Epilogue

A Lost but Lasting Legacy

Derek R. Sainsbury, “Epilogue,” in Storming the Nation: The Unknown Contributions of Joseph Smith’s Political Missionaries (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 299‒310.

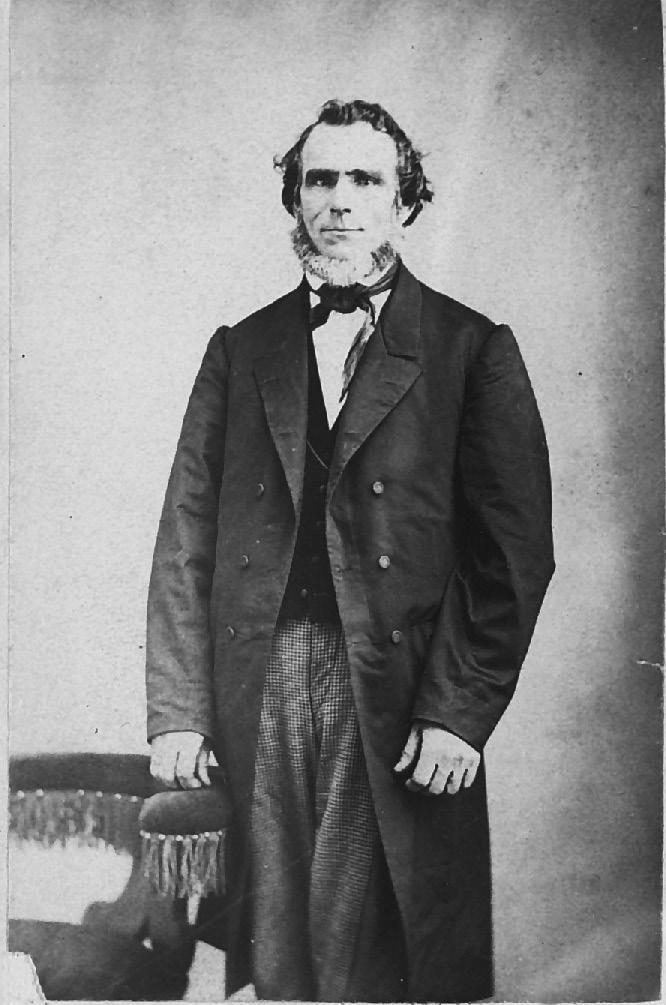

Abraham O. Smoot

The church’s appearance at the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893 signaled the beginning of American acceptance of the Latter-day Saints and the Americanization of the church. However, the rejection of B. H. Roberts as a delegate to the World Parliament of Religions proved that the nascent reconciliation had its boundaries and portended a rocky relationship still ahead. Roberts was a general authority, an intellectual and historian, and a polygamist. For the Protestant-led parliament, it was the last trait that was abhorrent. Five years later when Roberts won a seat in Congress, the lingering prejudice against the church was clear. Despite Roberts’s pardon by US President Cleveland, Republicans, urged on by Protestant ministers, blocked Roberts from being seated. The incident presaged the contested seating eight years later of apostle, electioneer-son, and Republican senator-elect Reed Smoot. Abraham O. Smoot’s fatherly relationship to his son Reed encapsulates the rise of the electioneer missionaries, their leading role in the Great Basin kingdom, that kingdom’s eventual capitulation to American cultural forces, and the consequent loss of memory about the electioneers’ influence in Latter-day Saint history. It also exemplifies the enduring legacy of the electioneer cadre through their descendants.

Born in 1815 in Kentucky, Abraham O. Smoot was the son of a poor Tennessee farmer. He received only a very rudimentary education and was just thirteen when his father died. His mother joined the church in 1833, and he followed her example two years later. The missionaries ordained Smoot a deacon and left him to preside over a small branch. He soon became an elder and later a seventy. He served four short missions in Kentucky and Tennessee and one in South Carolina. In 1838, while still in prison for his role in the Mormon War, Smoot married. He then settled in Iowa across the Mississippi River from Nauvoo.

