What the Atoning Sacrifice Meant for Jesus

Gerald N. Lund

Gerald N. Lund, “What the Atoning Sacrifice Meant for Jesus,” in My Redeemer Lives! ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and Kent P. Jackson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2011).

Elder Gerald N. Lund was a released member of the Seventy when this book was published.

(Adam Abrams, Gethsemane, © 2008 Adam Abrams.)

(Adam Abrams, Gethsemane, © 2008 Adam Abrams.)

It is always a challenge to talk or write about the Atonement of Jesus Christ. First of all, it is infinite in its scope. It is the most profound and pivotal event in all of eternity. And we are so totally and utterly finite. We can but glimpse its importance and come only to a small understanding of its full meaning for us.

Another problem is the sheer volume of the record of that week. Christ’s ministry lasted three years, or 156 weeks. Thus the final week of His life constitutes only two-tenths of one percent of His ministry, yet that week occupies fully one-third of the total pages of the four Gospels. In a few short pages, I could not even recount the events of that most significant of all weeks in history; therefore, I have chosen to take a somewhat different approach to Easter Week.

Generally at Easter time we talk about Christ’s sacrifice and what it means to us. But I should like to focus more on what the Atonement meant for Jesus. Sometimes we forget that side of the story. Yes, Jesus was the Son of God, but He was also a man. He had a body like ours that needed food and sleep. He had personality and character traits. If He walked too far in one day, His feet would blister. If He hit His thumb while working in the carpenter’s shop, it hurt like fury, and the thumbnail eventually turned black.

It was not just the Son of God who went through that first Easter week, it was also the man Jesus. And knowing that has relevance for us today. So I shall draw just a few glimpses from the scriptures of what those final days must have meant for Him. In doing so, it is my hope that we will deepen our appreciation not only for what He did, but for what He was.

“The Will of the Son Being Swallowed Up in the Will of the Father”

When Abinadi gave his final defense before the wicked King Noah, the prophet testified of the coming Messiah and the atonement He would make for us. One statement he made provides a profound insight into the Savior’s personality and character. “He shall be led, crucified, and slain, the flesh becoming subject even unto death, the will of the Son being swallowed up in the will of the Father” (Mosiah 15:7). That aspect of Christ’s life was true not just in those final hours, but it was the defining statement of His nature.

One of the greatest blessings we have in life is agency—the right to choose what we shall do, where we live, how we act, what we believe. If we grow weary of our employment, we can choose to find other work. If we do not like our neighborhood, we can move. When we find the monotony or burdens of life pressing in, we call in sick or go on vacation or simply just quit and give up. In short, we are free to follow our will. The Savior also had agency, but His will, His wants, His desires, His wishes always came second. As He said in the Garden of Gethsemane, “Not as I will, but as thou wilt” (Matthew 26:39). On another occasion, some of His enemies asked, “Who art thou?” (John 8:25). His answer reflected His total commitment to His Father. He said, “I do nothing of myself; but as my Father hath taught me; . . . I do always those things that please him” (John 8:28–29).

That submission was the hallmark of His life, and had it not been so, the Atonement would never have become reality. Let us think of that the next time we sing, “I’m trying to be like Jesus” or “Lord, I would follow thee.” [1]

“Why Hast Thou Forsaken Me?”

Here is a brief but powerful insight from the New Testament record. One of the most haunting moments occurred on the cross when Jesus suddenly cried out, “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” (Matthew 27:46). Surely much of the ministry of Jesus involved a certain degree of loneliness. Which of His contemporaries could possibly understand what He was and who He was? How many times was He scorned and mocked, ridiculed and reviled? Sometimes even His closest disciples misunderstood what He said or why He did the things He did. In one sense, He was always alone. But there was one great comfort through all of that. Maybe no one else fully understood Him, but His Father did. At least twice during his ministry, He made specific statements about His relationship with the Father, and it is clear that He drew great comfort from this knowledge.

