Preserving or Erasing Jesus's Humanity: Tensions in 1-2 John, Early Christian Writings, and Visual Art

Mark D. Ellison

Mark D. Ellison, "Preserving or Erasing Jesus's Humanity: Tensions in 1-2 John, Early Christian Writings, and Visual Art" in Thou Art the Christ: The Son of the Living God, The Person and Work of Jesus in the New Testament, ed. Eric D. Huntsman, Lincoln H. Blumell, and Tyler J. Griffin (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), 260–282.

Mark D. Ellison was an associate professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University when this was written.

How do we picture Jesus? To what extent does our belief in Christ’s divinity and postresurrection glory influence the way we envision the humanity of Jesus during his mortal ministry? Creators of early Christian literature and visual art grappled with tensions between a desire to affirm Jesus’s full humanity and an impulse to minimize or erase it in order to emphasize his divinity. For ancient believers who sought to preserve the teaching that Jesus was both divine and fully human, what was in jeopardy was salvation itself—the whole notion of what it meant that Christ came to earth, was born with a physical body, lived a mortal life, suffered death, and rose again. To deny Jesus’s full humanity was to deny that he fully redeemed humanity. New Testament texts and early Christian writings reveal a sustained effort to preserve the doctrine of Jesus’s full humanity in the face of counterefforts. This fundamental tension affected the earliest visual portrayals of the crucifixion in narrative art. It is a history that provides a basis for us, as Latter-day Saint followers of Christ, to think about what is at stake in preserving, minimizing, or erasing Jesus’s humanity in our own reading of the Gospels or engagement with visual portrayals of Jesus.

Jesus’s Humanity in 1–2 John

In the New Testament, no writing emphasizes Jesus’s humanity and its importance in Christian belief to a greater degree than 1–2 John.[1] These texts were written in the late first century, probably at a time of crisis when a group in the church (likely in Asia Minor) had broken off from the rest of the Christian community (1 John 2:18–19, “they went out from us”). One of the defining beliefs of this schismatic group was its denial that Jesus Christ had “come in the flesh”:

For many deceivers are entered into the world, who confess not that Jesus Christ is come in the flesh. This [i.e., any such person] is a deceiver and an antichrist. (2 John 1:7)

Many false prophets are gone out into the world. Hereby know ye the Spirit of God: Every spirit that confesseth that Jesus Christ is come in the flesh is of God: And every spirit that confesseth not that Jesus Christ is come in the flesh is not of God. (1 John 4:1–3)

The schism’s refusal to confess that Jesus had come in the flesh suggests that it was an early form of a heresy known in other early Christian writings as docetism.[2] In the second and early third centuries of Christianity, docetists of various kinds held that deity was incompatible with such human limitations as a material body, limited knowledge, infirmity, and pain. Believing that God was unchangingly immaterial, all-knowing, all-powerful, and impassible (incapable of suffering pain), docetists concluded that if Jesus was the divine Son of God, he could not truly have inhabited a physical body, experienced mortal conditions, or endured suffering, but only seemed to—the word docetism comes from the Greek dokeō, “to seem” or “to appear.” (For further discussion of this subject, see the chapter by Jason Combs in this volume.)

In apparent response to such claims by the late first-century dissenters, 1 John begins with emphatic testimony that Jesus was no mere apparition, but really lived with a physical body: “[We declare to you] That which was from the beginning, which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we have looked upon, and our hands have handled, [concerning] the Word of life” (1 John 1:1; emphasis added). This echoes the testimony in the prologue of the Gospel of John: “And the Word was made flesh, and dwelt among us” (John 1:14). In its affirmation of a flesh-and-blood Jesus, 1 John gives particular emphasis to the blood of Jesus Christ: Jesus “came by water and blood . . . not by water only, but by water and blood” (1 John 5:6). Scholars debate the exact meaning of this statement but generally agree that it refers to Jesus’s humanity (compare John 19:34).[3] The blood of Christ is crucial to redemption: “The blood of Jesus Christ . . . cleanseth us from all sin” (1 John 1:7).

Yet the dissenters appear to have believed that they were without sin, to judge from insistent counterstatements in 1 John: “If we say that we have no sin, we deceive ourselves, and the truth is not in us. . . . If we say that we have not sinned, we make him a liar, and his word is not in us” (1 John 1:8, 10).[4] Believing they were sinless, the dissenters “felt no need of atonement and cleansing by the blood of Jesus” and evidently did not think Jesus’s suffering and bodily death had any salvific meaning.[5] Against this, 1 John insists that Jesus is “the atoning sacrifice [KJV ‘propitiation’] for our sins” (1 John 2:2 New Revised Standard Version; 4:10).