Despite his meager schooling, indigent upbringing, and young age of twenty-nine, Smoot was “called and sent by the conference of the church . . . and Quorum of Twelve” to preside over the electioneer missionaries in Tennessee.[1] Campaigning in the South with a platform advocating the end of slavery proved challenging. Tennesseans shot at, threw brickbats at, and vandalized the property of Smoot and his companions. They sued him under Tennessee’s statutes to prevent him from printing copies of Joseph Smith’s Views. Others directed death threats at him and his electioneers. Yet Smoot and his men persevered. He preached and politicked throughout Tennessee, holding conferences with fellow Saints and electioneers. He debated with ministers of religion and political foes alike. On 8 July 1844 he received the first rumors of Joseph’s murder, which were confirmed four days later. As “awful forebodings seared [his] mind,” Smoot slowly returned to Nauvoo.[2] Finding Nauvoo in a “melancholy gloom” mirroring his own feelings, Smoot recorded, “These are days long to be remembered by me.”[3]

The apostles remembered Smoot’s courageous campaigning and loyalty. Just months later, they ordained him a high priest and selected him and forty-three other electioneers as part of a cohort of eighty-five high priests. Their assignment was to preside over the church in one of eighty-five key congressional districts. Although most did not undertake this assignment, Smoot did. He traveled to Alabama with his family, arriving in December 1844 on what would have been Joseph’s thirty-ninth birthday. Smoot held a conference and began his work. He traversed Alabama, just as he had Tennessee, confidently preaching and setting in order all the branches through April 1845, when the Twelve recalled him. In Nauvoo, Smoot was endowed, introduced to the principle of plural marriage, and sealed to two additional wives.

During the Saints’ exodus, Smoot led companies in the years 1847, 1852, and 1856. Brigham placed him on the Municipal High Council in Salt Lake in 1847. He was the first justice of the peace in the Great Basin and, for a time, the only one west of the Missouri River. He was called as bishop of the Salt Lake City Fifteenth Ward in 1849. The following year he and fellow electioneer Jedediah M. Grant used their resources and connections to form a business importing eastern merchandise. In 1852 Smoot served another mission, this time in England. His companions were fellow electioneers Willard Snow and Samuel W. Richards. Church leaders in England selected Smoot to lead the first Perpetual Emigrating Fund company to Salt Lake City. The smoothness of the operation set the tone for the decades-long program and “did credit to Bishop Smoot, as a wise and skillful manager.”[4] Upon Smoot’s return, Brigham reassigned him as bishop of South Cottonwood.

After the death of Jedediah M. Grant, Smoot’s business partner and mayor of Salt Lake City, Brigham nominated Smoot to fill his place. Unanimously elected the city’s second mayor, he served for a decade. Like Lorenzo Snow, he personified the electioneers’ social mobility. In 1860 he was a mayor and bishop with five wives, and he had amassed nine thousand dollars of real estate and ten thousand dollars in personal wealth—a far cry from his humble beginnings as an uneducated Tennessee farmer. In 1867 he was admitted to the Council of Fifty. The next year Brigham sent him to Utah County ahead of the railroad’s arrival to be the county’s theodemocratic leader charged with protecting the Saints from inevitable gentile influences. Smoot took charge of the Utah (Valley) Stake and was elected mayor of Provo, an office he held until 1881. In 1872, when the Liberal Party began challenging the territory’s firm theodemocratic governance, Smoot exerted an even stronger countervailing influence: chairing the Utah County People’s Party nominating committee and accepting election to the Territorial Council, all the while continuing as stake president over the county and mayor of Provo.

Smoot also excelled in managing the business operations of the county. At his death in 1895, he owned half of the stock in the Provo Cooperative Institution that he began in 1868. He was the president of two banks and the Provo Woolen Mills, the largest of its kind west of the Mississippi. He also served as president of Brigham Young Academy, the precursor to Brigham Young University.

In Abraham O. Smoot are concentrated all the best characteristics of the aristarchy of the theodemocratic Zion kingdom. His electioneer service in Joseph’s campaign helped catapult his meteoric rise in leadership responsibility and influence. Before the campaign, he was like many others who had joined the church and spread the restored gospel as a missionary—sharing in its joys and persecutions. But his life course took a new direction when he first stepped forward to respond to the call for electioneers. The trying experience of campaigning and preaching in the face of persecution and then mightily persevering in the mission field under the pall of Joseph’s assassination was the crucible that created in the young man an unswerving loyalty to the cause of theodemocratic Zion. The cycle of rising to formidable challenges and succeeding continued throughout his life, leading to increasing positions of trust and responsibility.

