David F. Boone, “'And Should We Die': Pioneer Burial Grounds in Salt Lake City,” in Salt Lake City: The Place Which God Prepared, ed. Scott C. Esplin and Kenneth L. Alford (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, Salt Lake City, 2011), 155–178.

David F. Boone is an associate professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University.

Entrance to the Salt Lake City Cemetery, which was established just one year after the first pioneers arrived in the valley. (Courtesy of David F. Boone.)

Entrance to the Salt Lake City Cemetery, which was established just one year after the first pioneers arrived in the valley. (Courtesy of David F. Boone.)

Four decades ago, avid researcher, historian, teacher, and preservationist T. Edgar Lyon wrote a significant article in the Improvement Era about the uniqueness of nineteenth-century Latter-day Saint pioneers. [1] He noted that, despite our admiration of the pioneers, many aspects that we often associate with the Church’s migration and colonization are not unique to the Church. Latter-day Saints were not, for example, the first group to go west, they did not pioneer any of the major routes they followed, nor did their members comprise the majority of individuals who traversed the continent. Lyon’s thesis was to identify the truly unique aspects of the Church’s efforts to pioneer the great American West. One of the unique elements of Latter-day Saint migration noted by Lyon was their concern for the very old and the very young and their unusual respect for life and death. In other words, they took time to properly care for the sick, afflicted, or less fortunate, and when an individual died along the trail, those who survived took the time, as conditions permitted, to respectfully and even reverently care for and inter the departed.

Latter-day Saint leaders have long taught about the sanctity of life, which includes the passing from mortality. The Prophet Joseph Smith taught:

I would esteem it one of the greatest blessings, if I am to be afflicted in this world, to have my lot cast where I can find brothers and friends all around me [and] . . . to have the privilege of having our dead buried on the land where God has appointed us to gather His Saints together. . . . The place where a man is buried is sacred to me. . . . Even to the aborigines of this land, the burying places of their fathers are more sacred than anything else. . . .

It has always been a great calamity not to obtain an honorable burial: and one of the greatest curses the ancient prophets could put on any man, was that he should go without a burial. [2]

Because the pioneers were so concerned and took time to bury their loved ones who died along the pioneer trail even when conditions were so difficult for them to make the necessary burial arrangements, it stands to reason that their respect for the deceased would not change when they reached their destination. This chapter will trace the burial practices of early Latter-day Saints in the Salt Lake Valley and highlight the establishment of prominent pioneer burial grounds, including the Salt Lake City Cemetery. [3]

Earliest Pioneer Deaths in the Salt Lake Valley

Within days of the entry of Brigham Young’s company into the Salt Lake Valley on July 24, 1847, plowing, planting, and building had begun. Soon other groups began arriving.

Milton Howard Therlkill. On July 29, a group of Latter-day Saint pioneers from the South, known as the “Mississippi Saints,” were the second company to arrive. The Mississippi Saints departed from Monroe County, Mississippi, on April 8, 1846, and wintered in Pueblo, Colorado, where they learned they were ahead of Brigham Young’s party. They were joined in Pueblo by members of the Mormon Battalion’s sick detachment, and in spring they followed President Young’s company westward.

Less than two weeks after the Mississippi Saints arrived in Salt Lake on August 11, 1847, one of their number, three-year-old Milton Howard Therlkill, the son of George and Matilda Jane Crow Therlkill, died in an accidental drowning when he fell into City Creek. Milton was buried a short distance from where the pioneers were camped on property later designated as the Crow lot. [4] As the city continued to grow, the area of the burial was designated as Block 49 in downtown Salt Lake City. The death of Milton Therlkill indicated the need to prepare for others who would follow. As others died, they too were buried in the same plot or block. This became the first Latter-day Saint burying ground in what became the state of Utah.

Carolina Van Dyke Grant. An example of the unusual respect paid to those who died is found in the Jedediah M. Grant family. Jedediah Grant was the captain of the “third hundred families” in a company that departed Winter Quarters, Nebraska, on June 19, 1847, and arrived in the Salt Lake Valley on October 4. Jedediah’s family consisted of his wife, Carolina (called Caroline) Van Dyke Grant, and two daughters: two-year-old Caroline, called Caddie, and an infant named Margaret, born at Winter Quarters just a month before their departure. Caroline was recovering from a difficult delivery. “Caroline had been so weak that she could barely begin the journey a month later.” [5] Her desire was to be with her husband and the Saints, so she stoically embarked on the journey.

Caroline rallied significantly along the trail, and her improvement seemed to indicate she was winning the battle for her life. Unfortunately, when the company arrived at Devil’s Gate along the Sweetwater River, “an epidemic of cholera had broken out, spreading first among the animals and then attacking the people, especially the children.” [6] Due to their weakened condition, both Caroline and her daughter Margaret contracted cholera. Despite their sickness, the train moved on, but the disease was more than their weakened, frail bodies could sustain.

