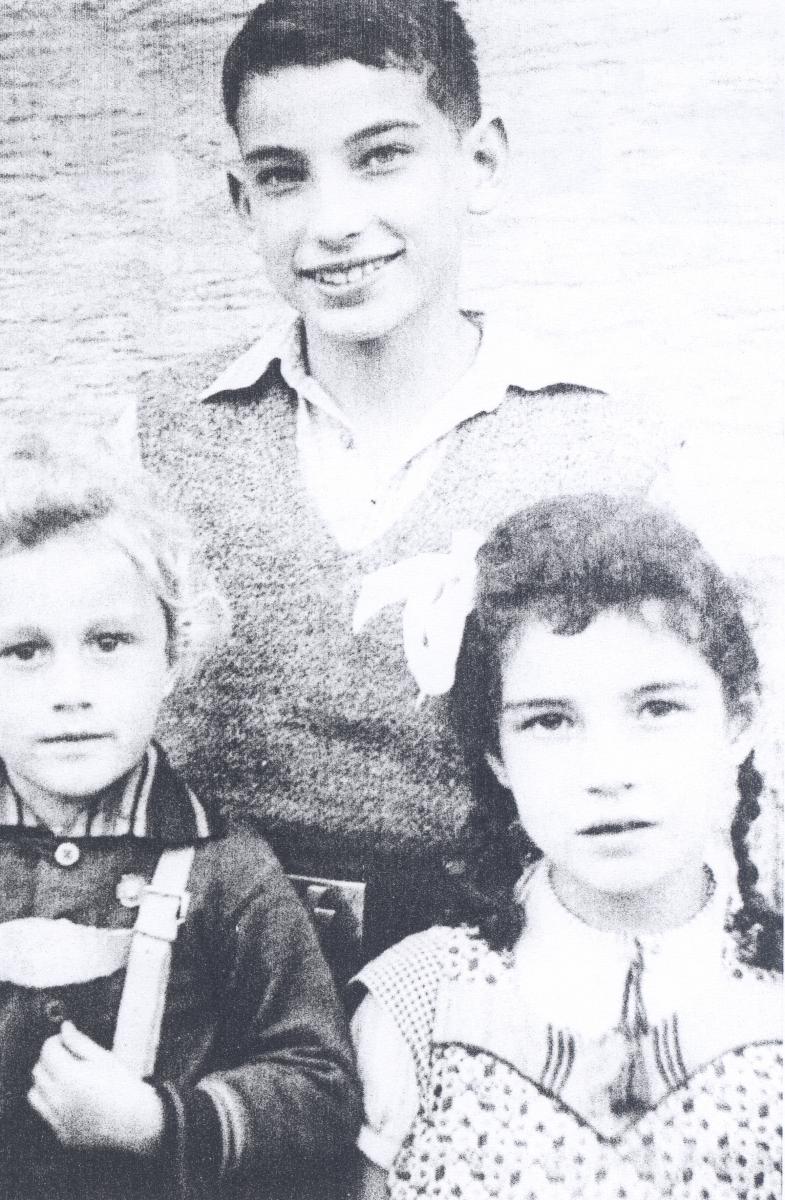

Fig. 4. Three of the eight Tischhauser children. (A. Neff Bauer)

Fig. 4. Three of the eight Tischhauser children. (A. Neff Bauer)

Esslingen was spared great damage, despite the fact that the city is so close to Stuttgart and was home to a railroad repair facility. According to Ilse Neff, “We didn’t have many air raids, but when we went to bed at night, we each had a chair next to the bed with our clothes on it to get dressed fast. We also had a small bag to carry with us to the basement. Sometimes, there was an hour between the first sirens going off and the all-clear signal.” A girl of faith, Ilse was impressed when she heard that branch president Karl Zügel and his counselor Gottlob Maier had gone up the hill above the city to offer a prayer. They petitioned God to protect that city and the Saints who lived there.

In 1943, Walter Tischhauser was planning to be baptized, but a minor crisis of faith occurred when he turned eight, as he described it:

My aunts (with last name Fingerle) were my teachers in the Church, and I loved them very much. When I was eight years old, I wanted to be baptized because that is what I had always been taught in Church. My mother wrote of my desires in a letter to my oldest brother, who was then serving in the Arbeitsdienst in the Rhineland. He wrote back wondering why I wanted to be baptized since he thought I always wanted to become a great Hitler boy. Then he explained that one could not be a good Mormon boy and at the same time be a good Hitler boy. That is when I decided to not get baptized. All of my family members who were in the Church were shocked, but I was convinced that I had made the right choice.

