Historical Highlights of LDS Family Services

John P. Livingstone

John P. Livingstone, “Historical Highlights of LDS Family Services,” in Salt Lake City: The Place Which God Prepared, ed. Scott C. Esplin and Kenneth L. Alford (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, Salt Lake City, 2011), 285–304.

John P. Livingstone is an associate professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University.

Walking north on State Street in downtown Salt Lake City a block and a half southeast of Temple Square, one comes to the remodeled Promised Valley Playhouse. Not only has the exterior of the old playhouse been cleaned and refurbished, the interior has also been changed dramatically. Where families used to enter for entertainment, they now enter for edification. The former playhouse now houses the world headquarters of LDS Family Services.

Just as pioneer trails changed from wagon roads to gravel thoroughfares to asphalt highways and finally to modern high-speed freeways, LDS Family Services has grown from humble beginnings into a major resource for priesthood leaders and members alike. The organization is now set to move forward internationally in order to bless Latter-day Saints all over the world much as it has in North America.

As Salt Lake City grew into a cosmopolitan center at the latter end of the nineteenth century, social problems already common in other large American cities began to emerge. Out-of-wedlock pregnancy, family violence, various forms of abuse, and criminal activity, to name a few, tested the mettle of civic and Church leaders. These problems underscored the need for some kind of organized effort that would help individuals and families battle some of mankind’s oldest ailments. By the end of World War I, Church leaders recognized a need for technical assistance with these social ills. The lay leadership of the Church came from all walks of life and voluntarily served Church members who brought issues and challenges to their ecclesiastical doors. While the vast majority of these problems could be solved in the office or home of a dedicated bishop who, more often than not, left his work in the field, the shop, or the office to listen and counsel as directed by spiritual promptings, some difficulties required time and resources not readily available to him. This need resulted in the organization of what is known today as LDS Family Services.

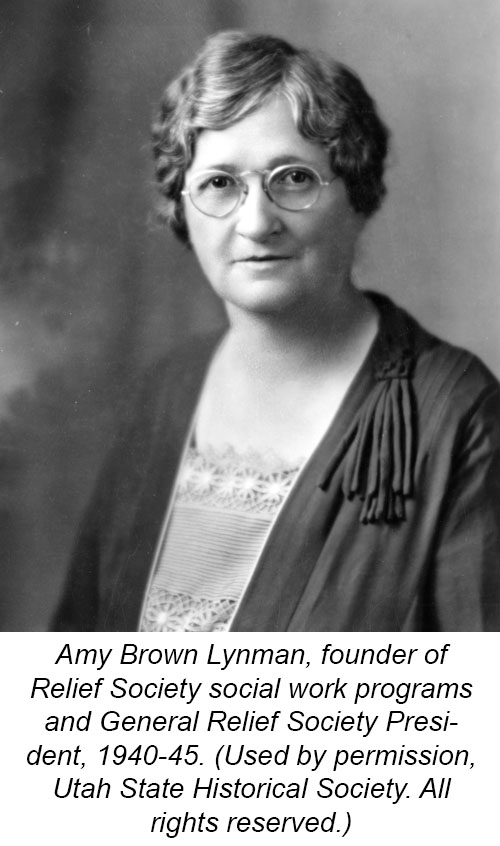

The history of LDS Family Services parallels the history of social work as it evolved in the United States. Amy Brown Lyman, who in 1940 became the eighth general Relief Society president, was familiar with social work. In the early 1900s, while her husband, Richard Lyman (who later served as an apostle), attended the University of Chicago, Amy Brown Lyman took social work classes that introduced her to the famous Hull House in Chicago. She was deeply impressed with the efforts of social work pioneer Jane Addams, the primary force behind the Hull House, where university students and other visitors could interact with troubled individuals or families to try to help them to work their way out of life’s problems, and came away determined to help the needy back home in Utah. Indeed, this kind of social work, seemed to typify true New Testament Christian living to both Jane Addams and Amy Lyman.

This article is a descriptive study and overview of the growth and development of LDS Family Services since its beginning within the Relief Society and subsequently under several commissioners (all of whom are still living). Major participants in the organization as well as almost all of the commissioners were interviewed regarding their particular era.