Some later docetists made a distinction between the divine “Christ” and the human “Jesus”; Christ descended on Jesus at his baptism, but departed before the crucifixion and thus did not suffer.[6] Evidently in response to ideas like this, 1 John refers to liars who deny “that Jesus is the Christ,” and defines faithful believers as those who believe “that Jesus is the Christ” and love both God and God’s begotten Son Jesus (1 John 2:22; 5:1).

Preserving or Erasing Jesus’s Humanity in Other Early Christian Writings

Johannine scholar Robert Kysar observes that the great theological contribution made by 1–2 John lies not just in how these books affirm Jesus’s humanity, but also in how they make this affirmation the center of Christian faith, an essential element in “the doctrine [didachē] of Christ” (2 John 1:9–10).[7] Indeed, in following decades, other Christian writers adopted this doctrinal position as they argued against docetic teachings along much the same lines as 1–2 John. Early in the second century, for example, Polycarp (AD 69–155), the bishop of Smyrna, wrote to the saints at Philippi, “Everyone who does not confess that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh is antichrist; and whoever does not acknowledge the testimony of the cross is of the devil.”[8] Like John, Polycarp saw an essential connection between Jesus’s humanity (his coming in the flesh) and redemption of humanity (via the crucifixion).

Even more emphatically, Polycarp’s friend Ignatius (c. AD 35–107), bishop of Antioch, addressed the same concerns in seven letters he wrote to churches in Asia Minor while soldiers were taking him through that region en route to his martyrdom in Rome. Throughout his letters Ignatius expresses concerns about divisions, schisms, and false teachings, particularly docetic teachings. Against these, he repeatedly asserts the reality of Jesus’s human experiences, including the Savior’s bodily suffering and salvific death:

He is truly of the family of David with respect to human descent, Son of God with respect to the divine will and power, truly born of a virgin, . . . truly nailed in the flesh for us under Pontius Pilate and Herod the tetrarch (from its fruit we derive our existence, that is, from his divinely blessed suffering). . . . For he suffered all these things for our sakes, in order that we might be saved; and he truly suffered just as he truly raised himself—not, as certain unbelievers say, that he suffered only in appearance [dokein]. . . . Avoid such people. . . . Do pay attention, however, to the prophets and especially to the gospel, in which the passion [pathos, the suffering of Christ] has been made clear to us and the resurrection has been accomplished.[9]

Some noncanonical early Christian texts provide a glimpse into views like those that 1–2 John, Polycarp, and Ignatius opposed. The second-century Gospel of Peter contains a passage that depicts Christ suffering no pain during the crucifixion: “And they brought two malefactors, and they crucified the Lord between them. But he held his peace, as though having no pain.”[10] The Acts of John, written in the second or third century, relates gnostic Christian legends about the apostle John, and portrays Christ in docetic terms. The character “John” in this text states that when he would lay hold on Jesus he would only sometimes feel a material body; at other times he would feel nothing, suggesting Jesus was actually immaterial. When John sees in vision the crucifixion, he sees the Lord in the air above the cross, and the Lord tells him that he is not actually suffering what people would say he suffered in the crucifixion, for he is “God unchangeable, God invincible.”[11] Similarly, in the late second/

In the third and fourth centuries, some Christian teachers continued to oppose docetic and docetic-like teachings in the tradition of 1–2 John, Polycarp, and Ignatius, insisting that the full humanity of Jesus was essential to humanity’s redemption. For example, Origen (c. AD 185–254) wrote: “Our Savior and Lord, in his desire to save the human race as he willed to save it, for this reason thus willed to save the body, just as he willed likewise to save also the soul, and willed also to save the rest of the human being: the spirit. For the whole human being would not have been saved if he had not assumed the whole human being. They eliminate the salvation of the human body by saying that the body of the Savior is spiritual” (emphasis added).[13] In the Trinitarian debates of the fourth century, Gregory of Nazianzus (c. AD 329–390) adopted Origen’s reasoning as he opposed the teachings of Apollinarius of Laodicea (died c. AD 390–392), a heretical bishop who had denied Jesus’s full humanity; Gregory famously wrote, “That which Christ has not assumed He has not healed.”[14]

