En Route to the Holy Land, May 1896–June 1896

Reid L. Neilson and Riley M. Moffat, eds., Tales from the World Tour: The 1895–1897 Travel Writings of Mormon Historian Andrew Jenson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2012), 285–321.

I could write a great deal on Ceylon, which I found one of the most interesting islands of the sea which I have visited so far on my mission; but I will stop right here for the present. I found the natives of Ceylon, as in many other places, copying the vices of the white man and enlarging upon them, while they are closing their eyes and ears to his virtues. The native traders, guides, and others with whom the visitor comes into contact are generally dishonest in the extreme. Those who sell curios, fruit, etc., will sometimes ask a thousand percent more for their goods than they are worth; and unless a man makes a clear bargain with a guide or driver beforehand, he is sure to be “taken in” and have trouble besides. No matter how much they are paid for their services they always beg for more. Most of the natives are Buddhists and Mohammedans; but there is also a sprinkling of Christians. The Wesleyans commenced missionary work in Ceylon in 1816, the Baptists two years earlier. The so-called American Mission has also made some efforts in Christianizing the island. There are no Latter-day Saints yet.

—Andrew Jenson [1]

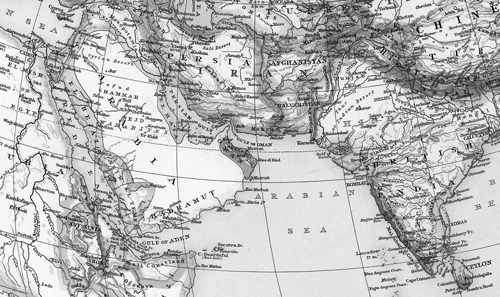

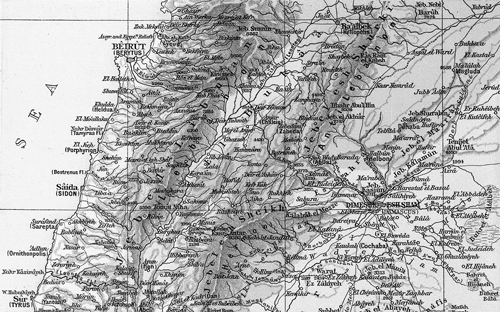

Ceylon to the Holy Land, The Times Atlas (London: Times, 1895), 73-74

Ceylon to the Holy Land, The Times Atlas (London: Times, 1895), 73-74

“Jenson’s Travels,” June 6, 1896 [2]

Suez, Egypt, Africa

After spending about two hours in Albany, Western Australia, I once more boarded the steamer Oroya on Saturday, May 16, and at 6:00 p.m., three hours after anchoring off Possession Point, we sailed for Colombo, on the island of Ceylon, which was to be our next port of call en route for Europe. Our voyage of 3,285 miles from Albany to Colombo was very pleasant, the weather being fine and the sea smooth nearly all the time. I spent most of my time in reading and writing and conversing with fellow passengers. I also took lessons in German from a young lady. As we approached the equator, which we crossed on May 25, the heat became somewhat oppressive, and the nights were so sultry and hot that many of the passengers preferred to sleep on deck. Two concerts, in which songs and recitations predominated, were given in the saloon and on the upper deck, and the time passed quickly and somewhat pleasantly.

The Oroya is a fine modern vessel built at Barrow, England, in 1887, and has all the latest conveniences invented for passenger transportation. (Photo of SS Oroya) She is a vessel of 6,297 tons gross or 3,445 tons register, and the engine has the strength of 7,000 horsepower. She is 460 feet long by 49 broad, and consumes from 80 to 90 tons of coal per day. The crew, including officers and men in all departments, numbers 181. On the present voyage she carries 428 passengers, namely, 44 in the first, 151 in the second, and 233 in the third class. Most of the passengers travel for pleasure, some to improve their health, a few on business, and a limited number returns to England displeased with their fortunes in the “colonies.” Among the passengers are clergymen, merchants, sportsmen, people of leisure, etc. Several have wives and children along, and most of the people in the second class, where my own lot is cast, are sociable and respectable; there are, however, a few exceptions to that. Some of them are “religious” beyond a “sensible limit,” while others profess no religion at all, and others again are policy people who aim to belong to the most popular church in the “neighborhood where they reside.” The Church of England and Presbyterians, I believe, predominate onboard, and there are also some Roman Catholics, including two priests.

On Tuesday, May 26, early in the morning land was seen far away to the northwest. It was the island of Ceylon, close to the shores of which we now sailed for about one hundred miles; and as we approached the coast, scenery became more and more interesting. At 4:00 p.m. we rounded the outer end of the breakwater, where a lighthouse is built, and swung into position for anchorage on the inside, where a great number of vessels were already anchored, this being a port of great importance. Most of the vessels floated the British Jack from their mastheads. Soon after we had anchored, the harbor was literally alive with natives, who approached the ship in boats and canoes of different sizes and make. Some came to trade, others to take passengers ashore, and others again, mostly boys, to perform diving and swimming feats in which they were great experts. The motley crowd made strange and deafening noises, particularly the divers, who would plunge in for the smaller silver coin thrown in the water but refused to dive for coppers.

After tea or supper, most of the passengers landed to spend the night on shore, I among the number, and after taking a prolonged walk through some of the principal streets of Colombo, I put up at the Australia House, together with some fellow passengers. From the moment we landed till we hid ourselves behind the doors of our hotel, we were besieged almost at every step by natives, who wanted to act as guides and wheel us around in their jinrickshas, a light, two-wheeled cart pulled by one man, which are now used very extensively on the island of Ceylon, and particularly in Colombo. It is not used only by the white people but also by the native businessmen and others of the higher castes. The next morning I took a five-mile ride in one of these little vehicles, which I thoroughly enjoyed for the novelty of the thing. To travel on wheels where human flesh is the propelling power has never fallen to my lot before. As there were also a great variety of horse vehicles which could be hired at the same rates as the jinrickshas, this was a clear case of competition between human flesh and horseflesh. On my ride I visited the celebrated Cinnamon Gardens, the museum, the native market, the general market, the railway station, government buildings, public parks, etc. I also took a walk through the fortifications near the wharf, where a great body of men and women were employed in packing rocks for a new road running along the seashore. We were told by one of the native foremen who could talk English that the government only paid these people one quarter of a rupee—equal to about 7 United States cents—each for a day’s work of from ten to twelve hours; and even that was considered good wages. The value of an Indian rupee is 14 pence, or about 28 cents of United States coin. This low rate is to be ascribed to the present cheapness of silver. Small as the wages are in Ceylon, they are much lower in India proper. According to official reports, there are several millions of people in southern India whose annual earnings, taking grain, etc., at its full value, do not average per family of five more than $20, or 35 cents per month for each individual—equal to a little more than one cent per day. Incredible as this may appear, it is true, although with better times in India at present perhaps two cents per day would be a safe average rate. Sixty cents a week is enough to keep an Indian peasant with wife and one or two children in comfort; but good authorities state that there are eight millions of people in India who cannot earn even this much. To such a people the planting colony of Ceylon, where a person, male or female, can earn 7 cents a day, is a genuine El Dorado, for he can save from half to three quarters of that amount right along.

Ceylon is the largest, most populous, and most important of all British Crown colonies. One enthusiastic poet says it has long been

Confessed the best and brightest gem

In Britain’s orient diadem.

