Bielefeld Branch

Roger P. Minert, “Bielefeld Branch, Bielefeld District,” in Under the Gun: West German and Austrian Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 46–56.

One of the largest branches in the West German Mission in 1939, the Bielefeld Branch numbered 144 members, fully one-sixth of whom were priesthood holders. The city of Bielefeld, located in the northeast corner of the state of Westphalia, had a population of 126,711 at the time. [1]

The president of the Bielefeld Branch from 1938 until after the war was Heinrich Recksiek. [2] He lived with his family on the grounds of the Ross & Kahn clothing factory at Friedenstrasse 32, where he worked as a mechanic and custodian. Anna Recksiek was the branch Relief Society president during the war and was not employed. Their son, Heinz (born 1924), recalled that both branch and district conferences were held in the meeting hall of the clothing factory on several occasions during the first years of the war. [3] This was an important benefit of the branch president’s employment, as was the use of the company automobile.

| Bielefeld Branch[4] | 1939 |

| Elders | 7 |

| Priests | 4 |

| Teachers | 3 |

| Deacons | 10 |

| Other Adult Males | 25 |

| Adult Females | 80 |

| Male Children | 4 |

| Female Children | 11 |

| Total | 144 |

According to the 1939 directory of the West German Mission, the Bielefeld Branch met in rooms at Ravensbergerstrasse 45. Elfriede Recksiek (born 1925) described the rooms rented in that building:

There was one large room, and two smaller ones of which we used one as the cloak room. We also had restrooms in the building. The rooms were on the main floor of the building. I also remember seeing a sign of our church in the front of the building that indicated that we met there. We had chairs in our rooms, not benches, but that allowed us to move them around. There was also a raised platform in the front of the room. A choir sang sometimes, and we also had a piano and an organ that we could use to accompany. I would say that we had an attendance of about 50–60 people there on Sunday. I can remember having pictures of Jesus Christ on the wall. [5]

The branch observed the usual meeting schedule, holding Sunday school at 10:00 a.m. and sacrament meeting at 7:00 p.m. Each organization had a full complement of leaders. The MIA and the Primary met on Tuesday evening, and the priesthood meeting was held on Thursday evening. As of July 1939, an English class took place on Wednesdays at 8:30 p.m. and a teacher training class on the first Sunday of each month after sacrament meeting. [6] There was certainly no lack of activities in this branch when the war began. Heinz had this to say about the young people in the branch: “The branch was quite large with many children. We had good relationships and interactions among the young people. Whenever we got together, we had a wonderful and fun time. . . . We had many outings with the MIA.”

Elfriede recalled the following about the routine of going to church:

It took us about twenty to thirty minutes to reach the meeting rooms when we walked. My mother always said that if there are no bombs, we could walk. We walked there in the morning, came back for lunch, and went back for sacrament meeting, which started at 7:00 p.m. Especially in the winter, it was dark and there were hardly any streetlights left [due to the blackout]. But it was safe for us. We also wore a fluorescent button on our jackets so that we would be seen in the dark.

Fig. 1. Bielefeld Branch members in the main meeting room in about 1939. (E. Schmitz Michaelis)

Fig. 1. Bielefeld Branch members in the main meeting room in about 1939. (E. Schmitz Michaelis)

Eleonore Schmitz (born 1936) recalled that as a little girl, she and her younger sister Rosemary sang duets:

My aunt taught us some hymns, and we had to sing them standing next to the pump organ. Rosemary must have been six, and I was seven. We did it more than once. In one of the hymns, we started singing faster, and the sister who was playing the organ had a hard time keeping up with us. [7]

The history of the Bielefeld Branch reports some of the difficulties experienced by the Saints in that city very early on:

During the war years, attendance at branch meetings decreased significantly. For this reason, we had to rent smaller rooms on Friedrichstrasse and until November 23, 1941 we rented rooms from Mr. Schlüter on Ravensbergerstrasse. Under those difficult circumstances we moved into other rooms at Am Sparrenberg 8 as of November 30, 1941. At that location we used a large meeting hall and a separate room in the back. [8]

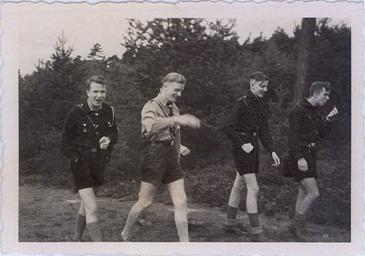

Fig. 2. Heinz Recksiek (in light shirt) with members of his Hitler Youth unit in about 1938. (H. Recksiek)

Fig. 2. Heinz Recksiek (in light shirt) with members of his Hitler Youth unit in about 1938. (H. Recksiek)

Heinz Recksiek recalled the news of war with Poland in September 1939:

At that time, I was only fifteen years old and a member of the Hitler Youth. We were more or less obligated to join the Hitler Youth. I remember being told that the Polish people were persecuting the German families who still lived in that [Polish] corridor, which was given back to Poland after World War I. And I remember Hitler saying that we were now justified in attacking Poland. As young men only fifteen years of age, we believed that.

One of the first young men of the Bielefeld Branch to wear the uniform of the Wehrmacht was Werner Niebuhr (born 1916). In June 1941, he found himself among the soldiers invading the Soviet Union. He had expected to experience terrible things in combat, but what he saw in Russia was shocking. He recalled:

As we tried to shoot at the bunkers we found out that [the enemy] had women and children bound with rope in front of the bunkers so we would not shoot at the bunkers. . . . Something else that the Russians had done that I have never seen before . . . was [the enemy] had put their own soldiers in foxholes, buried them with dirt to the chest, put in front of them pile of ammunition and a rifle so that they could shoot at us and could not retreat when we came. I have never seen anything so inhumane as this before. [9]

Werner’s unit moved to many locations along the southern reaches of the Russian Front, including the Crimea, where a belated message from home reached him in February 1942. His wife, Hilda, had given birth to their first child the previous October, but the child was stillborn. Under a new Wehrmacht regulation, Werner was allowed a short leave due to this death in the family.

