War and Peace—Lessons from the Upper Room

Kent P. Jackson

Kent P. Jackson, “War and Peace—Lessons from the Upper Room,” in To Save the Lost, ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and Kent P. Jackson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 35–59.

Kent P. Jackson was a professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University when this was published.

Three days before his Crucifixion, Jesus sat with the Twelve on the Mount of Olives and spoke with them of the future. He warned them that the world would be an increasingly hostile place for them, and the same would be true for other Saints of their time and for his disciples in the latter days as well. As he taught them, he spoke of apostasy, betrayal, hatred, false prophets, false Christs, abounding iniquity, and declining love (see Joseph Smith—Matthew 1:6, 8–10). His message regarding the Apostles themselves was anything but a happy one. “Then shall they deliver you up to be afflicted,” he said, “and shall kill you, and ye shall be hated of all nations, for my name’s sake” (Joseph Smith—Matthew 1:7).

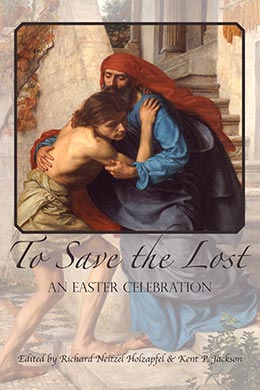

Max Thalmann, Last Supper, Brigham Young University Museum of Art

Max Thalmann, Last Supper, Brigham Young University Museum of Art

In Jerusalem today, there is a medieval Roman Catholic chapel in a building constructed by the Crusaders to mark the sites of events from the Bible. The room represents for millions of pilgrims the upper room in which Jesus met with his disciples the evening before his Crucifixion. We call that meeting the Last Supper. In the most intimate conversation with the Twelve recorded in the New Testament, Jesus spoke with them about things to come and about how they were to carry on through the difficult times that lay ahead for them. He warned them again, in very clear language, that the world would hate them. Such would be the case because the Apostles, like all Christians, were not of the world. People would kill them, he said, thinking that in doing so they would be doing God a favor (see John 15:18–19; 16:2). Yet with pointed irony, in words that are as surprising in this context as they are reassuring, Jesus concluded his discussion by saying, “These things I have spoken unto you, that in me ye might have peace. In the world ye shall have tribulation: but be of good cheer; I have overcome the world” (John 16:33; emphasis added).

The Cenacle, or Upper Room, Jerusalem. All photos courtesy of Kent P. Jackson.

The Cenacle, or Upper Room, Jerusalem. All photos courtesy of Kent P. Jackson.

Living in Days of Wars and Rumors of Wars

The scriptures call our time “days of wickedness and vengeance” (Moses 7:60). We experience in these days much tribulation, and thus, like Jesus’ ancient disciples, we need to learn how to have peace in spite of it. We witness “wars, and rumors of wars” (Joseph Smith—Matthew 1:23), and we experience many other evils and sorrows that God’s children have brought upon themselves. The Book of Mormon teaches us how to live in such troubled times. It is not an accident that Mormon provided only twenty-three verses for the two-hundred-year period of peace following Jesus’ visit to the children of Lehi (see 4 Nephi 1:1–23), yet he wrote twenty chapters about warfare covering only fifteen years (see Alma 43–62). Those chapters are followed by more that recount a droning litany of political intrigue, conspiracies, murder, war, apostasy, betrayal, economic collapse, and societal decline and dissolution (see Helaman 1 through 3 Nephi 7). Mormon clearly wanted his latter-day readers to learn how to endure faithfully in a world of turbulence and tragedy, because he knew that many of us would live in such a world.

War is not the only tribulation that humanity faces today. But we focus on it because it has been such a common part of world history in modern times and because it continues to plague us now. We need to learn how to live in days like these.

