William G. Hartley, “Edward Hunter: Pioneer Presiding Bishop,” in Supporting Saints: Life Stories of Nineteenth-Century Mormons, ed. Donald Q. Cannon and David J. Whittaker (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1985), 275–304.

William G. Hartley was a research historian for BYU’s Joseph Fielding Smith Institute for Church History when this was published. He received bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Brigham Young University and completed doctoral course work at Washington State University. This essay stems from Hartley’s research into the historical development of the office of Presiding Bishop.

When Heber J. Grant was young, his mother once crossed the street diagonally. Presiding Bishop Edward Hunter met her and said with the usual twinkle in his eye and double phrase on his lips: “Rachel, Rachel, go straight, go straight. Be careful. Cut a corner and miss heaven, cut a corner and miss heaven. Keep in the straight path.” [1] Young Heber and other youths of his day grew up mimicking the double phrases of the bewhiskered Pennsylvanian, and they repeated many proverbs and aphorisms they knew were his. Although forgotten today, Edward Hunter was a well-known and well-liked General Authority in his day because he was colorful and a bit eccentric, and because his fair but kindly ways of performing as Presiding Bishop pleased so many Saints.

He was a pioneer Presiding Bishop in two ways. First, he presided during most of the Mormon pioneering years and longer, from 1851 to 1883. His firm hand on the Church’s temporal reins helped steer it through dramatic transformations in size and procedures. During his thirty-three-year term, the Rocky Mountain Saints’ population grew from 11,000 to over 120,000 and the number of wards increased from forty to about three hundred. [2] Because he had direct responsibility for people and resources, such explosive growth in the basically cashless desert oasis taxed his executive talents.

He also pioneered in terms of the office and calling of Presiding Bishop. The office had barely developed beyond an embryonic stage when Hunter’s predecessor, Bishop Newel K. Whitney, died in 1850. During the next decades, Bishop Hunter firmly carved the Presiding Bishopric’s niche into the Church’s General Authority hierarchy. Of concern here are Bishop Hunter’s two most demanding responsibilities: tithing supervisor, with the corollary task of caring for the worthy poor, and president of the Aaronic Priesthood.

The Call

When Elder Heber C. Kimball announced to the April 1851 general conference that Bishop Edward Hunter would succeed Bishop Whitney, he warned: “I wish Bro. Hunter to understand that he has now got into a place, where he will be thumped and pulled out. Can you go it?” The large fifty-eight-year-old bishop—he weighed over 250 pounds—replied, “I will do the best I can.” Elder Kimball continued: “I can recommend him to fill that office, as a man of God, and a man of business.” [3]

After Edward’s conversion to Mormonism in 1839-1840, his commitment to the gospel never wavered. Once socially and financially prominent in Pennsylvania, he surrendered the good life of country squire to emigrate to Nauvoo and there consecrated great wealth to the Lord. His loyalty and generosity to Joseph Smith were unbounded, causing Joseph to tell him in the name of the Lord to cease donating. “In all of early Church history,” writes a Hunter biographer, “we find no other convert past middle age who had comparable wealth that consecrated his material wealth and mortal life to a similar extent” [4] On another occasion Joseph Smith told Edward: “I have enquired of the Lord concerning you, and you are favourable in His sight.” [5] When Joseph was martyred, Edward passed his loyalty from Joseph to Brigham Young, in part because he witnessed the mystical moment when the mantle of Joseph descended upon Brigham and transformed his appearance. During the trek west Edward Hunter, who had been Nauvoo Fifth Ward bishop, served as a Winter Quarters bishop and then in 1848 captained a company of a hundred into the Valley. [6]

In 1849 when Salt Lake City was divided into wards, he became the Thirteenth Ward’s bishop. When called as Presiding Bishop in 1851, he was judged to be a careful and thorough businessman, a person with “great knowledge in temporal things.” By background he was a farmer, leather curer, a cattle expert in terms of breeding, handling, judging, and a businessman. [7]

In 1851, the time of Edward Hunter’s call, the office of Presiding Bishop was not well defined. The Bishop’s role when the law of consecration was being practiced in Missouri was fairly clear, but its role in Nauvoo’s temporal affairs was less so. When Newel Whitney, “a most upright and thorough business man,” became Presiding Bishop in 1848, President Young directed him to manage tithing, establish home industry, and care for the poor; but the confusion caused by the Utah migration seems to have precluded firm procedures by the time Bishop Whitney died. [8] President Young said that bishops in Nauvoo “never seemed to understand the duty and office of a bishop.” Regarding Bishop Whitney, he confessed: “I did often chastise him severely, to try to get him to understand his office.” He added that Bishop Whitney, near the end of his life, seemed “to have waked up out if a deep sleep, and began to understand something of his office and duty.” By contrast Brigham once said, Brother Hunter never was chastised like Bishop Whitney. Why? “Because I knew . . . he came into this Church, and had transacted business on a large scale, was a good and competent judge of Horses, Cattle, Cows, Grain Etc; and therefore did not need those severe chastisements that some of you bishops are obliged to take from time to time.” [9]

Edward served as Presiding Bishop for one year on a trial basis and then was ordained. Brigham Young and Heber C. Kimball were his counselors. In 1854 Edward was released as Thirteenth Ward bishop. In 1856 Leonard W. Hardy and Jesse C. Little became his counselors, and at that point the three-man Presiding Bishopric as we know it today emerged. Hardy also continued as Twelfth Ward bishop until 1877. Little was replaced in the Presiding Bishopric in 1874 by Robert T. Burton, bishop of the Fifteenth Ward. [10]

We look in vain for indications of formal meetings between the Presiding Bishopric and the First Presidency. Available daybooks for the Historian’s Office and the Presidency’s Office keep good track of Brigham Young’s activities, but mentions of Brigham’s meeting formally with Bishop Hunter are rare. Informal consultations seem to have been the rule. During Edward’s first years as Presiding Bishop he met regularly on Sunday afternoons with the First Presidency and members of the Twelve in a prayer circle, where leaders discussed Church problems and where Edward evidently obtained occasional instructions. After receiving formal counselors in 1856, Edward was told by the First Presidency “to come into the councils of the first presidency, and feel that there was his place and prerogative and not for one moment to think he was intruding.” [11]

Bishop Hunter continued a tradition, started by Bishop Whitney, of meeting regularly with the Salt Lake Valley bishops and others from more distant wards who could attend. These “town meetings” of bishops, or bishops’ quorum meetings, provided Bishop Hunter and the First Presidency a regular forum for instructing and for receiving feedback. The First Presidency attended, but not regularly. At times they gave Hunter instructions before the meetings, as in 1857 when he “informed the meeting that he had an interview with the first presidency a short time prior to the meeting and they expressed themselves satisfied with the labors of the Bishops.” Bishop Hunter frequently took policy-type questions, raised at the meetings, to the First Presidency for clarification. [12]