Athanasius (c. AD 296–373) also connected Christ’s incarnation to salvation, even to human deification: “He was incarnate that we might be made God.”[15] However, Athanasius seems to have felt conflicted about affirming the full humanity of Jesus Christ. On one hand, he wrote that Christ took a body like ours, that he died to undo “the law concerning corruption in human beings,” that he “became human, . . . possessing a real and not an illusory body,” and that “at his death . . . Christ suffered in the body.”[16] On the other hand, Athanasius described the incarnation in ways that veered toward formulations used earlier by docetic teachers: Christ’s body “was a human body,” but “by the coming of the Word into it, it was no longer corruptible,” and “became immune from corruption”; “He himself was harmed in no way, being impassible and incorruptible and the very Word and God.”[17] As Lincoln Blumell has put it, Athanasius taught an incarnation without condescension.[18]

Athanasius’s view of Jesus’s qualified humanity prevailed among many Christians. Though the emerging orthodoxy largely rejected the teachings of gnostic Christian groups, elements of docetic thinking left a mark on how believers conceptualized Jesus’s humanity and divinity. The creed from the Council of Nicaea (AD 325) that Athanasius championed made use of terminology used earlier by docetists when it rejected any who asserted that the Son of God was subject “to alteration or change” (hē trepton hē alloiōton). This echoed the depiction of Christ in the Acts of John as “God unchangeable” (ametatrepton), a conception associated with a God invulnerable and impassible.[19] Fourth-century Trinitarian formulations led to fifth-century christological debates over whether the human and divine in Jesus Christ constituted two “persons” or two “natures,” or ought to be understood as one undivided nature that was uniquely human and divine. Believers on various sides of the issues felt that they stood to lose either the divinity of Christ or the redemption of humanity in the formulated definitions. It was in this setting that someone produced the earliest surviving artistic portrayal of the crucifixion in a narrative setting.

Jesus’s Ambiguous Humanity in the Earliest Depictions of the Crucifixion

Around the years AD 420–430, a skilled artist, perhaps in Rome, carefully carved reliefs on several small ivory panels, producing decorated sides of a box that was probably used to hold a sacred relic or consecrated eucharistic (sacrament) bread. The box’s four surviving panels, now called the Maskell Ivories and held in the British Museum, depict scenes from the New Testament passion narratives: Christ carrying his cross, the crucifixion, the empty tomb, and the risen Christ appearing to his disciples. The second panel is the earliest portrayal of the crucifixion in narrative art (fig. 1).[20]

The scene depicts Christ on the cross, with Mary and John approaching sorrowfully from the left (see John 19:26–27), as a soldier to the right pierces Christ’s side with a spear (now missing, though the wound in Christ’s side is visible; see John 19:34). Nails are visible in Christ’s hands, but his feet appear to be unsupported. A halo encircles his head beneath a plaque inscribed in Latin, REX IVD [AEORUM], “King of the Jews.” Christ’s eyes are open, looking straight ahead—he is shown alive and alert. His head is held upright. His arms and body do not sag from the nails; they conform to the T-shape of the cross, “as though standing defiantly” against it.[21] He is a picture of strength, boldness, and triumph and seems “unaffected by the process of his crucifixion.”[22] He contrasts sharply with the figure of Judas at the far left. Judas hangs from a leafy tree suspended by a rope around his neck, his head tilted back, his eyes shut, his arms hanging limp at his sides. A bag of coins lies fallen on the ground beneath his feet, open and spilling its contents; the drawstring of the pouch looks almost like a snake crawling toward the tree (see Matthew 27:3–5; Genesis 3:1–15).[23] Viewers may have noticed “the irony of Judas hanging dead on a living tree while the living Christ hanging on a ‘dead tree’ triumphs over death.”[24]

Ivory panel with relief of the crucifixion, 7.5 x 9.8 cm, c. AD 420–430. The British Museum, London. Photo © The trustees of the British Museum, London / Art Resource.Art historian

Ivory panel with relief of the crucifixion, 7.5 x 9.8 cm, c. AD 420–430. The British Museum, London. Photo © The trustees of the British Museum, London / Art Resource.Art historian

