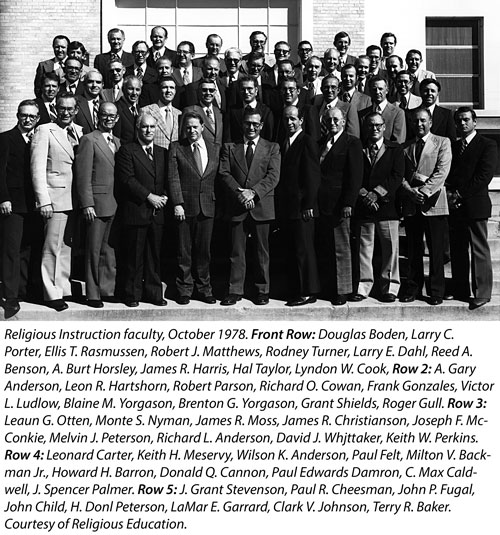

The Hub of the University: 1970–79

Richard O. Cowan, "The Hub of the University," Teaching the Word: Religious Education at Brigham Young University (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2008), 35–52.

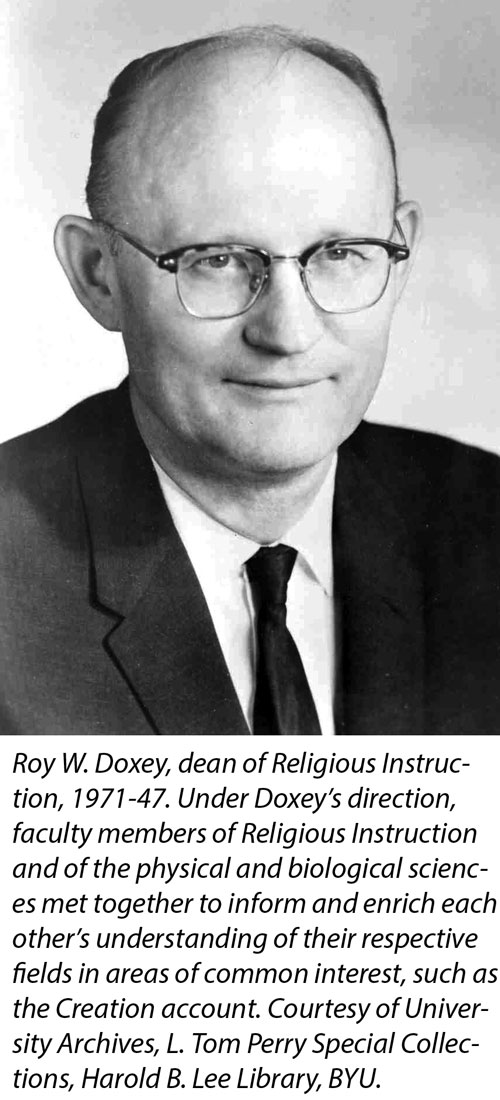

In 1971, when Brother Ludlow was appointed director of instructional materials for the Church, Roy W. Doxey, who had served as assistant or acting dean twice for a total of three years, became dean. Dean Doxey received BA and MA degrees in economics from George Washington University. He presided over the Eastern States Mission, served on the YMMIA general board, and was president of the Provo Stake. In 1972 he became a regional representative of the Twelve. He authored six books, as well as the Relief Society lessons for sixteen years, mostly dealing with the Doctrine and Covenants. Thus, Dean Doxey had especially close contact with the General Authorities for nearly a third of a century.

A New Status for Religious Education

The appropriateness of giving graduate degrees in religion had been a topic of discussion for several years. Those favoring these degrees pointed out the need for seminary and institute teachers to have specialized preparation in the subjects they teach; furthermore, the research done by these graduate students had made a valuable contribution to scholarship and understanding of Latter-day Saint history and theology. Opponents were concerned that professional preparation might eclipse spiritual qualification for teaching religion. A practical problem was that if a person were released from the seminaries and institutes system, a religion degree from BYU would not be very marketable elsewhere. Furthermore, most institute teachers felt their graduate degrees would have more respectability “across the street” if they were not in religion.

