Ensign Peak

Dennis A. Wright and Rebekah E. Westrup

Dennis A. Wright and Rebekah E. Westrup, “Ensign Peak: A Historical Review,” in Salt Lake City: The Place Which God Prepared, ed. Scott C. Esplin and Kenneth L. Alford (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, Salt Lake City, 2011), 27–46.

Dennis A. Wright was a professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University when this was published. Rebekah E. Westrup is a humanities major at Brigham Young University who participated in this project as a mentored research assistant.

A view of Ensign Peak from the south. (Courtesy of David M. Whitchurch.)

A view of Ensign Peak from the south. (Courtesy of David M. Whitchurch.)

From the time the pioneers first entered the Salt Lake Valley until the present, Ensign Peak has received recognition beyond its geological importance. The peak is best described as an undistinguished hill, rising over a thousand feet from the northern edge of the Salt Lake Valley, approximately one mile north of the Utah State Capitol Building.[1] While unremarkable in most ways, the peak has received attention from community and religious leaders because of its historical importance. This discussion summarizes selected events in the history of Ensign Peak, from 1843 to the present, to help readers better understand and appreciate its significance.

The pioneer history of the peak began three years before the arrival of the Mormons in the Salt Lake Valley in July 1847. George A. Smith, a counselor to President Brigham Young, described how President Young first saw Ensign Peak while seeking divine guidance following the 1844 death of the Prophet Joseph Smith. "After the death of Joseph Smith, when it seemed as if every trouble and calamity had come upon the Saints, Brigham Young, who was President of the Twelve, then the presiding Quorum of the Church, sought the Lord to know what they should do, and where they should lead the people for safety, and while they were fasting and praying daily on this subject, President Young had a vision of Joseph Smith, who showed him the mountain that we now call Ensign Peak, immediately north of Salt Lake City, and there was an ensign fell upon that peak, and Joseph said, 'Build under the point where the colors fall and you will prosper and have peace.’” [2] Young understood that he was to lead the Church members west and that the peak he saw in vision would be a sign that they had reached their appointed destination.

On July 24, 1847, Brigham Young arrived at an overlook for his first view of the Salt Lake Valley. “While gazing upon the scene, . . . he was enwrapped in vision for several minutes. He had seen the valley before in vision and upon this occasion he saw the future glory of Zion and of Israel, as they would be, planted in the valleys of these mountains. When the vision had passed, he said: ‘It is enough. This is the right place. Drive on.’” [3]

Because the pioneers had no firsthand knowledge of the territory, they had relied on their prophet to determine the place of settlement in the West. [4] This happened when President Young viewed the valley for the first time and recognized Ensign Peak, which he had seen in the above-mentioned vision. In an 1866 interview with a visitor to Salt Lake City, Brigham reflected on this experience. The interviewer recorded the following: “When coming over the mountains, in search of a new home for his people, he [Brigham Young] saw in a vision of the night, an angel standing on a conical hill, pointing to a spot of ground on which the new temple must be built. Coming down into this basin of Salt Lake, he first sought for the cone which he had seen in his dream; and when he had found it, he noticed a stream of fresh hill-water flowing at its base, which he called City Creek.” [5] Because of his prior vision, Ensign Peak played an important role in helping the prophet recognize the place appointed as a home for the Saints.

Soon after entering the valley, President Young pointed at Ensign Peak and said, “I want to go there.” He suggested that the peak "was a proper place to raise an ensign to the nations," and so it was named Ensign Peak. [6] On July 26, 1847, a party consisting of Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, Willard Richards, Ezra T. Benson, George A. Smith, Wilford Woodruff, Albert Carrington, William Clayton, Lorenzo Dow Young, and perhaps Parley P. Pratt climbed to the top of the hill. Of the event, Wilford Woodruff recorded that the group “went North of the camp about five miles and we all went onto the top of a high peak in the edge of the mountain which we considered a good place to raise an ensign upon which we named Ensign Peak or Hill. I was the first person that ascended this hill. Brother Young was very weary in climbing the peak, he being feeble.” [7] While on the Peak, the group surveyed the valley below with Heber Kimball’s telescope to confirm their earlier judgment of the valley. “They appeared delighted with the view of the surrounding country,” said one of the settlers who heard the explorers’ report later in the day. [8] From this experience, the group gained the perspective necessary to begin planning the settlement. At this time, President Young apparently also determined the location of the temple, which he announced two days later, on July 28, by planting his walking stick at the site selected for the temple and saying, "Here we will build the temple of our God." [9]

A Flag on Ensign Peak

Did the Brigham Young party of pioneers raise a flag on Ensign Peak that July day in 1847? Throughout the years, many accepted that President Young had flown an American flag from the peak on July 26, while claiming the land as U.S. territory. Because that is highly unlikely, did the pioneers fly another type of flag that day on Ensign Peak?

