A Campaign to “Revolutionize the World”

Derek R. Sainsbury, “A Campaign to 'Revolutionize the World,'” in Storming the Nation: The Unknown Contributions of Joseph Smith’s Political Missionaries (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 87‒112.

We mean to elect him, and nothing shall be wanting on our part to accomplish it; and why? Because we are . . . fully satisfied that this is the best or only method of saving our free institutions from a total overthrow.

—Willard Richards to James A. Bennet, 20 June 1844[1]

In June of 1842 New York Herald subscribers read a shocking statement. “The Mormon Empire” was rising on the nation’s frontier under “Joe Smith,” the “modern Mahomet.” “It is very evident,” the paper’s correspondent declared, “that the Mormons exhibit a remarkable degree of tact, skill, shrewdness, energy, and enthusiasm.” Their strength was their unity: “In all matters of public concernment, they act as one man, with one soul, one mind, and one purpose.” Such was evident in Illinois, where the reporter noted, “They [the Latter-day Saints] have already shown how to acquire power and influence by holding the balance of power between both parties. They can already dictate to the State of Illinois, and if they pursue the same policy in other states, will they not soon dictate to Congress and decide the presidency?”[2] The statements echoed one from the Herald’s owner and editor a year earlier—James Gordon Bennett, who wrote he would not be “surprised if Joe Smith were made governor of a new religious territory in the west.” “One day,” Bennett later opined, Joseph could “control the whole valley of the Mississippi, from the peaks of the Alleghenies to the pinnacles of the Rocky Mountains.”[3]

An even more startling declaration appeared in correspondence from an army officer: “The Mormons number in Europe and America about one hundred and fifty thousand, and are constantly pouring into Nauvoo,” which he estimated to contain thirty thousand “warlike fanatics.”[4] Despite there being fewer than ten thousand Latter-day Saints in Nauvoo that year (and certainly fewer than twenty thousand worldwide), it was perception that mattered. Such material was reprinted throughout the country. To most Americans the threat of the growing “Mormon Empire” on their western border was an exotic curiosity, if not a cause for concern. In fact, reports of the movements of Joseph Smith and his followers regularly appeared in newspapers throughout the nation, as did articles reprinted from the Nauvoo papers and from the adversarial Warsaw Signal. Even before he announced his candidacy, Joseph was a national celebrity, albeit a largely unpopular one.

Naturally then, when Joseph announced his campaign in late January of 1844, newspapers across the nation weighed in. Church leaders mailed copies of Views to hundreds of newspapers, many of which reprinted some or all of the pamphlet. Editors opined on Joseph’s platform and chance of success. A few nonpartisan papers gave items of the prophet’s platform high marks and predicted the campaign would have an effect in Illinois and perhaps the nation. However, almost all newspapers of the time were partisan—Democratic or Whig—and their political editors frequently mocked both Joseph and his odds of winning, often comparing him to the unpopular, and now partyless, incumbent John Tyler.

However, continued news out of Nauvoo coupled with the arrival of Latter-day Saint electioneer missionaries throughout the country began to turn heads. In an article in the Daily Missouri Republican that was reprinted around the country, a correspondent wrote:

You have seen it announced that Joseph Smith is a candidate for the presidency of the United States. Many think this is a hoax—not so with Joe and the Mormons. It is the design of these people to have candidates for electors in every state of the Union; a convention is to be held in Baltimore, probably next month. The leaders here are busy in organizing their plans—over a hundred persons leave in a few days for different states, to carry them out as far as possible. I mention these facts only to show that Joe is really in earnest.[5]

As it became clearer that Joseph was serious about seeking the presidency, many papers turned to mocking and deriding him. Almost always these papers tried to connect Joseph and his Views to their political rivals. The two great parties were at parity in national politics and were headed for one of the closest presidential elections in history—and they knew it. Their vitriol for the prophet’s campaign was calculated to siphon off rival voters and to protect themselves from defections. Sometimes Joseph would enter the fray, just as he had done in responding to John Calhoun and Henry Clay. The Nauvoo papers printed his retorts, which often were reprinted around the country. Importantly, newspapers from Maine to Mississippi reprinted a small article from the Nauvoo Neighbor of 24 April 1844, wherein the Saints boasted they could “bring, independent of any party, from two to five hundred thousand voters into the field.”[6] As quixotically unrealistic as they were, such numbers created a dangerous perception in Illinois and national politics. More editors began to judge that Joseph’s campaign would decide who would win the Prairie State and that it could even influence the national race—a fact church leaders already believed.

Joseph Smith as King and the Nation’s Best Hope

The nine days following the April 1844 conference were filled with activities of such importance to the political kingdom and Joseph’s candidacy that Council of Fifty clerk William Clayton wrote in his journal, “Much precious instructions were given, and it seems like heaven began on earth and the power of God is with us.”[7] Continuing to meet and plan for several days, the Twelve finalized the list of missionaries, their assignments, and the scheduled conferences. The spiritual climax of the Council of Fifty meetings in Joseph’s lifetime occurred on 11 April 1844. The prophet’s record of the day cryptically says, “In general council in Masonic Hall, morning and afternoon. Had a very interesting time. The Spirit of the Lord was with us, and we closed the council with loud shouts of Hosanna!” What was so “interesting” that it evoked “loud shouts of Hosanna”? William Clayton’s journal clarifies: “We had a glorious interview. Pres. J.[oseph Smith] was voted our P.[rophet] P.[riest] & K.[ing] with loud Hosannas.” Erastus Snow, who made the motion for such an anointing, said it was “the happiest moment he ever enjoyed.”[8] Though the office of king was an extension of the theological promises of the first and second anointings, it had overt political implications. Joseph was to be the “king and ruler over Israel,” not just in Israel. Joseph’s coronation did not give him more power. He remained the chairman of the Council of Fifty, whose decisions had to be unanimous, but it did demonstrate his frame of mind.

The idea of a king in a country founded on a revolt against monarchy was openly championed within the council’s deliberations. In the same meeting that Joseph received this kingship, Sidney Rigdon declared, “God designed that we should give our assent to the appointment of a King in the last days; and our religious, civil, and political salvation depends on that thing.”[9] The minutes record that another member said “he would like to have a king to reign in righteousness, and inasmuch as our president is proclaimed prophet, priest, and king, he is ready when the time comes to go tell the news to 10,000 people.”[10] But that time had not yet come. A week later Joseph warned, “It is not wisdom to use the term ‘king’ all the while.” Instead, Joseph told them to reference him as the “‘proper source’ instead of ‘king.’” The council members would understand what was meant, and any others would not have the opportunity to accuse Joseph and the council of treason.[11] Anxious not to have the council’s workings discovered, Joseph later stated, “We must suspend our meetings for the time being and keep silence on the subject, lest by our continual coming together we raise an excitement.”[12]