In John 8:29, He said, “He that sent me is with me: the Father hath not left me alone; for I do always those things that please him.” A short time later, He said to the Twelve: “Behold, the hour cometh, yea, is now come, that ye shall be scattered, every man to his own, and shall leave me alone: and yet I am not alone, because the Father is with me” (John 16:32).

As Christ left the Upper Room with His disciples, He seems to have had a clear idea of the ordeal which lay ahead. But He evidently did not foresee this one aspect of the coming trial. It seems to have come as a shock that in that terrible final hour, He was left utterly alone. Even the Father, who had never before left Him alone, withdrew His presence from Him. Elder James E. Talmage described that moment thus:

What mind of man can fathom the significance of that awful cry? It seems, that in addition to the fearful suffering incident to crucifixion, the agony of Gethsemane had recurred, intensified beyond human power to endure. In that bitterest hour the dying Christ was alone, alone in most terrible reality. That the supreme sacrifice of the Son might be consummated in all its fulness, the Father seems to have withdrawn the support of His immediate Presence, leaving to the Savior of men the glory of complete victory over the forces of sin and death. [2]

What it meant for Him at that moment is beyond our capacity to understand. Judging from the anguish, at that point even He did not understand. Later He would understand and use that understanding to succor us. There are times in almost every person’s life when the burdens and anguish become so great that we too cry out, as the Prophet Joseph did from Liberty Jail, “O God, where art thou?” (D&C 121:1). And after His ordeal on the cross, the Savior can answer: “All of these things shall give thee experience, and shall be for thy good. The Son of Man hath descended below them all. Art thou greater than he?” (D&C 122:7–8).

“Abba, Father”

Three of the four Gospel writers—Matthew, Mark, and Luke—include the account of the Savior’s heart-wrenching prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane, where He pled with the Father to remove the terrible cup that He was about to drink. However, Mark adds one detail that is unique to his Gospel. He says that Jesus began His prayer with the words, “Abba, Father” (Mark 14:36). Abba is an Aramaic word which Mark chose not to translate into Greek. It is one of the words for “father.” So why not just render the passage as “Father, Father”? Why leave an Aramaic word in an English translation?

Generally, translators leave in something from the original language because there is no good equivalent in the target language, or because if there is an equivalent, significant nuances of meaning are lost in translation. In this passage, the Greek text actually uses two different words for father, abba and pater. In his extensive work on New Testament word studies, W. E. Vine differentiates between abba and pater in this way: “‘Abba’ is the word framed by the lips of infants, and betokens unreasoning trust; ‘father’ [pater] expresses an intelligent apprehension [or understanding] of the relationship.” [3] In other words, pater is the more formal term of address, typically used as children mature and grow to adulthood. But abba is the more intimate and affectionate form used by small children. Our equivalent in English would be “papa” or “daddy.” [4]

Had the translators rendered the passage literally as “Daddy, Father,” or “Papa, Father,” it would seem a bit jarring to us. We do not address our Heavenly Father in such casual or familiar terms. One scholar explained it in these terms: “Probably to guard against the appearance of too great a familiarity, the writers of the New Testament, instead of using the Greek word, [papa] retained the foreign form Abba to give greater emphasis and dignity.” [5]

But the fact that abba was used by the Savior in His hour of greatest need is of great significance. He spoke to His Father with the familiarity of a child for an adoring and adored parent, but at the same time He also used the more formal, respectful title. Both terms reveal the depth and breadth of their relationship. That simple addition by Mark provides a tender insight into their relationship which only adds greater meaning to that sacred moment.

However, it does much more than that. It reveals something about our own relationship with God that is of prime importance. Note the words of Paul the Apostle: “For as many as are led by the Spirit of God, they are the sons of God. For ye have . . . received the Spirit of adoption, whereby we cry, Abba, Father. The Spirit itself beareth witness with our spirit, that we are the children of God” (Romans 8:14–16). In other words, when we become the sons and daughters of God and are spiritually born again, then we shall have that same intimate but respectful relationship, and it shall be our privilege to call upon God as “Abba, Father.”

