"We Have Not Been Allowed the Liberty... to Worship As We Please"

Nancy Naomi Tracy and the Denial of Latter-day Saint Religious Liberty

Derek R. Sainsbury

Derek R. Sainsbury, "'We Have Not Been Allowed the Liberty... to Worship As We Please': Nancy Naomi Tracy and the Denial of Latter-day Saint Religious Liberty," in Religious Liberty and Latter-day Saints: Historical and Global Perspectives, ed. John C. Thomas and Robert T. Smith (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 129–64.

Derek R. Sainsbury is a religious educator who teaches for the Church History and Doctrine Department at Brigham Young University, a scholar of Latter-day Saint history, and author of Storming the Nation: The Political Missionaries of Joseph Smith’s Presidential Campaign.

THIS ARTICLE IS TEMPORARILY AVAILABLE (through Oct. 31, 2025) FOR ONLINE READING. LEARN MORE BY LISTENING TO YRELIGION PODCAST, EPISODE 131.

In 1896 eighty-year-old Nancy Naomi Tracy summarized in one sentence her experience since joining The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints with her husband sixty-two years earlier: “We have not been allowed the liberty . . . to worship as we please.”[1] She had not been, however, a passive victim. Rather, Nancy had fought for religious freedom throughout her life, most notably as the only female electioneer missionary of Joseph Smith’s 1844 presidential campaign. Her experiences and beliefs offer a unique window into the limits of religious freedom in the United States in the nineteenth century and the Latter-day Saint ordeal to obtain it. The arc of that struggle is well documented. Joseph Smith’s Zion quest created friction and confrontation with fellow Americans, which in turn led to new political realities and political philosophies for the Church. Smith’s subsequent assassination transferred those realities and philosophies to the Zion settlements created in Utah, only to be crushed by the federal government a half century later. Nancy’s roles as a woman, a wife, a mother, a widow twice over, a plural wife, a minor Church leader, and an electioneer give us an intimate, female, and on-the-ground view of the Latter-day Saint fight for religious liberty.

The major sources for accounts of Nancy’s life are three reminiscences she wrote in 1880, 1885, and 1896–99, respectively.[2] Her 1880 account is a straightforward narrative written for noted historian Hubert Howe Bancroft, who was gathering material for his future book History of Utah. Nancy wrote this account at the beginning of the intense federal government antipolygamy effort of the 1880s. A plural wife herself, that context contoured her memories through a lens of persecution, framing her life as a half-century of ongoing oppression because of her beliefs. Like several other contemporary Latter-day Saint women who wrote similarly persecution-tinged reminiscences, she staunchly defended plural marriage.[3] She countered national portrayals of Latter-day Saint women as repressed and their polygamous children as lesser and unhealthy, stating that plural marriage was “a pure and holy principle” and that she had raised her daughter born in plural marriage into an “honorable wife and mother.” Defending plural marriage as divinely mandated, she asked, “But when God speaks and commands, who shall we obey, him or man?” She answered her own question, “We’ll let God rule and command and all say amen and [we] will eventually triumph.”[4]

Nancy wrote her 1885 autobiography at the request of her adult children. This narrative is more personal and has significantly more details, including the deaths of her children during the years of persecution. She wrote it after being widowed for a second time and with the antipolygamy raid in full swing. At poignant moments of persecution in her narrative, she lashed out at her fellow Americans for not protecting the Saints’ religious and political rights. Her commentary even drifted into contemporary condemnation. For example, she needled “notorious” congressman Shelby M. Cullom for spreading “abominable falsehoods” about the Saints.[5] Additionally, since many understood a prophecy of Joseph Smith as predicting 1891 as the time of the Second Coming, Nancy concluded her reminiscence (like other women’s life writings) with an apocalyptic tone predicting “the end is near.” The kingdom of God would triumph by honoring the Constitution while their oppressors, “full of animosity and hatred,” were “tearing it to shreds.”[6] I will address Nancy’s final reminiscence, written from 1896–99, in more detail later in this paper. Suffice it to say, all three records showed in increasing detail a woman who framed her life as “one continual scene of persecution.”[7]

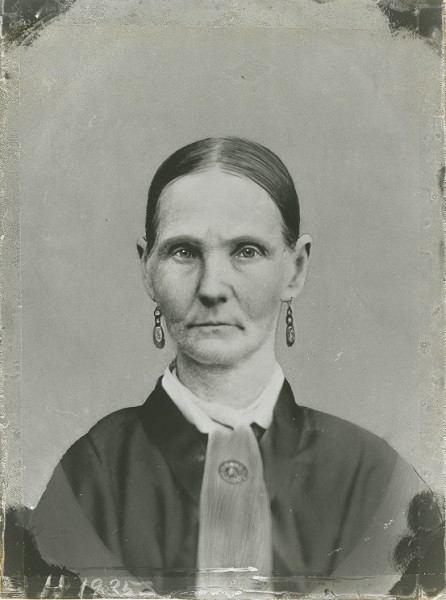

Young Nancy Naomi Alexander.

Young Nancy Naomi Alexander.

Nancy Naomi Alexander was born in upstate New York in 1816. Her father, Aaron Alexander, a veteran of the War of 1812, died just four years later. For the next eleven years her maternal grandmother, Mary Jones, a strict Methodist, and grandfather, Francis Jones, son of the Massachusetts Revolutionary War hero Francis Jones Sr., raised her. They instilled in Nancy a love of God and for the young republic. Her strong will, intelligence, work ethic, and kindness made her a “family favorite” of the Francis clan.[8] She excelled in school and was offered a contract to teach at just sixteen years old. Rather than take the position, she met and married twenty-two-year-old Moses Tracy that same year. Moses’s grandfathers, Titus Colvin and Solomon Tracy, had also fought in the Revolutionary War—Colvin as one of the original Green Mountain Boys and Solomon as a member of both the Continental army and navy. Thus, the young couple inherited a legacy of fathers and grandfathers who fought to secure the country’s rights of life, liberty, property, and religious freedom. However, those rights began to fade for Nancy and Moses when, in 1834, they joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.[9]

Nancy first heard a Latter-day Saint preacher in 1833 at Ellisburg, New York, where she and Moses lived on the farm of Moses’s father. The missionary was David Patten, and her experience was so powerful that she believed despite the intense reservations of her husband and his family. Soon thereafter, Nancy gave birth to their first child, Eli, and “hovered between life and death” for six weeks. She “determined that if the Lord should spare [her] life . . . [she] would be baptized.”[10] She recovered, and in the spring of 1834, she and Moses chose baptism and took an active role in the local branch of the Church. They determined to gather with the Saints in Kirtland in early 1835. Before leaving, Nancy first visited her family to share her new faith but was rejected as “deluded.” It was difficult to part with her grandparents, especially her grandmother, who “had been everything to [her].” They made the four-hundred-mile trip to Kirtland to dedicate all they had to their new faith and reveled in the spiritual “heaven on earth” experiences they had at the Kirtland Temple’s dedication in early 1836.[11]

The central cause of the Church of Jesus Christ in the nineteenth century was establishing Zion, defined as a society whose inhabitants are one in mind, conceived by the Saints as a political or governing component; one in heart, a social component; dwell in righteousness, a spiritual component; and have no poor among them, an economic component (see Moses 7:18). The revelations given through Joseph Smith encouraged converts to gather, construct a temple city, and build a holy society prepared for Christ’s millennial return and reign. However, the quest for Zion in Missouri had already created religious, political, social, and economic conflicts with their fellow Americans. Even before the Tracys were baptized, vigilante mobs had driven Latter-day Saints from Jackson County, depriving them of their lands and possessions and denying them their rights of life, liberty, and freedom of worship under the Missouri Constitution. Lawsuits, political diplomacy, efforts at redress to every state and federal branch of government, and even the arrival of a Latter-day Saint militia (Zion’s Camp) failed to reinstate the Saints to Jackson County. The situation was temporarily resolved when the Missouri legislature created Caldwell County as a type of “Mormon” reservation for Latter-day Saints to settle.[12]

In the summer of 1836, Moses and Nancy received permission from Joseph Smith to join a small group headed to Missouri. Thus far, the young couple had experienced mostly peace and happiness and “received many rich blessings in connection with the Saints.”[13] Missouri would change that. The young family barely survived the accident-prone trip to Missouri and the bitter cold and hunger of the first winter there. In the spring, they purchased forty acres just outside of Far West, the new gathering place in Missouri, and commenced farming.

