Sanctification and Justification Are Just and True

Gerald N. Lund

Gerald N. Lund, “Sanctification and Justification Are Just and True,” in Sperry Symposium Classics: The New Testament, ed. Frank F. Judd Jr. and Gaye Strathearn (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2006), 46–58

Elder Gerald N. Lund of the Seventy was serving as Area President of the Europe West Area when this was published.

For some reason, sanctification and justification intrigue and puzzle many Saints who sincerely seek to understand the principles and requirements of salvation. Even a cursory study of the scriptures quickly proves that these are important, indeed central, concepts to an understanding of the gospel of Jesus Christ. The terms sanctification and justification and their cognate words are used hundreds of times in the four standard works. However, as important as they are, nowhere does any scriptural writer attempt to formally define either concept. Thus, we are left to derive their meaning from how the terms are used in various contexts or from the effects which result from their application.

In some ways, an examination of the usage only adds to the puzzlement because, on the surface at least, the very scriptural record seems paradoxical, if not inconsistent. For example, a statement in the Pearl of Great Price seems very clear and straightforward. Adam was taught that “by the Spirit ye are justified, and by the blood ye are sanctified” (Moses 6:60). The blood, of course, refers to the blood of Christ offered as atonement for sin. Other scriptures refer to the idea that we are sanctified or cleansed or have sin remitted through the blood of Jesus. To wash our garments in the blood of the Lamb is a well-known scriptural phrase (see 1 Nephi 12:10; Alma 13:11). Moroni spoke of being sanctified by the shedding of the blood of Christ (see Moroni 10:33). These scriptures seem to clearly support the idea that sanctification comes by the blood of Christ. And yet in several places the scriptures just as plainly and clearly speak of sins being remitted and of sanctification coming through the influence of the Holy Ghost (see 2 Nephi 31:17; Alma 5:54; 3 Nephi 27:19–20; D&C 84:23). This seeming contradiction happens in almost the same breath when Alma speaks about the people of Melchizedek. He notes they were “sanctified and their garments were washed white through the blood of the Lamb. Now they . . . [were] sanctified by the Holy Ghost” (Alma 13:11–12; emphasis added). And to further confuse the issue, the Doctrine and Covenants mentions neither the blood nor the Spirit but speaks of sanctification as being accomplished by law (see D&C 88:18–35, especially 21, 34). And other places in the Doctrine and Covenants command the Saints to sanctify themselves (see D&C 43:11, 16; 88:68, 74; 133:4).

We find this same kind of multiplicity in the scriptural use of the word justification. As noted, Adam was taught that “by the Spirit ye are justified” (Moses 6:60; emphasis added). And yet again and again, the Apostle Paul teaches that we are justified by faith (see Romans 3:28; 5:1; Galatians 2:16; Acts 13:38–39). Still Paul agrees with the scripture in Moses and says we are justified by the Spirit (see 1 Corinthians 6:11). And yet Paul specifically states “justified by his blood” (Romans 5:9; emphasis added). Both Lehi and Paul are equally specific in saying that by the law no person can be justified (see 2 Nephi 2:5; Romans 3:20; Galatians 2:16). But again we see the seeming contradiction, for just a few verses before Paul emphatically states that “by the deeds of the law there shall no flesh be justified” (Romans 3:20; emphasis added). He just as emphatically states “for not the hearers of the law are just before God, but the doers of the law shall be justified” (Romans 2:13; emphasis added).

It is not difficult, therefore, to understand why so many scholars, including some Latter-day Saints, have approached the study of sanctification and justification as though it were some great mystery, some mystical process beyond the understanding of all but the most erudite or spiritually mature. It is the position of this paper that just the opposite is true. While the application of the two concepts into our lives may be a great challenge, it is my firm contention that the doctrine of sanctification and justification is profoundly plain and simple, so much so that a child of accountable age could easily understand it and the implication it has. In its simplicity, it answers the paradoxes and seeming inconsistencies previously described.