War is from Satan, and peace is from God. In the Book of Mormon, we learn that righteous people never start wars. War sometimes comes upon people who do not deserve it but are subjected to it because of the wickedness of other people. Perhaps paradoxically, the book praises both those who are forced to defend themselves militarily and also those who made a covenant never to bear arms and who would rather die than shed the blood of their brothers. In the Book of Mormon, we learn that those who initiate wars often proclaim high-minded principles, such as the righting of past wrongs (for example, see Alma 54:17–18; 3 Nephi 3:10). Yet the book exposes their true motives to be those most common, but devil-like, human traits: hatred and the desire for power (see Alma 2:10; 43:7–8; 46:4; 51:8; Helaman 2:5). The Book of Mormon teaches that men may defend themselves when attacked (see Alma 43:46–47), but it condemns preemptive military action, even against wicked people who desire to do us harm (see 3 Nephi 3:20–21). The only time righteous people in the Book of Mormon enter “enemy” lands is when they do so to teach their brothers and sisters the gospel (see Alma 26:23–26). The Book of Mormon shows that missionary work among intractable foes is a more successful means of neutralizing their threats than is waging war against them (see Alma 31:5; Helaman 5:20–52; 6:37).

Given human nature, war may be inevitable, but how one responds to it is a conscious choice between discipleship on the one hand, and following the ways of the world on the other. History has shown that politicians can easily invent justifications for military aggression, and they can stir up crowds to cheer the start of a war and to enlist to fight in it. But Latter-day Saints, like Jesus’ ancient disciples, are not of the world, and thus we can never really be part of it and its ways. Our scriptures are clear: we are commanded by God to “renounce war and proclaim peace” (D&C 98:16), and righteous nations are only allowed to engage in military action—always with sorrow and profound reluctance—to protect their homes, their liberties, their families, and their religion, and to protect weaker peoples under their care. This is the law of war that the Book of Mormon teaches so clearly (see Alma 27:21–24; 43:9–10, 45–47). In contrast, the natural man—“an enemy to God” (Mosiah 3:19)—seeks to change other people by imposing on them by force his own vision of what is right, sometimes even rationalizing that it is for his opponents’ own good.

When Jesus met with the Twelve on the Mount of Olives, he prophesied that warfare would be a common feature in the latter days, twice stating that we would “hear of wars, and rumors of wars” yet pointing out that the existence of such would not mean that the end is necessarily near (Joseph Smith—Matthew 1:23, 28). The implication seems to be that wars and the tragedies that accompany them would be a predictable characteristic of the world in which we live—not exceptional events. This surprises no one, because humanity has witnessed warfare and murder in the past hundred years on a scale greater than anyone could have imagined before. My ninety-three-year-old father has lived through the most devastating man-made disasters in human history—World Wars I and II—and also the Korean and Vietnam Wars, two wars in Iraq, and various other conflicts. In addition to these wars that involved the United States, his lifetime has coincided with unspeakable atrocities that rulers have imposed upon their own people and countless other wars, conflicts, and genocides that have taken a toll in human suffering and sorrow beyond comprehension. Despite the lessons we should be learning from history, virtually all those who started these tragedies, whether they won or lost, were hailed by their own as heroes, and monuments were built in their honor. Truly, as Jesus foretold of our time, “iniquity shall abound,” and “the love of men shall wax cold” (Joseph Smith—Matthew 1:30).

Not all of the tribulations that people experience in the latter days will be caused by war and political unrest. But because these will likely remain with us now and in future generations, we need to learn how to deal with them. Like the ancient disciples who were tutored by Jesus during the last days of his mortality, we want to know, how can we live in a world of wars and rumors of wars and not be of it? How can we have peace?

The gospel teaches that we can have peace. If Jesus were with us today, how would he address us in light of the challenges we face? Perhaps he would say to us what he said to them. To learn from his words, let us enter the upper room and join the ancient disciples to be taught at Jesus’ feet.

Why Will We Have Peace?

