Seeking “Power to Protect the Innocent”

Derek R. Sainsbury, “Seeking 'Power to Protect the Innocent,'” in Storming the Nation: The Unknown Contributions of Joseph Smith’s Political Missionaries (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 1‒30.

I am the greatest advocate of the Constitution of the United States there is on the earth. . . . The only fault I find with the Constitution is [that] . . . although it provides that all men shall enjoy religious freedom, yet it does not provide the manner by which that freedom can be preserved. —Joseph Smith, 15 October 1843[1]

Electioneer Experience: Robert and John Thomas. Robert Thomas was in Mississippi when he first heard that the prophet Joseph Smith was dead. He and his companion-cousin John Thomas, both in their early twenties, had been electioneering in Tennessee and Mississippi for two months. They had joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints only five months earlier, baptized by fellow electioneer Benjamin L. Clapp. Initially, Robert was wary of Clapp and his companions, believing them to be “deceivers.” [2] Yet he read the Book of Mormon and listened to the missionaries. Soon Robert chose baptism, which took place in a partially frozen pond. That cold, February night Clapp prayed for Robert to be able to speak in tongues, and he did so at that night’s meeting.

Just as Robert began to speak in tongues, two men arrived, intending to disrupt the gathering. Interpreting Robert’s words, a church member declared there were men prepared to violently end the meeting. The two visitors sat stunned. One slowly stood and stammered, “We came here tonight intending to break up this meeting.” Pointing at Robert, he continued, “Robert, I know him, and he could not talk in a new language if it was not of the gift of God.” The two men then requested baptism. Clapp was impressed with Robert and soon took him on a short but successful mission to Alabama. When the two missionaries returned to Mississippi, the Thomas families were preparing to move to Nauvoo, Illinois. They all took their first railroad ride to get to Vicksburg, Mississippi, where they boarded a steamboat, arriving in Nauvoo around mid-April. For four weeks Robert Thomas rented a room in Joseph’s Nauvoo Mansion.

Robert spoke daily with the prophet for a month, receiving a crash course on his new faith directly from its founder. Joseph and other leaders took notice of Robert’s spiritual and speaking talents. In May apostle Heber C. Kimball approached Robert and John Thomas and announced, “I want you two to go on a Mission.” They were directed to the Seventies Hall, where electioneer missionary Joseph Young ordained them seventies, and then Kimball told them to report to Abraham O. Smoot, president of the campaign in Tennessee. They boarded a steamboat headed back down the Mississippi and found Smoot in Dresden, Tennessee. Smoot assigned them to Huntington County, where they began preaching the gospel and electioneering for Joseph Smith. Although mobs threatened them and cold, wet nights without shelter weakened their bodies, they persisted in their difficult mission day after day, week after week.

* * *

What drove two young Southern men to preach and electioneer in the South for religious government and the abolition of slavery—tenets of Joseph’s presidential platform? In a nation founded on freedom of religion, why did these missionaries of an unpopular church advocate their leader and prophet for US president? The answers are not found in the Thomas brothers alone. Scattered across the nation, more than six hundred other electioneer missionaries were zealously promoting Joseph’s unique presidential campaign. Why did they choose to do so?

To understand Joseph’s presidential aspirations and the devotion of this cadre of electioneers, one must know something of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, specifically its founding narrative and the actuating doctrine behind its encompassing mission—to restore not only the true church of Jesus Christ but also the Zion kingdom destined to govern the world during the Millennium.

Church of Christ Restored

The Latter-day Saint movement began with Joseph Smith Jr., who was born on 23 December 1805, in Sharon, Vermont. His family eventually settled near Palmyra, New York, in the so-called burned-over district during the Second Great Awakening. Intense religious revivals there engulfed every family, including the Smiths.[3] Twelve-year-old Joseph was perplexed about which church to join. After two years of searching, he became convinced that he must ask God directly. The result of his prayer is known as the “first vision.” In this vision, Joseph testified, God and Jesus Christ appeared and forbade him to join any of the sects then on the earth. Three years later an angel named Moroni visited Joseph and told him that God had “a work” for him to do and that his “name should be had for good and evil among all nations, kindreds, and tongues.” Moroni added that “there was a book deposited, written upon gold plates, giving an account of the former inhabitants of this continent” and containing “the fulness of the everlasting Gospel.”[4] Joseph obtained the plates and in March 1830 published a translation of them entitled the Book of Mormon.[5]

On 6 April 1830, Joseph organized the Church of Christ in Fayette, New York. He dictated a revelation declaring he was to be “a seer, a translator, a prophet, an apostle of Jesus Christ, an elder of the church through the will of God.”[6] Thus the church was born with new, translated, ancient scripture and continuing revelation through the prophet. Missionaries with copies of the Book of Mormon began spreading the news of the restoration. Four missionaries journeyed to the western border of Missouri during the winter of 1830–31 and, along the way, converted many of Sidney Rigdon’s congregation near Kirtland, Ohio, doubling the church’s membership.[7] As part of this mission, they covenanted to place a pillar on the spot for the temple of the “New Jerusalem”—Zion. Although erecting the marker would wait a year, the idea of building a New Jerusalem—a city of Zion—consumed Joseph and the Saints.[8]

Latter-day Saint Doctrinal Basis of Zion

Zion is a biblical name for Jerusalem and her righteous inhabitants, and building a city of Zion in America—a “New Jerusalem”—was the primary impulse behind the Latter-day Saint movement. With the Book of Mormon and his own revelations declaring that Zion would be built before the second coming of Jesus Christ,[9] Joseph admonished the Saints to “establish the cause of Zion” and “move the cause of Zion in mighty power for good.”[10] He taught that Zion would be located “on the borders by the Lamanites.”[11] Zion was to be a refuge as God poured out wars, plagues, and destructions preceding the second coming. The marriage of the cause of Zion to the concept of the New Jerusalem concretized in the Saints’ minds. For the early Saints, Zion was not only a location in the western United States that was safe from the world’s imminent destruction, but also heaven’s great work of preparing the earth for the return of Jesus Christ.[12]

Further clarification came in revelations known as the Book of Moses. The antediiluvian prophet Enoch lived in a city known as the city of Zion. Its people were so righteous that “in the process of time, [that holy city was] taken up into heaven.” God also “called his people Zion,” making Zion not just a place but a people. Further, the revelation explained that Zion encompassed more than contemporary Christianity: “And the Lord called his people Zion, because they were all of one heart and one mind, and dwelt in righteousness; and there was no poor among them.”[13] Zion was to have a social component consisting “of one heart,” a political or governing component of “one mind,” an economic component of “no poor among them,” and a religious component of “dwel[ing] in righteousness.”