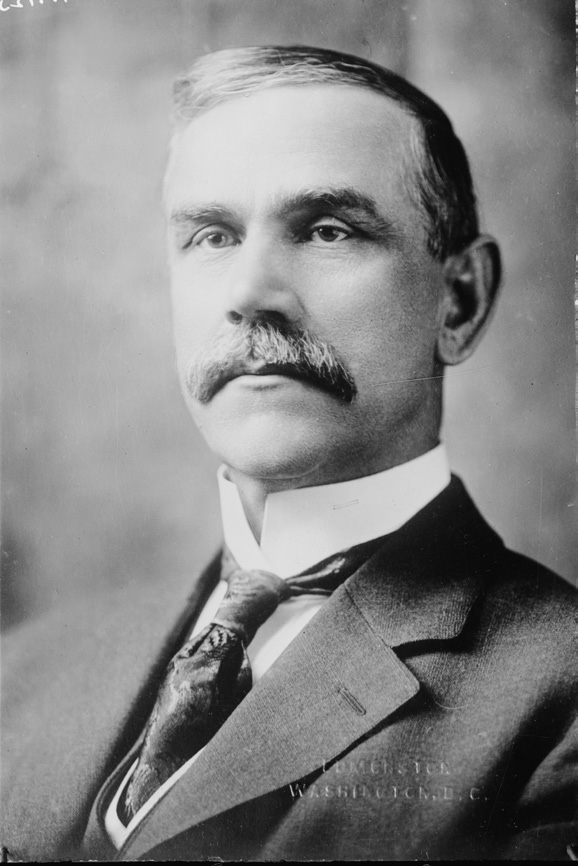

Reed Smoot

Abraham O. Smoot’s third wife, Anne Mauritzen, gave birth to son Reed in January 1862. Reed began school at a young age and was numbered with the first graduating class of Brigham Young Academy (in 1879), where his father was president. Reed studied business and during academic breaks worked at the Provo Woolen Mills, founded and directed by his father. Upon graduation, Reed took a job in the Provo Cooperative, which, again, his father oversaw. Eighteen months later he became manager of his father’s woolen mills.

The career arcs of electioneer Abraham O. Smoot (above) and his son Reed (below) illustrate the rise, success, demise, and ultimate continuation of the electioneer cadre. Photo of Abraham Smoot by Edward Martin courtesy of Church History Library. Photo of Reed Smoot courtesy of National Archives, George Gantham Bain Collection.

The career arcs of electioneer Abraham O. Smoot (above) and his son Reed (below) illustrate the rise, success, demise, and ultimate continuation of the electioneer cadre. Photo of Abraham Smoot by Edward Martin courtesy of Church History Library. Photo of Reed Smoot courtesy of National Archives, George Gantham Bain Collection.

In 1884 Reed married the daughter of electioneer Horace S. Eldredge, one of the seven Presidents of the Seventy. By that time, marriage between electioneer children was very common since these families, by nature of their friendships and status, moved in the same social circles. In 1890 Reed, like his father, served a mission to England. Although some people had viewed Reed as more concerned about business than religion, his mission apparently helped equalize the two interests. In clerking for European Mission president Brigham Young Jr., Reed gained valuable experience that would serve him well in later assignments in both the church and government. Fittingly, the electioneer son was assisting the apostle-son of Brigham Young—the next generation of leadership mirroring the previous one.

Returning to Utah in 1891, Reed resumed his duties as manager of the Provo Woolen Mills and branched out, founding and directing a bank and an investment company. He became vice president of two mining companies, director of the Clark-Eldredge Company and of ZCMI, and a director of the Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad. After his father’s death in 1895, Reed was ordained a high priest and called as a counselor in the stake presidency that succeeded his father. In 1900 church president Lorenzo Snow called thirty-eight-year-old Reed to be an apostle, replacing former electioneer Franklin D. Richards.

Reed came to adulthood during the Raid and chose monogamy. His business acumen and focus, coupled with church leaders’ outreach to the Grand Old Party in hopes of attaining Utah statehood, made Reed a natural Republican. In the same year he became an apostle, he considered running for the Republican nomination for the US Senate. Because of the church’s Political Manifesto, he first needed permission from the First Presidency. After deliberation, President Lorenzo Snow, whose earlier accomplishments in both ecclesiastical and political arenas had made him the epitome of theodemocratic success, decided against Reed’s request. However, when Snow died in 1901, Reed approached new president Joseph F. Smith, who gave his approval. Reed went on to win the Republican nomination and the Senate election in 1903. Thus the nephew of assassinated presidential candidate Joseph Smith Jr. gave approval for an electioneer son and apostle to seek high government office—a different shade of theodemocracy for a new generation.

Reed’s victory turned into a national debate over whether the church had definitively abandoned plural marriage, was loyal to the country, and had desisted from combining church and state. After Reed was seated, hearings began to unseat him. Over four years, the hearings filled thirty-five hundred pages, examined more than a hundred witnesses (including Joseph F. Smith), and solicited enough letters to senators to make it the largest such collection in the National Archives to this day.[5] Church leaders and practices were lampooned in political cartoons nationwide. The uproar over stories of continued polygamy caused President Smith in 1904 to issue the Second Manifesto. It reiterated the church’s prohibition of plural marriage and threatened excommunication for any future incidents. To counter charges of theocratic politics in Utah, Smith and the First Presidency issued a statement in 1903 proclaiming political neutrality and encouraging Latter-day Saints to vote their conscience. After a deal between the church and Republican leaders, the Senate finally voted in 1907 and Reed was able to retain his Senate seat. He continued to serve as a senator until defeated in the 1932 election, and he remained an apostle until his death in 1941.