Jesus said, “Peace I leave with you, my peace I give unto you: not as the world giveth, give I unto you. Let not your heart be troubled, neither let it be afraid” (John 14:27). This passage has great power because its words so dramatically transcend the somber setting in which they were spoken, with warnings of rejection, persecution, wars, and murder. Yet despite all this, Jesus promised them peace. It would not be the peace of the world; it would be his peace. And it would be such that if they would embrace it, they would not need to have troubled hearts, nor would they need to fear.

On that evening in the upper room, Jesus gave his Apostles the solution by teaching them four reasons why they—and we—can have peace. Each of the reasons prepares us and fortifies us. Each provides a key whereby we can have peace in spite of the world. First, we can have peace because Jesus went ahead to prepare a place for us; second, because he has revealed the Father to us; third, because he does not leave us comfortless; and fourth, because he taught us how to love.

“I go to prepare a place for you” (John 14:2). Jesus said, “In my Father’s house are many mansions: if it were not so, I would have told you. I go to prepare a place for you” (John 14:2). Belief in an afterlife better than this life places hope in the hearts of millions of people and enables them to endure and persevere through life’s trials. Most religions teach, in one form or another, that our stay here is temporary and preparatory and that it will be worth it in the next life to live properly in this one. The Prophet Joseph Smith taught, “What have we to console us in relation to our dead? We have the greatest hope in relation to our dead of any people on earth. We have seen them walk worthy on earth, and those who have died in the faith . . . have gone to await the resurrection of the dead, to go to the celestial glory.”[1] But Jesus’ statement teaches much more than a happy life after death. The mention of “many mansions”—more accurately translated “rooms” or “dwelling places”—suggests the doctrine of varying degrees of glory, something confirmed in revelations to Joseph Smith (see D&C 76). The Prophet once gave a paraphrase that broadens our perspective: “In my Father’s kingdom are many kingdoms.”[2]

Jesus said, “When I go I will prepare a place for you, and come again, and receive you unto myself, that where I am ye may be also” (Joseph Smith Translation, John 14:3).[3] When we read that Jesus was about to leave the earth to prepare for our arrival in heaven, we sometimes focus on the verb prepare that he used. He was going ahead to prepare a place for us. Perhaps we might imagine him going to our new mansion, opening the big doors, arranging the furnishings, and making it ready for our coming. But is that where Jesus went so we could have a place with him in the Father’s kingdom? Notice his words to the Prophet Joseph Smith, which describe where he went and the full nature of the preparations he undertook there in our behalf: “For behold, I, God, have suffered these things for all, that they might not suffer if they would repent; but if they would not repent they must suffer even as I; which suffering caused myself, even God, the greatest of all, to tremble because of pain, and to bleed at every pore, and to suffer both body and spirit—and would that I might not drink the bitter cup and shrink—nevertheless, glory be to the Father, and I partook and finished my preparations unto the children of men” (D&C 19:16–19; emphasis added).

To provide for us the most direct route to our heavenly reward, he took a dreadful detour in our behalf. His journey included the Garden of Gethsemane, where he shed blood from every pore and wished not to partake of the bitter cup. He went there so we would not have to go there.

Jesus and the Bitter Cup, Church of St. Mary Magdalene, Jerusalem.

Jesus and the Bitter Cup, Church of St. Mary Magdalene, Jerusalem.

On the slope of the Mount of Olives today is the Russian Orthodox Church of St. Mary Magdalene, built at the place that Russian pilgrims venerate as the Garden of Gethsemane. In the church, amidst the smoke of the candles and incense burners, is a painting of Jesus on his knees, praying to the Father. Above and in front of him, suspended in the air or held by unseen hands, is the bitter cup of which Jesus was to drink. The cup is not painted in true perspective but is two-dimensional, like a shadow. Jesus’ eyes are riveted on the cup, and the viewer is left to interpret for him- or herself what he was thinking or saying at the moment depicted. Was it “Father, if thou be willing, remove this cup from me”? Or was it “Not my will, but thine, be done” (Luke 22:42)?

