Bremen Branch

Roger P. Minert, “Bremen Branch, Bremen District,” in Under the Gun: West German and Austrian Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 72–78.

One of the principal port cities of the old Hanseatic League was Bremen, where 424,351 people lived in 1939. [1] This beautiful city on the Weser River was also home to a relatively strong branch of 158 Latter-day Saints.

The meetings were held at the time in the Guttemplerloge on Vegesackerstrasse. The branch observed the traditional meeting schedule of Sunday School at 10:00 a.m. and sacrament meeting in the evening. Other meetings were held on evenings during the week.

The branch leadership in July 1939 consisted of president Erwin Paul Gulla and his counselors, Georg Friedrich Schulze and Johann Heinrich Wöltjen. The branch directory shows that an American missionary was the superintendant of the Sunday School, but that all other leadership positions were held by members of the branch. [2]

| Bremen Branch [3] | 1939 |

| Elders | 5 |

| Priests | 3 |

| Teachers | 2 |

| Deacons | 15 |

| Other Adult Males | 29 |

| Adult Females | 93 |

| Male Children | 6 |

| Female Children | 5 |

| Total | 158 |

On Friday, September 1, 1939, the branch history reported numerous challenges faced by the Bremen Branch on the first day of the war:

The meeting hall of the Bremen Branch was confiscated by the German army. All requests, that at least one room [be] made available to the branch, are mockingly denied. “You are only trying to blunt the intellects of the people,” President Willy Deters is told. Meetings in Bremen are held again in the Guttemple Logenhaus at Vegesackerstrasse. However, it is only possible to hold one sacrament meeting on Sundays. At this time Brother Albert Adler, Brother Erwin Gulla and Brother Johann Wöltjen are called into the military service. The Bremen Branch is now under the direction of district president Willy Deters. [4]

Helene Deters (born 1904), the wife of the district president, recalled that British air raids over Bremen began almost immediately. Earlier, Hermann Goering, one of Hitler’s inner circle and head of the German air force, claimed that if an enemy airplane could drop a bomb on a German city, people could call him Meyer. [5] Generally a very happy young mother, Sister Deters had reason to be concerned about their safety during the many ensuing air raids against that important city: “There were no [air-raid] shelters at that time, and we huddled in our small cellar for what little protection it offered. Our house was so small that a little bomb could have easily destroyed the whole thing.” During one of the first air raids, she and Willy sat in a shelter without their son, who they believed was safe at another location. “Willy and I sat there hand in hand expecting the worst. But we were calm and ready to go [die] if that was the Lord’s will.” [6]

There is little information regarding the location of the branch meeting rooms after the Saints were required to vacate their rooms on Vegesackerstrasse. However, they indeed had found rooms, as evidenced by the report sent to the West German Mission office in Frankfurt on January 1, 1941. Some windows in the main meeting room had been damaged by recent air raids, “but the brethren have been able to repair them.” [7] Young Gerald Deters (born 1934) recalled meeting in the upstairs room of a restaurant. The building was very close to the Deters home at Wiedstrasse 42 and was not particularly impressive. [8]

When the attacks on Bremen increased in frequency and severity, the government recommended that mothers take their children to safer places. In January 1941, Willy Deters sent his wife and their son south all the way across the country to Straubing, Bavaria, where they were taken in by her sister, Emma Suelflow and her husband, Otto. Life there was much easier in many aspects, but Gerald had difficulty understanding the local dialect, which caused some problems in school, and Otto did not treat them kindly. During their year in Straubing, they were totally isolated from the Church, and Willy was able to visit them only once. In Gerald’s recollection, “It was just great to see him again, and we spent a most beautiful week in the Bavarian mountains, going on many hikes, and enjoying the magnificent scenery of that area. The time went too quickly.” [9]

Back in Bremen in early 1942, the Deters family did their best to weather the storm. In their absence, Erwin Gulla had been released from the military and had served as the branch president in Wilhelmshaven and then again in Bremen. The meeting rooms had been confiscated at least once for a few weeks, then returned to the Saints.

