Düsseldorf Branch

Roger P.Minert, “Dusseldorf Branch,” in Under the Gun: West German and Austrian Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 348–353.

Düsseldorf is one of the principal industrial cities along the Rhine River in northern Germany. With 535,753 inhabitants in 1939, it was also one of the largest cities in the Ruhr River area. [1] The branch of the LDS Church in that city was relatively small, having only sixty members and fourteen priesthood holders as World War II approached.

Missionary Clark Hillam of Brigham City, Utah, was serving as branch president at the time, and the branch directory shows that he had no counselors. [2] Paul Schmidt was the Sunday School superintendant, Mannfred Knabe the leader of the YMMIA, Margarete Keller the leader of the YWMIA, and Hedwig Klesper the president of the Relief Society, but no organized Primary existed at the time. Paul Doktor Sr. was the genealogical instructor.

| Duesseldorf Branch [3] | 1939 |

| Elders | 4 |

| Priests | 4 |

| Teachers | 3 |

| Deacons | 3 |

| Other Adult Males | 13 |

| Adult Females | 28 |

| Male Children | 5 |

| Female Children | 0 |

| Total | 60 |

The meeting schedule for the Düsseldorf Branch shows Sunday School starting at 10:00 a.m. and sacrament meeting at 7:00 p.m. The only other meetings held in July 1939 were on Wednesdays: Mutual at 8:00 p.m. and Relief Society at 9:00 p.m.

Branch meetings were held in rented rooms at Worringerstrasse 112. Kurt Fiedler (born 1926) described the rooms as being on the second floor of the building at that address. “It was a business building. We set up chairs [each week] in the main meeting room, and there was another smaller room as well. There might have been thirty people in church on a typical Sunday.” [4]

“It was a very small group, but a good branch,” recalled Clark Hillam regarding the Saints in Düsseldorf. He was sad when the telegram came on August 25, 1939, instructing him to leave the country immediately. The telegram also told him to appoint a successor as branch president. He described the situation:

After we got our evacuation notice, I still had enough time to go to Brother [Paul] Schmidt to tell him that he would be the new branch president. I handed all the records over to him, and he knew that he would be on his own. They were all very sad when they heard that all the missionaries had to be evacuated. They knew that if the missionaries had to leave, that problems were not far away. They believed in the fact that they would be safer if missionaries were around them. [5]

Kurt Fiedler was one of six children in a family who lived in the eastern suburb of Grafenberg, about three miles from downtown Düsseldorf. His mother, Elli, was the secretary of the Relief Society, and his father (though not a member of the Church) “was always active in the branch as either the drama director or the entertainment director. He really loved that,” Kurt recalled.

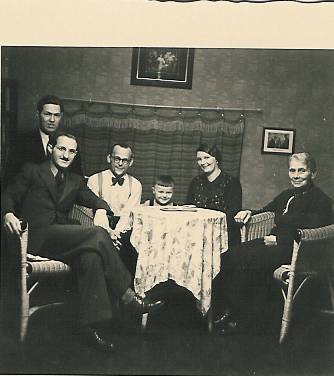

Fig. 1. Elders Welti (standing left) and Hillam in the home of the Schmidt family. (C. Hillam)

Fig. 1. Elders Welti (standing left) and Hillam in the home of the Schmidt family. (C. Hillam)

Just prior to the war, Kurt was a member of the local Hitler Youth group. He remembered the following: “We were trained in survival and camping. I never saw a gun in the Hitler Youth. We did a lot of marching because they mainly taught us discipline. We didn’t have political lessons, but we wore our uniforms for meetings, and that was in itself a political lesson.”

Manfred Knabe (born 1930) provided a fine description of the conditions in wartime Düsseldorf:

We lived under a blackout. All windows had to be totally darkened with black material so that no light could be seen outside. Wardens monitored that very closely and fines were given to people who did not comply. There was an air raid warden in each apartment house. My mother had that duty in our building. She had to see to it that there were buckets of sand and water on each landing in the staircases. And there had to be a broom with a bag over the end to be used to beat out the flames. Every basement was outfitted to serve as an air raid shelter. Thick logs were used to fortify the ceiling joists and bunk beds were installed. A hole was made in each wall to an adjacent building, about one meter in diameter, then the bricks were replaced loosely. If we needed to escape our basement, we could kick the bricks out of the opening and escape. [6]

Preparations for survival during air raids were serious activities, but collecting shrapnel and bomb fragments on the mornings after the raids was a favorite pastime for city children. Manfred recalled that the brass cases from antiaircraft rounds were especially valuable pieces of his collection.