Yet the Council of Fifty met again on 25 April. New members grew the council to fifty-two men. The council established parliamentary procedures, including the need for unanimity regarding their decisions. The committee chosen to write the constitution of the kingdom of God had failed miserably. As reported in the minutes, Brigham questioned “the necessity to get up a constitution to govern us when we have all the revelations and laws to govern us. . . . He would rather have the revelations to form a constitution from than anything else we can get.”[13] Eleven days later, Joseph advised the council to “let the constitution alone,” for he had received it by revelation. He nonchalantly scribbled it down on a scrap of paper—“Verily thus saith the Lord, ye are my constitution, and I am your God, and ye are my spokesmen. From henceforth do as I shall command you. Saith the Lord.”[14]

John Taylor later explained the importance of being a part of such a “living constitution.” “It is expected of us that [we] can act right— . . . not acting for ourselves, but we are the spokesmen of God selected for that purpose in the interest of God and to bless and exalt all humanity.”[15] God chose his spokesmen, they received revelation on how to govern (aristarchy), and the people assented to their instructions (theodemocracy). As Brigham put it, “Let our president [Joseph] be elected, and let the people say amen to it.”[16]

Friends of Joseph had no qualms about his having such power, considering him the best hope for the nation. Eliza Snow, a plural wife of Joseph and older sister of future church president Lorenzo Snow, wrote:

Those who best knew him [Joseph]—those who comprehended the depth of his understanding, the greatness of his soul, the superhuman wisdom with which he was endowed, the magnitude of his calling as the leader of the dispensation of the fulness of times, and the mouthpiece of God to this generation, considered it a marked condescension for him to be willing to accept the position of President of the United States. . . .

[Yet] his friends were in earnest. They knew that through the revelations of God he was in possession of higher intelligence and more correct understanding of national policies, and particularly the needs of our own government as a republic, than any other man living.[17]

Ironically, Joseph set up the Council of Fifty with its emphasis on virtuous leadership at the very time that presidents of the United States had shed similar governance in favor of catering to the interests of partisan political parties. The latter would have deadly consequences.

In an unusual move, the Council of Fifty, while technically not a priesthood quorum, excommunicated dissenters William and Wilson Law and Robert D. Foster. Now apostates, these men would start their own church and print the Nauvoo Expositor in an effort to destroy Joseph’s reputation and his campaign. But before that occurred, the hundreds of electioneer missionaries just called would spread throughout the United States. These loyal missionaries took with them the confidence and enthusiasm of their leaders, believing that Joseph as president was the best chance for Zion and the last chance for the United States to avoid disaster.

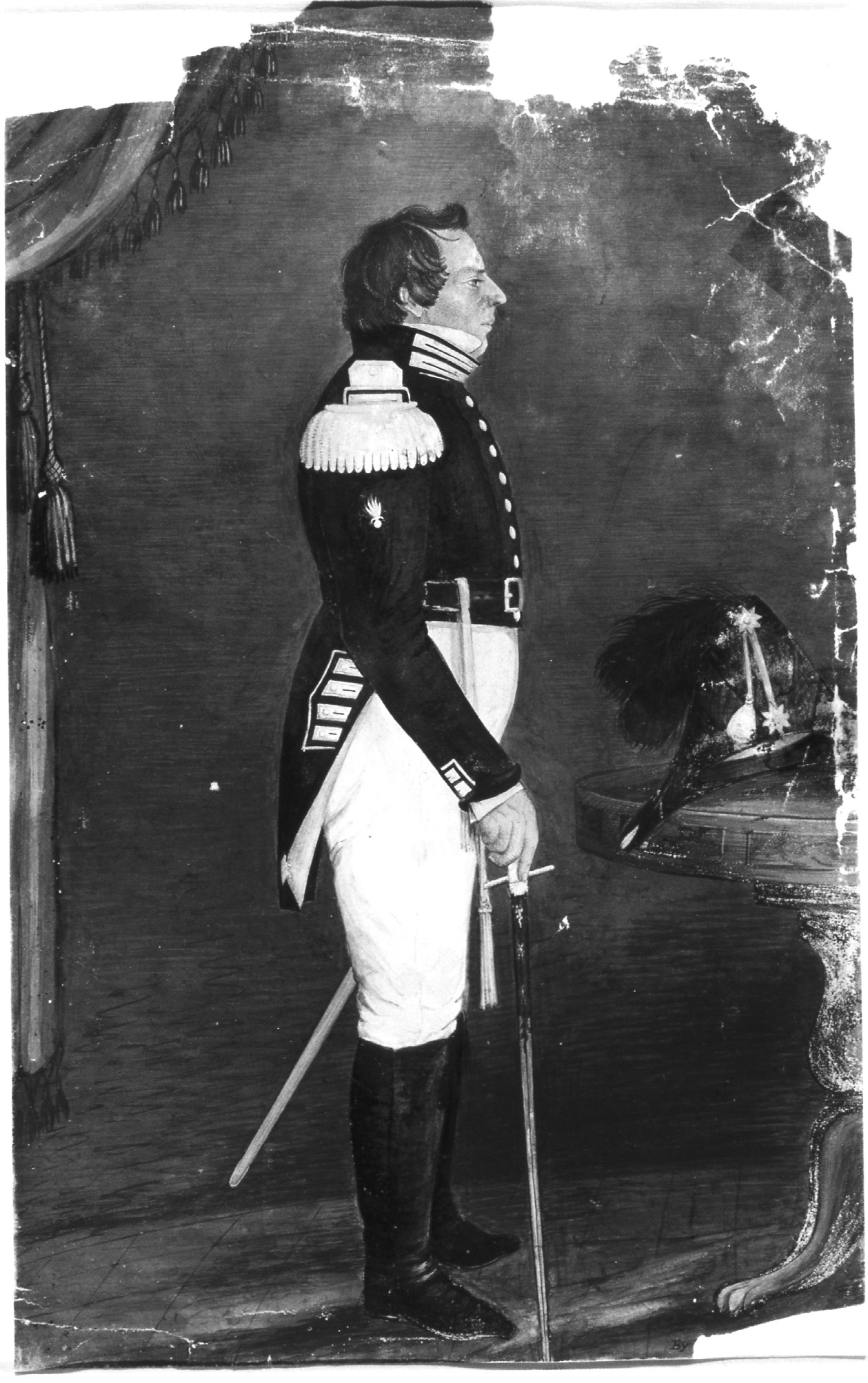

Lt. General Joseph Smith in Nauvoo Legion Uniform. 1842 painting by Sutcliffe Maudsley (1809–1881). Those advocating Joseph for president believed he alone could save the republic. Courtesy of Church History Museum.

Lt. General Joseph Smith in Nauvoo Legion Uniform. 1842 painting by Sutcliffe Maudsley (1809–1881). Those advocating Joseph for president believed he alone could save the republic. Courtesy of Church History Museum.

