Essen Branch

Roger P.Minert, “EssenBranch,” in Under the Gun: West German and Austrian Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 353–363.

Located essentially in the center of the Ruhr industrial district in northwest Germany, the city of Essen was long famous for the gigantic Krupp Stahlwerke. The company had produced military equipment for decades before the start of World War II in September 1939. Essen is located on the north bank of the Ruhr River and had 664,523 inhabitants at the time. [1]

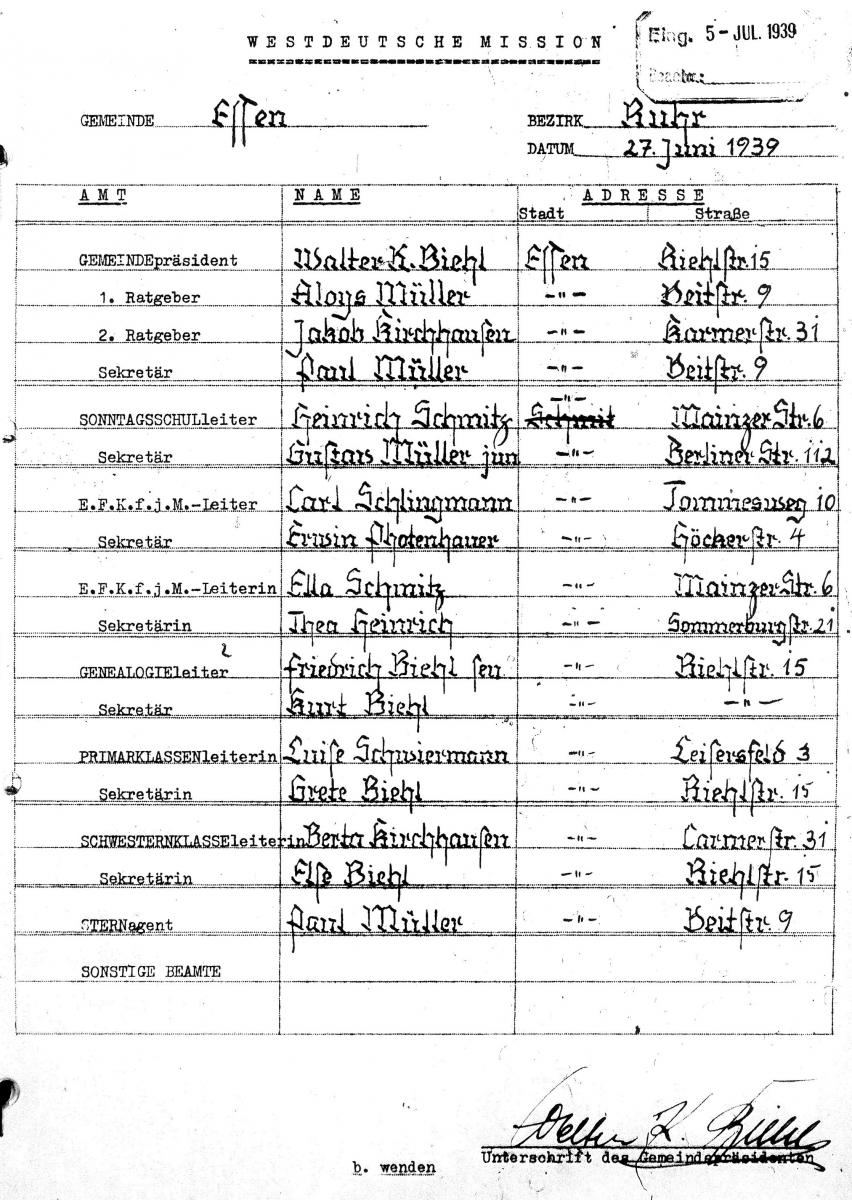

The largest branch in the Ruhr District of the West German Mission, the Essen Branch had 162 registered members. With so many members, the branch leadership directory dated June 27, 1939, shows all callings occupied. [2] The branch president at the time was Walter Biehl, a member of one of the largest and most faithful families of Latter-day Saints in Germany. Walter’s brother, Friedrich, was at that time the president of the Ruhr District and was called in September to lead the entire mission.

| Essen Branch [3] | 1939 |

| Elders | 16 |

| Priests | 6 |

| Teachers | 8 |

| Deacons | 12 |

| Other Adult Males | 28 |

| Adult Females | 82 |

| Male Children | 5 |

| Female Children | 5 |

| Total | 162 |

The branch directory was filled out by Walter Biehl and shows his beautiful handwriting, a re-creation of the Fraktur style used mostly in printing. The list shows first counselor Aloys Müller and second counselor Jakob Kirchhausen. Other leading men were Heinrich Schmitz (Sunday School), Carl Schlingmann (YMMIA), Paul Müller (Der Stern representative), and Walter’s father, Friedrich Biehl Sr. (genealogy). Leading women in the branch were Berta Kirchhausen (Relief Society), Luise Schwiermann (Primary), and Ella Schmitz (YWMIA).

