"And I Saw the Hosts of the Dead, Both Small and Great": Joseph F. Smith, World War I, and His Visions of the Dead"

Richard E. Bennett

Richard E. Bennett, “‘And I Saw the Hosts of the Dead, Both Small and Great’: Joseph F. Smith, World War I, and His Visions of the Dead,” Religious Educator 2, no. 1 (2001): 104–24.

Richard E. Bennett was a professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University when this was written.

As I pondered over these things which are written, the eyes of my understanding were opened, and the Spirit of the Lord rested upon me, and I saw the hosts of the dead, both small and great. (Doctrine and Covenants 138:11)

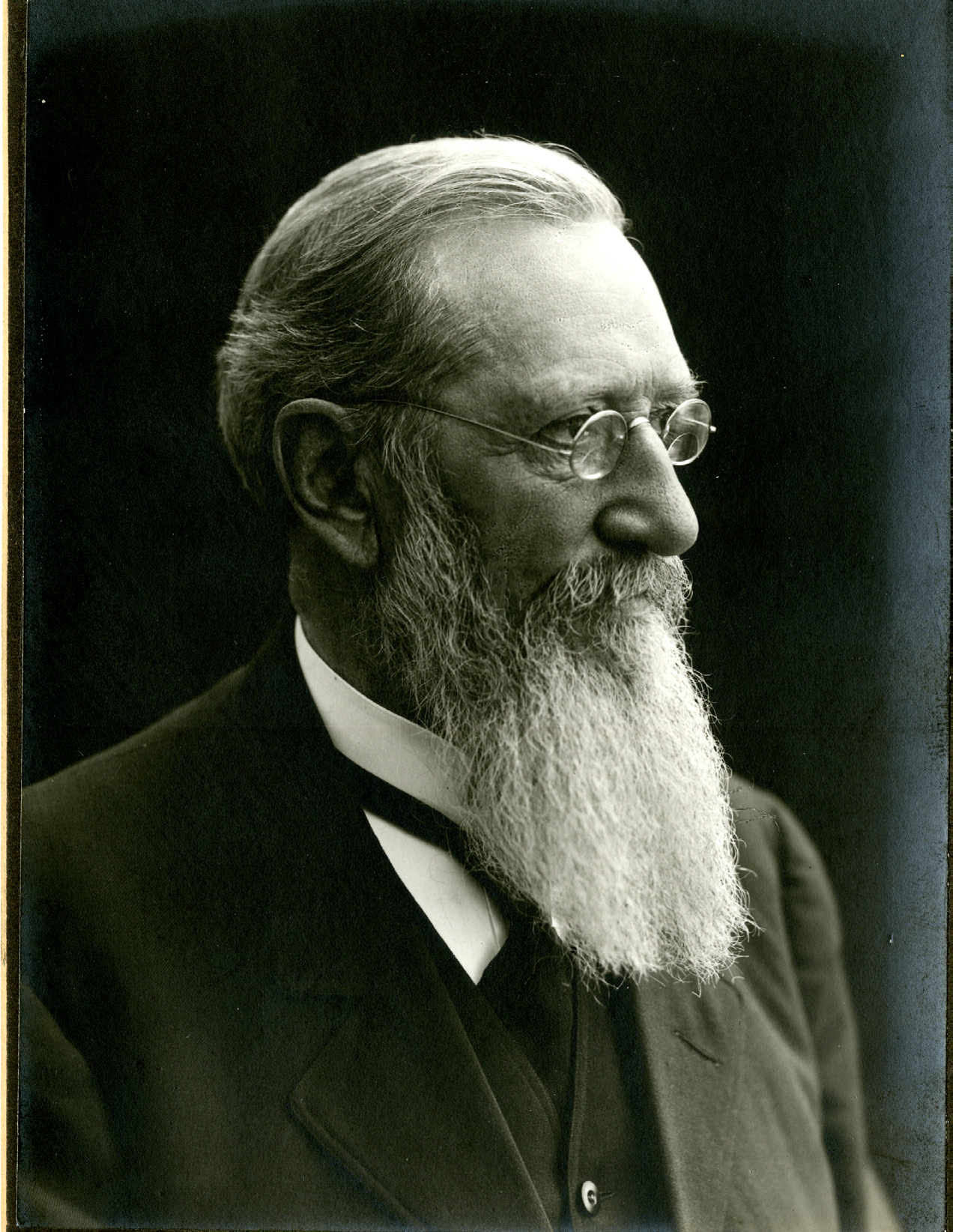

Joseph F. Smith’s discourses on life, death, and war are revered today by Latter-day Saints as profoundly important doctrinal contributions.[§] Sixth President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (he served from 1901 to 1918) and nephew of Joseph Smith, the founder of the Church, President Smith proclaimed some of his most comforting and most important discourses on the topics of death and suffering during the waning months of World War I. His final sermon, entitled “Vision of the Redemption of the Dead,” and now canonized as revelation by the Church, stands as an authoritative, scriptural declaration of its time.

A thorough study of the historical process that brought this doctrinal statement out of obscurity and into the realm of modern Latter-day Saint scripture begs to be written. However, the purpose of this paper is to place this and his other wartime sermons in their historical context, to suggest their place in the wider tapestry of Christian thought, and to argue for their fuller application as commentary on temple work, war, and several other critical issues of the day. Just as it took Church leaders years to rediscover the full importance of President Smith’s vision of the redemption of the dead and its significance as a vital assist to modern temple work, so also Latter-day Saint historians have been slow to view it as a unique commentary of the age. To the views and comments of other religionists of the day who were sharing their own important visions at war’s end, Joseph F. Smith’s must now be added.[1]

At the “eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month,” schoolchildren across Canada and throughout much of the British Commonwealth of Nations bow their heads in grateful remembrance for those who died in war. To this day, Remembrance Day, November 11, is a Sabbath-day-like observance, a tolling bell, in honor of those who gave their “last true measure of devotion” to the cause of God, king, and country. Canadians wear scarlet poppies on their lapels and gather respectfully at public war memorials across the land, sing hymns, honor mothers who lost sons in battle, and listen reverently to the following poem, penned in 1915 by the Canadian physician Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae during the frightful Second Battle of Ypres, where men by the tens of thousands were dying in the blooming poppy fields in the Flanders region of Belgium:

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.[2]

Joseph F. Smith, photograph by Emil Clausen, 1910. Courtesy of Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Joseph F. Smith, photograph by Emil Clausen, 1910. Courtesy of Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Indeed, “lest we forget,” more than nine million men in uniform and countless legions of civilians perished in the battlefields, battleships, and bombed-out byways of World War I. Another twenty-one million were permanently scarred and disfigured. Whatever the causes of that conflict, they have long been overshadowed by the “sickening mists of slaughter” that, like a pestilence, hung over the world for four and a half years. The terrible battles of the Marne, Gallipoli, Verdun, the Somme, Jutland, Passchendaele, Ypres, Vimy Ridge, and many others are killing fields synonymous with unmitigated human slaughter in what some have described as a nineteenth-century war fought with twentieth-century weaponry. This was the conflict, remember, that witnessed the awful stalemate of protracted trench warfare and pitched hand-to-hand combat in the “no-man’s lands” of western Europe, the introduction of Germany’s lethal submarine attacks, chemical-gas mass killings, and aerial bombings on a frightening scale. Yet the Great War, that “war to end all wars,” became but the catalyst and springboard for an even deadlier conflict a generation later. And with its long-prayed-for conclusion on 11 November 1918 came prayers for a lasting peace, hopes for a League of Nations that would guarantee future world peace, and sermons and visions that spoke of new hopes and new dreams for a blighted world.

Joseph F. Smith’s Responses to War

Compared to the other great religions of the time, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, with a membership then of only a few hundred thousand, most of whom lived in Utah and surrounding states, may seem like a very small voice in a vastly overcrowded cathedral. Though as many as fifteen thousand saw battle, mainly as enlisted men in the United States Army, Latter-day Saints were spared the tragedy of killing one another, unlike the gruesome specter of Catholics shooting Catholics and of Lutherans gunning down fellow Lutherans on some forlorn and distant battlefield of Europe. Headquartered far away in the tops of the Rocky Mountains of the American West, the Church remained relatively unscathed from the intimate hell and awful horror of war, much as it had done during America’s Civil War fifty years before. Nevertheless, its leaders held definite positions toward the war, some of which modified over time.

With the sudden, unexpected outbreak of the war and in response to Democratic President Woodrow Wilson’s request for prayers of peace, Joseph F. Smith, a confirmed Republican, and his counselors in the First Presidency, the highest ecclesiastical body in the Church, called upon the entire membership to support the nation’s president and to pray for peace. “We deplore the calamities which have come upon the people in Europe,” he declared, “the terrible slaughter of brave men, the awful sufferings of women and children, and all the disasters that are befalling the world in consequence of the impending conflicts, and earnestly hope and pray that they may be brought to a speedy end.”[3]

His second counselor, Charles W. Penrose, speaking further on President Smith’s behalf, condemned neither side in the war: “We ask Thee, O Lord, to look in mercy upon those nations. No matter what may have been the cause which has brought about the tumult and the conflict now prevailing, wilt Thou grant, we pray Thee, that it be overruled for good, so that the time shall come when, though thrones may totter and empires fall, liberty and freedom shall come to the oppressed nations of Europe, and indeed throughout the world.”[4] This spirit of the entire Church praying for peace lasted throughout the war.[5]

Speaking in the general conference of the Church just one month after the outbreak of war, President Smith expressed, for the first time, his public interpretation of the war and of its causes. Still stunned by news of the enormously high numbers of casualties so soon inflicted, he reiterated his desire for peace, pointed to the “deplorable” spectacle of war, and blamed it not on God but squarely on man’s inhumanity to man, on dishonest politics, on broken treaties, and, above all, on the apostate conditions he believed were endemic to modern Christianity. “God did not design or cause this,” he preached. “It is deplorable to the heavens that such a condition should exist among men.”[6] Choosing not to interpret the conflict in economic, political, or even nationalist tones, he ever saw it, at base, as the result of moral decline, of religious bankruptcy, and of the world’s refusal to accept the full gospel of Jesus Christ. “Here we have nations arrayed against nations,” he said, “and yet in every one of these nations are so-called Christian peoples professing to worship the same God, professing to possess belief in the same divine Redeemer . . . and yet these nations are divided against the other, and each is praying to his God for wrath upon and victory over his enemies.”[7] Loyal in every way to the message of the Book of Mormon and the Restoration of the gospel of Jesus Christ, he saw it this way:

Would it be possible—could it be possible, for this condition to exist if the people of the world possessed really the true knowledge of the Gospel of Jesus Christ? And if they really possessed the Spirit of the living God—could this condition exist? No; it could not exist, but war would cease, and contention and strife would be at an end. . . . Why does it exist? Because they are not one with God, nor with Christ. They have not entered into the true fold, and the result is they do not possess the spirit of the true Shepherd sufficiently to govern and control their acts in the ways of peace and righteousness.[8]

The only real and lasting antidote to the sin of war, he believed, was the promulgation of the restored gospel of Jesus Christ “as far as we have power to send it forth through the elders of the Church.”[9] Though the war was not the work of God, President Smith was nonetheless quick to see in it a fulfilment of divine prophecy, both ancient and modern. “The newspapers are full of the wars and the rumors of wars,” he wrote in a private family letter of November 1914, “which seem to be literally poured out upon all nations as foretold by the Prophet [Joseph Smith] in 1832. The reports of the carnage and destruction going on in Europe are sickening and deplorable, and from the latest reports the field of carnage is greatly enlarging instead of diminishing.”[10]

A few weeks later, in his annual Christmas greeting to the Church for December 1914, he returned to this same theme. “The sudden ‘outpouring’ of the spirit of war upon the European nations which startled the whole world and was unexpected at the time of its occurrence, had long been expected by the Latter-day Saints, as it was foretold by the Prophet Joseph Smith on Christmas Day, December 25th, 1832.”[11]

Yet no one took pleasure in seeing such foreboding prophecy fulfilled. Nor could prophecies be made tantamount to divine imposition on the affairs of men. At stake was the agency—and the evil—of man. As the cold calamity of war spread across the battlefields of Europe, President Smith continually stressed this point. “God, doubtless, could avert war,” he said in December of 1914, “prevent crime, destroy poverty, chase away darkness, overcome error, and make all things bright, beautiful and joyful. But this would involve the destruction of a vital and fundamental attribute of His sons and daughters that they become acquainted with evil as well as good, with darkness as well as light, with error as well as truth and with the results of the infraction of eternal laws.”[12] Thus, the war was seen as a schoolmaster, a judgment of man’s own doing, a terrible lesson of what inevitably transpires when hate and greed rule the day.