The Pioneer Trail: Relief Society Gives Birth to Social Services

Amy Lyman’s short internship at the Hull House gave her ideas regarding how significant social ills might be approached and hoped that they could be rectified in a measured, organized fashion. Her subsequent call to the Relief Society General Board facilitated the creation of a social services department within the Relief Society. In 1917, Utah governor Simon Bamberger asked Sister Lyman to attend the National Conference of Charities and Corrections as an official delegate to help Utah families displaced by World War I. At a follow-up six-week course in Denver, several Utah women receiving an intense institute, or seminar, laid the foundation for the development of social work in Utah. The instructors taught that “the principal values and methods of charity organizations were 1) rehabilitation through diagnosis and case treatment of families in need; 2) education of the public in correct principles of social welfare work and cooperation; and 3) gathering evidence through the first two principles and establishing volunteer networks to eliminate the causes of poverty and dependence.” [1]

Utilizing what they had learned in Denver, these Relief Society women, in conjunction with the Red Cross, went about establishing social services organizations in several Utah cities. Sister Lyman took responsibility for following up with families assisted through the Red Cross that identified themselves as Latter-day Saints. She later met with President Joseph F. Smith who suggested that she head up a social services department within the Relief Society. After returning to Denver for additional training, Sister Lyman established the Relief Society Social Services Department in January 1919. President Joseph F. Smith had passed away in November 1918 and was succeeded by Heber J. Grant. [2] Sister Lyman taught a six-week summer course on social services in 1920 in Aspen Grove, Utah. Sixty-five stakes (representing 78 percent of the Church) sent sisters to receive social work training at the event. The following year, the Relief Society began holding social service institutes to train local Relief Society women in family welfare work. [3] Over four thousand sisters received training to become “stake social service aids.” [4] Additional Relief Society Social Service Department branch offices, staffed by professional social workers, were soon created in Los Angeles in 1934 and also in Ogden in 1940 to meet family welfare needs. Social services efforts, though, were primarily seen by many as a women’s program.

An important supplement to social services work began in 1954 when the Indian Student Placement Program was formally initiated. That year, so many Indian children were placed in Latter-day Saint foster homes that it caught the attention of John Farr Larson, director of the Utah Department of Public Welfare, who “indicated his concern inasmuch as there was a law which required children placed for foster care to be placed through a licensed agency.” [5] Not many records were kept of the earliest efforts, but in 1957 Elder Mark E. Petersen invited Clarence R. Bishop to meet with Elder Spencer W. Kimball, who headed the Lamanite Committee of the Church. [6] Because the Relief Society Social Services Department was licensed with the State of Utah, Indian Placement headed by Bishop, was placed under its auspices and formal home evaluations were carried out for students arriving from the reservations. The Indian Placement Program burgeoned from the basement of the new Relief Society Building in the mid 1950s. [7]

In 1956, the Relief Society Social Services Department added a Youth Guidance Program which was instigated to help troubled teens and children. [8] In the sixties, Allen J. Proctor was hired within the Youth Guidance Program to help with youth “camps.” He told of initial youth groups meeting in the basement of the Relief Society building near the Salt Lake Temple. They were a lively and somewhat rough group of boys (referred to as delinquents) to be in such a stately new building. On one occasion, a young man escaped from the group, only to be brought back by the scruff of his neck by none other than general Relief Society president Belle Spafford. It was shortly after this incident that the youth groups were moved to the old Veteran’s Hospital on 12th Avenue and E Street in Salt Lake City, where they had a beautiful view of the valley while they participated in therapy. [9] As these programs expanded, more Relief Society Social Services Department offices were opened in Phoenix and Las Vegas in 1962 and 1965 respectively.

Sister Spafford was a strong supporter of social work, especially while it was under the direction and responsibility of the Relief Society. Shortly after the establishment of the Brigham Young University law school, she remarked in a monthly meeting with social services workers, “Ernest Wilkinson got his law school, and I’m going to get my social work school . . . whatever it takes!” [10] Shortly afterward, it was announced that Brigham Young University would start a social work school.