As early as June 1844, the Prophet Joseph Smith had suggested the creation of an ensign on flag that could be flown by the Saints. [10] He proposed a sixteen-foot flag of a unique design and construction that was never completed. However, while at Winter Quarters, Brigham Young remembered that he had seen in vision a flag flying on Ensign Peak. [11] Therefore, he commissioned the purchase of material suitable for a flag. Young desired that the colors of red, white, and blue be used along with a purple and scarlet insignia. Because the exact design of the flag was unknown, Heber C. Kimball suggested the Church leaders dream about it. The resulting flag became known as one of a group of flags known by the title “ mammoth flag.” [12] While this flag may have been publicly displayed during pioneer times, there is no evidence that this flag or others constructed by the Saints were flown publicly from Ensign Peak on July 26.

Many Saints, including Wilford Woodruff, fully expected to see a literal “Standard of Liberty reared up as an ensign to the nations.” [13] In 1847, he spoke of “the standard and ensign that would be reared in Zion” and even made a sketch of a possible flag that he believed would serve as a standard to the nations. His version of the flag had distinctive Mormon symbols such as the sun, moon, and stars, as well as the symbolic use of the number twelve. It is clear that Woodruff believed that a flag such as this could be flown from the peak. [14] However, no evidence exists that this took place.

While it is possible that a group of pioneers did fly an American flag from Ensign Peak in 1847, there is also no evidence to support the community belief that President Young flew an American flag on Ensign Peak, July 26, while claiming the region for the United States. Regardless of the lack of historical details, Salt Lake City newspapers regularly referred to the raising of an American flag as a political act. For example, an 1884 news article referred to such an event in an article written to promote American patriotism. [15] Another news article in 1886 quoted a judge who described the Mormons as good citizens and cited as evidence their hoisting of an American flag on the peak upon their arrival in 1847. [16] Such reports persisted into the new century, as observed in an article written in 1901 that stated that Brigham Young had raised a flag on Ensign Peak and claimed the land in the name of the United States. [17] Stimulus for this belief continued into the twentieth century and was fueled by Susa Young Gates, a daughter of Brigham Young. Anxious to demonstrate the loyalty of the Mormons to the United States, she declared that her father and others had flown the American flag on Ensign Peak at the time they first climbed to its summit. Later, when writing her father’s biography, she softened her claim regarding the American flag. [18] The origins of these beliefs appear to be more politically motivated than historically accurate. In 1921, Elder B. H. Roberts, a Church historian, wrote the following to quell the myth of the American flag on Ensign Peak:

There has been one error promulgated in respect to the United States flag and Mormon history that I think, for the sake of accuracy in our history, ought to be corrected. This is the quite generally accepted idea or understanding that on the 26th day of July, when what is now called Ensign Peak was first visited by President Young and a group of pioneers, they there and then raised a United States flag and named the mount Ensign Peak. There is no evidence that they raised any flag on that mount at that time, or that they referred to the flag of the United States, when speaking of an “Ensign” in relation to that “hill” in the side of the mountain. They were merely out exploring the Salt Lake Valley northward, and extended their short journey as far as the Hot Springs, during which they climbed the hill we now call Ensign Peak. Had such an event as raising the United States flag taken place at that time, it certainly would have been recorded in the journal of some of the men present. Brigham Young gave the mountain its name, and makes an entry of that fact in his journal, but says nothing of any flag incident. Neither does Wilford Woodruff who related the events of the naming of Ensign Peak at length. [19]

Rather than any flag being flown on Ensign Peak upon the Saints’ arrival in the valley, it appears likely that the brethren waved a large yellow bandana at the peak’s summit. In support of this view, the Salt Lake Tribune quoted William A. C. Smoot, an early Church pioneer, as saying, “while they were up there looking around they went through some motions that we could not see from where we were, nor know what they meant. They formed a circle, seven or eight of them. But I could not tell what they were doing, . . . They hoisted a sort of flag on Ensign Peak. Not a flag, but a handkerchief belonging to Heber C. Kimball, one of those yellow bandanna kind.” [20] While this appears to be the truth of the matter, the controversy was not fully resolved. In the years that followed, many continued to believe that some type of flag unique to the Saints had flown or that Brigham Young had flown an American flag as part of an effort to claim Utah for the United States, an act which, in that time frame, would not have been legally feasible.