Nancy gave birth to their third child in September 1838, just a month after Missourians violently prevented Latter-day Saint men from voting in nearby Daviess County—a confrontation that soon exploded into the Mormon War. The hostilities forced the Tracys to move back into Far West. Moses fought at the Battle of Crooked River and witnessed David Patten, whose preaching had converted Nancy, slowly die from a mortal wound. Receiving exaggerated reports of the skirmish, Governor Lilburn Boggs issued an extermination order leading to the imprisonment of Joseph Smith and other Church leaders and the sacking of Far West. Nancy remembered Smith telling a crowd of Saints just before he was betrayed that “we have sought to worship God according to the dictates of our conscience, and for this we suffer.” A fugitive for his role at Crooked River, Moses went into hiding as Nancy lay critically ill with malaria, five-year-old Eli her only help. While under double guard for several days, she saw and heard fellow Saints endure destruction and confiscation of their property, physical beatings, and even rape. She helplessly witnessed this unspeakable suffering at the hands of their fellow citizens, and to her, “it seemed as though all the infuriated demons of the lower regions were reveling in their atrocities.”[14]

In this hopeless condition, she remembered hearing the commanding general of the Missouri militia boast of his mercy in allowing the Saints, abused and beleaguered by his men, to leave the state in the spring instead of immediately. “Was this not wonderful?” Nancy sarcastically remembered in 1885. “It was a great boon for free-born American citizens that have been true and law abiding in every way.”[15] These events shattered her image of democratic government and the rights bequeathed to her and the other Saints, if not by God, then certainly by their citizenship. Mercifully, a neighbor evacuated the young family, who rendezvoused with Moses and the thousands of refugees headed to Illinois. Later, she and Moses joined their fellow Saints in formally petitioning the federal government for redress. Their affidavit requested five hundred dollars in lost property and another five hundred dollars for “being deprived of citizenship.”[16]

However, when Joseph Smith took these petitions to Washington, DC, President Martin Van Buren and the Congress refused to intervene on the grounds of states’ rights and expedient, electoral politics. As one historian has argued, “The states’ rights strategy was as effective at [denying the] full citizenship rights of religious minorities,” as it was at protecting slavery.[17] In the 1800s, full religious liberty was limited to traditional Protestants. Catholics, Latter-day Saints, and other religious minorities were seen as undemocratic for several reasons but most immediately for adherence to the authority of the Pope or a prophet. Such power seemed dangerous for the young and still fragile American experiment. Understandably, Smith and his followers lost confidence in the willingness of the American political system to protect their rights and freedom. Smith reportedly lamented, “Is liberty only a name? Is protection of person and property fled from free America?”[18] Writing for her grandchildren, Nancy was adamant that fellow Americans and the government had deprived the Latter-day Saints of religious liberty even though the Saints “honored and revered the laws of the land.”[19]

The Tracys began their third attempt at building Zion in a log hut in Nauvoo, Illinois, where malaria took their youngest son. They sold their lot to new friends Wilford and Phoebe Woodruff and built a frame house across the street. By 1844, they lived just east of the Nauvoo Temple in a nice frame home provided by Moses’s labor in Amos Davis’s general store and Nancy’s income from teaching school. The house was a comfort they would never know again.

During that time, Church leaders secured the Nauvoo Charter and the Nauvoo Legion, which allowed the Saints legal self-rule and protection. The first ordinance passed by the city council protected the religious freedom they had been repeatedly denied. Additionally, Joseph Smith formulated a political philosophy constructed from the excruciating experiences of Missouri, former revelations, and new inspiration. It was a worldview of divine governance as the eventual inheritance of the Saints and the United States, centering on two ideas—aristarchy and theodemocracy. Aristarchy, or “government by good or excellent men,”[20] aligned with Smith’s revelation to promote and vote for “good men and wise men” (Doctrine and Covenants 98:10). Theodemocracy, defined as when “God and the people hold the power to conduct the affairs of men in righteousness for the benefit of ALL,” expressed God’s sovereignty through his chosen aristarchic leaders, whom the people willingly supported.[21]

Middle-aged Nancy Naomi Alexander.

Middle-aged Nancy Naomi Alexander.

Joseph Smith introduced these themes in the Nauvoo Relief Society, local government elections, his presidential campaign, and the Council of Fifty. Nancy experienced each of these firsthand except the discussions in the Council of Fifty. Indeed, scholars trace the political awakening of Latter-day Saint women to the Nauvoo Relief Society, as did one of its founders, Sarah Granger Kimball, who wrote in 1891, “The sure foundations of the suffrage cause were deeply and permanently laid on the 17th of March 1842,” the date of the founding of the Nauvoo Relief Society.[22] When Smith established the Relief Society, he declared by previous revelation (Doctrine and Covenants 25) that his wife Emma was president. She nominated other officers and the members voted affirmatively to follow these leaders as an aristarchic, living constitution.[23] Using the pattern of male priesthood quorums, Smith introduced the gathered women to a mission wider than those of other contemporary female benevolent societies. He gave them roles to teach doctrine and to learn and receive religious authority; in Zion, by default, religion also contained social, economic, and political elements. Early on, the society’s leaders invited Nancy to join, and she reveled in the political and social space it afforded her to participate more directly in Zion.[24] She could express her views, receive instructions, organize collective work and relief, learn parliamentary procedures, and vote. As one historian noted, “[The] women in Nauvoo were able to exert power and influence, rarely seen anywhere in America at the time and . . . shape Mormonism.”[25] One example of this influence is when Nancy and fellow Relief Society members signed a collective letter to the governor of Illinois that Joseph Smith believed help save his life.[26] Later, Nancy signed another petition to the federal government for redress.[27] Her participation in the activities of the society so influenced Nancy that her eldest son Eli, though just ten years old at the time, still remembered her excitement fifty years later.[28]

At the temple site across from her home, Nancy also witnessed Joseph Smith nominate Church leaders for city offices and friendly non Latter-day Saints for county political offices. Subsequently, the male Saints, a majority in the county and a supermajority in Nauvoo, voted them into office. What Smith and his followers saw as a theodemocracy protecting God’s much-maligned Zion, outsiders viewed as a threatening theocracy, with a prophet who they believed placed himself above the law.[29] As conflict emerged again, Smith wrote to the likely candidates in the upcoming 1844 presidential election seeking assistance. When none offered help, Church leaders nominated Smith for president and began building a serious campaign.[30] Smith wrote a political pamphlet titled General Joseph Smith’s Views on the Powers and Policy of the Government of the United States and had it distributed throughout the nation.[31] Among other proposals, the broadside called for the president to have power to intervene within the states to ensure the constitutional rights of life, liberty, property, and religious expression. Smith called for a national political reformation, declaring the current system insufficient and its leaders corrupt. If elected, he would “restore the government to its pristine health and vigor.”[32] The ideas, philosophies, and wording of this document would strongly influence Nancy and her fellow Saints’ political beliefs for the next half century.