On May 3, 1972, the Board of Trustees decided that the College of Religious Instruction would no longer offer doctoral degrees.[1] “This decision could not help producing, in the minds and feelings of many faculty members, several serious questions,” noted Elder Packer later. “The way the decision was accepted by the faculty of the college is indeed a remarkable thing in the history of education and in the history of the Church.”[2] Minors were to be developed on the master’s and doctoral levels, and graduate courses for the benefit of seminary or institute personnel continued to be offered on the BYU campus or at other locations as needed.[3]

Early in 1973, university leaders suggested that Religious Instruction drop the designation “college.” There never had been undergraduate majors in religion, and now graduate degrees in this area were being phased out. Furthermore, Religious Instruction should be a unit providing service for the entire university rather than just another academic college. Some religion teachers feared, however, that the loss of college status would substantially lessen the prestige and hence, the importance of Religious Instruction in the eyes of the faculty, students, and Church membership in general.

If Religious Instruction was not to be a college, what was it to be? This question was considered thoughtfully by university and college administrators. “Department” status was rejected because religious instruction includes more areas and provides a much broader service than that usually identified with other university departments. “Division of Religion” was declined because Religious Instruction was not comparable with other university divisions and because the name might be said, tongue in cheek, to reflect a disunity that does not exist. Religious Instruction was not an “institute,” as that designation on other university campuses normally refers to temporary programs. Furthermore, Church members think of institutes of religion as being adjacent to and completely detached from universities. The solution was to suit the name to the function and refer to this unit simply as “Religious Instruction.” Roy W. Doxey would retain the title “dean” and continue to be a member of the deans’ council. At about this time, Evelyn Scheiss filled the new position of administrative assistant to the dean. As part of Religious Instruction’s change in status, the Department of Philosophy was transferred to the College of General Studies. This left the two departments which would characterize the organization for at least a quarter of a century.

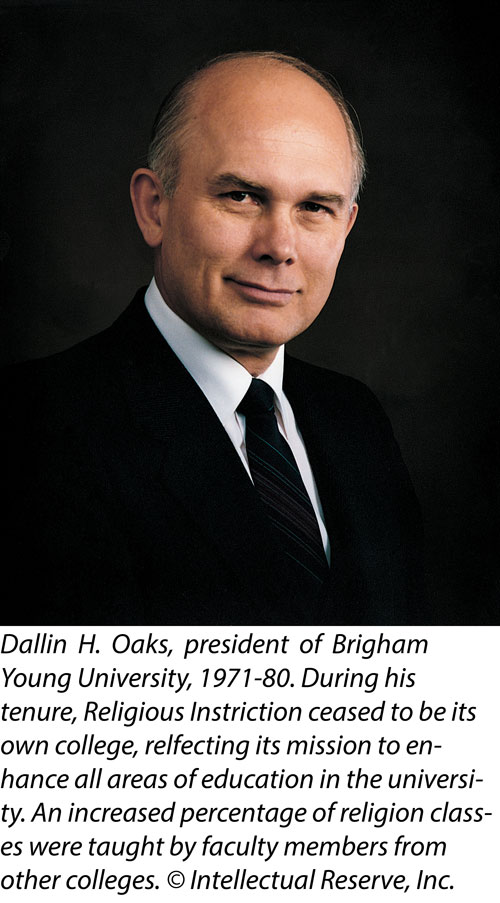

BYU president Dallin H. Oaks declared: “This move emphasizes the prominence of religious education of BYU by affirming its centrality to the University and erasing the restrictive college boundary.” Religion classes would continue to be taught primarily by the full-time faculty of Religious Instruction, but, to an increasing extent, qualified faculty members from other colleges across campus would also be called on to instruct these classes. “The teaching of religion is a university-wide concern which will be fostered by a university-wide jurisdiction,” President Oaks declared. It would make it easier to involve faculty from throughout the university in the teaching of religion. President Oaks pointed out, “Scholarship in religious subjects is widespread throughout the faculty since the LDS Church is administered by a lay priesthood, and lifelong study and teaching of scriptures and doctrines is encouraged and practiced. Consequently, . . . many professors are preeminently qualified to teach religious subjects as well as their particular academic disciplines.” Therefore, President Oaks explained, whenever faculty members are employed by BYU, in whatever department, they should also be considered as potential teachers of religion. In 1973 about 10 percent of all religion classes were taught by faculty from other colleges; President Oaks anticipated that this might be increased to about 20 percent in the foreseeable future. President Oaks affirmed, however, “We shall, of course, continue to depend on full-time faculty in Religious Instruction for the leadership and scholarship necessary to improve further our effectiveness in the teaching of religion.”[4] Elder Packer concurred, insisting that the board never even considered the possibility of doing away with the full-time religion faculty. “Your work has now moved from a college to the University,” he emphasized.[5]

