Dortmund Branch

Roger P.Minert, “Dortmund Branch,” in Under the Gun: West German and Austrian Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 339–348.

One of the largest cities in the Ruhr region of northwest Germany, Dortmund had 546,000 inhabitants in 1939. Eighteen miles east of Essen, Dortmund was an important industrial and transportation hub and therefore critical to Germany’s war effort.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints existed in Dortmund in the form of one branch with eighty-two members. Eighteen of those members held the priesthood, forty members were women over twelve, and eight were children when World War II approached in the late summer of 1939. The branch president at the time was W. Georg Gould, a missionary from the United States. His counselors were local members Franz Willkomm and Felix Kiltz. Other branch leaders were August Kiltz (Sunday School), August Bernhardt (YMMIA), Melitta Matuszewski (YWMIA), Antonin Kiltz (Relief Society), and Ernst Proll (genealogy). [1]

| Dortmund Branch [2] | 1939 |

| Elders | 6 |

| Priests | 1 |

| Teachers | 3 |

| Deacons | 8 |

| Other Adult Males | 16 |

| Adult Females | 40 |

| Male Children | 4 |

| Female Children | 4 |

| Total | 82 |

At the time, the Dortmund Branch met in rented rooms on the second floor of a building at Auf dem Berge 27. Erich Bernhardt (born 1920) had this recollection of the setting:

“Those were the first meeting rooms that we really liked. They were really nice rooms. It was a commercial building that was used for piano recitals [during the day]. About one hundred people could comfortably sit there and listen to the concerts. There were also a few smaller rooms on the sides. We used those to hold our Sunday School and MIA meetings. The large room could be divided into two smaller areas. The branch had about one hundred members on record, but forty to fifty were regularly in attendance in Sunday School or sacrament meetings.” [3]

The meeting schedule was as follows: Sunday School at 10:00 a.m. and sacrament meeting at 7:00 p.m. Mutual met on Tuesdays at 7:30 p.m. and the Relief Society met on Wednesdays at the same time. A genealogy class took place on the third Sunday of the month at 5:30 p.m.

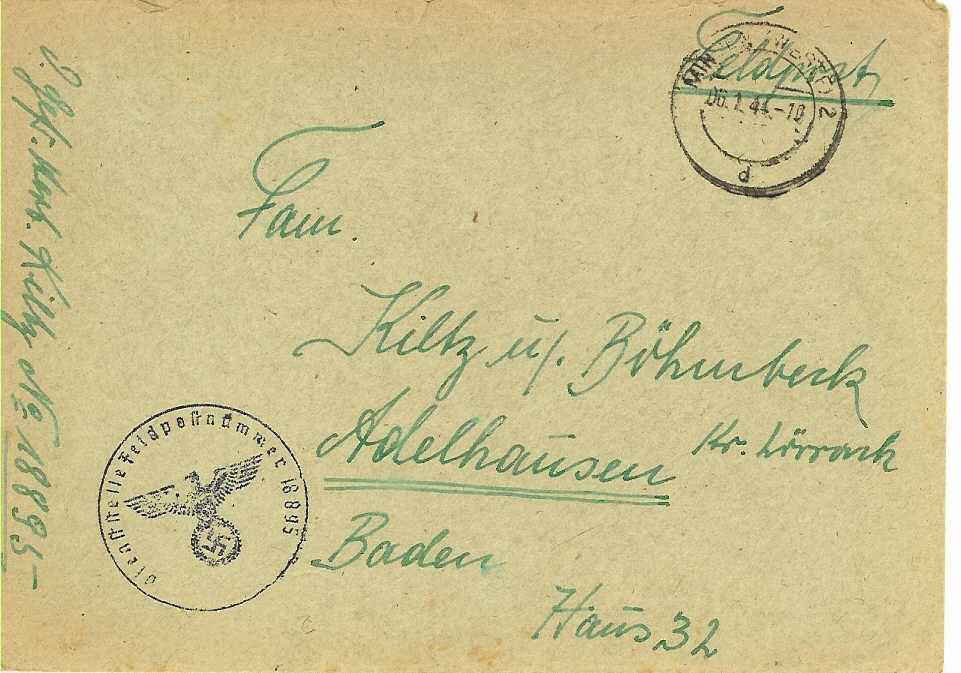

Fig. 1. Herbert Kiltz in Russia wrote this letter to his family in Germany in February 1944. He was reported missing in action four months later. (R. Asisi-Bonini)

