Selections from the Autobiography of Mary Goble Pay

“Selections from the Autobiography of Mary Goble Pay,” in Rescued: The Courageous Journey of Mary Goble Pay, ed. Clark B. Hinckley (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 23‒62.

I, Mary Goble, was born in Brighton, Sussex, England, June 2, 1843. My father was William Goble, son of William and Harriet Johnson Goble. My mother was the daughter of John and Sarah Penfold. My childhood days were spent the same as most children[’s]. When I was in my twelfth year, my parents joined the Latter-Day Saints. On November the 5th I was baptized. The following May we started for Utah. We left our home[1] May 19, 1856.

We came to London the first day,[2] the next day came to Liverpool,[3] and [then we] went on board the ship Horizon that evening.[4] It was a sailing vessel.[5] There were nearly nine hundred souls on board.[6]

We sailed on the 25th. The pilot ship came and tugged us out into the open sea. I well remember how we watched old England fade from sight. We sang, “Farewell, Our Native Land, Farewell.”[7]

While we were in the river, the crew mutinied and they were put ashore, and another crew came on board.[8] They were a good set of men.[9] When we were a few days out, a large shark followed the vessel. There was one of the saints who died; he was buried in the sea.[10] We never saw the shark any more.

After we got over our seasickness, we had a nice time. We would play games and sing songs of Zion. We held meetings, and the time passed happily.[11] When we were sailing through the banks of Newfoundland, we were in a dense fog for several days. The sailors were kept night and day ringing bells and blowing foghorns. One day I was on deck with my father, when I saw a mountain of ice in the sea close to the ship. I said, “Look, father, look.” He went as white as a ghost and said, “Oh, my girl.” At that moment the fog parted. The sun shone bright till the ship was out of danger, [t]hen the fog closed on us again.

We were on the sea six weeks when we landed at Boston.[12] We took the train[13] for Iowa City, where we had to get our outfit for the plains. It was the end of July.[14]

On the first of August[15] we started to travel with our ox teams unbroke[n], and we did not know a thing about driving oxen.[16] My father had bought two yoke of oxen, one yoke of cows, a wagon, and [a] tent. He had a wife and six children. Their names were Mary, Edwin, Caroline, Harriet, James and Fanny.[17]

My sister Fanny broke out with the measles on the ship,[18] and when we were in Iowa Campground,[19] there came up a thunder storm. It blew down our shelter made with hand carts and some quilts. The storm came and we were there in the rain, thunder and lightning.[20] Fanny got wet and died the 19th of July 1856. She would have been two years old on the 23rd of July. The day before we started on our journey, we visited her grave.[21] We felt awful to leave our little sister there.

We traveled through the States until we got to Council Bluffs.[22] I think that was the name. It is in Wyoming.[23] Then we started on our journey of one thousand miles over the plains. It was about the first of September.[24] We traveled from 15 to 25 miles a day. We used to stop one day in the week to wash, and [we] rested on Sunday to hold our meetings. Every morning and night we were called to prayers by the bugle.[25]

The Indians were very hostile as they were on the warpath, so our Captain J[ohn] Hunt[26] had us make a dark camp. That was to stop and get our supper, then travel a few miles and not light any fires but camp and go to bed. The men had to travel all day and guard every other night.[27]

One night the cattle were in the corral made with the wagons, when one of the guards saw something crawling along the ground. All in a moment the cattle started. It was a noise like thunder. [The guard] shot off his gun when the animal jumped up and ran. It was an Indian with a buffalo robe; he dropped it. Mother and us children were sitting in the tent. Father was on guard. I tell you, we thought our time had come. But Father came running to tell us not to be scared for everything was all right.