Jesus’ journey to prepare our place also included Golgotha, where he suffered the unspeakable torture of crucifixion and died. Where did Jesus go when he died in order to prepare a place for us in the Father’s kingdom? We, if we die faithful, will be “taken home to that God who gave [us] life” and “received into a state of happiness” (Alma 40:12) to await a glorious resurrection. But such was not the case with Jesus.

On his journey, Jesus descended below all things, traveling to where he did not need to go for his own sake but where he chose to go for ours. Remarkably, he did it because he loves us and wants us to be with him, “that where I am,” he said, “ye may be also” (John 14:3). Or, as Joseph Smith paraphrased, “that the exaltation that I receive you may receive also.”[4] As imperfect as we are without his attending grace, we should be moved to eternal gratitude to know that our perfect Savior is not satisfied unless his disciples are where he is.

Surely, a heavy price was paid to prepare a place for us. And surely, he is “the way, the truth, and the life,” and “no man cometh unto the Father” but by him (John 14:6).

A fresco in the tiny Orthodox Dark Church in Cappadocia, Turkey, shows Jesus overcoming death. He stands on a vanquished Satan, who lies chained and powerless. Under Jesus’ feet are the shattered remains of the gate of hell and the fetters that once bound those who were captives to sin and death. The resurrected Jesus, conqueror in his war against sin and death, lifts Adam to life out of the grave. Behind Adam, and on the other side of Jesus, are other worthy people, each one awaiting his or her turn to be taken by the hand and drawn up to salvation. We who are the beneficiaries of Christ’s atoning work can have the hope that he will likewise lift us up. And this hope will bring us peace in this life—Jesus’ peace—despite the tribulations of the world and the chains that bind us now.

The Resurrection, Dark Church, Göreme, Turkey

The Resurrection, Dark Church, Göreme, Turkey

“If you know me, you will know my Father also” (New Revised Standard Version, John 14:7). Another reason we can find peace in this world of war is because Jesus has revealed the Father to us. His teachings about God are made most important by the fact that Jews in his day had lost all knowledge of God the Father separate from Jehovah. When he proclaimed that he was Jehovah, the God of ancient Israel, he also made known the Father and revealed the true nature of the Godhead and his role in it (see John 8:58). Jesus said, “If ye had known me, ye should have known my Father also: and from henceforth ye know him, and have seen him. Philip saith unto him, Lord, shew us the Father, and it sufficeth us. Jesus saith unto him, Have I been so long time with you, and yet hast thou not known me, Philip? he that hath seen me hath seen the Father; and how sayest thou then, Shew us the Father?” (John 14:7–9).

Indeed, Christ’s character is perfect and so in harmony with that of the Father that everything he said and did in mortality represented what the Father would have said or done had he been there. We do not need to see the Father, because we see the Father manifested in Christ. “Believest thou not that I am in the Father, and the Father in me?” he asked. “The words that I speak unto you I speak not of myself: but the Father that dwelleth in me, he doeth the works. Believe me that I am in the Father, and the Father in me” (John 14:10–11).

