Deseret: Emerging Aristarchy of the Kingdom, 1848–1851

Derek R. Sainsbury, “Deseret: Emerging Aristarchy of the Kingdom, 1848-1851,” in Storming the Nation: The Unknown Contributions of Joseph Smith’s Political Missionaries (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 201‒26.

High on the mountain top, / A banner is unfurled. / Ye nations, now look up; / It waves to all the world. / . . . Then hail to Deseret! / A refuge for the good, / And safety for the great. / . . . God with plagues will shake the world / Till all its thrones shall down be hurled.

—Joel H. Johnson, “Deseret.”[1]

Raising a Standard to the Nations

Two days after arriving in the valley of the Great Salt Lake, Brigham Young and others climbed a domed precipice north of their encampment. It was the same peak that Brigham declared the deceased Joseph Smith had shown him in vision. The gathered men, which included electioneers Lorenzo D. Young and Erastus Snow, viewed the valley below. Brigham explained they were fulfilling Isaiah’s prophecy that in the last days God would “lift up an ensign [banner or standard] to the nations” (Isaiah 5:26). Here Zion would be built and righteous people of the world would gather to prepare for the return of Jesus Christ. In their poverty, the only banner the weary emigrants could wave was a dirty yellow handkerchief tied to the end of a walking stick. Yet they had lifted God’s standard to the nations—symbolizing the literal Zion of the scriptures.

Two days later Brigham declared, “We shall erect the Standard of Freedom.”[2] An actual flag would yet fly. In fact, church leaders had planned such an event since the first day of the Council of Fifty in March 1844. The minutes record, “All seemed agreed to look to some place where we can go and establish a theocracy.” The council determined to create the earthly kingdom of God “according to the mind of God.” It would be complete with a “standard to the people, an ensign to the nations,” and the council was confident that “all nations would flow unto it.”[3] In a later meeting Hyrum Smith “believed if we will set up the standard and raise the ensign the honest in heart of all nations will immediately begin to flock to the standard of our God.”[4] The council saw this standard as being a symbolic and literal flag.

A cryptic reference in the Council of Fifty’s minutes notes under the date of 22 June 1844—the night Joseph fled across the Mississippi River to escape apprehension—that he “gave orders that a standard be prepared for the nations.”[5] He expected to take the sixteen-foot banner with him. The Saints began crafting the flag the day before Joseph’s death, and his murder did not extinguish but only delayed the quest to plant the standard. In January 1846 Brigham declared to the Fifty that “the saying of the prophets would never be verified unless . . . the proud banner of liberty [is made to] wave over the valleys that are within the mountains.” He then said, “I know where the spot is, and I know how to make the flag.”[6]

Some of the electioneers were directly involved in creating and displaying the banner. On 27 February 1847, Jedediah M. Grant, Ezra T. Benson, Erastus Snow, and others of the Council of Fifty huddled with Brigham at Winter Quarters. The council determined that “the time had come to prepare the flag that Joseph Smith had first talked about.” They wanted the “best stuff in the eastern markets,” and they increased the size from Joseph’s sixteen-foot flag to a ninety-by-thirty-foot “mammoth flag” that could be seen from afar. A hundred-foot flagpole would ensure the standard’s visibility. The council chose Grant to visit “various seaports” to find the appropriate material. Grant’s letter of authorization asked eastern Saints to contribute “means to accomplish [this] great work,” which would be “an ornament to the cause” of Zion. While Grant was gone, the vanguard company embarked on its journey west. Grant succeeded in his peculiar assignment, returned to Winter Quarters, and departed west—but not in time to raise a proper ensign with Brigham’s company on Ensign Peak. In fact, the flag created from Grant’s material would not debut until 24 July 1849, the second anniversary of the pioneers’ arrival in the Salt Lake Valley.[7]

The Saints planned a big day of celebration that year, which became a tradition—Pioneer Day—repeated every July up to the present day. This first festivity, at the base of Ensign Peak, included “parades, banners, decorations, music, and dinner—each done on a scale meant to convey saga.”[8] Brigham entrusted cadre comrades Lorenzo Snow, Jedediah M. Grant, and Franklin D. Richards to plan the theodemocratic celebration. The evening before, two hundred men erected a 104-foot flagpole. In the morning, an honor guard raised the 65-foot “mammoth flag.” Gun salutes, band music, and the ringing of the Nauvoo bell greeted the banner. Gentiles passing through the valley described the flag—the flag of Deseret, as locals called it—as blue and white, fashioned after the United States flag. In contrast to the US flag, the field had twelve stars circling a large star and twelve alternating white and blue stripes. The blue symbolized heaven; the white, purity; the twelve stars and large star, the apostles and Christ; and the stripes, the twelve tribes of Israel. A mix of theocratic and American symbols, this flag confused the gentiles at the celebration.

Furthermore, a smaller copy of the flag led the parade that day. This “kingdom flag” was carried on horseback by the parade’s marshal, electioneer veteran Horace S. Eldredge. Next came a brass band and the city’s twelve bishops, seven of them electioneers.[9] Twenty-four young men and twenty-four young women followed. The men were dressed in “white pants, black coats, white scarfs on the right shoulder, and coronets on their heads, each carrying in his right hand a copy of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States, and each wearing a sheathed sword by his side.” The women were “dressed in white, with blue scarfs on the right shoulder and wreaths of white roses on their heads, each carrying a Bible and a Book of Mormon.”[10] The number twenty-four coupled with the crowns signified the “kings [and queens] and priests [and priestesses]” surrounding God’s throne, as portrayed in the book of Revelation (1:6; 5:10). The message of the crowned men holding America’s founding documents and the crowned women holding the scriptures was clear to all. This was the marriage of democracy and religion—theodemocracy.

