Familial and Religious Influences on Suicidal Ideation

Jie Zhang and Darwin L. Thomas

Jie Zhang and Darwin L. Thomas, “Familial and Religious Influences on Suicidal Ideation,” in Religion, Mental Health, and the Latter-day Saints, ed. Daniel K. Judd (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1999), 215–236.

Jie Zhang was assistant professor of sociology at Weber State University and Darwin Thomas was professor of sociology at Brigham Young University when this was published. This article was originally published in Family Perspective 25:301–321; reprinted with permission.

Abstract

This chapter explores suicidal ideation and its influential factors among students at Brigham Young University. It was found that this sample had a lower rate of suicidal ideation than other college students nationally. The two strongest predictors for suicide are depression and attitudes favoring suicide, both of which are greatly influenced by one’s religiosity. Results also show that although family cohesion does not directly affect suicidal ideation, it does have a strong impact on depression and the student’s level of religiosity. The study found that strong families that actively encourage religious belief and behavior will reduce suicidal ideation among their adolescent children.

Theoretical Perspective

Traditionally, researchers who study suicide have used two theoretical models: the social structural model and the psychological model[1]. Social structural researchers see suicide as a result of environmental determinants. Their research focuses on environmental factors that distinguish suicidal from nonsuicidal subjects. Psychological researchers see suicide as a result of personological determinants. Their research focuses on personal characteristics, or traits distinguishing suicidal from nonsuicidal subjects. Durkheim (1951) suggested that suicide, although a personal behavior, does not result solely from individual influences, but results from social environmental influences as well.[2]

In criticizing the common belief that depression causes suicidal behavior, Durkheim argued that the suicide rate is higher among males than among females, while females are more likely to be depressed. A major reason for suicidal behavior, according to Durkheim, is the lack of social integration. While many suicidal people have experienced major life stress and depression, most individuals who experience similar stress and depression do not commit suicide or think about suicide.

Empirical studies have generally supported the Durkheimian formulation. High school youngsters who were integrated into their families and who described family life in terms of a high degree of mutual involvement, shared interests, and emotional support were 3.5 to 5.5 times less likely to be suicidal than were adolescents from less cohesive families who had the same levels of depression or life stress.[3] The role of family factors in the genesis of suicidal behavior is at the core of most papers collected in the special issue on suicide in Family Perspective (Vol. 24, No. 1,1990). Although the relationship between divorce and suicide is weakening as divorce becomes more and more common [4], divorce is still an important predictor of suicide. [5] Although there is some evidence that family variables may be less important today than in the 1960s, they still remain highly significant. [6]

Other variables for which some support has been found include living alone, gun availability, and presence of children. Gundlach (1990) combined aspects of the Durkheimian social integration model with the opportunity perspective. Gundlach’s theoretical combination was based on opportunity (gun availability) as a social context that affects the linkage between family integration and suicide. In an analysis of seventy-seven Metropolitan Statistical Areas, Gundlach found strong support for his hypothesis that in areas with high gun availability, low family integration is strongly related to suicide. [7]

Pescosolido and Wright (1990) hypothesized that the effect of family factors on suicide should vary according to stage of life, and gender. They found that the presence of children lowers the propensity for suicide among women through increasing family integration. [8]

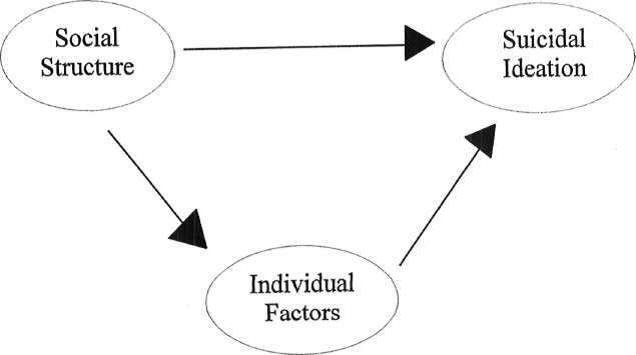

The purpose of the present study is to test an integrated model in which suicidal ideation is predicted simultaneously by individual characteristics (such as religiosity, future expectation, substance abuse, and depression) and social structural characteristics (such as family cohesion, parents’ education, and family members’ substance abuse). A fundamental assumption of the preliminary model is that explanations of suicidal ideation will have to include both sources on influence, and specify how individual and environmental variables are related to each other. The theoretical model (Figure 11.1) assumes suicidal ideation to be an individual behavior, which is influenced by the social structure both directly and indirectly through other individual level behaviors.

Figure 11.1: The Theoretical Model of Suicidal Ideation

Figure 11.1: The Theoretical Model of Suicidal Ideation

Specific theoretical model. While the theoretical perspective (Figure 11.1) is used as a general guide, a more specific model needs to be developed for empirical testing. The specific model is built from the general theoretical perspective discussed above and from previous studies on suicide.

