New Zealand, October 1895–January 1896

Reid L. Neilson and Riley M. Moffat, eds., Tales from the World Tour: The 1895–1897 Travel Writings of Mormon Historian Andrew Jenson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2012), 163–220.

As soon as we emerged from the timber they commenced to call out “haere mai, haere mai” (“come, come”), and after we had forded the river they strung themselves out in a long line in front of the meetinghouse to receive our undivided greeting which meant both shaking hands and rubbing noses. This certainly was a new and novel experience for me. I had learned a great number of new departures and native ways during my sojourn among the Hawaiians, Fijians, Tongans, and Samoans; but none of these indulge in that particular mode of greeting which the Maoris call hongi (nose rubbing). Well, I made a failure of the first attempt. Elder Gardner, evidently forgetting that I was a new hand, started out in such good earnest for himself that he was halfway down the line before I had unsaddled my horse and was ready to commence. I was just getting my nose ready to start in when my courage failed me. All at once I seemed to forget the verbal instructions I had received about this same hongi business. Was I to press with the top of the nose, or the left or right side, or all around? I had forgotten all.

—Andrew Jenson [1]

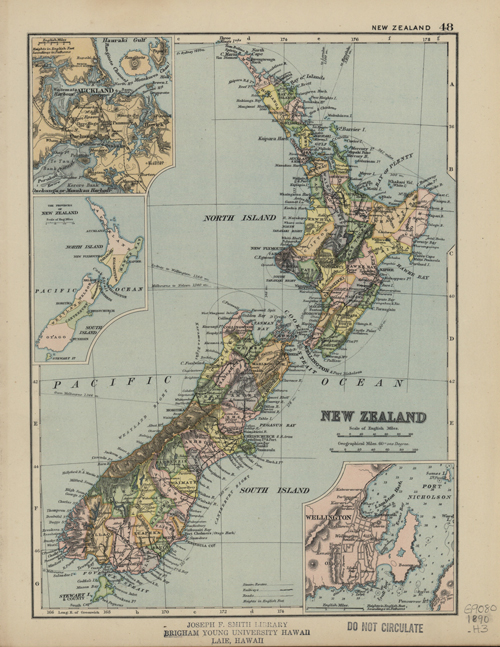

New Zealand, Harmsworth Atlas and Gasetteer, (London, 1890), 48

New Zealand, Harmsworth Atlas and Gasetteer, (London, 1890), 48

“Jenson’s Travels,” October 17, 1895 [2]

Ruatangata, near Whangarei, New Zealand

Friday, October 11. After attending to some necessary business in connection with the transportation of elders, I commenced my historical labors in Auckland, New Zealand, pertaining to the Australasian Mission, assisted by Elder John Johnson, who is the secretary of the mission. He commenced to act in that capacity a few months ago, when Elder Ben Goddard, the former secretary, returned home from a long and faithful mission.

Saturday, October 12. I continued my labors of the day previous and was introduced to Elder Charles Hardy, president of the scattered fragments of what was once the Auckland Branch. Brother Hardy embraced the gospel in 1854, in Australia, and, together with other Saints, sailed from the province of Victoria, April 27, 1855, on the brig Targuena bound for America. But the ship sprang a leak and only brought her passengers to Honolulu, Hawaii, where she was declared unfit for further sea service; and the emigrants had to pursue their way from there to America as best they could. Brother Hardy, who was then an unmarried man, succeeded in reaching San Bernardino, California, where he lived for several years; but instead of going to Utah when the San Bernardino Saints migrated thither, Brother Hardy went to England, where he took to himself a wife, and in due course of time wended his way to New Zealand, where he has raised quite a family. After the elapse of many years, he saw a Latter-day Saint meeting advertised in an Auckland paper, which caused the old spirit of Mormonism to come upon him anew, and he made himself known to the elders and was in due course of time baptized by Elder John P. Sorenson, of Salt Lake City. Since then he has remained a faithful member of the Church and has often assisted the mission in a material way, being blessed with some of this world’s goods.

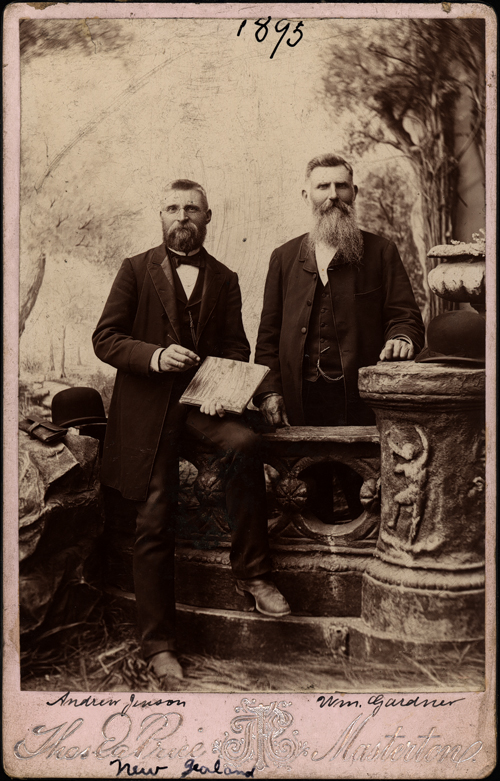

Thursday, October 13. Having occasion to seek retirement while consulting about matters of importance, Elder William Gardner and myself (Photo of Jenson and Gardner) started out on an early-morning walk, in the course of which we ascended the famous Mount Eden, an extinct volcano situated about three miles inland from the business part of Auckland. The mount, or hill, is about 640 feet high, and the view from its summit is most extensive and magnificent. All around are seen the craters of extinct volcanoes, a careful count footing up the remarkable total of 63 within a radius of five miles, showing what a warm corner of the earth this must have been at some prehistoric date. Auckland, with its beautiful suburbs and splendid harbor, lies spread out at one’s feet, and beyond, the Waitakere Ranges on one side and the Coromandels on the other, while the extinct volcano, Rangitoto, with its triple cone, dominates the landscape straight ahead. Mount Eden is also interesting in other points. The crater remains a perfect inverted cone, forming a vast amphitheatre, which is sometimes used for mass meetings of the populace. In older Maori days, the hill was a pa, or stronghold, and the terraced fortifications are plainly visible on its sides.

Auckland, containing a population of about 51,000, including suburbs, is situated on the shores of Waitemata Harbor, a beautiful stretch of water branching from the Hauraki Gulf. The ground upon which the city is built is rolling, and some of the hills are quite steep; but as the streets, instead of crossing each other at right angles, have been laid out so as to conform to the hill slopes, the streets are quite nicely graded. Auckland is the chief port for the trade with the South Pacific Islands. The city was founded by Governor William Hobson in 1840, and it remained the capital of New Zealand till 1864, when the seat of government was removed to Wellington.

Andrew Jenson and Australasian Mission president William Gardner. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

Andrew Jenson and Australasian Mission president William Gardner. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

Since October 27, 1854, Auckland has been known to Latter-day Saint history. On that day Elders Augustus Farnham and William Cook landed in Auckland from Australia as messengers of truth and salvation to the people of New Zealand, which at that time contained a population of only about 30,000 whites. Auckland only had two or three thousand people in 1864. The elders, on arriving, found all the houses of accommodation in the city full in consequence of an influx of emigrants; consequently they had to hire unfurnished apartments to live in. After first visiting the respective ministers or preachers of different denominations, they gave notice by advertisement, of a series of meetings which they intended to hold at the Venetian cottage (formerly the residence of General Pitt). Their meetings were well attended, and there was considerable inquiry on the part of the people, many of whom purchased books treating upon the principles of the gospel. After holding several meetings, the two elders proceeded to Onehunga, a small town situated on the Manukau Harbor, on the west coast, seven miles from Auckland, intending to hold meetings there; but the early departure of the steamer on which they were to sail for Wellington prevented them from preaching there. The first branch of the Church in New Zealand was raised up by William Cook, after the return to Australia of Augustus Farnham early in 1855, at Karori, near Wellington. I have been unable to learn of any other organization of the Church in New Zealand till 1867, when Elder Carl C. Asmussen, who had recently embraced the fulness of the gospel in England, baptized six persons at Kaiapoi, near Christ Church, on the South Island, and ordained William Burnett an elder; but no branch was organized, though meetings were held every Sunday for some time, and others baptized. In 1870, Robert Beauchamp revived the work near Wellington, and in April 1870 a branch, consisting of eighteen members, is reported to exist at Karori, near Wellington, where the former branch of 1855 had been raised up by Elder Cook. On January 8, 1871, a conference was held at Karori at which thirty-one adult members of the Church in New Zealand were represented, including four elders. In the latter part of December 1871, Elder Henry Dryden and Brother Joseph Fawcett, with their respective families (eleven souls altogether), sailed from New Zealand per steamer Nevada. This little company, which seems to be the first Latter-day Saints to immigrate direct to Utah from New Zealand, arrived in Salt Lake City February 10, 1872. On December 14, 1875, Elders Frederick Hurst, Charles Hurst, John T. Rich, and William McLachlan landed at Auckland as missionaries from Utah. The arrival of the four elders and that of Elder Thomas Steed, who was sent over from Australia about the same time, may be termed the commencement of perpetual missionary work in New Zealand, though I believe even after that the field was without representation from Zion once for a year or more. But though elders landed at and took their departure from Auckland, no successful missionary work was done in that city till after the arrival of Elder John P. Sorensen of Salt Lake City on December 16, 1879. He commenced to preach in Auckland (at the Odd Fellows Hall) January 11, 1880, and baptized his first converts in that city February 29, 1880. A number of others followed, and on June 6, 1880, he organized a branch of the Church in Auckland, with Elder William John McDonald (the first man baptized) as president. For many years the Auckland Branch was strong and lively, though contentions occasionally arose among some of the members. But in due course of time the “cream of the branch” immigrated to Zion; others apostatized, and there are at present only a few scattered members of the organization left. Among those are Sister Harding and family, with whom we held a little meeting on Sunday evening, October 13. If the branch is not revived in the near future, it will not be the fault of Elders Johnson and Browning, who are laboring with a zeal which their opponents say is worthy of a better cause, to establish the cause of Zion in the beautiful city of Auckland and vicinity.

