Future Prospects for Religion and Family Studies: The Mormon Case

Darwin L. Thomas

Darwin L. Thomas, “Future Prospects for Religion and Family Studies: The Mormon Case,” in The Religion and Family Connection: Social Science Perspectives, ed. Darwin L. Thomas (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1988), 357–82.

Darwin L. Thomas was a professor of sociology at Brigham Young University when this was published. He received his PhD from the University of Minnesota.

The increased emphasis in a variety of disciplines in the social sciences on the study of religion, along with more studies analyzing multiple institutions simultaneously such as religion and family (Abrahamson and Anderson, 1984; Thomas and Henry, 1985), and a social science encouraging more open dialogue from disciplinary adherents (Thomas and Sommerfeldt, 1984), argue for an optimistic view of the future of religion and family studies. We do not expect to see a return to the widespread neglect of religious studies that characterized the social sciences in the second, third, and fourth decades of this century (Thomas and Henry, 1985; Bergin, 1980; Beit-Hallahmi, 1974). In addition to the foregoing, we see a growing trend of religious organizations calling upon social science researchers to help them better understand the opportunities and challenges that churches face in helping individuals and families. Many of these social scientists are receiving recognition for their work (Howery, 1986).

Our optimistic projections must be tempered with an acknowledgment of the low status that family and religion studies carry in our contemporary social sciences. Universities by and large do not allocate large portions of available funds to encourage the study of religion and the family. Our conclusion of low status is based on the perception that the social sciences in general take their cues from the larger social order in determining the significant problems which deserve the major portions of available resources. Within the social sciences the study of religion and family have not competed effectively for an equal share of available resources. Similarly, the dominant institutions in society uniformly see family and religion as low-status entities. Even though 80 percent of the nation’s businesses are family owned and generate 50 percent of the G.N.P. (Meyer, 1987), business schools do not organize curriculum to focus on family businesses nor do they offer much by way of studying churches as businesses. Impressive legal careers are not made by becoming specialists in domestic law. Medical schools do not place training for the study of family medicine as a high priority specialty. A psychologist does not become president of the American Psychological Association by becoming a nationally known family psychologist or psychologist of religion. The list could go on, but these suffice to illustrate the low status of religion and familial emphases in the contemporary social order. We do not see radical change here.

In summary, we see increased activity in two areas, religion and family, which have traditionally been underfunded in the social sciences. We expect this increased activity to continue into the future for two basic reasons. One is the recognition by the social sciences of the remarkable staying power of both religion and family. The earlier dire predictions of the demise of both religion and the family coming from general theories of social change as well as specific theories of secularization have now been shown to be false (Hadden and Shupe, 1986; Roberts, 1984; Hout and Greeley, 1987; Bahr and Chadwick, 1985). As these researchers have noted, it is now past time for the social sciences to begin to ask questions about what it is in the contemporary American social order that sustains a belief and involvement in religious institutions as well as conviction that family life offers some of the most meaningful experiences for children and adults. Is the staying power of one institution related to the staying power of the other? The time is right for the social sciences to address such issues.

The second reason for our expectation of increased research activity is our conviction that research funded by religious organizations will make significant contributions to our understanding of the religion and family interface. Examples of such studies completed and currently under way are numerous. Hoge and Roozen’s study (1979) entitled Understanding Church Growth and Decline, and the multiple reports coming from the currently ongoing Notre Dame Parish study, are only two in a growing number.

Recent American research identified fifteen religious denominations that have ongoing research organizations which, taken together, are conducting hundreds of research projects. These include the Catholic, Jewish, Mainline Protestant, Mormon, [1] and many smaller denominations. (Anderson and Weed, in press.) An important development in encouraging research of this type is the Lilly Foundation’s research funding program which stipulates that the social science researchers work in cooperation with the churches in designing and conducting the research. In addition to these ongoing research organizations, most of the denominations encourage research conducted by and for their seminaries. In combination, the above represents an impressive amount of research information generated by and for the churches, which we think will add measurably to the social science knowledge base about religion and the family.

Potential Areas of Significant Contribution

Writing in 1984, we identified five areas of possible benefit from increased study of religion and the family. They were:

(1) Increase our understanding of the role of religion and family in social change.

(2) Better understand these two institutional influences on personal well-being.

(3) Encourage more social-psychological studies of religion as opposed to institutional analysis.

(4) Encourage a greater appreciation for the role of spiritual influences in the lives of people.

(5) Encourage a discussion of the role of presuppositions in the social scientist’s work. (Thomas and Henry, 1985.)

Our judgment is that the research published since 1984 corroborates the utility of this formulation. Indeed, the chapters in this book make important contributions to each of the above areas. For instance, the chapters in the section titled “Religion and Family in the Changing Social Order” address fundamental questions of the impact of the social order on Catholic, Jewish, Mormon, Protestant, and Amish families and raise questions about reciprocal influence discussed in Thornton’s chapter. Hynes’s chapter on Ireland adds a historical dimension to the issues of religion, family, and social change. The chapters in the socialization section, along with Stack’s chapter on suicide, increase our understanding of the social-psychological dimensions inherent in religion and family studies as well as the impact of both religion and family upon the child in those families.

With more studies linking parental religious belief systems to child-rearing attitudes and behavior, such as Clayton’s chapter and research reported by Barber and Thomas (1986a and b), we may begin to understand better the impact of an individual’s religious orientation on socialization practices. This is a much-neglected area of study. The chapters by McNamara and Schroll make important contributions to our understanding of how presuppositions in the scientific process are related to both the nature of the questions we ask and the answers that are suggested by the particular approaches we use. The chapters by Spickard and Helle illustrate how different perspectives lead to very different typological systems of families and religions.

One additional payoff needs to be added to the above list. We believe that studies of religion and family will make important contributions to our understanding of the human conditions by generating more comparative studies of religion and family. We along with others (Bahr and Forste, 1986a and b; Alston, 1986; D’Antonio and Aldous, 1983) see the need for comparative studies. The best comparative studies will be done when we have sufficient information about the religion and family connection within each religious orientation to make and test theoretical formulations about how religion and family influence each other.

Thus, our plea for future studies is that they carefully document the important relationships between religion and family within one religious denomination and then carefully assess the degree to which those relationships hold or are modified across religions. For example, Scanzoni, in her discussion of the religion and family connection from a Protestant woman’s point of view, discusses gender roles. The Mormon teachings and doctrines about marriage and family life may be unique in the Christian tradition (Marciano, 1987: 306). How much does the unusual Mormon theology influence what occurs in the family along gender role lines? Heaton believes that Mormons are different from other religious groups in the emphasis given to the father’s authority, but his evidence is sketchy at best. There is clearly room for alternative interpretations of the effect of Mormon teachings on gender roles (Thomas, 1983; Smith, 1986). Even Heaton’s discussion raises the possibility that Mormonism, if it is taken to be the nearest thing to an ideal type as Marciano (1987) has argued, has countervailing influences.