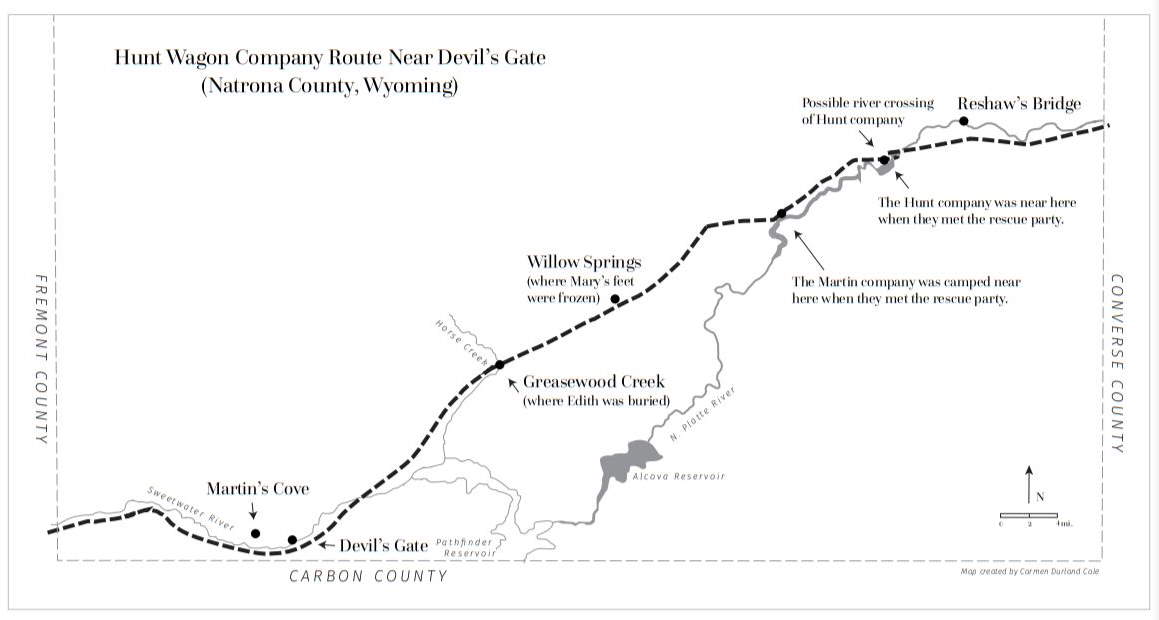

We traveled on till we got to the last crossing of the Platte River.[28] That was the last walk I ever walked with my mother. We caught up with the handcart companies that day. We watched them cross the river.[29] There were great lumps of ice floating down the river. It was bitter cold. The next morning there were fourteen dead in camp through the cold.[30] We went back to camp and went to prayers. They sang, “Come, Come, Ye Saints, No Toil Nor Labor Fear.” I wondered what made my mother cry. That night my mother took sick. The next morning my little sister was born. It was the 23rd of September. We named her Edith. She lived six weeks and died for want of nourishment and was buried at the last crossing of the Sweetwater.[31]

My mother never got well. She lingered till the 11th of December, the day we arrived in Salt Lake City, 1856. She died between the Little and Big Mountains. She was buried in Salt Lake City Cemetery. Her age was 43 years. She and her babe lost their [lives] gathering to Zion in such a late season of the year.[32]

We traveled in the snow from the last crossing of the Platte River. We had orders to not pass the handcart companies. We had to keep close to them so as to help them if we could. We began to get short of food. Our cattle gave out. We could only travel a few miles a day. When we started out of camp in the morning, the brethren would shovel the snow to make a track for our cattle. They were weak for the want of food as the buffaloes were in large herds by the road and ate all the grass.[33]

When we arrived at Devil’s Gate it was bitter cold.[34] We left lots of our things there. There were two or three log houses there, and we left our wagon there and joined teams with a man by the name of James Farmer. He had a sister Mary [who had] frozen to death.[35] We stayed there two or three days. While there an ox fell on the ice, and the brethren killed it, and the beef was given out to the camp. We made soup of it. My brother James ate a hearty supper and was as well as he ever was when he went to bed. In the morning he was dead.[36]

I got my feet frozen and lost all of my toes. My brother Edwin got his feet frozen bad. My sister Carrie’s feet [were] frozen.[37] It was nothing but snow. We could not drive the pegs in for our tents. Father would clean a place for our tents and put snow around to keep it down.[38] We were short of flour, but father was a good shot.[39] They called him the hunter of the camp, so that helped us out. We could not get enough flour for bread as we got only a quarter of a pound per head per day, so we would make it like thin gruel. We called it “skilly.”[40]

Well, there were four companies on the plains.[41] We did not know what would become of us, when one night a man came to our camp telling us there would be plenty of flour in the morning for Bro. Brigham had sent men and teams to help us. There was rejoicing that night. Some sang, some danced, some cried. Well, he was a living Santy Claus. I have forgotten his name, but never will I forget how he looked. He was covered with the frost, and his beard was long and all frost.[42]

We traveled faster now that we had horse teams,[43] and we arrived in Salt Lake City at 9 o’clock at night the 11th of December 1856.[44] Three out of four that were living were frozen. My mother was dead in the wagon.[45]

Bishop Hardy[46] had us taken to a house in his ward, and the brethren and the sisters fetched us plenty of food. We had to be careful and not eat too much as it might kill us as we were so hungry.

The next day the bishop came and brought a doctor. His name was Williams.[47] He amputated our feet. The sisters were dressing mother for her grave. My poor father walked in the room where mother was, then back to us. He could not shed a tear. When our feet were fine they packed us in to see our mother for the last time. Oh, how did we stand it? That afternoon she was buried.[48]

• • •

Caroline “Carrie” Goble Bowers and Mary Goble Pay.