Two Campaign Centers

Joseph’s campaign had two national headquarters—Nauvoo in the West and New York City in the East. Each center had apostolic leaders who edited newspapers advocating Joseph’s nomination. Apostle and campaign manager John Taylor edited the Times and Seasons and Nauvoo Neighbor. In New York City, William Smith, apostle and younger brother of Joseph, became the editor of The Prophet. Through these newspapers, church leaders promoted Joseph’s candidacy and directed the campaign. They were key factors in a communication network that not only provided vital information but also bolstered morale.

Nauvoo

Once John Taylor published the names and assignments of the electioneers in the Times and Seasons on 15 April 1844, Nauvoo became a beehive of political activity. For two months, the electioneers departed almost daily. Joseph and the Council of Fifty continued to orchestrate the campaign as well as consider possible resettlement in Texas, California, or Oregon. More and more it seemed that Joseph’s election was the best option to protect Zion, so members of the Twelve continued recruiting more electioneers. Wilford Woodruff and Brigham Young recruited twenty-six volunteers in the nearby town of Lima, while Heber C. Kimball and George A. Smith journeyed to nearby Ramus and netted six more.

Church leaders’ actions within and without the Council of Fifty through April and May showed a deliberate and optimistic approach to the campaign. During the 11 April Council of Fifty meeting, Orson Spencer was “certain of success” in the campaign because of “the union which exists in our midst.”[18] “Unity is power,” Joseph had written in Views. Spencer believed it and was not alone. David D. Yearsley became more outspoken during the meetings on 11 and 18 April. “He wished the day would soon come when he could have the privilege of proclaiming to the heads at Washington that the kingdom of God was set up.”[19] He believed the kingdom should be publicly set up in Nauvoo right then. Appointed a campaign president for Pennsylvania, he believed that as king, Joseph already had all the necessary power and authority. “How can a man be elected president when he is already proclaimed king?” he asked his colleagues. Yet Yearsley was eager for his electioneer mission. The campaign to him was a “scarecrow” to “blind the . . . people” into electing Joseph, who was already king. Then the government of God could be “upheld” in Nauvoo as the prophet announced the kingdom of God with himself as its mortal king until Christ returned.[20] Others like Lorenzo D. Wasson also advocated the idea of moving the government to Nauvoo once the election was secured. We are not “playing child’s play,” he declared. “Our president don’t care to go to Washington,” Wasson continued. The men they were sending out would bring the needed success. “Our elders,” he proclaimed, “are considered as the most ignorant men in the world, but when they open their mouths, they silence the multitudes.” The cadre of electioneers would help “revolutionize the world by intelligence.”[21]

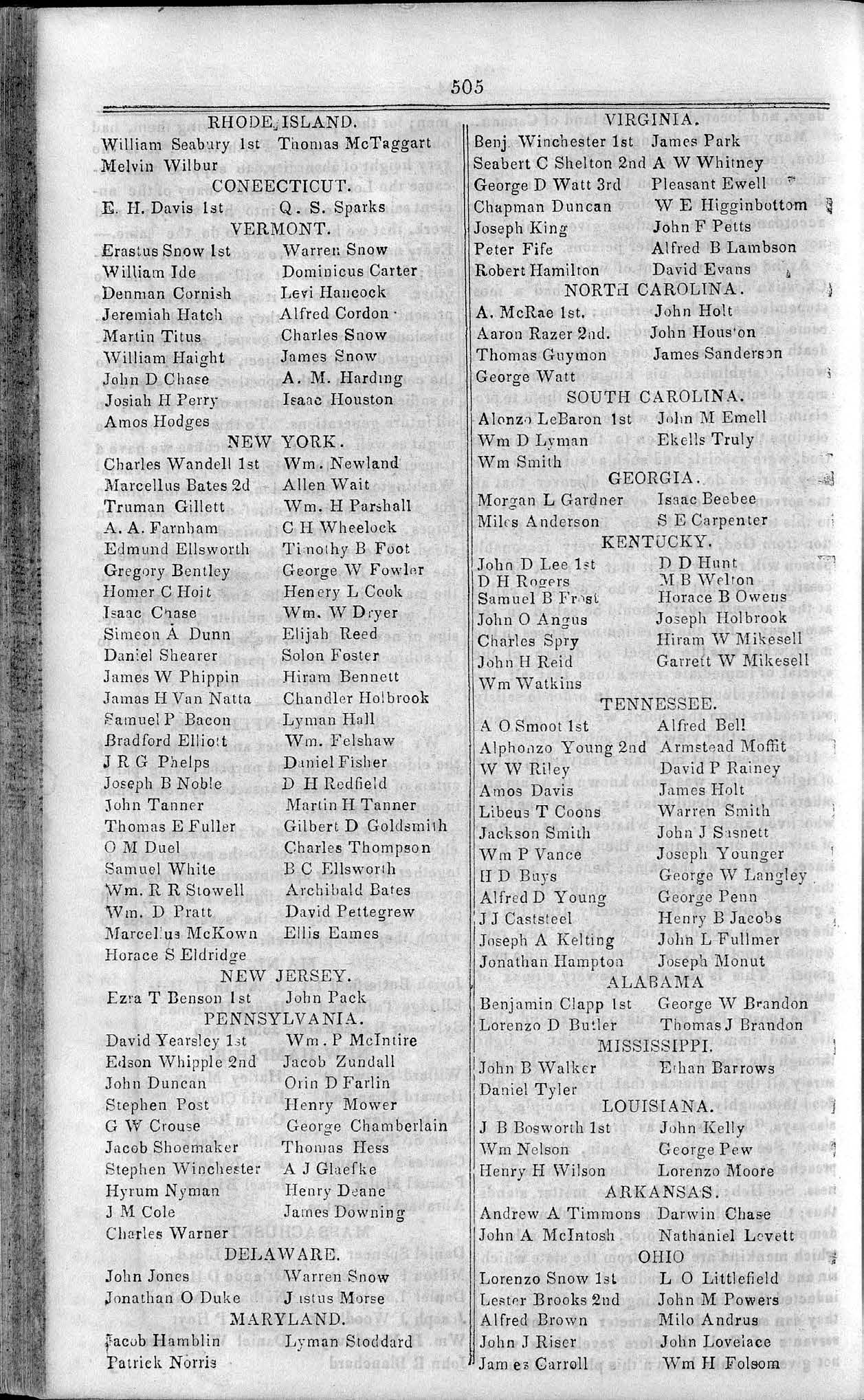

Page from the 15 April 1844 Times and Seasons listing electioneer assignments. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Page from the 15 April 1844 Times and Seasons listing electioneer assignments. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Joseph agreed with the need to have an independent government. “We [the Council of Fifty] consider ourselves the head, and Washington the tail,” Joseph asserted. Wherever they found independence, the laws of the political kingdom of God would be perceived as merely “part of our religion . . . until we get strong enough to protect ourselves.” Then Joseph brought the conversation back to why they were running the campaign in the first place. “We want to alter it [the Constitution] so as to make it imperative on the officers to enforce the protection of all men in their rights.”[22]

Church leaders held a public meeting in Nauvoo on 23 April 1844 “for the purpose of consulting upon measures for the furtherance of our designs in the next presidential election.” Several men addressed the gathering “in a very spirited manner.” It was in this meeting that they determined that Joseph’s campaign could, as mentioned earlier, “bring, independent of any party, from two to five hundred thousand voters into the field.”[23] Although in retrospect such numbers seem overly optimistic, church leaders were not alone in making such forecasts. Important newspapers around the country printed similar statistics.