For Mormons who participate in temple marriage, certain blessings in this life and the world to come are promised to the husband and wife unit, rather than to either singly. In addition, Mormon fathers are encouraged not only to have large families but also to be involved in the lives of their children. For instance, in large Mormon families there is an increase in affection whereas in other families there is a decline in affection as family size increases (Wilkinson and Tanner, 1980). Thus, we need better information about what is happening within Mormon families and how the countervailing influences of emphasizing father’s authority gets played out among religious teachings which also encourage increased involvement in the lives of family members. Once we know that, we could then compare those relationships in families from other churches. We would then be closer to understanding religion’s impact of gender roles both in and out of the family.

Fertility is the second example of comparative studies adding to our understanding. As Brodbar-Nemzer’s discussion indicates, fertility has become a significant concern in the contemporary American Jewish family. The consistent fertility decline in American Jewish families has raised discussion about having enough children to maintain present population levels. When this pattern is contrasted with fertility for the Mormon family, it becomes readily apparent that the two religious traditions are very different even though they are similar on many family characteristics. Both value children and place a high premium on family life. Mormons have maintained a significantly higher fertility rate than the society within which it is imbedded. Why? Heaton believes that the Mormon case illustrates how religious teachings influence fertility patterns (Heaton, 1988). Are there specific aspects of Jewish theology that encourage Jewish parents to have few children, or is the Jewish fertility pattern at base influenced by secular forces?

Careful studies of belief structures, particularly about the meaning of this world’s existence as well as postmortal expectations, would need to be effectively carried out in order to understand these very different patterns and the religion and family influences. Once careful studies comparing Mormons and Jews were carried out, other significant religious groups such as the Catholics could also be studied. Heaton implies that there is a difference between religions which emphasize the value of children by valuing and encouraging the advent of children as contrasted with a religion which influences fertility by disapproving of contraceptive use, such as the Catholic church. While such speculations might make sense, we obviously need careful social-psychological studies to know how meaning systems interface with fertility decisions.

Aside from the above substantive-oriented issues that comparative studies of religion and family could illuminate, there is one additional potential payoff. This is the issue raised by McNamara and Schroll in their chapters, in which they discuss the role of presuppositions in a scientist’s work. Schroll convincingly makes the case that developments in physical sciences have implications for social science endeavor. McNamara argues convincingly that the presuppositions which guide a particular social scientist’s analysis will influence not only the kinds of questions that are asked but also the answers that are generated from the research evidence.

We are convinced that not only comparative studies are needed but comparative studies done by both insiders and outsiders, since the presuppositions they bring to their work will likely differ. As Alston (1986), an outside observer of Mormonism, notes, work done by “professional anti-Mormons make [him] nervous.” He is also made nervous, but to a lesser extent, by the religious “specialist.” If Alston is nervous over work done by both of those groups, one wonders what type of researcher would not make Alston nervous. We assume that in Alston’s scheme of things there is an unnamed third group that he sees as more “objective” than either “professional anti” or the “specialist.” We are not convinced that degrees of objectivity will necessarily generate solutions, given our view of the nature of scientific inquiry. Our position is simply that work needs to be done by both insiders and outsiders and that the consumers of the research have the right to know which group is represented.

We have previously argued that the social sciences ought to reject the methodological pretense of objectivity (Thomas and Sommerfeldt, 1984; Thomas and Wilcox, 1987). Social scientists in general, we believe, recognize that their own presuppositional system influences both the questions asked and answers suggested (McNamara, 1985). The postpositivist position, which emphasizes the constructed and social consensual nature of human knowledge and was first developed in the physical sciences (Thomas and Wilcox, 1987; Schroll 1988), rejects the notion that it is even possible to describe in an objective fashion the world that is taken to exist independent of the observer. Thus, the analysts need to identify their own presuppositions, especially as they relate to religious belief and commitment, since that is the very institution that is coming under their scrutiny. This would allow the reader to judge the adequacy of the information presented. McNamara’s (1985, 1986; Goettch, 1986) discussion of the consequences of differing presuppositions of insiders’ and outsiders’ analyses of conservative Christian churches is a persuasive example of the need to address presuppositional influence in scientific discourse.

Mormon Case

As indicated above, we believe research encouraged and funded by religious organizations will continue to make an important contribution in the area where research in general is “underfunded and understaffed” (Alston, 1986: 123). The research discussed below is presented with the intent of illustrating the contributions that such research can make in four of the above listed areas of potential payoff; namely, social change, well-being, social-psychological studies, and spiritual influences. While the research is not comparative by nature, it is a necessary first step in attempting to clarify the nature of the religion and family interface within one denomination. Once this connection is understood, comparative research could be undertaken to determine to what degree the relationships discussed in this research hold for other denominations.

In the spirit of identifying presuppositions, we note that this research, conducted by Mormons for the Mormon church, was conceived, designed, and carried out by insiders. The advantages are that the researchers have greater insight into those social-psychological realities of meaning, intention, and personal belief that tend to be underemphasized or ignored by outsiders (McNamara, 1985). This is significant, since the Mormon teachings about religion and family are the nearest thing to a unique set of teachings in Christendom (Marciano, 1987). By the same token, we recognize that outsiders may see a different set of meanings and relationships in the data discussed here. The competition between alternative explanations is all a necessary part of scientific inquiry.