It is believed that Ceylon was known to ancient navigators as far back as the time of King Solomon, of whose Ophir and Tarshish many believe Ceylon to have formed a part. Its jewels and its spices were familiar to the Greeks and Romans, who called it Taprobane, and to the Arab traders, who first introduced the coffee plant. It was also known to the Mohammedan world at large, who to this day regard the island as the Elysium prepared for Adam and Eve to console them for the loss of Paradise. On the basis of this story, the reef running between the island and India has been named Adam’s Bridge, while the most conspicuous and majestic, though not the highest, mountain in the island has been known as Adam’s Peak. To the people of India, to the Burmese, Siamese and Chinese, Ceylon—which is called “Lanka, the Respondent”—was equally an object of interest and admiration, and it is admitted that no island in the world, Great Britain not excepted, has attracted the attention of authors in so many different countries as has Ceylon. It is also asserted that there is no land which can tell so much of its past history, not merely in songs and legends but in records which have been verified by monuments, inscriptions, and coins. Some of the structures in and around the ancient capitals of the Singhalese (the name given to the natives of Ceylon) are more than 2,100 years old, and only second to those of Egypt in vastness of extent and architectural interest. Between 543 BC (when Wijava, a prince from northern India, is said to have invaded Ceylon, conquered the native rulers, and made himself king) and the middle of the year 1815 (when the last king of Kandy, a cruel monster, was deposed and banished by the British) the Singhalese chronicles present the world with a list of nearly 170 kings and queens, the history of whose administrations is of the most varied and interesting character, and it indicates the attainment of a degree of civilization and material progress very unusual in the East at that time. At different times the Singhalese made successful incursions into neighboring countries, while at other times they in turn were subdued by others, once by the Chinese, to whom they paid tribute for years. Ceylon was, however, exposed chiefly to incursions of Malabar princes and adventurers with their followers from southern India, who waged a constant and generally successful contest with the Singhalese. The northern and eastern portions of the island at length became permanently occupied by the Tamils (natives of southern India), who placed a prince of their own on the Kandyan throne; and so far had the ancient power of the kingdom declined that when the Portuguese first appeared in Ceylon in 1503, the island was divided under no less than seven separate rulers. For 150 years the Portuguese occupied and controlled the maritime, or lower, districts of Ceylon, but it was more of a military occupation than a regular government, and martial law chiefly prevailed. Under Portuguese rule some of the inhabitants were converted to the Catholic form of Christianity, and royal monopolies in cinnamon, pepper, and musk were established, and they exported cardamoms, sapan wood, areca nuts, ebony, elephants, ivory, gems, pearls, etc. The Dutch, who by 1656 had finally expelled the Portuguese rulers from the island, pursued a far more progressive administrative policy, though their doings were selfish and oppressive in commercial matters. They, like the Portuguese, were confined to the low country, as the king of Kandy defied all European invaders. The Dutch did much to develop cultivation and to improve the means of transportation, mostly through the construction of canals. A lucrative commerce was established with Holland and other countries, the Protestant religion was introduced and a number of other improvements made. Cinnamon was the great staple of export, next came pearls, elephants, pepper, areca or betel nuts, jagger sugar, sapanwood and timber generally, arrack spirit, choya roots, cardamoms, etc. The cultivation of coffee and indigo was begun but not carried on to such an extent as to benefit the exports.

Though agriculture was promoted by the Dutch for selfish purposes, good resulted therefrom, as in the case of the planting of coconut palms along the western coast. Thus when the British superseded the Dutch in 1796, the whole of the southwestern shore for nearly 100 miles presented an unbroken grove of palms, which is seen to this day. From 1796 to 1802 Ceylon was placed under the East India Company’s control, who administered it from Port St. George, Madras; but in 1802 it was made a Crown colony. It soon became evident that there could be no settled peace until the tyrant king on the Kandyan throne was deposed and the whole island brought into subjection to British rule. This was accomplished in 1815, when, at the instigation of the Kandyan chiefs and people themselves, Wikkrama Simba, the last king, was captured and deposed and exiled by the British to southern India. Since that time Great Britain has ruled Ceylon without any trouble.

When the British took possession in 1796, the total number of inhabitants on the whole island was estimated at less than one million; there are now over three millions. Colombo had about 28,000 inhabitants against 130,000 at the present time.

Colombo of today has much to interest the visitor, among which may be mentioned its fine artificial harbor, its beautiful drives, its lakes and river, its public museum, the old Dutch church, the bungalows and gardens of the Europeans, etc. Still more unique are the crowded native parts of the town teeming with every variety of oriental race and costume. Of the different races may be mentioned the effeminate light brown Singhalese, the real natives of this land, of whom both men and women tie their hair behind in knots, the former patronizing combs and the latter elaborate hairpins. Then there are the darker and more manly Tamils, Hindus of almost every caste and dress, Moormen or Arab descendants, Afghan traders, Malay policemen, a few Parsees and Chinese, Kaffir mixed descendants, besides the Eurasians of Dutch or Portuguese or English and native descent.

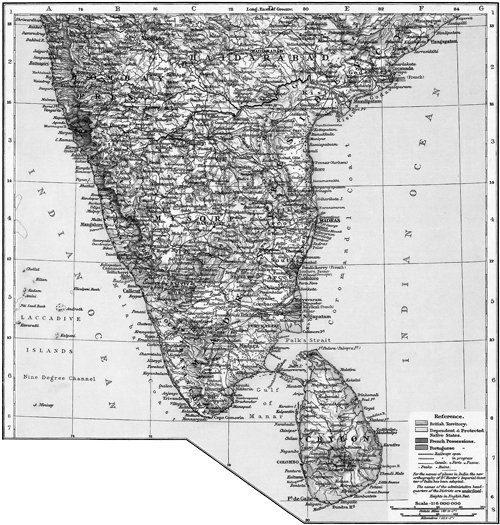

Although the mean temperature of Colombo is nearly as high as that of any station in the world as yet recorded, yet the climate is called healthy and safe for Europeans because of the slight difference between night and day, and between the so-called seasons, of which, however, nothing is known there, it being one perpetual summer, varied only by the heavy rains of the monsoon months, May, June, October, and November. There are about 4,000 miles of road in Ceylon, also about 300 miles of railway;1,500 miles of telegraph wire; and 250 post offices. Ceylon proper is about 250 miles long from north to south and about 150 miles broad in its widest part. Its shape is very much that of an egg; it is nearly surrounded by coral reefs. Colombo is distant 900 miles from Bombay; 600 from Madras; 1,400 from Calcutta; 1,200 from Rangoon (Burma); 1,600 from Singapore; 2,500 from Mauritius and about the same distance from Madagascar; about 4,000 from Natal; 3,000 from Hong Kong; 3,000 from Fremantle or Western Australia; and about 2,200 from Aden, Arabia.

Ceylon, The Times Atlas (1895), 81

Ceylon, The Times Atlas (1895), 81

Ceylon is almost connected with the continent of Asia (India) by the island of Rameswaram and the coral reef called Adam’s Bridge. In extent it comprises nearly sixteen million acres, or 24,702 square miles, apart from certain dependent islands. The total area is about five-sixths of that of Ireland. One-sixth of this area, or about 4,000 square miles, is comprised of the hilly and mountainous country which is situated about the center of the south of the island while the maritime districts are generally level, and the northern end of the island is broken up into a flat narrow peninsula and small inlets. Within the central zone there are 150 mountains or ranges varying in height from 3,000 to 7,000 feet, with ten peaks rising over the latter limit. The highest mountain is Pidurutalagala, which is 8,296 feet above the level of the sea. The summit of Adam’s Peak, which for a long time was considered the highest point on the island, is 7,353 feet high. To voyagers approaching the coast, the latter is the most conspicuous mountain of Ceylon. The longest river of the island is the Mahaweli Ganga, which has a course of nearly 150 miles, draining about one-sixth of the area of the island. There are five other good-sized rivers besides numerous tributaries and smaller streams. The principal products of Ceylon are rice, tea, coffee, cinnamon, coconuts, cardamoms, nutmeg, clove, pepper, vanilla, ginger, breadfruit, sugarcane, gum, chocolate plants, cacao, cinchona, cotton, tobacco, rubber trees, blue gums, etc. It is estimated that there are 700,000 acres under rice or paddy at the present time, and about 150,000 under dry grain, Indian corn, and other cereals. Ceylon cinnamon is considered the finest in the world. It was known through Arab caravans to the Romans, who paid in Rome the equivalent of £40 per pound for the fragrant spice. Ceylon is sometimes called the “mother of cinnamon,” and “Cinnamon Isle.” In 1891 the export of cinnamon was as high as 2,309,774 pounds in bales and 588,264 pounds in chips, which was raised on about 35,000 acres of land. The cultivation of palms is of the greatest importance to the island. There are thirteen different kinds. It has been commonly remarked that the uses of the coconut palm are as numerous as the days of the year. Percival, a noted navigator, relates that early in the present century a small ship from the Maldive Islands arrived at Galle, Ceylon, which was entirely built, rigged, provisioned, and laden with the produce of the coconut palm. Food, drink, domestic interests, materials for building and thatching, roine [sic], sugar, and oil are among the many gifts to man of these munificent trees. Some years ago the crew of a wrecked vessel cast away on a South Sea Island subsisted for several months on no other food than coconuts and boiled fish and added to their weight in that time. The average value of the annual products of the coconut palm from Ceylon is about $3,600,000, while the value of the produce locally consumed is estimated at about eight million dollars. There are perhaps thirty million coconut palms cultivated in Ceylon covering about 500,000 acres, all but about 30,000 acres being owned by the natives. The annual yield of nuts is supposed to be 500 millions.

The breadfruit tree, the jack, orange, and mango, as well as gardens of plantains and pineapples, melons, guavas, papaws, etc., are also among the products cultivated and of great use to the people of Ceylon. There is scarcely a native landowner who does not possess a garden of palms, or other fruit trees besides rice fields.

