The Sermon on the Mount and Third Nephi

Krister Stendahl

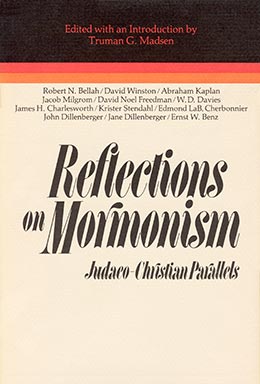

Krister Stendahl, “The Sermon on the Mount and Third Nephi,” in Reflections on Mormonism: Judaeo-Christian Parallels, ed. Truman G. Madsen (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1978), 139–54.

The Book of Mormon, which has now reached into more than sixty languages and cultures, is viewed by faithful Mormons as a divinely inspired supplement to the biblical comprehension of Christ. But so much controversy has surrounded the origin and transmission of the book that its content, its central themes, have been virtually neglected at the hands of biblical scholars. Now many (like Jacob Neusner) speak of the book as a “fresh Christian expression,” and it is more and more widely recognized that the book, whatever its genesis, is full of ancient Jewish and Christian lore.

Krister Stendahl, a New Testament expert (especially in the book of Matthew), is adept in the tools of redaction analysis, form criticism, and comparative linguistic exposition. In this essay he “brackets” the question of how Joseph Smith brought the Book of Mormon forth. He focuses instead on the heart of hearts of the Book of Mormon—the book of 3 Nephi—comparing it with the text of the Sermon on the Mount in Matthew. Third Nephi, he shows, is less like the synoptic gospels than it is like the fourth Gospel. That book is differently ordered and focused and heightens the divine quality of Christ’s ministry. Stendahl approaches 3 Nephi as a Targum, a kind of “timeless apocryphon.” Sections of it overlap the biblical record and other sections fill in and intensify it. Overall, 3 Nephi “Christologizes.” It claims for Christ more than that he is a teacher in conflict with some of the versions of Judaism of his day. He is a Savior coming in his own name. Christ, not his interpreters, is at center stage in the last twenty-three chapters of the hook. The portrait of Christ that emerges is more than of a Jewish revolutionary—he is Redeemer and Revelator in the midst of a beautifully responsive community.

T. G. M

This is the first attempt on my part toward an exegesis of the Book of Mormon. I consider it as an opportunity in many ways. I hope you do not feel offended if I say that for a biblical scholar it is an absolutely unique privilege to be right here in one of the laboratories of God’s guinea pigs. What I mean is this: Here is a community of faith centered in a specific revelation in the 1830s. That is like visiting with the Christian Church ca. A.D. 150—a fascinating opportunity indeed for a New Testament scholar. Here amongst you are people who remember by family traditions those who surrounded the bearer of the revelation that you honor in Joseph Smith. It is an exciting prospect, and I thank you for the opportunity.

In thinking about the Sermon on the Mount and 3 Nephi, especially chapters 12–14, I would like to apply also to 3 Nephi methods, types of reflections that come natural to me as a biblical scholar. It would be awkward if I did not apply the same methods to both records.

Third Nephi is the part of the Book of Mormon which covers, in thirty chapters, the period of A.D. 1–35. It is the one which deals in its own way with the ministry of Christ. Here are the revelations of Christ to the Nephites.

There is the reference to A.D. 34: there was “darkness for the space of three days over the face of the land” “. . . if there was no mistake made by this man [i.e., “the just man who did keep the record”] in the reckoning of our time” (3 Nephi 8:1–3). I take this humble note in the Book of Mormon as a general awareness of the well-known problem concerning the absolute and the relative calculation of the years for the ministry and the death of Jesus. As a biblical scholar I find it intriguing to be in a community whose sacred book states on its title page “And now, if there are faults they are the mistakes of men”—or “humans,” as we say nowadays, or should say. Could it perhaps be agreed that such admissions strengthen the respect for true revelation rather than weaken that respect?

