Contributions to the Succession and Exodus, 1844–1847

Derek R. Sainsbury, “Contributions to the Succession and Exodus, 1844-1847,” in Storming the Nation: The Unknown Contributions of Joseph Smith’s Political Missionaries (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 171‒200.

“I prophesied that the Saints would . . . be driven to the Rocky Mountains, many would apostatize, others would . . . lose their lives in consequence of exposure or disease, and some of you will live to go and assist in making settlements and build cities and see the Saints become a mighty people in the midst of the Rocky Mountains.”[1] —Joseph Smith, 6 August 1842

Electioneer Experience: Abraham O. Smoot. When on 8 July 1844 newspapers alerted Abraham O. Smoot to the prophet’s murder, he and the electioneers he led in Tennessee resolved to depart for Nauvoo. Along the way they informed and comforted their colleagues and other Saints about Joseph’s death. They spent several days canoeing up the Mississippi, reaching St. Louis in time to catch the riverboat Osprey. After four days they arrived at Nauvoo’s wharf on 28 July, where Smoot was greeted by his wife and a number of other Saints. He thanked the riverboat captain for transporting them without charge.

“I found the Saints in the city in fine spirits as to the general prosperity and progress of the great cause of Zion,” Smoot observed, though he also perceived that “a melancholy gloom seemed to prevail [in] the city.” Indeed, “in every countenance there was pictured sadness and sorrow, and every breast seemed to feel the fatal blow that had been struck . . . [by] the assassination and martyrdom of our prophet and patriarch, . . . who [were] beloved by all the Saints as dear as life.”

“These are days long to be remembered by me,” Smoot continued, “for there seemed to be temptations present themselves on every hand by aspiring spirits and otherwise. . . . As it was after the days of crucifixion of the Savior that many of the Saints [were] returning to their former occupations in life, supposing that . . . all their works had been in vain. So it seemed to be with some of the Saints in Nauvoo. . . . They [were] returning some to their merchandise, others to their former homes, while some [were] actuated by an aspiring spirit wishing to feed the Church of Christ in the absence of Joseph and Hyrum, when God had not called them to that office. . . . [T]he great body of Saints did not want them to rule over them.” Smoot was directly referencing Sidney Rigdon’s failed attempt to become “guardian” of the church.[2]

Electioneer Experience: Lorenzo H. Hatch. Eighteen-year-old Lorenzo H. Hatch left Nauvoo on 15 April 1844 to preach and politick. His favorite uncle, Jeremiah Hatch, had given him his last “twelve and a half cents and regretted that he had no more to give.” It was the first mission for Hatch and his companion, Thomas E. Fuller. After a difficult journey filled with many nights of sleeping “on the hard, cold ground, sometimes in the rain,” they reached Fuller’s family home in Saratoga Springs, New York, on 28 May. Extremely ill from exposure, Hatch convalesced there and fell in love with his nurse, Fuller’s younger sister Hannah. Upon recovery, Hatch departed on 17 June for his assignment in Vermont, where he preached his first sermons at some of his relatives’ homes. Receiving positive responses, his confidence grew.[3]

On 27 June, the day Joseph was assassinated, Hatch traveled to Northfield with fellow electioneers John D. Chase and Alvin M. Harding. There they planned to attend the Vermont conference directed by Erastus Snow. Snow never showed, so his companion William Hyde presided. Snow had felt a “dreadful pressure of sorrow and grief and sense of mourning than I had ever before felt, but knew not why.”[4] He left to rendezvous with members of the Twelve in Salem, Massachusetts. Hyde conducted the conference, recording, “We had a very interesting time.” Throughout the two-day meeting, “the course to be pursued [in] the ensuing presidential election by all the Saints throughout the Union was laid before the people.” The electioneering of Hyde, Hatch, and the other missionaries was “met with a hearty response” from Saints and gentiles alike.[5]

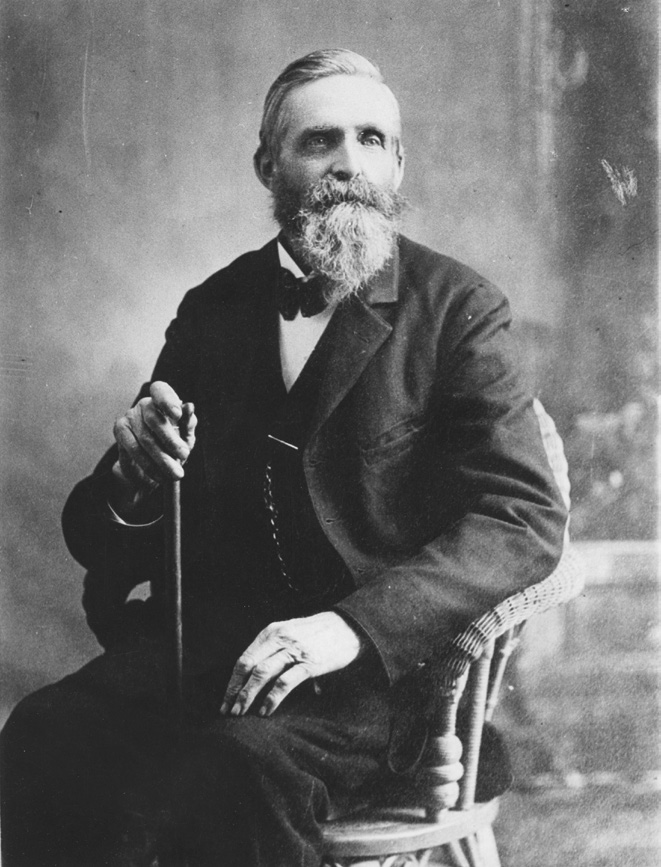

At age eighteen in Vermont, Lorenzo H. Hatch learned of Joseph’s death. He heard a

At age eighteen in Vermont, Lorenzo H. Hatch learned of Joseph’s death. He heard a

voice say, “Brigham Young is the man God has chosen to fill the vacancy.” Courtesy of Church History Library.

However, the next week they learned that Joseph had been killed. “At first I could not believe it,” Hatch wrote, “but at last was convinced that it was a fact.” He “mourned and wept as the children of Israel did when Moses was taken from them. I was alone, a young man being but eighteen years old, 1,500 miles from home. The question in my mind was, Who would lead the church now that the Prophet Joseph was gone?” A possible answer arrived in the mail in August. The letter from Hatch’s uncle Jeremiah stated plainly that “the Lord had called Sidney Rigdon to lead the church.” Hatch recalled, “It was about noon. I stood in the middle of the sitting room reading the letter to my cousin when a voice plain and distinct said, ‘Brigham Young is the man God has chosen to fill the vacancy.’” Hatch turned to his cousin and shared the truth with joy. He stayed in the East until the next spring, preaching the apostles as the legitimate leaders of the church. He returned to Nauvoo with Hannah, who had eloped with him.[6]