When the war began, the branch was holding its meetings in rooms rented since the 1920s in a Hinterhaus behind the building at Krefelderstrasse 27. Karl Müller (born 1922) provided this description:

The building looked like a barrack. We walked up some wooden stairs, and then we entered the meeting room. The classrooms were located on the main floor. We also had a podium. I cannot remember that there were any pictures on the wall in either of those rooms. There must have been about thirty people in attendance each Sunday. We sat on chairs, not on benches. When I was the Sunday School secretary, I had my own table at the front of the room. [4]

Fig. 1. Front page of the Branch directory showing Walter Biehl’s artistic handwriting. (Church History Library)

Fig. 1. Front page of the Branch directory showing Walter Biehl’s artistic handwriting. (Church History Library)

Artur Schwiermann (born 1927) recalled that the words “The Glory of God Is Intelligence” were painted on the wall behind the podium. Among those who attended Sunday School were several children whose families did not belong to the Church (which was the case in most branches in Germany). He explained the presence of those children in Primary as well: “Everybody in the neighborhood knew we were members of the Church. The children would say, ‘Frau Schwiermann, when can we go to Primary?’ There were six or seven whom she took along to Primary.” [5]

The Essen Branch enjoyed a most rare feature in their meeting rooms—one of only three baptismal fonts in the entire mission. The Essen Branch history gives the following description:

There was even a baptismal font located next to the Relief Society room. For each baptismal ceremony the water had to be heated in large tin containers. Cold water was added by means of a hose. However, there was no way to drain the basin. . . . The sisters scooped the water out after each ceremony, using various containers. In the years prior to the construction of the font, baptisms had been carried out in the Ruhr River or in the Friedrich Bathhouse. [6]

Missionary Erma Rosenhan from Salt Lake City observed a baptism in Essen on Sunday, March 19, 1939, and recorded the event in her diary:

Up at 6 a.m. . . . By 7:15 I was in the Branch to see the baptisms. There were quite a few people there. There was a regular program given. The water was heated by stoves and there were pine needle boughs all around the font to make it look nice. There were 3 children and one adult (man) baptized. [7]

Willi Ochsenhirt (born 1928) was also baptized in that font. In addition, he recalled a picture of Christ’s baptism showing the Holy Ghost descending in the form of a dove. That picture hung on the wall behind the podium. There was enough room on the rostrum for a large choir. “I remember once that we had a choir competition with the Herne Branch,” Willi explained. “They won because they had a spectacular soloist.” [8]

Branch members had several opportunities each week to go to church. Sunday School began at 10:00 a.m. and sacrament meeting at 6:00 p.m. The genealogy class met on the second and fourth Sundays of the month at 8:45 a.m. On Tuesdays, Primary began its meeting at 5:30 p.m., and that was followed by Mutual at 7:30 p.m. The Relief Society sisters and the priesthood holders gathered on Wednesdays at 7:30 p.m. in separate rooms.

Sister Rosenhan’s comments about the Essen Branch include this comical assessment of the Primary children: “Sunday, August 13, 1939: Had to teach the [Primary] ‘B’ class again this morning. They were little ‘devils’ and certainly angered me.” Other comments reflect the fear of approaching war: “Wednesday, August 23, 1939: Relief Society and choir practice. Because of having to darken [blackout] everything we couldn’t have choir practice last night.”

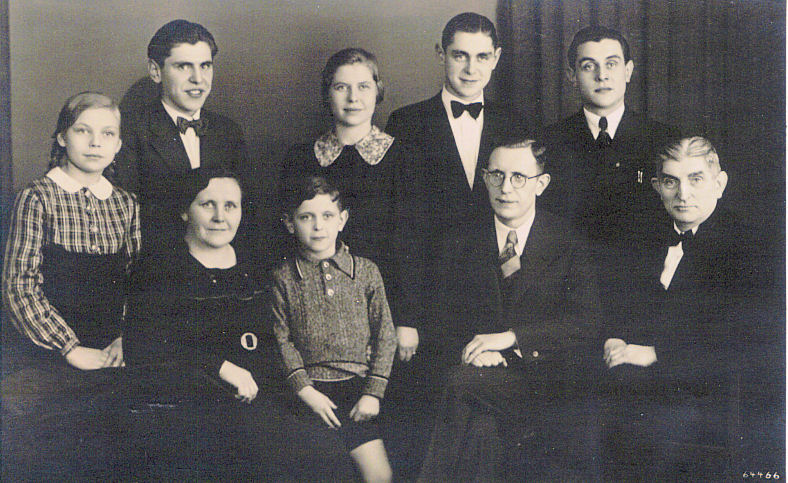

Fig. 2. The Biehlfamily in Essen. Branch president Walter Biehlis in the back row, far right. Mission supervisor Friedrich is seated next to his father. (M.Biehl Haurand)

Fig. 2. The Biehlfamily in Essen. Branch president Walter Biehlis in the back row, far right. Mission supervisor Friedrich is seated next to his father. (M.Biehl Haurand)

Fig. 3. The Essen Branch meeting rooms were large but modest. Note the photograph of Church President Heber J. Grant. (G. Blake)

Fig. 3. The Essen Branch meeting rooms were large but modest. Note the photograph of Church President Heber J. Grant. (G. Blake)

One of the saddest events in the life of the Essen Saints was the departure of Sister Rosenhan on August 25, 1939 (her mission companion, Sister Heibel, was a German citizen who remained in Essen). Sister Rosenhan was assisted by president Walter Biehl in transporting her trunk to the railroad station for the trip to Amsterdam. As they went back and forth across the city in response to contradictory instructions from harried railroad officials, they stopped at Walter’s home to say good-bye to his family. Sister Rosenhan wrote this description of the situation:

Sister Biehl was crying. While [her husband] was helping me get away. He had received his military summons and had to report that very day. Pres. Biehl slumped back in the taxi and said he would not go to work that day. I gave him most of the money I had. . . . I can still see the faces of my companion and Pres. Biehl as the train left. We all cried. . . . Pres. Biehl called [the mission home in] Frankfurt to tell them that I had left.