It was good to be together again, but life in Bremen was becoming primarily a question of survival for the Deters family. Helene was working as a bookkeeper, and this allowed the family to enjoy a comfortable lifestyle, but there was rarely time for entertainment, as Gerald wrote: “For the next six months or so our routine was very simple: Mutti and Pappi went to work during the day, and I went to school. We came home, ate our supper, and then went to the air shelter for the night. It was really something to look forward to every day.” [10]

On one occasion, the Deters family was visited by a branch member on leave from the Eastern Front. When Gerald learned of the constant attacks, he said that he had never experienced an air raid and wondered what it would be like. A few hours later, he found out. The roar of enemy airplanes was heard (even though no sirens sounded), and everybody ran for a large concrete bunker down the street. The bombs began to fall even before they reached the shelter, so they took refuge elsewhere. The next morning, the guest stated that it was quieter in Russia and that “he could hardly believe that we were going through this type of experience nearly every night.” [11]

In early 1943, Willy Deters was transferred to his company’s facility in Verden, twenty miles southeast of Bremen. Helene was fortunate to find employment at the same place, and the family moved into a small home on Brunnenweg. From there it was a short train ride back to church in Bremen, but on occasion the air raids made it impossible for them to make the trip. Gerald Deters recalled enjoying the small-town atmosphere and playing cowboys and Indians with local boys in the forest.

Fig. 1. The Deters family moved into the right half of this two-family home on Brunnenweg in Verden in 1943. They lived there for six years. (G. Deters)

Fig. 1. The Deters family moved into the right half of this two-family home on Brunnenweg in Verden in 1943. They lived there for six years. (G. Deters)

Among the members of the Bremen Branch were several persons living in the city of Oldenburg, twenty-five miles to the east. Gustav Christmann and his family moved there from Heilbronn (Stuttgart District) in connection with his military assignment. Frida Bock came during the war to join the company of the state theater as a soprano. Other members there were Wübbedina Koeller and Wilhelmine Grunow and her mother and sister. They were able to attend meetings in Bremen until the last months of the war when crucial railroad bridges were destroyed and the trip became too dangerous. [12]

The Saints in Bremen were in constant danger, as was reflected in the branch history on May 31, 1943:

(Very heavy air raid on Pentecost): One bomb hit the house of the Bornemanns. It dug a deep hole in the middle of the cellar where these Saints and other occupants of the apartment house were staying. Luckily, it was a dud and did not explode so that they were able to leave the cellar unharmed. Here again is a wonderful manifestation of the protecting power of the Lord. [13]

Fortunately, important events in the lives of individual members could still take place in that environment. Gerald Deters was baptized in an indoor pool in the city of Bremerhaven on October 3, 1943. But the years of his childhood passed, and he was automatically inducted into the Jungvolk, the first phase of the Hitler Youth program, in the fall of 1944.

Willy Deters was required to join the National Socialist Party due to his employment. He wore the required swastika pin on his collar, but was an outspoken opponent of the party and did not attend meetings. According to Gerald, Willy had to be admonished by his wife on many occasions to keep his voice down when he criticized the government, especially when they were out in public. Because his hearing was bad, he compensated with a voice that he likely did not know was loud. Despite his objections, his son Gerald attended meetings of the Jungvolk that took place at least twice a week.

Fig. 2. Willy Deters with his wife, Helene, and son, Gerald, after the war. (G. Deters)

Fig. 2. Willy Deters with his wife, Helene, and son, Gerald, after the war. (G. Deters)

Gerald was an enthusiastic member of the Jungvolk—very much what the government hoped he would become. He later wrote about marching in parades and going to movies where scenes of heroism under fire were common. Fortunately, his dreams of becoming a tank commander or serving aboard a PT boat or a submarine would never have time to become reality, for the war would soon be over.

