Family, Religion, and Delinquency among LDS Youth

Brent L. Top, Bruce A. Chadwick, and Janice Garrett

Brent L. Top, Bruce A. Chadwick, and Janice Garrett, “Religion and Family Formation,” in Religion, Mental Health, and the Latter-day Saints, ed. Daniel K. Judd (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1999), 129–168.

Brent L. Top was professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University, Bruce A. Chadwick was professor of sociology at Brigham Young University, and Janice Garrett was a research analyst at the LDS Church Office Building when this was published.

Abstract

This study examines the relationship between religion and delinquency among Latter-day Saint youth residing on the East Coast, in the Pacific Northwest, and in central Utah. The differing geographical locations were selected in order to investigate whether the dominant Latter-day Saint culture in Utah reduced acts of delinquency among LDS youth. The results of this study indicate that neither geography nor concentration of LDS youth were directly related to delinquency. This report suggests that lower rates of delinquency are associated with the “spiritual environment” of the home rather than with geographical location. The authors of this study conclude that youth who most successfully resist peer pressure to engage in delinquent behavior come from homes where parents teach and live religious principles. Specifically, the internalization of religion, private religious devotion, the importance of the youth’s relationship with God, and experiences with the Spirit were the most significant factors in predicting delinquency.

Is it better to raise your children in Utah in an overwhelmingly LDS environment, or is it better for them to face the challenges of being a minority in the “mission field?” Does the dominant LDS culture in Utah reduce negative peer pressure on youth, thus reducing delinquency? Do the challenges to LDS beliefs and practices that youth in the “mission field” cope with actually make them stronger and more resistant to temptation than Utah youth who have faced little of such opposition? Wherever LDS families reside, parents ask themselves what they can do to help their teenagers become happy and competent young adults. Are strict rules better than a warm parent-child relationship in helping adolescents deal with school and dating? Should parents force their teens to attend church and participate in young men or young women activities? How do parents help their children develop a testimony? These are merely a few of the questions raised by concerned LDS parents. With the avalanche of temptations threatening today’s youth, parents are seeking for any guidance they can find in helping their children maneuver around the many potholes of life’s highway.

Parents can take some comfort from the significantly lower levels of delinquency among LDS teens as compared to their peers across the nation. For example, over 85 percent of high school seniors nationwide have drunk alcoholic beverages compared with only a fourth of LDS seniors (Johnston, Bachman, & O’Malley, 1993). Over three-fourths of male high school seniors reported having had premarital sex as compared to 10 percent of male LDS seniors. The difference between non-LDS and LDS young women is almost as large. Also, LDS high school seniors had the highest rate of abstinence from drugs among youth affiliated with various religious denominations and youth with no religious identification. Overall, LDS youth report lower levels of participation in virtually all types of delinquent activities ranging from cheating on school tests to being involved in gang fights.

Religiosity and Delinquency

A reasonable explanation for this lower delinquency is that LDS youth internalize a set of values and practices that are inconsistent with such behavior. Believing in God, accepting Jesus Christ as one’s Savior, making efforts to live the Ten Commandments, following the Golden Rule, and striving to live a Christ-like life all foster honesty, integrity, and cleanliness in thought and action. These qualities are in turn inconsistent with cheating on school examinations, shoplifting, hurting others in fights, participating in premarital sexual activities, using drugs, and other types of delinquency. Latter-day Saint youth who have internalized these religious values and practices should exhibit significantly less delinquency than those with lower religiosity.

On the other hand, some social scientists have contended that lower delinquency among religious youth, including Latter-day Saints, is more attributable to their religious environment—the high concentration of religious members in their community—than to any set of internalized religious values or practices (Stark, 1984; Stark, Kent, & Doyle, 1982). Religious ecology is generally ascertained by the proportion of the population affiliated with a religious denomination, the average frequency of church attendance, the number of church books sold or checked out of libraries per 100,000 people, the ratio of religious buildings to the population, the ratio of clergy to the population, and similar ratios and proportions. The argument is that in a highly religious ecology, the youth are surrounded by others—both adults and peers—whose social pressures ensure conformity to societal norms.

To test this religious ecology theory, the authors studied Latter-day Saint teenagers living in a low LDS religious ecology on the East Coast of the United States (Chadwick & Top, 1993). As expected, the multivariate analysis revealed that peer pressure was the strongest predictor of delinquency among the Latter-day Saint youth. Additionally, several dimensions of religiosity also made significant independent contributions to explaining delinquency. Private religious behavior—such as personal prayer, scripture reading, and personal spiritual experiences—is the most powerful deterrent of delinquency. At the same time, however, mere attendance at church meetings (public religious behavior) was not significantly related to lower delinquency. Thus, the private internalization of the gospel made a significant contribution to understanding delinquency independent of peer pressures.

A few readers of the initial study suggested testing the religious ecology hypothesis in different religious environments across the country. Some suggested that the Pacific Northwest—the area with the lowest religious ecology in the United States—would provide a strong test of the religious ecology hypothesis (Stark et al, 1982). Therefore, we collected information from a sample of Latter-day Saint high school students living in Seattle, Washington and Portland, Oregon.

To more adequately test the religious ecology theory, information from LDS youth living in a very high religious ecology was obtained as well. Data were collected from a sample of LDS high school students in Utah County, Utah, which has the highest religious ecology in the entire country. This exceptionally high religious ecology is uniquely LDS, as over 95 percent of the population is LDS and virtually all of the youths’ friends are members of the LDS Church. These three samples allowed us to compare the relationship between religiosity and delinquency in three different religious ecologies: the Pacific Northwest with a low religious ecology, the East Coast with a moderate ecology, and Central Utah with a very high ecology.

Family Characteristics and Delinquency

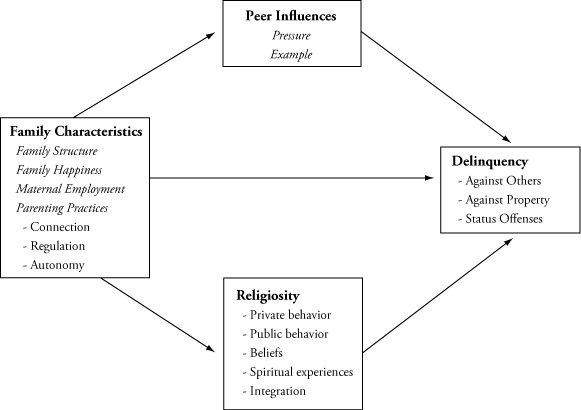

In addition to testing the influence of peers and religiosity on delinquency among LDS youth in the different religious ecologies, we extended our analysis to include the influence of family characteristics. The doctrine of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints strongly emphasizes the importance of the family. Members are encouraged to marry, to have children, to have mothers remain in the home, to provide a nurturing environment for their children, and to avoid family conflict and divorce. Family structure, maternal employment, family happiness, and parent-child relations were added to the delinquency model (see Figure 8.1). Family structure indicates whether the youth live in a single- or two-parent family. Maternal employment indicates whether the youth’s mother is a stay-at-home mother, works part time, or is employed full time outside the home. Family happiness indicates the youth’s perception of the degree of happiness in their parents’ marriage.