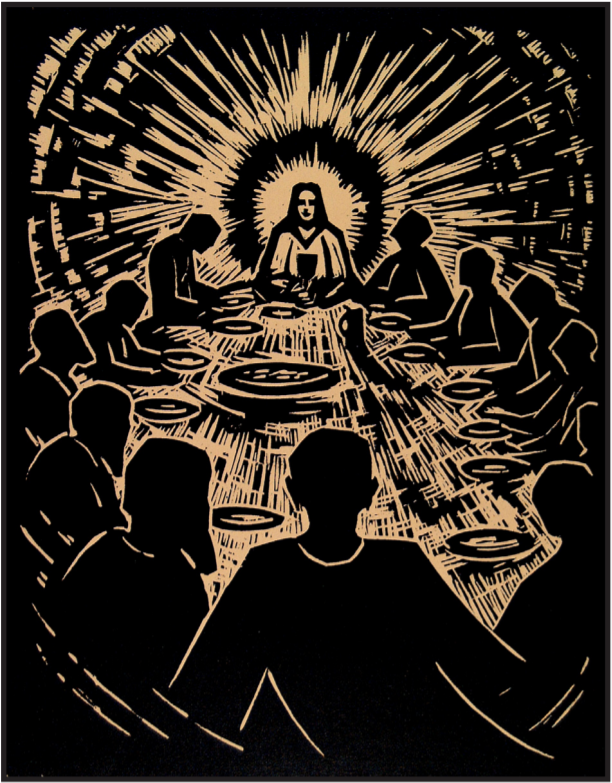

A beautiful medieval depiction of Jesus is found in a mosaic in the Byzantine Church of Holy Wisdom (or Hagia Sophia) in Istanbul. Jesus is shown in his divine role as Pantocrator—the Almighty, or Ruler of All. He has the holy scriptures in one hand and is making a gesture of blessing with the other. This is an image not of Jesus’ mortality and suffering but of his Godhood. The Pantocrator image is often found in high domes in Orthodox churches, so worshipers can see Jesus in his majesty high above them. He is the perfect representation of God, “the brightness of [the Father’s] glory, and the express image of his person” (Hebrews 1:3). “In him the whole fullness of deity dwells bodily” (NRSV, Colossians 2:9).

Mosaic of Jesus as Pantocrator, Hagia Sophia, Istanbul.

Mosaic of Jesus as Pantocrator, Hagia Sophia, Istanbul.

Beyond the truths we learn about God in the upper room, there are even greater truths made known through the Restoration of the gospel, among which is the comforting knowledge that God truly is our Father and that we truly are his children. Joseph Smith taught: “What kind of a being is God? . . . The scriptures inform us that ‘this is eternal life, to know the only wise God and Jesus Christ whom he has sent’ [John 17:3]. If any inquire what kind of a being God is, I would say, If you don’t know God, you have not eternal life. Go back and find out what kind of a being God is.” Then the Prophet said: “I will tell you, and hear it, O earth! God, who sits in yonder heavens, is a man like yourselves. That God, if you were to see him today, that holds the worlds, you would see him like a man in form, like yourselves. Adam was made in his image.”[5]

We do not worship an unknown God, because Jesus has revealed him to us. We know him, we know his nature, we know his work, and we draw peace in a world of tribulation from knowing the profound truth sung around the world by Latter-day Saint children: “I am a child of God, and he has sent me here.”[6] Because we know that he is a loving Father in Heaven, we trust his judgment, we trust his plan, and we know that despite the sorrows of the world, he is there for us.

“I will not leave you comfortless” (John 14:18). A third reason why we can have peace in a world at war is that Jesus has not left us alone. The Gospels suggest that the Twelve did not grasp, even on that evening before the Crucifixion, what would be happening to Jesus later that night and the next day, or how those events would dramatically change everything about their world. They would soon find themselves seemingly abandoned, leaderless, confused, and without direction. They would experience the effects of Nephi’s prophecy that “the multitudes of the earth” would be “gathered together to fight against the apostles of the Lamb” (1 Nephi 11:34). But Jesus knew that the Twelve would carry forth his mission. He would not leave them alone to face the world; he would send them the Holy Spirit to be their Comforter and their Teacher. He told the Apostles, “I will pray the Father, and he shall give you another Comforter, that he may abide with you for ever; even the Spirit of truth; whom the world cannot receive, because it seeth him not, neither knoweth him: but ye know him; for he dwelleth with you, and shall be in you” (John 14:16–17).