* * *

In the aftermath of Joseph’s death, most commentators predicted the end of the church. They believed that deceived followers would flounder while looking for a new prophet and scatter. While some church members wandered and others made claims of prophetic succession, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints did not die. Most of the Saints followed Brigham Young, president of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. Church leaders finished building the temple, administered its sacred ordinances, and organized a mass migration to the West. Despite difficulty, tragedy, and even death, the church not only survived but strengthened. Brigham and the Council of Fifty established the State of Deseret, an independent, theodemocratic government to protect the new Zion. From the first weeks following Joseph’s assassination to the creation of Deseret, church leaders made electioneers leaders in organizing, moving, and establishing Zion. Indeed, the electioneers were well suited to leadership callings. Their demanding missions had concretized Zion and theodemocracy in their hearts; and the assassination, while shocking and traumatizing, fortified their desires to finish “Joseph’s measures.”[7]

Shared trauma turned to united action. The apostles had labored throughout the country alongside these men, sharing missionary trials and triumphs and the agony of Joseph’s death. It was natural for church leaders to look to the cadre of electioneers—whose desires were aligned with those of church leaders, whose loyalty had been tried, and whose names, abilities, and characters were known—to help lead the movement. They understood theodemocracy well, having advocated and suffered for it, and their minds were one with church leaders. No one could discount their unique preparation, as a body and to the man, to push the Lord’s work forward. It is no surprise, then, that many electioneers emerged in the aristarchy as those on whom Brigham, the Quorum of the Twelve, and the Council of Fifty placed responsibility to assist in leading the Saints to the Great Basin and advancing the cause of Zion thereafter.

Succession

Brigham Young

The electioneers who returned in July and early August 1844 found Nauvoo in mourning and confusion. Rival factions coalesced around potential heirs to Joseph’s role as church president. On 8 August Joseph’s former counselor Sidney Rigdon and chief apostle Brigham Young addressed the Nauvoo Saints. Rigdon, a gifted orator but unstable leader, spoke for several hours until his voice gave out. He declared himself the church’s “guardian” by angelic revelation and through his decade-long role as the prophet’s counselor. Brigham spoke briefly, asserting that the keys of the kingdom were with the Twelve and that no one could come between the apostles and Joseph.

While Brigham spoke, some electioneers were among those who heard Joseph’s voice or saw Joseph’s face in place of Brigham’s. Their miraculous experiences helped convince them to accept Brigham as Joseph’s divinely approved successor. William Hyde recalled, “The voice of the same spirit by which Joseph spake was this day sounded in our ears, so much so that I once, unth[inking]ly, raised my head to see if it was not actually Joseph addressing the assembly.”[8] Jacob Hamblin wrote, “The voice and gestures of the man [Brigham] were those of the Prophet Joseph. The people, with few exceptions, visibly saw that the mantle of the Prophet Joseph had fallen upon Brigham.” Rising to his feet, Hamblin declared to the man beside him, “That is the voice of the true shepherd—the chief of the apostles.”[9] For Nathan T. Porter, as Brigham arose “to speak to the people he was transfigured into Joseph’s likeness in looks, appearance, and the sounding of his voice so that a low whisper ran through the vast assembly—‘that’s Joseph’—‘that’s Joseph.’”[10] Robert S. Duke, the young son of Jonathan O. Duke, sensed the speaker was Joseph, a frequent visitor in their home. He turned to his father and said, “Look, Papa, the Prophet is not dead.” His father responded, “Hush, son, and remember this.”[11]

The gathered congregation voted to follow the Twelve. Brigham soon declared, “You are now without a prophet, . . . but you are not without apostles who hold the keys of power . . . to preside over all the affairs of the church in all the world; being under direction of the same God.” Regarding Joseph’s presidential campaign, he announced, “As rulers and people have taken counsel together against . . . [Joseph], and have murdered him who would have reformed and saved the nation, it is not wisdom for the Saints to have anything to do with politics, voting, or president-making, at present.”[12] The campaign was officially over. Most Latter-day Saints, in Illinois and in the East, returned to their roots and voted for Democrat James K. Polk, who narrowly defeated Henry Clay.

Members of the electioneer cadre overwhelmingly transferred their fealty to Brigham and the Twelve. A staggering 83 percent stayed loyal through the 1846 evacuation of Nauvoo. Three-quarters tarried through Winter Quarters. Seventy-one percent remained loyal to Brigham as they traveled into the Great Basin, and 64 percent were loyal until their death. Besides the miraculous manifestation that some experienced, other factors led to their decision to follow Brigham. First, because they regarded the apostles as fellow electioneers firmly committed to Zion, they wanted to assist their comrades in finishing “Joseph’s measures.” Brigham and the other apostles moved quickly to consolidate control of the church in order to prevent further schism. In the October 1844 general conference, they added dozens of seventies quorums with more than four hundred new members, half of whom had been electioneers. This placed them under the Twelve, instead of under local, sometimes wavering leadership. Heber C. Kimball boasted that the apostles had “fourteen or fifteen hundred seventies to carry out our measures.”[13]

Brigham then acted on Joseph’s pronouncement that Zion was to encompass all of America. Under his direction the apostles chose eighty-five trusted high priests to relocate, each to a key congressional district where they were to build up church congregations and then return to Nauvoo with their converts so they could receive their endowments. These high priests then would move back with their initiates to their assigned areas and seek to establish stakes of Zion. Forty-four of the eighty-five high priests (52 percent) were chosen from the electioneer cadre, recently returned from months of electioneering.[14] The electioneer cadre was represented disproportionately well in this group, given the fact that when they left on their missions, they accounted for only about 15 percent of potential priesthood holders. Yet using so many of the electioneers as leaders in building up Zion made sense—they were experienced missionaries who had worked earnestly to organize political and religious work throughout the nation. That field experience would surely stand them in good stead in the related work of building up stakes. However, persecution drove the Saints from the nation before most of the cohort of high priests could begin their missions.[15]

Other Successors

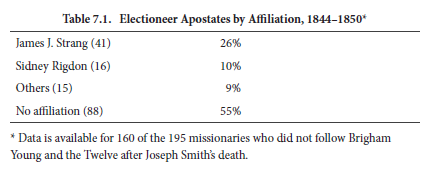

Although Brigham and the apostles were firmly in control of the church organizationally, only half of the Latter-day Saints followed them west. Shocked at the sudden loss of their prophet, many simply left the church or chose to let the church leave them. This attrition involved the electioneers as well, though at a much lower relative percentage. For various reasons, some electioneers looked not to Brigham but to other aspirants to Joseph’s mantle, such as Sidney Rigdon, James J. Strang, William Smith, Lyman Wight, James Emmett, James Brewster, and Charles B. Thompson (see table 7.1).[16] In all, more than half of the electioneers (55 percent) who did not follow Brigham simply quit the Latter-day Saint movement altogether.