Caroline “Carrie” Goble Bowers and Mary Goble Pay.

It is now October 1906.[49] Fifty years ago we left our homes over the sea for Utah. Quite a few of us that are left have been to Salt Lake City to celebrate our Jubilee.[50] We met in the 14th Ward assembly hall.[51] We held three meetings. President Joseph F. Smith and the Relief Society furnished us a banquet. We had a very good time. I stayed with Anna Pay Kimball.[52] We met the captain of our company, Brother John Hunt, [and] met some of the people that came in our company. We were happy to see one another and talk of the times that are gone.

My sister Carrie and her husband went up to the city with us. Her husband came in Captain Ellsworth’s handcart company.[53] We went to conference [for] two days and then went to the cemetery to find my mother’s grave. It was in Lot 2, plot C. It was the first time I had seen it, for when she was buried our feet were so bad [that] we could not go to the funeral, and [then] the move came, and we moved south to Nephi.

No one knows how I felt as we stood there by her grave. There were Alma, his wife, myself, and Ethel, one of George’s daughters. There were three generations.[54] Our mother was a martyr for the truth. I thought of her words, “Polly, I want to go to Zion while my children are small, so they can be raised in the Gospel of Christ, for I know this is the true Church.”

Mary Goble Pay with children and grandchildren.

Mary Goble Pay with children and grandchildren.

Now there are 31 grandchildren [and] 26 great-grandchildren living, and 15 are dead. There are three of us living—my brother, sister, and myself. . . . I think my mother has her wish. My brother and three of my sons have [ful]filled missions,[55] and some of her grandsons and [grand]daughters are workers in the Church. They are all members of the Church. I now have six sons and one daughter living, four sons are married, and I have eleven grandchildren. I am proud of them all. I am the mother of thirteen children, ten sons and three daughters. My brother Edwin is the father of fifteen sons and daughters. My sister Carrie is the mother of nine—five sons and four daughters. My sister Harriet is [also] the mother of nine—seven sons and two daughters. [56]

• • •

Nephi, Oct. 1908. Have been to our Handcart Reunion.[57] I met quite a few old friends. Went to conference. My brother and I went to see my mother’s grave. They had renumbered them. It is plot F, Lot 8 or 12.[58] We will have it fixed [and] leveled and [have] grass sown on it.

• • •

Oct. 21, 1909. Went to Sunday School and was asked to relate incidents of our journey across the plains. I told them we had the first snow storm the 22nd of September, 1856.[59] There were fifteen who died through crossing the River Platte.[60] Sister McPherson[61] sat by me. She said, “My mother was the fifteenth one that died.” They were laid side by side and a little dirt [was] thrown over them.[62]

• • •

November. I have been to our reunion. I met Bro. Langley Bailey.[63] Had a good time. Told of incidents of our trip over the plains. It made us feel bad—it brought it all up again. Is it wise for our children to see what their parents passed through for the Gospel? Yes.

Notes

[1] William Goble is listed in the 1851 Brighton post office directory as a “Fruiterer & Greengrocer” living at 53 Russell Square in Brighton, Sussex.

[2] The Brighton station of the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway was located less than a mile from the Gobles’ home. The fifty-five-mile trip to London ended at London Bridge station. The next day the Gobles left London from Euston Station, about three miles from London Bridge, on the West Coast Main Line for Lime Street Station in Liverpool.

[3] Liverpool was a principal Atlantic seaport of England. The Liverpool Mercury for 21 May 1856 includes notices of commercial ships sailing to Port Natal (South Africa), Australia, Trieste, Genoa, Naples, Le Havre, and Constantinople. The paper also notes preparations for a great public holiday on 29 May 1856 to celebrate the end of the Crimean War. The celebrations were to include “a public demonstration of the children educated in the town” and a regatta on the River Mersey. In the mid-nineteenth century, Liverpool rivaled London in wealth. Nathaniel Hawthorne, already a successful and well-known author, was the US consul in Liverpool in 1856.

[4] By Mary’s accounting, the family arrived in Liverpool on Tuesday, 20 May 1856, and boarded the Horizon that evening. The ship left the dock on Friday, 23 May, and anchored in the river. It was brought into open sea and officially began the voyage on Sunday, 25 May.

