Theodemocracy’s Twilight, 1869–1896

Derek R. Sainsbury, “Theodemocracy's Twilight, 1869-1896,” in Storming the Nation: The Unknown Contributions of Joseph Smith’s Political Missionaries (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 281‒98.

We are told to be united, for in union is strength. Are we united? . . . Now where is Zion? . . . What does it all mean?

—Former electioneer Nancy Naomi Tracy in 1896[1]

“Now where is Zion?” penned Nancy Naomi Tracy, the only female to number among Joseph’s devoted cadre of electioneer missionaries who had stormed the nation in 1844. Sadly, when she raised that lament-tinged question in 1896, theodemocracy in Utah had already descended below the horizon of time. Two decades of relentless pressure from the federal government had backed the Saints into a corner. Polygamy was the bogeyman for Protestant, Victorian America, and “Mormon Theocracy” would no longer be tolerated in the United States. The former would be used to destroy the latter. When church president Wilford Woodruff sought heaven’s counsel in 1890, the answer was to end plural marriage. Moreover, the following year the church disbanded its political party (the People’s Party) and the Saints separated into Republicans and Democrats “like everyone else,” as President Grover Cleveland demanded. Compliance brought statehood in 1896, but theodemocractic Zion was the sacrifice—the ram caught in the thicket.

The aging electioneers lamented the loss of their dream. For decades following Joseph’s assassination, they had engineered theodemocratic Zion. They had worked wonders, serving as a critical component of the aristarchy of the Great Basin kingdom. Now that kingdom was all but gone. They had prepared to gather Israel out of the nations to a literal divine standard. And while many converts had indeed come from diverse countries, the nations and kingdoms of the world themselves had not crumbled as many had expected. Instead the United States had grown into a continental-sized world power, with only one small pocket of political and moral nonconformity—Utah.

Even as Zion’s hope faded, the dwindling number of electioneers remained true believers. John M. Bernhisel, who had been Joseph’s personal physician and confidant, became Deseret’s and Utah’s delegate to Congress from 1848 through the Civil War. All that time he had managed the difficult relationship between Brigham Young’s theodemocracy and the federal government. Historian Orson F. Whitney interviewed Bernhisel near the end of his life. Despite all the change occurring around him, Bernhisel looked forward to the day when every Saint “[would] work, not for his individual aggrandizement, but purely with an earnest desire to promote the interests of the Kingdom of God on the earth.” He then testified of Joseph, the Restoration, and Zion.

When Whitney asked Bernhisel if “he really believed such a Utopia would ever be realized,” the elderly electioneer got a gleam in his eye and responded with emotion, “As surely as the sun now shines in heaven.” That “enthusiastic fervor” so impressed Whitney that he could “vividly” recall that moment the rest of his life.[2] Nancy Naomi Tracy expressed her certainty of Zion’s triumph with the same celestial metaphor: Zion and its mission “are part of my makeup. . . . I am a firm believer of the prophecies,” she wrote. “I believe they will be fulfilled as sure as the sun shines by day and gives light.”[3] However, theodemocractic Zion had been diminishing for some time. The sun set gradually. After the arrival of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, Brigham Young, John Taylor, and Wilford Woodruff each in turn fought desperately to keep gentile influences at bay. Toward that end, they often appointed aged and experienced electioneers in vital religious, political, and economic positions throughout the territory. For a time, these efforts were somewhat successful. However, when the Supreme Court validated rigid anti-polygamy laws, dusk was at hand. The dream of Zion protected by a theodemocratic government that would rule not just the Great Basin but also eventually all the world passed into darkness. It would have to await the dawn of another day.

The Setting Sun

The completion of the transcontinental railroad on 10 May 1869 was a portent of difficult times ahead. Brigham understood that the railroad would bring to Zion a massive influx of “gentiles” whose different values and beliefs would create tensions with the Latter-day Saints. Seeing the coming storm, Brigham reconvened and reconstituted the Council of Fifty in 1867, a move that included the addition of electioneers Robert T. Burton, Edward Hunter, Abraham O. Smoot, and Hosea Stout.[4] The council created Schools of the Prophets throughout the territory. Composed of the leading high priests in each settlement, these mini-Councils of Fifty discussed “theology, church government, [and] problems of the church and community . . . and [had] appropriate action taken.”[5] Up until the mid-1870s, when these schools were dissolved, electioneers had a governing role in them. They acted to secure their communities economically. Following the example of electioneer apostle Lorenzo Snow’s work in Brigham City, they created economic cooperatives in order to limit financial interaction with outsiders. They controlled the flow of merchandise into Utah by creating Zion’s Cooperative Mercantile Institutions (ZCMI). For nearly a decade, the schools functioned successfully as a new level of theodemocracy.

