The Effect of Domestic/Religious Individualism on Suicide

Steven Stack

Steven Stack, “The Effect of Domestic/Religious Individualism on Suicide,” in The Religion and Family Connection: Social Science Perspectives, ed. Darwin L. Thomas (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1988), 175–204.

Steven Stack was an associate professor of sociology at Auburn University, Alabama, when this was published. Professor Stack’s research has focused on suicide as it is influenced by social integration. His numerous publications have established him as one of the leading experts in the study of suicide from a Durkheimian perspective. He received his PhD from the University of Connecticut.

Introduction

One method for relating the institutions of marriage/

The present paper’s purpose is to gauge the effect of the fall in collectivistic values in the domestic/

Religion and Suicide

The relationship between religion and suicide has been approached through at least two theoretical perspectives. First, there is the position that links the rise of individualistic culture to the decay in the general social fabric including religion, and such decay to problems of suicidal behavior (Durkheim, 1966; Halbwachs, 1978; Morselli, 1882; Masaryk, 1970). Second, there is the perspective that links specific qualities of religion to a lower propensity towards suicide (Stack, 1983b; Stark et al., 1983). In the former school a decline in religion is viewed as a consequence of a more general rise in self-interest, a force that makes life less meaningful and thereby promotes suicide. In the second school religion is taken out of this greater macrosociological perspective and is dealt with cross-sectionally without much reference to historical trends.

Probably most of the sociological work on the effect of religion on suicide has drawn on Durkheim’s (1966: 152–70) concept of religious integration (Stack, 1982: 55–56). Durkheim asserted that integration depends on the subordination of an individual’s interests to those of a group. An integrated society is one in which the culture of collectivism predominates over that of individualism. (Durkheim, 1966: 209–16.) Durkheim maintained that personal well-being and happiness were a function of the individual’s subordination to collective life. Such subordination is viewed in positive terms, as giving the individual a sense of purpose and making people think more about the trouble of others as opposed to dwelling on their own personal woes. (Durkheim, 1966: 209–10.) Durkheim contended that a religion would decrease suicide in proportion to the sheer number of shared beliefs and practices in the religion. For this reason he argued that Catholics had a lower suicide rate than Protestants.

Other writers link religion to suicide through particular beliefs, practices, and other characteristics of religion. While Durkheim argued that the content of religious belief and practices was unimportant relative to the quantity of such, other writers focus on the content of a few life-saving aspects of religion. Certainly some beliefs (such as the virgin birth) would not have as much of a life-saving quality as others. For example, Stark and Bainbridge (1980) contend that a common life-saving feature of American religions is the belief in an afterlife. Given the promise of a happy afterlife, worldly, life-threatening crises such as the death of loved ones, unemployment, poor health, and divorce can be endured more readily. In addition, such earthly adversity also might be considered by a religious person as being relatively short-lived compared with eternal life. Such a perspective on time can help one to cope with hard times.

Stack (1983b: 364–65) outlines additional ways in which specific aspects of religion may decrease the likelihood of suicide in the face of traumatic life events. First, religious books such as the Bible often describe role models such as Job who endured enormous suffering—greater than that of most everyday people—but who did not commit suicide. Those who are religious and compare their own sufferings with that of these idealistic role models may be more apt than the irreligious to take their own problems in stride. Second, the religious can read meaning into suffering and so can cope with it. Suffering can be viewed, for example, as God’s plan or as penance for one’s sins. Third, as Gouldner (1975) points out, religion provides an alternative stratification based on morality, not materialism. Those who fail to get ahead in secular society may derive considerable self-esteem from their rank in the religious order of morality. A quest for spiritual success may replace the quest for material success. Fourth, religion sometimes glorifes the state of poverty—”it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God.” Given that the poor have the highest rate of suicide (Stack, 1982), a religion that associates poverty with heavenly reward will help them to cope with their impoverishment and, hence, lower both their own rate and the national rate of suicide. Finally, the religious war against Satan may raise the passions of the religious, uniting them against a common enemy, and so may reduce suicide in a manner similar to a political event such as war. [1]

Research on the relationship between religion and suicide has been marked by conflicting results. While Durkheim’s pioneering work on the subject found a relationship between religious affiliation and suicide, Pope’s (1976: 63–72) reanalysis of Durkheim’s data casts serious doubt on whether there ever was a relationship between religious affiliation and suicide. A review of the research indicates that, for studies coming after Durkheim, there is usually no relationship between religious affiliation and suicide (Stack, 1982: 55–56). However, this does not mean that religion is irrelevant to the prediction of suicide. Instead, studies using measures other than affiliation usually have found significant and sometimes substantial relationships between religiosity and suicide (Stark et al., 1983; Breault and Barkey, 1982; Stack, 1983a, 1983b). For example, Stack’s (1983a) study of church attendance found that it was the leading predictor of suicide rates among the younger age cohorts. In comparative or cross-national research, religious book production rates have been associated with suicide rates (Stack, 1983b; Breault and Barkey, 1982). Finally, Stark, Doyle and Rushing (1983: 128) report a negative correlation of -.36 between church membership rates and suicide rates in large American SMSAs. In summary, there is considerable evidence in support of a relationship between religion and suicide if one uses a measure of religion other than affiliation. Actually, both of the perspectives on religion and suicide may be viewed as correct if we measure the concept of subordination in terms of religiosity, as opposed to Durkheim’s concept of integration based on the sheer number of shared religious beliefs and practices. The present study tests the following hypothesis:

H1: The lower the religiosity in society, the greater the suicide rate.

A key problem with the existing work on religion and suicide is that a control for the state of the family is often absent (Stark et al., 1983; Stack, 1983a, 1983b; Pope and Danigelis, 1981). This is especially true in the work employing measures other than religious affiliation. In addition, essentially all but one of the works dealing with time-series analysis of trend data omit the religious factor altogether (Stack, 1983a). More work is needed to see if the religious variable exerts an effect on suicide that is independent of the effect of family variables over time. That is, is the effect of religion tied to a more general third variable—individualism? The present paper addresses this issue.

Domestic Life and Suicide

The present study focuses on two related dimensions of marriage and the family in its formulation of hypotheses regarding domestic life and suicide: divorce and mother’s labor-force participation. Theoretical interpretations of the relationship between domestic variables and suicide rates range from the classic Durkheimian formulation of integration to current work relating role conflict and mother’s labor-force participation to suicide potential (Durkheim, 1966; Stack, 1978). Both themes can be taken as measures of the degree of individualism in society.

As with the case of religion, the institutions of marriage and the family can act to reduce suicide potential through the subordination of the individual to the collectivity. For example, parents sacrifice some of their own interests and desires in order to meet those of their children. Financially, a new bicycle may be bought instead of a new business suit; a spouse ordinarily subordinates many of his/

The importance of domestic institutions has been noted in the research on suicide (Maris, 1969: 109–14; 1981; Stack, 1980, 1981a, 1981b; Heer and MacKinnon, 1974; see Stack, 1982, for a review). These writers draw associations between suicide and divorce from a variety of standpoints including structural conditions, role transformations, and psychological states common to the divorced population. For example, there is social isolation for the noncustodial parent—still typically the male. For both parents there is some loss of companionship. Sexual tensions are common. On an economic plane there is the structural problem of trying to maintain two households on about the same income, a condition that easily can feed anxiety, depression, and other negative psychological states conducive to suicide as the divorced couple experiences financial strain. Studies on the psychological states of the separated and divorced tend to corroborate the allegations of the structuralists. For example, Weiss (1975) reports a relatively high incidence of depression, prolonged introspection regarding the causes of the divorce, low self-esteem, guilt over the perceived self-produced loss of one’s spouse, and a general deep sense of disorientation and loss. The negative consequences of divorce on well-being are not surprising, given the high priority that Americans give to a happy marriage. This is usually valued as number 1 or 2 in the annual Gallup poll (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1976b: XLIII). Some observers of the relationship between divorce and suicide note that some divorcees who blamed their spouses for all their unhappiness become profoundly disillusioned and suicidal when they find themselves just as unhappy after they have rid themselves of their alleged problem (Lester and Lester, 1971: 66). In any event the micro-oriented literature on the psychological states common among the divorced finds many patterns—depression, low self-esteem, and so on—that are common among the suicidal population (Lester and Lester, 1971: 41–51; Lester, 1983: 134–47). Thus, the second hypothesis tested here is as follows:

H2: The greater the rate of divorce, the greater the suicide rate.