Pioneer Uses of Ensign Peak

During the latter part of the nineteenth century, the Church and community found a variety of uses for Ensign Peak. At that time, Addison Pratt received the temple endowment ordinance therein preparation for his mission to the South Seas. Of this event, Brigham Young recorded, “Addison Pratt received his endowments on Ensign Hill on the 21st, the place being consecrated for the purpose. [July 21, 1849] Myself and Elders Isaac Morley, P. P. Pratt, L. Snow, E. Snow, C. C. Rich and F. D. Richards, Levi W. Hancock, Henry Harriman and J. M. Grant being present. President H. C. Kimball, Bishop N. K. Whitney and Elder John Taylor came after the ordinances were attended to. Elders C. C. Rich and Addison Pratt were blessed by all, President Kimball being mouth.” [21] While there may have been other such events on Ensign Peak, direct evidence is lacking.

Another use of the Peak occurred during the Utah War (1857–58), when Church leaders stationed watchmen on the summit of Ensign Peak to watch for signals that indicated troop movements toward Salt Lake City. Smoke signals were used during the day, and fires provided the signals at night. When the watchmen saw these signals, they sent notices from Ensign Peak to the militia stationed in the city. [22]

Some years later, in 1899, the Army Signal Corps climbed the peak to demonstrate the effectiveness of their mirror signal techniques. In August of that year, they raised an American flag and then signaled the state governor, Herbert Manning Wells, that they had hoisted the flag in honor of the Utah volunteers in the Spanish-American War. Governor Wells then signaled back, “Hurrah for the signal corps! Let the flag float for the boys who have fought and bled and died for us.” [23]

In 1897, the Salt Lake Tribune, a local newspaper, erected a wooden flagpole on Ensign Peak to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the arrival of the pioneers in the Salt Lake Valley. [24] The wooden flagpole stood until 1947, when another one was erected as part of the pioneer centennial celebration. [25]

During the latter part of the nineteenth century, the peak served as a popular gathering place for public speeches and events hosted by Church and community groups. It was also common for individuals and groups to hike to the summit for a variety of purposes. Boy Scouts, Church groups, and other parties regularly climbed the peak to commemorate special dates or achievements. Many of these expeditions took place on July 24 as part of local Pioneer Day celebrations. So popular was the peak as a gathering place that many hoped that a formal park or memorial might be constructed at the summit.

Ensign Peak in the Twentieth Century

Early in the twentieth century, interest in a public park prompted Lon J. Haddock, a leader in the Salt Lake City Manufacturers and Merchants Association, to propose constructing a park on the peak that would attract tourists. The project was to be privately funded and managed for commercial purposes. [26] Utah’s senator Reed Smoot added his support to the effort, as did the local newspapers. However, the years passed with little progress being made in developing a park on Ensign Peak.

Nevertheless, efforts to use the peak for commercial purposes continued. One of the more interesting exploits of the peak came in 1910, when the first automobile was driven to its summit. [27] Not to be outdone, other automobile dealers and enthusiasts drove cars and motorcycles up the peak. The ventures proved to be excellent advertising for dealerships seeking increased sales. Given the local historical significance of the peak, such spectacles attracted considerable public interest.

In 1916, the public debated a plan to place a cross at the summit of Ensign Peak. Surprisingly enough, it was Charles W. Nibley, Presiding Bishop of the Church, who suggested placing a large concrete cross on the peak. [28] Bishop Nibley announced that the Church would provide leadership and funding for the project, which was designed to achieve two objectives. The first was to provide a visible reminder to the city below of the sacrifices made by the pioneers of 1847. Secondly, a visible cross would stand as a symbol to visitors who were not members of the Church that the Mormons were indeed a Christian people. [29] Many groups in the community objected to the plan, including members of the Church and various other religious organizations. This growing opposition within the community and Church prompted Bishop Nibley to abandon the plan. [30]

One year later, another proposal came to the attention of the city council. A monument to the Mormon Battalion was proposed for the summit of the peak. The plan called for a granite structure with four sides containing plaques listing the names of the members of the battalion and a brief account of their contribution to pioneer history. [31] Like previously proposed plans, this one never materialized.