Defeated in Nauvoo, Sidney Rigdon decided to organize his own church. Rigdon and some followers scoured the eastern branches for adherents. On 6 April 1845 in Pittsburgh, Rigdon organized the Church of Christ. His church mirrored Joseph’s Zion ideal except for plural marriage, an omission that no doubt attracted some members. Disaffected electioneers were prominent in Rigdon’s movement, as they were in the other splinter groups. Rigdon’s first presidency included his son-in-law and former electioneer Ebenezer Robinson. Rigdon called twelve apostles, four of whom had been electioneers: Hugh Herringshaw, Benjamin Winchester, Elijah W. Swackhammer, and Joseph M. Cole. Among the seven presidents of Rigdon’s seventy were electioneers Frederick Merryweather, George T. Leach, and James M Greig. However, in less than two years, the movement collapsed owing to Rigdon’s erratic behavior and leadership.[17]

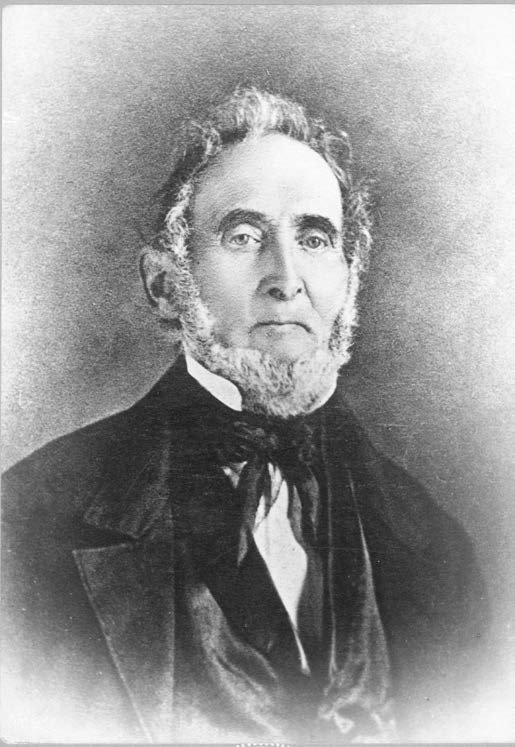

Despite having been Joseph’s

Despite having been Joseph’s

running mate, Sidney Rigdon was

unable to persuade many electioneers to follow him. C. R. Savage photo of earlier engraving courtesy of Church History Library.

In contrast, James J. Strang was the strongest rival to Brigham from 1845 to 1855. In the spring of 1844 Strang visited Joseph in Nauvoo and was baptized by him. Strang then returned to Wisconsin to spread the faith. After Joseph’s murder, Strang produced a letter that he claimed was from the prophet. The correspondence, dated nine days before Joseph’s death, appointed Strang the president of the church and instructed him to gather the Saints to Voree, Wisconsin. Additionally, Strang claimed an angel appeared to him to announce his succession. He soon declared he had translated metal plates from ancient prophets, just as Joseph had. Strang was intelligent, confident, and charismatic, and his claim to succession impressed those that missed the revelatory nature of Joseph’s leadership. He eventually gathered his followers to Beaver Island, Michigan, where he attempted to establish a Zion kingdom.

A small clique of electioneers advocated Strang as Joseph’s successor. Their experience and status promoted them immediately to positions of responsibility among Strang’s following. Although he had been excommunicated in February 1844 by Joseph and Hyrum for publicly teaching plural marriage, Hiram P. Brown nonetheless served faithfully as an electioneer. Even so, in 1846 he became one of Strang’s converts and leaders, and he eventually rose to the rank of apostle.[18] James Greig, one of Rigdon’s seventy, switched allegiances and directed the Strangites in Pittsburgh. Strangite apostle Samuel P. Bacon declared, “With regard to Voree, . . . the saints are in the ‘unity of spirit, in the bond of peace,’ of one heart and one mind in the purposes of God, to work with all their might in the great work of the last days.”[19]

The strongest rival to Brigham Young, James Jesse Strang filled his leadership ranks with disaffected electioneers. Undated

The strongest rival to Brigham Young, James Jesse Strang filled his leadership ranks with disaffected electioneers. Undated

photo by Sainsbury and Johnson

courtesy of Church History Library.

Strang’s missionary force almost rivaled Brigham’s. They canvassed the Midwest and the East and even penetrated Brigham’s strongholds in Nauvoo, Winter Quarters, and England. Not surprisingly, the most effective Strangite missionaries had electioneered for Joseph. Stephen Post joined Strang in 1846 after reading a news article about him. Post labored in Pennsylvania as a missionary before moving his family to Beaver Island. Samuel Shaw, Chicago branch president and son-in-law of campaign leader William W. Phelps, also threw in his lot with Strang. Seizing on this prized convert, Strang ordained Shaw a high priest and sent him to proselyte in Nauvoo. Shaw later served on Voree’s high council and became Strang’s “agent of temporal affairs.” Increase Van Deuzen labored effectively in Illinois, Michigan, and Canada. He and his wife published a pamphlet exposing the endowment ceremony they had participated in at Nauvoo. Zenos H. Gurley labored extensively in Wisconsin and Illinois, baptizing fifty-two converts in two months alone. He also created the branch at Yellowstone, Wisconsin, that would eventually become the nucleus of the Reorganized Church. David Rogers, after delivering the 1844 Latter-day Saint vote in New York to the Democrats, became Strang’s leader in New York City.[20]

Strang brazenly sent former electioneers to Nauvoo, where they had some success in gaining adherents. Hiram S. Stratton’s quorum president Jehiel Savage excommunicated him for Strangite apostasy. Ironically, three weeks later the quorum had to excommunicate Savage for following Stratton. Savage later became a Strangite apostle. To settle the matter, Brigham invited Moses Smith to present “Strangism” in the temple. Smith was a relative of Strang, a Strangite apostle, and the leader of the Strangite missionaries in Nauvoo. Joined by former electioneers Hiram S. Stratton, William Savage, and Samuel Shaw, Smith declared “the doctrine and claims of James J. Strang” to those assembled. Brigham then arose and said, “I but simply ask the people if they had heard the voice of the Good Shepherd in what had been advanced.” After a resounding “No!” church leaders publicly excommunicated the Strangite missionaries and Strang himself (his second dismissal). However, the Strangite missionaries did not leave Nauvoo empty-handed; they gathered around one hundred converts.[21]

The Strangite missionaries sent to Winter Quarters also had some success. In 1847 Uriel Nickerson received news that his father and fellow electioneer, Freeman Nickerson, had died at Winter Quarters. Uriel arrived to retrieve his widowed and destitute mother. He testified to all who would listen that he knew Strang was the “Lord’s anointed” and that their afflictions were God’s curse for following Brigham. He implored everyone to leave with him for Voree. Only a handful followed him. Nickerson preached the same message at encampments throughout Iowa, gaining a few more converts. Ironically, Nickerson’s mother eventually split with him and chose to go to Utah. The decision to send Strangite missionaries in force to Winter Quarters began after Brigham and the apostles reached Salt Lake City. The effort was led by former electioneer John W. Grierson, who had abandoned Brigham at Winter Quarters. From 1847 to 1851, Strangite emissaries claimed more than one hundred converts from the area.[22]

Strangite missionaries, from the beginning, battled with rival former electioneers loyal to Brigham. Strang first publicly declared his revelation at a conference in Michigan on 5 August 1844—just days before the confrontation between Brigham and Rigdon. Strang’s strategy was to proselyte at church conferences in the Midwest, away from the apostles. However, the Michigan conference did not go as Strang had hoped. Led by Crandell Dunn, Norton Jacob, Harvey Green, Moses Smith, and several other electioneers, the conference denied Strang’s claim, saying the letter “carried upon its face the marks of a base forgery . . . and [was] dishonorable to the name of Joseph Smith, whose signature it bore in a hand he never wrote.” They directed Strang not to talk of the letter and to go to the Twelve for verification. Strang and his associate Aaron Smith “absolutely refused, and so they passed on East seeking proselytes.”[23] The conference excommunicated them and assigned electioneers Norton Jacob and Moses Smith (the latter a relative of both Aaron Smith and Strang) to take a copy of Strang’s letter to Nauvoo.[24] The apostles likewise denounced Strang’s letter and warned Moses Smith to follow the Twelve on the matter. Paying no heed, he soon left Nauvoo, taking up with electioneer colleague James Emmett and later with his brother Aaron and nephew-in-law Strang.[25]