Caution must be exercised, however, in relating the micro-oriented research on the consequences of divorce to the present study, which is based on strictly ecological data. The reader should note that one cannot determine from these data how many suicides involve divorced persons. The paper can only demonstrate an association between the divorce rate on the one hand and the suicide rate on the other hand. Given the ecological nature of the data, it is entirely possible that the association between these two factors may be picking up divorce-related variables (such as the greater phenomenon of marital instability) which, in turn, are related to suicide.

A second aspect of domestic collectivism is mother’s labor-force participation (MPLF). The present study asserts that MPLF constitutes a key consideration for the analysis of domestic collectivism from the standpoint of structuralist explanations of suicide. It assumes that MPLF reduces the amount of mother-child interaction. The degree of mother-to-child subordination should be somewhat reduced by the mother’s participation in the labor force. However, this argument needs some tempering. For example, the mothers involved may be subordinating their self-interests in the economic institution. Work also can provide a source of integration. However, it seems reasonable to assume that the degree of potential family-based collectivism will probably decline in response to increased levels of MPLF. Finally, it is anticipated that the subculture surrounding work—a subculture largely based on individualistic values—will probably not be an effective substitute for collectivistic, family-centered values.

The research evidence on MPLF and suicide has been marked by some mixed results. Cross-national research (Miley and Micklin, 1972; Stack, 1978) and an investigation of Chicago (Newman et al., 1973) found support for the general thesis that female labor-force participation is associated with higher suicide rates. However, the association is sometimes found to be negative, not positive (Cumming et al., 1975). Cumming, Lazer and Chisholm (1975) found that suicide rates were lower for working women than for nonworking women in a British Columbian sample. This result can be interpreted in a number of preliminary ways which stress the benefits of MPLF. For example, the British Columbian women may have experienced high levels of collectivism at the work place which offset low levels at home. In addition, financial gains for the family that are achieved through female employment (and which should reduce economic anomie) may offset the collectivistic and psychological costs. For whatever reason, more research is needed to resolve the controversy over this variable’s relation to suicide. The present study contributes by employing a time-series analysis, something not found in past, basically cross-sectional work.

The MPLF-suicide connection also can be interpreted from the standpoint of a role-conflict explanation of suicide. According to Gibbs and Martin (1964), suicide should vary inversely with the degree to which persons occupy incompatible statuses. For working mothers, MPLF can exemplify such status incompatibility. To the extent that women experience incompatibility between their duties as homemakers and as workers, it would be anticipated that the resulting role conflict and overload would increase the probability of suicide. In addition, to the extent that mates take offense at their wives working for such reasons as feeling like failures in the traditional provider role, MPLF could increase the male role conflict and suicide. A theoretical shortcoming of this perspective is that it neglects a consideration of the benefits of MPLF. Instead, it tends to focus on the costs involved. Finally, this perspective needs to address the issue of whether or not we might anticipate a change in the relationship, given a change in sex-role orientation stemming from the women’s movement or as a response to substantial increases in MPLF itself. That is, with more cultural support for MPLF in our period of great gender-role change, the impact of MPLF on suicide might decline. It is beyond the scope of this paper to address these issues. Rather, it tests the more conservative position in the following hypothesis:

H3: The greater the mother’s labor-force participation, the greater the rate of suicide.

Methodology

The present investigation analyzes suicide rates from the U.S. as a whole for the period 1954–1978. The data on suicide are taken from Diggory (1976) for the 1954–1968 period. The remaining data were obtained through the cooperation of the U.S. National Center for Health Statistics. The rates refer to the number of suicides per 100,000 population. This period was chosen because it is the only period for which yearly data were available for the study’s index of religiosity, church attendance. The analysis stops at 1978 because this was the most recent year for which final data on suicide were available from the U.S. National Center for Health Statistics at the time data were being collected.

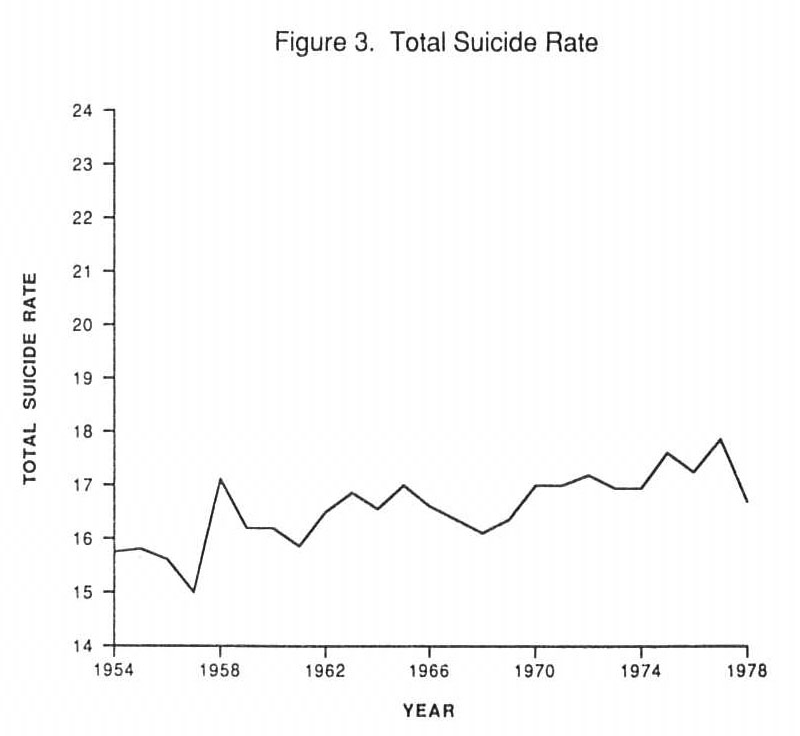

Suicide rates were computed for four groups. First, a rate was computed for the general population (suicides/

Since the present study uses official data on suicide, some caution should be exercised in interpreting its results. Critics of the official data have contended that suicide is often underreported for such reasons as the protection of family reputations (Douglas, 1967). While there undoubtedly is a downward bias in the reporting of suicide in some localities, the real issue is whether any alleged bias is systematic with regard to the unit of analysis. However, research by such writers as Sainsbury and Barraclough (1968), Mendelsohn and Pescosolido (1979), Shepherd and Barraclough (1978), Barraclough and White (1978), and Sainsbury (1973) indicate that any systematic bias in suicide reporting is minimal. In addition, the unit of analysis in the present study involves variation in the yearly suicide rate. There is no evidence of a time-related systematic bias in the underreporting of suicide (Marshall, 1978: 764).

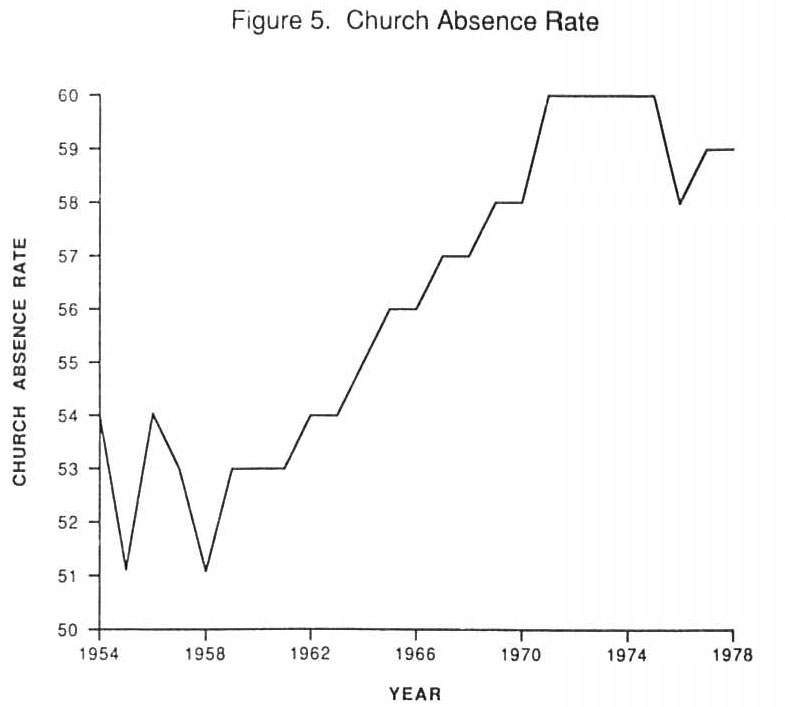

Religious Individualism. The present investigation uses average church/

Did you yourself happen to attend church or synagogue in the last seven days?