On Thursday, September 1, 1847, Jacob Gates, a member of the pioneer company, recorded, “word came that Capt Grants wife was dying which hindered us a while.” The following day, Gates further recorded, “This morning bro Grants babe dead and she [Caroline] failing,” and on Saturday, September 3, “Buried the dead babe.” [7]

Margaret, like many other pioneer dead, was buried beside the trail. Jedediah buried his daughter in a beautiful white dress that had been prepared earlier by her mother. The pioneers interred the child without a coffin or other means to protect the small body. Soon after, the pioneer company moved on.

With the anguish added by the death of her infant, coupled with the effects of cholera, Caroline continued to decline. “Most in the company expected her own death at any time,” [8] but she fought courageously for her life, and the train continued onward. “In a moment,” remembered Sarah Snow, who had cared for Grant’s older daughter while her mother was sick, “we were both by the bed, while Caddie kissed her mama and tried to huddle into the covers. Sister Grant looked at us knowingly, then as she contentedly closed her eyes again and seemed to be sinking. I heard her whisper to Jedediah, ‘All is well! All is well! Please take me to the valley—Jeddy. Get Margaret—bring her—to me!’ Brother Grant answered tenderly . . . as he sobbed with sorrow, ‘Yes, yes, Caroline. I’ll do my best. I’ll do my best.’” [9]

To fulfill his wife’s dying request, Jedediah had to move quickly. “While the women of the third hundred prepared the body of their leader’s young wife, the men built a box from a dismantled wagon bed.” Captain Grant strapped the improvised coffin to the side of his wagon and drove the seventy-five remaining miles to the valley that his wife had so badly wanted to see. “Driving day and night, he made the infant settlement near the Great Salt Lake on the evening of September 29.” They buried her near the site where Milton Therlkill was interred only weeks before. Grant’s biographer, Gene A. Sessions, credits Carolina Van Dyke Grant as the first adult buried in Salt Lake City. [10]

With her interment in the Salt Lake Valley, Jedediah’s promise to his dying wife was only partially fulfilled. The day after the burial, he left the valley for a return trip to the mountains with help for his company.” After seeing to the immediate needs of those under his charge, he continued eastward with a close friend, Joseph Bates Nobel, in an effort to recover the body of little Margaret. Upon arrival at the place where she was interred, they found that the wolves had uncovered the grave, carried away the body, and scattered any evidence of the child’s remains. Brokenhearted, he returned to his new mountain home.

The Salt Lake City Cemetery

In late September 1847, the Abraham O. Smoot and George B. Wallace company arrived in the valley. [11] Mary Melissa Wallace, the young daughter of George B. and Melissa Melvina King Wallace, was born January 8, 1847, at Winter Quarters and died September 27, 1848, at just twenty-one months of age. No cause of death was listed.

Instead of burying their daughter outside of the pioneer fort in Salt Lake City, as had been done with earlier deaths, George took her tiny body, climbed the city’s east bench, and buried his daughter in a secluded spot in the foothills. George made this unusual move perhaps because as the new settlement grew, the pioneer fort was being surrounded and crowded, so he looked for a place where the grave would not be disturbed. Several other families followed Wallace’s example, and soon the foothill overlooking the Salt Lake Valley became an unofficial burying ground for the Saints in addition to Block 49 east of the fort.

In February 1849, a committee consisting of George B. Wallace, Daniel H. Wells, and Joseph Heywood selected a site in the foothills to recommend as a permanent city cemetery. Wallace was interested in recommending this site for several reasons. First, he had “acted as undertaker during some of the most trying days experienced by the Saints [in Nauvoo].” [12] Second, he had already buried his daughter Mary and another child in the foothills of the Salt Lake Valley. Third, others had buried children there.

Daniel H. Wells reported, “They thought the most suitable place was northeast of the city. Twenty acres was [initially] included in the survey.” [13] The committee’s recommendation was accepted, and today is the site of the Salt Lake City Cemetery. Mary Wallace is recognized as the first burial in the cemetery. In January 1851, the General Assembly of the State of Deseret incorporated Salt Lake City. “A City Council was organized, which administered the affairs of the graveyard.” [14] George Wallace was appointed the first sextant and was responsible for planning, improving the cemetery grounds, recording information about each burial, and overseeing other cemetery operations.

The cemetery was twenty acres when the city was incorporated, [15] and since then it has grown in acreage and number of graves: “from 20 acres and two graves, the Salt Lake City Cemetery grew to 350 acres . . . [and] 110,000 graves.” Today “it’s the largest municipally-owned cemetery in the nation.” There are now two Chinese and two Japanese sections, a section for paupers and prisoners, three Jewish cemeteries, and a Catholic cemetery “now cared for by those congregations.” [16] There is also a mausoleum and areas for Congregation Montefiore (Orthodox Jews), children, soldiers, war veterans, and dignitaries.