Next came the apostles (including electioneers Lorenzo Snow, Franklin D. Richards, Charles C. Rich, and Erastus Snow), followed by the stake presidency of Daniel Spencer, David Fullmer, and Willard Snow (all electioneers). Last in line were twenty-four “Silver Greys” (men over sixty years old). One held the US “Stars and Stripes” with an inscription that read “LIBERTY OR DEATH.” The parade marched to Brigham’s house, where Brigham and Heber C. Kimball joined in. As the procession returned to the Bowery, the young people sang a new song called “The Mountain Standard,” whose words praised “Freedom’s banner,” “Zion’s standard wide unfurled,” waving “for all the world.”[11]

Under the shadow of the Deseret flag, the amassed Saints clamored, “Hosanna to God and the Lamb!”—a sacred shout based on Jesus Christ’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem. Next they cheered, “Hail to the governor of Deseret!” as Brigham passed by. After an invocation from Erastus Snow, Brigham stood and led the crowd in three cheers of “May they live forever!” Phineas Richards, a recently selected member of the Council of Fifty and father of electioneers Franklin D. and Samuel W. Richards, then gave a “loyal and patriotic address” on behalf of the “aged sires.”[12]

Phineas focused on the Saints’ expulsion from Nauvoo and their status as true inheritors of American republican ideals. Joseph had been “inspired by the Spirit of the Almighty . . . and, with the pencil of heaven” (alluding to Views), declared the nation’s “impending desolation and ruin.” The prophet, “prompted by an unction from the upper world, essayed to put forth his hand to preserve the tottering fabric [of the Constitution] from destruction.” Instead, his enemies have assassinated him and “have driven the Saints from their midst, . . . and now the vengeance of insulted heaven awaits them!” Phineas offered the solution—the establishment of Latter-day Saint theodemocracy: “It devolves upon us, as a people instructed by the revelations of God, with hearts glowing with love for our fallen country, to revive, support, and carry into effect the original, uncorrupted principles of the Revolution and the constitutional government of our patriotic forefathers.”

“To you, President Young, as the successor of President Smith, do we now look, as to a second Washington, so far as political freedom is concerned,” continued Phineas. It was the duty of Brigham—president of the Church; standing chairman and prophet, priest, and king of the Council of Fifty; and governor of the State of Deseret—to “replant the standard of liberty, to unfurl the banner of protection.” Brigham’s “godlike integrity . . . [in] support of our murdered prophet” gave the Saints the “utmost confidence” to support him in finishing Joseph’s measures. “Let us prove to the United States that when they drove the Saints from them . . . they . . . drove [out] . . . the firmest supporters of American Independence.” With his cadence now in crescendo, Phineas proclaimed that, starting with Deseret, “let a standard of liberty be erected that shall reach to heaven and be a rallying point for all the nations of the earth.” As revolutions and upheaval destroy kingdoms and nations, “here let the ensign of peace, like a heavenly beacon, invite to a haven of rest, an oasis of civil, political, and religious liberty. From here let the paeans [ancient songs of victory] of theodemocracy or republicanism reverberate from valley to valley, from mountain to mountain, from territory to territory, from state to state, from nation to nation, from empire to empire, from continent to continent.” The assembly assented, arising to shout three times, “Hosanna! Hosanna! Hosanna to God and the Lamb, for ever and ever, amen and amen!”[13]

For two years church leaders continued to raise the flag of their theodemocratic state—Deseret. Electioneer Joel H. Johnson penned a poem about the flag raising titled “Deseret.” Later set to music, it became a popular Latter-day Saint hymn, one still sung today—“High on the Mountain Top.”

High on the mountain top a banner is unfurled.

Ye nations, now look up; it waves to all the world.

In Deseret’s sweet, peaceful land,

On Zion’s mount behold it stand!

For God remembers still his promise made of old

That he on Zion’s hill Truth’s standard would unfold!

Her light should there attract the gaze

Of all the world in latter days.[14]

A replica of the flag of Deseret, first used in 1849, flies today at Ensign Peak alongside the US and state of Utah flags. Photo courtesy of the author.

A replica of the flag of Deseret, first used in 1849, flies today at Ensign Peak alongside the US and state of Utah flags. Photo courtesy of the author.

Indeed, the flag of Deseret did attract the gaze of Saints and gentiles that day in 1849. Latter-day Saints viewed the banner as biblical prophecy fulfilled—a sign that they were God’s people and about his work. In their State of Deseret, they not only satisfied prophecy but also redeemed the Declaration of Independence and Constitution. They looked forward to people gathering in the valley from all over the world to build up the earthly kingdom. But what that kingdom’s relationship would be with the rest of the United States was still tenuous. Several hundred forty-niners on their way to California were guests that day. The mix of patriotic, religious, and even theocratic symbols and rhetoric was confusing, if not jarring. One visitor penned that the day’s events, particularly the flag of Deseret, demonstrated that the “Mormons” were “upstart traitors” and their leaders “desperadoes.” He gleefully recorded that in the evening a strong wind toppled the liberty pole, the flag plummeting into the dirt. He thought it a fitting omen. Historically it would be.[15]

The events behind the creation and unfurling of the flag of Deseret witness that church leaders and the electioneers remained loyal to the theodemocracy of Joseph’s political campaign. Just as the 1849 commemoration was planned and executed largely by electioneers, their work for the kingdom was the reality behind the rhetoric and symbolism of the day. Veterans of the electioneer cadre, under the direction of church leaders, formed the foundation of the emerging aristarchy of the Great Basin kingdom. Their previous faithfulness and work for the campaign and in other “measures” of Joseph ensured that. Ultimately, Deseret would only last a few years, but its replacement, the Territory of Utah, would function as a form of theodemocracy for several decades. Yet in the end the winds of change blown by the federal government would bring the flag, and the kingdom it represented, crashing down.[16]

The State of Deseret

Beginnings

Brigham Young and his vanguard company arrived in the Salt Lake Valley as exiles. Before evacuating Nauvoo, Brigham declared that the Saints “owed the United States nothing, not a farthing, not one sermon. . . . They have rejected our testimony, killed our prophets; our skirts are clear from their blood. We will go out from them.”[17] And so they did. Electioneers still on preaching missions in the United States shared similar sentiments. Norton Jacob mocked the “republican Spirit of the People” who had driven them out. “God deliver me from such a government!!”[18] In 1847 electioneer William I. Appleby wrote, “The American nation is yet at war with Mexico, . . . the American arms thus far proving victorious. [Yet] the race is not always to the swift, nor the battle to the strong,” he added, perhaps expressing hope for an outcome that would leave the nascent Zion safely beyond US borders. “But may our Heavenly Father’s will be done,” he concluded.[19]

In 1848 the United States defeated Mexico in short order. The following year, Appleby now saw in the American victory, coupled with the revolutions in Europe, God’s hand in “rending to pieces” the “kingdoms of the Gentiles.” Now American “Republicanism” could spread and “prepare the way . . . that the gospel may be proclaimed . . . by the servants of God” so that the “honest in heart” could receive it and gather to Zion and “not perish with the wicked and ungodly of the gentile kingdoms.”[20] This collective feeling of fundamental respect for American institutions, but disdain for those in power and their treatment of the Saints, strongly influenced how Brigham conducted political affairs in the Great Basin.

