The Influence of Family Size, Interaction, and Religiosity on Family Affection in a Mormon Sample

Melvin L. Wilkinson and William C. Tanner III

Melvin L. Wilkinson and William C. Tanner III, “The Influence of Family Size, Interaction, and Religiosity on Family Affection in a Mormon Sample,” in Religion, Mental Health, and the Latter-day Saints, ed. Daniel K. Judd (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1999), 93–106.

Melvin L. Wilkinson was systems specialist at First Security Information Technologies and William C. Tanner III was executive director at Active Psychotherapy Centers when this was published. This article was previously published in the Journal of Marriage and the Family 42:297–304; reprinted with permission.

Abstract

This 1980 study focuses on the influence of family size in relation to family affection among Latter-day Saints. Active adolescent members of the LDS Church completed questionnaires wherein they were asked about the five basic elements of affection as defined by Stevens (1955). Results show that larger LDS families tend to participate in more activities together. Also, the mother s attitude in the home has a stronger impact on the family than does the father’s. The mother is thought of as being more affectionate, understanding, and accepting in large families. Interestingly, families in which the parents attend the temple are found to have greater family affection. It is perceived through these results that high religiosity among parents and the value of motherhood as taught in the Church have great influence on family affection.

Many studies have shown that there is an inverse relationship between family size and such variables as family affection, emotional adjustment of children, intelligence, and achievement. But it is not clear whether these relationships would still exist in a different subculture with different values. It is possible that the relationship between family size and the above variables is either completely spurious or is weak enough that its influence could be overcome by other variables. For this reason, Nye, Carlson, and Garrett (1970) recommended that family size research be conducted in populations with social contexts whose values are significantly different from those of mainstream urban America. The Mormon subculture fits this requirement. It is unique in several ways. Although the Mormons’ stand on birth control is not as strict as the Catholics’, they do strongly encourage large families. Family life is highly valued, as evidenced by one of their oft-repeated slogans, “No success can compensate for failure in the home.” Every Mormon is supposed to reserve Monday night for family home evening during which family communication and problem-solving are taught.

The purpose of this study is to examine the relationship between family size and family affection in a Mormon sample. Because of the values and programs of the Mormon Church, it is hypothesized that there is not an inverse relationship between family size and family affection among Mormons when social class, age, and length of marriage are controlled for.

In addition to the main hypothesis, partial correlation and path analysis will be used in an effort to ascertain the strength of various relationships. In particular, an effort will be made to determine the relative contributions of religious values and family interaction to family affection.

Review of Literature

Nye et al. (1970) cited several studies supporting the proposition that larger families are less likely to be characterized by positive affect than are smaller families (Bossard & Boll, 1956; Burgess & Cottrell, 1939; Christensen & Philbrick, 1952; Hawkes, Burchinal, & Gardner, 1958; Landis, 1954; Nye, 1951, 1958; Rainwater, 1960; Reed, 1947; Willie & Weinandy, 1963). In analyzing data from two large surveys, Nye et al. came to the following conclusions concerning the relationship between family size and family affection: adolescents from larger families are more likely to feel neglected or rejected by their parents; and family size does not significantly affect the respect or affection that adolescents feel toward their parents, nor does it influence the spousal affection of the parents involved.

Several studies investigated the relationship between the children’s social-emotional adjustment and the number of siblings they have. In analyzing the records of 1,581 children referred to outpatient psychiatric clinics, Tuckman and Regan (1967) found that as family size increased, school problems and antisocial behavior also increased. Conversely, they discovered a negative relationship between family size and manifestations of anxiety and neurotic behavior. Researchers studying male university students found evidence that individuals from small families have a slight advantage in personality adjustment over those from larger families (Stagner & Katzoff, 1936). Hawkes et al. (1958) could find no significant differences in personality adjustment of fifth-grade children from large and small families. In three different studies with adult subjects, no relationship was found between family size and either self-derogation (Kaplan, 1970) or homosexuality (Siegelman, 1973), but there was an over representation of persons from large families among alcoholics (Smart, 1963).

Strauss and Libby (1965) reviewed twenty-seven empirical studies dating from 1898 concerned with how the number of siblings affects a child’s personality. Inferences about personality were based on such indices as personality and adjustment inventories, interviews, teacher ratings, school records, frequency of behavior difficulties, etc. They tabulated the results of the twenty-seven studies as follows: twelve investigations concluded that small families promote superior personality development of children; nine studies revealed no relationship between sibling group size and children’s personality; and five studies showed evidence that large families produce children with superior personality characteristics.