Another revelation required the Saints to gather to Ohio. To emphasize the centrality of unity in creating Zion, it declared, “Be one; and if ye are not one ye are not mine.”[14] Regarding this doctrine of gathering, Joseph later instructed, “What was the object of gathering . . . the people of God in any age of the world? . . . The main object was to build unto the Lord a house whereby He could reveal unto His people the ordinances of His house.”[15] Thus the temple became the earthly locus of Zion where heaven and earth literally met. Later the Saints learned that the temple was where they would make covenants to individually and collectively create Zion’s four components (religious, social, economic, political).

The concept of Zion in the revelations divided the world into two parts. The first was Zion and her grouped congregations called “stakes,” where Saints gathered to build up a Zion society.[16] They would receive knowledge and power in Zion’s temple and then go into the mission field (the second division of the world) to preach and make proselytes. These converts would, in turn, gather to Zion, help build it, and serve missions themselves. World renewal would come from Zion and her ever-expanding stakes. Thus, less than a year after its founding, the church’s primary aim was to gather converts and to become Zion—a people prepared for the second coming. Revelations associated with Zion laid the foundation for a communal economic system called the law of consecration. Joseph also received instructions outlining the familial patriarchal order, including the doctrine of eternal marriage and the principle of plural marriage.[17] Lastly, he received inspiration on establishing the political kingdom of God.

Zion was so central to what Joseph knew the restoration of Christianity to be that when persecution prompted the use of secret names in the original 1835 edition of the Doctrine and Covenants, Joseph chose the name Enoch—the prophet-leader of the original Zion. Of course, Zion with its peculiar social, political, economic, and religious ramifications was antithetical to the beliefs of fellow American citizens. In violent frontier America, this meant conflict almost anywhere the church bloomed. Thus the Saints of Joseph’s day, including most of the future electioneers, would flee persecution in Ohio and Missouri and start over again in Illinois.

Zion in Ohio and Missouri

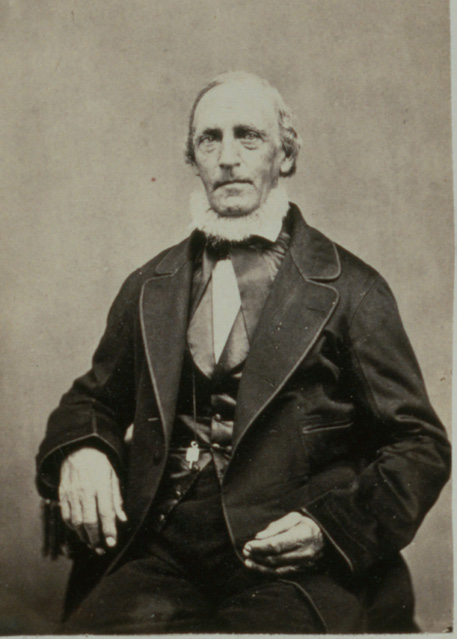

Early image of Lorenzo Snow,

Early image of Lorenzo Snow,

the first electioneer. Courtesy of

Church History Library.

Electioneer Experience: Lorenzo Snow. Lorenzo Snow’s encounters with persecution typified the experiences of many other electioneers during the first decade of the church. Twenty-one-year-old Snow initially scoffed when his older sister Eliza joined with the Saints in nearby Kirtland, Ohio. In 1836 he left Oberlin College “with disgust” and joined Eliza in Kirtland. Still skeptical about the church, he nevertheless enrolled in its Hebrew class in preparation to continue his education elsewhere. Instead Snow had a spiritual awakening and chose to unite with the Saints. He later penned, “I totally relinquished all my favorite ideas and arrangements of Classical Education [and] I took up my valise and went forth without purse or scrip to preach the Gospel.”[18]

Later, fleeing persecution, Snow departed for Missouri with his father’s family. Snow’s devotion to the church had grown in two years, owing in part to his having “witnessed very many marvelous scenes of the power of God in the Temple.” Now in Missouri he “stood with weapons in hand to defend his father’s house” from the gathering mobs. He would never use them; instead he was called on another mission, this time to Kentucky, Illinois, and Ohio. While he preached and for income taught school for a season, tensions in Missouri boiled over and mobs viciously attacked the Saints. Tragically, his adored sister Eliza was gang-raped and his family driven from the state. In a twist of irony, he learned of the expulsion by reading a letter by Eliza in a newspaper. Snow and thousands of other Latter-day Saints, including future cadre members, would be haunted the rest of their lives by the harrowing experiences they experienced at the hands of violent mobs.

* * *

The church’s experience from 1830 to 1837 centered on the towns of Kirtland, Ohio, and Independence, Missouri. Here the Saints received revelations that solidified church governance and learned doctrines that shaped belief and practice. Jackson County, Missouri, became the revealed location of Zion. Saints flocked there to receive stewardship inheritances and to build up Zion while seeking to become a Zion people.

Building Religious Zion

Latter-day Saints believed the authority to act in God’s name was available to all male congregants and that it derived directly from heavenly messengers. While Joseph and his scribe Oliver Cowdery translated the Book of Mormon in the summer of 1829, angels visited them. John the Baptist restored the “lesser priesthood” of Aaron. The New Testament apostles Peter, James, and John restored the “higher priesthood” of Melchizedek, an Old Testament priest-king. This system of priesthood had clear church-state undertones, a theme that Joseph fully developed in Nauvoo with temple ordinances. The Aaronic priesthood was a preparatory priesthood dealing with temporal matters and the ordinances of baptism and the sacrament (communion), while the Melchizedek priesthood included the authority to bestow the gift of the Holy Ghost and to direct the church by revelation. A revelation in 1830 named Joseph Smith “as first elder of this church” and Oliver Cowdrey as “second elder.”[19] Continued church growth led to additional revelations that created more priesthood offices necessary for governing the church.[20]

A bishop to manage temporal matters was the first new office.[21] Joseph soon ordained the first high priests, who were higher in authority than elders.[22] In 1832 the First Presidency became the highest presiding council of the church.[23] The first high council was called in 1834, consisting of twelve high priests.[24] A year later Joseph organized two other quorums of leadership. First was the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, modeled after the apostles of primitive Christianity. They were appointed as “special witnesses of the name of Christ” and served under the direction of the First Presidency. The other quorum was the Seventy, directed by seven presidents, to act under the direction of the Twelve.[25]

Kirtland Temple, ca. 1900. Photo by S. T. Whitaker. Temples and temple ordinances

Kirtland Temple, ca. 1900. Photo by S. T. Whitaker. Temples and temple ordinances

were at the heart of building Zion. Courtesy of Church History Library.