Fig. 1. Herbert Kiltz in Russia wrote this letter to his family in Germany in February 1944. He was reported missing in action four months later. (R. Asisi-Bonini)

A dedicated branch clerk (who never mentioned himself by name) compiled a detailed history for the years 1939 to 1946. He made this comment on August 26, 1939: “A decisive event in the history of our branch occurred on August 26 when the missionaries were called away. W. George Gould left as our branch president along with John Wells due to the fact that war was anticipated. This was a painful loss to us to no longer have missionaries in our midst. The missionaries transferred their authority to Brother August Kiltz.” [4]

Young Paul Todebusch (born 1928) recalled the departure of the missionaries: “Before they left, they said good-bye to us. I remember that one of them was sitting on his suitcase, totally devastated that they had to leave.” [5]

The following is found in the branch history and provides evidence that a number of branch members were willing and able to make the short trip to Essen:

November 26, 1939: A branch conference was held and twenty-five persons attended.

December 15, 1939: Thirty-four branch members attended the district conference in Essen.

“I volunteered for the military because I really wanted to work for the aircraft maintenance department,” explained Erich Bernhardt. “I got in, and that was such a big blessing for me. I was in the Deutsche Luftwaffe, and trained to be an aircraft mechanic.” Little did Erich know that an even greater blessing came in the form of a miscommunication. He was sent to Norway in the place of another man but was kept there for five years because he had the required skills. In Norway, he had an opportunity rare for German LDS soldiers:

When I arrived in Norway in 1940, I sent a letter to my father asking him to provide me with the mission office address in Oslo because I wanted to make contact with the Church there. He sent me the address and I made contact with the mission office. They received me very nicely and I felt at home there. They treated me like a returned missionary although we, as the [German] soldiers, were occupying the country. We were not liked much by the Norwegians. But the membership made me a brother in the Church. And for the Saints there, that was the only vital thing to talk about. I kept contact with the Church in Oslo, Trondheim, Stavanger, and Narvik. It was a great blessing to be able to be a part of the Church, even in Norway.

Paul Todebusch was first a member of the Jungvolk and then of the Hitler Youth. He recalled his feelings about the experience:

I didn’t like to go and had a strong opinion against it. I didn’t like what they taught us and what they did in general. Once, we had to meet and stand in rows as the Jungvolk and the Hitler Youth together. We stood parallel to each other. All of sudden, everybody was fighting and somebody was stabbed to death. That incident truly made a difference in how I thought about the war.

We read again from the branch history:

February 2, 1941: Bernhard Willkomm and Melitta Matuszewski were married.

August 31, 1941: Annaliese Frölke was baptized during a district conference.

March 1942: The first great event of the year 1942 was the centennial celebration of the Relief Society on March 22. A fine program was presented in Essen and several members of our branch participated. It was a very spiritual event.

April 19, 1942: Elsa Dreger was baptized in Essen by Elder Gustav Dreger.

August 30, 1942. Nineteen persons attended a genealogical conference.

In the fall of 1942, Herbert Bergmann (born 1936) started school. Regarding the training of school children in the Third Reich years, he recalled the following: “We sang the national anthem every morning. We had to hold up our arms [in the Hitler salute] during the entire song, which was quite a challenge.” [6]

Fig. 2. Herbert Bergmann with the traditional cone full of treats on his first day of school. (H. Bergmann)

Fig. 2. Herbert Bergmann with the traditional cone full of treats on his first day of school. (H. Bergmann)

Herbert also recalled activities relating to the frequent air raids over Dortmund:

After every air raid, we would go out and collect all the shrapnel. We took a little box and even compared them in school to see who found the best pieces. In the beginning of the war, it was also more like a game still. We would see the planes and the Christbäume [flares] and would think it was fun. When we realized that the anti-aircraft was gone, war became more of a reality. It was a total nightmare. You sit in your basement, and you hear the bombs coming down with that shrill noise, and you know how close they are. Some sounded like they were right above us. Others were farther away. That is what we learned to distinguish. There were moments when I thought I would not survive. We were all crowded in the basement together—all six families of the house together. I remember one lady who went totally nuts. She started screaming, and they had to hold her down and put something over her mouth. She was never normal again.