A Broken Heart

The Gospel of John is unique in many ways, containing things which Matthew, Mark, and Luke did not include in their Gospels. In describing that horrible day when Jesus was nailed to the cross, John adds one short comment that is not found in the other Gospels but which gives a truly significant insight into Christ’s death.

We often speak of Jesus being crucified, or say that He died on the cross. Indeed, the cross has become almost a universal symbol of His death in the Christian world. What is not as well known is that it is not likely that crucifixion was what killed Jesus.

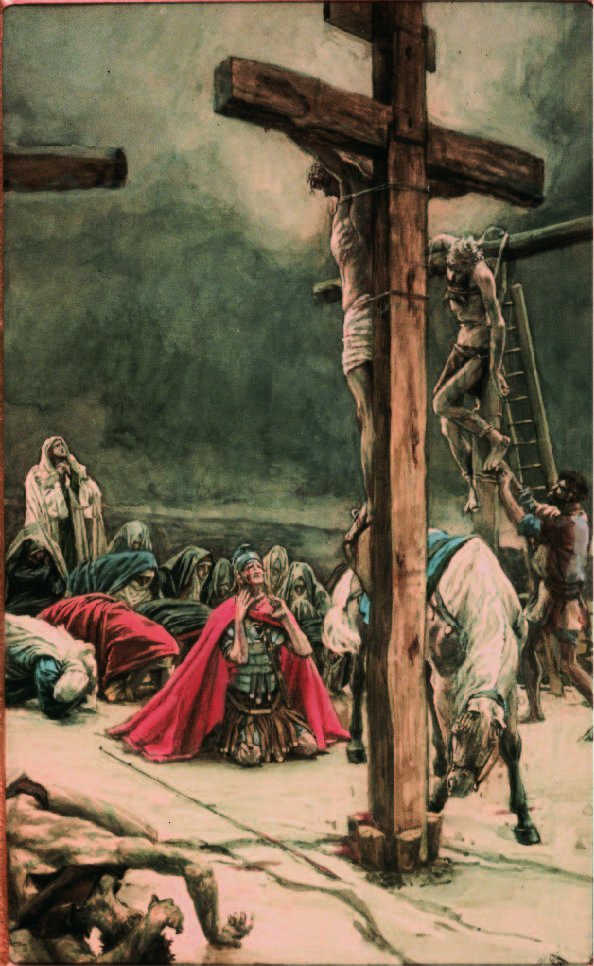

It is not likely that crucifixion was what killed Jesus. (James Tissot, The Confession of Saint Longinus.)

It is not likely that crucifixion was what killed Jesus. (James Tissot, The Confession of Saint Longinus.)

We know that crucifixion was used by the Romans to inflict the maximum amount of pain and suffering by prolonging death. The wounds inflicted by the nails were not fatal, and, though excruciatingly painful, they brought relatively little loss of blood. In a healthy person, death on the cross usually did not come any sooner than forty-eight hours, and in some cases, life persisted for a day or two longer than that. Usually the actual cause of death was a combination of hunger, shock, thirst, infection, exhaustion, and exposure.

A few hours after the Crucifixion, the Jewish leaders begged Pilate to take Jesus and the two others down from the cross because the high holy days of Passover were beginning. The common method for hastening death was to break both of the victim’s legs by striking the shins with a heavy mallet. This additional shock, coupled with the removal of their ability to support themselves to some degree with their feet, brought rapid death.

When the soldiers arrived at Golgotha, they found the two thieves still alive and broke their legs. But to their astonishment, Jesus was already dead, even though it had only been three hours. Evidently, one of the soldiers, either to make sure that Jesus was dead, or to kill Him if He was not, thrust a spear into the Savior’s side. John, who witnessed this, records, “And forthwith came there out blood and water. And he [i.e., John himself] that saw it bare record, and his record is true: and he knoweth that he saith true, that ye might believe” (John 19:34–35).