The section of 3 Nephi which we will here deal with (chapters 7–8) transposes the ministry of Jesus into a ministry of Nephi, a man of miracles in the name of Jesus. Thus the power of Jesus’ miracles shines through those chapters. Then comes a section which deals with the three days of darkness; with the thunder and the splitting of the rocks, a transposition of Good Friday and Easter into a cosmic dimension of the events at the death of Jesus Christ. And then in 10:19 it says about Jesus Christ:

Showing his body unto them, and ministering unto them; and an account of his ministry shall be given hereafter. Therefore for this time I make an end of my sayings.

And then in italics, as an insertion, it says:

Jesus Christ did show himself unto the people of Nephi, as the multitude were gathered together in the land Bountiful, and did minister unto them; and on this wise did he show himself unto them.

And this is referring especially to chapters 11 through 26.

It seems important to me that in various ways these chapters are a conscious edition not only of the teaching but of the ministry of Jesus. This revelation, which is, so to say, the New Testament part in the Book of Mormon, places much emphasis on the commission to the Twelve, and a very strong emphasis indeed on baptism and the function of baptism in the community. It begins with a revelation of the risen Lord, wherein the Thomas-text from the Bible, “put your finger here, and see my hands, and put your hand and place it in my side,” is extended—as is often the case in apocryphal and pseudepigraphic material—into a text for which a larger group, in this case the multitude, are invited to participate.

The Twelve receive the admonition that there should from now on be no disputations (as there so often have been in Christendom). With chapter 12 there begins the equivalent of the Sermon on the Mount. Part of that section is addressed to “the Twelve,” and Jesus is seen calling and sending the Twelve. Once more the baptismal emphasis dominates. Baptism is a central phenomenon.

The other distinct emphasis is on “believing in Jesus and his words,” a note absent in the Matthean Sermon on the Mount. “More blessed are they who shall believe in your words” (12:2), is one of the most striking differences perhaps between the Sermon on the Mount and its equivalent in Nephi. In 3 Nephi several times there is the emphasis upon believing, “coming unto Jesus” (12:3). This is one of the persistent differences. Here are saints who are clearly and totally centered around the importance of coming unto Jesus and believing in him. To be sure, Matthew says that Jesus, “seeing the crowds, went up on the mountain, and when he sat down his disciples came to him, . . . and he taught them” (Matthew 5:1). But after that there is no reference in the Sermon on the Mount to the importance of coming to Jesus. In Matthew’s sermon Jesus is a teacher giving no attention to himself, be it as a Messiah or the forerunner of the Messiah or an announcer of secrets. In 3 Nephi the simple scene has been expanded into the theme of coming to him and believing.

Another significant addition (if you call it an addition) is this: While Luke says, “Blessed are those who hunger, for they shall be filled,” and Matthew says, “Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they shall be filled,” both in the Inspired Version of Joseph Smith and in 3 Nephi they are to be “filled with the Holy Spirit.” From my perspective this is a typical expansion of a text (as was Matthew’s expansion on Mark—the targumizing, the Christianizing of a text). But it is also an interesting model, for I see it as an example of the fact that the form in which the biblical material has shaped the mind of Joseph Smith (be it consciously, unconsciously, or subconsciously) is that of the King James Version. The Greek word behind “filled” is chortazo, which means “fill the stomach,” as one fills the stomach of animals, not “fill up” in the sense pleroo, which is the biblical term for being filled with the Holy Spirit. It is rather unnatural to use the Greek chortazo for making the addition “with the Holy Spirit,” but it could easily be done on the basis of the King James Version, which does not distinguish between the two Greek words.

Far more important is the preoccupation of the Nephi tradition with the right understanding of the relation between the Mosaic law and the prophecies and what Jesus might have meant when he said that he had not come in order to destroy the law but to fulfill it. “Think not that I am come to destroy the law or the prophets. I am not come to destroy but to fulfill.” This is identical in Matthew 5:17 and 3 Nephi 12:17. Then 3 Nephi reads “but in me it hath all been fulfilled” (my italics), whereas Matthew speaks in future terms, “till all be fulfilled.”