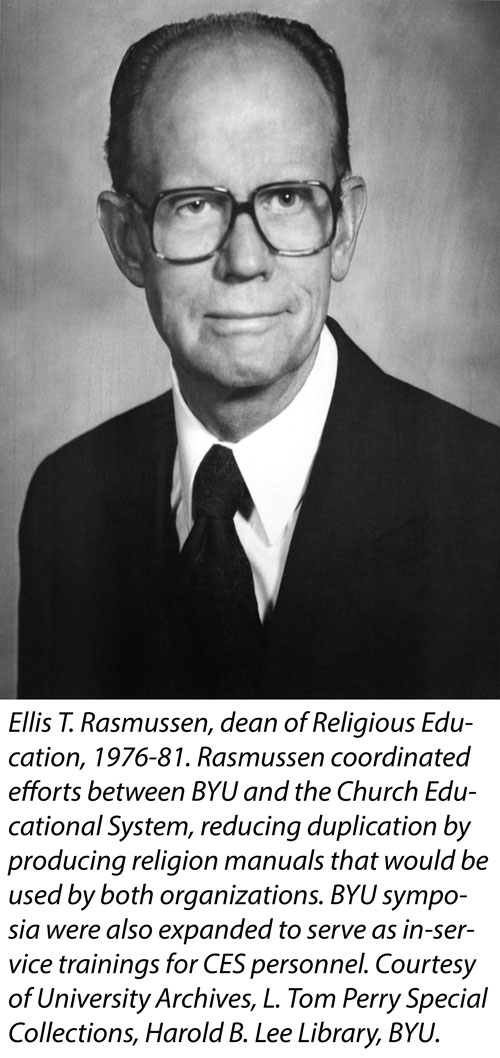

Typical of these efforts to break down barriers was a series of science and religion seminars. These had been initiated in 1971 under the direction of Dean Doxey and were conducted by Ellis Rasmussen, the assistant dean. A selected group of faculty members from Religious Instruction, as well as from the physical and biological sciences, met regularly to discuss issues of common interest. “When these groups get together, they not only come to understand each other better,” Rasmussen believed, “but they also enrich one another. There are discoveries in the physical and biological sciences which we in Religion should understand, and there are technicalities of doctrine and scriptural history which they probably would not know.” For example, the group was fascinated to learn the connotations of Hebrew words used in the Genesis account of the Creation, as explained by Dr. Rasmussen.[6]

“Senior Seminars in Religion” were another means by which colleges across campus participated in religious instruction. These one-credit classes were taught by experts in the sciences, humanities, or business, who explained how they correlated the gospel with their respective disciplines. First offered during the 1973–74 academic year, these Religion 490 seminars were under the supervision of the Department of Church History and Doctrine. In later years some colleges expanded their offering to two credits.