Walter did not turn his back on the Church for long, as he explained: “I was baptized when I was eleven years old in 1946. The war was over by then, so I could concentrate on becoming a good Mormon boy again.”

Regarding the challenge of finding enough food to eat during the war, Walter made this comment:

Although we were quite a large family, we never had to go without the basic food groups. I remember that I never had to be hungry. It was more difficult for us to find enough clothing—especially shoes. Those things we would only get with ration coupons. My brother had to serve in the military and sent the cigarette coupons home. Nobody in our family smoked, so we could exchange the smoking cards for something else.

Elsbeth Tischhauser recalled how the city government had ponds dug around town so that water for fighting fires after air raids would always be available. In about 1944, her father sent her to the local pond several times to remove waste with a bucket. On one such occasion, she was kneeling by the pond when she heard airplanes approaching:

I was wondering why there was no alarm and thought that they must be German planes. But they started shooting right away. I kept on working. A window in the house next to me opened, and a woman shouted to me that I should get into her house as fast as possible. The planes aimed directly at me. I ran down into the basement, but when it was over, the people had a hard time getting me to come out again because I was shaking so much. If I didn’t have a thousand angels next to me that day, I wouldn’t have survived.

Entertainment for teenagers was a challenge, Ilse Neff recalled. “I remember one Heinz Rühmann movie that was in the theaters, and my mother allowed me to go. We had to go three different times until we could watch the entire movie because an air raid happened during the first two showings. We had to go into the basement of the movie theater when the alarm sounded.”

Young Hans Fingerle (born 1940) was just old enough to recall being with his father for a short time before Ludwig Fingerle (born 1913) was drafted into the air force. In his father’s absence, Hans had plenty of experiences to pass the time. He recalled this one aspect of life during the last years of the war when Germany was losing on many fronts:

We had refugees stay with us in our apartment even during the war. One day, somebody from the housing office came and told us that we had too much room to spare and that they would send people to stay with us. We did not know any of them but they lived in one of the rooms of our apartment with four people. They spoke a different dialect, but I do not know if they were from the east. One of the boys in the family was my age, so we played a lot together. [11]

Fig. 5. Ludwig and Margarette Fingerle with their son Hans in about 1943. (H. Fingerle).

Fig. 5. Ludwig and Margarette Fingerle with their son Hans in about 1943. (H. Fingerle).

Hans’s father, Ludwig (born 1913) had been drafted into the air force and, like so many other soldiers on both sides of the conflict, would rather have been home. One can sense the longing in these words written to his wife on February 11, 1945, from Ober Ursel, near Frankfurt:

I hope you are all well and happy. How did you spend your birthday? I am still waiting for a letter from you. Your last letter was written on January 20. Since then, so much has happened that I don’t know which of it would most interest you. One thing: the next few weeks will determine what will happen to our people and our country. May the Lord have mercy on us. We must pray that our enemies do not overcome us. Now I understand that in Joseph Smith’s vision, he had to turn away his eyes when he saw the misery that would befall mankind. . . . May God protect you and all of our loved ones. [12]

The trials of a mother caring for her children during the absence of her soldier husband are reflected clearly in the letter written by Margarete Fingerle to Ludwig on April 8, 1945—just one month before the end of the war:

You have probably heard that the front moves closer and closer to us. But we won’t be discouraged or give up. We maintain the hope that we will stay healthy and see you again. How beautiful the world could be; the flowers are beginning to blossom around here and I am with you in my thoughts, my dear. . . . I am so glad that we had time together to travel and see some wonderful places. Will we ever be able to do that again? . . . I have to go now; it’s 11 o’clock. How we all are awaiting the day when we will see you again.

Hugs and kisses from your dear Gretel [13]

Sister Fingerle would have to wait until the next life to see her husband again. The letter was returned as undeliverable. The chaos that reigned around Berlin in the last days of the war made it impossible for army postal officials to find Ludwig Fingerle.