During most of this period, the First Presidency’s headquarters were in Brigham Young’s office on Brigham’s block. Bishop Hunter had an office a block west in the General Tithing Office. Both offices had their own clerks and record books. As near as the system can be pieced together now, the main finance books for the Church were the trustee-in-trust ledger books in the President’s office. These master records included records received from daybooks and account books kept by the Church public works clerks and the General Tithing Office clerks. But Hunter’s office daybooks, which recorded tithes on hand at the General Tithing Office, evidently were turned in periodically and made permanent records in the trustee-in-trust master books. [13]

Bishop Hunter knew his role was subordinate, second level, a carry-it-out type job rather than a policy-making job. While some members and bishops believed that temporal matters should shift from the First Presidency to the Presiding Bishopric, and that temporal matters ought not to be the concern of the Melchizedek Priesthood, the First Presidency thought otherwise. [14] Said Heber C. Kimball in 1854: “Many wish for the time when President Brigham Young and his brethren would be relieved from attending to temporal matters and to attend to spiritual matters altogether. You will have to wait for this until we get into the spiritual world. . . . All things pertaining to this world, both spiritual and temporal, will be dictated by the Prophet.” [15]

Brigham Young made his position clear, too. He told a Parowan group in 1855 that Bishop Hunter was called “to help the 1st Presidency in temporal matters.” But if the First Presidency could be in two places at once, he added, “they would attend to the Bishop’s business.” But even God could not be in two places at once, he said, “hence the necessity of helps and governments in the priesthood to aid the presiding authorities.” [16] In 1860 Brigham Young said the Presiding Bishopric had charge of temporal matters “and were under the immediate dictation of the 1st Presidency.” [17] Willard Richards said that if Bishop Hunter should counsel wrong “it is the business of the First Presidency . . . to correct him, from whom he receives his instruction.” [18]

One temporal activity the First Presidency did not turn over to the Presiding Bishop was the public works projects. Through the trustee-in-trust office, the Presidency supervised the temple, tabernacle, and other construction projects and workers, paying the workers in tithing goods and scrip issued from Hunter’s office. [19]

Tithing Manager

Tithing was the portly Bishop’s number one responsibility—encouraging, receiving, storing, allocating, and accounting for animal and produce tithes, properties, labor tithes, and some cash.

From Bishop Whitney he inherited no smoothly working tithing operation. So, with the First Presidency, he had to develop, refine, and manage a complicated non-cash tithing system that pumped economic life into the basically poor Church. His first summer in the saddle, 1851, he saw tithes barely trickle into the new tithing storehouse’s cellars and apartments. Skimpy donations meant Church projects suffered for want of lumber, materials, and laborers. Even a tithe of the tithing due, said the First Presidency’s epistle that fall, “would have enabled us to enclose the Temple Block as we had anticipated.” [20]

A new thing push soon came. That September Bishop Hunter and the First Presidency announced a new program that required not just tithing on increase and labor but once again, as in pre-exodus days, on all that a Saint possessed, even if he had tithed on all upon conversion – as was then expected. Fall 1851 general conference attenders voted to comply. To launch the stepped-up tithing program three special traveling presiding bishops were sent to help gather in and forward tithes to the general office. [21] A November circular said that Bishop Hunter “has charge of all receipts and expenditures relating to tithing,” and the appraising of properties and recording of donations. [22]

So Hunter’s first year proved to be a busy one that left him overwhelmed. “Many times I am so crowded with business,” he lamented in October 1851, “that I have not time to treat my brethren with that civility and kindness that they are entitled to and which would be congenial to my feelings.” [23] Besides receiving goods and recording them, he had to handle a wave of questions from bishops. How much were cows worth this year? Oxen per yoke? Could wheat be taken in place of property tithing? How should perishables like butter and eggs be stored? Could there be regional storehouses built? The results of the push, announced in April 1852 conference, earned Brigham Young’s praise: “There has been more done by the Bishops in the last 7 months than in the previous 7 years, and I feel to bless you.” “Never before,” the First Presidency broadcast, “has the Lord’s storehouse been so well supplied.” [24]

The Seventh Epistle by the First Presidency in April 1852 provides one rare disclosure of Church tithes. From 1847 to 1851, the letter noted, $390,261 had come in as tithes. Expenditures, amounting to $354,000, went for public-works shops (blacksmith, carpenter, paint), for a barn and storehouse for tithes, for a bowery and a tabernacle, for factories and lands, for clerks and superintendents, and for provisions for emigration. “Little had been received in cash,” the report concluded. [25]

The tithing success earned Bishop Hunter a permanent job. “I am going to present the case of Bishop Hunter,” President Heber C. Kimball, First Counselor in the First Presidency, told the April 1852 conference. “He has never been ordained to that calling. We thought we would prove him before we ordain him.” They then ordained him on 11 April “to preside over the temporal affairs of our God on the earth,” and blessed him with powers to discern, to judge righteously, and “to lift the hearts of the Saints.” More traveling bishops were called that conference to assist the Bishop. [26]

Not wanting another year-end inundation at the General Tithing Office, Bishop Hunter changed tithing procedures so that henceforth local bishops settled with tithepayers and made up annual ward tithing ledgers. Tithe-paying thus was localized. But local record keeping posed a serious problem. “There never has been a bishop yet who has made a report that would give me any knowledge of the condition of his ward,” Brigham Young complained in 1855. [27] He wanted records good enough “that Bishop Hunter can read it right; and know how [much] Oxen, Horses, Cows, Sheep, Lambs, Pigs, Fowls . . . Eggs, Butter, and Cheese, Produce of every kind, and money” was given. Bishop Hunter therefore issued a circular letter that explained record keeping, the disbursements of tithing, and answered typical tithepayer questions. From 1852 to 1854 ward’s received record books and built local tithing storehouses. By 1854 storehouses stood or were being built in Provo, Lehi, Springville, Palmyra, American Fork, and elsewhere. [28]

In 1854 the tithing requirement was turned up another notch when President Young announced in April conference that Saints could move beyond tithing to voluntarily consecrate all their property to the Church. The Saints voted to comply with this law “first given to Brother Joseph.” But much interest and sermonizing produced little consecrating, mainly because of legal snags in the deed form. Scripture and tradition place the Presiding Bishop in the role of manager of consecrated properties, as Bishop Edward Partridge was in Missouri. Many Utahns wondered if Edward Hunter would assume the role Bishop Partridge had held. But the deeds were conveyed to Brigham Young as trustee-in-trust and not to the Presiding Bishop. What Bishop Hunter’s reactions were to his backseat role in the renewed consecration effort is not known. [29]