Despite these broken laws and with them the inevitable fulfillment of calamitous prophecy, there can be found, like a stream of clear water running throughout President Smith’s teachings, the doctrine of ultimate redemption and resolution:

Therefore [God] has permitted the evils which have been brought about by the acts of His creatures, but will control their ultimate results for His glory and the progress and exaltation of His sons and daughters, when they have learned obedience by the things they suffer. . . . The foreknowledge of God does not imply His action in bringing about that which He foresees.[13]

Vowing initially not to take sides in the struggle, President Smith found it increasingly challenging, however, to remain neutral. The dreadful sinking of the Lusitania in May 1915 struck an ominous chord in America, intent as the country was in staying clear of the conflict. His colleague, James E. Talmage, then a member of the Church’s Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, and an Englishman by birth, described the sinking as “one of the most barbarous developments of the European war,” charging Germany for staining its hands “with innocent blood never to be washed away.”[14]

Despite such wartime atrocities, President Smith clung to the hope that America could somehow remain detached from the war. “I am glad that we have kept out of war so far, and I hope and pray that we may not be under the necessity of sending our sons to war, or experience as a nation the distress, the anguish and sorrow that come from a condition such as exists upon the old continent.”[15]

Nevertheless, as America lurched reluctantly toward war, he came to see America’s involvement as a necessity. News of the Zeppelin bombing raids over England, and his consequent fear for the safety of his own mission-president son and missionaries then serving in England, particularly bothered him and led him to question ever further Germany’s wartime tactics. “It seems to me that the only object of such raids is the wanton and wicked destruction of property and the taking of defenseless lives,” he wrote.

It appears that the spirit of murder, the shedding of blood, not only of combatants but of anyone connected with the enemy’s country seems to have taken possession of the people, or at least the ruling powers in Germany. What they gain by it, I do not know. It is hardly possible that they expect to intimidate the people by such actions, and it surely does not diminish the forces of the opposition. By such unnecessary and useless raids in the name of warfare, they are losing the respect of all the nations of the earth.[16]

A staunch patriot, he was soon to admit the obvious: “I have a feeling in my heart that the United States has a glorious destiny to fulfil, and that part of that glorious destiny is to extend liberty to the oppressed, as far as it is possible to all nations, to all people.” Gradually, he forged a cautious, nonpacifist view in behalf of the entire Church: “I do not want war; but the Lord has said it shall be poured out upon all nations, and if we escape, it will be ‘by the skin of our teeth.’ I would rather the oppressors should be killed, or destroyed, than to allow the oppressors to kill the innocent.”[17]

If Latter-day Saints must fight—and thousands of them soon enlisted in the cause—their attitude must ever be that of “peace and good will toward all mankind, . . . that they will not forget that they are also soldiers of the Cross, that they are ministers of life and not of death; and when they go forth, they may go forth in the spirit of defending the liberties of mankind rather than for the purpose of destroying the enemy. . . . Let the soldiers that go out from Utah be and remain men of honor.”[18] Eager to demonstrate loyalty to an America still suspicious of the Church and of some of its teachings and to support President Wilson’s entry into the war, President Smith led active campaigns to enlist Latter-day Saints in the ranks of the military and to involve the Church and its membership in the various Liberty Bond drives of the time, raising hundreds of thousands of dollars in the process.[19]

Significantly, his writings bear an absence of malice or a spirit of vengeance toward the aggressor. Less critical than other younger leaders, such as James E. Talmage, who, although not given to retribution, felt Germany had a debt to pay, President Smith was ever slow to condemn. Said he: “Let the Lord exercise vengeance where vengeance is needed. And let me not judge my fellow men, nor condemn them lest I condemn them wrongly.”[20]

Meanwhile, until the war ended, Latter-day Saints joined with others in praying for peace and in taking up arms in the cause of victory over the enemy. America’s involvement eventually turned the tide of war, ultimately bringing a defeated Germany and the other Axis powers to Versailles. And though half a world away, news of the pending peace was as jubilantly received in Utah as it was most everywhere else in the free world.[21]

The Armistice

The Latter-day Saints were, of course, not alone in proclaiming a vision of the war and of peace. A sampling of what others saw as the war wore on may be instructive. Randall Thomas Davidson, Archbishop of Canterbury, by the time the conflict had ended was still trying earnestly to see meaning out of a senseless war, to see divine purpose in man’s malignancy, and to bring vision to a groping world. “There, then, with all that the war has brought us of darkened homes and of shattered hopes for those we loved,” he said in his war-closing sermon of gratitude preached at Westminster Abbey in London on November 10, 1918,

with all its hindering and setting back of our common efforts and energies to promote things peaceable and lovely and of good report, [the war] has, beyond any doubt, been our schoolmaster to bring us to a larger vision of the world as God sees it. It is one of the great things which our sons, our dear sons, have wrought for us by their dauntless sacrifice. . . . Just now, this week, when the whole life—I do not think I am exaggerating—the whole life of the world is being re-conditioned, re-established, re-set for good. This is that crisis-hour. Something has happened, is happening, which can best find description in . . . the living word or message of God to man. It cuts right to the centre of our being.[22]

He closed a later sermon with his particular vision of a new Christian paradigm:

Jesus Christ is the real centre and strength of the best hopes and efforts man can make for the bettering and the brightening of the world. Only we must quietly, determinedly, thoughtfully, take His law and His message as our guide. . . . The task is hardest perhaps when we are dealing with life’s largest relationship—the relationship between peoples. Can we carry the Christian creed and rule there? Who shall dare to say we cannot? It needs a yet larger outlook. . . . Surely it is a vision from on high.[23]