I could write a great deal on Ceylon, which I found one of the most interesting islands of the sea which I have visited so far on my mission; but I will stop right here for the present. I found the natives of Ceylon, as in many other places, copying the vices of the white man and enlarging upon them, while they are closing their eyes and ears to his virtues. The native traders, guides, and others with whom the visitor comes into contact are generally dishonest in the extreme. Those who sell curios, fruit, etc., will sometimes ask a thousand percent more for their goods than they are worth; and unless a man makes a clear bargain with a guide or driver beforehand, he is sure to be “taken in” and have trouble besides. No matter how much they are paid for their services, they always beg for more. Most of the natives are Buddhists and Mohammedans; but there is also a sprinkling of Christians. The Wesleyans commenced missionary work in Ceylon in 1816, the Baptists two years earlier. The so-called American Mission has also made some efforts in Christianizing the island. There are no Latter-day Saints yet.

“Jenson’s Travels,” June 7, 1896 [3]

Cairo, Egypt, Africa

At 1:40 p.m. on Wednesday, May 27, 1896, I continued my voyage from Colombo, Ceylon, still a passenger on the steamship Oroya, and we were now bound direct for Suez, our next port of call. The voyage over the upper part of the Indian Ocean, the Arabian Sea, the Gulf of Aden, the Red Sea, and the Gulf of Suez, was uneventful; the weather was exceptionally good, and we only encountered one monsoon in the Indian Ocean, and that was of a mild character and only lasted two days.

Our general course from Colombo to the mouth of the Red Sea was west-northwest; up the Red Sea we went in a more northerly direction. (The 1895 Times Atlas p.73 has a map connecting Ceylon to the Mediterranean Sea that could be cropped to fit on half a page. It includes the course of the Nile. You’ll need to get a clean copy from <davidrumsey.com>.)

The first land we sighted after leaving Colombo was the island of Socotra, which lies off the African coast about 150 miles from Cape Gwardafuy—also called Ras Asir, which is the extreme northeastern point of Africa. Socotra is a mountainous island eighty-two miles long and about twenty miles wide, with an Arabian population under British protection. We passed this island on June 1. Two days later (June 3) we passed Aden, in Arabia, within a distance of about ten miles. Formerly the Orient steamers called at Aden, but there being only a very little business to do the ships now steam proudly by. Aden is 2,094 miles from Colombo and 1,308 miles from Suez. This British seaport is sometimes called the Indian Gibraltar and consists of a peninsula situated on the southeast coast of Arabia, about ninety miles from the entrance to the Red Sea at Bab al Mandeb, in latitude 12º47´ N and longitude 54º10´ E. Originally it formed part of the large province of Yemen, in Arabia Felix; but for nearly half a century it has been included in British territory under the immediate control of the government of Bombay. The whole area is estimated at thirty-five square miles and the population at least not less than 20,000 souls, exclusive of the garrison. Aden is further described as a large crater formed of lofty precipitous hills, of which the highest peak is reckoned at 1,775 feet. The peninsula is connected with the Arabian continent on the north side by a narrow neck of land which is partially covered, at high spring tides, by the sea. But a causeway and aqueduct, which supplement, as it were, the natural isthmus, are always above water. The town of Aden and part of the military cantonment are within the crater. Stone and mud buildings, of which some are double storied, constitute the former. During the first quarter of the present century, England had occasion to demand from the Arab authorities of the day satisfaction for injuries to her Indian subjects; but owing to the failure of negotiations and treacherous behavior on the part of the sultan’s son, the port was bombarded and seized by a combined naval and military force; and in January 1839, it became a possession of the British Crown. As a military station, Aden is not popular. Its local attractions are rather for the visitor than for the resident, and its climate is trying to Europeans.

About noon on June 3, the coast of Africa was in plain sight on our left, and about 1:00 p.m. we passed through the straits of Bab al Mandeb (the Gate of Tears) into the Red Sea, with the island of Perim on our right. This little island lies in the Straits of Bab al Mandeb (the Gate of Tears) a mile and a half from the Arabian, eleven miles from the African coast, and forty miles south of Jabal Zuqar. It is in latitude 12º42½´ N, longitude 43º23´ E, and its area is about seven square miles. It contains barely 250 inhabitants including the garrison. Long low ranges of hills and salt sandy flats are the distinguishing physical features. Altamont, the highest point of the island, selected for the display of a flagstaff, is 214 feet above the sea level. Perim was taken possession of by the British in 1799 but was soon abandoned as strategically unfit for protection purposes; but it was reoccupied again by the English in 1857, since which it has been in British possession. In 1861 a lighthouse was erected on it for facilitating the navigation of the straits by the many steamers passing to and fro between Suez and the seas to the eastward. In 1885 it was made a signal and telegraph station.

We had been led to believe that we would suffer awfully with the heat in passing through the Red Sea, but such was not to be our experience, as we were favored with a cool north wind, which blowed almost continuously while we passed over that historic body of water. Our vessel being a large one, it kept pretty well in the middle of the sea, and consequently neither the African nor the Arabian coasts were seen by us. This was somewhat disappointing to me, as I had hoped to get a glimpse of those particular parts of Arabia where the sacred cities of the Mohammedan—Mecca and Medina—are situated. All the way from Aden to Suez we met and passed steamers every day, this being the great highway from Europe to India and Australia.

On June 5 we crossed the geographical line known as the Tropic of Cancer, and I for one was much pleased to get back into the North Temperate Zone once more. The next day (June 6) we passed on our right two little rocky islets called the Brothers, which rise from a depth of 250 fathoms to a few feet above sea level. There is a lighthouse on one of them. In passing these islets on our right, we were abreast of Quseir, an Egyptian port on our left, where the great Nile in its windings most closely approaches the Red Sea, the distance between the sea and the river at this point being only 120 miles.

Early in the afternoon the mountains and desert sands of Africa were seen on our left, and soon afterwards the heights of the Sinai Peninsula showed themselves to our view ahead on our starboard side. At 4:00 p.m. we were sailing abreast of Shadwan Island on our left. This is a large and very picturesque island, lying off the African or Egyptian coast. On its southern point there is a lighthouse 120 feet above the level of the sea. The fine mountain behind is supposed, in the imaginations of some, to take the shape of a giant’s head and shoulders and is called Montenegro. About sundown we sailed through the Straits of Gubal, which is the entrance from the Red Sea proper to the Gulf of Suez. The Straits are named from the island of Gubal, which lies immediately north of Shadwan. Later in the evening we were sailing close to African coast, which at this point is quite mountainous.

The mountains nearest to the entrance of the Gulf of Suez consist of a mass of hematite of a deep ruddy hue, rising abruptly to a height of 1,530 feet. This is Jabel Zeit, and the region is famous in fable as well as in modern history. It is so powerfully magnetic that it affects the compass of a ship passing near, and the sea in its neighborhood is often marked with oily patches from the exudation of petroleum. Great hopes were once entertained and great sums spent on borings at this place that the revenues of Egypt might profit; but though a considerable quantity of oil was found, the quality was too poor to make it a profitable article of commerce. The red mountain probably communicated its name to the whole sea, of which it forms the portal, and perhaps some of the wonders of the Arabian Nights were exaggerations of the powers of the mountain of loadstone and of the oily waves. The old Arab name of the Red Sea is Bahr Melch, or the Salt Sea, but Bahr al Ahmar, or the Red, also occurs. Yam Suf, the “Sea of Weeds” is the Hebrew name. The Gulf of Suez was called by the Arab geographers the Sea of Colzoum, a corruption of Clysma, the Greek name of Suez. The Red Sea proper is about 1,200 miles long, with an average width of perhaps 250 or 300 miles. Aside from its historical importance, this sea has a number of peculiarities, one of which is that not a single permanent stream of any size puts into it, the lands on either side being sandy deserts.

As we sailed up the Gulf of Suez, which is only about twenty miles wide on an average, land was in plain view on both sides, but that on the right, though farther away from us than that on the left, was most interesting, as the landscape there included the Sinaitic Mountains and the Wilderness of Sin of Bible fame.