Little did the Twelve know at that time how vital the Spirit’s presence would become in their lives, how its influence would transform them, enlarge them, and enlighten them. Among other things, it would bring back to their memory things that Jesus had taught them that they could not understand without its influence. “These things have I spoken unto you, being yet present with you,” he said. “But the Comforter, which is the Holy Ghost, whom the Father will send in my name, he shall teach you all things, and bring all things to your remembrance, whatsoever I have said unto you” (John 14:25–26). Jesus told them that the Holy Spirit would be able to teach them things that they could not learn from him. “I have yet many things to say unto you,” he said, “but ye cannot bear them now. Howbeit when he, the Spirit of truth, is come, he will guide you into all truth: . . . and he will shew you things to come” (John 16:12–13).

After their reception of the Holy Ghost, the Twelve were changed men. Whereas they are sometimes depicted in the Gospels as uncertain and confused, they are shown in Acts and in their letters to be powerful men with a clear vision of where the Church was going and how they would lead it there. As promised, the Holy Ghost brought things to their memory (see John 12:16) and guided them to truth (see Acts 10:1–35).

It is not incidental that Jesus called the Holy Spirit the Comforter. Many thousands of Latter-day Saints today can attest to the peace brought into their lives by the Comforter’s presence. They can tell of heavy burdens they are able to lift with the Spirit’s help and of knowledge and wisdom they have received under the Spirit’s instruction. Latter-day Saints who have lived during earlier wars—particularly those who have fought in them—can attest to the Spirit’s presence among his Saints, even in the worst of times.[7]

Joseph Smith taught: “After a person hath faith in Christ, repents of his sins, and is baptized for the remission of his sins, and received the Holy Ghost (by the laying on of hands), which is the first Comforter, then let him continue to humble himself before God, hungering and thirsting after righteousness and living by every word of God. And the Lord will soon say unto him, ‘Son, thou shalt be exalted.’”[8] In the world to come, faithful Latter-day Saints will enter the divine presence, where “the keeper of the gate is the Holy One of Israel; and he employeth no servant there” (2 Nephi 9:41). There they will be found worthy and will be welcomed home by their Savior, finding ultimate peace in the assurance of eternal life. Some have had assurances while yet in this life (see 2 Timothy 4:6–8; D&C 132:49), but all who will be heirs of the celestial kingdom can feel even now the peace that Jesus brings, not the peace of the world, but knowledge from the Comforter that their course has been correct and that they were not left comfortless along the way.

“Continue ye in my love” (John 15:9). A fourth reason why we can find peace in this life is because Jesus has taught us how to love—to love both God and our fellowmen. The love of Christ brings peace. “A new commandment I give unto you,” he said in the upper room. “That ye love one another; as I have loved you, that ye also love one another. By this shall all men know that ye are my disciples, if ye have love one to another” (John 13:34–35). It should be profoundly important to us that the test Jesus gives to demonstrate true discipleship is the love we show to each other. It is likewise important that the model he gives is his own love for us: “This is my commandment, That ye love one another, as I have loved you” (John 15:12). If that is our model, we should consider seriously the extent to which Jesus was willing to show his love for us.

One of the earliest images of Jesus is of him as the Good Shepherd. A fourth-century relief from Carthage, North Africa, shows him with a lamb on his back, depicted as in the parable of the lost sheep (see Luke 15:4–6). He told his disciples, “I am the good shepherd, and know my sheep, and am known of mine” (John 10:14). His use of the shepherd imagery was not only to show that he was our leader but more to show the quality of his leadership and his love. “The good shepherd giveth his life for the sheep,” he said, “and I lay down my life for the sheep” (John 10:11, 15). In the upper room, he taught, “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends” (John 15:13).