However, that Bishop Hunter thought he should play a bigger role in Church temporal management is shown by his proposal in the late 1850s that the Twelve cease earning their own livelihoods and be sustained from general Church funds. Two liked the idea, others were neutral, but some adamantly insisted on earning their own livings. One warned that “if we could do as Bishop Hunter spoke of, we might become dry and dull” and unable to advise Saints on temporal matters. The proposal died. [30]

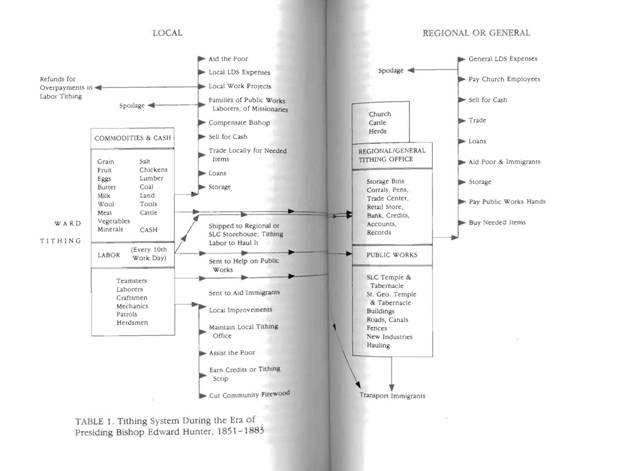

Today’s cash tithing operation seems rather simple when compared to Bishop Hunter’s system. Table 1 shows the basics of the complex system.

Labor tithing, which originated in Nauvoo, meant laboring one day in ten for the Church. “When [a man] has worked nine days for himself,” said one explanation, “then let him take his team and work a day for public works. . . . If he idles 150 days of his time in riding and pleasure, he owes 15 days work for the Lord.” Labor tithing could be used to pay off tithes in kind. It could be commuted and paid by goods or cash. A tithepayer might even hire someone to perform the labor tithing for him. The labor tithe required not just a man with his work clothes and bare hands but also the labor of his work animals and equipment—wagons, teams, shovels, hammers, and drills. The most frequently mentioned type of labor tithing was hauling, either hauling tithing produce from ward storehouses to the General Tithing Office or hauling building materials to or from public work sites. [31]

Underdeveloped regions needed labor, and labor tithing let able-bodied men make projects happen even when there was no cash. Frequently Bishop Hunter issued urgent calls for labor tithing, and notices were read from the stand each Sunday telling what days Salt Lake wards were assigned to provide labor tithing for Church projects. Often men waited until after spring, summer, and fall to do labor tithing, but sometimes President Young told Bishop Hunter “to receive no labour tithing in winter when it was not wanted, when labor was needed, then was the time for it to come, or not at all.” [32] Labor tithing contributed greatly to the building of temples, tabernacles, meetinghouses, fences, bridges, canals, roads, and storehouses. Labor tithing hauled thousands of wagon loads of tithing goods to regional and central tithing stores. It took goods east across the plains and brought immigrants west. It carried supplies to needy Indians, to Mormon militiamen during the Indian encounters and the Utah War, to stranded immigrants, and to local poor. During the move south, it helped many Saints. [33]

As manager of tithing products of all kinds, Bishop Hunter constantly faced four main problems: (1) making proper valuation of goods, (2) storing perishable goods, (3) transferring goods around to meet the overall needs of the kingdom, and (4) record keeping.

Fixing prices for specific items was no easy task. How much was a bushel of wheat worth? a five-year-old cow? a chicken? Periodically, the Tithing Office published a price list by weight or measure, prices Bishop Hunter tried to keep in line with gentile merchant prices and with employers’ pay rates. Even with prices set, Bishop Hunter often had to judge the value of items, particularly cattle. [34] His humor came out sometimes when he examined the scrawny items submitted to the Lord. Once he asked his clerk, George Goddard: “Is there a law, is there a law, against cruelty to animals?” Goddard said yes. “All good laws ought to be enforced,” Hunter muttered; “tithing office chickens, bones sticking through, cruelty to animals, cruelty to animals, ought to be punished.” [35]

Tithing’s main purpose was to provide for the Church’s financial needs. As the First Presidency explained in 1855:

The tithing furnishes our resources for all of our public improvements, and this is generally pain in grain, vegetables, stock, wagons, labour, and other property, and but very little in money, and with the exception of what is needed for the use of the men employed, has to be turned into cash to procure such other articles as are necessary for properly prosecuting business. The constant investment of the funds of the Church in permanent improvements, trouble of changing, and delay in converting into cash, sometimes unavoidably involve us in debt; but if the brethren will be faithful and punctual in paying their tithing in kind, it will relieve us of all embarrassment, and furnish sufficient for the needful purposes. [36]

“While it required much wisdom and labor to collect [tithing],” one bishop said in 1875, “it required much more wisdom to righteously disburse it, so as to bring about the greatest possible good to the greatest number.” [37] Bishop Hunter monitored needs and surpluses, weather and insect reports, immigration and crop projections. Balancing supply and demand throughout hundreds of Mormon settlements was tricky. His first priority was supplying the needs of Church headquarters, and the General Tithing Office had standing orders for tithes to come in if not specifically approved by Bishop Hunter for local use and if no more than one hundred miles distant. Conferences provided ideal opportunities for wheeling the goods into the General Tithing Office. [38] Beyond reminders for regular tithes, Bishop Hunter issued emergency appeals whenever the General Tithing Office ran short. Particular bishops often were picked on to provide products he knew their people produced. In 1874, for example, facing a fuel shortage in public buildings and among the poor, he urged the Coalville bishop to send several train carloads of coal. [39]

The quantity of tithing goods flowing into the General Tithing Office cannot be tallied (tithing account books are not available to the public). But an 1852 report of a fifteen-week period of tithes totaled them this way: 5000 pounds of butter, 2200 pounds of cheese, 1150 dozen eggs. At one time Pleasant Grove shipped fifteen wagon loads of hay and Springville six hundred bushels of wheat. A wagon train from Fort Ephraim brought six wagon loads of wheat, pork, and eggs. [40]