A most striking difference is found in what follows. In Matthew 5:20:

For I say unto you, That except your righteousness shall exceed the righteousness of the scribes and Pharisees, ye shall in no case enter into the kingdom of heaven.

And in 3 Nephi 12:20:

Therefore come unto me and be ye saved; for verily I say unto you, that except ye shall keep my commandments, which I have commanded you at this time, ye shall in no case enter into the kingdom of heaven. (Italics added.)

(I give the New Testament text as in the King James Version, since the Book of Mormon uses that style of language, and I believe that it can be best understood in its details and as a total phenomenon on the basis of the King James Version.)

These passages prompt some observations that I find to be significant keys to a comparison of the Book of Mormon with the New Testament:

1. The absence of the reference to scribes and Pharisees, to which I shall return.

2. The “come unto me and be saved.” We have already spoken about “come unto me.” Here the word saved is also important.

3. The “verily,” used sparingly in Matthew and abundantly in Johannine speech.

4. The reference to “my commandments,” another Johannine feature. (Cf. however Matthew 28:20.)

5. The admonishment “to keep” these commandments of Jesus.

6. The reference to “this time.”

All these features by which 3 Nephi differs from Matthew point in the direction toward that which we shall call a Johannine Jesus, the revealed revealer who points to himself and to faith in and obedience to him as the message. In the Matthean Sermon on the Mount, Jesus is pictured rather as a teacher of righteousness, basing his teaching on the law and the prophets, scolding the superficiality and foibles of the religionists of his time, proclaiming the will of God and not the glories of himself. Nor does the Sermon on the Mount specifically speak of “being saved.”

The saying about the salt of the earth has preceded the passage just discussed. It shows some difference from the Matthean version whereby the parabolic nature of the saying is broken. We are told in 3 Nephi, “I give unto you to be the salt of the earth; but if the salt shall lose its savor wherewith shall the earth be salted?” (verse 13). The emphasis on the sending of the disciples is strengthened, but the clear parabolic style is ruined by the odd idea that it would be good for the earth to “be salted.” What farmer would like that?

We could also note that the tendency is toward interpretative and clarifying expansion. As twentieth-century Bible readers, we are quite familiar with this tendency because of the New English Bible. This, like many of the other contemporary translations, is anxious to be clear, anxious to function well for the individual reader in his isolation. It leaves few sayings ambiguous or requiring interpretation. “In the beginning was the Word” (King James Version and Revised Standard Version) becomes “When all things began, the Word already was” (New English Bible). I call this tendency targumic, referring to the beautiful, clarifying, and updated Aramaic translations of the Hebrew Bible. The relation between Matthew and 3 Nephi looks to me like one of targumizing.

One more example, Matthew 5:23–24, reads:

Therefore if thou bring thy gift to the altar, and there rememberest that thy brother hath aught against thee; <> Leave there thy gift before the altar, and go thy way; first be reconciled to thy brother, and then come and offer thy gift. (Italics added.)

And in 3 Nephi 12:23–24 we read:

Therefore, if ye shall come unto me, or shall desire to come unto me, and rememberest that thy brother hath aught against thee—

Go thy way unto thy brother, and first be reconciled to thy brother, and then come unto me with full purpose of heart, and I will receive you. (Italics added.)

In 3 Nephi the altar is gone, replaced by Jesus (me), and since the issue is “to come unto me,” and that “with full purpose of heart,” and since the concrete example in Jesus’ words is gone, it is natural to expand the admonition to those who desire to come—a gracious expansion toward the future. Thus the simple teaching of Jesus about reconciliation in the community, which has no Christological note, has now become absorbed in the pervasively Christ-centered pattern of 3 Nephi: “Come unto me—with full purpose of heart—and I will receive you.”