Shortly after his return to Russia in March 1942, Werner ran into another member of the Bielefeld Branch, Walter Recksiek (born 1919). Walter had volunteered for service in the Waffen-SS, where he had been promised better conditions, equipment, transportation, etc. However, he had found out that service with the Waffen-SS was not all pleasant. Werner recalled Walter’s words in Russia: “If I knew then what I know now, I would never have joined the Waffen-SS.” It is very possible that Walter’s unit had been in the area behind the lines where political prisoners and Jews were being sought out for Sonderbehandlung (“special treatment,” a euphemism for murder). [10]

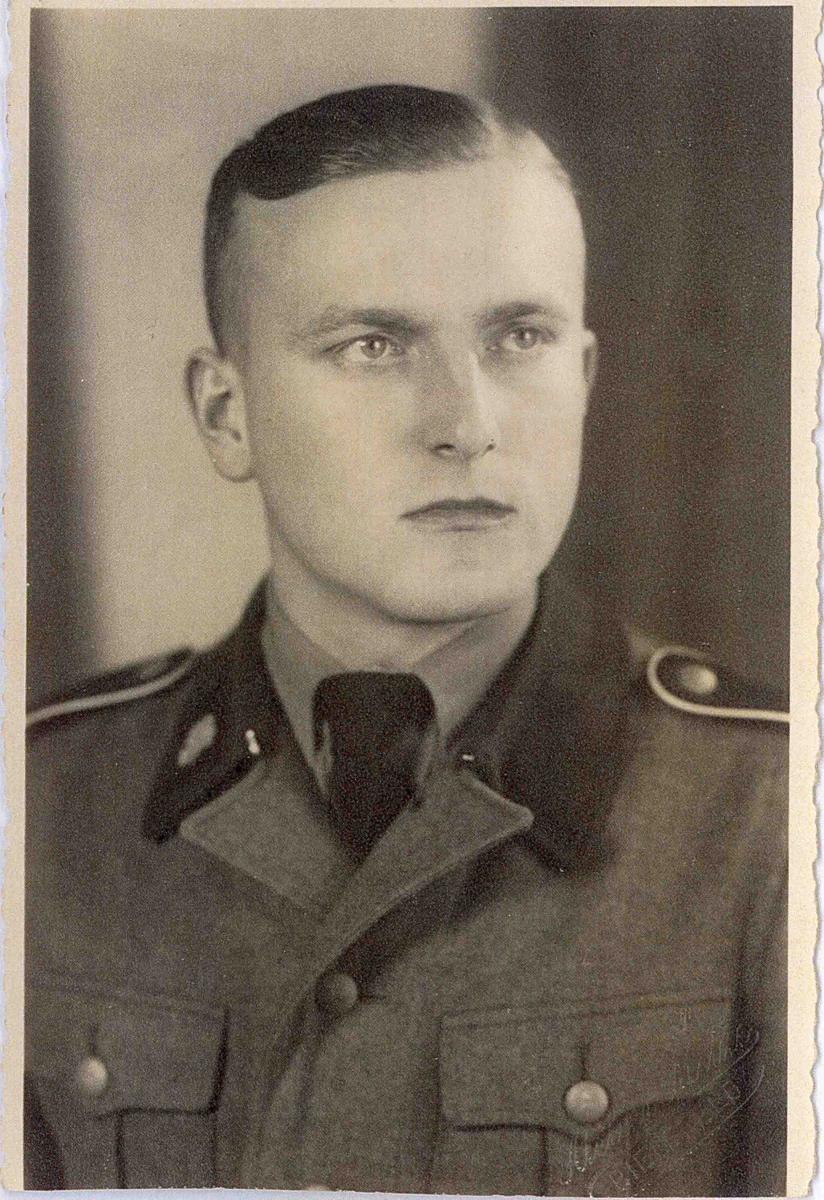

Fig. 3. Heinz Recksiek as a Wehrmacht soldier. (H. Recksiek)

Fig. 3. Heinz Recksiek as a Wehrmacht soldier. (H. Recksiek)