On March 11, 1844, Joseph Smith created another aristarchic, theodemocratic living constitution—the confidential Council of Fifty. Smith and his peers had given up on the American government, which from their experience allowed the majority to legally and extralegally deny a minority group their rights. A new system was needed, a theodemocratic one.[33] Believing they were the literal kingdom of God on earth that would endure into Christ’s millennial reign, the council orchestrated Smith’s presidential campaign while making plans to move Zion outside the nation’s borders if he lost the election. In April, Church leaders called for electioneer missionaries to canvass the nation, preaching and politicking for Smith by using and distributing the Views pamphlet. The apostles would direct the work in the field by holding conferences in the various states to rally supporters and organize the needed campaign infrastructure. Two hundred seventy-seven men initially enlisted. However, at the height of the campaign, over six hundred and thirty men (and Nancy Tracy) served—the largest missionary force Smith ever assembled and the largest the Church would field for the next sixty years.[34]

Moses Tracy volunteered, and Church leaders assigned him to his native state of New York. Twenty-eight-year-old Nancy wanted to go along, in part so that the children could meet their grandparents. “It seemed quite an undertaking,” she remembered, “but I felt equal to the task.”[35] She was. Nancy convinced Moses to ask Joseph and Hyrum Smith for permission. They concurred, saying she would assist him on his mission.[36] Moses and other missionaries received instructions from Church leaders on theodemocratic principles and electioneering, including taking Joseph Smith’s Views to reproduce and distribute in large numbers. With each new reminiscence Nancy wrote, the volume of details about their electioneering grew, perhaps because it became more important to her in the changing political context of the 1880s and 1890s. As theodemocracy waned in Utah, she wrote more and more about her electioneering mission. This was a unique feature of her narratives, as she was the only Latter-day Saint woman to serve in the campaign.[37]

The Tracys departed in early June of 1844 armed with copies of Views and their four sons, all under age eleven.[38] They traveled on various riverboats, canalboats, and railroads, arriving in Sacketts Harbor, New York, on June 20. As other electioneers were doing, there is evidence they preached and politicked along the way and certainly did so once in New York, including to their families.[39] Their relatives were overjoyed to see the children, but were cold to the message of Zion, except perhaps for Moses’s fourteen-year-old brother Silas, who was baptized around this time.[40]

Moses and Nancy also advocated Joseph Smith’s candidacy, sharing Smith’s Views with them. According to her account, Nancy also spent time with the grandparents who raised her to be godly and patriotic. It was obvious that they rejected Nancy’s faith, but unfortunately her accounts do not give a clear indication of how Francis Jones or even Moses’s grandfather Solomon Tracy reacted to Joseph Smith’s Views or candidacy. Had they been supportive, it is likely Nancy would have recorded it. So did they not lament the treatment of their precious Nancy and their grandchildren at the hands of mobs in Missouri? What of the gathering storm in Illinois? Or did they agree that Nancy and Moses’s faith was so radical that religious freedom did not extend to them? Nancy’s pen was silent.

Just days after the Tracys left Nauvoo, excommunicated dissenters printed the first and only copy of their newspaper, the Nauvoo Expositor, using a press they obtained from Joseph Smith’s political enemies. Utilizing a mixture of partial, uncontextualized truths and outright falsehoods, the paper “exposed” Smith as “a specimen . . . of the most pernicious and diabolical character that ever stained the pages of the historian, . . . a Hellish Fiend.” They accused Joseph of teaching “false and damnable doctrines” such as the “plurality of Gods . . . [and] wives,” of practicing “whoredoms,” of being a dictator in Nauvoo, and of attempting to overthrow the United States government to rule as king with his apostles as the states’ governors.[41] In response to the Expositor and remembering the still fresh horrors of Missouri, Smith concluded, “It is not safe that such things should exist on account of the mob spirit which they tend to produce.”[42] The Nauvoo City Council, including Smith as mayor, believed they had legal precedent to declare the press a nuisance and ordered its destruction. This set in motion a series of events that led to the incarceration of Smith, his brother Hyrum, and others in Carthage Jail just four days after the Tracys arrived in New York. There, on June 27, 1844, a conspiratorial mob assassinated the brothers.

Due to the era’s slow travel of news, word of the murders reached the Tracys in Ellisburg, New York, two weeks later.[43] Nancy remembered that they were “horror stricken.” Moses sat inconsolable, sobbing aloud, “Is it true? Can it be true, when so short a time ago he set us apart to fill this mission and was all right?”[44] Like all the other electioneer missionaries, Moses and Nancy had to process what the sudden death of their prophet and candidate meant. Despite taunts from others and perhaps from even their families that “your church will go to pieces now that your leaders have been killed,”[45] the Tracys recovered enough emotionally to carry on. On August 7, Moses and at least two other electioneers read a letter that had arrived in Ellisburg from the Quorum of the Twelve. It called for all missionaries who were high priests or that had families in Illinois to return immediately.[46] Moses was an elder and his family was with him, so he continued his mission preaching, but no longer politicking, through the summer and fall, converting two individuals. He and Nancy spent the winter stabilizing the Ellisburg branch, making “some things right that were not altogether in order.”[47] In the spring they returned to Nauvoo, but not before her beloved grandfather Francis Jones died. Tragically, on the return journey, their two-year-old fell ill and died soon after they arrived in Nauvoo. Nancy now had “two little boys laid side by side in the [Nauvoo] burying ground,” who had died in the wake of rejection from their fellow Americans. “O liberty! thou precious boon that our Fathers shed their blood to gain,” Nancy wrote, echoing Smith’s words four years previous, “whither hast thou fled?”[48]

Many Latter-day Saints saw Joseph Smith’s murder as a rejection by their fellow Americans of both religious and political salvation. Electioneer Amasa Lyman, observing a Fourth of July parade in Cincinnati, Ohio, wrote that the people made a “great preparation . . . to celebrate [the] birth of American liberty, which might better have been turned into a funeral.”[49] Nancy voiced what many Saints believed about the murders. “The plan [to kill Joseph Smith] was concocted from the official head down to the lowest demons that committed the dark deed,” she penned, “and this in our boasted land of Liberty that our fathers fought and bled to redeem from under the iron yoke, that we might be permitted to worship God as we chose and as our conscience dictated.”[50] In fact, in the wake of Smith’s assassination, Latter-day Saints would struggle for decades to celebrate Independence Day. Smith had been killed in state custody by the very extralegal mob violence he was running for president to expose and prevent. When the state of Illinois failed to deliver justice against the assassins, vigilantes understood that it was open season on the Mormons. “How often have the Saints asked for redress from mob violence and persecution from the leaders of this nation and they have turned a deaf ear to our entreaties,” Nancy questioned. “Where now is protection from the mob violence and persecution?”[51] The answer was, nowhere within the United States. In 1846, when the threat of further mob violence drove them from the nation, Latter-day Saints felt that the United States government, unwilling or unable to protect them, was irredeemably corrupt.

Unable to sell their home, the Tracys fled Nauvoo with their fellow Saints and struggled across Iowa Territory toward an uncertain future. The forced exodus would be a disaster for these refugees of religious bigotry. Within two years, across Iowa and along the banks of the Missouri River, approximately two thousand men, women, and children died from exposure, malnutrition, and disease. The Tracys did not escape unscathed. Near what would later become Winter Quarters, their eleven-year-old suddenly took ill with scarlet fever and died twelve days later. Nancy had now lost three of her six children, each in the wake of persecution and expulsion. Even writing half a century later, her anger towards the nation was palpable. The Saints had “sacrifice[d] their homes and their all to satisfy the blood-thirsty appetites of our enemies.” “May the Lord have mercy on our enemies’ souls,” she wrote, “for their cruelty and wickedness to an innocent and law-abiding people.”[52] Fourteen years old at the time, Eli, Nancy’s oldest son, would remember this season as the worst in his life. He used words like his mother’s. His family had “been driven, mobbed and robbed, plundered and butchered, and for what? Only because they worship Almighty God according to the dictates of their own conscience, guaranteed to every American citizen by the Constitution of the United States.”[53]