The combination of sacral priesthood and church government, though foreign to most other contemporary religions, became a pillar of the church. Ordinary men were considered worthy of power to stand in the presence of God and act with the authority of prophets of old. Such power was entrusted without consideration of economic or intellectual capacity. Men qualified for priesthood office because of their righteousness and loyalty. Another strength of the priesthood was its combination of hierarchical and democratic elements. Democratic features included its openness to all men, the naming of leaders as “presidents,” and the law of common consent, which required that priesthood officers be approved by church members. These were not elections but opportunities to publicly support the officers. Those selected by revelation were subject to God, not the people.[26]

The centrality of the temple to Latter-day Saint theology is best expressed by the Saints’ determination to build temples long before other religious buildings. The dedication of the Kirtland Temple was the pinnacle of religious Zion in Ohio. January–May 1836 was the greatest era of spiritual manifestations in Latter-day Saint history. Church leaders and members saw visions of Christ, angels, and prophets. Joseph presented the quorums of the priesthood for approval in order of authority, thus cementing church leadership. On Easter, 3 April, Joseph recorded that Jesus Christ appeared to him and Oliver Cowdery, accepting the temple. Then Moses, Elias, and Elijah restored priesthood keys to gather and seal God’s children, thereby “turn[ing] the hearts of the fathers to the children, and the children to the fathers.”[27] These priesthood keys were essential to direct the gathering to temples, the heart of Zion, where the ordinances of salvation could be performed.[28]

Building Social Zion

By 1831 Joseph had learned that the restoration of Zion would include the social order of the biblical patriarchs. Adam, Enoch, Noah, and Abraham were all part of this system of organizing and governing families and nations by the priesthood authority received from sacred covenants with God. Couples were promised an eternal union and endless posterity, perpetuating God’s covenant. Joseph eventually understood the Saints would make the same covenants and receive the same blessings. A corollary to this doctrine was plural marriage, as practiced by some of the patriarchs and prophets. Joseph later recorded a revelation stating that Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and others took additional wives who “were given unto [them], and [the patriarchs] abode in my law.” Plural marriage would be part of the “[restoration] of all things.” [29]

Building Economic Zion

In early 1831 Joseph organized Zion economically in Jackson County after receiving revelations detailing the law of consecration. The bishop received members’ consecrations of property and possessions and then assigned stewardships for each family or individual. The size of the stewardships depended on the circumstances, wants, and needs of the families. Relative economic equality would bring unity, and unity would bring Zion. In 1833 Joseph sent the leaders in Missouri a plat for the city of Zion. At the center of the city was space for “temples.”[30] Though other contemporary utopian groups envisioned communitarian towns, Joseph’s was unique. There was no civil government or commerce at Zion’s core. It was to be literally a holy city, where every building would display the words “Holiness to the Lord.”[31] Although this plat was never implemented in its particulars, Joseph later utilized its principles for laying out settlements in northern Missouri and Illinois.

The Saints’ expulsion in the winter of 1833–34 destroyed hopes for consecration in Jackson County. In 1836 in Ohio, Joseph and others created the Kirtland Anti-Banking Safety Society to stimulate commerce. However, persecution, the national economic panic of 1837, and poor management led to its collapse and with it the collapse of the local economy. Many blamed Joseph for their financial problems, accusing him of being a false prophet. Economic Zion had been a disaster in both states.[32]

Building Political Zion

As early as 1830, Joseph talked about establishing an actual kingdom of God on earth. In fact, the Saints felt more like citizens of Zion than citizens of the United States (although in Ohio and Missouri they, like their fellow Americans, exercised their right to act individually in politics). Complicating matters in Missouri, however, was the fact that most Saints came from the North while most “old settlers” were transplants from the Deep South. The Saints’ increasing numbers stirred the fears of the settlers, many of whom saw the Saints as religious fanatics. Aggravating the situation was the Saints’ peculiar belief that the neighboring American Indians were among God’s covenant people. Some Saints boasted that thousands of converts, including Indians, were coming and that the “Gentiles” (non-Latter-day Saints) would be destroyed when Zion was established.

The brewing conflict erupted over slavery. A misunderstanding convinced the Missourians that the Saints were inviting free blacks into their slave state. Leading citizens organized in July 1833 and signed a manifesto demanding the Saints leave the county. The meeting quickly became a mob that destroyed the Saints’ press and tarred and feathered two leaders. The vigilantes forced local church leaders to sign an agreement. To speed the process, they turned to further violence in October. Light casualties occurred on both sides. Local officials called out the militia, giving legal sanction to their deeds. They confiscated the Saints’ weapons and forced them out of the county, destroying their homes, farms, possessions, and animals. The refugees fled during the height of winter, crossing the Missouri River into Clay County.

Encouraged by a revelation, Joseph and the Saints turned to the government for redress. It implied that if appeal to government failed, the Saints might have to respond with force.[33] Yet petitions to local government officials and judges were ineffective because most of them were leaders of the mob. Fearing civil war, Missouri’s governor refused to help the Saints. When President Andrew Jackson and other federal officials also denied the Saints’ petitions, a new revelation authorizing an army was not far behind. In February 1834, the high council sanctioned Joseph’s determination to “redeem” Zion and named the prophet “commander-in-chief of the armies of Israel.”[34] He was to recruit an army to march to Missouri and return the exiles to their lands. Known as the Camp of Israel, and later Zion’s Camp, this group of men had an important impact on the church’s future.[35]

The story of Zion’s Camp is one of sacrifice, futility, and leadership development. The camp numbered more than two hundred. At the news of their approach, mobs reorganized in Jackson County, burned the remaining Latter-day Saint homes, and prepared for confrontation. Negotiations to restore the refugees to their lands proved fruitless. Surprisingly, Joseph dictated a revelation chastising the Missouri and other Saints for their selfishness and disobedience. It also stated that “mine elders should wait for a little season, for the redemption of Zion.”[36] Within days, Joseph disbanded the camp. Although Zion’s Camp failed to restore the Saints to their lands, the men’s experience with Joseph and one another prepared some for future leadership. Joseph judged the men who had volunteered at the risk of death and remained faithful to have passed a critical test, qualifying them for increased priesthood office. Back in Ohio, eight of the Twelve Apostles and all the Seventy were chosen from Zion’s Camp’s ranks. A decade later, Joseph’s presidential campaign would offer similar opportunities for the electioneer cadre.

The Saints’ experience in Ohio ended in religious schism, economic collapse, and refugees retracing the steps of Zion’s Camp to Missouri. In 1837 apostates created a separate church. After failed attempts at reconciliation, church leaders excommunicated the dissenters. By the end of the year, 10 to 15 percent of members had withdrawn from the church.[37] Lawsuits and mobs hounded Joseph and others in Kirtland, forcing them to flee to Missouri. The remaining loyal Saints soon followed their leaders west.[38]

Zion Flees Missouri—1838

Before becoming an electioneer,

Before becoming an electioneer,

Levi Jackman experienced the horror of the Missouri

persecutions. Sutterley Bros.

photo ca. 1865–73 courtesy of Church History Library.

