The Assassination and Aftermath

Derek R. Sainsbury, “The Assassination and Aftermath,” in Storming the Nation: The Unknown Contributions of Joseph Smith’s Political Missionaries (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 143‒70.

“Instead of electing your leader the chief magistrate of this nation,

they have martyred him.”[1]

—An angel to John D. Lee, 8 July 1844

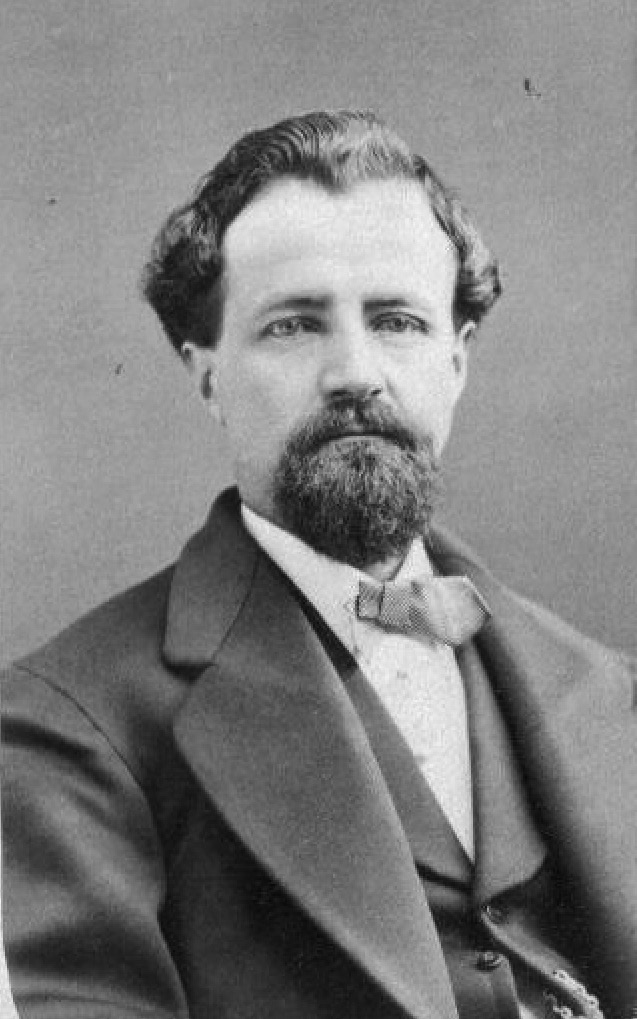

Electioneer Experience: William I. Appleby. On 5 May 1844, after preaching in the East for a year, William Appleby encountered electioneer John Wakefield, who gave him a copy of Views to acquaint him with Joseph’s political platform. The two men discussed the campaign plan of “hundreds of elders . . . abroad in the states, delivering lectures regarding [Views] . . . and holding up Joseph as [a] fit candidate for the office [of presidency]. Accordingly, in the evening, we both lectured on the powers and policy of the government.” Appleby electioneered across Pennsylvania while en route to Philadelphia, arriving on 13 May. He toured the neighborhood where the Bible Riots had erupted the previous week. “Viewed some of the burning ruins of St. Augustine’s Church,” he penned, “[and] the bullet holes in houses . . . &c, occasioned by a riotous mob a few days before, in the which several were killed and wounded.” The escalating tensions “between the native Americans [i.e., native-born citizens, or “nativists”] and the [immigrant] Catholics,” initially a disagreement over which version of the Bible should be used in public schools, ignited several days of riots. Appleby saw firsthand the grim result of the deadly violence that Protestants (principally Whigs and more particularly nativists) were willing to inflict on the Catholic minority of mostly immigrants. What he did not know was that enemies would resort to similar violence a month later against the man he was canvassing for—Joseph Smith.[2]

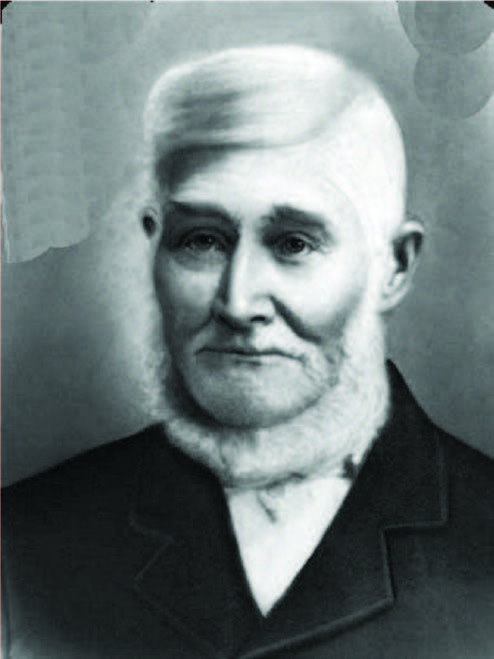

After adding his political talent to Joseph’s campaign, William I. Appleby calmed the congregations in the East following Joseph’s murder. Courtesy of Vicki Jo Hays

After adding his political talent to Joseph’s campaign, William I. Appleby calmed the congregations in the East following Joseph’s murder. Courtesy of Vicki Jo Hays

On that fateful day, Appleby was in Georgetown, Delaware, with his companion U. Clark.[3] Clark headed to a nearby town while Appleby spent the evening politicking for the prophet. At that exact time, a thousand miles to the west, a mob assassinated Joseph in Carthage, Illinois. It was not until 10 July that Appleby heard an initial report that the prophet was dead. “I could not credit the report . . . at first,” he wrote; “indeed I did not want to believe it, and almost hoped against hope.” After a night of troubling thoughts, Appleby found apostles Heber C. Kimball and Lyman Wight, along with other electioneers, in Wilmington, Delaware.

The apostles, on their way to Baltimore, told Appleby and his new companion, Joseph A. Stratton, that they had heard similar news. They all huddled at the home of local electioneer Ellis M. Sanders. Wight’s powerful sermon that night gave those gathered “some hopes that our brethren [were] yet alive.” Wight, Kimball, Appleby, and Stratton, in company with other electioneers as well as delegates, traveled from Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Delaware to Baltimore the following morning to hold the scheduled national convention. The morning papers printed a copy of a letter from Illinois governor Thomas Ford that “[convinced them] all that the prophet and patriarch [were] dead.” Stunned, the group “sat down and wept like children.”[4]

Appleby and Stratton separated themselves from the others, “feeling oppressed and mourning the loss of Joseph and Hyrum.” As Appleby later contemplated Zion, his thoughts rallied somewhat. He wrote, “[I have] a desire to humble myself, more than ever, with renewed zeal and determination to advance the work, or my diligence, before the Lord, and also to renew my covenant.” They rebaptized each other in the Atlantic Ocean and reconfirmed each other on the beach as a sign of their renewed dedication in the face of Joseph’s assassination. The next day the entire forlorn band returned to Wilmington. One more day saw Appleby at home in Recklesstown, New Jersey. Conflicted feelings still tearing at him, he penned: “Shedding tears of heartfelt grief and sorrow, before my Father in Heaven, for the loss of my beloved brethren, Joseph and Hyrum. . . . Indeed it was a blow, a loss, that all the church felt and lamented and mourned before heaven. . . . But if they have killed the prophet and patriarch, they cannot kill Mormonism or the church. Its course is onward.”