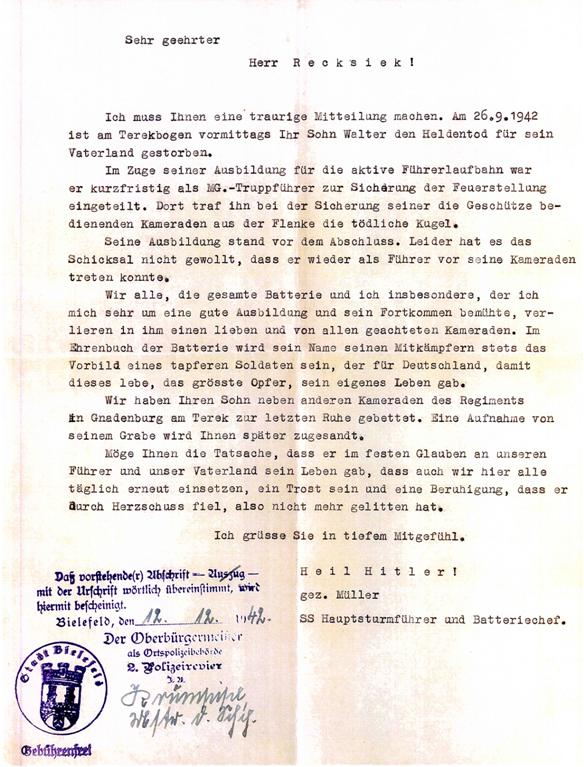

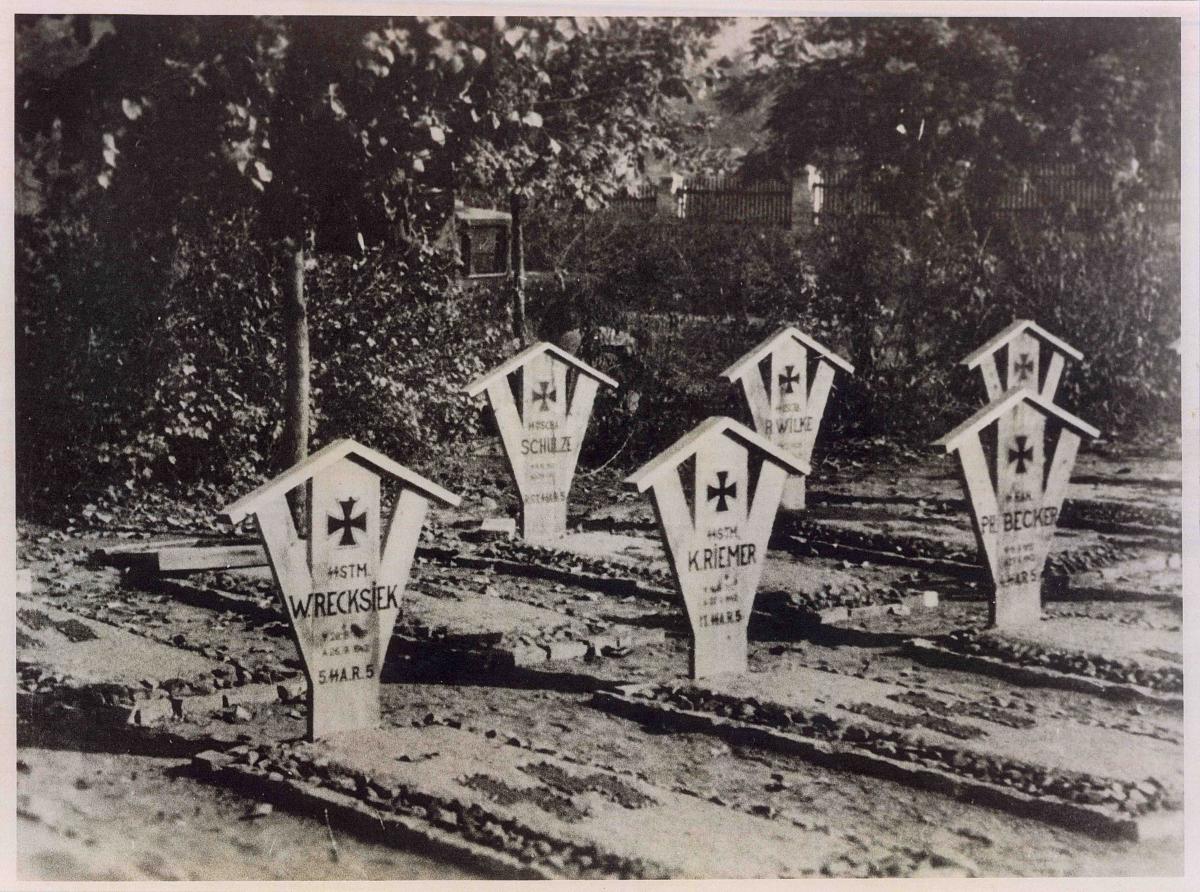

Just a few months later, the Recksiek family received the letter feared by every German family in those years: “It is my sad duty to inform you that your son, Walter Recksiek, gave his life for his country near Terekbogen on the morning of September 26, 1942.” Unlike many German families, the Recksieks at least were fortunate enough to receive a photograph of their son’s grave.

When the war began, Elfrieda Recksiek was in the League of German Girls. “We mostly sang and had to march. We camped outside and cooked together. I had a lot of fun, and I think the other girls did too. We also had a uniform.” When she finished public school at age fourteen, she began her training as a nanny.

Heinz Recksiek had been drafted just weeks before Walter’s death and was in boot camp in Cologne to train as a combat engineer. “My parents visited me, and I wondered why they would come to visit me. Then I realized that they wanted to tell me in person [about Walter]. I admired and adored my older brother, and my parents knew that. He was a wonderful example of a member of the Church.”

Regarding his response to the draft notice, Heinz recalled, “The Church always told us that we should serve our country, so that is what I did. My father never agreed with that. At one point, he was close to being put into a concentration camp. He had made a remark about the government to somebody at his work. He had to talk his way out of it.”

During the year 1942, Werner Niebuhr was constantly in and out of combat. Although he was not trained as a medic, he often found himself caring for wounded comrades, and it was this kind of service that merited him the Iron Cross Second Class during one engagement. Under challenging conditions, he first developed diphtheria, then typhus, in consecutive months. These illnesses necessitated time away from the front, but this turned out to be a blessing. By the time he returned to his unit, 60 percent of the men had been killed or wounded—all of the men attached to the same mobile artillery piece. Because he continued to be ill, he was sent home for a longer leave. By March 1943, he was back in the Soviet Union. [11]