Electioneer Experience: Levi Jackman. Cadre member Levi Jackman experienced the crucible of Missouri. His family was baptized in 1831 and moved to Independence, Missouri, in 1832. Mobs drove them and thousands of others out of the county the following year. But Jackman did not go quietly, repeatedly firing his rifle to defend his family. In 1834 Joseph chose Jackman to serve on the newly formed Missouri high council. Eventually, Jackman settled near the settlement of Far West, becoming a justice of the peace. However, the Mormon War of 1838 changed everything. His family, again homeless and suffering the bitterness of winter, stumbled across Missouri to Illinois. The next year, Jackman and hundreds of others swore affidavits against Missouri. He reported $1,825 of lost property and other damages. He would never receive a penny. Jackman’s dream of a heavenly Zion in Missouri ended in nightmare, one shared by all Missourian Saints.[39]

* * *

From 1836 to 1838 the Saints in Missouri tried to create Zion in newly formed Caldwell and Daviess Counties. Internal and external threats made the attempt a short, futile one. Disaffected leaders joined with external enemies to drive the Saints from the state. Religious, economic, and political differences stoked the simmering conflict that saw Saints killed, their women raped, and their property stolen or destroyed. Once again, they limped away as exiles—this time to Illinois.

Many Missouri church leaders became disaffected in 1838. The high council, including Levi Jackman, excommunicated most of them, even assistant president of the church Oliver Cowdery. Cowdery’s response captured the intensity with which some Saints struggled to reconcile their beliefs with Zion’s social, economic, and political demands: “I will not be influenced, governed, or controlled, in my temporal interests by any ecclesiastical authority or pretended revelation whatever, contrary to my own judgment.”[40]

On Independence Day 1838, Sidney Rigdon of the First Presidency delivered an emotional oration warning that the Saints would fight rather than suffer further persecution. “It shall be between us and them a war of extermination,” he declared.[41] Some Saints proudly published and foolishly distributed copies of the speech. These harsh words, though spoken in self-defense, were inflammatory and, ironically, foundational to the events that drove the Saints from Missouri. Adding to the tension, 1838 was an election year. When some Saints tried to vote in Gallatin, Daviess County, enemies confronted and blocked them. A brawl ensued with injuries on both sides.[42]

Conflict spread. Missourians laid siege to the Latter-day Saint town of DeWitt, beginning “a war of extermination.”[43] Joseph appealed to Governor Lilburn W. Boggs for assistance. When Boggs replied that “the quarrel was between the Mormons and the mob” and that “we might fight it out,” the Saints chose evacuation.[44] Now emboldened, hostile forces marched toward Daviess County. Alarmed, the Saints mustered their own militia units. Because the enemy forces were themselves militia detachments of counties, a kind of militia civil war emerged. Sixteen years before Kansas was bleeding from violent confrontations over slavery, and twenty-three years before the massive bloodletting of the Civil War, Missouri was hemorrhaging.[45]

Two events turned public opinion and the government of Missouri squarely against the Saints. Disaffected former church leaders swore out affidavits that Joseph taught he was above the laws of Missouri and that the Saints would destroy their enemies. Concurrently, at the Battle of Crooked River, three Saints including apostle David Patten were killed and several wounded on both sides. Exaggerated, one-sided reports reached Boggs, who believed them. In response, he issued the infamous extermination order: “The Mormons must be treated as enemies and must be exterminated or driven from the state if necessary for the public good.”[46]

Even before word of the order reached Caldwell County, the deadliest event of the Mormon War occurred. At Hawn’s Mill, a mob killed seventeen Saints and seriously wounded thirteen others. Their brutality included murdering defenseless men and boys, even a ten-year-old. The massacre became forever burned in the psyche of Latter-day Saints as evidence of bigotry and persecution toward them.[47] A siege of Far West ended with the imprisonment of church leaders and the expulsion of the entire community from the state. Joseph and others, arrested on charges of treason against the state, remained prisoners through the winter of 1838–39. As spring began and the government could not build a solid case against the prisoners, public opinion in Missouri turned against Governor Boggs. While being transferred in April 1839, the prisoners were allowed to escape. They hastily joined the expulsed Saints in Illinois.[48]

Nauvoo: The New Zion

Electioneer Experience: John Tanner. Future electioneer missionary John Tanner followed Joseph Smith from Ohio to Missouri and then to Illinois. Tanner first encountered the church as a wealthy hotelier and landowner in New York. In 1832 two missionary brothers (and future cadre members) challenged Tanner, a devout Baptist, to read the Book of Mormon. Jared and Simeon Carter promised that if he read the book, his leg—long lame and afflicted with sores—would be made whole. Tanner read the book and believed it was true, and Jared Carter took him by the hand and commanded his leg to be healed. Tanner never used crutches again. The next day the Carter brothers baptized Tanner and his family. Tanner sold his vast holdings and moved to Kirtland. He gave Joseph much of his wealth to invest in the community and to build the Kirtland Temple. He marched in Zion’s Camp, lost the rest of his fortune in the collapse of the Kirtland Safety Society, and eventually fled to Missouri.

During the siege of Far West, a Captain O’Dell of the militia-mob struck Tanner in the head with his gun, cutting a seven-inch gash to the bone. Blood smothered his face in such an awful manner that his captors momentarily felt remorse. They left him with his family, who recognized him only by his voice. Later in the day the militia returned and arrested Tanner and his son-in-law Amasa Lyman (a future electioneer missionary). After being released for lack of evidence, Tanner rejoined his family in Illinois. For the third time in six years, Tanner reestablished himself in a new Zion community and, once again, prospered.[49]

* * *

Like John Tanner, future electioneer cadre members and other Saints looked for a new beginning in Illinois. Joseph became adamant about creating Zion; he was more motivated and focused than ever, realizing his teachings and actions could lead to his death. He understood that most Saints, let alone other citizens of the United States, were not ready for Zion, including some doctrines he shared only sparingly. “I never have had opportunity to give them [the Saints] the plan that God has revealed to me,” Joseph privately lamented.[50] In Nauvoo, he revealed doctrines and practices to trusted associates so that, should he die, they might give them later to the full church. Joseph realized that in order to build Zion within the borders of the United States, they needed government protection. This he vigorously sought from city, state, federal, and even international leaders.[51]

Convinced that good will toward the church existed outside Missouri, Joseph petitioned the federal government. When he met with President Martin Van Buren at the White House in late 1839, the president, not wanting to offend his political allies, was ambivalent to Joseph’s pleas. “Gentlemen, your cause is just,” Van Buren admitted, “but I can do nothing for you—if I do, anything, I shall come in contact with the whole State of Missouri.”[52] A Congressional committee dismissed the Saints’ petition for redress, suggesting they seek justice in the courts, an avenue that was already a dead end. Joseph was furious: “Is there no virtue in the body politic?”[53] Van Buren’s rebuff pushed the Saints politically into the arms of the Whigs. When Joseph returned to Nauvoo, he wrote to a friend that “the effect has been to turn the entire mass of people, even to an individual, . . . on the other side of the great political question.”[54] Though overwhelmingly Democrats, in 1840 the Saints voted as a bloc against Van Buren and for the Whig candidate William Henry Harrison—the eventual winner. As the Saints began to hold the political balance of power in eastern Illinois, both parties took notice.[55]