Similar confrontations occurred in the eastern United States and overseas in England as well. As president of the Eastern States Mission, William I. Appleby almost single-handedly battled a growing Strangite influence in the area. He warned and then had to excommunicate local leaders David Rogers and David S. Hollister (both electioneers), along with fifty others. When Strang sent three of his best missionaries to England—electioneers Lester Brooks and Moses Smith and Book of Mormon witness Martin Harris—they met with stiff resistance from their electioneer colleagues on missions for Brigham. Cyrus H. Wheelock recorded their public debate, which he and his companions won so decisively that Martin Harris switched sides by the end. Unable to gain a Strangite foothold in England, Brooks and Smith returned to the United States defeated.[26]

Embarrassment in England was only the beginning of Strang’s unraveling. Electioneer Samuel P. Bacon, president of the Strangite apostles, stumbled upon “fragments of those plates which Strang made the Book of the Law from.” Having exposed Strang’s fraud, Bacon secretly fled Beaver Island with his family. When William Savage and others discovered financial mismanagement by Strang, they too vanished with their families. Acting in his role of sheriff, George Miller attempted to return Savage and the others to “jury duty,” leading to a shootout on Lake Michigan between former electioneers. The escapees so savagely shot up Sheriff Miller, his men, and his boat that they had to be rescued while Savage and the others escaped.[27]

Former electioneers George Miller and Lucien Foster moved Strang organizationally and doctrinally toward the church as it was in Nauvoo, especially its political arrangements and the practice of plural marriage. They shared confidential information about the activities of the Council of Fifty, including Joseph’s coronation. Thus Strang was elected to the Michigan State House, created his own kingdom on Beaver Island, and was publicly crowned king. Moreover, he secretly entered plural marriage with Elvira Field, the nineteen-year-old daughter of Reuben Field, an electioneer in Ohio who converted to Strangism. Elvira clandestinely accompanied Strang on a tour of the eastern states. At a conference in New York, electioneer Increase Van Deuzen and Lorenzo D. Hickey accused Strang of polygamy, claiming to have incriminating letters. Shoving Strang in the chest, Van Deuzen yelled, “You are guilty! You are guilty!” Consequently, the conference disfellowshipped Hickey and excommunicated Van Deuzen. Throughout the proceedings, Elvira, disguised as cousin “Charley Douglass,” silently watched.[28]

Strang’s decision to embrace Nauvoo politics and plural marriage alienated most of his followers, including some electioneers. Stephen Post confided to his brother, “I have not as strong confidence in Br. Strang as I had in his predecessor Joseph.” Post left the Strangites to become the successor to Sidney Rigdon’s faltering movement. Support for Strang ebbed until disgruntled followers shot and killed him in 1856. His church all but disappeared. Loyal to the end, George Miller stayed by Strang’s bedside until he passed. Now an orphan of three different Latter-day Saint movements, Miller—the former Nauvoo bishop, electioneer, and Council of Fifty member—somberly chose to go to California. He died before arriving.[29]

A few others claimed leadership of the church. William Smith, Joseph’s younger brother, quickly became disaffected from his fellow apostles, joined the Strangites, and formed a short-lived sect. His small band of followers included electioneers Joseph Younger, Selah Lane, and Omar Olney. Before the prophet Joseph died, Lyman Wight and fellow Council of Fifty member George Miller had permission from the council to establish a colony in Texas. Wight, refusing to follow Brigham, left for Texas and settled there. Miller initially accepted Brigham’s leadership, but after the two had a confrontation, Miller followed Wight to Texas. Electioneers Jeremiah Curtis, Samuel Heath, Lorenzo Moore, and Ira T. Miles also followed Wight, who ineptly led his small colony until his death in 1858. Other brief contenders for Joseph’s legacy included electioneers James Emmett and Charles B. Thompson, both of whom tried unsuccessfully to create Zion communities in Iowa. Notably, the key leaders in each schismatic group were former electioneers.

George Miller electioneered in

George Miller electioneered in

Kentucky and, after Joseph’s death, followed Brigham Young, then Lyman Wight, and finally James J. Strang until Strang’s death. Portrait by unknown artist. © IRI.

A slight majority of the electioneer cadre who did not follow Brigham and the apostles after Joseph’s death chose to have nothing to do with any of the splinter groups. Darwin J. Chase apostatized while on the church’s official gold mission in California in 1849. He joined the US Army and was killed by American Indians at the Bear River Massacre in 1863. Ironically, the army buried him in Farmington, Utah, among his former friends.[30] Shaken by the death of his wife while he was away electioneering, Sylvester B. Stoddard left Nauvoo and briefly flirted with the Rigdonites. After returning to Kirtland, Ohio, he and several others armed themselves and took possession of the former temple and church farm.[31] Excommunicated for preaching false doctrine in Cincinnati following the campaign, Henry Elliot never returned to the church. Despite being a high priest and working on the Nauvoo Temple, Stephen Litz ultimately moved to Missouri, severing his affiliation with the church. After his electioneering mission, Peter Van Every stayed in Michigan, becoming an important figure in financial and political circles there. As rumors of plural marriage grew in Nauvoo, Joseph J. Woodbury and his brother William H. decided to leave the church. Joseph returned to his native Massachusetts and lived out his life as a Methodist preacher while William moved to southern Illinois and became a wealthy businessman and physician.[32]

Exodus

Nauvoo Temple Endowment

The electioneer veterans following Brigham made completion of the Nauvoo Temple their highest priority. In 1845 church leaders sent forty-six men throughout the nation for the purpose of “collect[ing] donations and tithings for the temple in the city of Nauvoo.”[33] Thirty-one were drawn from the body of electioneers, a staggering 67 percent considering they constituted just 15 percent of available priesthood holders at the time. Brigham and other leaders knew they could trust these men, committed as they were to “Joseph’s measures” and having recently been working among the Latter-day Saint congregations around the nation.

Between 11 December 1845 and 6 February 1846, more than five thousand Saints received their temple endowments in Nauvoo. Working day and night, church leaders and their associates diligently performed as many proxy ordinances as possible before the spring exodus. Brigham relied on many electioneers to assist in this mammoth project. Not counting apostles, half of the men who dispensed the initiatory rites of washing and anointing were electioneers; and 79 percent of those who performed the endowment ceremony came from that same group. Given the electioneers’ much smaller representation among priesthood members (13 percent of total male endowment participants), such numbers once again demonstrate the immense trust the electioneers had earned.