The Führer, Adolf Hitler, narrowly escaped an attempt on his life on July 20, 1944, when a bomb was placed in a conference room just a few feet from where he was standing. Gerald Deters recalled being shocked to hear of the assassination attempt in a radio broadcast later that day: “We were so relieved to hear that he was safe. . . . Knowing how my dad felt about Hitler [he disapproved], I think he was not surprised to hear that somebody tried to murder him.” [14]

The night of August 18–19, 1944, was a very hard one for members of the Bremen Branch, according to the branch history:

The meeting hall of the Bremen Branch was destroyed on the night of August 18, 1944. Ninety-five percent of the members of the Bremen Branch have lost their homes, including all their belongings. All the property of the branch, chairs, tables, dinnerware, etcetera., which had been given to the members for safekeeping in their homes, has been completely destroyed. All the homes, where branch property was stored, were destroyed. [15]

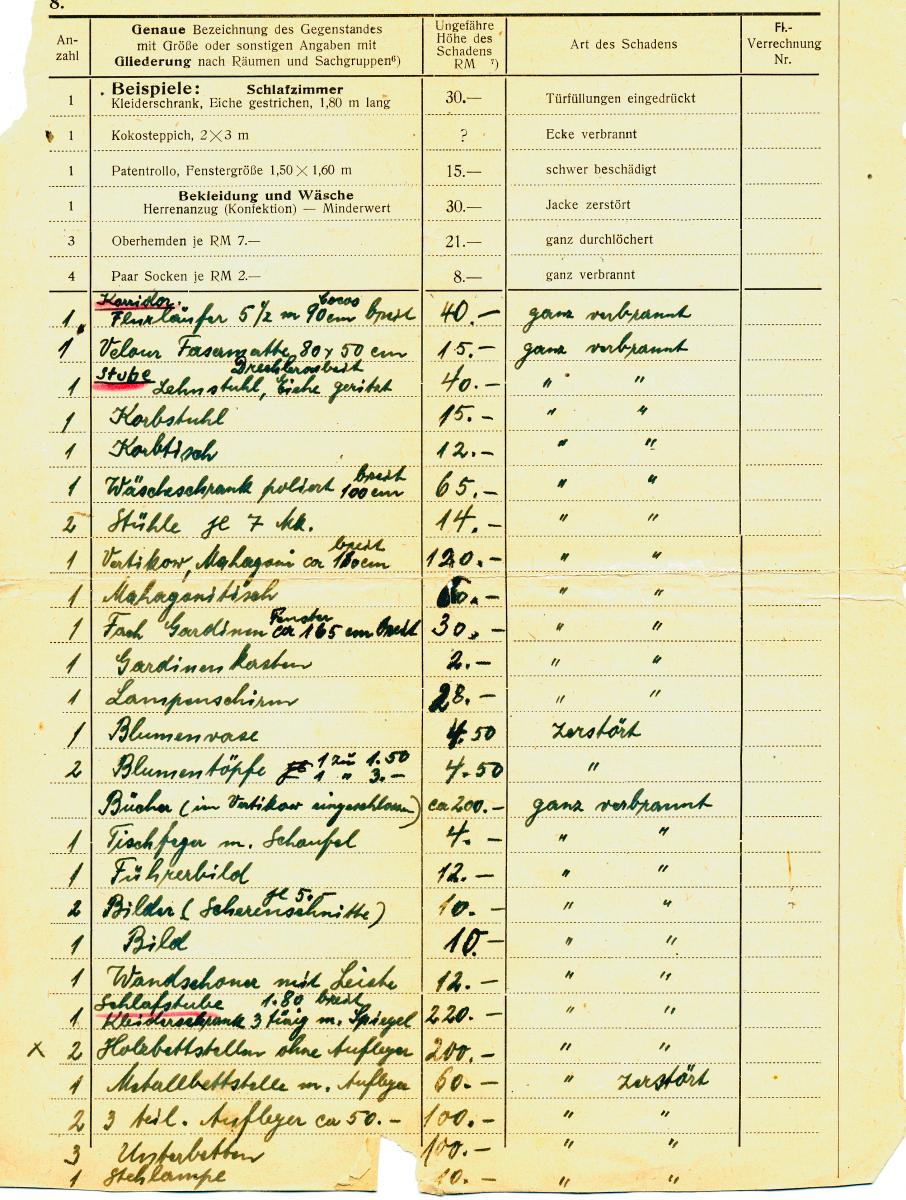

The Deters family had transferred some of their property from the apartment at Wiedstrasse 42 to the house in Verden by then, but most of their belongings were in Bremen that night and subsequently were destroyed. In those days, it was still possible for German citizens to appeal to the government for reparations payments after air raids, and Willy Deters did precisely that. In a six-page report, he detailed the property lost when an incendiary bomb reduced the home and its contents to ashes. The report lists ninety-eight specific items (or types of items)—including the obligatory portrait of Adolf Hitler, which that was valued at 12 Reichsmark. The declared value of the items inventoried was approximately two thousand Reichsmark, even though some items had no listed replacement value. [16]

Fig. 3. Willy Deters submitted an inventory of personal property lost when the family’s apartment was destroyed in an air raid. The government compensated citizens in part for their losses. (G. Deters)

Fig. 3. Willy Deters submitted an inventory of personal property lost when the family’s apartment was destroyed in an air raid. The government compensated citizens in part for their losses. (G. Deters)

Following the attack, the members of the Bremen Branch could not find rooms in which to hold their meetings. They began to meet in groups of eight or ten wherever they could. By January 1945, Willy Deters reported to the mission leaders that it was almost impossible to hold meetings in Bremen. From Verden, he could hardly ever find a train to take his family to Bremen or to go even farther north to visit the branches in Wesermünde-Lehe and Wilhelmshaven. [17] For the Deters family, church attendance was essentially on hold.