A number of investigators have sought to determine how children are affected in other ways by the size of their family. In an extensive review of research, Lieberman (1970) compiled data concerning the effects of family size on children. He reported that children from small families generally have higher levels of intelligence, creativity, independence, and energy, and they are healthier physically and mentally. Nye et al. (1970) found that in large families parents are more restrictive with their daughters and less restrictive with their sons than is the case in medium or small families. They also concluded that parental use of corporal punishment becomes more common as family size increases. Another study demonstrated that male adolescents from small families accept parental authority more fully than do youth from large families (Smith, 1971). Strauss and Libby’s (1965) review asserts that a wide body of research studies shows an inverse correlation averaging approximately -.30 between sibling group size and child’s intelligence. Two different teams of researchers investigating the relationship between family size and academic achievement came to the same conclusion: among lower-class families, large family size impedes academic achievement, but among middle-class families, the relationship disappears (Poole & Kuhn, 1973; Strauss & Libby, 1965). In controlling for socioeconomic class, Kunz and Peterson’s (1972) paper summarizing the results of two large-scale, carefully designed investigations (one with high school students, the second with university students), showed no statistically significant relationship between these two variables.

A number of criticisms have been leveled at research concerned with the influence of family size. Kunz and Peterson (1972) made a careful analysis of Lieberman’s review (1970), pointing out several instances in which the latter had misrepresented the findings of the original researchers. Subsequent to their earlier review of twenty-seven empirical studies, Strauss and Libby (1965) concluded that research design in the area of family size has been inadequate. One of the principal defects they pointed to in many of these studies was the failure to control for the variable of socioeconomic status. Some of the problems associated with research of this type are discussed by Thomas (1972). He also cites evidence that when families within a given socioeconomic class are compared, children with no siblings, few siblings, and many siblings appear to differ little, if any, with respect to most characteristics investigated (Clausen, 1966, p. 14; see also Kunz & Peterson). On the basis of a carefully designed cross-cultural research investigation involving adolescents living in New York City; San Juan, Puerto Rico; and Merida, Yucatan; Thomas concluded that the effects of family size are negligible if parents possess the resources to provide their children with material and emotional support. In interpreting the data from his study, he states that the quality of emotional support evidenced in parent-child interaction is much more crucial in influencing children’s characteristics than is the number of children in the family.

In attempting to explain why large families in the middle class appear not to be beset with the problems experienced by large families of the working class, Strauss and Libby (1965) suggested that middle-class parents’ value-commitment to large families motivates them to invest the extra time and energy in the child care necessary to achieve positive results with their several children. Nye et al. (1970) recommended that family size research be conducted in populations with social contexts whose values are significantly different from those of mainstream urban America to determine whether the affective relationships are superior in small families. Hurley and Palonen (1967) suggest that one of the more significant social context variables is affiliation with a religion which is supportive of large families. Kunz and Peterson’s (1972) investigation among a subculture with strong positive sanctions for large families (Mormons) yielded no significant relationship between family size and academic achievement.

The review of literature seems to indicate that family size does not have a negative impact if large families are valued and the family has sufficient resources. Mormons do value large families, and the Church strives hard to supply both material and social-emotional resources. The church welfare system supplies food and clothing in time of need and helps the family find employment. It functions much like an extended family, with members cooking meals and cleaning houses when illness strikes. Principles of effective family living are taught in all meetings to all sexes and age groups. Based on the above, it seems logical to hypothesize that there will not be an inverse relationship between family size and family affection in a Mormon sample.

Procedure

A stratified random design was used to select 332 two-parent families with an adolescent from fifteen congregations of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormon) who were considered active members. A letter of explanation and a questionnaire were mailed to one adolescent subject from each family. Those subjects who did not return their questionnaire within several days were telephoned and their cooperation was requested. The final sample consisted of 223 adolescents, with approximately equal numbers of boys and girls of the same age from each of the three social classes.

The operational definition and instrument for measuring family affection was taken from Stevens (1955). She defined familial affection as follows: “Familial affection is defined as the degree of emotional attachments—empathy, loyalty, respect, sharing, and responsibility—which family members have for each other. A person who feels affection is one who (1) has empathy—feels with another person or group; (2) has loyalty—is supporting, faithful, and devoted; (3) has respect—-recognition of and appreciation for individuality; (4) is willing to share—seeks optimum participation in activities and experience; and (5) feels responsibility—is deeply concerned for the happiness, protection, development, and general well-being of the loved one” (p. 6).

The questionnaire was broken down into four subareas: father- child, mother-child, father-mother, and mother-father. In each sub-area there were twenty questions making a total of eighty items on the questionnaire. Out of the twenty questions, there were four on each of the five basic elements of affection: two odd and two even, randomly distributed.