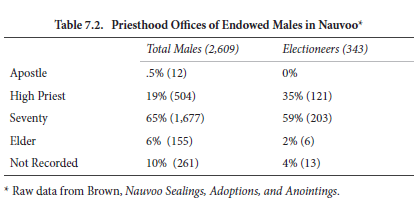

This strong representation in the church’s most sacred ordinances foreshadowed the electioneers’ rise in the aristarchy of the future Great Basin kingdom. Of the 509 electioneers who were loyal to Brigham, 343 received their endowments and held higher priesthood office than that of their peers In fact, the percentage of electioneers who were high priests almost doubled that of the endowed priesthood population in Nauvoo (see table 7.2). Moreover, most of the electioneers had received a higher priesthood office than that of their peers in preparation for, during, or (especially) after their electioneering service. Their decision to serve in Joseph’s campaign demonstrated their strong faith and brought them into the orbit of the apostles. Generally, an appointment to a higher priesthood office followed.

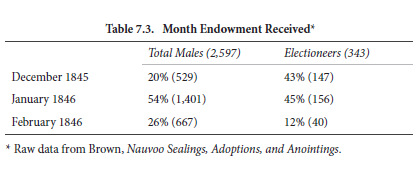

Another way to measure the influence of the electioneers is to note in which month they received their endowments. When they began performing temple ordinances in December 1844, church leaders recommended those whom they considered worthy and otherwise ready to receive the ordinance. Since the ceremony lasted more than three hours and thousands of eligible Saints wished to participate, the process needed to be efficient as well as orderly. Consequently, priority was given to trusted associates, many of whom either were leaders or would likely soon become such. In fact, many early recipients of the endowment in turn assisted in presenting the ordinance to others and performing related duties, thereby lightening the workload for church leaders and expediting the around-the-clock work. In this way the order in which the Saints received their endowments indicates something of their status in the church at that time (see table 7.3). Significantly, during December only 20 percent of males received the endowment, and yet 43 percent of electioneers did. Certainly church leaders did not elevate these men solely because of their electioneering service. However, the numbers demonstrate that their labor and loyalty in the shared experiences of the campaign with the Twelve made them more likely to be chosen. They had become visible, or more visible, as steadfast allies.

Marriage Sealings, Plural Marriage, and Second Anointings

Brigham and the Twelve also exercised their sealing keys, uniting couples eternally. They sealed 740 couples in the Nauvoo Temple period (December 1845 to early February 1846), and 175 of the husbands were former electioneers—again a number larger than their statistical footprint. Plural marriages among the same group would increase dramatically as well. By 1850, 103 electioneers (almost a quarter of the surviving total) had married additional wives. Because plural marriage required the invitation of church authorities, the electioneers’ disproportionate participation in that practice is also indicative of their increasing influence.

Electioneers received and assisted others in receiving sacred ordinances in the Nauvoo Temple before the Saints’ exodus west. Daguerreotype of the Nauvoo

Electioneers received and assisted others in receiving sacred ordinances in the Nauvoo Temple before the Saints’ exodus west. Daguerreotype of the Nauvoo

Temple courtesy of Harold B. Lee Library Digital Collections, BYU.

Second anointings were another such indicator of the electioneers’ faithfulness. Reserved for a select few, this ordinance, in addition to its religious significance, confirmed one as a “king and priest” capable of ruling in the kingdom of God. Only 6.6 percent of endowed males during the temple period received this honor, yet 19 percent of endowed electioneers did—a percentage nearly threefold that of the first group. In fact, 38 percent of all second anointings were given to electioneers despite the fact that the group represented only 13 percent of endowed males.

The long-awaited temple ordinances prepared the electioneers spiritually for the hardships before them. Franklin D. Richards recorded, “For the privilege of assisting in this part of the endowment, I know not how to be so thankful as I desire, and I pray that the knowledge which I have here obtained of the laws of the kingdom of God may prove an eternal blessing unto me and redound to my salvation.”[34] Norton Jacob wrote, “It was the most interesting scene of all my life and one that afforded the most peace and joy that [1] had ever experienced.”[35] The high level of participation in giving and receiving the temple ordinances marked the electioneers as trusted, loyal, and dedicated—true believers in Zion’s earthly mission. Church leadership now turned to them to help evacuate the Saints from the United States and build Zion in the West.[36]

Expulsion

“To carry out Joseph’s measures is sweeter to me than . . . honey,” Brigham declared on 1 March 1845 when he reconvened the Council of Fifty—a covert body of priesthood leaders tasked with establishing the government of the kingdom of God.” He announced that Joseph had “laid out work for this church which would last them twenty years.”[37] They needed to get busy. The council sustained Brigham as the standing chairman. Later, like Joseph, they ordained him king, priest, and ruler over Israel on earth. Brigham dropped unfaithful council members and admitted new ones. Of the twenty-eight men who joined the Council of Fifty between 1845 and 1850, half were former electioneers.[38] The “living constitution”[39] met regularly “to find a place where [they could] dwell in peace and lift up the standard of liberty.” Brigham further instructed that it was time to turn from the “gentiles” and begin “uniting the Lamanites [American Indians] and sowing the seeds of the gospel among them.”[40] While the consolidation of the tribes ultimately did not occur, the Saints certainly turned from the gentiles.

The decision to continue Joseph’s Zion ideals led to renewed friction with Nauvoo’s neighbors. Electioneer Henry Bigler remembered, “It appeared that because ‘Mormonism’ did not die out with the death of the prophet and patriarch as was anticipated and seeing too that our people were one in political matters all voting one way that hatred grew in the breasts of people against us to such a pitch that every kind of falsehood that was calculated to prejudice the mind of the public was resorted to.”[41] William W. Phelps added that “the greatest fears manifested by our enemies is the union of church and state.”[42] Mobs burned outlying settlements while the Illinois legislature rescinded Nauvoo’s charter and legion. The writing was on the wall; the Saints faced violent expulsion again. Responses by those in the Council of Fifty were furious, apocalyptic, and vindictive. Phelps insinuated that the legislators of the nation had conspired to “destroy the prophets.” It was time to leave and be among and convert the American Indians, who in time would be the instruments of God as they “come out of their hiding places and go forth to waste and destroy with fire, pestilence, &c.”[43]

The Council of Fifty believed they were justified in declaring independence from the United States. While such talk could be construed as treason, council members were adamant that God had established them as a sovereign kingdom. The nation had repeatedly rejected them, ultimately assassinating Joseph while he was a presidential candidate. “What is the patriotism of these United States?” Phelps questioned since no redress had been made for the Saints’ expulsion and loss of life and property in Missouri and Illinois.[44] With confidence Phelps declared that the council was “the center of gravity” with “plans which will ultimately free the world. . . . We are the hammer of the whole earth, and we will break it in pieces.”[45] Brigham agreed. On 11 March 1845, the one-year anniversary of the Council of Fifty, members decided to send a letter to each governor of the Union in a final attempt at reconciliation. “This is the last call we will make to them, and if they don’t listen to it we will sweep them out of existence,” Brigham announced. “Let the damned scoundrels be killed, let them be swept off from the earth, and then we can go and be baptized for them, easier than we can convert them. . . . The gentiles have rejected the gospel; they have killed the prophets.”[46] While such violent hyperbole is shocking to modern ears, it accurately describes how most Saints felt in the wake of Joseph’s assassination.