Religion at the Hub of the University

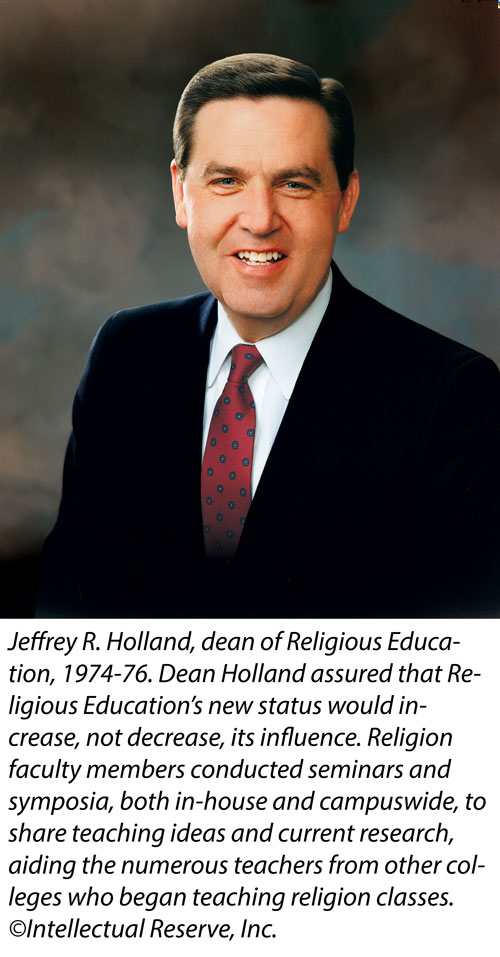

Upon Dean Doxey’s retirement, Jeffrey R. Holland was appointed dean of Religious Instruction on January 11, 1974. Though only thirty-three at the time of his appointment, Dean Holland had earned a PhD in American studies at Yale University, had served as a bishop and as a member of a stake presidency, and had directed the institute adjacent to the University of Washington. At the time of his call, he was director of the Melchizedek Priesthood MIA Churchwide. Elder Packer testified that this appointment had been made by the board through inspiration; “mostly it was done in the way a bishop is chosen, or a stake president, or a General Authority.”[7]

At the outset of his service, Dean Holland affirmed his determination to do all possible to advance the dignity, stature, and importance of teaching religion at BYU. He believed that the end of college status had “opened the gates” for religion to become “an influence everywhere on the campus.”[8] He visited deans, department leaders, and key scholars across campus. In a friendly and informal manner, he sought to convince them that religion was not the function of just one college but rather of the whole university. It was at the heart of BYU’s unique contribution, and all other faculties should feel that they had a responsibility in it. Dean Holland declared: “To me it is a great new era to see the possibility of religious discussion permeating the University.”[9]

As part of this broadened emphasis, the “transfer faculty” program was promoted. By 1976 the share of classes taught by members of other departments increased from 9 to 22 percent. The number of cross-campus faculty members grew from about thirty-five to eighty-five. The plan was to rotate these teachers so more could have the opportunity.

Responsibility for administering this growing program was delegated to assistant dean Ellis T. Rasmussen. He supervised the work of all part-time teachers, including the transfer faculty, visiting seminary and institute teachers, graduate students, and selected individuals from off campus. He also coordinated schedules and budgets with other departments and with the Church Educational System (CES).

Area coordinators also assumed a more important role. They conducted regular seminars for teachers of each subject to share background information, teaching ideas, or results from current research. These efforts were especially valuable in Book of Mormon and gospel principles classes, where there were more transfer teachers.

Dean Holland assured the full-time faculty that there was no danger of their services or existence being phased out, and he sought to help them feel more comfortable in religion’s new campuswide role. “At the Church’s university, Religion is at the hub of the wheel,” he declared. He emphasized that there should be no tension between teachers of religion and scholars in other fields.[10]

Some faculty members felt that they were so busy teaching classes or working on their own projects that they did not have enough time for interaction with one another. To remedy this, a Friday noon “brown bag seminar” was launched during the 1974–75 school year. Faculty members took turns leading gospel discussions, reporting research, or seeking feedback on articles then in preparation. These sessions, generally “in-house,” were intended to give the faculty a greater opportunity simply to “hear one another.”[11]

During these years Religious Instruction sought to reach out more effectively to the broader campus community and beyond. The family of Sidney B. Sperry had established a research fund in his honor to promote original research of general interest.[12] In 1973 the annual Sperry Lecture Series was inaugurated. In 1975 it featured not only a member of the Religious Instruction faculty but also a professor from another department on campus as well as a scholar from CES, beyond BYU. This was the beginning of a greater “outreach to the entire religious education community.”[13] Furthermore, for the first time, the proceedings of the Sperry Lecture Series were published.