The Trail Becomes a Road: LDS Social Services under Priesthood Direction

In 1969, due to the Church correlation movement, a decision was made to bring the social services efforts under priesthood direction. Unified Social Services took all aspects of social services from the Relief Society. Elder Marvin J. Ashton said: “I was called in September 1969 to act as managing director for the Social Services program. The First Presidency at that time directed that President Spencer W. Kimball, Acting President of the Council of the Twelve, Elder Thomas S. Monson of the Council of the Twelve, Presiding Bishop John H. Vandenberg, and Sister Belle S. Spafford, president of the Relief Society, form an advisory committee, with Elder Marion G. Romney of the Council of the Twelve as chairman. This committee provides me with help in guiding the program.” [11]

Victor L. Brown Jr. became the first director (later commissioner) of the new social services entity. [12] In 1971, Social Services and Health Services were placed under the auspices of the Presiding Bishopric, and Unified Social Services was changed to LDS Social Services. Commissioner Brown shepherded LDS Social Services through years when some members and leaders wondered whether or not there was a real need for professional counseling and other services when they felt most issues could be handled by local bishops. Bishop J. Richard Clarke clarified the role of LDS Social Services when he said,

The purpose or mission of LDS Social Services is to assist priesthood leaders by providing quality licensed and clinical services to members of the Church. This is accomplished by using highly qualified staff members and volunteers whose values, knowledge, and professional skills are in harmony with the gospel and the order of the Church. We should remember that LDS Social Services exists . . . because our prophets were inspired to give local priesthood leaders a resource to meet social-emotional needs.

Bishop Clarke also quoted from the current Welfare Services Handbook:

The bishop and Melchizedek Priesthood quorum and group leaders are the Lord’s ecclesiastical leaders. They cannot and must not abdicate their responsibility to any agency. Social services agencies are established to be a resource to the ecclesiastical leaders. There is no substitute for the inspired counsel and priesthood blessing by the bishop or quorum or group leader. [13]

In 1973, Church leaders saw the wisdom of making LDS Social Services a separate corporate entity from the Church. Human problems being what they were, it was only natural that some legal issues arose which made the creation of a separate corporation a wise move. This choice protected the financial resources of the Church, the workload of Church leaders, and allowed worldwide membership to grow unhindered by the possibility of lawsuits that would require inordinate use of Church funds.

The period between 1969 and 1976 became a unification period for LDS Social Services. Bringing together and organizing the three main branches of the Church’s social services efforts—Adoption, Youth Guidance, and Indian Placement—necessarily meant trying to join efforts, programs, and personalities that were originally very independent. It took some effort to figure things out and determine responsibilities. The three main facets of Church social services merged into one organization to help ecclesiastical leaders and members deal with serious human problems in clinically appropriate ways. Skilled professionals helped priesthood leaders by assisting with issues beyond the scope and time constraints of most lay leaders.

The Road Widens: Social Services Encircled by Church Welfare

Harold C. Brown succeeded Victor Brown as commissioner of LDS Social Services in the fall of 1976 and served in that capacity until 1981. [14] Victor went on to work for Brigham Young University and helped establish the Comprehensive Clinic. This clinic offered counseling services to the community at discounted rates by employing graduate students from the various Brigham Young University mental health programs who worked under their professors’ supervision. [15]

Early in his career, Harold was assigned to develop and upgrade policies and procedures for case workers, and in 1973 he was promoted to coordinate all licensed service for LDS Social Services. By 1974, he and William E. Bush supervised all of the sixteen agencies under Oliver McPherson, the assistant commissioner under Victor Brown. Harold became commissioner of LDS Social Services in September of 1976. From 1976 to 1981, LDS Social Services was to some extent reintegrated into the administration of Welfare Services. In 1981, Harold left his assignment as commissioner to become the director of field operations under the managing director of Welfare Services. Later, from 1985 to 1996, Harold returned and again served as commissioner of LDS Social Services. His influence would continue when he later became chairman of the Board of Trustees of LDS Family Services while serving as managing director of Church Welfare. The influence of Harold C. Brown’s influence may well be called the most important force in the modern history of LDS Family Services.