Pope Benedict XV, in his first encyclical immediately following the end of the war, rejoiced that “the clash of arms has ceased,” allowing “humanity [to] breathe again after so many trials and sorrows.” Next only to gratitude, his sentiment was one of profound regret, bordering on apology, that a leading cause of the war had been the “deplorable fact that the ministers of the Word” had not more courageously taught true religion rather than the politics of accommodation from the pulpit. The conscience of Christianity had been scarred by its own advocates. “The blame certainly must be laid on those ministers of the Gospel,” he lamented. He went on to chastise the pulpit by calling for a new vision, a new order of valiant, righteous Christian spokesmen who would declare peace and the cross fearlessly. “It must be our earnest endeavor everywhere to bring back the preaching of the Word of God to the norm and ideal to which it must be directed according to the command of Christ Our Lord, and the laws of the Church.”[24]

The official American Catholic response may best be seen in the pastoral letters of its bishops. At its base, the war showed a deep “moral evil” in man where “spiritual suffering” and “sin abounded.” Despite all of mankind’s progress—“the advance of civilization, the diffusion of knowledge, the unlimited freedom of thought, the growing relaxation of moral restraint— . . . we are facing grave peril.” Scientific and materialistic progress notwithstanding, a world without moral discipline and faith will lead only to destruction. The only true vision of hope is “the truth and the life of Jesus Christ,” and the Catholic Church must uphold the dignity of man, defend the rights of the people, relieve distress, consecrate sacrifice, and bind all classes together in the love of the Savior.[25]

James Cardinal Gibbons of Baltimore, the leading American Catholic spokesman, in calling upon Americans to “thank God for the victory of the allies and to ask him for grace to ‘walk in the ways of wisdom, obedience and humility,’” ordered his priests to substitute the prayer of thanksgiving in the Mass in place of the oration.[26] He instructed them further that a solemn service be held in all the churches of the archdiocese on November 28, 1918, at which the Church’s official prayer of thanksgiving, the Te Deum, should be sung.[27] Written as early as AD 450, the words to one of Catholicism’s most famous hymns speak of man’s immortality, of Christ’s divinity, and of his redemption of the dead:

We praise Thee, O God: we

acknowledge Thee to be the Lord.

Thee, the Eternal Father, all

the earth doth worship . . .

Thou, O Christ, art the King of glory.

Thou art the Everlasting Son of the Father.

Thou didst not abhor the Virgin’s

womb, when Thou tookest upon

Thee human nature to deliver man.

When Thou hadst overcome the

sting of death, Thou didst open

to believers the kingdom of heaven.

Thou sittest at the right hand of

God, in the glory of the Father.

Thou, we believe, art the Judge to come.[28]

The American Protestant view of the war, and more especially of its postwar opportunities, are varied and diverse and defy simple categorization and analysis. There were almost as many “visions” as there were hundreds of denominations. While most, like Bishop Charles P. Anderson of the Protestant Episcopal Church, spoke in terms of gratitude, many others soon were speaking jingoistically, calling for immediate punishment and retribution.[29] “The Christian Century, which was representative of a great portion of Christendom, believed in the thorough chastisement of Germany.”[30] Likewise, the Congregationalist editorialized that “Germany is a criminal at the bar of justice.”[31] Reverend Dr. S. Howard Young of Brooklyn called “retribution upon the war lords” as “divine,” “the first world lesson to be derived from the German downfall.”[32]

Meanwhile, Billy Sunday, “God’s Grenadier” and by far the most popular patriot/

Other, more moderate clergymen like the positive-minded Presbyterian Robert E. Speer saw a moral victory stemming out of the war, a new vision rising out of the ashes of Europe. “The war also has unmistakably set in the supreme place those moral and spiritual principles which constitute the message of the Church,” he declared. “The war has shown that these values are supreme over personal loss and material interest. . . . We succeeded in the war whenever and wherever this was our spirit. . . . The war says that what Christ said is forever true.”[35]

Rabbi Silverman, speaking in Chicago’s Temple Beth-El synagogue, mirrored Speer’s sentiments. “The world was nearer its millennium today than ever before,” he is reported to have said. “War had brought mankind nearer to brotherhood than had centuries of religious teachings. . . . War had brought religion back to its original task of combating bigotry, fighting sin, and uplifting mankind.”[36]

Both Reverend Speer and Henry Emerson Fosdick, professor of the Union Theological Seminary in New York, along with other leading religious leaders, welcomed the end of war as an opportunity to launch “the Church Peace Union,” a new united religious order funded, in part, by Andrew Carnegie and his Carnegie Endowment for International Peace to unite multiple Protestant faiths marching under one grand united banner—“the new political heaven [to] regenerate earth,” as Bishop Samuel Fallows of the Reformed Episcopal Church liked to describe it. Though destined to failure because of oppressive debts, internal disagreements, and opposition from Protestant fundamentalism, for a brief moment this Interchurch World Movement of Protestants, Catholics, and Jewish leaders in America became “the principal voice of institutional religion on behalf of peace-keeping and peace-making” and appeared to hold enormous promise for church unity, social reform, and economic improvement.[37]

Fosdick, one of the most eloquent American Protestant statesmen of his time, had grudgingly supported America’s entry into the war but came out of it a confirmed pacifist. Reflecting the utter disillusionment the war wrought on many religionists, Fosdick listed several elements in his vision of warning for the future: “There is nothing glamorous about war any more,” “war is not a school for virtue any more,” “there is no limit to the methods of killing in war any more,” “there are no limits to the cost of war any more,” “there is no possibility of sheltering any portion of the population from the direct effect of war any more,” and “we cannot reconcile Christianity and war any more.”[38] Every effort must be made to avoid such a future calamity. He, like many others, was bitterly disappointed by America’s refusal to ratify the Versailles Peace Treaty and enter the League of Nations, which President Wilson had so arduously supported. As one commentary dryly remarked, “God won the war and the devil won the peace.”[39]

Joseph F. Smith’s Visions of the Dead

Worn out by a long life of devoted Church service and worn down in sorrow due to the recent deaths of several members of his immediate family, Joseph F. Smith, though a loving soul, knew all about grief. “I lost my father when I was but a child,” he once said. “I lost my mother, the sweetest soul that ever lived, when I was only a boy. I have buried one of the loveliest wives that ever blessed the lot of man, and I have buried thirteen of my more than forty children. . . . And it has seemed to me that the most promising, the most helpful, and, if possible, the sweetest and purest and the best have been the earliest called to rest.”[40] Speaking of the loss of one of his former polygamist wives, Sarah E., and, shortly thereafter, of his daughter Zina, he further said: “I cannot yet dwell on the scenes of the recent past. Our hearts have been tried to the core. Not that the end of mortal life has come to two of the dearest souls on earth to me, so much as at the sufferings of our loved ones, which we were utterly powerless to relieve. Oh! How helpless is mortal man in the face of sickness unto death!”[41]

His daughter’s death triggered four of the most revealing discourses ever given by a Latter-day Saint leader on the doctrines of death, the spirit world, and the Resurrection. As one noted scholar put it: “It is doubtful if in any given period of like duration in the entire history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints so much detail as to the nature of the life after death has been given to any other prophet of this dispensation.”[42] All were well received by the membership and extended hope and comfort to those who had lost loved ones or who might be asked to sacrifice family members in times of peace or of conflict. The war, still raging loud and cruel, served as a vivid backdrop to these emerging doctrines.