According to Hawton, O’Grady, Osborn, and Cole (1982), family problems were ranked as one of the most important contributors to adolescent suicide.[9] Family problems include poor communication, value conflicts with parents, alienation of the adolescent from the family; as well as inadequate love, affection, and support from family members. In a general sense, these family problems can be seen as indicators or consequences of low family cohesion. Therefore, this research posits low family cohesion as a major cause of adolescent suicide.

Religion is another important factor. In a sample of British university students, Salmons and Harrington (1984) found that those who were members of a religion differed significantly from nonmembers: 50 percent of religious respondents had suicidal ideas compared to 57 percent for those with no religious affiliation. [10] Since religious involvement increases social integration, it is expected that religious involvement will decrease suicidal ideation as well as suicide.[11]

Family cohesion and adolescent religiosity are associated with each other. Thomas, Gecas, Weigert, and Rooney (1974) concluded that a youth receiving a high degree of support and control tends to be a conforming youth.[12] Since religiosity is one manifestation of conforming behavior, and support and control in the family are both elements of family cohesion, it is hypothesized that the higher degree of support and control a youth receives from the family, the higher the youth’s religiosity.

In addition to familial and religious influences on suicidal ideation, parental education may be associated positively with the adolescent’s future expectations. The more parents are integrated into the social order, the more likely their children will develop future expectations about their own abilities to succeed in their career plans. While no research has linked future expectations to suicidal behavior, a number of studies have shown that adolescents’ future expectations predict a number of pro-social outcomes such as social competency, and religiosity.[13] In the study conducted by Rudd (1990), a significantly greater number of subjects whose mothers had not obtained a high school diploma experienced more serious suicidal ideation than did those whose mothers had completed high school or college. [14] Thus, we hypothesize that future expectations will be negatively related to suicidal ideation.

Correlations between substance abuse and suicidal ideation have been documented by many researchers. Hodgman and Roberts (1982) and Harlow, Newcomb, and Bentler (1986) have suggested that delinquency, alcohol use, and drug use are manifestations of depressed adolescents. [15] This depression usually precedes suicidal behaviors. In studies by Mehryar, Hekmat, and Khajavi (1977), Harlow et al., and Dukes and Lorch (1989), strong relations were found between suicidal ideation and substance abuse, such as drinking alcohol and using drugs.[16]

Family members’ substance abuse behaviors directly influence adolescents. In his study of adolescent substance abuse, Kent (1987) found that substance abuse by parents has a strong impact upon adolescents’ decisions on whether or not to do the same.[17] Therefore, it is hypothesized that family members’ substance abuse is positively associated with the adolescents’ substance abuse. Since family is one of the most important socialization agents, family members’ drug or alcohol use should have a strong impact upon adolescents’ psychological- personal behaviors. Adolescent emotional and ideological disparity with parents was found to be linked to suicide ideation through such intervening variables as drug and alcohol use. [18] Although no literature has yet connected suicidal ideation and family substance abuse, a positive relation is hypothesized in the model.

Several studies have linked emotional problems to suicide and suicidal ideation. [19] Emotional problems, particularly depression, have been associated with adolescent suicidal attempts. [20] In studies of the general population, Paykel, Myers, Lindenthal, and Tanner (1974) and Vandivort and Locke (1979) found emotional difficulties related to suicide ideation. [21] Carlson and Cantwell; Pfeffer, Zuckerman, Plutchik, and Mizruchi (1984); and Simons and Murphy (1985) reported a relationship between depression and suicidal ideation for adolescents. [22] Therefore, depression could be a strong predictor of suicidal ideation.