Taken from Gallup (1982: 32), data on national church attendance are available back to 1939- However, data before 1954 are available for only 1939 (February), 1940 (November), 1947 (May), and 1950 (April). A problem with the data before 1954 is that they are based on a single observation per year. Since church attendance varies somewhat according to the month of the year, peaking in April and October, the data before 1954 are viewed as unreliable. (Gallup, 1976,1981: 31–32.) The present investigation uses the data on national church attendance in Gallup (1982: 32) for the period 1955–1978. In addition, it adds the data for 1954 from Erskine (1964: 671) which is an average of church attendance estimates for five different weeks in 1954. These data are most suitable for assessing the influence of religiosity on the suicide rate of the national, adult (over 18) population.

Data were also collected on the church attendance rate of the 18- to 29- year-old cohort. These were taken from the same surveys mentioned above and follow the same methodologies. (Gallup, 1981; Erksine, 1964.) [3]

Church attendance is one of the few measures of religious collectivism for which yearly data are available. An alternative measure, church membership, was not used since it does not represent as much religious collectivism as attendance at rituals. [4] A strength of the church attendance measure is that available evidence indicates that it is related to other dimensions of religiosity. Johnstone’s (1975: 83–85) analysis of national data indicates that church attendance was correlated with measures of belief and knowledge. Church attendance was related to important religious beliefs such as belief in Satan and numerous measures of religious knowledge. Also, other research has noted the linkage between church attendance and adherence to orthodox religious beliefs (Hoge and Carroll, 1978; Martin and Nichols, 1962; Hynson, 1975; Hoge and Petrillo, 1978). Finally, church attendance has been linked to participation in still other rituals (Gallup, 1976: 25). In short, the present study follows Demerath (1968: 367–68) in arguing that the trend in the percentage of adults reporting church attendance is one of the more reliable indicators of overall religious change. In order to make the measure of domestic/

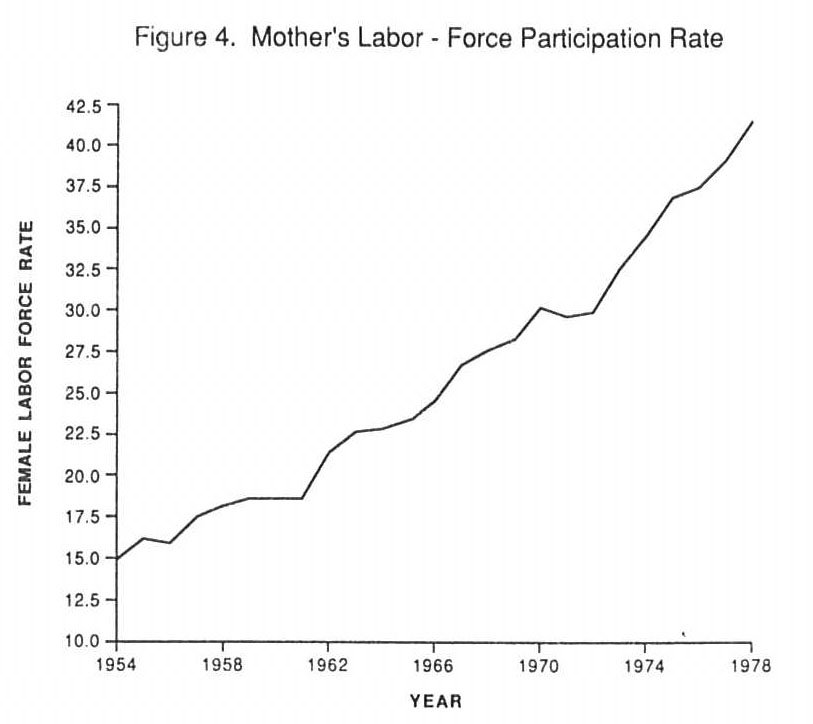

Domestic Individualism. Domestic individualism is measured along two dimensions: the rate of mother’s participation in the labor force and the divorce rate. The rate of mother’s participation in the labor force (MPLF) is measured as the percentage of married women with husbands present and with children under six years of age, who are in the labor force. It is anticipated that the group of married women who might experience the greatest role conflict would be those with preschool-aged children. Older children are normally enrolled in school. Mothers of older children can more readily avoid role conflict, given their lower involvement in child care. In addition, there is less reason to believe that MPLF would constitute mother’s lack of subordination to the family when the home is empty when the children are at school. The data are from the U.S. Bureau of the Census (1976a, 1971–1980). A limitation of this index is that it does not distinguish between full-time and part-time women workers. The former might experience more role conflict and overload as well as a lower level of domestic collectivism. However, usually at least two-thirds of working women are full-time workers, so this is not a major limitation. (Harris and Henderson, 1981: 216.) In any event data were unavailable to construct a more refined measure based on full-time workers. The measure used here is an improvement over the past research based on the proportion of women in the labor force. Such an index counts women such as single females, who are unlikely to experience role conflict between work and household duties.

The rate of divorce is measured as the number of divorces per 1,000 married females. The data are from the U.S. Bureau of the Census (1976a: 64; 1971–1980). A crude divorce rate was not used, due to sensitivity to changes in the age structure of the population (Kenkel, 1977: 328).

In addition to the domestic and religious variables, the present inquiry also includes variables from three other perspectives on suicide. The purpose in including these variables is mainly to weight the explanatory power of domestic/

Economic Anomie. The measure of economic anomie used in the present study is the number of unemployed workers as a percentage of the civilian labor force. The age-specific unemployment rate is used in order to match the data on age-specific church attendance and suicide rates. The data were taken from U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (1982: 478–501). The data on unemployment and church attendance did not match perfectly because of age cutoffs in the unemployment source; however, they were matched as closely as possible. The unemployment rate for 16–24-year-olds was matched with the suicide rate for 15–29- year-olds. This was done since the data source on unemployment provided only data for ten-year age cohorts. The relevant hypothesis is as follows:

H4: The greater the unemployment rate, the greater the rate of suicide.

Presidential Elections. Boor (1981, 1982) has presented evidence of a presidential death dip whereby suicides tend to drop in the period before a presidential election. This can be interpreted from the standpoint of a Durkheimian theory of political integration and suicide. The present paper models the effect of presidential elections as a dummy variable, where 1 = a presidential election year and 0 = other years. The following hypothesis is tested:

H5: The suicide rate will be lower in presidential election years compared with other years.

Suggestion/

H6: The greater the media coverage of suicides, the greater the suicide rate.

Time-Series Issues. Since some readers may not be familiar with econometric methods of time-series analysis (a 1982 review by Miller et al. of methods in studying marriages and families failed to deal significantly with these techniques), the present paper discusses some of the relevant details.

Three somewhat related issues face the researcher in time-series analysis. These are autocorrelation, trending, and finding the appropriate lag structure. These issues are important since, if certain assumptions are not met regarding them, the results of a time-series analysis will be erroneous. That is, for example, if autocorrelation exists in the error terms from a regression analysis of time-series data, one of the fundamental assumptions of regression analysis has been violated. The results of such an analysis probably would not be valid.