The vanguard company of 1847 quickly went to work building the new Zion. Former electioneers were heavily involved. Surveyor Henry G. Sherwood helped Orson Pratt lay out the new city in the grid design of Joseph’s original Zion plat. The soil was so rocky in areas that Levi N. Kendall’s plow broke. They built a dam on a creek to provide irrigation. Lorenzo D. Young planted the first flowers and vegetables in the valley. Levi W. Hancock harvested the first crop of wheat. Expeditions went north, south, and west to scout the surrounding geography. Joseph Mount and Jedediah M. Grant and a few others explored the Great Salt Lake and its environs. The company’s leaders gave Isaac and John D. Chase permission to build mills on area creeks. Osmon Duel constructed the first log home in the valley, while George W. Langley built the area’s first adobe abode. Brigham sent electioneers Henry G. Sherwood, Jesse C. Little, and Daniel Spencer to buy out Miles Goodyear, the only other American in the area, with gold from electioneers discharged from the Mormon Battalion.[21]

On 26 August 1847 Brigham and several others departed for Iowa. Before leaving, they organized a high council with municipal duties, mirroring the one in Winter Quarters. The apostles, as presiding members of the Council of Fifty, were purposely planting theodemocracy in the valley. Brigham instructed, “It is the right of the Twelve to nominate the officers, and the people to receive them.”[22] They chose John Smith, Joseph’s uncle, who was coming in a subsequent pioneer company, to preside. They nominated electioneers Charles C. Rich and John Young as his counselors. Seven of the twelve members of the high council were also electioneers. Like the Winter Quarters Municipal High Council, Brigham gave the Salt Lake High Council religious, political, and economic authority to “observe those principles which have been instituted in the stakes of Zion for the government of the church, and to pass such laws and ordinances as shall be necessary for the peace and prosperity of the city for the time being.”[23]

The municipal high council, acting under its mandate to protect the “peace, welfare and good order of [the] community,” enacted laws “for the government and regulation of the inhabitants of this . . . valley.”[24] The first ordinances targeted idleness, disorder, sexual misconduct, stealing, drunkenness, and cursing. Zion’s prerequisite of righteousness remained. The council acted as a unified legislative, judicial, and executive entity like the Winter Quarters Municipal High Council—an echo of Joseph’s combined government in Nauvoo. It adjudicated all issues, including a quarrel between electioneers Isaac Chase and Ira S. Miles over flour. Meanwhile, in Winter Quarters the gathered Quorum of the Twelve reorganized the First Presidency on 27 December 1847, naming Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, and Willard Richards as its members. When church leaders returned to the Salt Lake Valley the following summer, they found the valley Saints barely alive. With fresh supplies, the settlement survived.[25]

Theodemocracy Firmly Planted

The US victory over Mexico made the Great Basin US territory. The Saints were now back in the nation they had fled—the nation that had exiled them. Throughout 1848 church leaders debated how to obtain political autonomy for their new Zion. Options included a petition to become a federal territory, become a new state in the Union, or have total independence. For information helpful in their deliberations, they relied on apostles George A. Smith and Ezra T. Benson (the latter a former electioneer), who were in the East on a fundraising mission. In a June dispatch they explained that since a treaty had not yet been approved, it was impossible to determine which nation will “have jurisdiction over the basin, . . . but as we are in the possession of the soil, our destiny would be independence should Mexico maintain her old lines.” While a decision to join the United States “would give us facilities for doing business by agents in the US and thus save great expense and loss, . . . we go in, for once in all our life, if possible, to enjoy a breath of sweet liberty and independence.”[26] Smith and Benson would soon learn that the Mexican and American congresses had ratified a treaty—the Great Basin was already American.

Smith and Benson sent a second letter in October. Now they discouraged seeking territorial status because the Saints might fall victim to “starved office seekers . . . to be governor, judges and big men, irrespective of the feelings and rights of the hardy emigrants who had opened the country,” as had happened in Oregon. Their counsel echoed that of the Saints’ advocate Thomas L. Kane. Meeting the next year with apostle Wilford Woodruff and John M. Bernhisel (a former electioneer), Kane advised, “You are better without any government from the hands of Congress than with a territorial government, [because] the political intrigues of government officers will be against you. You can govern yourselves better than they can govern you; . . . you do not want corrupt political men from Washington strutting around you.” Kane believed that the Saints were in a position of strength to negotiate statehood. “You have a government now, which is firm and powerful,” Kane wrote, “and you are under no obligation to the United States.”[27]

Kane referred to the government that Brigham and the Council of Fifty had created and were administrating. After establishing a quorum on 9 December 1848, the Council of Fifty prepared paperwork to follow California and New Mexico in applying for statehood. They discussed boundaries and a name for the new state. Choosing the Book of Mormon word Deseret, meaning “honeybee,” they highlighted their collective effort to build Zion. In the petition, Deseret ambitiously claimed all modern-day Utah and Nevada, as well as western Colorado and New Mexico, most of Arizona, and southern California. Since the Saints were the only organized Americans in the region, such an expanse of territory seemed possible. The Council of Fifty nominated Brigham Young for governor and other members to fill other executive positions. On 6 January 1849, the council delegated John M. Bernhisel to deliver the statehood petition to Washington. Then it was resolved that “the [Salt Lake] high council be relieved from municipal duties.”[28] So it was that the electioneer-laden Council of Fifty officially assumed the functions of government from the electioneer-laden municipal high council.