Throughout the years, Ensign Peak remained a popular place to celebrate Pioneer Day; the Church’s Ensign Stake provided leadership for many of these events. Typical of these special affairs was a Boy Scout program conducted on the summit in July 1916. On that occasion, B. H. Roberts spoke to the gathering about pioneer history; his talk was followed by the raising of an American flag and the lighting of a huge bonfire. [32]

One of the most unique events held at Ensign Peak in the early twentieth century involved the Ku Klux Klan. During the 1920s this organization expanded into the western states. In the fall of 1924 they concentrated their efforts in Salt Lake County. By the end of the year, they had succeeded in establishing a statewide administrative structure that touched most of the communities within the state. In 1925, the rapid expansion of the Klan created a public backlash in Utah and throughout much of the nation. The Klan responded with a series of public demonstrations to regain their momentum. Marches were held in Washington, DC; Salt Lake City; and other major cities. In February 1925, the Klan launched their Utah offensive with a parade through the business district of Salt Lake City. They followed up with a second demonstration on April 6, during the Church’s semiannual general conference. Defying increasing community opposition, members of the Klan marched up Ensign Peak and burned several large crosses at the summit. To ensure the success of this effort, hooded Klansmen blocked access to the summit. This resulted in a public assembly at the foot of Ensign Peak that numbered in the thousands; some of those gathered were members of the Klan, and others were simply onlookers who were curious over the actions of this controversial group. While the Klan considered the event a success, it frightened the community, causing the Klan to continue to lose influence in Utah. [33]

Organized Efforts to Develop Ensign Peak

A few years later, community groups began another organized effort to develop the peak. Foremost among these groups was the newly organized Utah Pioneer Trails and Landmarks Association. Elder George Albert Smith initiated the organization of this group in September 1930 for the purpose of creating permanent markers to identify key pioneer historical sites. The members of the group desired to commemorate and preserve pioneer history for generations to come. [34] To achieve their objectives, they encouraged Church groups to host dinners and other fund-raising events to meet the costs of the markers. Others in the community also lent financial support, because the group planned to place markers at non-Mormon pioneer sites as well as at those associated with Church history. In the years that followed, the Association placed numbered markers at key pioneer historical sites, starting at Nauvoo and stretching across the west to the end of what they considered the Mormon Trail in San Diego. The group remained active for years to come, placing 125 markers throughout the West.

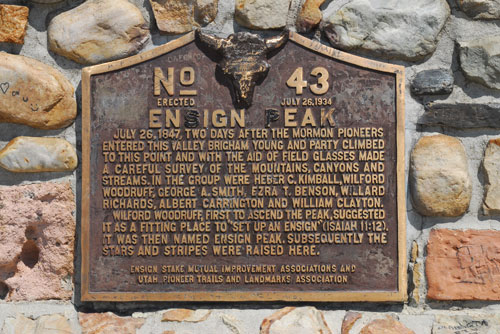

Significant to these endeavors, in 1934 the Utah Pioneer Trails and Landmarks Association became part of the effort of the Ensign Stake to construct a monument and marker on Ensign Peak. Arza Hinckley, president of the Ensign Stake, commissioned architect George Cannon Young to design a monument commemorating the arrival of the pioneers in the Salt Lake Valley. Church members and others contributed time and resources to construct the monument. The elaborate plans required that the monument be constructed of stones gathered from the Mormon Pioneer Trail and from different Church historical sites, including the Sacred Grove and the temple site in Independence, Missouri.

On July 26, 1934, a gathering of several hundred viewed the unveiling of the eighteen-foot monument as part of a ceremony that included addresses from community and Church leaders. President Heber J. Grant and other Church leaders climbed to the top of the peak to participate in the event. George Albert Smith, president of the Utah Pioneer Trails and Landmarks Association, served as the master of ceremonies. The keynote speaker was Reverend John Edward Carver of Ogden. Music for this occasion was provided by the 145th Field Artillery Band and the Orpheus Club Male Chorus. Young women who were direct descendants of the pioneers who first climbed the peak unveiled the monument. [35]

Historical plaque placed on Ensign Peak in 1934. (Courtesy of David M. Whitchurch.)