Joseph was playing a wider hand than just pushing forward his own political campaign. The meeting on 23 April assigned electioneer and Council of Fifty member David S. Hollister “to attend to the Baltimore Convention [of the Democratic Party], to make overtures to that body.”[24] Just what specific “overtures” Hollister was to present are unknown, but later national speculation included arrangements to exchange the Latter-day Saint vote for protection, redress, or even the vice presidency for Joseph. Such supposition combined with exaggerated numbers of Latter-day Saint and allied voters received attention nationwide. The perception that the Saints’ vote would be important in the upcoming election was gaining momentum nationally and within both political parties.[25] As the public meeting of church leaders concluded, “it was resolved that a state convention be held in the City of Nauvoo on the second day of May next” (later changed to 17 May).[26] Hollister left immediately for the Democratic National Convention.

At the 25 April meeting, buoyed by the success of the public meeting two days earlier, Council of Fifty members decided to put their full weight behind the campaign. Joseph proposed that “those of this council who could, should go forth immediately to electioneer.” He had decided that “the easiest and best way to accomplish the object in view [was] to make an effort to secure the election at this contest.” Joseph instructed, “Let us have delegates in all the electoral districts and hold a national convention at Baltimore.” Other members concurred with this “wise movement,” confident that the “work [would] be accomplished.”

Willard Richards reminded the council that “since conference the Twelve [had] been using their endeavors to send the elders abroad and give them the necessary instruction.” He proposed instructing the electioneers still in Nauvoo “relative to the object of the mission.” Joseph agreed. He had complete confidence in the electioneer cadre and wanted the Twelve at the coming meeting to instill that same surety in them. “Let every man [electioneer] assume an authoritative station,” Joseph instructed, “as though he were somebody.”[27] Thus the electioneers were key to the campaign’s success and needed to understand that while on their missions.

Members of the Council of Fifty were not finished finding ways to ensure the prophet’s election. They voted “to establish a weekly periodical . . . in all . . . principal cities in the East, West, North, South and every other place practicable.” These newspapers would “advocate the claims of . . . Joseph Smith for the presidential chair under the title of Jeffersonian Democracy.”[28] Advocates for Joseph used the term Jeffersonian Democracy throughout the campaign. Jeffersonian ideals of Republicanism dominated American politics until the rise of Andrew Jackson and the new “Democracy.” The associated values included representative democracy to prevent the tyranny of the majority, “natural aristocracy” of virtue and talent, yeoman farming, and the belief that government should not violate individuals’ rights of property or person. Many of these themes dovetailed nicely with Joseph’s aristarchic theodemocracy: “I go emphatically, virtuously, and humanely for a THEODEMOCRACY, where God and the people hold the power to conduct the affairs of men in righteousness. And where liberty, free trade, and sailor’s rights, and the protection of life and property shall be maintained inviolate, for the benefit of ALL.”[29]

With the rise of the Jacksonian Democrats and Whigs, Latter-day Saints were similar to other Americans who believed the new politics had corrupted true Republicanism. Thus, in looking for a way to best translate theodemocracy for a gentile audience, church leaders saw in Jeffersonian Democracy what seemed both a good fit and possible enticement for like-minded, disillusioned citizens. With their plans seemingly complete, the council adjourned sine die. Two days later, on 27 April 1844, church leaders held a public assembly in which Sidney Rigdon and William Smith instructed the electioneers who had not yet departed on the expectations of their assignments. If they had not caught on yet, the electioneer missionaries now knew that their leaders were both serious and confident about Joseph’s election campaign.

On 3 May Joseph once again called on council members and potential recruits to “go into all the states and preach and electioneer for him to be president. And when he is president we can send out ministers plenipotentiary, who will secure to themselves such influence that when their office shall cease they may be received into everlasting habitations.”[30] There is much to unpack in that last sentence from the minutes. First, Joseph, basking in the unity of the Council of Fifty in supporting his candidacy, seemed confident he would win the election. Furthermore, he was already thinking of the roles of the council members and electioneers following the election as “plenipotentiary” ministers. A plenipotentiary, as defined by a contemporary dictionary, was “a person invested with full power to transact any business; usually, an embassador [sic] or envoy to a foreign court, furnished with full power to negotiate a treaty or to transact other business.”[31]

Joseph envisioned that after securing the presidency he would use council members and former electioneers acting in their name as influential ministers of theodemocratic government. In their individual governing offices, this virtuous aristarchy of the incipient political kingdom of God would represent and rule until their death, at which point they would be gloriously “received into everlasting habitations.” This plan was the natural conclusion of aristarchic theodemocracy, which these men had been instructed in and had sacrificed to bring about. Their appointment to official government offices would reward their loyalty and sacrifice. “Joseph’s measures” would not be lost on Brigham Young and the other apostles present.[32] When it became their turn to lead the church, they would use electioneer cadre members to represent them as the regional and local leaders of the kingdom of God.

Three days later, on 6 May 1844, the council reconvened. Once again Joseph stressed that “all who could, should go electioneering,” although some council members would need to “tarry . . . until they be endued with power.”[33] Indeed, a handful of the men added to the council had not yet received their temple endowment, and they needed the power in the promises of being future kings and priests. Thus, before they left to electioneer, council members Sidney Rigdon, John P. Greene, William Smith, Almon Babbitt, and Lyman Wight were endowed. The date for the campaign’s Illinois State Convention was finalized as 17 May. During that event, the prophet’s national convention would be planned. In the 6 May meeting Joseph encouraged those present (and, through them, the electioneers already out in the field) to “work by faith and revolutionize the world, not by power, nor by might, but by pure intelligence.” Continuing, he “prophesied in the name of the Lord” that “the elders should have more power and more might and more means than they ever had before,” even “one hundredfold.”[34] Those present seemed confident that a special power, influence, and intelligence would accompany the electioneer missionaries in their work of convincing the electorate that Joseph should be president.