Talmage comments on this unusual statement of John’s:

If the soldier’s spear was thrust into the left side of the Lord’s body and actually penetrated the heart, the outrush of ‘blood and water’ observed by John is further evidence of a cardiac rupture; for it is known that in the rare instances of death resulting from a breaking of any part of the wall of the heart, blood accumulates within the pericardium, and there undergoes a change by which the corpuscles separate as a partially clotted mass from the almost colorless, watery serum. . . . Great mental stress, poignant emotion either of grief or joy, and intense spiritual struggle are among the recognized causes of heart rupture. [6]

In short, it appears that the actual cause of the Savior’s death was a broken heart, caused not by crucifixion but by the tremendous weight of sorrow and suffering He had endured in order to pay the price for sin.

Once again in the personal details of Christ’s sacrifice there is profound relevance for us. The Apostle Paul likened our attempts to put away the natural man, or the old man of sin, as Paul called it, to the Crucifixion in these words: “Know ye not, that so many of us as were baptized into Jesus Christ were baptized into his death? . . . Knowing this, that our old man is crucified with him, that the body of sin might be destroyed, that henceforth we should not serve sin” (Romans 6:3, 6).

Clearly, Paul speaks metaphorically here, for we do not have to literally die to give up sin—only the natural or sinful part has to be put away. Knowing that Christ did not suffer death from the Crucifixion but from a broken heart, His example becomes the model for how we overcome the natural man.

To the Nephites, the resurrected Christ said, “Ye shall offer for a sacrifice unto me a broken heart and a contrite spirit. And whoso cometh unto me with a broken heart and a contrite spirit, him will I baptize with fire and with the Holy Ghost” (3 Nephi 9:20). To the Saints of our generation, He said, “Thou shalt offer a sacrifice unto the Lord thy God in righteousness, even that of a broken heart and a contrite spirit” (D&C 59:8). This process, which is called being “born again,” requires that there first be a sincere and lasting repentance. But in what way is repentance like unto having a broken heart?

Once again we are indebted to Paul for the answer. Speaking to the Corinthians, he said, “Now I rejoice, . . . that ye sorrowed to repentance: for ye were made sorry after a godly manner. . . . For godly sorrow worketh repentance to salvation not to be repented of [or abandoned]: but the sorrow of the world worketh death” (2 Corinthians 7:9–10).

There are many ways in which a person can be sorry for doing wrong. We can feel sorry because we are caught and suffer punishment. We can regret that our foolish actions bring highly unpleasant consequences with them. For example, Mormon described the sorrowing of his people in those last terrible days before their destruction as the result of the fact that “the Lord would not always suffer them to take happiness in sin” (Mormon 2:13).

President Ezra Taft Benson defined godly sorrow and linked it directly to the concept of a broken heart:

True repentance involves a change of heart and not just a change of behavior (see Alma 5:13). Part of this mighty change of heart is to feel godly sorrow for our sins. This is what is meant by a broken heart and a contrite spirit. . . .

Godly sorrow is a gift of the Spirit. It is a deep realization that our actions have offended our Father and our God. It is the sharp and keen awareness that our behavior caused the Savior, He who knew no sin, even the greatest of all, to endure agony and suffering. Our sins caused Him to bleed at every pore. This very real mental and spiritual anguish is what the scriptures refer to as having ‘a broken heart and a contrite spirit’ (D&C 20:37). Such a spirit is the absolute prerequisite for true repentance. [7]

I should like to repeat one part of that statement: Godly sorrow “is a deep realization that our actions have offended our Father and our God. . . . This very real mental and spiritual anguish is what the scriptures refer to as having ‘a broken heart and a contrite spirit.’”

What a beautiful and marvelous similitude! When Christ took sin upon Himself and suffered for it as if He were Himself guilty of it all, His sorrow and suffering were such that His great heart broke, and He died. And as we truly seek to put off the natural man, the sinful man that dwells inside our hearts, we emulate His example. When we realize that we have offended God’s perfect holiness, that our actions are part of what added to Christ’s suffering, the Spirit creates in us such a deep and piercing sorrow that it is likened unto having a broken heart.