Soldier Rudolf Tischhauser was a member of the Church, but in one of his last letters written as the end of the war loomed, he told his mother that he would rather shoot himself than be taken prisoner by the Russians. Neither scenario was his fate; he was killed in an artillery barrage. By the time the war ended, Lina Tischhauser had lost two sons and two brothers, as her daughter Elsbeth explained:

My brother Ludwig was killed in the war in December of 1944. Rudolf was later killed in April 1945. My uncle died around April 20, 1945. And my oldest brother Otto Fingerle died the day that the war was declared lost. He was shot by partisans. It was such a difficult time for all of us, especially for my mother. [14]

Ilse Neff recalled how the American invaders appeared one day in the spring of 1945 on the hills above Esslingen. When the city’s mayor initially refused to surrender the city, the enemy threatened to bombard the town. Fortunately, several influential citizens conducted talks with both sides and were able to motivate the mayor to renounce his call for resistance. The city surrendered without a fight, and the people were spared. According to Ilse, the Americans were merciful to the populace, but the same could not be said of the French: “It was a different atmosphere. . . . We were a little scared of the Africans who served among the French troops. We had never before seen so many in one group. Especially the women were afraid.” Fortunately, the Esslingen Branch members did not suffer much at the hands of the conquerors.

Little Hans Fingerle described an experience he had with the occupation forces:

I was not afraid of the black soldiers I saw. One time, I was with a friend from kindergarten, and we saw a pickup truck with American soldiers. I thought it was funny that they had a broom on the side of their truck. When the truck passed us, I pointed to the broom, and we both laughed. All of sudden, somebody hit me in the rear, and when I turned around, I saw a black soldier standing there. He must have thought that I had laughed about him. That was my first encounter with a soldier that was not white.

Ludwig Fingerle was killed in the defense of Berlin on April 25, 1945, but his wife did not have proof of his fate until a letter written by a comrade arrived in August 1948. Horst von Glasenapp returned from a POW camp in the Soviet Union that summer and fulfilled his self-imposed duty of writing to Margarete Fingerle. He explained how his antiaircraft battery, which included Corporal Ludwig Fingerle, had moved in several directions through the capital city, trying to avoid a direct confrontation with the invading Red Army. Eventually, the men found themselves at the north edge of the Tiergarten (Berlin’s equivalent to New York City’s Central Park). Von Glasenapp’s very detailed letter includes the following description of the events of evening of April 25:

We expected to be attacked by the Russian night fighters at any moment. When we heard the motors of the planes and saw the illumination flares they dropped, I ordered my unit to stop and to take cover as fast as possible. We were across the street from Bellevue Palace. We sensed instinctively the impending danger, but the first bombs fell even before we had found safety in the trenches. At dawn the next day, April 26, we survivors buried our three comrades who were killed, including Ludwig Fingerle, under the trees of the Tiergarten, across the street from Bellevue Palace. [15]

Without the letter of this kind commanding officer, the fate of Ludwig Fingerle may well have remained a mystery.

Lina Tischhauser had raised her children in the faith before and during the war, but her husband was not a member of the Church and did not encourage his children to be baptized. However, some of his misgivings about religion were apparently resolved after Germany’s catastrophic defeat, as his son Walter recalled:

My father always believed very strongly in the [Hitler] regime and the system. When the war was over, my father basically broke down and had to reevaluate everything that he believed in. Especially because he found out what had really happened in connection with the Jews, for example. He stated that he felt so used and betrayed that he would never believe and trust anybody again. During the [Third Reich], he also never wanted to hear anything about the Church. But because there were so many children in our family, we always got extra support from the Church (food, clothing, etc.) after the war. The branch presidency then told my father that the Church had helped his family so much—now would be the time to be baptized. Even my mother testified that the blessings had been the biggest help getting through the war.

Richard Tischhauser was baptized in 1948.

The city of Esslingen was indeed fortunate to emerge from the war nearly unscathed. Official city records show that only forty-seven civilians and seventy military personnel from Esslingen lost their lives and that only 3 percent of the structures (all of them in suburbs) were destroyed. The war ended for the people of Esslingen when the French arrived in April 1945. The branch membership had been reduced significantly, but the meetings continued, and the Saints in that city looked forward to a life in a peaceful Germany.