Still without a formal vice-presidential nominee, Joseph declared he wanted Sidney Rigdon “to go to Pennsylvania and run for vice president.” Rigdon would need to establish residency in Pennsylvania in order to abide by the Constitution’s provision that the president and vice president be from different states. Rigdon enthusiastically accepted. Lyman Wight reminded the council of a prophecy in which God promised to “vex the nations,” particularly the United States.[35] “The nation could not be vexed worse than for Joseph to be president and brother Rigdon vice president,” Wight stated. In Joseph Smith’s and Sidney Rigdon’s minds, their electoral ticket was prophecy being fulfilled. Rigdon “referred to a former prophecy and said I am satisfied God intends to just what we are doing.” Joseph “confirmed it.”[36]

Candidates for president at the time were pledging to serve only one term as a means of preventing corruption. With this in mind, Rigdon requested a privilege—that after Joseph had been president for four years, Sidney could be president the next term. The council granted the request and Rigdon proclaimed, “As the Lord God lives, Joseph shall be president next term and I will follow him.”[37]

On 13 May, four days before the Illinois State Convention, the council met to discuss a letter from Orson Hyde. He reported that their petitions were at a dead end in the capitol. Furious at Congress for once again denying the Saints, the council wrote that “all representatives and senators who do not use their influence as is their duty to do to pass the memorials unaltered shall be politically damned.” It was time for “Congress to awake” to the sovereignty of the people and, as their servants, obey. The council also believed they were the representatives of the Sovereign and would not “stop to inquire of Congress what is popular or unpopular.” Rather, they wrote, “We will tell them what is right and what is wrong; and if they will not make right popular, we will turn them out, and put men there who will.”[38] Ultimately Hyde would write in June that both houses of Congress and President Tyler refused to move on the petitions. During the meeting, John Taylor, Edward Hunter, and Reynolds Cahoon “were appointed a committee of arrangements for the state convention” that was just days away.[39]

Meanwhile, Joseph’s enemies plotted his downfall. Having obtained a printing press from a Whig operative, William and Wilson Law, Robert B. Foster (each of them Whigs), and other apostates printed a prospectus on 10 May for a weekly paper named the Nauvoo Expositor. True to its name, the leaflet claimed the forthcoming paper would expose Joseph as a fallen prophet and corrupt leader. The following Sunday, Joseph responded from the pulpit that he was still a prophet and that his enemies were the deceivers. Tension between the two sides mounted with rumors, threats, and counterthreats. In its early May meetings, the Council of Fifty closely followed the actions of the apostates, eventually deciding to hand the Laws, the Fosters, and Chauncey L. and Francis M. Higbee “over to the buffetings of Satan.”[40]

Two days before the convention, three influential politicians visited Nauvoo and the prophet. The first, William G. Goforth, was known by Joseph and the Saints and was arriving for the state convention at their invitation. While traveling on a steamboat, Goforth struck up a conversation with fellow passengers Charles Francis Adams and Josiah Quincy. Adams was the son of former president John Quincy Adams and would soon be a political heavyweight in the Whig and Free-Soil parties. Josiah Quincy would become mayor of Boston the next year. Goforth convinced his fellow Whig politicians to stop in Nauvoo to meet the prophet. Goforth informed them that he was attending the Saints’ political convention to persuade them to vote for Henry Clay. The three Whigs spent the next day touring Nauvoo with Joseph. The city and the sheer number of Joseph’s followers there on the edge of civilization impressed them.

Toward the end of the day the discussion inevitably turned to politics. Adams and Quincy, both abolitionists, applauded the prophet’s dedication to end slavery. Quincy, decades later, would write that Joseph had been a true statesman for publishing a plan to end slavery that might have avoided the “terrible cost of the fratricidal [civil] war.” The conversation shifted to Henry Clay’s recent nomination by the Whig Party. Joseph railed against Clay’s ambivalence toward the Saints. Pointing to Goforth, Joseph declared, “He might have spared himself the trouble of coming to Nauvoo to electioneer for [Clay, who] . . . was not brave enough to protect the Saints in their rights as American citizens.” Joseph then discussed his Views with the visitors and at parting mentioned “that he might one day so hold the balance between parties as to render his election to that office by no means unlikely.”[41]

Apparently, Joseph shared such sentiments not only with famous or influential visitors but also with everyday boarders in the Mansion House. A young teacher named Ephraim Ingals spent two weeks visiting Nauvoo during this time. He remembered sitting “at the same table” with Joseph and “saw a good amount of him,” often conversing with him. He recalled that Joseph often talked about his candidacy for the presidency, expressing “his belief that he would be elected.” The boarders who were not from Nauvoo told him that they believed no one outside the city would vote for him. When asked about the source of his optimism, Joseph simply replied, “The Lord will turn the hearts of the people.”[42]

Meanwhile, John Taylor drummed up support in the Nauvoo Neighbor for the upcoming convention: “Rally around the standard of freedom which Gen. Smith has raised, battle for liberty side by side with this patriot; enter the political campaign, determined, by all honorable means, to throw off the great burden of corruption under which our beloved country groans, and victory will be the reward of our exertions.” Taylor exuded urgency: “Every friend to the triumph of Gen. Smith should be vigilant . . . and use every exertion to secure his success.” He declared, “Delay not a moment—the time is short—what remains to be done must be done quickly.” According to Taylor, only Joseph’s election could save the republic. “Look to him, ye virtuous and patriotic; rally around his standard as the best standard of liberty; fight under his banner, for the salvation of a country whose freedom is jeopardized and whose liberty is endangered,” he implored.[43]

When the state convention convened on 17 May 1844, it appointed electioneer cadre member Uriah Brown as its president. Although not a Latter-day Saint, Brown was a senior member of the Council of Fifty. Brown introduced William G. Goforth and other prominent visitors. Next William W. Phelps read Henry Clay’s letter to the prophet. When Phelps read aloud Joseph’s rejoinder castigating Clay, the convention audience applauded with three cheers—a clear sign to Goforth that the Saints were not going to vote for Clay. Then the convention created a committee of five to draft resolutions. The committee was composed of electioneers Dr. William G. Goforth (a non–Latter-day Saint), William W. Phelps, Lucian R. Foster, and apostles John Taylor and William Smith. Next the convention assigned apostle Willard Richards and electioneer colleagues Dr. John M. Bernhisel, William W. Phelps, and Lucian R. Foster as the Central Committee of Correspondence. They were some of the few political veterans available to help Joseph. A final committee to appoint electors for Illinois included electioneer comrades Dr. William G. Goforth, Lloyd Robinson, Lucius N. Scovil, Peter Hawes, and John S. Reid. Reid, who was not a member of the church, had been Joseph’s attorney in New York in 1830 and happened to be in Nauvoo during the convention.

Seventy delegates, representing each of the states and almost every county of Illinois, voted that “General Joseph Smith, of Illinois, be the choice of this convention for President of the United States.” Members of the Committee on Resolutions then presented their work using words rich with the prophet’s concepts of Zion, aristarchy, theodemocracy, and the kingdom of God. They declared it was “highly necessary that a virtuous people should arise” and “with one heart and one mind” correct government by “electing wise and honorable men to fill the various offices of government.” The electioneers who had already left were “to take charge of [Zion’s] political interests, [and] . . . use every exertion to appoint electors in the several electoral districts of the states which they represent.” The electors were to give “stump speeches” in their districts and then attend Joseph’s national convention in Baltimore on 13 July.[44]

Sidney Rigdon then addressed the meeting, needling both Henry Clay and Martin Van Buren for political dishonesty. Joseph, according to the official report, “spoke with much talent and ability, and displayed a great knowledge of the political history of this nation, of the cause of the evils under which our nation groans, and also the remedy.” When influential Whig Goforth arose, instead of outwardly advocating for Clay, he declared he felt “the spirit of obedience that was required of one of old, when he was bade to take off his shoes, for he was walking on holy ground, and that this was a holy cause. . . . The Jeffersonian doctrines have been forsaken,” Goforth stated; “merit and qualification have been abandoned.” He chose to attack the Democrats, and particularly Van Buren, for abuses against the Saints.