Fig. 4. Members of the Essen Branch in 1939. (M. Biehl Haurand)

Fig. 4. Members of the Essen Branch in 1939. (M. Biehl Haurand)

Friedrich Ludwig Biehl was released as the supervisor of the West German Mission and was succeeded by Christian Heck of Frankfurt on December 31, 1939. His personal history is very short from the day he entered the military and reads as follows:

I was drafted into the army on 14 December 1939 so I could no longer function as the mission leader, but I kept the calling [for two more weeks]. I came to the infantry in Bromberg [Posen]. During the month of March I went to Kleve, West Germany. Then I was in the campaign in Holland, Belgium, and France. In April 1941, I was back in Germany. From Marienburg, West Prussia, we marched to the Eastern border and then with the beginning of the Eastern campaign we went to Lithuania, Estonia and Russia. We started combat with the Russians on 23 July 1941. It would be too difficult to write about the afflictions, sufferings and distress that I experienced from these [campaigns]. [9]

Walter Konrad Biehl (born 1914) was a copy editor and had married just three months before the war began. In his detailed autobiography, he reported being stationed in many locations on the Western Front: in the Netherlands, in Belgium, in Luxembourg, in France near the Maginot Line, and in several towns in western Germany not far from his own home. He traveled on furloughs to Tilset in East Prussia, the home of his wife, Gertude. He rejoiced in every opportunity to see his daughter, Angelika, who was born on April 10, 1940. Whenever and wherever possible, he attended church meetings.

Margaretha Biehl (born 1927) recalled the pressure put on her by the leaders of the League of German Girls. They instructed her to report on Sundays for activities or assignments. “They would give us a permission form to take to our parents. So I came home and I showed it to my father and he said, ‘Sunday I take my children to church and nothing else. You cannot go.’ And I prayed every day, because I knew that the government could put my father in a concentration camp if he interfered with something like this. And I just didn’t know what to do.” [10]

Margaretha also recalled the propaganda films she and her classmates were required to watch. They all went to the movie theater on Mondays to see films showing how Hitler’s government had made everything better. One of the films showed the people in the Netherlands welcoming the German invaders as liberators. “I can still see that in my mind,” she said.

“We lived right on a plaza across from an entrance to a park in a very visible location,” recalled Johannes Biehl (born 1929), “so my dad was assigned to display a large swastika flag. But he often forgot and wasn’t very conscientious about it. He was visited once by a representative of the Gestapo who told him, ‘Sir, if you forget again to display the flag, you will be in trouble.’ And of course, now we know what he meant by trouble.” [11]

Johannes recalled other aspects of life in Nazi Germany:

The [Hitler Youth and League of German Girls] collected money quite frequently, sometimes on national holidays. They used metal containers and rattled them and begged people going by to donate. I remember that my Dad always responded by saying that he had already given to the church. They even came into the apartment building to collect, but my father never gave them any money.

Regarding political matters in the branch, Johannes recalled:

In our sacrament meetings we had a bit of turmoil. I remember one brother who was a Nazi at heart and prayed once in a while that Germany would be victorious. Eventually, he was not asked to pray anymore. On the other hand, there was a brother who prayed that the church would be victorious—not necessarily that Hitler would get out of the way, but it was clear that he was opposed to Hitler’s government.

Some of the earliest members of the Essen Branch were the family of Friedrich and Emilie Ochsenhirt. They had arrived in the city from Darmstadt, Hesse, during World War I when Friedrich was assigned to work as a blast furnace stoker at Krupp. When Willi was born in 1928, the family was complete with twelve children. It was a serious challenge for Brother Ochsenhirt to provide for his family, and he did many odd jobs on weekends and holidays. When the war began, Friedrich was over seventy years of age, and several of his children were still living at home. [12]

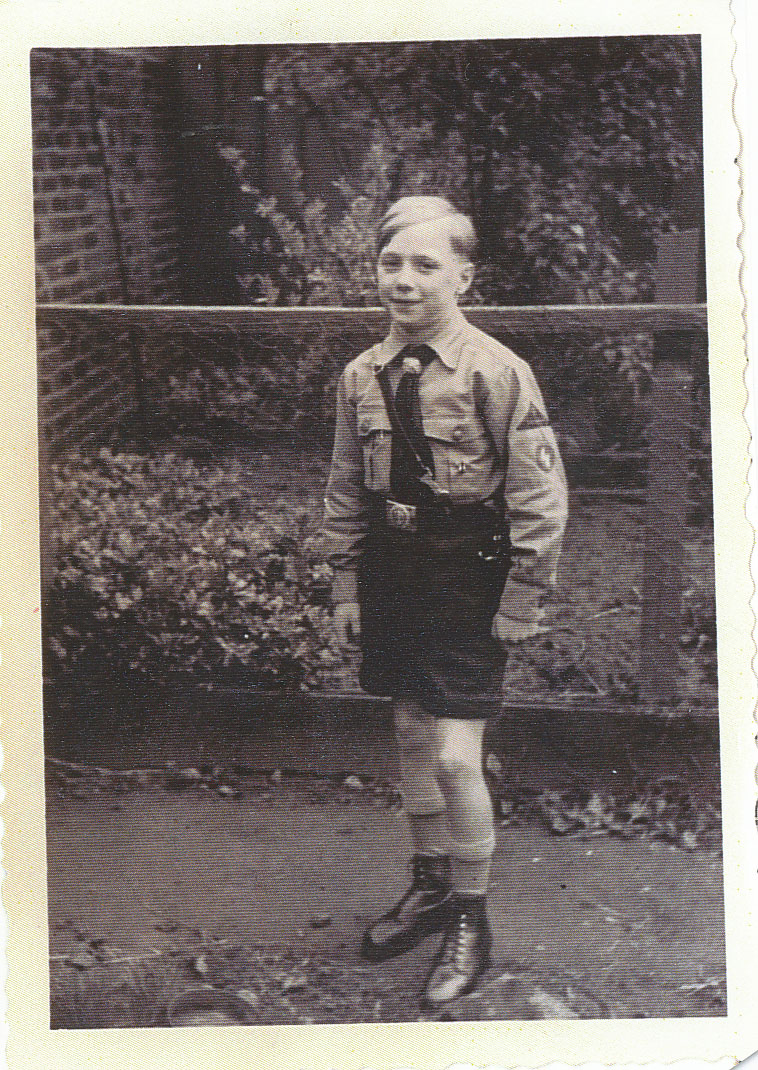

Fig. 5. Willy Ludwig as a Jungvolk boy in April 1939.