* * *

Electioneers throughout the nation likewise reacted with shock, anger, and sadness at the news that their revered prophet and presidential candidate had been assassinated. When the vast majority of electioneers eventually returned to Nauvoo or their hometowns, they were “determined by the aid of heaven’s king to preserve and sound the gospel drum, and if possible, with more energy.” Church leaders ordained Appleby a high priest for his tireless efforts during the campaign, assigning him to preside over the large Philadelphia Branch. Like Appleby, many church members came to see Joseph’s assassination as a religious rejection of the restored gospel and a political refutation of the prophet. As they judged it, the nation had rejected God’s will and had blood on its hands. Yet even with the demise of Joseph and the campaign, the hope of Zion and theodemocracy burned in the hearts of the electioneer cadre.[5]

Destruction of the Nauvoo Expositor Press

Prominent in the lead-up to Joseph’s assassination were the malicious actions of three sets of brothers: William and Wilson Law, Robert and Charles Foster, and Chauncey and Francis Higbee. All six had been Latter-day Saints and friends of Joseph. Plural marriage, economic competition, political differences, and reciprocal charges of sexual immorality and murder plots now divided them from Joseph, and they conspired to destroy him. William Law purchased a printing press from Whig politician Abraham Jonas. Jonas was just one of several such men whose involvement suggests a conspiracy wider than a local mob. On 10 May 1844 the dissenters published the prospectus of their aptly named Nauvoo Expositor.

The first and only issue of the Expositor ran on 7 June. The dissenters proclaimed Joseph a fallen prophet laden with moral, economic, and political corruption and a “specimen . . . of the most pernicious and diabolical character that ever stained the pages of the historian.”[6] Knowing the principles behind Joseph’s religious, economic, social, and political Zion, they objected to them and caricatured them. They painted Joseph as a “hellish fiend” who had to be put down.[7] The conspirators created a dangerous environment to ensure the prophet’s downfall—a perfect trap. If Joseph did nothing in response, the lies and distortions would incite the mobs that were already mustering, intent on destroying Nauvoo. The accusations would also tarnish Joseph’s campaign with damning publicity. If Joseph chose to hinder or destroy the press, the dissidents would have a legal pretext to have him arrested and taken from the safety of Nauvoo. In fact, conspirator Thomas Sharp, head of the Anti-Mormon Party and editor of the Warsaw Signal, wrote two weeks before the Expositor’s only run that “Joe Smith is not safe out of Nauvoo, and we would not be surprised to hear of his death by violent means in a short time.”[8]

In the end Joseph chose to destroy the Nauvoo Expositor press, unwittingly entering the conspiratorial trap. Members of the Nauvoo City Council had passed a libel law granting them authority to raze the press for being a “public nuisance.” Thus legally empowered, Joseph and his associates acted swiftly to prevent a repeat of the Missouri atrocities. They believed they had judicial precedent on their side, and they felt justified, having not exercised prior restraint against the Expositor’s first printing.

Still, what was so dangerous about the Expositor’s claims that invited such quick and decisive action? Accusations of promiscuous polygamy, economic autocracy, political control—such claims had dogged the church for a decade. This time the Expositor’s language made it clear that someone in the Council of Fifty was divulging its decisions to the dissidents, who in turn were publishing dangerous, distorted versions of them. According to Joseph’s revelation, the Council of Fifty was to protect Zion and prepare men to rule in the kingdom of God following the collapse of the world’s governments. As part of its establishment, the council confidentially made Joseph prophet, priest, and king over the house of Israel—not over the United States.

Contrarily, the Expositor declared the council a “secret society” formed for the purpose of exerting “political power and influence” and headed by Joseph “as king [and] law-giver,”[9] intent on seizing the US presidency in order to “distribute among his faithful supporters the office of governor in all the different states for the purpose, we presume, of more effectually consolidating the government.”[10] Joseph’s “Political Revelations” from his position of “self-constituted Monarch” created a “Union of Church and State” to “put down” “all governments.”[11] Such distorted declarations were a public relations nightmare for Joseph’s campaign. They described him as a conspiratorial, traitorous, egomaniacal, monarchal leader bent on usurping the government. With his most important council compromised, there seemed to be no end to the distortions and lies that could destroy Joseph, his campaign, his Zion, and ultimately his people.[12] A few electioneers were directly involved in the Expositor crisis. William W. Phelps, Stephen H. Perry, and Levi Richards were added to the city council to fill vacancies created by departed electioneers, and they voted for destroying the press. Stephen Markham, in his role as policeman, accompanied the city marshal to the Expositor office and assisted in the destruction of the press.

The dissenters filed a grievance at Carthage, the county seat. A constable arrested Joseph and members of the Nauvoo City Council on the charge of riot for having destroyed the printing press. Naturally, Nauvoo’s Municipal Court released the accused, and a friendly non–Latter-day Saint justice of the peace found them not guilty. These legal moves only served to fan the flames of hostility against the Saints. Thomas Sharp call to action was a flashpoint: “Citizens ARISE, ONE and ALL!!!—Can you stand by, and suffer such INFERNAL DEVILS!! to ROB men of their property and RIGHTS, without avenging them. We have no time for comment, every man will make his own. LET IT BE MADE WITH POWDER AND BALL!!!”[13]

The next day, committees of angry settlers throughout the county mobilized to drive the Saints from outlying areas into Nauvoo and cut off communication with the rest of the county, state, and nation. John Taylor remembered “that it was with the greatest difficulty that we could get our papers circulated; they were destroyed by postmasters and others, and scarcely ever arrived at the place of their destination.” Ironically, the very men who expressed outrage at the destruction of the Expositor now practiced their own form of suppression.[14] As a result of the deteriorating situation, Mayor Joseph Smith declared martial law in Nauvoo.

The Electioneer Cadre and Joseph’s Final Days

When Governor Ford arrived in Carthage, Illinois, on 21 June 1844, he demanded that Joseph face trial there. “We dare not come,” Joseph wrote Ford, “though your Excell[enc]y promises protection.” John C. Calhoun Jr., coincidentally in Nauvoo that day, had persuaded Joseph to go to Washington, DC, “to lay the facts before the general government.”[15] Under cover of darkness, Joseph, his brother Hyrum, and two trusted associates rowed across the Mississippi River to Iowa. Electioneer John M. Bernhisel, Joseph’s personal physician and political adviser, soon joined them. The next day three Nauvoo leaders, including electioneer Reynolds Cahoon of the Council of Fifty, brought a message from Emma to not flee. After consulting with Hyrum, Joseph reluctantly agreed to answer the charges in Carthage. Electioneer Jedediah M. Grant was dispatched to deliver the message to Governor Ford. “We shall be butchered,” Joseph flatly told the group. He bade farewell to friends and family in Nauvoo. Nine-year-old Charlotte Leabo, daughter of electioneer Peter Haws of the Council of Fifty, remembered that Joseph stopped at her house on the way to Carthage. He “kissed each of the children and bade them good-bye, telling them to be good, and that they would see him no more.”[16]

Joseph and the other defendants (several were electioneers) and their escort arrived around midnight at Carthage’s Hamilton Hotel, where the dissidents and other conspirators were lodging. The next day the defendants were released on bail, secured by bonds from electioneers Dan Jones, Edward Hunter, and John S. Fullmer. Before they could depart, Joseph and Hyrum were rearrested on a legally dubious charge of treason for placing Nauvoo under martial law. Clearly the conspirators were determined to keep the brothers in Carthage, on one pretense or another, to murder them. Members of the electioneer cadre remained involved in the developing situation until the last hours of Joseph and Hyrum Smith’s final two days. On 26 June, Stephen Markham and Dan Jones, who used hickory “rascal beaters” to defend their brethren from rouge militiamen the day before, tried to fix the broken latch on the jail’s bedroom door. John S. Reid filed several legal complaints, and John S. Fullmer smuggled his “single-barrel pocket pistol” into the jail, giving it to Joseph. The electioneers were doing all they could to protect the prophet.[17]