Joseph secured a charter creating the city of Nauvoo and used it as a wall of defense “to create and protect a city-state.”[56] The charter allowed for the concentration of branches of government, creating effective control by elected church leaders. The commissioned militia, the Nauvoo Legion, would serve as a defensive hedge against future mob actions.[57] Joseph saw these as necessary measures to protect the church from a repeat of what happened in Missouri. He stated, “The City Charter of Nauvoo is . . . for the salvation of the church, and on principles so broad that every honest man might dwell secure under its protective influence without distinction of sect or party.”[58] Joseph and other church leaders were elected to city offices. The election results showed how entwined church and state were. Half of the candidates received 100 percent of the vote and the others no less than 97 percent.[59]

To Thomas Sharp of nearby Warsaw, the Saints and their religion, charter, and militia seemed sinister. Correctly, he understood that the church was not just another Christian sect. What Latter-day Saints declared as the restored church of Jesus Christ and the establishment of Zion, Sharp viewed as a growing, dangerous, and un-American political empire cloaked in the guise of religion. He began a campaign in his newspaper, the Warsaw Signal, against Joseph and the Saints. Sharp was instrumental in forming the Anti-Mormon Party in Hancock County. The initial slate of candidates in that party defeated the Saints in the county elections. However, the continual influx of converts to the area would soon reverse the numbers.[60]

In fact, from 1839–41, missionaries in Great Britain netted thousands of converts. Many immigrated to Nauvoo following the 1841 First Presidency proclamation for all Saints to gather there. The promise was that “by a concentration of action and a unity of effort” they would finally see Zion built.[61] The revelation, naming Nauvoo as a “cornerstone of Zion,” commanded the Saints to construct a temple wherein the Lord promised to reveal necessary ancient ordinances.[62] Further, the church was to send a proclamation to the rulers of the world, giving notice that Zion was on the earth. Nauvoo was to be an “international religious capital.”[63]

During this time Joseph introduced ward units—ecclesiastical, geographic subdivisions of a stake that were overseen by a bishop. The bishops primarily governed in temporal matters and did not preside at sacrament meetings, although they occasionally called more traditionally religious meetings. The church’s adoption of the word ward, a contemporary term denoting a political and geographic subdivision of a city, furthered the idea of Zion as a merger of church and state.[64]

The relative calm in Nauvoo afforded Joseph the opportunity to teach doctrines and practices that he had not widely revealed about the patriarchal order of Zion. This included the principle of plural marriage, which he privately taught to the apostles and a few others. Like Joseph, they were emotionally torn as they attempted to reconcile their cultural monogamy with polygamy. The acceptance and practice of plural marriage became an intense spiritual struggle and, ultimately, a test of loyalty to Joseph.[65]

Theodemocracy and Aristarchy

In the spring of 1842 Joseph began to tie political Zion to theological salvation in what he later termed “theodemocracy, where God and the people hold the power to conduct the affairs of men in righteousness.”[66] In April Joseph began receiving revelations outlining the political kingdom of God that would create this theodemocracy.[67] He announced, “I have the whole plan of the kingdom before me, and no other person has.”[68] This was to be the government spoken of by the Old Testament prophet Daniel that “the God of heaven [would] set up . . . , which [should] never be destroyed . . . but . . . should consume all . . . kingdoms” and thus govern the earth during the Millennium—when “they [the Saints] shall be priests [and kings] of God and of Christ, and shall reign with him a thousand years.”[69] The revealed name for the government was “The Kingdom of God and His Laws, with Keys and power thereof, and judgment in the hands of his servants, Ahman Christ.”[70] Joseph’s incremental movement toward a presidential campaign and a theodemocratic Council of Fifty emerges when one connects the dots from the spring of 1842 to the spring of 1844, as will be seen.[71]

Some five months before the 1838 Mormon War in Missouri, Joseph issued a motto that crystallized his view of the political kingdom of God. Titled “The Political Motto of the Church of Latter-day Saints,” it declared in part, “All good and wholesome laws; and virtue and truth above all things / And Aristarchy live forever!!!”[72] Aristarchy—the core characteristic of what might be termed “political Zion”—referred to “a body of good men in power, or government by excellent men.”[73] An earlier revelation reminded the Saints, “Nevertheless, when the wicked rule the people mourn. Wherefore, honest men and wise men should be sought for diligently, and good men and wise men ye should observe to uphold.”[74] For Joseph the words good, excellent, honest, and wise were personified in men who had proved their faithfulness to the cause of Zion.

Joseph drew on aristarchic principle in March 1842 when he created the Nauvoo Female Relief Society, an organization that assisted the poor, raised funds for the temple, and watched over the women of the church. Joseph introduced the women to sacred doctrines related to future temple worship, declaring that their society “should move according to the ancient Priesthood.”[75] The Relief Society was a microcosm of aristarchic theodemocracy. Revelation designated officers chosen for their goodness or excellence, including loyalty to Joseph and the church. Once nominated, members then voted to sanction the appointments, the already-familiar practice of common consent. Leaders were to continue “so long as they shall continue to fill the office with dignity.”[76] In other words, good or excellent leaders were to remain in their offices as long as their righteousness, competence, and loyalty endured. Thus formed, the female presidency of the organization governed by revelation, not by constitution.

In Nauvoo Joseph introduced temple ceremonies over a two-year period. In part, these sacred ordinances prepared church leaders to rule in the coming kingdom of God. While the temple was being built, Joseph introduced the endowment ordinance in his red brick store to several trusted associates in May 1842. Initiates were promised that if they were faithful, they would eventually become “kings [and queens] and priests [and priestesses] unto God.”[77] Until his death in June 1844, Joseph administered the endowment to nearly one hundred loyal friends, male and female, calling them the “Anointed Quorum.” In May 1843 Joseph began sealing select couples into an eternal marriage covenant. The ultimate purpose of these ordinances was to bind disciples to God, husbands to wives, and children to parents ad infinitum in the patriarchal order of Zion. However, through these ordinances, Joseph also created the groundwork for a theodemocracy governed by an aristarchy.[78]

On the upper floor of his red brick store in Nauvoo, Joseph organized the Relief Society, introduced the endowment, led his presidential campaign, and directed the Council of Fifty. Photo attributed to B. H. Roberts, ca. 1886. Courtesy of Church History Library.