Historical plaque placed on Ensign Peak in 1934. (Courtesy of David M. Whitchurch.)

The Utah Pioneer Trails and Landmarks Association placed their forty-third marker on the monument, which provided an account of the naming of the mount on July 26, 1847. However, the information on the plaque concluded with this line, “It was then named Ensign Peak, subsequently the stars and stripes were raised here,” thus contributing to the myth that Brigham Young had raised an American flag there in 1847.

In the years that followed, the peak remained undeveloped, in spite of proposals to use it for advertising, real estate development, agriculture, or other commercial uses. Groups such as the Sons of Utah Pioneers staunchly defended the peak from such commercial ventures. During these years of discussion regarding the future of the peak, the City of Salt Lake continued to maintain the stance that their long-range goal envisioned the creation of a city park on Ensign Peak. Despite this claim, in 1952 the city renewed its efforts to commercially develop the land surrounding the peak when they proposed the sale of land at the base of the peak for a housing development. [36] This proposal met with stiff opposition. The Utah Pioneer Trails and Landmarks Association joined the Sons of Utah Pioneers, the Daughters of Utah Pioneers, and the Utah Historical Society to meet with the City Parks and Public Property Department to oppose the matter. Nevertheless, the project proceeded with a master plan that initially provided for eighty residential lots. [37] The housing development continued to expand around the base of the peak during the ensuing years.

Several years later, in 1961, the city responded to renewed attempts to develop a public park on Ensign Peak. [38] One proposal included the construction of a lookout on the summit and an outdoor amphitheater below the peak suitable for performances by groups such as the Tabernacle Choir and the Utah Symphony. Another proposal suggested a park similar to that at the “This Is the Place” monument east of the city. Unfortunately, such efforts as these met with little community support.

In the meantime, developers proposed the construction of a hundred-mile parkway from Fort Douglas in the west, across the north bench of Salt Lake City and around Ensign Peak, connecting Salt Lake and Davis counties. [39] The city determined that projected costs made this project unworkable. However, the idea of a parkway received renewed attention when others proposed the construction of a tunnel through Ensign Peak connecting Salt Lake City with Bountiful. Again the difficulty and cost of such a project led to its rejection. [40] Later, a road construction plan was revisited as part of a proposed scenic two-lane highway between Salt Lake City and Layton. The proposed drive would have a thirty-mile-an-hour speed limit as it wound around Ensign Peak and traveled north. Careful review of the plan, however, revealed that it would be inadequate for existing traffic demands between the cities. [41] In the following years, efforts to gain approval for a road around Ensign Peak that would connect Salt Lake City and Bountiful continued to prove unsuccessful.

Nevertheless, in spite of many unsuccessful proposals, interest in a public park on Ensign Peak did not diminish. In 1981, the city received a proposal for a smaller park than previously suggested. The proposal involved a land swap between the city and the Ensign Downs housing developer. Crowds gathered at the city council chambers to oppose this plan and support the development of a wilderness park on the peak. They feared that an expansion of the housing development that already surrounded much of the peak posed a further threat of encroachment on the peak itself. [42]

Recent Developments

By the end of the 1980s, time had taken a toll on Ensign Peak. Deep four-wheel-drive ruts ran across its face, the flagpole at the summit was rusted, and the monument had been defaced. Yet many groups remained interested in the potential of the site. Because the original historical marker placed on Ensign Peak in 1934 had been removed by vandals, the Sons of Utah Pioneers prepared a new one for placement adjacent to the peak in July 1989. [43] Gordon B. Hinckley, then counselor in the First Presidency of the Church, dedicated the marker. Later, the original marker was found in an old chicken coop by a scrap metal dealer, who gave it to the Daughters of Utah Pioneers organization. Although vandals had shot at the marker, leaving impressions in the metal face, it was otherwise in good condition. [44]