Felicity Harley-McGowan reads the scene and its accompanying panels as an emphasis of “Jesus’s triumph over death” and “the subsequent triumph of the Church.” The two images of death—“the suicide of Judas and the crucifixion of Jesus—are pivotal” in the articulation of this theme.[25] But we may note that the image articulates this theme by employing a traditionally docetic motif—that of an impassible Christ who was invulnerable to pain and suffering.A few years after this ivory panel was created, another workshop artist in Rome carved a different crucifixion scene on one of 28 wood panels for the doors of the basilica of Santa Sabina. The panel is the earliest surviving image of the crucifixion made for public display (fig. 2).[26] It and the accompanying panels depict various scenes from Christ’s life and other biblical narratives. On the crucifixion panel, Christ and the two thieves stand with their arms outstretched against a stone, gabled cityscape (perhaps representing Jerusalem’s walls). The figure of Christ is nearly twice as large as the thieves to either side. Only parts of their crosses are visible. All three figures are shown with their eyes open, and rather than hanging from their nailed hands, they are posed as if in the ancient posture of prayer, with upraised hands (see 1 Kings 8:22; Psalm 28:2; 1 Timothy 2:8).[27] “None of the figures is visibly suffering,” observes historian Robin Margaret Jensen.[28]

Wooden panel with carved crucifixion scene, Sta. Sabina, Rome, c. AD 432–440. Photo: Art Resource.

Wooden panel with carved crucifixion scene, Sta. Sabina, Rome, c. AD 432–440. Photo: Art Resource.

We should be cautious in assessing the Christology that might be implied in these early images of the crucifixion. There were likely multiple factors that motivated the depiction of a seemingly impassible Christ, including the desire already noted to emphasize resurrection and triumph over death, the inclination to shy away from what is an inherently painful subject for people who love and revere Christ, and the scandal of the crucifixion in the early church (see 1 Corinthians 1:23).[29] Eventually Christian artists explored others ways of depicting the crucifixion in order to highlight Jesus’s humanity and convey the pathos of that event.[30] Perhaps the most we can say is that in these early attempts to picture Christ’s redemptive death, we see a tendency to avoid depicting his suffering and recognize that this tendency had a long history in Christian conversations about Christ’s divinity and his humanity.

Latter-day Saint Reflections

For Latter-day Saints, reflecting on this history is valuable in several respects. For one, it enhances our appreciation of the theological contribution made by key Restoration scriptures. In the Book of Mormon, Nephi’s vision describes Christ’s birth, mortal ministry, and crucifixion for the sins of the world as manifestations of “the condescension of God” (1 Nephi 11:12–18, 26–33; cf. 2 Nephi 4:26; 9:53; Jacob 4:7). Since Christ “descended below all things,” he “comprehended all things, that he might be in all and through all things” (D&C 88:6; compare 122:8). Other important passages describe Jesus’s bodily and spiritual suffering as well as the divine empathy and healing resulting from it. Jacob taught that Christ would come into the world to suffer “the pains of every living creature, both men, women, and children” (2 Nephi 9:21). In King Benjamin’s words, Christ would “suffer temptations, and pain of body, hunger, thirst, and fatigue,” such that “blood cometh from every pore, so great shall be his anguish” (Mosiah 3:7). In the Doctrine and Covenants, Christ states that his suffering caused him, “even God, the greatest of all, to tremble because of pain, and to bleed at every pore, and to suffer both body and spirit” (D&C 19:18). Alma taught that Christ would “go forth, suffering pains and afflictions and temptations of every kind,” enduring “the pains and the sicknesses of his people,” and then death itself; as a result, Christ would “loose the bands of death,” “be filled with mercy,” and would “know according to the flesh how to succor his people according to their infirmities” (Alma 7:11–12; emphasis added).

These and other passages of Restoration scripture affirm that Jesus, as divine Son, had a fully human experience—he endured real temptations to which he could have succumbed; he was not “unchanging” in the sense of being invulnerable to temptation or pain; he experienced infirmity; and he suffered pain in body and spirit.[31] In these respects latter-day scripture connects us with the early Christian teachings of 1–2 John, Polycarp, Ignatius, Origen, and Gregory of Nazianzus: because Christ fully assumed humanity, he can fully heal humanity.