As I try to cover a few more of the distinct differences, let me point to another feature that must strike us all. It is one of style. I refer to the abundance of the introductory words “verily” and “verily, verily,” the Greek and Hebrew “amen.” There are nineteen “verily” and twenty-five “verily, verily” in 3 Nephi 11–27 (there are very few in the rest of the Book of Mormon). By this stylistic device the teaching of Jesus is actually changed from moral and religious teaching into proclamation and explicit revelation of divine truth. The whole speech has thereby changed its character.

There are also the typical targumic and expansive phenomena. I am not speaking so much of how the accounts in Samuel and Kings look when retold in Chronicles, although that is a kind of parallel to what is going on in the Book of Mormon. I am more interested in the implicit rationalism of the expansions. You remember the saying, “Verily I say unto you, thou shalt by no means come out from that prison till thou hast paid the uttermost farthing” (Matthew 5:26). Now, the rationalizing expansion is this: “and while ye are in prison can ye pay even one senine?” (3 Nephi 12:26). On reflection, it is clear that it is awfully hard to come up with cash while you are in prison. But that reflection breaks the structure and blurs the point of the parabolic saying.

Third Nephi has a drastic recasting of what in Matthew 5:27–30 is the harsh sharpening of the commandment of adultery—the looking at a woman in lust and the plucking out of the offending eye and cutting off the offending right hand. In 3 Nephi no specific offense is mentioned; and the graphic and suggestive teaching is replaced by reference to a commandment and is recast in generalized and Christianized form:

Behold, I give unto you a commandment, that ye suffer none of these things to enter into your heart; for it is better that ye should deny yourselves of these things, wherein ye will take up your cross, than that ye should be cast into hell. (3 Nephi 12:29–30.)

We also note the absence of Jerusalem (Matthew 5:35) in the saying about oaths. I think this is consistent with another element in the Book of Mormon, and one of importance to us if we want to understand its place and function in the continuum of holy scriptures.

For that purpose it is instructive to think of the Septuagint (LXX), i.e., the Jewish translation of the Old Testament into Greek. In that translation geographical names were often transformed into words with conceptual meaning (for example, Rama became “on high”) or replaced by updating equivalents. Thus geography was often suppressed or transformed. As W. D. Davies points out in his essay in this volume, the Book of Mormon has a great fascination with geography. At this point and elsewhere in the material now under consideration, however, the tendency is in the opposite direction: geographical and historical and concrete elements are suppressed or flattened out. Specifics like “altar” and “temple” and “Jerusalem” are gone. The revealer and his commandments are dehistoricized and the address to his Christian followers is made more clear.

The majestic final section in Matthew 5 and 3 Nephi 12 shows some significant differences. For some reason the reference to him “who lets his rain fall over both just and unjust” is not there. I combine that absence with the fact that, while the Book of Mormon excels in biblical style, in it one of the most delightful and striking stylistic features is missing, or at least is less prominent. I refer to the parallelismus membrorum, i.e., saying one thing by two analogous expressions: “he maketh his sun to rise on the evil and on the good, and sendeth rain on the just and on the unjust” (Matthew 5:45). That style of parallelism is not to the same extent part of the biblical daughter, the Book of Mormon. It may be of interest to ask why that is so.

In any case, in the instance under discussion the doubleness is not contained. Instead, what we have is a more doctrinal and Christological touch as to “those things which were of old time, which were under the law” (3 Nephi 12:46). Those things are now all fulfilled “in me.” And: “Old things are done away, and all things have become new” (12:47). Thus 3 Nephi once again makes sure that the theme from 12:18 shall be the focus of the whole; and we know how important that is, since the whole of chapter 15 will expand at length on this matter.

The chapter ends by giving the mighty word of Jesus a Christological accent. While Matthew has, “Be ye therefore perfect, even as your Father which is in heaven is perfect,” 3 Nephi’s Christologized text reads, “Therefore I would that ye should be perfect even as I, or your Father who is in heaven is perfect” (12:48).