To finish Goforth announced, “May we now say that in 1844 Joseph Smith, the proclaimer of Jefferson democracy, of free trade and sailors’ rights and protection of person and property, with us stands first to the [Democratic National Convention at Baltimore].” Goforth added parenthetically that if Joseph’s nomination met with no tangible success at the convention, the gathered delegates should be instructed to support Henry Clay.[45] Goforth felt he had cleverly left the door open to Latter-day Saint support for Clay. John S. Reid spoke of his friendship with Joseph ever since he defended him fourteen years earlier in New York. Appalled both then and since at the treatment of the prophet and his followers, Reid pledged to support their cause. At this point Uriah Brown, an electioneer who was not a Latter-day Saint, adjourned the convention. Joseph and the Council of Fifty had gone out of their way to prominently include as many non–Latter-day Saints friendly to their cause as possible to demonstrate that Joseph could relate to and be elected by those outside the church.

Exhausted, Joseph went home to care for his Emma, who was ill. Even a late afternoon of heavy rain could not extinguish the excitement in Nauvoo about his formal candidacy. Later that evening “the band assembled . . . and several national airs were played, [and] a song prepared for the occasion was sung by Mr. Levi Hancock, and speeches delivered by a number of gentlemen.” Joseph, hearing the commotion, stepped outside and saw the large assembly gathered up the street. The celebrants were burning a barrel of tar and toasting the prophet’s nomination. When the crowd realized his presence, they carried him on their shoulders twice around the barrel. “The names of Gen. Smith and Sidney Rigdon . . . and Jeffersonian democracy were repeated with universal acclamation until the sound reverberated from hilltop to hilltop.” The assembly and band escorted Joseph back to the Mansion House, and “three cheers were given at the ‘Mansion’ for the General and Sidney Rigdon, which closed the proceedings of the day.” Excitement pervaded the city.[46]

The following week, on 25 May, the Council of Fifty held its second-to-last meeting of 1844. It was the last meeting that would discuss the campaign. The council read another letter from Orson Hyde about his interactions with congressmen regarding the church’s petitions for redress of grievances. Frustrated, Hyde saw fit to leave the details of the ongoing negotiations to Orson Pratt and was going to start electioneering the following day. The letter contains a phrase that best exemplifies the determination and loyalty of the council and the electioneer cadre to Joseph. Hyde wrote, “Whatever course you [Joseph] shall determine to steer . . . I am with you, heart, hand, property, life, and honor.”[47] The council instructed Willard Richards to write their response. The letter, using a play on words, told Hyde that “success at present depends on our faith in the doctrine of election” and that “our faith must be made manifest by our works, and every honorable exertion made to elect Gen. Smith.”[48] Furthermore, council and cadre members were with Joseph “heart, hand, property, life, and honor.” The foremost doctrine of the Council of Fifty, the electioneer missionaries, and the church itself were to work together for the election of Joseph Smith to the presidency of the United States.

On 29 May John Taylor declared in the Nauvoo Neighbor, “Every individual desirous to secure the election of Gen. Smith should use every effort in his power to procure as great a number of subscribers to the Neighbor as possible.” Taylor declared, “We have a great and mighty object before us; and union, energy, and untiring industry of all will effect its glorious consummation.”[49] In a separate article, Taylor praised the “I WILL DO IT!” spirit of the Latter-day Saints and declared, “Huzza for Joseph Smith for the next president, and let all the people say ‘amen!’” Taylor declared that the Philadelphia Bible Riots, which targeted Catholic immigrants, proved the nation was descending into chaos. The country needed Joseph Smith:

So ye wise men, who’ve nothing else to do,

Help save the land from wo;

And rise in your might, like freemen ever true,

And elect our Gen’ral Joe![50]

The confident and celebratory mood in Nauvoo as June began was captured in a contemporary letter from apostles Brigham Young and Willard Richards to church leader Reuben Hedlock in England: “All things are going on gloriously at Nauvoo. We shall make a great wake in the nation. Joseph for President. . . . We have already received several hundred volunteers to go out electioneering and preaching and more offering. We go for storming the nation.”[51]

New York City

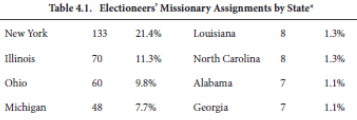

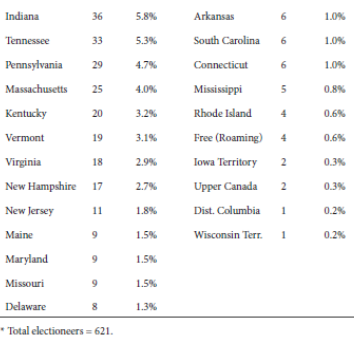

Latter-day Saint electioneers stormed New York more than any other state. One hundred and thirty missionaries, 21 percent of the total, labored in the Empire State (see table 4.1). Illinois, the second state with the highest percentage of electioneers, received only half as many. New York, the birthplace of the church, became the key state in the election of 1844 for Latter-day Saints and other Americans alike. On 2 April 1844 apostle William Smith and printer George T. Leach created a political association— the Society for the Diffusion of Truth—in New York City to promote Joseph’s candidacy. Soon after its organization, Smith assigned Leach to raise funds and publish a newspaper and then left for Nauvoo. Leach acquired a press and a shop in the famous Park Row of lower Manhattan. Within a few blocks’ radius, almost a dozen partisan printing houses competed to disseminate their views, the New York Herald being the only supposedly neutral exception. The area’s ambience, however, was definitively Democratic. The Saints’ printshop was contiguous to Democrat headquarters Tammany Hall and just down the street from the Democratic-dominated city hall.