In April 1945, the British army approached Verden and was still encountering resistance from German soldiers determined to defend the fatherland. Gerald recalled that his father took the family to a farm about four miles from Verden, where it appeared to be safer, but his calculations were faulty: the family soon found themselves in the worst possible position—precisely between the attackers and the defenders. One night, the family huddled in a barn, sitting atop a pile of potatoes and praying for deliverance, while the opposing forces exchanged round after round of artillery fire and rockets. According to Gerald, “that was probably the night when we really learned how to pray, [even though] we had done it before. It was the most horrible night.” A few hours later, the British tanks rolled into view, and the war was over for the Deters family. They moved back to Verden on April 20, 1945—Adolf Hitler’s birthday. [18]

Two reports sent from Bremen to the mission office in Frankfurt in the late summer of 1945 reflect the spirit of revival among the Latter-day Saints in Bremen once peace was established:

August 25, 1945, Sunday: Ten U.S. soldiers visited the meeting in Bremen. The joy was great when we found that Elder . . . Robins, a missionary who had labored in Bremen, was among this group. This was for us, as well as for the brethren from America, cause for great joy. After six years of war and destruction we again had brethren from Zion among us. [19]

September 16, 1945, Sunday: With the help of Col. Horace W. Shurtleff, a meeting hall for the Bremen Branch has been secured in the Wilhadistrasse 1. Starting this day regular meetings were held there. This first meeting was attended by 55 persons. The attendance is increasing constantly. [20]

By April 26, 1945, when the British army entered the city, Bremen had been bombed in 173 attacks that took the lives of at least 4,125 people. Sixty-two percent of the dwellings had been destroyed, and the city had lost 12,996 of its residents in military service. [21] Although most of the Latter-day Saints were among those who had lost their homes, they had been able to stay in or return to Bremen and were soon busy improving the condition of the branch there.

The suffering of the Saints in Bremen is described in depth in the letters written by Relief Society members to Ellen Cheney of San Diego in the years after the war. Sister Cheney directed a program to provide food and clothing to the surviving members of the Bremen Branch. In their letters of thanks, they told about their experiences and feelings. For example, Elli Ellinghaus wrote the following on December 8, 1946:

The Lehmkuhls lost everything during the war. Even their dearest, there [sic] only 20 year old boy was lost in Russia. Yes the last years of the war were for us very very hard. Many times in our troubles we cried to God for help. . . . We have had help from the Lord many times when we did not know where to turn to, there was some unexpected help for us. [22]