Participation in family-related activities was measured by an eleven-item instrument developed by the investigators. Both instruments utilized summative scaling methods. The validity of both instruments was established by having panels of judges rate the item. Reliability for both of these instruments was established by analyzing the test-retest data obtained in a pilot study of thirty-nine subjects. The Family Affection Instrument had a correlation coefficient of .92, while the Family Activities Instrument had a correlation of .75.

Most studies of family size have only measured the number of children in the family. However, for older families, some of the children might have already moved away. Thus, the number of children actually living at home might be a more sensitive indicator of family dynamics than the total number in the family. For purposes of comparison, both measures of family size are used in this study.

Data Analysis and Findings

Pearson Correlation, Spearman’s Rank, and Kendall’s Tau were calculated between the independent variables of the number of children in the family, and the number of children living at home, and the dependent variables measuring family activity and affection. There was little difference between the three measures of correlation; consequently, Pearson Correlation was used for the remainder of the analysis because of the greater ease in doing further calculations from this measure. The correlations were generally low as would be expected from using a rough measure of family structure such as family size. However, many were statistically significant and generally were in the opposite direction of those found in previous studies. They supported the hypothesis that there would not be a negative relationship between family size and family affection in the Mormon sample.

The number of children living at home proved to be a more sensitive indicator than the total number in the family. The total number in the family was significantly related to three variables: total family activity, the participation of father and son together, and the participation of the mother and daughter together. The number of children at home was significantly related to the affection of the mother to the child, the affection of the mother to the father, total family activity, the total family affectional relationship, and the participation of the father and son together. In most cases, the correlations were higher for the number of children living at home than for the total number of children in the family (Table 6.1). Consequently, the number of children living at home was used alone in later analysis.

Table 6.1: Correlations between Family Size and Measures of Family Affection and Activity

| Number of Children in Family | Number of Children at Home | ||

Total family activity | .19*** | .18** | |

Affection between mother and child | .08 | .12* | |

Affection of the mother to the father | .02 | .16** | |

Total family affectional relationships | .01 | .11* | |

Participation of the father and son together | .19* | .23* | |

Participation of the mother and daughter together | .16* | .11 | |

** | Significant at the .05 level. | ||

** | Significant at the .01 level. | ||

*** | Significant at the .005 level. | ||

Further analysis showed that the correlation between the activity of the married couple together and the number of children at home was .13, which was significant at the .05 level. But the correlation between the amount of parental activity with children individually and the number of children at home was -.18, which was significant at the .005 level.

The next step in the data analysis was to use partial correlation to control for variables to test for spuriousness in the relationship. The Mormons are unusual in that there exists a positive relationship between social class and family size in this sample. However, controlling for social class makes little difference in the strength of the relationships between family size and family activity and affection. Age and length of marriage were also controlled for and were found to have little effect.

Although the sample is Mormon, there are wide differences in religious activity and devotion in the sample. Religiosity could be a key variable in explaining the relationship between family activities, affection, and family size. One measure of commitment in the Mormon Church is being active in the temple. In order to qualify for a temple recommend, the couple must be strictly living all of the commandments of the church. Controlling for temple attendance does make an important difference. The relationships between the number of children at home and total family activity, total family affectional relationships, and participation of the mother and daughter together drop below the significance level. The relationship between the number of children at home and participation of the mother and daughter together even changes sign.

Total family affectional relationships is a variable consisting of four subscales: the affection of father to child, the affection of mother to child, the affection of mother to father, and the affection of father to mother. Each of these four subscales consists of twenty questions making a total of eighty questions in all. The possibility exists in a scale of this size that it is not unidimensional but could be broken down into several factors. A factor analysis was run to check this out. Principal factoring with iteration and varimax rotation with the eigenvalue set at 1.0 was used. Two factors emerged, but the first factor accounted for 95 percent of the variance. Further analysis using the two factors showed no significant differences from using the single composite variable.

Even though factor analysis made no difference, further insight was gained by looking at the subscales of the total family affectional relations. All of the correlations between the subscales and the number of children at home are positive, but they are not of the same magnitude. The affection of mother to child and of mother to father are significant, but the affection of father to child and of father to mother are not. So the relationship between the mother’s affection and family size is stronger than the relationship between the father’s affection and family size.