In 1990, the Salt Lake City Council approved ordinances that would enable the development of a 150-acre nature park around Ensign Peak. Included in the plans for the nature park was a proposal for a six-acre community park and a trail to the summit of the peak. [45] The development would also include an attractive entrance plaza with information markers, a viewpoint, and a trail leading to the summit. Throughout this process, a community organization known as Ensign Peak Foundation provided the leadership for the public-private venture. [46] President Hinckley also remained interested and involved in the development, even personally leading hikes to the summit, where he addressed participants. [47] On one such occasion, Elder Robert L. Backman observed, “We have not kept very good track of it [Ensign Peak].” He then quoted President Hinckley as saying, “We’ve neglected that peak too long.” [48] Interest in completing the development of Ensign Peak in time for the 1996 Utah State Centennial and the 1997 sesquicentennial of the arrival of the pioneers continued to gain momentum.

Following the groundbreaking ceremony on April 17, 1996, work began with the reseeding of the slopes and the construction of a permanent nature park and hiking trail. [49] On July 26, President Hinckley formally dedicated the Ensign Peak Historic Site and Nature Park. He reminded those gathered of the joy felt by the group that had first climbed Ensign Peak for a view of the valley below. “They had done a great thing. They had traveled all the way from a river to this valley. . . . They had reason to feel exultant and uplifted and positive and affirmative. . . . In Brigham Young’s mind, there was a fruition of the visions which he had had of this valley.” [50] As part of the service, Governor Michael O. Leavitt proffered a pioneer tribute, after which leaders of the Ensign Peak Foundation presented the completed park to the City of Salt Lake. In addition to their leadership and vision, this foundation had raised almost five hundred thousand dollars in support of the peak’s development. Without their dedicated efforts, the project would not have succeeded as it did. As a fitting conclusion to the dedication ceremony, the organizers released hundreds of helium balloons and waved large flags from the summit as a chorus sang the hymn “High on the Mountain Top.” [51]

The completed park features an entrance plaza with ten informational plaques and the refurbished 1934 marker. A trail beginning at the plaza leads to a viewpoint located halfway up the summit. The trail then continues to the summit, with stations along the way marked by benches and informational signs. From the summit, visitors can view the Salt Lake Valley, as did Brigham Young and his associates on July 26, 1847. [52]

During 1997, the Church constructed a memorial garden on land it owned near the base of the mount. [53] The garden features benches, trees, and a walkway with informational panels relating the history and significance of Ensign Peak. This final project completed, correlated, and reinforced the efforts of the Ensign Peak Foundation, the Church, and the City of Salt Lake in developing Ensign Peak as a historical site. It now stands as a witness of the inspiration that guided the Saints westward to their new home. From the visionary experience during which the Prophet Joseph Smith showed Brigham Young Ensign Peak to the experience of the first pioneer group who waved a yellow bandana on its summit to the thousands who have climbed to its summit in the years that followed, Ensign Peak remains a witness to the Lord’s hand in guiding his children and establishing the kingdom of God on the earth.

Afterword

Recently, Ensign Peak received renewed attention when the newly sustained Young Women general presidency climbed to its summit. Before her call as the Young Women general president, Elaine S. Dalton had climbed Ensign Peak with a group of youth. At that time she participated in a discussion related to the sacrifices required to establish the gospel and build the kingdom of God. At the conclusion of the meeting, each of the participants waved a symbolic banner on which they had written what they wanted to stand for in their lives. All those present then sang “High on the Mountain Top” and cheered in unison, “Hurrah for Israel.” [54]

When Sister Dalton became the general president of the Young Women in 2008, she led her counselors on a hike to the top of Ensign Peak. Upon reaching the summit, they gazed over the valley below and saw the statue of the angel Moroni atop the Salt Lake Temple. The impression was clear: their mission was to “help prepare each young woman to be worthy to make and keep sacred covenants and receive the ordinances of the temple.” [55] Like the first pioneers to climb the peak, they also waved a banner of their own. They considered their banner, made of a gold Peruvian shawl, to be an ensign to all nations, a symbolic call for a return to virtue. [56]

The experience of the Young Women general presidency and others has fulfilled in part the request made by President Hinckley in his dedicatory prayer: “We pray that through the years to come, many thousands of people of all faiths and all denominations, people of this nation and of other nations, may come here to reflect on the history and the efforts of those who pioneered this area. May this be a place of pondering, a place of remembrance, a place of thoughtful gratitude, a place of purposeful resolution.” [57]

Recent experiences such as these confirm the importance of the historic symbolism related to the peak. When Brigham Young and others stood on the summit, they envisioned the scope and direction of their call to build a grand city and temple to the Lord. Today, as Sister Dalton and others climb the peak, they view the great legacy left by the pioneers and the realization of their vision. Climbing the peak continues to provide the means of connecting the past with the present in order to better envision the future. And while some aspects of Ensign Peak have changed, it remains a place where Saints can gather to rejoice in the Restoration of the gospel, unfurling banners that “wave to all the world.”