Nancy, her son, and many other scattered Saints were furious that their fellow citizens and their government had once again so brutally violated their rights. The answer to hers and Joseph Smith’s question, “Is liberty fled,” was yes, it fled the United States with the Saints. In their writings and speech, Nancy and other Saints framed themselves as the true Americans who would rescue the founding ideals of the nation, including religious liberty, by establishing them anew in the West. Their language mirrored Joseph Smith’s own statements in Views that the government was corrupt and needed rescuing by a moral people. Smith and his electioneers had tried to preserve the Constitution, but the nation had assassinated Smith and “driven the Saints from their midst.” At the first Pioneer Day celebration in Salt Lake in 1849, Phineas Richards, a Church leader whose sons served as electioneers, captured the general feeling in a ceremonial speech. “It devolves upon us, as a people instructed by the revelations of God, with hearts glowing with the love of our fallen country, to revive, support, and carry into effect the original, uncorrupted principles of the Revolution and the constitutional government of our patriotic forefathers.” Together they would “replant the standard of liberty . . . [and] prove to the United States that when they drove the Saints from them . . . they . . . drove [out] the firmest supporters of American Independence.” As part of the wider restoration, they would restore the government into a “theodemocracy . . . [that would grow] from territory to territory, from state to state, from nation to nation, from empire to empire, from continent to continent.” [54]

After three years at Winter Quarters, the Tracys entered the Salt Lake Valley in 1850. What they found on arrival was the provisional State of Deseret—the aristarchic theodemocracy of Joseph Smith’s Nauvoo, now writ large on over three dozen settlements throughout the Great Basin. Church leaders were nominated to serve in corresponding political offices and the male population assented by voting for them. Such elections occurred virtually unopposed for two decades. Thus, Church president Brigham Young was also the governor, the apostles served in the territorial council, local bishops or branch presidents were also mayors and judges, and so on. Unsurprisingly, general Church leaders chose many former electioneers for these religious-political roles. They had sacrificed to preach and electioneer for theodemocracy alongside the apostles and experienced with them the shared trauma of Smith’s assassination while campaigning for him. In the unsettled West, they were a ready-made cadre of theodemocratic workhorses, emotionally and ideologically aligned to build the new Zion.[55]

In 1851 when Deseret instead became the smaller Utah Territory, this theodemocractic system shifted, seamlessly creating an imperium in imperio and fifty years of conflict with America, dubbed the “Mormon Question.”[56] While aristarchic theodemocracy continued, the language to describe it did not. In part to avoid the scrutiny of Americans wary of Mormon loyalty, Latter-day Saints used the term “kingdom” or “kingdom of God” (often capitalized) under the leadership of the “priesthood.” While “church” and “kingdom” were synonymous to nineteenth-century American Protestants (as well as twentieth- and twenty-first-century Latter-day Saints), for contemporary Mormons, the “kingdom” was the separate aristarchic (priesthood), theodemocratic kingdom that grew out of the Church and was destined in time to lead the nations immediately before and following Christ’s return.[57] The labels changed, but the eschatological lens remained.

The Tracys settled in Ogden, where fellow electioneer Lorin Farr, the stake president of Weber County and mayor of Ogden, assigned Moses to the high council and subsequently to county government roles. But what of Nancy, the lone female electioneer? Theodemocracy still inherited America’s diminutive political space for women. While her cherished theodemocratic Zion protected her freedom to worship, it still restricted her politically—at least for a time.

Nancy and Moses went to work establishing their farm and new community. Like so many of their fellow Saints, they started building a life again with little more than determination, courage, and the hope born of the freedom to worship far from other American citizens and their governments. But in time, non Latter-day Saint federal officials grew wary of Utah’s thinly veiled combination of church and state and its now-public practice of polygamy. National politics fueled contention between the Latter-day Saints and the federal government. In 1856 the nascent Republican Party, determined to “prohibit in the territories those twin relics of barbarism, polygamy and slavery,” strongly opposed the Democratic doctrine of popular sovereignty, which would allow slavery’s territorial expansion and a functional theocracy in Utah.[58] In 1857 newly elected President James Buchanan, a Democrat, sent a military expedition to quell a rumored rebellion in Utah and depose Brigham Young as governor, a perfect distraction from the sectional discord on display in Bleeding Kansas.[59] When Young became aware that a federal army was approaching with unknown intentions, and with thoughts of Missouri and Illinois in his mind, he declared martial law in the territory. Young eventually ordered thirty thousand Saints in northern Utah to evacuate south.

For the Tracys, this latest exodus from government-sanctioned persecution would again be tragic. Moses, who had been ill for several months, began having strokes during the evacuation. Nancy had just given birth to the couple’s only daughter and her adult sons were away defending the territory. Having only her fourteen-year-old to assist, she feared Moses would die any day. “It was even worse than crossing the plains,” Nancy remembered of this trip. “In all our married life or ever since we joined the Church of Latter-day Saints it had been one continual scene of persecution, traveling from one place to another to find a resting place from our enemies.”[60] Each time it had cost a family member’s life. This occasion would be no exception. When the word came to return, Nancy led her family back to Ogden. Ironically, they arrived home from their final government-induced exodus on Independence Day 1858. Moses died just weeks later. A neighbor helped Nancy bury him without a funeral service. In Salt Lake, the new federally appointed governor replaced Brigham Young, and further to the southwest, the “occupying” army constructed Camp Floyd to keep an eye on Utah. When Nancy buried her husband, little did she know that it was the beginning of a three-decade decline of their Zion theodemocractic kingdom due to the increasing friction with federal officers, civil and military.

This time Nancy remembered no anger but felt “very lonely and . . . completely worn down with the toil and hardships of which my whole life had been made up after embracing the gospel.” She and the children suffered for lack of food that winter and throughout the following year as she struggled to manage the farm, later remembering, “It was new to me to have to manage outdoor affairs and I was not equal to the task.” Again facing uncertainty, Nancy turned to her faith. “I always felt that my religion was worth more to me than anything in the world,” she remarked, “and I felt determined to live it.”[61] Nancy knew her religion well and found a solution. Her farm bordered that of her late husband’s brother, thirty-year-old Silas Tracy, who already had two wives. Nancy, a noted “scriptorian,” reminded him of the biblical requirement to marry his brother’s widow. Thus, Nancy became a plural wife to Silas in 1860 and gave birth to her last child in 1861. The arrangement worked well for Nancy but brought tension for her younger new husband and his wives—as her strong personality created some friction with the youngest wife, who later divorced Silas.[62] Nancy found some rest and stability in plural marriage to raise her last children, but her struggle for religious freedom was far from over.

The transcontinental railroad’s approach promised to bring more outsiders and their culture to Utah, threatening Zion and her protective theodemocracy. America was invading again, but this time culturally and with a Republican Party bent on stamping out polygamy as they had slavery. One way Brigham Young sought to defend Zion was by authorizing veterans of the Nauvoo Relief Society to re-create the organization in every congregation in the Great Basin. In 1866 Eliza Snow, who would become the new general president of the Relief Society, helped create the Marriott Ward’s organization, choosing Nauvoo-veteran Nancy as first counselor. Nancy likely would have been chosen as the president in her ward had her first husband and fellow electioneer Moses lived, since Relief Society presidents were often wives of local leaders. Instead, the younger wife of the Marriott Ward bishop was chosen. Nevertheless, “We labored energetically,” Nancy recalled, “. . . being helpers to the priesthood in all we could in every way.”[63] She again relished the political and social space the renewed Relief Society gave her. As in Nauvoo, women of the Relief Society “assumed new ecclesiastical, economic, and political roles in the expanding Mormon community.”[64] Particularly, she enjoyed working with old comrades from the Nauvoo Relief Society and hearing theodemocratic-tinged messages such as Eliza Snow declaring, “Sisters, . . . our position as Saints of the Most High is at the head of the world.”[65] Nancy was also present when Snow shared her experience of meeting Queen Victoria and told the assembled women, “You, my sisters, if you are faithful will become Queens of Queens, and Priestesses unto the Most High God.”[66] For over thirty years, Nancy donated money, food, and even land to the Relief Society for the needy, for missionaries, for temples, and, predictably, for the Utah delegation of the National Women’s Association. Her most valuable donation to the society was land for an orchard of mulberry trees to raise silkworms.[67] As a leader, Nancy assisted in teaching the younger sisters the parliamentary functions of the society and in encouraging them to greater spirituality and self-sufficiency through home manufacturing. She also assisted in the effort to create the United Order and testified of and defended plural marriage.[68]