In February 1856, a city ordinance was passed that made it necessary for all bodies to be buried in the city cemetery, not on public land. All exceptions to burials outside of the cemetery had to be cleared “by the Mayor and the Committee on Municipal Laws.” [17] But as the city continued to develop and land was apportioned to individuals, it was not unusual that some residents desired to bury their loved ones on their own land. This practice was in part for convenience, but also to provide a final resting place that could be watched over and protected from desecration.

The concern was justified because of local grave robbers. One such character was John Baptiste, who had worked in Salt Lake about three years before he was suspected of grave robbing. When it was discovered that personal property buried with the deceased was missing, corpses were exhumed, John was suspected, and surveillance established. In time, he was caught with stolen goods and admitted a portion of his guilt. [18] “His home was searched and found to be full of clothing,” and it was determined that “after a burial he would open up the grave, take all the clothing, jewelry, etc., and replace the body paying little attention as to how it was done.” He then would soak and dry the clothes and sell them along with items of value taken from the graves. “When the investigation was concluded and the news of this outrage was learned, the cemetery was alive with people digging up their dead. The clothing at his home was all taken to the City Hall where people went and identified their own.” [19] Apparently, no family was exempt; John had exhumed the graves of men, women, and children alike. Elder Wilford Woodruff wrote in his journal, “It was afterwords reported that John Baptist was branded in the forehead as A Robber of the dead . . . & placed upon Millers Island.” [20] Elder Woodruff wrote that it was “one of the most Damniable, Diabolical, Satanical, Helish Sacraleges . . . Committed upon the bodies of the Dead Saints.” [21]

Private Family Cemeteries

Early in the history of Salt Lake City, several families, including those of Church leaders, created and maintained burial grounds on their personal property or in close proximity to their homes. These private cemeteries remained even after the ordinance barring these memorials. In fact, Temple Square was surrounded on all four sides by private family cemeteries. The best known of these are the Kimball-Whitney graveyard on the north, the Brigham Young Family Cemetery on the east, the Willard Richards burial ground on the south, and the Smith family plot on the west side.

Nathaniel V. Jones, bishop of the Salt Lake City Fifteenth Ward, addressed the city council with a concern about private cemeteries: “In the western part of the 15th Ward, where waters can be obtained by digging at a depth of three feet, the inhabitants inter their dead in many instances on their Lots, and the waters continually filtering through the corpse must be unwholesome and liable to engender disease.” Bishop Jones’s proposal, therefore, was to pass “an Ordinance forbidding any persons to inter their dead on their Lots,” and if they had already done so, “to remove them to the burying ground in the Grave Yard, unless by petition they are otherwise permitted to bury on their Lots.” In April 1856, the Salt Lake City Council met to discuss “the subject of permitting certain deceased person interred upon their City Lots [to] remain undisturbed.” [22] The buried remains of the Heber C. Kimball family, George A. Smith family, and others were allowed to stay where they were. The city council also decided “that the remains of the friends of J. M. Grant, V. Shirtleff, General Rich and others buried on the mound in the lot belonging to V. Shirtleff (Section 7, Block 49) be permitted to remain.” [23] All the approved interments were from the private burial grounds and from the burials in the block east of the old fort. In spite of these ordinances, private family cemeteries persisted in the downtown area. Some survive to this day. The Young and Kimball-Whitney cemeteries remain downtown, while other family cemeteries have been displaced to make way for the growing city.

Kimball-Whitney Cemetery. The Kimball-Whitney Cemetery is on property set aside in 1848 for one of the first formally dedicated burial grounds within the valley. Elder Heber C. Kimball and Bishop Newel K. Whitney dedicated the land to the Lord as a private cemetery for their two families. Ann Houston Whitney was the first to be buried there in November 1848. Bishop Whitney died two years later and was laid to rest beside his wife. [24]

The cemetery can be reached from North Main Street via Kimball Lane, approximately one hundred yards directly west from Main Street. The grounds contain a large monument commemorating the burial sites of more than sixty Kimball and Whitney family members, along with their employees, friends, and others. In total, “there are about thirty-five Kimballs, fifteen Whitneys and eleven hired help and friends buried there.” [25]

In 1886, when Solomon Kimball, the son of Heber and Vilate Kimball, returned to Utah from his colonization efforts in Arizona, “he found the cemetery in a bad condition. There was no fence around it. Nine-tenths of the graves could not be identified, and worse yet, the title to the property was in the hands of four different individuals, each of whom was determined to make merchandise [commercialize it].” Later, he learned that the little cemetery had been sold by the city to recoup unpaid taxes on the property. Upon investigation, Solomon discovered that a territorial law exempted burial places from taxation, and he reacquired the property in the name of the Kimball family. He purchased a right-of-way from Main Street, had an iron fence installed, and increased the size of the cemetery. Furthermore, he received perpetual right from the city council “to allow the honored dead to remain there on condition that the family improve, beautify, and take care of this piece of property and allow no more internments to be made there.” [26]

Custodianship of the burial ground remained within the Kimball family through J. Golden Kimball. Afterward, the Church assumed perpetual care of the Kimball-Whitney Cemetery. [27] Several other private cemeteries were to follow suit.