The primary purpose of this chapter is not to provide an exhaustive analysis of the doctrine, nor is it even to attempt a complete and definitive outline of the principles. Much, much more could and should be said about these two principles, but our purpose here will be a limited one: to provide some conceptual tools that help us better understand and apply sanctification and justification in our lives.

Definitions

As previously noted, one of the problems we face in thinking about sanctification and justification is that they are not specifically defined in the scriptures. Thus, we must study their usage in order to determine their meaning. Some of the clearest statements on the two doctrines are found in modern scripture, and they are extremely valuable. However, we can come closer to a true definition of the words when we study them in their biblical setting because there we can examine their original meaning in both Hebrew and Greek. This study can provide a basic foundation of understanding which influences our usage of the words in modern English.

Sanctification. Ask Latter-day Saints or even modern Christians what it means to sanctify something and they will almost always answer in terms of cleansing or purifying. This is not incorrect, but it does not embrace the original sense of the Hebrew root kadash, which means “to set apart or separate something or someone for the work of God.” The concept of purity or holiness flows out of this idea of separation because to be set apart for God requires worthiness and a separation from the common or normal worldly use of things. “Perhaps the English word sacred represents the idea more nearly than holy, which is the general rendering in the A.V. The terms sanctification and holiness are now used so frequently to represent moral and spiritual qualities, that they hardly convey to the reader the idea of position or relationship as existing between God and some person or thing consecrated to Him; yet this appears to be the real meaning of the word.”[1]

Kadash (and its cognate words) is applied in the Old Testament to places, from which we get a word related to sanctified; namely, sanctuary. The camp of Israel was called Kadesh Barnea, or “the Sanctuary of Barnea” (see Numbers 13:26; 32:8), and the ground surrounding the burning bush was called kodesh (see Exodus 3:5). The idea of sanctification as separation was also applied to days or times such as the Sabbath (see Genesis 2:3; Exodus 20:8, 11). And kadash could also be applied to persons (see Exodus 13:2; 28:41) or a whole group of people (see Deuteronomy 7:6).

The need for kadash, or sanctification, sprang from the separateness or holiness of God. As Girdlestone notes, “God Himself was regarded as holy, i.e., as a Being who from His nature, position, and attributes is to be set apart and revered as distinct from all others; and Israel was to separate itself from the world and the things of the world because God was thus separated; they were to be holy, for He was holy.”[2] Kadash, in its various forms in the Old Testament (and the Greek hagiadzo, which corresponds to kadash in New Testament usage), is translated variously as “hallowed,” “holy,” “holiness,” “purity,” “sanctification,” “sanctified,” “sanctify,” and “saint” (one who is set apart to God or one who is sanctified).

So while it is proper and correct to think of sanctification as a cleansing from impurity and the effects of sin, it is helpful to remember the idea of being set apart or separated from the world and all that is unclean or profane so we can establish a relationship with God, whose very nature and essence is that of holiness.

Justification. The English words just, justify, and justification are translations of the Hebrew root tsadak and various forms of the Greek word dikay. Originally, the Hebrew root signified stiffness or straightness, and out of that came its meaning of “conformance to law,” meaning, of course, the law of God.[3] Thus, tsadak is usually translated as “righteousness” or “justness.” One who has been put in a state of tsadak has been “justified” or is in a state of “justification.” This idea of being put right differs from the concept of innocence—that is, never having been guilty of violating the law. A different Hebrew word, nakah, is used for that. Girdlestone notes the difference between the two words:

Nakah . . . generally appears to signify proved innocence from specified charges, whether those charges are brought by God or man. The offences, if committed, were punishable; but when they have not been committed, if that innocence can be made clear, the person against whom the charge is made goes off free from blame and punishment. . . . Where Nakah is used, man is regarded as actually clear from a charge; where Tsadak is used, man is regarded as having obtained deliverance from condemnation, and as being thus entitled to a certain inheritance.[4]