On April 6, 1916, with the battles of Verdun and the Somme very much dominating the daily news, he gave a talk entitled “In the Presence of the Divine” in which he spoke of the very thin veil separating the living from the dead. Speaking of Joseph Smith, Brigham Young, Wilford Woodruff, and his other predecessors, he preached the doctrine that the dead, those who have gone on before, “are as deeply interested in our welfare today, if not with greater capacity, with far more interest, behind the veil, than they were in the flesh. I believe they know more. . . . Although some may feel and think that it is a little extreme to take this view, yet I believe that it is true.” He went on to say, “We cannot forget them; we do not cease to love them; we always hold them in our hearts, in memory, and thus we are associated and united to them by ties that we cannot break.”[43]

President Smith taught that death was neither sleep nor annihilation; rather, death involved a change into another world where the spirits of those once here can be solicitous of our welfare, “can comprehend better than ever before, the weaknesses that are liable to mislead us into dark and forbidden paths.”[44]

Two years later, speaking at a meeting in Salt Lake City in February 1918, he spoke additional words of comfort and consolation, particularly to those who had lost children or whose youthful sons were dying overseas. “The spirits of our children are immortal before they come to us,” he began,

and their spirits after bodily death are like they were before they came. They are as they would have appeared if they had lived in the flesh, to grow to maturity, or to develop their physical bodies to the full stature of their spirits. . . . [Furthermore,] Joseph Smith taught the doctrine that the infant child that was laid away in death would come up in the resurrection as a child; and, pointing to the mother of a lifeless child, he said to her: “You will have the joy, the pleasure and satisfaction of nurturing this child, after its resurrection, until it reaches the full stature of its spirit.”. . . It speaks volumes of happiness, of joy and gratitude to my soul.[45]

Two months later, having recovered from illness sufficiently to speak at the April 1918 general conference of the Church, he gave a talk entitled “A Dream That Was a Reality.” In it, he recounted a particularly poignant and unforgettable dream he had experienced sixty-five years earlier as a very young missionary in Hawaii, a dream-vision that dramatically influenced the rest of his life. He spoke of seeing his father, Hyrum, his mother, Mary, Joseph Smith, and several others who had ushered him into a mansion after he had bathed and cleansed himself. “That vision, that manifestation and witness that I enjoyed that time has made me what I am,” he confessed. “When I woke up I felt as if I had been lifted out of a slum, out of despair, out of the wretched condition that I was in. . . . I know that that was reality, to show me my duty, to teach me something, and to impress upon me something that I cannot forget.”[46]

Just weeks before, on January 23, his son Hyrum, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve, British Mission president, and then only forty-five years of age, died of a ruptured appendix. It was a devastating blow from which Joseph F. never fully recovered, compounded as it was with the further sorrowful news of the death of his daughter-in-law and Hyrum’s wife, Ida Bowman Smith, just a few months thereafter. Wrote Talmage in behalf of the Twelve: “Our great concern has been over the effect the great bereavement will have upon President Joseph F. Smith, whose health has been far from perfect for months past. This afternoon he spent a little time in the office of the First Presidency, and we find him bearing up under the load with fortitude and resignation.”[47] Sick and intermittently confined to bed rest for several months afterwards he rallied sufficiently to speak briefly in the October general conference of the Church, long enough to proclaim his particular message of peace to a war-weary world.[48]

He spoke of having lately received, while pondering on the biblical writings of the Apostle Peter, another, ultimately his final, vision of the dead. While meditating on these things, he said he “saw the hosts of the dead, both small and great,” those who had died “firm in the hope of a glorious resurrection,” waiting in a state of paradise for their ultimate redemption and resurrection. Suddenly, the “Son of God appeared, declaring liberty to the captives who had been faithful.” Choosing not to go himself to the wicked and unfaithful dead who waited in the more nether realms of the spirit world, Christ mobilized a formidable missionary force among his most faithful followers, dispatching them to minister and teach the gospel of Jesus Christ to “all the spirits of men,” those who had been less faithful and obedient in their mortal lives, including, as Peter writes, “those who were sometime disobedient” in the days of Noah and the great flood. In addition, he saw many of the ancients, including Adam and Eve and the prophets, involved in this spirit prison ministry of redemption. Likewise, “the faithful elders of this dispensation” and the “faithful daughters” of Eve were called to assist. His vision closed with the declaration that the dead “who repent will be redeemed, through obedience to the ordinances of the house of God . . . after they have paid the penalty of their transgressions.”[49]

Whereas his earlier discourses have remained memorable sermons, this sixty-verse document was immediately sustained, in the words of James E. Talmage, as “the Word of the Lord” by his counselors in the First Presidency and by the Quorum of the Twelve.[50] For reasons not entirely clear, though widely read in the Church, the document was not formally accepted as canonized scripture until fifty-eight years later when, in 1976, President Spencer W. Kimball directed that it be added to the Pearl of Great Price.[51] Later, in June 1979, the First Presidency announced that the vision would become section 138 of the Doctrine and Covenants. Considered an indispensable contribution to a fuller understanding of temple work (especially in an age of very active temple construction), the performance of proxy ordinances for the dead, and the relationship between the living and the dead, it has been heralded as “central to the theology of the Latter-day Saints because it confirms and expands upon earlier prophetic insights concerning work of the dead.”[52] Others have written elsewhere about the contributions of this document to Mormon temple work.[53]

Because this document is far more than a mere sermon to the faithful Latter-day Saint and because it is regarded as the word and will of the Lord—one of only two canonized revelations of the twentieth century—it bears careful scrutiny. And, as a wartime document, it may have other meanings and applications not plumbed before.