In Memoriam

The following members of the Esslingen Branch did not survive World War II:

Marie Kathrine Bäuerle b. Esslingen, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, 24 Aug 1863; dau. of Jacob Bäuerle and Sophie Karle; bp. 2 Mar 1910; conf. 2 Mar 1910; d. pneumonia 20 Oct 1944 (FHL microfilm 68807, book 2, no. 301; IGI)

Otto Alfred Brändle b. Marbach, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, 18 Mar 1918; son of Rudolf Brändle and Emma Walker; bp. 23 Dec 1928; conf. 23 Dec 1928; noncommissioned officer; k. in battle Orschiza, Ukraine, 20 Sep 1941 (FHL microfilm 68807, book 2, no. 471; FHL microfilm 25728, 1930 census; IGI; www.volksbund.de)

Lina Frida Rosa Brodbeck b. Esslingen, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, 9 Jun 1907; dau. of Paul Brodbeck and Frida Claus; bp. 6 Apr 1930; conf. 6 Apr 1930; m. Esslingen 24 Oct 1936, Eugen Vollmer; d. throat and lung ailment Esslingen 11 Aug 1944 (FHL microfilm 68807, book 2, no. 574)

Bernhard Johannes Fingerle b. Esslingen, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, 29 Jul 1914; son of Christian Johann Fingerle and Barbara Ulmer; bp. 9 Aug 1922; conf. 9 Aug 1922; ord. deacon 7 Dec 1930; ord. teacher 14 Jul 1935; ord. priest 19 Jul 1942; m. 7 Dec 1943; sergeant; k. in battle Michelbach, Alsace-Lorraine, France, 7 Dec 1944; bur. Cernay, France (FHL microfilm 68807, book 2, no. 252; FHL microfilm 25766; 1930 and 1935 censuses; IGI, AF; www.volksbund.de)

Ludwig Erwin Fingerle b. Esslingen, Neckar, Württemberg, 15 May 1913; son of Christian Johann Fingerle and Barbara Ulmer; bp. 14 Jul 1921; m. Esslingen 3 Jul 1937, Margarete Alma Kirsch; 2 children; k. in battle Berlin 25 Apr 1945; bur. Berlin 26 Apr 1945 (H. v. Glasenapp)

Otto Bernhard Jakob Fingerle b. Esslingen, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, 28 Nov 1901; son of Christian Johann Fingerle and Bertha Pauline Kiesel; bp. 30 Aug 1911; conf. 30 Aug 1911; ord. deacon 5 Aug 1923; m. Esslingen, Neckar abt 1921, Lina Ahles; k. in battle Berlin, 8 May 1945 (FHL microfilm 68807, book 1, no. 828; FHL microfilm 25766; 1930 and 1935 censuses; IGI, AF)

Albert Heinemann b. Jebenhausen, Donaukreis, Württemberg, 30 Oct 1906; son of Carl Heinemann and Julie Nothdürft; bp. 31 Oct 1924; conf. 31 Oct 1924; ord. deacon 7 Feb 1926; ord. teacher 15 Aug 1926; ord. priest 6 Dec 1936; m. 16 Feb 1929, Friederike Maier; at least three children; k. in battle Russia, 13 Feb 1944 (FHL microfilm 68807, book 2, no. 93; FHL microfilm 162780; 1930 and 1935 censuses; IGI)

Hans Heinemann b. Oberesslingen, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, 5 Oct 1917; son of Karl Heinemann and Julie Nothdürft; bp. 18 Jan 1926; conf. 18 Jan 1926; noncommissioned officer; k. in battle San. Kp. 1/

Frida Klaus b. Wäldenbronn, Esslingen, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, 25 Jul 1879; dau. of Gottlieb Klaus and Christine Clauss; bp. 28 Aug 1943; conf. 28 Aug 1943; m.—— Brodbeck; d. dysentery 17 Sep 1944 (FHL microfilm 68807, book 2, no. 754; IGI)

Walter Knödler b. Stuttgart, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, 19 May 1921; son of Johann Knödler and Karoline Bauer; bp. 7 Sep 1929; conf. 7 Sep 1929; ord. deacon 6 Dec 1936; radio operator; k. in battle South Tunisia 23 or 28 Mar 1943; bur. Bordj-Cedria, Tunisia (FHL microfilm 68807, book 2, no. 392; FHL microfilm 271380; 1930 and 1935 censuses; IGI; www.volksbund.de)

Maria Theresia Merkt b. Spaichingen, Schwarzwaldkreis, Württemberg, 18 Aug 1866; dau. of Sylvester Merkt and Josephine Merkt; bp. 2 Jun 1924; conf. 2 Jun 1924; m. Wilhelm Friedrich Krötz; d. asthma 24 Dec 1940 (FHL microfilm 68807, book 2, no. 5; FHL microfilm 271381; 1930 and 1935 censuses; IGI)