Fig. 5. Willy Ludwig as a Jungvolk boy in April 1939.

“Three weeks before finishing my apprenticeship as a carpenter, I was drafted into the Reichsarbeitsdienst,” recalled Karl Müller, “I worked on sewage systems and drained fields in Silesia.” Upon his return to Essen, he was drafted by the Wehrmacht and sent to Norway. Following a period of training as a radio man, he was assigned to a very remote outpost near the Arctic Circle. While there for three and one-half years, he dealt with isolation and did not know much about what was happening elsewhere in the war. Regarding his circumstances, he recalled: “I did not feel sad or depressed [in isolation]. I tried to make the best out of the situation. I did not have my scriptures with me while I was up there.” Like so many other German LDS soldiers, he was totally isolated from the Church and the Saints while away from home.

Artur Schwiermann was first a member of the Jungvolk and was then advanced to the Hitler Youth. Under the motto Jugend führt Jugend (youth lead youth), he was given charge of a group of younger boys. “We marched, sang and shot. We had air rifles and would go camping, which I always thought was fun.” On occasion, the meetings interfered with Sunday School, but Artur then was all the more determined to attend sacrament meeting that evening.

Many German civilians came into contact with prisoners of war or forced laborers from conquered countries, but fraternization was strictly prohibited. Nevertheless, Artur recalled watching his mother hand apples or potatoes to Russians they passed one day. “Somebody asked my mother if she wasn’t ashamed for giving food to the enemy and I joined in with ‘Yeah, Mom, you shouldn’t do that.’ She looked at me and replied, ‘Remember one thing: They are all children of our Heavenly Father.’ My mother was a Saint.”

Fig. 6. Gertrude, Angelika, and Walter Biehl in September 1942. (A. Biehl Bremer)

Fig. 6. Gertrude, Angelika, and Walter Biehl in September 1942. (A. Biehl Bremer)

During the last months of 1942 and the first months of 1943, Walter Biehl received training at what he called a “war school” near Prague, Czechoslovakia. He described it as an unpleasant experience but was pleased to be promoted to sergeant major. Following another furlough at home with his family, he was transferred to the Eastern Front in April 1943.

To escape the increasing danger in Essen, Johannes Biehl and his classmates were sent away in early 1943. He recalled the setting:

My class was sent to Austria to the Zillertal along with a teacher or two teachers in those days. They taught every subject that students needed to be taught in school, and an adult Hitler Youth Leader was also there. [We were put up in] a small hotel. We had to march in line to our meals, and instead of having a blessing on the food we would have to stand up and raise our arms and say, “Heil Hitler!” and the same at the beginning of the school class and at other gatherings. It was always “Heil Hitler!”

On March 3, 1943, former mission supervisor Friedrich Biehl was killed in an accidental fire in Russia. The letter written to his father by the company commander dated March 4 provides a description of the event:

In a temporary company barrack a fire suddenly broke out that rapidly spread to two adjacent barracks. A strong wind fanned the fire and in no time the entire structure was in flames. Although his other comrades were able to escape the conflagration, the company later determined that your dear son was not to be found and was probably consumed by the flames. Along with the entire company, I express my deepest sympathies.

Walter Biehl soon wrote to the company commander to inquire about the tragic event. His letter reads in part as follows: “Allow me to ask most respectfully: Was any trace of my brother found after the fire? From your letter, Herr Leutnant, it is not clear whether my brother actually perished in the flames.” The response was equally respectful, but negative: “I can report only that two days after I wrote my letter, the men searched the ruins of the barrack for any possible evidence that would allow the definite conclusion that your brother did indeed perish in the flames. Nothing could be found.”

It would seem that the lack of clarity about Friedrich Biehl’s fate was somehow recorded in Wehrmacht records. After the war, the German Commission for the Preservation of War Graves expressed the theory that his remains—as those of an unknown soldier—had been buried at a German war cemetery in Korpowo, Russia. [13]

Friedrich’s death was a terrible blow to Walter. He wrote this assessment of his brother in the following months:

Fritz was always a good example for me in everything. I will always have a respectful memory of him. I thank my Creator for the knowledge, that I will see my beloved brother and my other beloved ones after this life on earth. From the time of this death I have felt a deeper duty to the work of the Lord. Fritz left to me many good and noble thoughts, which I will use, so far as it is in my power. I wish the time were soon at hand that I could work again in the Church of Jesus Christ.

The following postscript was written by his father, Friedrich Johannes Biehl: “So far and to this point the writings of my son Walter. ‘Man thinks, but the Lord directs.’ So it was decided by the Lord to take our dear Walter to him on September 1, 1943.”

Following the death of two sons, Friedrich Biehl was predictably angry, blaming Hitler’s government for the family’s tragedies. His daughter, Margaretha, recalled how he came home from work for lunch one day and stated that he was going to “tell them.” Understanding that any complaints in public could lead to imprisonment and other penalties, Sister Biehl begged her husband not to make any protests to anybody. According to Margaretha, “I can still see my mother holding on to him and begging him to not say anything. [After that] maybe he just talked about it to people he trusted.”

In Austria, young Johannes Biehl found that letters he wrote to his brother Friedrich were returned. Soon after his father informed him of Friedrich’s death, another brother, Alfred, came for a visit along with his wife. Johannes was very discouraged, and Alfred reported that to their father. When Walter was killed, Brother Biehl felt that Johannes should not have to go through another such tragedy alone, so he traveled to Austria and told the authorities that he was taking his son home to Essen. Because most schools in Essen had been rendered useless, Johannes was sent to Wommen in Hesse to live with an uncle and to attend school.