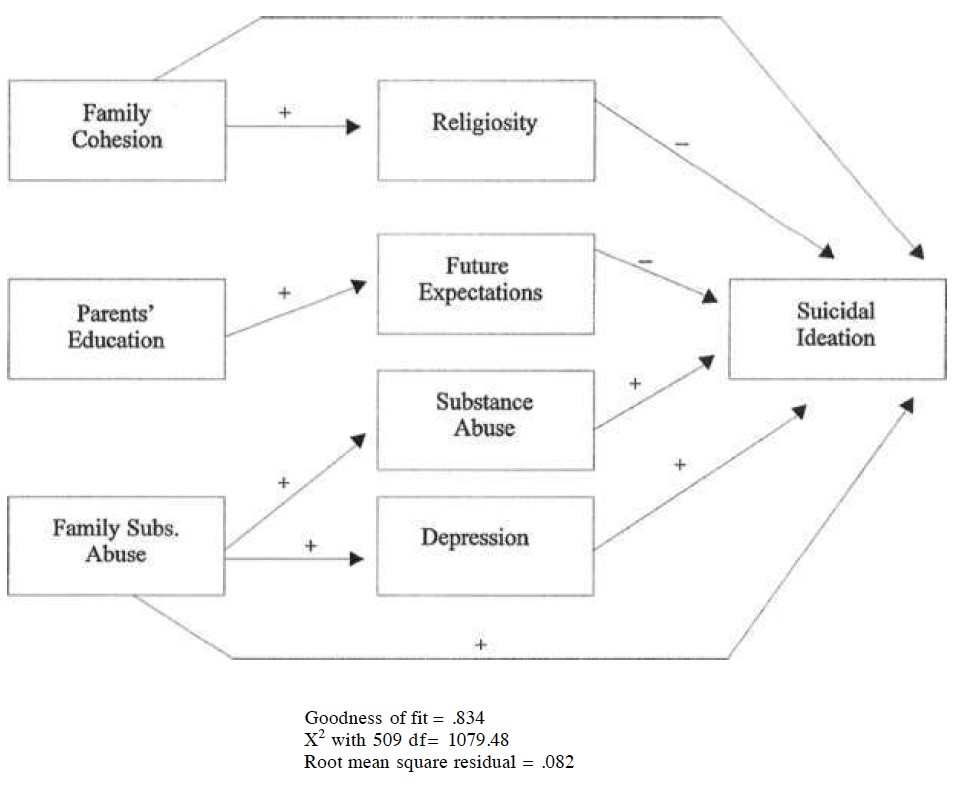

Taken together, these various studies suggest a model for the explanation of adolescent suicidal ideation (see Figure 11.2). This model poses a two-step process in which social structural factors impact psychological-individual factors which increase the probability of suicidal ideation. Stated differently, some of the effects of the social structural variables upon suicidal ideation are assumed to be mediated by the psychological-individual variables. What is not known from the extant research and theory is whether the social structural variables will have direct effects on suicidal ideation over and above the indirect effects through the psychological variables. As shown in Figure 11.2, this theoretical model assumes that some family variables will still have a direct effect on the dependent variable.

Figure 11.2: Preliminary LISREL Path Model

Figure 11.2: Preliminary LISREL Path Model

Method

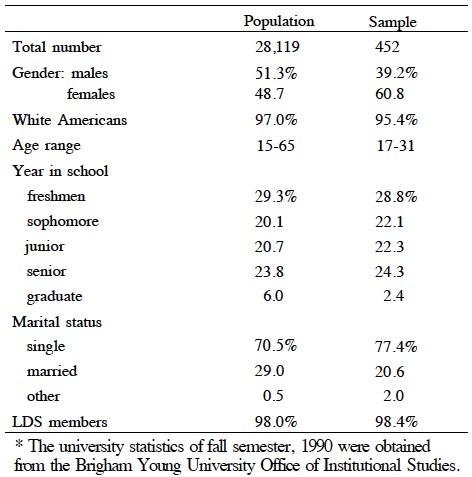

Subjects. The sample was drawn from the Brigham Young University student body. Subjects included 452 students (177 males and 275 females) from several conveniently selected classes in the university during the fall semester of 1990. The majority (95 percent) were white Americans from well-educated, middle-class families. They ranged in age from seventeen to thirty-one, and were well distributed among the four school years. Twenty percent of them were married, 77 percent were never married, and the rest were either divorced, separated, or widowed. Almost all (97 percent) of the respondents were members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which sponsors the university. When compared with the demographic statistics of Brigham Young University students (Table 11.1), the sample appears to be representative of the student body, although the sample had an over-representation of female students. The respondents were administered a questionnaire soliciting their demographic information, intensity of religious belief, family situation and cohesiveness, plans for the future, depression, substance abuse, and times of suicidal thoughts and attempts.

Table 11.1: A Demographic Comparison between the Research Sample and the University Population*

Table 11.1: A Demographic Comparison between the Research Sample and the University Population*

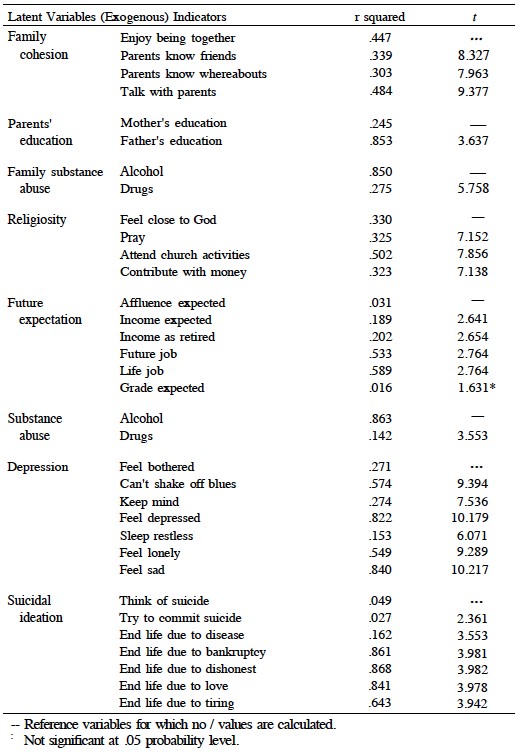

Table 11.2: Squared Multiple Correlations between the Latent Variables and Their Indicators for the Preliminary Model