Monday, October 14. In perusing the records of the Australasian Mission, I found that no accounts of the labors of the early missionaries have been preserved; at least, they are not at the headquarters of the mission at the present time. The record, which is known as the mission history, has been well kept since that date. Nearly two hundred missionaries from Zion have landed on the shores of New Zealand since 1881, of whom upwards of sixty are pleading the cause of truth here at the present time, the bigger half among the Maori people.

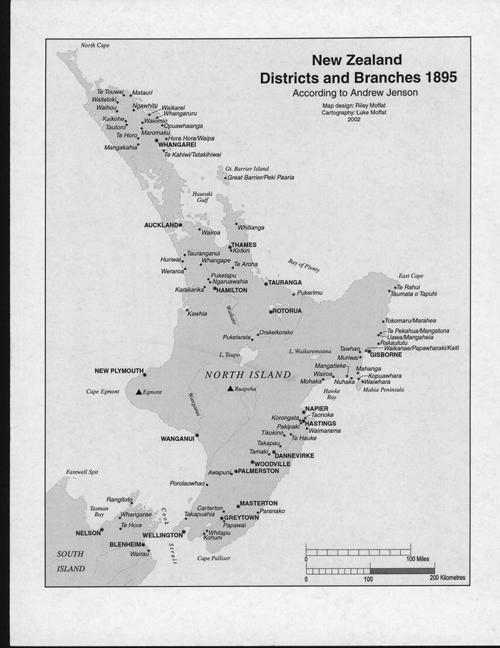

The Australasian Mission embraces New Zealand, Australia, and Tasmania. The New Zealand part of the mission is divided into fifteen districts, of which twelve are Maori and three are European districts, though some European missionary work is also carried on in some of the Maori districts. The names of the districts commencing with the north end of the North Island and finishing with the south end of South Island are as follows: Bay of Islands, Whangarei, Auckland, Waikato, Hauraki, Tauranga, Waiapu, Poverty Bay (or Turanganui), Mahia, Hawke’s Bay, Manawatu, Wairarapa, Wairau, Canterbury, and Otago. (Map of New Zealand branches and membership list) The first twelve embrace the North and the three last the South Island. The Auckland, Canterbury, and Otago are the three European districts. According to the statistical report of December 1894, the Australasian Mission, exclusive of elders from Zion, contained 139 elders, 156 priests, 109 teachers, 153 deacons, and 1,908 lay members, thus making 2,465 the total of officers and members. Adding 933 under eight years of age in the families of Saints, the grand total of souls foots up to 3,398 souls. Only 110 of these are in Australia and Tasmania; the rest are in the New Zealand districts.

Branches in New Zealand described by Andrew Jenson during his tour of 1895

Branches in New Zealand described by Andrew Jenson during his tour of 1895

The colony of New Zealand, which is a British possession, consists of three main islands with several smaller groups of islands lying at some distance from the principal group. The main islands, known as the North, the South (the middle), and Stewart islands, have a coastline 4,330 miles in length, namely, North Islands 2,200; South Islands, 2,000; and Stewart Islands, 130 miles. New Zealand is a mountainous country, but it has many large plains. In the North Island, which is highly volcanic, is situated that famous Thermal Springs District. The South Island is remarkable for its lofty mountains, with their magnificent glaciers, and for the deep sounds or fjords on the western coast. New Zealand is firstly pastoral and secondly an agricultural country. Sown grasses are grown almost everywhere, the extent of land laid down being upwards of 8,000,000 acres, according to government reports. In the South Island a large area is covered with native grasses, and the large extent of good grazing land has made the colony a great wool-and-meat-producing country. The number of sheep in the colony in 1894 was 20,230,829, and the value of the wool exports for that year was about twenty-five million dollars. The frozen meat exports (mostly mutton) for 1894 were valued at about $6,000,000. The North Island, with its adjacent islets, has an aggregate area of 44,468 square miles; the South Island, with adjacent islets, 58,525 square miles; and Stewart Island, 665 square miles. The area of New Zealand is about one-sixth less than the area of Great Britain and Ireland, the South Island alone being a little larger than the combined areas of England and Wales. The North Island extends over a little more than seven degrees of latitude, a distance in a direct line from north to south of 430 geographical, or 498 statute, miles; but as the northern portion of the island trends to the westward, the distance in a straight line from the North Cape to Cape Palliser, the extreme northerly and southerly points of the island, is about 515 statute miles. The extreme length of the South Island is about 525 statute miles. The south island is interceded along almost its entire length by a range of mountains known as the Southern Alps. Some of the summits reach a height of from 10,000 to 12,000 feet, Mount Cook, the highest peak, rising to 12,349 feet. For beauty and grandeur of scenery, the Southern Alps of New Zealand are said to compare favorably with the Alps of Switzerland and even to surpass them in point of variety. So far, only a few of the loftier New Zealand peaks have been scaled, and many of the peaks and most of the glaciers are as yet unnamed. Situated in latitude from 34º25´ to 47º17´, South New Zealand enjoys a climate varying from one similar to that of Italy in the north to that of England on the south. (Map of New Zealand from Harmsworth Atlas 1890, p. 48)

British sovereignty was proclaimed over New Zealand in January 1840, and it became a dependency of New South Wales, Australia, until May 3, 1841, when it was made a separate colony. The government of the colony was first vested in the governor, who was responsible only to the Crown; but in 1852 an act granting representative institutions to the colony was passed by the imperial legislature; and a general assembly, consisting of a legislative council appointed by the governor and an elective House of Representatives, was provided. The first session of the general assembly was opened May 27, 1854. The governor is appointed by the queen; his salary is $25,000 a year, which amount is paid by the colony. The members of the House of Representatives are elected for three years; four of the members are representatives of Maori constituencies.

The estimated population of New Zealand on December 31, 1894, was 686,000, exclusive of Maoris who, according to the census of 1891, numbered 41,993, at that time. According to the census of 1891, the religious complexion of New Zealand was as follows: 250,945 of the inhabitants were members of the Church of England; 141,477, Presbyterians; 87,272, Catholics; 63,415, Methodists; 14,825, Baptists; 6,685, Congregational Independents; 5,616, Lutherans; 3,928, Pagans; etc., 1,463, Hebrews; 308, Unitarians; 315, Society of Friends members; and last and smallest of all, 206 Latter-day Saints, commonly known as “Mormons.” This doesn’t include the Maori population, of whom nearly one-tenth are members of the true Church of Christ. Of the 41,953 Maoris given in the census returns of 1891, 251 females were Maori wives living with European husbands. It also included 1,466 half-castes living as Maoris. In addition to the 41,953 classed as Maoris, there were 1,122 half-castes living as Europeans. Of the Maori population, 1,883 only lived on the South Island and 136 on Stewart Island, thus showing that the bulk of the native population is on the North Island.

Of the white population enumerated in 1891, 612,064 were born British subjects and 14,594 of foreign birth, among whom were 1,603 North Americans (from the United States); 3,663 Germans 2,053 Danes; 1,414 Swedes; 1,288 Norwegians; 711 French, etc. There were also 4,470 Chinese in the colony. The number of bachelors in the colony aged 20 and upwards was 70,197, and of spinsters aged 15 and upwards there were 67,000.