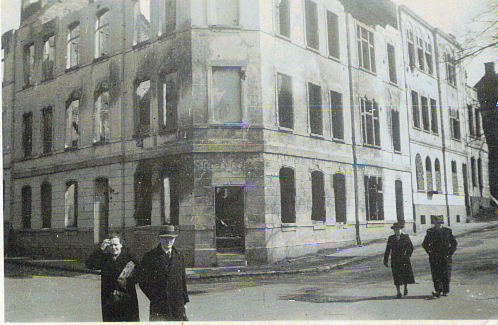

The branch meeting rooms at Krefelderstrasse 27 were destroyed early in the war, after which meetings were held first in the Krupp Realschule, and then in the apartments of various families, including the Biehls. That ended when the building in which the Biehls lived was gutted by bombs and flames. None of the family members were harmed; some were in the basement, others in public shelters, and Margaretha was visiting relatives in Wommen, Hesse. When she returned to Essen, she found her family living in her uncle’s apartment.

It seemed to Margaretha Biehl that the Allied air forces specifically planned to miss the huge Krupp factories when they dropped their bombs on Essen. According to her recollection, “They didn’t hit Krupp until the end of the war, but they hit most of the residential areas of the city.” In fact, official reports show that 90 percent of the city’s industrial area was destroyed and 60 percent of the entire city. Of the 664,523 residents in 1939, at least 30,746 were killed in the attacks and 1,356 prisoners of war were also victims. A total of 242 attacks were made on the city, of which 30 were considered “severe.” [14]

Fig. 8. The Biehl family lived on the second floor of this apartment building until it was bombed and burned out. (M. Biehl Haurand)

Fig. 8. The Biehl family lived on the second floor of this apartment building until it was bombed and burned out. (M. Biehl Haurand)

A remarkable incident occurred during an air raid that began during a church meeting on Sunday. Margaretha recalled that the Saints in attendance hurried to the shelter.

We were meeting at the Küppers on that Sunday. And then the sirens went off. And so we all went to an old high school (where we later held meetings) because they had a nice air-raid shelter underneath. There were other people in the shelter, and we [LDS] were in one corner—about twenty of us. And then we all knelt down to pray, and Brother Müller said the prayer. And he said, “And Heavenly Father, watch over these, our brethren in the airplanes that they would return home safely.” He called them our brothers. And we had to be careful that the others didn’t hear.

Artur Schwiermann was inducted into the national labor force in 1943 at the age of sixteen. He served on an antiaircraft crew in Steinfeld and Villach, Austria. “I was only there for a few months, but I saw a lot of action. The Americans flew over and it was my job to shoot them down. I was trained on the 88mm howitzer and learned how to use a radio.” While in the Reichsarbeitsdienst, Artur made the mistake of failing to salute a Gauleiter (regional leader of the Nazi Party). [15] In order to avoid a court-martial, he volunteered to join the Wehrmacht and was in the air force in early 1944.

The Ochsenhirt family also experienced tragedies during the war. The worst took place on October 25, 1944, according to daughter Berta (born 1909):

Our good mother and [our sister] Thekla got killed in an air raid. Myself, I was in Upper Hesse when that happened. . . . I traveled back [to Essen] partly by train, partly walking by foot, and sometimes riding in a farmer’s wagon. After two and a half days, I arrived in Essen because everything was destroyed. . . . People took me home but I don’t know who. There my father sat alone. He cried like a child. The next day was the funeral on the terrace cemetery. My father had a nervous breakdown.

For the next few months, Berta struggled to care for her distraught father. She eventually moved him into an asylum in Giessen, then to another in Mockstadt, and then back to Essen. During air raids in the last years of the war, she had to seek refuge with him in the same shelter in which his wife and his daughter had died. [16]

Berta’s brother, Willi Ochsenhirt, had been moved with his schoolmates and his teacher to a town in Czechoslovakia in 1942. It was there that he heard about the air raid that had killed so many people in Essen. In 1944, he was surprised to see his mother come to visit him. He was still in that town when she was killed in October. Soon after the air raid, Willi and his friends were told that the attack on Essen had taken the lives of many people, but Willi did not know if any of his family members were among the victims. Nevertheless, when permission was given for some of the boys to go to Bratislava and from there to Germany, he was one of those who left. On the way to Bratislava (approximately twenty miles), he met a man he would call his good Samaritan.

I was walking along in my Hitler Youth uniform trying to get passing German trucks to give me a ride, but nobody would. Then a Slovakian truck came by and a man asked if I needed help. I told him what I needed [a ride to Bratislava], and he took me right to the railroad station there. My own people would not help, but he did, even though the Slovaks hated us and the [Hitler Youth] uniform I was wearing.

Willi traveled to Vienna, where he found his sister. The two then made their way home to Essen and arrived in November to find that their mother and their sister had indeed been killed. According to Willi, his mother was fortunate to be buried in a coffin at a time when most of the dead were simply wrapped up and placed in mass graves. A few months later, boys of Willi’s age were required to report for an army physical. Being very small (still not even five feet tall), he was told by the army physician, “You’re too little. Go back home to your mama.” Some of Willi’s friends were drafted, and some were killed in the final months of the war.

Fig. 9. Air-raid damage done to the apartment house in which theSchwiermannslived. (A. H.Schwiermann)

Fig. 9. Air-raid damage done to the apartment house in which theSchwiermannslived. (A. H.Schwiermann)

Shortly before the war ended, Karl Müller’s unit was moved from Norway to southern Germany to escape the advancing Soviet army. In Germany, Karl was taken prisoner by the Americans and later handed over to the French. As POWs in France, Germans learned the dangers of working with two kinds of mines—the coal mines whose terrible conditions cost many young men their health, and the land mines that had to be removed from fields and forests where German attackers and defenders had laid them. Because he was not robust, Karl was put on the land mine removal detail. He described the work in these words:

We received training on how to remove the mines safely. I did think about the fact that I could die when I was a prisoner removing those mines. But for some reason, I always had the feeling that nothing would happen to me although I saw people dying because of this every day. My clothing was often ripped apart but my skin was never hurt. One never knew if there was a mine with every step that was taken.