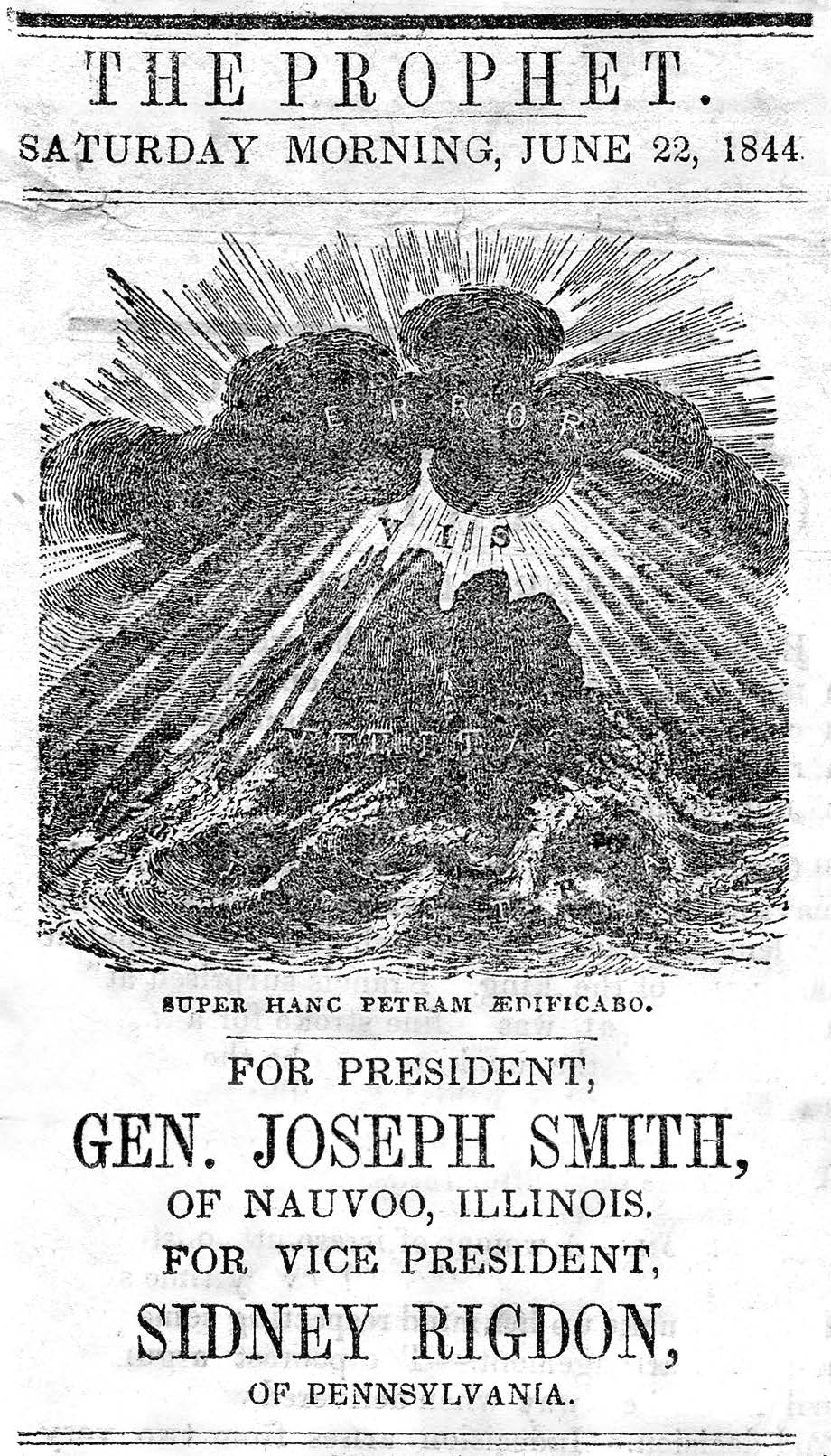

The first issue of the society’s weekly, named The Prophet, was printed on 18 May. Leach edited the paper with Samuel Brannan until William Smith returned in June.[52] The first number sounded the same theodemocratic themes advocated in Nauvoo: “God does nothing except he revealeth his secrets unto his servants the prophets; therefore it ceases to be a wonder that we should feel anxious to hold him up before the people as a candidate for the next Presidency, for the glory and safety of our nation, for this very reason, that God shall govern and control all your proceedings through his servant Joseph Smith. And we wish the brethren and all those who would wish to see righteousness prevail over wickedness to be unanimous in their choice and use all the influence they can to secure his election.”

The first issue of The Prophet also reprinted the 15 April 1844 Times and Seasons list of electioneers and the instructions given to them under the headline “For President GEN. JOSEPH SMITH of Nauvoo, Illinois ‘A Western man with American principles.’” Leach advertised for “a few intelligent active men [who] wanted to canvass for the Prophet” and help increase the paper’s circulation.

Page from The Prophet newspaper printed in New York City declaring Joseph’s candidacy.

Page from The Prophet newspaper printed in New York City declaring Joseph’s candidacy.

Courtesy of Church History Library.

The main editorial of the issue announced, “We this week have hoisted the banner and placed before the world as a candidate for the Chief Magistracy of this Republic the Prophet of the last days, General Joseph Smith of Nauvoo, Ill, and pledge ourselves to use our utmost endeavor to assure his election, being satisfied that he will administer the laws of his country without reference to party, sect, or local prejudice.” Leach reported, “We would say to our friends that our prospects are encouraging.” His office had received “communications from various parts of the country, hailing [Joseph’s] nomination with joy, and we feel confident that if the intelligence of the American people prevail over their prejudice, he will be elected by a large majority.”[53]

In a time and location of intense partisanship, Leach pleaded for the “friends of Justice, of Truth, Humanity, and of God to examine [Joseph’s] views and let the love of country predominate over the love of party, and through the ballot box we will strike a blow at oppression, hypocrisy, injustice and treachery.” He declared, “We have counted the cost of ‘opposing the popular errors of the day,’ and can say with continued patronage of the liberal and philanthropic portion of our community that we will . . . eventually . . . make way for the glorious reign of [the] Son of Peace.” Having received both compromise overtures and threats from other politicos in Park Row, Leach responded, “We are not to be bought by promise or intimidated by threat, but our course will be directed by an eye single to the glory of God and the good of mankind at large.”[54]

A week later Leach printed, “Let the friends of Gen. Joseph Smith organize immediately in every state, in every town and village, throughout the wide extent of our Republic, and let no stone be unturned that will tend to secure his election, [for] . . . we know our rights as American citizens, that we are both willing and able to defend them, through the medium allotted by our Constitution, viz. the ballot box.” Leach sought to rally those who might be reluctant to publicly support Joseph Smith: “Let the movement not slack by your negligence of duty, for it is a sacred duty you owe to your God, and the cause of truth and humanity, to sustain the effort now made by the free and independent of all parties and of all sects to place at the head of our once happy country a man of God, an honest, independent man, influenced by the spirit of the Living God, the spirit that actuated a Washington, [an] Adams, a Jefferson, a Hancock, and a Franklin of the times that ‘tried men’s souls.’” The Prophet consciously sought to tie Joseph to the Founding Fathers.[55]

Leach and Brannan railed against party politics again on 8 June 1844. After reprinting Joseph’s Views, their editorial declared, “We contend for principles unbiased by party, sect, or local prejudices.” They understood that some “looked upon [them] as ridiculous . . . because [they had] the moral courage to step out of the beaten track of party hacks and sectarian demagogues and think for [themselves], . . . [for they were] not as mere machines . . . to be used as tools by men whose only aim is self-exaltation.” Yet this is exactly how many saw both the Saints and Joseph’s campaign. For many gentiles the only difference was that the Saint’s political party was religious and controlled by a “prophet” who was often characterized as another controlling pope or “modern Mohamet.” A religious leader as a presidential candidate was even more contentious in a nation defiant of ecclesiastical control over politics, as was being witnessed in the Philadelphia Bible Riots. While many Latter-day Saints may not have sensed their political campaign was a threat to other Americans, it was seen that way. To be sure, most people outside the church misunderstood the deep sincerity of the Zion principle of unity that motivated the Saints. When Leach and Brannan wrote in their 8 June editorial, “Would to God that our citizens, one and all, would take the same stand, and we would then select officers for the good of the country, and not for the especial advancement of faction,” they believed that everyone could choose to believe the same and unite with them.