In the thirteenth chapter of 3 Nephi (Matthew 6), the clarification and especially the commandment-clarification is at work. In the Sermon on the Mount the statement begins, “Take heed that ye do not your alms before men, to be seen of them: otherwise ye have no reward of your Father which is in heaven” (Matthew 6:1). That is, Do not carry out your almsgiving in order to receive praise. It is interesting that Nephi does not see Jesus as a teacher in his community who takes the ongoing requirements of the Torah for granted and then makes comments on it. In 3 Nephi 13:1 we read: “Verily, verily, I say that I would that ye should do alms unto the poor.” To Jesus (and Matthew) the commandment and practice was given in the Torah. It was not his commandment. Only the warning against hypocrisy was his. But in 3 Nephi it becomes Jesus’ commandment—like the “new commandment” in John. It is as if one were not satisfied unless it came from Jesus; one is not quite satisfied with just a comment of Jesus on the practice of alms. And that sets very much of the tone of the chapter.

I come now to the most important and interesting difference that I have found in looking at these texts, and that is that in the Lord’s Prayer (Matthew 6:9–15; 3 Nephi 13:9–13), the prayer about the coming of the kingdom and the prayer about the bread are not found in 3 Nephi. There the Lord’s Prayer reads: “Our Father who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name. Thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven. And forgive us our debts . . .” and so forth. I understand that this raises questions which are well known among Mormon scholars.

Those verses about the daily bread and the coming of the kingdom are contained in the Inspired Version by Joseph Smith. So the question is why they are not in 3 Nephi. As to the reference to the kingdom, I would suspect that the setting here given in 3 Nephi, with the revelation of Jesus Christ to the Nephites, and perhaps the self-understanding of the Church as that of Latter-day Saints, suggests it to be somehow improper to pray for the coming of the kingdom. By a preliminary study of the concordance to the Book of Mormon I can find no single passage where the terms kingdom of God, kingdom of heaven, or kingdom are used in the typical synoptic way of “the coming of the kingdom.” It seems that the kingdom-language is used in other—also biblical—ways in the Book of Mormon: “Entering into the kingdom,” “dwell in the kingdom,” “received into the kingdom,” “inherit the kingdom,” “sit down in the kingdom,” and also the less biblical usage, “saved in the kingdom.” “. . . The kingdom of heaven is soon at hand,” we are told in, for example, Alma 5:28, but the idea of its coming is not found, so far as I can see, in the Book of Mormon.

But so rich is the LDS community that there is another book, or more than one, that you honor as scripture; and in section 65 of the Doctrine and Covenants there is a revelation to Joseph Smith (1831) which is very much in the style of the Lord’s Prayer. Its context is of interest, as it includes “Yea, a voice crying—Prepare ye the way of the Lord, prepare ye the supper of the Lamb, make ready for the Bridegroom” (verse 3). In that eschatological setting come the words: “Call upon the Lord, that his kingdom may go forth upon the earth, that the inhabitants thereof may receive it, and be prepared for the days to come, in which the Son of Man shall come down from heaven, clothed in the brightness of his glory, to meet the kingdom of God which is set up on the earth” (verse 5). Thus here the Son of Man comes down to the kingdom of God which is already established on earth. And hence it wouldn’t be natural to pray for the coming of the kingdom. The revelation continues: “Wherefore, may the kingdom of God go forth, that the kingdom of heaven may come” (verse 6). This distinction between the kingdom of God and the kingdom of heaven seems to be important. The kingdom of God is the mission that is “going forth upon the earth.” The kingdom of heaven is the consummation, and is to come.

It could, of course, be argued on the basis of these observations that the Lord’s Prayer in 3 Nephi could have read: “Let the kingdom of heaven come,” and that such a usage would be the more appropriate since Matthew uses this term almost exclusively—rather than kingdom of God. But I tend to think that this distinction between the kingdom of God as present and the kingdom of heaven as future does not significantly inform the kingdom-language of the Book of Mormon. Or the prayer could have read, “Let thy kingdom go forth.” But as the text stands, it is perhaps more reasonable to assume that neither of those uses of the kingdom-language fits into the basic perspective of the language of the Book of Mormon when it comes to a prayer of Jesus.