This history also beckons us to ask ourselves how fully we perceive the humanity of Jesus in our reading of the Gospels or in portrayals of Jesus in art and film. We do not often pause to think critically about images of Jesus, whether they be painted on canvas, chiseled in stone, projected on a screen, or constructed in our own minds. Yet in our increasingly visual culture, thoughtful discipleship and scriptural literacy increasingly require visual literacy.[32]

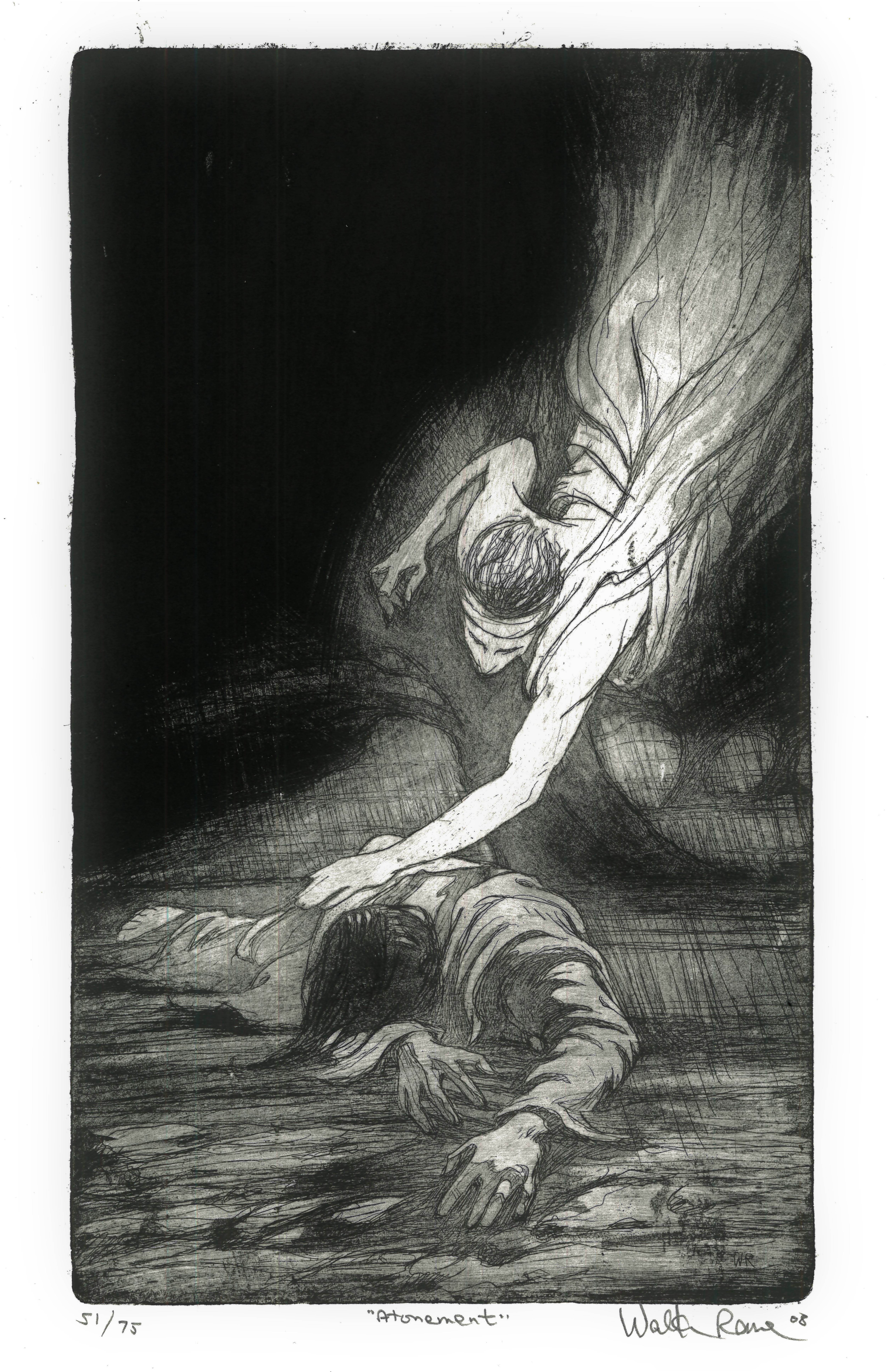

Walter Rane, Atonement, etching. © Walter Rane, used by permission.

Walter Rane, Atonement, etching. © Walter Rane, used by permission.

Artistic portrayals of Christ are not necessarily attempts to represent his likeness—what he really looked like historically—nor do artists necessarily intend to take a conscious stance on fine points of Christology. Nevertheless, images of Christ can influence the way we understand him, so thoughtful viewers should engage those images critically. For example, as Richard Holzapfel has suggested, we might ask ourselves whether a depiction of the Savior represents the mortal Christ or the risen Christ, or perhaps blends the two.[33] Faced with a work of art that retrojects elements of postresurrection glory and perfection onto Jesus in a scene from his mortal life, viewers might recognize a theological statement rather than a historical claim and may ask themselves what limits they should place upon that image as they read the New Testament and construct their own understanding.