Lina Schubert wrote this message to Sister Cheney on November 16, 1946:

Whoever went through the war here with the many bombings, know how much was lost to the flames. Many nerves are shocked as a result. Many are poor, they have no bed, no home, everything lost, and for what? Then all the prisoners of war who have not been returned. Why do they keep them? . . . It is a bad place to live here now, the need for food is great, there is nothing at all to buy. [23]

Sister Schubert wrote again on April 26, 1947:

I have waited so long for the return of my boy who is still a prisoner of war in Egypt. It will soon be his fifth summer there and I can tell how much he misses his family. We can only hope that his wish will soon be fulfilled. . . . It was two years ago today that our enemies appeared in our city. We spent two full days in the air raid shelters and when we came out, our city looked like a desert. Everything was destroyed. There was no water, no power, no gas, no coal, no food. Nothing but destruction everywhere. The people who didn’t believe in God were moaning and groaning. May God bless us if we but stay on the straight and narrow path and do no evil. [24]

The sadness of these letters and many others with similar content is overshadowed by the gratitude expressed by the surviving Bremen Saints for the protection they received from their God and the brotherhood and sisterhood they shared during the difficult war years.

In Memoriam

The following members of the Bremen Branch did not survive World War II:

Heinrich Adler b. Bremen 6 Jun 1926; son of Heinrich Adler and Anna Auguste Drönner; bp. 22 Jun 1934; conf. 22 Jun 1934; ord. deacon 18 Aug 1940; k. in battle Russia 15 Jul 1944; bur. Orglandes, France (CHL microfilm 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, 90–91; FHL microfilm no. 68785, no. 111; www.volksbund.de)

Wilhelm Albert Adler b. Bremen 28 Feb 1913; son of Heinrich Adler and Anna Augusta Drönner; bp. 19 Dec 1922; conf. 19 Dec 1922; ord. deacon 8 Jan 1928; ord. teacher 1 Jun 1930; ord. priest 23 Apr 1934; ord. elder 6 Sep 1936; m. 30 Jun 1934, Anna Bodnau; rifleman; k. in battle 28 May 1940; bur. Noyers-Pont-Maugis, France (FHL microfilm 68785, no. 2; www.volksbund.de)

Mathilda Andermann b. Geestemünde, Berden, Hannover, 24 Mar 1891; dau. of Friedrich Andermann and Mathilde Behrens; bp. 21 Sep 1934; conf. 21 Sep 1934; m. 24 Mar 1923, Ernst Kassner; d. abdominal cancer 6 Jun 1940 (FHL microfilm 68785, no. 253)

Hermine Katharine Margarethe Behrens b. Neuenburg, Oldenburg, 13 Mar 1863; dau. of Johann Friedrich Behrens and Hella Margarethe Meyer; bp. 26 Apr 1928; conf. 26 Apr 1928; m. 21 Jun 1899, Johann Friedr. Ortgiesen; div.; d. cardiac insufficiency 2 Jan 1942 (FHL microfilm 68785, no. 152; IGI)

Aug. Emilie Karoline Boeck b. Nörenberg, Gaatzig, Pommern, 8 Nov 1863; dau. of Wilhelm Boeck and Karoline Giese; bp. 20 Jul 1918; conf. 20 Jul 1918; m. —— Kolbe; d. heart attack 28 Jan 1944 (FHL microfilm 68785, no. 26)

Karoline Elise Minna Dauelsberg b. Stolzenau, Berden, Hannover, 11 Feb 1866; dau. of Christian Gerhard Fr. H. Dauelsberg and Auguste Reymann; bp. 31 Aug 1906; conf. 31 Aug 1906; m. 7 May 1892, Ernst Heinrich Jäkel; d. stroke 5 Apr 1942 (FHL microfilm 68785, no. 29)

Tjaltje DeJong b. Opende, Gröningen, Netherlands, 2 Jan 1893; dau. of Andreas DeJong and Sjonkje Ras; bp. 10 Aug 1922; conf. 10 Aug 1922; m. —— Dittrich; d. pneumonia 15 Feb 1942 (FHL microfilm 68785, no. 90; FHL microfilm 25755, 1930 census)