After the national financial panic of 1873, Brigham created radical communal economic efforts called “united orders.” Within a year, 150 existed throughout the territory. After Brigham’s death in 1877, John Taylor replaced the failing orders with “Zion’s Boards of Trade.” Like the Schools of the Prophets, the boards were governed by the religious, political, and economic leaders of each stake in the Great Basin. At each semiannual conference, Taylor and other leaders instructed the boards on how to improve the economic situation of the Saints. By 1884 these boards had succeeded in increasing production and employment with regulated competition. Integrating industry, crafts, and agriculture, the church was closer to its goal of economic independence than at any time in its fifty-year history.[6] In all of these cooperative economic initiatives, electioneer veterans filled a majority of the leadership roles.

Within a decade, however, all this success would end in ruin as the United States government launched an offensive against the church. The intense prosecution of polygamy, what the Saints called “the Raid,” was the culmination of decades-long political pressures within and without the church. More than a thousand Latter-day Saint men were convicted and jailed in these raids. Many leaders, including electioneers, went into hiding to escape prosecution. At the same time, communal economic progress faded with the resultant loss of leadership in towns and cities across the Great Basin.

In 1870 disaffected Latter-day Saint merchants and intellectuals joined a growing number of gentiles to create the Liberal Party. In response church leaders created the People’s Party. The Liberals’ first triumph was recruiting electioneer apostle Amasa M. Lyman. The Quorum of the Twelve had already dropped him in 1867 for teaching “spiritualist” doctrines and denying Jesus Christ’s atonement. But hearing of Lyman’s commitment to the Liberals, the Twelve and First Presidency excommunicated him. To ensure that ruling majorities of Latter-day Saint men continued in the governments of Utah, the legislature followed Wyoming’s recent example of enfranchising women, doubling the Saints’ advantage. In elections for seventeen years, the Liberals had only one victory—Tooele County from 1874 to 1878—because gentile miners outnumbered Latter-day Saints there at that time.