It may be interesting to the ladies of Utah and the readers of the News generally to know (if they are not posted already) that the women of New Zealand enjoy the elective franchise, “The Electoral Act, 1892,” extended to women of both races (whites and Maoris) the right to register as electors and to vote at the elections for members of the House of Representatives. The qualifications for registration are the same for both sexes. Women, however, are not qualified to be elected as members of the House of Representatives. For European representation every adult person, if resident one year in the colony and three months in one electoral district, can be registered as an elector. Freehold property of the value of £25 held for six months preceding the day of registration also entitles a man or woman to register, if not already registered under the residential qualification. Maoris possessing £25 freeholds under Crown title can also register, but, if registered on a European roll, cannot vote for a representative of their own race. For Maori representation every adult Maori resident in any of the four Maori electoral districts can vote. Registration is not required in native districts. The proportion of representation to population is not required in native districts. The proportion of representation to population at the general election for the House of Representatives in November 1893 was one European member to every 9,604 inhabitants and one Maori member to every 10,498 natives.

“Jenson’s Travels,” October 24, 1895 [3]

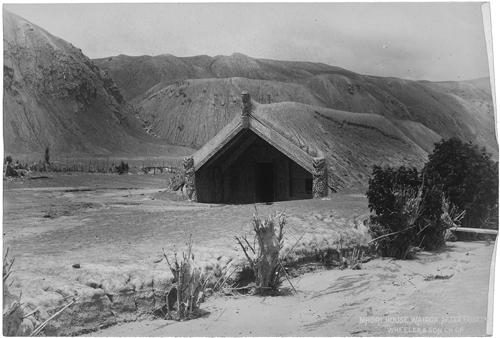

Takahiwai, New Zealand

Tuesday, October 15. For the purpose of visiting the two districts of the New Zealand mission which embrace the branches of the church on the north end of the North Island, Elder William Gardner and myself boarded the small steamer Wellington and sailed from Auckland at 8:00 p.m., bound for Whangarei, about ninety miles away; we spent the night upon the ocean sailing along the east coast.

Wednesday, October 16. Having had a pleasant voyage during the night, the ship stopped at Marsden Point at daylight, and soon after leaving that place we were enveloped in a dense fog, which made it necessary to cast anchor between Grahamstown and Limestone Island. In a short time, however, the fog lifted, and the voyage was continued. At 6:30 a.m. the Wellington landed her passengers at Opau, or the railway wharf about two miles below the town of Whangarei. We now traveled six miles by rail to Kamo, a small coal mining town, where Elder J. H. Willard Goff, who presides over the Whangarei District, met us with two extra horses, on which we rode about four miles inland to the residence of Brother Percy S. C. Going, who lives in a very hilly district of country known as Ruatangata. Here we received a most hearty welcome by Brother Going and family, (Photo of Going family) who are the only members of the Church in the neighborhood and constitute a part of what is called the Opuawhanga Branch. Here we also met Elder Hial B. Hales, who is Elder Goff’s missionary companion in the Whangarei District. We spent the afternoon perusing records, and in the evening we held a cottage meeting in Brother Going’s house. Besides his family and the elders, four nonmembers were present.

Percy Going and family. Courtesy of Rangi Parker

Percy Going and family. Courtesy of Rangi Parker

Thursday, October 17. We spent the day at Brother Going’s, I being busily engaged in perusing the district and branch records of the Whangarei District, assisted by Elder Goff.

Friday, October 18. Brother Going furnished Elder Gardner and myself with a horse each; and, Elder Goff having one of his own to ride, the three of us set out on a twenty-five mile horseback ride to the native village of Te Horo, where a conference for the Bay of Islands District had been appointed for the following Saturday and Sunday. This day’s ride gave me a fair introduction to the clay hills of New Zealand. There are only a few wagon roads through this sparsely populated part of the island, and hence only a few vehicles cross the country; most of the traveling is done on horseback. The face of the country consists chiefly of hills and mountains, the slopes of which generally present a somewhat scary appearance through having been dug again and again in search of kauri gum. Gum digging has in times past been a very profitable occupation in this part of the country, and according to government reports there are still 7,000 persons employed in the business. Since 1853, 169,378 tons of kauri gum have been gathered, most of which has been sent abroad, where it is used in the manufacture of varnish, etc. The gum is mostly dug out of the ground in tracts of country where extensive kauri forests once stood. The gum digger prospects the ground armed with a long sharp spear, which he sticks into the ground where it is sufficiently soft for him to do so, and when he strikes a lump of gum, he digs down for it. This gum, or resin, is simply the solidified turpentine of the kauri tree and occurs in great abundance in a fossil condition in the northern part of the North Island; it is dug up alike on the driest fern hills and the deepest swamps. The purest samples are found on the Cape Colville Peninsula east of Auckland. A large quantity is also obtained from the forks of living trees, but this is considered of inferior quality and fetches a lower price. In the fossil state, kauri resin occurs in lumps varying from the size of a walnut to that of a man’s head. Pieces have been found weighing upwards of 100 pounds. When scraped, the best specimens are of a rich brown color, varying greatly in depth of tint. Sometimes translucent or even transparent specimens are found occasionally with leaves, seeds, or small insects enclosed. When obtained from swamps, the resin is very dark colored, or even almost black, and brings a low price. Transparent or semitransparent specimens fetch very high prices, being used as a substitute for amber in the manufacture of mouthpieces for cigar holders, pipes, etc. The great bulk is used in the manufacture of oil varnishes, and in all countries where much varnish is made it holds the chief place in the market. It is exported chiefly to England and to the United States. The digger’s equipment is of a simple character; a gum spear consists of a light, pointed iron rod fixed in a convenient handle; the gum is dug out with a spade and carried home in a sack. In many cases the spear is dispensed with, and the entire area is dug over to such a depth as the digger thinks likely to prove profitable. An old knife is used to scrape the gum, the scrapings being utilized in the manufacture of fire kindlers. Diggers generally pay a small fee for the privilege of digging on Crown lands. Gum digging in New Zealand is a standing resource for the industrious unemployed. The average price for kauri gum in 1894 was about £48 per ton when exported.

We arrived at the village of Te Horo, situated in the heavy woodland on the Hikurangi River, about the middle of the afternoon, and was welcomed by Elder Charles B. Bartlett, president of, and Thomas J. Morgan, Joseph Markham, and Milo B. Andrus, traveling elders in the Bay of Islands District. There being a flourishing branch of the Church at Te Horo, about thirty native Saints were there to receive us. As soon as we emerged from the timber they commenced to call out “haere mai, haere mai” (“come, come”), and after we had forded the river they strung themselves out in a long line in front of the meetinghouse to receive our undivided greeting, which meant both shaking hands and rubbing noses. This certainly was a new and novel experience for me. I had learned a great number of new departures and native ways during my sojourn among the Hawaiians, Fijians, Tongans, and Samoans; but none of these indulge in that particular mode of greeting which the Maoris call hongi (nose rubbing). Well, I made a failure of the first attempt. Elder Gardner, evidently forgetting that I was a new hand, started out in such good earnest for himself that he was halfway down the line before I had unsaddled my horse and was ready to commence. I was just getting my nose ready to start in when my courage failed me. All at once I seemed to forget the verbal instructions I had received about this same hongi business. Was I to press with the top of the nose, or the left or right side, or all around? I had forgotten all. The president of the branch, who is also a chief, stood at the head of the line; and he was the first to be greeted as a matter of course. There he stood with his large Grecian nose all ready for action. No, I could not; I had forgotten how! Or, rather, I had not learned yet. I simply gave him a hearty regular Mormon hand shaking and passed on to the next, while he gave me a sympathizing look. He seemed to take in the situation; but this was not the case with all the rest. What was the matter with the new elder, or the kaituhituki (writer), as they called me from the beginning? Did I feel above hongi-ing with them, else why didn’t I do like the rest of the elders? Well, I made a public confession before conference was through, and in the absence of a better excuse I tried to make them believe that I was a bashful young man who feared that I would be laughed at if I shouldn’t do it just right; and so I had postponed the experiment till I could learn it in a more private way. But I assured them that as I had been practicing with the president of the branch and others between meetings that I would hongi with all of them before I left them. That was satisfactory, and according to latest accounts none of the Te Horo Saints have apostatized through my neglect of duty.