Table 11.2: Squared Multiple Correlations between the Latent Variables and Their Indicators for the Preliminary Model

Measurement .Variables in the theoretical model are shown in Figure 11.2. Social structural environments that are assumed to impact suicidal ideation include family cohesion, parents’ education, and family members’ substance abuse. Individual psychological behaviors through which the social environments influence suicidal ideation include the respondents’ religiosity, future expectation, substance abuse, and depression.

Table 11.2 presents each of the variables and their indicators. Under the heading of exogenous latent variables are the factors of social structure, while under the heading of endogenous latent variables are the factors of individual psychological behaviors. Each factor has two or more indicators.

The operational definition of each indicator used in the study is also illustrated by Table 11.2. Except for the substance abuse variables, all are continuous scales. Think of suicide is measured by the question “How many times in the previous years of your life has suicide occurred to you?” and try to commit suicide is measured by the question “Have you ever tried committing suicide in the previous years?” There were five responses to each question ranging from “none” to “so many times that I cannot remember.” Suicidal ideation is the dependent variable and includes five attitudinal items that measure respondents’ favorability toward suiciders in five different hypothetical situations.

Most independent variables are measured with similar responses for each item. Family cohesion consists of four items: (a) did you enjoy doing things with your family; (b) did your parents know your best friends; (c) did your parents know where you were when you were not at home; (d) did you talk to your parents about your problems? All four items are ordinal scales with five values from “not at all” to “very frequently.” Religiosity of the respondents is measured by four items: (a) how close do you feel to God most of the time; (b) how many times in one week do you usually say grace or give thanks to God aloud before meals; (c) how often do you attend religious services; (d) about how much do you contribute to your religion every year. The variables on depression are the same ones used in The National Survey of Families and Households. [23] Seven of the twelve items were used in the present research.

Results

Frequency of suicidal ideation. Among all the respondents, 43 percent reported that they had experienced at least one suicidal thought previously. This is considerably lower than found in other college students.[24] Of particular interest is the finding that unequal percentages of males and females were experiencing suicidal ideation—33 percent of the males and 47 percent of the females (chi-square p .005). This finding is congruent with the work of Saxon, Aldrich, and Kuncel (1978); Simons and Murphy (1985); Salmons and Harrington; and Sudak, Ford, and Rushford (1984); but contrary to that of Harlow et al. (1986); Strang and Orlofsky; R. J. Wellman and M. M. Wellman (1986, 1988); Dukes and Lorch (1989); Sherer (1985); and Rudd (1990). This suggests that males and females are different in their suicidal ideation rates. The current data also showed that 4 percent of the respondents had previously attempted suicide, which was significantly below the national figure of 13 percent that Mishara (1982) found for college students.

The measurement model. As a combination of factor analysis and multiple regression, LISREL allows for the simultaneous estimation of a measurement model and a structural model. A measurement model defines latent or underlying variables in terms of measured indicators, and a structural model estimates the relationships among the latent variables. A “good measurement model” is a model that fits the data, or in other words, a model with high squared multiple correlations. In addition, LISREL produces several goodness-of-fit tests which indicate how well the overall model (theoretical and measurement) fits the data.

The measurement model consists of the exogenous and endogenous latent variables, their indicators, and their error terms. Table 11.2 summarizes the findings concerning what percentage (squared multiple correlation) of the variance in each indicator can be explained by the underlying latent construct. The / values indicate the significance of these relationships.

The values in Table 11.2 reveal a number of problems with the measurement model. For example, the two items, think of suicide and try to commit suicide, are different from other attitude items, and are not well predicted by the latent construct. Also, there are two items in future expectations (affluence expected and grade expected) that are not good measures.

The squared multiple correlations for structural equations indicate how much variance in the endogenous latent variables can be explained by the model. The R squares for the latent constructs Religiosity, Future Expectation, Substance Abuse, Depression, and Suicidal Ideation are respectively .293, .030, .290, .192, and .042. This indicates that only 3 percent and about 4 percent of variance in Future Expectation and Suicidal Ideation respectively are explained by the model. Since all the squared multiple correlations for the structural equations are not significantly high, this model cannot be said to be a good one.

Several other analyses can be employed to test this LISREL model (see Figure 11.2). Goodness-of-fit index is a measure of the relative amount of variances and covariances accounted for by the model, and is independent of the sample size. In this model the goodness-of-fit index is .834, which is not as high as it should be since a perfect fit with the data would be 1.000.