Why the prayer for bread is missing in the 3 Nephi version is not easy to explain, except that there is a marked tendency away from material things. In 3 Nephi 18 and 20 we have substantial elements of two whole chapters which deal with questions of the bread (and wine) in miraculous and sacramental terms.

It could, of course, be argued that the original meaning of the Greek arton ton epiousion and its Aramaic base, which KJV renders by “daily bread,” actually refers to the “day of the future,” i.e., the Messianic Banquet, and this is miraculous, sacramental and eschatological. But that is another question, since the biblical material behind the Book of Mormon strikes me as being in the form of the KJV.

That concludes my passage-by-passage comparison, although points similar to the ones I have made could be demonstrated again and again throughout the three chapters of the Sermon on the Mount. Suffice it to add that the Matthew ending, which refers to how Jesus “taught them as one having authority, and not as the scribes,” is missing in 3 Nephi, or rather is expanded into a whole chapter (3 Nephi 15), a revelatory speech about how the law of Moses is superseded and the giver of the law fulfills the law. We shall return later to the significance of the absence of the scribes and Pharisees in the Nephi edition of the Sermon on the Mount. Furthermore, 3 Nephi 15 also relates this speech to “the sheep of another fold,” and that in a language reminiscent of John 10.

Allow me to reflect with you also on the main points in the chapters of 3 Nephi which follow those already discussed, for I see them as a significant summary of the ministry and teaching of Jesus. The reflection on shepherd and sheep continues, and leads to extensive quotations from Isaiah, especially Isaiah 52. In chapter 17 we find many things that remind the Bible reader of John 14–17, i.e., the farewell speeches: “I go unto the Father”; the delay and the tarrying, “a little while, and ye shall not see me: and again, a little while, and ye shall see me.”

In chapter 17 we find also “a marvelous and touching scene,” as the chapter heading so rightly describes it. It is marvelous partly because of the very dominant role of children. And as you analyze textually that passage where the children figure so prominently, it is very clear that it is related to “Suffer the little children to come unto me.” There is a very conscious children-dimension to this event.

Then in chapter 18 you have the sacramental bread and wine. You have it with an introduction in the style of John 4, the disciples having gone for food while Jesus is sitting there. You have the church disciplinary injunction of not eating unworthily (cf. 1 Corinthians 11). And in chapter 19, you have a Pentecost where the whole tone of the chapter comes from the style and terms of John 17, the high-priestly prayer of Jesus. This leads into prophecies, mainly from Isaiah and Malachi.

Now, I want to ask myself and you: What is the picture of Jesus and his ministry that emerges out of all this—out of the Sermon on the Mount particularly, but also out of this whole section in 3 Nephi, and out of the whole of 3 Nephi?

There can be no doubt about some of the answers. The most striking feature that I discern when I compare 3 Nephi with Matthew or with the three synoptic Gospels is the transposition into Johannine style. The Gospel of John, as you know, is famous for the fact that to a large extent it consists of revelatory speeches or revelatory discourses. Most analysts of the Gospel of John see in it two distinct types of material or sources. The signs, the seven signs, are often more miraculous than they are in the synoptics, so that the blind is born blind; the rescue of the disciples who were in the boat in storm being heightened by that strange saying, “they were glad to take him into the boat, and immediately the boat was at the land . . .” (John 6:21). Everything gets a little more miraculous. Another example is the healing of the centurion’s son. In the Gospel of John we are told that the healing occurred exactly at the time when Jesus said, “Your son will live” (John 4:53). It may be of interest to compare the synoptics and 3 Nephi on this point also. Perhaps also here 3 Nephi is akin to John. “When God is at work you can never understate the case” seems to be the theological principle at work to the greater glory of God.