The Greek is particularly interesting for our understanding of justification, since the root word is dikay, which means “law of justice.” Thus, to be righteous (dikaios) means “one is in conformance to law.” The verb form (dikaiooh) means “to render something as righteous, or as it ought to be.” “Righteousness” (dikaiosunay) is the state achieved when our lives are in harmony with law. Dikaiosunay is also translated in the New Testament as “justification.” In other words, to be righteous is to be justified and justification is to be made righteous. This accords with Elder Bruce R. McConkie’s definition of justification:

What then is the law of justification? It is simply this: “All covenants, contracts, bonds, obligations, oaths, vows, performances, connections, associations, or expectations” (D&C 132:7), in which men must abide to be saved and exalted, must be entered into and performed in righteousness so that the Holy Spirit can justify the candidate for salvation in what has been done (1 Nephi 16:2; Jacob 2:13–14; Alma 41:15; D&C 98; 132:1, 62). An act that is justified by the Spirit is one that is sealed by the Holy Spirit of Promise, or in other words, ratified and approved by the Holy Ghost. This law of justification is the provision the Lord has placed in the gospel to assure that no unrighteous performance will be binding on earth and in heaven, and that no person will add to his position or glory in the hereafter by gaining an unearned blessing.[5]

The Holy Spirit can only approve and ratify that which conforms to God’s law.

Thus, we can see that as we use the terms today, sanctification and justification are closely related and are in some ways synonymous. Sanctification is to be holy or pure; justification is to be righteous. Indeed, so closely are the two interrelated and interdependent that it is preferable to speak of the doctrine of sanctification and justification instead of the doctrines. Both are inherently related to God’s own nature, and both involve relationship to Him. That latter concept is especially important. If we are not pure (sanctified) or if we are not righteous (justified), we cannot have a full and complete relationship with God. Thus, the natural man is an enemy to God (see Mosiah 3:19).

The Dilemma—Our Need for Justification

To understand the need for sanctification and justification, we must first understand the dilemma that mankind faces. This is fundamental doctrine related to the Atonement and is familiar to most readers, but it merits a quick review.

Because of His absolute holiness (separateness from all unholy things) and His perfect righteousness (adherence to the laws of godliness), God requires that any who dwell with Him meet these same standards. No unclean thing can dwell in His presence, for He is a Man of Holiness (see Moses 6:57). Or to use the terminology under discussion, to dwell with God we must be perfectly righteous (in an ultimate or perfect state of justification), and we must also be perfectly holy and pure (in an ultimate state of sanctification).

But as soon as we become accountable, we transgress the law and become carnal, sensual, and devilish, or what the scriptures call the natural man (see Mosiah 3:19; Alma 42:10; D&C 20:19–20). Thus, a tremendous breach in our relationship to God is set up.

|

Fallen Man |

God |

| 1. Carnal | 1. Perfectly holy |

| 2. Sensual | 2. Perfectly righteous |

| 3. Devilish | |

| 4. Enemy to God |

This is true of all men since “all have sinned and come short of the glory of God” (Romans 3:23).

Theoretically, we can be justified in one of two ways: we can keep the law perfectly (be proven right), or we can have the demands of the law satisfied (be declared or made right). In almost identical wording, both Paul and Lehi taught that by the law no flesh is justified (see Romans 3:20; 2 Nephi 2:5). They were speaking in the ultimate sense of justification, and that is easily understood. Not one of us keeps the laws of God perfectly; therefore we cannot be justified (made perfectly righteous) by our own works alone. Of all men, only Christ lived a perfect life, or, to put it in Lehi’s terminology, only Christ was justified by His works. The classic tragedy of the Pharisees was that they sought to justify themselves by their works. This explains their obsessive concern about the minute requirements of the law.

