American Society and the Mormon Community

Robert N. Bellah

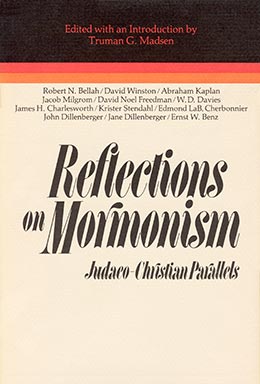

Robert N. Bellah, “American Society and the Mormon Community, in Reflections on Mormonism: Judaeo-Christian Parallels, ed. Truman G. Madsen (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1978), 1–12.

The late Swedish theologian Nels F. S. Ferre once observed that he had met committed individuals but until he saw the Mormons he had never known a committed community. Community is a rather faddish word among sociologists of religion today, as it is at every level of a radically disrupted society. It comes in the wake of a notion that anything “established” is for that reason suspect. The Mormon Church has been compared to a variety of tightly organized systems: to the (supposedly) monolithic Catholic hierarchy; to types of social usurpers; to the major industrial corporations; and even to the German army.

Robert Bellah is “one of a kind” in this symposium setting. The other participants can be classified as experts in “religious studies,” historical, theological and philosophical. Bellah is better known as a scientist and sociologist in his approach. Over the years his methodology has developed away from the hard empirical behavioral studies, modeled after the positivists. He now views society as a “text to be studied.” He brings to this symposium his notes and conclusions on a careful three-month participative study of a Mormon community in New Mexico. His approach is not simply to social interrelationships but to the valuational commitments that lie behind them. And his paper is a deliberate effort to relate and compare the Mormon ethos with the American ethos.

T. G. M.

The issues that I want to raise in this brief paper are central and serious, not only for the Mormon community but for all Americans. They bear on our fate religiously and as a nation.

Twenty-five years ago I spent three months in the Mormon community of Ramah, New Mexico, forty-five miles south of Gallup. The research I did was part of my graduate field work requirement. Thomas O’Dea was introduced to Mormonism as a member of the same research project with which I was involved. Although that exposure was relatively brief in terms of actually living in the community, it did spark an interest which at the time led to months of reading on the subject of Mormon history and religion and, while I have not been able to specialize to the degree that O’Dea did, I have continued to be interested in Mormon sociology in subsequent years. In 1954 I wrote a manuscript of some sixty pages describing Ramah in the context of Mormon belief and practice, a paper I will cite below.

I turned, however, rather quickly to the work on Japanese religion which had already begun before the trip to Ramah. Since then I have been concerned with religion and society in a number of cultures not only in East Asia but in the Middle East. There are a series of potential comparisons that would put Mormonism in comparative perspective with Asian religions, but that is not the context I am concerned with here.

The immediate reference point for this paper comes from a deepening involvement with the role of religion in American life which began when I published a piece in Daedalus in 1967 entitled “Civil Religion in America.” In 1975 I published a book called The Broken Covenant, in which I tried to spell out some of the problems of biblical religion in American history. I have been concerned with how some of the themes that John Dillenberger discusses as being integral to English Christianity, even before the American experience, have worked themselves out in the American context—particularly exodus, promised land, and the kingdom of God—first of all in the colonies, and perhaps archetypically in colonial Massachusetts, but later in the American Republic itself; and certainly, as John Dillenberger indicates, in Mormonism with its own special version of these very deep-seated biblical themes. I have also been concerned with the way in which these themes relate to or conflict with other themes. For American culture, however much of it may be rooted ultimately in a religious and a biblical inspiration, has many strands and many other notes which influence the way we think. I have been particularly interested in one major strand which goes back almost as early as the biblical in our history—namely, radical individualism and utilitarianism, the notion that human beings are motivated above all by self-interest and that society is essentially a mechanism to gratify the interest of individuals with as little conflict as possible.

The biblical version of what it is to be human and the individualistic utilitarian version coexisted in the minds of the same people often without a sense that there was a deep conflict. At times there was covert or overt conflict reaching some degree of intensity. I have come to feel that these things which have existed in our culture virtually from the beginning—biblical religion from settlement; what I am calling utilitarian individualism from the eighteenth century—still have much to teach us about where we are today as we have pursued the consequences of these values and ideals. It is my feeling that the Mormon experiment, which, like every other group in America, has been influenced by both of these strands, is a peculiarly instructive example. It heightens and underlines lessons which can be learned from many other groups. I would like to share what knowledge I have including the first-hand knowledge of the Mormon community in which I lived, to show what the relevance might be.

I, with John Dillenberger, would perhaps begin a look at Mormonism in the context of religion and society in America generally, with the tradition of English Christianity and more precisely with the example of Puritan New England in mind. This parallel has been pointed out many times, but nowhere more vividly than in a few sentences by A. Leland Jamison.