Be that as it may, the real analogy between the Johannine Jesus and the Jesus of 3 Nephi is found in the style of discourse. The message in both is that he is the Redeemer, the Savior, “I Am”: “I am the life, I am the way, I am the seed that falls into the ground. Come unto me. Believe in me.” In the synoptic tradition, however,—of which the Sermon on the Mount is a part—Jesus does not speak about himself. He speaks about the kingdom. But in the Gospel of John every symbol, every image that occurs about the kingdom is transposed into an image for Jesus. Jesus tells stories about the shepherd and the sheep. But in John, Jesus is the Good Shepherd. Jesus tells stories about the seed of the kingdom. But in John, Jesus is the seed. And as I have shown, the tendency toward the centering around faith in Jesus is perhaps the most striking tendency we find when comparing Matthew and 3 Nephi. That is also the dominant note in John.

Another feature we isolated was the transposition into revelatory speech style, which also is that of John’s, including the “verily, verily” and “behold, behold”—all part of the revelatory speech style. The emphasis on faith in Jesus is not a theme in the synoptics and especially not in the Sermon on the Mount. In the synoptic Gospels one believes in God and trusts in the coming of the kingdom.

This transposition is in keeping with the whole image of Jesus’ ministry in 3 Nephi. It is not only a matter of the genre of revelatory speech. It is the very absorbing of Jesus into the image of a Redeemer and lifting him out of history into a more timeless space as the Revealed Revealer.

Thus let me summarize my observations by saying that the image of Jesus in the whole of 3 Nephi, and even more in the portion giving the Sermon on the Mount, is that of a revealer, stressing faith “in me” rather than in what is right according to God’s will for his people and his creation.

Jesus is not any longer a teacher in the ongoing community of God’s people correcting the foibles and the misconceptions of religious people. Let me exemplify that in a very precise manner. During this symposium W. D. Davies stated that there is no other Christian community or community out of the Judeao-Christian tradition which has as positive and non-anti-Semitic ways of speaking about the Jews as have the Mormons. I found his case convincing. In my own observations I have noticed that the word Pharisee does not occur in the Book of Mormon. The Christian habit of using the term Pharisees as the symbol for the wrong attitude toward God is not part of the Mormon tradition. That is truly refreshing and welcome and unique.

Also in our comparison of the Sermon on the Mount and 3 Nephi we have seen this disappearance of the scribes and Pharisees (e.g., Matthew 5:20, 3 Nephi 12:20; Matthew 7:28–29,3 Nephi 15:1–2). It is worth noting, however, how this gain has been bought at a very high price; for this disappearance of the Pharisees and scribes leads to the obliteration of one of the most significant elements in the synoptic image of Jesus. I refer to Jesus’ persistent critique of the foibles of religious people. This intrareligious critique strikes me as indispensable in the picture of Jesus. It is actually an integral element in the very tradition of the Pharisees themselves, a precious confirmation of the prophetic tradition.

The interesting thing is that once this critique of the foibles and pitfalls of pious and devoted people is gone, and once Jesus is made into a revealer demanding “faith in me,” the internal criticism in the religious community has disappeared from the image of Jesus, and perhaps from the community itself. Jesus has become the revealer demanding “faith in me.” He is not any more the wise teacher as to what might be morally or religiously right in the sight of God.

Jesus’ scathing and promising words about “the first becoming the last and the last becoming the first” and about the foibles and pitfalls of prayers, alms and fasting have been transformed into commandments, moral and otherwise. In becoming a revealer image, the image of Jesus has also become the founder of a church and the promulgator of its ordinances.

Let me then summarize my observations. I have spoken out of the kind of perspective with which biblical scholars look at biblical texts. I have applied standard methods of historical critics, redaction criticism, and genre criticism. From such perspectives it seems very clear that the Book of Mormon belongs to and shows many of the typical signs of the Targums and the pseudepigraphic recasting of biblical material. The targumic tendencies are those of clarifying and actualizing translations, usually by expansion and more specific application to the need and situation of the community. The pseudepigraphic, both apocalyptic and didactic, tend to fill out the gaps in our knowledge about sacred events, truths, and predictions. They may be overtly revelatory or under the authority of the ancient greats: Enoch, the patriarchs, the apostles, or, in the case of the Essenes, under the authority of the Teacher of Righteousness in a community which referred to its members as latter-day saints. Such are in the style and thematic vocabulary of the biblical writings. It is obvious to me that the Book of Mormon stands within both of these traditions if considered as a phenomenon of religious texts.