The period of 1976 to 1985 represented LDS Social Services taking its rightful place alongside other branches of the Church’s welfare efforts (such as Deseret Industries, Church farms, and bishops’ storehouses). Welfare Services covered all aspects of welfare concerns within the Church in an organized, correlated fashion. It became clear to Church leaders and members that LDS Social Services fit within Welfare Services in a way that made intuitive sense and seemed to indicate divine intervention within Church correlation efforts.

William S. Bush followed Harold Brown as commissioner in 1981 and served for the next two years. [16] Bush was disturbed by accounts of child abuse that seemed to be prevalent in the early 1980s not only among the general public, but among Church members as well. It seemed to him that priesthood leaders needed some support in this area. He began to consider what could be done, especially for women, affected by sexual abuse in their early years. He could also see that the placement program was becoming less and less necessary as an alternative to disappearing boarding schools on reservations throughout the United States and Canada. Though the program would continue throughout his time as commissioner, he could clearly see the end was near. As the Church Educational System (CES) began to reduce their involvement on reservations throughout the country and lose connections with reservation families, the influence of LDS Social Services diminished as well. During Bush’s time as commissioner, adoption services went national, and LDS Social Services was represented on the National Council for Adoption.

Bush was succeeded by Larry L. Whiting in September of 1984. Whiting remembered stepping into this new assignment:

This was a time when child sexual abuse issues were surfacing (even possibly in a few cases with an exaggerated emphasis). Alert bishops were finding that some adult women had been sexually abused as children and young children currently were also suffering from abuse. Somewhat of froth was in the making as increasing numbers of women were being helped by professionals to “remember” abusive activities involving priesthood leaders and satanic perpetrations. Some were encouraged by misguided therapists to “create recollections” . . . where all manner of bizarre activities were allegedly being perpetrated on unsuspecting victims. Needless to say I was skeptical of such stories. [17]

Whiting and his administrative team began to craft a response to these serious issues in an effort to help Church leaders respond to matters such as these. Many laws were being passed around the country requiring citizens and professionals to report abuse cases to authorities. It became necessary for Church leaders to address issues of priest–penitent concern for both the victims and, in some cases, repentant perpetrators. It became clear that Church leaders were greatly benefited by being able to consult with both mental health professionals as well as legal counsel. An abuse help line was established to help local priesthood leaders proceed wisely and within legal limits where necessary. This timely help made a crucial difference for priesthood leaders and helped them offer sensitive and accurate assistance to members. Whiting’s team was also able to print a Churchwide publication discussing abuse.

The Indian Placement Service faded away during Whiting’s service as commissioner. Earlier, an official Church announcement said:

The First Presidency has announced changes that will eventually shape the Indian Student Placement Program into an experience for high-school-age students only.

Beginning with the 1985–86 school year, the program will be limited to students in grades six through twelve, and the entry age will be raised one level each year until the 1988–89 school year, when the program will be limited to those in grades nine through twelve.

The announcement follows a change in 1984 that made only students in grades five through twelve eligible for the program.

“In addition to the age change,” the First Presidency said in a letter to General Authorities and to priesthood leaders in the western United States, “enrollment standards will be raised. Information regarding specific eligibility requirements will be available through LDS Social Services agencies. Current participants, regardless of their age, may continue to participate as long as they meet the higher standards and their parents desire them to continue.

“These changes should not be viewed as a phaseout, but as a refinement of this program. The purpose of these modifications is to provide students with experiences that will promote spirituality, leadership, and academic excellence, and, therefore, strengthen the family, Church, and community.” [18]

Notwithstanding the comment about a “phaseout,” of the Indian Placement Program, it was reduced to the point of elimination later on. Ironically, Clarence R. Bishop, who was involved in some of the earliest days of the formalized Indian Placement Program, was present when arrangements were made regarding activities that would continue until the last students graduated from the program.

Thousands of Native American students had lived in Latter-day Saint homes from the early 1950s through the late 1980s. Most lost their fear of the dominant culture around them, while many Latter-day Saint families lost their fear of minorities. While arrangements were far from perfect, sacrifices were made, learning occurred, and barriers fell. Indian Placement students found employment all over the United States, many in responsible positions on and off their reservations. When the “fade-away” decision was made, Whiting said, “I lost control and wept.” [19] The caseworkers who had supervised the children loved them. Most caseworkers made the transition other areas of the corporation, while some took early retirement. [20]

In 1985, Harold Brown again became the commissioner of LDS Social Services and served for an additional ten years. Policies and procedures were developed that represented a significant coming of age in the preparation of workers helping with the treatment of family and mental health problems. The adoption program was strengthened as well, even though the number of babies available for adoption decreased somewhat.