As the war progressed and Düsseldorf became a frequent target of Allied bombers, Kurt Fiedler was called to perform a most unpleasant duty:

I was assigned to what you would call the home defense. After air raids, we had to dig up the dead or rescue the living who were trapped under rubble—the clean-up after the air raids. It was not very pleasant because, especially when they bombed apartment homes, we had to go down [into the basements]. We were only fifteen and sixteen years old then. We had to remove the bodies of those who were killed. When we found a group of survivors, we felt very successful; that was a good feeling. [But the memory of finding bodies] stays with you for a while.

According to the city historian, Düsseldorf suffered nine heavy air raids and 234 raids resulting in medium damage. [7] During one of those many raids, the branch meeting rooms were bombed out. According to Kurt, meetings thereafter were held first in schools; when that was no longer possible, the Latter-day Saints met in the apartments of member families. Some of the branch members living in the southern neighborhoods of the city also attended meetings with the branch in Benrath, just a few miles south of Düsseldorf.

In January 1943, Manfred Knabe and his classmates were sent off to eastern Germany as part of the Kinderlandverschickung program. They were housed in a very nice dormitory in the small town of Döntschen and supervised by their teacher and by a Hitler Youth leader. Manfred described the daily life of the thirty-six boys in these words:

We had our classes in the mornings. After lunch, we had quiet time, that is, we had to lie on our beds. Then we did our homework, of course under the watchful eye of our teacher. Then we had our afternoon coffee and our Hitler Youth drills. Then came sports, marching, and war games. We usually had a great time in those activities because our Hitler Youth leader did his job very well. Then several boys were sent off to do small tasks such as fetching milk and mail, peeling potatoes, etc. That kept us in good shape socially. All in all, it was a good experience—except for the homesickness!

Manfred was allowed to go home in November 1943, but he arrived precisely at the conclusion of a terrible air raid. Passing burning buildings on their way home, his mother suggested that he might be better off back at Döntschen. In a subsequent attack, their home burned to the ground, and the family saved only what they could carry. By January 1944, Manfred was back with his schoolmates in eastern Germany, but in a different town. They had been moved to Seiffen, a town famous for its toy manufacturing. Manfred was hosted by the family of a wood carver, and he enjoyed helping the artisan in his shop. Winter sports such as skiing were also a great activity for a big city boy from Germany’s flatlands.

Not far from Seiffen was the town of Rechenberg-Bienenmühle, where a small LDS branch held Sunday School. Manfred learned of their meetings and received permission from his teacher to walk there on several Sundays. As he recalled, “My mother had told me where they met, and I was so happy. I walked to Brother Fischer’s house with my hymnal; he was the Sunday School president. They even had a pump organ, but nobody could play it, so I did it as well as I could—usually with two fingers.”

The family of branch president Paul Schmidt lived at Lorettostrasse 51 in Düsseldorf. According to his son, Siegfried (born 1939), they walked perhaps twenty minutes to church. Unfortunately, Brother Schmidt’s term as the branch leader ended in 1943 when his apartment was destroyed. Although only four at the time, Siegfried recalled clearly the night his home was hit by Allied bombs. With the building above them in flames and the exit from the basement blocked, he and his mother had to leave through a hole in the basement wall into the next building. Emerging onto the street, they saw that their building would not survive the flames. He described what happened next:

All I could see was fire everywhere. Seeing us walking down the street, a woman stopped and asked us if we had lost our home. When we told her that we had, she invited us to come to her house so we would have a safe place to stay. Soon, my father came home [from Leipzig] and stood in front of a house that seemed to be unfamiliar—he could still see our kitchen. My mother had taken a board and written where he could find us in case he came home and hung the board on the front door. My father later told us that he said a prayer the moment he realized that we were alive, giving thanks to his Heavenly Father. [8]

Paul Schmidt was a construction engineer for the Rheinmetall Co., a manufacturer that had been compelled to move its operations into the interior of Germany a few months earlier. When he found an apartment near Leipzig, Brother Schmidt moved his family out of Düsseldorf, hoping to take them a bit farther away from the dangers of the war.

The Schmidt family’s new apartment was in Zehmen, a few miles from Leipzig. Siegfried recalled walking more than an hour to the outskirts of town on Sunday mornings, then taking a streetcar to church. Because it was too far for them to go home between meetings, they stayed at the home of Siegfried’s aunt in Leipzig in the afternoons, then returned to the rooms of the Leipzig West Branch for sacrament meeting.