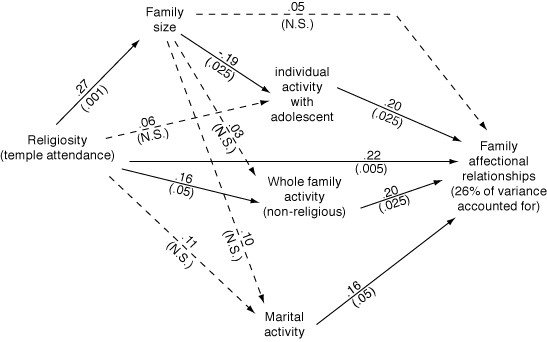

At this point the data shows that in a Mormon sample the number of children at home is positively related to family activities of various types and to the total family affectional relationships. These relationships were very much affected by controlling for the religiosity of the couple, indicating that religiosity might be the key causal variable. But the strength of the relationship between family size, religiosity, family activities, and family affection is not clear. Path analysis can be used to help determine the direct and indirect effects of the variables on each other. But in order to use path analysis some assumptions of weak causal ordering must be made (Nie, Hull, Jenkins, Steinberger, & Bert, 1975). The first assumption is that religiosity is the variable that is first in the causal sequence (see Figure 6.2). Religious commitment typically comes early for Mormons; e.g., in early adolescence. Therefore, it is logically prior to marriage and family. The second assumption is that Mormons have more family activity because they are following the teachings of their church. The third assumption is that having children at home precedes the various measures of family activity. Fourth, it is assumed that family activities temporally precede and influence family affectional relations. Last, it is assumed that the covariation between the various types of family activities—individual, couple, and whole family—is not causal. This correlation results totally from causal relations with other variables. It is very difficult to find a rationale for putting these variables in a temporal sequence, and hence, it is assumed that they occur simultaneously.

Figure 6.1: Path Analytic Model of Religiosity, Family Size, Family Activities, and Family Affection Showing Standardized Coefficients

Figure 6.1: Path Analytic Model of Religiosity, Family Size, Family Activities, and Family Affection Showing Standardized Coefficients

Based on these assumptions, the path coefficients were computed and are shown in Figure 6.1. In order to separate the effects of religiosity and activity, a measure of religiosity was used that was not a family activity. Temple attendance is an activity only for adults. The relationship between temple attendance and the number of children at home is highly significant (.001), but temple attendance is only weakly related to the various measures of family activities. The only relationship which is statistically significant is with whole family activities, and that is at the .05 level. Perhaps the most striking finding is that temple attendance has a direct effect on family affectional relationships. It would seem logical that religious Mormons would have higher family affectional relationships because they do more things as a family. But the path analysis shows religiosity has an effect independent of the family activities that were measured. The path analysis also shows that the number of children at home has no significant direct effect on family affection. The indirect effect through “individual activities” is also very small and nonsignificant. (It is obtained by multiplying the two path coefficients together and is less than .04).

Summary and Conclusions

Many studies have shown an inverse relationship between family size and family affection. It was hypothesized that this would not be true in a Mormon sample because of the value they place on large families and their stress on family activities. The hypothesis was supported, and there was a small but statistically significant relationship between family size, family activities, and family affection in the sample. The large Mormon families tended to spend more time in family activities but less time individually with each child. The number of children living at home proved to be a more sensitive indicator than the total number of children in the family. Controlling for social class, age, and length of marriage had little effect on the relationships.

Controlling for religiosity greatly reduced the relationships between the variables. This indicates that religiosity is probably the key causal variable. Since devout Mormons are encouraged to have large families, it is probable that religiosity is causally related to family size. Religiosity is also related to family activities, and it seems logical that family activities would be a key intervening variable between religiosity and family affection. But path analysis did not support this interpretation. It was not family activities that made the most difference but a measure of religious commitment, temple attendance. Religiosity has a direct effect on family affection independent of family activities. Family size has no significant effect, direct or indirect, on family affection in the path analysis. Analysis of the dependent variable, total family affectional relationships, shows that it is the mother who is perceived as changing the most as family size varies. She is perceived as being more affectionate, understanding, and accepting in large families.

Given the above information, the following interpretation seems plausible. The more active Mormons are exposed to a philosophy which greatly encourages large families and stresses the importance and value of becoming a good parent. The Mormon mother especially finds herself continually exposed to a philosophy which stresses the eternal importance of motherhood and the family. She is constantly being taught that her work is very important and fulfilling. The eternal nature of the family is heavily stressed in the temple. The Mormon Church is also a very close-knit social group. Therefore, in addition to being exposed to a philosophy that values motherhood, the Mormon mother is surrounded by friends with the same values. All of this would tend to make her feel that her work as a mother is important and fulfilling and that she is also an important person. This attitude could be communicated to the children through her interactions with them. Even when she does not actually interact more with her children, she probably has a better attitude and is perceived by them as being more affectionate, understanding, and accepting.