Yet most Americans looked at party politics as the way to advance their self-interests in a pluralistic society. In a nation with no state religion, politics, as French observer Alexis de Tocqueville noted, was the state religion. Where the Old World held elaborate state-run religious celebrations, Americans religiously politicked. Latter-day Saints, however, did not see the American republic as a triumphant end or great experiment in democracy, but rather as the preparatory means for establishing the kingdom of God on earth. On that view, government need not depend on the competition of parties within a pluralistic framework but can be the natural, peaceful, virtuous outgrowth of a people united by the desire to please heaven. “What true lover of his country can look at the two great political parties without shedding a tear for the tarnished honor of his beloved country?” questioned Leach and Brannan.

* * *

Before returning to New York to assume editorship of The Prophet, apostle William Smith was initiated into the Council of Fifty and attended the Illinois State Convention. Undoubtedly influenced by the public teachings of Joseph and the private teachings within the Council of Fifty, the editors in Nauvoo and New York ably amplified Joseph’s ideas of establishing theodemocracy, aristarchy, and the kingdom of God. As William Smith left Nauvoo in late May, however, he was only one of hundreds who fanned out to preach the restored gospel and campaign for Joseph. Collectively they became the most unique campaigners in American political history as well as the most unique missionary force The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints would ever field.

Notes

[1] Richards to James Arlington Bennet, 20 June 1844.

[2] “Highly Important from the Mormon Empire,” New York Herald, 17 June 1842, 2.

[3] “Highly Important from the Far West,” New York Herald, 3 July 1841, 1; and “Highly Important from the Mormon Country on the Mississippi,” New York Herald, 15 January 1842, 1.

[4] Correspondence, New York Herald, 17 June 1842, 2.

[5] Correspondence of the Daily Missouri Republican, June [?] 1844. The letter to the editors, under the title “Life in Nauvoo,” was sent from Nauvoo and dated 25 April 1844. Viewable at http://

[6] John Taylor and William Clayton, “Public Meeting,” Nauvoo Neighbor, 24 April 1844, 2.

[7] Journal of William Clayton, 18 April 1844, as quoted in Ehat, “Heaven Began on Earth,” 13.

[8] Council of Fifty, Minutes, 11 April 1844, in JSP, CFM:95; original capitalization preserved.

[9] JSP, CFM:104 (11 April 1844); original capitalization preserved. Much of this paragraph relies heavily on Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 522–23.

[10] G. J. Adams, JSP, CFM:105.

[11] JSP, CFM:128 (18 April 1844).

[12] JSP, CFM:133 (25 April 1844).

[13] JSP, CFM:120 (14 April 1844).

[14] JSP, CFM:130, 135–37 (25 April 1844).

[15] Minutes, 3 February 1849, Council of Fifty, Papers, 1844–1885, CHL; and Nuttall, Notebook, 8 April 1881.

[16] JSP, CFM:121 (18 April 1844).

[17] Eliza Snow, Biography and Family Record, 75.

[18] JSP, CFM:105.

[19] JSP, CFM:106.

[20] JSP, CFM:125.

[21] JSP, CFM:127.

[22] JSP, CFM:128, 129.

[23] John Taylor and William Clayton, “Public Meeting,” Nauvoo Neighbor, 24 April 1844, 2.

[24] Taylor and Clayton, “Public Meeting,” Nauvoo Neighbor, 24 April 1844, 2.

[25] See Baker, Murder of the Mormon Prophet, 247–48. Baker lists numerous newspaper articles showing that Joseph’s campaign and potential negotiations with Democrats were widespread.

[26] Taylor and Clayton, “Public Meeting,” 2.

[27] JSP, CFM:133–35.

[28] JSP, CFM:135.

[29] Times and Seasons, 15 April 1844, 510; original capitalization preserved.

[30] JSP, CFM:139.

[31] Webster, American Dictionary of the English Language (1828), s.v. “plenipotentiary.”

[32] “Conference Minutes,” Times and Seasons, 1 November 1844, 694.

[33] JSP, CFM:157.

[34] JSP, CFM:157.

[35] The Doctrine and Covenants foretells God’s vexing the nations in three passages: “vex the Gentiles” (87:5), “vex all people” (97:23), and “vex the nation [the United States]” (101:89). The last is likely the one Wight had in mind since it states the vexing would come if the president of the United States rejected the Saints’ petitions.

[36] JSP, CFM:157, 158.

[37] JSP, CFM:158.

[38] JSP, CFM:164.

[39] JSP, CFM:163.

[40] JSP, CFM:154–55 (6 May 1844).

[41] Mulder and Mortensen, Among the Mormons, 141.

[42] Ephraim Ingals, “Autobiography of Dr. Ephraim Ingals,” 279–308.

[43] “The State Convention,” Nauvoo Neighbor, 15 May 1844, 2.

[44] “State Convention,” Nauvoo Neighbor, 22 May 1844, 2.

[45] “State Convention,” Nauvoo Neighbor, 22 May 1844, 2.

[46] “State Convention,” Nauvoo Neighbor, 22 May 1844, 2. See JSJ, 17 May 1844.

[47] Hyde to “Dear Brethren,” 30 April 1844.

[48] Richards to Orson Hyde, 25 May 1844.

[49] John Taylor, “For President, Gen. Joseph Smith,” Nauvoo Neighbor, 29 May 1844, 2.

[50] John Taylor, “Do It,” Nauvoo Neighbor, 29 May 1844, 2; emphasis in original.

[51] Young and Richards to Reuben Hedlock, 3 May 1844.

[52] The press also printed a forty-one-page “pamphlet, featuring four works that would have been useful for electioneering missionaries, . . . published as Americans, Read!!! Gen. Joseph Smith’s Views of the Powers and Policy of the Government of the United States. An Appeal to the Green Mountain Boys. Correspondence with the Hon. John C Calhoun. Also a Copy of a Memorial to the Legislature of Missouri (New York: E. J. Bevin, 1844).” Crawley, Descriptive Bibliography of the Mormon Church, 1:258.

[53] The Prophet, 18 May 1844, 2; original capitalization and emphasis retained.

[54] “For President, Gen. Joseph Smith of Nauvoo, Illinois,” The Prophet, 25 May 1844, 2.

[55] “For President, Gen. Joseph Smith of Nauvoo, Illinois,” The Prophet, 1 June 1844, 2.