In 1943, Kurt Fiedler was drafted into the national labor force and sent off to help build air fields. He did that for three months. Back at home in November 1943, he knew that a call to the Wehrmacht would arrive soon, so he volunteered in order to choose his branch of the service. He selected the navy and was sent to the Netherlands, where he was assigned to a submarine unit. Fortunately, he was not sent to sea but rather was trained as a torpedo specialist and sent to an arsenal at a French port city. The closest he came to actual service at sea was an overnight voyage in a submarine that was short of crew members.

Fig. 2. Celebrating the “spirit of the pioneers” in 1939. (C.Hillam)

Fig. 2. Celebrating the “spirit of the pioneers” in 1939. (C.Hillam)

By the summer of 1944, the Allied forces that landed at Normandy were moving toward the interior of France, and Kurt Fiedler’s unit was sent eastward. “We had lost too many submarines by then, and they didn’t need us for that duty anymore,” he explained. “They sent us in small groups because the French underground were looking for us. One of our small groups was totally wiped out. Eventually, a train picked us up and took us eastward—past Berlin and all the way to Kolberg [near the Baltic Sea].”

Arriving in Kolberg three days behind schedule, the young soldiers were first threatened with court martial due to their tardiness; they managed to convince their officers that constant bombings had delayed their transportation. Kurt and his comrades then received an assignment to work on the assembly of the V-2 rocket bomb. They remained at that factory until early 1945. Bombed out of work at the factory, they were sent to Cuxhaven on the North Sea coast, where they were assigned to a ship that never came. They simply waited there until the British invaders surrounded the harbor.

When it appeared to the people of Seiffen that the war was lost and the Soviets would be in their town soon, they entered the forest and buried any items bearing swastikas, such as uniforms and books. On May 8, a Soviet officer came to town and ordered the people to remove antitank barriers. After doing that, the boys and their leaders began a long hike toward home, having no desire to wait until the Red Army arrived. After walking more than one hundred and fifty miles westward through the Erzgebirge Hills in about nineteen days, they arrived in the city of Eisenach. Their leaders were able to find four trucks to take them westward toward home. A few days later, Manfred arrived at the home of his parents in a devastated Düsseldorf. His family had lost their home and most of their possessions, but fourteen-year-old Manfred (from whom nothing had been heard for several months) had come home safe and sound.

Siegfried Schmidt recalled experiencing the end of the war as a six-year-old:

A large group of [German] antiaircraft crew members went marching by under American guards. Each prisoner had his hands behind his head. That was the first thing I could recall about peacetime. When the Americans came into our town, they gave me a bar of chocolate and a pat on the back. I knew that they were looking for German soldiers in our houses, but there was nothing wrong with that.

Things worked out for POW Kurt Fiedler everywhere he turned. His British captors did not work their prisoners very hard, and before long Kurt found himself working in the kitchen. “I had all the food I could eat.” In August 1945, the camp commandant asked Kurt if he wanted a leave to go home for ten days. “He said that if I could either enroll in school or find a job; he would give me my final release when I returned to the camp.” He was even allowed to use British transportation on his way home to Düsseldorf. After a successful ten days, he returned to the camp only long enough to get the release papers. The British even loaded his duffel bag with food and other valuables that he could take home to his family.

During his two years away from home as a soldier and a POW, Kurt Fiedler never saw combat action. He also never saw the inside of an LDS church, met another LDS soldier, or took the sacrament. His only contact with any church came when the POWs were required to attend a service in the local Lutheran church. As he explained, “We had to go to church on Sunday. If we didn’t or couldn’t, they would make us do KP duty or clean toilets. Of course, nobody wanted to do that.”

The Fiedler home in Grafenberg was fortunate to survive the war without a scratch, although Kurt recalled coming home to the sight of buildings down the street that were damaged to some degree. Most of the Latter-day Saints in Düsseldorf were still alive in 1945, but four of Kurt’s non-LDS friends had lost their lives in the service of their country. “It was a bit lonely when I came home,” he explained, “but soon I fell in love with a young lady from the Benrath Branch who eventually became my wife.”