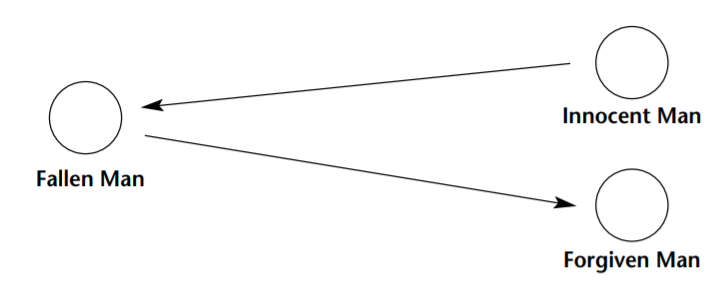

Repentance is not a solution to this dilemma (remembering that for the moment we are leaving the Atonement out of this). Repentance alone cannot restore our broken relationship with God. In an ultimate sense, repentance is not forward progress but only a return to the original point of departure. This could be diagrammed as follows:

To put this another way, when we repent of sin we are only doing what we should have been doing all along. So repentance alone cannot justify a person. Something else is required.

Once a law has been violated, some kind of punishment must be exacted or else justice (tzadak) will still have claim on the person. However, once payment is made, justice is satisfied, and this payment can be made either by the individual or by another person. If an individual is cited for violation of a traffic law, the court can be satisfied in one of two ways. The person can prove his or her innocence (justice has no claim because there was no violation), or a fine can be paid. The court does not care whether the money for the fine comes directly from the individual, from the person’s father, or from some other source. As long as the fine is paid in the person’s behalf, the law is satisfied.

So it is with justification for sin. Since we all violate the law, justice will not declare any one of us innocent by virtue of our behavior (justification by works). Suffering is the price required for violation of law (see D&C 19:15–19), and in the Garden of Gethsemane Jesus suffered for all the sins of the world. Therefore, if He chooses, Jesus can pay the price required for us. Justice, which cares only that payment is made, is satisfied. This explains why Paul could say that we are justified by the blood of Christ (see Romans 5:9). Christ’s atoning sacrifice made it possible for us to be declared righteous (justified). Therefore, as the Doctrine and Covenants states, justification is through the grace of Jesus Christ (see D&C 20:30).

Our Dilemma—The Need for Sanctification

Satisfaction of justice does not fully solve our relationship problem with God for, as we have seen, not only is His nature in perfect harmony with law (tzadak, or righteousness) but He is also perfectly holy and clean (kadash, or separated from all uncleanness). If we never violated the law, we would be both holy and righteous. But no one except Jesus Christ has successfully accomplished this. Violation of law makes us both unrighteous and unclean, or not holy. (In the Hebrew sense of kadash, we are no longer separated from the world and therefore are not holy or set apart for God’s purposes.) If the demands of justice are met (if we are justified), we come back into a state of righteousness, in the sense of conformance to law. But this does not make us holy—it only makes us righteous. A rough analogy is that of a felon who goes to prison for his crime. When he is released, he has fully met the demands of the law (he is justified), but he still has the taint of being an ex-convict. He somehow must reestablish the status (or relationship) he had before his crime.

So it is with sin. Justification, being made right with God, is not sufficient. We must also be separated again from the uncleanness that resulted from sin. In other words, not only must we be justified, we must be sanctified—cleansed from the effects of sin so that we can be holy as God is. The scriptures clearly teach how the Atonement sanctifies us or cleanses us from the effects of sin. Thus, “by the blood [we] are sanctified” (Moses 6:60).

Separating sanctification and justification in this way may cause some people trouble because in our gospel understanding we tend to equate righteousness and holiness, while they are not technically the same. Righteousness (conformance to law) results in holiness (separateness or cleanness) only because the Atonement is operating, and the process of justification and sanctification takes place automatically when we meet the requirements of Christ. Perhaps this analogy will help. The price required for entry into God’s presence is perfection in keeping the law. When we violate the laws of God, we forfeit any legal claim we had on His kingdom. Justification restores that legal claim because to be just means to be righteous or to be in conformance to law. But our sin not only causes a loss of our legal claim to the kingdom, it makes us unclean (not separated, not holy, not sanctified). Since no unclean thing can dwell in God’s presence, even if we restore our legal right to the inheritance (justification), we must also be cleansed (sanctification) if we are to live with God.