Public works projects proved to be an expensive drain on the treasury. Although historian Leonard Arrington says that public works employees provided bread for themselves, records make clear that many of them depended in whole or large part upon tithing foodstuffs. In 1853, for example, President Young called for tithes because a public works push meant the need for more “provisions to feed the laborers.” An appeal in 1854 asked Saints to “allow the men upon the public works the blessing of comfortable meals.” In 1857 the Tithing Office was dealing out seven tons of flour weekly to workers. In 1874 Bishop Hunter asked Bountiful leaders to send vegetables quickly, “having many families to supply who labor on the temple.” [41]

For most of his term as Presiding Bishop, Hunter employed agents to help funnel the tithes, including traveling bishops, regional presiding bishops who managed regional tithing stores, and various traveling agents. Bishop Hunter and his counselors traveled too. Bishop Hunter had direct contact with regional bishops in Utah and Cache counties, and his traveling bishops and agents supervised outlying counties. Historian Gene Pace has identified twenty-seven regional presiding bishops who served before 1877. [42]

From the early days of temple ordinances, members needed to tithe in order to receive recommends. “Not another soul (will) get an endowment until he has paid his tithing to the utermost and has got his receipt to put in the records,” President Heber C. Kimball warned in 1851. Similar statements punctuate the records during the Brigham Young era. [43]

Beyond his duty to receive, store, transfer, and record tithes, Bishop Hunter served as the leading “drummer” for tithing, particularly during lean agricultural years. For example, when the surplus of 1857 was depleted by late 1859, and the General Tithing Office had no bread, he put a get-tough policy into effect. Also, during the United Order push in the 1870s the tithing program continued, and Bishop Hunter still functioned as chief tithing officer.[44]

Bishop Hunter devoutly believed in tithing. No hypocrisy tinged his appeals for people to pay. People churchwide knew and repeated his slogan, spoken over and over again: “Pay your tithing and be blessed, pay your tithing and be blessed.” Teach the people that the payment of their tithing is doing themselves good, he told the bishops. [45]

As chief caretaker of Church tithes, Bishop Hunter had scriptural duty to aid the Lord’s poor. He spent much time helping two types of needy: needy immigrants coming to Zion and the needy already there.

Starting in 1850, when Bishop Hunter brought the very first Perpetual Emigrating Fund train of emigrants to Utah, he actively worked to aid the annual immigration effort. He supervised the welcoming of immigrant trains to the Valley, sometimes escorting them in. With the help of local bishops and Saints, he tried to offer places to lodge the first night or two and to provide vegetables and other edibles to gladden the weary travelers. [46] An 1866 account depicts Hunter’s role when a wagon train arrived:

Most of the passengers went with the wagons, having friends northward. Some remained with friends in this city and a few were cared for by Bishop Hunter and his counselors, who attended to their wants in a fatherly manner. The bishop and his council were indefatigable in their exertions for the welfare of the passengers. [47]

When word came that wagon companies were having difficulty in Wyoming, Bishop Hunter called on his bishops to send out relief wagons and cattle. Taking orders from the First Presidency, Bishop Hunter, during the 1860s, orchestrated a vast operation of “down and back” Church team trains, calling on wards to provide wagons and teams to go east to pick up immigrants and bring them to Utah. In 1861 he sent out two hundred wagons, a total that grew to five hundred wagons and teams by 1866. [48]

The First Presidency expected Bishop Hunter, with other bishops’ help, to be a population traffic manager, steering new immigrants away from Salt Lake and into valleys where they were needed or where they could find decent livings. In 1852, for example, Bishop Hunter told bishops that some immigrant mechanics could stay in Salt Lake City but that other newcomers had a duty “to move out of the city to those localities where strength is needed, and their labors can be useful.” [49] In 1854 Brigham Young requested bishops to inform Bishop Hunter how many new settlers their wards could take. Some of the reports were Pleasant Grove, 40 to 50 Saints; Provo Third, 22; Nephi, 20; Palmyra, 25 or 30 families; Mill Creek Ward, 13 families; Payson, 75 to 80 persons; an Ogden ward, 4 to 5 families. [50] In late 1855 Bishop Hunter told the bishops’ meeting that “we are distributing the migration companies very well” and added: “Some are very destitute and ignorant as to the methods of getting a living; they should go into the country. They must be taught, for they are full of faith, but not many works. [51] In September 1861 he reported that he “had been busy for two weeks past in making a distribution of the Emigration through the Territory.” Bishop Hunter had to solve problems like that created in the Salt Lake Second Ward when more poor Danes settled there than Bishop Hill could handle; Bishop Hunter arranged for several to move to Sanpete County. In 1869, when the railroad first brought in immigrants all the way to Zion, Bishop Hunter arranged for local Ogden leaders to host and distribute the newcomers. In 1870 he sent twenty Swiss Germans to Cache Valley to start cheese production there.[52]

The poor already in Utah were also a big concern for the big Bishop. Pioneer poverty is an underrated factor in pioneer history. Life stories of pioneers, if read by the bushel, give the feeling of precariousness for common folk. Accidents ruined workers, including fathers; crickets in 1848, 1849, 1850, and grasshoppers in 1855 and later; famine in 1856; regional shortages; crop diseases; too-hot summers and too-long winters knocked pioneers on their backs financially. Even Provo, an area as developed as any outside of Salt Lake Valley by 1870, had difficulty at that late date raising funds needed by its bishop—the people honestly pleaded poverty. [53] A case might be made that most pioneers lived at or below a poverty level. Most of them suffered silently, aided at times by local bishops, Relief Society sisters, or relatives and friends.

Bishop Hunter’s approach to the general poor was constantly to encourage bishops to be sensitive. “Do not make beggars of the poor,” he warned. “It has always been my chief object to find employment for the poor,” he said by way of advice. He urged bishops to seek out the “modest unassuming people” who silently suffer hunger. “We must watch over the poor.” Devise employment or place them in families who have employment for them, he counseled. Every summer he reminded bishops to stockpile wood for winter fuel for the poor. [54]

Only the desperate cases reached the Presiding Bishop’s attention, including the handicapped, retarded, and orphaned. Still, the cries of the poor reached the General Tithing Store constantly, some in letter, others in person. One sampling of Hunter’s letterbooks from 1872 to 1875 shows him giving attention to hardship cases involving a woman with children needing a home, two boys ages four and six needing a home, a blind sister wanting to reach St. George, a blind and poor man needing clothing, an “idiot or foolish boy,” a blind seventy-year-old immigrant, a poor widow who was not paid back a loan, a feeble woman without family, a begging woman with three children, and a blind man from Denmark. [55] In 1873 Bishop Hunter chided a bishop for stinginess in caring for an addled lady and then editorialized: “She like some other unfortunates who need a little aid have no more claim on one ward than another, but wherever they happen to be, there we expect the Bishop to look after them and not allow them to suffer.” [56] Referring to a wife who was mistreated and poor, he said, “such cases absorb nearly half of our time.” [57] Incoming letters told of more situations of abuse, neglect, handicaps, misfortune, and even a drug addict who pleaded with Bishop Hunter, “Don’t let me die for a few ounces of opium” and then requested that the Bishop or “some other good brother will supply me.” [58]