Often portrayals of the Savior are made with an understandable reverence dictating that Christ must be depicted with dignity, that the image must transcend the confines of realism and historicity and point to some eternal truth.[34] Yet this aspiration exists in tension with the claim that Christ condescended, lived in a flesh-and-blood body, suffered, and died—and that these factors are central to the whole message of his redemption. Artists wrestle with this tension. For example, LDS artist James C. Christensen described the difficulties he faced as he painted a depiction of Christ suffering in Gethsemane:

Typical paintings of the Atonement look too serene, too much like evening prayer. They are very unsatisfactory to me. . . . I considered painting the Savior in the most extreme agony. Collapsed, face down, hands in the dirt. Were he to lift up his head, his face would be covered with dust and sweat. But I have not painted that image because he is still our God. It would be unseemly to depict him in an undignified way—even if that image might be historically or pictorially accurate.[35]

LDS artist Walter Rane has taken steps that Christensen did not in several pieces portraying Christ’s suffering in Gethsemane. In his etching Atonement (fig. 3), Rane opted not to show Christ’s face at all, instead depicting literally the detail found in Matthew that when Jesus prayed in Gethsemane he “fell on his face” (Matthew 26:39) and combining it with the description in Luke: “And there appeared an angel unto him from heaven, strengthening him. And being in an agony he prayed more earnestly” (Luke 22:43–44). This compositional choice makes “the image about the event and not about what [Jesus] looks like,”[36] but more than that, it enables Rane to depict Jesus in an agony far more dramatic and severe than we see in many Gethsemane paintings. Here Christ’s suffering is so enormous that he does not kneel in evening prayer; he cannot remain upright at all. He lies prostrate upon the ground, his face in the dirt, his hands grasping the earth desperately. Nothing stands between Christ and the world that is crushing him, the world that he is saving. The image makes a “forthright presentation of a heartbreakingly vulnerable Redeemer, something that is almost painful to look upon.”[37]

By contrast, some popular depictions of the Savior place him in exquisitely pretty settings, using fine detail and vivid colors. We may appreciate in them intentions to highlight Christ’s perfection, perhaps to convey something of the ecstasy of spiritual experience, the breathless beauty of moments when we encounter Christ’s transforming love. Yet not all viewers may see this. One observer remarked to me that one such painting “looks almost airbrushed, sort of fake.” As LDS art historian Richard Oman stated, “Sometimes less detail is more spiritual power. . . . If artists focus only on bright, cheerful, well-lit, tightly detailed images of Christ, they may trivialize to an extent the richness and depth of the spiritual experiences that the Savior had in mortality and that we can have, in turn, with him. Great religious art does not always bring a sense of peace. Sometimes it causes us to be uncomfortable.”[38]

One viewer, evaluating a highly idealized, vividly colored Gethsemane scene, noted some of its qualities she genuinely appreciated, but then told me it felt manipulative to her: “I feel like it’s telling me that I’m supposed to feel sad.” Another observer said she felt like the painting trivialized Jesus’s suffering. Pointing to the expression of mild concern on Jesus’s face, she remarked, “I feel like that when I lose my car keys.” Then, pointing to Walter Rane’s Atonement, she added, “But there have been a few times in my life when I have felt something like that. And it is meaningful to me that the artist has depicted Jesus as one who has felt what I have felt in my most wretched moments.”

Do some modern portrayals of Jesus unknowingly embrace a kind of docetism? If a video of Jesus at a wedding feast depicts him sitting somber and detached, unmoved by the festivities, what is that implying about Christ? Was he, is he, really too dignified to smile, laugh, or enjoy people? That contradicts the New Testament witness that one of the main criticisms Jesus faced was that he was too jovial, too ready to eat and drink, even with those of questionable company.[39] If a film of the crucifixion never portrays Jesus crying out in a loud voice, as he is described as doing in each of the Synoptic Gospels,[40] is reverence rewriting the narrative? What is art suggesting if it portrays a mortal Jesus who does not seem to experience the range of mortal experiences that you and I do, one who neither laughs nor cries out in agony?[41]

Just as salvation was at issue for ancient Christians as they wrote and preserved affirmations of Jesus’s full humanity, there may be real, saving significance for viewers of Christian art when they see Jesus portrayed as human, relatable, laughing, crying, feeling pain, feeling joy, rather than continually detached and aloof. There may be hunger for art that conveys the message of Christ’s condescension—that he came here and met us where we are, in order to lift us up to where he is. An other-worldly Jesus may give the impression that God is impossibly distant, that we in our human state are hopelessly estranged from him, that the burden rests solely upon us, somehow, to climb to him. But that is not the gospel.