That evening, the Anti-Mormon Carthage Central Committee convened in the hotel. Visitors to the meeting included Governor Ford, Illinois Whig Central Committee member George T. M. Davis, and nearly two dozen men representing almost every state in the nation. Allegedly they had responded to a “secret national call” to join forces against the Saints. This star-chamber council met to decide the fates of the Smith brothers. “Delegates from the eastern states” explained that Joseph’s Views, proclaimed by the electioneers, “were widely circulated and took like wildfire.” They determined that if Joseph “did not get into the presidential chair this election, he would be sure to next.” Whether this was hyperbole to solidify support for their assassination plans or an accurate reflection of deeply held conspiratorial fears, the council acted. They would wait for the governor to leave for Nauvoo the next day, and then they would summarily execute the Smiths.[18]

When Markham unintentionally approached the meeting, an alarm was sounded and in the scramble Dr. Wall Southwick, a mysterious land dealer from Texas, grabbed the minutes. Southwick showed Markham the notebook, revealed the meeting’s purpose, and promised to give him a copy of the proceedings. Meanwhile, Davis, who attended the meeting, directed a letter to his editor titled “June 26, 1844, 8 p.m., Carthage,” thereby beginning a propaganda campaign to justify the Smiths’ murders. Davis reported that “before they [the militias] disband, a desperate effort will made to visit summary punishment upon the two Smiths.” “You need not be surprised,” he continued, “to hear, at any time, of the destruction of the two Smiths by the populace.”[19] After hearing Southwick’s report, Markham informed Joseph of the plot. “Be not afraid” was the prophet’s only response.[20] That night a gunshot awakened the prisoners. Joseph paced the floor before lying back down. Turning to electioneer Dan Jones, he whispered, “Are you afraid to die?” Jones replied, “Has that time come, think you? Engaged in such a cause I do not think that death would have many terrors.”[21] Joseph replied that Jones would yet see his native Wales as a missionary.

Electioneers John S. Fullmer and Cyrus H. Wheelock smuggled these pistols into Carthage Jail. Joseph used the “pepperbox” (bottom) in defense during the assassination. Courtesy of Church History Museum. © IRI. Used by permission.

Electioneers John S. Fullmer and Cyrus H. Wheelock smuggled these pistols into Carthage Jail. Joseph used the “pepperbox” (bottom) in defense during the assassination. Courtesy of Church History Museum. © IRI. Used by permission.

On the morning of 27 July, Governor Ford broke his promise to take Joseph with him to Nauvoo but kept his promise to demobilize the troops at Carthage. One company remained to “guard” the jail. Some of the disbanded troops, however, went only a short distance out of town before returning to “kill old Joe and Hyrum.”[22] Cyrus H. Wheelock, overhearing their communications, visited the jail and smuggled in a six-shooter pepperbox pistol. “Would any of you like to have this?” he asked. Joseph took it. Then the prophet gave John S. Fullmer’s pistol to Hyrum, saying, “You may have use for this.” “I hate to use such things, or to see them used,” Hyrum replied. “So do I,” remarked Joseph, “but we may have to, to defend ourselves.” Hyrum took the pistol.[23]

With Joseph trapped in jail and his enemies openly plotting his murder, the election campaign would soon be a historical footnote. As for the Council of Fifty, now exposed and caricatured, its members believed they were ready to perform their roles in establishing the political kingdom of God. However, this was not the season they had hopefully supposed. Joseph lamented, “We have the revelation of Jesus, and the knowledge within us is sufficient to organize a righteous government upon the earth, and to give universal peace to all mankind if they would receive it; but we lack the physical strength, as did our Savior when a child, to defend our principles.” Wheelock and Fullmer then left with “heavy heart[s]” for Nauvoo around 11:00 a.m. The guards later refused Dan Jones reentry to the jail.[24]

Stephen Markham, the last electioneer to be with the prisoners, sat next to Joseph. “I wish you would tell me how this fuss is going to come out as you have at other times beforehand,” he implored. “Bro[ther] Markham,” Joseph replied, “the Lord placed me to govern this kingdom on the earth, but the people [have] taken away from me the [reins] of government.”[25] In Joseph’s mind the campaign was over. He had believed that with divine help he would be elected. But now it was clear that the United States had fully rejected him and in so doing rejected God and political salvation.

