William Clayton and the Records of Church History

James B. Allen

James B. Allen, “William Clayton and the Records of Church History,” in Preserving the History of the Latter-day Saints, ed. Richard E. Turley Jr. and Steven C. Harper (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2010), 83–114.

James B. Allen is a former assistant church historian of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and professor emeritus of history, Brigham Young University.

A month before his martyrdom, the Prophet Joseph Smith remarked, “For the last three years . . . I have kept several good, faithful, and efficient clerks in constant employ; they have accompanied me everywhere, and carefully kept my history, and they have written down what I have done, where I have been, and what I have said.” [1] One of those clerks was twenty-nine-year-old William Clayton.

William Clayton is an obscure figure to many Latter-day Saints, as are most of Joseph Smith’s clerks and scribes. If his name is recognized at all, it is likely due to his authorship of one of Mormonism’s most beloved hymns, “Come, Come, Ye Saints,” or perhaps his remarkable pioneer journal. Yet if not for Clayton and many people like him, we would have practically no recorded history of the early church. This paper will attempt to shed light on this important but little-known record keeper from the past.

A Sacred Trust

On January 29, 1845, seven months after the Prophet’s death, William Clayton spent nearly all day working at the Church Recorder’s Office. He interrupted his activities, however, to attend and record the proceedings of a special meeting conducted by President Brigham Young of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. Also in attendance were two other members of the quorum, Heber C. Kimball and Orson Hyde; the two trustees-in-trust of the church, Newel K. Whitney and George Miller; and two members of the Nauvoo Temple committee, Alpheas Cutler and Reynolds Cahoon. The purpose of the meeting was to consider a special request by the members of the temple committee. Their assignment, Reynolds Cahoon explained, required considerable extra effort, including working on Sundays, going to bed late, and getting up at all hours of the night to serve those who brought in property for the temple. They wanted this extra work, for which they were not paid, to be entered on the books as full payment of their tithing. After all, the committee members explained, Joseph Smith intended for them to have this tithing arrangement when they were first asked to serve.

During the discussion, Brigham Young said that he and the other church leaders were determined to carry out Joseph’s wishes in every respect. He also commented on the “unceasing and indefatigable labors of the Twelve and others” who were spending all their time working for the benefit of the church. He recommended that tithing should be entered as paid in full for the committee and the Twelve, and everyone agreed. William Clayton then made the same request. In the end, all the apostles, the trustees, members of the temple committee, and William Clayton, as well as the late Joseph and Hyrum Smith and city marshal John P. Green, had their tithing shown on the record as paid in full.

For William Clayton, perhaps the most spiritually satisfying part of the meeting happened after the decision about tithing was made. At that point Elders Young and Kimball gave him a special blessing in which he was told that “he should be a scribe for this church in the resurrection.” He made note of the blessing not only in the minutes of the meeting but also in his personal journal. [2] Keeping the records of the church was a sacred trust to him, one in which he had reveled since he was appointed as a scribe to the Prophet in 1842. To have his labors and abilities so recognized by church leaders, with the assurance that this recognition would continue in the eternities, must have given him exhilaration that little else could match.

Dedicated and Industrious Saint

William Clayton grew up in Penwortham, England, where, at the time of his conversion, he worked as a clerk in a factory. Of a meticulous, methodical nature, he was a gifted musician (he played the violin, drum, and French horn), a lover of fine craftsmanship, and a devoted husband and father. On October 21, 1837, he was baptized by Heber C. Kimball, who was leading the first Latter-day Saint mission to England and remained Clayton’s friend and confidant until Kimball’s death in 1868. [3]

Clayton made rapid progress in his newfound faith, and church leaders quickly recognized his talents. Less than six months after his conversion he was ordained a high priest and made a member of the British Mission presidency. In October 1838 he quit his job to work full time in his ministry. Almost immediately he was assigned to serve in Manchester, where he spent the next two years and built up the second largest congregation in England. In January 1840 he began keeping a diary, which is now an important source for the early history of the church in that area. [4] In addition, members of the Quorum of the Twelve in England assigned him to be the official conference clerk at the April and July 1840 general conferences.