Love is a powerful source of peace in life. Often those who love and know they are loved are the happiest of people, whereas those who do not or cannot love are the most miserable. Joseph Smith taught that love is “one of the chief characteristics of Deity” and that it “ought to be manifested by those who aspire to be the sons of God.”[9] But can we love in a time of war, and are we really expected to love our enemies? Is it not easier to dehumanize them in our minds and in our speech so we do not have to think of them as God’s children? Is it not more expedient politically to refuse to sit with them than it is to try to make peace with them, or even to try to bless their lives? The Book of Mormon, again, teaches conduct that is directly contrary to how nations behave today. We can learn much from the example of the sons of King Mosiah. When they, through their repentance, found Jesus’ peace in their own lives, they could not rest until they had shared that peace with others. When some of their countrymen expressed dismay that they wanted to teach their “enemies” and argued instead that they should kill them, the sons of Mosiah, in contrast, worked at great personal risk to share with them the gospel (see Alma 26:23–26). It is interesting to note that throughout the Book of Mormon, the righteous call their opposing nation “our brethren,” even in times of war against them (see Jacob 7:26; Mosiah 22:3; Alma 56:46). Joseph Smith taught that one who is “filled with the love of God, is not content with blessing his family alone, but ranges through the whole world, anxious to bless the whole human race.”[10] Those filled with God’s love do not know national or ethnic boarders for their love. They truly believe, as Nephi taught, that “the Lord esteemeth all flesh in one,” and that “all are alike unto God” (1 Nephi 17:35; 2 Nephi 26:33).

Jesus as Good Shepherd, Carthage, North Africa.

Jesus as Good Shepherd, Carthage, North Africa.

Jesus taught that another manifestation of our love for him is our desire to keep his commandments. He said, in a passage not well translated in the King James Version, “If ye love me, ye will keep my commandments” (John 14:15, emphasized words added). The future tense shows that obeying Jesus is a natural product of loving him, not just a response to a command. “He that hath my commandments, and keepeth them, he it is that loveth me,” Jesus said (John 14:21). And “If a man love me, he will keep my words” (John 14:23).

Loving Jesus is its own reward. It brings into our lives the companionship of the Holy Ghost and the knowledge that our lives are in harmony with Jesus’ will. And it brings us peace. The Savior said, “As the Father hath loved me, so have I loved you: continue ye in my love. If ye keep my commandments, ye shall abide in my love; even as I have kept my Father’s commandments, and abide in his love. These things have I spoken unto you, that my joy might remain in you, and that your joy might be full” (John 15:9–11).

Peace and Joy

As we leave the upper room and consider again our own world of wars and rumors of wars, we are reminded of the causes of many of life’s conflicts and of the path that leads to the peace that Jesus promised. The Book of Mormon, in an earlier time of tribulation, tells us that the warfare the people experienced “would not have happened had it not been for their wickedness and their abomination” (Helaman 4:11). Mormon provides a list of what those abominations were: pride, oppressing the poor, withholding food from the hungry and clothing from the naked, mocking that which is sacred, denying revelation, murdering, plundering, lying, stealing, committing sexual sin, and creating contention and political dissension (see Helaman 4:11–12). Needless to say, all of these are common today, and thus there is no reason why our society should boast in its own strength that we will be immune from the consequences of such things (see Helaman 4:13).

God the Father, St. Peter in Gallicantu, Jerusalem.

God the Father, St. Peter in Gallicantu, Jerusalem.

The antidote to all of this is to live the gospel. But the sad and frank reality is that the world as a whole will never again be a place of peace until the Prince of Peace comes again to receive his kingdom. In an extraordinary contribution of his New Translation of the Bible, the Prophet Joseph Smith revealed the account of Enoch’s vision from his own time to the end of the world. Enoch saw Satan with “a great chain in his hand,” veiling the whole face of the earth with darkness—symbols that are so stark they need no explanation. In response to the misery of the human family, Satan “laughed, and his angels rejoiced” (Moses 7:26). God, however, looked upon the scene and wept (see v. 28). How striking is the contrast in the vision between God and Satan. Why did God weep? He told Enoch that he had commanded the people to “love one another”—the same “new” commandment that Jesus gave his disciples in the upper room—yet they were “without affection, and they hate[d] their own blood” (Moses 7:33).