Using maps acquired in Washington, DC, during the campaign, the Council of Fifty planned to settle in the Great Basin. The first refugees crossed the frozen Mississippi in early February 1846. Electioneers suffered alongside fellow Saints. Benjamin Brown sold his house and six-thousand-tree nursery, valued at $3,000, for only $250. Others, like Jonathan Browning, locked their homes and shops and simply left. Joseph Holbrook penned: “The city of Nauvoo now presented a scene of desolation. . . . Every man [made] every effort in his power to leave his home, and a great many of the Saints were obliged to go without realizing one cent for their dwellings. Thus the hand of persecution had prevailed.”[47]

Henry Bigler later recorded, “To tell the truth, I knew not where we were going, neither did I care much, only that it might be where I and my people could have the liberty to worship Almighty God according to the dictates of our own conscience without being mobbed for it.”[48] Throughout 1846 the Saints lay scattered across Iowa Territory, struggling through adverse weather and near-impossible road conditions and hunted by disease and hunger. The camp’s slow pace forced a decision to winter along the east and west banks of the Missouri River—Council Bluffs and Winter Quarters, respectively. The Saints built towns of log cabins surrounded by hundreds of wagons—what Young named “the Camp of Israel.”

Death stalked the electioneers even before they headed into the wilderness. From the presidential campaign until the end of 1850, fifty-eight of that group died. The first, Jesse Berry, perished on 6 August 1844 in Nauvoo, just after returning from electioneering. Peter Melling died in September while still on his mission in Indiana. Cholera claimed John Jones Sr. and John Jones Jr. in the same month. Amos Hodges was murdered in 1845 in Nauvoo, and Amos Condit was murdered two years later in Winter Quarters. Dozens of electioneers perished in Iowa and Nebraska from 1846 to 1850. Samuel Bent worked himself to death as he suffered from malnutrition and disease while presiding as at Garden Grove, a way station in Iowa. Perhaps the saddest tale was the death of Clark Hallet, his wife, and all their children, all from exposure-related sickness, at Mount Pisgah, another temporary community. Four electioneers died in the Great Basin: William Coray, John Tanner, Joseph Stratton, and George W. Langley.[49] Langley was the first person buried in the Salt Lake cemetery.

Winter Quarters

In and around Winter Quarters, electioneers helped build a temporary Zion in the wilderness. Church leadership created a “municipal high council” to “preside in all matters spiritual and temporal.” This council, containing electioneers Andrew H. Perkins, Johnathan H. Hale, and Daniel Spencer, reflected the Zion ideal. Religiously and politically, the council was to “oversee and guard the conduct of the Saints and counsel them, that the laws of God and good order are not infringed upon.” Economically, they were to “use all means in [their] power to have all the poor Saints brought from Nauvoo” and “assist and counsel the bishops, who [were] appointed to take charge” of the Mormon Battalion families.[50] Electioneers filled other important leadership positions as well. Fifteen were bishops, and Samuel Bent (mentioned above) and Lorenzo Snow (who presided at Mount Pisgah) were presiding authorities. William Cutler was chief scout and given charge of the camp’s cattle. The council commissioned Howard Egan and Nathan Tanner to trade and buy corn. Levi Stewart supervised mail within Iowa.[51]

The Mormon Battalion

In May 1846 Mexico and the United States went to war. Colonel James Allen of the US Army carried orders from President James K. Polk to enlist a battalion of five hundred “Mormons.” As Allen moved west to Winter Quarters, he met resentment and resistance at each encampment. For these refugees the request was particularly galling coming around Independence Day. Electioneer Henry Bigler recalled that “[Senator Thomas Hart] Benton of Missouri argued at Washington that the Mormons were disloyal and urged that the government make a demand on us, in order to prove our loyalty, and if we failed to comply there was a plan to call out the military . . . to cut us off and put a stop to our people going into the wilderness.”[52] The Saints were disgusted. Electioneer William Hyde penned: “The government of the United States . . . not being satisfied with . . . driving and plundering thousands of defenseless men, women, and children . . . must now . . . call upon us for five hundred . . . men, the strength of our camp, to go and assist them in fighting their battles. When this news came I looked upon my family and then upon my aged parents and upon the situation of the camps in the midst of an uncultivated, wild Indian country and my soul revolted.”[53]

What Hyde and most Saints did not know was that Brigham had sent electioneer Jesse C. Little to Washington, DC, to ask for just such an opportunity. He hoped it would raise the cash needed for the exodus. Little collaborated with Latter-day Saint sympathizer Thomas L. Kane to negotiate with President Polk, who agreed to enlist five hundred “Mormons . . . with a view to conciliate them, attach them to our country, and prevent them from taking part against us.”[54] Kane and Little hurriedly traveled west to inform church leaders of the deal, and Brigham and others went camp to camp encouraging men to enlist.

Some electioneers accepted Brigham’s appeal to enlist despite the hardships it created. William Hyde, whose soul days before “revolted” at the government’s request, reversed course and displayed the intense loyalty to the church that often characterized the electioneers. “When our beloved president came to call upon the Saints to know who among all the people were ready to be offered for the cause, I said, ‘Here am I, take me.’” Hyde recalled, “The thoughts of leaving my family at this critical time are indescribable.” The Saints remaining at Winter Quarters would be “far from . . . civilization with no dwelling save a wagon with the scorching midsummer sun to beat upon them, with the prospect of the cold December blasts finding them in the same place.”[55] Given the electioneers’ proven loyalty and steadfastness, it is surprising that of the 540 battalion members, only forty-one, or 7 percent, were drawn from the cadre of electioneers, less than half of their statistical representation in the Camp of Israel. This is the only post-campaign circumstance of these veterans being utilized less than their peers.

Why so few? Perhaps it was intentional on the part of church leaders. For example, when Jonathan Browning tried to enlist, Brigham hurriedly pulled him away to say, “Brother Jonathan, we need you here.”[56] Brigham and other church leaders may have desired the same for many of the electioneers so they could support the suffering Saints and plan for the spring migration to the Great Basin. Furthermore, many of them were already serving in leadership roles that may have been critical to maintain. Regardless, the recruits needed shepherds, and under the muster agreement Brigham had the authority to choose the officers. Out of seventy-five such officers, sixteen were electioneers, some of whom served at the invitation of church leadership. For example, on 6 July 1846 Brigham made James Pace one of only five first lieutenants alongside electioneer colleagues Elam Luddington and George P. Dykes.[57] Another example is David Pettegrew, who later recalled, “[1] received word from President Young wishing me to join the battalion.” Pettegrew informed Young that his son, James Phineas, had enlisted and that it was “impossible for both of us to go.” Young responded, “If you both can’t go, I wish you to go by all means, as a kind of helmsman.” Pettegrew immediately enlisted.[58] Thus while constituting only 7 percent of the battalion, electioneers represented 21 percent of the leadership.[59]

After the battalion was formed, Lt. Colonel James Allen died. Electioneer Jefferson Hunt became acting commander until new leadership arrived. Hunt and electioneer comrades Daniel Tyler and Levi W. Hancock preached daily to the men the need for faith and solidarity in their journey to southern California, where they arrived in January 1847. The nineteen-hundred-mile march, the longest in United States military history, tested the resolve of the men and was key to acquiring the territory that became Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, and California. It was also a time for introspection. While on guard duty one evening, young electioneer Henry G. Boyle heard wolves and watched a grizzly bear walk past the camp. He recorded that his “mind wandered back over the years gone by and . . . the strange events that had brought [him] to the present time and place.” He had given up his life and family in Virginia for the gospel and was now serving the government that had exiled him. Yet, he noted, “I love the people I am associated with and the principles of the gospel better than all else.”[60]

California Gold

Upon discharge, several members of the Mormon Battalion found work at Sutter’s Fort and discovered gold in the American River. Electioneer Henry Bigler made this historic entry in his diary: “This day some kind of metal was found in the tail race that looks like gold.” Within a week Bigler and electioneer companions Samuel Rogers and Guy Keyser harvested “more than a hundred dollars” of gold.[61] They eventually brought $17,000 in bullion to Salt Lake City. As word spread throughout the nation and world, Brigham sent several electioneers on church-sanctioned “gold missions” to procure gold and receive tithing receipts from the California Saints. Electioneer comrades Howard Egan and Jefferson Hunt made careers of guiding gold-seeking “forty-niners” and others to California.