The Condescension of God

These few brief insights—Christ’s will being swallowed up in the will of the Father, the Savior’s agonized cry from the cross, addressing God as “Abba, Father,” and dying from a broken heart—lead us to another profound aspect of Christ’s atoning sacrifice. It is what is called in the scriptures “the condescension of God.” Twice in Nephi’s great vision, an angel used that phrase—once just before Nephi was shown the birth of Jesus, and once as he was shown the trial and death of Jesus (see 1 Nephi 11:16, 26). Let us examine how these two aspects of Christ’s life show His condescension.

The condescension of His birth. Let us again ask the question that sets the theme for this address. When Jesus left the premortal existence and came to earth, we know what it meant for us, but what did that mean for Him? Think about that for a moment. In the premortal life, Jesus was the Firstborn of the Father. Of all the countless billions of the spirit children of our Father, He was the first to be given a spirit body. His intelligence was the greatest of all. He then went on to serve as the great Creator, acting under the direction of the Father.

Let us consider just that aspect of Christ’s premortal role. While there are several scriptures which attest to Christ’s role as the Creator, it is in the Book of Moses that we are shown the extent of His role in the creation: “And worlds without number have I created; and I also created them for mine own purpose; and by the Son I created them, which is mine Only Begotten . . . and innumerable are they unto man. . . . The heavens, they are many, and they cannot be numbered unto man; . . . and there is no end to my works.” (Moses 1:33, 35, 37–38).

Later in the book, we find these astonishing words of Enoch: “And were it possible that man could number the particles of the earth, yea, millions of earths like this, it would not be a beginning to the number of thy creations” (Moses 7:30).

To help you better appreciate the staggering enormity of that statement, let us consider only one tiny indicator of how vastly enormous that number would be. Imagine, if you can, the number of just one kind of particle we find on the earth, what we call a grain of sand. How many grains of sand would there be if you could count every grain on every beach, in every desert, in every gravel pit and river sandbar around the world? And that would not even be a beginning to the number of His creations.

Using a microscope, a telescope, or the naked eye, everywhere we look we see the complexity, the enormity, the beauty and the wonder of the creations of God. I briefly note only a few.

- There are over fifty thousand different species of spiders, including one that spins its web beneath the water and uses it like a diving bell, one that can jump forty times its own length from a standing position, or the bolas spider, which attaches a sticky blob to a single strand of webbing, then hurls it at passing moths, much like a fisherman casting for fish.

- With the great Mount Palomar telescope in California, astronomers can count over a million galaxies in the bowl of the Big Dipper. Not stars. Galaxies of stars.

- The lowly ant can lift as much as fifty times its own weight and carry it for some distance. That is the equivalent of a two-hundred-pound man bench pressing ten thousand pounds, or five tons.

- The trunk of an elephant is strong enough to lift a six-hundred-pound log and delicate enough to pick up a coin from a sidewalk.

- The design and colors in the tail feathers of the peacock are a marvelous work of art.

- The world produces enough food to feed six billion people every day.

- The human heart beats an average of fifty thousand times a day, or about one and a half billion times in a lifetime.

- The human fetus begins as a single sperm and egg, and in just under nine months develops into a fully formed human being.

- As part of that development, when the fetus is just seven weeks along, it begins to develop brains cells. At that point it is only one and half inches long and weighs less than half an ounce, but it produces new brains cells at the rate of more than one hundred thousand times every minute, or sixteen hundred new cells every second!

The miracles of creation are omnipresent and stunning in their wonder. And all of this was done under the power and direction of the Son of God. That was the station and status of the premortal Jesus. And He left all of that glory and power and perfection and took upon Himself the body of a mortal, subject to pain and weariness, hunger and thirst, blisters and boils and viruses—and death. To willingly undergo the transformation from godhood to manhood was indeed an act of tremendous condescension.