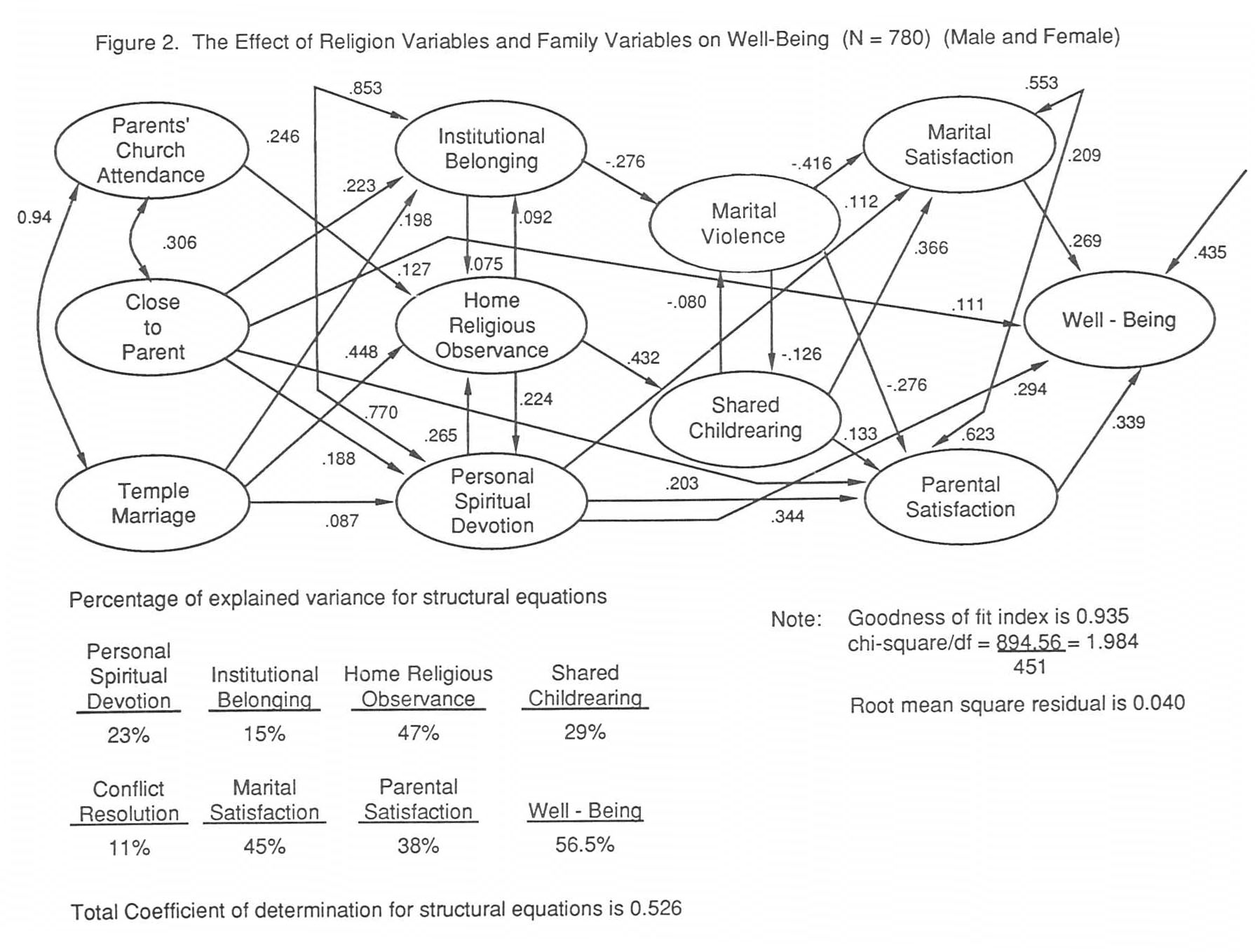

The Study. Questionnaire data was collected in 1985 from a sample of age 18 years and older men and women of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints residing in the continental United States. The response rate of 57 percent produced usable data from a sample of 1100 females and 996 males. The questionnaire gathered considerable information on the religious life and practice of the people as well as information about family composition and practices. The analysis reported here comes from a subsample (780) of those respondents who had been married and had children old enough to enable them to answer the questions in the questionnaire detailing child-rearing attitudes and behavior. The Appendix lists the items used to measure the variables included in the LISREL [2] model depicted in Figure 2.

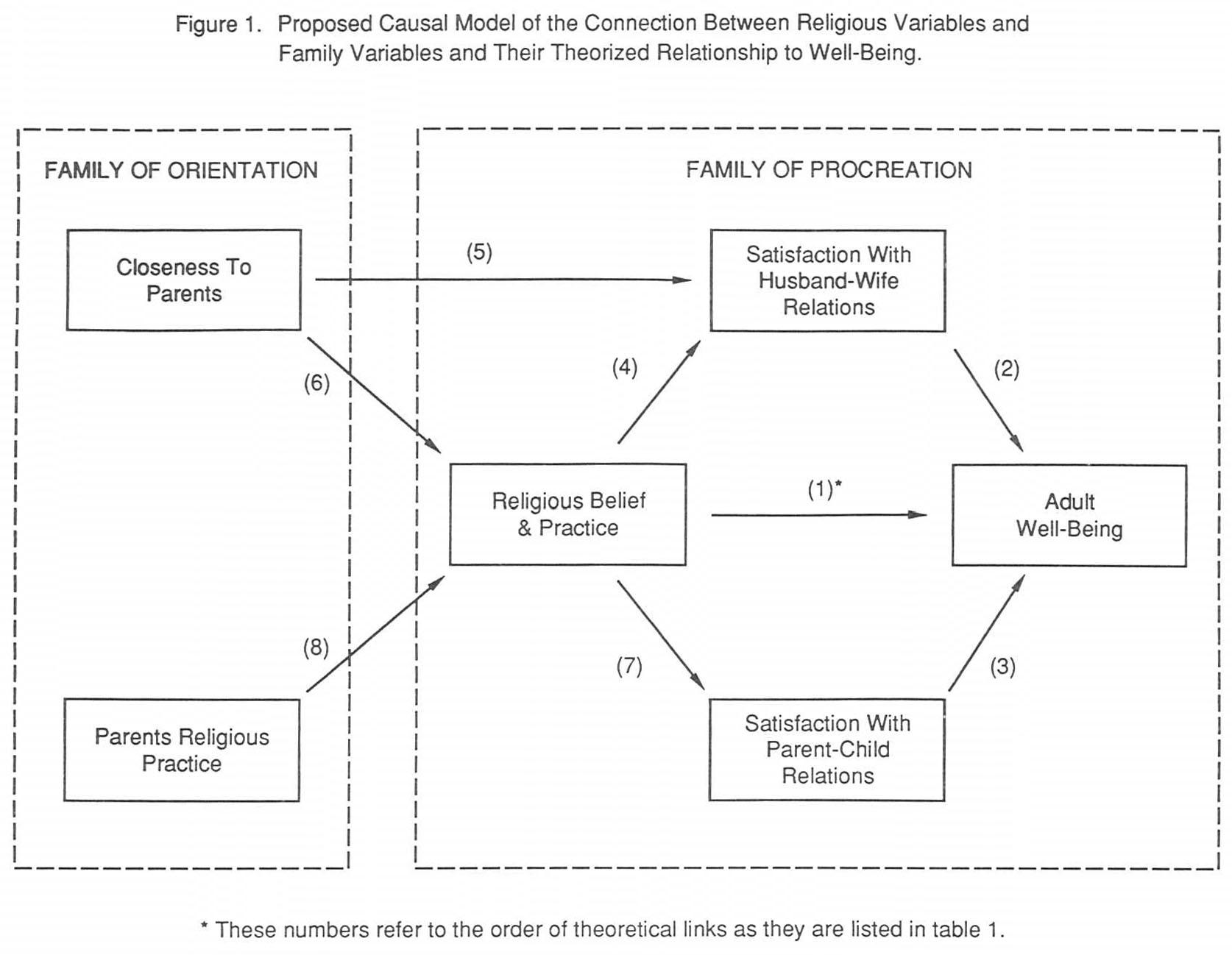

Theoretical Model. Figure 1 presents the theoretical model that was developed from a review of literature. We cannot present in detail the research and theory base underlying this theoretical model. We can, however, for the interested reader, identify the literature that allows us to make each of the links in the model. Each propositional link appearing in the model has a number identifying that link, and Table 1 presents a list of the studies from which each link was derived.