[5] By 1856 steamships were crossing the Atlantic regularly. The passage by steamship took about ten days, compared to thirty-seven days for the Horizon, but the price of passage on a steamship was far too expensive for most immigrants. It was not until 1863 that a majority of immigrants traveled to America by steam. See Edwin C. Guillet, The Great Migration: The Atlantic Crossing by Sailing-ship Since 1770, 2nd ed. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1963); and The Geography of Transport Systems, https://

[6] The Horizon was a US registered ship of 1,775 tons under the command of Captain W. Reed. It sailed from Liverpool on 25 May 1856 with 856 Saints and arrived in Boston on 30 June 1856 after thirty-seven days at sea. While nearly 75 percent of the passengers received financial assistance from the PEF, the Gobles paid their own way, sending nine pounds in advance to reserve their passage and paying the remaining 26.50 pounds upon boarding. They held ticket 144. The ship register lists William Goble as a “Greengrocer” and Mary Goble, age twelve, as “Spinster.” For rosters and information on each ship see Saints by Sea database at https://

[7] See Sidebar 1: “Farewell, My Native Land, Farewell.”

[8] The mutiny took place while the Horizon was still in the River Mersey and before the captain had boarded. Heber Robert McBride remembered, “When we got out on the river and cast anchor . . . the sailors and the ship officers got into a quarrel and began to fight. This almost frightened some of the emigrants to death, but the first mate ran into the cabin and came out facing the men that was after him with a pistol in each hand caused them to stop very quick. He told them the first man that moved he would shoot him down. He stood there and kept them back till a signal of distress was sent up and it was hardly any time before boats came alongside with policem[e]n and all the crew was put in irons and taken to shore.” Heber Robert McBride, Autobiography, 5–9, 15–16, CHL. John Jaques also recorded the incident. See Millennial Star 18, no. 26 (28 June 1856): 411–12.

[9] John Jaques was particularly complimentary of Captain Reed: “As regarding our Captain, I can speak nothing but good. . . . He acted like a man and a gentleman.” John Jaques to Orson Pratt, 22 July 1856, in Millennial Star 18, no. 35 (30 August 1856): 556.

[10] The death mentioned by Mary was probably that of George Baker, age twenty-seven, from Brighton, who died on Sunday, 1 June 1856. See Sidebar 2: Life aboard the Horizon.

[11] See Sidebar 2: Life aboard the Horizon.

[12] On Monday, 30 June 1856, the steam tug Huron towed the ship to Boston’s Constitution Wharf and the passengers disembarked, ward by ward. They had been at sea thirty-seven days. John Jaques recorded on Sunday, 29 June 1856, “While the doctor was passing the passengers, the captain and his family came on board. Meeting on the main deck at 3 p.m. Three cheers for the captain and three for the officers and crew. The captain responded and said that this company of emigrants was the best he had brought across the sea. He complimented them on their good behavior and said that we sang, ‘We’ll Marry None But Mormons,’ and he said he would say that he should ‘Carry None But Mormons.’” He added, “Seventeen years later [1873] Captain Reed crossed the continent, not by handcart, but by rail, and called on a few of the emigrants residing in Salt Lake, whom he carried across the Atlantic. Very much pleased was the old gentleman to see them.” Bell, 100, 106.

[13] Like ship travel, train travel was uncomfortable, with the emigrants traveling in boxcars while sitting on their luggage.

[14] Jesse Haven reported a temperature of 108 degrees in Iowa City on 22 July 1856. Haven, 22 July 1856. Traveling in such hot weather, it is not too surprising that the emigrants could not appreciate the risk of leaving so late in the season.

[15] The Hunt Journal records that the fifth wagon company left on 1 August 1856 with about three hundred emigrants and fifty-six wagons.

[16] Many of the Saints had little or no experience working with oxen, and the learning curve was necessarily steep. Ruth May Fox recalled, “Imagine if you can these would-be drivers, who had, perhaps, never seen a Texas steer before, go though the procedure for the first time of yoking their cattle. Truly no rodeo could match the scene. The men had to be instructed in this art and some did not learn very quickly.” Ruth May Fox, “From England to Salt Lake Valley in 1867,” Improvement Era, July 1935, 408–9, 450. Managing unruly oxen was both challenging and dangerous. The Hunt Journal notes that on 7 October some of the oxen began stampeding. “Sister Esther Walters . . . was knocked down and so badly injured that she expired in a few minutes . . . leaving a babe four weeks old.” The Gobles’ wagon was broken in the stampede and had to be repaired before they could continue.

[17] The Goble children (and their ages on the trek) were Mary, born 2 June 1843 (age thirteen), died 25 September 1913; Edwin, born 29 September 1845 (age eleven), died 27 October 1913; Caroline, born 21 January 1848 (age eight), died 14 February 1922; Harriet, born 31 May 1850 (age six), died 20 June 1890; James, born 23 May 1852 (age four), died 6 November 1856 (at Devils Gate, Wyoming); Fanny, born 23 July 1854 (age two), died 19 July 1856 (at Iowa City, Iowa). Edith was born 23 September 1856, died 3 November 1856 (near Greasewood Creek, present-day Horse Creek in Wyoming).