Erich Bernhardt played a crucial role in the life of a young Norwegian Latter-day Saint in 1942, as Erich recalled:

The auditorium of the University of Oslo was burned down by students, some of whom were Nazi sympathizers. The branch president’s son was a student at that university but not a supporter of what had been done. Every student of the school was picked up by the police and taken to a concentration camp—so was he. The members of the family approached me and asked if I could help the police understand that the boy had had nothing to do with the incident and that he was not politically involved. I went to the German administration building in Oslo and talked to one of the leading officers. I explained that the boy’s family was religious and in no way harmful or politically active. About two weeks later, that student was called out of a large group of other students and told that he could go home. His name was Per Strand, a son of Einar A. Strand, who was the branch president.

One of the most vivid memories Eugen Bergmann (born 1934) had of wartime Dortmund was a confusing and sad one. He recounted:

My mother and I walked to Church one Sunday morning in Dortmund. The streetcars weren’t working anymore, so we had to walk the whole way. We had to cross a square, and we were just about in the middle of it when soldiers came and shot at the windows of the houses and yelled and commanded that everybody should leave the square immediately. I personally saw that day how the soldiers pulled Jewish people out of their homes and how they put the star [of David] on them. It was an awful sight for me. It got worse when I heard the soldiers call the Jews pigs. By that time, I had learned who Jewish people were. We had learned about them in school, and people in our neighborhood talked about them too. Especially some of the older students in my school talked about the Jews. I didn’t like that. [7]

Eugen’s father was a machinist in a steel factory. In 1942, he was transferred to a factory in Lebenstedt by Salzgitter (about 150 miles east of Dortmund). His wife and their baby followed him to Lebenstedt, but Eugen and his younger brother, Herbert, were sent to towns in the Black Forest in southern Germany. As two of the hundreds of thousands of children sent away from home under the program called Kinderlandverschickung, the boys had distinctly different experiences. Eugen told this story:

The families picked us up from the train station. I stayed with the Volz family [in Bad Sulzburg]. They had nine children—two girls and seven boys. The last one was drafted into the war, being seventeen years old, when I arrived. All of the children were gone. They didn’t own a farm—just a house with a yard. The father was working at a mill in a different town. I had a really good time there. We didn’t feel much of the war happening down there. I had to take care of some cows and about sixty rabbits. I also chopped wood, but I still had time to make friends with the locals. I went horseback riding. It was a pleasant time. In the beginning, I was very homesick. I missed my mother and my brothers. I was totally cut off from the Church. While I was away from home, I participated in a Lutheran religion class. I was also helping the bell ringer at church. But nobody gave me a hard time because of my religion. The family I lived with were North German Lutherans. I was in that town for about thirteen months.

Herbert Bergmann was not so fortunate when it came to his assignment with a family in the farming community of Grunern:

I lived in the Black Forest for that year, and I had to go to the Catholic Church, which was no fun at all—I hated it. We had Polish workers there; there was only supposed to be one but we had two for some reason. The second guy made great whiskey, and in the mornings I would go into the orchards to pick up all the fruit that was lying on the ground. I would take it to him, and he would make great whiskey from it. Other people from the town would also bring their fruit to him. It was such a small town—everybody knew everybody. One Polish worker did the regular farmwork—the other made whiskey.

Grete Bergmann rescued her son Herbert in early 1944, and Eugen’s father picked him up later that year. They all went to their new home in Lebenstedt where the boys could see their father every day for the first time in three years. As Eugen recalled, “We all came together again in a new house. It was a row house with a basement, first floor, and second floor. It was wall to wall with the neighbors. We had indoor plumbing but there was still no refrigerator or ice box. We were in that location when the war ended.”

Fig. 3. Members of the Dortmund Branch. (H. Bergmann)

Fig. 3. Members of the Dortmund Branch. (H. Bergmann)

The branch history includes the following report:

In the night of May 4–5, 1943, our branch meeting rooms on the second floor at Auf dem Berge 27 were destroyed in an air raid. All branch property was lost. Therefore we were not able to hold any meetings on May 9 and 16, because we had a lot of adjustments to make. . . . The Relief Society was also unable to hold any meetings. The Relief Society funds were distributed among needy members with the permission of district president Wilhelm Nitz and district Relief Society president Johanna Neumann. The first meeting after the destruction of our meeting rooms was held on May 23, 1943, in the apartment of Brother Scharf.