A very strong refinement and expansion era occurred between 1985 and 1995. Training was always an important element in LDS Social Services. In 1976 there was a major effort to increase the professional skills of staff. Val McMurray was hired to help develop and carry out this training initiative. The updated training after 1985 helped to significantly increase the skills of already competent caseworkers and prepared the way for an effective expansion of LDS Social Services throughout the United States and eventually internationally. [21] During this time there was a strong effort to learn more about common social problems and confront especially difficult issues such as sexual abuse, by focusing on helping those afflicted. A telephone help line for priesthood leaders provided direct consultation with professionals who could help handle challenging personal issues appropriately.

Paving the Road: Social Services become Family Services

In February of 1996, LDS Social Services became LDS Family Services. “This name change will help us emphasize our goal to strengthen families through our adoption and family counseling programs,” said managing director Harold Brown. “The name LDS Family Services is more descriptive of the services we deliver and the philosophy we embrace as we work with ecclesiastical leaders and members. More important, it furthers our focus on helping clients adhere to gospel principles and covenants that pertain to the eternal nature of the family.” [22]

The new title reflected the very personal and family nature of the organization. It underscored the focus on the family that the social workers and other professionals employed by this corporation were supposed to remember. It also mirrored the Church’s strong family message by pointing to the most basic of social units emphasized by modern prophets.

Fred M. Riley, who became the commissioner in 1995, tried to maintain the core values of LDS Family Services while at the same making significant strides in the human resources side of the organization. [23] Many part-time personnel were hired to increase the number of hours of service that could be offered to Church members. Full-time practitioners took supervisory roles over the part-time therapists, which saved money and time and thus augmented Church financial and personnel resources. These part-time personnel participated in distance training via satellite, as did full-time workers. A weekly commissioner’s chat highlighted issues and kept all personnel in touch with the head office in Salt Lake City.

The establishment of addiction recovery groups was a vital help to priesthood leaders and members who struggled to overcome addictions. LDS Family Services arranged with Alcoholics Anonymous to customize their twelve-step material as a basis for a Latter-day Saint addiction recovery program that has grown to help thousands work their way out of addiction. While sobriety was a desired outcome of the program, full Church activation was the goal.

Pornography addiction groups were added later, and they became a helpful weapon against this particularly difficult personal, marriage, and family problem. By 2008, over half of the participants were there to deal with pornography addiction.

Marriage and parenting manuals were also updated. The ongoing abuse help line, booklets, and videos greatly helped priesthood leaders, who could not be expected to be fully conversant in some of these serious problems. An adoptive parent group called Families Supporting Adoption was also organized. It was made up of couples hoping to adopt as well as couples who had already adopted and could serve as mentors to those either going through adoption or hoping to do so in the future. This group may well be the largest of its kind in the world. A website titled “It’s about Love” was created to help promote adoptions services within LDS Family Services. Adoption efforts were further modified to allow a more open relationship between birth mothers and adoptive parents. This allowed birth mothers to play a role in choosing their child’s parents and eventually placing their child in the open arms of eager adoptive parents.

The Internet Highway: Faster, Leaner Services and Technology Enhances

Larry D. Crenshaw became commissioner in April of 2008. [24] Under his leadership, the organization has further increased its worldwide influence by more fully utilizing technology. This technology, rather than an increase in staff, helps deliver services to all Church leaders and members globally. Developing preeminent web-based services to help Church leaders better serve the social-emotional needs of their members is a major focus. For example, the website Combatingpornography.org received thousands of hits through the corporation’s efforts to reach strugglers and their loved ones by making the dangers of pornographic addiction understandable and offering guidelines for successfully overcoming this challenge. Individuals and their loved ones, along with Church leaders, can go online and access speeches, presentations, and scriptures to help them understand and overcome the evil effects of pornography. When fully developed, it will be much more interactive and provide more help. Indeed, using the computer to combat a problem that is usually exacerbated by computer use is a unique strategy for overcoming a very tenacious addiction that afflicts many individuals and families today.