On the upper floor of his red brick store in Nauvoo, Joseph organized the Relief Society, introduced the endowment, led his presidential campaign, and directed the Council of Fifty. Photo attributed to B. H. Roberts, ca. 1886. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Joseph took another step toward theodemocracy just weeks after initiating the endowment. At the temple site he “addressed them [citizens of Nauvoo] on the principles of government at considerable length, showing that [he] did not intend to vote the Whig or Democratic ticket as such, but would go for those who would support good order &c.” Then the “meeting nominated candidates for Senate, Representatives, and other officers.”[79] Here was theodemocracy at work. The prophet, at the Saints’ most important religious space, nominated for political office those men he felt were faithful, competent, and loyal. Later, leaders officially announced the nominees and the Saints consented by voting for them.

Not coincidentally, on the afternoon before Independence Day in 1842, Joseph preached to eight thousand Saints on the Book of Daniel, emphasizing the theme “that in the last days the God of heaven would set up a kingdom.”[80] A week and a half later the Times and Seasons, which Joseph edited, continued the theme in the article “The Government of God.” Whether written by the prophet or simply approved by him, the thoughts were certainly his. Summarizing the distresses of world history, the article asked, “Where is there a man that can step forth and alter the destiny of nations and promote the happiness of the world?” The answer was the government of God: “It has been the design of Jehovah, from the commencement of the world, and is his purpose now, to regulate the affairs of the world in his own time; to stand as head of the universe, and take the reins of government into his own hand.” God’s government had existed with the patriarchs. “Their government was a theocracy,” the article stated; “they had God to make their laws, and men chosen by him to administer them . . . in both civil and ecclesiastical affairs; they were both one . . . ; so will it be when the purposes of God shall be accomplished.” The article then placed this government within the context of building Zion and the restoration of the church. Speaking of this theocracy, the article definitively proclaimed, “This is the only thing that can bring about the ‘restitution of all things, spoken of by all the holy prophets since the world was.’” God’s government was essential to fulfilling the destiny of Zion and, ultimately, the millennial reign of Christ.[81]

Joseph further developed the principles of theodemocracy and the kingdom of God throughout 1843. He declared: “[It is] our duty to concentrate all our influence to make popular that which is sound and good, and unpopular that which is unsound. ’Tis right politically for a man who has influence to use it.”[82] Theodemocracy allowed for the concentration of Joseph’s influence to advance Zion. In May Joseph addressed the members of the Nauvoo Legion, reminding them that those holding national power had ignored the Saints’ petition for protection and redress. “When they give me power to protect the innocent,” he declared, “I will never say I can do nothing for their good; I will exercise that power so help me God.”[83] Interestingly, Joseph asserted “when” not “if” he held national power.

Political Pressure and Persecution

The Saints’ political power was the central issue of the 1842 Illinois gubernatorial election. Their support of Democrat candidate Thomas Ford—the lesser of two evils in their eyes—was vital to his election. The Whigs, whom the Saints had supported the past two years, were incredulous. While Whiggery was more opposed to Latter-day Saint interests than the Democrats were, both parties became convinced that the political future of Illinois lay in the staggering Latter-day Saint immigration. Immigrants became voting citizens in only six months and, under the Nauvoo Charter, in only sixty days for city elections. This increased the power of the Saints’ voting bloc, yet their support was fickle. They no longer fit either party’s calculus for political success but rather loomed as an unpredictable and unmanageable obstacle.[84]

Joseph could not evade the political realities and consequences of his situation and choices. His adversaries were strong, and not all came from outside the church. For example, future electioneer missionary Benjamin L. Clapp accused Joseph and Hyrum Smith of attempting “to take away the rights of the citizens” during the 1843 Nauvoo City Council election. Religion’s claim on political choice denied deep-seated feelings of political freedom in the young republic, even among some Saints. Early church leader Oliver Cowdery became disaffected in part for this very reason. William Law, a member of the First Presidency, was just months away from a similar decision to part ways with the church.

During the August 1843 congressional elections, Law accused Joseph and Hyrum of political manipulation. Joseph had pledged his vote to Whig Cyrus Walker in a desperate exchange for legal help. Walker believed that if Joseph voted for him, so would all his followers, the pattern of the past three years. Walker and his Democrat rival Joseph Hoge campaigned strenuously in Nauvoo the week of the election, knowing that the Saints were the key to victory. Two days before the election, Hyrum addressed the Saints, declaring that the best interest of the people was to vote for Hoge. Law, himself a Whig, strongly objected, stating that he knew Joseph preferred Walker. Hyrum retook the stand and, with both hands holding up the Democrat ballot, shouted, “Thus sayeth the Lord” to a resounding cheer. The next morning on his way to the Sunday worship meeting to protest, Law confronted Joseph and Hyrum, whereupon Hyrum maintained that he had in fact received a revelation.

Joseph announced at the meeting, “I have not come to tell you to vote this way, that way, or the other.” He went on: “The Lord has not given me Revelation concerning politics. I have not asked the Lord for it. I am a third party [and] stand independent and alone.” Joseph said he intended to honor his commitment to vote for Walker but that the Whig had withdrawn “all claim to your [the Saints’] vote . . . if it will be detrimental to your interest as a people.” Then Joseph addressed Hyrum’s earlier declaration. “Brother Hyrum tells me . . . that he has had a testimony that it will be better for this people to vote for Hoge, and I never knew Hyrum [to] say he ever had a revelation and it failed. (Let God speak and all men hold their peace.)”[85] The reference to all men included Law. “I never authorized Brother Law to tell my private feelings,” Joseph thundered. “I utterly forbid these political demagogues from using my name henceforth and forever.”[86] Law was furious. The next day the Saints voted for Democrat Hoge, who won the election. Already disaffected with Joseph regarding Nauvoo’s economics and unsure of the plural marriage revelation, Law now became politically estranged.[87]

However, unlike Oliver Cowdrey and William Law, most Saints stayed politically loyal to their prophet. After talking with Joseph, the aforementioned Benjamin L. Clapp made a public apology, and the nomination meeting was “settled and mutual good feelings restored to all parties.” [88] In the city election, Joseph was unanimously reelected mayor of Nauvoo along with his slate of candidates. In the Saints’ view the right people were nominated to office because of their competence and loyalty and then were elected by church members in obedience to men whom they viewed as living prophets.