Throughout the winter and spring, the Council of Fifty governed temporal affairs through regular meetings and committees. It made decisions about all aspects of the growing colony: cattle storage, bridge construction, specie circulation, food scarcity, price inflation, taxation, crime, destruction of predatory animals, cemetery location, and reconstitution of the Nauvoo Legion. Some believe that Brigham and his associates made these decisions simply to fill the vacuum of governance. Yet in reality, their underlying intent coincided precisely with the mission of the Council of Fifty—to create a government as a shield for Zion based on Joseph’s theodemocratic principles. On 1 February 1849 the Council of Fifty gave notice of a convention scheduled for 5 March in Salt Lake City “for the purpose of taking into consideration the propriety of organizing a territorial or state government.”[29]

Church leaders then switched hats and turned to reorganizing the priesthood, after which they would align theodemocracy to that ecclesiastical framework. In early February 1849, they restructured the high council into a formal stake of Zion. Daniel Spencer was president of the Great Salt Lake Valley Stake with David Fullmer and Willard Snow as counselors. Church leaders then named Spencer mayor of Great Salt Lake City. The entire stake presidency and a third of the high council consisted of electioneers.[30] The high councilors doubled as city councilors. This fledgling theodemocracy governed Saints and gentiles alike. As gold seekers stopped in Salt Lake City in 1849, they had no choice but to have their grievances heard before Daniel Spencer and his high council. Some felt justly dealt with. Others did not, spreading their misgivings far and wide. In the coming years, as the number of outsiders in Salt Lake Valley increased, Latter-day Saint political dominance would lead to conflict as it had in Nauvoo.[31]

On 12 February 1849, in the home of electioneer George Wallace, Brigham called four new apostles. They filled the vacancies created by the reconstitution of the First Presidency and the excommunication of Lyman Wight. All four were electioneers—Charles C. Rich, Franklin D. Richards, Erastus Snow, and Lorenzo Snow. They joined fellow electioneer Ezra T. Benson, called to the apostleship in 1846. Not coincidently, since Joseph’s murder, all five men who became apostles were veterans of Joseph’s election campaign.

Two days later, Brigham divided the city/

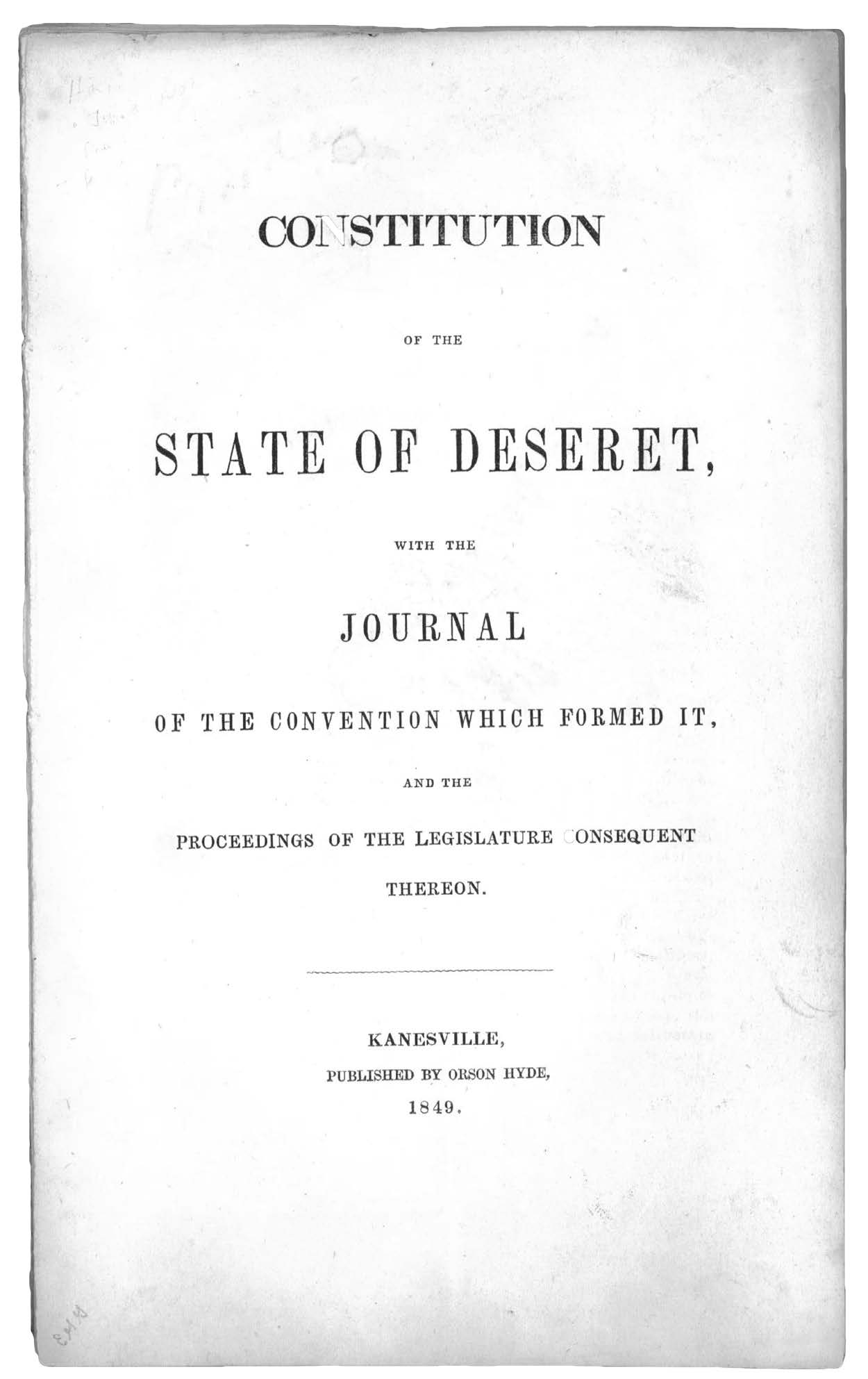

That the constitution was prepared in less than two days strongly suggests that the Council of Fifty had crafted it previously. The final product was loosely based on the Constitution of Iowa, ratified in 1846. In Nauvoo the Council of Fifty had operated as a “living constitution,” freely exercising the liberal powers of the Nauvoo Charter in pursuance of theodemocracy. Now in the position of needing federal approval for statehood, the council presented a proposed constitution that was palatable to Americans. The “living constitution” of the Council of Fifty would continue to pull the levers of theodemocratic power, but behind a governmental framework the rest of the nation could accept. On Saturday, 10 March 1849, the convention debated and then adopted the Constitution of the State of Deseret.