The general theoretical orientation depicted in Figure 1 argues that some characteristics of the family of orientation will influence both the religious and the family characteristics in the family of procreation. The family of orientation variables are closeness to parents and parents’ religious practice. As can be seen in Figure 1, closeness to parents is theorized as influencing both marital satisfaction and one’s religious belief and practice. Parents’ religious practices are seen as influencing the adult religious belief and practice, but there is no body of literature or well-developed theory which indicates that parents’ religious practice would influence either marital satisfaction or satisfaction with parenting. Note also that the theory argues that there is no direct effect of these family-of-orientation variables upon adult well-being. The effect of the closeness-to-parent variable is seen as being mediated through both the religious belief and practice and the satisfaction with the husband/

The theoretical formulation argues that religious belief and practices are best conceived as antecedent in their effect upon satisfaction with the husband/

Table 1. Research and Theory Sources Used in Deriving the Theoretical Links in the Proposed Model (Figure 1) of Religion and Family Influences on Adult Well-Being

| Theoretical Link | Sources |

| 1. Religious Belief and Practice on Well-being | Thomas and Henry, 1985; Bergin, 1980; Stack, 1985; Aldous, 1985; Thomas and Kent, 1985; Durkheim, 1915; Erikson, 1969 |

| 2. Marital Satisfaction on Well-being | Bateson and Ventis, 1982; Bergin, 1980, 1983; Stark, 1971; Stack, 1985; Thomas and Henry, 1985; Judd, 1985; Brown and Harris, 1978; Pearlin and Johnson, 1977; Kessler and Essex, 1982 |

| 3. Parental Satisfaction on Well-being | Durkheim, 1915 |

| 4. Religious Belief and Practice on Marital Satisfaction | Durkheim, 1915; Babchuk, et al., 1967; Shrum, 1980; Hartley, 1987; Hunt and King, 1978; Kunz and Albrecht, 1977; Schumm, et al., 1982; Filsinger and Wilson, 1984 |

| 5. Closeness to Parents on Marital Satisfaction | Locke, 1947; Burgess and Wallen, 1953; Stryker, 1964; Dean, 1966; Lewis and Spanier, 1979 |

| 6. Closeness to Parents on Religious Belief and Practice | Dudley, 1978; Hoge and Petrillo, 1978; Hoge, Petrillo, and Smith, 1982; LoSciuto and Karlin, 1972; Clark and Worthington, 1987; Chartier and Gobner, 1976; Pearlin and Johnson, 1977; Wilkinson and Tanner, 1980; Landis, 1960; Wigert and Thomas, 1979; Thomas, Gecas, Weigert, and Rooney, 1974; Thomas, Weigert, and Winston, 1984; Barber and Thomas, 1987a and b |

| 7. Religious Belief and Practice on Parental Satisfaction | Clark and Worthington, 1987; Glass, Bengston, and Dunham, 1986; Vinovskis, 1987; Slater, 1977; Stannard, 1975; Clayton, 1988 |

| 8. Parents' Religious Practice on Religious Belief and Practice | Acock, 1984; Weiting, 1975; Hoge, et al., 1982; Glass, Bengston and Dunham, 1986; Greenley and Rossi, 1966; Himmelfarb, 1977, 1979; Cornwall 1988 |

The variables closest to adult well-being both spatially and temporally are marital and parental satisfaction. There is a clear body of literature which makes apparent that satisfaction with husband/

Each of the variables in the model is best conceptualized as a block of variables, and the purpose of this analysis was to include enough information about the respondents’ religious and family life that important dimensions within each of these blocks of variables could be measured and analyzed.

The literature on which this general model is based is general social science literature, and only a few of the cited studies report data from Mormon respondents. Thus, we are not sure to what degree this theoretical model will or will not be confirmed in the data for Mormons. That is the central purpose of the particular analysis reported here.

Findings. Figure 2 presents a test of the model using LISREL analysis. The standardized coefficients are reported here such that the size of the coefficients can be compared one with another. Since this is a causal model, the larger the coefficient on any one of the arrows indicates a greater amount of influence that that particular variable has on other variables in the model. The overall fit of the model is fairly good. The Goodness of Fit Index of .93 and the root mean square residual of .04 are well within the suggested limits for models of this type. Also, this model explains a sizeable proportion of variation in the measures of well-being (57 %).

While the overall fit of the model to the data is good, a number of very important and surprising findings emerge in this analysis. First, it confirms some of the general theoretical propositions outlined at the beginning. The experiences in the family of orientation (closeness to parents and parents’ religious attendance) are related to measures of religiosity and dimensions of family functioning (marital and parental satisfaction) as well as adult well-being. The closeness to parent variable is considerably more important than is parents’ religious attendance in accounting for variation in the model. Second, as was theorized, dimensions of religiosity are best conceptualized as antecedent variables to marital and parental relationships. Of the two religiosity dimensions, personal spiritual devotion is significantly more important in terms of its effect on well-being as well as its effect on marital and parental satisfaction.

When we computed the total effect for each of the variables on well-being, personal spiritual devotion emerged as the single most important influence on adult well-being. This is a positive relationship, meaning that the higher the individual scores on the measure of personal spiritual devotion the higher the well-being. It has a sizeable direct effect on well-being but it also has one strong indirect effect through parental satisfaction to well-being and the other weaker one through marital satisfaction to well-being. Thus, our second finding is that personal spiritual devotion is very important for Mormon well-being. This finding argues persuasively for the conceptualization that religious commitment is positively related to well-being. This is currently being debated in the social science literature (Bergin, 1980; Stack, 1985; Thomas and Henry, 1985). The data argue convincingly that for Mormons, personal well-being is very much influenced by an individual’s attempts to live a Christlike life, seek the influence of the Holy Ghost, and be forgiven.

The third most important finding from this research is the significant influence of parental satisfaction upon well-being. This was not anticipated as the original model was developed. As was indicated, there was no well-established body of research literature which indicated that parental satisfaction would be strongly related to well-being. The connection was made on the basis of theoretical formulations developed by Durkheim years ago as he tried to understand the religious institution. In Durkheim’s formulations, integration into dominant social spheres, be they religion or family, equipped an individual to live better. In Durkheim’s words, the religiously integrated individual is a person “who is stronger” (italics in the original, Durkheim, 1915: 464).

It is important to realize that these data say that satisfaction with one’s parental experiences in the family has a very strong and independent effect upon well-being, both independent from the effects that other religious variables have on well-being and independent from the effect that satisfaction with the conjugal relationship has on well-being. To our knowledge this is the first research to identify clearly the independent influence of parental satisfaction on well-being. This is a strong effect. The analyses indicates that parental satisfaction (.34) is second to personal spiritual devotion (.46) in the strength of its effects on personal well-being.

The fourth most important finding is the effect of closeness to parents in the family of orientation on well-being. After the effect of personal religious devotion and parental satisfaction on well being, the next single most important variable is closeness to parents (.33). While it only has a small direct effect (.11) on well-being, it influences virtually all of the other variables in the model, namely, the religiosity dimensions and marital and parental satisfaction. Thus, it can be seen as an important variable in understanding adult well-being among Mormons.