In November 1975, the Department of Ancient Scripture sponsored the first annual Fall Symposium. The Saturday program focused on the Pearl of Great Price. Presenters included five from the religion faculty as well as the editor of the Ensign and an institute member. About a thousand people attended, and the resulting publication enhanced “the image of good orthodox scholarship at BYU.”[14]

In April 1976, Dean Holland was named commissioner of education for the Church.[15] His successor was Ellis T. Rasmussen, a longtime faculty member who had been serving as assistant dean for five years. Under Dean Rasmussen’s leadership, the emphasis on Religious Instruction’s broadened role continued.

Dean Rasmussen continued a close working relationship with CES. In previous decades, separate and often similar manuals were prepared for the institutes and for BYU. Dean Holland and CES administrator Joe J. Christensen believed that working together would benefit both groups and would be far more economical. BYU faculty members with relevant areas of expertise were given reduced teaching loads so they could participate on writing committees. Between 1977 and 1981, new course manuals appeared for LDS Marriage and Family, Sharing the Gospel, New Testament, Book of Mormon, Old Testament, Living Prophets, and Presidents of the Church. A Doctrine and Covenants manual was also nearing publication.[16]

In 1978 the Sperry Lecture was expanded into an all-day symposium. The number of presenters increased from two or three to fourteen. For the first time, a General Authority, Elder Mark E. Petersen of the Quorum of the Twelve, gave the keynote address. Beginning that year the symposium was sponsored jointly by Religious Instruction and by CES. It was intended not only to benefit the university and local communities but also to be a mid-year “in-service enrichment experience for full-time teachers of religion.”[17]

Efforts to enhance communication within Religious Instruction continued. Beginning in the fall of 1980, the weekly Monday Messenger shared announcements, biographical sketches, and brief thoughts.

Research Institutes Sponsored

The Sperry and Fall Lecture Series were only part of Religious Instruction’s efforts to promote research. Beginning in 1961, Religious Instruction sponsored the research-oriented Institute of Mormon Studies to examine Mormonism’s “unique contributions” in various fields. Daniel H. Ludlow, then chairman of the Department of Bible and Modern Scriptures, was named first director.[18] Dr. Truman G. Madsen, who succeeded him in 1966, described it as “an interuniversity institute” that sponsored and published research “in all fields that relate to Mormon culture, its history, thought, and institutions.”[19]

The institute researched and microfilmed source material for the history of the Church in New York, Ohio, and Missouri. It sponsored research by more than fifty separate individuals, in several cases leading to significant publications. Early examples included Milton V. Backman’s work on the historical setting for the First Vision and Richard L. Anderson’s treatise of Joseph Smith’s New England heritage. From 1969 to 1972, the institute cooperated in the preparation of special annual issues of BYU Studies, focusing on the Church in New York and Ohio.

In 1965 a separate Institute of Book of Mormon Projects (later renamed the Book of Mormon Institute) was established to promote and coordinate research related to this book of scripture. Daniel H. Ludlow, who had prepared extensive curriculum materials related to the Book of Mormon, also became the first director of this unit.[20] In 1968 he was succeeded by Paul R. Cheesman, who had conducted numerous expeditions to important archaeological sites in North and South America. Institute projects included examining ancient metal plates, collecting data on the cultural background of ancient America, and translating the Book of Mormon into Hebrew as well as some of the leading Indian languages of Central and South America.[21] In 1972 Dr. Cheesman produced and narrated a half-hour color motion picture, Ancient America Speaks.

Religious Instruction was a cosponsor of the Institute for Ancient Studies, organized in 1973. Hugh Nibley, of the Department of Ancient Scripture, was named director, with R. Douglas Phillips, of the Department of Classical Languages, as associate director. The new institute developed and disseminated “information about ancient manuscripts of religious significance.” Dr. Nibley explained that “the scholarly world is being flooded with newly discovered manuscripts, many of which have a direct bearing on the Church. It is important that LDS scholars have and know these manuscripts.”[22] The institute was housed in the Harold B. Lee Library.

Religious Studies Center Inaugurated

Organized in 1975, the Religious Studies Center (RSC) built on the foundations laid by these earlier institutes. It absorbed the work being done by the Book of Mormon Institute and the Institute of Mormon Studies, which were discontinued. BYU president Dallin H. Oaks explained that the new center would “be a supporting and coordinating agency for all religion-oriented research” campuswide. The RSC would attract donations of funds which could be channeled into various research projects. It would also facilitate publication of the results from these research efforts.