The loss of Kurt’s brother Herbert Eduard, known as Eddy, was especially difficult to understand. At the end of the war, Herbert was only fourteen but was not normal as defined by Nazi health standards. Kurt described his younger brother in these words: “He was an autistic child who had trouble learning. He was a good kid, a great kid. He was smart.” During the war, a doctor required the boy to be sent to an institution. On one occasion, Kurt visited Eddy at a town somewhere in the Rhineland. Toward the end of the war, the family received notice that Eddy had died of pneumonia. They were certain that he had become a victim of the heinous euthanasia program. Kurt recalled the following:

They did experiments with kids [like Eddy]. We learned later on from a nurse who worked there. She contacted my mother, and she said they worked with those kids, and they experimented with them and killed them. That was in a place called Rupert. I visited him there once; he was in bad shape. I could see that already. It was not Eddy anymore, he was a different person. That was shortly before they announced that he died of pneumonia.

The metropolis of Düsseldorf appeared to be a hopeless landscape in the summer of 1945. More than nine thousand people had perished during the destruction of the city, and it would be years before there would be enough housing for the survivors. [9] Like their neighbors, the Latter-day Saints of the Düsseldorf Branch would return over the next few years from countless locations in Germany, Europe, and elsewhere to begin a new life.

In Memoriam

The following members of the Düsseldorf Branch did not survive World War II:

Herbert Eduard Fiedler b. Düsseldorf Stadt, Rheinland, 18 Jun 1930; son of Alexander Ferdinand Valentin Fiedler and Minna Ella Hecker; d. euthanasia, hospital in Rheinland 1944 or 30 May 1945 (Karl Fiedler; IGI)

Eduard Oskar Huettenrauch b. Kunitz, Jena, Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach, 16 Oct 1866; son of Eduard Huettenrauch and Auguste Heuslar or Heussler; bp. 3 Sep 1931; conf. 3 Sep 1931; ord. deacon 19 Jun 1932; d. heart disease 11 Jan 1941 (CHL CR 375 8 2430, no. 949; FHL microfilm 162792, 1935 census; IGI)

Heinrich Laux b. Straβburg, Elsaß-Lothringen, 21 May 1886; son of Georg Laux and Alwine Weimar; bp. 1 Jul 1932; conf. 1 Jul 1932; d. 4 Jul 1943 (FHL microfilm 68788, no. 53; CHL CR 375 8 2430, no. 973; IGI)

Hubertine Reiner b. Baal, Rheinprovinz, 10 Feb 1871; dau. of Otto Reiner and Anna Maria Porten or Perten; bp. 12 Sep 1924; conf. 12 Sep 1924; m. Oct 1898, Wilhelm Heinrich Hermann Schnell; d. heart attack 1 May 1943 (FHL microfilm 68788, no. 43; FHL microfilm 68786, no. 162; FHL microfilm 245258, 1925, 1930, and 1935 censuses)

Lena Eliese Grete Wachsmuth b. Haspe, Westfalen, 2 Mar 1901; dau. of Friedrich Georg Hubert Wachsmuth and Selma Alma Clauder; bp. 8 Feb 1925; conf. 8 Feb 1925; d. 7 Dec 1938 (FHL microfilm 68788, no. 44; IGI)

Franz Josef Wolters b. Dorsten, Westfalen, 10 Nov 1857; son of Josef Johannes Clemens Wolters and Anna Maria Bernhardine Schulte; bp. 16 Oct 1920; conf. 16 Oct 1920; ord. priest 15 Dec 1935; ord. elder 15 Dec 1935 or 21 May 1939; m. Essen, Rheinprovinz, 21 May 1889, Friederike Francisca Brücker; 7 children; d. old age 23 Jan 1944 (FHL microfilm 68788, no. 73; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 690; FHL microfilm 68803, no. 690; FHL microfilm 245303, 1935 census; IGI)

Wilhelmine Marie Clara Rosa Zacher b. Erfurt, Sachsen, 29 Jul 1884; dau. of Wilhelm Zacher and Anna Louise Wilhelmine Amanda Müller; bp. 6 Dec 1901; conf. 6 Dec 1901; m. 26 Apr 1914, August Weber; d. blood poisoning 25 Jul 1944 (FHL microfilm 68788, no. 45; FHL microfilm 68786, no. 114; IGI)

Notes

[1] Düsseldorf city archive.

[2] West German Mission branch directory, 1939, CHL LR 10045 11.

[3] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” 257, CHL CR 4 12.

[4] Kurt Fiedler, interview by the author, Sandy, UT, February 17, 2006.

[5] Clark Hillam, interview by the author, Brigham City, UT, August 20, 2006.

[6] Manfred Knabe, autobiography (unpublished); private collection.

[7] Düsseldorf city archive.

[8] Siegfried Helmut Schmidt, telephone interview with Judith Sartowski in German, February 25, 2008; summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[9] Düsseldorf city archive.