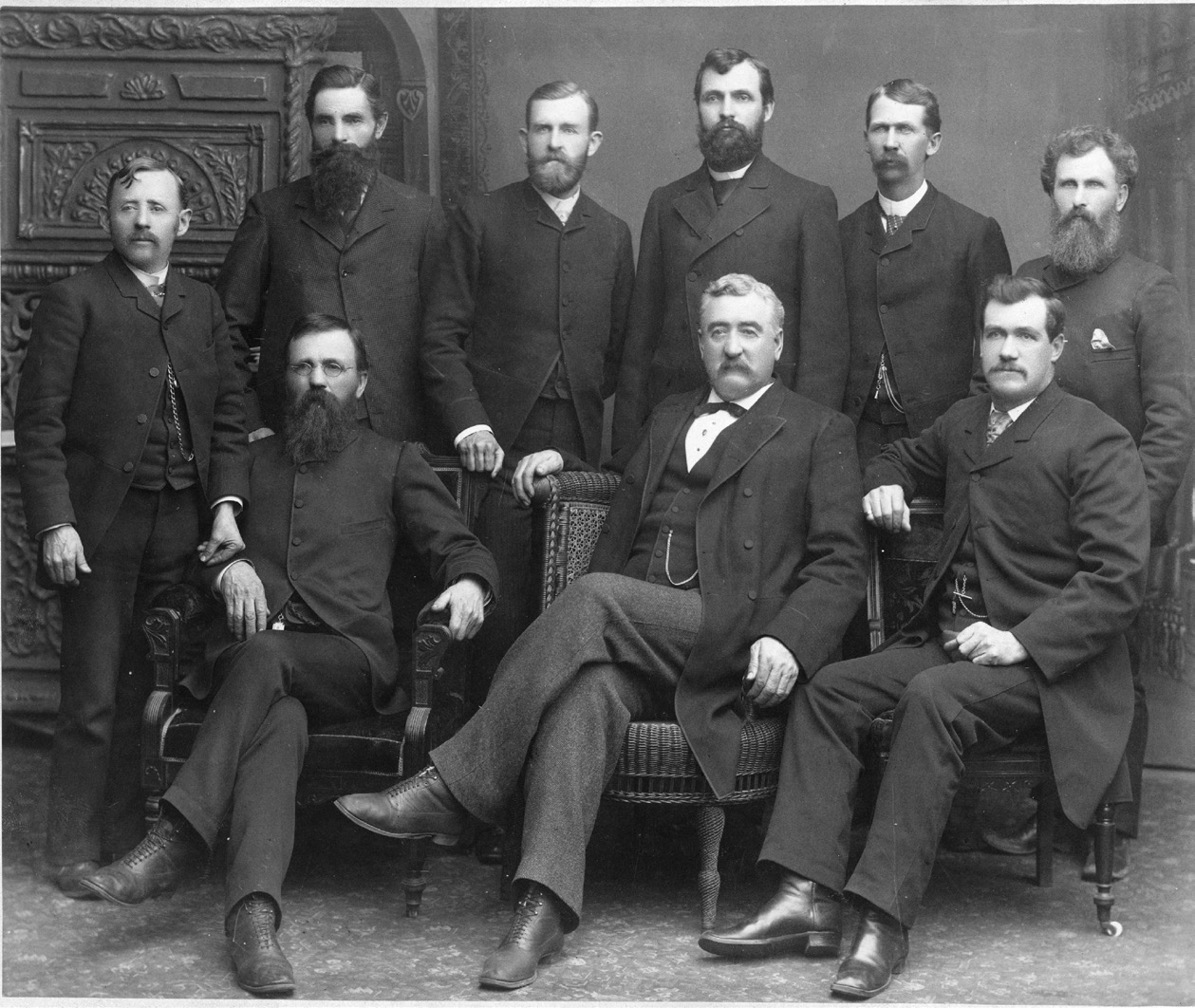

Municipal Officers of Ogden, Utah, 1889. At the height of anti polygamy persecution in 1889, the people of Ogden elected Liberal Party officers for the first time. The same would happen in Salt Lake City the following year. 1889 photo by the Adams Bros. courtesy of Church History Library

Municipal Officers of Ogden, Utah, 1889. At the height of anti polygamy persecution in 1889, the people of Ogden elected Liberal Party officers for the first time. The same would happen in Salt Lake City the following year. 1889 photo by the Adams Bros. courtesy of Church History Library

However, Liberal eyes were always on Ogden and Salt Lake City, Utah’s biggest cities and railroad centers with large gentile populations. As mentioned earlier, to ensure that Ogden did not fall, Brigham sent electioneer apostle Franklin D. Richards to Weber County,[7] where he served in church and political offices of influence. He installed electioneer colleague Lorin Farr as leader of the Ogden School of the Prophets. Richards and his counselors became the Weber County Central Committee of the People’s Party. For nineteen years they successively foiled Liberal aspirations.

However, in 1889 the Liberals took Ogden, and then Salt Lake the following year. This was possible because intense prosecution of polygamists disenfranchised tens of thousands of Latter-day Saint voters. The Poland Act of 1874 transferred all civil and criminal cases to federal judges and away from Latter-day Saint probate judges (many of whom were electioneer veterans). Church leaders appealed to their First Amendment right to exercise freedom of religion, but the Supreme Court ruled against them. Yet proving bigamy in court was problematic because polygamous women refused to testify against themselves. Then came the Edmunds Act of 1882 that defined bigamy as cohabitation, making conviction easier. Anyone found guilty paid stiff fines and was disenfranchised and imprisoned. A new federal commission oversaw all elections and interpreted polygamous belief alone as bigamy. The first year saw twelve thousand Latter-day Saint men and women disenfranchised. After another test case in 1885 went against the church, full-scale prosecution began, netting more than a thousand convictions. Many surviving electioneers were convicted and imprisoned.[8] Church leaders, including electioneers, went into hiding. An underground network of Saints concealed their leaders, safely moving them from location to location.[9]

President John Taylor remained undaunted. Still carrying a musket ball in his leg from Joseph’s assassination, he did not wilt in the face of the church’s enemies. In 1880 he recalled the Council of Fifty and replaced twenty-two deceased men (seven of them electioneers) and released five others (four of them electioneers) owing to age—actions showing that time had diminished the electioneers’ four-decade influence. Thirty-three new men entered the council. Only one, Lorin Farr, was an electioneer. However, sons of electioneer veterans Franklin D. Richards, Amasa Lyman, Jeremiah Hatch, Jedediah Grant, and David Cluff became members, signaling a new generation of electioneer influence.

Despite the efforts of the reconstituted Council of Fifty, anti-polygamy legislation was too powerful to counter. With leaders on the underground, administration of the church was severely disrupted. With electioneers and other church leaders not able to hold public office, the Zion trade boards they chaired collapsed. Yet, defiant like their prophet, they chose to continue in plural marriage. The exception was Franklin D. Richards. With the First Presidency in hiding and fellow apostles in prison or on the underground, Richards, by assignment, became the public face of the church by conforming to the law. He resided with only one wife while financially supporting his others. This arrangement allowed him to publicly transact church business and to project to church members that the leadership was still in control.[10]

Taylor remained resistant and in hiding until his death in 1887. He spoke and wrote of the confrontation in apocalyptic tones. He and many Saints believed that the second coming of Jesus Christ might occur in 1890.[11] They saw the persecution over plural marriage as but the final test of their faith. More than four months before Taylor died on 25 July 1887, the Edmunds-Tucker Act took effect. It dissolved the church as a corporate body, divested it of property, disbanded the Perpetual Emigrating Fund, abolished women’s suffrage, and created an anti-polygamy test oath to vote, hold elected office, or serve on juries. The federal government had taken off the gloves to destroy the political and economic power of the church. Disenfranchised, the People’s Party lost the Ogden elections in 1889 and the Salt Lake City elections in 1890. Additionally, in May 1890 the Supreme Court upheld the Edmunds-Tucker Act. Federal officials publicly stated they would go after the church’s temples.