Figure 8.1: Model with Peer Influences, Religiosity, and Family Characteristics Predicting Delinquency

Figure 8.1: Model with Peer Influences, Religiosity, and Family Characteristics Predicting Delinquency

Three aspects of the relationship between parents and their teens were included. Family connectedness is the teenagers’ feelings that their mother and father love them and are genuinely interested in them. Family regulation is the degree to which parents monitor their teenage children’s activities, such as knowing who their friends are and where they go when they are not at home. Family autonomy refers to parents encouraging the development of individual identity and fostering feelings of self-worth in their children. Parents who use excessive guilt induction or love withdrawal to control their children deny them the autonomy, or agency, to make their own decisions and to develop the independence required to function as a responsible adult. Family autonomy, however, does not mean a low level of parental regulation. Parents can have strict family rules with stiff penalties for noncompliance and still allow their children autonomy to develop their own sense of self.

As shown in Figure 8.1, we anticipated the family’s influence on delinquency to be both direct and indirect through peers and religiosity. We expected that strong LDS families would not only assist their teenage children to avoid delinquent activities but would also assist them in selecting nondelinquent friends, in withstanding pressures from friends, and in fostering internalization of religious values.

The first objective of this study was to assess the relationship between religiosity and delinquency among LDS youth living in three dissimilar religious ecologies. We hypothesized that LDS young people have internalized religious values, which is associated with lower frequency of delinquency. The second objective was to test a multivariate model of delinquency that includes peer pressure, religiosity, and family characteristics. It was predicted that although peer influences are the most significant predictors of delinquency, the various dimensions of religiosity and family characteristics would make independent contributions to understanding delinquency.

Methodology

Data Collection

There were three separate data collection efforts. In 1992, we selected a sample of 1,882 LDS youth enrolled in either early morning or weekly home study LDS seminary classes. These ninth through twelfth graders resided in Delaware, New York, Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, and Washington, D.C. This area has an average general religious ecology and a low LDS religious ecology. Specific methodological details are available in Chadwick and Top (1993).

The second phase obtained similar data from a sample of LDS high school students living in the Pacific Northwest. In 1994, a sample of 958 LDS seminary students in the Seattle and Portland areas were selected. The size of the Pacific Northwest sample is smaller than the other samples because Church leaders were concerned about intrusion into the lives of members in this area. Thus, we were granted permission to draw a smaller sample.

The final phase was completed in early 1996. We surveyed 1,700 LDS high school students living in Utah County, Utah, which has a very high LDS religious ecology.

Samples from the East Coast, Pacific Northwest, and Central Utah provide a wide range of religious ecologies as well as a fairly broad cross section of LDS youth. While a few LDS youth may be missing from seminary enrollment lists in a given area, most are included. Strong recruiting enrolls around 95 percent of LDS teenagers in seminary classes. A bias toward obtaining only active LDS youth is limited as some of the most religious LDS youth are not enrolled, while seminary may be the only Church contact for others.

A packet was sent to the youths’ parents with a letter explaining the study and asking permission for their son or daughter to participate. Parents were informed that the questionnaire asked about sensitive topics including premarital sexual activity, drug use, and delinquent activities. If parents did not want their teenager to participate in the study, they were instructed to return the business reply envelope included in the packet. Of the several thousand families approached, less than ten refusals were mailed to us. The letter stressed that in order to collect accurate information, parents needed to allow their teen to respond in complete privacy. A letter to the youth and a business reply envelope was enclosed so the youth could confidentially return the completed questionnaire.

A postcard reminder was mailed approximately three weeks after the first mailing. One month later, a new packet—including all of the original materials—was sent to those who had not returned the questionnaire.

These procedures resulted in 1,393 (74 percent) completed questionnaires from the East Coast sample, 632 questionnaires (66 percent) from the Pacific Northwest sample and 1,078 questionnaires (62 percent) from the Central Utah sample. The overall response rate was 61 percent, which is reasonable for a mail survey of teenagers dealing with sensitive issues and requiring parental consent.

Measurement of Variables

Forty items measured three separate dimensions of delinquency—offenses against others, offenses against property, and victimless or status offenses. Offenses against others ranged from picking on other kids to participating in gang fights. Property offenses involved stealing and vandalism. Status offenses focused on drug and alcohol use as well as premarital sex. The youth were asked if they had ever engaged in any of the specific delinquent activities and if so, how often. For this study we combined the three dimensions of delinquency into a single global measure.

Two measures of peer influence were included in the model. Peer pressure was measured by items asking how much their friends pressured them to engage in the forty delinquent activities. The response categories were “yes” or “no.” “Yes” replies were summed as a measure of peer pressure. Peer example was determined by asking how many of their friends participated in the list of delinquent behaviors. The response categories were “none,” “some,” “most,” or “all.” We also asked the youth how many of their friends, or the kids they hang around with, are LDS.

Religiosity included five dimensions. Private religious behavior was measured by questions about the frequency of personal prayer, private scripture reading, fasting, and making financial contributions. Six items asking the frequency of attendance at various church meetings assessed public religious behavior. Religious beliefs were ascertained by twelve items about the acceptance of traditional Christian beliefs as well as unique LDS doctrines. Spiritual experiences were measured by eleven items asking how often their prayers had been answered, if they had felt the Holy Ghost in their lives, or if they had had other similar experiences. Three items asking how well the youth felt they fit into their wards or branches and how well they felt they were accepted by fellow Church members determined feelings of religious integration. The response categories for these items ranged from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” In the initial test of the delinquency model, we combined all six dimensions into a global measure of religiosity.

In addition to the youth’s personal religiosity, family religiosity was also measured. The youth were asked questions regarding the frequency of family religious activities such as family prayer, family scripture study, and family home evening. Responses included “very often,” “often,” “not very often,” and “not at all.”

Family structure was assessed by asking if the student lived with both parents, with mother only, with father only, with a natural parent and a step-parent, or with other relatives such as grandparents. A question asked whether their mother was employed outside the home and if so, whether she worked part or full time to measure maternal employment. Family happiness was determined by a single item asking the student’s perception of the happiness of their parents’ marriage.

Ten questions originally developed by Schaefer (1965) and recently tested by Barber, Olsen, & Shagle (1994) ascertained the level of family connectedness between teens and their parents; an example is “My mother is a person who makes me feel better after talking over my worries with her.” Family regulation was gauged by five items asking how closely the teenagers feel their parents monitor their behavior (Dornbusch, Ritter, Liederman, Roberts, & Fraleigh, 1987; Steinberg, Fletcher, & Darling, 1994). The five regulations questions asked if their parents really know who their friends are, where they go at night, where they spend their time after school, how they spend their money, and how they spend their free time. Family autonomy was also measured by ten questions developed by Schaefer (1965) and recently used by Barber et al. (1994). The items assessed the degree of independence the youth feel their parents allow them and the means parents use to control their behavior. An example is “My mother is a person who will avoid looking at me when I have disappointed her.” The family connectedness, regulation, and autonomy items asked about the youth’s mother and were then repeated for their father. The response categories were “not like her/

Analysis

First, the delinquency, peer influence, religiosity, and family characteristics of the youth living in the three different religious ecologies were compared. Where appropriate, a difference of means or an analysis of variance was computed to determine if observed differences were statistically significant.