Autocorrelation is said to be present when the error terms from an analysis are not independent; that is, et and e M are significantly correlated. Expressed another way, autocorrelation exists when two variables are correlated: the error term and the lag of the error term. [5]

Tests for autocorrelation include the Durbin-Watson d and h statistics, the Geary test based on the number of sign changes in the residual plot, and the Von Neuman ratio (Habibagahi and Pratschke, 1972; Parker, 1980). The present study employs the Durbin-Watson d statistic in its test for autocorrelation for the following reasons. Durbin’s h statistic is appropriate only for models with lagged dependent variables, and there are none in the present analysis. Both the Geary test and the Von Neuman ratio require more cases than those found in the present data set (Johnston, 1972: 250). [6]

A second problem in time-series analysis is the problem of trending; that is, the dependent and/

The problem of trending is related to the problem of autocorrelation since autocorrelation means that successive observations are dependent on each other, such as in positive autocorrelation where the second observation tends to resemble the first observation and so on (Wonnacott and Wonnacott, 1979: 2112). [7]

One possible solution to the problem of trending is to transform all the variables into change values by the first difference technique. [8] The first difference method, however, is based on the assumption that p = 1. Kmenta (1971: 290–92) illustrates that this should be used only if we know that p = 1. Econometricians agree that, unless one knows that p = 1, one should use a technique to estimate it before transforming the data into change values (Wonnacott and Wonnacott, 1979: 218; Stewart and Wallis, 1981: 232; Ostrom, 1978: 38–40). Since the present study uses data wherein the p value is unknown (which is almost always the case in the social sciences), it will adopt what is known as an iterative first differences method for transforming the data into change values with less of trend to them, or with the trend removed. [9]

The present study adopts the Cochrane-Orcutt iterative first difference technique. This is the differencing technique used most widely in sociological time-series analysis. (Rubinson and Ralph, 1984; Wasserman, 1983, 1984; Stack, 1981a, 1982; Stack and Haas, 1984; Box and Hale, 1984: 482; Walters, 1984; Walters and Rubinson, 1983.) [10]

Note that data analyzed under the Cochrane-Orcutt iterative first difference technique refer to change scores and not the original data points. The data are transformed from straight levels or rates to changes in levels or rates. The desired effect of this transformation of data is to detrend the series and purge it of the associated problem of autocorrelation.

The reader should be cautioned about high R2 values in analyses using iterative first difference techniques. These techniques tend to minimize the sum of the squared errors so that one can obtain an underestimate of the true variance and a high degree of variance explained. See Buse (1973) for a discussion. While literally all analyses of time-series data in sociology report high R2 statistics, few mention this bias. For example, R2 statistics are reported as follows: up to 98 (Devine, 1983), up to 88 (Wasserman, 1983), between 82 and 93 (Wasserman, 1983), up to 99 (Walters, 1984), and up to 89 (Box and Hale, 1984). The present investigation, it is anticipated, also will report high R2 values, but these are common in time-series analysis, especially that based on iterative procedures. [11]

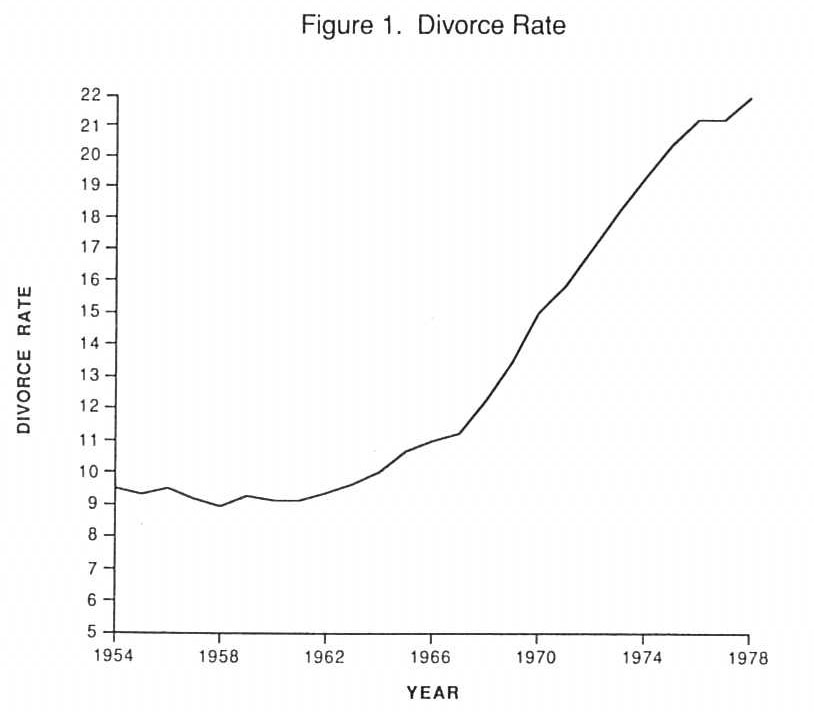

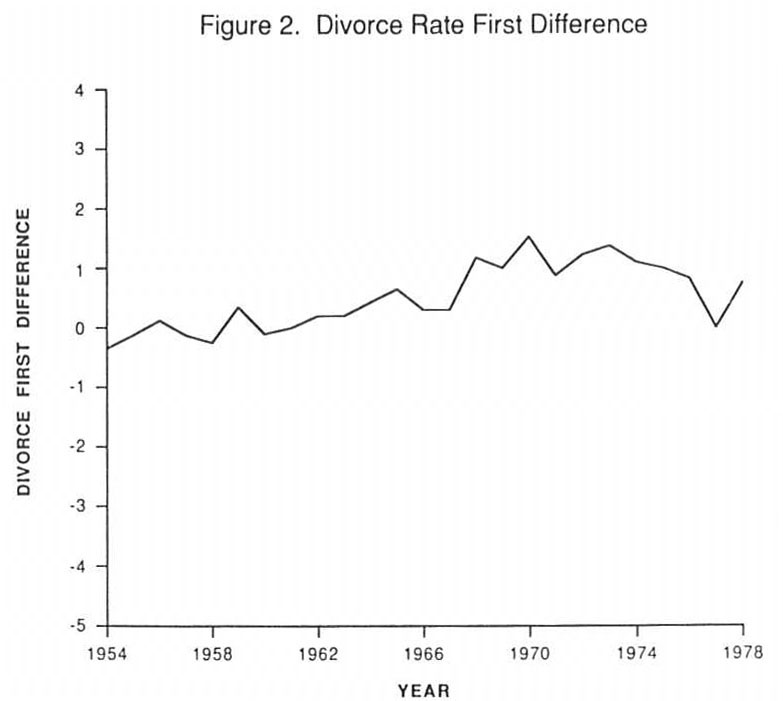

To help clarify the issues of trending and autocorrelation, the paper now turns to an assessment of two plots of one of its independent variables, the divorce rate. Figure 1 illustrates the upward, somewhat parabolic trend in the divorce rate over time. Analysis of these data together with data on the suicide trend (also marked by a general upswing) was marked by the problem of autocorrelation. The present analysis begins by taking the first difference of each variable in order to detrend the series of each. Figure 2 illustrates the plot of the first difference of the divorce rate. This simple transformation (which assumes that p = 1) greatly reduces the upswing in the curve. The Cochrane- Orcutt procedure searches for a value of p < 1 which should reduce the degree of autocorrelation further than that for the data in Figure 2.