Brigham Young Cemetery (Mormon Pioneer Memorial Monument). The Brigham Young Family Cemetery is located on East First Avenue on Brigham Young’s farm property. Today it is referred to as the Young Family Cemetery and also known as the Mormon Pioneer Memorial Park. [28] The Memorial Park is the burial site of Brigham Young, several of his wives (including Eliza R. Snow), many of his children, and others.

The first burial in the Brigham Young Family Cemetery is believed to be Alva Young, son of Brigham and Louisa Beeman Young, who was buried October 1, 1848. Extant markers suggest there are at least twelve individuals interred on this site, but the identity of others also believed to be buried there would raise that number significantly. Kate B. Carter noted, “The earliest burial date [on a tombstone] in the cemetery is 1874 and the last, 1892, but there must have been burials before [the earliest date] for ten of Brigham Young’s children died in infancy to childhood. . . . It is presumed that at least some of these individuals were interred in their family burial ground.” [29] Later, city laws and ordinances discontinued the practice of private burial grounds, and later still, on March 18, 1927, Richard W. Young, president of the Brigham Young Cemetery Association, “conveyed title by warranty deed” of the cemetery property “to the Corporation of the President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.” It further covenanted “that the burials now situated in and upon the aforesaid land shall in no manner or way be disturbed or removed except upon the legal mandate of the municipal or the proper governmental authority.” [30] It is not known how, why, or when the Brigham Young private burial plot escaped the municipal city government’s ban on private cemeteries.

Willard Richards Family Cemetery. The Willard Richards family home was located on the south side of South Temple Street and on “the east half of the block on the west side of Main Street between South Temple and First South Streets.” When Willard Richards died on March, 11, 1854, “he was buried in the plot that had been set apart for that purpose near the middle of this property.” In addition to President Richards, “three of his wives and several children also had been buried there,” well after the city ordinance prohibiting private burying grounds. This suggests that Willard Richards, like Heber C. Kimball, petitioned for and was granted permission to have a private burial ground for this family. In 1890, Richards’s sons Joseph and Willard were interested in developing the Richards Street property. Heber John Richards, custodian of the Richard’s property south of Temple Square, in concert with his brother’s interests, “decided to move the graves to the [family] lot in the City Cemetery.” [31] The Journal History of the Church confirms that “the remains of the late Willard Richards and others were removed from the family burial ground, east of the Deseret Museum, in [downtown] Salt Lake City and placed in the [city] cemetery.” [32] Alice Ann Richards, daughter of Willard Richards, recorded, “We had a family cemetery in our lot in an oak grove, and Aunt Sarah [Sarah Longstroth Richards] was buried there with father [Willard Richards] and other members of our family. Uncle George [Longstroth] and Uncle Moses [Whitaker] were buried in a corner of grandma’s lot. The graves were all well taken care of and the ground beautiful with walks, grass and flowers.” [33]

Smith Family Cemetery. Two lots facing West Temple Street belonged to pioneer leaders John Smith and his son, George A. Smith. This area was the home of George’s son John Henry Smith, who later became an Apostle, and the birthplace of George Albert Smith. Today the site is home to the Church History Museum, an original pioneer log home, and the Family History Library. In 1856, Elder George A. Smith petitioned the city council to allow his father and mother to remain where they were buried. On April 19, 1856, the petition was granted. [34]

Other Cemeteries

Fort Douglas Military Cemetery. Camp Douglas, which was later named Fort Douglas, was a military encampment established by General Patrick Edward Connor and the California Volunteers on the east bench of Salt Lake City in October 1862. [35] The southeast corner of the property claimed by the military was reserved for a cemetery, and the first grave was prepared in January 1863. Many of the burials were soldiers who died in skirmishes with Native Americans. At least sixteen soldiers and officers of the California Volunteers who died in armed conflict are interred there. [36] The cemetery’s most famous inhabitant is General Connor himself. [37]

Mount Olivet Cemetery. General Connor also established another Salt Lake City cemetery, although not specifically for the military. “Under the leadership of Connor and Episcopalian Bishop Daniel S. Tuttle, non-LDS residents of Salt Lake City pushed for the establishment of a separate cemetery to serve the needs of those not associated with the LDS Church.” [38] Although the Salt Lake Cemetery was a municipal burial site, Connor felt it was important to provide an alternate choice for burying the dead. The Mount Olivet Cemetery was established in 1874 and remains the “only public cemetery in the United States established by an act of Congress.” [39]

A forty-acre plot of what was originally the military reserve was “to be maintained forever and in perpetuity.” The first burial on site of the new facility came before the government finalized the transaction, and “Emily Pearsall, an Episcopalian missionary who had worked in Utah for two years was buried there in 1872.” [40] The next burial did not occur until 1877.