Next, the delinquency model with measures of peer influence, religiosity, and family characteristics was tested using LISREL structural equation analysis. LISREL first computes a measurement model that confirms that the observed variables (questions asked) are appropriate indicators of the latent variables (delinquency, peer influences, religiosity, and family characteristics). Second, a structural model is calculated, which identifies “causal” relationships between the independent variables (peer pressures, religiosity, and family characteristics) and the dependent variable (delinquency). Importantly, LISREL analysis identifies both the direct and indirect effects of the independent variables on the dependent one.

Findings

Delinquency

The percentages of the LDS youth in each of the three religious ecologies who have participated in the forty-one specific delinquent activities are presented in Table 8.1. The average number of times the delinquent youth have committed a specific action is reported in Table 8.2. Most studies of delinquency ask how many times a youth has committed an offense in the past year, month, or week. Given the significantly lower rates of delinquency among LDS youth, we were forced to ask how often they had ever engaged in the behavior in question in order to have sufficient variance in delinquency to study. We asked how often the youth had committed a delinquent act to distinguish between a brief experimentation as opposed to an ongoing pattern of delinquency.

As can be seen in Table 8.1, 20 percent of the LDS high school students reported having cursed or sworn at parents. Table 8.2 indicates this 20 percent have cursed at their parents about eight times on average. About a third of the youth admitted to having shoplifted at least once in their lives. This third of the teenagers had done so six or seven times. Over 70 percent of the young people have cheated on an examination in school. Not surprisingly, more young men than young women have engaged in violent delinquent actions such as physically beating up other kids and participating in gang fights.

Table 8.1: Percent of LDS Youth Who Have Committed Offenses against Others, Property, and Victimless Offenses, by Sex and Region

| Males | Females | ||||||

| East Coast (N=636) | West Coast (N=251) | Utah Valley (N=460) | East Coast (N=754) | West Coast (N=363) | Utah Valley (N=598) | ||

| Offenses against Others | |||||||

| Cursed or swore at parent | 19% | 19% | 20% | 21% | 20% | 20% | |

| Pushed, shoved, or hit parent | 10 | 12 | 8 | 14 | 10 | 8 | |

| Openly defied church teacher/ | 20 | 12 | 15a | 18 | 10 | 11 | |

| Openly defied school teacher/ | 36a | 34a | 54a | 26 | 22 | 46 | |

| Created a disturbance in public space | 48 | 39 | 40a | 43 | 34 | 32 | |

| Been suspended or expelled from school | 20a | 19a | 13a | 6 | 7 | 5 | |

| Forced or pressured sexual activities | 5 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 4 | |

| Threw things at cars, people, or buildings | 41a | 40a | 38a | 18 | 15 | 16 | |

| Called on telephone to threaten/ | 21 | 32 | 26 | 23 | 27 | 26 | |

| Picked on kids/ | 52a | 52a | 39a | 43 | 34 | 30 | |

| Picked a fight with other kids | 25a | 26a | 22a | 12 | 11 | 9 | |

| Physically beat up other kids | 25a | 25a | 19a | 8 | 6 | 5 | |

| Took money by using force or threats | 2 | 6a | 4a | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Hurt someone badly enough to need doctor | 8a | 10a | 8a | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| Threatened or attacked with knife, gun, or other weapon | 6a | 6a | 5a | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Been in a gang fight | 8a | 7a | 6a | 2 | 3 | 2 | |

| Offenses against Property | |||||||

| Took something from a store without paying for it | 33a% | 39a% | 32a% | 20% | 22% | 18% | |

| Stole from a locker, desk, purse, etc. | 12 | 17 | 17a | 11 | 12 | 10 | |

| Stole anything more than $50 | 6a | 6 | 6a | 2 | 4 | 4 | |

| Stole anything worth between $5 and $50 | 18a | 22a | 19a | 10 | 12 | 10 | |

| Stole anything less than $5 | 37a | 40a | 32a | 22 | 21 | 19 | |

| Took car or motor vehicle without owner’s permission | 8 | 10 | 12 | 6 | 8 | 11 | |

| Broke into a building, car, house, etc. | 15a | 11a | 13a | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Went onto someone’s property without permission | 53a | 51a | 49a | 34 | 34 | 36 | |

| Purposely ruined/ | 26a | 29a | 28a | 12 | 11 | 13 | |

| Purposely damaged or destroyed things at school, store, etc. | 17a | 20a | 20a | 9 | 9 | 9 | |

| Victimless Offenses | |||||||

| Smoked cigarettes | 24% | 18% | 17% | 24% | 19% | 9% | |

| Used “smokeless” or chewing tobacco | 12a | 10a | 9a | 3 | 5 | 2 | |

| Drank alcoholic beverages (beer, wine, liquor) | 24 | 13a | 15 | 27 | 19 | 12 | |

| Used marijuana (“grass,” pot”) | 7 | 8 | 7a | 5 | 9 | 4 | |

| Used cocaine (“crack,” coke”) | 2 | 2a | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Used other drugs (heroin, LSD, etc.) | 3 | 4 | 5a | 3 | 3 | 2 | |

| Been drunk or high on drugs | 12 | 8 | 8 | 13 | 11 | 6 | |

| Run away from home | 12 | 10 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 11 | |

| Skipped school without a legitimate excuse | 44 | 41 | 50a | 41 | 48 | 44 | |

| Cheated on a test | 70 | 66a | 67 | 73 | 71 | 63 | |

| Read sexually explicit or pornographic books or magazines | 46a | 48a | 37a | 20 | 16 | 11 | |

| Watched sexually explicit/ | 42a | 46a | 39a | 27 | 21 | 16 | |

| Been involved in heavy petting | 29 | 23 | 18 | 32 | 29 | 18 | |

| Had sexual intercourse | 7a | 6 | 6 | 12 | 9 | 5 | |

| a Difference between boys and girls within a region is statistically significant at the .05 level | |||||||

Table 8.2: Average Number of Times LDS Youth Have Committed Offenses against Others, Property, and Victimless Offenses, by Sex, and Region

| Males | Females | ||||||

| East Coast (N=636) | West Coast (N=251) | Utah Valley (N=460) | East Coast (N=754) | West Coast (N=363) | Utah Valley (N=598) | ||

| Offenses against Others | |||||||

| Cursed or swore at parent | 10 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 3 | 5 | |

| Pushed, shoved, or hit parent | 6 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 | |

| Openly defied church teacher/ | 10 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 5 | |

| Openly defied school teacher/ | 11 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 3 | 4 | |

| Created a disturbance in public space | 14 | 11 | 6 | 12 | 6 | 5 | |

| Been suspended or expelled from school | 4 | 2a | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4 | |

| Forced or pressured sexual activities | 6 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| Threw things at cars, people, or buildings | 9 | 7a | 7a | 6 | 3 | 4 | |

| Called on telephone to threaten/ | 7 | 7 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 5 | |

| Picked on kids/ | 21a | 13a | 8a | 15 | 8 | 6 | |

| Picked a fight with other kids | 8 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 4 | |

| Physically beat up other kids | 7 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 3 | |

| Took money by using force or threats | 6 | 6a | 7 | 5 | 1 | 6 | |

| Hurt someone badly enough to need doctor | 5 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 6 | |