Analysis

The matrix of zero-order correlation coefficients is given in Table 1. Both indicators of domestic individualism (divorce and mother’s participation in the labor force) are highly related to the total suicide rate. Religious individualism—measured as church absence—is also highly related to suicide (r = .82). The presidential election and media dummy variables are not significantly related to suicide. Finally, as anticipated, the unemployment rate bears a significant positive relationship to suicide. However, it should be pointed out that time (year) is also correlated both with the suicide rate and with trends in the independent variables from the domestic/

Table 1. Pearson Correlation Matrix, Means, Standard Deviations

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 1. Church absence | -- | .88* | .85* | -.04 | .01 | .22 | .90* | .82* | .91* |

| 2. Mother's labor-force participation | -- | .96* | -.02 | -.03 | .43* | .99* | .95* | .99* | |

| 3. Divorce rate | -- | -.06 | -.01 | .53 | .98 | .93* | .93* | ||

| 4. New York Times suicide stories | -- | -.14 | .16 | -.03 | .05 | -.02 | |||

| 5. Presidential election year | -- | -.02 | -.02 | -.06 | .00 | ||||

| 6. Unemployment rate | -- | .44* | .62* | .38 | |||||

| 7. Domestic/ | -- | .95* | .98* | ||||||

| 8. Total suicide rate | -- | .93* | |||||||

| 9. Year | -- | ||||||||

| Mean | 56.1 | 25.8 | 13.2 | 1.44 | .24 | 5.33 | 0 | 11.2 | 1966 |

| SD | 3.00 | 7.95 | 4.63 | 1.16 | .44 | 1.25 | 9.51 | .93 | 7.35 |

*p<.05

There are some problems of multicollinearity among the independent variables. The indicators of domestic individualism are highly correlated (r = .96). In addition, the religious individualism factor is highly correlated with each of these domestic variables (r = .86, r = .88). Charts plotting these three variables indicate that generally they all increased together over the period under analysis (see Figures 1, 4, and 5).

These correlations are all marked by the problem of trending among the three religious/

Table 2. Cochrane-Orcutt Iterative First Difference Estimates of the Bivariate Relationships between Domestic and Religious Individualism, 1954-1978

| Dependent Variables | |||

| Independent Variables | Church Absence | MPLF | Church Absence |

| Divorce rate | 495a | 1.66 | |

| .129b | .185 | — | |

| 3.81* | 8.99*c | ||

| MPLF | .274 | ||

| — | — | .063 | |

| 4.37 | |||

| Durbin-Watson d | 2.38 | 1.47 | 2.24 |

| Autocorrelation | None | None | None |

| R2 | 93 | 63 | 91 |

aRegression coefficient

bStandard error

ct ratio

*t statistic significant at .05 level

The results of the plots of the independent variables, bivariate zero-order corrrelation, and the iterative first difference equations in Table 3 all point in the same direction. That is, the indicators of domestic and religious individualism are relatively inseparable. They form a common variable or factor measuring the greater phenomenon of individualism.

To test for the problem of autocorrelation and trending with respect to the suicide variable, a regression analysis using untransformed data and ordinary least squares (OLS) techniques was performed for each independent variable on the total suicide rate. Four of the six regressions had Durbin Watson d statistics that indicated the presence of positive autocorrelation. A seventh regression which regressed time on suicide, also was marked by autocorrelation. Given these problems of autocorrelation, the analysis now turns to the Cochrane- Orcutt estimates based on transformed data. These data refer to changes in the variables, the original data points having been transformed using the technique of iterative first difference. [12]

Table 3. Cochrane-Orcutt Iterative First Difference Estimates of the Effects of the Independent Variables on the Total Suicide Rate, 1954-1978

| Equation | ||||||

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Divorce Rate | .186*a .073b 10.74c | — | — | — | — | — |

| MPLF | — | .108* .010 11.19 | — | — | — | — |

| Church absence rate | — | — | .017 .063 .027 | — | — | — |

| New York Times suicide stories | — | — | — | .075 .049 1.55 | — | — |

| Presidential election year | — | — | — | — | -.125 .117 -1.06 | — |

| Unemployment rate | — | — | — | — | — | .213* .070 3.04 |

| Durbin-Watson d statistic | 1.93 | 1.89 | 2.18 | 2.27 | 2.21 | 2.38 |

| Autocorrelation R2 | none 82 | none 84 | none 70 | none 70 | none 70 | none 78 |

R2828470707078aRegression coefficient

bStandard error

ct ratio

*statistic significant at .05 level

Table 3 provides the results of the Cochrane-Orcutt iterative first difference procedures with each of the variables entered into the analysis by itself. Columns 1 and 3 provide the results for the religious and marital individualism variables. In each case 70 percent or more of the variance is explained. Given the close association in these trends, however, when two or three of these variables are entered together into analyses not reported here, one or two become totally insignificant. The beta coefficient for the significant individualism variable often exploded to over 1.00. This indicates that, given the multicollinearity among the individualism variables, the betas for some are biased upwards and the betas for the others are biased downward.

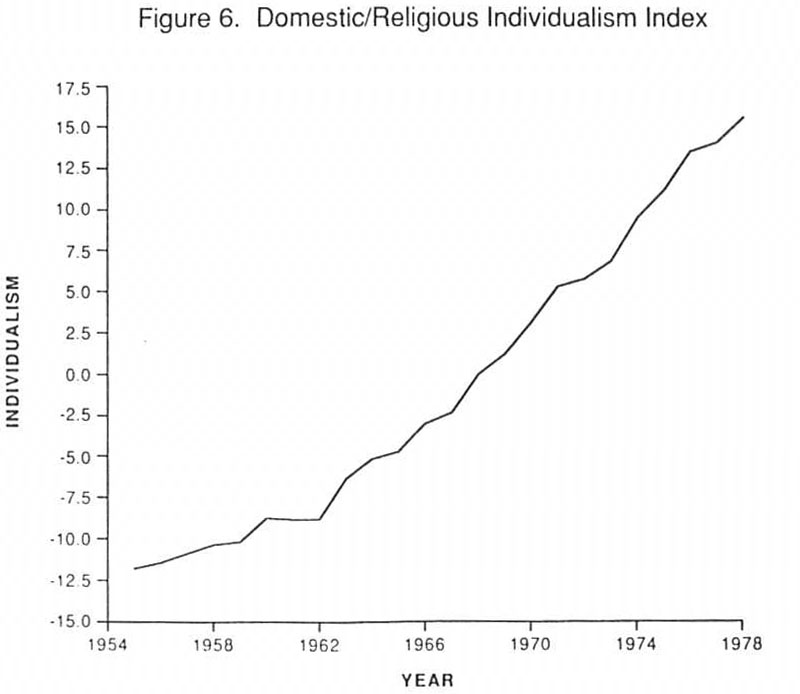

The present paper contends that these intercorrelations and trends indicate that the three variables are all measuring the same underlying weakening of social collectivism. For this reason, in the multivariate analysis the three are combined into a single index of individualism through a principal components analysis (Kleinbaum and Kupper, 1978: 389–92). The first of the three factors from the principal components analysis was used, since this is the one that loads most heavily on the individual components. The resulting principal component is referred to as the Domestic/

A separate principle components analysis was done for the variables representing the youth cohort, ages 15–29. The cumulative percentages of eigenvalues for the first principal component were 97 and 96 respectively for the components representing the total and youth populations.

Table 4 presents the results of the three regressions employing the domestic/

Table 4. Cochrane-Orcutt Iterative First Difference Estimates of the Domestic/

Individualism Index and Unemployment on the Total Suicide Rate, 1954-1978

| Variables | Total Suicide Rate | Male Suicide Rate | Female Suicide Rate |

| Domestic/ | .751** | .468** | .384** |

| New York Times suicide stories | .030 | .028 | .041 |

| Presidential election year | .021 | -.055 | -.130 |

| Unemployment | .207** | .381** | .267* |

| R2 | 96 | 86 | 34 |

| Durbin-Watson d statistic | 1.92 | 1.88 | 1.99 |

| Autocorrelation at .05 level | none | none | none |

| *Associated t statistic significant at .10 level **Associated t statistic significant at .05 level |

With respect to the sex-specific rates, the religious/

Table 5. Cochrane-Orcutt Iterative First Difference Estimates of the Effect of the Domestic/

| Variables | Total 15-29 Suicide Rate | Suicide Rate: Males, 15-29 | Suicide Rate: Females, 15-29 |

| Domestic/ | .902** | .965** | .880** |

| New York Times suicide stories | .013 | .020 | .172 |

| Presidential election year | -.016 | -.031 | -.101 |

| Unemployment rate (16-24) | .127** | .139** | .235** |

| R2 | 98 | 96 | 67 |

| Durbin-Watson d statistic | 2.10 | 1.98 | 1.89 |

| Autocorrelation at .05 level | None | None | None |

| *Associated t statistic significant at .10 level **Associated t statistic significant at .05 level |

Table 5 focuses on the suicide rates of young adults, a group whose suicide rate nearly tripled over the period under investigation. The effect of the religious/

Conclusion

The present investigation has tested a model of suicide that combines trends in the marital/

One unanticipated finding should stimulate further work. Both for the general population and for the youth cohort, the model works better for males than for females. While it is beyond the scope of the present paper to systematically explain this differential, two lines of explanation might be tested in future work. First, it very well may be that males suffer more from MPLF than do their wives. That is, they may experience, for example, more role conflict than their wives from their wives’ employment. This explanation was suggested for some similar findings in a cross-national study. (Stack, 1978.) Second, the increase in suicide potential from MPLF may be tempered for the mothers involved, given the benefits of employment such as adult companionship, career mobility, and extra income; so while this trend is associated with increased suicide for females, the increase is not as great as it might be, since the benefits of employment for the mothers offset some of the costs. In contrast, for the males the principle benefit may only be additional income.