For instance, although a discourse on the dead, it owed nothing to spiritualism. It is a matter of record that public interest in the dead and in communicating with the dead peaked during and immediately following the war. In 1918 Arthur Conan Doyle of Sherlock Holmes fame published New Revelation, a book on the subject of psychical research and phenomena that bemoaned the decline in church attendance in England and of Christianity generally and proclaimed a new religion, a new revelation. He urged a belief not in the fall of man or in Christ’s redemption as the basis of faith, but in the validity of “automatic writings,” seances, and other expressions of spiritualism as a new universal religion of communicating with lost loved ones—or, as he put it, “the one provable thing connected with every religion, Christian or non-Christian, forming the common solid basis upon which each raises, if it must needs raise, that separate system which appeals to the varied types of mind.”[54]

In contrast, President Smith’s vision was very much Christ-centered, a reiteration of the Savior’s atonement for a fallen world. Though he certainly believed that “we move and have our being in the presence of heavenly messengers and heavenly beings,” and though the dead may even transcend the veil and appear unto loved ones if so authorized, he steered the Church away from any hint of spiritualism.[55] Latter-day Saints were to seek after the dead—that is, their spiritual welfare—rather than to seek the dead.

His revelation also reaffirmed the Christian belief in Adam and Eve and in a divine creation, for, in President Smith’s words, he saw “Father Adam, the Ancient of Days, and father of all” as well as “our glorious Mother Eve” (Doctrine and Covenants 138:38–39). Though nothing is said specifically about evolution and the caustic, contemporary debates of the time over the origin of the species, these verses very simply restated the doctrines of the Church on this subject without argument or ambiguity.

Likewise, in an age of higher criticism with its attack on the authenticity and authority of the Bible, the revelation reestablished, for Latter-day Saints at least, a twentieth-century belief in the primacy, historicity, and authority of scripture, a belief in the writings of Peter, a belief in Noah and the flood not as allegory but as actual event, and, by extension, a renewed belief in the entire Old and New Testaments. For a Church oftentimes criticized for its belief in additional scripture, if nothing else, section 138 is a classic declaration of biblical authority for modern times.[56]

The vision may also be important for what it does not say. There is no discussion of peace treaties, no references to ecumenism or the interchurch movements of the times, no calls for social repentance and the social gospel. Neither pro war nor pacifist, it says nothing about cultural or nationalistic superiorities. The problem of evil is reduced to redeemable limits; and although man will always reap what he sows, there is still hope and redemption. Meanwhile, the Church retains its own mission as the gospel of Jesus Christ on the earth as preestablished in its restoration a century earlier.

Finally, the vision proclaimed God’s intimate involvement in the affairs of humankind and his benevolent interest in his children. Steering the Church away from the yawning secularism that stood to envelope many other faiths in the postwar era, President Smith spoke confidently, above all, about Christ and his triumphant victory over sin and death.[57] To the utter waste and sheer terror of the just-concluded catastrophe, there was ultimate redemption. To those who had lost faith in God and in their fellowmen, there was certain restoration. To the soldier lost in battle, to the sailor drowned at sea, and to a prophet-leader mourning the deaths of his own family, there remained the reality of the Resurrection.

Notes

[§] I thank my research assistant, Keith Erekson, for his valuable assistance in helping me prepare this work.

[1] The definitive biography of President Joseph F. Smith remains to be written. Joseph Fielding Smith, one of his sons, wrote Life of Joseph F. Smith, Sixth President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1938; Deseret Book, 1969) in praise of his father. Since then, Francis M. Gibbons has written Joseph F. Smith: Patriarch and Preacher, Prophet of God (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1984). See also Scott Kenney, “Joseph F. Smith,” in The Presidents of the Church, ed. Leonard J. Arrington (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1986), 179–211.

[2] John McCrae, “In Flanders Fields,” One Hundred and One Famous Poems, ed. Roy J. Cook (Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1958), 11. Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae, a member of the first Canadian contingent, died in France on January 28, 1918, after four years of service on the western front.

[3] “Special Announcement” of the First Presidency, September 8, 1914, in Messages of the First Presidency of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. James R. Clark (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1970), 4:311 (hereafter MFP).

[4] Charles W. Penrose, “A Prayer for Peace,” in Conference Report, October 1914, 9.

[5] See Conference Report, April 1915, 3; and Conference Report, April 1916, 3.

[6] Joseph F. Smith, in Conference Report, October 1914, 7.

[7] Joseph F. Smith, in Conference Report, October 1914, 7.

[8] Joseph F. Smith, in Conference Report, October 1914, 7

[9] Joseph F. Smith, in Conference Report, October 1914, 8. In a letter to his son, Hyrum, then a mission president in Liverpool, England, President Smith said, “We still see from the papers that the war in Europe is going on, the whole thing is a sad comment upon the civilization and Christian spirit of the age.” Joseph F. Smith to Hyrum Smith, November 7, 1914, Correspondence Files, Joseph F. Smith Collection, Church Archives, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City (hereafter Church Archives).

[10] Joseph F. Smith to Hyrum Smith, November 7, 1914.

[11] From “A Christmas Greeting from the First Presidency,” December 19, 1914, in MFP, 4:319. The prophecy alluded to, commonly referred to as the “Civil War Prophecy,” spoke of the pending Civil War and its commencement in South Carolina. Later, the South would be compelled to call upon Great Britain for assistance. Great Britain, in turn, “shall also call upon other nations, in order to defend themselves against other nations, and thus war shall be poured out upon all nations” (Doctrine and Covenants 87:3).

[12] From “Christmas Greeting from the First Presidency,” in MFP, 4:325–26.

[13] From “Christmas Greeting from the First Presidency,” in MFP, 4:325–26

[14] Journal of James E. Talmage, May 7 and 13, 1915, James E. Talmage Collection, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University. For a more thorough study of Elder Talmage’s corresponding views of the war, see the author’s “‘How Long, Oh Lord, How Long?’ James E. Talmage and the Great War,” Religious Educator 3, no. 1 (2002): 87–102.