Our first official act after arriving was to administer to a sick woman, who suffered with female weakness. We were then conducted through the fallen timber and up a steep hill about a quarter of a mile to a neat little farmhouse owned by Brother Eru Reweti, second counselor to the president of the branch, who vacated the house with his family in order to let us occupy it during our visit. We had only been occupying our new temporary home a short time when the bell rang, and soon afterwards a message in the shape of an open-faced little native boy came running up the hill and called to the top of his voice, “Haere mai ki te kai,” which meant, “Come to the food,” or in plainer English, “Come to supper.” All right; we had come twenty-five miles over a rough, muddy, hilly, dangerous road and were hungry, so we responded cheerfully. Our horses were already provided for and were feeding in the green grass of early spring, which abounded on the hillside. This sounds strange perhaps to some of the readers of the News to speak of early spring in October, but such it was; and in coming through the country from Kamo to Te Horo, the green pastures and the young and tender wheat, oats, barley, potatoes, as it had commenced to grow, looked beautiful indeed. October in New Zealand corresponds to March in the northern zone of a similar latitude. Well, the meal to which we were invited was served in the meetinghouse; the food was placed on mats which were spread on the middle of the floor and reached from the door head, or at the inner end; and all must sit on the floor in regular native style except myself, for whom a small box was provided because I was a new hand and consequently not accustomed to Maori ways. But as I was anxious to impress my Maori friends with the fact that I had passed through months of careful training on the smaller islands of the Pacific and had learned to sit on my crossed legs in genuine native style, I respectfully declined the use of the box and insisted the Elder Gardner who was the oldest man and besides the president of the mission was the most proper person to perch upon this seat of honor; and I suggested further that it be placed at the head of the table (mats) for that purpose. The point was sustained, and both elders and Maoris seemed to relish the food, which consisted chiefly of well-cooked meat, potatoes, and bread.

After supper, we commenced our historical labors, the district and branch records of the Bay of Islands District having been brought in for that purpose of being inspected, and contributed information for Church history.

After evening prayer in the meetinghouse, which was preceded by the singing of a hymn and the reading of a chapter in the Bible, the gathering was turned into a genuine Maori poroporo, during which numerous speeches of welcome were made, chiefly directed to Elder Gardner and myself, to which we briefly responded; but as every leading man present seemed to have something to say, the meeting was prolonged till about 11:00 p.m. in the night. This did not mean that all present kept awake all that time; many slept, and some even snored. Even we missionaries were half asleep part of the time, and no doubt I should have gone far into dreamland had not one of the elders paid particular attention to me by whispering a translation of the speeches in my ear as they were being delivered. At length the last speaker was through, and we elders, after shaking hands with all who were not asleep, betook us to our quarters on the hill, where we slept comfortably during the night.

Saturday, October 19. Our conference, which has the semiannual conference of the Bay of Islands District, commenced in the large and commodious Te Horo meetinghouse at 10:00 a.m. Elder Charles B. Bartlett and myself were the speakers in the forenoon, Elder Gardner doing the translating for me. He was also my interpreter in the meeting held the previous evening. President Gardner was the principal speaker in the afternoon, while a number of the native brethren, Elders Gardner and Milo B. Andrus addressed the congregation in the evening. The last-named elder had just arrived from Utah and had been assigned to the Bay of Islands District to labor among the Maoris. We had a good and interesting time, and notwithstanding the rainy weather and a death in a neighboring village, about fifty natives, both Saints and strangers, attended the meetings. After the evening session greeting speeches were again made by a number of natives who had arrived during the day; and they in turn were greeted by the residents of the village.

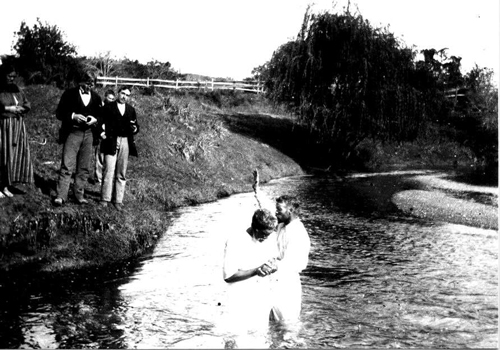

Sunday, October 20. Our conference was continued, and three interesting meetings held, commencing respectfully at 10:00 a.m. and at 3:00 and 7:00 p.m. The historian occupied the time in the forenoon, Elder Bartlett translating for me; in the afternoon Elder Gardner, two native brethren, and Elder Bartlett were the speakers, and in the evening the assembly was addressed by Elder Thomas J. Morgan, myself, and several natives. Between the forenoon and afternoon meetings I baptized two in the beautiful clear water of Hikurangi River. One of them was George Marriner, a half-caste who had come seventy miles from Waihou, on the Hokianga River to attend the conference and to be baptized; the other candidate was Hoterane, a young boy belonging to the village of Te Horo. (Photo of New Zealand baptism) All the Saints and strangers present in the village had assembled on the banks of the river to witness the performance of the sacred ordinance, and as Elder Gardner stood upon the green bank and addressed the assembly on the subject of baptism, it caused one’s mind instinctively to revert to John the Baptist preaching to the multitude on the banks of the River Jordan, or in the wilderness of Judea. The scene certainly was very impressive. After the singing of a suitable hymn, the offering of a prayer, and Elder Gardner’s speech, which was all done in the Maori language, I entered the stream and administered the sacred ordinance of baptism for the first time in my life in the southern zone. The two converts were confirmed in the afternoon meeting, which gave Elder Gardner a good subject for a powerful sermon on the first principles of the gospel. Thus the first conference which I attended in the Maoridom proved a very interesting one to me.

Monday, October 21. I spent the day doing historical labors at our quarters on the hill, assisted by Elders Morgan and Markham, while President Gardner and the other brethren went up the river a few miles to attend a funeral. Another meeting was held in the Te Horo meetinghouse in the evening, at which Elder Gardner was the principal speaker. The news of the good time we were having at the conference had spread to the surrounding villages, and the people kept coming in, some to be baptized. Instead of attending this meeting, I worked on the records till midnight, assisted by Elder Bartlett.

Elder Ezra Stephens baptizing in New Zealand. Courtesy of Rangi Parker

Elder Ezra Stephens baptizing in New Zealand. Courtesy of Rangi Parker

The Bay of Islands Latter-day Saint missionary district embraces the extreme north end of the North Island; it extends southward on the west coast to the village of Tikariu and on the east coast to and including the Bay of Islands. Four elders from Zion are laboring at the present time in this district, which consists of eleven branches, namely, Waitetoki, Te Touwai, Matauri, Ngawhitu, Kaikohe, Tautoro, Waihou, Waitomio, Maromaku, Te Horo, and Mangakahia. The total membership of the district, including children, is 381, of whom ten are Europeans.

The Waitetoki Branch comprises the Saints residing in a village of that name situated on the Pupuke River, which empties into the Whangaroa Harbor on the east coast, the village being about seven miles up the river. It is also about sixty miles north of Kawakawa and is the northernmost branch of the church in New Zealand; it was organized January 17, 1889, by Elders George and Orson D. Romney, with Papu Arapata president; he still presides.

Te Touwai Branch consists of the Saints residing in a village called Te Touwai situated near the east coast on the south side of the Whangaroa Harbor and about three miles south of the town of Whangaroa. The branch was organized April 1, 1888, by Elder George Romney Jr.

The Matauri Branch consists of the Saints residing in the native villages of Matauri, Wataua, and Takou, which are all situated on the east side of the Whangaroa Harbor; the branch was organized in February 1892 by Elder William T. Stewart and others.

The Ngawhitu Branch embraces the Saints residing in a little native village of that name situated inland about twelve miles northwest of Kawakawa; it was organized February 17, 1889.

The Kaikohe Branch consists of Saints residing in and near the village of Kaikohe, which is situated inland about five miles west of Lake Omapere, or about twenty miles west of Kawakawa. The branch was fully organized November 27, 1892, by Elders Edward Atkin and Charles B. Bartlett.

The Tautoro Branch, which was organized February 17, 1889, consists of the Saints residing in the village of Tautoro situated on a mountainous country about five miles southwest of Kaikohe, and about twenty-five miles by road northwest of Kawakawa.

The Waihou Branch was organized by Elder Angus T. Wright and other elders October 6, 1889; it comprises the native Saints residing in the Waihou Valley on the headwaters of the Hokianga Harbor about twenty-five miles northwest of Kawakawa.

The Waiomio Branch, organized October 1888, consists of the Saints residing in a village of that name and also in the neighboring village of Kopuru. Waiomio is situated about three miles south of Kawakawa and is the place where the elders laboring in the district make their headquarters. They get their mail at Kawakawa, a European town, which is situated inland eight miles by rail from Opua, on the Bay of Islands shore. Opua is about 130 miles by steamer northwest of Auckland.

The Maromaku Branch consists of the Saints living in the native villages of Maromaku and Te Tororoa, situated about seventeen miles southwest of Kawakawa, or about eight miles northeast of Te Horo. The branch was organized by Elder William Paxman and other elders January 5, 1889.