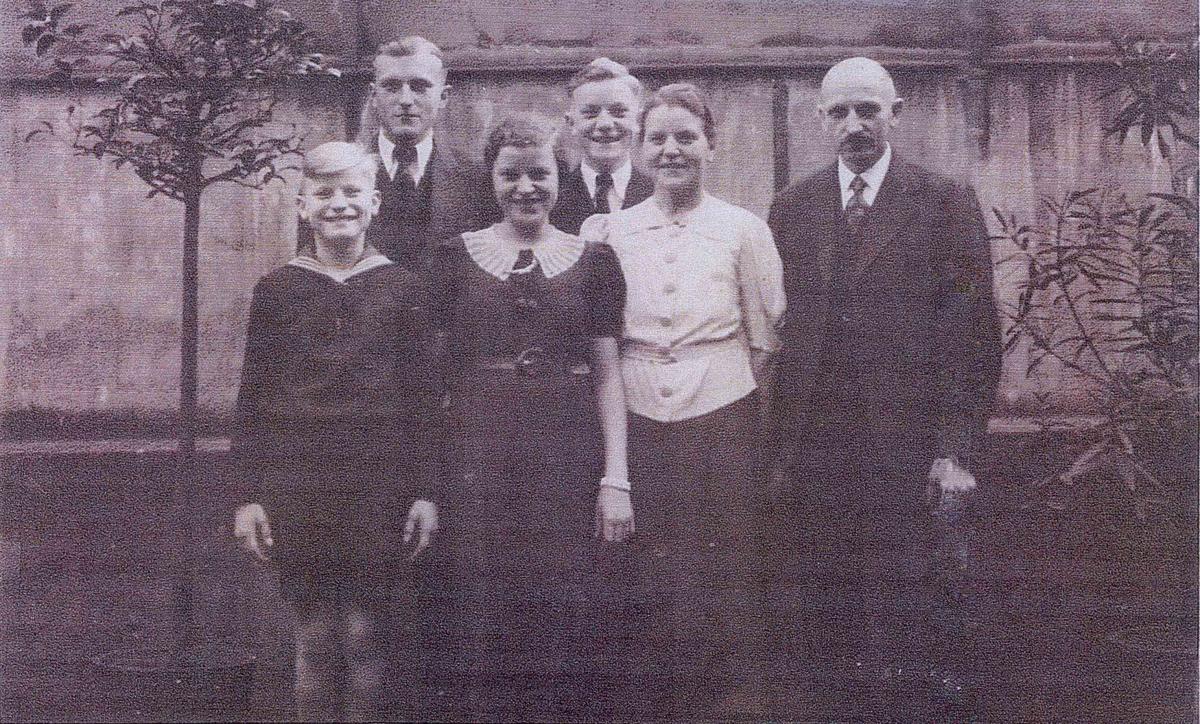

Fig. 4. Branch president Heinrich Recksiek with his family before the war. (H. Recksiek)

Fig. 4. Branch president Heinrich Recksiek with his family before the war. (H. Recksiek)

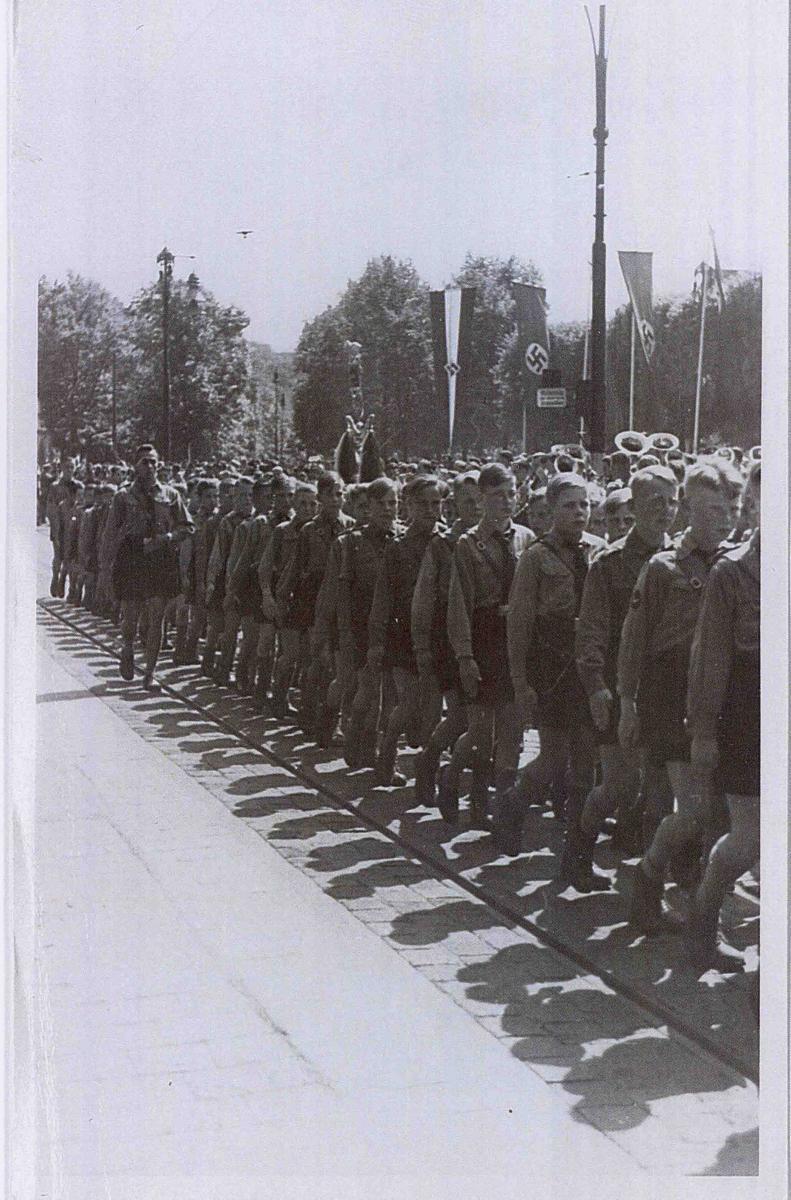

Fig. 5. Bielefeld Hitler Youth marching in a parade. (H. Recksiek)

Fig. 5. Bielefeld Hitler Youth marching in a parade. (H. Recksiek)

Fig. 6. This letter announced the death of Walter Recksiek in 1942. (H. Recksiek)

Fig. 6. This letter announced the death of Walter Recksiek in 1942. (H. Recksiek)

Fig. 7. The grave of Walter Recksiek (far left) in the Soviet Union. (H. Recksiek)

Fig. 7. The grave of Walter Recksiek (far left) in the Soviet Union. (H. Recksiek)

After eighteen months of training as a nanny, Elfriede Recksiek left Bielefeld to assist the family of Kurt Schneider. Brother Schneider was the president of the new Strasbourg District in southwest Germany, and Elfriede’s parents were pleased to have their daughter serve in the home of another LDS family. The Schneiders had one son and were expecting a second child. It was 1943, and Bielefeld was becoming a dangerous place to live.