In this context, the new president of the church, Wilford Woodruff, released what became known as the Manifesto. Fearing the loss of the temples and the cessation of saving ordinances, he prayerfully received a revelation for the church to cease the practice of plural marriage. In the October conference, church members sustained the action. The church lay decimated, no longer protected by theodemocratic governance. Woodruff looked for political deliverance from federal oppression through obtaining statehood. The cost was political unity.

In 1891 church leaders agreed to disband the People’s Party and encourage members to align with either the Republican or Democratic parties. To ensure compliance, some local leaders even split their congregations in half in order to assign equal numbers to each party. Certainly the transition was rocky. While most of the hierarchy aligned with the Republicans, President B. H. Roberts of the Seventy and Moses Thatcher of the Twelve ran as the Democratic nominees for the US House of Representatives and Senate, respectively, in 1895. Both lost. The First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve (which included electioneer apostles Lorenzo Snow and Franklin D. Richards) issued the Political Manifesto that same year. It required general authorities to receive permission from the First Presidency before running for office. Roberts grudgingly signed it, while Thatcher refused and was dropped from the Twelve. This was a dramatic change from the decades when apostles were automatically elected to high government positions.

By the time Utah gained statehood in 1896 with the backing of national Republicans, gone was unity in politics. Gone also was theodemocracy as a prelude to and bulwark for a Zionlike society. Socially, the practice of plural marriage was over. Economically, church businesses were in shambles. Plans of financial unity and self-sufficiency had vanished into a whirlpool of immense debt. The dream of Joseph’s theodemocratic Zion had slipped away.

Nancy Naomi Tracy—the Lament of Theodemocratic Zion

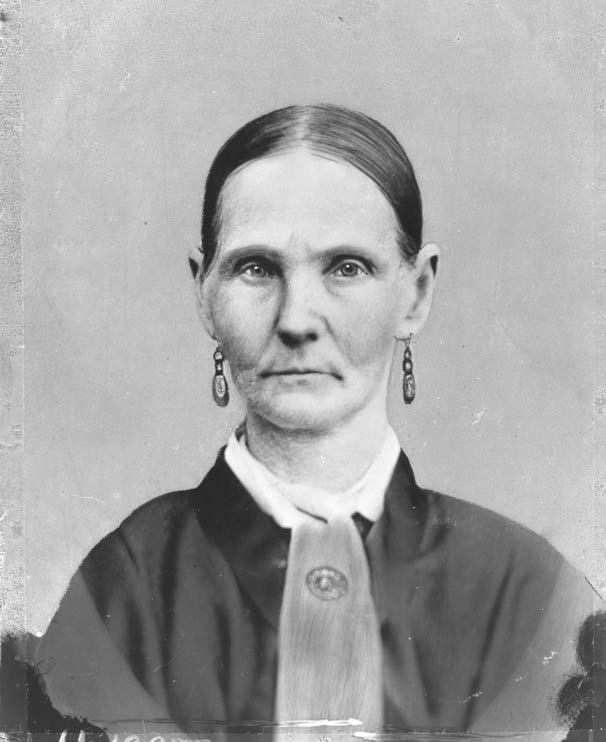

Living electioneers like Nancy Naomi Tracy struggled with the lost Zion. In 1896 she wrote in her journal, “We are told to be united, for in union is strength. Are we united? . . . What does it all mean?”[12] Her questions reflected the reactions of many of her surviving comrades. Nancy was born and raised in Jefferson County, New York, becoming well educated by sixteen. She married Moses Tracy in 1832. Two years later the young couple converted to the church and moved to Kirtland to join the Saints. They experienced the persecutions of Ohio and Missouri. They knew Joseph intimately, once giving him all the money they possessed. In Nauvoo, Nancy became a leader in the newly formed Relief Society and taught school while Moses worked as a carpenter and merchant assistant.