Until asylums or hospitals were built in Utah, the basic method for caring for the handicapped, the retarded and insane, the feeble elderly, and the long-term ill was the cottage system—finding households that would take these cases in return for tithing credits, Church payments, or blessings in heaven. [59]

By the 1860s the problem of housing and feeding the desperately poor had become too burdensome for some bishops. In 1867 President Daniel H. Wells read seventy names of those receiving weekly allowances at the Tithing Office at a total cost of $200 per week—these were in addition to hundreds aided by local bishops. Traveling Bishop Milton Musser surveyed the Church in 1869 and found 1,054 of 109,000 were acutely poor and two-thirds of those, or about 700, were entirely dependent. An idea was discussed that a central poorhouse be set up in wards or in the Valley or that a poor farm be built. The cost of keeping the increasing number of gentile and LDS needy in single rooms was too great. Why not put them in one house? Brigham Young opposed the poor farm idea, but bishops did not drop the matter. At one point the bishops tried to turn a ten-acre city lot into a poor farm and home where the able could work, but the plan fizzled. [60]

Bishop Hunter’s constant commitment was that none should suffer, and whenever bishops ran out of fast offerings to aid the poor, he approved the use of tithing for that purpose. Although basically kindhearted, he had little patience for lazy and shiftless Saints who loafed around. One time he wearied of seeing women hanging around the tithing storehouse steps “showing their dirty legs” and asked bishops either to pick up the food and deliver it to the women or else have men pick it up “and let the women stay at home.” [61] Another time he complained of “chronic beggars, chronic beggars. No good. No good. We have the Lord’s poor, the devil’s poor, and the poor devils.” [62] Of vagrants hanging around the Tithing Office, he remarked humorously: “Hunting work, hunting work; yes, yes, but they don’t want to find it very bad.” But then he instructed his staff. “Feed them, brethren, feed them—mustn’t let them starve.” [63]

President of the Aaronic Priesthood

Priesthood theory, in Hunter’s day, held that the Presiding Bishop was “President of the Aaronic Priesthood in all the World” and therefore presided over all bishops, priests, teachers, and deacons. But in practice how did that presiding occur? In Bishop Hunter’s case, he and the First Presidency agreed on some Aaronic Priesthood matter, and then Presidency then directed him to see that the work was carried out in the stakes. Bishop Hunter, assuming the cooperation of stake leaders to implement the Aaronic Priesthood work. Bishop Hunter’s task as president divides into three activities: (1) presiding over bishops, (2) presiding over Aaronic Priesthood quorums, and (3) participating in ceremonial activities. [64]

“It is the duty of the Presiding Bishop to preside over all Bishops” the First Presidency instructed as early as 1851. However, as president of the bishops, Hunter had no regular voice in selecting them. “There are several Wards without Bishops,” he said in 1856 but admitted that he did not know when they would have them. The First Presidency chose the new bishops and then let Bishop Hunter know who they were, sometimes instructing him to ordain the newly chosen men, often instructing him to teach them their duties. Hunter’s office kept an up-to-date list of Mormon settlements with their presiding officers, for reference and for correspondence purposes. [65] Newly appointed bishops received instructions from Bishop Hunter and his counselors. An 1877 instruction letter, for example, advises about tithing, meetings (“let them be short and spiritual”), fast offerings and testimony meetings (“have no preaching sermons”), calling block teachers (“select the best and wisest men”), solving disputes (“have all their grievances and disputes settled by the lesser priesthood”), and organizing the lesser priesthood properly (“in your stake . . . a full quorum of 48 priests, 24 teachers and 12 deacons”). [66]

If one thing made Bishop Hunter feel like a president, it was when he presided at the twice monthly bishops’ meetings in the city. Because a large percentage of the Church’s bishops lived in the Salt Lake Valley and came to these meetings, he had an effective forum. Normally twenty to thirty wards were represented, but during general conference or when the territorial legislature sat, the bishops’ meetings’ ranks swelled with many “outside” bishops. Although the majority of Church bishops could not attend these meetings, those attending served as a representative body. Their decisions became policy churchwide. Proceedings and decisions were published in the Deseret News or capsuled in circular letters for all bishops to read. The main topics treated in these meetings were tithing, emigration fund donations, public works assignments, specific cases of poor and needy persons, Aaronic Priesthood labors (specifically ward teaching), and domestic manufactures. Also, a wide range of other matters received attention less often: family advice, stealing, voting, land-owning, naturalization, and water problems. These “town meetings” of bishops produced vigorous questioning, challenging, criticizing, disagreeing, and open expressing of opinions. [67]

In addition to the bishops’ meetings, Bishop Hunter communicated with bishops by mail. He received and answered many personal letters. He issued circular letters over his signature, which sometimes were cosigned by the First Presidency. After 1861, the Deseret Telegraph sped up communication and reduced the senior bishop’s mail pile. Bishop Hunter and his counselors also paid personal visits to stakes and wards. In addition, he had a good, personal, one-to-one contact with bishops who visited his General Tithing Office. Now and then he requested written reports from all bishops, reports containing tithing totals, census figures, or immigration assignment lists. In the bishops’ meetings he sometimes called for oral reports from bishops about the numbers in the ward who sustained the Word of Wisdom, numbers rebaptized, numbers of poor, block teaching patterns, and the spirit in ward meetings. [68]

Bishop Hunter often became the man in the uncomfortable middle. That is, he would try to defend bishops against First Presidency criticisms, and then he would have to criticize the bishops. Empathetic and appreciative of bishops generally, and aware of their heavy burdens, he remembered that his ordination called him to lift drooping spirits. Nevertheless, he disliked foot-dragging by bishops. Home manufacturing, for example, was not a popular topic in the bishops’ meetings, causing Counselor Little to admonish that “he did not want to hear any cold water remarks thrown upon it” and that whenever a call came from Brigham Young through the Presiding Bishopric he wanted “a hearty and immediate” support from the bishops. Hunter blamed some of the 1856 Reformation’s chastisements on “the heedlessness of the Bishops.” In 1862 he issued them “a sharp but sensible reproof” for neglecting Aaronic Priesthood matters. [69] Knowing bishops sometimes ignored Bishop Hunter, John Taylor once reminded them: “You bishops are subject to your head, Bishop Hunter, and you cannot shake off the responsibilities that he lays upon you.” [70]