The Sinaitic Mountains, comprising the triangular peninsula between the two arms of the Red Sea, consist of an innumerable multitude of sharp rocky summits thrown together in wild confusion, rising to different heights, leafless and barren without the least trace of verdure to relieve the stern and awful features of the prospect. The rocks which bound the deep, narrow, tortuous ravines between the mountains are basalt, sandstone, and granite variegated with an endless variety of hues from the brightest yellow to the deepest green. The view from one of these summits is said to present a perfect sea of desolation without a parallel on the face of the earth. The valleys, or gorges, between the summits sink into deep and narrow ravines with almost perpendicular sides of several hundred feet in height, forming a mass of irregular defiles, which can be safely traversed only by the wild Arab, who has his habitation in the cliffs of the valleys amid these eternal solitudes. Toward the north the wilderness of mountains slopes down in an irregular curvilinear line which turns outward like a crescent and runs off on the one hand toward the head of the eastern gulf of the Red Sea, and in the other northwest toward the western extremity of the sea itself, near the gulf of Suez at the head of which is the modern town and port of Suez and the south entrance of the Suez canal. This long, irregular crescent marks the outline of a high chain of mountains, El Tih, extending eastward from the Red Sea south of Suez in a continued range to the Atlantic Gulf, or Gulf of Aqaba, a distance of 120 miles, which forms the southern abutment of a high tableland, a vast desert utterly desolate and barren, with a slight inclination to the north toward the Mediterranean Sea. The surface of this elevated plain is overspread with coarse gravel mingled with black flintstone, interspersed occasionally with drifting sand and only diversified with occasional ridges and summits of barren chalk hills. In the time of Moses it was a great and terrible wilderness, and from times immemorial it has been a waste, howling desert, without rivers or fountains or verdure to alleviate the horrors of its desolation. This supposition is, however, that this desert was once supplied, in some measure, both with water and with vegetation. The brother of Joseph repeatedly traversed it from Hebron in the land of Canaan to Egypt, with asses (Genesis 42:26; 43:24). When the country was suffering with extreme dearth, Jacob and his sons went down with their flocks and their herds (Genesis 47:1). But no animal except the camel is now able to pass over the same route. The Israelites to the number of two millions (?) [4] with their flocks and their herds (Exodus 10:9) inhabited portions of this wilderness for forty years where now they could not subsist a week without drawing supplies both of water and provisions from a great distance.

As most of the passengers of the Oroya were professed Christians and consequently interested in Bible geography, all hands were out with opera glasses, telescopes, kodaks, etc., to get glimpses of and take snapshots of the mountains and deserts on our right. Besides the mountains, we could see nothing but sand, which seemed to extend from the seashore up to the base of the mountains and even to penetrate as far into the gorges and defiles as we could see. This desolate region has been clearly identified by biblical students as the Wilderness of Sin, where the Israelites traveled (Exodus 17:1; Numbers 33:11). It extends in a long, narrow plain, between the coast and the mountains, almost to the termination of the Sinaitic Peninsula and is memorable as the place where, in answer to their murmurings, the Israelites were for the first time miraculously fed with quails to appease their lusting after the flesh pots of Egypt (Exodus 10). Here also they were fed with manna, that bread of heaven, which they continued to eat for forty years, until they reached the land of promise and ate of the corn of that land.

Continuing our voyage during the night, we passed the Zenobia lightships on the North port rock early in the morning of June 7. At this point we are abreast of Aba Darray, where, according to the local tradition, the Israelites crossed the Red Sea. Darray means “a stair,” and may refer to the peculiar shape of the mountains. Until a ship passage was dredged, the water here was very shallow, and Napoleon Bonaparte with his generals is said to have attempted a crossing on horseback but was deterred by a change of wind and tide. At 4:00 a.m. we anchored off the mouth of the Suez Canal and near the town of Suez, where we waited about three hours before we commenced the passage through the canal. Soon after anchoring, a number of boats rigged in Egyptian style came out to the steamer; and we soon had a repetition of our experience in Ceylon. Among the wares offered by the natives were some excellent figs and other fruits; but the curios offered for sale were far inferior to those bartered by the natives of Colombo, Ceylon.

Suez is a town of about 20,000 inhabitants and is situated on the desert about two miles from the mouth of the canal. It has a mixed population of natives and Europeans and is connected with Cairo by railroad.

Below Suez the tableland of the desert breaks abruptly off toward the Red Sea into a rugged line of mountains, running south by east, at a distance of eight or ten miles from the shore. Along the interval between the brow of these mountains and the shore lies the route of the Israelites. On the eastern shore of the Red Sea, a short distance below Suez, are several springs of blackish water called Uyun Mousa (the Fountains of Moses), where Moses is supposed to have edited his triumphal song (Exodus 15:1–22). The course of the Israelites now lay, for some distance down the eastern shores of the Red Sea, between the coast on the right and the mountain ridge on the left. Down this coast they went three days’ journey in the wilderness and found no water until they came to Marah, where the waters were so bitter that they could not drink them. Here their murmurings were stilled by the miraculous healing of the waters (Exodus 15:22–25). These waters are still found forty miles below the Fountains of Moses and are so salty and so bitter that even the camels refuse, unless very thirsty, to drink them. The biblical Elim, where there were twelve wells of water and three score and ten palm trees, was six miles from Marah (Exodus 15:27). Here is still found an abundant supply of water, some tillage land, several varieties of shrubs and plants, and a few palm trees. The next encampment was by the Red Sea (Numbers 33:10). At Elim the plain of the coast is interrupted by irregular eminences of a mountain ridge, or spur, that comes from the mountains on the left, and juts out, by high precipitous bluffs, into the sea. Extending for some distance along the coast it presents toward the sea a series of headlands, black, desolate, and picturesque. Turning off from the coast, the traveler passes by a circuitous route around one or two of these headlands and then turns into a valley, which leads again direct to the sea, where he pursues his course along the beach under high bluffs on the left, until he comes into an extensive, triangular plain called the valley of Case, in which is recognized the encampment of the Israelites “by the sea,” distant fifteen or twenty miles from Elim. Near this point the coast again becomes an extensive desert running far down toward the extremities of the peninsula. This is the Wilderness of Sin, which I have already mentioned. The exact route taken by the Israelites from the Wilderness of Sin to Mount Sinai is not known; nor has it been proven beyond a doubt which of the numerous peaks of the Sinaitic range is the veritable Mount Sinai on which the law was given; though some travelers claim to have positive proofs for its exact location.

The mountain from which the law was given is denominated Horeb in Deuteronomy 1:6; 4:10, 15; 5:2; 18:16. In other books of the Pentateuch it is called Sinai. At the time of Moses, Horeb appears to be the generic term for a group and Sinai the name for a single mountain. At a later period Sinai becomes a general name (Acts 7:30–38; Galatians 4:24). As specific names they are now applied to two opposite summits of an isolated, oblong, central ridge about two miles in length from north to south in the midst of a confused group of mountain summits. Modern Horeb is a frowning, awful cliff at the northern extremity overhanging the plain Er Rahah; Sinai, the Mount of Moses, rises in loftier, sterner grandeur at the southern extremity. This overlooks the plain at the south, and on the supposition that this was the station of the Israelites it must be the summit on which the Lord descended in fire to give laws to Israel. The distance between the two summits of Sinai and Horeb is about three miles. The former is more than 7,000 feet above the level of the sea, about 2,000 feet above that of the plains at the base, and 400 or 500 feet higher than Horeb. Mount Sinai is situated about 120 miles from Suez in a southeasterly direction and nearly 100 miles from the head of the Gulf of Aqaba, which is the eastern gulf of the Red Sea. It lies in 28º S latitude. Moses had been a wandering shepherd for forty years in this region, and on or near this same mount had received from the Lord his commission to deliver the children of Israel from their Egyptian bondage. For it was here that Jehovah appeared to the coming prophet in the burning bush. By his intimate acquaintance with the country, Moses was well prepared to conduct the thousands of Israel in their perilous march through this terrible wilderness.

From our anchorage off Suez we had a fine view of mountains, deserts, canal, and sea. The rising of the sun on the Arabian Desert was also very interesting to such as had never seen it before.

One jocular passenger cast out a hook for the purpose, as he said, of fishing up one of Pharaoh’s chariot wheels. This introduced the story of the sailor who, on returning home from a long voyage, told his mother about the flying fish he had seen in foreign seas. His mother disbelieved him and rather rebuked him for telling her what she believed to be a falsehood, as she declared that no kind of fish could fly; they were only made to swim. But when the young man subsequently returned from another voyage on which he had navigated the Red Sea and told his mother that the sailor in passing through had run against one of Pharaoh’s chariot wheels, she believed him readily. This is only another sample of how eager some people are to believe a lie in preference to the truth.

“Jenson’s Travels,” June 8, 1896 [5]

Giza, near Cairo, Egypt

On Sunday, June 7, 1896, at 7:00 a.m., the Oroya lifted anchor off Suez and entered the Suez Canal, which connects the Red Sea with the Mediterranean and is 87 miles long. For the first four miles the canal is cut through the marshes bordering the head of the Gulf of Suez, then through the higher desert; next, it passes through the Bitter Lakes; thence through another narrow cut and next enters the smaller lake called Lake Timsah on which the town of Ismailia, the canal halfway house, is located. Here I broke my voyage in order to visit Egypt and Palestine, and left the Oroya by steam launch at 1:30 p.m. I shall always remember the Oroya, which carried me safely over the billows for a distance of nearly nine thousand miles. I certainly think more of the ship than I do of some of the officers and crew who man it.