Chi-square usually means the difference between the observed and the expected values. The higher the chi-square, the more difference exists between the observed and the expected values. For this model the chi-square is 1079.48 with 509 degrees of freedom, which is considerably larger than one would expect in a good fitting model. Root mean square residual is a measure of the average of the residual variances and covariances and should be interpreted in relation to actual sizes of the observed variances and covariances. The root mean square residual of this model is .082. Therefore, one would expect a smaller number than this in a good fitting model.

All these analyses indicate that the original model did not fit the data well. Modifications were made in both the measurement and the structural equation models after this initial analysis.

The Revised Model

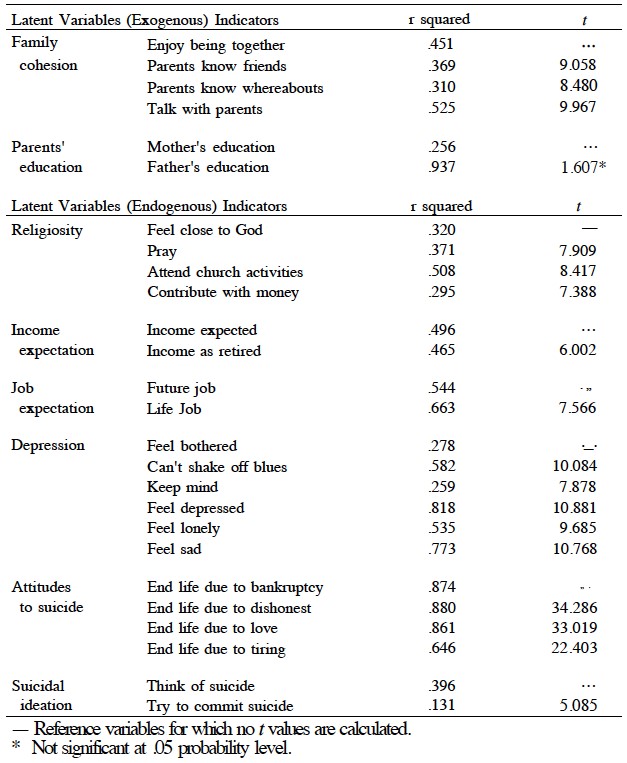

The measurement model. A factor analysis was used to improve the measurement and to modify some of the latent variables. The original three exogenous variables (Family Cohesion, Parents’ Education, and Family Substance Abuse) and two of the endogenous variables (Religiosity and Substance Abuse) stayed the same. Future Expectation split into two factors: income related and job related, with the indicators of affluence expected and grade expected as being poor measures of these two dimensions. For Depression, all the indicators loaded well except for sleep restless. The original indicators of Suicidal Ideation split into two dimensions. One consists of think of suicide and try to commit suicide, and the other includes all the items concerning suicidal attitudes with the exception of end life due to disease. This item was a poor measure and was therefore deleted.

Additional analysis showed problems with measures of Family Substance Abuse and Substance Abuse, each composed of two heavily skewed dichotomous items. They were excluded. A comparison of Table 11.2 and Table 11.3 shows that the revised model is considerably improved over the preliminary model.