The economic anomie theory received strong support. In five or six regressions, the unemployment rate was significant (at the .05 level). This finding is consistent with previous work. However, the associations between unemployment and suicide are sometimes stronger for males than for females. This is often interpreted from the standpoint of gender-role theory: in this view the male is still under much greater pressure to be employed, and to be the principal breadwinner, than the female. Hence, unemployment should promote more anomie for the male than for the female as long as sex roles regarding employment expectations are different between the sexes.

Some caution should be exercised in generalizing the results of the present study since it is based on the U.S., a nation marked by relatively high levels of economic individualism. The results may not replicate for other nations with high levels of economic collectivism and integration. For example, it might be that in such nations as Japan or Sweden the trends in domestic and religious individualism may be tempered or even offset by economic collectivism. That is, in a context of economic collectivism, the relationship between domestic/

Bibliography

Ahlburg, D. and M. Shapiro. 1984. “Socioeconomic Ramifications of Changing Cohort Size.” Demography 21: 97–108.

Aldous, J. and W. D’Antonio. 1983. “Families and Religions Beset by Friends and Foes.” Pp. 9–16 in W. D’Antonio and J. Aldous (eds.), Families and Religions. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Austin, R. 1982. “Women’s Liberation and Increases in Minor, Major, and Occupational Offenses.” Criminology 20 (November): 407–30.

Barraclough, B. M. and S. White. 1978. “Monthly Variation in Suicidal, Accidental, and Undetermined Poisoning Deaths.” British Journal of Psychiatory 132: 279–82.

Beach, C. M. and J. G. MacKinnon. 1978. “A Maximum Likelihood Procedure for Regression with Autocorrelated Errors.” Econometrica 46 (January): 51–58.

Bellah, R. N. 1976. “The New Religious Consciousness and the Crisis in Modernity.” In C. Y. Glock and R. N. Bellah (eds.), The New Religious Consciousness. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Bellah, R. N. 1978. “Religion and Legitimation in the American Republic.” Society 15: 16–23.

Bollen, K. and D. Phillips. 1982. “Imitative Suicides.” American Sociological Review 47: 802–9.

Boor, M. 1981. “Presidential Elections and Suicide.” American Sociological Review 46: 616–18.

Boor, M. 1982. “Reduction in Deaths by Suicide, Accidents, and Homicides Prior to United States Presidential Elections.” Journal of Social Psychology 118: 135–36.

Box, S. and C. Hale. 1984. “Liberation/

Breault, K. D. and K. Barkey. 1982. “A Comparative Analysis of Durkheim’s Theory of Egoistic Suicide.” Sociological Quarterly 23: 321–32.

Brenner, H. 1976. Estimating the Social Costs of National Economic Policy. Washington, D.C: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Brenner, H. 1984. Estimating the Effects of Economic Change on National Health and Social Well Being. A study prepared for the Joint Economic Committee of the U.S. Congress. Washington, D.C: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Buse, A. 1973. “Goodness of Fit in Generalized Least Squares Estimation.” American Statistician 27: 106–9.

Carroll, J., D. W. Johnson, and M. Marty. 1979. Religion in America, 1950 to the Present. San Francisco: Harper and Row.

Cohen, L., and M. Felson. 1979. “Social Change and Crime Rate Trends.” American Sociological Review 44 (August): 588–607.

Cohen, L., M. Felson, and K. Land. 1980. “Property Crime Rates in the U.S.” American Journal of Sociology 86 (July): 90–116.

Cumming, E., C. Lazer, and L. Chisholm. 1975. “Suicide as an Index of Role Strain Among Employed and Not Employed Married Women in British Columbia.” Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology 24:462–70.

Danigelis, N., and W. Pope. 1979. “Durkheim’s Theory of Suicide as Applied to the Family.” Social Forces 57: 1081–1106.

D’Antonio, W. 1980. “The Family and Religion: Exploring a Changing Relationship.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 19: 89–104.

D’Antonio, W. 1983. “Family Life, Religion, and Societal Values.” Pp. 81–108 in W. D’Antonio and J. Aldous (eds.), Families and Religions. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

D’Antonio, W., and J. Aldous (eds.) 1983. Families and Religions: Conflict and Change in Modern Society. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Degler, C. N. 1980. At Odds: Women and the Family in America from the Revolution to the Present. New York: Oxford University Press.

Demerath, N. J. 1968. “Trends and Anti-trends in Religious Change.” Pp. 349–448 in E. B. Sheldon and W. E. Moore (eds.), Indicators of Social Change. New York: Russell Sage.

Devine, J. 1983. “Fiscal Policy and Class Income Inequality: The Distributional Consequences of Government Revenues and Expenditures in the U.S., 1949–1976.” American Sociological Review 48 (October): 606–22.

Diggory, J. 1976. “United States Suicide Rates, 1933–1968: An Analysis of Some Trends.” Pp. 30–65 in E. Shneidman, Suicidology—Contemporary Developments. New York: Grosse and Straton.

Douglas, J. 1967. The Social Meaning of Suicide. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Durbin, J., and G. S. Watson. 1950. “Testing for Serial Correlation in Least Squares Regression, Part I.” Biometrica 37: 409–28.

Durbin, J., and G. S. Watson. 1951. “Testing for Serial Correlation in Least Squares Regression, Part II.” Biometrica 38: 159–78.

Durkheim, E. 1966. Suicide. New York: The Free Press.

Erskine, H. 1964. “The Polls: Church Attendance.” Public Opinion Quarterly 28: 669–79.

Erskine, H. 1965. “The Polls: Personal Religion.” Public Opinion Quarterly 29: 145–57.

Eshleman, J. R. 1981. The Family. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Gallup, G. 1972. The Gallup Poll: Public Opinion, 1935–1971. New York: Random House.

Gallup, G. 1976. “Religion in America, 1976.” The Gallup Opinion Index, Report No. 130. Princeton, NJ: Gallup International.

Gallup, G. 1981. “Religion in America.” The Gallup Opinion Index, Report No. 184. Princeton, NJ: Gallup International.

Gallup, G. 1982. “Religion in America.” The Gallup Opinion Index, Report No. 201–2. Princeton, NJ: Gallup International.

Gibbs, J. 1982. “Testing the Theory of Status Integration and Suicide Rates.” American Sociological Review 47: 277–37.

Gibbs, J., and W. T. Martin. 1964. Status Integration and Suicide. Eugene, OR: University of Oregon Press.

Gorsuch, R. L. 1976. “Religion as a Significant Predictor of Important Human Behavior.” In W. Donaldson, Research in Mental Health and Religious Behavior. Atlanta: Psychological Studies Institute.

Gouldner, A. 1975. The Coming Crisis of Western Sociology. New York: Avon.

Habibagahi, H., and J. L. Pratschke. 1972. “A Comparison of the Power of the Von Neuman Ratio, Durbin Watson and Geary Tests.” Review of Economics and Statistics 54 (May): 179–85.