Through the intervening decades, significant improvements have been made at this site, and today it is an attractive, gardenlike setting. Ironically, there are quite a few Latter-day Saints buried in the Mount Olivet facility, as evidenced by etchings on tombstones and information regarding Latter-day Saint temple ordinances. Rather than an attempt at religious segregation, as originally planned, today the cemetery is more representative of a financial segregation and caters to the needs of wealthier families.

Recent Discoveries

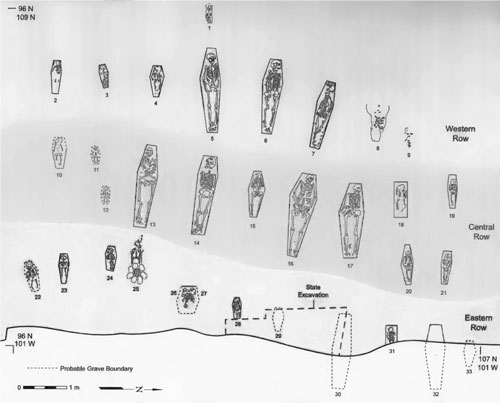

In 1986, 139 years after Milton Therlkill, Caroline Grant, and others were buried, a construction company was digging up the ground near the old pioneer fort in preparation for building of an apartment complex. It was known that there were graves in the vicinity, but the knowledge of their exact location had been lost for more than one hundred years. During the construction process, [41] the remains of several individuals were unearthed. Construction was halted while a more careful examination could proceed. Ultimately, thirty-three graves [42] were found in the area, including what was believed to be the remains of early settlers, both male and female, young and old, Caucasian and Native American. “A total of thirty-four human burials were recovered from Block 49. All but one of these burials dated to the historic use of the early burial ground between 1847–56.” [43] The single exception was judged to be the remains of Native Americans, which were returned to the Paiute Tribal Council for a ceremonial reburial.

Multiple studies were made by the Brigham Young University Anthropology Department on many of the remains. The site was painstakingly studied before the remains were exhumed. Grave sites were mapped and charted, and countless measurements were taken. The work of exhuming the remains was conducted with the help of numerous volunteers, including college students, descendants of some those believed to be buried in the area, and individuals who heard of the dig and wanted to be involved.

The remains of the deceased were individually encased and sent to the University of Wyoming, where George Gill, a forensic archaeologist, tried to identify them. Gill applauded the BYU archaeologists “for doing an outstanding job removing and preserving the bones.” [44] Gill and his staff studied to estimate age, gender, stature, cause of death, and background. This data was recorded and compared with historical information from early Salt Lake City burials. Gill was able to determine that “most of the bodies were those of children . . . [including] eight adults, one adolescent and 24 children.” At least five “were related, to at least a cousin relationship.” [45] Many of the remains were identified with a high degree of accuracy, while the identity of others is less clear. Among those identified were Milton Howard Therlkill and Carolina Van Dyke Grant.

It was debated whether the bodies should be reburied in the Salt Lake City Cemetery or kept together somewhere else. The latter option was chosen, and they were buried in Pioneer Trails State Park in a re-creation of a pioneer village overlooking Salt Lake City known as Old Deseret. The park is located on the east side of Salt Lake City near the “This Is the Place” monument. The remains were buried in coffins built by the carpenter at Old Deseret, and those coffins were enclosed in six large, donated burial vaults. [46]

The Old Deseret Cemetery recreates the original configuration of the downtown burial ground (see fig. 1). [47] None of the headstones marking the graves have epitaphs or other writing, presumably because not all of the remains have been identified. A memorial stone nearby reads, “As the identity of most of these graves remains unknown, this memorial has been dedicated to the memory of all pioneer children who died and who, like those whose bodies lie here, should not go unremembered.” [48] The headstones for the adults are larger, and those marking the grave of children are smaller.

The site was dedicated by President Thomas S. Monson in a ceremony on Memorial Day in 1987 at This Is the Place Heritage Park to rebury the individuals and dedicate the site. There were musical numbers representatives from most of the families whose ancestors were being reburied, and dozens of guests, many of whom helped to exhume, identify, and study the remains. As with the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, President Monson said that part of him “hoped not all the remains would be identified with certainty, allowing every Utahn to believe that one of the bodies may be that of his or her own ancestor.” [49]

As Dr. Lyon noted, “The Mormon people placed great value on human life.” [50] The pioneers spent significant time welcoming the newborn as well as reverencing the departure of the dying, and, when possible, took great pains to prepare the grave site against molestation from man or beast. This, in addition to the heroics of transcontinental migration, is a significant part of the Latter-day Saint legacy in the colonization of the West.

Fig. 1. Organization of pioneer graves, burial layout on Block 49, one block east of the original pioneer fort. Adapted from Richard K. Talbot, Lane D. Richins, and Shane A. Baker, The Right Place: Fremont and Early Pioneer Archeology in Salt Lake City (Provo, UT: Office of Public Archeology, Brigham Young University, 2004), 105.