When Moses was appointed to electioneer in New York, Nancy convinced him to ask Joseph if she too could go. Not only was the answer yes, but knowing of Nancy’s education and oratorical gifts, Joseph told Moses that Nancy “would prove a blessing to him.”[13] The small family of four made their way to Sackett’s Harbor, New York, arriving in three weeks. They visited their families and former friends, teaching them the gospel and using Views to advocate Joseph for president. They then continued to Ellisburg, the location of Moses’s assignment, where Naomi stood side by side with her husband in preaching and electioneering. It was there that they heard of Joseph’s death.

Nancy Naomi Tracy, the lone female electioneer in 1844, lamented in 1896 the passing of the theodemocratic Zion that she and her peers had labored a half

Nancy Naomi Tracy, the lone female electioneer in 1844, lamented in 1896 the passing of the theodemocratic Zion that she and her peers had labored a half

century to produce. Portrait ca. 1860s courtesy of Church History Library.

When they returned to Nauvoo, their two-year-old passed away and was buried next to his brother who had died three years earlier. After receiving their temple ordinances, the Tracys fled Nauvoo and clung to life for three years in Winter Quarters. In 1850 they finally immigrated to Utah and settled in Ogden. In 1856 their eldest son, Mosiah, left the family and the faith, never to be seen again. Moses died the following year after a long bout of illness. A forty-two-year-old widow, Nancy worked her small farm to support her seven children. In 1860 she plurally married her deceased husband’s brother Horace Tracy. She lived out her life in Weber County, proudly seeing her sons serve missions and sorrowfully abiding the time that some of them were imprisoned for plural marriage.

Viewing her dream of theodemocratic Zion slipping away, she questioned “the divisions and strife in the political field: some for one party and some for another.” She lamented this lack of unity and its associated perils, believing the Saints “would be the only ones that would hold the constitution together after our enemies had torn it to shreds.” Nancy declared “that the crisis is at our doors” and that “the time is not far distant when the Kings of Kings will come and set up his own government.” Her undying loyalty to Joseph’s vision of theodemocratic Zion did not square with the new politics of Republican-Democrat schism. She longed for a future day when the Saints again “all with one accord will vote the same ticket.” While firmly believing that God was still directing events, she believed that he was not pleased with the partisanship all around her. Such a future, she believed, “certainly will try the Saints to the heart’s core and is altogether of a different nature from the persecutions in the early days of the Church.”[14]

She, her husband, their family, and the wider community of electioneers had sacrificed everything to build up the political kingdom of God. What would be harder, she pondered—the persecutions of the past or watching Zion wane and disappear? She vented her frustration at the “gentile world,” whose laws have not “allowed [the Saints] the liberty of conscience which other people have enjoyed and which the Constitution guarantees for us to worship as we please.” However, she declared, “This kingdom will roll on and eventually triumph over all others.” Such thoughts gave her “consolation and satisfaction to know that we shall eventually become the head and not the tail.” Envisioning the theodemocratic Zion she had spent half a century trying to achieve, she penned for posterity, “This is worth living for, and, if needs be, to die for.”[15]

Nancy Naomi Tracy died on 11 March 1902, the fifty-eighth anniversary of the organization of the Council of Fifty. Her words express the shock and disbelief that surviving electioneers felt upon seeing all they had built begin to crumble and vanish. Gathering to Zion, theodemocracy, plural marriage, and economic unity had all ceased. Although millennial fervor still burned in the hearts of Nancy and others, the second- and third-generation Latter-day Saints were adjusting to a new reality. What prominently remained of Zion were living prophets and temple ordinances sealing families eternally. Tellingly, in Nancy’s words, those themes shared equal time with her discontent over losing Zion. The church’s unique experience in American history was dropping below the horizon. Soon the term kingdom of God would come to mean only the ecclesiastical structure of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and not the theodemocratic Zion of the faith’s first generation of earnest believers.

The 1893 World’s Fair and the Vanishing Frontier

Amid this transition, church leaders attended the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago, Illinois. It provided an opportunity for Latter-day Saints to interact with the rest of America. The Utah Territory display was given a prime location, and tens of thousands of visitors walked past it each day. In every detail, church leaders orchestrated a softening of the controversial past of the church. While in some respects it worked, the results were mixed. The ecumenical Parliament of Religions refused to include the church or even a Latter-day Saint delegate because the church and its people were considered “un-Christian.” Conversely, the Mormon Tabernacle Choir took second prize, marking the beginning of America’s love affair with it. The church, stripped of its political, social, and economical interests, retained its core mission of proselytizing and administering priesthood ordinances. Church leaders understood that continuing caricatures of the Saints would impede that mission. Such prejudice had to be overcome, and that could happen only through interaction with wider America. The exposition was a perfect place to begin and foreshadowed two decades of mixed reception from fellow Americans.