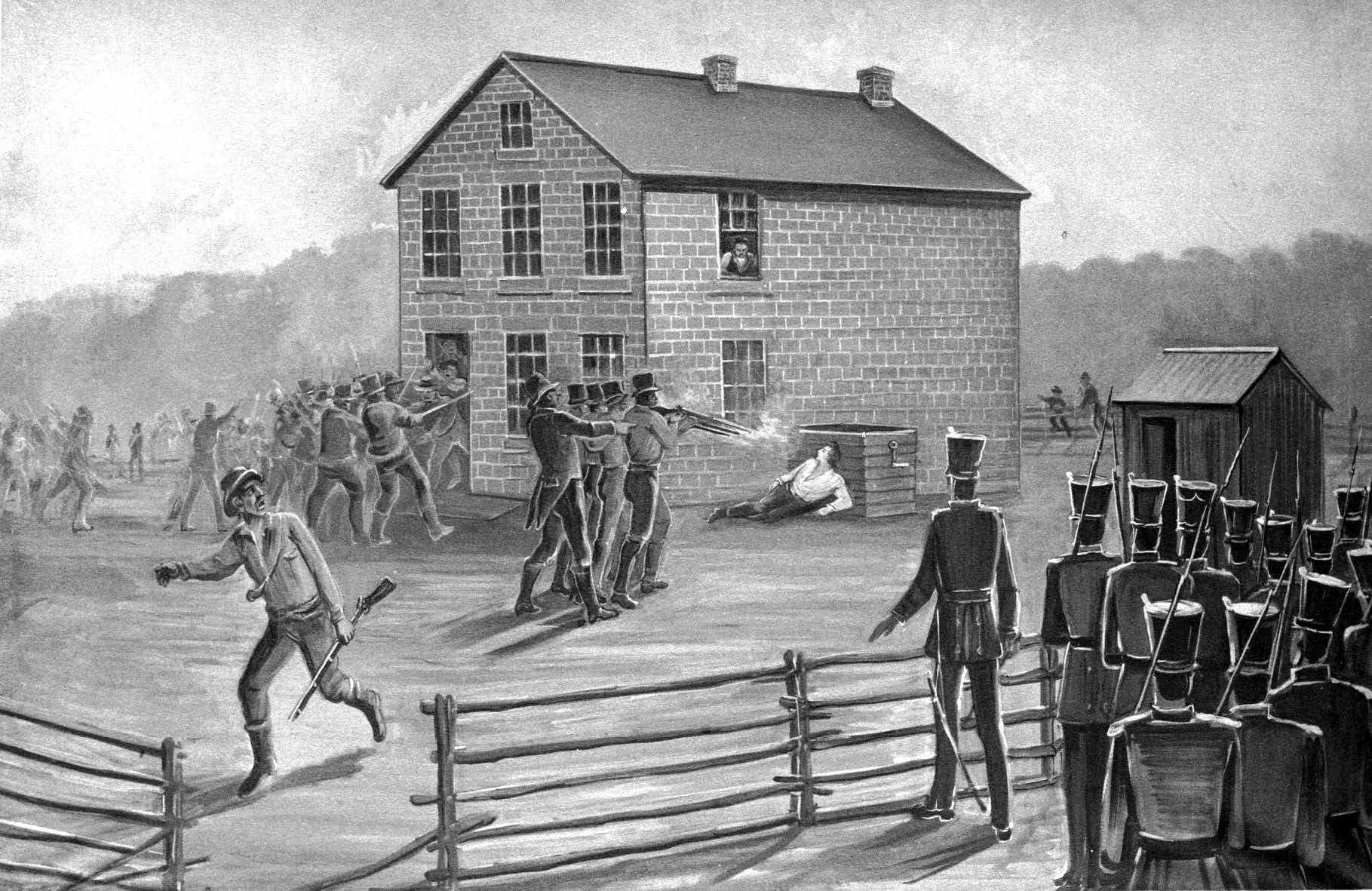

While returning from an errand, Markham was intercepted by militiamen and forced back to Nauvoo. The occupants of the jail now numbered only four. As the afternoon progressed, they became anxious. Hyrum read to pass the time and Willard Richards penned correspondence. John Taylor, an accomplished tenor, sang Joseph’s new favorite hymn, “A Poor Wayfaring Man of Grief.” Around 4:00 p.m. the guards were changed. An hour later the prisoners heard a cry of “Surrender!” and what turned out to be the prearranged firing of blank musket charges by the guards. Richards glanced out the open window and noticed some one hundred men, their faces blackened with wet gunpowder. Assailants rushed up the stairs. The first met Joseph’s fist. The small landing leading to the bedroom quickly became crowded. The other prisoners shed their coats and entered the fray. Gunfire erupted from inside and outside the jail. The prisoners pushed desperately on the door to keep the mob out. Hyrum reached for his pistol. A shot pierced the door and struck him just left of the nose. Falling to the ground, he exclaimed, “I am a dead man!” Rushing to his fallen brother, Joseph exclaimed, “Oh my dear brother Hyrum!”

There was no time for mourning. Joseph could hear the door giving way. Soon gunfire flashes and smoke filled the room. Joseph turned, approached the partially open door, and fired the six-shot pepperbox. Three rounds misfired. Three struck, wounding separate men. The mob momentarily paused but then renewed the assault. Richards and Taylor parried the muskets sticking through the crack of the door. “That’s right, Brother Taylor, parry them off as well as you can” were the last words Taylor heard Joseph speak. The force of the gunmen sprang the door open. Three-hundred-pound Richards became trapped behind it. Taylor ran to escape through the window, but a ball fired from outside knocked him back into the room. His impact on the windowsill crushed his pocket watch, forever recording the time of the murders—5:16 p.m. and 26 seconds. He rolled under the room’s bed. Three more balls struck him. Passing in and out of consciousness, Taylor would nonetheless survive.

Joseph’s assassination marked him as the first presidential candidate in US history to be assassinated. Artist unknown. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Joseph’s assassination marked him as the first presidential candidate in US history to be assassinated. Artist unknown. Courtesy of Church History Library.

More muskets fired into the room. Joseph ran to the window and hung awkwardly on the ledge. With uplifted hands he cried, “Oh Lord my God!” Falling, or perhaps leaping, he landed heavily on his side on the ground fifteen feet below.[26] When someone shouted, “He’s jumped the window!” the murderers stampeded down the stairs. Outside, someone dragged the semiconscious Joseph up against a well curb.[27] Levi Williams, the leader of the assault, ordered, “Shoot the God damn scoundrel!”[28] Four riflemen fired. Each ball found its mark. Joseph Smith, prophet and presidential candidate, was dead.[29] The assailants dispersed quickly. Willard Richards and others cared for the wounded John Taylor and prepared crude coffins for the corpses. Richards penned a quick note to Nauvoo in the middle of the night, confirming the deaths and counseling the Saints not to retaliate.

Electioneer Reactions to the Assassination

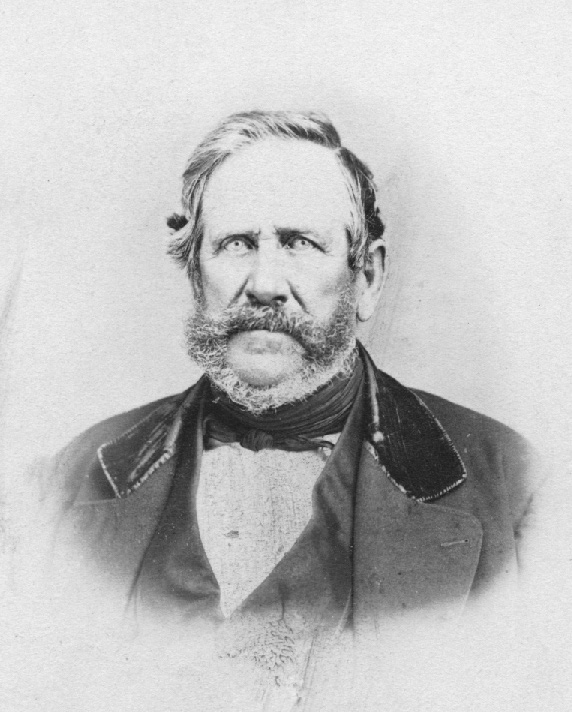

Some electioneers were working in and around Nauvoo on the day of Joseph’s assassination. Edward Hunter had gone to Springfield to intercept Governor Ford and “allay the excitement and hostility . . . in the direction of Nauvoo and the ‘Mormons.’” Hunter discovered that the governor was already in Carthage. As he returned to Nauvoo, “the whole country was in an uproar,” and he and his traveling companions heard constant threats “that the ‘Mormon’ leaders would never get away alive.” Hunter reached Nauvoo in the late afternoon of 27 June, the same time as the murders.

The next day, the Smith brothers’ bodies returned to a grief-stricken Nauvoo. Hunter recorded, “A massive crowd of mourners [was] there, lamenting the great loss of our prophet and patriarch.” He recalled, “The scene was enough to almost melt the soul of man.” Hunter helped carry Joseph’s body into the Mansion House, “where thousands of people, bathed in tears, passed in procession, two abreast, to view their mangled remains.” [30] Lyman O. Littlefield recorded that he and his wife “had the mournful privilege of looking one sad and brief adieu upon the noble forms of those men of God.” He later wrote: “Although forty-four years have since passed away, the powers of memory seldom go back and review the scene—though in gleams of momentary fleetness—without sensations of pain.”[31]

Edward Hunter saw the dead

Edward Hunter saw the dead

bodies of Joseph and Hyrum in

Nauvoo—a “scene . . . enough to

almost melt the soul of man.” 1867 photo by Edward Martin courtesy

of Church History Library

Levi W. Hancock took his ten-year-old son Mosiah to the Mansion House and told him “to place one hand on Joseph’s breast and to raise [his] other arm and swear with hand uplifted that [he] would never make a compromise with any of the sons of hell.” Mosiah recorded that he “took [the vow] with a determination to fulfill to the very letter.”[32] Christiana Riser, the wife of George C. Riser, who was electioneering in Ohio, “looked upon the faces of Joseph and Hyrum in death [and] . . . vowed that if she had another son she would name him after the prophet and his brother.” Two years later she gave birth to Joseph Hyrum Riser, one of more than two hundred children of electioneers named for Joseph or Hyrum.[33]

The next day William W. Phelps, Joseph’s longtime friend, Council of Fifty member, and electioneer gave the funeral sermon. Addressing ten thousand Saints, he proclaimed, “Two of the greatest and best men who have lived on the earth since . . . the Savior have fallen victims to the popular will of mobocracy in this boasted ‘Asylum of the oppressed.’” Although the prophet was dead, the priesthood restored through him “remain[ed] unharmed” and other leaders would step into the “‘shoes’ of the ‘prophet, priest and king’ of Israel . . . with the same power, the same God, and the same spirit that caused Joseph to move the cause of Zion with mighty power.” Hunter remembered, “Their death was hard to bear. Our hope was almost gone.”[34]

A few days later Jedediah M. Grant married his sweetheart Caroline Van Dyke. That evening he left on a mission to call the apostles and his fellow electioneers home to Nauvoo. He would accomplish this primarily by dispersing correspondence from Philadelphia (where he was to once again preside over the branch) and giving direction to the eastern Saints.