Fig.8. Members of the Bielefeld Branch on an outing in the early war years. (E. Schmitz Michaelis)

Fig.8. Members of the Bielefeld Branch on an outing in the early war years. (E. Schmitz Michaelis)

In the Soviet Union in 1943, Werner Niebuhr was in perilous situations on several occasions. Once, he worked his way deep into and out of a minefield in order to retrieve the body of a fallen sergeant. On another occasion, he was running between foxholes when three shells landed within fifteen feet of him in quick succession. Each shell was a dud. He recalled, “Each one could have killed me if it had exploded. I cannot be thankful enough that our Father in Heaven saved me on different occasions.” [12]

Heinz Recksiek’s unit was stationed along the northern flank of the Eastern Front. As a member of the 16th Engineer Battalion, he was soon a corporal and was awarded the Iron Cross for heroism in battle. However, he came very close to being killed there in late 1943:

There was a grenade that you cannot hear until it is already going off. This one I did not see or hear, so it went off close to where I was standing. Just before it went off, I put my head down, and that was a good thing because I was wearing my helmet. The shrapnel would have hit me right in the chest and head. I was taken to the field hospital, and they operated right there. They found out that something had penetrated my lung. It was quite serious. A day later, they transported me by train to Finland. I stayed there over Christmas, but I was able to send a little note to my parents telling them that I was recuperating. Six weeks later, I was sent to the Harz mountain region [in Germany].

Werner Niebuhr was fortunate to be home for Christmas in 1943, when he saw his infant son, Roland, for the first time. Because he was an elder and had maintained the Church’s standards of worthiness, he was able to give a blessing to a Sister Wächter, who was expecting a child and had been told that there were serious complications. He promised her that all would be well, and so it was: the physician’s negative prediction was not fulfilled, and the baby was born entirely normal and healthy. [13]

Following the disastrous defeat at Stalingrad in February 1943, the German army began a slow and agonizing retreat westward toward Germany. Werner’s unit was shifted many times during the last two years of the war and eventually traveled south to Bucharest, Romania; west to Vienna, Austria; north to Prague, Czechoslovakia; and then northwest to Poland. From there, they went south again to Romania and west into Hungary. In action again, Werner pondered about how he “had been saved so many times where my life had been spared when it could have gone the other way. Every day my prayer was that my life would be saved that I could go home.” [14]

With time, the Allied air campaign against cities in western Germany intensified. The branch history provides this picture of meetings in 1943:

Only one meeting was being held each Sunday. We held Sunday school and sacrament meeting on alternate Sundays, always ending before 4:00 p.m. so that the members would have time to get home again before the anticipated air raid sirens sounded. In those days, we usually had thirty to forty people in attendance. [15]

Anna Carolina Schmitz instructed her children carefully about the sirens that announced impending danger. In the early years of the war, they simply went down into the basement when the sirens sounded, but on one occasion they had a very close call, according to Eleonore: “Next door to us in the same building was a lady, she was not LDS, but she was pregnant and had just had a baby. So my mother was helping her into the bomb shelter one day, and just as my mother got in, a bomb hit right outside in the street. The air pressure slammed the door into her back, but didn’t hurt her very much.” After that, Sister Schmitz took her children down the street to a bona fide bunker that was located very close to the rooms where they met for church. They were sitting inside that bunker one day when their apartment house was hit and burned to the ground.

By the summer of 1944, Heinz Recksiek had recovered from his wounds and was part of a reserve unit in western Germany. Again he had a close brush with death:

We were stationed right next to an Autobahn bridge. We saw the [Allied] planes flying over us right into the heart of Germany. I had a strange feeling and the air was literally vibrating. . . . We went down to seek shelter. . . . A door led to a room in which all of the cables of the bridge were anchored. We were just halfway down the stairway when we heard the bombs falling. Then I heard the voice people had been talking about in Church all the time. It pierced my soul and told me to go back upstairs. That is what I did. Back on top again, I crouched down on the ground and put my arms over my head. When it was over, I uncovered my face and saw that the bridge had ripped out all the cables that were anchored in that room down below. I would have been killed. My buddy had stayed in that chamber. When I looked around, I seemed to be the only man alive.

The Schneiders in Strasbourg had two sons. With the American Army approaching the city in the fall of 1944, Kurt Schneider took his family and their nanny, Elfriede Recksiek, east across the Rhine River to the town of Schönwald in Baden’s Black Forest. Elfriede was soon assigned by the government to work in a division of the steel factory where Brother Schneider was employed.

One day in 1944, Werner Niebuhr was shot in the leg and left by comrades during a hasty retreat before a Red Army attack on the Eastern Front. Werner tried to stop the bleeding and walk away from the fight but kept falling. Some resistance was overpowering him. While praying for help, he heard a voice as clear and loud as his own saying, “For you the war is over, and you never have to bear arms again; you will go home.” However, resistance was strong as he tried to drag himself away from the enemy. “I heard a voice saying, ‘You are a holder of the Melchizedek Priesthood; you can command Satan to leave.’ . . . So I commanded Satan to leave up from my body so I could go home and do the things my heart desired.” Werner made it back to his friends and was transported away from the fighting, but for several days there was no physician in the area to treat his wound. Several times, he loosened the tourniquet to allow some flow of blood into his leg, fearing that if he did not, his leg would have to be amputated. Eventually, he was treated and had some feeling in his leg, but he could not walk. One month later, he was in a hospital in St. Pölten, Austria, still unable to walk without support. [16]

With her home destroyed and her husband in Russia, Anna Carolina Schmitz moved into a small cabin in a refugee colony recently constructed in the Bielefeld suburb of Brackwede. As Eleonore recalled, they were nearly destitute: “We had a sofa that was being repaired. That was the only thing we saved because it was not in the apartment when the building burned. And we had two suitcases that my oldest sister had taken to the bomb shelter, and they contained my father’s clothing. Otherwise, we had nothing.” Sister Schmitz spent a great deal of time gathering food from local farmers and forests during the final months of the war, when the food distribution system that had worked so well began to break down. The older children were also constantly on the lookout for food from all possible sources. It was a time of survival that would only become more challenging when the war ended.