Restoring a Lost but Lasting Legacy

We have seen how the career arcs of Abraham O. Smoot and his son Reed capture the electioneers’ influence on the rise and fall of Latter-day Saint theodemocracy and the church’s unsteady transition to Americanization. The senior Smoot exemplifies the electioneers’ rise to power following the failed 1844 presidential campaign. In the wake of Joseph’s assassination, the more than six hundred political missionaries became a pool of proven leaders that Brigham relied on to move the faith safely beyond the American frontier and the persecution that had so often followed them. Under theodemocracy in the Great Basin, they became an integral part of the aristarchy that Brigham needed to build and guide Joseph’s Zion in hundreds of settlements. Often holding key business and political positions in their communities, they emphasized unity in politics and cooperation in economic affairs. As local, regional, or general church authorities, they obediently practiced plural marriage as a commandment and as an example to other Saints. With multiple wives came the advantage of additional farmland and town plots. This increased wealth could be successfully leveraged using connections to other electioneer leaders throughout Utah or multiplied as a result of appointments to leadership positions that promoted industry and cooperative commercial enterprises. As discussed, a vast majority of the electioneer veterans experienced upward mobility religiously, politically, socially, and economically.

As the frontier encircled Utah, American values of Protestantism, partisan politics, Victorian morality, and economic capitalism—backed, as became clear in many instances, by the full force of the federal government—choked the church’s unique, un-American characteristics. This drama played out while the electioneers’ influence was waning because of age, death, and persecution. With capitulation followed by statehood, home rule returned to Utah, but under a new set of rules. It would take twenty-five tenuous years before the church became acceptably harmonious with Americanism. During this transition emerged the next generation of Latter-day Saint religious, political, social, and economic leaders. Like Reed Smoot, these new leaders were often the sons of electioneers, but with generational differences reflective of changing times. In religious practice, they were monogamous and focused on keeping the Word of Wisdom and the law of tithing and doing temple work. As Americanized citizens, they politicked as Republicans and Democrats and championed individual capitalism and self-sufficiency.

Interestingly, while church priorities changed over a generation, the families of its high-ranking leaders did not change as quickly or as much. The Grant, Tanner, Smoot, Benson, Rich, Lee, Snow, and Smoot families are only a few of many families that can trace their lineage from electioneers through subsequent and current church leaders. In fact, electioneer surnames (often hidden in matriarchal lines) remains until today a virtual who’s who of Utah’s religious, political, social, and economic leaders a century after Americanization. Although federal suppression and the passage of time disrupted and weakened aristarchal authority in Utah, a new echelon rose to take its place. Sons replaced fathers in a world contoured to match, in innovative ways, the one that had just passed. The electioneers left a legacy through family connection that would prove advantageous for their descendants who would ascend the rungs of church leadership.

One last example may suffice. Electioneer John Tanner was a wealthy businessman who spent his fortune assisting Joseph in building Zion in Kirtland and Nauvoo. His sons Nathan and Martin joined him in electioneering in New York. While Martin never came west, Nathan, eight other sons, and John’s only living daughter joined him in the Great Basin. Nathan alone “was the ancestor of Hugh B. Brown, apostle and counselor to President David O. McKay; of Fern Tanner Lee, wife of President Harold B. Lee; of President Nathan Eldon Tanner, counselor in four First Presidencies; and of Victor L. Brown, Presiding Bishop of the Church.”[6] John’s daughter Louisa Maria married electioneer apostle Amasa Lyman, and their son Francis M. Lyman and grandson Richard R. Lyman became apostles. Former member of the Presidency of the Seventy Marion D. Hanks is also a descendant. John’s son Myron served for twenty years on the Provo City Council and twenty-three years as bishop of the Provo Third Ward. He donated his thriving businesses to Abraham O. Smoot to support the Provo Cooperative. Myron’s son Joseph was the first Latter-day Saint graduate of Harvard University, the second commissioner of church education, and the president of Utah State College. Joseph’s son Obert became a successful businessman, professor of philosophy, and noted philanthropist. John Tanner’s son Joseph Smith was mayor of Payson, Utah, and its bishop for twenty years. And these are just some of John Tanner’s descendants (the examples from other electioneers are too numerous for the scope of this book). It is noteworthy that while capitulation to American culture ensured the church’s survival, Americanization left power mostly in the hands of those who had always held it—namely, the faithful electioneers and many of their equally faithful descendants.