The historical evolution of the Mormons furnishes the most thrilling chapter in the whole chronicle of American religion. By comparison, the adventures of the settlers in New England seem tame. It is noteworthy, however, that Puritans and Mormons followed the same star of hope and aspiration: both aimed to build the Kingdom of God in America, to establish Zion in the wilderness. Of the two groups, the Mormons more nearly attained the ideal, at least in terms of their own conception of what the Kingdom could and should be. The brigades fired by Smith’s faith and guided by Brigham Young’s iron will outstripped their foes, mastered hostile nature, and fashioned a genuine theocracy which ruled a numerous multitude for nearly half a century, certainly down to the acquisition of statehood. It required no outlandish stretching of the pious imagination to find the telling analogy to their saga in the Hebrew exodus: out of bondage they were led by a Moses and a Joshua through wilderness and war into a Promised Land; they were a Chosen People, in possession of a new Law, and commissioned by Almighty God himself to create the perfect society in a recalcitrant world—and ultimately to convert that world to their own scheme of things. [1]

The interesting thing about the set of parallelisms is that almost everything that links the Puritans and the Mormons is also true of the American experiment itself. All of those analogies have been used in the life of our republic.

A number of excellent studies of early New England towns have recently appeared and it would be instructive to compare seventeenth-century Dedham, Massachusetts, to which a book was recently dedicated, with the community in which I lived—Ramah, New Mexico. Both were, to an important degree, utopian communities, bodying forth in visible form a new kind of society in which religious revelation had provided the controlling vision. Both stood in marked contrast to the larger society growing up around them, a society seemingly based on other principles, determined to leave behind the religious vision. Other work on New England towns has shown that the Puritan utopian vision survived in the towns in Massachusetts long into the eighteenth century, when the urban culture was taking on a very different and a very much more secular note.

There are some striking parallels in content, in spite of differences in mode of expression, I would suggest, between the self-conceptions of these groups, even separated by several centuries. Most notably one of the things that links the early Puritans in Massachusetts and the Mormons through much of their history has been the fact that they had a strongly social vision. America is supposed to be the land of radical individualism, and indeed it is. Both Puritans and Mormons have had profound respect for the individual and for the God-given autonomy of the individual. But neither the Puritans nor Mormonism, nor most of the other religious traditions in America, have ever taken the isolated individual as the final good. I would like to turn to a passage which I think is fundamental for understanding one aspect of the whole American project. It was spoken by John Winthrop, the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony (he could be called the “Brigham Young” of the Puritans), in a sermon called “The Model of Christian Charity,” they had landed. These words became a kind of charter for the communities such as Dedham, Massachusetts, that would be built in succeeding decades. Nothing could be clearer than the strongly social vision in these words:

Now the onely way to avoyde this shipwracke and to provide for our posterity is to followe the Counsell of Micah, to doe Justly, to love mercy, to walke humbly with our God. For this end, wee must be knitt together in this worke as one man, wee must entertaine each other in brotherly affeccion, wee must be willing to abridge our selves of our superfluities, for the supply of others necessities, wee must uphold a familiar Commerce together in all meekness, gentlenes, patience and liberallity, wee must delight in each other, make others Condicions our owne, rejoyce together, allwayes haveing before our eyes our Commission and Community in the worke, our Community as members of the same body, soe shall wee keepe the unitie of the spirit in the bond of peace, the Lord will be our God and delight to dwell among us as his owne people and will commaund a blessing upon is in all our wayes, soe that wee shall see much more of his wisdome, power, goodnes and truthe than formerly wee have beene acquainted with.

And he goes on to conclude:

Beloved there is now sett before us life, and good, deathe and evill in that wee are Commaunded this day to love the Lord our God, and to love one another, to walke in his wayes and to keepe his Commaundments and his Ordinance, and his lawes, and the Articles of our Covenant with hi m that wee may live and be multiplied, and that the Lord our God may blesse us in the land whither we goe to possesse it: But if our heartes shall turne away soe that wee will not obey, but shall be seduced and worship . . . other Gods, our pleasures, and proffitts, and serve them; it is propounded unto us this day, wee shall surely perishe out of the good Land whither wee passe over this vast Sea to possesse it . . . [2]

Those words of Micah (Micah 6:8) were favorite words of Brigham Young. Much of that sermon of Winthrop could virtually have been preached by Brigham Young because it is so close to the Mormon conception of unity and social responsibility. As a parallel to John Winthrop, I would like to turn to some notes that I took in 1953 of a talk given by an official of the stake who was speaking in Ramah. I think they show how a vision very close to John Winthrop was alive in that community at that time.