When the railroad arrived in 1869, it literally split Nancy and Silas’s properties, but its attendant influence initially failed to split Utah’s “theo” from its “democracy.” In East Coast circles, some talked of giving suffrage to Latter-day Saint women, assuming they would vote themselves free of polygamy and theocracy. Their numbers would add to disaffected Latter-day Saints and gentile residents who had formed the Liberal Party to challenge the Church’s theodemocratic nominations, now functioning as the People’s Party. In late 1869 the Cullom antipolygamy bill was introduced in Congress. It would strip male polygamists of their rights to vote, sit on juries, and run for office. Relief Societies organically held “Indignation Meetings” in January, February, and March 1870, decrying the legislation as another attack on their free exercise of religion to practice plural marriage. They resolved to “unitedly exercise every moral power, every right which we inherit as the daughters of American citizens” to protect the rights of their husbands, fathers, and sons. Phoebe Woodruff, Nancy’s personal friend since Nauvoo, thundered, “If the rulers of our nation will so depart from the spirit and letter of our glorious Constitution as to deprive us . . . of citizenship . . . let them . . . make prisons large enough to hold their wives for where they go, we will go also.”[69] The articulate activism of Latter-day Saint women surprised national observers and encouraged Church leaders. Relief Society leaders used the newly created political space to call for suffrage and the male territorial legislature enfranchised them in February 1870, making Nancy and other Utahn women the first in the nation to vote. They cast their ballots for the Church’s candidates, further entrenching theodemocracy. This was “doubly transgressive supporting two practices—polygamy and female suffrage—very much at odds with 19th-century American culture.”[70]

Nancy attended the Ogden indignation meeting in March 1870.[71] She was overjoyed to join her sisters in the fight for religious liberty. The individual Relief Societies, as one historian noted, “functioned as ‘miniature democratic laboratories,’ teaching their members self-government.”[72] However, they and the wider Church received significant pushback from the nascent Liberal Party and the small but heavily financed territorial Republican party. Nancy likely read news of the 1872 Utah Republican Party Convention in Corrinne, not far from her Ogden home. One of the party’s central committee’s most outspoken members against the Latter-day Saints was a California transplant who managed Wells Fargo’s Overland Express and Bank in Salt Lake City.[73] In a note of irony, his name was Theodore F. Tracy, the identical name of Nancy’s fifth son who died just after she and Moses had served their electioneering mission for religious liberty.

Throughout the 1870s and 1880s, Nancy took an increasingly active leadership role in the Marriott Relief Society and continued her support of candidates nominated by Church leaders. The minutes record her teaching, encouraging, leading, and defending the Saints’ religious liberty. In 1874, the Poland Act effectively removed Latter-day Saints from the Utah territorial justice system to enable successful prosecution of polygamists. A few months later, Nancy presided over a meeting where they discussed “Joseph Smith offering himself for the presidency of the United States and his views and intentions if they had received him [along with] many interesting remarks.”[74] Nancy often shared her life experiences to her Relief Society sisters, perhaps including stories of her mission with Moses during Smith’s campaign. She certainly still saw the world through the lens of theodemocracy, as she mentioned a few months after the meeting that “the Kingdom of God will eventually govern the earth.”[75] In early 1876 she presided over a meeting where instruction was given to “be subject to the priesthood in all things Spiritual and Temporal” and that the Relief Societies’ “duties would be multiplied in the future.”[76] Interestingly, the July 3, 1876, meeting made no mention of the nation’s centennial the next day or any plans for celebration. Although there was a parade and celebration in Ogden, Nancy made no mention of it in her reminiscences.[77] When attendance to the monthly meetings dipped, Nancy chastened the sisters for making excuses: “these relief societies were not organized for nothing. We have work to do” to have “the people prepared to meet [Christ] and a holy place for him to come to.”[78]

That work became more difficult in 1881 when Silas died, and her stalwart son Henry left on a mission.[79] Henry had been sent to England in part to avoid prosecution for polygamy due to the ever-stricter federal antipolygamy legislation and enforcement. With Reconstruction over in the South, the still ascendant Republican Party turned towards Utah to eliminate the other “relic of barbarism,” polygamy. In a world of Victorian morality and its cult of domesticity, plural marriage was an abomination and female enfranchisement was presumptuous. For national political leaders, widespread antipolygamy sentiment was the perfect weapon with which to bludgeon Utah’s theodemocracy. In 1886, Congress debated the Edmunds-Tucker Act that would unincorporate the Church, disenfranchise most Latter-day Saint men, and specifically disenfranchise all women. Having exercised the right to vote for sixteen years, Nancy and Latter-day Saint women fought to keep it. Again, Relief Societies were centers of political organization. They gathered in large numbers throughout the territory and even in Washington, DC, to petition and protest. However, when the act passed the Senate, and with her favorite son Henry in prison convicted of polygamy, Nancy expressed in a meeting that she “felt it was a solemn time [and] there was not much time for laughter or dancing or foolishness.”[80] As the House of Representatives deliberated, Nancy contributed to a fund financing the female Latter-day Saint delegation in Washington and prayed with her sisters that the delegation would have “influence with the nation for good.” Later she stirred the sisters to Zion unity, “to be on one side or another” and not lukewarm.[81]

All their efforts ultimately failed, and the act became law in 1887. Undaunted, sixty-two-year-old Nancy kept the fight for religious liberty alive in her Relief Society. For example, she participated in a May 1887 discussion over “our Political affairs.” In June 1888 she rallied the society by reading non Latter-day Saint Jeremiah Wilson’s fiery speech to Congress defending the Latter-day Saints’ right to worship, and in the following meeting she declared, “We could not do too much in the Church and Kingdom of God.”[82] Like her 1885 reminiscence, her language in Relief Society became increasingly apocalyptic. Her input and leadership at this point was so important that when she fell ill, they held their meetings at her home. However, the Edmunds-Tucker Act had its intended consequence of suppressing the Latter-day Saint vote, and in 1889 the Liberal Party defeated the People’s Party in the Ogden municipal elections. The next year they would win in Salt Lake City, and the US Supreme Court would rule the Edmunds-Tucker Act constitutional.[83] Church President Wilford Woodruff, and Nancy’s longtime friend and fellow electioneer, soon announced a revelation that the Church would cease plural marriages (Doctrine and Covenants, Official Declaration 1). Nancy’s 1880 and 1885 reminiscences strongly defended plural marriage, as did several remarks she made over the years in Relief Society. No longer a plural wife, Nancy’s remarks in the second Relief Society meeting after the Manifesto interestingly included gratitude for being led by a prophet and the “great privilege to meet in peace.”[84]

Now in her mid-seventies, Nancy fought for her voting rights to be restored. She continued to donate to that cause as Jane Richards, the Weber Stake Relief Society president, friend, and fellow veteran of the Nauvoo Relief Society, briefed her about “women’s suffrage and [Richards’] visit to Washington DC” to meet with Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.[85] But ending polygamy was not enough if the Latter-day Saints wanted to finally be admitted as a state. To build the relationships needed in national politics to secure statehood and amnesty and thus regain self-rule and civil rights, Utahns would need to join the national two-party system. The last thread of theodemocracy was cut when Church leaders disbanded the People’s Party in 1891 and directed Latter-day Saints to join the Democratic or Republican Parties.[86] Most Latter-day Saints fit naturally into the Democratic Party since the Republican Party had been their oppressors for decades. Yet others saw opportunities with the Republicans. The resulting disunity called forth prophetic cautions to the Church within a year.[87] Despite the differences, in 1895 a constitutional convention drafted the Utah Constitution, reinstating female enfranchisement, which was accepted by Congress. On January 4, 1896, Utah became a state.