The condescension of His trial and crucifixion. But that is only one manifestation of Christ’s condescension. In his vision, Nephi saw “the Lamb of God, that he was taken by the people; yea, the Son of the everlasting God was judged of the world; and I saw and bear record. And I, Nephi, saw that he was lifted up upon the cross and slain for the sins of the world” (1 Nephi 11:32–33). The irony in that statement is incredible. Wicked and evil and puny men put the Son of the God on trial and sent Him to the cross for blasphemy and thought that they were doing God a service when they did so.

This part of the vision so profoundly influenced Nephi, that later he referred to those last hours of Christ in this way: “And the world, because of their iniquity, shall judge him to be a thing of naught; wherefore they scourge him, and he suffereth it; and they smite him, and he suffereth it. Yea, they spit upon him, and he suffereth it, because of his loving kindness and his long-suffering towards the children of men” (1 Nephi 19:9)

Remember who and what Jesus was before He came to earth. Also consider the miracles that He had wrought during His mortal ministry—healing the blind, stilling the storm, cleansing the leper, making crippled limbs function, raising a man who had been dead for four days. In that context, think of this. When the Son of God was brought before those arrogant and hypocritical leaders of the Jews, they made mock of Him. They dared Him to prophesy, cuffed Him with the back of their hands, and one even spit into His face. And Jesus suffered it!

Knowing who He was and the power at His command, at any moment of that terrible ordeal, He could have uttered a single word and brought down fire on the Sanhedrin as He did on the priests of Baal, or utterly destroyed Jerusalem as He did Sodom or Gomorrah. Or for that matter, since He had the power to create the earth, surely He had the power to destroy it as well. But He chose not to. He chose to endure the humiliation, the pain, the spittle running down His cheek, and, as Nephi said, “he suffereth it” because of His great love for us. Is it any wonder that the angel said to Nephi as he witnessed these scenes in vision, “Behold the condescension of God!” (1 Nephi 11:26).

How Do We Ever Repay Such a Gift?

As we consider these various insights into what the Atonement meant for Jesus personally, we are led to exclaim, “What could I ever possibly do to repay the Father and the Son for all of this?” It is a valid question, and one born of humility. But in reality, the answer is that we can do nothing that would repay God and Christ for what they did. In the true meaning of the word repay, what can we give to God that He does not already have? How can the finite repay the infinite? It simply is not possible.

But that, of course, does not imply that we can do nothing. There are offerings we can make which will be acceptable to them and received with joy. Elder Talmage, who spent much of his life studying the life and work of the Savior, answered this dilemma in a wonderful parable which he called “The Parable of the Grateful Cat.”

He tells the true story of a famous naturalist in England who was to be honored for his scientific achievements. He was invited to a great country estate where the awards were to be given. The morning after his arrival, as was his custom, he arose early and went out for a walk in the grounds. As he approached a millpond, he came across two boys, children of servants who served the wealthy estate owners. The boys were in the process of drowning kittens in weighted sacks in the pond.

As it turned out, the mistress of the estate had an old mother cat who had given birth to another litter of kittens. While the lady of the estate wanted to keep the mother cat, she did not want any more cats around and so asked the boys to get rid of the kittens. When the naturalist arrived on the scene, two of the five kittens were already in the water and drowning. The mother cat was nearby, running frantically back and forth, mewing piteously as she watched her little ones being disposed of. The naturalist intervened, paying the boys and promising them that they would not get into trouble if they let him take the remaining kittens back to his cottage. Elder Talmage describes what happened next: “The mother cat . . . recognized the man as the deliverer of her three children. . . . As he carried the kittens she trotted along—sometimes following, sometimes alongside, occasionally rubbing against him with grateful yet mournful purrs.”

What followed the next day formed the basis of the parable: “The gentleman was seated in his parlor on the ground floor, in the midst of a notable company. Many people had gathered to do honor to the distinguished naturalist. The cat came in. In her mouth she carried a large, fat mouse, not dead, but still feebly struggling under the pains of torturous capture. She laid her panting and well-nigh expiring prey at the feet of the man who had saved her kittens. What think you of the offering, and of the purpose that prompted the act? A live mouse, fleshy and fat! Within the cat’s power of possible estimation and judgment it was a superlative gift.”