There is too much thinking of self and not enough of others. Nobody is going to be saved all by himself. He will be saved with his family and neighbors and friends or not at all. Mormons believe in helping others. If a man works hard and tries to make a go of it, it is up to others to help him all they can and see that he gets along in life. Children should help their parents and not simply demand all the time. They should get up earlier and take over chores from their parents. I know it is discouraging when it is so dry. I wish I had sold more of my cattle. But we should be discouraged, because if we keep the commandments of the Lord we will be blessed and if we don’t keep them we will surely lose this land and it will be given to another people.

John Winthrop’s vision of society based on what he called the ligaments of love, was not the only vision of society to affect colonial America or to be present in our history subsequently. Already in the late seventeenth century John Locke wrote that the ends of society are not love or justice but, as he put it,

The great and chief end therefore, of Mens uniting into Commonwealths, and putting themselves under Government, is the Preservation of their Property. [3]

And again:

The commonwealth seems to me to be a society of men constituted only for the procuring, preserving, and advancing of their own civil interests.

Civil interests I call life, liberty, health, and indolency of body; and the possession of outward things, such as money, lands, houses, furniture, and the like. [4]

There was a New Yorker cartoon a few years ago which showed two Pilgrims on board one of the ships that took them to Massachusetts. One says to the other: “My first aim is religious freedom. After that I’m thinking of going into real estate.” The great biblical conception of human community and the notion that we are essentially to look out for number one have coexisted in American for a long time. I even suspect that it would be possible to imagine a cartoon depicting a couple of Mormon brothers in that caravan crossing the high plains in which such ironic conversation might have been held.

These two visions, the communitarian vision of society as knit together by the bonds of love and the individualist vision of society existing only for the self-interest of individuals, have persisted together from the beginning. They even have had, as Max Weber pointed out, a symbiotic relation. Individuals raised with the nurturing support of religious community have often been strong enough to pursue their own interest in the economic or political spheres with remarkable effectiveness and to build a society with a great deal of wealth and power along the way.

Both Puritans and Mormons have become successful in the world beyond all expectations, often with strange consequences for their original religious commitments. But in the late years of the twentieth century the destructive consequences of the pattern of what I am calling utilitarian individualism are becoming increasingly clear. The single-minded devotion to individual and national success measured only in terms of wealth and power has led to a society in which all of what might be called the soft structures (those structures concerned with human motivation—the family, the school, the religious bodies, the neighborhood, the community) have been threatened and have found themselves in disarray. This process is self-destructive, for the very social and motivational (I think ultimately religious) basis of even our worldly success is seriously eroded. The texture of our society is weakening, and the possibility of meeting the enormous challenges of the world in which we live—of technology out of control, or ecological disturbances of unknown proportions, of worldwide hunger and massive political disturbance which threaten the stability of every nation, not least our own—seems even more unlikely. The question is where we have the social resources to meet those challenges, particularly in view of the undermining of precisely those structures of human motivation which have been behind our success.

It is perhaps true that the crisis we face is above all a crisis of success, of having achieved so much in material things beyond that our grandfathers and grandmothers might ever have imagined. And yet we seem now to be faced with deepening problems which our grandparents could hardly have dreamed of. The crisis of success occurs because we have attained the things we chose to put first among our values: wealth and power. And now we must pay the price.

In this context, looking at Ramah, New Mexico, in 1953 (I don’t know what it is like now; that would be fascinating to discover) there was an extraordinary vitality of collective life that was by and large autonomous in the sense that most of the things that went on were in the hands of the people themselves. Most of the functions in that community were carried out by voluntary association, by getting together with fellow members of the community (which, because it was almost exclusively a Mormon community, meant fellow members of the Mormon Church) to meet whatever needs the community had. Of course the community was tied in with larger structures, with the Church and its headquarters in Salt Lake City, with the state, with the nation. Relative to most Americans this was a society in which the family and the local Church organizations carried out economic, political, recreational, and other functions, which for most of us living in Urban America are carried out in highly impersonal anonymous ways by large bureaucratic structures.

The basic Mormon understanding of life was clearly the ground plan for daily existence in that community. The plan of salvation, as it was understood, dominated the lives of the people and gave meaning and coherence to everything they did. These were hard-working people. They were dedicated, as Mormons usually have been and as Calvinist Protestants have been, to the value of work. It is notable, through, that success, in the general American meaning of the term, that is, of a primary concern with getting ahead materially and in the occupational sphere, was not the overriding preoccupation of this community. Indeed, many members of the community had to support their families by working away from it, but because of the rich life that their families enjoyed in Ramah they did not want to move away. They were willing to sacrifice economic advancement to that end. I would say that the primary occupational goal in Ramah was not success in its standard American middle-class form, but what they called “making a living”—enough to get along with, to live comfortably. In concrete terms this meant a steady job with a stable income. What they most preferred, of course, was a small ranch which would allow them to stay in the community full time. But the economic ideal was related to the primary orientation of living in a close community with a deep attachment to land and neighbors which could provide the kind of life that they felt brought meaning and value to them. And often the decision to opt for that life meant sacrifice, it meant hardship, it meant struggling. In rural New Mexico where rain was uncertain, life was often lived close to the margin. The challenges were deep but they were accepted joyfully as part of the character building that goes into human life.