The last finding discussed is the importance of shared child-rearing for marital satisfaction and the relationship of shared child-rearing to home religious observance and temple marriage. The general theoretical formulation (Figure 1) was not specific enough to anticipate a number of the important relationships that emerged in the data between home religious observance, shared child-rearing, marital satisfaction, and temple marriage. The second most important variable in accounting for marital satisfaction among Mormons is the degree to which husband and wife share in the child-rearing duties and responsibilities. The single strongest influence on shared child-rearing is the degree to which Mormons engage in home religious observance, and the single most important influence on home religious observance is whether or not the husband and wife were married in a Mormon temple.

Our interpretation of these relationships is that, for Mormons who are married in the temple, (1) they are more likely to engage in home religious observance, (2) both husband and wife are more likely to share in child-rearing duties and responsibilities, and (3) they will in turn experience a greater amount of marital satisfaction. Shared child-rearing also influences parental satisfaction, but the influence is not nearly as strong as it is on marital satisfaction. The role of shared child-rearing in Mormon families adds important information and clarification to the whole discussion of gender roles (Heaton, 1988; Scanzoni, 1988; Brinkerhoff and MacKie, 1985).

As was indicated in the earlier discussion, Mormonism has traditionally been seen as a religion which emphasizes the authority of the father. However, these data allow us to specify what are the countervailing influences operating within the Mormon family. The influences from temple marriage and home religious observance lead to increased shared child-rearing roles. This more egalitarian participation in child-rearing in turn has a significant impact on marital satisfaction, which affects adult well-being.

These data clarify a trend noted by a number of researchers that when it comes to gender role ideology, Mormons emphasize both separation of roles and authority of the fathers, whereas when Mormons respond about who does what, they score relatively high on measures of egalitarian role performance (Heaton, 1988; Brinkerhoff and MacKie, 1985; Thomas, 1983; Bahr, 1982; Smith, 1986). These data now allow us to specify that, contrary to some proposed explanations which see the egalitarian role performance of Mormons as coming from larger societal influences on Mormon parents, these findings illustrate that some religious variables (temple marriage) and family religious activities (home religious observance) are important sources of egalitarian role behavior in the child-rearing domain. These patterns appear plausible when paired with Mormon theology which teaches that husbands and wives enter an order of the priesthood when they are married. All blessings are promised to the couple jointly, not singly. Parents together have mutual responsibility for teaching and caring for children born to that union. The family unit has an ontological reality that transcends mortal existence. (McConkie, 1964; Heaton, 1988; Thomas, 1983.) This theology apparently encourages shared child-rearing role performance, which impacts marital satisfaction and well-being.

Summary

This chapter began by arguing for the utility of more studies focusing on religion and family. A number of possible payoffs were identified and then data were presented from a study of Mormon adult men and women focusing on family and religious influences on their sense of well-being. The data illustrated the importance of measuring multiple dimensions of religious belief and practice as well as multiple dimensions of family functioning in order to see more clearly what is happening in Mormon families. In order to understand well-being among adult Mormon men and women, the impact of both religion and family must be analyzed.

The data underscore the very important role of personal spiritual devotion in the lives of these adult Mormons. The social sciences have tended to neglect this dimension in studies of religiosity, especially in studies that deal with religion and family. Recent observers have called for more studies of social-psychological dimensions of meaning, intentionality, or future expectational states in the study of religion and family (D’Antonio, Newman, and Wright, 1982; McNamara, 1985; Thomas and Henry, 1985). These findings corroborate that plea. One would have a hard time understanding what is occurring in Mormon families without establishing the degree to which men and women are committed to and attempt to seek spiritual guidance in their lives.

Mormon theology depicts Mormonism as a restoration of spiritual gifts existing in Christ’s church in his day. Ordinances are performed in which the Holy Ghost is conferred upon those who believe. Additional covenants are made by Mormons in church and temple ceremonies which underscore the importance of spiritual direction in daily living. These data indicate that this personal spiritual devotion is important for these Mormon respondents. The importance of personal spiritual devotion in these data corroborate Moberg’s (1979) early efforts to call attention to the study of the spiritual dimension in sociological studies of religion. Clearly, for these Mormon respondents, religion provides a significant source of meaning for not only their family relationships but also their own personal sense of well-being.

The final dominant impression coming from these Mormon data is the tremendous impact of parent-child relations for adult well-being. The feeling of closeness to parents in the family of orientation influences virtually all variables in the model. Satisfaction with parenthood is the single most important influence on well-being. Given these relationships, comparative research should now attempt to investigate the meaning of parent-child relations in other religions. Our own predictions lead us to believe that closeness to parents will show similar effects on the social and emotional well-being of adults for most religious groups. The nature of the human being and the socialization process lead us to this conclusion. We tend to see the strong relationships between parental satisfaction and well-being as perhaps more characteristic of Mormon families when compared to other religious groups. The distinctiveness of Mormon theology which ties conjugal to parental dimensions in the view of the human condition in this and the other world underlies our prediction that the link between parental satisfaction and well-being will be stronger for Mormons.

Our prediction of a stronger relationship is consistent with research in other areas. For example, Christensen (1962, 1976) concludes that the Mormon faith is more successful than other faiths in limiting premarital sexual activity. Smith (1976) shows that Mormon sexual attitudes remained relatively constant during the sexual revolution. Stott (1988) shows that the influence of parents on children is generally stronger for Mormons than for Baptists. Future comparative research will have to test the expectation that parental satisfaction is more strongly related to well-being for Mormons than it is for other denominations.

The major findings reported in this chapter have important implications for any attempt to understand the social-psychological dimensions of adult functioning in our contemporary society. The Mormon data confirm the wisdom of those social scientists who have repeatedly called for more social-psychological studies. Such studies will undoubtedly add to our understanding of religion and family influences in various analyses of social change. Those concerned about the contemporary adult’s feelings of well-being will need to include religion and family influences in their analysis to more correctly identify important sources of influence. Lastly, those who would analyze the religious connection to well-being cannot ignore the spiritual dimension of religious experience. This chapter, as well as this volume, argues convincingly that social scientists must focus on the religion and family interface if they wish to more fully understand the human condition. The best research and theory will be that which analyzes the two institutions simultaneously. The prospects for increased knowledge from future research are encouraging.

Appendix. List of Items Used to Measure Each Construct in the LISREL Model with Reliability Coefficients

Well-Being (alpha =.8166):

Life.suc: Life achievement perceived by respondent (alpha = .7211)

Q40. For each pair of opposites below, circle the ‘x’ on the scale that would be most really true for you (5 point scale).

1. I would like to live my life very differently vs. I would want to live it just the same.

2. Made no progress vs. progressed to complete fulfillment in achieving life goals.

3. If I should die today I would feel that my life has been completely worthless vs. very worthwhile.

Q42. For each pair of statements below, please circle the ‘x’ on the scale that is closest to your feelings (5 point scale).

5. I feel guilty all the time vs. I don’t feel particularly guilty.

N.depress: Beck’s depression scale (alpha = .8989)

Q40. For each pair of opposites below, circle the ‘x’ on the scale that would be most really true for you (5 point scale).