Fig. 1. Organization of pioneer graves, burial layout on Block 49, one block east of the original pioneer fort. Adapted from Richard K. Talbot, Lane D. Richins, and Shane A. Baker, The Right Place: Fremont and Early Pioneer Archeology in Salt Lake City (Provo, UT: Office of Public Archeology, Brigham Young University, 2004), 105.

Gravesites of Church Presidents

On a lighter note, for years I have taken Church history students on field trips in conjunction with our classes, believing that seeing the sites we discussed in class can help imprint the history lessons into their lives. It takes a full day, from before dawn until nearly dark, and we visit many different sites. We cannot visit all there is to see, but one consistent attraction is the Salt Lake City Cemetery.

We visit the graves of many notables who have passed to their reward. Favorites include Orrin Porter Rockwell, Mary Fielding Smith, Karl G. Maeser, and many others. There always seems to be particular interest in the grave sites of the Presidents of the Church. The Salt Lake City Cemetery contains a wealth of history waiting to be shared. Every tombstone has its own story, and some have many stories. Even the sites of less prominent individuals hold a fascination for inquiring students.

Before arriving at the cemetery or going to the gravesites, I begin with a little discussion and a few questions. I ask, for example, how many Church Presidents have there been in this dispensation. This they know, but then I will ask a loaded question, How many of the prophets are buried in the Salt Lake City Cemetery?

Many will know that the Prophet Joseph Smith was buried in Nauvoo, Illinois, along with other family members. Quite a few students will realize that President Young was buried in his own cemetery in downtown Salt Lake City. Most do not know where his private cemetery is until we visit it as a class. Fewer still know that President Lorenzo Snow was buried in Brigham City, Utah, because he lived there many years. Some of the students know that President Ezra Taft Benson is buried in Whitney, Idaho. Some of the older students remember the funeral procession to the family burial plot.

The place where I am able to catch most students, however, is when they are able to account for all but one of the prophets. With rare exception, they are stumped until they are reminded that the current prophet was included in our count, and he is not yet buried!

After we have accounted for all the prophets of this dispensation, we then know whose graves we might find. The students delight in seeing the graves. Some seem to pay their quiet respects to the Presidents and what they accomplished. Others enjoy learning more about their lives. But invariably there seems to be a connection made, a reverence for the Presidents in the wake of their service.

The students typically want to take pictures, write in notebooks, or pause in thought. I try not to hurry them unduly, but neither do we linger too long because of many other things to see. But the students always seem to be a little more subdued, both at the gravesites and immediately after our departure. As the Prophet Joseph Smith taught, there seems to be a serenity, a realization that the final resting place is sacred—a place of peace, a place set apart from the world where time hesitates for a few moments. Below is a chart showing the final resting places of each latter-day prophet buried, along with coordinates to locate their grave sites.

The grave site of President Brigham Young is located just east of Temple Square in Salt Lake City. (Courtesy of Scott C. Esplin.)

The grave site of President Brigham Young is located just east of Temple Square in Salt Lake City. (Courtesy of Scott C. Esplin.)