Now comes the lesson for us. Elder Talmage concludes with this: “Are not our offerings to the Lord—our tithes and our other freewill gifts—as thoroughly unnecessary to His needs as was the mouse to the scientist? . . . Thanks be to God that He gages the offerings and sacrifices of His children by the standard of their physical ability and honest intent rather than by . . . His esteemed station. Verily He is God with us; and He both understands and accepts our motives and righteous desires. Our need to serve God is incalculably greater than His need for our service.” [8]

So what if the mouse brought no personal profit to the scientist? What if he was far above and far removed from the gift of a half-expired rodent? Surely his heart swelled with a deep and lasting joy at such an offering from the mother cat.

While it is true that we cannot repay God in the strictest sense of that word, there are offerings we can make that will be pleasing to Him. Here are four that the scriptures suggest are especially pleasing to God.

-

Acknowledgment. In the fifty-ninth section of the Doctrine and Covenants we are told, “And in nothing doth man offend God, or against none is his wrath kindled, save those who confess not his hand in all things” (v. 21). How quick is mankind to blame God for the natural disasters and sufferings we find in the world, yet how slow to acknowledge His hand in the myriad goodness of life. For the Lord to say that such thoughtlessness kindles His wrath is an indication of how important this acknowledgment is to Him and to us.

-

Acceptance. Later in the Doctrine and Covenants the Lord says this: “For what doth it profit a man if a gift is bestowed upon him, and he receive not the gift? Behold, he rejoices not in that which is given unto him, neither rejoices in him who is the giver of the gift” (D&C 88:33). How tragic that God so loved the world that He gave His Only Begotten Son, and the world is so blind and apathetic that it does not care. It turns away from the gift as if it were of no consequence whatever.

-

Gratitude. Several scriptures speak of the importance of gratitude. In Psalms we read, “Serve the Lord with gladness: come before his presence with singing. . . . Enter into his gates with thanksgiving, and into his courts with praise: be thankful unto him, and bless his name” (Psalm 100:2, 4). In a modern revelation we are commanded to “thank the Lord thy God in all things” (D&C 59:7). Gratitude, which is expressed in both word and deed, is another way of acknowledging what God has done for us and accepting the gifts He extends to us.

-

Remembrance. Finally there is remembrance, which is perhaps the most important of them all. Some years ago, after I taught a class on the Atonement, one of the members, who was a practicing physician, handed me an article. He said, “I think in light of what you taught us tonight, you will find this interesting.” To my surprise, the article was from a medical journal called Private Practice and had nothing to do with religion, let alone Christ. In fact, it was an article about a mountain climbing school in Colorado that catered to doctors and other professional people. I was puzzled as I read through it, wondering why he had given it to me.

Then I came to something he had marked near the end of the article, and then I understood. It was another parable, of sorts, though it was not written with that intent. The author of the article was interviewing the man who ran the climbing school, whose name was Czenkusch. They were talking about one of the key techniques in rock climbing, knowing as “belaying.” To put it simply, belaying is the process by which one climber secures another climber so that he or she can safely ascend the rock face. This is done by having the lead climber loop a rope around his or her own body, then keeping the rope taut as the climber ascends so if there is a slip, the person on belay does not fall.

Understanding that much, here then is the paragraph that the doctor had marked for me:

Belaying has brought Czenkusch his best and worse moments in climbing. Czenkusch once fell from a high precipice, yanking out three mechanical supports and pulling his belayer off a ledge. He was stopped, upside down, 10 feet from the ground when his spread-eagled belayer arrested the fall with the strength of his outstretched arms. “Don saved my life,” says Czenkusch. “How do you respond to a guy like that? Give him a used climbing rope for Christmas? No, you remember him. You always remember him.” [9]

What a marvelous analogy! The Savior, by the power of His own life and infinite sacrifice, is able to arrest our fall and save us from death. How do we thank Him for that? A new climbing rope is not any more needed by God than a fat field mouse. But we can vow that we shall never forget the gift. And in fact, this principle is so important that God asks to put ourselves under covenant each and every week that we will always remember Him.