In the months after statehood, Nancy wrote her third and most comprehensive reminiscence, recording her memories and thoughts during this turbulent time of transition—the twilight of her life and of her cherished Zion theodemocratic kingdom. This 1896 account was again directed to her posterity but with the express purpose of “detail[ing] the outlines of my travels and persecutions for the Gospel’s sake.” Federal restrictions on Latter-day Saint civil rights had eased in recent years, yet her final reminiscence again memorialized persecution. Other female Latter-day Saints words and writings moved away from themes of persecution and apocalypse and toward the new post-Manifesto realities.[88] Not Nancy’s. In 1893 her son Henry died at only forty-four years old, having never recovered from the illness he contracted while imprisoned as a polygamist.[89] Now she had lost four children and her first husband because of persecution for religious practices.

As her narrative arrived in the present, she noted with irony that the “Gentiles” had established their various churches in Utah and “worshiped as they pleased,” unmolested by the Saints or their government. “But did they give us that privilege when we dwelt with them?” she rhetorically asked. “No, verily no. We were cast out from among them, persecuted, and our leaders slain.” “There is one thing sure,” she later continued, “the Gentile world will be left without excuse so far as our complying with the laws that they have made regarding our religious convictions. We have complied with them. We have not been allowed the liberty of conscience, which other people have enjoyed and which the constitution guarantees for us to worship as we please.”[90] For Nancy, gentile America remained political Babylon, with leaders that continued to corrupt the Constitution. She could not follow President Grover Cleveland’s counsel for Latter-day Saints to become like other Americans. She had been called to “gather” and “stand in holy places” and to “flee to Zion for safety.”[91] Yet in 1896, as in 1844, religious liberty for Americans still reflected a Protestant outlook, where polygamy and church-directed electoral politics fell outside the boundaries of that liberty. Church leaders had chosen to pay the price of entry rather than see the Church destroyed.

In the five years after the Church disbanded the People’s Party, differences over politics created heated conflicts amongst the Saints, to the extent that Wilford Woodruff felt compelled to address the subject in the Church’s general conference. “Every man has as much right . . . to his political convictions as he has to his religious opinions,” he explained. He then implored, “Don’t throw filth and dirt and nonsense at one another because of any difference on political matters. . . . That spirit will lead us to ruin.”[92] Nancy wholeheartedly agreed that too many Saints were politically “partak[ing] of the spirit of the world” and she did “not believe the Lord is pleased with it.”[93] It was painful for Nancy to see Church members, including her own children and grandchildren, splitting into Democrats and Republicans, creating division and strife in a political realm that had known Zion’s unity for half a century. Previous persecutions had denied them religious liberty but had united the Saints. This adversity, however, was causing division, particularly intergenerationally. To Nancy, the younger generations seemed to care more about dressing, acting, and voting like the rest of America than building the Zion Kingdom.

Joseph Smith’s campaign phrase, “Unity is power,” that Nancy and Moses proclaimed while electioneering and that they had lived under in Utah came echoing back to her. "We are told to be united,” she penned, “for in union is strength.”[94] So too did the anti-partisan campaign message she and Moses shared back in 1844: “We have had Democratic presidents; Whig presidents; . . . and now it is time to have a president of the United States.”[95] The Saints, she wrote, should “stand neutral and have nothing to do with either party rather than be wrought up to the pitch that some are at the present time.”[96] These words conflicted with Church leaders’ decision to encourage the members to participate in a national party of their choosing and differed from most female Saints of her generation. Helen Mar Kimball Whitney, previously as determined and published as any female defender of plural marriage and of memorializing past persecution, by this time had moved on. She recorded in her diary that she was a committed “democrat and a believer in women’s rights.”[97]

Nancy Naomi Alexander in her later years.

Nancy Naomi Alexander in her later years.

Church leaders had acted pragmatically to save the Church and regain some form of political self-rule. Nancy still believed in the Kingdom of God. What good was statehood and reinstatement of the female franchise if she could not vote theodemocratically? Nancy felt great dissonance at the turn of events, along with some other surviving peers of Zion’s first generation. They had fought for and lived long enough to see the beginning of their people’s longed-for religious liberty, but at the cost of so much that they had believed in, sacrificed for, and even watched loved ones die for. The celebrations of statehood that year did not interest her, and she did not attend them. Yet she admitted, “it was a great time for our young folks”—younger generations inheriting a different world and relationship with America, one she did not care for, one that had cost Zion too much.[98]

“What does it all mean?” Nancy questioned, “The divisions and strife in the political field: some for one party and some for another?” “There must be a policy [reason] unseen by me.” Perhaps like those who thought the Manifesto was only a public relations ploy by Church leadership to placate Americans, Nancy may have believed that the division over politics was similarly a ruse that would soon be reversed. After 1891, apocalyptic language faded for those like Helen Mar Kimball Whitney who had used it profusely. But not so for Nancy. She pondered that perhaps “the crisis is at our doors . . . [where] our people would be the only ones that would hold the constitution together after our enemies had torn it to shreds.” Or perhaps all the confusion was a portent of Christ’s imminent return as “King of Kings . . . to set up his own government.” Either way, all the current strife and contention would vanish, and the Saints would again “with [one] accord . . . vote the same ticket.”

If Church leaders and most of the membership had moved on in the process of Americanization, she stubbornly held to her beliefs, ones that gave her “consolation and satisfaction to know that we shall eventually become the head and not the tail. This is worth living for, and, if needs be, to die for.”[99] Writing those words, her thoughts may have drifted to five graves, three likely lost to memory: two side-by-side in Nauvoo for William and Theodore, both two years old, and one under a railroad near Council Bluffs for eleven-year-old Lachoneus. At least she and three generations of living descendants could visit the graves of her first husband Moses and her son Henry in Ogden Cemetery. Nancy saw her deceased family members as martyrs of Zion and of the fight for religious freedom in the United States.

Nancy herself would outlive theodemocratic Zion by only six years. Her few diary entries in those years speak of only weddings, funerals, Relief Society meetings, genealogy, and temple work. In her own way, she seemed to have come to terms with Zion’s new direction. Fittingly, she passed on March 11, 1902—the fifty-eighth anniversary of the Council of Fifty that, in 1844, had sent Nancy and Moses to electioneer for religious liberty. Her grandsons and granddaughters now enjoyed the religious and political rights for which she had fought and suffered. Before passing, she inscribed the last stanza of a poem regarding statehood written by her new twenty-year-old granddaughter-in-law Emma Peterson Tracy:

We are surrounded with lofty mountains

Cities have been built and temples reared

The valley blossom as the rose;

Fair Utah, she is the queen of the West

Where the Saints will in peace find rest.[100]

The poem reflects on the legacy of Nancy and her pioneer peers through the eyes of the third generation of Latter-day Saints. Their parents and grandparents had labored to build cities and temples in the wilderness where religious bigotry had banished them. The last two lines of the poem spoke to this younger generation’s hope for the future. After decades of persecution, the compromises surrounding statehood had established relative peace with the rest of the nation. Instead of conflicting with America, “Fair Utah” was now set on a course to become a crowning example of what it meant to be American. A half century later, in the post–World War II era, Latter-day Saints even came to be seen as the epitome of what it meant to be American. They had rugged ancestral roots, patriotic fervor, strong emphasis on the nuclear family, an apostle in the president’s cabinet, and “America’s Choir.”

Conspicuously absent in the poem, however, was Zion or the Kingdom of God, the central cause of Nancy’s generation. She likely interpreted the last two lines differently than her granddaughter-in-law. Nancy and her peers had attempted to build a society separate from the “world” that offered “peace” and “rest” to the Saints and anyone who wished safety from the prophetic calamities preceding Christ’s return. Zion would not be the “Queen of the West” but the “Queen of the Earth,” prepared to receive the arrival of the “King of Kings.” Their vision of Zion’s mission, however, had been outside the boundaries of acceptable religion in nineteenth-century America. The Zion Nancy had devoted her life to was not the same one she saw as her eyesight dimmed in her final years. As she neared death, her thoughts turned to her female friends from the Nauvoo Relief Society who had already passed. “They had fought a good fight, kept the faith, and have gone from this earth to a higher and nobler sphere of action,” penned Joseph Smith’s only female electioneer. “When my time comes, I hope to enjoy the society of these noble women and labor with them on the other side, as I have done here upon this earth.”[101]

Notes

[1] “Nancy A. Tracy Reminiscences and Diary, May 1896–July 1899,” 61–62, MS 4525, Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (hereafter CHL).