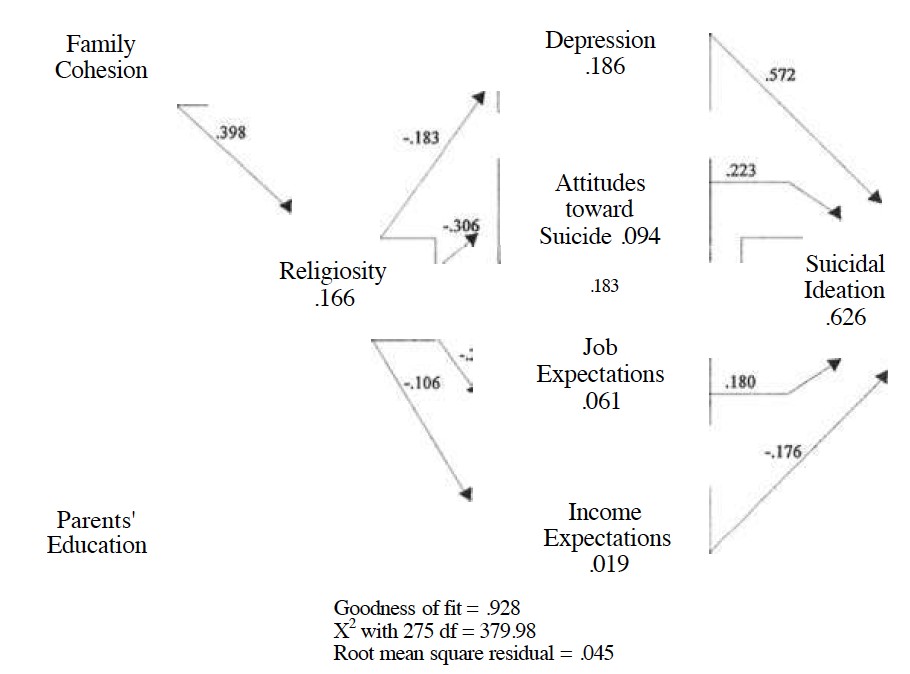

The structural model. In this revised model, the goodness of fit is .928, the chi-square with 275 degrees of freedom is 379.98, and the root mean square residual is .045. As to the squared multiple correlations for structural equations, more variances are explained by the new model: about 63 percent of variance in ideation is explained by the model in contrast to 4 percent in the preliminary model (see Figure 11.3).

Table 11.3: Squared Multiple Correlations between the Latent Variables and Their Indicators for the Revised Model

Table 11.3: Squared Multiple Correlations between the Latent Variables and Their Indicators for the Revised Model

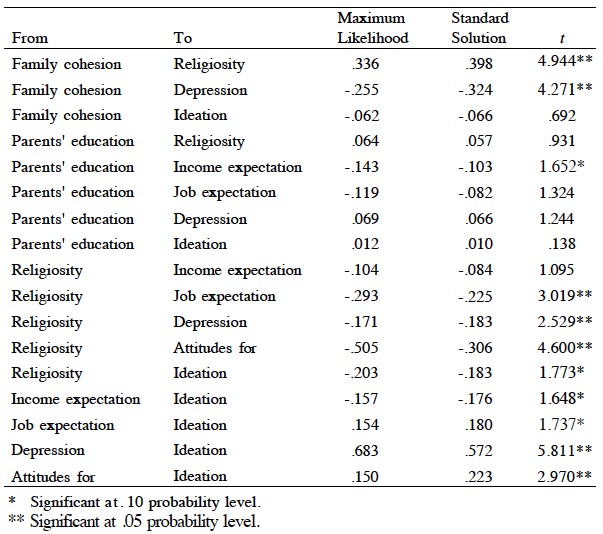

The revised LISREL model (Figure 11.3) demonstrates the relationships among social structures, individual characteristics, and suicidal ideation. The structural model is assessed using the figures reported by both the standardized solutions and the maximum likelihood methods (Table 11.4).

The maximum likelihood means that one unit of measurement of change in the independent variable will cause change in the dependent variable by that much (the unstandardized coefficient) in unit of measurement of the dependent variable. The standardized solution means that an increase of one standard deviation in one independent variable will bring about the change in the dependent variable by that much of standard deviation. Therefore, the standardized coefficients can be compared with each other to assess the relative strength of the relationship between any variables in the model.

Figure 11.3: The Restructured LISREL Path Model (Standardized solutions and variance in each endogenous variable explained by the model)

Figure 11.3: The Restructured LISREL Path Model (Standardized solutions and variance in each endogenous variable explained by the model)

Findings from the path model. The path model shown in Figure 11.3 indicates that social factors and individual characteristics influence college students’ suicidal ideation. The social institutions of religion and family have strong negative effects on suicidal ideation, but much of their influence can be accounted for by individual characteristics.

The data (see Table 11.4 and Figure 11.3) demonstrate that between the two social factors (family cohesion and parents’ education), family cohesion is a much better predictor of adolescents’ individual behaviors that influence suicidal ideation; while parents’ education only weakly decreases people’s future expectation in terms of income. Although family cohesion does not have a direct impact on suicidal ideation, it strongly predicts depression and religiosity. Depression is the strongest predictor of suicidal ideation. These data confirm previously reported findings that religiosity was negatively correlated with individuals’ favorable attitudes toward suicide, depression, and suicidal ideation. Likewise, the higher the family cohesion, the higher the religiosity and the lower the depression. Unexpectedly, religiosity is somewhat negatively related to future expectations. While income expectation decreases suicidal ideation, job expectation increases suicidal ideation.

Table 11.4: Assessments of the Structure Model

Table 11.4: Assessments of the Structure Model

Table 11.4: Assessments of the Structure Model

Discussion

The present research is a study of suicidal ideation and its influential factors among Mormon college students. The lower rate of suicidal ideation (43 percent) of this sample might be accounted for by the fact that these respondents are highly religious, and religiosity has consistently been shown to be negatively related to suicide. The LDS Church discourages suicidal behavior, [25] and Church members consider it to be a serious sin. Therefore, the LDS Church’s position on suicide may play a positive role in preventing young Mormons from committing suicide. We expect this to hold for most religions since participation in religion is a form of social integration and will be negatively related to suicide. However, research is needed to compare suicidal ideation across religious denominations to see whether some religions are better buffers against suicide than others.