Another possible interpretation is that there is really no difference between the more and less religious Mormon families; the apparent differences are a result of the biased perceptions and expectations of the adolescent. The adolescents have been taught that active Mormon families are better, so they report this and fulfill the expectation. If this were the case, then all “good” aspects of the family should be fairly uniformly correlated since they are all caused by the adolescent’s perception. All of the good aspects are not uniformly correlated, which would argue against the perceptual bias interpretation.

This study has important implications. First, it shows that the negative relationship between family size and affection is not so strong that it cannot be neutralized or even reversed. Second, it suggests that the key to reversing this relationship lies in the attitudinal dimension, particularly in the mother’s attitude. If the authors’ interpretation is correct, then it is very important that mothers of large families be helped to feel that their work is very important, creative, and fulfilling. This positive attitude will help them to be more affectionate, understanding, and accepting of their children.

References

Bossard, J. S., & Boll, E. (1956). The large family system. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Burgess, E. W., & Cottrell, L. S. (1939). Predicting success or failure in marriage. New York: Prentice-Hall.

Christensen, H. T., & Philbrick, R. E. (1952). Family size as a factor in the marital adjustments of college couples. American Sociological Review, 17 (3), 306–312.

Clausen, J. A. (1966). Family structure, socialization and personality. In L. W. Hoffman & M. L. Hoffman (Eds.), Review of child development research (Vol. 2, pp. 4–12). New York: The Russell Sage Foundation.

Hawkes, G R., Burchinal, L., & Gardner, B. (1958). Size of family and adjustment of children. Marriage and Family Living, 20 (1), 65–68.

Hurley, J. R., & Palonen, D. (1967). Marital satisfaction and child density among university student parents. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 29 (3), 483^184.

Kaplan, H. B. (1970). Self-derogation and childhood family structure. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 151 (1), 13–23.

Kunz, P. R., & Peterson, E. T. (1972). Family size and academic achievement. In H. M. Bahr, B. A. Chadwick, & D. L. Thomas (Eds.), Population, resources and the future (pp. 159–174). Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press.

Landis, P. H. (1954). Teenage adjustment in large and small families (Bulletin No. 549). Pullman, WA: Washington State University Agricultural Experiment Station.

Lieberman, E. J. (1970). Reserving a womb: Case for the small family. American Journal of Public Health, 60(1), 87–92.

Nie, N., Hull, C. H., Jenkins, J. G, Steinberger, K., & Bert, D. H. (1975). Statistical package for the social sciences. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Nye, F. I. (1951). Parent-child adjustment: Socio-economic level as a variable. American Sociological Review, 16, 341–349.

Nye, F. I. (1958). Family relationships and delinquent behavior. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Nye, F. I., Carlson, J., & Garrett, G. (1970). Family size, interaction, affect and stress. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 32 (3), 216–226.

Poole, A., & Kuhn, A. (1973). Family size and ordinal position: Correlates of academic success. Journal of Biosocial Science, 5, 51–59.

Rainwater, L. (1960). And the poor get children. Chicago: Quadrangle Books.

Reed, R. B. (1947). Social and psychological factors affecting fertility: The interrelationship of marital adjustment, fertility control, and the size of the family. The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly, 25 (2), 383–425.

Siegelman, M. (1973). Birth order and family size of homosexual men and women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 41 (1), 164.

Smart, R. (1963). Alcoholism, birth order and family size. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, (56(1), 17–23.

Smith, T. E. (1971). Birth order, sibship size and social class as antecedents of adolescents’ acceptance of parents’ authority. Social Forces, 50 (2), 223–232.

Stagner, R., & Katzoff, E. T. (1936). Personality as related to birth order and family size. Journal of Applied Psychology, 20, 340–346.

Stevens, B. L. (1955). Personal adjustment ofpre-adolescents and their perception of familial affectional relationships. Unpublished master’s thesis, Iowa State College.

Strauss, M. A., & Libby, D. J. (1965). Sibling group size and adolescent personality. Population Review, 9 (1), 55–58.

Thomas, D. L. (1972). Family size and children’s characteristics. In H. M. Bahr, B. A. Chadwick, & D. L. Thomas (Eds.), Population, resources and the future (pp. 137–158). Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press.

Tuckman, J., & Regan, R. (1967). Size of family and behavioral problems in children. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 111 (2), 151—160.

Willie, C. V., & Weinandy, J. (1963). The structure and composition of “problem” and “stable” families in a low-income population. Marriage and Family Living, 25 (4), 439–447.