On September 30, 1944, Allied bombs totally destroyed the rooms in which the branch was holding meetings. Fortunately, much of the branch property was not destroyed, because it had been distributed among members for safekeeping. Beginning on October 15, 1944, meetings were held in the home of the Wächter family at Lange Strasse 47. [17]

By January 1945, Werner Niebuhr had recovered sufficiently to be sent home for a month. He arrived in January 1945 and found that Hilda and Roland were living out in the country with his aunt. Little Roland did not know his father and at one point asked him to leave. His furlough was doubled when he was surprised to receive a letter granting him another twenty-four days of leave due to bravery under fire. Therefore, he was in Bielefeld until March 1945, when, as he recalled, “practically no German soldier was home.” Upon leaving, he sensed his wife’s fears and promised her, “Nothing will have happened to me if you don’t get a letter [from me] in the next 3 months.” [18]

Werner’s odyssey took him from Bielefeld to Hannover to Vienna, where complications with his leg led him to another hospital. He was then sent west to Krems and Linz in Austria, where he was told simply to go home. Near Halberstadt in north-central Germany, he was captured by American soldiers. He was first put in a former concentration camp, then moved to Merseburg and Naumburg, where he was released and told to get to the British Occupation Zone in three days. He went to Sangerhausen, then Nordhausen, Hameln, and Bielefeld. He arrived there on Sunday, June 24, 1945—three months and two days after leaving his wife. “How great was our togetherness that I could be home again after this long and terrible time.” [19] The following Sunday, Werner joined the surviving members of the Bielefeld Branch meeting in the home of Sister Wächter. [20]

In early 1945, Elfriede Recksiek was allowed to leave the Schneider family and her employment in Schönwald and return to Bielefeld. She found that her home town had been extensively destroyed. The church rooms, too, had fallen victim to Allied bombs, and meetings were being held in the apartments of branch members. Her parents’ home had been destroyed, and they had moved in with Elfriede’s grandparents just outside of town. The Recksieks did not have a chance to participate in branch meetings again until after the war. For the remainder of the war, Elfriede worked in an office of the German army and lived in Bielefeld with the Schabberhardt family, who were members of the branch.

Heinz Recksiek’s unit retreated toward Bielefeld in the spring of 1945, and he was not far from his home town when the group decided to become civilians to avoid capture by the invaders. Up to that point, he had carried the holy scriptures with him, but this was not possible when he discarded his uniform. While he thought he could pass himself off as a civilian, he was undone by a photograph of his brother, Walter. The two boys looked so much alike that the British soldiers who caught up with Heinz on April 20, 1945, thought that he was the one in the photograph and treated him like a soldier. A few days later, he was turned over to the Americans, who put him in a POW camp in southern Germany. He was fortunate to be released just three months later.

On April 4, 1945, the American army entered Bielefeld, and the city surrendered without a fight. No meetings were held the next Sunday, but LDS services continued one week later with the permission of the military occupation authorities. Approximately thirty persons attended. [21]

Engelbert Schmitz had worked as a tailor in the employ of the city for the first few war years, but eventually the Wehrmacht came for him, and he spent the remainder of the war on the Eastern Front. He was wounded in the arm, and the bullet was never removed. But no real damage was done, and he finally came home to his family in the spring of 1945. Eleonore recalled how her father let his children feel the bullet in his arm. The Schmitz family had been isolated from the Saints in Bielefeld and did not establish contact again until they were given a small attic apartment in town in about December 1945. However, they were together again. Herr Schmitz had been given his former job with the city, and conditions slowly began to improve.

The city of Bielefeld had been attacked from the air twenty-three times; 40 percent of the city was destroyed, and at least 1,349 people had been killed. [22] Ten or more of those were Church members, and the branch history also lists ten soldiers who were killed or were missing in action by the end of the war. Several Saints died of other causes, and the Bielefeld Branch suffered more than any other branch in the West German Mission. Fortunately, those losses did not prevent the branch from prospering during the next few years as the city of Bielefeld gradually came back to life.