On landing at Ismailia, I was politely treated by the representative of Thomas Cook and Son, the great tourist firm, whose name is known all over the world, and that I believe for good. They are doing an immense business, and though they do not get tourists through cheap, they make them very safe and comfortable; and those who are not used to travel cannot in my opinion do better as a rule than to engage their passages through one of the agencies of Thomas Cook and Son.

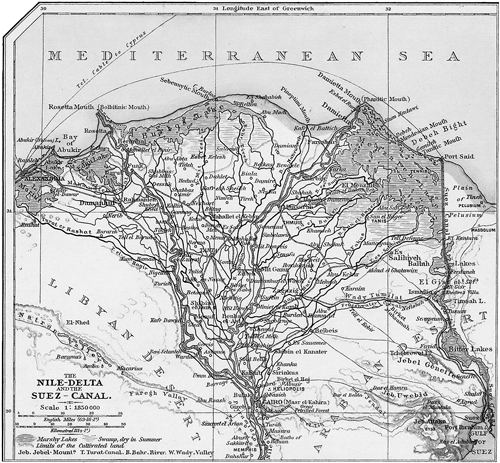

Nile Delta, The Times Atlas (1895), 60

Nile Delta, The Times Atlas (1895), 60

The town of Ismailia is forty-four miles from Suez and forty-three miles from Port Said; by rail via Zagazig and Benha it is ninety-seven miles from Cairo. It is an artificial oasis in the desert and one of the most charming and prettiest spots imaginable. It is also an ideal French town, and its founders predicted that it would soon become one of the important commercial centers of Egypt; but in this they were at least temporally disappointed. The location proved to be an unhealthy one, and consequently most of its people left. It has now only a population of about 10,000, mostly Arabs, but may still have a future. Before the town could be a possibility, a freshwater canal had to be dug from the Nile, which for that purpose was tapped near Cairo. This canal furnishes fresh water for both Ismailia and Port Said and some of the intervening country. The former consists of two towns, to wit, the French city and the native town. The French part is laid out with regular streets; trim houses, and beautiful gardens form a characteristic picture of French taste and neatness and stands out in bold contrast to the surrounding desert. There is also a public park and several long esplanades along the freshwater canal. As this was my first introduction to Egyptian life and scenery, everything I saw was new and interesting. The oriental dress of the people, the long caravans of camels, the little donkeys, the shepherds with their flocks, the African buffaloes, the artificial vegetation of the oasis, etc., etc., were all so many new features to me. I also found a few people who could talk English, among whom was Aziz Maraggi, the local director of the American Mission School at Ismailia. He took great pains to tell me all he knew about the American schools in Egypt and said he labored under the direction of the white missionaries, of whom there were several in Egypt though none at present at Ismailia. In his own school, which is kept in the native town, there are at present 60 students. At Ismailia I drank Nile water for the first time. I also tasted Egyptian coffee, got my eyes full of desert sand, and was annoyed by Arabs who wanted to act as guides when I did not want or need any such—all for the first time.

By way of further explanation, I will state that the town of Ismailia is situated on the Isthmus of Suez, which perhaps most of the readers of the News will know is a neck of land about 72 miles wide in its narrowest part that extends from the Mediterranean on the north to the Gulf of Suez on the south and connects the continents of Asia and Africa. It is a desert of sand and sandstone, whose dreariness is occasionally relieved by a salt lake, or saline swamp but which is almost entirely destitute of fresh water. The principal interest, however, which from a remote antiquity was attached to the region, lies in the possibility of opening up communication through it by means of a ship canal so as to save the long and often dangerous voyage round the Cape of Good Hope. The route to India—so far as passengers, and to a moderate extent merchandise, are concerned—had been greatly shortened by the construction of a line of rail from Port Said to Suez; but it was obvious to every observer that a ship canal would be an infinitely more important boon to commerce.

It is a well-known fact that in ancient times an indirect line of canal did connect the two seas, the Mediterranean and the Red Sea. According to the historian Herodotus, it was partially executed by Pharaoh Necho, or Nechao, about 600 years before Christ; but it is not known who completed it. It began at about a mile and a half north of Suez and struck in a northwesterly direction, availing itself of a series of natural hollows to Bubastis, on the Pelusiac, or eastern branch of the Nile. Its length was 92 miles, 60 of which were excavated by human hands; its width was from 108 to 165 feet and its depth 15 feet. After a while it became silted up with sand, was restored by Trajan; was again choked and rendered useless; was reopened after the Saracenic conquest of Egypt by Amrou, the Arab general, and named the “Canal of the Prince of the Faithful”; and finally filled with the never-resting sands in AD 767. Upwards of ten centuries passed before any attempt was made to renew a communication between the two seas. Then the idea occurred to the ingenious mind of Bonaparte; but as his engineers erroneously reported that there was a difference of level between the Mediterranean and the Red Sea to the extent of thirty feet, he suffered it to drop. In 1847 a scientific commission appointed by England, France, and Austria, ascertained that the two seas had exactly the same mean level. The only noticeable difference was that at the one end there is a tide of six feet six inches and only one foot six inches at the other. Mr. Robert Stephenson, the great English engineer, came to a similar result in 1853 but declared that no navigable canal could be constructed; and he then laid down the existing railroad between Cairo and Suez as a substitute.

There arose, however, at this time a Frenchman, with all the élan and ingenuity of his countrymen and as indomitable perseverance peculiarly his own, who came to a different conclusion. Having some influence at the Egyptian court, he obtained a concession in 1854 from Said Pasha, the viceroy of Egypt, for the making of a canal across the Isthmus of Suez. The sultan’s assent was less easily procured owing to the jealousy which has arisen between English and French into sects, and it was not until 1858 that M. Ferdinand de Lesseps found himself in a position to appeal to the public for support. A company was then formed with a capital of £8,000,000. In 1859 the work was begun, and by December 1864 the freshwater canal requested for the supply of the laborers on the ship canal was completed. All, however, did not go on smoothly. Difficulties arose between Ismail Pashma (Said Sasha’s successor) respecting the concessions granted to the company. The dispute was referred to the emperor of the French as arbitrator, who decided that the company should give up some important privileges and receive in line thereof a total sum of £4,000,000, with a strip of land about forty-eight yards wide on each side of the canal. The ship canal was then proceeded with, a variety of ingenious machinery being invented by the French engineers to meet the exigencies of their novel and magnificent enterprise. In 1867 an additional capital of £4,000,000 was raised and on the November 17, 1869, it was formally opened for navigation in the presence of a host of illustrious personages representing every European state. The cost of the canal was about twenty million pounds. The total length is about ninety miles from head to head. The width of the water surface was at first 150 to 300 feet, the width of the bottom 72 feet, and the minimum depth 26 feet. It begins at Port Said, on the Mediterranean, where an artificial harbor has been constructed; proceeds to Kantara; traverses the Lake Timsah; thence to Serapeum; passes through the Bitter Lakes and terminates at Suez.

At the end of a dozen years, the traffic had increased so enormously that a second canal began to be talked about, and in 1886 the task of widening and also deepening the existing canal was commenced. By 1896 the canal had been deepened to 28 feet and widened between Port Said and the Bitter Lakes to 144 feet and from the Bitter Lakes to Suez to 213 feet.

Since 1886 the time of making the transit through the canal has been greatly accelerated. In that year a vessel took on an average 36 hours to get through; now the average time of passage does not exceed 18 hours. Moreover, since March 1887, the electric light has been used to light the way during the night.

The construction of the Suez Canal has called into existence two new towns, namely, Port Said which now has a population of about 14,000, and Ismailia. Suez, which is an older town, has largely increased its population, which now numbers about 20,000. About 5,000 vessels pass through the canal every year, and the canal stock, it is said pays its shareholders a good annual dividend.

At 6:30 p.m. I left Ismailia by train for Cairo, the capital of Egypt, distant 156½ kilometers, or about 97 miles, from Ismailia. It being night, I was unable to make but a few observations in regard to the country which we passed through; but I noticed that the first part of the route lay through a barren desert land though following the banks of the freshwater canal while the latter part took us through a thickly populated and fertile country—a part of the great Nile Delta, part of which I afterwards learned to be the land of Goshen of Bible fame. Zagazig and Benha were the two most important intermediate stations. I also noticed the desert village of Tel-el-Kebir, where the English under General Sir Garnet gained a decided victory over Egyptian rebels in battle on Friday, July 7, 1882. Soon afterwards Cairo was taken by the British, who have since watched over their Egyptian interests with a jealous eye, constantly fearing the ascendancy of French influence, which perhaps is not without cause.