A combat veteran by the end of the war, Artur had seen many of his friends killed, mostly in Poland and eastern Germany as the Soviet Army moved inexorably into Germany. Along the way he had several opportunities to take the life of an enemy, but he never did so. He described one such situation in these words:

One time, we had orders to take prisoners. Three Russians came out, and I knew that if I turned them in, that they would be shot. I shot at them but missed them on purpose by quite a ways. They got the message and took off. It is possible to have a good heart even though one is a soldier. My dad always told me that if somebody surrendered, you give them all the courtesy you can.

Artur’s unit eventually moved through Czechoslovakia and surrendered to the Americans coming from the west toward Dresden. Unfortunately for Artur, the Americans turned him over to the Soviets (a German soldier’s worst nightmare), and he began a term of four and a half years as a POW. “They didn’t give us enough to eat, and I went from 185 pounds to 95 pounds in the first six months. I kept going for the next four years. I stole a lot and tried to survive that way—whatever I could get my hands on.”

Johannes Biehl experienced the end of the war at his uncle’s home in Wommen. Just a few miles from Eisenach, Johannes had been able to visit the Wartburg Castle, where Martin Luther had translated the New Testament into German. In that location, Johannes came into contact with both American and Soviet invaders in April 1945, because the border of the two occupation zones ran between Wommen and Eisenach. He recalled that when the Americans came through Wommen, a black soldier saw his watch: “He said, ‘Beautiful!’ and then he ripped the watch off my wrist.” Fortunately, that incident was the worst thing that happened to Johannes Biehl in Wommen. A few months later, he was home in Essen.

The following text from the branch history reflects the difficulties experienced by Latter-day Saints still in the city of Essen after their meeting rooms at Krefelderstrasse 27 were destroyed:

The members were once again left up to their own devices and had to improvise. The Paul Küpper, Schwiermann and Naujock families allowed the Saints to meet in their homes. The Küpper family provided space in their basement. The Naujocks family had a single family dwelling on Lepsiusweg in the suburb of Frohnhausen and the Schwiermann family had a large apartment. The meetings were thus held alternately at those locations. . . . Eyewitnesses . . . testify that they could truly feel the spirit of the Lord under those humble circumstances, despite all of the problems they had to contend with on a daily basis. [17]

By the time the war ended, Willi Ochsenhirt had left Essen and joined two of his sisters in a small ancestral town north of Frankfurt. It was there that he experienced the arrival of the American army. As he recalled, “I had a knife with a handle made of deer bone. I went up to a soldier and gave it to him (I had learned to speak English in school). They were checking everybody to see if we had weapons, so I just gave it to him.” Like most boys his age (sixteen at the time), Willi was always ready for a new adventure. So it was that he and some friends found an American tank abandoned in the mud, and they climbed inside. There they found cigarettes and food “and stuff.” Later, they discovered a German Panzerfaust (bazooka); having been shown previously how to operate the weapon, they successfully fired it at a tree.

In 1947 and 1948, Karl Müller received a more merciful assignment as a POW in France. No longer did he have to remove land mines, but rather he worked with electronics and repaired watches. Regarding his time away from home, he said the following:

During the seven years I was away from home, I never met another member of the Church or had any contact with the Church. My parents received a letter stating that I was missing in action, and they did not know where I was or if I was still alive for some time. And then my grandmother (who was not a member of the Church but a very good woman) had a dream that I had visited her to tell her that I was in French captivity and that I was doing well. I also gave her the name of the place where I was. She then went and looked for that place and found it on a map. She told my parents where I was and that I was safe.

Returning to Essen in 1948, Karl learned that his parents had been bombed out of their home but had survived and were well, living in a suburb of Essen. He concluded his story with this statement: “My testimony was not shaken because of the war. I did not worry about the idea that God would let things like this happen. I knew that his ways were not our ways.”

During his years as a POW in the Soviet Union, Artur Schwiermann endured harrowing conditions but eventually regained much of his weight. Part of the suffering was emotional, caused by the overseers’ practice of promising that a prisoner would be sent home soon, only to postpone the move time and time again. Regarding his spiritual condition during those times, he offered the following summary:

I was in the service for seven years and never had the opportunity to attend a meeting, meet a member of the Church, or read the scriptures. I had a testimony of the Church before I went away in the army. I held my own Sunday Schools on Sundays alone and because I remembered some of the songs, I just listened to them in my mind. I promised the Lord that if he would get me out of this hell, I would never miss a church meeting again. While I was gone in the service, I could have answered correctly all of the questions asked in a temple recommend interview.

Several members of the Essen Branch were killed in the air raids that reduced the city to rubble. Several others were among the 18,864 men of the city who died in the service of their country. The few Saints who were still in Essen when the American army arrived on April 11, 1945, were still holding meetings and looking forward to the time when their loved ones would return.

In Memoriam

The following members of the Essen Branch did not survive World War II:

Elisabeth Helene Bernicke b. Essen, Rheinprovinz, 31 Mar 1904; dau. of Heinrich Bernicke and Auguste Kutz; bp. 6 Oct 1921; conf. 6 Oct 1921; d. rib infection 20 May 1945 (FHL microfilm 68789, no. 1; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 16; FHL microfilm 25722; 1930 census; IGI)

Friedrich Ludwig Biehl b. Essen, Rheinprovinz, 26 Feb 1913; son of Friedrich Johannes Biehl and Marie Nölker; bp. 14 Dec 1924; conf. 14 Dec 1924; ord. deacon 14 Apr 1929; ord. teacher 25 Jan 1931; ord. priest 13 Dec 1932; ord. elder 4 May 1934; German-Swiss Mission 7 Mar 1934 to 1 Nov 1936; supervisor West German Mission 1 Sep to 31 Dec 1939; private; company clerk; d. in fire Buregi, Ilmensee 3 Mar 1943 (M. Biehl Haurand; FHL microfilm 68789, no. 4; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 20; www.volksbund.de)