Consistent with previous research was the finding that depression (+ .572) is most strongly related to suicidal ideation. Since family cohesion and religiosity have direct impacts on depression, family cohesion and religiosity influence suicidal ideation through intervening variables (depression, positive attitudes toward suicide, and future expectations). The second strongest predictor for suicidal ideation is attitudes favoring suicide (+ .223). Here, religiosity again plays an important role in influencing suicidal ideation through attitudes.

Income expectation and job expectation are both negatively related to religiosity. These relations could be explained by the fact that the more religious a person is, the more committed he or she is to the religion so as to de-emphasize the importance of the secular future. A second explanation for these relations might be the overrepresentation of female respondents (61 percent) in the sample. Women generally tend to be more religious than men, and traditionally, women are expected to be less ambitious than men in employment outside of the home.

Contrary to the hypothesis, future plans or expectations were not strongly related to suicidal ideation. Income expectation was negatively related to suicidal ideation, while job expectation is positively correlated with suicidal ideation. Also different from expectations was parents’ education, which was negatively related with income expectation. At least two things are implied by these findings. First, future expectations and parents’ education are not good predictors of adolescents’ suicidal behavior. Second, future studies with larger samples could be conducted to address these relations.

Since the substance abuse variables did not fit the preliminary model, and were deleted in the final path model, some important information about the substance abuse effects on suicidal behavior is missing. Further studies with better measures of substance abuse are expected to confirm the positive relations between drug/

Attitudes may not necessarily cause ideation. R. J. Wellman and M. M. Wellman (1988) and Minear and Brush (1980) reported that students who had engaged in more serious suicide ideation or behavior accepted suicide to a greater extent than those who had had less serious or no suicide ideation.[26] According to Festinger’s cognitive dissonance theory (1957), people tend to change their attitude if it has been inconsistent for some time with their behavior. This usually involves changing their attitude so that it becomes consistent with their behavior. [27] If suicidal ideation (behavior) had already occurred to an individual, the chance for this person to think favorably (attitude) about others’ suicide would be great. Based on this argument, the model was tested again, placing ideation before attitude, with the assumption that some people thought favorably about others’ suicide just because they themselves had experienced suicidal ideation. Only 9 percent of the variance in attitudes and 22 percent of the variance in ideation were explained by this model. This was not a better model. Therefore, in this sample ideation appeared to be more a result of general suicidal attitudes than the reverse.

As indicated by the research, family cohesion does not have a direct impact on the Mormon youths’ suicidal ideation, but it has strong indirect impacts through the youths’ level of religiosity and depression. Being part of social integration, family cohesion in this research further confirms Durkheim’s thesis that lack of social integration along with individual characteristics is a better causal model of suicide.

Only 68 percent of children live with both biological parents. [28] Boys from divorced families tend to become “under-controlled,” while girls are likely to become “overcontrolled”—anxious, withdrawn, or too well behaved. [29] These findings, along with the research reported here, imply that the family may be an important social institution in lowering suicide rates. The importance of religion along with that of the family implies that efforts at reducing suicidal ideation will be most successful if interventions are developed which improve family cohesion and encourage religious belief and practice among older adolescents.

Although the integrated model presented in this paper explains a fairly large proportion of the variance in suicidal ideation (63 percent), a considerable amount is left unexplained. It is hoped that the relationships outlined here will lead to a more thorough and precise understanding of the suicidal process. After all, the better we understand the process by which a youth becomes susceptible to suicide via ideation, the more appropriate, effective, and timely our interventions will be.

Notes

[1] Braucht, G. (1979). Interactional analysis of suicidal behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 47, 653–669.

[2] Durkheim, E. (1951). Suicide: A study in psychology. New York: Free Press.

[3] Rubenstein, J. L., Heeren, T., Housman, D., Rubin, C, & Stechler, G. (1989). Suicidal behavior in “normal” adolescents: Risk and protective factors. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 59, 59–71.

[4] Kowalski, G S. (1990). Marital dissolution and suicide in the United States for the 1980s: A 10-year comparison. Family Perspective, 24, 33–40. Also see Stafford, M. C, Martin, W. T., & Gibbs, J. P. (1990). Marital status and suicide: Within-column tests of the status integration theory. Family Perspective, 24, 15–32.

[5] Gundlach, J. H. (1990). Absence of family support, opportunity, and suicide. Family Perspective, 24, 7–14. Also see: Kowalski, G S. (1990); Pescosolido, B. A., & Wright, E. R. (1990). Suicide and the role of the family over the life course. Family Perspective, 24, 41–60; Stafford, et. al (1990); Trovato, F., & Vos, R. (1990). Domestic/

[6] Stack, S. (1990). Introduction: Suicide and family factors. Family Perspective, 24, 3–5.

[7] Gundlach, J. H. (1990).

[8] Pescosolido, B. A., & Wright, E. R. (1990).