In 1893 the Parliament of World Religions refused to allow a Latter-day Saint delegate, highlighting the struggle of the church to gain acceptance. Photo of the convened parliament at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition courtesy of the Council for a Parliament of the World’s Religions.

In 1893 the Parliament of World Religions refused to allow a Latter-day Saint delegate, highlighting the struggle of the church to gain acceptance. Photo of the convened parliament at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition courtesy of the Council for a Parliament of the World’s Religions.

At the exposition, the soon-to-be famous historian Frederick Jackson Turner presented his landmark paper, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” at a meeting of the American Historical Association there. Turner’s ideas became the starting point for a century of portraying the American West, the American experience, and American exceptionalism. He used the 1890 census’s declaration that a discernible American frontier no longer existed to create an epic narrative of the frontier as the defining feature of American history. For Turner, the West was where eastern Americans and emigrants left civilization for cheap land and freedom. The ascent back to civilization created a unique American people—doggedly independent, pragmatic, and democratic. As the frontier receded, in its wake society was reborn as distinctly American in thousands of towns. For Turner this distinct American process created endless opportunities for social mobility.

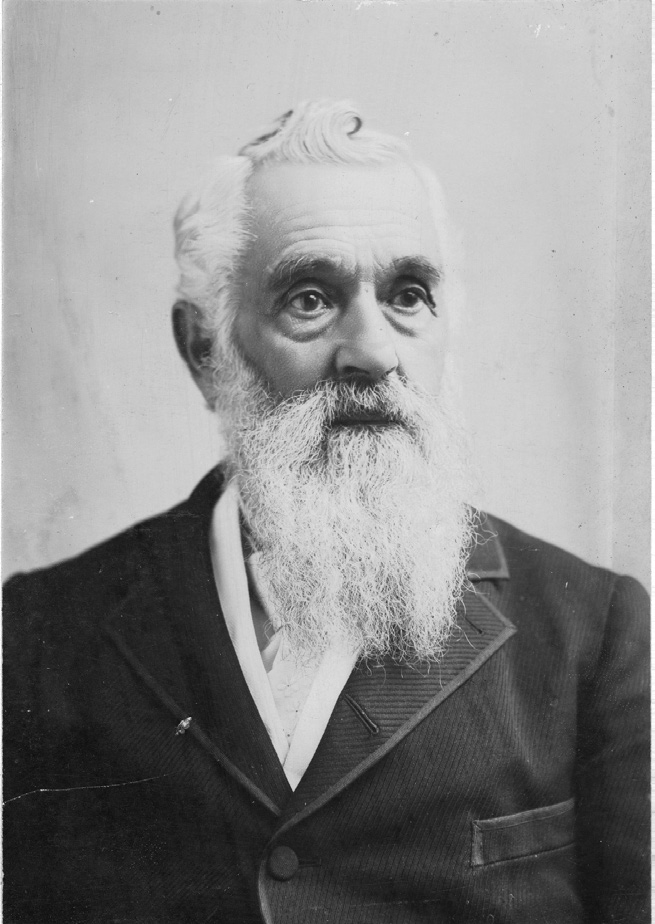

Lorenzo Snow, First and Exemplary Electioneer

Among the church’s delegation at the 1893 exposition was Lorenzo Snow—the first electioneer missionary, then-current president of the Twelve, and future church president. While there is no record of any Latter-day Saint in Turner’s audience that day, let alone an electioneer, what might Snow have thought of Turner’s thesis? In many ways Snow would have disagreed. Turner’s assertions were certainly not the electioneers’ experience on the frontier. They had not moved from the East to Missouri in search of inexpensive land, but rather according to a sacred geography. Their motive was neither land ownership nor financial independence, but to unitedly build a Zion society in the Missouri, Illinois, and Utah frontiers. They arrived in the Western frontier actually expecting less independence financially, spatially, and even politically than what their fellow Americans enjoyed. This was because Zion meant a commitment to sharing economic resources rather than competing to accumulate them. It also required a united people deferential to ecclesiastical leadership rather than beholden to governance resulting from contested elections. What’s more, the frontier for them was a sacred locus for the gathering of the house of Israel, the building of Zion and a refuge from God’s impending vengeance, and the welcoming of Jesus Christ.

The first and later the most recognizable electioneer, Lorenzo Snow personified the electioneers’ amazing post-1844 campaign

The first and later the most recognizable electioneer, Lorenzo Snow personified the electioneers’ amazing post-1844 campaign

success in becoming a key part of theodemocratic Zion. Photo of Snow circa 1893 by Sainsbury and Johnson courtesy of Church History Library.