| Threatened or attacked with knife, gun, or other weapon | 6 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 9 | |

| Been in a gang fight | 6 | 2 | 6 | 7 | 3 | 8 | |

| Offenses against Property | |||||||

| Took something from a store without paying for it | 9 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 3 | |

| Stole from a locker, desk, purse, etc. | 8a | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| Stole anything more than $50 | 5a | 2 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | |

| Stole anything worth between $5 and $50 | 7 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 4 | |

| Stole anything less than $5 | 9 | 5 | 5a | 5 | 5 | 3 | |

| Took car or motor vehicle without owner’s permission | 5 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 | |

| Broke into a building, car, house, etc. | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 4 | |

| Went onto someone’s property without permission | 11a | 6a | 5a | 2 | 3 | 3 | |

| Purposely ruined/ | 9 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | |

| Purposely damaged or destroyed things at school, store, etc. | 11 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 4 | |

| Victimless Offenses | |||||||

| Smoked cigarettes | 2 | 8a | 6 | 2 | 22 | 7 | |

| Used “smokeless” or chewing tobacco | 1 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 7 | |

| Drank alcoholic beverages (beer, wine, liquor) | 2 | 7 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 4 | |

| Used marijuana (“grass,” pot”) | 2 | 7 | 10 | 2 | 7 | 10 | |

| Used cocaine (“crack,” coke”) | 1 | 6 | 14 | 1 | 1 | 9 | |

| Used other drugs (heroin, LSD, etc.) | 2 | 3 | 12 | 1 | 4 | 6 | |

| Been drunk or high on drugs | 2 | 12 | 8 | 1 | 10 | 7 | |

| Run away from home | 3 | 12 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 2 | |

| Skipped school without a legitimate excuse | 9 | 12 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 8 | |

| Cheated on a test | 13 | 7 | 5a | 10 | 6 | 4 | |

| Read sexually explicit or pornographic books or magazines | 8 | 5a | 6a | 6 | 2 | 3 | |

| Watched sexually explicit/ | 8 | 5a | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | |

| Been involved in heavy petting | 9 | 3 | 8 | 11 | 12 | 5 | |

| Had sexual intercourse | 11 | 1a | 11 | 11 | 27 | 6 | |

| a Difference between boys and girls within a region is statistically significant at the .05 level | |||||||

It is interesting to note that among the LDS youth living on the East Coast and in the Pacific Northwest, significantly more young women than young men are sexually experienced. This gender gap in sexual activity widens with age. Consequently, 22 percent of the senior girls have had sexual intercourse compared to only 10 percent of the senior boys. This is somewhat surprising since nationally boys initiate sexual activity at an earlier age than girls and are generally more sexually active. The Central Utah sample reflects this national trend, although the slightly higher rate reported by the young men is not statistically different from that of the young women.

Importantly, religious ecology seems to have little to do with the delinquency of LDS teenagers, as the activity reported by the youth in the three areas are very similar. A low rate of delinquency among LDS youth was observed in high, medium, and low religious ecologies.

Peer Influences

As expected, the LDS teens living in Central Utah experienced less peer pressure to engage in delinquent behavior (see Table 8.3). The difference in peer pressure was most pronounced concerning victimless or status offenses such as drinking, smoking, using drugs and engaging in sexual activity. These activities are closely linked to LDS religious values. The differences are not always large, but the overall effect is that young men and women living in Utah are pressured less by their friends to participate in a variety of delinquent activities.

Table 8.3: Percent of LDS Youth Whose Friends Have Pressured Them to Commit Offenses against Others, Against Property, and Victimless Offenses, by Sex and Region

| Percent of Friends Who Have Pressured | |||||||

| Males | Females | ||||||

| East Coast (N=636) | West Coast (N=251) | Utah Valley (N=460) | East Coast (N=754) | West Coast (N=363) | Utah Valley (N=598) | ||

| Offenses against Others (pressure to) | |||||||

| Curse or swear at parent | 16% | 16% | 12% | 20% | 17% | 13% | |

| Push, shove, or hit parent | 6 | 6 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 5 | |

| Threw things at cars, people, or buildings | 56a | 53a | 52a | 26 | 29 | 27 | |

| Make obscene phone calls | 32 | 47 | 36 | 36 | 42 | 30 | |

| Purposely pick on/ | 69a | 73a | 59a | 64 | 60 | 48 | |

| Physically beat up other kids | 40a | 46a | 34a | 16 | 12 | 10 | |

| Take money or other things by using force or threats | 11a | 14a | 8a | 3 | 5 | 4 | |

| Join in a gang fight | 16a | 8a | 9a | 4 | 4 | 3a | |

| Offenses against Property (pressure to) | |||||||

| Take something from a store without paying for it | 50% a | 47% | 36% | 31% | 26% | 21% | |

| Steal anything more than $20 | 16a | 22a | 15a | 6 | 10 | 7 | |

| Steal anything less than $20 | 50a | 49a | 38a | 27 | 27 | 20 | |

| Take a car or motor vehicle without owner’s permission | 10 | 13 | 17 | 10 | 10 | 18 | |

| Break into a building, car, house, etc. | 21a | 14a | 19a | 8 | 6 | 8 | |

| Purposely ruin or damage someone else’s property or possessions | 47a | 53a | 41a | 27 | 28 | 25 | |

| Victimless Offenses (pressure to) | |||||||

| Smoke cigarettes | 46% | 43% | 30% a | 40% | 36% | 22% | |

| Use “smokeless” or chewing tobacco | 29a | 36a | 18a | 7 | 16 | 6 | |

| Drink alcoholic beverages (beer, wine, liquor) | 49 | 40 | 27 | 53 | 41 | 42 | |

| Use marijuana (“grass,” pot”) | 19 | 23 | 17a | 66 | 25 | 12 | |

| Use cocaine (“crack,” coke”) | 10a | 10 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 5 | |

| Use other drugs (heroin, LSD, etc.) | 12 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 6 | |

| Run away from home | 13 | 11a | 13 | 17 | 17 | 16 | |

| Skip school without a legitimate excuse | 58 | 61a | 68 | 62 | 72 | 61 | |

| Cheat on a test | 76 | 72 | 67 | 77 | 75 | 68 | |

| Read sexually explicit or pornographic books or magazines | 64a | 60a | 44a | 34 | 26 | 15 | |

| Watch sexually explicit/ | 63a | 53a | 42a | 48 | 35 | 21 | |

| Be involved in heavy petting | 35a | 28a | 20 | 45 | 39 | 25 | |

| Have sexual intercourse | 24a | 16 | 11 | 29 | 21 | 12 | |

| a Difference between boys and girls within a region is statistically significant at the .05 level | |||||||

The reason for the differential in peer pressure seems to be the proportion of friends who are also members of the Church. Only 25 percent of the young people in the Pacific Northwest reported that “all” or “most” of their closest friends were LDS as compared to 95 percent of the youth in Central Utah. We didn’t ask this question in the East Coast survey, but we suspect the percentage is similar to the Pacific Northwest. High school students in Utah have more LDS friends than those living on the East Coast or in the Pacific Northwest, and as a consequence, they experience less pressure to participate in delinquent behaviors.