A Catholic church in Jerusalem, St. Peter in Gallicantu, contains a striking modern mosaic showing God the Father in the heavens. He is observing, with obvious emotion, things that are happening on earth below. In his vision, Enoch saw the earth crying out, “When shall I rest, and be cleansed from the filthiness which is gone forth out of me?” (Moses 7:48). Enoch picked up the refrain himself and asked God twice, “When shall the earth rest?” (Moses 7:58; see also v. 54). The setting for the St. Peter in Gallicantu mosaic is the trial of Jesus, with the cross looming above the trial scene and the Father looking down from above the cross. God has his hand at his forehead and is filled with remorse at what he sees; perhaps he is weeping.

Enoch was told that the earth will indeed rest someday, but its rest will come only after a time of “great tribulations.” Yet even in the midst of those tribulations, “my people will I preserve,” the Lord said (Moses 7:61). We and our descendants are the Lord’s people living in that day of great tribulations. The Lord will preserve us (see D&C 115:6).

Traditional tomb of Jesus, Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem

Traditional tomb of Jesus, Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem

Can we have peace and happiness in this world of violence? We can. It is interesting to note that in two Book of Mormon passages, the word joy is found in the context of the word peace. Mormon reports, “There was peace and exceedingly great joy in the remainder of the forty and ninth year; yea, and also there was continual peace and great joy in the fiftieth year of the reign of the judges.” “And in the sixty and fifth year they did also have great joy and peace” (Helaman 3:32; 6:14; emphasis added). In these instances, the joy the Saints were experiencing was in brief periods of peace between wars. Another example comes from an earlier generation: “But behold there never was a happier time among the people of Nephi, since the days of Nephi, than in the days of Moroni, yea, even at this time, in the twenty and first year of the reign of the judges” (Alma 50:23). Despite the constant threat of warfare in Captain Moroni’s time, the people were happy then, because they were one and they were living the gospel.

Jerusalem’s Church of the Holy Sepulchre is the traditional (and most likely) place where Jesus Christ was buried and resurrected. Inside the church, there is an Orthodox chapel that may still contain remnants of the rock-cut tomb in which Jesus’ body lay. On a beautiful altar cloth is embroidered a simple two-word inscription. It reads christos anestē, “Christ is risen.”

Christ is risen, and we will be preserved and have peace in this turbulent world because he has, as he told his disciples in the upper room, overcome the world. And because he has overcome the world, we can “be of good cheer” (John 16:33). The Church of Jesus Christ will continue to roll forward despite the world, and faithful Saints, living the gospel and keeping themselves clean from the sins of their generations, will have Jesus’ peace—the true peace—in their hearts and in their homes and in their lives. The warfare of the world will continue and will take its casualties, but for those who endure faithfully, the words of President Gordon B. Hinckley will be true: “We are winning, and the future never looked brighter.”[11]

Notes

[1] Andrew F. Ehat and Lyndon W. Cook, eds., The Words of Joseph Smith: The Contemporary Accounts of the Nauvoo Discourses of the Prophet Joseph (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1980), 347; spelling, capitalization, and punctuation standardized.

[2] Ehat and Cook, Words of Joseph Smith, 371; capitalization and punctuation standardized.

[3] Thomas A. Wayment, ed., The Complete Joseph Smith Translation of the New Testament (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2005), 246.

[4] Ehat and Cook, Words of Joseph Smith, 371.

[5] Ehat and Cook, Words of Joseph Smith, 343–44; spelling, capitalization, and punctuation standardized.

[6] Naomi W. Randall, “I Am a Child of God,” Hymns (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1985), no. 301.

[7] See Robert C. Freeman and Dennis A. Wright, Saints at War: Experiences of Latter-day Saints in World War II (American Fork, UT: Covenant, 2001), 137, 319, 351.

[8] Ehat and Cook, Words of Joseph Smith, 5; capitalization and punctuation standardized.

[9] Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 2nd ed. rev. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1957), 4:226.

[10] Smith, History of the Church, 4:226.

[11] Gordon B. Hinckley, “An Unending Conflict, a Victory Assured,” Ensign, June 2007, 9.