Milo Andrus and John Loveless were the only missionaries serving away from Nauvoo who returned in time to attend the funeral. They were electioneering nearby when, as Loveless recorded, “we heard of the assassination of the Prophet Joseph and his brother Hyrum . . . [and] went home . . . quickly.”[35] Andrus also visited Carthage Jail “and saw the floor stained with the best blood of the present generation.”[36] Having returned to Nauvoo, several other electioneers made the pilgrimage to Carthage to pay homage. Joseph Curtis recorded his solemn feelings at seeing blood stains on the walls.[37] Charles C. Rich “visited the jail at Carthage to see . . . where the prophet and patriarch [were] mart[y]red.” A mixture of anger, reverence, and determination left with him.[38]

Some distant electioneers who heard of Joseph’s assassination in newspaper accounts initially discounted them. In an age of horse and buggy, confirmation of this devastating news through trusted channels could take weeks, leaving the electioneers in growing emotional turmoil as the days passed. Norton Jacob and most of the Michigan electioneers were “attend[ing] a state convention . . . for the purpose of nominating presidential electors.” On the last day, 5 July 1844, newspapers reporting Joseph’s death appeared. “We did not believe the story,” Jacob recorded in his journal, “and proceeded to nominate our electors.” But while heading to his next assignment with Zebedee Coltrin, Jacob received a letter from Charles C. Rich confirming the assassination. Jacob soon met Moses Smith, who was “completely discomfited by the news of the prophet’s death and . . . would preach very little afterwards.”[39]

Joseph Stratton learned of Joseph’s death on 7 July at the train station in Wilmington, Delaware. “I did not credit the report,” he wrote, “although it created a very singular sensation; it seemed to run through me like an electric shock.” The next day he read about the assassination in the Philadelphia papers. When he encountered Elijah F. Sheets and three other electioneers on 10 June, the meeting was “quite refreshing to both in this time of excitement.” As they discussed the news, “some believed the report was true; others did not.” Stratton journeyed to Philadelphia the next week, where Jedediah M. Grant gave the gathered Saints “all the particulars” about the assassination. [40]

Abraham O. Smoot first heard reports of the murders on 8 July. He and his colleagues had “heavy burthens of mind from the alarming story.” Smoot wrote, “Awful forebodings seared my mind which I labored to conceal from my brethren and friends . . . by alleging that I had no right to believe the reports, as many such reports had proved too false in days past concerning him.” Two days later his “mind [was] still like the troubled sea that casteth up mire and dirt from the whisperings of the Spirit of the probability of the death of Joseph and Hyrum.” On 12 July he received the Nauvoo Neighbor, which was “dressed in deep mourning,” and learned that the “awful tragedy had [in fact] been committed.” Shaken, Smoot penned, “Great God, endow me with Christian fortitude, for all my forebodings and fears are more than realized.”[41]

En route to their assignment in Vermont, James Burgess and Alfred Cordon read in the Syracuse, New York, papers that Joseph and Hyrum had been killed. In Dover, Vermont, nine days later, they continued preaching and electioneering, believing the reports inaccurate. On 26 July they received a copy of the Nauvoo Neighbor that “gave an account of them bringing their dead bodies into the City of Nauvoo and the scene which took place, which would be melting for the heart of any human being having read it,” recorded Burgess. “There must be some truth in the matter. It weighed our spirits down with grief to think that two men of God . . . [should] so soon fall by the hands of wicked men; we little thought of it when we left Nauvoo.” The idea that the Smiths were dead “pained our very souls,” Burgess added.[42]

A small number of electioneers received comfort in what they described as revelatory visions or dreams. George Miller recorded a dream from the morning of June 28, just twelve hours after the assassination. He later remembered that as he lay in bed, “suddenly Joseph Smith appeared to me, saying, ‘God bless you, Brother Miller.’” Joseph told Miller that he and his brother Hyrum had been killed by a mob at Carthage after being “delivered up by the brethren as a lamb for the slaughter.” “You ought not to have left me,” Joseph declared. “If you had stayed with me I should not have been given up.” Miller countered, “But you sent me.” The prophet replied, “I know I did, but you ought not to have gone,” and then approaching Miller as if to embrace him, Joseph said, “God bless you forever and ever.” As the dream ended, Miller found himself standing in the middle of the room, arms extended as if returning an embrace. Miller’s companion, Thomas Edwards, now awakened, called out, “What is the matter?” Miller said nothing.

During their morning walk, Miller told Edwards of his vision, declaring he was sure it was true and he would be returning to Nauvoo. Edwards responded that Miller “preached too much and [his] mind was somewhat deranged” and that they should fulfill their appointments. Miller agreed, but after their last engagement they headed home. Passing a tavern, they read of the Smiths’ deaths. “Brother Edwards, being an excitable man, was wholly unmanned,” Miller wrote, “and insisted on an immediate separation, as traveling together might endanger our lives, and broke off from me . . . , and I did not see . . . him until I saw him in Nauvoo, four weeks afterwards.”[43]

John D. Lee in Kentucky learned of Joseph’s death from newspaper accounts on 5 July. A few days later he recorded a dream-vision. A heavenly messenger appeared to him and showed him “the martyrdom of the prophet and patriarch” and “bid [Lee’s] fears depart,” for his “labors [were] accepted.” The angel explained that Christ’s original Twelve and Seventy had felt all was lost when he was “taken and crucified instead of being crown[ed] king (temporal) of that nation, as they fondly expected.” “Just so it is with you,” the messenger explained. “Instead of electing your leader the chief magistrate of this nation, they have martyred him in prison, which has hasten[ed] his exaltation to the executive chair over this generation.” The angel instructed Lee to “return home in peace and there [a]wait [his] endowment from on high, as did the disciples at Jerusalem.”[44]

William R. R. Stowell documented a dream just days after returning to Nauvoo. In it he walked into Joseph’s mansion and found him lying in a bed. They greeted each other and then traveled to Stowell’s home. After some conversation the prophet wished to go home, but Stowell pleaded for a blessing first. Joseph laid his hands on Stowell and “pronounced many choice blessings . . . [and] declared that the blessings of God should be upon [his] efforts in rolling the latter-day work on.” The blessing ended with an emphatic “and you shall be blessed.” For Stowell, the dream swept away “the darkness and despondency that had brooded over him,” and with “his mind . . . at rest . . . his usual courage and energy returned.”[45]

William I. Appleby experienced a vision of Joseph more than a year after the martyrdom. Joseph took Appleby into another room and the two sat in chairs face-to-face. “He commenced instructing and counseling me, with tears rolling down his cheeks, in things appertaining to the cause I am engaged in,” wrote Appleby, “which if I hearken to will be to my eternal welfare.” He remembered that Joseph “counseled me ‘to never find fault or lift my hand against the servants of God.’”[46]

At the exact time of Joseph’s assassination, James Holt received a revelation of the deed while preaching a sermon five hundred miles away. Image courtesy of Linda Holt.

At the exact time of Joseph’s assassination, James Holt received a revelation of the deed while preaching a sermon five hundred miles away. Image courtesy of Linda Holt.