On my arrival at Cairo at 10:30 p.m., I put up at the Khedivial Hotel, where I appeared to be the only European or American guest, the tourist season being over for this year.

“Jenson’s Travels,” June 9, 1896 [6]

Ismailia, Egypt

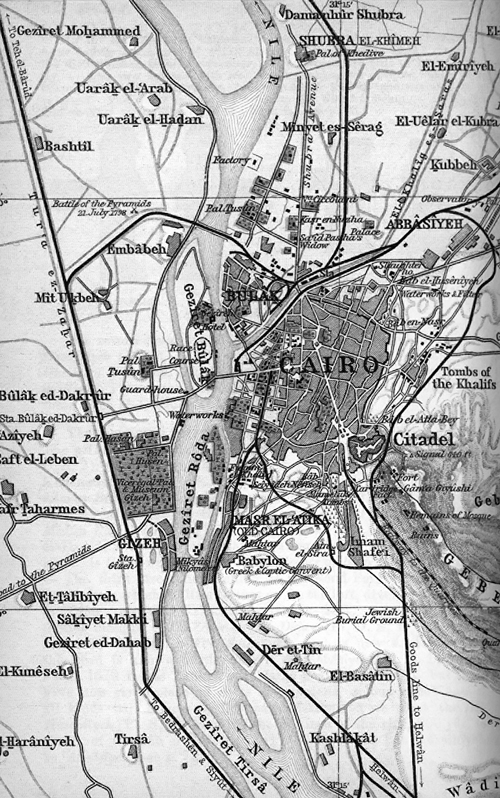

(Map of Cairo from 1894 Baedeker)

After enjoying a good night’s rest at the Khedivial Hotel at Cairo, Egypt, I arose early on the morning of June 8, 1896, and hired a man with a gray donkey to take me through the city and out to the great pyramids beyond the Nile. I left the hotel at 7:30 a.m. being mounted as gracefully as possible on the donkey, whose neck was richly decorated with Egyptian brass jewelry; but whose constant abuse of his braying powers made me perfectly disgusted with him before the day was over. His master who ran behind me and the donkey could talk a little broken English, so I dispensed with the additional luxury of a special guide, though such a one, who styled himself the guide of Cairo, offered his services for six shillings a day provided I hired a carriage for both of us which would cost me sixteen shillings extra. Believing in economy I decided to get along with Said [Sayyid?] Mohammed and his donkey for four shillings per day.

As we rode through the streets of Cairo, I saw much to admire and many things to disgust me. Most every visitor to the capital of Egypt, I believe, is at first bewildered, same as I was, by the first novel scenes which crowd upon him; and sometime necessarily elapses before he is able to disentangle his confused impressions and realize each feature of the marvelous picture. After a while one begins to understand that he is indeed in a purely Oriental city. As he examines its bazaars and passes through its streets, he seems carried back to the days of antiquity. There are a few straight and regular streets in Cairo, but most of the thoroughfares [7] are so narrow as scarcely to admit of two camels passing abreast; some of its bazaars glow with the richest productions of the looms of the East; its mosques and minarets are apparently innumerable; and its fountains fill the air with an enduring freshness. Many of the richly carpeted shops are enclosed in front by a divan, and in the midst sits a venerable Turk or a wealthy Arab, smoking his pipe—often a splendid narghileh of gold and silver—and surveying with complacent gaze his costly wares, which embraces jewelry from Paris, chibougues from Constantinople, tobacco from Latakia, dainty muslins from India, keen bright swords of “Damascus steel,” and rustling silks from the land of the Celestials. Meanwhile, the ways are thronged in many parts, and it is often with difficulty that the pedestrian escapes a rude jostle from the donkeys which pass him every moment laden with sand, flour, water, etc., or occasionally with a happier burden in the person of some Egyptian beauty of the harem closely veiled and attended by watchful guards. With my best endeavors to make it otherwise, the braying donkey that I rode ran headlong against several persons and also against other donkeys, though his master claimed that his donkey ranked very high in the scale of good behavior as compared with Cairo donkeys in general.

Cairo lies in latitude 30°2΄ N and longitude 31°16΄ E on a sandy level between the right bank of the Nile and the range of the Mokattam Hills. It was founded eastward of what is now called old Cairo by Tulun, a Muslim governor of Egypt in AD 868; but was removed still further eastward, to its present site, by the Fatimite khalif El Moez in AD 923. It remained the capital of the Fatimite rulers until 1171, when the famous Saladin usurped the throne. In 1220 it was unsuccessfully besieged by the Crusaders. In 1250 Musa-el-Ashraf was deposed by the Mamelukes, who retained possession of the city until 1517, when it was stormed and captured by Sultan Selim. Though it has lost most of its original importance, it is still a prosperous city with a population of about 250,000, mostly Mohammedans. It may be considered as the great center of learning of the Eastern world, its celebrated university being presided over by men of acknowledged erudition and annually attended by some two thousand students.

One of the most remarkable edifices in Cairo is the Cathedral, which dominates over the whole town from its elevated position on a bold ridge of sandstone. [8] Its walls are of great solidity and, in some places, one hundred feet in height. It was within these walls that the massacre of Mamelukes took place March 1, 1811; and its battlements were crowned by Napoleon’s victorious standards in 1798. The Cathedral walls were enlarged and strengthened by Mehemet Ali, who resided here during the greater part of his reign. The prospect it commands is of a very extensive and impressive character, including not only the city of Cairo with its carved domes and fantastic minarets, but the sequestered valley of the Nile with its tombs of the Mameluke sultans; the rich, deep verdure of the distant delta; the sharp, clear outline of the mysterious pyramids; the yellow frontier-belt of the desert; the meanderings of the tranquil Nile; and everywhere a soil that has been swept by successive waves of revolution from the days of Menes and Rameses to those of Napoleon Bonaparte. When I stood on the top of the high wall by the great mosque which stands in the center of the Cathedral and looked out upon the valley of the Nile, I certainly thought that my eyes had never rested upon a more picturesque or interesting landscape.

The Cairene minarets are justly eulogized by travelers as the most beautiful of any in the East. They rank as exquisite creatures of the strange, dreamy Arabian genius, towering to an extraordinary height, built of courses of red and white stone, and ornamented with balconies from which the muezzins announce the hour of prayer. Of these, the most ancient adjoins the great mosque of the Sultan Tulun, built in AD 879, soon after the foundation of the city. The others belong to the magnificent mosque of the Sultan Hassan, which is situated in the palace of the Roumayli, near the Cathedral, and was completed about AD 1362.

After passing through several streets, viewing a number of palaces and parks, my Arabian guide, his donkey, and I soon found ourselves crossing the great bridge of Kasr-el-Nil spanning the Nile. It is six hundred feet long, built on six spans; and at either extremity, facing the shore, stand two colossal lions of bronze perched high upon stately pedestals. The traffic across the bridge is immense at all hours of the day; and it was here that my donkey made himself particularly conspicuous by frequently coming into collisions with the long caravans of camels, the peculiar-shaped vehicles, the herds of cattle and flocks of sheep, not to speak of other braying asses, all of which moved across the great bridge both ways in two continuous “streams.” I never before in my life saw such a lot of people traveling on donkeys as I witnessed here. And such it seems was also the impression of Howard Hopley, the author of a work entitled “Under Egyptian Palms,” who writes:

“Quite an institution in Cairo are the donkeys and their drivers. But you must not suppose that the Cairene ass is as patient, depressed, and dismal looking a quadruped as his European congener. He has a smart ring of pride about him, pricks up his ears with an air of intelligence, indulges in impetuous fits, but is also given to prolonged pauses of meditation. In mere personal appearance he is more of ‘a swell’ than his northern brother. His owner shaves him upon the back like a poodle dog. He carries a high and hungry saddle, covered with scarlet leather and tinsel trappings, so that, on the whole, he can sniff up the wind proudly besides the statelier camel or run unabashed in presence of his high-born kinsman the horse. But even a Cairene donkey is not without his failing; he will lie down at inconvenient times, kick up his heels, and growl in the dust, and this is the more strange since he appears thoroughly aware of the folly of such an escapade. He invariably arises with a guilty look, perfectly conscious that he is about to receive a beating; and yet the temptation to do evil is irresistible.