The Constitution of the State of Deseret gave formal structure to the “living constitution” of the Council of Fifty’s theodemocracy, protecting the new Zion in the

The Constitution of the State of Deseret gave formal structure to the “living constitution” of the Council of Fifty’s theodemocracy, protecting the new Zion in the

West. Image courtesy of Harold B. Lee Library Digital Collections, BYU.

The Council of Fifty also met that day, and the council’s committee on elections “presented the election ticket.”[36] On Monday, 12 March, electioneer Hosea Stout recorded, “Today was our first political election. . . . A large assemblage of men convened when many subjects were discussed. . . . There [were] 655 votes polled for the following offices: Brigham Young for governor; Willard Richards for secretary; H. C. Kimball, chief justice; N. K. Whitney and John Taylor, associate judges; H. S. Eldredge [electioneer], marshal; D. H. Wells, attorney-general; N. K. Whitney, treasurer; A. Carrington, assessor and collector; Jos. L. Heywood [electioneer], supervisor roads.”[37] Additionally, the male populace elected all nineteen bishops as justices of the peace for their wards. In early May, with the trail reopened, electioneer veteran John M. Bernhisel headed for Washington with copies of the petition and the constitution and a list of the officers of Deseret.

The process of religious leaders writing a state constitution, nominating candidates based on aristarchy, and ratifying elections in unanimous voting was and is foreign to the American political experience. Joseph’s ideal of aristarchic theodemocracy was radical and outside accepted notions of American governance. It is no coincidence that the Council of Fifty held the election on 12 March, the fifth anniversary, almost to the day, of Joseph’s organization of the body. If the United States accepted Deseret, Brigham and the Council of Fifty would have what they wanted. The theodemocratic kingdom of God would be an official government entity, one that was independently created but protected under the wing of the American eagle. It appeared that Zion had a chance of finally being secure.

The creation of Deseret was exclusively the domain of the Council of Fifty. It called the convention, assigned its members to the drafting committee, and approved the document before ratification. That the convention adopted the constitution verbatim demonstrates the broad and uncontested authority of the Council of Fifty in the Deseret theodemocracy. Latter-day Saints looked to their leaders as prophets inspired by heaven and, by common consent, routinely voted to sustain them as their ecclesiastical leaders. The same was true on the political side of the coin. The Council of Fifty was tasked to operate political Zion, and its ranks contained all the leaders of the church. It made the decisions that the rest of the population voted to accept. The result was unity, which was what the Saints valued above all else—even freedom.

Yet while the electioneers and other Latter-day Saints celebrated their theodemocracy, most citizens of the United States viewed the developments with suspicion. For many, Deseret seemed a despotic, theocratic kingdom of religious zealots led by conspiring, unpatriotic men duping uneducated commoners and foreigners. What Latter-day Saints believed was humble obedience to prophets called to build up God’s kingdom, other Americans saw as an autocratic, dangerous, and expanding empire amid their nation, which now spanned the continent. Deseret represented a potential outpost of treason in a nation committed to the separation of church and state. Adding polygamy to the equation, Latter-day Saints appeared not only undemocratic but also immoral. When federal authorities reacted, the Saints huddled closer to their leaders. They viewed every government decision as oppression, reinforcing the strong feelings of persecution that had forced them into the wilderness. This created forty years of conflict between Latter-day Saint theodemocracy and the United States government for political control of the Intermountain West—the “Mormon Question.”[38]

One searches antebellum American history in vain to find similarities to Latter-day Saint theodemocracy. The two-party system dominated politics, and Democrats and Whigs gathered adherents from diverse religions. Catholics were the exception. Like Latter-day Saints, many Catholics were recent immigrants. Numerous Americans accused Catholics of following the pope instead of political authority. The Catholic response was to assimilate into the Democratic Party, where they found political power and protection. This was much different than the Latter-day Saints forming their own government as a kingdom on earth preparing for the return of Jesus Christ. Ironically, the mechanics of Latter-day Saint theodemocracy mirrored party politics in one important aspect—those who governed the political process were elites. But that’s as far as the comparison goes. The Latter-day Saint elites nominated one candidate for each office, whom the faithful then voted to approve, there being only one choice. In contrast, with the political parties, the electorate could choose between two different candidates, two different platforms.

For two years the provisional State of Deseret governed the Great Basin. It was no coincidence that most of its “elected” officers were Council of Fifty members, electioneers, or both. The General Assembly convened on 2 July 1849 for its first session despite no elections having taken place for the House and Senate. Ostensibly, the Council of Fifty’s committee of elections chose and elected the candidates between the March constitutional convention and July. That arrangement begs the question, Where did sovereignty lie? In Deseret it rested with God and was interpreted and exercised by church leaders. The Saints willingly acquiesced to those decisions. Not surprisingly, electioneers filled Deseret’s House of Representatives and Senate.

The General Assembly passed no legislation in its first session. There was no need to. The Council of Fifty had run the temporal affairs of the Great Basin kingdom since January, and as the living constitution, the council continued to direct proceedings without legislation. In fact, “the formal establishment of the State of Deseret . . . was little more than a de jure confirmation of a de facto situation.”[39] The council’s purpose was more to secure statehood than to govern. The machinery of state fronted the religious elite to placate American public opinion. However, the State of Deseret did give the Council of Fifty the means and personnel to extend its mission to even the most remote Latter-day Saint colony.

Perhaps the most important piece of legislation passed concerned the creation of unique probate courts. The governor and legislature appointed these judges. Because Council of Fifty members filled the executive and legislative branches of Deseret, their chosen jurists became projections of the council to plant and protect local theodemocracy throughout the Great Basin. Naturally, probate judges were disproportionally electioneers. These judges exercised extensive influence in the county governments of Deseret and later in Utah Territory. They chose the first county officers and exercised authority comparable to that of county commissioners. Because many of their decisions were judicial and autonomous, the “living constitution” nature of governance continued. In 1852 the probate courts would be given jurisdiction of all civil and criminal cases and, three years later, original jurisdiction equal to that of federal district courts.