[18] In a letter addressed to Franklin D. Richards, written and mailed from Boston on 30 June, John Jaques reported, “The measles appeared on board on May 29 and many of the children and some adults have had the disease, but we have to record no deaths from it.” However, the next day, while still in Boston, Jaques recorded, “Bro. Palmer’s child died this evening of the measles.” Bell, 106.

[19] The campground was about three and a half miles northwest of Iowa City in an area now preserved as Mormon Handcart Park located in present-day Coralville, Iowa (just off Mormon Trek Boulevard). Several interpretive signs have been placed in the park. Saints from the Horizon arrived on 8 and 9 July; Saints from the Thornton, most of whom were organized into the Willie company, had arrived at the campground on 26 June and did not leave until 15 July, so for six or seven days, there were over sixteen hundred emigrants living in the campground.

[20] The storm occurred the day the emigrants from the Horizon arrived at Iowa City, and the Gobles apparently had not yet purchased a wagon, and so found shelter where they could.

Elizabeth White Stewart, a member of the Hunt company, recorded, “When we completed our journey to Iowa City we were informed that we would have to walk four miles to our camping ground. All felt delighted to have the privilege of a pleasant walk. We all started, about 500 of us, with our bedding. We had not gone far before it began to thunder and lightning and the rain poured. The roads became very muddy and slippery. The day was far advanced and it was late in the evening before we arrived at the camp. We all got very wet. The boys soon got our tent up so we were fixed for the night, although very wet.” Elizabeth White Stewart, “Autobiography,” in Ancestors of Isaac Mitton Stewart and Elizabeth White, comp. Mary Ellen B. Workman (n.p., 1978), excerpt at https://

[21] A plaque in the Mormon Handcart Park identifies a pioneer burial ground where some of those who died at the campground were buried.

[22] The company passed through Council Bluffs, Iowa, and ferried across the Missouri River on 27 August 1856, to Florence, Nebraska (now part of Omaha, Nebraska). It covered a distance of 277 miles in twenty-two days, an average daily distance (including rest days) of 12.6 miles.

[23] Council Bluffs, Iowa, is located on the east bank of the Missouri River, just across from present-day Omaha, Nebraska. Known as Kanesville from 1848 to 1852, Council Bluffs was considered the beginning of the pioneer trail for both Mormons and other immigrants heading west.

[24] The company “commenced to move out of Florence at 8 o’clock a.m.” on 31 August. Hunt Journal, 23.

[25] See Sidebar 4: Life on the Trail.

[26] The company was originally led by Dan Jones (returning from a mission to Wales and distinct from the Daniel W. Jones of the rescue party), but he was asked to travel west with Franklin D. Richards. On 10 August, John Alexander Hunt was appointed captain and on 14 August, Dan Jones left the company. Hunt was born 16 May 1830 in Gibson County, Tennessee. He was baptized in March 1843, and in 1850 he made the journey to Utah. In 1852 he was called on a mission to England and returned in 1856 with many of his converts. He was twenty-six years old, single, and a returning missionary when he was captain of the wagon train. He died in St. Charles, Idaho, in 1913, the same year that Mary Goble Pay died.

[27] There was good reason to be concerned about American Indians, because a band of Cheyennes had killed several travelers in retaliation for the killing of some Indians by US troops. The Hunt company first learned of the killings on 5 September when the company met “some Californians who reported that Almon W. Babbitt’s company had been attacked by Indians and that two men and a child had been killed.” Hunt Journal,

5 September 1856. See Sidebar 4: Life on the Trail.

[28] Though generally referred to as the last crossing of the Platte, this is actually a crossing of the North Platte River near present-day Casper, Wyoming, about 625 miles west of Florence, Nebraska. The company covered this distance in 48 days, averaging 13 miles per day. See Sidebar 6: Last Crossing of the Platte.

[29] The Hunt company reached the ford about two p.m. on 19 October. The Hodgetts wagon company “had just forded when we arrived and the handcart company crossed directly afterwards.” Hunt Journal, 19 October 1856. Years later, Elizabeth White Stewart of the Hunt company remembered: “We finally reached the last crossing of the Platte River. We were then about 500 miles from Salt Lake. Our company camped on the east side and the handcart company passed over that night. All our able-bodied men turned out to help them carry women and children over the river. . . .The snow fell six inches during that night; there were thirteen deaths during the night. . . . The snow continued falling for three days.” Stewart, excerpt at https://

[30] Accounts regarding the number of deaths vary, but Elizabeth Horrocks Jackson of the Martin company recalled, as Mary did, that fourteen died during the night of 19–20 October. Leaves from the Life of Elizabeth Horrocks Jackson Kingsford (Ogden, UT, n.p. 1908).