Walter Konrad Biehl b. Essen, Rheinprovinz, 11 Jul 1914; son of Friedrich Johannes Biehl and Marie Nölker; bp. 14 Dec 1924; conf. 14 Dec 1924; ord. deacon 14 Apr 1929; ord. teacher 17 Apr 1932; ord. priest 3 Oct 1937; ord. elder 13 Jan 1938; West German Mission 12 Jan 1938 to 6 Jan 1939; m. 27 May 1939, Gertrud Lotte Mamat; 1 child; lieutenant; k. in battle Russia 1 Sep 1943 (FHL microfilm 68789, no. 5; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 24; M. Biehl Haurand; H. Haurand; IGI)

Bendix Christian Karl Breitenstein b. Herbede, Westfalen, 5 Mar 1907; son of Heinrich Gottfried Breitenstein and Elisabeth H. Mintrup; bp. 16 Apr 1921; conf. 16 Apr 1921; m. Feb 1929, Anna Zaremba; police constable; k. in battle Trojana Pass, Balkans, 23 Aug 1944 (FHL microfilm 68789, no. 19; CHL microfilm 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, pp. 202–3; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 43; FHL microfilm 25728, 1925 and 1930 censuses; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Ernst Johann Heinrich Gallep b. Kettwig, Werden, Rheinprovinz, 24 Jul 1914; son of Heinrich Gallep and Martha Eumann; bp. 9 Jun 1928; conf. 10 Jun 1928; ord. deacon 1 Sep 1929; ord. teacher 13 Dec 1932; ord. priest 27 Feb 1933; ord. elder 4 Jul 1934; missionary 28 Dec 1932; m. 17 Dec 1938, Liesbeth Böttcher or Boettger; k. in battle Mal Skabino, Russia, 25 Jan 1944 (FHL microfilm 68789, no. 27; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 431; IGI)

Elisabeth Marie Luise Heckmann b. Kirchheimbolanden, Rheinprovinz 14 Sep 1861; dau. of Peter Heckmann and Karoline Hofmann; bp. 20 Mar 1923; conf. 20 Mar 1923; m. 15 Jun 1885, Wilhelm Karl Fahrbach; d. old age 4 Feb 1943 (FHL microfilm 68789, no. 190; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 813; IGI)

Leo Karbacher b. Klein Tarpen, Graudenz, Westpreußen or Essen, Rheinprovinz 29 Dec 1899; son of Leo Karpinski and Pauline Stankewitz; bp. 22 Aug 1925; conf. 22 Aug 1925; m. 16 Aug 1924, Therese Anna Horn; k. bomb explosion 25 Oct 1944; bur. Terassenfriedhof, Essen, Rheinprovinz (FHL microfilm 68789, no. 51; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 160; FHL microfilm 271376; 1925, 1930, and 1935 censuses; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Ernst Lehnert b. Niklasberg, Böhmen, Austria, 16 Oct 1879; son of Johann Lehnert and Anna Krause; bp. 28 Oct 1928; conf. 28 Oct 1928; ord. deacon 1 Sep 1929; ord. teacher 1 Feb 1931; ord. priest 17 Apr 1932; ord. elder 6 Mar 1937; m. 5 Jun 1910, Auguste Emilie Minna Luthin; d. lung disease 29 Apr 1945 (FHL microfilm 68789, no. 65; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 446; FHL microfilm 271386, 1930 and 1935 censuses)

Hermann Benjamin Mantwill b. Mulk, Ostpreußen, 6 Jan 1876; son of Karl Ludwig Mantwill and Auguste Dorothea Schmidt; bp. 3 Apr 1920; conf. 3 Apr 1920; ord. deacon 24 Jul 1921; ord. teacher 14 Jun 1925; ord. priest 14 Apr 1929; ord. elder 12 Jul 1936; m. 26 Apr 1905, Johanna Louise Gärtner; 3 children; d. gastric ulcer Essen, Rheinprovinz, 9 Aug 1941 (FHL microfilm 68789, no. 73; IGI)

Karl Gustav Müller Jr. b. Ellrich, Grafschaft Hohenstein, Sachsen (province), 22 Sep 1888; son of Johann Philipp Karl Müller and Hennriette Karoline Dorothea Schoenemann; bp. 22 Aug 1925; conf. 22 Aug 1925; ord. deacon 14 Sep 1926; ord. teacher 14 Apr 1929; ord. priest 1 Feb 1931; ord. elder 6 Mar 1937; m. Ellrich 8 Apr 1912, Friederike Emilie Fuchs or Krone; 2m. 11 Oct 1921, Katharina Elise Somm; 1 child; d. pneumonia Essen, Rheinprovinz, 31 Jan 1945 (FHL microfilm 68789, no. 82; IGI)

Heinz Erwin Emil Naujoks b. Hamborn, Rheinprovinz, 9 May 1915; son of Emil Naujoks and Berta Marta Eschrich; noncommissioned officer; d. Chemin-des-Dames, France 8 Jun 1940; bur. Ford-de-Malmaison, France (IGI; www.volksbund.de)

Emilie Ochsenhirt dau. of Thekla Ochsenhirt (M. Biehl Haurand)

Friedrich Ochsenhirt b. Darmstadt, Hessen, 4 Jul 1912; son of Friedrich Ochsenhirt and Emilie Schwarzhaupt; bp. 11 Sep 1920; conf. 11 Sep 1920; m. Hessen 10 Nov 1935, Elise Gottschalk; d. MIA Stalingrad, Russia, 1942; bur. Rossoschka, Wolgograd, Russia (W. Ochsenhirt; www.volksbund.de)