The Solution—The Process of Sanctification and Justification

If we are to be like God—that is, perfectly holy and perfectly righteous (the ultimate sense of sanctification and justification)—we must inaugurate the process of sanctification and justification in our lives. However, there are two ways or senses in which the doctrine of sanctification and justification must operate for us. First, we must overcome the initial state of being a “natural man,” and then we must maintain that redeemed state. In other words, we must be made right and holy, but we must also then be kept right and holy. Let us go back to our diagram of the dilemma we face and illustrate this dualism of the doctrine.

| Fallen Man | Strait and narrow path > | God |

| 1. Carnal | 1. Perfectly holy | |

| 2. Sensual | 2. Perfectly righteous | |

| 3. Devilish | ||

| 4. Enemy to God |

To be reunited with God we must get on the strait and narrow path, and then we must stay on that path until the end (see 2 Nephi 31:17–21).

Getting on the path—being made right and holy. To get on the strait and narrow path, we must be made both holy and righteous; we require sanctification and justification. We must be brought into a state of conformity to law (righteousness), and we must be separated from the uncleanness of the world (become holy). Both of these are made possible because of the atoning sacrifice (the blood) of Christ, but the actual medium or means for both sanctification and justification is the Holy Ghost. His very influence burns out the effects of sin and purges out the unholiness that comes upon us when we sin. However, we can only do so because Jesus Christ met the demands of justice and made it possible for mercy and grace to operate in our behalf. This explains why the scriptures can speak of sanctification—and likewise justification—as being by blood in one case and by the Spirit in another.

The condition for the blood of Christ being applied in our behalf is that we achieve a certain level of personal obedience to Christ’s law, which involves faith, repentance, and baptism. Only then can the Holy Spirit make us right and make us holy.

Staying on the path—being kept right and holy. But the initial justification and sanctification is not enough. As the Lord warned, “There is a possibility that man may fall from grace and depart from the living God” (D&C 20:32). Or as Nephi asked, “After ye have gotten into this straight and narrow path, I would ask if all is done? I say unto you, Nay. . . . Ye must press forward with a steadfastness in Christ” (2 Nephi 31:19–20). We must continue in a state of justification (righteousness or conformance to law), which we can do because we have the Spirit to guide us in all we do, teaching us how to live perfectly (see D&C 11:12–14).

However, even with the help of the Holy Spirit we will not live a perfect life at first. We will continue to sin, though to a lesser and lesser degree until we achieve perfection. Thus, there is a continuing need for ongoing sanctification as well as justification. This seems to be what King Benjamin meant when he talked about “retaining a remission of your sins from day to day, that ye may walk guiltless before God” (Mosiah 4:26). Thus, we need to be sanctified from both former and continuing sins, and we need to be brought into conformance with law and be kept in conformity with it. This explains the dual nature of sanctification and justification. We need two things if we are ever to enter back into God’s presence: we must be made right and holy, and we must be kept right and holy.

Harmonizing the Scriptures

At the beginning of this chapter it was suggested that the primary purpose of this discussion was to provide some conceptual tools that would help a person understand the doctrine of sanctification and justification. With these tools acquired, let us now examine what appears to be contradictions or at least inconsistencies in the scriptural discussions of these two concepts. Knowing the basic meaning of the terms sanctification and justification and also knowing what role the atoning blood of Christ, combined with the Holy Spirit, plays in each quickly resolves these apparent problems.

Without the blood shed by Jesus Christ in His atoning sacrifice, there would be no hope for mankind; there would be no chance that anyone could either be made righteous or holy. Therefore, the scriptures correctly point out that both sanctification and justification are by the blood of Christ. He is the validating power that makes it all possible, and from Him come the principles which bring it about.

But the role of the Holy Ghost in applying the blood of Christ in our lives is direct and specific. It is His power and influence that actually purges out the dross, cleanses us from sin, and makes us holy. This is called the baptism of fire. Also, it is under His direction and promptings that one derives the power and knowledge to live righteously. So we can legitimately say that one is both sanctified and justified by the Spirit (see Moses 6:60; 2 Nephi 31:17; Alma 13:12; 3 Nephi 27:19–20; D&C 84:24).