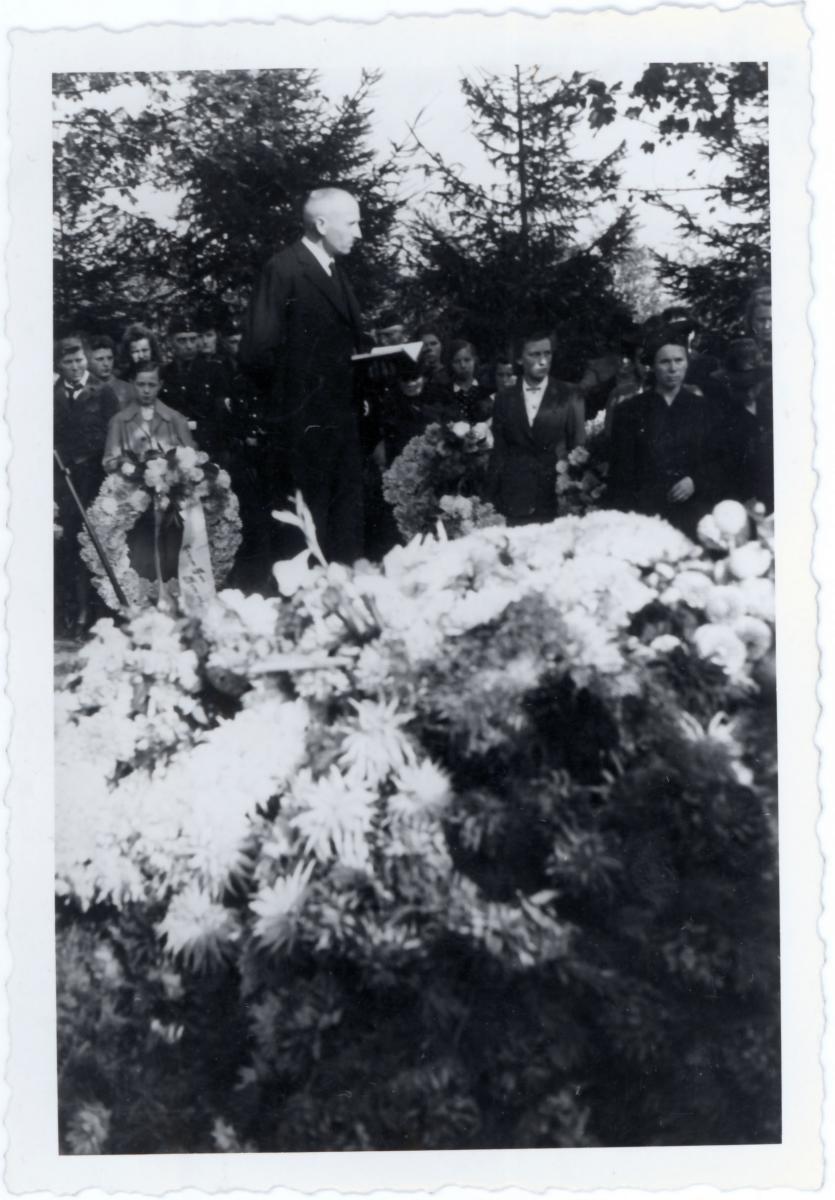

Fig. 9. Brother Recksiek conducted the funeral of Wilhelmine Bokermann who was killed in a streetcar accident in 1941. (E. Schmitz Michaelis)

Fig. 9. Brother Recksiek conducted the funeral of Wilhelmine Bokermann who was killed in a streetcar accident in 1941. (E. Schmitz Michaelis)

In Memoriam

The following members of the Bielefeld Branch did not survive World War II:

Ludwig August Karl von Behren b. Gellershagen, Bielefeld, Westfalen, 5 May or Jun 1911; son of August von Behren and Wilhelmine Marie Macke; bp. 19 Jun 1920; MIA near Moscow, Russia, 18 Dec 1941 (IGI; CR Bielefeld Branch)

Wilhelm Friedrich von Behren b. Gellershagen, Bielefeld, Westfalen, 5 Mar 1913; son of August von Behren and Wilhelmine Marie Macke; bp. 7 May 1923; conf. 7 May 1923; k. in battle Russia 3 Aug 1943 (CR Bielefeld Branch, FHL microfilm 68784, no. 189; IGI)

Henry Albert Bock b. London, England, 27 May 1911; son of Heinrich Friedrich Karl Martin Bock and Annie Jane Price; bp. 8 Aug 1924; conf. 8 Aug 1924; lance corporal; k. in battle Gorodischtsche, near Bolchow, Russia, 22 Feb 1943 (CR Bielefeld Branch, FHL microfilm 68784, no. 220; www.volksbund.de)

Hermann Karl Eberhard Bokermann b. Overberge, Hamm, Westfalen, 26 Mar 1920; son of Karl Wilhelm H. Bokermann and Marie Luise Grappendorf; bp. 8 Sep 1928; d. 5 Oct 1944 (IGI)

Fig. 10. Hermann Bokermann (middle) was killed in 1944. (E. Schmitz Michaelis)

Fig. 10. Hermann Bokermann (middle) was killed in 1944. (E. Schmitz Michaelis)

Wilhelmine Margarethe Johanna Bokermann b. Overberge, Hamm, Westfalen, 18 Oct 1924; dau. of Karl Wilhelm H. Bokermann and Marie Luise Grappendorf; bp. 17 Jun 1933; conf. 17 Jun 1933; k. streetcar accident 3 Oct 1941 (CR Bielefeld Branch, FHL microfilm 68784, no. 230; IGI)

Erich Ditt b. Bielefeld, Bielefeld, Westfalen, 21 Dec 1913; son of Heinrich Kraemer and Elisa Ditt; bp. 30 Nov 1930; conf. 30 Nov 1930; ord. deacon 6 Dec 1931; corporal; d. in military hospital 2/

Heinrich Friedrich Wilhelm Dröscher b. Heuerßen, Stadthagen, Schaumburg-Lippe, 10 Nov 1901; son of Johann Heinrich F. Dröscher and Engel Marie Karoline Heu; bp. 11 Aug 1928; conf. 11 Aug 1928; ord. deacon 24 Mar 1929; ord. teacher 9 Mar 1930; ord. priest 7 Sep 1930; m. Heuerβen 20 Jun 1925, Engel Marie Sophie Karoline Kirchhöfer; k. air raid Bielefeld, Bielefeld, Westfalen, 30 Sep 1944 (CR Bielefeld Branch, FHL microfilm 68784, no. 84; IGI)

Margarethe Charlotte Galts b. Wittmund, Ostfriesland, Hanover, 22 Mar 1867; dau. of Bernhard Galts and Elisabeth Margarethe Ihnen; bp. 7 May 1923; conf. 7 May 1923; m. 16 Apr 1898, Wilhelm Meier; k. air raid Bielefeld, Bielefeld, Westfalen, 30 Sep 1944 (CR Bielefeld Branch, FHL microfilm 68784, no. 157; CHL microfilm 2458, 346–47)

Engel Marie Karoline Sophie Kirchhöfer b. Reinsen-Remeringhausen, Stadthagen, Schaumburg-Lippe, 23 Mar 1903; dau. of Friedrich Johann Wilhelm Ludwig Kirchhöfer and Engel Marie Sophie Oltrogge; bp. 11 Aug 1928; conf. 11 Aug 1928; m. Heuerßen, Stadthagen, Schaumburg-Lippe, 20 Jun 1925, Heinrich Friedrich Wilhelm Dröscher; k. air raid Bielefeld 30 Sep 1944 (CR Bielefeld Branch, FHL microfilm 68784, no. 85)

Erhardt Kirchhoff b. Bielefeld, Bielefeld, Westfalen, 15 Aug 1924; son of Wilhelm Kirchhoff and Anna Luise Tosberg; bp. 27 Aug 1932 (CR Bielefeld Branch; IGI)