Marianne Hammerski b. Klonia, Konitz, Westpreussen, 2 Jul 1865; dau. of Josef Hamerski and Clara Florentina Zielinski; bp. 20 Aug 1939; conf. 20 Aug 1939; m. Wilhelmsburg, Hamburg, 6 Oct 1894, Johann Hermann Christoph Wesseloh; 7 children; d. senility Bremen 17 Nov 1941 (FHL microfilm 68785, no. 292; IGI)

Mathilde Katharine Rudolfine Klempel b. Valpariso, Metropolitana, Chile, 7 May 1873; dau. of Otto Samuel Klempel and Hanna Ernestine Lina Fleissner; bp. 18 Jun 1926; conf. 18 Jun 1926; d. heart attack 2 Dec 1940 (FHL microfilm 68785, no. 108; IGI)

Hermann Albert Koslowski b. Bremen, 22 Feb 1913; son of Max Koslowski and Auguste Schwettling; bp. 28 Jun 1923; conf. 28 Jun 1923; k. in battle Artemowsk, Russia, 1943 (CHL microfilm 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, 170–71; FHL microfilm 68785, no. 38)

Emilie Lohwasser b. Neudeck, Österreich, 8 Mar 1868; bp. 31 May 1924; conf. 1 Jun 1924; m. 16 May 1890, Ludwig Fleischer; d. senility 14 Feb 1941 (FHL microfilm 68785, no. 82)

Sophie Marie Mühlenbruck b. Kirchboitzen, Fallingbostel, Hannover, 13 Feb 1872; dau. of Hermann Mühlenbruck and Louise M. Dorothea Grosse; bp. 29 Oct 1907; conf. 19 Oct 1907; m. 6 Apr 1895, Heinrich Thom; k. air raid Bremen 23 Apr 1945 (CHL microfilm 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, 122–23; FHL microfilm 68785, no. 64)

Julianne Gesine Wilhelmine Paul b. Spain 14 Jun 1873; dau. of Julius Paul and Sophie von Südwenz; bp. Hamburg 31 May 1924; conf. 1 Jun 1924; d. 22 Jul 1943 (FHL microfilm 68785, no. 79; IGI)

Karl Günter Rau b. Heilbronn, Mittelfranken, Bayern, 6 Oct 1935; son of Gustav Christmann and Else Rau; k. air raid Bremen 17 Apr 1945 (CHL microfilm 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, 122–23; FHL microfilm 68785, no. 286; IGI)

Bruen Schroeder b. Mahndorf, Achim, Hannover, 3 Jan 1883; son of Bruen Schröder and Gesche Kuhlmann; bp. 10 May 1913; d. 18 Mar 1942 (CHL CR 375 8 2458; IGI)

Bruno Gerhard Schulze b. Bremen 5 May 1902; son of Georg Friedrich Schulze and Hermine Wagner; bp. 3 Mar 1911; conf. 3 Mar 1911; m. 5 May 1927, Marichen Dreke; k. air raid Bremen 24 Jun 1944 (CHL microfilm 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, 90–91; FHL microfilm 68785, no. 58)

Emmi Eliese von Hefen b. Strohauserdeich, Rodenkirchen, Oldenburg, 1 Mar 1869; dau. of Cornelius von Hefen and Marie Schroeder; bp. 5 Jul 1921; conf. 5 Jul 1921; m. —— Freudenberg, d. 2 Jul 1943 (FHL microfilm 68785, no. 16)

Geertje Wagener b. Bunde, Weener, Ostfriesland, Hannover, 27 Aug 1874; dau. of Koene Harms Wagener and Weldelke Bruns; bp. 5 May 1908; conf. 5 May 1908; d. heart attack 17 Oct 1941 (FHL microfilm 68785, no. 67; IGI)