Te Horo Branch consists of the Saints residing in the villages of Te Horo, Roma, Kaikou, and Pipiwai, all situated on the Hikurangi River, a tributary of the Waitoa. Te Horo, the principal village, is situated in a narrow valley between wood-covered mountains, about twenty-five miles south of Kawakawa, near the base of the Motatau Mountain, one of the highest elevations in New Zealand north of Auckland. The branch was organized by Elder William Paxman and other elders January 1, 1889, with Hamuera Toko as president. He still presides with Wiremu Te Tairua and Eru Reweti as counselors.

The Mangakahia Branch, which was organized February 17, 1889, consists of the Saints residing on the Mangakahia River in the villages of Te Kiore, Te Kaauau, and Te Haminge. Te Haminge, where most of the Saints reside, is situated about ten miles southwest of Te Horo, or about thirty-five miles southwest of Kawakawa.

In culling from the records, I experienced great difficulties in keeping track of Maori names. The natives of New Zealand are in the habit of changing their names repeatedly in the course of a lifetime; and thus we often find that a native has been baptized in one time, ordained to some office in the priesthood in another, and perhaps set apart to preside over a branch in still another name. I have used my utmost influence against this practice, both in public and in private, and instructed all record keepers to see that these mixtures of names do not occur in the future, as such a practice would almost destroy the value of records for historical purposes. Another trouble that I have also encountered is that a number of elders from Zion have been guilty of writing their names in half a dozen different ways, thus making it impossible to trace them without an interpreter.

Tuesday, October 20 [22]. At an early hour a messenger arrived at our sleeping apartments on the hill at Te Horo, announcing that several persons were waiting at the meetinghouse to be baptized before breakfast. Consequently, we all proceeded to the banks of the river once more; another interesting meeting at the water’s edge, another hymn and prayer, and then Elder Bartlett entered the stream, followed by one young man, two women, and a boy, all of whom were baptized in full view of the people on the banks of the stream, the same as the day before. We then repaired to the meetinghouse, where a confirmation meeting was held, and the ordinance of laying on of hands for the reception of the Holy Ghost was administered to the four persons who had just made covenants with the Lord in the waters of baptism. On the same occasion three children were blessed, after which I delivered a short parting address to the people, with Elder Bartlett as interpreter. The next thing on the program was a late breakfast, then the exchanging of a few small presents as tokens of love and remembrance, then goodbye and rubbing noses with about fifty natives, who placed themselves in a row, for that purpose. We also gave the parting hand to Elders Bartlett, Morgan, Markham, and Andrus, and at 10:45 a.m., Elders Gardner, Goff, and myself mounted our horses and rode off the same way that we had come. While crossing the river, the Saints stood on the bank wishing us goodbye and uttered many words of goodwill, while they swung their hats and waved their handkerchiefs to us, until we disappeared from their view in the bush. We now rode twenty-five miles over hills, valleys, and streams and arrived at Brother Going’s house in Ruatangata at 4:00 p.m.

Thus ended my introductory visit to the Maori people, to whom I at once became attached because of their full heartedness and love for the gospel and the servants of the Lord who are preaching it to them. On general principle the Maoris are a hospitable people. During our sojourn at Te Horo, they provided plenty of food for us elders and all their other visitors three times a day. The meetinghouse served as dining hall. Nearest the wall on either side were placed mats, where the people sat during the meetings and slept at night, while the passage through the middle served as table at meal hours. Our food consisted of good bread, well-cooked pork and mutton, a little butter and jelly, ordinary potatoes, sweet potatoes, vegetables, etc. The hearts of the Saints were overflowing with kindness toward us, and they gave us the best they had. The ringing of a bell announced all meeting, prayer, and meal hours.

“Jenson’s Travels,” November 6, 1895[4]

Gisborne, New Zealand

Wednesday, October 23. We spent a pleasant time at Ruatangata with Brother Going and family, by whom we were treated with much kindness. Brother Going and wife are young people, having four nice little children; they are also young in the church but enjoy the spirit of the gospel. Martha Ruffle, a young unmarried sister, stops with them. At 10:00 a.m. Elders Gardner, Goff, and myself left Ruatangata on horseback and rode nineteen miles by way of Kamo and Hikurangi to a neighborhood known as Opuawhanga, to the residence of Elder Thomas Finlayson, president of the Opuawhanga Branch, who, with his large and interesting family, is about to emigrate to the land of the Saints in far-off America. He had quite recently sold his farm at a fair price and rejoiced very much at the prospects of gathering with the Saints. After spending a short time in pleasant conversation with Brother Finlayson and family, we took a three-mile walk into the bush, piloted by Elder Finlayson, to see one of the largest kauri trees in New Zealand. It stands on the farm of Mr. G. Foden (formerly a member of the church) and on the immediate borders of the great Puhipuhi Forest. Its circumference is about forty-five feet with a gigantic stem of nearly sixty feet below the branches, and seventy-five fit for lumber, exclusive of the top. It is estimated that its top is about 150 feet above its roots. As to its age, nobody can guess it. One enthusiastic writer who visited the tree six years ago uses the following language in describing it: “As one stands beneath this monarch of the forest, listening to the perpetual sough of the wind through its gigantic branches, and reflects that its life history goes back into the mystic unhistoric past—that a thousand years have seen it as we now see it—that probably before London or Rome was, it burst into life, how all that is human is minimized! So far as can be seen, this magnificent tree is still in its youth, and that its future history, if protected, may be as lengthened as its past, and that it will still continue to live when present scenes shall have passed away and are forgotten.”[5] We experienced considerable difficulty in reaching this interesting specimen of nature’s production. Not only was it hard climbing, but the road or path leading to it was very miry and wet in places owing to the recent rains; it also led through a thick undergrowth through which we had to grope our way with care. We were quite tired when we returned to Brother Finlayson’s house about sundown; and after spending a pleasant evening with the family, we enjoyed a good night’s rest.

The kauri is the finest tree in New Zealand and affords the most valuable timber. It varies from eighty feet to one hundred feet and upwards in height, with a trunk from three feet to eight feet in diameter, but specimens have been measured with a diameter of fully twenty-two feet. The bark is smooth and of a dark grey color, and falls away in large flat flakes; and the handsome globular cone is nearly three inches in diameter. The timber is of the highest value and combines a larger number of good qualities in a high[er] degree of perfection than any other pine timber in general use. Many logs are beautifully clouded, feathered, or mottled and are highly valued for ornamental cabinet work, paneling, etc., realizing from £7 to £10 per one hundred feet superficial. Ordinary kauri wood without figure is used for wharves, bridges, and construction work generally. It is exported to a greater extent than any other New Zealand timber and affords employment to nearly one-third of the entire persons engaged in timber conversion in the colony.

Thursday, October 24. I spent the day at Brother Finlayson’s perusing a number of records pertaining to the Whangarei District, Brother Finlayson’s home being the district headquarters at present. About 3:00 p.m. Elders Gardner and Goff started on horseback for Takahiwai, leaving me to follow the next day, in company with Elder Finlayson and others.