[15] Joseph F. Smith, in Conference Report, April 1915, 6. Writing in an editorial of December 1915, he said much the same: “We pray that [America’s] leaders may receive wisdom of our Father in Heaven, to so direct the affairs in their charge that we may continue in the enjoyment of peace and prosperity throughout the land.” Joseph F. Smith to the editor of the Liahona, The Elders’ Journal, 18 December 1915, Joseph F. Smith Papers, Church Archives.

[16] Joseph F. Smith to his son, Hyrum Smith, February 19, 1916, Joseph F. Smith Papers, Church Historical Department.

[17] Joseph F. Smith, in Conference Report, October 1916, 154.

[18] Joseph F. Smith, in Conference Report, April 1917, 3–4.

[19] The Church itself participated in the war effort by purchasing $850,000 in liberty bonds. In addition, it strongly encouraged its membership to participate in the bond drive with the result that the people of Utah far exceeded the state’s quota of $6.5 million. One reason the Church was so eager to participate in the war effort was to shed the negative publicity cast upon it during and immediately following the Reed Smoot Senate hearing in Washington, DC. Elected in 1903, Smoot, a member of the Twelve Apostles, had been barred from taking his seat until 1907 because of acrimonious debates over plural marriage and Latter-day Saint loyalties. President Smith and many other prominent Church leaders traveled to Washington on several occasions to testify on behalf of the Church. In 1907 the First Presidency issued a special address to the world explaining the Church’s stand on these and many other topics, including its loyalty to America. For a fine summary of the Reed Smoot hearings and their impact on the Church, see Thomas G. Alexander, Mormonism in Transition: A History of the Latter-day Saints, 1890–1930 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986), 16–36. See also Kathleen Flake, The Politics of Religious Identity: The Seating of Reed Smoot, Mormon Apostle (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004).

[20] From a talk entitled “Status of Children in the Resurrection,” May 1918, in MFP, 5:97.

[21] Official word reached Salt Lake City very early in the morning of November 11, 1918. Despite the late hour and the curfews imposed because of the influenza epidemic, the city seemed to spring into life. In the words of James E. Talmage, “Bells were tolled, whistles blown, and within an incredibly short time hundreds of automobiles were dashing about the streets, most of them having tin cans, sheet iron utensils and other racket-making appendages attached to the rear.” Later in the day, “flags and bunting appeared in abundance everywhere, tons of confetti were thrown from the tops of high buildings, every available band was pressed into service, and during the afternoon and well on into the night dancing was indulged in on Main Street.” Talmage enthusiastically concluded, “Such a day as this has never before been witnessed in the world’s history.” James E. Talmage Journal, November 11, 1918.

[22] Randall Thomas Davidson, The Testing of a Nation (London: Macmillan, 1919), 159–60; from a sermon entitled “The Armistice,” given November 10, 1918.

[23] Davidson, Testing of a Nation, 176–77, 180; from a sermon entitled “The Dayspring,” given December 29, 1918.

[24] From “Quod Iam Diu,” Encyclical of Pope Benedict XV on the Future Peace Conference, December 1, 1918, 182, in The Papal Encyclicals, 1903–1939, comp. Claudia Carlen (Wilmington, NC: McGrath, 1981), 1:153–54.

[25] Pastoral Letter of the Archbishops and Bishops of the United States Assembled in Conference at the Catholic University of America (Washington, DC: National Catholic Welfare Council, 1920), 39–40.

[26] Chicago Daily Tribune, November 11, 1918, 3.

[27] See John Tracy Ellis, The Life of James Cardinal Gibbons, Archbishop of Baltimore, 1834–1921 (Milwaukee: Bruce, 1952), 258.

[28] “Te Deum,” The Catholic Encyclopedia for School and Home (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1965), 10:563.

[29] Chicago Daily Tribune, November 15, 1918, 4.

[30] Ray H. Abrams, Preachers Present Arms: The Role of the American Churches and Clergy in World War One and Two, with Some Observations on the War in Vietnam (Scottsdale, PA: Herald, 1969), 232–33.

[31] Abrams, Preachers Present Arms, 233.

[32] Chicago Daily Tribune, 11 November 1918, 11.

[33] Roger A. Bruns, Preacher: Billy Sunday and Big-Time American Evangelism (New York: Norton, 1922), 249.

[34] Bruns, Preacher, 252.

[35] R. E. Speer, The New Opportunity of the Church (New York: Macmillan, 1919), 48–49. As quoted in A Documentary History of Religion in America Since 1865, ed. Edwin S. Gaustad (Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans, 1983), 148.

[36] Chicago Daily Tribune, November 11, 1918. The editor of the Methodist Review called for the regeneration of the family and of motherhood and for reenshrining the teachings of Christ. “Without this light the world must stumble along in darkness. Is it not evident then that it is the bounden duty of the Church to seek a fresh Pentecost? The times, wild and disturbed as they are, are not unripe for a baptism of power from within the veil.” “What the World Is Facing,” Methodist Review 68, no. 4 (October 1919): 590.

[37] Gaustad, Documentary History of Religion, 148. This interchurch vision continued to a lesser extent as the Federal Council of Churches, with Reverend Robert E. Speer playing an active part.

[38] Henry Emerson Fosdick, “‘Shall We End the War,’ A Sermon Preached at the First Presbyterian Church, New York, June 5, 1921” (distributed through the Clearing House for the Limitation of Armament, New York), 3–12.

[39] Eldon G. Ernst, Moment of Truth for Protestant America: Interchurch Campaigns Following World War One, Dissertation Series, no. 3 (n.p.: American Academy of Religion and Scholars, 1974), 139.

[40] In MFP, 5:92.

[41] Joseph F. Smith to Hyrum Smith, November 3, 1915, Joseph F. Smith Papers, Church Archives.

[42] Editorial note by James R. Clark in MFP, 5:5.

[43] In MFP, 5:6–7.

[44] In MFP, 7.

[45] From a discourse entitled “Status of Children in the Resurrection,” in MFP, 5:94–95.

[46] From a discourse entitled “A Dream That Was a Reality,” in MFP, 5:100–101. This was not the first unique dream President Smith had of his beloved mother. On July 21, 1891, he had dreamed that his “precious mother came to live with him. It seemed that she had been gone for a long time.” In this dream, “[I] fixed her up a room all for herself and made it as comfortable as I could. . . . This is the third time I have seemed to put [up] my mother since she left us.” Joseph F. Smith to “My Dear Aunt Thompson,” July 21, 1891, Letters of Joseph F. Smith, as cited in the Scott G. Kenney Collection, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library.