“Not less original than the animal is the animal’s owner. Now in Cairo, every little proprietor keeps a donkey, which is as much a sign of respectability in the East as payment of rates taxes in the West. The proprietor is not always the driver, but whether he owns the beast or not, the driver is as fond of him as the Bedouin is of his camel; he runs beside him, stimulates him with kind words, and takes care that he is comfortably fed and housed. His own dress is light and airy; a scarlet tarboosh or white turban of few folds for the head, a blue cotton tunic reaching barely to the knees, and a long scarf for the waist completes his wearing apparel. He is as eager for a customer as any London cabman; and your appearance on the steps of your hotel is the signal for a general rush towards you of donkey drivers and donkeys.” [9]

After crossing the Nile, we were in the suburban town of Giza, and the road now turns to the left and follows the bank of the river for two or three miles until the museum and zoological gardens are passed; then it turns to the right and runs straight to the pyramids about seven miles from the river and the desert which are reached after the desert which are reached after traveling about ten miles from Cairo. The road is raised several feet above the general level, is well macadamized, and is lined on both sides with regular rows of sycamore trees. There are five miles on the road where wheels of various models are used to raise the water that is utilized for irrigation purposes and for sprinkling the road. There are also several native mud villages on the way out, all of which are built very compact and on raised ground. Then there were several ponds containing dirty water in which some of the natives were washing clothes and others plunging in headlong trying to catch the few remaining fish which would otherwise soon die a natural death by the evaporation of the pools of water. The making of bricks by the natives as in the days of the Israelites, the cutting of grass, the cultivation of the soil, the methods of irrigation, and various other kinds of employment on which the natives were engaged constituted the most interesting features of sightseeing on our ride from Cairo to the pyramids. At length we arrived in front of the hotel lying adjacent to the three Pyramids of Giza, where I was surrounded by a herd of Arabs, who wanted to act as guides, aids, water carriers, and I don’t know what else; they soon began to quarrel among themselves and with me because I would only engage one man when they insisted that I needed at least a dozen. It seems strange that I got along at all, as I was the only white man among that motley crowd of semicivilized beggars and fleecers.

Their custom is to get as much as they possibly can from every stranger; and as there are only a few visitors now that the tourist season was over, they are all on hand to double up on the few stragglers who come along like myself; but as I had posted myself in regard to the proper fees and lawful charges before leaving Cairo, they found me an awful stubborn customer to deal with; and when they learned that they could not fleece me at will for large fees, they were satisfied with the smallest compensation possible; so, after all, I got through reasonably cheap notwithstanding their number. And this was partly due to one of their number—an old man who styled himself Dr. Mahmut, and who pretended to be my friend. This he did undoubtedly for selfish motives, as he expected me to pay for his friendship, and in this he was not disappointed. Finding out that I understood him, he really did both befriend and defend me against the others; and when I at times looked at him as if I doubted his words, he pointed toward heaven and said that Allah should witness that he was an honest man and told me the truth; and I believe he did. He and two young men accompanied me all through the inner passages and chambers of the great pyramid, and afterwards climbed with me to the top; then I rode his camel down to the Sphinx and back again; and he also got me both milk and water to drink at reasonable prices. The day was hot, and the exertions of climbing such that I was sore for a long time afterwards. I climbed to the top and descended, and also passed through the inside without the least assistance from any one. This I did to prove the falsity of what I was told at the hotel before I started out in the morning that it was absolutely impossible for any white man to climb to the top of the Great Pyramid without assistance; and the steep inside passages, I was told, were still harder to ascend and descend. But through I found it quite possible, I shall never want to repeat the exercise. I went through the inside first and afterwards climbed to the top; but before reaching it I found myself dragging myself slowly upwards on all fours, drawing on all the physical strength I possessed. I would undoubtedly have fainted with thirst and fatigue had not a young Arab appeared on the scene with a calabash of water. Before I left the Oroya, a doctor and fellow passenger warned me repeatedly against drinking water in Egypt of any kind, on pains of being stricken with cholera at once; but the combined efforts or advices of all the doctors in the world could not have induced me to refuse taking a drink of water while on the top of the Great Pyramid in my exhausted condition.

The view from the top of the Great Pyramid is grand beyond description. It includes the Nile Valley for many miles up the river, the Delta in part, the city of Cairo, the site of old Memphis with a number of pyramids nearby, and the great Libyan Desert, on the edge of which all the pyramids of Egypt are erected. It is asserted by some historians, on pretty reliable authority, that 100,000 men were employed for twenty years, building the pyramid of Cheops, the one I climbed and the one generally visited by tourists. This is supposed to be 4,000 years ago. The original height of that great pile of rocks was 480 feet 9 inches, and its base 764 feet square. Its slope was 51°50΄, but its eternal effects were much injured by the spoliation of the exterior blocks for the erection of Cairo, and several feet of the original top is missing entirely.

As nearly every reader of the News has read works on the pyramids of Egypt, I will not attempt to describe them here. My personal opinions and impressions I will also reserve till some future day. I know that I was very, very tired when I returned to Cairo in the evening and felt truly thankful for the preserving care of the Lord throughout the dangers of the day and that my physical strength held out to the end.

Cairo, Egypt: Handbook for Travelers (London: Karl Baedeker, 1895)

Cairo, Egypt: Handbook for Travelers (London: Karl Baedeker, 1895)

“Jenson’s Travels,” June 10, 1896 [10]

Port Said, Egypt, Africa

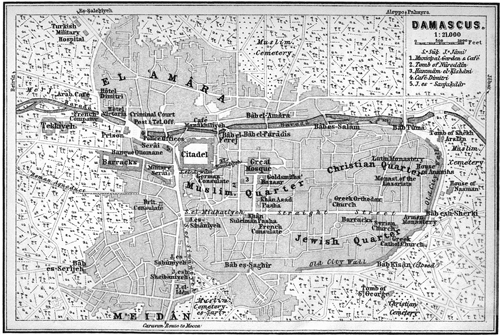

After spending a second night in Cairo, Egypt, I arose early in the morning of June 9, 1896, and took a long walk through the city without guide or donkey. Passing through Rue du Muski, one of the principal streets of the city, I found myself at the eastern boundary and at the foot of a spur of the Mokattam Hills, which I crossed, and then descended to a veritable city of the dead known as the “graves of the Khalifs.” Here lie the nobility of Egypt for many generations, many of them in costly and ornamental buildings which are crowned by domes in regular mosque style. I was permitted to enter the finest building I could see, after the doorkeeper had carefully tied a pair of sandals on my feet. The Arab attendant took great pains to tell me all about it in a language of which I knew not a single sentence; but I was led to understand that I was in the open tomb of one of the late Khedives of Egypt. From the graves of the Khalifs, I walked to the great citadel, where I fell in conversation with some English soldiers, one of whom (William Cox) said he was related to Thomas C. Patten, of Salt Lake City. He desired very much to go to Utah himself and hoped to have the privilege of doing so after he had served his term as a soldier. Two of the boys had recently died with the cholera, and I was shown the cholera camp on a high roof within the enclosures of the citadel. At present, however, it is without tenants, and I was told that the two deaths were caused by the unwise conduct of the soldiers themselves, who had mixed with the natives to their unhealthy quarters and had drank bad whisky with them.

From the citadel I returned to the hotel by way of the street called Boulevard Mohammed Ali, paid my hotel bill, drove to the station in a carriage, and left Cairo by rail at 11:15 a.m. Arriving at Ismailia, I changed cars for Port Said, distant fifty miles from Ismailia by rail, where I arrived at 7:30 p.m., and put up at a hotel. At Ismailia a fellow passenger—a German—voluntarily took my part against an impudent Arab who insisted on acting as my guide, though I had told him repeatedly that I did not want him. My German friend, whose name was Constantin Fix, seeing that the fellow tried to impose upon me, arose, fired with indignation, and deliberately knocked the Arab down. The station police were soon on the spot; but my friend, who talked good Arabic, was able to give satisfactory explanation, and the impudent native scampered off with a sore head instead of the money, which he wanted to extort from me. Port Said is a new town which, as I have stated in a former letter, and had no existence before the building of the Suez ship canal. It has regular streets, one small artificial park, some respectable and good-sized buildings, but otherwise no particular attractions. And it is only important as the Mediterranean port of the Suez Canal, where all canal dues are also paid by southbound ships. A fine statue of M. Ferdinand de Lesseps, to whose ingenuity the town owes its existence, adorns the public park. Port Said gets its supply of fresh water from the Nile through a previously mentioned canal.