I would further see the Book of Mormon as an exponent of one of the striking tendencies in pseudepigraphic literature. I refer to the hunger for further revelation, the insatiable hunger for knowing more than has been revealed so far.

That can be a beautiful thing, but it has its risks and its theological costs. You may have heard about the preacher who preached about the gnashing of teeth in hell. And one of the parishioners said, “But what about us who have lost our teeth?” And the preacher answered, “Teeth will be provided.” Preachers think they have to have an answer, otherwise they are letting the Bible, Jesus and God down. The apocryphal and pseudepigraphical writings, when looked at from the outside, are driven by this horror vacui. The gaps of knowledge have to be filled in somehow. Take, for example, all the various apocryphal gospels about the birth of Jesus. There is no end to the information given about all the gynecological details of the conception and the birth of Jesus. The hunger for knowledge is enormous. Actually, the Gospel of Luke takes the first step in that direction. And we are all familiar with how, out of the prophecies of Daniel and the book of Revelation, there are so many open questions, and the hunger to know more engenders interpretations and new revelations.

One can, of course, think differently about these matters. One can see it all as an authentic need, authentically filled by revelations and by religious geniuses who by the grace of God have had visions and the capacity of interpreting them—as the Gospels of Luke and of Matthew began to fill in the gaps about the birth of Jesus. For neither Paul nor Mark nor John nor any of the other New Testament writers seem to have known or cared about those things. But the hunger is to know more, and more precisely, to lead either to the collecting of traditions or to revelations so as to fill out the picture. For this is a powerful law of religious and human existence. There is Emanuel Swedenborg, and there is Ellen Gould White, and there is Mary Baker Eddy, and there is the Reverend Moon who gives to Christianity not a United States transplanting, as does the Book of Mormon, but a Korean transplanting. The public relations by which the Moon movement is seeking respectability is of the twentieth-century variety, and perhaps not wholly of the Spirit. But this should not blind us to the phenomenological similarities between all these movements. It is of great importance to reflect phenomenologically on such new outpourings of revelation, and in the case of Mormons and Moonies the transplantation from continent to continent is of special interest in an expanding and shrinking world.

Let me then finally reflect on how we more canonical Christians live with our more limited knowledge. For I guess that I personally am a minimalist. When I am asked about further data on resurrection, preexistence, and so forth, I like Paul’s answer. “But some one will ask: How are the dead raised? With what kind of body do they come?” His answer is not an answer, but he says, “You fools,” and he just refers to God’s power to do a new thing about which such speculations are futile (1 Corinthians 15:35 ff). And one of the humbly glorious things in the Bible is Jesus’ own limits in these matters—there are things that nobody knows, “not even the Son” (Mark 13:32). Here we have an ascetic attitude instead of the insatiable hunger to know more. Perhaps such a comment is irrelevant to those who are gratefully convinced of additional revelation in and through Joseph Smith or otherwise. But as I look at the whole spectrum of God’s menagerie of humankind and its history, including its religious history, I think it is important to reflect on the limits as well as the glories of the hunger for and joy in additional information.

Sometimes I feel the weight of a famous quote from the prophet Micah which speaks deeply to me. That quote came to my mind when I studied the Sermon on the Mount. There Luke reads, “Blessed are you that hunger” (Luke 6:21). Matthew reads, “Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness” (Matthew 5:6). In the Book of Mormon the saying has moved away from both the hunger of the stomach and the thirst for justice to the religious realm of the Spirit (3 Nephi 12:6). And there is nothing wrong in that; it is our common Christian tradition and experience to widen and deepen the meaning of holy words. But let us never forget that quotation from Micah which reads, “For what else does the Lord require of you but to do justice, to love kindness, and to walk humbly before your God” (Micah 6:8). For there is sometimes too much glitter in the Christmas tree.