Dean Holland became the director of the RSC. The center was divided into four subject areas, each headed by an assistant director: Church history, LaMar C. Berrett; scripture, Paul R. Cheesman (who had been serving as director of the Book of Mormon Institute); world religions, Spencer J. Palmer; and Judeo-Christian religions, Truman G. Madsen. This organization would be modified in the future from time to time. Members of the center’s advisory board included Daniel H. Ludlow, original director of the former institutes; Joe J. Christensen, of CES; Leonard J. Arrington, Church historian; and Charles D. Tate Jr., editor of BYU Studies.[23]

The RSC sponsored annual symposia. The first, in April 1977, centered on “Deity, Ways of Worship, and Death.” Presenters included BYU religion professors as well as experts from as far away as Japan and Sri Lanka.[24]

Many significant publications have been sponsored by the RSC. The first volume the RSC published was Nibley on the Timely and the Timeless. Other volumes have incorporated papers from various RSC-sponsored symposia, including nine volumes generated by the annual Book of Mormon symposium. One of the most significant publications of the RSC to date may well be the contemporary accounts of the Nauvoo discourses of the Prophet Joseph Smith, The Words of Joseph Smith, edited by Andrew F. Ehat and Lyndon W. Cook. Both Ehat and Cook had received research grants from the RSC and had taught part-time for Religious Education. Truman G. Madsen, who held the Evans chair at the time, opined that for all Latter-day Saints, whether teachers, parents, or scholars, “This book is not only useful, it is indispensable.”[25]

Evans Chair Established

The establishment of the Richard L. Evans Chair of Christian Understanding and the appointment of Truman G. Madsen to be the first occupant of the chair was announced in November 1972. Elder Evans had been a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles and was probably best known as the voice for Music and the Spoken Word in conjunction with the weekly Tabernacle Choir broadcasts.

The idea for such a chair had been proposed by Lowell W. Berry, a member of another faith who had been closely associated with Elder Evans in Rotary affairs and who had been profoundly impressed with his commitment to Christianity. Mr. Berry was the first of fifty individuals who contributed to the six hundred thousand dollars necessary to endow such a professional chair. The chair would be occupied by “a distinguished scholar of Brigham Young University” who would promote Christ-centered “understanding among people of differing religious faiths.”

This appointment enabled Dr. Madsen, a professor of philosophy, to function as a “commuting professor” by underwriting travel to centers of religious learning, academic conferences, and civic or social gatherings, where he could present Latter-day Saint philosophy and history.[26]

Notes

[1] “Revised Religion Requirement of BYU,” 2.

[2] Packer, “Seek Learning,” 31.

[3] Dallin H. Oaks to Roy W. Doxey, June 21, 1972.

[4] Daily Universe, June 12, 1973, 1.

[5] Packer, “Seek Learning,” 32; emphasis added.

[6] Ellis T. Rasmussen, interview by Richard O. Cowan, June 22, 1981.

[7] Packer, “Seek Learning,” 32.

[8] Jeffrey R. Holland, interview by Richard O. Cowan, May 7, 1976.

[9] Daily Universe, June 21, 1974.

[10] Holland interview.

[11] Holland interview.

[12] Sperry Lecture Series (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1975), iii.

[13] Holland interview.

[14] Holland interview.

[15] Church News, April 24, 1976, 3.

[16] Ellis T. Rasmussen, interview with Richard O. Cowan, June 22, 1981.

[17] Sidney B. Sperry Symposium, January 28, 1978, iii.

[18] Daily Universe, May 15, 1961, 1.

[19] Statement prepared by Truman G. Madsen, 1972.

[20] Department chair meeting minutes, June 30, 1965.

[21] College faculty meeting minutes, January 16, 1968; Daily Universe, March 10, 1970.

[22] Church News, June 2, 1973, 12.

[23] Daily Universe, February 27, 1976.

[24] Daily Universe, April 13, 1977.

[25] Andrew F. Ehat and Lyndon W. Cook, eds., The Words of Joseph Smith (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1980), xiv.

[26] Church News, November 4, 1972, 5.