Regarding Hunter’s role as president of the Aaronic Priesthood quorums, Brigham Young reminded him that “it was the duty of the Presiding Bishop to have a full quorum of Priests, Teachers and Deacons, properly organized in every stake of Zion, and hold there regular meetings.” [71] (Notice he said stake, not ward.) In Salt Lake Stake, where Hunter served somewhat like a stake bishop, he influenced the calling of its Aaronic Priesthood presidencies. During his term, Salt Lake Stake held stake Aaronic Priesthood meetings, stake deacons quorum meetings, stake teachers quorum meetings, and stake priests quorum meetings. At general conference, when Salt Lake Stake officers were sustained, voters sustained presidencies for a deacons, a teachers, and a priests quorum—one quorum of each in a stake of about twenty thousand Saints. [72]

In some stakes quorums existed; in others they did not. Bishop Hunter said he labored many years to make the lesser priesthood function, to make it “honorable,” and in 1873 he won Brigham Young’s backing for a pointed epistle instructing him as Presiding Bishop to order stakes to organize quorums. [73] One person Bishop Hunter gently ordered was Apostle Orson Hyde in Sanpete Stake, the acting stake president. “This is not done to gratify a personal ambition to dictate [to] President Hyde who is above me,” his letter respectfully began, “but simply to discharge a duty imposed upon me. . . . You will therefore please to have 3 quorums filled.” [74] President-Apostle Hyde responded, and soon his stake had one priests quorum—twenty-four priests from Manti and twenty-four from Ephraim (the stake’s two leading towns); one teachers quorum—twelve teachers from Manti and twelve from Ephraim; and one deacons quorum—six from each town. [75]

Aaronic Priesthood work was considered adult work. Frequently, high priests, seventies, and elders served as acting deacons, acting teachers, acting priests, much as high priests served as bishops; and a common phrase heard among acting Aaronic Priesthood men was “We are called to act in both priesthoods.” [76]

After the Priesthood Reorganizing of 1877, stakes became better organized and expanded the number of quorums, especially deacons units, so that practically every ward had a quorum. [77]

Bishop Hunter propounded a lofty concept of lesser priesthood work. In Zion, Melchizedek Priesthood bearers had little to do in wards unless they performed “acting” lesser priesthood work, such as block teaching. Hunter’s generation believed that only ordained teachers had priesthood power to reconcile differences between two parties; bishop’s courts could make decisions, but decisions often did not produce reconciliations. The Aaronic Priesthood had power to discern iniquity and help people repent. It had the obligation to watch over the members. It could have the ministerings of angels. While many Saints considered the lesser priesthood to be lesser and lower, Bishop Hunter considered it vital to the Church, and particularly helpful to overloaded bishops. [78]

Bishop Hunter supervised bishops and encouraged Aaronic Priesthood work, and he also performed ceremonial functions as Aaronic Priesthood President. He made official appearances on public occasions. He accepted speaking invitations. He helped dedicate chapels and buildings. He participated in funeral programs. At general conference and at the Sunday Tabernacle sacrament meetings he and his counselors sometimes took charge of the sacrament. Occasionally he spoke at general conferences and priesthood gatherings. When the Salt Lake Temple cornerstones were laid, he orated and then dedicated a stone on behalf of the Aaronic Priesthood. At the St. George Temple dedication he represented the Aaronic Priesthood. [79]

Somehow a hosting role developed for him, too, perhaps because his management of the General Tithing Storehouse made him a food czar. Starting in 1864 he hosted a series of annual reunions for the Zion’s Camp survivors. He also hosted reunions for the Mormon Battalion survivors. Sometimes he was chairman of the Twenty-fourth of July program for the Salt Lake Valley. During the 1870s he helped launch an annual Old Folks’ Day that became a fine Utah tradition. In 1876, to cite one outing, Bishop Hunter and his committee arranged for about six hundred excursionists, half over sixty-five years old, to go by train to Provo. Half the company went free; the others paid $1. At Provo spring-seated wagons and a band met them and off they went to a big picnic. The program included a speech by Bishop Hunter, band numbers, and songs. Dancing, swings, and reminiscing under shady trees occupied the afternoon, and then the group returned to Salt Lake, enjoying cake and lemonade, and singing on the way back. Bishop Hunter became well known as the annual producer of the Old Folks’ Days. [80]

Because of his position and his wisdom, Bishop Hunter received requests to arbitrate, not in the formal court setting, but by way of opinion. Such requests usually involved money or property disputes beyond the jurisdiction of local bishops, such as problems between the bishops, or those involving General Authorities or people outside of Utah. [81]

Leader and Follower

President Brigham Young and Presiding Bishop Hunter worked basically smoothly together as a temporal team, but not without some differences. On occasion Brigham asked for more than the Bishop was doing. In 1855 the President severely chastised the bishops, including Bishop Hunter, giving them a “few reproofs.” In 1857 Brigham became impatient for 1856 tithing to be settled, and Bishop Hunter responded that he would “take measures to ascertain [it] as soon as possible.” Bishop Hunter evidently told bishops to put cellars in the tithing houses, something Brigham Young contradicted. In 1863 Hunter admitted that “he himself had been severely reproved ‘by his superiors’ and could only account for it on the principle, that Whom the Lord loveth, he chasteneth.” In 1872 President Young ordered Bishop Hunter to send a circular to country bishops because the President disliked the waste and spoilage of tithing hay and fodder he saw during a recent trip. [82] When he was chastised for neglect of duty, the Bishop was heard to say: “Thank the Lord, thank the Lord, true son, true son, no bastard, no bastard, whom the Lord loveth he chasteneth.” [83]

The yoking of the younger ex-Vermont glazier with the older Pennsylvania squire seemed both compatible and successful. Both men seemed to understand the subordinate position of the Presiding Bishopric relative to the First Presidency. If Bishop Hunter ever disagreed strongly with the President, he and Brigham must have worked it out, or else Bishop Hunter suffered in silence. Possibly on occasion Hunter failed to enforce or emphasize some policies that the President favored, a form of passive resistance. But there is no evidence that Bishop Hunter ever took a strong opposition stance or that he recruited bishops to go against President Young’s policies. He played his team part well. He was an able man, who conscientiously sought to perform well and “delighted to labor in the Kingdom,” although many times he felt “weary” from it all. [84]