Notes

In writing this article, the authors express appreciation for the definitive work of Ronald W. Walker. See Ronald W. Walker, “A Banner Is Unfurled,” Dialogue 26, no. 4 (1993): 71–91, and Ronald W. Walker, “A Gauge of the Times: Ensign Peak in the Twentieth Century,” Unit Historical Quarterly 62, no. 1 (1994): 4–25.

[1] Coordinates 40°47′40″N 111°53′27″W / 40.7944°N 111.8907°W .

[2] George A. Smith, in Journal of Discourses (London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1854–1886), 13:85.

[3] Wilford Woodruff, “The Pioneers,” Contributor, August 1880, 252–53.

[4] Erastus Snow, in Journal of Discourses, 16:207.

[5] British author and critic William Hepworth Dixon interviewed Brigham Young in 1866 and reported his statement concerning Ensign Peak. William Hepworth, Dixon New America (New York: AMS, 1972), 133–134.

[6] Smith, in Journal of Discourses, 16:207; Woodruff, “The Pioneers,” 253.

[7] Wilford Woodruff’s Journal (Salt Lake City: Kraut's Pioneer Press, 1982), 3:236.

[8] Howard Egan, Pioneering the West, 1846 to 1847, ed. William M. Egan (Richmond, UT: Howard R. Egan Estate, 1917), 108.

[9] Susa Young Gates and Leah D. Widstoe. The Life Story of Brigham Young (New York: Macmillan, 1931), 104.

[10] Council Meeting, February 26, 1847, Thomas Bullock minutes, in Walker, “Banner,” 75.

[11] Smith, in Journal of Discources, 13:86.

[12] In Walker, “Banner,” 75–76.

[13] In Walker, “Banner,” 77.

[14] D. Michael Quinn, “The Flag of the Kingdom of God,” BYU Studies 14, no. 1 (1973): 106–8.

[15] “The Mormons Defended,” Deseret News, June 25, 1884, 14.

[16] “Polygamy and the Common Law,” Deseret News, March 10, 1886, 6.

[17] “The ‘Mormon’ Creed and Its ‘Exponents,’” Deseret News, October 26, 1901, 23.

[18] Walker, “Gauge,” 9–10.

[19] B. H. Roberts, “The ‘Mormons’ and the United States Flag,” Improvement Era, January 1921, 3.

[20] William C. A. Smoot, “Remarks at the American Party Banquet–Ensign Peak Flag Incident,” Salt Lake Tribune, March 18, 1910, 2, in Walker, “Banner,” 82. President Hinckley, an avid student of Church history, accepts this account as evidenced by his reference to the bandana flown by Wilford Woodruff from Ensign Peak on July 26, 1847. Gordon B. Hinckley, “An Ensign to the Nations,” Ensign, November 1989, 51.

[21] Manuscript History of Brigham Young, ed. William S. Harwell (Salt Lake City: Collier's, 1997), 224–25.

[22] B. H. Roberts, A Comprehensive History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1912), 4:507.

[23] H. M. Wells, “Message from Ensign Peak,” Deseret Evening News, August 19, 1899, 2.

[24] Walker, “Gauge,” 5.

[25] “Utah Pioneers Will Receive Special Medals,” Deseret Evening News, March 14, 1947, 15. Eight years later, another flagpole was erected on Ensign Peak. The flagpole weighed over seven hundred pounds and was carried to the summit by hand. “New Flagpole Installed on Peak,” Deseret News, November 8, 1955, 2B.

[26] “Ensign Peak,” Deseret Evening News, August 8, 1908, 4.

[27] “Velie Automobile Climbs Ensign Peak,” Salt Lake Tribune, March 10, 1910, 4.