Perhaps most amazing was the experience of James Holt. He and companion Jackson Smith preached and politicked around Holt’s family home in Wilson County, Tennessee. They signed a contract in the nearby town of Lebanon for the printing of five hundred copies of Views, to be ready, ironically, on 27 June. When Holt returned on that day, his order was not ready. The editor apologized, explaining that “so many people had borrowed the copy to read it that he had lost track of it.” When it was discovered that the owner of the pamphlet was in town, some of the townspeople asked Holt to preach and politic. They procured him the courthouse, rang the town bell, and soon the building was overflowing with people anxious to hear the “Mormon” who had grown up nearby.

Holt began his sermon two hours before sunset, around 5:15 p.m.—the exact time of the attack on Carthage Jail, five hundred miles to the northwest. Holt later wrote that “the Spirit of the Lord was on [him]” as he taught the first principles of the restored gospel and the persecution of the Saints in a so-called Christian and free land. He preached for two hours, much longer than he had anticipated. He recorded, “In the winding up of my sermon, I had the spirit of revelation come upon me, and I told them that the enemies of the church had taken the prophet of God this day and put him to death, as they had all the prophets of God in all dispensations of the world.” “Now,” he concluded, “you may have this as a testimony of the gospel, for that is true Mormonism.” Stunned at his own words, Holt looked out over the crowd: “No one had anything to say, but all seemed struck with amazement and their eyes filled with tears.”

Holt returned to his father’s house. He shared his experience with his companion Jackson Smith and also with his father. Neither believed him. Holt responded, “The Spirit of God [can] reveal anything to man that [is] going on in any part of the world,” adding, “I kn[o]w that God . . . revealed the truth to me and that I should start for home right away.” Skeptical, Smith refused to return to Nauvoo with him.

On his way home, Holt felt drawn to a man on a porch reading a paper. He approached and asked for water as an excuse to talk. After a few swallows, Holt said, “You seem to be quite interested in what you are reading. Is it anything very special?” The man said it “concern[ed] the death of the Mormon prophets.” Holt coyly asked where those prophets lived. The man replied, “Nauvoo, and [they] were taken to Carthage and killed.” He remarked that the article carried the signature of Governor Ford, so it must be true. Holt thanked the man for the water and continued his journey, the stranger never knowing he had entertained one of Joseph’s electioneers. Holt remembered, “This confirmed my impression of the expression I had by the Spirit at Lebanon, for I now had no cause to doubt if I had felt so inspired, but I had not doubted since it was first revealed to me.” The series of events, “instead of . . . weakening my faith, . . . strengthened it,” Holt penned, “for I knew that Joseph Smith was a prophet of God.”[47]

However, most of the electioneer cadre had no premonition of Joseph’s death. The sudden news of his assassination shocked and dismayed these men who had sacrificed to strike out across the nation in his name. Alfred B. Lambson and John Jones Jr. had the martyrs’ deaths confirmed upon meeting apostle George A. Smith and other electioneers in Elkhart, Indiana, on 14 July. After hearing David Fullmer preach, the men’s hearts “were filled with grief and [they] . . . spent the day in mourning.” Indeed, “deep sorrow filled all the Saints’ hearts, and many gave themselves up to weeping,” recorded George A. Smith. “We all felt much the worse for want of sleep.”[48] Crandell Dunn wrote, “The Spirit of God seemed to carry the testimony to all hearts, which caused the silent tear to trickle down the cheeks of [the] brethren.”[49]

A twenty-one-year-old Virginian and recent convert, Henry G. Boyle had never met Joseph. On 16 July, while traveling to a conference in Tazewell County, Virginia, he heard the news of Joseph’s murder. “I felt depressed in my feeling,” Boyle remembered. “I was but a boy and had but little experience. I asked the Lord to strengthen me with his Spirit and enable me to do honor to his cause; my prayer was answered, for I had put my whole trust in him.”[50] Nancy and Moses Tracy were returning to Ellisburg, New York, from preaching and electioneering to Nancy’s family when they “received the heartrending news that [their] prophet was slain in Carthage jail.” “We were horror stricken,” Nancy recalled. “My husband sobbed aloud, ‘Is it true? Can it be true, when so short a time ago he set us apart to fill this mission and was all right?’”[51]

Irish convert James H. Flanigan, after receiving the news of “the death of our beloved prophet and patriarch, Joseph and Hyrum Smith,” recorded that it “shocked the Saints, shocked this realm, and shocked the world.”[52] On 14 July Jacob Hamblin felt “very melancholy and [his] spirit [was] depressed” when he received a letter with the dreadful news. “My feelings I will not attempt to describe,” he penned. “For a moment, all was lost.” While walking to his next appointment, he sensed he could not preach and “felt under no obligation as they had killed the men God had sent to restore all things.” Hamblin “could not refrain from weeping, and turned aside to give vent to [his] feelings.” As he did so, he encountered a group of men who ridiculed him saying, “I wonder what will become of Elder Hamblin’s Mormon president?” Upon hearing this, Hamblin recorded, “I felt that if I could be annihilated it would be [a] blessing to me.” The thought that Joseph was dead was more than he could endure. “It appeared to be the weight of a mountain upon me,” he remarked. “I thought it would crush me to death.”[53]

Those with the gift of language expressed themselves through poems. Joel H. Johnson dedicated a poem to Joseph. The final stanza defiantly declared:

Thy holy cause I will defend,

And all thy sorrows, joys and care,

Shall be my own, till life shall end,

With thee eternal lives to share.[54]

William I. Appleby’s poem praised Joseph’s devotion to the cause of Zion in his roles as priest and king:

And for these truths thy blood was shed, and laid thy body down;

But thou wilt rule a mighty host, and Wear a Martyr’s Crown.

Millions shall know thou art a King, thy power they shall dread;

For by [thy] Priesthood, thou was’t crown’d before thy blood was shed;

Thou’rt only pass’d behind the veil, to plead the cause above,

Of Mourning, bleeding Zion, which was, thy daily love.[55]

William W. Phelps wrote a poem later set to Scottish folk music. The new song became one of the church’s most enduring and endearing hymns. As placed in the 1845 hymnal, two verses capture the post-assassination feelings of the electioneers:

Praise to his mem’ry, he died as a martyr;

Honor’d and blest is his ever great name;

Long shall his blood, which was shed by assassins,

Stain Illinois,[56] while the earth lauds his fame.Sacrifice brings forth the blessings of heaven;

Earth must atone for the blood of that man!

Wake up the world for the conflict of justice,

Millions shall know “brother Joseph” again.[57]

Perhaps John D. Lee best captured the poignant feelings of the electioneer cadre regarding the loss of Joseph: “A friend more dear to us than all the riches and honors that could be conferred on us by a thousand such worlds as we now inhabit.”[58]

Many electioneers responded to the loss of Joseph and Hyrum with an increased desire to vigorously advance the work of Zion. William Stowell recorded, “While I felt to mourn deeply the loss of our noble leader, my faith was not in the least shaken in the doctrines and principles that the prophet had planted in the earth.” He continued, “The spirit of gathering with the Saints and sharing their fortunes, whatever they might be, was still upon me as I continued to labor diligently in preparing for the journey to Nauvoo.”[59] Stowell led a small group of Saints across the country in a wagon that defiantly advertised “Nauvoo” on its canvas cover.

Other electioneers responded to Joseph’s assassination with unmitigated fury. John Loveless was returning to Nauvoo on 28 June when he learned of Joseph’s death and had to endure the galling celebratory mood of church enemies.