4. My life is filled with conflict and despair vs. filled with peace and joy.

5. My life is out of my hands and controlled by external factors vs. my life is in my hands and I am in control of it.

6. Facing my daily tasks is an unpleasant and boring experience vs. a source of pleasure and satisfaction.

7. In life I can see no meaning in the trials I experience vs. purpose and meaning in the trials I experience.

Q42. For each pair of statements below, please circle the ‘x’ on the scale that is closest to your feelings (5 point scale).

1. I do not feel sad vs. I am so sad or unhappy that I can’t stand it.

2. I feel that the future is hopeless and that things cannot improve vs; I am not particularly discouraged about the future.

3. I am dissatisfied or bored with everything vs. I get as much satisfaction out of things as I used to.

4. I am disgusted with myself vs. I do not feel disappointed with myself.

6. I feel guilty all the time vs. I do not have any thoughts of killing myself.

7. I can’t make decisions at all anymore vs. I make decisions about as well as I ever could.

8. I don’t get more tired than usual vs. I am too tired to do anything.

Marital Satisfaction: (alpha = .8849)

Mar.sat: Marital satisfaction (alpha = .9569)

Q22. All things considered, how would you describe your marriage? For each pair of opposites below, circle the ‘x’ that is closest to your feelings.

1. I feel distance between my spouse and me vs. I feel extremely close to my spouse.

2. I am very unhappy in my marriage vs. I am very happy in my marriage.

3. My marriage is less satisfying than most marriages vs. my marriage is more satisfying than most marriages.

4. If I had to do it over again, I would marry someone different vs. if I had to do it over again, I would marry the same person.

5. My spouse and I are just two people who live in the same house vs. my spouse and I are like a close knit team.

Problems: Marital Problems (alpha = .8546)

Q23. Even in cases where married people are mostly happy, they sometimes have problems getting along with each other. Please indicate to what degree the following are problems in your marriage. Respondent categories: (1) not a problem to (5) a major problem.

1. We do not spend enough time together as companions.

2. We do not agree on where to spend our money.

3. Marriage makes me feel trapped.

4. Our sexual relations are unsatisfying.

5. We disagree about child-rearing practices.

6. We don’t understand each other very well.

7. There isn’t enough romance in our marriage.

Parental Satisfaction (alpha = .7652):

Par.sat: Parenting Satisfaction (alpha = .8111)

Q26. Given the rewards and difficulties that one encounters in rearing children, how do you feel about your parenting experiences up to this point? Please indicate how well each of these statements describes your feelings.

1. I feel I have been a good parent.

2. In general I would say that the work involved in rearing children is more satisfying than working in a job.

3. I have often felt guilty about the way I fulfill my role as a parent.

4. My experience in rearing children has been very frustrating.

5. I feel I am capable of dealing with the challenges parents have to face in today’s world.

6. The demands of being a parent have often been so overwhelming that I have wished for a way out.

7. For me, rearing children has been an exciting and growing experience.

Harmony: Harmony in family (alpha = .8709)

Q25. To what extent do the following things occur in your family, that is, with you, your children, and spouse (if married)? If your children are no longer at home, respond to these statements for the time when your children were at home. Respondent categories: (1) to a very little extent to (5) to a very great extent.

1. Family members help and support one another.

2. The children respect me.

3. We fight in our family.

4. Family members lose their tempers.

5. We really get along well with each other.

6. There is a feeling of togetherness in our family.

7. Family members criticize each other.

8. The children and I have quality time together.

9. The children are responsible and independent.

Marital Violence (alpha = .7837):

Q24. No matter how well married couples get along they sometimes have disagreements, get annoyed at each other, or just have spats or fights. This may be due to stress, tiredness, or other reasons. They also use many different ways of trying to settle their differences. These may include some of the things listed below. How often has your spouse done any of the following during the past year?

4. Insulted you or swore at you?

5. Stomped out of the room or house or yard?

6. Threw, smashed, hit, or kicked something?

7. Pushed, grabbed, or shoved you?

8. Kicked, bit, or hit you?

Shared Child-rearing (alpha =. 6855):

Q28. The activities listed below take place in different amounts in different families. When the activities have occurred in your family, which parent is (or was) more involved? (Mostly mother or mostly father = 1; mother more or father more = 2; mother and father about the same = 3.)

3. Having informal discussions with your children about gospel principles.

5. Planning and holding a family night with your children.

8. Helping children to read and do well in school.

9. Disciplining children when necessary.

10. Seeing that children’s chores and duties are assigned and completed.

Institutional Belonging (alpha = .7876):

Q20. Sometimes members feel they do not fit the church picture of the ideal LDS family. Some may not be married, some may not have children, some may have a spouse who is not LDS or not active, etc. Whatever your family situation may be, please indicate how often the following situations have occurred in your experience in the church. Respondent categories: (1) rarely or never to (5) very often.

2. I have found the people in my ward or branch ready and willing to make friends with me.

4. I have NOT felt left out of some ward or branch social activities.

5. I have felt that some church leaders and members really seem to understand my situation.

8. I have felt that some people think there is something wrong with me.

Home Religious Observance (alpha = .7330):

Famscrip. How frequently in the past six months have you had family scripture study? Respondent categories: (1) not at all to (5) about daily. (Recoded from q38.4.)

Fampray. How frequently in the past six months have you had family prayer together? Respondent categories: (1) not at all to (5) about daily. (Recoded from q38.2.)

Q38.7 How frequently in the past six months has your family held or attended family home evening? Respondent categories: (1) not at all to (5) about once a week.

Personal Spiritual Devotion (alpha = .8939):

Q36. How often do the following statements describe your personal experiences, feelings, and beliefs? Respondent categories: (1) Doesn’t describe me at all to (7) describes me very well.

5. I work very hard at seeking forgiveness and overcoming my weaknesses.

6. In my life, seeking spiritual goals always comes first.

7. I am strongly committed to being like Christ.

9. I frequently feel prompted by the Holy Ghost.

10. I always seek God’s guidance when I have important decisions to make.

Parents’ Church Attendance (alpha =. 7912):

Q48.1 How often did your father attend religious services when you were a child? Respondent categories: (1) rarely or never to (5) once a week.

Q48.2 How often did your mother attend religious services when you were a child? Respondent categories: (1) rarely or never to (5) once a week.

Close to Parents (alpha =.5954):

Q49.1 How close did you feel towards your father (or male guardian) when you were growing up? Respondent categories: (1) not at all close to (5) extremely close.

Q49.2 How close did you feel towards your mother (or female guardian) when you were growing up? Respondent categories: (1) not at all close to (5) extremely close.

Temple Marriage:

Temple It’s a dummy variable where 0 = is not married in temple and 1 = married in temple.

Bibliography

Abrahamson, M., and W. P. Anderson. 1984. “People’s Commitments to Institutions.” Social Psychology Quarterly 47(4): 371–81.

Acock. A. C. 1984. “Parents and Their Children: The Study of Inter-generation Influence.” Sociology and Social Research 68: 151–71.

Aldous, J. 1985. “Theoretical Perspectives on the Religion and Family Connection with Personal Well-being.” Paper presented at the Theory Development Workshop, National Council on Family Relations annual meeting.