Halbwachs, M. 1978. The Causes of Suicide. New York: Free Press.

Hargrove, B. 1983. “The Church, the Family and the Modernization Process.” Pp. 21–48 in W. D’Antonio and J. Aldous (eds.), Families and Religions. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Harris, R., and J. J. Henderson. 1981. “Effects of Wife’s Income on Family Income Inequality.” Sociological Methods and Research 10: 211–32.

Heer, D., and D. MacKinnon. 1974. “Suicide and Marital Status: A Rejoinder to Rico-Velasco and Mynki.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 36 (February): 6–10.

Henry, A. F., and J. F. Short, Jr. 1954. Suicide and Homicide. New York: Free Press.

Hibbs, D. 1974. “Problems of Statistical Estimation and Causal Inference in Dynamic Time Series Models.” Pp. 252–308 in H. Costner (ed.), Sociological Methodology. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Hoge, D., and J. Carroll. 1978. “Determinants of Commitment and Participation in Protestant Churches.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 17: 107–27.

Hoge, D., and G. Petrillo. 1978. “Determinants of Church Participation and Attitudes Among High School Youth.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 17: 359–79.

Hynson, L. 1975. “Religion, Attendance and Belief in an Afterlife.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 14: 285–87.

Johnston, J. 1972. Econometric Methods (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Johnston, J. 1984. Econometric Methods (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Johnstone, R. 1975. Religion and Society. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Kelejian, H. H., and W. E. Oates. 1974. Introduction to Econometrics. New York: Harper and Row.

Kenkel, W. 1977. The Family in Perspective (4th ed.). Santa Monica, CA: Goodyear Publishing.

Kleinbaum, D., and L. Kupper. 1978. Applied Regression Analysis and Other Multivariate Techniques. North Scituate, MA: Duxbury Press.

Kmenta, J. 1971. Elements of Econometrics. New York: Macmillan.

Lasch, C. 1977. Haven in a Heartless World: The Family Besieged. New York: Basic Books.

Lester, D. 1983– Why People Kill Themselves (2nd ed.). Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas.

Lester, D., and G. Lester. 1971. Suicide: The Gamble with Death. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Maris, R. W. 1969– Social Forces in Urban Suicide. Homewood, IL: Dorsey Press.

Maris, R. W. 1981. Pathways to Suicide. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Marshall, J. 1978. “Changes in Aged White Male Suicide, 1948–1972.” Journal of Gerontology 33: 763–68.

Marshall, J. 1981. “Political Integration and the Effect of War on Suicide: United States, 1933–1976.” Social Forces 59: 771–85.

Martin, C., and R. C. Nichols. 1962. “Personality and Religious Belief.” Journal of Social Psychology 56: 3–8.

Masaryk, T. 1970. Suicide and the Meaning of Civilization. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (originally published, 1882).

Mendelsohn, R., and B. Pescosolido. 1979. “The Self as Victim: Rethinking Sociological Theories of Suicide.” Paper presented at the annual meetings of the American Public Health Association.

Merton, R. 1938. “Social Structure and Anomie.” American Sociological Review 3: 672–82.

Miley, J., and M. Micklin. 1972. “Structural Change and the Durkheimian Legacy: A Macrosociological Analysis of Suicide Rates.” American Journal of Sociology 78: 657–73.

Miller, B., B. C. Rollins, and D. Thomas. 1982. “On Methods of Studying Marriages and Families.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 44 (November): 851–73.

Morselli, E. A. 1882. Suicide: An Essay on Comparative Moral Statistics. New York: Appleton- Century.

Newman, J. , K. R. Whittemore and H. G. Newman. 1973. “Women in the Labor Force and Suicide.” Social Problems 21: 220–80.

Ostrom, C. 1978. Time Series Analysis. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Parker, R. 1980. “Correlation in Time Series Regression: The Geary Test.” Sociological Methods and Research 9: 99–114.

Phillips, D. 1974. “The Influence of Suggestion on Suicide.” American Sociological Review 39 (June): 340–54.

Phillips D. 1983. “The Impact of Mass Media Violence on U.S. Homicides, 1973–1978.” American Sociological Review 48(August): 560–68.

Pope, W. 1976. Durkheim’s Suicide: A Classic Reanalyzed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Pope, W., and N. Danigelis. 1981. “Sociology’s One Law.” Social Forces 60: 495–516.

Ralph, J., and R. Rubinson. 1980. “Immigration and the Expansion of Schooling in the U.S., 1890–1970.” American Sociological Review 45 (December): 943–54.

Rubinson, R., and J. Ralph. 1984. “Technical Change and the Expansion of Schooling in the United States, 1890–1970.” Sociology of Education 57 (July): 134–51.

Sainsbury, P. 1973. “Suicide: Opinions and Facts.” Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 66: 579–87.

Sainsbury, P., and B. Barraclough. 1968. “Differences Between Suicide Rates.” Nature 220 (4): 1252.

Shepherd, D., and B. M. Barraclough. 1978. “Suicide Reporting: Information or Entertainment?” British Journal of Psychiatry 132: 283–87.

Stack, S. 1978. “Suicide: A Comparative Analysis.” Social Forces 57 (December): 644–53.

Stack, S. 1980. “The Effects of Marital Dissolution on Suicide.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 42(February):83–92.

Stack, S. 1981a. “Divorce and Suicide: A Time Series Analysis, 1933–1970.” Journal of Family Issues 2(March):77–90.

Stack, S. 1981b. “Suicide and Religion: A Comparative Analysis.” Sociological Focus l4(August): 207–20.

Stack, S. 1982. “Suicide: A Decade Review of the Sociological Literature.” Deviant Behavior 4: 41–66.

Stack, S. 1983a. “The Effect of the Decline in Institutionalized Religion on Suicide: 1954–1978.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 22 (September): 239–52.

Stack, S. 1983b. “The Effect of Religious Commitment on Suicide: A Cross-national Analysis.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 24 (December):362–74.

Stack, S., and N. Danigelis. 1985. “Modernization and Gender Suicide Rates, 1919–1972.” In R. Tomasson (ed.), Comparative Social Research (Vol. 8). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press (forthcoming).

Stack, S., and A. Haas. 1984. “The Effect of Unemployment Duration on National Suicide Rates: A Time Series Analysis, 1948–1982.” Sociological Focus 17 (January): 17–30.

Stark, R., and W. S. Bainbridge. 1980. “Towards a Theory of Religion: Religious Commitment.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 19: 114–28.

Stark, R., D. Doyle and J. Rushing. 1983. “Beyond Durkheim: Religion and Suicide.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 22: 120–31.

Stewart, M., and K. Wallis. 1981. Introductory Econometrics (2nd ed.). New York: Halstead Press.

Tittle, C., and M. Welch. 1983. “Religiosity and Deviance.” Social Forces 61 (March): 653–82.

Treas, J. 1983. “Trickle Down or Transfers? Postwar Determinants of Family Income Inequality.” American Sociological Review 48 (August): 546–59.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 1982. Labor Force Statistics Derived from the Current Population Survey: A Databook (Vol. 1). Washington, D.C: U.S. Government Printing Office.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. 1976a. Historical Statistics of the United States: Colonial Times to 1970, Part 1. Washington, D.C: U.S. Government Printing Office.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. 1976b. Social Indicators. Washington, D.C: U.S. Government Printing Office.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. 1971–1980. US. Statistical Abstract. Washington, D.C: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Walters, P. B. 1984. “Occupational and Labor Market Effects on Secondary and Postsecondary Educational Expansion in the U.S., 1922–1979.” American Sociological Review 49 (October): 659–71.

Walters, P. B., and R. Rubinson. 1983. “Educational Expansion and Economic Output in the U.S., 1890–1969.” American Sociological Review 48(August): 480–93.

Wasserman, I. 1983. “Political Business Cycles, Presidential Elections, and Suicide Mortality Patterns.” American Sociological Review 48: 711–20.

Wasserman, I. 1984. “Imitation and Suicide: A Re-examination of the Werther Effect.” American Sociological Review 49(April): 427–36.