Eugen Bergmann recalled seeing the aftermath of the attack and specifically the remains of the church building at Auf dem Berge 27: “The whole front façade had collapsed to the ground. The pump organ was even hanging out over the edge of the destroyed building. We had a prayer meeting after that.”

The same attack that destroyed the branch’s meeting rooms destroyed the home of the Frölke family. According to their son Hans (born 1927), the war did not affect them much until 1943: “We were bombed out twice in two weeks. The first time, we lived in a large apartment building, and we were on the main floor; the house burned from the top to the bottom, and all the people from upstairs tried to take as many things outside as possible [while the fires burned]. Because we lived on the ground floor, my father broke the window with an ax, and we could carry lots of things out [before the fire burned down to our level].” [8]

The Frölke family then moved into the apartment of Hans’s paternal grandparents in a suburb of Dortmund. On May 23, that apartment was hit and Hans was nearly killed. He explained:

I always slept on the couch in the living room, and I rarely got up when there was an alarm, only when I heard bombs falling—then I got up. That particular night was the same. I waited until I heard [the airplanes] dropping bombs, and then I got up, left the room, and closed the door. I was standing at the front door when I heard a noise in the room that I was sleeping in—the entire room was burning.

That same night, Paul Todebusch’s father (who was not a member of the Church) was killed. He was in the official air-raid shelter at a local school. Fortunately, Paul and his mother were away visiting relatives. Soon after the attack, Sister Proll of the branch found Paul’s mother and informed her of the tragedy. As Paul later learned, his uncle had identified the body based on the fact that Paul’s father always wore brown shoes.Paul’s reaction to the loss of his father was predictable:

I was fifteen years old when my father died. We were very close—one heart and soul. Every night when my father came home, he would eat the dinner that my mother had prepared for him, wearing the slippers that we put by the door. He would read the newspaper and smoke his cigarette. He was a happy man. And he wasn’t against the church. He allowed my mother to go to church any time she wanted and to pay tithing.

The branch history offers these details about problems caused by the Gestapo:

“Brother August Bernhardt went to the Gestapo after our rooms were destroyed and asked for permission to hold home meetings. His request was denied. . . . Later, Brother August Kiltz went to the Gestapo with the same request and was given permission to hold home meetings. Our first meeting was held on September 26, 1943.”

Paul Todebusch recalled hearing his uncle describe the visit with the Gestapo:

My uncle [August Kiltz] had been blind since he was eighteen years old. He was invited to the office of the Gestapo with the Bible, the Book of Mormon, and the hymnbook and had to explain. All the members were nervous about what might happen. He went there, and they looked at everything he had brought. They then told him that we were not allowed to sing the hymns that used the word “Zion.” After that, we did not have any problems with the Gestapo anymore. We do not know who told the Gestapo about us.

More interesting details about the activities of the Dortmund Branch are these from the branch history:

October 10, 1943: August and Anna Grywatz were baptized along with Sister Schneider of Wuppertal; the baptism was performed by Bernhard Willkomm (a priest) in the city bathhouse in Hamm.

During the year 1943, several of our members were bombed out of their homes and had to be evacuated. Eight persons were evacuated. Despite these fateful developments, our members remained loyal to God and to the kingdom.

March 26, 1944: Branch president August Bernhardt was drafted by the Wehrmacht. . . . His successor is August Kiltz.

In February 1944, Herbert Kiltz of the Dortmund Branch wrote a letter to his family, who had been evacuated from Dortmund to southern Germany. He thanked them for sending Christmas packages, of which he had received no fewer than fifteen. In his opinion, he was eating better in Russia (“great meals!”) than was his family at home. He was in good health and looking forward to a furlough in March. Whether he ever actually left the combat zone for that furlough is not known. He was reported missing in action in Russia on June 7, 1944, and was declared dead by a court decree after the war. [9]

The hardships of living in an apartment that had been damaged by air raids was something Paul Todebusch could not forget:

Our home was not destroyed during the war, but our balcony was burned, and our windows burst. Our rooms were mostly intact, though. We put blankets and paper over the windows so it would not be so cold during the night. The electricity also did not work anymore. We fetched water a little farther away from the home. We had to carry it. I think it was more than one hundred meters away. We were allowed to get water twice a day.