When Brigham Young once praised him while scoring others, Bishop Hunter while walking away was heard to say: “Bishop Hunter, Bishop Hunter, look out, devil’s after you, don’t get the big head, been praised, been praised, flattery, flattery, stubby toe, fall down, break your neck, look out praise, be humble, Bishop Hunter, be humble, devil catch you sure.” Another time he said, “Don’t get the big head, Kill you sure, Kill you sure, Killed more men than anything else in the Church.” [85] The universally high opinion held of him at his death in 1883 indicates that Edward Hunter’s selection as Presiding Bishop thirty-two years earlier was an excellent decision by President Young. Edward Hunter was a well-liked leader who by 1875 was regarded as “fatherly” and “kindhearted.” Liberal responses by bishops to his calls, he said, “melt my feelings.” During his bishopric career, he had tried to do what his setting-apart blessing instructed: “There is nothing so pleasing to me,” he said, “as to cheer up the drooping spirit—it was in my blessing by Prest. Young, and I felt it at the time in a remarkable degree.” [86]

Edward’s personal life, his industries, farms, cattle raising, his plural marriage and family life, his involvement with city government and territorial affairs, and his personal involvement in the Deseret Agricultural and Manufacturing Association are explored well in a published biography, [87] so are not part of this assessment.

One day Clio, the Greek goddess of history, interviewed many second-level leaders in world history. She tabulated her findings and concluded that one of the world’s toughest jobs is being a number two leader—vice-president, executive-secretary, counselor, junior partner—anyone who must administer and execute while lacking independence to frame policy. Many number two men have failed. Clio filed her survey and then whispered to historians to be sure to give credit to number two men who do good jobs. Clio or no Clio, Edward Hunter earned a reputation during his lifetime for being a great man because he learned how to be a good number two man to the strong-willed Brigham Young. In the process, his time, energy, and ideas contributed greatly to moving Utah through the pioneering stage, and he pioneered in the office of Presiding Bishop, shaping that position into one of the vital executing offices in the restored Church.

Notes

[1] Heber J. Grant to Edward H. Anderson, 9 July 1901, notes in author’s possession.

[2] William G. Hartley, “The Priesthood Reorganization of 1877: Brigham Young’s Last Achievement,” Brigham Young University Studies 20 (Fall 1979): 3, 6, 27.

[3] LDS General Conference Minutes Collection, 7 April 1851, Library Archives, Historical Department, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City; hereafter cited as LDS Church Archives.

[4] William E. Hunter, Edward Hunter, Faithful Steward (Salt Lake City: Publishers Press by the Hunter Family, 1970), 70, 268.

[5] Hunter, Edward Hunter, 73

[6] Hunter, Edward Hunter, 78, 80, 89, 91.

[7] Hunter, Edward Hunter, 133, and Presiding Bishopric’s Meetings with Bishops, Minutes, LDS Church Archives, 24 April and 13 July 1851; 11 April 1852; and 7 April 1855. Hereafter cited as Bishops’ Minutes.

[8] D. Michael Quinn, “The Evolution of the Presiding Quorums of the LDS Church,” Journal of Mormon History 1 (1974); 31–38; First Presidency, Fourth General Epistle, 27 September 1850, in James R. Clark, ed., Messages of the First Presidency, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1965), 2:60; Bishops’ Minutes, 7 April 1855.

[9] Bishops’ Minutes, 7 April 1855.

[10] Andrew Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 4 vols. (Salt Lake City: Jenson History Co., 1901–1936), 1:236–43.

[11] Journal History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, LDS Church Archives, Sunday entries during 1852; Bishops’ Minutes, 7 October 1856.

[12] The Bishops’ Minutes covering the period of 1849–1884; Bishops’ Minutes., 27 October 1856.

[13] Willard Richards, “Circular on Tithing,” 5 November 1851, in Journal History of that date; Ronald G. Watt, “The Presiding Bishopric,” typescript, in author’s possession.

[14] Bishops’ Minutes, 11 February and 15 March 1875.

[15] Bishops’ Minutes, 16 July 1854.

[16] LDS General Minutes, taken during conference held in Parowan, 21 May 1855.

[17] Bishops’ Minutes, 6 October 1860.

[18] Richards, “Circular on Tithing,” 15 November 1851.

[19] Watt, “The Presiding Bishopric.”

[20] First Presidency, Sixth General Epistle, 22 September 1851, in Clark, Messages, 2:78.

[21] First Presidency, Sixth General Epistle, 2:90.

[22] Richards, “Circular on Tithing,” 15 November 1851.

[23] Bishops’ Minutes, 12 October 1851.

[24] LDS General Minutes, 9 April 1852; First Presidency, Seventh General Epistle, 18 April 1852, in Clark, Messages, 2:92.

[25] Clark, Messages, 2:96.

[26] Bishops’ Minutes, 11 April 1852 and 6 July 1857; First Presidency, Seventh General Epistle, 18 April 1852, in Clark, Messages, 2:97; a full discussion of traveling and regional bishops is in Donald Gene Pace, “The LDS Presiding Bishopric, 1851–1888: An Administrative Study” (Master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1978), 62–63.

[27] Bishops’ Minutes, 7 April 1855.

[28] Philip K. Smith to Edward Hunter, 12 January 1853, Hunter Incoming Correspondence, LDS Church Archives; First Presidency, Ninth General Epistle, 13 April 1853, in Clark, Messages, 2:113; various Journal History entries during 1854.

[29] First Presidency, Eleventh General Epistle, 10 April 1854, in Clark, Messages, 2:139–40; First Presidency, Twelfth General Epistle, 25 April 1855, in Clark, Messages, 2:169–70; Leonard J. Arrington, Feramorz Y. Fox, and Dean L. May, Building the City of God: Community and Cooperation among the Mormons (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1976), 69–76.

[30] Journal History, 22 February 1859.

[31] Journal History, 8 September 1850; Thomas Bullock Minutes Collection, 5 November 1854, LDS Church Archives; General Tithing Store Letterbook, 1872–1875; Bishops’ Minutes, 18 June 1873.

[32] Bishops’ Minutes, 25 October 1852 and 8 October 1863.

[33] Bishops’ Minutes, 8 and 22 December 1857.

[34] Bishops’ Minutes, 6 January 1870 and 6 November 1873; A. M. Musser, “Tithing Data in 1880,” holograph; “List of Tithing Offices Prices, Weights, and Measures, 1863,” printed announcement, all in LDS Church Archives.

[35] H. J. Grant to E. H. Anderson, 9 July 1901.

[36] First Presidency, Twelfth General Epistle, 25 April 1855, in Clark, Messages, 2:168.

[37] Bishops’ Minutes, 11 February 1875.