Alston, J. P. 1986. “A Response to Bahr and Forste.” Brigham Young University Studies 26(l): 123–26.

Babchuk, N., H. J. Crockett, and J. A. Ballweg. 1967. “Change in Religious Affiliation and Family Stability.” Social Forces 45: 551–55.

Bahr, H. M. 1982. “Religious Contrasts in Family Roles.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 21: 201–17.

Bahr, H. M., and R. T. Forste. 1986a. “Toward a Social Science of Contemporary Mormondom.” Brigham Young University Studies 26(1): 73–121.

Bahr, H. M., and R. T. Forste. 1986b. “Reply to Alston.” Brigham Young University Studies 26(l): 127–29.

Bahr, H. M., and B. Chadwick. 1985. “Religion and Family in Middletown, USA.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 47(May): 407–14.

Barber, B. K., and D. L. Thomas. 1986a. “Dimensions of Adolescent Self-esteem and Religious Self-evaluations.” Family Perspective 20(2): 137–50.

Barber, B. K. andD. L. Thomas. 1986b. “Dimensions of Fathers’ and Mothers’ Supportive Behavior: The Case for Physical Affection.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 48(3): 783–94

Batson, C. D., and W. L. Ventis. 1982. The Religious Experience: A Social-Psychological Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press.

Beit-Hallahmi, B. 1974. “Psychology of Religion in 1880–1930: The Rise and Fall of a Psychological Movement.” Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences 10: 84–94.

Bergin. A. E. 1980. “Psychotherapy and Religious Values.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 48(1): 95–105.

Bergin, A. E. 1983. “Religiosity and Mental Health: A Critical Re-evaluation and Meta-analysis.” Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 14(2): 170–84.

Brinkerhoff, M. B., and M. MacKie. 1988. “Religious Sources of Gender Traditionalism.” The Religion and Family Connection: Social Science Perspectives. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University.

Brodbar-Nemzer, J. 1988. “The Contemporary American Jewish Family.” In D. L. Thomas (ed.), The Religion and Family Connection: Social Science Perspectives. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University.

Brown, G. W., and T. Harris. 1978. Social Origins of Depression: A Study of Psychiatric Disorder in Women. New York: Free Press.

Burgess, E. W., and P. Wallin. 1953. Engagement and Marriage. Chicago: J. B. Lippincott.

Chartier, M. R., and L. A. Goehner. 1976. “A Study of the Relationship of Parent-Adolescent Communication, Self-esteem and God Image.” Journal of Psychology and Theology 4: 227–32.

Christensen, H. T. 1962. “A Cross-cultural Comparison of Attitudes Toward Marital Infidelity.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 3: 124–37.

Christensen, H. T. 1976. “Mormon Sexuality in Cross-cultural Perspective.” Dialogue 10(2): 62–75.

Clark, C. A., and E. L. Worthington, Jr. 1987. “Family Variables Affecting the Transmission of Religious Values from Parents to Adolescents: A Review.” Family Perspective 21(1): 1–22.

Clayton, L. 1988. “The Impact of Parental Views of the Nature of Humankind upon Child-rearing Attitudes.” In D. L. Thomas (ed.), The Religion and Family Connection: Social Science Perspectives. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University.

Cornwall, M. 1988. “The Influence of Three Agents of Religious Socialization: Family, Church, and Peers.” In D. L. Thomas (ed.), The Religion and Family Connection: Social Science Perspectives. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University.

D’Antonio, W. V., and J. Aldous. 1983- Families and Religions: Conflict and Change in Modern Society. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

D’Antonio, W. V., W. M. Newman and S. A. Wright. 1982. “Religion and Family Life: How Social Scientists View the Relationship.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 21(3): 218–25.

Dean D. 1966. “Emotional Maturity and Marital Adjustment.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 28: 454–57.

Dudley, R. L. 1978. “Alienation from Religion in Adolescents from Fundamentalist Religious Homes.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 17: 389–98.

Durkheim, E. 1915. The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life. Translated by Joseph Ward Swain. New York: Free Press.

Erikson, E. H. 1969. Gandhi’s Truth. New York: W. W. Norton.

Filsinger, E. E., and M. R. Wilson. 1984. “Religiosity, Socioeconomic Rewards, and Family Development: Predictors of Marital Adjustment.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 46(3): 663–70.

Glass, J., V. L., Bengston, and C. C. Dunham. 1986. “Attitude Similarity in Three-generation Families; Socialization, Status Inheritance or Reciprocal Influence?” American Sociological Review 51(5): 685–98.

Goettsch, S. L. 1986. “The New Christian Right and the Social Sciences: A Response to McNamara.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 48: 447–54.

Greeley, A. M., and P. Rossi. 1966. The Education of Catholic Americans. Chicago: Aldine.

Hadden, J. K., and A. Shupe (eds.). 1986. Prophetic Religions and Politics: Religion and the Political Order. New York: Paragon House.

Hartley, S. F. 1978. “Marital Satisfaction Among Clergy Wives.” Review of Religious Research 19: 178–91.

Heaton, T. B. 1988. “Four C’s of the Mormon Family: Chastity, Conjugality, Children, and Chauvinism.” In D. L. Thomas (ed.), The Religion and Family Connection: Social Science Perspectives. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University.

Helle, H. J. 1988. “Types of Religious Values and Family Cultures.” In D. L. Thomas (ed.), The Religion and Family Connection: Social Science Perspectives. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University.

Himmelfarb, H. S. 1977. “The Interaction Effects of Parents, Spouse, and Schooling: Comparing the Impact of Jewish and Catholic Schools.” Sociological Quarterly 18: 464–71.

Himmelfarb, H. S. 1979. “Agents of Religious Socialization Among American Jews.” Sociological Quarterly 20: 447–94.

Hoge, D. R., G. Petrillo, and E. Smith. 1982. “Transmission of Religious and Social Values from Parents to Teenage Children.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 44: 569–80.

Hoge, D. R., and D. A. Roozen. 1979. Understanding Church Growth and Decline, 1950–1978. New York: The Pilgrim Press.

Hoge, D. R., and G. H. Petrillo. 1978. “Determinants of Church Participation and Attitudes Among High School Youth.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 17: 359–79.

Hout, M., and A. M. Greeley. 1987. “The Center Doesn’t Hold: Church Attendance in the United States.” American Sociological Review 52(June): 325–45.

Howery, C. B. 1986. “Researching the Church from Within.” Footnotes 14(19): 7.

Hunt, R. A., and M. B. King. 1978. “Religiosity and Marriage. “Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 17: 339–406.

Hynes, E. 1988. “Family and Religious Change in a Peripheral Capitalist Society: Mid-nineteenth-century Ireland.” In D. L. Thomas (ed.), The Religion and Family Connection: Social Science Perspectives. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University.

Judd, D. K. 1985. “Religiosity and Mental Health.” Unpublished master’s thesis, Brigham Young University.

Kessler, R. C., and M. Essex. 1982. “Marital Status and Depression: The Importance of Coping Resources.” Social Forces 6l(2): 485–507.