It does not follow that in order to portray Christ’s humanity artists must seek out extreme depictions of his suffering, nor is there necessarily any single, preferable approach to portraying the Savior. However, part of our aspiration to be thoughtful followers of Christ is the effort to be aware of how we are visualizing Jesus, informed by scripture, by history, and by an appreciation of the many styles of visual media and the ways they can function. Salvation is at stake, or at least our effectiveness in understanding it and teaching it is, in our choices here. For us, as for our ancient Christian forebears, minimizing Jesus’s humanity compromises the reach of his redemption.

Notes

[1] Robert Kysar, “John, Epistles of,” in The Anchor Bible Dictionary, ed. David Noel Freedman (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 3:909.

[2] So named, for example, in Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 6.12.1–16; for a dissenting opinion, see Urban von Wahlde, Gnosticism, Docetism, and the Judaisms of the First Century: The Search for the Wider Context of the Johannine Literature and Why It Matters (London: T&T Clark, 2015).

[3] Kysar, “John,” 909.

[4] For information on use of the contextual method to read 1–2 John (inferring the other side of the “conversation”), see Bart D. Ehrman, The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings, 6th ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 198–205.

[5] I. Howard Marshall, The Epistles of John, The New International Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1978), 15.

[6] Irenaeus (c. AD 180) wrote that the late first-century/

[7] Kysar, “John,” 909.

[8] Polycarp, Epistle to the Philippians 7.1, trans. Michael W. Holmes, The Apostolic Fathers: Greek Texts and English Translations, 3rd ed. (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2007), 289.

[9] Ignatius, Epistle to the Smyrnaeans 1.1–2; 2; 3.1; 7.2, trans. Holmes, Apostolic Fathers, 249, 251 [altered “in appearance only” to “only in appearance”], 255. See also Ignatius, Epistle to the Trallians 8.1; 9.1–2; 10; Ignatius, Epistle to the Ephesians 7.2; Ignatius, Epistle to the Romans 6.3; Ignatius, Epistle to the Magnesians 11; Ignatius, Epistle to Polycarp 3.2.

[10] Gospel of Peter 4, trans. J. Armitage Robinson, Ante-Nicene Fathers (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature, 1896), 10:7. Eusebius wrote that this gospel was regarded as heretical, and came from people he and his fellow Christians called “Docetae,” docetists; see Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 6.12.1–16.

[11] Acts of John 93, 97–104, trans. M. R. James, The Apocryphal New Testament (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1924), 256; according to Eusebius, orthodox believers regarded Acts of John as heretical: see Ecclesiastical History 3.25.6.

[12] Gerard P. Luttikhuizen, “The Suffering Jesus and the Invulnerable Christ in the Gnostic Apocalypse of Peter,” in The Apocalypse of Peter, ed. Jan N. Bremmer and István Czachesz (Leuven, Belgium: Peeters, 2003), 187–99.

[13] Origen, Dialogue with Heraclides 7.1–9; emphasis added; trans. Robert J. Daly, Origen, Treatise on the Passover and Dialogue of Origen with Heraclides and His Fellow Bishops on the Father, the Son, and the Soul, Ancient Christian Writers 54 (New York: Paulist Press, 1992), 62–63.

[14] Gregory of Nazianzus, Epistle 101.32; trans. Charles Gordon Browne and James Edward Swallow, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, 2nd series, vol. 7, ed. Philip Schaff and Henry Wace (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature, 1894), 440 altered, substituting “Christ” for “He”; see discussion of the background on 198–99.

[15] Athanasius, On the Incarnation 54.3, trans. John Behr, St. Athanasius the Great of Alexandria, On the Incarnation: Greek Original and English Translation, Popular Patristics Series, no. 44a (Yonkers, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2011), 167.

[16] Athanasius, On the Incarnation 8.4; 18.1; 19.2, trans. Behr, 67, 89, 91.

[17] Athanasius, On the Incarnation 20.4; 54.3, trans. Behr, 95, 167.

[18] I am indebted to my colleague Lincoln Blumell for this insight, shared in conversation.

[19] See the discussion in Lincoln Blumell, “Rereading the Council of Nicaea and Its Creed,” in Standing Apart: Mormon Historical Consciousness and the Concept of Apostasy, ed. Miranda Wilcox and John D. Young (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 196–217 (esp. 206–8).