Johann Hermann Christoph Wesseloh b. Fintel, Hannover, 17 Sep 1867; son of Johann Wesseloh and Gesche Windeler; bp. 20 Aug 1937; conf. 10 Aug 1937; m. Wilhelmsburg, Harburg, Hannover, 6 Oct 1894, Marianne Hammerski; 7 children; d. intestinal cancer Wandsbek, Altona, Schleswig-Holstein, 29 or 30 May 1942 (FHL microfilm 68785, no. 293; IGI)

Katharina Wissenbach b. Gundhelm, Schlüchtern, Hessen-Nassau, 24 May 1860; dau. of Franz Wissenbach and Margaretha Hummel; bp. 20 Aug 1938; conf. 20 Aug 1938; m. 12 Aug 1888, Heinrich Lüdecke; d. senility 22 Feb 1941 (FHL microfilm 68785, no. 306; IGI)

Betty Wöltjen b. Rautendorf, Osterholz, Hannover, 18 Mar 1889; dau. of Johann Hinrich Wöltjen and Margarethe Adelheid Viehl; bp. 15 Jun 1929; conf. 15 Jun 1929; m. 27 Apr 1912; 2m. 21 Feb 1921, Ernst Otto Emil Greier; 3m. 25 Jun 1938, Ferdinand Martin Tubbe; k. air raid Bremen 26 Nov 1943 (CHL microfilm 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, 58–59; FHL microfilm 68785, no. 154; IGI)

Johann Hinrich Wöltjen b. Rautendorf, Osterholz, Hannover, 25 Apr 1887; son of Johann Hinrich Wöltjen and Margarethe Adelheid Viehl; bp. 6 Jun 1925; conf. 6 Jun 1925; ord. deacon 1 Aug 1926; ord. teacher 28 Oct 1928; ord. priest 1 Jun 1930; m. Bremen 18 Oct 1913, Berta Henschel; six children; d. pleurisy Bremen 11 Mar 1945 (FHL microfilm 68785, no. 96; IGI)

Catharine Marie Wübbenhorst b. Sandhorst, Aurich, Hannover, 12 Mar 1864; dau. of Johann Christian Wübbenhorst and Marg. Folina Götz; bp. 10 Jun 1916; conf. 10 Jun 1916; m. 18 Dec 1893, Heinrich Bengson; d. heart attack 15 Jan 1942 (FHL microfilm 68785, no. 8)

Notes

[1] Bremen city archive.

[2] West German Mission branch directory, 1939, CHL LR 10045 11.

[3] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” CHL CR 4 12, 257.

[4] West German Mission manuscript history, CHL B 1381:3.

[5] Germans would soon be telling countless jokes featuring “Herr Meyer” in an obvious reference to Goering.

[6] Helene Albetzky Deters, autobiography (unpublished), private collection.

[7] West German Mission manuscript history, CHL B 1381:5.

[8] Gerald Deters, interview by the author, Bountiful, Utah, July 1, 2009.

[9] Gerald Deters, autobiography (unpublished), private collection.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Erwin Büsing, “Beitrag zur Geschichte der Gemeinde Oldenburg von 1946 bis 2007” (unpublished), private collection.

[13] West German Mission manuscript history, CHL B 1381:7.

[14] Gerald Deters, interview. The incident occurred at Hitler’s headquarters for the Eastern Front near Rastenburg, East Prussia. The bomb was planted by Claus Graf Schenk von Stauffenberg, who was executed for treason later that same day in Berlin.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Sachschaden-Antrag submitted by Wilhelm Deters to the city of Bremen on September 1, 1944; private collection.

[17] West German Mission manuscript history, CHL B 1381:8.

[18] Gerald Deters, interview.

[19] West German Mission manuscript history, CHL B. 1381:9.

[20] West German Mission manuscript history, CHL B. 1381:10.

[21] Bremen city archive.

[22] Elli Ellinghaus to Ellen Cheney, December 8, 1946; used by permission of George and Lorene Runyan.

[23] Lina Schubert to Ellen Cheney, November 16, 1946; used by permission of George and Lorene Runyan.

[24] Lina Schubert to Ellen Cheney, April 26, 1947; used by permission of George and Lorene Runyan.