Weiss, R. 1975. Marital Separation. New York: Basic Books.

White, K. 1978. “A General Computer Program for Economic Methods—Shazam.” Econometrica 46 (January): 239–40.

Wonnacott, R., and T. Wonnacott. 1979. Econometrics (2nd ed.). New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Yankelovich, D. 1981. New Rules: Searching for Self-Fulfillment in a World Turned Upside Down. New York: Random House.

Notes

[1] Tittle and Welch (1983) interpret the association between low religiosity and deviance from several theoretical perspectives. While their article does not deal with suicide per se, the broad theoretical arguments reviewed have some relevance to the present discussion. First, from the perspective of functionalism, religion fosters moral commitments and controls deviance by linking supernatural sanctions to moral precepts. For the present purpose, it is assumed that the greater the religiosity, the greater the moral revulsion or potential feelings of guilt towards suicide, and the lower the propensity to suicide. Second, from the perspective of differential association theory—given that most religious people tend to be conventional (e.g., opposed to suicide)—the greater the associations with religious people (e.g., attendance at religious services), the less the likelihood of deviance (e.g., suicide). Third, various psychological and social-psychological perspectives suggest a negative association between religiosity and suicide. For example, Gorsuch (1976) contends that religious involvement fosters behavioral ideals whereby the contemplation of rule-breaking behavior sets in motion strong feelings of cognitive dissonance, which effectively lowers the incidence of deviant behavior. Fourth, from a standpoint of deterrence theory also, we would suspect a negative association between religiosity and suicidal behavior. The main idea here is that the greater the potential costs of deviance, the lower its incidence. Given that those who ponder deviating from religious norms against suicide could anticipate informal negative sanctions from the religious community, they should be less likely to attempt suicide. Finally, conflict theory also might predict a negative association between religiosity and suicide. Given that the frustrations associated with perceived failure promote suicidal behavior, religion can reduce suicide potential by diverting individual aspirations to the afterlife. This is similar to Gouldner’s notion of the positive function of religion as an alternative stratification system. In a Marxist perspective, religion functions in this fashion as an opium of the people. Using Merton’s (1938) theory of anomie, religion can take the edge off of the anomie felt by the lower class. To the extent that religion detracts people from exploitative social arrangements, subordinate status, and other problems associated with deviant behavior, it should reduce suicide potential.

[2] In contrast, church attendance rates remained relatively constant for those over fifty years old and declined only somewhat for the middle-aged group (thirty to forty-nine). As we might expect, moreover, suicide rates did not increase substantially for the older age cohorts; in fact, the suicide rate for the elderly actually decreased in this period. In contrast, the youth suicide rate increased by nearly 300 percent. A second reason why the present study focuses on the youth suicide rate is that this group also experienced the greatest upswing in domestic individualism. For example, it has the highest divorce rate, since most divorces occur in the first seven years of marriage and since people generally marry in their early twenties. (Eshleman, 1981.) In analyses not reported here, the effect of domestic/

[3] For several years some age-specific church attendance rates were not available. For these years linear point interval estimates were made to fill in the missing values.

[4] Another possibility for a measure of religiosity would be religious book production (Breault and Barkey, 1982). However, annual data on the number of books produced are not available for most years for the U.S. Instead, annual data on religious books refer to the number of new titles and new editions (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1976a:803,808). Since the number of titles says nothing about the actual numbers of each respective title produced, these data were not used.

[5] There are two broad categories of autocorrelation. In positive autocorrelation a positive error tends to be followed by another positive error, and negative errors tend to be followed by additional negative errors. Here, the greater the value of the variable et, the greater the value of et–1. A plot of residuals from such an analysis would resemble an S or sine curve. In contrast, in negative autocorrelation a negative error term tends to be followed by a positive error term, and vice versa. Here, the greater the value of et the less the value of et–1. A plot of residual values here would show a line zigzagging back and forth from positive to negative error terms. The first-order autoregressive function can be expressed as et = pet–1 = Vt, where p is a regression coefficient and V is a random variable. (Ostrom, 1978: 16.) Each disturbance term is equal to a proportion (p) of the preceding disturbance term plus a random variable (V). P values range between -1 and + 1 . Perfect positive autocorrelation occurs if p = 1; perfect negative autocorrelation occurs if p = –1 ; and a value of p = 0 always means the total absence of autocorrelation.

[6] As Kelejian and Oates (1974) point out, the Durbin-Watson d statistic can be calculated as follows: d = 2(1–p). Given that the coefficient varies between –1 and +1 , the range of d is from 0 to + 4 . Hence, p = 0 implies d = 2 and no autocorrelation; p = –1 implies d = 4, perfect negative autocorrelation; p = +1 implies perfect positive autocorrelation. In the social sciences positive autocorrelation is far more common than is negative autocorrelation (Ostrom, 1978). Durbin and Watson (1950, 1951) established upper and lower limits for d in testing for the presence of autocorrelation in analyses of different sample sizes and different numbers of predictor variables. An expanded version of their table for small samples and greater numbers of predictor variables is available in Johnston (1984: 554–57). As Johnston (1984: 315–16) points out, if d < dL, then positive autocorrelation is present; if du < d < 4–du, autocorrelation is absent; if dL ≤ d ≤ du, the test is inconclusive. In the present study with a sample of 25 and one independent variable, the appropriate d values for testing for positive autocorrelation would be d-lower = 1.29, and d-upper = 1.45 (Johnston, 1984: 556–57). A d value of less than 1.29 would mean that the error terms were marked by positive autocorrelation; a value in between and including 1.29 and 1.45 would be in a gray or inconclusive area; a value between 1.46 and 2.54 would mean an absence of positive autocorrelation; values above 2.54 would indicate either negative autocorrelation (>2.72) or inconclusiveness in another gray region (2.54–2.71).

[7] In one study that reported Durbin-Watson statistics and failed to transform the original data, only 4 of 24 OLS regressions were free of autocorrelation (Ralph and Rubinson, 1980).

[8] Here one transforms all the original data points into first differences: Yt–Yt–1 and Xt–Xt–1; then one estimates the equation as follows: Yt–Yt–1 = a + b(Xt–X t–1) + (et–et–1).

[9] A second technique that has been used to address trending and/

[10] The Cochrane-Orcutt method first uses OLS to obtain estimates of the error terms. These residuals then are used to obtain first-round estimates of the value of p, where p = ∑etet–1 /∑e2t–1 and t = 2, 3, . . . T. Then the value of p is used to transform the original data points (Johnston, 1984: 323–24): Y' = Yt–pYt–1 and X' = Xt–pXt–1. The transformed data then are entered into another analysis to obtain a second-round estimate of p. The data are transformed again using this value, and the procedure continues through enough iterations or rounds until the estimates converge. The final form of the equation uses the best estimate of the value p and, again, is based on transformed data where the equation relates changes in Y to changes in the X variables. The present study uses an econometric software package called Shazam to perform the Cochrane-Orcutt analyses (Johnston, 1984: 326; White, 1978).

[11] Finally there is the issue of lag structures in time-series problems. That is, does a variable have an immediate effect on the dependent variable during the year both are measured, or does the influence of the independent variable occur at some later point in time? For example, is the effect of unemployment on suicide more or less immediate, or does it affect suicide at some future point in time? To address this question several lagged variables were constructed from each original independent variable. These were lagged up to three years in time to test for stalled effects. In all cases the nonlagged variable was the one most closely associated with the variance in suicide. Hence, the analysis reported here does not include any lagged variables. The findings on the unemployment rates are consistent with past research by Brenner (1976,1984) who also reported immediate effects of unemployment on suicide.

[12] In a series of OLS runs not reported here, the total suicide rate was regressed on each independent variable and year. Controlling for year (time), MPLF and the divorce rate were still significantly related to suicide. Church absence was not significantly related to suicide once the effect of year was controlled. In the equation with year and unemployment as exogenous variables, both year and unemployment were significantly related to suicide. Neither the media nor the presidential election variables were significantly related to suicide with year controlled. These equations either were free of autocorrelation or had d statistics in the gray area. However, all of the religion/