Friday, October 25. We arose early, and at 7:00 a.m., I bid Brother Finlayson’s family goodbye, and started in his company for Takahiawi. We walked two miles across some lowlands, beyond which we were overtaken by two of Brother Finlayson’s boys with horses, which they had brought around the swamps that we had crossed on foot. We mounted the animals and rode four miles to Waro, a coal mine and railway terminus. After examining the mines and the adjacent limestone quarries, we walked along the track one mile to Hikurangi, a neat little town with two hundred inhabitants, where we boarded the train at 9:45 a.m., and rode ten miles to Whangarei, having been joined at Kamo by Brother Percy L. C. Going, his nephew, and Hoane Tautahi Pita, a native elder. While they continued by rail to the wharf, Brother Finlayson and I got off at Whangarei to attend to some business, and we afterwards walked two miles to the wharf. Soon afterwards, young Robert Going, from Grahamstown, came across the water with a little boat to take us to his father’s house; but there being too many of us to be accommodated at once, three of us got in first and had a pleasant two-mile sail down the tidal river. We landed at the foot of some hills on the left across which we walked during a heavy fall of rain, while the boat returned for the other passengers. After first paying a visit to Limestone Island, we held an interesting little meeting at the house of Mr. Henry H. Going at Grahamstown, at which I spoke over an hour; and after partaking of the hospitality of Mr. Going, he furnished us with two boats, in which Brother Finlayson and son, Brother Going and nephew, the native elder, and myself embarked at 10:30, and set out for Takahiwai, some eight miles away and across the wide tidal river. Our object in starting at this late hour of the night was to take advantage of high water, as the river is very shallow in many places. There being no wind, we rowed all the way. The night was dark and cloudy, and several times we lost our reckoning, being unable to see either the shore or the mangroves which are growing very thick in the shallow parts of the river, and in fact line it all the way. At length we lost our way in sailing up through an inlet or narrow opening in the mangroves, through which we were to reach the village of Takahiwai. We ran aground again and again, unable to see or keep in the channel. At last we could get no farther whichever way we turned; and so we decided to leave our crafts and make shore, though we did not know where the village was. It was now 2:00 a.m. in the morning. Stripping ourselves of part of our clothing and picking up our baggage, we started in single file on our wading expedition. Though the water was not deep enough to float our boats, we found both water and mud in many places much deeper than we thought necessary for wading purposes; but none complained as we were all brave fellows and would not show the white feather by referring to the cold, the mud, and rocks and shells which cut our bare feet, or the deep holes in the sand or clay into which we plunged periodically. At length we found ourselves on higher ground, where we could feel the green grass under our muddy feet. But where were we? We hallooed long, loud, and often and called out in English, Danish, and Maori; but for a long time all our signals of distress were unheeded; at length the friendly response of a dog was faintly heard in the distance, and we immediately stood off in the direction of the sound and soon found ourselves climbing a hill; more dogs began to howl, and finally a whole regiment (a small one) of canines met us; then we saw a light, and next we found the village. O these blessed dogs! The friendly act on the part of the Takahiwai canines on this occasion made me forgive all the dogs in New Zealand all their former trespasses against me; and I have never kicked a dog since. While our good brethren and sisters slept the sleep that would have known no awaking till morning had we not disturbed them by our actual presence, these uneducated dogs instinctively responded to our calls and saved us from the unpleasant experience of wandering in the mud all night.

On our arrival in the village, we found Elders Gardner, Goff, Bartlett, and Markham, together with a number of natives who had accompanied the Bay of Islands elders from Te Horo, sleeping in the meetinghouse. Room was also made for us, and after shaking hands all around (for all the natives as well as the elders awoke to hear the hurried report of our midnight adventure) we retired to obtain a little rest before assuming the responsibilities of another day, which was about to dawn upon us when we lay down.

Saturday, October 26. We commenced our conference at 10:00 a.m. Elder Goff was the first speaker, followed by myself and Wike Te Pirihi, the president of the Takahiwai Branch. Brother Goff interpreted for me, while I greeted the Saints from their coreligionists in Zion, the Hawaiian Saints, and others, and gave them some items of Church history. In the afternoon meeting, Elder Charles B. Bartlett and Wiremu Te Tairua were the speakers; and Hamuera Toki, Joseph Markham, and Kaio Muhani spoke in the evening.

Sunday, October 27. The conference was continued and closed, three well-attended meetings being held. Henari Te Pirihi, Percy S. C. Going (through interpreter), Eru Reweti, and myself (through Elder Goff as interpreter), and Hial B. Hales spoke in the forenoon. In the afternoon, Elder Gardner was the principal speaker, and in the evening Honetana, Make Te Pirihi, myself (through Elder Goff as translator), Hutana Eparainia, and Elder Gardner were the speakers. The Spirit of God was poured out in rich measure both upon speakers and hearers, and we all had a season of rejoicing. The natives seemed to be in the best of spirits and manifested much interest in the spirit of our conference. During our stay we were treated to the best the village afforded, four meals a day being served. The food was prepared in a neighboring cookhouse, and the meals spread and partaken of on the floor of the meetinghouse. Only the visitors, who had increased to about thirty-five before the conference closed, ate and slept in the meetinghouse. Among the visitors was Elder Peter J. Nordstrand, who has been a member of the church since 1876, and took an active part in the affairs of the mission on the South Island years ago. He gave me important information about the early doings of the missionaries in Christ Church and vicinity.

The Whangarei District embraces all that part of the North Island of New Zealand, which lies south of the Bay of Islands on the east coast and of Tekaritu on the west coast. Its southern boundary is the Kaipara Harbor on the west coast and the Town of the Wade on the east coast. The baptized membership of the district is 232, or 334 souls including children under eight; 41 of these are Europeans, the rest Maoris. Two elders from Zion are laboring in the district, which comprises six branches of the church, namely, Waikarei, Whangaruru, Opuawhanga, Horahora, Te Kahiwi, and Great Barrier. The two elders laboring in the district make their present headquarters with Brother Finlayson at Opuawhanga and receive their mail at Kamo, the latter place being about one hundred miles by steamer and rail north of Auckland.

The Waikare Branch embraces the Saints residing in a village of that name situated on the peninsula south of the Bay of Islands and near the historical town of Russell, twenty miles east of Kawakawa, and about fifty miles north of Whangarei. The branch was organized December 13, 1887, by Elders Elias Johnson and George Romney Jr., with Mita Wepiha as president. He still presides and is one of the ablest and most faithful elders in the mission.

The Whangaruru Branch embraces the Maori Saints residing in the villages of Mokau, Oakura, Punaruku, and other neighboring villages, all situated on the east coast and constituting a district of country known as Whangaruru. The southernmost of the village is about nine miles south of Waikare. This branch embraces what was formerly the Mokau Branch (organized early in 1888) and the Punaruku Branch (organized October 21, 1888). The present branch organization was effected November 26, 1893, with Hoani Tautaki Pita as president.

The Opuawhanga Branch is a continuation of the Mangapui Branch, which was organized by Elder William Gardner about 1886. The branch embraces all the European Saints in the Whangarei District, and Elder Thomas Finlayson, who resides at Opuawhanga, presides. His house lies in a country district about sixteen miles north of Whangarei.

The Horo Horo Branch (formerly known as the Waipa Branch) consists of the Saints residing in the villages of Horo Horo and Waipa, which are situated on the east coast about thirty miles northeast of Whangarei on the Nganguru River near its mouth. The branch dates back to November 1889, when it was organized by Elders Angus T. Wright and George W. Davis. The Kahiwai Branch, first organized by Elders William Paxman and William Gardner in November 1887, is the oldest native branch north of Auckland. It embraces the Saints residing in the village of Takahiwai, which is situated near the Whangarei River, or sound, about twelve miles by water or thirty miles by road south of Whangarei and about three miles in a straight line northwest of Mardsden Point.

The Great Barrier Branch (also called Peki Paaria) consists of the Saints residing on the Great Barrier Island, which lies far out in the ocean about sixty miles northeast of Auckland. The branch was organized by Elders Angus T. Wright and George W. Davis December 4, 1889.

Another branch called Whananaki (organized November 29, 1888) has lately gone out of existence.

Monday, October 28. Brother Finlayson and son, Brother Going and nephew, and Hoani Tautahi Piti took their departure early in the morning. Soon afterwards, the bell rang for morning devotion, and after prayer, we ordained Tetahi Honetana to the office of a priest. The next on the program were speeches of greeting by a number of the leading native brethren present, to which Elders Gardner, Bartlett, Goff, and myself responded. The native speakers all expressed their appreciation of our visit and the good conference just ended, and their great love and respect for us as the servants of God. Both the Takahiwai and Te Horo brethren desired another conference held at their respective places in the near future. After all these proceedings, breakfast was served, and at 11:30 a.m., Elder Gardner and myself took leave of the elders and native Saints, mounted our horses, and rode seven miles to Marsden Point, where we boarded the steamer Wellington and sailed for Auckland at 4:00 p.m., arriving there at 11:00 p.m. We remained onboard till morning, enjoying a good night’s rest.

Tuesday, October 29. We landed at Auckland and found Elders John Johnson and Thomas S. Browning awaiting our arrival. I now spent the remainder of the week in Auckland busily engaged in historical labors, assisted by Elder Johnson. On the Thursday evening, we attended a lecture given by a preacher of the Irvingite persuasion. As his lecture was characteristic of its many truths and correct principles, I approached him after the meeting and complimented him on his lecture. He at once became all attention and, no doubt thinking I would be a good subject for conversion to his creed, gave me pressing invitations to attend the remainder of his lectures and even offered me special private instructions. But when I told him that I was an elder of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, his interest in me suddenly gave way to a spirit of contention, and for some time we had a warm and somewhat hot-tempered debate, which ended in the preacher taking his hat and leaving, Elder Browning and myself challenging in vain for further discussion. I never knew before that the Irvingites, or the so-called Apostolic Church, were so bitterly opposed to the work of God, though Joseph Smith in recording its origin in his history fully warrants that such naturally would be the case.