* * *

Lamentably, the passage of time, assisted by biased intergenerational memory, relegated Joseph Smith’s 1844 presidential campaign to a mere historical footnote. As much as Frederick Jackson Turner’s “frontier thesis” is the narrative beginning of the history of the American West, B. H. Roberts’s writings became the interpretive foundation from which Latter-day Saints have written their history for more than a century.[7] When Roberts wrote, edited, and provided commentary in his works, the church was in the middle of its difficult transition to national acceptance and often a source of ridicule. Church leaders were attempting to minimize the controversial aspects of the faith’s past. Roberts himself was not far removed from Congress’s refusal to seat him over plural marriage and issues of church and state. In this political context, it is not surprising that while the daily documentary evidence shows the unfolding centrality of Joseph’s presidential campaign in 1844 Nauvoo, Roberts’s editorializing minimized its importance. He downplayed statements of Joseph’s determination to win and opined that the campaign was not serious, attributing it to other motives.

In the years that followed, historians in and out of the church who commented on Joseph’s campaign tended to follow Roberts’s dismissive interpretation. The exceptions did not produce the historical narrative that reached most Saints. However, one cannot read the primary-source documents about Joseph and his colleagues from November 1843 until his death in June of 1844 without seeing that the campaign and its wider political context were a major focus (if not an exclusive one at that time) of the prophet and other church leaders. The Council of Fifty minutes have now concretized the fact. Joseph’s actions and his enemies’ reactions, especially his assassination, do not completely fit together without factoring in the centrality of the election campaign at that time. That there would not be another Latter-day Saint missionary force as large as the 1844 electioneer missionaries (and never one as proportionally large vis-à-vis total church membership) until 1902, the year Roberts published History of the Church, further attests the campaign’s importance. Thus as Zion slipped below the horizon, so did memory of Joseph’s campaign with its nation-storming electioneers and their kingdom-building contributions.

To be sure, as demonstrated in this book, Joseph Smith Jr. ran a serious campaign for president of the United States—one that directly led to his death. More importantly, this work has uncovered the stories of many electioneer missionaries as well as their contributions not only to the campaign but also to the church’s post-martyrdom trajectory—particularly theodemocratic Zion. Ironically, hundreds of thousands or more of Latter-day Saints and others alive today are direct descendants of the forgotten electioneers. The hundreds of men and one woman who campaigned for Joseph have been underappreciated, overlooked, or forgotten, as have their outsized contributions to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

The story of Joseph Smith’s cadre of electioneers is the church’s early story. Enduring the tempests of persecution in Ohio, Missouri, and Illinois, they longed for, and became perfect foot soldiers of, a theodemocracy to protect their Zion dream. This courageous volunteer cadre knowingly and defiantly strode into a political hurricane. Resolute faith in Joseph and Zion drove them. When assassins murdered their prophet-candidate, the electioneers picked up the pieces of their shattered campaign and, with their fellow Saints, fled the nation that had rejected them. In the Great Basin, finally, they were able to build their dream: theodemocratic Zion. As religious, political, social, and economic leaders, they worked with and as church leaders to shelter Zion from further storms for decades. In the end, as their influence dwindled with age and death, they watched helplessly as the whirlwinds of the federal enforcement of American culture destroyed the heaven-directed endeavor of their lifetimes. Even then, those still living did not give up the dream of Zion. They still believed with “enthusiastic fervor” that one day “Zion in her beauty” would rise and remain—“as surely as the sun now shines in heaven.” They have much to teach their descendants, all Latter-day Saints, and Americans generally—not the least of which is “Unity is power.”[8]

Notes

[1] Smoot, Day Book, 1.

[2] Smoot, Day Book, 8 July 1844.

[3] Smoot, Day Book, 28 July 1844.

[4] Larson, Prelude to the Kingdom, 159–60.

[5] See Flake, Politics of American Religious Identity, 9–10.

[6] Leonard J. Arrington, “The John Tanner Family,” Ensign, March 1979.

[7] Particularly, B. H. Roberts published The Rise and Fall of Nauvoo (1900), edited the seven-volume History of the Church (1902), and authored the six-volume Comprehensive History of the Church (1930).

[8] The quotes are from electioneer John M. Bernhisel (see chapter 11, footnote 3); Partridge, “Let Zion in Her Beauty Rise,” Sacred Hymns (1835), 86; and Joseph’s Views, 4.