[28] “To Erect Cross on Ensign Peak,” Deseret Evening News, May 5, 1916, 2.

[29] “To Erect Cross on Ensign Peak,” 2.

[30] For a thorough treatment of the proposed cross, see Walker, “Gauge,” 13–16.

[31] A. Ad. Ramseyer, “Suggests Monument for Mormon Battalion,” Deseret News, February 5, 1917, 16.

[32] “Details Arranged for Boy Scout Program at Top of Ensign Peak,” Deseret News, July 26, 1916, 12.

[33] For a more complete treatment of the Klan in Utah, see Larry R. Gerlach, Blazing Crosses in Zion: The Ku Klux Klan in Utah (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1982),105–110.

[34] “President Smith Realizes Dream at Dedication,” Deseret News, July 24, 1947, 1, 8.

[35] “Ensign Peak Monument to Be Unveiled,” Deseret News, July 24, 1934, 9.

[36] “SUP Protests Sale of City-Owned Ensign Peak Region,” Deseret News, May 12, 1952, 6 “Pioneer Unit Sets Meet on Land Sale,” Deseret News, November 12, 1952, 18A.

[37] “Ensign Downs Firm Completes Master Building Plan for Area,” Deseret News, August 28, 1953, B1, B7.

[38] “Development Proposed for Ensign Peak Area,” Deseret News, December 28, 1961, 12A.

[39] Clarence Barker, “S.L. Roads Price Tag: $101.5 Million,” Deseret News, February 1, 1964, B1, B8.

[40] “Revises ‘Peak’ Tunnel Plan,” Deseret News, March 14, 1974, 2B.

[41] Wanda Lund, “Scenic Route Termed Impractical Now,” Deseret News, April 18, 1975, 4B.

[42] “Ensign Peak Plans Studied,” Deseret News, September 26, 1981, 2B.

[43] Scott Lloyd, “Sons of Utah Pioneers Unveil Maker to Honor the Naming of Ensign Peak,” Deseret News, July 22, 1989, B3.

[44] Jay Evensen, “Stolen Historic Marker Found in Old Chicken Coop,” Deseret News, September 27, 1992, B4. The original marker is now located in the plaza at the base of Ensign Peak.

[45] Joel Campbell, “Council OKs Plans Clearing Way for Zoning Change, Land Trade,” Deseret News, October 17, 1990, B3.

[46] After leading a successful effort to restore Ensign Peak, the Ensign Peak Foundation was reorganized in 1992 as the Mormon Historic Sites Foundation. Using the expertise they gained in the peak project, they expanded their work to include other historic sites. To date, they have proven to be one of the most successful groups in identifying and preserving Church historic sites.

[47] “Pres. Hinckley Will Keynote Hike to Ensign Peak,” Deseret News, July 15, 1993, B6; Jerry Spangler, “Ceremony on Ensign Peak Hails Vision and Courage of 8 Pioneers,” Deseret News, July 27, 1993, B3.

[48] R. Scott Lloyd, “Ensign Peak Hike Recalls Prophecy,” Deseret News, August 6, 1994, Z9.

[49] Douglas Palmer, “Work Begins to Turn Ensign Peak into a Park,” Deseret News, March 21, 1996, B11.

[50] Melissa Karren, “Modern-day Pioneers Blaze an Old Trail,” Deseret News, July 27, 1996, B3.

[51] R. Scott Lloyd, “Park at Ensign Peak Dedicated,” Deseret News, August 3, 1996, 3, 13.

[52] “Plazas, Information Plaques Entrance Hike to the Peak,” Church News, August 3, 1996, 3, 13. Currently the plaza has three flagpoles. These include one for the Utah state flag, one for the American flag, and the third for the blue and white pioneer flag first displayed during President Young’s administration.

[53] R. Scott Lloyd, “New Garden Graces Ensign Peak,” Deseret News, August 2, 1997, Z6.

[54] Elaine S. Dalton, “It Shows in Your Face,” Ensign, May 2006, 111.

[55] First Presidency letter, September 25, 1996, in Elaine S. Dalton, “A Return to Virtue,” Ensign, November 2009, 78.

[56] Sarah Jane Weaver, “New Value: Virtue,” Church News, December 16, 2009, 3.

[57] Lloyd, “Park at Ensign Peak Dedicated,” 3, 13.