Snow would likely have challenged Turner’s argument that taming the frontier created a unique American people who were fiercely independent, wary of hierarchy, and democratically participative. What Snow experienced on the frontier was entirely different. The success of Zion lay in in its cooperative nature. Instead of a loose concentration of family farms that developed into a village, the Saints erected towns and cities with temples at their cores. Whereas Turner’s frontier encouraged individuals to jostle for economic security and political position, the Saints cooperated economically and chose to be politically subservient to religious authority. Recalling Hawn’s Mill, the gang rape of his sister, Carthage, and the Raid, Snow would have vehemently disagreed with Turner’s assertion of pluralistic frontier democracy because Latter-day Saints so often experienced persecution and violence from their neighbors on the frontier. Thus they were a counterculture movement in America taking “flight from American pluralism.”[16]

The frontier in Utah represented something more. For a time it was a protected, isolated space in which to fully implement Joseph’s Zion with its thoroughly un-American traits. These counterculture characteristics of the church—namely, combining of church and state, collectivist economic policy, and plural marriage—were not created by interaction with the frontier. Rather, church leaders brought those values and institutions with them from Nauvoo. Their genesis was Joseph and his vision of Zion, not the frontier experience. Indeed, the fact that the Great Basin lay far beyond the fringe of the American frontier gave church leaders and their electioneer associates the chance to fully implement “Joseph’s measures.”[17]

Yet, ironically, Turner’s quixotic and oft-criticized vision of social mobility on the frontier perhaps found its most concrete expression in the electioneers’ experience. Overall, it was the electioneers who experienced significant social mobility in the Great Basin. As the very first electioneer, and one who reached the highest echelon of leadership in the church, Lorenzo Snow furnishes an illuminating case study. He was born in Ohio to a common farm family. He studied books and valued education. His older sister Eliza joined the Saints and often wrote to Lorenzo about her faith. His visceral reaction was to trust in education and say “good-bye to all religions.” However, the church intrigued him, and after some investigation he joined in 1836. He longed for a spiritual experience to confirm his intellectual choice, and upon receiving it he immediately set out on proselytizing missions to Ohio and later to Kentucky. Snow continued to teach school during the winters until he was ordained a high priest and called on a mission to England. There he honed his organizational skills, presided over the several hundred Saints in London, and even presented a leather-bound copy of the Book of Mormon to Queen Victoria. He returned to Nauvoo in the spring of 1843, at the head of several hundred British converts.

In the April 1844 church conference, Snow “received an appointment by the Twelve to form a political organization throughout the state of Ohio for the promotion of Joseph for the Presidency.” Snow left for Ohio on the steamboat Osprey—the first electioneer to embark. He recorded, “[I] delivered . . . the first political lecture that was ever delivered to the world in favor of Joseph for the Presidency.”[18] As mentioned earlier, he organized an effective electioneering corps in Ohio that was in full swing when he heard rumors of Joseph’s assassination. Snow providentially found fellow electioneer Amasa Lyman, who confirmed the news. “Struck . . . with profound astonishment and grief, which no language can portray,” Snow closed the campaign in Ohio and headed to Nauvoo. [19] He returned to teaching school and married his first wife. Church leaders were impressed by what he had done in Ohio. In 1845 they re-sent him to canvass the Ohioan branches for money to finish the temple. Snow wrote that the money “credited on my book [was] about 300 dollars.”[20] That December, he married a second wife and received all the temple ordinances, including the second anointing.

In the westward trek, Brigham Young appointed Snow to manage the Mount Pisgah way station in Iowa, an immense responsibility for a young former schoolteacher. He excelled. Snow later traveled to Salt Lake City, and in February 1849 Brigham called him to the apostleship along with fellow electioneers Franklin D. Richards, distant cousin Erastus Snow, and Charles C. Rich. Within six months, he was in Italy opening that nation to missionary work. When he returned to Utah in 1852, Brigham assigned him to preside in Box Elder County. As the stake president, Snow built and led Brigham City in complete theodemocratic style. He created a successful economic cooperative that by 1875 was the pride of Utah, being an incredible 95 percent efficient. Financially unfazed by the Panic of 1873, the Brigham City cooperative instantly became famous, and journalists from throughout the country visited to report on it. Snow also profited from his community’s success. The 1870 census recorded six wives, four thousand dollars in real estate, and ten thousand dollars in personal wealth. Brigham used Snow’s model to create cooperatives and later united orders throughout the territory.

In 1885 during the Raid, Snow was arrested, fined, and sentenced to prison, serving eleven months. In 1889, with theodemocracy in its death throes, Snow became president of the Quorum of the Twelve. After the completion of the Salt Lake Temple in 1893, he became its president. The temple became the new “gathering,” the new locus of Zion as generational sealings began to replace the focus on a now-fading temporal Zion. Becoming president of the church in 1898, the first missionary of theodemocracy ironically inherited the church stripped of its political, social, and economic power. The church itself was in financial ruin from the anti-polygamy crusade that had escheated property and disrupted church businesses and finances. Snow preached throughout the Basin’s settlements, renewing the Saints’ commitment to tithing. It paid off. The church was out of debt in less than a decade, never to return. Zion’s identity changed from theodemocracy, a collectivist economy, and plural marriage to tithing, adherence to the Word of Wisdom, and generational temple work attendance.