About one hundred fifty miles below [Nauvoo], we met a boat coming down that gave us the news of the prophet’s death; a perfect shout was set up by the devils incarnate on our boat, who were on their way up to Nauvoo to fight the Mormons. Had I possessed the strength of Sampson, I would, like him, [have] sunk the whole mass in one gulf of oblivion and sent them to their congenial spirits, the howling devils of the infernal regions.[60]

Most electioneers, immediately and over time, saw the assassination as the rejection of Joseph and the restored gospel by a wicked nation. Amasa Lyman observed a Fourth of July celebration in Cincinnati, just a day after hearing of the murders. He wrote that the people made a “great preparation . . . to celebrate [the] birth of American liberty, which might better have been turned into its funeral.”[61] On 11 July in Rochester, New York, Franklin D. Richards wrote, “While the world exults in the supposed death of the prophet, they might better bemoan their own pending fate and that of our own happy country, in fulfillment of his predictions.”[62] William Hyde was furious that the nation had denied Joseph: “They have stained the earth with the blood of the man, or men, through whom God has organized his kingdom on the earth, which kingdom he has decreed shall stand forever. . . . And for that blood the nation will be obliged to atone.”[63]

The electioneers suspected a political motive behind Joseph’s assassination.[64] Chief among them was campaign manager, apostle, and wounded victim of the Carthage mob John Taylor. On 27 June 1854, exactly ten years after the martyrdom, Taylor spoke at the packed Tabernacle in Salt Lake City as the last survivor of that fateful day. He chronicled the enemies inside the church in 1844 and their machinations, including how a conspiring “political party” angry over “Mormon political power” induced local rabble to “destroy the Mormons” because of their religion. The influence of Joseph’s political foes was “the great cause of this animosity and trouble,” Taylor testified. “Strong political feeling existed against Joseph Smith, and [Taylor had] reason to believe that [Joseph’s] letters to Henry Clay were made use of by political parties opposed to Mr. Clay and were the means of that statesman’s defeat.”[65]

Nathan T. Porter remembered that Joseph’s enemies “began to be jealous of his success in a political as well as religious [point] of view.” They “began with renewed diligence to stir up more violent persecutions against him.” Latter-day Saint dissenters were used in the conspiracy to offer “false accusations and vindictive charges issuing out writs of indictment.” They, “like Judas, betrayed him into the hands of his enemies.”[66] Joseph L. Robinson recalled that “wicked rulers . . . became mad, also saying if we let this fellow (Joseph) alone he will surely take away our place and nation. We must dispose of him in some way. So they got up persecutions and sent officers to Nauvoo that the prophet might be stopped.”[67]

Lyman O. Littlefield published The Martyrs in 1888 to tell the story of the assassination to a new generation of Saints. He was privy to information from eyewitnesses as well as from the testimonies of the accused murderers at trial. His research revealed a politically motivated conspiracy. There existed “powerful influences and jealousies in the circle of some of the leading men at the capital of the nation” because of the “presidential canvass that was in progress,” Littlefield asserted. “There were good grounds for the belief that an understanding was had between them [national political figures] and the Governors of Missouri and Illinois, and from them down through some of the State and County officers, that Joseph was getting too much power and influence, and his career must come to a close before the end of the campaign.”[68]

Few electioneers would disagree with the conclusions of Lorenzo Snow, the first electioneer to leave Nauvoo to advocate for Joseph’s presidency, president of the campaign in Ohio, and future president of the church. After hearing of the assassination, Snow observed, “The details of that horrid transaction are sufficient to show that no protection can be expected by [Latter-day] Saints from the government.” To twist the knife, the residents of western Illinois were now demanding that the Saints leave the state. Snow indignantly penned:

Are we to be forever mobbed and murdered because we have a religion different from other people? . . . Does not the blood of liberty flow through my veins and the spirit of freedom burn in my bosom? Yes! Yes! . . . Then I ask this mobocratic government if it expects [that] my hand, my heart, and my tongue are going to be hushed in silence by their damnable and worse-than-savage deeds. I say no, no! For I have sworn before the Almighty God, the Maker of Heaven and Earth, that so long as the life pulses in this heart of mine, every power and faculty of my soul shall be employed in defending the cause of the oppressed the people of God, the Latter-day Saints.[69]

* * *

Though stunned, hurt, and dismayed, most of the electioneers remained faithful to their belief that Joseph Smith was the prophet of God. While opponents of the church were successful in killing Joseph and terminating his candidacy, they did not deter his cadre of electioneers. Many continued preaching, some until late 1845. Others strengthened and reassured outlying branches of the church, giving hope to shocked and beleaguered congregants. Returning to Nauvoo, they reunited with family and friends to mourn the loss of their beloved leaders. But there was work to do. “Joseph’s measures” of building Zion and establishing a theodemocracy remained unrealized. The temple required completion. Latter-day Saints needed to be gathered from distant nations. With expulsion from Nauvoo imminent, refuge had to be found outside the United States. Who would lead the Latter-day Saint faithful into the West to create Zion under theodemocratic protection?

Joseph’s electioneers were uniquely positioned and qualified for this unprecedented leadership challenge. They had begun their missions with high hopes of converting a nation, religiously and politically. Sacrificing much, they overcame privation, abuse, loneliness, and persecution to preach the restored gospel and advocate Joseph Smith for president. As they did, their hearts and minds became fixed on creating Joseph’s Zion—a commitment that not even his death diminished. The work of Zion had to continue. How that would occur and who would lead them was still unknown, but the former electioneers—now field-tested and galvanized by loss of their prophet and continuing threats—would surely do their part. As William I. Appleby wrote, “The blood of the Saints [has] flowed to test [Zion], and [the work of building up Zion] must continue to roll on until the kingdom of this world becomes the kingdom of our Lord and his Christ.”[70]

Notes

[1] Lee, Journal, 30.

[2] Appleby, Autobiography and Journal, 122–33; and Stratton, Diary, 6–8.

[3] U. Clark is a mystery. He’s first mentioned in journals on 10 June 1844 as being near Philadelphia. Appleby is the only one who hints at a first name, simply writing “U.” By the end of June, Clark vanishes from the journals as abruptly as he appeared. I searched everywhere in church records and national and state censuses looking for a Clark(e) with a first name starting with “U.” I found no one in or out of the church. An intriguing possibility is that U. Clark is none other than “Hugh” Clark, a Catholic alderman in Philadelphia and central figure in the May and July 1844 Philadelphia Bible Riots. After news of the riots reached Nauvoo, Willard Richards, in his role on the campaign’s Central Correspondence Committee, wrote to Clark. The letter, dated 24 May 1844, said in part, “The Mormons and the Catholics . . . [are] the only two who have suffered from the cruel hand of mobocracy for their religion under the name of foreigners—and to stay this growing evil and establish Jeffersonian Democracy! . . . Help us to elect this man [Joseph] and we will help you to secure those privileges which belong to you, and break every yoke.” Richards offered Clark a position on the Central Correspondence Committee, presumably as the Catholic liaison between the faiths. No record exists that Clark responded to this offer of political cooperation. However, the letter would have arrived in Philadelphia during the first week of June. The mysterious U. Clark appears a few days later in the journals of several electioneers as a campaign companion outside Philadelphia. He then disappears about the time that news of Joseph’s death reaches Philadelphia and the Bible Riots recommenced. The possibility is alluring but requires more corroboration.

[4] Stratton, Diary, 7.

[5] See Appleby, Autobiography and Journal, 125–33.

[6] “Preamble,” Nauvoo Expositor, 7 June 1844, 2.

[7] “Further Particulars from Nauvoo,” Warsaw Signal, 12 June 1844.

[8] Warsaw Signal, 29 May 1844.

[9] “Resolutions,” Nauvoo Expositor, 7 June 1844, 2. Joseph’s being made a “king” was so widely known that Governor Thomas Ford later labeled it as one of the reasons the mob killed Joseph. See Ford, Message of the Governor of the State of Illinois, in Relation to the Disturbances in Hancock County (Springfield, IL: Walter and Weber, 21 December 1844), 5.