Religiosity

The youth in the three different religious ecologies reported almost identical levels of high religiosity. Table 8.4 shows the percentage of youth who accept fundamental religious beliefs of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, as well as the frequency of their public and private religious behavior. As shown, over 90 percent of the youth believe that God lives, that Jesus Christ is the Savior of the world, that the Book of Mormon is true, and that the Church is led by living prophets. The level of involvement in church activities is also very high. Over 80 percent of the young people attend their meetings each week and over half pay a full tithe. Evidently LDS youth have high religiosity regardless of the religious ecology in which their family lives. The LDS youth living on the East Coast or in the Pacific Northwest are just as religious as their peers living in Central Utah.

Table 8.4: Personal Religious Beliefs and Practices of LDS Youth, by Region

| East Coast (N=1393) | West Coast (N=632) | Utah Valley (N=1078) | |||||||||

| Agree | Mixed Feelings | Disagree | Agree | Mixed Feelings | Disagree | Agree | Mixed Feelings | Disagree | |||

| Religious Beliefs | |||||||||||

| God lives and is real | 96% | 4% | 0% | 96% | 3% | 0% | 95% | 4% | 1% | ||

| Jesus Christ is the divine son of God | 97 | 3 | 0 | 98 | 2 | 0 | 97 | 3 | 0 | ||

| God really does answer prayers | 88 | 11 | 1 | 90 | 9 | 1 | 89 | 9 | 1 | ||

| Joseph Smith saw God and Christ | 92 | 7 | 1 | 95 | 7 | 0 | 96 | 4 | 0 | ||

| The president of the Church is a prophet | 94 | 5 | 1 | 96 | 4 | 0 | 96 | 3 | 1 | ||

| Book of Mormon is true | 93 | 6 | 1 | 95 | 5 | 0 | 94 | 5 | 1 | ||

| Church is guided by revelation | 92 | 7 | 1 | 95 | 5 | 0 | 94 | 5 | 1 | ||

| I plan to marry in the temple | 88 | 9 | 3 | 90 | 8 | 2 | 92 | 7 | 1 | ||

| I plan to be active in the Church | 89 | 8 | 3 | 93 | 5 | 2 | 91 | 7 | 2 | ||

| Past year, I tried to live standards | 75 | 18 | 7 | 80 | 14 | 6 | 80 | 13 | 7 | ||

| I have a strong testimony of gospel | 75 | 20 | 5 | 77 | 17 | 6 | 79 | 17 | 4 | ||

| There have been times I felt the Holy Ghost | 81 | 14 | 5 | 85 | 11 | 4 | 86 | 10 | 4 | ||

| I have felt repentance and forgiveness | 67 | 25 | 8 | 63 | 26 | 11 | 70 | 22 | 8 | ||

| Relationship to God is important to me | 82 | 15 | 3 | 82 | 14 | 4 | 82 | 11 | 7 | ||

| Religious Practices | |||||||||||

| Attend Priesthood or Young Women | 83% | 14% | 3% | 81% | 16% | 3% | 74% | 17% | 7% | ||

| Attend Sacrament Meeting | 86 | 11 | 3 | 86 | 13 | 1 | 79 | 15 | 5 | ||

| Attend Sunday School | 84 | 12 | 4 | 81 | 16 | 3 | 69 | 21 | 9 | ||

| Fast once each month | 34 | 39 | 27 | 37 | 39 | 22 | 43 | 36 | 21 | ||

| Pay full tithing | 55 | 30 | 15 | 57 | 30 | 13 | 56 | 31 | 13 | ||

| Give testimony in meeting | 7 | 32 | 61 | 7 | 25 | 68 | 5 | 26 | 69 | ||

| Read scriptures | 26 | 4 | 30 | 37 | 40 | 23 | 36 | 42 | 22 | ||

| Pray | 41 | 44 | 15 | 51 | 34 | 15 | 59 | 29 | 12 | ||

| Attend social activities | 54 | 39 | 7 | 44 | 44 | 11 | 36 | 48 | 14 | ||

| a Difference between boys and girls within a region is statistically significant at the .05 level | |||||||||||

Family Characteristics

An amazing 85 percent of the youth in all three religious ecologies were living with both parents (see Table 8.5). Seven percent were living with one parent and a step parent, and another 7 percent were living with only one parent. Over half of the youth in the three samples perceive their parents’ marriages as “very happy,” and another 34 percent feel the marriages are “happy.” Only 3 percent have parents who are living in what they think are “unhappy” or “very unhappy” marriages. About a third of the mothers are homemakers, a third work part time, and the other third work full time outside the home.

Table 8.5: Family Characteristics and Family Religious Practices of LDS Youth by Region in Percentage

| Family Characteristics | East Coast (N=1393) | West Coast (N=632) | Utah Valley (N=1078) |

| Family structure | |||

| Live with both parents | 85 | 88 | 87 |

| Live with parent and stepparent | 8 | 7 | 7 |

| Live with one parent | 7 | 5 | 7 |

100 | 100 | 101 | |

| Parents married in temple or sealed | 86 | 93 | 93 |

| Perceived happiness of parents’ marriage: | |||

| Very happy | 50 | 52 | 54 |

| Happy | 35 | 32 | 34 |

| So-so | 12 | 13 | 9 |

| Unhappy/ | 3 | 3 | 3 |

100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Maternal employment | |||

| Not employed | 40 | 36 | 39 |

| Employed part time | 30 | 33 | 30 |

| Employed full time | 30 | 31 | 32 |

100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Family prayer | |||

| Very often/ | 56 | 62 | 60 |

| Sometimes | 14 | 13 | 13 |

| Rarely/ | 30 | 25 | 27 |

100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Family scripture study: | |||

| Very often/ | 26 | 29 | 34 |

| Sometimes | 18 | 19 | 19 |

| Rarely/ | 56 | 52 | 57 |

100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Family home evening: | |||

| Very often/ | 44 | 44 | 42 |

| Sometimes | 18 | 17 | 21 |

| Rarely/ | 38 | 38 | 37 |

100 | 99 | 100 |

The levels of family religious activity are also very similar. Over half of the families have family prayer “very often” or “often.” Fewer, about 44 percent, hold family home evening that often and about a third frequently participate in family scripture reading. The teenagers’ feelings of connectedness with their mothers and fathers are very similar for those living in the Pacific Northwest and Central Utah (see Table 8.6). (Family connectedness, regulation, and autonomy were not included in the questionnaire used on the East Coast.)