In 1944, Hans Frölke and his schoolmates were assigned to operate antiaircraft batteries on the outskirts of Dortmund. By then, his mother and his sisters had been evacuated from the city and were living in Diersheim near Strasbourg, France. Following the “flak” assignment, all of the boys but Hans were drafted into the Reichsarbeitsdienst. Hans was sent to a premilitary conditioning camp for six weeks, where he had “a most wonderful time and learned a lot.”

Just a little girl, Rita Böhmbeck (born 1940) recalled a terrible experience that happened during an air raid over Dortmund in 1944:

We were trapped for the longest time in the bomb shelter in the Kesselstrasse. There was no food or drink for us. We knocked, but it took them so long to get us out. The door was made out of iron. It was actually a normal basement with a stronger door. It was so dark, and the people knocked on the stones that connected our basement with the neighboring one. The oxygen started to run out. People screamed and prayed and were scared. People in the neighboring house heard the screaming and got out us out through a small hole. I was just four years old. I remember everything. The sight I saw when I left the shelter was horrible. My mother put everything that she thought we would need in a crisis situation into a box and built wheels and attached those to the box. It was filled with silverware and plates. She also wrapped her accordion in blankets and my doll also. That night, we had to sleep on the street. [10]

The branch history provides this information about the disturbances caused by the war for members of the Dortmund Branch:

October 15, 1944: Due to the confusion caused by the huge air raid over Dortmund on October 6, we could not hold any meetings today. We had to rearrange our affairs totally. We could not hold our fast and testimony meeting on October 1, so we moved it to October 15.

Back at home for Christmas, Hans Frölke was alone with his father. Brother Frölke sent Hans to bring his mother and his sisters home because the American army was approaching the area. It was no longer safe to stay there. From Diersheim, the group traveled to Erfurt in central Germany to stay with friends. Shortly thereafter, they returned to Dortmund, . . .where an order awaited Hans: he was to report immediately for service with the Reichsarbeitsdienst. The date was January 1945.

Hans Frölke seemed to live a charmed life. Following six weeks of service in Schwerte (barely four miles from home), he was instructed to return to Dortmund and report for his next military assignment. While Hans was speaking to the officer who would have made that assignment, an air-raid siren and attack interrupted them, and no decision was made. After the attack, Hans’s father told him to take advantage of the confusion and join his mother in Erfurt. From there, he wrote to his father in Dortmund, but that turned out to be a mistake. The postal officials informed the military office in Dortmund of Hans’s location, and he received a notice to return immediately. As Hans recalled, “The Americans came to where we were the next day and freed me from having to report for duty.” Hans had avoided military duty at a time when young men were dying in great numbers in the hopeless attempt to keep Germany’s enemies from her gates.

The branch secretary explained some of the problems encountered by the Saints as the war drew to a close:

Despite the fact that the war’s disturbance has reached its zenith, we have tried to hold sacrament meetings. Nevertheless, we had to stop our meeting after the sacrament on March 11 because the alarms sounded and an attack followed. Some of the members were not able to attend the meeting. Constant alarms and attacks on March 18 prevented the members of the Dortmund Branch from attending the district conference, nor could we hold our own meetings on that day. The same was true on March 25, April 1, and April 8. Peace was restored in our city after the arrival of the American troops, and we were able to conduct a sacrament meeting without disturbance on April 15, 1945. On May 6, 1945, the Sunday School started again, having not met since October 15, 1944, due to the increasing dangerous conditions.

At the end of the war, Paul Todebusch was sixteen. He had already done a short stint with the Reichsarbeitsdienst and was actually drafted at the last minute by the Wehrmacht. Fortunately, he did not see any action and was at home in Dortmund when the American conquerors arrived. For some reason, his uncle suggested that Paul surrender to the Americans as a German soldier, even though he had already divested himself of his uniform. Dutifully, young Paul reported to a police officer: “He asked me if I was crazy and told me to go home. I went home and told this to my uncle, who sent me back. The second time, the police kept me, and after a while the Americans took me, put me on a truck, and sent me to a camp. I was a POW for about two months.”