In Washington, DC, in 1849, federal representative of Deseret John M. Bernhisel had orders to obtain for Deseret “admission as a sovereign and independent state in the Union upon an equal footing with the original states.”[40] However, negative feelings in Congress and contemporary events defeated this effort. In the aftermath of the Mexican-American War (1846–48), the territory of the United States nearly doubled. Friction over the slavery question in this new territory was overheating dangerously. The famous Compromise of 1850 settled the differences for a decade. One part of the pact created Utah Territory, significantly stripped in size from Deseret. The territories of Utah and New Mexico would also operate under popular sovereignty—where the populace in the territory would decide whether or not to permit slavery. Bernhisel lobbied US president Millard Fillmore to fill the Utah territorial offices with Latter-day Saints. However, fearing that the Senate would not accept an “all-Mormon slate,” Fillmore split the offices between Latter-day Saints and gentiles.

In February 1851 Brigham learned that Fillmore had appointed him governor and that he was responsible for taking a census and creating legislative districts. Church leaders acted promptly to adopt and expand the idea of popular sovereignty into a bulwark for defending Zion through self-rule. In March the General Assembly of Deseret voted to dissolve itself. In his role as governor, Brigham administered a census and held new elections, all before the gentile officers arrived. Questionable in its legality, the preemptive strike showed Brigham’s desire to create the territory as much in the image of Deseret as possible before outsiders interfered. The new legislature reelected Bernhisel as the territory’s delegate to Congress and reenacted most laws of Deseret as territorial law. Though Brigham and the Council of Fifty governed Deseret for only two years, they had created institutions that would allow abundant autonomy for decades to come.[41]

Cadre Religious Contributions

Ordinations

In 1850 the call of five new apostles—all electioneers—was only the beginning of electioneer advancement in priesthood responsibilities. Between 1844 and 1850, Church leaders called many electioneers to priesthood offices of significant responsibility. Electioneers saw sizable increases in the offices of seventy (248 percent), high priest (143 percent), bishop (530 percent), and apostle (667 percent). The increase in seventies is logical because most elders under thirty-five became seventies at the October 1844 Nauvoo conference. However, the increases in the other offices reflect the continuing and even growing confidence of church leaders in the leadership capabilities of the electioneer cadre. Perhaps the percentage of those who held high priesthood office is not as good an indicator of electioneer loyalty, faithfulness, and leadership ability as the number of available leadership positions they held. Again, in 1850 all five new apostles were electioneers. Recall as well that Daniel Spencer presided over the church’s only stake of Zion and also that of the thirty-one wards or branches in the Great Basin, electioneers led eleven. The electioneers were fast becoming a dominant influence in the aristarchy that Brigham was fashioning as the religious superstructure of Zion.

Missionary Work

During this time of crisis and relocation, Brigham never lost focus on spreading the restored gospel. Of course, the electioneers were a well-qualified pool of prospective preachers. The missionaries who served in the United States concentrated on gathering scattered branches of the church to the Great Basin and raising money for their exodus. Libbeus T. Coons spent 1848 touring the eastern states and fundraising, which included writing letters to each state’s governor. Again in 1849, church leaders appealed to the citizens of the nation for financial aid, sending electioneers Ezra T. Benson, Amasa M. Lyman, Erastus Snow, and William I. Appleby to raise funds. Chapman Duncan proselyted in his native Virginia, finding his wife along the way. Edson Whipple labored with apostle Wilford Woodruff in the eastern states, urging members to emigrate to the West.

During the late 1840s, many former electioneer missionaries participated in the fruitful harvest of converts in the British Isles. Tragically, missionaries James H. Flanigan and William Burton died during their service. In addition to the work in England, apostle Erastus Snow and George P. Dykes labored in Scandinavia and then Germany, publishing the Book of Mormon and gospel tracts. Another electioneer, apostle Lorenzo Snow, journeyed to Italy, where he converted a small group of Protestants.

Electioneers serving as missionaries in Europe had a threefold purpose. First, they comforted the Saints regarding Joseph’s death. Elijah F. Sheets was the first post-martyrdom missionary in Europe. Of a conference in September 1844, he wrote, “I told them concerning the murder of Bro[ther] Joseph and Hyrum, and the bigger part of the congregation was [bathed] in tears, both saints and sinners.”[42] Crandell Dunn recorded, “I spoke at some length on the history of the church and the persecutions that the prophet Joseph Smith had met with and the death of him and his brother Hyrum.”[43] Second, they also proselytized. Between 1845 and 1850, more than thirty thousand converts joined the church in Great Britain alone. Third, the missionaries encouraged new Saints to gather to the Great Basin. Many of these missionaries had seen the new Zion and urged the converts onward. Before leaving England, Lorenzo Snow spoke to a large conference. “Upon the journeyings of the Saints in the wilderness, their settling in the valley of the Great Salt Lake, to their present and future prospects, both spiritual and temporal, the audience was very attentive to all [and] appeared to partake of the spirit of the speakers and he spoke by the Spirit of the living God.”[44] The message was clear. Zion was still alive—come help build it.

The Electioneers’ Rise in Responsibility, Means, and Influence

From 1847 to 1850, the initial work of building a desert kingdom required capable leadership in many areas and at many levels. As the main governing body in Deseret, the Council of Fifty led out in this regard and, as was true for the work of managing the exodus, often turned to the loyal and capable electioneer veterans for those leadership needs. As opportunities to work and lead in greater capacities came their way, the electioneers were enabled to rise in prominence and stature in the Great Basin theodemocracy. Their enlarged scope of influence grew out of their increasing involvement in political, social, and economic affairs stemming from their religious offices and stations.

