To the Least, the Last, and the Lost

Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and Kent P. Jackson

Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and Kent P. Jackson, “To the Least, the Last, and the Lost,” in To Save the Lost, ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and Kent P. Jackson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), vii–xi.

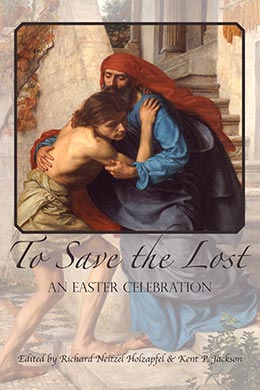

A strong theme in the scriptures is reversal. We are often surprised as the meek, instead of the powerful, inherit the earth (see Matthew 5:5), a Gentile centurion submits to the authority of Jesus, a lowly Jew (see Matthew 8:5–13), and God reveals his will to “babes” instead of the wise (Matthew 11:25). In a truly amazing scene, a dignified landholder sets aside his pride of position and runs to embrace his returning son (see Luke 15:20). However, the most important reversal of all is this: the Son of God dies so humanity can live (see Mark 14:24).

Jesus’ mission—to the least, the last, and the lost—is built on such reversals. His redemptive work facilitated them, as shown in the fact that the primary meaning of repent in the biblical languages Hebrew and Greek is “turn around” or “return.” Through the gospel, the least become the greatest in the kingdom of God (see Luke 9:48), the last become the first (see Matthew 19:30), and the lost are found (see Luke 15:32).

Easter is a good time to recall Jesus’ mission to the least, the last, and the lost, for he said, “The Son of man is come to save that which was lost” (Matthew 18:11; emphasis added). Not surprisingly, we discover that he sent his disciples to the “lost sheep” (Matthew 10:6), and thus their mission of finding the lost is a natural extension of his. We, who desire to be his disciples in the latter days, gladly embrace our part in that mission, and we are reminded of his words that are at the very core of living the gospel: “Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me” (Matthew 25:40).

Some of Jesus’ most memorable teaching moments have to do with finding the lost. Luke preserves the parables of the lost sheep, lost coin, and lost son and ties them together with a common theme—the joy of finding that which is lost. He introduces them by providing the historical context: Jesus was meeting with people who were considered wicked and unclean—publicans and sinners. As in other such settings, the Pharisees and scribes begin to complain, “This man receiveth sinners, and eateth with them” (Luke 15:2).

Luke tells the story: “And he spake this parable unto them, saying, What man of you, having an hundred sheep, if he lose one of them, doth not leave the ninety and nine in the wilderness, and go after that which is lost, until he find it? And when he hath found it, he layeth it on his shoulders, rejoicing. And when he cometh home, he calleth together his friends and neighbours, saying unto them, Rejoice with me; for I have found my sheep which was lost” (Luke 15:3–6). The second parable continues the theme: “What woman having ten pieces of silver, if she lose one piece, doth not light a candle, and sweep the house, and seek diligently till she find it? And when she hath found it, she calleth her friends and her neighbours together, saying, Rejoice with me; for I have found the piece which I had lost” (Luke 15:8–9).

These parables have nothing to do with sheep or coins, of course, but with the finding of lost souls. What they do not include is much detail about what it took to find what was lost, what efforts were expended, how many tears were shed and prayers uttered. Both stories reveal a common conclusion: there is joy in heaven over one “sinner that repenteth” (Luke 15:7, 10). And both teach that whatever was required to find the lost sinner was worth it.

The final parable presents the theme in human form. In English, tradition has imposed upon it the unfortunate title “Prodigal Son”—prodigal meaning “wasteful,” the least important element of the parable. It is really the story of a lost son, and it speaks to us today as well as it did to the disciples in Jesus’ day.

A Jewish father has two sons. The younger asks the father for his inheritance and departs to a far country, a Gentile land, where he “wasted his substance with riotous living” (Luke 15:13) and ends up destitute. The next scene reveals the consequence of his bad choices: “He went and joined himself to a citizen of that country; and he sent him into his fields to feed swine” (Luke 15:15). The reversal is complete: the Jewish son of a land-rich father is forced to become a hired servant of a Gentile, feeding pigs! Yet when it seems the lost son has descended as low as he possibly could, we discover that matters are indeed worse. He has to compete with the pigs for food. Finally “he came to himself,” and he decides to return to his father, where even the “hired servants” have “bread enough and to spare” (Luke 15:17).

At this point in the story, we may be tempted to think, “I’m glad I’m not like him.” Yet the story has enough parallels with everyone’s life that we should be able to see something in it about us. At the very least, we, on occasion, need to “come to ourselves” and decide to return to what we, like the lost son, know to be right. And if we are teachable, we too will learn that our own resources are used up, that we have nothing left, and that we must rely on the grace of someone greater to welcome us back to his family and home.

The lost son returns to his father, saying, “I have sinned against heaven, and in thy sight, and am no more worthy to be called thy son” (Luke 15:21). In another reversal of the plot, the father chooses to “bring the best robe, and put it on him; and put a ring on his hand, and shoes on his feet” (Luke 15:22). Further, like the owners of the lost sheep and the lost coin, the father calls together those around him to celebrate: “Bring hither the fatted calf, and kill it; and let us eat, and be merry” (Luke 15:23).

Now the parable reveals a story within a story, and it too is a reversal. The dutiful elder son has returned from a day’s labor in the field to discover music and dancing at his father’s house. When a servant informs him that his younger brother has returned and received the royal treatment, the elder brother becomes angry and refuses to enter the house. For the second time, the father leaves the house to go outside to welcome a son home (see Luke 15:25–28). It seems that even the most righteous among us are in need of “pardoning mercy.” And, thankfully, we are within its reach.[1]

Remember the worth of souls is great in the sight of God;

For, behold, the Lord your Redeemer suffered death in the flesh; wherefore he suffered the pain of all men, that all men might repent and come unto him.

And he hath risen again from the dead, that he might bring all men unto him, on conditions of repentance.

And how great is his joy in the soul that repenteth! (D&C 18:10–13)

As we contemplate the “lasting grace” and the “boundless charity” of our Savior,[2] let us, like those in the parables, rejoice in the finding of those who have been lost. Let us not only welcome them back, but let us help find them as well. But let us also recognize that we too are among the lost ones, always in need of one to seek us out, take us by the hand, and bring us back to our Father’s home.

Notes

[1] Andrew F. Ehat and Lyndon W. Cook, eds., The Words of Joseph Smith: The Contemporary Accounts of the Nauvoo Discourses of the Prophet Joseph (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1980), 77.

[2] Lee Tom Perry, “As Now We Take the Sacrament,” Hymns (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1985), no. 169.