[20] The cross in various forms began to appear in Christian art in the fourth century. The staurogram—a combination of the Greek letters tau and rho that scribes inserted into the Greek words for “cross” and “crucify” in some third/

[21] Felicity Harley-McGowan, “Death Is Swallowed Up in Victory: Scenes of Death in Early Christian Art and the Emergence of Crucifixion Iconography,” Cultural Studies Review 17, no. 1 (2011): 118.

[22] Harley-McGowan, “Death Is Swallowed Up in Victory,” 114.

[23] Robin M. Jensen, “The Passion in Early Christian Art,” in Perspectives on the Passion: Encountering the Bible through the Arts, ed. Christine E. Joynes (New York: T&T Clark, 2007), 60.

[24] Allyson Everingham Sheckler and Mary Joan Winn Leith, “The Crucifixion Conundrum and the Santa Sabina Doors,” Harvard Theological Review 103, no. 1 (2010): 80.

[25] Harley-McGowan, “Death Is Swallowed Up in Victory,” 119.

[26] Sheckler and Leith, “Crucifixion Conundrum,” 67, 73; but note that the panel appears at the top of the massive doors, relatively far from the viewer; it is not known whether the panels now appear in their original arrangement.

[27] Jensen, “Passion in Early Christian Art,” 58–59; Sheckler and Leith, “Crucifixion Conundrum,” 80–85; for discussion of the orans (praying figure) in early Christian art, see Robin M. Jensen, Understanding Early Christian Art (London: Routledge, 2000), 35–37.

[28] Jensen, “Passion in Early Christian Art,” 58.

[29] On the relatively late appearance of cross and crucifixion iconography, see the discussions in Jensen, Understanding Early Christian Art, 130–55; Felicity Harley, “The Crucifixion,” in Picturing the Bible: The Earliest Christian Art, ed. Jeffrey Spier (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), 227–32; and Sheckler and Leith, “Crucifixion Conundrum.”

[30] See Robin M. Jensen, The Cross: History, Art, and Controversy (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2017), 92–96, 155–70.

[31] For further discussion on Christ’s real experience of temptation, see Blumell, “Rereading the Council of Nicaea”; Stephen E. Robinson, Believing Christ: The Parable of the Bicycle and Other Good News (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992), 112–16.

[32] See the discussion on this topic in Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, “‘That’s How I Imagine He Looks’: The Perspective of a Professor of Religion,” BYU Studies 39, no. 3 (2000): 91–99.

[33] Holzapfel, “That’s How I Imagine He Looks,” 93. In the 2001 BBC documentary Son of God, Richard Neave drew upon the fields of forensic anthropology and art history to create a model of what a first-century Palestinian Jewish man like Jesus might have looked like: about 5'1" tall, 110 pounds, with short, dark, curly hair (see 1 Corinthians 11:14), dark eyes, a darker, more olive complexion than traditional western art has portrayed, and in Jesus’s case he would be somewhat muscular and weatherworn (because of his work as a carpenter/

[34] Noel A. Carmack, “Images of Christ in Latter-day Saint Visual Culture, 1900–1999,” BYU Studies 39, no. 3 (2000): 41; Adele Reinhartz, “Jesus in Film,” in The Blackwell Companion to Jesus, ed. Delbert Burkett (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011), 521–22.

[35] James C. Christensen, “That’s Not My Jesus: An Artist’s Perspective on Images of Christ,” BYU Studies 39, no. 3 (2000): 13. Though current LDS teaching understands Christ’s atonement as encompassing events from Gethsemane to his death on the cross, and culminating in his resurrection (see True to the Faith: A Gospel Reference [Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2004], 17), LDS artists have often focused on Gethsemane, perhaps seeking a distinctively LDS way to visualize the atonement, perhaps in some cases forgetting the salvific importance of the crucifixion.

[36] http://

[37] http://

[38] Richard Oman, “‘What Think Ye of Christ?’ An Art Historian’s Perspective,” BYU Studies 39, no. 3 (2000): 85, 89.

[39] For example, see Matthew 9:10–12; 11:19; Luke 7:39; 15:1–2; 19:7.

[40] Matthew 27:50; Mark 15:34; Luke 23:46.

[41] On humor and sarcasm in Jesus’s teaching, see Holzapfel, “That’s How I Imagine He Looks,” 93–94; Elton Trueblood, The Humor of Christ (New York: Harper & Row, 1964).