In September 1843 Joseph introduced the final priesthood ordinance. It also reflected elements of theodemocracy and aristarchy. He called it “the fullness of the priesthood,” but it became commonly known as the “second anointing.” This ordinance was a “promise of kingly powers and of endless lives. It was a confirmation of promises that worthy men could become kings and priests and that women could become queens and priestesses in the eternal worlds.”[89] Joseph administered the ordinance to chosen members, making them kings and priests “in and over” the church.[90] Such “anointed ones” were necessary to rule the kingdom of God. Those receiving this ordinance were kings and priests endowed with the fullness of priesthood power, “given . . . all that could be given to men on the earth” and thus had the power of legitimate heavenly governance. According to Joseph, government had apostatized, just as religion had. Thus, with proper authority in ordained kings and priests, or as they are mentioned “God’s Anointed Ones,” the kingdom of God could be restored.[91]

On 28 September 1843, Joseph began administering second anointings. In time he conferred the ordinance on twenty men and their spouses.[92] At the same meeting Joseph created a “special council.” It was no coincidence that this occurred in conjunction with the second anointings. An appendage of the Anointed Quorum, this was a protocouncil of the future Council of Fifty. It consisted of twelve church leaders who chose Joseph as president of the council by common consent. The prophet led the group in prayer, which included a petition “that his days might be prolonged until his mission on the earth is accomplished.”[93]

* * *

As October 1843 approached, Joseph Smith could look back with admiration on the thirteen years of the church’s beginnings. The fledgling church had blossomed into a community of more than twenty thousand on two continents. He had revealed doctrines to create a Zion society to prepare the world for the second coming of Jesus Christ. Yet this Zion had religious, economic, political, and social features that inflamed neighbors. New scripture, revelations, and doctrines, coupled with gathering converts under priesthood authority, seemed blasphemous and despotic to many Americans. Economic cooperation challenged free market capitalism. Continued rumors of polygamy denied traditional social values. Collective political power in the name of religion, unfettered to political party, was anathema in an age of powerful party politics. Consequently, the Saints were driven by force from New York, Ohio, and Missouri. Now Joseph’s attempt to create Zion in Nauvoo, Illinois, was threatened. Sensing the coming conflict, the prophet and his new “kings and priests” sought a solution to maintain peace and secure Zion. By 1844 Joseph would decide to protect Zion by running for president of the United States.

Notes

[1] JSH, E-1:1754 (15 October 1843). Spelling and punctuation have been modernized for all historical quotations herein.

[2] This and other quotations in this section are from Thomas, “Historical Sketch and Genealogy,” 8–13.

[3] See Cross, Burned-Over District; Hatch, Democratization of American Christianity; Abzug, Cosmos Crumbling; Kling, Field of Divine Wonders; and Quinn, “Joseph Smith’s Experience.”

[4] JSH, A-1:5.

[5] Book of Mormon title page.

[6] Doctrine and Covenants 21:1.

[7] See Church History in the Fulness of Times, 82; Van Wagoner, Sidney Rigdon; and Harper and Harper, “Van Wagoner’s Sidney Rigdon,” 261–74.

[8] See Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 122.

[9] See 3 Nephi 21:1, 23–24; 20:22; 22; Ether 13:3–6, 10; and Doctrine and Covenants 45:66–67.

[10] Doctrine and Covenants 6:6; 11:6; 12:6; 21:7. See Isaiah 33:20; 52:1 for an Old Testament prophecy of the return of Zion.

[11] Doctrine and Covenants 28:9.

[12] See Doctrine and Covenants 97:19–21, 25. On the similarities and differences of Latter-day Saint millenarian thought with its contemporaries, see Cohn, Pursuit of the Millennium, 13; Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 166; and Underwood, Millenarian World, 30–41.

[13] Moses 7:18–20. The Book of Moses came forth as a result of Joseph Smith’s inspired revision of the Bible. See Matthews, “Plainer Translation,” 25–26.

[14] See Doctrine and Covenants 38:27, 31–32.

[15] JSH, D-1:1572 (11 June 1843).

[16] The term stake is from Isaiah 54:2, describing the expansion of Zion: “Enlarge the place of thy tent, and let them stretch forth the curtains of thine habitations; spare not, lengthen thy cords, and strengthen thy stakes.” Zion was to expand like a great tent, extending more curtains secured by stakes. See Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 176, 220.

[17] See Doctrine and Covenants 42; 132.

[18] Snow, Journal and Letterbook, 21.

[19] Doctrine and Covenants 20:2–3.

[20] For priesthood development, see Prince, Power from on High; Quinn, Origins of Power, Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling; and Doctrine and Covenants 13. For arguments on the date of the restoration of the Melchizedek Priesthood, see the works in this footnote and Lawson, “Study of the Office.” For the official position of the church, see Church History in the Fulness of Times, 56; Porter, “Restoration of the Aaronic and Melchizedek Priesthoods,” 33; and Doctrine and Covenants 107:1–5.

[21] Edward Partridge was called by revelation as the first bishop in the church on 4 February 1831. See Doctrine and Covenants 41:9–10; see also 42:31, 34; 68:14. See also McKiernan and Launius, Book of John Whitmer, 66.

[22] See JSH, A-1:118 (6 June 1831).

[23] See Doctrine and Covenants 81:1–2.

[24] See Doctrine and Covenants 102.

[25] See Doctrine and Covenants 107:23–38.

[26] See Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 160, 175, 203, 263, 265, 267.

[27] See Doctrine and Covenants 110:11–16.

[28] Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 313–16; Church History in the Fulness of Times, 166–67.

[29] Doctrine and Covenants 132:37, 45. This revelation was recorded in 1843, but historical evidence shows that Joseph understood the doctrines and principles as early as 1831.

[30] The description specified public buildings such as “houses of worship, schools, etc.” Quoted in Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 220.

[31] Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 220.

[32] Section 42 of the Doctrine and Covenants was known as the “law of the Lord” and contained the divine laws required to build up Zion. On the law of consecration, see Church History in the Fulness of Times, 96–97, 99; Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 154–55; Parkin, “Joseph Smith and the United Firm,” 4–66; and Doctrine and Covenants 72:9–15. On the Kirtland Safety Society, see Church History in the Fulness of Times, 171–72; Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 331–32; Backman, Heavens Resound, 315–23; Shipps, “Mormons in Politics,” 48; and Backman, Kirtland Temple, 221.

[33] See Doctrine and Covenants 101:76–89.

[34] Minute Book 1, p. 42.

[35] See Doctrine and Covenants 101:55–58.

[36] See Doctrine and Covenants 105:2–13.

[37] See Church History in the Fulness of Times, 177.

[38] See Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 339; and Backman, Heavens Resound, 328.

[39] See Jackman, “Short Sketch,” 14:2–7; and Johnson, Mormon Redress Petitions, 246.

[40] Oliver Cowdery to the high council at Far West, Missouri, 12 April 1838, in Minute Book 2, p. 120.

[41] Rigdon, Oration, 12. See Church History in the Fulness of Times, 192.

[42] See Church History in the Fulness of Times, 194; and Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 356–67.

[43] Gentry, “Latter-Day Saints in Northern Missouri,” 201. See Church History in the Fulness of Times, 197.

[44] “Extract, from the Private Journal of Joseph Smith Jr.,” 3. See Church History in the Fulness of Times, 197.