[9] Hawton, K., O’Grady, J., Osborn, M., & Cole, D. (1982). Adolescents who take overdoses: Their characteristics, problems and contacts with helping agencies. British Journal of Psychiatry, 140, 118–123.

[10] Salmons, P. H., & Harrington, R. (1984). Suicidal ideation in university students and other groups. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 30, 201–205.

[11] Durkheim, E. (1915). The elementary forms of the religious life. New York: Free Press.

[12] Thomas, D. L., Gecas, V., Weigert, A., & Rooney, E. (1974). Family socialization and the adolescent. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

[13] Roghaar, H. B. (1991). The influence of primary social institutions and adolescent religiosity on young adult male religious observance. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Brigham Young University. Also see Thomas, D. L., & Carver, C. (1990). Religion and adolescent social competence. In Thomas Gullota (Ed.), Advances in adolescent development: Vol. Ill the promotion of social competency in adolescence (pp. 195–219). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

[14] Rudd, M. D. (1990). An integrative model of suicidal ideation. Suicide and Life- Threatening Behavior, 20, 16—30.

[15] Hodgman, C. H., & Roberts, F. N. (1982). Adolescent suicide and the pediatrician. Journal of Pediatrics, 101, 118–123. Also see Harlow, L. L., Newcomb, M. D., & Bentler, P. M. (1986). Depression, selfderogation, substance use, and suicide ideation: Lack of purpose in life as a meditational factor. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 42, 5–21.

[16] Mehryar, A., Hekmat, H, & Khajavi, R. (1977). Some personality correlates of contemplated suicide. Psychological Report, 40, 1291–1294. Also see Harlow, L. L., Newcomb, M. D., & Bentler, P. M. (1986); and Dukes, R. L., & Lorch, B. D. (1989). The effects of school, family, self-concept, and deviant behavior on adolescent suicide ideation. Journal of Adolescence, 12, 239–251.

[17] Kent, R. (1987). The religiosity and parent/

[18] Dukes, R. L., & Lorch, B. D. (1989).

[19] Birtchnell, J., & Alarcon, J. (1971). The motivation and emotional state of 91 cases of attempted suicide. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 44, 45–52. Also see Maris, R. (1981). Pathways to suicide: A survey of self-destructive behaviors. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; and Weissman, M., Fox, K., & Kerman, G. (1973). Hostility and depression associated with suicide attempts. American Journal of Psychiatry, 130, 450–454.

[20] Carlson, G. A., & Cantwell, D. P. (1982). Suicidal behavior and depression in children and adolescents. American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 21, 361–368. Also see Crumley, F. E. (1979). Adolescent suicide attempts. Journal of American Medical Association, 241, 2404–2407.

[21] Paykel, E., Myers, J., Lindenthal, J., & Tanner, J. (1974). Suicidal feelings in the general population. British Journal of Psychiatry, 124, 460–469. Also see Vandivort, D. S., & Locke, B. Z. (1979). Suicide ideation: Its relation to depression, suicide and suicide attempt. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 9, 205–218.

[22] Carlson, G. A., & Cantwell, D. P. (1982). Also see Pfeffer, C. R., Zuckerman, S., Plutchik, R., & Mizruchi, M. S. (1984). Suicidal behavior in normal school children: A comparison with child psychiatric in patients. Journal of American Academic Child Psychiatry, 23, 416–423; and Simons, R. L., & Murphy, P. I. (1985). Sex differences in the causes of adolescent and suicide ideation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 14, 423–434.

[23] Bumpass, L., Sweet, J., & Call, V. (1990). The national survey of families and households. Madison, WI: Center for Demography and Ecology, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

[24] Mishara, B. L. (1982). “College students’” experiences with suicide and reactions to suicidal verbalizations: A model for prevention. Journal of Community Psychology, 10(2), 142–150. Also see Salmons, P. H., & Harrington, R. (1984); Strang, S. P., & Orlofsky, J. L. (1990). Factors underlying suicidal ideation among college students: A test of Teicher and Jacobs’ model. Journal of Adolescence, 13, 39–52; and Wellman, R. J., & Wellman, M. M. (1988). Correlates of suicide ideation in a college population. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 23, 90–95.

[25] The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (1991). General handbook of instructions. Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

[26] Wellman, R. J., & Wellman, M. M. (1988). Also see Minear, J. D., & Brush, L. R. (1980). The correlations of attitudes toward suicide with death anxiety, religiosity, and personal closeness to suicide. Omega, 11, 317–324.

[27] Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Evanston, IL: Row, Peterson.

[28] Bianchi, S. M., & Selzer, J. A. (1986). Life without father. American Demographics, 8, 43–46.

[29] Emery, R. E. (1982). Interparental conflict and the children of discord and divorce. Psychological Bulletin, 92, 310–330.