Kunz, P. R., and S. L. Albrecht. 1977. “Religion, Marital Happiness and Divorce.” International Journal of Sociology of the Family 7: 227–32.

Landis, J. T. I960. “Religiousness, Family Relationships, and Family Values in Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish Families.” Marriage and Family Living 22: 341–47.

Lewis, R. A., and G. B. Spanier. 1979. “Theorizing About the Quality and Stability of Marriage.” Pp. 268–94 in W. R. Burr, R. Hill, F. I. Nye, and I. L. Reiss (eds.), Contemporary Theories about the Family (Vol. 1). New York: Free Press.

Locke, H. J. 1947. “Predicting Marital Adjustment by Comparing a Divorced and Happily Married Group.” American Sociological Review 12: 187–91.

LoSciuto, L. A., and R. M. Karlin. 1972. “Correlates of the Generation Gap.” The Journal of Psychology 81: 253–62.

Marciano, T. D. 1987. “Families and Religions.” Pp. 285–315 in M. B. Sussman and S. K. Steinmetz (eds.), Handbook of Marriage and the Family. New York: Plenum Press.

McConkie, B. R. 1967. “The Eternal Family Concept.” Devotional address given at the Second Annual Priesthood Genealogical Research Seminar, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, June 23.

McNamara, P. H. 1985. “The New Christian Right’s View of the Family and Its Social Science Critics: A Study in Differing Presuppositions.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 47(May): 449–58.

McNamara, P. H. 1986. “A Reply to Goettsch. “Journal of Marriage and the Family 48: 453–54.

Meyer, A. 1987. “Copykids.” Mature Outlook 4(3): 29–37.

Moberg, D. O. (ed.). 1979. Spiritual Well-being: Sociological Perspectives. Washington, D.C.: University Press of America.

Olshan, M. A. 1988. “Family Life: An Old Order Amish Manifesto.” In D. L. Thomas (ed.), The Religion and Family Connection: Social Science Perspectives. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University.

Pearlin, L. I., and J. S. Johnson. 1977. “Marital Status, Life-Strains and Depression.” American Sociological Review 42: 704–15.

Roberts, K. A. 1984. Religion in Sociological Perspectives. Homewood, IL: The Dorsey Press.

Scanzoni, L. D. 1988. “Contemporary Challenges for Religion and the Family from a Protestant Woman’s Point of View.” In D. L. Thomas (ed.), The Religion and Family Connection: Social Science Perspectives. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University.

Schroll, M. A. 1988. “Developments in Modern Physics and Their Implications for the Social and Behavioral Sciences.” In D. L. Thomas (ed.), The Religion and Family Connection: Social Science Perspectives. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University.

Schumm, W. R., S. R. Bollman, and A. P. Jurich. 1982. “The ‘Marital Conventionalization’ Argument: Implications for the Study of Religiosity and Marital Satisfaction.” Journal of Psychology and Theology 10: 236–41.

Shrum, W. 1980. “Religious and Marital Instability: Change in the 1970’s?” Review of Religious Research 21: 135–47.

Slater, P. G. 1977. Children in the New England Mind: In Death and in Life. Hamden, CT: Archon Books.

Smith, J. E. 1986. “A Familistic Religion in a Modern Society.” Pp. 273–97 in Kingsley Davis (ed.), Contemporary Marriage. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Smith, W. E. 1976. “Mormon Sex Standards on College Campuses, or Deal Us Out of the Sexual Revolution!” Dialogue 10(2): 76–81.

Spickard, J. 1988. “Families and Religions: An Anthropological Typology.” In D. L. Thomas (ed.), The Religion and Family Connection. Social Science Perspectives. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University.

Stack, S. 1985. “The Effect of Domestic Religious Individualism on Suicide, 1954–1978.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 47(May): 431–47.

Stannard, D. E. 1975. “Death and Puritan Child.” Pp. 9–29 in D. E. Stannard (ed.), Death in America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Stark, R. 1971. “Psychopathology and Religious Commitment.” Review of Religious Research 12(3): l65–76.

Stott, G. 1988. “Familial Influence on Religious Involvement.” In D. L. Thomas (ed.), The Religion and Family Connection: Social Science Perspectives. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University.

Stryker, S. 1964. “The Interactional and Situational Approaches.” In H. T. Christensen (ed.), Handbook of Marriage and the Family. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Thomas, D. L. 1983. “Family in the Mormon Experience.” Chapter 11 in W. V. D’Antonio and J. Aldous (eds.), Families and Religions: Conflict and Change in Modern Society. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Thomas, D. L., and J. E. Wilcox. 1987. “The Rise of Family Theory: An Historical and Critical Analysis.” Pp. 81–102 in M. B. Sussman and S. K. Steinmetz (eds.), Handbook of Marriage and the Family. New York: Plenum Press.

Thomas, D. L., and R. Kent. 1985. “Theoretical Perspectives on the Religion and Family Connection with Personal Weil-Being.” Paper presented at the Theory Construction Workshop, National Council on Family Relations annual meetings, Dallas, Texas, November 4–5.

Thomas, D. L., and G. C. Henry. 1985. “The Religion and Family Connection: Increasing Dialogue in the Social Sciences.” Journal of Marriage and the Family (May): 369–79.

Thomas, D. L., and V. Sommerfeldt. 1984. “Religion, Family, and the Social Sciences: A Time for Dialogue.” Family Perspective 18: 117–25.

Thomas, D. L , A. J. Weigert, and N. Winston. 1984. “Adolescent Identification with Father and Mother: A Multinational Study.” Acta Paedologica 1:47–68.

Thomas, D. L, V. Gecas, A. Weigert, and E. Rooney. 1974. Family Socialization and the Adolescent. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Thornton, A. 1985. “Reciprocal Influences of Family and Religion in a Changing World.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 47 (May): 381–94.

Vinovskis, M. A. 1987. “Historical Perspectives on the Development of the Family and Parent- Child Interactions.” Pp. 295–312 in J. B. Lancaster, J. Altmann, A. S. Rossi, and L. R. Sherrod (eds.), Parenting Across the Life Span. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Weed, S. L., and D. Anderson. Forthcoming. “Applied Research in Religious Institutions: 1987 in Review.” Journal of Religious Research.

Weigert, A. J., and D. L. Thomas. 1979- “Family Socialization and Adolescent Conformity and Religiosity: An Extension to Germany and Spain. “Journal of Comparative Family Studies 10(3): 371–83.

Weiting, S. G. 1975. “An Examination of the Intergenerational Patterns of Religious Belief and Practice.” Sociological Analysis 36: 137–49.

Wilkinson, M. L., and W. C. Tanner III. 1980. “The Influence of Family Size Interaction, and Religiosity on Family Affection in a Mormon Sample.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 42(2): 297–304.

Notes

[1] Mormon is a nickname commonly used to refer to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

[2] LISREL is a general computer program designed to analyze the linear structural relations existing in a set of data. It allows the researcher to test both the adequacy of the measurement model and the theoretical model (the set of structural equations representing the theorized relations among variables) in causal analysis.