In general, however, church leaders strongly counseled against prospecting. Yet, as electioneer Joseph Holbrook wrote, “Many of our brethren left the valley to dig gold, contrary to the counsel of the servants of God.”[62] At least four electioneers departed for California: Joseph Mount, George W. Hickerson, Seabert Shelton, and George G. Snyder. Mount divorced his wife, a decision he lamented the rest of his life, when she and their children would not go with him to California. Hickerson also left for California in search of fortune. He later returned to his family barely alive and penniless from a debilitating illness. Shelton and Snyder became wealthy by operating hotels for prospectors. Shelton remained in California, never rejoining the church. Snyder returned after four years and became a noted economic, religious, and political leader.[63]

Pioneer Companies

At Winter Quarters Brigham and the Council of Fifty selected those who would lead emigration parties in 1847. Brigham himself led the vanguard company of 143 that contained twenty-two electioneers. Some felt a sense of excitement and long-denied freedom. On 4 July Norton Jacob recorded, “This is Uncle Sam’s day of Independence. Well, we are independent of all the powers of the gentiles, and that’s enough for us.”[64] On 21 July electioneers Erastus Snow and Orson Pratt became the first Latter-day Saints to enter the Great Salt Lake Valley. Snow recorded, “When we arrived . . . near the mouth of Emigration Canyon, which gave us the first glimpse of the blue waters of the Great Salt Lake, we simultaneously swung our hats and shouted ‘Hosanna,’ for the Spirit witnessed that here the Saints should find rest.”[65] Howard Egan noted, “My heart felt truly glad, and I rejoiced at having the privilege of beholding this extensive and beautiful valley that may yet become a home for the Saints.”[66] Impressively, electioneers captained six of the seven additional companies of 1847. Between then and 1850, forty-six wagon companies journeyed to the Salt Lake Valley, and electioneers led twenty-four of them, or 52 percent. During the years that followed, electioneers continued to be integral to the gathering of the Saints to the Great Basin. Ezra T. Benson alone captained six companies over a decade.[67]

More than two hundred Saints bound for California set sail from New York City aboard the clipper Brooklyn on 4 February 1846—the very day that the exodus from Nauvoo began. The company was led by electioneer Samuel Brannan. Electioneers John M. Horner, Elijah W. Pell, and Quartus S. Sparks joined him. These voyaging emigrants were following apostolic counsel to the Saints living outside Nauvoo: “We do not want one Saint to be left in the United States. . . . Let every branch . . . flee out of ‘Babylon,’ either by land or sea.”[68] The Brooklyn reached San Francisco on 31 July 1846, just days after a US armada subdued the small Mexican contingent there. Ironically, the Brooklyn Saints found the very nation they were escaping stationed at their destination. However, under Brannan’s direction, the group quickly purchased land and began farming. Brannan brought the printing press that he had used to print The Prophet in New York during the presidential campaign. He printed the first newspaper in California—the California Star, which would launch the gold rush.

* * *

Following Joseph’s martyrdom, the church hierarchy continued to call on a high percentage of electioneers for responsible service not only because they had faithfully campaigned for Joseph at great personal sacrifice, but also because of what that service had decisively made them to be. To be sure, they certainly showed loyalty and faith before the campaign, but these qualities and related ones appear to have deepened and matured during their electioneering service as a result of their unstinting labors on behalf of their prophet. They emerged from their missions as men of tested ability and character. Most had the fortitude to endure the disappointment and confusion surrounding the prophet’s death and the succession crisis. That they would bear leadership roles following the campaign suggests that church leaders knew these men had developed the requisite qualities to succeed in those roles and would be prepared to assume future theodemocratic roles as well. Their loyalty and faith stood them in good stead. In fact, it is apparent that no other pre-campaign variables could predict the high number of electioneers in postmartyrdom leadership. Not income, previous church position, age, occupation, family connection, priesthood office, or missionary service were predictors of those who would help lead Zion that autumn and forward.

The electioneers had been no different from their Latter-day Saint peers except for a loyalty and faith that prompted them to storm the nation in advocacy of Joseph’s election. This mission was a watershed moment: it enabled them to internalize the campaign’s theodemocratic themes, to develop familiarity with the Twelve and earn their trust, and to weather the trauma of Joseph’s death. For one to be a leader in the Great Basin theodemocracy, loyalty to Joseph and a commitment to carry out his measures had to transfer to loyalty to Brigham, the Twelve, and the Council of Fifty. In this the electioneers had a distinct advantage over their fellow Saints who had not served in trusted, challenging, and prolonged capacities. Although not all of the electioneer cadre followed Brigham west or received leadership positions, many did so, creating a corps of valiant men on whom church leaders could rely.

In the challenging geography of the Great Basin, Brigham began rebuilding Joseph’s Zion. “This is a good place to make Saints,” he once observed.[69] Having endured the devastation of Joseph’s death, the tumult of the succession crisis, the humiliation of expulsion, and the harsh exodus to the valley of the Great Salt Lake, those who followed Brigham now confronted the privations of a new wilderness home a thousand miles from civilization. The faith and fortitude to come this far emanated from tested testimonies, none more so than those of the electioneers. They were now poised to form the core of the initial aristarchy of the kingdom of God.

Notes

[1] JSH, D-1:1362. The entry for 6 August 1842 was written in July 1845, when the historians entered it into the record. The quotation above was penciled in sometime after that and attributed to a memory of Anson Call. Several other sources from 1840 and 1842 clearly show that Joseph was not just talking about the Rocky Mountains but was making plans to settle there and assigning missions. See Esplin, “‘Place Prepared,’” 75–78.

[2] Smoot, Day Book, 28 July 1844, 56–59.

[3] Hatch, Autobiography, 2–7.

[4] Erastus Snow, Autobiography, 9.

[5] William Hyde, Journal, 59.

[6] Hatch, Autobiography, 8. Uncle Jeremiah Hatch is not to be confused with the Jeremiah that is his nephew and the older brother of Lorenzo Hatch. Nephew Jeremiah was assigned to Vermont but for unknown reasons electioneered in Michigan. After Joseph’s death, Uncle Jeremiah followed Sidney Rigdon and married his daughter Lucy.

[7] “Conference Minutes,” Times and Seasons, 1 November 1844, 694.

[8] William Hyde, Journal, 66.

[9] Quoted in Little, Jacob Hamblin, 21.

[10] Nathan Porter, Reminiscences, 132.

[11] Duke Family Organization, Journal of Jonathan Oldham Duke, addendum 5, 53.