Erwin Eugen Riecker b. Mettingen, Esslingen, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, 8 Dec 1917; son of Eugen Riecker and Ernestine Margarete Fingerle; bp. 23 Dec 1928; conf. 23 Dec 1928; ord. deacon 7 Jul 1935; lance corporal; k. in battle Ssokorowo, Russia, 27 Mar 1942 (FHL microfilm 68807, book 2, no. 8; FHL microfilm 271403; 1930 and 1935 censuses; IGI; www.volksbund.de)

Elise Sprenger b. Wetzikon, Zürich, Switzerland, 15 Oct 1868; dau. of Johannes Sprenger and Agnes Eugster; bp. 11 Apr 1924; conf. 11 Apr 1924; m. —— Kurle; missing as of 20 Nov 1946 (FHL microfilm 68807, book 1, no. 926; FHL microfilm 271382; 1930 and 1935 censuses; IGI)

Wilhelmine Stierle b. Stetten, Echterdingen, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, 2 May 1872; dau. of Andreas Wilhelm T. Stierle and Rosine K. Gehr; bp. 18 Jul 1914; conf. 18 Jul 1914; m. Stetten, 10 Dec 1893, Franz Smyzcek; 5 children; d. asthma Esslingen, 6 or 13 Oct 1941 (FHL microfilm 68807, book 2, no. 693; IGI, AF)

Walter Rudolf Tischhauser b. Stuttgart, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, 23 Aug 1926; son of Richard Karl Tischhauser and Lina Rosa Fingerle; bp. 23 Jul 1939; conf. 23 Jul 1939; infantry; k. in battle Kämpenau near Gotenhafen, 5 Apr 1945 (CHL microfilm 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, all-mission list 1943–46, pp. 186–87, district list pp. 218–19; FHL microfilm 68807, book 2, no. 206; www.volksbund.de; E. Tischhauser Ertel, AF, PRF)

Helene Elsa Zügel b. Rudersberg, Jagstkreis, Württemberg, 21 Feb 1911; dau. of Karl Gottlob Zügel and Ernestine Wenninger; bp. 22 Jun 1919; conf. 22 Jun 1919; d. septic angina (suspected euthanasia) 16 Dec 1940 (FHL microfilm 68807, book 2, no. 306; FHL microfilm 245307, 1930 and 1935 censuses; IGI)

Walter Nephi Karl Zügel b. Esslingen, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, 9 May 1923; son of Karl Gottlob Zügel and Ernestine Wenninger; bp. 25 Jun 1931; conf. 25 Jun 1931; ord. deacon 21 May 1939; k. in battle near Metz, Alsace-Lorraine, France, 9 Nov 1944; bur. Andilly, France (FHL microfilm 68807, book 1, no. 814; FHL microfilm 245307; 1930 and 1935 censuses; IGI; www.volksbund.de)

Notes

[1] Esslingen city archive.

[2] West German Mission branch directory, 1939, CHL LR 10045 11.

[3] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” 257, CR 4 12.

[4] Ilse Anita Neff Bauer, interview by Jennifer Heckmann in German, Esslingen, Germany, August 23, 2007; unless otherwise noted, summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[5] Walter Richard Tischhauser, telephone interview with Jennifer Heckmann in German, January 20, 2009.

[6] Elsbeth Tischhauser Ertel, interview by Jennifer Heckmann in German, Langen, Germany, August 14, 2006.

[7] Stuttgart District general minutes, 162, CHL CR 16982 11.

[8] Ibid., 169.

[9] Ibid., 177.

[10] Ibid., 199.

[11] Hans Ludwig Fingerle, interview by the author in German, Hermannsweiler, Germany, August 20, 2008.

[12] Ludwig Erwin Fingerle to Margarete Kirsch Fingerle, February 11, 1945; trans. the author; used with the permission of Hans Fingerle.

[13] Margarete Kirsch Fingerle to Ludwig Erwin Fingerle, April 8, 1945; trans. the author; used with the permission of Hans Fingerle.

[14] Lina also lost a half-brother. Four of the five men were members of the Church.

[15] Horst von Glasenapp to Margarete Fingerle, August 11, 1948; trans. the author; used with the permission of Hans Fingerle.