[38] Circular to Bishops, 20 July 1854, in Journal History for that date; Journal History, 19 March 1853.

[39] Edward Hunter to Bishop William W. Cluff, 19 September 1874, General Tithing Store Letterbook.

[40] Leonard J. Arrington, “Paying the Tenth in Pioneer Days,” Instructor, Nov. 1963, 387; Journal History, 16 December 1854 and 26 November 1860.

[41] Arrington, “Paying the Tenth,” 386; Clark, Messages, 2:153; Journal History, 7 June 1857; Edward Hunter to Bishop Anson Call, 10 September 1874, General Tithing Store Letterbook.

[42] Bishops’ Minutes; Pace, “The LDS Presiding Bishopric”; Provo Bishops’ Meetings, 1868–1872, LDS Church Archives; Cache Stake, Bishopric Meetings Minutes, 1872–1876, LDS Church Archives.

[43] LDS General Minutes, 7 September 1851; Bishops’ Minutes, 24 June 1851.

[44] Bishops’ Minutes, 8 October 1859; General Tithing Store Letterbook, 1872–1875.

[45] Thomas C. Romney, The Gospel in Action (Salt Lake City: Deseret Sunday School Union Board, 1949), 75; Bishops’ Minutes, 7 April 1855.

[46] Hunter, Edward Hunter, Faithful Steward, 119–25.

[47] Journal History, 13 October 1850 and 18 March 1868; Bishops’ Minutes, 27 August 1860 and 6 November 1855; Manuscript History of Brigham Young, 29 August 1866, 710, LDS Church Archives.

[48] Bishops’ Minutes, 25 April 1860, 13 August 1863, and 25 January 1866; Journal History, 31 December 1861, Supplement.

[49] Bishops’ Minutes, 12 September 1852.

[50] Hunter Incoming Correspondence for 1854; Bishops’ Minutes for 1854.

[51] Bishops’ Minutes, 6 November 1855.

[52] Bishops’ Minutes, 26 September 1861, 6 November 1861, and 24 June 1869; Hunter, Edward Hunter, Faithful Steward, 301.

[53] Provo Bishops’ Minutes for 1870.

[54] Bishops’ Minutes, 12 February 1856, 1 September 1870, 29 January 1856, 3 June 1856, 7 June 1853, and 27 July 1865.

[55] General Tithing Store Letterbooks, 1872–1875.

[56] General Tithing Store Letterbook, 27 October 1873.

[57] General Tithing Store Letterbook, 16 September 1874.

[58] Hunter Incoming Correspondence, 19 February 1856.

[59] General Tithing Store Letterbook, 1872–1875.

[60] General Tithing Store Letterbook; Bishops’ Minutes, 5 December 1867, 15 April 1869, 25 January and 8 February 1866, 5 December 1867, 24 September and 5 November and 3 December 1874.

[61] H. J. Grant to E. H. Anderson, 9 July 1901.

[62] Bishops’ Minutes, 27 October 1857.

[63] Romney, Gospel in Action, 75.

[64] Bishops’ Minutes, 6 October 1860 and 11 January 1877.

[65] Willard Richards, Circular on Tithing, 15 November 1851, in Journal History of that date; Bishops’ Minutes, 22 April 1856. When Jordan Ward needed a bishop, Hunter said he would “inquire of the President” about “appointing a bishop there” (Bishops’ Minutes, 7 January 1852). On 14 March 1857, Brigham Young wrote to Hunter that “we have nominated and appointed Richard Cook a Bishop to succeed B. Thomas Kington of W. Weber, and wish you to give such instruction and counsel as you may deem necessary and attend to his ordination” (Hunter Incoming Correspondence). In 1877 Brigham Young stated that Bishop Hunter presided over all bishops, not just those attending the bishops’ meetings. (See Bishops’ Minutes, 23 August 1877); Bishops’ Minutes, 22 April 1856.

[66] Bishops’ Minutes, 10 July 1877.

[67] Bishops’ Minutes, 1849–1884.

[68] General Tithing Store Letterbook, 1872–1875; Hunter Incoming Correspondence; Presiding Bishopric, Circular Letter File, 1851–1883, LDS Church Archives; and Bishops’ Minutes, 1851–1883. Hunter left Salt Lake City to visit outlying wards in 1851, 1853, 1854, 1856, 1861, 1864, 1867, and probably many other times.

[69] Bishops’ Minutes, 30 July 1863, 13 February 1862, and 30 September 1856.

[70] Bishops’ Minutes, 11 January 1877.

[71] Bishops’ Minutes, 11 September 1873 and 10 July 1877.

[72] Bishops’ Minutes, 25 November 1852; see also Presiding Bishop’s Office, Aaronic Priesthood Minutes, 1857–1877 (which are Salt Lake State Minutes) and Salt Lake Stake Deacons Quorum Meeting Minutes, both in LDS Church Archives.

[73] Bishops’ Minutes, 13 August 1874.

[74] Edward Hunter to Apostle Orson Hyde, 17 October 1873, General Tithing Store Letterbook.

[75] Sanpete Stake Aaronic Priesthood Minutes, 1873–1877, LDS Church Archives.

[76] Hartley, “Ordained and Acting Teachers in the Lesser Priesthood, 1851–1883,” BYU Studies 16 (Spring 1976): 375–98.

[77] Hartley, “The Priesthood Reorganization of 1877: Brigham Young’s Last Achievement,” BYU Studies 20 (Fall 1979): 3–36.

[78] Hartley, “Ordained and Acting Teachers,” 381–86.

[79] Journal History, 15 July and 19 August 1860, and 4 April 1877; Deseret News, 16 April 1853.

[80] Journal History, 19 October 1864 and 10 October 1870; Hunter, Edward Hunter, Faithful Steward, 137; George Goddard Journal, 8 June 1876, LDS Church Archives.

[81] Hunter Incoming Correspondence.

[82] Bishops’ Minutes, 15 May 1855, 7 April 1857, 17 December 1862, 18 June 1863, and 10 October 1872; Jane Rollins to Edward Hunter, 17 December 1862, Hunter Incoming Correspondence.

[83] H. J. Grant to E. H. Anderson, 9 July 1901.

[84] Bishops’ Minutes, 23 September 1856 and 12 May 1857.

[85] Heber J. Grant remarks at funeral of Oscar F. Hunter, 28 August 1931, notes in author’s possession.

[86] Millennial Star 45 (19 Nov. 1883): 737–46; Journal History, 3 June 1875; Bishops’ Minutes, 26 October 1851 and 31 July 1855.

[87] Hunter, Edward Hunter, Faithful Steward.