Fig. 4. Members of the Dortmund Branch during the war. At far right is the blind branch president August Kilz. (H. Bergmann)

Fig. 4. Members of the Dortmund Branch during the war. At far right is the blind branch president August Kilz. (H. Bergmann)

As the war neared its conclusion, Herbert Bergmann was nine years old and able to understand some of the military action he witnessed. For example, he noticed that enemy airplanes did not attack the factory where his father worked, but instead tried to destroy the antiaircraft batteries that guarded that factory. “This went on for two days. The enemy sent five planes each time and they were all shot down. They shot down at least twenty-five planes. The factory functioned until the end of the war, and my father was never in danger.”

In Lebenstedt, the Bergmann boys watched as the American soldiers entered the town. In the confusion of the takeover, Eugen joined with other boys in collecting goods from destroyed stores in town. He later recalled finding a large box of cinnamon and a pair of boots. At the last minute, several fighter planes made another pass over the neighborhood; their machine guns left several holes in the walls of the Bergmann home. Eugen also remembered how the local mayor had wanted to surrender the town and therefore had raised a white flag above a bunker. A fanatic Hitler Youth boy then shot the mayor for committing treason.

When the war was finally over and Germany defeated, Herbert realized that his dream of joining the Hitler Youth would never be realized. “I wanted so badly to be in the Hitler Youth. All I had ever known in my young life was Hitler’s Germany.”

Erich Bernhardt was taken prisoner a few days after the war ended on May 8, 1945, and was kept in Stavanger, Norway, for about three months. As he recalled:

An American unit took us prisoner, and we were very well treated. A British unit occupied the air base that I was working in, and I worked for them during that time. I spoke a little English and was fluent in Norwegian by then, which allowed them to give me different assignments. I was very well liked. They even wanted to keep me from returning back to Germany in August of that year.

Fortunately, he was released that month and returned to Dortmund. A few weeks later, his father came home from a Soviet POW camp; he had been drafted in midwar. The family’s apartment had been damaged but was still inhabitable.

Erich Bernhardt’s assessed his wartime experiences in these words:

I had a very good experience in Norway. I was never in combat and never wounded. I had contact with other [German] LDS soldiers while I was there. They usually attended the meetings in the branches I was visiting so we met there. I was able to translate their testimonies into Norwegian. We talked about our experiences in the war, and they were all as well received in the branches as I was. Being in Norway taught me that the Church is the same everywhere in the world and that even in a war situation the Saints focus on what is most important and don’t let themselves become too influenced by politics.

Eugen Bergmann had the following to say about his mother, Grete, who had tried to raise her children without the help of their absent father:

My mother went through a challenging time, with four young children at home, her husband gone, but she always stayed faithful in the gospel. My mother always taught us from the scriptures that we took with us everywhere. She taught us Primary songs. She kept the gospel alive in our home although we couldn’t attend church [in Lebenstedt].

The city of Dortmund recorded 6,341 official deaths in air raids, but historians believe that the actual total was substantially higher. Ninety-nine percent of the city center was destroyed. The city was taken by the American army on April 13, 1945. [11]

In Memoriam

The following members of the Dortmund Branch did not survive World War II:

Gustav Ernst Dietrich b. Uderwangen, Ostpreußen, 28 Nov 1897; son of Hermann Dietrich and Rosine Neufang; bp. 4 Aug 1929; conf. 4 Aug 1929; m. Louise Wilhelmine Jeckstadt; 2 m. 5 May 1934, Anna Warbruck; d. industrial accident 24 Nov 1943 (FHL microfilm 68787, no. 3; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 512; FHL microfilm 68803, no. 512; IGI)

Margarete Hertel b. Althaidhof, Haidhof, Oberfranken, Bayern, 7 Jun 1884; dau. of Matheus Hertel and Katharina Hoffmann; bp. 6 Sep 1931; conf. 6 Sep 1931; d. heart attack 9 Apr 1941 (FHL microfilm 68787, no. 72; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 598; FHL microfilm 68803, no. 598; FHL microfilm 162782, 1935 census; IGI)

Herbert Felix Kiltz b. Elberfeld, Rheinprovinz, 4 Jan 1913; son of Felix Kiltz and Anna Paulina Lemmens; single; 1 child; bp. 17 Jan 1924; MIA Russia 7 Jun 1944; declared dead 31 Dec 1945 or 20 Mar 1954 (Deppe; FHL microfilm 271378, 1930 and 1935 censuses; IGI)