[12] “An Epistle of the Twelve,” Times and Seasons, 15 August 1844, 618–19.

[13] Council of Fifty, Minutes, 1 March 1845, in JSP, CFM:2.

[14] See “Conference Minutes,” Times and Seasons, 1 November 1844, 696.

[15] Church leaders ordained 203 of Joseph’s electioneers to be seventies.

[16] Of this group, Emmett and Thompson were former electioneers.

[17] See Van Wagoner, Sidney Rigdon, 270–75.

[18] Black, “Hiram Brown,” Latter-day Saint Vital Records II Database (hereafter “LDSVR”). See Robin Scott Jensen, “Strangite Missionary Work, 1846–1850,” 78.

[19] Voree Gospel Herald, 29 November 1849, as quoted in Speek, James Strang and the Midwest Mormons, 95.

[20] See Post, Journal, 19 June 1846; Samuel Shaw to Brigham Young, 1 October 1844; Speek, James Strang and the Midwest Mormons, 82; Black, “Zenos Hurley,” LDSVR (database); Woodruff, Wilford Woodruff, Fourth President of the Church, 3:151–52; Voree Gospel Herald, 29 November 1849, as quoted in Speek, James Strang and the Midwest Mormons, 148; and David Rogers to Brigham Young, 17 August 1844. Rogers’s convincing of local Saints to vote Democratic rather than sit out the election may have helped James K. Polk in his razor-thin upset of Henry Clay in New York and, thus, in the general election.

[21] Samuel Hollister Rogers, Journal of Samuel H. Rogers, MS 883, FD 1, CHL, 67.

[22] See Zion’s Reveille, 25 February 1847, which mentions the death of Nickerson’s father and his mother’s destitute condition; Gospel Herald, 29 November 1849, 197; Fitzpatrick, King Strang Story, 191; and Strang, “Brethren and Sisters,” Chronicles of Voree, 14 August 1846, 102.

[23] Jacob, Reminiscence and Journal, 8.

[24] See Dunn, “History and Travels,” 1:53–54.

[25] See Jacob, Reminiscence and Journal, 14.

[26] See Appleby, Autobiography and Journal, 165–66; and Wheelock, Journal, 25 October 1846.

[27] Speek, James Strang and the Midwest Mormons, 175–77.

[28] Launius and Thatcher, Dissenters in Mormon History, 184; and Speek, James Strang and the Midwest Mormons, 54, 56, 63–85, 150, 175–77.

[29] Speek, James Strang and the Midwest Mormons, 68, 73–75, 171, 222–25.

[30] See “The Fight with the Indians,” Deseret News, 4 February 1863, 253; and Black, “Darwin J. Chase,” LDSVR (database).

[31] See Black, “Josiah Butterfield,” LDSVR (database); Black, “Amos Davis,” LDSVR (database); and Anderson and Bergera, Joseph Smith's Quorum of the Anointed, 158.

[32] The Woodburys appear in censuses but not on membership rolls of any Latter-day Saint sect. For more on Elliot, see Times and Seasons, 15 August 1844, 623. On Van Every, see Bingham, Early History of Michigan, 654. On plural marriage, see Woodbury, History of the Jeremiah Woodbury Family, 11.

[33] Times and Seasons, 15 January 1845, 780.

[34] Franklin D. Richards, Diary, as quoted in Anderson and Bergera, Nauvoo Endowment Companies, 412.

[35] Jacob, Reminiscence and Journal, 24.

[36] The foregoing information on ordinations is from Brown, Nauvoo Sealings, Adoptions, and Anointings.

[37] JSP, CFM:382–83 (1 March 1845).

[38] See Quinn, “Council of Fifty,” 193–97; Ezra T. Benson, Horace S. Eldredge, Lucien R. Foster, David Fullmer, John S. Fullmer, Joseph L. Heywood, John Pack, Franklin D. Richards, Lorenzo Snow, Willard Snow, Daniel Spencer, Joseph Young, and Phineas Young.

[39] Lyman, Journal, 18 February 1845, 12.

[40] JSP, CFM:377 (1 March 1845).

[41] Bigler, Diary of a Mormon in California, 4–5.

[42] JSP, CFM:285 (4 March 1845).

[43] JSP, CFM:286 (4 March 1845).

[44] JSP, CFM:288 (4 March 1845).

[45] JSP, CFM:272, 273 (1 March 1845).

[46] JSP, CFM:300 (11 March 1845).

[47] Holbrook, Life of Joseph Holbrook, 76.

[48] Bigler, Diary of a Mormon in California, 5.

[49] William Coray died at age twenty-six from tuberculosis that he acquired in California as part of the Mormon Battalion. John Tanner died of natural causes at age seventy-two. Joseph Stratton died from exposure-related illness at only twenty-nine years of age while scouting faster routes through the mountains for emigration to Salt Lake Valley. George W. Langley died at age thirty-one from exposure-related illness while on guard duty in Salt Lake Valley.

[50] Journal History of the Church, 21 July 1846.

[51] The bishops were Jonathan H. Hale, Ellis M. Sanders, Levi W. Hancock, Edson Whipple, Jacob Myers, William G. Perkins, Andrew H. Perkins, Thomas Guyman, John Tanner, Daniel Spencer, Jonathan C. Wright, Abraham O. Smoot, Isaac Houston, Jesse C. Little, and John Vance. See Clayton, Journal, 120.

[52] Gudde, Bigler’s Chronicle of the West, 17.

[53] William Hyde, Journal, 73.

[54] Polk, Diary of a President, 109.

[55] William Hyde, Journal, 73–74.

[56] Browning and Gentry, John M. Browning, American Gunmaker, 4–5.

[57] See Pace, “Biographical Sketch,” 5.

[58] Pettegrew, “History of David Pettegrew,” 185–232.

[59] Electioneer officers were Jefferson Hunt, James H. Glines, Elam Luddington, William Coray (who also brought his newlywed wife), William Hyde, David P. Rainey, Thomas Dunn, John D. Chase (and his wife), Daniel Tyler, Richard D. Sprague, George P. Dykes, Nathaniel V. Jones, James Pace, Samuel Gully, and Levi W. Hancock.

[60] Boyle, Reminiscences and Diaries, 26–28. See William Coray, Journal, 7.

[61] Bigler, Diary of a Mormon in California, 30 January 1848.

[62] Holbrook, Life of Joseph Holbrook, 128.

[63] Official cadre “gold missionaries” included Howard Egan, Jefferson Hunt, Bradford W. Elliott, Darwin J. Chase, Peter M. Fife, Charles C. Rich, and Amasa Lyman. See Hickerson, “Autobiographical Sketch,” p. 5; and Gregory, History of Sonoma County, California, 794.

[64] Jacob, Reminiscence and Journal, 4 July 1847.

[65] Erastus Snow, Autobiography, 11–12.

[66] Egan, Pioneering the West, 103.

[67] Electioneer company leaders in 1847 were Edward Hunter, Abraham O. Smoot, Daniel Spencer, Jedediah M. Grant, Charles C. Rich, Levi W. Hancock, Jefferson Hunt, James Pace, and Samuel Gully. Gullly died while leading his company.

[68] Quoted in Roberts, Comprehensive History of the Church, 3:25.

[69] Deseret News [Weekly], 10 September 1856, 213.