“Jenson’s Travels,” November 16, 1895 [6]

Nuhaka, New Zealand

Sunday, November 3. Elders William Gardner and Thomas S. Browning remained at Auckland to hold a Maori meeting with some visiting natives while Elder John Johnson and I walked out into the country to fill appointments. While I stopped to hold a cottage meeting in the house of Mr. Thomas Surman, in New Lynn, a little town about seven miles from Auckland, Elder Johnson walked four miles further to Titirangi, and held a meeting in a schoolhouse. In both meetings we had attentive listeners. On our return to Auckland in the evening, we felt impressed that the gospel seed sown on that day would bear fruit some time.

Monday, November 4. I resumed my historical labors in our rather uncomfortable quarters, being obliged to write by a little table in our small room with the bedstead for a seat. The Australasian Mission is certainly in great need of better headquarters.

Tuesday, November 5. After spending the forenoon doing historical work, Elder William Gardner and myself boarded the steamer Tasmania and sailed from Auckland at 2:30 p.m. to make an extended tour to all the districts of the New Zealand Mission lying southward. The Huddart, Parker & Company’s agents were kind enough to give us both free transportation from Auckland via Gisborne, Wellington, and Lyttelton to Dunedin and back again; and I here feel in duty bound to state that our elders have always been well treated by the agents of said company, who also on general principles are endeavoring to make all passengers traveling on steamships as comfortable. From Auckland the course of the Tasmania was southeasterly until Cape Colville was passed at 7:00 p.m.; thence we steamed off across the Bay of Plenty heading for East Cape. The evening was windy, and the sea somewhat rough; seasickness consequently prevailed.

Wednesday, November 6. About 8:00 a.m. we rounded East Cape and changed our course from a southeasterly to a southwesterly direction. We kept pretty close to the shore after this, which afforded us a fine view of the mountainous country and in places rock-bound coast. At 3:00 p.m. we cast anchor in Poverty Bay, off Gisborne, almost on the same spot where the great navigator Captain James Cook anchored October 8, 1769, having only discovered New Zealand a few days previously. But instead of being met by savage warriors in canoes ready for fight like Captain Cook, we were soon approached by a steam launch, tugging a lighter after it for the purpose of landing passengers and freight. But as the winds and waves blowed and rolled toward land, the little craft labored hard to reach the steamer. Getting there at last, it was no easy task to transfer the passengers. The little launch was tossed up against the side of the steamer repeatedly, only to be lowered quite a number of feet the next moment; but by careful manipulation of ladder and hoisting apparatus, the passengers, who were to land in Gisborne, Elder Gardner and myself included, at last found ourselves clinging hard to the tackling and railing of the launch, which finally landed us safely in at the Gisborne wharf at the mouth of the Turanganui River. On landing we met Elders Charles H. Embley and Jacob E. Teeples, who are laboring as missionaries in the Poverty Bay District. They conducted us to the house of Wirihana Tupeka, who presides over the Waikanae Branch and with whom the elders make their headquarters in the Poverty Bay District. He and his wife and niece received us kindly, and we spent a pleasant evening with the family and the elders. I also commenced my historical labors, the various branch and district records having been gathered here for the purpose of being perused. The evening was cold and stormy. Just before night, Elder Joseph C. Jorgenson, of Logan, Utah, rode in with horses for Brother Gardner and myself to ride up to his field of labor—the Waiapa District—where we expected to hold conference the following Saturday and Sunday.

Thursday, November 7. In the morning I was introduced to Hami Te Hau, a sick brother who lived in a tent on the premises of Wirihana Tupeka, and who was the first Maori I ever met who was tattooed all over his face. We also ate new potatoes for breakfast. They were raised in the sand along the beach, where they ripen earlier than in ordinary soil. After spending the forenoon culling from the records, Elders Gardner, Jorgenson, and myself left Gisborne on horseback about 1:00 p.m., for the Waiapa District. A few miles’ ride brought us to the coast, and thence we followed the beautiful sandy beach for several miles until we reached the mouth of the Pakare River, which travelers generally cross on a ferry. But as Elder Jorgenson knew of a place some distance up the stream where the river could be forded in safety, we concluded that we would not patronize the ferryman, as he no doubt had more shillings already than we had. So instead of paying the ferrying fee of one shilling for each man and horse we forded and then rode about three miles inland to the little Maori village Tepune (twenty miles from Gisborne), where Tamati Waka, a nonmember, received us very kindly and gave us boiled potatoes, corn, and cabbage for supper and made us as comfortable as he could overnight. We had quite an interesting time with the family at evening prayer, and during the conversation which ensured Tamati Waka related some of his experience in the land courts and denounced the actions of the Church of England missionaries, who, he said, had taught the Maori to pray to God; but while the confiding Maori was engaged in his devotion, the missionaries and the other pakehas (Europeans) stole his land from under him.

Friday, November 8. We arose early from our beds on the mats in the smoky and dismal quarters where we had spent the night, partook of bread and warm water (with sugar in) for breakfast, saddled up, mounted our horses, and rode away. First we passed up through a picturesque valley; thence we crossed the mountain to the sea beach, which we followed for several miles, thence turned inland again, crossing another mountain to Tolaga Bay, where the town of Uawa is pleasantly situated at the mouth of a river of that name. This place is about thirty-five miles from Gisborne. We now turned inland once more, following the general course of the Uawa River about four miles to Mangaheia, a native village situated on a stream of that name, a tributary of the Uawa. At this place there is a branch of the Church, and here we were to hold our meetings or conference for the Waiapu District. Here we also met Elder Rouzelle E. Scott and Joseph A. M. Jacobsen, who are laboring as missionaries in the Waiapu District in connection with Elder Jorgenson. The native Saints who were at home also greeted us with their usual warmth of heart. I commenced my historical labors at once, assisted by Elder Joseph C. Jorgenson. In the evening, after prayer, speeches of welcome were made by the natives, to which Elder Gardner and I responded. We also administered to a sick sister who lay at death’s door and was raving under the influence of a peculiar spirit, which we rebuked by the power of the priesthood, after which she became quiet and rested well during the night. Instead of calling for the administration of the ordinance for the sick in the first place, the young woman had sought the advice of the Maori priests, but this had only made her worse, and was, in our judgment, the cause of the evil spirit taking possession of her. Brother Tehira Paea, the president of the Mangaheia Branch, placed a room in his house at our disposal during our stay in the place, where we spent a comfortable night.

The Waiapu District embraces that peninsular part of the North Island of New Zealand, which terminates in East Cape and extends to the Pakarae River on the southeast coast and Opotiki on the north on the Bay of Plenty coast. The membership of the district is 204, or 295 souls including children. Three elders, who make their headquarters near Uawa, or Tolaga Bay (thirty-five miles northeast of Gisborne), are the representatives from Zion at the present time in the Waiapu District, which consists of five branches, namely, Uawa (also called Mangaheia), Te Pekahua, Tokomoru, Taumata O Tapuhi, and Te Rahui.

The Uawa Branch comprises the Saints residing in the town of Uawa situated on the Tolaga Bay, at the mouth of the Uawa River, and in the village of Mangeheia, situated inland about four miles northwest of Uawa. There is a small meetinghouse at Mangaheia. This branch was organized December 31, 1884, by Elder John W. Ash and Ezra F. Richards.

Te Pekahua Branch is a continuation of the Mangatuna Branch, which was organized December 9, 1884. It embraces the Saints residing in the villages of Wharekaka, Kopua, Tarakihi, and Mangatuna. Wharekaka, where the meetings are generally held, is situated on the left, or north, bank of the Uawa River, about three miles up from its mouth, or the town of Uawa.

The Tokomaru Branch comprises the Saints residing on the Tokomaru Bay, on the east coast, about thirty-five miles south-southwest of Te Rahui and thirty miles north-northeast of Uawa, or Tolaga Bay. The branch was first organized out of the northern part of the Marahea branch in 1888. On February 25, 1893, a reorganization was effected when it absorbed the remnants of the Marahea Branch, which was originally organized by Elders William T. Stewart and John W. Ash November 30, 1884, with Henari Potae as president.

Te Rahui Branch comprises the Saints residing in three native villages named respectively, Te Rahui, Tauma, and Te Pakihi, of which the two first are situated in the Waiapu Valley and the other on the coast about eight miles northeast of Te Rahui. Te Rahui is situated on the north side, or left bank, of the Waiapu River near its mouth. It is sixty-five miles northeast of Uawa on Tolaga Bay, and near East Cape, being the easternmost of all the branches of the Church in New Zealand. The branch was first organized by Elders John W. Ash and Ezra F. Richards January 11, 1885, and consisted once of nearly 200 members. It is still the largest branch in the district. The general conference of the Australasian Mission was held here in April 1892.

The Taumata O Tapuhi Branch is an outgrowth of the Te Rahui Branch and was organized April 10, 1887. It comprises the Saints residing in the villages of Taumata O Tapuhi and Tarapa, of which the first named is situated about four miles inland from the mouth of the Waiapu River, or the village of Te Rahui.