The community was valued as a place where people cared about each other, were concerned for each other. I don’t want to give the impression that there were no tensions, no gossip, no family factions as there are in all small communities, Mormon or otherwise, because all those things were there. And yet the quality of life was extraordinarily fulfilling within its own terms. Certainly one of the things that seemed to be most important to the people of Ramah and that I heard verbalized in many different contexts was that life was to be lived with joy. There was a weekly dance which opened and closed with a prayer. They had a weekly movie because they didn’t want the young people to go to Gallup (where there were various possibilities that they would just as soon avoid). Almost every family had one or more members who played instruments, and they loved to sing. There was a great deal of music in this community. There were even six or seven men who painted, though I don’t know whether they would have met Jane Dillenberger’s standards.

One of the things that the community greatly enjoyed was the rodeo which they put on once a year and which, like everything else in the community, was sponsored by the Church. One frequently heard the statement, “We have a good time in Ramah.” But to me the most impressive thing about that community, and I am probably overly idealizing it some twenty-five years later, is the degree to which it seemed to embody a very deep aspiration in American life which through much of our history we have failed to actualize, namely, a community in which most of what went on was done by the people who participated in that community. I figured out that for 250 people (of course a certain percentage of them were young children) there were seventy offices, mainly Church offices. Most of the adults in that community, male and female, had active responsibilities that they felt were contributing to each other and to causes in the larger world. The alienated, isolated individual was not a feature of Ramah in 1953.

The peculiar Mormon emphasis on achievement and work was certainly strong. Work meant to them not simply a job; Church work and community work were also part of the so-called work ethic (a rather debased idea, I think, in recent American usage). Work, then, took place in the context of a religious commitment that gave meaning to the whole life; that of course is general in Mormonism. Some of the older people, and particularly one older woman who was the sort of unofficial resident theologian, spoke about the Bible with real joy. Pride in work, in a life of adequate labor, combined with the feeling that one is basically accepted in one’s family and community and that one’s life has meaning in terms of a universal scheme of things, is, indeed, an extraordinary kind of reward. While one would have to say, as in the case of most things human, that that ideal was approached and never totally fulfilled, the approach was a close one.

I hold this community up not because I think it is a viable answer to our problems—we cannot simply return to small rural communities like Ramah. The world would not let us, even if we wished to. Indeed, I am not sure whether Ramah is even recognizable in terms of what it was twenty-five years ago. But I do believe that unless, in some appropriate form, that religious vision of a loving community can be revivified today, it seems to me that our future is not very promising. Atomistic individuals, on the one hand, and tyrannical bureaucracies (here I mean not only government but also the great corporations which dominate much of our lives and make political decisions that we have no effective influence on) will be all that remain. These are the two sides of the same problem. Isolated individuals motivated not by love and loyalty but by desire and fear—desire for material rewards, and fear of being deprived of them—such individuals are the perfect material for tyranny. If there is to be an alternative to what seems to the drift of our society, I cannot see where else to look but to our religious communities. But often when we look there we will be disappointed, for our established religious bodies frequently merely bolster privatistic individualism on the one hand and oppressive economic and political structures on the other. In the past they have articulated conceptions of the common good and created social contexts for genuine community and participation in America. The realities of world crisis, ecological, demographic, political, seem to require of us to try again to articulate a religious vision for a society that could embody love and justice to a degree which ours has long since ceased to do.

Perhaps the Mormon experience, which was in its initial phase a protest against the world of harsh, capitalist individualism, but then through much of this century became an increasingly close adaptation to that world which was originally rejected—perhaps that experience could give food for thought not only for Mormons but for all of us who live in this nation. Mormons often criticize the larger society in which they live and contrast it to their own vigorous community. How many of them realize that their own current social, economic and political views and actions may contribute to the wasteland they see around them, or that their own experience as a people might suggest a very different course for America today?

Notes

[1] James Ward Smith and A. Leland Jamison, eds., The Shaping of American Religions, vol. 1 (New Jersey: Princeton University, 1961), 213.

[2] John Winthrop, “A Model for Christian Charity,” as quoted in Perry Miller and Thomas H. Johnson, eds., The Puritans, vol. 1, rev. ed. (New York: Harper and Row, 1963), 198.

[3] Peter Laslett, John Locke – Two Treatises of Government – A Critical Edition with an Introduction and Apparatus Criticus (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1960), 368–69.

[4] John Locke, A Letter Concerning Toleration, ed. Charles L. Sherman (Appleton-Century, 1937) as quoted in Great Books of the Western World, vol. 35 (William Benton, publisher), 3.