Thekla Ochsenhirt b. Ranstadt, Hessen, 15 Dec 1906; dau. of Friedrich Ochsenhirt and Emilie Schwarzhaupt; bp. 23 Aug 1919; conf. 23 Aug 1919; k. air raid 25 Oct 1944 (FHL microfilm 68789, no. 100; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 2530)

Erwin Pfotenhauer b. Essen, Rheinprovinz, Preussen, 25 Sep 1921; son of Waldemar Wilhelm Pfotenhauer and Christine Kohl; bp. 28 Feb 1931; conf. 1 Mar 1931; ord. deacon 3 Jan 1937; lance corporal; k. air raid Liebau, Latvia, 22 Nov 1944 (FHL microfilm 68789, no. 152; Jansen, KGF; CHL microfilm 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, 186–87; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 575; FHL microfilm 271393; 1925, 1930, and 1935 censuses; IGI; www.volksbund.de)

Werner Hermann Pfotenhauer b. Essen, Rheinprovinz, 24 Nov 1917; son of Waldemar Wilhelm Pfotenhauer and Christine Kohl; bp. 22 May 1926; conf. 22 May 1926; ord. deacon 7 Aug 1932; m. 20 Apr 1940, Anneliese Brosch; lance corporal; d. in POW camp 99 Spasskij Sawod, Ural, Russia, Jun or Jul or Sep 1941 (FHL microfilm 68789, no. 113; Jansen; www.volksbund.de; CHL microfilm 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, 1949 list, 764–65; FHL microfilm 271393, 1925, 1930, and 1935 censuses; IGI)

Hermann Rehkopf; b. Niedernjesa, Göttingen, 7 Jun 1898; corporal; k. Dunquerque, France, 25 Feb 1945; bur. Bourdon, France (www.volksbund.de)

Paul Erich Schäl b. Essen, Rheinprovinz, 20 Nov 1916 or 22 Nov 1916; son of Friedrich Schäl and Klara Ida Ludwig; bp. 10 Jul 1925; conf. 10 Jul 1925; lance corporal; k. in battle Kutowaya, Russia, 30 Jun 1941; bur. Petschenga-Parkkina, Russia (FHL microfilm 68789, no. 136; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 342; FHL microfilm 245258; 1925, 1930, and 1935 censuses; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Friedrich Schäl b. Gottesberg, Schlesien, 9 Feb 1889; son of —— Schäl and Ernestine Heinzel; bp. 18 Sep 1926; conf. 18 Sep 1926; ord. deacon 31 Oct 1933; ord. teacher 10 Jan 1937; ord. priest 9 Oct 1938; m. 26 Dec 1912, Klara Ida Ludwig; at least 3 children; k. air raid 27 Apr 1944; bur. Essen, Rheinprovinz (FHL microfilm 68803, no. 338; FHL microfilm 245258; 1930 and 1935 censuses; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Emilie Schwarzhaupt b. Ranstadt, Oberhessen, Hessen, 20 Oct 1885; dau. of Konrad Schwarzhaupt and Minna Westerweller; bp. 7 May 1910; conf. 7 May 1910; m. Ranstadt 17 Aug 1902, Friedrich Ochsenhirt; k. air raid 25 Oct 1944 (FHL microfilm 68789, no. 99; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 252; IGI)

Auguste Wilhelmine Stadie b. Groβ Jegersdorf, Insterburg, Ostpreuß, 3 May 1873; dau. of Christoph Stadie and Dorothea Braemer; bp. 14 Dec 1924; conf. 14 Dec 1924; m. Norkitten, Ostpreußen, 16 Jan 1895, Ferdinand Wilhelm Schmude; d. old age Roxheim, Hessen, 22 Apr 1943 (FHL microfilm 68789, no. 137; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 356; FHL microfilm 245258, 1925, 1930, and 1935 censuses; IGI; AF)

Augusta Szillat b. Ossingken, Ostpreußen, 14 Feb 1870; dau. of Daniel or David Szillat and Marie Szebang or Szebauy; bp. 12 Feb 1932; conf. 12 Feb 1932; div.; d. heart attack 27 Jan 1945 (FHL microfilm 68789, no. 189; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 812; FHL microfilm 245279, 1935 census; IGI)

Notes

[1] Essen city archive.

[2] West German Mission branch directory, 1939, CHL LR 10045 11.

[3] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” 257, CHL CR 4 12.

[4] Karl Gustav Müller, interview by the author in German, Breitenbach, Germany, August 18, 2008; unless otherwise noted, summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[5] Artur Heinz Schwiermann, telephone interview with the author in German, November 30, 2009.

[6] Essen branch history, 29. For some reason, the branch history gives the house number as 29, whereas the branch directory and eyewitnesses agree that the number was 27.

[7] Erma Rosenhan, papers, CHL MS 16190.

[8] Willi Ochsenhirt, interview by the author, Riverton, UT, April 6, 2007.

[9] Friedrich Ludwig Biehl, “Life Story” (unpublished autobiography), chapter 7; private collection.

[10] Margaretha Biehl Haurand, interview by the author, Bountiful, Utah, April 6, 2007.

[11] John A. Biehl, telephone interview with the author, August 6, 2009.

[12] Berta Ochsenhirt Hommes, “The Ochsenhirt Family History” (unpublished manuscript); private collection.

[13] See the commission’s website at www.volksbund.de. The commission is understandably very reluctant to provide any but exact details regarding the whereabouts of missing German soldiers.

[14] Essen city archive.

[15] He defended himself with the derogatory statement, “I don’t see a reason to salute every streetcar conductor” (a dangerous reference to Nazi Party officials as being nonmilitary and thus superfluous).

[16] Friedrich Ochsenhirt never recovered from the shock of his wife’s death. Eventually, Berta took him to Upper Hesse, near his birthplace, where he died in 1950.

[17] Essen Branch history, 31.