[31] Mary combines some events in this paragraph that were actually several weeks apart. Edith was born 24 September in Nebraska; the Hunt company reached the last crossing of the Platte twenty-five days later, on 19 October, having traveled approximately 350 miles since Edith’s birth. On that day they helped the Martin company cross the Platte among lumps of floating ice and slush. A storm began just as the Martin company completed the crossing, with a fierce wind, snow, sleet and hail. On 20 October the Hunt Journal records, “This morning the ground covered with snow which prevented the company from moving.” The Hunt company stayed at the crossing for three days, trapped by the storm. They began fording the Platte about 1:00 p.m. on 22 October and camped about a mile beyond the crossing. Edith died at Greasewood Creek on 3 November. See Sidebar 5: Edith Goble.

[32] The Larsen manuscript includes an additional paragraph at this point in the narrative: “We had been without water for several days, just drinking snow water. The captain said there was a spring of fresh water just a few miles away. It was snowing hard, but my mother begged me to go and get her a drink. Another lady went with me. We were about half way to the spring when we found an old man who had fallen in the snow. He was frozen so stiff, we could not lift him, so the lady told me where to go and she would go back to camp for help for we knew he would soon be frozen if we left him. When she had gone I began to think of the Indians and looking and looking in all directions. I became confused and forgot the way I should go. I waded around in the snow up to my knees and I became lost. Later when I did not return to camp the men started out after me. It was 11:00 p.m. o’clock before they found me. My feet and legs were frozen. They carried me to camp and rubbed me with snow. They put my feet in a bucket of water. The pain was terrible. The frost came out of my legs and feet but did not come out of my toes.” See Sidebar 6: Lost in Snow.

[33] The express riders from the rescue company made contact with the Hunt company on the night of 28 October just about a mile from the last crossing of the Platte, where they had been trapped by snow after crossing the river. Traveling with the assistance of a few members of the rescue party, it took the company eight days to reach Devil’s Gate. The Martin company traveled a few miles ahead of the Hunt company. The Hodgetts company was between the Martin company and the Hunt company (see Hunt Journal, 5 November 1856), although their location is sometimes difficult to ascertain since there is no separate camp journal for the Hodgetts company. In a report to Brigham Young dated 2 November 1869, George Grant states, “Met br. [Edward] Martin’s company at Greasewood creek, on the last day of October; br. [William B.] Hodgett’s company was a few miles behind.” George D. Grant, “The Companies Yet on the Plains,” Deseret News [Weekly], 19 November 1856, 293. Appendix 4 gives a comparative chronology of the Willie, Martin, and Hunt companies, as well as this initial rescue party. See also Sidebar 8: The Rescue.

During this difficult stretch of road, the Hunt company draft animals became so weak that it was difficult for the company to make much progress through the snow and cold. The Hunt Journal reports that on 3 November “fourteen or fifteen oxen were left on the road.”

[34] Robert T. Burton of the rescue company recorded the following on 6 November 1856 at Devil’s Gate: “Colder than ever. Thermometer 11 degrees below zero. . . . None of the companies moved, so cold the people could not travel.”

[35] In the Larsen manuscript this name is rendered as Barman, but on close examination of the holograph it appears to be Farmer. James Morris Farmer (age thirty-nine) and his wife, Mary Ann Biddie Farmer (age twenty-six), together with three daughters (ages twelve, ten, and seven) and James’ sister, Mary Ann (or Mary Jane) Farmer (age twenty-six), were members of the Hunt company. However, none of the Farmer family died on the trek. Some lists include James Barman and his sister May (or Mary) as members of the Hunt company, but the only source for this appears to be the transcripts of Mary’s autobiography. They do not appear in the Pioneer Travel database of company members. See Riverton Wyoming Stake, Remember: The Willie and Martin Handcart Companies and Their Rescuers—Past and Present (Salt Lake City: Publishers Press, 1997), E-24.

[36] According to Mary’s granddaughters, “Edwin, 11, slept with his four-year-old brother, Jimmy. Edwin tried to wake him in the morning, crying, ‘Jimmy, wake up! Jimmy you are so cold, please wake up. Oh Jimmy!’ but Jimmy had died in the night. . . . Edwin had horrible dreams of that terrible night his entire life. He would cry out in the night, ‘Jimmy! Jimmy!’ His wife would wake him and say, “It’s OK, we’re home, all is well.” Document in possession of author.

[37] Although Mary does not mention it here, Harriet may have also suffered frozen toes. One family record states that Mary, Caroline, and Harriet all lost toes to gangrene. Jerry Garret, “Penfold—Goble Family History” (typewritten manuscript dated 22 June 1992, in possession of the author), 5.