[10] Sylvester Emmons, “The Expositor,” Nauvoo Expositor, 7 June 1844, 2. This was undoubtedly a caricature of the apostles’ February “moot congress” (see chapter 2).

[11] “Prospectus of the Nauvoo Expositor,” Nauvoo Expositor, 7 June 1844, 5; and Francis M. Higbee, “Citizens of Hancock County,” Nauvoo Expositor, 7 June 1844, 3.

[12] See, generally, Nauvoo Expositor, 7 June 1844; and Nauvoo Neighbor, 12 June 1844, 2.

[13] Thomas Sharp, “Extra. The Time Is Come!,” Warsaw Signal, 12 June 1844; original capitalization retained.

[14] Taylor, Witness to the Martyrdom, 29.

[15] Joseph Smith to Thomas Ford, 22 June 1844.

[16] Alvin Kinsley, “From over the Border,” Saints’ Herald, 13 January 1904, 41.

[17] John S. Fullmer to Wilford Woodruff, 18 October 1881.

[18] This meeting is best explained in Wicks and Foister, Junius and Joseph, 164–66.

[19] George T. M. Davis to John Bailhache, 26 June 1844, printed in Alton Telegraph, 6 July 1844.

[20] Stephen Markham to Wilford Woodruff, 20 June 1856.

[21] JSH, F-1:173 (26 June 1844).

[22] JSH, F-1:174.

[23] See “John Taylor Martyrdom Account,” p. 46, The Joseph Smith Papers, https://

See also History of the Church, 7:100; and JSH, F-1:176.

[24] JSH, F1:176–77.

[25] Markham to Wilford Woodruff, 20 June 1856.

[26] Sources and historians differ over whether Joseph fell or leaped out the window. Historians Wicks and Foister (Junius and Joseph, 178), Leonard (Nauvoo, 394–96), and Bushman (Rough Stone Rolling, 550), along with Willard Richards (“Two Minutes in Jail,” Nauvoo Neighbor, 24 July 1844), argue that he fell. Eyewitness William Daniels (see JSP, CFM:202n641) and William Clayton (ibid.) contend that Joseph leaped or sprang through the window.

[27] See JSP, CFM:201, 202n641.

[28] William Daniels, 4 July 1844 affidavit, as quoted in Wicks and Foister, Junius and Joseph, 178n75.

[29] The number of musket balls that hit Joseph while he was on the window ledge is unclear, but he was still alive when he struck the ground. The evidence that Joseph was dead before hitting the ground comes from Willard Richards, “Two Minutes in Jail” (see n. 26 above), wherein he writes, “He fell on his left side a dead man.” Most other sources and historians argue Joseph was still alive when he struck the ground. See note 27 above; Wicks and Foister, Junius and Joseph, 178n76; Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 550; and Leonard, Nauvoo, 397. For more on the evidence and debate surrounding Joseph’s death, see JSP, CFM:190–204; Wicks and Foister, Junius and Joseph, 176–80, 230–45; and Oaks and Hill, Carthage Conspiracy.

[30] “Bishop Edward Hunter,” Our Pioneer Heritage, 6:319–26.

[31] Littlefield, Reminiscences of Latter-day Saints, 162–63.

[32] Mosiah L. Hancock, Autobiography, 30.

[33] Riser, Reminiscences and Diary, 11.

[34] “Bishop Edward Hunter,” Our Pioneer Heritage, 6:319–26.

[35] Loveless, “Autobiographical Sketch,” 2.

[36] Andrus, Autobiography, 6.

[37] See Curtis, Reminiscences and Diary, 63.

[38] Rich, Journal, 1.

[39] Jacob, Reminiscence and Journal, 7.

[40] Stratton, Diary, 5–8.

[41] Smoot, “Day Book,” 7–9.

[42] See Burgess, Journal, 10–26 July 1844 (quotations are from 26 July, p. 64).

[43] George Miller, ““Correspondence,” Northern Islander, 6 September 1855, 4.

[44] Lee, Journal, 30.

[45] Little, “Biography of William Rufus Rogers Stowell,” 23–26.

[46] Appleby, Autobiography and Journal, 149.

[47] Holt, Autobiographical Sketch, 5–6.

[48] George A. Smith, “History,” 14–15 July 1844, 18.

[49] Crandell, “History and Travels,” 49.

[50] Boyle, Autobiography and Diary, 8–9.

[51] Tracy, Reminiscences and Diary, 29.

[52] Flanigan, Diaries, 17.

[53] Hamblin, Record of the Life of Jacob Hamblin, 103.

[54] Joel Hills Johnson, “Voice from the Mountains,” 3–4, 12–16.

[55] Appleby, Autobiography and Journal, 244. This poem may also be proof that Council of Fifty members shared Joseph’s coronation with some of the electioneers.

[56] Post-1919 hymnals changed “stain Illinois” to “plead unto heaven.”

[57] A Collection of Sacred Hymns, for the Church of the Latter Day Saints, sel. Charles A. Adams (Bellows Falls, VT: S. M. Blake, 1845), 148, 149. The poem by W. W. Phelps originally appeared in Times and Seasons, 1 August 1844, 607, under the title “Joseph Smith.” Post-1919 church hymnals changed “stain Illinois” to “plead unto heav’n.”

[58] Lee, Journal, 29.

[59] Little, “Biography of William Rufus Rogers Stowell,” 23.

[60] Loveless, “Autobiographical Sketch,” 2.

[61] Lyman, Journal, 4 July 1844, 13.

[62] Franklin D. Richards, Journal No. 2, 11–12 July 1844.

[63] Hyde, Journal, 59–60.

[64] Joseph’s assassination has traditionally been interpreted as frontier extralegal action fueled by hatred of Joseph’s religion, particularly plural marriage. This is partly correct but severely understates the role of politics, particularly the Joseph’s presidential campaign. Joseph was killed for his religion precisely because it included brazen politics in public and in private, the Council of Fifty, and plural marriage. But rumors of plural marriage had haunted Joseph for years and did not incite mobs. Most contemporary local and national criticisms of Joseph were about politics—particularly the theocratic nature of Nauvoo. Critics saw Joseph’s election campaign as an attempt to nationalize such a system. Saints of Joseph’s generation overwhelmingly believed the killings were political. His enemies, particularly those never affiliated with the church, had been talking politics all along and had organized against it—before the Nauvoo Expositor incident. Works such as Oaks and Hill’s Carthage Conspiracy, Baker’s Murder of the Mormon Prophet, and Wicks and Foister’s Junius and Joseph all catalog in extensive detail the conspiracy’s ties to politics. Both William Law and Governor Ford believed the beginning of Joseph’s demise to be his personal interjection in the August 1843 Congressional elections and his political policies—particularly the campaign—that followed.

[65] Carruth, “John Taylor’s June 27, 1854, Account of the Martyrdom,” 47–49; and Roberts, Rise and Fall of Nauvoo, 454. After Joseph’s letter to Clay was published in the Nauvoo newspapers in mid-May 1844, it was republished with delight by Democratic newspapers across the nation. In 1850, when electioneer John Bernhisel, acting as Deseret’s representative in Washington, DC, was introduced to Clay, the greeting was cold. Bernhisel wrote to Brigham that Clay was “still writhing under the infliction of a certain letter addressed to him by Pres. Joseph Smith in 1844.” See John Bernhisel to Brigham Young, 21 March 1850.

[66] Porter, Reminiscences, 125.

[67] Robinson, “History,” 47–48.

[68] Littlefield, Martyrs, 50–52.

[69] Lorenzo Snow, letter, 19 July 1844, in Snow, Journal, 185–87.

[70] Appleby, Autobiography and Journal, 92.