[45] See Church History in the Fulness of Times, 195–96, 198.

[46] Lilburn W. Boggs to John B. Clark, 27 October 1838, 61.

[47] See Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 365; and Church History in the Fulness of Times, 204.

[48] See Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 375–76; and Church History in the Fulness of Times, 202–8.

[49] See Tanner, John Tanner and His Family, 92–94.

[50] Joseph Smith, letter to Presendia Huntington Buell, 15 March 1839, in JSH, C-1:898[a].

[51] See Esplin, “Significance of Nauvoo,” 19–38. Lyman Wight claimed after Joseph’s death that the prophet had said he did not expect to live to be forty; see Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 2:432.

[52] JSH, C-1:1016; and Joseph Smith to Hyrum Smith and the Nauvoo High Council, 5 December 1839, in Smith, Letterbook 2, 85–88. What exactly Joseph wanted the president to do is unclear. Perhaps he hoped that Van Buren would mention the Saints in his written address to Congress. See JSP, D7:xxv–xxvi.

[53] Smith, “Extract, from the Private Journal of Joseph Smith Jr.,” 9.

[54] Joseph Smith to Robert D. Foster, 11 March 1840, in JSP, D7:227.

[55] Van Buren was the architect of the Jacksonian Democratic Party and was elected president in 1836, following two terms of orchestrating the election of Andrew Jackson. Van Buren’s rejection of the Saints was particularly galling since many of them had campaigned for him. See Quinn, Mormon Hierarchy: Origins, 182. The Saints voted for all of Harrison’s electors except Abraham Lincoln, whose name they replaced to include one Democrat.

[56] Quinn, Mormon Hierarchy: Origins, 106.

[57] Kimball, “Nauvoo Charter,” 40–47. Joseph was commissioned a lieutenant general, the only such rank for the period between George Washington and Ulysses S. Grant.

[58] JSH, C-1:1131 (16 December 1840); and Kimball, “Nauvoo Charter,” 40–47.

[59] See Quinn, Mormon Hierarchy: Origins, 107. Shipps, in “Mormons in Politics,” 56–57, observes: “Perhaps [in Liberty Jail] he realized that building Zion inside the boundaries of the United States required something more. . . . When the Mormons began at the beginning once again, Smith turned to politics in an effort to surround Zion with constitutional sanction.” See also Church History in the Fulness of Times, 243.

[60] See Church History in the Fulness of Times, 265. Most of the new arrivals were from the British Isles. The term Anti-Mormon as used here refers specifically to the political party. As Nauvoo grew, so did ties between the church and government. When the apostles returned in 1841, six of the seven were elected to the now-expanded city council. In 1842 Joseph received all but three votes for the new office of vice mayor, and his brother William was elected to the state legislature. See Quinn, Mormon Hierarchy: Origins, 108–9.

[61] See JSH, C-1:1147 (15 January 1841); and Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 413; and Smith, “Proclamation, 15 January 1841,” Times and Seasons, 15 January 1841, 276.

[62] Doctrine and Covenants 124:2.

[63] Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 405; and Flanders, Nauvoo, 68.

[64] See JSH, D-1:1424 (4 December 1842); and Leonard, Nauvoo, 204 and endnote 10. It was not until the Saints were settled in Utah that bishops became the presiding officers spiritually and temporally in wards.

[65] See Jenson, Historical Record, 233; Compton, In Sacred Loneliness; and Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 437–46, 490–99.

[66] Joseph Smith, “The Globe,” Times and Seasons, 15 April 1844, 510. For a discussion of theodemocracy, see Hartshorn, Wright, and Ostler, Book of Answers, 7.

[67] Joseph most likely began receiving revelations regarding the political kingdom of God on 7 April 1842. See Council of Fifty, Minutes, 10 April 1880.

[68] JSH, D-1:1389 (29 August 1842).

[69] Daniel 2:44; Revelation 20:6.

[70] Council of Fifty, Minutes, 10 April 1880.

[71] Quinn, “Council of Fifty,” 1.

[72] Smith, “Motto, circa 16 or 17 March 1838,” in JSJ, 16 or 17 March 1838. See “History and genealogy of Chapman Duncan,” 447 (the only reference I could find of the motto’s use during the campaign).

[73] Noah Webster, ed., An American Dictionary of the English Language (New York: S. Converse, 1828), s.v. “aristarchy.”

[74] Doctrine and Covenants 98:9–10.

[75] Cleveland, “Female Relief Society of Nauvoo,” 30 March 1842, p. 21.

[76] Cleveland, “Female Relief Society of Nauvoo,” 17 March 1842, 7.

[77] Revelation 1:6.

[78] See Joseph Smith’s sermon known as the “King Follet discourse,” delivered on 7 April 1844 and recorded in Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 2:384, especially the statement “And you have got to learn how to make yourselves God, king and priest, by going from a small Capacity to a great capacity to the resurrection of the dead to dwelling in everlasting burnings” (original spelling and punctuation preserved).

[79] JSH, C-1:1338 (26 May 1842).

[80] Smith, “Letter to the Citizens of Hancock County,” The Wasp, 2 July 1842, 2.

[81] “The Government of God,” Times and Seasons, 15 July 1842, 856–57; emphasis added.

[82] Smith, “Discourse, 21 February 1843,” as reported by Willard Richards in JSJ under that date.

[83] JSH, D1:1547 (6 May 1843).

[84] See Hampshire, “Nauvoo Politics,” 3:1000; and Nauvoo Charter, section 7.

[85] JSJ, 6 August 1843.

[86] JSH, E-1 (6 August 1843).

[87] For more on the exchanges of these two days, see Cook, “William Law, Nauvoo Dissenter,” 47–72; Wicks and Foister, Junius and Joseph, 45–46; and W. Wyl, “Interview with William Law in Shullsburg, Wisconsin, 30 Mar 1887,” Salt Lake Daily Tribune, 31 July 1887, 6.

[88] JSJ, 4 February 1843.

[89] Leonard, Nauvoo, 260–61; emphasis added. See also JSH, E-1 (6 August 1843).

[90] Ehat, “Joseph Smith’s Introduction of Temple Ordinances,” 74–75.

[91] Heber C. Kimball, in journal kept by William Clayton, 26 December 1845, as quoted in Ehat, “Heaven Began on Earth,” 3–4.

[92] See Ehat, “Heaven Began on Earth,” 3 and note 16. Four were future electioneer missionaries: Reynolds Cahoon, Alpheus Cutler, Levi Richards, and William W. Phelps.

[93] JSH, E1:1738 (28 September 1843). The members of the protocouncil were Joseph Smith, Hyrum Smith, John Smith, Newel K. Whitney, George Miller, Willard Richards, John Taylor, Amasa Lyman, John M. Bernhisel, Lucien Woodworth, William Law, and William Marks.