[38] This is corroborated by Elizabeth Stewart: “The ground was frozen so hard they could not drive the tent pins, so they had to raise the tent poles and stretch out the flaps and bank them down with snow.” Stewart, https://

[39] The company roster shows that William brought two shotguns and a rifle on the journey. See “John A. Hunt Company Report, 1856,” CHL, CR 1234 5, https://

[40] “Skilly” was a British term for a weak broth, typically made with a little oatmeal. It was often served on ships and was standard fare for prisoners on ships in the nineteenth century.

[41] The Willie company arrived in Salt Lake City on 9 November 1856, the same day the other companies began moving out from Devil’s Gate. After emptying the wagons at Fort Seminoe, most of the handcarts were left behind and the essential supplies were transferred to wagons. From Devil’s Gate to South Pass, over nine hundred pioneers were strung out in a line that was often several miles long.

[42] At this point, Mary’s holograph shows this addition in pencil: “His name was Eph Hanks.” Although the company had been with members of the rescue party since 28 October, food was scarce and no one knew when they would find additional relief wagons.

[43] The Larsen manuscript includes these sentences inserted at this point: “My mother had never got well; she lingered until 11 December, the day we arrived in Salt Lake City, 1856. She died between the Little and Big Mountain[s]. She was buried in the Salt Lake City Cemetery. She was 43 years old. She and her baby lost their lives gathering to Zion in such a late season of the year. My sister was buried at the last crossing of the Sweetwater.”

[44] The Hunt Journal notes on 11 December, “The snow was 6 to 10 inches deep in G. S. L. City. Some teams arrived from Ft. Bridger.” On 12 December it notes, “The snow was 10 to 12 inches deep in G. S. L. City and it was still snowing.” The last of the wagon companies arrived in Salt Lake on 15 December 1856.

[45] In a letter to Samuel S. Jones dated 18 October 1908, Mary wrote, “Our mother never got well. She lingered for 11 weeks and died the 11 December 1856, between the Big and Little Mountain[s] about 4 o’clock in the afternoon. She was buried in the City Cemetery. I rode in the same bed with my dead mother till 9 o’clock that night.” See appendix 2.

[46] Leonard Wilford Hardy, age fifty-five, was the police chief of Salt Lake City and bishop of the Twelfth Ward. A native of Massachusetts, he was baptized at age twenty-six by Orson Hyde on 2 December 1832 and accompanied Wilford Woodruff on a mission to Liverpool in 1845, laboring in Manchester and presiding over the Preston Conference. He arrived in Utah on 14 October 1850 in the Wilford Woodruff company. On 17 December 1856, the Deseret News published this report: “Bishop L. W. Hardy reports the new arrivals to be in fine spirits, notwithstanding their late hardships; and those who so liberally turned out to their relief report themselves ready to start out again, were it necessary. But few in the two rear companies were frosted, and of those only one or two severely. Bishop Hardy at once threw open his doors to the family in which were the ones most severely frosted, and under his judicious nursing, without amputation, they are rapidly recovering; though the one most frosted will, perhaps, be somewhat crippled in her feet.”

[47] This was likely Ezra Granger Williams, who was a physician and surgeon in Salt Lake City at the time. The son of Frederick G. Williams (who served as a counselor to Joseph Smith in the First Presidency), Ezra was born on 17 November 1823. He was baptized by Joseph Smith in the Chagrin River in Kirtland and confirmed by Hyrum Smith in Hyrum’s home on 14 April 1832. He arrived in 1849 in Salt Lake City, where he practiced medicine until 1860. He later moved to Ogden.

[48] The Larsen manuscript replaces this paragraph with the following: “Early next morning Bro. Brigham Young and a doctor came. The doctor’s name was Williams. When Bro. Young came in he shook hands with us all. When he saw our condition, our feet frozen and our mother dead, tears rolled down his cheeks.

“The doctor wanted to cut my feet off at the ankles. But Pres. Young said no just cut off the toes and I promise you, you will never have to take them off any farther. The pieces of bone that must come out will work out through the skin themselves.

“The doctor amputated my toes using a saw and a butcher knife. The sisters were dressing mother for her grave. My poor father walked in the room where mother was, then back to us. He could not shed a tear. When our feet were fixed they packed us in to see our mother for the last time. Oh, how did we stand it? That afternoon she was buried.”

[49] The holograph says “1896,” but this was crossed out, and “1906” had been written above it.