Table 8.6: LDS Youth’s Connectedness to Mother and Father by Region in Percentage

Percent who said “A lot like her (him)” | ||||

To Mothers | To Fathers | |||

My mother (father) is a person who . . . | West Coast (N=622) | Utah (N=1056) | West Coast (N=612) | Utah (N=1026) |

Makes me feel better after talking over my worries | 54% | 58% | 35% | 40% |

Smiles at me often | 65 | 67 | 49 | 50 |

Is able to make me feel better when I am upset | 54 | 53 | 40 | 40 |

Enjoys doing things for me | 70 | 68 | 67 | 63 |

Cheers me up when I am sad | 49 | 52 | 40 | 42 |

Gives me lots of attention | 62 | 64 | 47 | 48 |

Makes me feel like the most important person in her (his) life | 31 | 37 | 28 | 32 |

Believes in showing her (his) love for me | 71 | 72 | 57 | 57 |

Often praises me | 48 | 51 | 38 | 40 |

Is easy to talk to | 49 | 51 | 30 | 32 |

Around two-thirds of the youth feel their mothers enjoy doing things for them and smile at them often. The fathers are not as strongly connected as are the mothers to their teenage children. The youths’ perceptions of their parents’ regulation are also almost identical among the teens in the two different religious ecologies (see Table 8.7). Mothers are very much aware of where their teens are after school and when they go out at night. The majority of the mothers know their children’s friends and what their children do in their free time. The fathers in the two ecologies are significantly less involved in the regulation of their teenagers than are the mothers. As shown in Table 8.8, the levels of autonomy are very similar for mothers and for fathers. Not surprisingly, fathers grant their teens a little more autonomy than mothers. Again, the data clearly reveal that LDS families are very similar regardless of the religious ecology surrounding them.

Table 8.7: LDS Youth’s Perception of Parental Regulation, by Region

Percent who said “Knows a lot” | ||||

To Mothers | To Fathers | |||

My mother (father) is a person who knows . . . | West Coast (N=631) | Utah (N=1058) | West Coast (N=625) | Utah (N=1041) |

Who your friends are? | 61% | 63% | 31% | 34% |

Where you go at night? | 74 | 72 | 52 | 47 |

How you spend your money? | 47 | 48 | 27 | 27 |

What you do with your free time? | 57 | 55 | 39 | 34 |

Where you are most afternoons after school? | 80 | 74 | 45 | 39 |

The striking similarities of the youth and families living in three rather different geographical areas is remarkable. These LDS families have similar structure, religious practices, and parent-child relationships, and the young people are very similar in their religiosity and in their delinquency. It appears that LDS families are LDS families wherever they make their homes. The main difference was the higher number of LDS friends and the lower peer pressure to participate in delinquent activities experienced by the youth living in Utah.

Table 8.8: LDS Youth’s Perception of Family Autonomy, by Region in Percentage

Percent who said “Not like her (him)” | ||||

To Mothers | To Fathers | |||

My mother (father) is a person who . . . | West Coast (N=625) | Utah (N=1053) | West Coast (N=616) | Utah (N=1024) |

Tells me all the things she (he) has done for me | 31 | 30 | 42 | 37 |

Says if I really cared for her (him), I would not do things that cause to worry | 63 | 62 | 70 | 68 |

Is always telling me how I should behave | 37 | 36 | 42 | 40 |

Would like to be able to tell me what to do all the time | 52 | 55 | 53 | 54 |

Wants to control whatever I do | 60 | 63 | 61 | 62 |

Is always trying to change me | 67 | 64 | 70 | 67 |

Only keep rules when it suits her (him) best | 61 | 56 | 61 | 57 |

Is less friendly with me if I do not see things her (his) way | 52 | 50 | 51 | 48 |

Will avoid looking at me when I have disappointed her (him) | 67 | 65 | 68 | 67 |

If I hurt her (his) feelings, stops talking to me until I please her (him) again. | 69 | 69 | 74 | 74 |

Delinquency Model

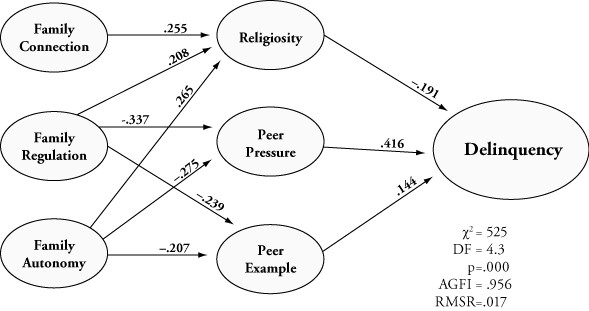

The results of the test of the model are presented in Figure 8.2. Since we did not include the family regulation and family autonomy items in the questionnaire sent to the East Coast sample, the model was tested with data from the Pacific Northwest and central Utah samples. Not surprisingly, pressure from peers to commit delinquent activities emerged as the strongest predictor of delinquency. The beta coefficient between peer pressure and delinquency is .416. The positive beta indicates that as peer pressure increases, so does delinquency. Betas range from 1.00, which would signify a perfect relationship between peer pressure and delinquency, to 0.00, which would indicate absolutely no link between the variables. Statisticians generally agree that in structural equation modeling, a beta coefficient above .05 indicates a statistically significant relationship and a beta above .10 indicates a substantive relationship. Thus, a beta of .416 reveals a very strong relationship between peer pressure and delinquency.

Peer example also made a significant contribution to explaining delinquency independent of peer pressures (beta =. 144). LDS young people who have friends who participate in delinquent behavior tend to imitate them, even though their friends may not directly pressure them to do so.

Religiosity also has a strong relationship to delinquency when the effects of peer pressure and example have been statistically controlled. The -.191 beta indicates that as religiosity increases, delinquency decreases. In the model shown in Figure 8.2, we combined the five dimensions of religiosity into an overall religiosity score. Not surprisingly, the results suggest that those youth who have made religion an important part of their personal life and have experienced the spiritual benefits of their beliefs and practices are better equipped to resist peer pressures, to avoid delinquent behavior, and less likely to choose delinquent friends.

Figure 8.2: Revised Model of Delinquency

Figure 8.2: Revised Model of Delinquency

As noted in Figure 8.1, we anticipated that the family would have both direct and indirect effects on delinquency. It was predicted that strong LDS families would not only influence family members to not engage in delinquency but would also assist their children in choosing desirable friends, give their children greater support to resist negative peer pressure, and help their children to internalize religious values.

The direct effects of family on delinquency are insignificant. Single-parent families, working mothers in unhappy family environments, feelings of connection with parents, parental regulation, and family autonomy are not directly related to delinquency. However, the indirect effects are rather powerful in explaining the delinquency of LDS youth. Connectedness to parents or feelings of closeness to parents is strongly related to religiosity (beta = .255), which in turn is negatively related to delinquency. Family regulation is significantly related to religiosity (beta = .208), which, as mentioned above, is negatively related to delinquency. Family regulation is also negatively related to peer pressure (beta = -.337) and to peer example (beta = -.239), both of which are strongly related to delinquent activity among LDS youth. Family autonomy—psychological freedom parents allow their children—was also found to be strongly related to religiosity (beta = .265), peer pressure (beta = -.275), and peer example (beta = -.207). Family structure, maternal employment, and family environment did not make a significant contribution to understanding delinquency when these parenting practices were included in the model. Thus, single parents, working mothers, and parents who are unhappy with each other (but who are connected with their children), parents who monitor and regulate their children, and parents who grant them appropriate autonomy or agency produce competent adolescents. These three parenting practices appear to have a powerful relationship with the religiosity of the teenagers, the youths’ selection of friends, and their ability to resist friends’ influence to participate in delinquent activities.