Beginning in January 2008, a Presiding Bishopric study of LDS Family Services provided a broad analysis of the organization—including its strengths and weaknesses. This effort has resulted in several substantial changes to the organization. Some have been implemented already, others will be forthcoming. First, the hierarchy has been significantly flattened. The former director system has been eliminated, and most billing and financial functions have been outsourced to Church headquarters. Today, a new hire out of graduate school begins as a counselor, then becomes a specialist, and, with further certification, may become a supervisor, or field manager. Competency-based training, testing, and compensation would facilitate promotion without requiring employees to be transferred from place to place. The savings from avoiding costly moves for workers and their families makes additional training opportunities possible.

Modern technology has also facilitated audiovisual training from headquarters to any employee with a computer, thus saving travel funds. LDS Family Services will now focus on four core services delivered through personal and web-based methods:

- Ecclesiastical Consultation, providing bishops with 24/

7 consultation services in multiple languages, including online consultation. - Community Resource Development, establishing a network that identifies preferred local providers (mental health professionals cleared by LDSFS) in a database accessible through an Internet portal to Church headquarters.

- Counseling Services, assisting Church leaders, who are the primary source of counseling, by offering counseling mainly to those with social, emotional, or psychological issues that interfere with living gospel principles and covenant keeping.

- Services for Children, helping with adoption, foster care, and birth parent support and related issues. [25]

All bishops and other leaders cannot be expected to have degrees in counseling but can access technical counseling help via phone or the Internet. The Lord has said, “I will hasten my work in its time” (D&C 88:73), and LDS Family Services is helping fulfill that scriptural mandate by addressing serious personal and social problems by assisting Church leaders worldwide.

Perhaps Amy Brown Lyman could not have foreseen the modern training, clinical tools, and technology that are fulfilling her vision of helping with personal and family problems. LDS Family Services has continually branched out, reaching more and more Church members throughout the world. What must have seemed to some priesthood leaders in the early years as a “nice” program has now become an essential tool in the Church, helping thousands who would otherwise remain roadside, disabled by their problems to instead face their issues, overcome their challenges and take a higher road through mortality.

Notes

[1] Loretta L. Hefner, “This Decade Was Different: Relief Society’s Social Services Department, 1919–1929,” Dialogue 15 (Fall 1982): 65.

[2] Hefner, “This Decade Was Different,” 66.

[3] History of Relief Society (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1966), 64.

[4] History of Relief Society, 94. There have been eleven other directors over the Relief Society Social Services Department: Amy W. Evans, Ora W. Chipman, Marie Tanner, Ruth P. Lohmoelder, Elizabeth K. Ryser, Mary Dillman, Lauramay Nebeker Baxter, Margaret Keller, Josephine Scott Patterson, Mayola R. Miltenberger, and Helen H. Evans. Josephine Scott Patterson, “Social Services in the LDS Church as I Have Known Them from 1955 through 1974,” around 1974, 3, Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City.

[5] Patterson, “Social Services in the LDS Church,” 5.

[6] Clarence R. Bishop, interview by author, September 10, 2010, Salt Lake City.

[7] Bishop interview.

[8] Patterson, “Social Services in the LDS Church,” 13–14. An initial youth guidance advisory committee was organized with Spencer W. Kimball as chairman and Alvin R. Dyer, Bishop Robert L. Simpson, President Belle S. Spafford, and Sister Florence Jacobsen as members. Thomas S. Monson was added to the committee later. Youth guidance was then made a division of LDS Family Services in 1964, with Charlie Stewart as executive director. The program was moved to 50 Richards Street and then to Old Veteran’s Hospital on Twelfth Avenue and E Street in 1966.

[9] Allen J. Proctor, interview by author, September 10, 2010, Salt Lake City.

[10] Proctor, interview.

[11] “When You Need Help,” New Era, March 1971, 4.

[12] Victor L. Brown Jr. had formerly served in the Nevada agency of the Relief Society Social Services Department. Clarence R. Bishop had been responsible for the Indian Placement Program and Charlie Stewart supervised the Youth Guidance Program. Victor Brown’s administration would serve from David O. McKay’s presidency in 1969 until Ezra Taft Benson’s.