[2] Nancy Tracy wrote three reminiscences. She wrote the first in 1880 for noted historian Hubert Howe Bancroft. “Narrative by Nancy N. Tracy,” 1880, The Utah Manuscripts Collection, Hubert Howe Bancroft Library (hereafter HHBL), University of California at Berkeley. There is a typescript copy of this account in “Nancy Alexander Tracy autobiographical writings,” MSS 2198, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University (HBLL). It is also available online as Nancy Naomi Alexander Tracy, “Life History of Nancy Naomi Alexander Tracy,” typescript, http://

[3] See “Mrs. F. D. (Jane) Richards, Reminiscences,” 1880, The Utah Manuscripts, HHBL; Phoebe W. Woodruff, “Autobiographic Sketch,” 1880, HHBL. See also Jeni Broberg Holzapfel and Richard Neitzel Holzapfel eds., A Women’s View: Helen Mar Whitney’s Reminiscences of Early Church History (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011).

[4] Tracy, “Narrative,” 31–32.

[5] Tracy, “Autobiography,” 11.

[6] Tracy, “Autobiography,” 30. For other examples see, Helen Mar Kimball Whitney’s diary entries from April 7, 1885, and November 10, 1885, in Hatch and Compton, Widow’s Tale. Another example is “Eliza Snow, Discourse, July 24, 1871” in Jill Mulvay Derr, Coral Cornwall Madsen, Kate Holbrook, Matthew J. Grow, eds., The First Fifty Years of Relief Society: Key Documents in Latter-day Saint Women’s History (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2016), 368. Kingdom is capitalized whenever the meaning is the wider idea of an actual political kingdom and not just the Church.

[7] Tracy, “Autobiography,” 29.

[8] Tracy, “Reminiscences and Diary,” 2.

[9] For Francis Jones, see “Jones, Francis,” in Massachusetts, Secretary of the Commonwealth, Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War (Boston, MA: Wright & Potter Printing, 1896–1908), vol. 8, accessed through Massachusetts, U.S., Soldiers and Sailors in the Revolutionary War (Provo, UT: Ancestry.com Operations, 2004); for Solomon Tracy, see “United States Rosters of Revolutionary War Soldiers and Sailors, 1775–1783,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://

[10] Tracy, “Reminiscences and Diary,” 6.

[11] Tracy, “Reminiscences and Diary,” 7–8.

[12] Roger D. Launius “Alexander Doniphan and the 1838 Mormon War in Missouri,” John Whitmer Historical Association Journal, vol. 18 (1998), 63.

[13] Tracy, “Autobiography,” 7.

[14] Tracy, “Reminiscences and Diary,” 19.

[15] Tracy, “Reminiscences and Diary,” 20.

[16] Moses Tracy, Affidavit, May 7, 1839, Adams County, Illinois, in Clark V. Johnson, ed., Mormon Redress Petitions: Documents of the 1833–1838 Missouri Conflict (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1992), 367.

[17] Spencer W. McBride, Joseph Smith for President: The Prophet, the Assassins, and the Fight for American Religious Freedom (Oxford University Press, 2021), 209.

[18] Joseph Smith History, E:1804 (14 Dec 1843), The Joseph Smith Papers (JSP). This quote was written in 1855 in the creation of the Joseph Smith History. Like many quotations in these volumes, there is no attribution to its source. If not Joseph’s actual words, he certainly was using similar language in December of 1843. For example, in a pamphlet that month addressed to his native state of Vermont he asked, “Has the majesty of American liberty sunk into such vile servitude and oppression, that justice has fled?” Joseph Smith, “General Joseph Smith’s Appeal to the Green Mountain Boys, December 1843,” 6, JSP, https://

[19] Tracy, “Autobiography,” 14.

[20] “Aristarchy,” Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language Dictionary (Springfield, MA: G&C Merriam & Co., 1828).

[21] Joseph Smith, “The Globe,” Times and Seasons, Nauvoo, Illinois, April 15, 1844, 510; original capitalization preserved.

[22] Sarah Granger Kimball, “Reply to ‘A Man’s Advice About Woman Suffrage,’” Woman’s Exponent 10, no. 11 (December 1, 1891), 81, as found in Katherine Kitterman, “‘No Ordinary Feelings’: Mormon Women’s Political Activism, 1870–1920” (PhD diss., American University, 2021), 162; see Kitterman, “No Ordinary Feelings,” 31–71. See also Kim M. Davidson, “More Than Faith: Latter-day Saint Women as Politically Aware and Active Americans, 1830–1860” (master’s thesis, Western Washington University, 2017) and Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, A House Full of Females: Plural Marriage and Women’s Rights in Early Mormonism, 1835–1870 (Vintage Books, 2017).

[23] “Nauvoo Relief Society Minute Book,” JSP, 1–5, https://

[24] Nancy was admitted at the society’s fourth meeting on April 14, 1842. See “Relief Society Minute Book,” 27.

[25] Benjamin E. Park, Kingdom of Nauvoo: The Rise and Fall of a Religious Empire on the American Frontier (New York: Liveright Publishing, 2020), 6

[26] Davidson, “More than Faith,” 88.

[27] Nancy Tracy, signatory, “Scroll Petition,” November 28, 1843, in Johnson, Mormon Redress Petitions, 584.

[28] Eli A Tracy, “Autobiography,” typescript, Special Collections, HBLL, 1.

[29] Park, Kingdom of Nauvoo, 159–60.

[30] Recent scholarship has definitively demonstrated that even if quixotic, Smith’s campaign was a serious attempt engaging significant resources. See McBride, Joseph Smith for President; Park, Kingdom of Nauvoo; and Derek R. Sainsbury, Storming the Nation: The Unknown Contributions of Joseph Smith’s Political Missionaries (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2020).

[31] Joseph Smith Jr., “General Smith’s Views of the Powers and Policy of the Government of the United States, circa 26 January–7 February 1844,” JSP, https://

[32] General Smith’s Views, 8.

[33] For a discussion of the Council of Fifty and theodemocracy, see McBride, Joseph Smith for President, chap. 8; Park, Kingdom of Nauvoo, 198–281; Sainsbury, Storming the Nation, chaps. 2, 4; and Matthew J. Grow and R. Eric Smith, eds., The Council of Fifty: What the Records Reveal about Mormon History (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017).

[34] Sainsbury, Storming the Nation, 31–57.

[35] Tracy, “Reminiscences and Diary,” 27.

[36] In her 1880 account she mentioned it was Hyrum Smith, in her 1885 account she named Joseph and Hyrum Smith, but in her 1896 account she mentioned only Joseph Smith.

[37] The 1880 account of the electioneering had 80 words, the 1885 had 500, and the 1896 had 1,286. For comparison, the 1885 had a total word count increase 223 percent from the 1880 narrative, but the word count increase for the electioneer mission was 625 percent. The 1896 account had a total word count increase from the 1885 account of 224 percent, but the increase for the electioneer mission was 257 percent.

[38] “Missionary Certificate,” June 3, 1844, Moses Tracy Papers, 1836–1857, CHL. Electioneers were instructed to preach and politick along their journeys with everyone “male and female.”

[39] Tracy, “Autobiography,” 19 (“He advocated Brother Joseph’s views on the Powers and Policy of the Government”); Tracy, “Reminiscences and Diary,” 28–29. The Tracys arrived in New York on June 20 and could not have heard of Joseph Smith’s murder before July 11. They visited, taught, and campaigned with Nancy’s family no longer than a week, leaving two other weeks for them to have preached and politicked.