|

Church President |

Date of Birth |

Place of Birth |

Date of Death |

Place of Death |

Burial date |

Place |

Burial reference (plat/ |

|

1. Joseph Smith |

23 Dec 1805 |

Sharon, VT |

27 Jun 1844 |

Carthage, IL |

29 Jun 1844 |

Smith Fam. Cem., Nauvoo, IL (SW of Smith Homestead) |

|

|

2. Brigham Young |

1 Jun 1801 |

Whitingham, VT |

29 Aug 1877 |

Salt Lake City |

2 Sep 1877 |

B. Young Memorial Cem., SLC SE corner) |

|

|

3. John Taylor |

1 Nov 1808 |

Milnthorpe, England |

25 Jul 1887 |

Kaysville, UT |

29 Jul 1877 |

SLC Cemetery |

F-11-9-2E |

|

4. Wilford Woodruff |

1 Mar 1807 |

Farmington, CT |

2 Sep 1898 |

San Francisco |

8 Sep 1898 |

SLC Cemetery |

C-6-10-1E |

|

5. Lorenzo Snow |

3 Apr 1814 |

Mantua, OH |

10 Oct 1901 |

Salt Lake City |

13 Oct 1901 |

Brigham City Cem. |

B-16-58-5 |

|

6. Joseph Fielding Smith |

13 Nov 1838 |

Far West, MO |

19 Nov 1918 |

Salt Lake City |

22 Nov 1918 |

SLC Cemetery |

Park-14-12-2E |

|

7. Heber Jeddy Grant |

22 Nov 1856 |

Salt Lake City |

14 May 1945 |

Salt Lake City |

18 May 1945 |

SLC Cemetery |

N-2-1-2E |

|

8. George Albert Smith |

4 Apr 1870 |

Salt Lake City |

4 Apr 1951 |

Salt Lake City |

7 Apr 1951 |

SLC Cemetery |

I-5-15-1-E |

|

9. David Oman McKay |

8 Sep 1873 |

Huntsville, UT |

18 Jan 1970 |

Salt Lake City |

22 Jan 1970 |

SLC Cemetery |

West-3-79-1W |

|

10. Joseph Fielding Smith |

19 Jul 1876 |

Salt Lake City |

2 Jul 1972 |

Salt Lake City |

6 Jul 1972 |

SLC Cemetery |

Park-14-14-1E |

|

11. Harold Bingham Lee |

28 Mar 1899 |

Clifton, ID |

26 Dec 1973 |

Salt Lake City |

29 Dec 1973 |

SLC Cemetery |

West-6-76-1E |

|

12. Spencer Woolley Kimball |

28 Mar 1895 |

Salt Lake City |

5 Nov 1985 |

Salt Lake City |

9 Nov 1985 |

SLC Cemetery |

West-13-44-3W |

|

13. Ezra Taft Benson |

4 Aug 1899 |

Whitney, ID |

30 May 1994 |

Salt Lake City |

4 Jun 1994 |

Whitney, ID |

4-4-31 |

|

14. Howard William Hunter |

14 Nov 1906 |

Boise, ID |

3 Mar 1995 |

Salt Lake City |

3 Mar 1995 |

SLC Cemetery |

West-12-36-3E |

|

15. Gordon Bitner Hinckley |

23 Jun 1910 |

Salt Lake City |

27 Jan 2008 |

Salt Lake City |

3 Feb 2008 |

SLC Cemetery |

West-3-178-2W |

Notes

Special recognition and appreciation are extended to Randall Dixon of the Church History Department for his work in collecting information on early Latter-day Saint burials and for his gracious willingness to share parts of his research.

[1] T. Edgar Lyon, “Some Uncommon Aspects of the Mormon Migration,” Improvement Era, September 1969, 33–40.

[2] Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, comp. Joseph Fielding Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1976), 294–95.

[3] Many early burial grounds were created “in an ad hoc manner primarily in response to the immediate needs of the very first pioneers after their arrival in the summer of 1847.” Burial grounds are typically not “formally designated or consecrated as a cemetery.” Richard K. Talbot, Lane D. Richins, and Shane A. Baker, The Right Place: Fremont and Early Pioneer Archaeology in Salt Lake City (Provo, UT: Office of Public Archaeology, Brigham Young University, 2004), 83–84.

[4] Robert Crow, grandfather of Milton Therlkill, owned the plot of ground. Journal of Horace K. Whitney, August 12, 1847, Church History Library. Apparently, the Crows were allowed to bury their grandson in this area because of the accident, the family’s grief, the neighbors’ desire to assist in a time of need, and availability of the vacant lot.

[5] Gene A. Sessions, Mormon Thunder: A Documentary History of Jedediah Morgan Grant, (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1982), 59.

[6] Sessions, Mormon Thunder, 62.

[7] Jacob Gates Journal, in the Mormon Pioneer Overland Travel database, 1847–68, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

[8] Sessions, Mormon Thunder, 64.

[9] Sessions, Mormon Thunder, 68.

[10] Sessions, Mormon Thunder, 68.

[11] The Mormon Pioneer Overland Travel database identifies that they arrived on September 25, 26, and 29, which suggests that they, like other companies, were strung out by the time they reached the Salt Lake Valley; http://

[12] Andrew Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia (Salt Lake City: Andrew Jenson, 1901), 1:291.

[13] Kate B. Carter, comp., Heart Throbs of the West: A Unique Volume Treating Definite Subjects of Western History (Salt Lake City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1943), 6:326.

[14] Carter, Heart Throbs, 6:326.

[15] “Salt Lake City Cemetery History,” a fact sheet provided by sexton Mark E. Smith and distributed from his office at the cemetery.

[16] Susan Lyman, “A Walk Through Time: Salt Lake Cemetery Is Filled with History, Drama,” Deseret News, May 29, 1988, S1.

[17] “Salt Lake City Cemetery History.”

[18] On January 28, 1862, Baptiste was taken “to the graveyard to day to point out the graves which He had opened. . . . He did not point out more than a doz[en] Graves . . . for fear he would be killed.” Elder Woodruff continued, “I would probably range [estimate] from One to three Hundred.” Wilford Woodruff Journal, 1833–1898, Typescript, ed. Scott G. Kenney (Midvale, UT: Signature Books, 1983), 6:14.

[19] Carter, Heart Throbs, 6:328–29.

[20] Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 6:14–15 (July 28, 1862). Baptiste was banished to Miller Island (later Fremont Island), which was being grazed by livestock owned by a Miller family. David E. Miller, “Footnote to History: The Man Who Was Banished,” Home Magazine, April 15, 1956, H3; see also “Affairs in Utah,” New York Times, February 28, 1862, 3.