From 1845 until 1850, the Council of Fifty added twenty-seven men to its ranks to fill vacancies caused by deaths and excommunications. Of those newcomers to the council, twelve (44 percent) were electioneers, well above their 10–13 percent representation among priesthood holders. In 1850 the Council of Fifty had fifty-six members, twelve of whom had been general authorities in 1844 and twenty-two of whom were veteran electioneers. Thus electioneers constituted 39 percent of the council (50 percent if not counting pre-1844 general authority members).[45] Because the Council of Fifty appointed the first officers of the government of Deseret, it is not surprising that electioneers were among those selected. In 1849 the Deseret House of Representatives had twenty-six members, twelve (46 percent) of whom were electioneers. Notably, electioneer Willard Snow was elected Speaker of the House. In the Senate, seven of the fourteen members were electioneers. Thus in 1850, electioneers made up fully half the members of the Council of Fifty and of the General Assembly of Deseret.[46] This high level of involvement in political affairs and the attendant perquisites positioned the electioneers to take on added responsibilities and contribute to the prosperity of Deseret in other spheres as well.

For example, though plural marriage was not publicly announced until 1852, many electioneers entered the practice in the 1847–1850 period. Twenty-seven percent had multiple wives—a percentage three times the norm. While most plural marriages involved two wives, electioneers averaged 2.7, with a median of three wives. Why the difference? Leaders were expected to set the example with plural marriage. As electioneers were elevated to positions of religious and political influence, they were able to enter into more plural marriages. In fact, the five electioneers who became apostles and political leaders had between three and six wives. Electioneer John D. Lee, Council of Fifty member and adopted son of Brigham, led his electioneer colleagues in this regard with eleven wives.[47]

For Saints loyal to Brigham, this period brought great poverty and suffering. They endured poor weather, crop failure, and legions of locusts. However, through strong leadership and cooperation, the colony in Salt Lake Valley grew and new ones were begun. Brigham’s vision was to colonize every habitable region in the Great Basin. He and other church leaders believed that ongoing missionary work and the establishment of the Perpetual Emigrating Fund would bring tens, perhaps hundreds, of thousands to the Great Basin. New colonies would provide homes for them. Also, if every desirable location held a Latter-day Saint colony, gentile settlement in the Great Basin would be minimal.

In all, Latter-day Saints settled fifty-two separate towns during these four years. Electioneers settled twenty-two of them. However, since the electioneers represented only about 10 percent of available priesthood men (owing to death and disaffection), their relative contribution was impressive. The average electioneer helped settle 1.2 colonies in the 1847–1850 period. This still left most of them in Salt Lake City, and the Council of Fifty used them to build up a strong capital. Even so, some electioneers had become colonizing experts by 1850. For example, Aaron F. Farr helped settle Salt Lake City, Big Cottonwood, and Irontown; and Joseph L. Robinson did the same for Bountiful, Farmington, and Irontown. Council of Fifty member and recently called apostle Charles C. Rich was similarly instrumental in the growth of Salt Lake City, Big Cottonwood, and Provo.[48]

Beginning with the colonization of what was called Great Salt Lake City in 1847, church leaders incorporated Zion principles of stewardship and inheritances into the distribution of land. They endeavored to avoid the real estate speculation of Kirtland and the competition of Nauvoo, both of which had fractured the church. Consequently, individual lots were given as “inheritances” and distributed by lottery. “No man can ever buy land here,” Brigham told immigrants in 1848, “for no one has any land to sell, . . . but every man shall have his land measured unto him, which he must cultivate in order to keep it.”[49] Speculation and division of inheritances were prohibited, “for the Lord [had] given it to [them] without price.”[50] Bishops distributed land equally “according to circumstances wants and needs,” in conformity with the law of consecration. People received their own land after paying a small fee to the recorder and surveyor. Two caveats in the process had great significance for the economic mobility of the cadre: single men could not receive an inheritance, while men with plural wives received separate lots for each family.[51]

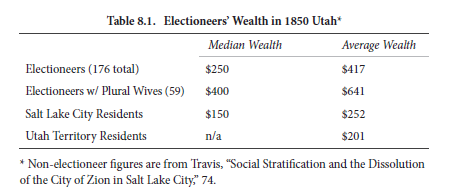

Electioneers in Utah had roughly twice as much wealth as their neighbors had, and those with plural wives had more than three times the wealth of their fellow Saints (see table 8.1). Entering into plural marriage guaranteed additional land. The wealthiest electioneer in Utah in 1850 was John D. Lee, whose estate was valued at $5,500. The second wealthiest was Ezra T. Benson, who became an apostle and member of the Council of Fifty in 1846, married five women, and was a councilor of the State of Deseret. His estate was worth $3,500. Alfred D. Young’s $250 estate was the median. An accomplished missionary in Tennessee, he immigrated to Utah in 1848. By 1850, he was a president of a quorum of seventy though monogamous and was renowned for his spiritual gifts.[52]

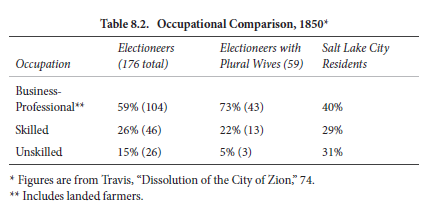

By 1850 most of the electioneers who had come to Utah were among the economic elite. As mentioned, their increased ecclesiastical and political responsibilities meant greater access to plural marriage and, concomitantly, land ownership. These advantages in large measure enabled them to become landed farmers and businessmen at almost twice the rate of their contemporaries at a time when Salt Lake City mirrored most other US towns and cities insofar as land ownership was generally lower than 40 percent (see table 8.2). Indeed, the electioneer veterans in Utah were already evolving into a landed economic elite.[53]

* * *

The electioneers’ role as church and political leaders and their willingness to enter into plural marriage translated into growing wealth and influence in the State of Deseret. Their zeal and proven ability in working to establish Zion as a unified religious, political, social, and economic kingdom brought the dream of a theodemocratic kingdom that much closer to reality. From the ashes of Joseph’s presidential campaign arose a leadership cadre uniquely equipped to help Zion bloom in the primitive territory of the Great Basin. In the three years after leading the Saints to the valley of the Great Salt Lake, church leaders bestowed abundant responsibility for building and administering Zion on the shoulders of Joseph’s electioneers. These men were prominent in administering temple ordinances, leading pioneer companies to the valley, colonizing new towns, and guiding the Saints as bishops and legislators. Their growing influence in the kingdom’s aristarchy would continue over the next two decades.

Notes

[1] Johnson, “Deseret,” Zion’s Songster, or the Songs of Joel, Book Third, Joel Hills Johnson Papers, CHL, 19 February 1853, 376; punctuation per Hymns of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1985), no. 5.