LISREL calculates three measures of how well the observed data fit the theoretical model. A chi-square measures the overall fit between the covariance structure of the variables in the model and the covariance structure of the observed variables. The lower the X2, the higher the probability the observed data fit the model. As seen in Figure 8.2, the X2 for the delinquency model is 525 with 413 degrees of freedom, which suggests a reasonable fit. A goodness of fit index (GFI) is also calculated, which identifies the amount of variance and covariance jointly explained by the model. A GFI of 1.00 indicates a perfect fit between model and data. The GFI, when adjusted for the degrees of freedom, is .956, which also indicates a good fit. Finally, the root mean square residual (RMSR) is the average difference between each indicator in the model and its observed value. The lower the RMSR, the better the fit. A perfect fit would produce a RMSR of 0.00. The RMSR for this delinquency model is .017, which also indicates a good fit between the theoretical model and the observed data. These three tests substantiate that the model of delinquency is strongly confirmed by the information collected from the LDS youth.

The two measures of peer influence, religiosity, and the family characteristics of connectedness, regulation, and autonomy accounted for 40 percent of the variance in delinquency among LDS youth. A portion of the remaining 60 percent of the variance is accounted for by error in measuring delinquency, peer influences, religiosity, and family characteristics. Obviously, factors in addition to those included in the model are also responsible for explaining delinquency among LDS teens. While future research should seek to identify additional significant predictors, it should be noted that these three sets of factors account for a rather large proportion of the delinquency of these LDS youth.

Religiosity and Delinquency

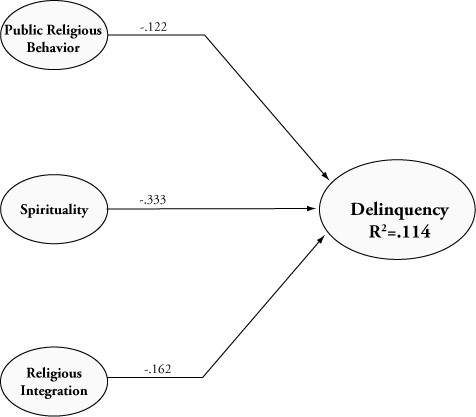

We did an additional LISREL analysis to determine the relative strength of the relationship between the five dimensions of religiosity and delinquency. The model tested is presented in Figure 8.3. LISREL’s calculation of a measurement model noted multicolinearity between religious beliefs, private religious behavior, and spiritual experience. Therefore we combined these three dimensions into one that we have labeled spirituality. These three dimensions are the “stuff of which a testimony of the gospel is made.

Figure 8.3: Model with Five Dimensions of Religiosity Predicting Delinquency

Figure 8.3: Model with Five Dimensions of Religiosity Predicting Delinquency

Figure 8.4: Revised Model of Religiosity Predicting Delinquency

Figure 8.4: Revised Model of Religiosity Predicting Delinquency

The results of the analysis are presented in Figure 8.4. As can be seen, spirituality was by far the strongest predictor of delinquency among these LDS young people as indicated by the -.333 beta. In other words, those youth for whom religion was an important internal aspect of their lives resisted peer pressures, negative peer examples, and avoided delinquency to a greater extent. Feelings of acceptance in the ward and among other teenagers in the ward also made a contribution to predicting delinquency (beta -.162). Public attendance at meetings had a weak relationship to delinquency (beta -.112). It appears that the key to deterring delinquency and immoral behavior among LDS youth is not found merely in getting the youth into the Church but rather in getting the Church (personal testimony) into the youth.

Implications

Religious ecology.

One important insight gained from this study is that geography or religious ecology does not really matter in understanding delinquency among LDS youth. It is amazing how similar LDS youth and their families are—regardless of whether they live in the “mission field” or in central Utah. The family characteristics were virtually the same in all three regions, as were family prayer, scripture study, and family home evenings. The religiosity of the youth and their levels of delinquency were very similar. The only real difference was the higher percentage of LDS friends among the youth living in central Utah. Thus, it appears that it is not so much where a family lives that determines if their teenagers avoid delinquency as much as it is what goes on within the walls of that home and within the heart and soul of the youth.

Importance of family.

A second important insight is that the home truly matters. The family characteristics included in this study—family connectedness, regulation, and autonomy—play significant roles in youth developing the religious values and behaviors that mitigate the negative influences of peers and that deter delinquent behavior. Parents can do much to help youth internalize the gospel.

Parents must teach their children by precept and example about the gospel externally, but must also strive to find ways for children to experience the gospel internally. Elder Joe J. Christensen (1996), of the Presidency of the Seventy, wrote: “One of the most effective ways to gain personal spiritual experiences and testimony is to become personally involved in serving, searching, and pondering and praying” (pp. 90–91). He also urged that “We parents need to take seriously our responsibility to provide religious training in the home so that our children will in turn take religion seriously and personally . . . praying, holding family home evenings, and studying the scriptures with our children are important foundations. As we strive to create a spiritual environment, our family members can be led to those experiences that will help them build their own personal testimonies” (pp. 90–92).

This study empirically validates the inspired counsel given to members of the Church for generations by the living prophets. It demonstrates that, as Elder M. Russell Ballard (1996) recently declared, “The family is where the foundation of personal, spiritual growth is built and nurtured” (p. 81). He commented: “The home and family have vital roles in cultivating and developing personal faith and testimony. The family is the basic unit of society; the best place for individuals to build faith and strong testimonies is in righteous homes filled with love. Love for our Heavenly Father and His Son Jesus Christ is greatly enhanced when the gospel is taught and lived in the home. True principles of eternal life are embedded in the hearts and souls of young and old alike when scriptures are read and discussed, when prayers are offered morning and night, and where reverence for God and obedience to Him are modeled in everyday conduct. Just as the best meals are home cooked, the most nourishing gospel instruction takes place at home. Strong, faithful families have the best opportunity to produce strong, faithful members of the Church” (p. 81).

While family values and practices only indirectly affect delinquency, they strongly contribute to the religiosity of the individual LDS teenagers. Parental love, teachings, and regulation will help mitigate negative peer influences that are so powerful in leading youth astray. As President James E. Faust (1990) declared, “When this belief becomes part of their very souls, they have inner strength” (p. 34). He also stated: “Generally, those children who make the decision and have the resolve to abstain from drugs, alcohol, and illicit sex are those who have adopted and internalized the strong values of their homes as lived by their parents. In times of difficult decisions they are most likely to follow the [religious] teachings of their parents rather than the example of their peers or the sophistries of the media which glamorize alcohol consumption, illicit sex, infidelity, dishonesty, and other vices” (p. 34).

Through the internalization of spiritual values, LDS youth are protected from the “fiery darts of the adversary” by being enveloped in the “armor of God.” President Boyd K. Packer (1995) has declared that that which “is most worth doing must be done at home” (p. 9). He concluded:

The ministry of the prophets and Apostles leads them ever and always to the home and the family. That shield of faith is not produced in a factory, but at home in a cottage industry.

The ultimate purpose of all we teach is to unite parents and children in faith in the Lord Jesus Christ, that they are happy at home, sealed in an eternal marriage, linked to their generations, and assured of exaltation in the presence of our Heavenly Father.

Lest parents and children be “tossed to and fro” and misled by “cunning craftiness” of men who “lie in wait to deceive” (Ephesians 4:14), our Father’s plan requires like the generation of life itself, the shield of faith is to be made and fitted in the family. No two can be exactly alike. Each must be handcrafted to individual specifications.

The plan designed by the Father contemplates that man and woman, husband and wife, working together, fit each child individually with a shield of faith made to buckle on so firmly that it can neither be pulled off nor penetrated by those fiery darts.