[21] Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 6:13 (January 27, 1862).

[22] Carter, Heart Throbs, 6:326.

[23] “First Cemetery in the Salt Lake Valley, 1847–48 (Also the Kimball-Whitney and Brigham Young Private Cemeteries),” Heritage Gateways, http://

[24] When Heber C. Kimball died in June 1868, he was buried near his family in the same plot as were his wives Vilate Murray, Laura Pitkin, Sarah Noon, Sarah Ann Whitney, Anna Gheen, Ellen Sanders, and Theresa Morley. See Orson F. Whitney, “The Kimball Cemetery,” Deseret Evening News, June 14, 1890. His wife Ellen Sanders was one of the first three women to enter the Salt Lake Valley. At the turn of the century, a newspaper column noted, “A beautiful pine tree today grows over [Kimball’s] exact sleeping place, while around him are the bodies of several of his wives and friends.” See “The Kimball-Whitney Cemetery,” Deseret Evening News, June 15, 1901.

[25] Carter, Heart Throbs, 6:334.

[26] Carter, Heart Throbs, 6:334–35. The proceeds from the sale of Elder Orson F. Whitney’s Life of Heber C. Kimball, “which have been extensive,” were used to make significant improvements to the cemetery. Orson F. Whitney, “The Kimball Cemetery.”

[27] “First Cemetery in the Salt Lake Valley, 1847–48.”

[28] “Some Not-So-Common Sites to See around Temple Square,” Mormon Times, Saturday, May 15, 2010, 11.

[29] Carter, Heart Throbs, 6:334.

[30] Carter, Heart Throbs, 6:333.

[31] Carter, Heart Throbs, 6:335.

[32] Journal History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, March 29, 1890, 3.

[33] Alice Richards Smith, The Living Words of Alice Ann Richards Smith (n.p.), 5, Leonard J. Arrington Historical Archives, Utah State University, Logan, Utah.

[34] Great Salt Lake City Council Minutes, April 19, 1856, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, MS 8623 reel 35.

[35] For additional information about the establishment of Camp Douglas, see Kenneth L. Alford’s chapter in this volume.

[36] Talbot, Richins, and Baker, Right Place, 89.

[37] After completing his military service, General Connor returned to Salt Lake to become a prospector and a self-appointed reformer, whose goal was to dilute the authority of the Latter-day Saints and create interest for non-Mormons to reside in Utah.

[38] Talbot, Richins, and Baker, Right Place, 89.

[39] Talbot,Richins, and Baker, Right Place, 89.

[40] Talbot, Richins, and Baker,Right Place, 89–90.

[41] The discovery was by chance, because only the year before a company from Colorado was hired to find the burial ground established by the earliest pioneers to the Salt Lake Valley. Thousands of dollars and many days were spent searching for the burial sites without success. It was a year later, and after construction on the site had resumed, that an antique bottle collector looking for pioneer artifacts found some bones. Chuck Gates, “Discovery of Graves Culminates a Search for ‘Roots,’” Deseret News, March 8, 1987, B2.

[42] Talbot, Richins, and Baker, Right Place, 103. “The 33 historic burials . . . were distributed across an area approximately ten meters east to west and eleven meters north to south (110 sq. meters).” In total, “32 graves containing human remains, and two other possible graves which contained no skeletal material. The discrepancy between the 33 burials and 32 graves is due to the fact that 2 infants were buried in a single grave.” These two were believed to be conjoined twins, connected at the head, seemingly in a state of embrace in death.

[43] Talbot, Richins, and Baker, Right Place, 103.

[44] Gates, “Discovery of Graves Culminates a Search for ‘Roots,’” B2.

[45] Conrad Walters, “Pioneers’ Bones Are Back for Reburial,” Salt Lake Tribune, April 17, 1987.

[46] Chuck Gates, “State Park Preparing to Rebury 32 Pioneers,” Deseret News, April 17, 1987, B1–B2. The vaults were used in case additional studies need to be performed on the skeletal remains. There is always a chance that new tests, procedures, or science could be developed that would help to prove the identify of yet-unidentified individuals or to further study the remains.

[47] This is why the original layout of the original cemetery on Block 49 where the skeletal remains were exhumed became so important.

[48] Personal observation during a visit to “This Is the Place” State Heritage Park, June 2010.

[49] Phoenix Roberts, “Utah’s Tomb of the Unknowns: Discovering a Lost Cemetery,” Salt Lake Magazine, June 2004, 50. Only nine out of the thirty-three were positively identified, and several others were identified with some question of absolute certainty. Most of those individuals without an exact identity were infants, but for some of the twenty-four a surname was known. In addition, with the identities fixed, another monument was erected in downtown Salt Lake City. The monument is located at the intersection of 200 West and 300 South in Salt Lake City on the southwest corner of the intersection and the northeast corner of Block 49. This is the closest point to the burials on public property that the monument could be affixed.

[50] Lyon, Uncommon Aspects, 40.