Anna Amalie Elisabeth Kreimeyer b. Höxter, Westfalen, 11 Dec 1897; dau. of Karl Heinrich Kreimeyer and Maria Elisabeth Schimpf; bp. 26 Aug 1925; conf. 26 Aug 1925; m. Dortmund, Westfalen 13 May 1921, Friedrich Julius Franz Todebusch; 2 children; d. heart disease Dortmund 3 Sep 1943; bur. Dortmund 7 Sep 1943 (FHL microfilm 68787, no. 46; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 374; FHL microfilm 68803, no. 374; Dortmund Branch history; IGI)

Joseph Sammler b. Wongrowitz, Bromberg, Posen, 18 Mar 1891; son of Adelbert Zbierski and Katharine Pazdzierska; bp. 14 Sep 1930; conf. 14 Sep 1930; m. 8 Jul 1921, Elfriede Kroll; d. stroke 20 Mar 1940 (FHL microfilm 68787, no. 36; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 560; IGI)

Friedrich Julius Franz Todebusch b. Duisburg, Rheinprovinz, 5 Jul 1895; son of Wilhelm Todebusch and Gertrud Heier; d. Dortmund, Westfalen, 24 May 1943.

Eugen Erwin Trenkle b. Dorndorf, Donaukreis, Württemberg, 15 Nov 1910; son of Eugen Trenkle and Louise Friedricke Deck; bp. 28 Jul 1920; conf. 28 Jul 1920; m. Anna Wösterfeld; k. in battle Eastern Front 15 Jan 1944 (FHL microfilm 68787, no. 51; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, 379; IGI)

Gerda Christine Wegener b. Dortmund, Westfalen, 13 Jun 1916; dau. of Gottlieb Otto Wegener and Auguste Ida Schönhoff; bp. 26 May 1929; conf. 26 May 1929; MIA 20 May 1943 (CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 498; FHL microfilm no. 245296, 1930 and 1935 censuses)

Gustav Wiemer b. Volmarstein, Westfalen, 17 Apr 1885; son of Gustav Wiemer and Liselotte Diekermann or Dieckertmann; bp. 30 Jul 1933; conf. 30 Jul 1933; ord. deacon 22 Aug 1937; d. 12 Jun 1944 (FHL microfilm 68787, no. 121; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 648; IGI)

Edmund Heinrich Willkomm b. Dortmund, Westfalen, Preussen, 10 Jul 1917; son of Franz Willkomm and Wladislawa Maria Tabaczynski; bp. 6 Sep 1931; conf. 6 Sep 1931; ord. deacon 30 Nov 1932; ord. teacher 31 Oct 1933; ord. priest 1 Dec 1935; k. in battle France 23 Mar 1940 (FHL microfilm 68787, no. 69; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 596; IGI)

Johann Willkomm b. Dortmund, Westfalen, Preussen, 2 Aug 1920; son of Franz Willkomm and Wladislawa Maria Tabaczynski; bp. 6 Sep 1931; conf. 6 Sep 1931; ord. deacon 30 Nov 1932; d. lung disease contracted while in the army Dortmund 20 Dec 1946 (FHL microfilm 68787, no. 71; FHL microfilm 68803, no. 594; CHL microfilm 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, all-mission list 1943–46, 186–87; IGI)

Notes

[1] West German Mission branch directory 1939, CHL 10045 11.

[2] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” 257, CHL CR 4 12.

[3] Erich Bernhardt, telephone interview with Jennifer Heckmann in German, March 31, 2009; unless otherwise noted, summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[4] Dortmund Branch history, 1939–46, 2, CHL LR 2296 22.

[5] Paul Erwin Todebusch, interview by the author in German, Dortmund, Germany, August 7, 2006.

[6] Herbert Bergmann, interview by the author, Provo, UT, April 2, 2009.

[7] Eugen Bergmann, telephone interview with the author, April 8, 2009.

[8] Hans Erwin Froelke, interview by Marion Wolfert, Salt Lake City, February 2006.

[9] Herbert Kiltz to his family, February 1944; used with the kind permission of Rita Assisi-Bonini.

[10] Rita Böhmbeck Assisi-Bonini, interview by the author in German, Dortmund, Germany, August 7, 2006.

[11] Dortmund city archive.