There are thirty-three verses in the standard works that specifically describe the ordinance of the sacrament. The words remember and remembrance are used twenty-three times in those verses. For example, when Jesus visited the Nephites and instituted the sacrament among them, He told them to partake of the bread and wine “in remembrance” of His body and His blood, and four different times He said, “Always remember me” (3 Nephi 18:7, 11). That pattern is repeated in the sacramental prayers we offer each Sunday. With the bread, we witness to the Father that we are “willing to . . . always remember him,” and with the water, we witness that we “do always remember him” (D&C 20:77, 79; emphasis added). And the promise is that if we honor those covenants, then another inestimable gift becomes ours: We will always have His Spirit to be with us.

What is it about the simple act of remembrance that carries such much significance? Because it is in remembering that we are impelled to action. Remembrance becomes the motivating, driving force that helps us strive to be more like the Father and the Son. It is in remembrance that we find the power to be a better person. Jesus taught the disciples, “If ye love me, keep my commandments” (John 14:15). When we remember all that the Father and Son have done for us, it rekindles and renews our love for them, and that renewed love becomes a powerful agent for change.

Let me close with a poem that is a gentle and yet poignant reminder of the importance of remembrance, especially at this Easter season.

When Jesus came to Golgotha they hanged him on a tree,

They drove great nails through hands and feet, and made a Calvary;

They crowned Him with a crown of thorns, red were his wounds, and deep,

For those were crude and cruel days, and human flesh was cheap.

When Jesus came to [our town] they simply passed Him by,

They never hurt a hair of Him, they only let Him die;

For men had grown more tender, and they would not give Him pain,

They only just passed down the street, and left Him in the rain. [10]

When I first began asking myself the question, “What did the Atonement mean for Jesus personally?” I found my understanding and appreciation for Him and for what He did increasing in great measure. I found my gratitude deepening, my understanding expanding, and my heart softening. So may we, at this Easter season, remember the personal side of the Atonement as well as the universal side. It was Jesus the man who had to actually carry out the mission of Jesus the Christ and totally submit His will to God the Father. Who can adequately describe what that meant for Him? But thanks be to the Lord that He drank of that bitter cup and, in the end, is able to say, “I partook and finished my preparations unto the children of men” (D&C 19:19). May we recommit ourselves to acknowledging His gift, accepting it with gratitude and always remembering Him.

© Intellectual Reserve Inc.

Notes

[1] Janice Kapp Perry, “I’m Trying to Be like Jesus,” Children’s Songbook (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1985), 78–79; Susan Evans McCloud, “Lord, I Would Follow Thee,” Hymns (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1985), no. 220.

[2] James E. Talmage, Jesus the Christ (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1962), 612.

[3] W. E. Vine, An Expository Dictionary of New Testament Words (Nashville: T. Nelson, 1981), 9.

[4] Tremper Longman and David E. Garland, The Expositor’s Bible Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2005), 8:764; 10:473.

[5] Samuel Fallows, Andrew Constantinides Zenos, and Herbert Lockwood Willett, eds., The Popular and Critical Bible Encyclopædia and Scriptural Dictionary (Chicago: Howard-Severance, 1912), 10.

[6] Talmage, Jesus the Christ, 620.

[7] The Teachings of Ezra Taft Benson (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1988), 71–72.

[8] James E. Talmage, “The Parable of the Grateful Cat,” Improvement Era, August 1916, 875–76.

[9] Quoted in Eric G. Anderson, “The Vertical Wilderness,” Private Practice, November 1979, 21.

[10] “Indifference,” in The Unutterable Beauty: The Collected Poetry of G. A. Studdert Kennedy (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1928), 24.