[40] Fern Elizabeth Devries, “Silas Horace Tracy,” undated, CHL, 1.

[41] Nauvoo Expositor, Nauvoo, Illinois, June 7, 1844, 1.

[42] “Nauvoo City Council Rough Minute Book, February 1844–January 1845, 18, JSP, https://

[43] Electioneers in Syracuse, New York, fifty miles south of Ellisburg, New York, first receive confirmed reports on 11 June 1844. The news could have only arrived in Ellisburg on that date or likely a day or two later.

[44] Tracy, “Reminiscences and Diary,” 29.

[45] Tracy, “Autobiography,” 18.

[46] Franklin D. Richards, “Journal of Richards, Franklin D., Journal No 2,” May 1844–July 27, 1844, typescript, CHL, 22. Nancy mentions the letter in Tracy, “Reminiscences and Diary,” 30.

[47] Tracy, “Reminiscences and Diary,” 30. Nancy does not mention what was out of order, but it was likely challenges to the apostles’ succession by missionaries of Sidney Rigdon or James J. Strang. Other electioneers record these conflicts in the eastern branches of the Church.

[48] Tracy, “Reminiscences and Diary,” 32.

[49] Amasa Lyman, “Journal,” June 4, 1844—March 16, 1845, CHL, 13.

[50] Tracy, “Autobiography,” 19.

[51] Tracy, “Autobiography,” 19.

[52] Tracy, “Reminiscences and Diary,” 33.

[53] Eli A. Tracy, “Autobiography,” Special Collections, HBLL, 2.

[54] Phineas Richards as found in Eliza R. Snow, Biography and Family Record of Lorenzo Snow (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1884), 103–5. See also Sainsbury, Storming the Nation, 190–210, and Davidson, “More Than Faith,” 61–68.

[55] Sainsbury, Storming the Nation, 195–96.

[56] See Brent M. Rogers, Unpopular Sovereignty: Mormons and the Federal Management of Early Utah Territory (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2017), particularly chapter 1.

[57] This concept was clearly taught in the Council of Fifty in 1844, whose name was officially “The Kingdom of God and His Laws with the Keys and Power thereof, and Judgment in the Hands of His Servants, Ahman Christ.” It was publicly taught throughout Utah from 1847 through late 1880s. In addition to the above-mentioned 1849 Pioneer Day speech, see, for example, Parley P. Pratt, “The Standard and Ensign,” in Journal of Discourses (Liverpool: F.D. and S. W. Richards, 1854), 1:172–85; Brigham Young, “The Kingdom of God,” in Journal of Discourses (Liverpool: F. D. and S. W. Richards, 1855), 2:309–17; and Orson Pratt, “The Kingdom of God,” in Journal of Discourses (Liverpool: Orson Pratt, 1856), 3:70–74. Throughout the Marriott Ward Relief Society minutes of 1870s and 1880s, Nancy Tracy and others testified of the “church” and the “kingdom” in contexts that demonstrate they understood they were talking about separate organizations. Theodemocracy was also often called “true Republicanism” (the political ideology not political party). See Rogers, Unpopular Sovereignty, 151.

[58] Republican Party Platform, https://

[59] See Rogers, Unpopular Sovereignty, chapter 4, “Bleeding Kansas, 1953–1861,” People and Events, https://

[60] Tracy, “Reminiscences and Diary,” 48–49.

[61] Tracy, “Autobiography,” 29.

[62] Silas Tracy, “Autobiography,” 3.

[63] Tracy, “Reminiscences and Diary,” 54.

[64] Derr et al. First Fifty Years of the Relief Society, 247.

[65] Eliza R. Snow in Salt Lake City Seventeenth Ward, Salt Lake Stake, Relief Society Minutes, vol. 2, 1868–1871, CHL, February 18, 1869, 149.

[66] Eliza R. Snow, “Discourse, August 14, 1873,” in Derr et al. First Fifty Years of the Relief Society, 388.

[67] Marriott Ward Relief Society minutes and records, 1869–1973, vol. 1, CHL. The first volume of minutes is almost exclusively records of contributions and expenditures from 1869 to 1895. Nancy contributed on a regular business in cash and in goods. In 1879 she gave the Marriott Relief Society an acre lot of her land, valued at $51.20, to plant a mulberry orchard for the harvesting of silkworms. Nancy stated she was at the center of this effort at home-manufacturing. See Tracy, “Reminiscences and Diary,” 54.

[68] Marriott Ward Relief Society minutes, vol. 2. For parliamentary rules, see December 18, 1874. For United Order, see December 1, 1874. For information on the United Orders, see “United Orders,” Church History Topics, https://

[69] “Great Indignation Meeting,” Deseret News, January 14, 1870, 2.

[70] Katherine Kitterman, “Utah Women Had the Right to Vote Long before Others—and Then Had It Taken Away,” Washington Post, February 14, 2020, https://

[71] Weber Stake Relief Society Conference Minute Book, 1855–1869, CHL, 14.

[72] Desdemona Wadsworth Fuller, cited in Jull Mulvay Derr, Janath Russell Cannon, and Maureen Ursenbach Beecher, Woman of Covenant: The Story of Relief Society (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 201), 26.

[73] Ronald Collett Jack, Utah Territorial Politics: 1847–1876 (Salt Lake City: Department of Political Science, University of Utah, 1970), 281; W. Turrentine Jackson, “Salt Lake City: Wells Fargo’s Transportation Depot During the Stagecoach Era,” Winter 1985, v. 53, n1, Utah Historical Quarterly, 24–27, 36–37.

[74] Marriott Ward Relief Society minutes, vol. 2, January 26, 1875.

[75] Marriott Ward Relief Society minutes, vol. 2, [undated] July 1875.

[76] Marriott Ward Relief Society minutes, vol. 2, January 25, 1876.

[77] The Ogden celebration was referenced in Deseret News, July 12, 1876.

[78] Marriott Ward Relief Society minutes, vol. 2, October 3, 1876, November 27, 1876.

[79] Marriott Ward Relief Society minutes, vol. 1, [undated] 1881.

[80] Marriott Ward Relief Society minutes, vol. 2, March 2, 1886.

[81] Marriott Ward Relief Society minutes, vol. 2, May 11, 1886; vol. 3, December 22, 1886.

[82] Marriott Ward Relief Society minutes, vol. 3, May 1887; June 5, 1888; [undated] July or August 1888.

[83] The same Supreme Court justices would rule in six years for legal “separate but equal” discrimination against Blacks in the infamous Plessy v. Ferguson.

[84] Marriott Ward Relief Society minutes, vol. 3, November 4, 1890.

[85] Marriott Ward Relief Society minutes, vol. 3, Mar 24, 1891.

[86] Thomas G. Alexander, Utah: The Right Place; The Official Centennial History (Salt Lake City: Gibbs-Smith, 1995), 201–3.

[87] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Saints, vol. 2: No Unhallowed Hand (Church Historian’s Press, 2020), 647.

[88] For example, Hatch and Compton, A Widow’s Tale, 30.

[89] Tracy, “Reminiscences and Diary,” 55.

[90] Tracy, “Reminiscences and Diary,” 61–62; emphasis added.

[91] Tracy, “Reminiscences and Diary,” 61.

[92] “General Conference,” Deseret Evening News, April 5, 1892, 4, as found in Saints, vol. 2, 647.

[93] Tracy, “Reminiscences and Diary,” 61.

[94] Smith, Views, 2; Tracy, “Reminiscences and Diary,” 60.

[95] Smith, Views, 11. Emphasis in the original.

[96] Tracy, “Reminiscences and Diary,” 61.

[97] Helen Mar Kimball Whitney as quoted in Hatch and Compton, A Widow’s Tale, 30.

[98] Tracy, “Reminiscences and Diary,” 64.

[99] Tracy, “Reminiscences and Diary,” 60, 62.

[100] Tracy, “Reminiscences and Diary,” 67.

[101] Tracy, “Reminiscences and Diary,” 63.