Snow in many ways personifies the electioneer cadre, of which he is the most famous. He began as a young farmer with better-than-average education and no desire for organized religion. He had already begun a career in education when he accepted the restored gospel. Because Snow embraced Zion and demonstrated competence and unstinting loyalty and sacrifice, including in Joseph’s 1844 campaign, he did not remain a common teacher in Ohio. Instead he traveled all of Europe in the Lord’s service, met Queen Victoria, and—most significantly—received religious, political, and economic positions of authority over thousands and, ultimately, hundreds of thousands of fellow believers.

In sum, Snow excelled in all four spheres of influence in which the electioneers operated. In the religious sphere, he rose in trusted responsibilities and became an apostle within five years of his electioneering mission. Later he became president of the Quorum of the Twelve, and in 1898 he was elevated to president of the church. In the political sphere, the organizational skills and hard work Snow exhibited in directing Joseph’s campaign in Ohio soon found application in Utah. He served in the influential Council of Fifty and was a Territorial Councilor from 1852 to 1884 (an astonishing thirty-two consecutive years) and president of the Council for many of those years. In the social sphere, his religious and political positions required participation in plural marriage. True to the principle, he married nine wives and had forty-three children. In the economic sphere, he created opportunities that lifted his community and led to shared prosperity. Snow’s successful cooperative inspired economic revitalization throughout the territory and even garnered national attention. His wealth included large tracts of farmland, stock shares, and other personal assets in the tens of thousands of dollars. In short, Snow was not only the first but also the premier electioneer—one who reached pinnacles of religious, political, and economic power and influence still remembered today. Most of the other faithful electioneers accomplished much good in those same four areas and attained prominence in their own communities as well, though in varying degrees.

Through the lens of his experience, Snow, unlike his contemporary Frederick Jackson Turner, would have seen more than the closing of the frontier in 1890. It was also the end of the church’s Zion-driven, counter-American uniqueness that had been sheltered by that very frontier. The church’s escape from secular time and space was over. When a staunchly pious resistance failed to keep an encroaching American secularism at bay, or bring about hoped-for apocalyptic judgments attending Christ’s return, church leaders, including Snow, worked on accommodation with a society that had rejected them. With Snow and other church leaders at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, the new mandate to deemphasize certain aspects of the church’s uniqueness was just the beginning. Sadly, the curtain had closed for the time being on carrying out Joseph’s vision of theodemocracy.

Notes

[1] Tracy, Reminiscences and Diary, 53, 60.

[2] Orson F. Whitney, “John Milton Bernhisel,” History of Utah, 4:664.

[3] Tracy, Reminiscences and Diary, 53.

[4] See Quinn, “Council of Fifty,” 22–26; and Jedediah Rogers, Council of Fifty, 247–55. Seventeen new members were admitted. Eleven of the six were sons of pre-1844 apostles. Of the six others, four were electioneers.

[5] Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 245.

[6] See Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 349; and Ridge, “Closing of the Frontier,” 142.

[7] See Tullidge’s Histories, 2:315–16, 335.

[8] Electioneers who served prison sentences included, at least, Henry Boyle, David Candland, Edmund Ellsworth, Elijah F. Sheets, William R. R. Stowell, and Lorenzo Snow.

[9] In 1886 electioneer James H. Glines hid church president Wilford Woodruff in Vernal, 172 miles west of Salt Lake City. Then, after a short period, Glines drove Woodruff 400 miles to St. George. See Glines, Reminiscences and Diary, 61.

[10] See Talbot, Acts of the Modern Apostles, 157–69.

[11] See Doctrine and Covenants 130:14–17. Taylor and others interpreted these verses to mean that Christ could return in the eighty-fifth year of Joseph’s life, 1890.

[12] Tracy, Reminiscences and Diary, 53, 60.

[13] Tracy, Reminiscences and Diary, 27.

[14] Tracy, Reminiscences and Diary, 60–61.

[15] Tracy, Reminiscences and Diary, 60–62.

[16] See generally Hill, Mormon Flight from American Pluralism.

[17] See Davis Bitton, “Re-evaluation of the ‘Turner Thesis,’” 326–33.

[18] Lorenzo Snow, Journal, 48–49.

[19] Eliza R. Snow, Record of Lorenzo Snow, 80.

[20] Lorenzo Snow, Journal, 53.