[50] The jubilee was organized by the Handcart Veterans Association and held 3–5 October. It received extensive newspaper coverage that included stories from many of the pioneers. It concluded with a Friday night meeting in the Assembly Hall on Temple Square, where Utah governor John Cutler addressed the participants. The Jubilee chairman was Samuel Stephen Jones, who was nineteen when he emigrated with the Martin company. Mary traveled from Nephi to attend the Jubilee. See Handcart Veterans Association scrapbook, 1906–1914, CHL MS 11378.

[51] The Fourteenth Ward building was located at 142 West 200 North in Salt Lake City.

[52] Anna Sinclair Pay Kimball was Mary’s daughter-in-law. Anna Sinclair was born in Moroni, Utah, on 14 October 1864 and married George Pay, Mary and Richard’s second child, in 1883. George died in 1894, one year after Richard’s death. Anna then married Charles Spaulding Kimball, a son of Heber C. Kimball, in 1900. Charles died in 1925, leaving Anna widowed again. Anna died at eighty-four as the result of an automobile accident in 1949. She was buried next to George Pay in the Vine Bluff Cemetery in Nephi.

[53] On 19 January 1867, Carrie married Jacob Bowers, who was ten when he walked across the plains as part of the Edmund Ellsworth handcart company. He arrived in Salt Lake on 26 September 1856, just two days after little Edith Goble was born on the trail in Nebraska.

[54] The three generations were Mary Goble Pay, her son David Alma Pay (born 25 May 1873), and granddaughter Ethel Pay (born 4 October 1862, daughter of George Edwin Pay).

[55] Mary’s brother, Edwin, served in Liverpool (1890–91). Her three missionary sons were Edward (England, 1898–?), Jesse (Central States, 1898–1900; and Southern States, 1925–26), and LeRoy (Southern States, 1906–8). While in England, Edward baptized Mary’s aunt, Emma Penfold Simmonds, and at least one of Mary’s cousins (Emma’s daughter), Ada. Ada immigrated to Utah in 1909, crossing the country by train in four days. She lived with Mary in Nephi until she married in 1912. See Jerry Garrett, “Penfold—Goble Family History” (typewritten manuscript dated 22 June 1992), 6, https://

[56] At the date of this entry, the four Goble children who survived the trek had forty-six children between them.

[57] After the success of the reunion in 1906, the Handcart Veterans Association voted to do annual reunions.

[58] Now Plot F, Section F, 11/

[59] The Hunt Journal notes that the weather on 23 September 1856 was “cold and frosty” but makes no mention of a storm on the 22nd; the first snowstorm was the night of 19 October.

[60] As noted previously, there are various accounts regarding the number of emigrants who died.

[61] Jane Ann Ollerton McPherson was sixteen when she emigrated with her family. They sailed on the Horizon and were part of the Martin company. Both of her parents died on the journey. She moved to Nephi, where she met and married James Ramsey McPhereson. She died in 1933 at the age of ninety-two and is buried in the same cemetery as Mary Goble and Richard Pay. Jane Ann’s sister, Alice Ollerton, died the day after the family reached the Salt Lake Valley; she is buried in the Salt Lake City Cemetery next to Mary Penfold Goble. Jane Ann’s daughter Bertha McPherson wrote a short biographical sketch of her mother in 1950 in which she says, “Several times I asked mother to give me some information so that I could write a sketch of her life, but she always answered by saying, ‘My life has been very uneventful.’” Bertha McPherson, “Jane Ann Ollerton McPherson” (unpublished manuscript), https://

[62] On 15 April 1933, Harry Mills, a rancher near Casper, Wyoming, chanced upon some human bones in a small gulch near the North Platte River. Excavations over the following days revealed nine skeletons: five men, three women, and an infant. One of the skeletons was in a sitting position, suggesting that he had frozen. These may have been members of the Martin company. The remains were reinterred in Potters Field in the Highland Cemetery in Casper. The find was reported in the Casper Tribune Herald on 16 April 1933 and 17 April 1933 and discussed in the Wyoming Trails Newsletter 17, no. 3 (March 2005). Information courtesy of R. Scott Lorimer.

[63] Langley Bailey was a member of the Martin company, one of the four sons of John and Jane Bailey. Langley was eighteen during the trek but weighed only sixty pounds upon arriving in the valley. The family settled in Nephi, where Langley became a patriarch years later. He spoke at the funeral of Mary Goble Pay in 1913. His great-granddaughter Margaret Dyreng Nadauld served as Young Women General President from 1997 to 2002 and spoke of her great-grandfather in the general Young Women meeting on 27 March 1999.

Present-day Wyoming wilderness. The wagon companies passed through treacherous terrain to reach the Salt Lake Valley. Courtesy of Jim Black/

Present-day Wyoming wilderness. The wagon companies passed through treacherous terrain to reach the Salt Lake Valley. Courtesy of Jim Black/