Saturday, November 9. I spent the day perusing the district and branch records for historical purposes, which proved quite a task, as most of the entries in the branch books were made in the Maori language. In the evening we held our first meeting in a low and rather dismal-looking meetinghouse. Elder Gardner and I were the speakers, Brother Jorgenson translating for me. About sixty people were present—all natives except the elders. About the same number attended the meetings on the following day.

Sunday, November 10. We held three good and interesting meetings at Mangaheia. I occupied most of the time in the forenoon, Elder Jorgenson again being my interpreter; in the afternoon, Elder Gardner spoke on the first principles of the gospel. The evening session was mostly devoted to bearing testimonies, I also being among the speakers. Excellent testimonies were borne, and the natives were so anxious to speak that two or three sometimes rose to their feet simultaneously for the purpose of talking. The meeting was a long one, as nearly all who were present—both men and women—had something to say. Among the speakers were quite a number of intelligent and representative Maoris, including some nonmembers. The Holy Spirit was poured out to such an extent in all our meetings that we left the people feeling well and the Saints full of determination to renew their efforts in serving the Lord faithfully and true. While the evening meeting was in session, the sick woman to whom we had administered several times during our stay died. This was no surprise to us, as we were not permitted in our administration in her behalf to promise her a prolongation of life.

Monday, November 11. After taking leave of Elders Scott and Jacobsen and those of the native Saints who had not already taken their departure, Elders Gardner, Jorgenson, and myself mounted our respective horses and started on our return trip for Gisborne at 7:30 a.m. At Uawa we took leave of Rutene Kuhukuhu and family. Mr. Rutene was once a faithful member of the Church, but he fell from grace like others have done. He has, however, retained his love for the gospel and the brethren and is desirous of once more becoming a member. After riding twenty miles we stopped to let our horses bait on the banks of the Paparae River, while Elder Jorgenson and I took a refreshing swim in the beautiful stream. This was my first experience of that kind in New Zealand. Resuming our journey at 1:30 p.m., we forded the river, which was a somewhat dangerous undertaking, as the water was quite deep, the tide being in. Tired and weary after our long ride, we arrived at Mr. Adolph Hansen’s house near Gisborne at 6:00 p.m. There we spent a pleasant evening with the family and some invited relatives, talking gospel, singing songs, reciting, etc. Mr. Hansen’s wife is a member of the Church, and he himself is a good friend of the elders. At a late hour we finished our long day’s journey by walking and riding to our former quarters on the premises of Wirihana Tupeka.

Tuesday, November 12. We settled down to hard work copying and culling from the district and branch records, assisted by Elder Embley, whom we had met again the evening previous at Mr. Hansen’s house. In the evening we held a meeting in Brother Wirihana Tupeka’s house; we also received our home mail, including copies of the Deseret News, which gave us the minutes of the October conference held in Salt Lake City and other items of news which are always interesting and welcome to an elder in a foreign land.

The Poverty Bay, or Turanganui District, consists of a tract of country lying adjacent to the town of Gisborne, with a coastline extending from the top of the mountains southwest of Muriwai, or the south line of Cook County, to the mouth of the Pakarae River on the northeast. It consists of four branches with a total membership of 90, or 126 souls including children. The names of the branches are Waikanae, Rakaututu, Tawhao, and Muriwai. The two elders laboring in the district make their headquarters at Gisborne, or the Waikanae Branch, where they also receive their mails.

The Waikanae Branch embraces the Saints residing in Gisborne and vicinity, two being European Saints. It is a continuation of the Papawharaki Branch, which was organized November 18, 1884, with Te Whatonoro (John A. Jury) as president, and was one of the first Maori branches in New Zealand. From 1887 to 1894 it was known as the Kaiti Branch. Wirihana Tupeka, with whom the elders make their home, now presides over the branch and is a very faithful and hospitable man.

The Rakatutu Branch embraces the Saints residing in the five native villages called respectively, Karaka, Rakaiketeroa, Waihoro, Takepu, and Rakaututu. The last-named place, where the meetinghouse stands, is about twenty miles inland from Gisborne in a northwesterly direction. It was in this branch at the village of Karaka, that the Book of Mormon was translated into the Maori language by Elders Ezra F. Richards and Sondra Saunders, under the direction of Elder William Paxman. The village of Karaka is situated on the bank of Waipaoa River, two miles northwest of Rakaututu. The branch was organized October 4, 1885.

The Tawhao Branch consists of the Saints residing in the native villages of Tawhao, Whakato, and Whareho, all situated on the Waipaoa River about two miles inland from Poverty Bay and about twelve miles southwest of Gisborne. The branch was first organized January 26, 1886, by Elder John W. Ash.

The Muriwai Branch embraces the Saints residing in the villages of Muriwai, Whareongaonga, and Tanatapu. The first-named village is situated on Poverty Bay, about sixteen miles southwest of Gisborne. This branch, which was organized by Elder John W. Ash and Ihaia Hopu September 23, 1884, is the oldest, largest, and best branch of the Church in the Poverty Bay District. Two of the general conferences of the Australasian Mission, namely, in April 1886 and April 1887, were held at Muriwai.

“Jenson’s Travels,” November 21, 1895 [7]

Te Hauke, Hawke’s Bay, New Zealand

Wednesday, November 13. We arose early, and I worked on the records till 10:00 a.m., when we commenced another meeting at Wainui, near Gisborne, at which I spoke through Elder Jorgenson as translator. We held another meeting in the afternoon at which Elder Gardner was the speaker. Immediately after closing that meeting, Elders Gardner, Embley, Jorgenson, and myself took leave of Elder Teeples and the native Saints, mounted the horses which had been provided for us, and rode sixteen miles over a good, though roundabout, road and through a beautiful and fertile tract of country to Muriwai, a native village situated on the lowlands near the beach, which contains the oldest and best branch of the Church in the Poverty Bay District. We put up with Te Keepa, the president of the Muriwai Branch, who received us very kindly and made us comfortable during the night. We held no regular meeting in the evening but had an interesting time with the family and a few others who came in after prayer.

Thursday, November 14. Our time at this place being very limited I worked with the records part of the preceding night. At 9:00 a.m. Elders Gardner, Embley, Jorgenson, and myself and a native brother continued our journey from Muriwai, and we now traveled thirty-five miles over mountains and valleys, through gorges and timber, following a genuine New Zealand bridle path to Mahanga, a native village situated at the foot of the mountains on the seashore and near the narrow neck of land which separates the Mahia Peninsula from the rest of the island. We arrived at this place at 5:30 p.m., and we bid welcome by Elder Lewis G. Hoagland, of Salt Lake City, who presides over the Mahia District, and also by the native Saints residing at Mahanga, which constitute one of the seven branches of the Church in the district named. Soon after our arrival, Elder James N. Lambert, another of the elders laboring in the Mahia District rode into the village. In the evening we held a little meeting, at which Elder Gardner and I were the speakers. We then retired, but not to sleep, though we needed that as well as rest very much after our long, tiresome ride over the mountains. The mosquitoes and fleas had apparently formed a conspiracy against us. Both seemed to be as numerous as the boulders on the seashore at this particular place; and they were determined to feast at our expense, notwithstanding all our efforts to the contrary. Even Brother Embley, who always carries a flea sack with him for protection during nights, found that extraordinary apparel altogether inadequate to afford his person protection on this occasion. It might serve a good purpose elsewhere but not in Mahanga. As for the rest of us, we were unable in the morning to tell which of the numerous bumps and swellings on our itching limbs had been produced by mosquitoes and which by the fleas. Portions of our bodies reminded me or a certain relief map of a very mountainous country which I saw at the World’s Fair in Chicago two years ago.

Friday, November 15. We resumed our journey at 9:00 a.m. and rode four miles, part of the way along the sandy beach, to Kopuawhara, a native village situated on the isthmus which connects the Mahia Peninsula with the mainland. Here we received a hearty welcome by the native Saints, and after rubbing noses, shaking hands, etc., I settled down to my usual historical work assisted by Elders Hoagland and Lambert. We also met Elder James C. Allen, who labors in the Mahia District, and is soon to succeed Elder Hoagland in the presidency of the district. In the evening we held a good and well-attended meeting. Besides the members of the Kopuawhara Branch, quite a number of Saints from the neighboring branches of Mahanga and Waiwhara were present. Elder Gardner and the historian were the principal speakers. After the meeting, the natives indulged in the usual speech making. It was welcome to Brother Gardner and his traveling companion and farewell to Elder Hoagland who visited this part of his district for the last time prior to his departure for his home in Zion.