[13] J. Richard Clarke, “Ministering to Needs through LDS Social Services,” Ensign, May 1977, 85.

[14] As a young missionary, Harold Brown had served in the northern division of the Southwest Indian Mission beginning in November 1962, before the creation of the Northern Indian Mission in 1964. President Spencer W. Kimball visited that mission often and encouraged the missionaries to consider working with “Lamanites” after their missions if they were so inclined. Harold found employment with the Church Educational System teaching seminary to Native American students in Brigham City, Utah for a short time, and then was invited by Clarence R. Bishop to join the Indian Placement Program as a local worker from January 1969 to June 1970 in Preston, Idaho. At the latter end of this assignment, he was assigned to go to Bismarck, North Dakota, to see if help could be offered to Native Americans on their reservations as opposed to interacting with students primarily in their foster homes. This effort became the precursor for Indian Placement offices to be opened in Rapid City, South Dakota, and Chinle, Arizona. One day, someone said to him, “Did you know you are a social worker?” That label had not occurred to him, but when he was transferred to Salt Lake City in June 1970, while still working full time, he began graduate school in social work, finishing a master’s degree in 1972. By the time he finished his master of social work degree, Harold was also responsible for the Indian Placement Program in Utah. He also worked later with urban Native Americans with Stewart Durrant, who served with the Lamanite committee, trying to create walk-in centers where Native Americans could access Church social services.

[15] Initially, this clinic was to fall under the direction of the commissioner of LDS Social Services, but by 1981, it seemed apparent that the clinic might be better administered by Brigham Young University educators.

[16] William S. Bush had come from a small town in Idaho, where he herded sheep as a teenager, and worked his way through Brigham Young University and the University of Utah. He began employment with Relief Society Social Services Department on June 10, 1963. He had not yet finished his bachelor’s degree, but was hired with the proviso that he would finish his degree soon after beginning as a caseworker with the Indian Student Placement Program. It seems that the early placement caseworkers loved serving among Native Americans and became a very cohesive group within LDS Social Services. In the early 1970s, Bush served as the very first assistant commissioner under Victor L. Brown as commissioner and Glen VanWagonen as associate commissioner. This new system of associate and assistant commissioners ended a system of division directors in which certain agency directors were designated as supervisors over the rest of the agency directors and were known as division directors. Bush was serving as a division director from the Phoenix agency when he was called to move to Salt Lake City to become the assistant commissioner.

[17] Larry L. Whiting, “A Few Thoughts from Personal History of Larry L. Whiting While Serving as Commissioner of LDS Social Services” (unpublished manuscript in author’s possession, 2010), 1.

[18] “Indian Placement Modified,” Ensign, February 1985, 80.

[19] Whiting, “A Few Thoughts,” 5.

[20] Larry L. Whiting currently serves on the Board of Trustees of LDS Family Services.

[21] Patterson, “Social Services in the LDS Church,” 20. A Refinements Committee had been organized in 1973 with Art Finch, Juel Gregerson, and Brent Frazier. It was later enlarged and became the Planning and Training Committee (developing training materials) and was further enlarged to include William Bush and Rollin Davis. Eventually, Harold C. Brown, Victor L. Brown Jr., Glen E. VanWagenen, Lynn Marriott, and Charles Woodworth were added with Bill Bush serving as chairman.

[22] “Policies and Announcements,” Ensign, February 2000, 80.

[23] Fred M. Riley joined LDS Social Services in Denver in February 1979, serving there for six years until the spring of 1985, when he was asked to move to Seattle to become the director of that office. In 1990 he became an assistant commissioner of the corporation, but remained in the Seattle area. About a year later, the Riley’s moved to Salt Lake City. He became the commissioner five years later.

[24] Larry D. Crenshaw was a Kentucky-born-and-raised descendant of Daniel Boone. His family joined the Church when he was a young man and he later served a mission in Denmark. He had received a master’s degree from the Kent School of Social Work at the University of Louisville. He began work with LDS Family Services in Chicago, then was moved to Florida and ultimately to Utah.

[25] Larry D. Crenshaw, interview by author, September 29, 2010, Provo, UT.