It takes the steady strength of a father to hammer out the metal of it and the tender hands of a mother to polish and fit it on. Sometimes one parent is left to do it alone. It is difficult, but it can be done.

In the Church we teach about the materials from which a shield of faith is made: reverence, courage, chastity, repentance, forgiveness, compassion. In church we can learn how to assemble and fit them together. But the actual making of and fitting on of the shield of faith belongs in the family circle. Otherwise it may loosen and come off in a crisis, (p. 8)

What can we learn from this study that will help parents clothe their children with the protective “shield of faith” about which President Packer spoke? Family religious practices such as family prayer, family home evening, and family scripture study in and of themselves seem to have little relationship to delinquency. Undoubtedly these practices are essential elements of successful LDS families, but it appears that the overall spiritual environment of the home plays a more significant role than these outward behaviors. Generally speaking, those youth who most successfully resist peer pressures to engage in delinquent behavior come from homes where parents teach and live gospel principles and allow their teenagers their agency but guide and direct them through high expectations, family rules, and accountability for their choices. Parents of good teenagers do not seek to control their behavior through intimidation, fear, guilt, or the withholding of love and affection. Family connectedness, regulation, and autonomy create an environment of love, respect, and accountability.

Creating feelings of connectedness with teenagers is sometimes difficult. Adolescents often try to sever or weaken ties with parents in preparation for leaving home and assuming adult roles. Many times their efforts at independence seem like they are rejecting their parents. Patience and unfeigned love are required to maintain supportive ties with teens as they struggle through this stressful phase of life.

Monitoring teens’ behavior is an arduous task that requires consistent effort from parents. It requires talking and listening to youth as well as knowing who teens hang around with, times when they are not at home, whether homework or household chores are completed, how they dress, the movies they attend, the music they listen to, and how they spend their money. Also, parents must watch for warning signs such as declining school work, long absences from home, hostility or anger toward family members, skipping church meetings, and so on. Equally important is the formulation of family rules that specify inappropriate behavior and the enforcement of those rules. Parents must extend a level of trust that allows their teens to experience this moral agency. Such autonomy helps teens to develop the ability to make good choices and to resist temptations to engage in “exciting” activities that promise momentary pleasure. Making good decisions helps teens develop a sense of worth that also strengthens their ability to resist temptation. When parents observe that a teen has violated a rule, the appropriate punishment or consequence must be meted out. Most parents find disciplining their teenager a trying and frustrating experience. However, without attaching consequences to misbehavior, youth fail to learn one of life’s greatest lessons—eventually they will reap the rewards of what they have sown (see Gal. 6:7–9).

From the results of this study it is clear that if parents wish their teenage children to mature into competent and contributing members of society, they must establish a loving relationship with them. Within this supportive relationship, parents must then establish family rules and appropriate consequences for violation of those rules. Parents must entrust their children with agency to choose to obey or disobey the family rules. Considerable effort must be expended to monitor the behavior of teenage children to ascertain whether they are making good decisions and following family rules. Finally, when disobedience or mistakes occur, parents must do that which is rather painful—discipline the offender. As the scriptures state, it is important to restore the connectedness by “showing forth an increase in love” after the discipline (see D&C 121:41–44).

A spiritual home environment is more than just activity in the Church or regular family home evenings. It is making the principles of the gospel the center of the home—not just in words, but in practice.

Importance of religiosity

As previously stated, it was discovered that internalization of religion, private religious behavior, the importance attached to one’s relationship with their Heavenly Father, and feeling the Spirit were most important in predicting delinquency. Therefore, parents must strive to do those things that foster internalization of religious values in their children. As President Boyd K. Packer noted, one size does not fit all teens; parents must seek the guidance of the Spirit to create the experiences for each of their children that will assist them in internalizing the gospel.

It is clear that family life and religiosity are intertwined, as the internalization of religious values and standards are strongly influenced by family processes. Parents who desire that their teenagers emerge from adolescence as competent young adults and faithful Latter-day Saints can greatly increase the probability of this outcome by maintaining a supportive and spiritual family environment.

Whether we are parents, leaders, teachers, or youth advisors, we can best insulate LDS youth from immorality, drug and alcohol abuse, and other acts of delinquency by fostering within the home and church the internalization of gospel principles. It is essential that we help our youth to see and feel the gospel in action and not just in doctrine or theory. Expecting attendance at church meetings and participation in recreational activities to keep youth out of trouble is neglecting the more powerful means of strengthening young people. It is activities within the home and at church that promote the internalization of religious values that clothe youth in the “shield of faith.” When President Heber C. Kimball’s (1888) prophecy about the last days comes to pass, it will be imperative that all members of the Church be protected by such a shield. He prophesied: “Let me say to you, that many of you will see the time when you will have all the trouble, trial and persecution you can stand, and plenty of opportunities to show that you are true to God and his work. This Church has before it many close places through which it will have to pass before the work of God is crowned with victory. To meet the difficulties that are coming, it will be necessary for you to have a knowledge of the truth of this work for yourselves. The difficulties will be of such a character that the man or woman who does not possess this personal knowledge or witness will fall. . . . The time will come when no man nor woman [or youth] will be able to endure on borrowed light. Each will have to be guided by the light within himself. If you do not have it, how can you stand?” (as cited in Whitney, 1967, p. 450).

References

Ballard, M. R. (1996, May). Feasting at the Lord’s table. Ensign, 80–82.

Barber, B. K., Olsen, J. E., & Shagle, S. C. (1994). Association between parental psychological and behavioral control and youth internalized and externalized behaviors. Child Development, 65, 1120–1136.

Chadwick, B. A., & Top, B. L. (1993). Religiosity and delinquency among LDS adolescents. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 32 (1), 51–67.

Christensen, J. J. (1996). One step at a time: Building a better marriage, family, and you. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book.

Dornbusch, S. M, Ritter, P. L., Liederman, P. H., Roberts, D. R, & Fraleigh, M. J. (1987). The relation of parenting style to adolescent school performance. Child Development, 58, 1244–1257.

Faust, J. E. (1990, November). The greatest challenge in the world—good parenting. Ensign, 34.

Johnston, L. D., Bachman, J. G, & O’Malley, P. M. (1993). Monitoring the future: Questionnaire response from the nation’s high school seniors. Ann Arbor, MI: Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan.

Packer, B. K. (1995, May). The shield of faith. Ensign, 8–9.

Schaefer, E. S. (1965). Children’s reports of parental behavior: An inventory. Child Development, 36, 413–424.

Stark, R. (1983). Religion and conformity: Reaffirming a sociology of religion. (Presidential address, The Association for the Sociology of Religion), Sociological Analysis, 45 (4), (1984), 273–281.

Stark, R., Kent, L., & Doyle, D. P. (1982). Religion and delinquency: The ecology of a ‘lost’ relationship.” Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 19, 4–24.

Steinberg, L., Fletcher, A., & Darling, N. (1994, June). Parental monitoring and a peer influences on adolescent substance use. Pediatrics, 93, 1060–1064.

Whitney, O. F. (1967). The life of Heber C Kimball: An apostle, the father and founder of the British Mission. Salt Lake City: Bookcraft. (Original work published 1888.)