Everything alive that I have seen in Egypt relies upon the Nile for its very existence. It certainly is one of the most remarkable rivers of the world, and as the memorials of antiquity in the shape of the tombs, temples, and monuments of old Egypt lie on its banks, a short sketch of that historical river may not prove uninteresting to the readers of the News. Miss Harriet Martineau, who recently wrote a book on Egypt, remarks:

“Everything in Egypt, including life itself, and all that life includes, depends on the incessant struggle which the great river maintains against the forces of the desert. The world has witnessed many conflicts; but no other so unresting, so protracted, and so sublime as the struggle of these two gigantic powers, the Nile and the desert. The Nile, ever young because perpetually renewing its youth, seems to the inexperienced eye to have no chance with its stripling force—a David against a Goliath—against the desert, whose might has never relaxed, from the earliest days till now, but the Goliath has not conquered it. Now and then he has prevailed for a season, and the tremblers whose destiny hung on the event have cried out that all was over; but he has once more been driven back, and Nilus has risen up again, to do what we see him doing in the sculptures—bind up his water plants about the throne of Egypt. From the beginning the people of Egypt have had everything to hope from the river, nothing from the desert; much to fear from the desert, and little from the river. What their fear may reasonably be, any one may conjecture who has looked upon a hillocky expanse of sand, where the little jerboa burrows, and the hyena prowls at night. Under these hillocks lie temples and palaces, and under the level sands a whole city. The enemy has come in from behind and stifled and buried it. What is the hope of the people from the river anyone may witness who, at the regular season, sees the people grouped on the eminences, watching the advancing waters, and listening for the voice of the crier, or the boom of the cannon which is to tell the prospect or event of the inundation of the year. The Nile was naturally deified by the old inhabitants. It was a god to the mass; and at least one of the manifestations of diety to the priestly order. As it was the immediate cause of all they had, and all they hoped for—the creative power regularly at work before their eyes, usually conquering, though occasionally checked—it was to them the good power; and the desert became the evil one. Hence originated a main part of their faith, embodied in the allegory of the burial of Osiris in the sacred stream, whence he arose once a year to scatter blessings over the earth.” [11]

The sources of the Nile, which is so intimately bound up with the fortunes and creed of a great people, were long involved in mystery. The sources of the Blue Nile was discovered by James Bruce in 1770; but that of the more important White Nile, which is indeed the true Nile, remained enshrouded in mystery until quite recently, when its source was discovered in or adjacent to the great lake now called Victoria in central Africa by the late Dr. Livingston and others. The river flows out of said lake on the north, just beyond the equator in a channel 150 yards wide, and pouring over a mass of igneous rocks, forms the Ripon Falls, twelve feet high in latitude 0º20´ N and longitude 33º30´ E. Proceeding in a northwesterly direction, it forms the Karuma and the Murchison Falls and joins the Albert Nile. Emerging from this second reservoir, the White Nile, or Bahr-el-Abiad of the Arabs, still keeps to the northwest, and through a country recently opened up by the late General Gordon and his lieutenants goes onward to Gondokoro, the great depot of the ivory dealers, 1,900 feet above the sea. Over a gently undulating plain with many windings but no great descent, it strikes to the northwest, and afterwards to the northeast for nearly 500 miles, receiving in latitude 9º15´ N its first great affluent, the Bahr el Ghazal, or Gazelle River, a slow and shallow stream from the west. Taking an easterly direction for eighty miles, and curving southward for thirty miles, it is augmented by the waters of the Giraffe and the Sobat; after which it takes a northly course, with a full and tranquil current, and a breadth varying from 1,700 to 3,600 feet, for nearly 480 miles. Thus it arrives at Khartoum, the capital of Nubia, in latitude 15º37´ N. Here it is that it receives the river which for generations was supposed to be the Nile—the river which the adventurous Bruce traced to its fountains—the Blue Nile, or Bahr el Azraq. It is formed by the junction of the Abay (which rises in Abyssinia, fifty miles from Lake Tana and 8,700 feet above the sea) and the Blue River, which has its sources in the southern highlands, and is fed by the Dinder and the Shimla.

At Khartoum the Blue Nile is 708 yards wide and the White Nile only 483 yards; but the latter is much deeper, and its flow of water more continuous. Flowing north for sixty miles across wide pasture plains and past Halfiyeh and ancient Meroe, the Nile arrives at its first cataract, or rather rapid, which is the seventh counting from the river’s mouth. Rolling onward, it passes Shendi and receives at Ed Damer (in latitude 17º45´ N) the Atbara, or Tekeze, or (as it is often called in allusion to its muddy waters) the Bahr el-Aswad, or Black River.

From this point the great river traverses for 120 miles the rich, well-cultivated, and numerously inhabited country of the Berbers, to enter on a widely different region—a wilderness of sand, barren and desolate, where the ruins of antiquity lie overwhelmed by the sandstorms of centuries. Below the island of Mograt (in latitude 18º N) it bends sharply to the southwestward, three cataracts or rapids marking this part of its course. It then takes a northwesterly direction, crosses the desert at Behionda, forms another cataract, diverges to the northeast, and flows through the rapids of Wadi Halfa, passes, in a much narrower valley, the ruins of Abu Simbel, El Derr, Qirshah, Garf Husein, Dendour, and Kalabsha, and at Aswan (anciently Syene) in latitude 24º5´23˝ N, descends into upper Egypt by its largest cataract, which is the seventh from its source, or the first from its mouth. All these cataracts are really rapids which almost disappear when the Nile is at its height during the period of the annual inundation. They are caused by the encroachment of the rocks upon the river-channel, which, dividing into several small streams, pours its waters through the craggy defiles with considerable fury.

The Nile in its course through Egypt passes successively the quarries of Gebel el Silsila on the east; Edfu and Esna on the west; the wonderful palace temples and memorials of Thebes, with Luxor and Karnak, on the east, and Deir el Medina Habu on the west; then Girga and Siont on the west; and the tombs of Beni Hasan on the east. In due time it reaches the ruins of Memphis and the Pyramids, all on the west bank, and leaving Cairo with its mosques and minarets, on the east, spreads out into the numerous arms which form the celebrated region of the Delta. From Assouan to the sea, its average fall is only two inches in 1,800 yards, and its average velocity does not exceed three miles an hour. Its direction is almost due north, with occasional durations to the east and northwest. The triangular area, which derives its name from a Greek letter, begins at a point about 120 miles from the two chief mouths of the river, the Rosetta and Damietta mouth and stretches along the Mediterranean coast in a network of streams and islands for about 150 miles.

The rise of the Nile is due to the periodical rains of eastern Abyssinia and the countries farther south, and on their greater or lesser quantity depends on the height of the inundation. This height is carefully noted, as the extent of land subjected to irrigation, and the length of the time during which it will remain under water, are regulated by it; and hence the occurrence of a good or bad harvest may be predicted with certainty. The ordinary rise at Cairo is from 23 to 25 feet; less is insufficient, and more is dangerous, frequently overwhelming whole villages. A rise of only 18 or 20 feet means famine, and a flood of the height of 30 means ruin.

The lands, thus strangely irrigated, will yield annually three crops; first being sown with wheat or barley, a second time, after the spring equinox, with cotton, millet, indigo, or some similar produce; and thirdly, about the summer solstice with millet and maize. The river begins to rise about the end of June and attains its maximum between September 20 and 30. At this time the country wears a very singular aspect. “On the elevated bank you stand, as it were between two seas,” writes Eliot Warburton in his book entitled The Crescent and the Cross. [12] “On one side rolls a swollen turbid flood of a blood-red hue; on the other lies an expanse of seemingly stagnant water, extending to the desert boundary of the valley; the isolated villages, circled with groves of palm, being scattered over it like floating islands, and the gise or dike, affording the sole circuitous intercommunication between them. When the waters subside (a process which is very perceptible about November 10) the valley is suddenly covered with a mantle of the richest green, and the face of the land smiles in the traveler’s eyes with all the splendor of a new-created country.”

The water of the Nile is exceedingly wholesome, and in its most turbid state always capable of filtration. Between the highest and the lowest periods of the yearly flood it is not less remarkable for its purity than for its transparency. The crocodile and the hippopotamus abound, but the former is now very seldom met with below 270 north or the latter further south than the second cataract. Fifty-two species of fish are described as belonging to the river.

The word Nilus is probably of Lemitic origin; and like the Hebrew Lihhor, the Egyptian Cheml, and the Greek melas, may have referred to the dark hue of its waves. The natives call it “p-iero,” or the “river of rivers,” as if no other could claim comparison with it in grandeur, beauty, or fertility.

The Nile typified to the Egyptians the river of death, across whose silent wave the dead were ferried to their resting places on the border of the desert, attended by the conductor of souls, the god Anubis. “How many of our own ideas of the other world may have been borrowed from the Nilotic worship of the Egyptians,” wrote Mr. Adams in his book Egypt Past and Present. “When we speak of the darkling stream which separates time from eternity, we are employing an Egyptian image; and unknown to ourselves perhaps, referring to the mysterious river of a mysterious land—the great and glorious Nile.”