Where the Doctrine and Covenants indicates that we are sanctified through and by law (see D&C 88:21, 34), it clearly specifies that the law is the law of Christ (see D&C 8:21). In other words, unless we are willing to conform to the law, including the conditions for having the Atonement applied in our behalf (such as faith, repentance, and baptism), we cannot be sanctified.

Paul’s seeming contradiction (see Romans 2:13; 3:20) is easily resolved in this light. Although we cannot be justified (in the ultimate sense of being perfectly righteous) by our own efforts, in the interim sense, only those who are willing to do as the law requires can ultimately be justified. Thus, only the doers of the law will be justified. This also explains the command to sanctify ourselves (see D&C 43:11, 16). It does not suggest that we can make ourselves holy but only suggests that we must initiate the process for ourselves.

This should also answer any questions about the salvation-by-grace-or-works debate that rages in the Christian world. None of us can live perfectly enough to return to God on our own merits. We cannot be perfectly righteous (we cannot be justified), and therefore we are not perfectly holy (we are not sanctified). Only through the grace of the Father and the Son was the power provided to reclaim us from this state. On the other hand, to suggest that one’s behavior (works) does not matter is a contradiction of terms, for justification (tzadak) means to be in conformance to law, and sanctification (kadash) means to be separated or set apart from sinful things. The Prophet Joseph Smith brought this more clearly to light when he corrected Romans 4:16 to read, “Therefore ye are justified of faith and works, through grace.” Moroni captured this interdependence between grace and works when he said:

Yea, come unto Christ, and be perfected in him, and deny yourselves of all ungodliness; and if ye shall deny yourselves of all ungodliness, and love God with all your might, mind and strength, then is his grace sufficient for you, that by his grace ye may be perfect in Christ; and if by the grace of God ye are perfect in Christ, ye can in nowise deny the power of God.

And again, if ye by the grace of God are perfect in Christ, and deny not his power, then are ye sanctified in Christ by the grace of God, through the shedding of the blood of Christ, which is in the covenant of the Father unto the remission of your sins, that ye become holy, without spot. (Moroni 10:32–33)

Summary

There is no need to try to make the doctrine of sanctification and justification into a mysterious, difficult doctrine. It is very simple and yet deeply profound. God’s nature is that of perfect holiness and perfect righteousness. Anyone who would be like Him and dwell with Him must achieve a similar state of holiness and perfection. Through the blood of Jesus Christ and the operation of the Holy Ghost in our lives, we can be made just and holy, and then by continually looking to Christ and the Spirit we can be kept just and holy.

Without justness (tsadak) and holiness (kadash), we cannot have a full relationship with God, for uncleanness and unrighteousness are contrary to His nature. Thus, the doctrines of justification and sanctification are designed to make us more and more like God. President Brigham Young understood this when he defined virtue (another word for righteousness or justness) and sanctification in this manner:

What I consider to be virtue, and the only principle of virtue there is, is to do the will of our Father in heaven. That is the only virtue I wish to know. I do not recognize any other virtue than to do what the Lord Almighty requires of me from day to day. In this sense virtue embraces all good; it branches out into every avenue of mortal life, passes through the ranks of the sanctified in heaven, and makes its throne in the breast of the Deity. When the Lord commands the people, let them obey. That is virtue.

The same principle will embrace what is called sanctification. When the will, passions, and feelings of a person are perfectly submissive to God and His requirements, that person is sanctified. It is for my will to be swallowed up in the will of God, that will lead me into all good, and crown me ultimately with immortality and eternal lives.[6]

Notes

[1] Robert B. Girdlestone, Synonyms of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1976), 175.

[2] Girdlestone, Synonyms, 176.

[3] See Girdlestone, Synonyms, 103.

[4] Girdlestone, Synonyms, 171.

[5] Bruce R. McConkie, Mormon Doctrine, 2d ed. (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1976), 408; emphasis added.

[6] Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses (London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1854–86), 2:123