[47] James E. Talmage Journal, January 25, 1918.

[48] Because of his frail condition, President Smith did not actually read this document in conference but had it delivered in writing to the leadership of the Church shortly after the conference had concluded.

[49] See Doctrine and Covenants 138 to read the vision in its entirety.

[50] Wrote Elder Talmage in a journal entry for October 31, 1918: “Attended meeting of the First Presidency and the Twelve. Today President Smith, who is still confined to his home by illness, sent to the Brethren the account of a vision through which, as he states, were revealed to him important facts relating to the work of the disembodied Savior in the realm of departed spirits, and of the missionary work in progress on the other side of the veil. By united action the Council of the Twelve, with the Counselors in the First Presidency, and the Presiding Patriarch accepted and endorsed the revelation as the Word of the Lord. President Smith’s signed statement will be published in the next issue (December) of the Improvement Era.” James E. Talmage Journal, October 31, 1918.

[51] From time to time, General Authorities referred to the vision before 1976. See, for example, Joseph L. Wirthlin, April 1945 general conference; Marion G. Romney, April 1964 general conference; Spencer W. Kimball, September 1966 general conference; and Boyd K. Packer, October 1975 general conference. For this information I am indebted to Robert L. Millet, “The Vision of the Redemption of the Dead,” in Hearken, O Ye People: Discourses on the Doctrine and Covenants (Sandy, Utah: Randall Book, 1984), 268. Latter-day Saints accept the messages of their living prophets as scripture. “Whatsoever they shall speak when moved upon by the Holy Ghost shall be scripture, shall be the will of the Lord, shall be the mind of the Lord, shall be the word of the Lord, shall be the voice of the Lord, and the power of God unto salvation” (Doctrine and Covenants 68:4). However, there are degrees of scripture within the Church. Once Joseph F. Smith’s vision had been presented to the Church membership and voted on and accepted as scripture, it shifted in significance from scripture to canonized scripture. As Robert L. Millet said, “Prior to 3 April 1976 it represented a theological document of inestimable worth to the Saints, one that deserved the study of those interested in spiritual things; on that date it was circumscribed into the standard works, and thus its message—principles and doctrines—became binding upon the Latter-day Saints, the same as the revelations of Moses or Jesus or Alma or Joseph Smith. The Vision of the Redemption of the Dead became a part of the canon, the rule of faith and doctrine and practice—the written measure by which we discern truth from error” (Millet, “Vision of the Redemption of the Dead,” in Hearken O Ye People, 265).

[52] Millet, “Vision of the Redemption of the Dead,” 259.

[53] See Church Educational System, The Doctrine and Covenants Student Manual (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1981), 356–61; see also Michael J. Preece, Learning to Love the Doctrine & Covenants (Salt Lake City: MJP Publishing, 1988), 409–13.

It should be noted in passing, however, that Joseph F. Smith’s vision was not a sudden extension of his sickness or sorrows. For instance, as early as 1882 he had spoken of Christ’s preaching in the spirit prison (Gospel Doctrine—Selections from the Sermons and Writings of Joseph F. Smith [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1961], 437–38). Likewise, he had previously taught of ancient prophets and modern-day missionaries teaching to the spirits in prison (Gospel Doctrine, 430, 460). His funeral sermons are replete with this doctrine. For example, see his talk given in Logan, Utah, October 27, 1907, at the quarterly conference of the Logan Stake, typescript, 16, Papers of Joseph F. Smith, Church Archives. Although a careful analysis of President Smith’s developing doctrines of death and the Resurrection remains to be done, what he said in October 1918 was entirely consistent with what he had been preaching for almost forty years.

[54] Arthur Conan Doyle, The New Revelation (New York: George H. Doran, 1918), 52. Doyle visited Salt Lake City in May 1923, lecturing one night in the Salt Lake Tabernacle to more than five thousand people. Spiritualism was not an unknown phenomenon to the Latter-day Saints. Years before, the Godbeite movement in Salt Lake had proclaimed it a central part of their new religion, claiming former Apostle Amasa Lyman in the process. See Ronald W. Walker, Wayward Saints: The Godbeites and Brigham Young (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 254–57.

[55] Smith, Gospel Doctrine, 430. For more on this topic, see Michael W. Homer, “Spiritualism and Mormonism: Some Thoughts on Similarities and Differences,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 27, no. 1 (spring 1994): 171–91.

[56] Joseph F. Smith knew all about how decisive the debate over modernism and higher criticism could become. In 1913, after a series of prolonged hearings and debates, Brigham Young University dismissed four professors because of their tendency to accommodate the theory of evolution and to “de-mythologize” the Bible. For a full discussion of this controversy, see Brigham Young University—The First One Hundred Years, ed. Ernest L. Wilkinson, 4 vols. (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1975), 1:412–32.

[57] For more on the rising secularism after the war, see Alan D. Gilbert, The Making of Post-Christian Britain: A History of the Secularization of Modern Society (London: Longman Group, 1980) and Burnham P. Beckwith, The Decline of U.S. Religious Faith 1912–1984 and the Effects of Education and Intelligence on Such Faith (Palo Alto, California: P. A. Beckwith, 1985). According to one study, the decline in church attendance in England since World War I has been precipitous. Between 1885 and 1928, the proportion of the population in England of the age of fifteen and over who were Easter Day communicants in the Church of England never fell below 84 per 1,000. In 1925, it was 90 per 1,000. But since the early 1930s, that number has steadily declined: by 1939 the proportion had dropped to 73 per 1,000, 63 per 1,000 by 1958, and 43 per 1,000 by 1973 (Alan Wilkinson, The Church of England and the First World War [London: SPCK, Holy Trinity Church, 1978], 292). In contrast, Latter-day Saint membership has grown from four hundred thousand to eleven million, and activity rates are higher now than ever before (see Rodney Stark, “The Basis of Mormon Success: A Theological Application,” in Latter-day Saint Social Life: Social Research on the LDS Church and Its Members, ed. James T. Duke [Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1998]: 29–70).