Lina Luise Christine Marowsky b. Todtenhausen, Minden, Westfalen, 13 Dec 1877; dau. of Christian Marowsky and Lina Mearhoff; bp. 7 Nov 1910; conf. 7 Nov 1910; m. 9 Dec 1911, Karl Bockermann; d. cardiac insufficiency 11 Jul 1941 (CR Bielefeld Branch, FHL microfilm 68784, no. 142)

Franziska Emma Kätchen Mothes b. Hamburg 12 Jun 1880; dau. of Edward Mothes and Marie Johanna M. Friedrichsen; bp. 7 Sep 1928; conf. 7 Sep 1928; d. 13 Jun 1943 (CR Bielefeld Branch, FHL microfilm 68784, no. 98)

Friedrich Heinrich Walter Recksiek b. Schildesche, Bielefeld, Westfalen, 28 Aug 1919; son of Karl Heinrich Recksiek and Anna Katharine Johanna Milsmann; bp. 17 Dec 1927; conf. 20 Dec 1927; ord. deacon 6 Dec 1931; ord. teacher 10 Jan 1928; ord. priest 2 Apr 1939; corporal; k. in battle Nishni-Kurp, Kaukasus, Russia, 26 Sep 1942 (CR Bielefeld Branch, FHL microfilm 68784, no. 207; FHL microfilm no. 271400, 1925 and 1935 censuses; IGI, AF, PRF; www.volksbund.de)

Fig. 11. Walter Recksiek. (H. Recksiek)

Fig. 11. Walter Recksiek. (H. Recksiek)

Marie Katharine Reick b. Warburg, Paderborn, Westfalen, 12 Jun 1903; dau. of Wilhelm Reick and Helene Schmidt; bp. 16 Jan 1926; conf. 17 Jan 1926; m. 14 Apr 1925, Alfred Passon (div.); d. surgery 9 Jan 1940 (CR Bielefeld Branch, FHL microfilm 68784, no. 232)

Johann Friedrich Heinz Schroeder b. Bielefeld 12 May 1919; son of —— Schroeder and Anna Wegener; k. in battle 1943 (Chronik der Gemeinde Bielefeld, FHL microfilm 245258, 1930 and 1935 censuses)

Pauline Simon b. Orchowo, Mogilno, Posen, 25 Jan 1903; dau. of Phillip Simon and Katharine Gruber; bp. 21 Oct 1923; conf. 21 Oct 1923; m. Wilhelm Uibel; d. lung ailment 17 Sep 1944 (CR Bielefeld Branch, FHL microfilm 68784, no. 182)

Hellmut Heinz Steinkühler b. Theesen, Bielefeld, Westfalen, 14 Aug 1927; son of Gustav Adolf Steinkühler and Karoline Sophie Auguste Obermeier; bp. 26 Oct 1935; conf. 27 Oct 1935; ord. deacon 3 May 1942; d. battlefield wounds 6 Apr 1945 (CR Bielefeld Branch, FHL microfilm 68784, no. 252; IGI)

Nephi Uibel b. Bielefeld, Bielefeld, Westfalen, 28 Jul 1925; son of Wilhelm Uibel and Pauline Simon; bp. 19 Aug 1933; conf. 19 Aug 1933; ord. deacon 2 Apr 1939; sapper; k. in battle Normandy, France, 10 Aug 1944; bur. La Cambe, France (CR Bielefeld Branch, FHL microfilm 68784, no. 238; www.volksbund.de)

Karoline Friederike Weber b. Münchehagen, Stolzenau, Hanover, 7 Mar 1884; dau. of Friedrich Weber and Karoline Rode; bp. 2 Aug 1929; conf. 2 Aug 1929; m. —— Koppelmeyer; d. Russia 2 Feb 1942 (CR Bielefeld Branch, FHL microfilm 68784, no. 277)

Friedrich Wind b. Detmold, Lippe, 2 Jun 1864; son of Heinrich Wind and Louise Nolte; bp. 26 Oct 1910; conf. 26 Oct 1910; ord. deacon 21 Jun 1914; ord. elder 16 Sep 1914; m. Minna Luise Wind (div.); d. senility 7 Mar 1941 (CR Bielefeld Branch, FHL microfilm 68784, no. 194)

Notes

[1] Bielefeld city archive.

[2] Chronik der Gemeinde Bielefeld, 1896–1996 (Bielefeld, Germany: Bielefeld LDS Ward, 1996), 132. This source lists Brother Recksiek as the branch president as of September 14, 1938, the date on which the American missionaries were evacuated from Germany the first time. However, the directory of the West German Mission shows Elder Dean Griner of the United States in that leadership position as late as July 20, 1939. Whichever record is correct, it is certain that Heinrich Recksiek was the branch president after Elder Griner left Germany on August 25, 1939.

[3] Heinz Recksiek, interview by Marion Wolfert in German, Salt Lake City, March 22, 2006; summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[4] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” 257, CHL CR 4 12.

[5] Elfriede Recksiek Doermann, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, May 4, 2009.

[6] West German Mission manuscript history, CHL MS 10045 2.

[7] Eleonore Schmitz Michaelis, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, February 6, 2009.

[8] Chronik der Gemeinde Bielefeld, 49.

[9] Werner Niebuhr, autobiography, 1985, CHL MS 19617, 19.

[10] Niebuhr, autobiography, 22.

[11] Niebuhr, autobiography, 26–27.

[12] Niebuhr, autobiography, 31.

[13] Niebuhr, autobiography, 35.

[14] Niebuhr, autobiography, 44–45.

[15] Chronik der Gemeinde Bielefeld, 50.

[16] Niebuhr, autobiography, 46–49.

[17] Chronik der Gemeinde Bielefeld, 50.

[18] Niebuhr, autobiography, 53–54.

[19] Niebuhr, autobiography, 54–62.

[20] Niebuhr, autobiography, 62.

[21] Chronik der Gemeinde Bielefeld, 51.

[22] Bielefeld City Archive.