[2] Quoted in Jacob, Reminiscence and Journal, 28 July 1847.

[3] JSP, CFM:25 (11 March 1844).

[4] JSP, CFM:33 (19 March 1844).

[5] JSH, F-1:137.

[6] Lee, Journal, 13 January 1846, 79.

[7] See Bullock, Council Meeting Minutes, 26 February 1847, as quoted in Walker, “‘Banner Is Unfurled,’” 75–76.

[8] Bullock, Council Meeting Minutes, 26 February 1847, as quoted in Walker, “‘Banner Is Unfurled,’” 84.

[9] The electioneer bishops were John Lowry, Benjamin Brown, William G. Perkins, David Pettegrew, Edward Hunter, Abraham O. Smoot, and Joseph L. Heywood.

[10] Eliza Snow, Record of Lorenzo Snow, 97.

[11] Eliza Snow, Record of Lorenzo Snow, 97, 98.

[12] Eliza Snow, Record of Lorenzo Snow, 99, 100.

[13] Eliza Snow, Record of Lorenzo Snow, 103–105. For a full account of the celebration, see pp. 96–107.

[14] Johnson, “Deseret.”

[15] Walker, “‘Banner Is Unfurled,’” 86.

[16] After Deseret became Utah Territory, the flag of Deseret was rarely seen. It was displayed on the day of Brigham’s funeral and then placed in his casket.

[17] Jesse Wentworth Crosby, Autobiography, 6 October 1845.

[18] Jacob, Reminiscence and Journal, 16.

[19] Appleby, Autobiography and Journal, 166.

[20] Appleby, Autobiography and Journal, 220–21.

[21] See “Salt Lake’s Original Nineteen LDS Wards.” See also Kate Carter, Heart Throbs of the West, 12:208.

[22] Quoted in Egan, Pioneering the West, 127.

[23] Journal History of the Church, 9 September 1847. The high council was composed of electioneers Henry G. Sherwood, Levi Jackman, Daniel Spencer, Edson Whipple, John Vance, Willard Snow, and Abraham O. Smoot. The other members were Thomas Grover, Stephen Abbott, John Murdock, Ira Eldredge, and Shadrach Roundy.

[24] Journal History of the Church, 27 December 1847.

[25] “Pioneer Forts of the West: High Council Meetings,” Utah, Our Pioneer Heritage (database). The incident occurred on 11 October 1847.

[26] Journal History of the Church, 28 June 1848.

[27] Quoted in Morgan, State of Deseret, 69–70.

[28] Journal History of the Church, 6 January 1849.

[29] Constitution of the State of Deseret, 1.

[30] The high council members were Isaac Morley, Phineas Richards, Shadrach Roundy, Titus Billings, Eleazer Miller, Ira Eldredge, William Major, Edwin D. Woolley, and former electioneers Henry G. Sherwood, John Vance, Levi Jackman, and Elisha H. Groves.

[31] See Journal History of the Church, 6 and 14 February 1849; Jenson, “Daniel Spencer,” in Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia; and Unruh, Overland Emigrants and the Trans-Mississippi West, 262.

[32] The bishops were John Lowry, Benjamin Brown, William G. Perkins, David Pettigrew, Edward Hunter, Abraham O. Smoot, and Joseph L. Heywood.

[33] Journal History of the Church, 4 March 1849.

[34] Lee, Diaries of John D. Lee, 98–110. The council replaced electioneer John M. Bernhisel with electioneer Horace S. Eldredge as marshal because Bernhisel would be leaving for Washington.

[35] Journal History of the Church, 5 March 1849. The committee consisted of Albert Carrington, Parley P. Pratt, John Taylor, and electioneers William W. Phelps, Charles C. Rich, David Fullmer, Joseph L. Heywood, John S. Fullmer, Erastus Snow, John Taylor, and John M. Bernhisel.

[36] Journal History of the Church, 10 March 1849.

[37] Stout, Diary of Hosea Stout, 2:348.

[38] Fred Rogers, Unpopular Sovereignty, 3.

[39] Klaus Hansen, Quest for Empire, 157.

[40] Brigham Young to Orson Hyde, in Journal History of the Church, 19 July 1849.

[41] See Rogers, Unpopular Sovereignty, 63–64.

[42] Sheets, Journal, 22 September 1844.

[43] Dunn, “History and Travels,” 1:165.

[44] Cutler, Diary, 9 May 1850.

[45] See Quinn, “Council of Fifty,” 22–26. I use the term general authority to refer to those of the church’s three presiding quorums—the First Presidency, the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, and the seven Presidents of the Seventy. Use of the term here is not anachronistic. It was first used in print by the church in the 1835 edition of the Doctrine and Covenants and has since been used to describe the highest officers of the church.

[46] See Morgan, State of Deseret, 35–36; Cadre representatives were Willard Snow, David Fullmer, John S. Fullmer, John Pack, Joel H. Johnson, Lorenzo Snow, Joseph A. Stratton, George B. Wallace, Jedediah M. Grant, Jefferson Hunt, Franklin D. Richards, and Hosea Stout; Cadre state counselors were Reynolds Cahoon, William W. Phelps, John Young, Daniel Spencer, David Pettigrew, Abraham O. Smoot, and Charles C. Rich.

[47] See Danel W. Bachman and Ronald K. Esplin, “Plural Marriage,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 1091.

[48] See Beecher, “Colonizer of the West,” in Lion of the Lord, 173–207.

[49] Quoted in Beecher, “Colonizer of the West,” 173.

[50] William Clayton’s Journal, 28 July 1847, 326.

[51] For an example, see electioneer Elisha Groves, who served as bishop and legislative representative for Parowan, established in 1851. Journal History of the Church, 16 May 1851.

[52] Many electioneers who did not follow Brigham west held considerable wealth. John Duncan, a follower of Sidney Rigdon, owned thirty thousand dollars of land in Pennsylvania. Amos Davis, a merchant just outside Nauvoo had assets amounting to three thousand dollars. George Pew, a plantation overseer in Louisiana, and John Swackhammer, a carpenter in New York City, each had recorded wealth of twenty-five hundred dollars.

[53] See Travis, “Dissolution of the City of Zion,” 153–54.