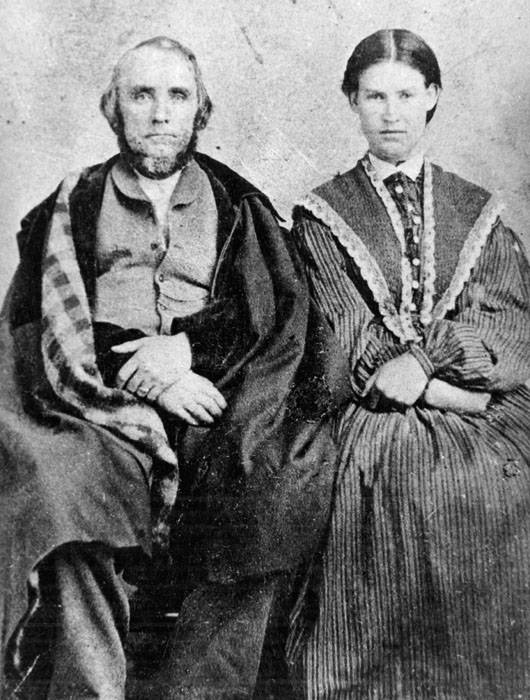

William Clayton and his wife Diantha. (Courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.)

William Clayton and his wife Diantha. (Courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.)

Clayton and his family left England early in September 1840, arriving at Nauvoo, Illinois, on November 24. The diary Clayton began in Manchester continues with a remarkably detailed account of the emigration process and life aboard an emigrant ship. It also provides some interesting though brief details of life in Zarahemla, Iowa, the community across the river from Nauvoo, where Hyrum Smith encouraged Clayton to settle and which Joseph Smith once predicted would become as great as Nauvoo itself. When a stake was organized in Zarahemla, Clayton was at first a member of the high council and later, as might be expected, the stake clerk.

Clayton was miserable in Zarahemla, however, and failed in his effort to become a self-sufficient Iowa farmer— just as Joseph Smith’s high hopes for the Iowa settlement also eventually failed. On December 14, 1841, he moved back across the river to Nauvoo, where he soon found himself engaged in work that was more in tune with his competence and natural skills: clerking and record keeping.

On February 10, 1842, Heber C. Kimball told Clayton to report to Joseph Smith’s office. Willard Richards was acting as recorder for the Nauvoo Temple, but he was overworked and needed an assistant. Joseph Smith gave Clayton the assignment. On June 29, all the work of the Prophet’s office was turned over to Clayton, as Richards had to travel east. Then, on September 3, Joseph called him in and said, “Brother Clayton I want you to take care of the records and papers, and from this time I appoint you Temple Recorder, and when I have any revelations to write, you shall write them.” [5] The assignment must have been deeply satisfying to the twenty-eight-year old Clayton, who had been an ardent, unquestioning disciple of the Prophet since they first met and would continue to be so throughout his life. With this assignment, he would be in the almost constant company of Joseph Smith.

The closeness that existed between the two men was indicated by a note sent by the Prophet about a month after Clayton was appointed temple recorder. Clayton had previously asked for permission to do something (the nature of which is unknown), and on October 7—the same day Joseph temporarily left Nauvoo to escape from Missourians on their way to capture him—Joseph hurriedly wrote a curious but heartwarming response:

Brother Clayton

Dear Sir

I received your Short note I reply in Short be shure you are right and then go ahead David Crocket like and now Johnathan what shall I write more only that I am well and am your best Friend

Joseph Smith to William Clayton

or David

or his mark

——X—— [6]

Clayton undoubtedly felt honored to have their friendship compared to that of David and Jonathan. Like Jonathan of old, he would do anything for this modern David.

Clayton’s life in America was exceptionally busy. In Nauvoo he was city treasurer, recorder and clerk of the Nauvoo City Council, secretary pro tem of the Nauvoo Masonic Lodge, an officer of the Nauvoo Music Association, a member of the committee responsible for erecting the Music Hall, and a member of the Nauvoo brass band. In 1844 he became a member of Joseph Smith’s private prayer circle, where the temple ordinances were first introduced. That same year he was invited to become part of the somewhat secretive Council of Fifty, for which he kept the minutes. He also took time to build a brick home, where he lived for the last two years of his time in Nauvoo. After Joseph Smith introduced to him the principle of plural marriage, the married Clayton took on four additional wives. One soon left him, but when he was forced to leave Nauvoo in February 1846, he was accompanied by three wives, four children, a mother-in-law, and a few other in-laws, while another pregnant wife remained temporarily behind.

In Utah, Clayton became one of Salt Lake City’s most prominent and well-respected citizens. He built an adobe home just two blocks west of Brigham Young’s estate and was granted U.S. citizenship in 1853. He no longer worked full time for the church, though he was employed for a short while in the church’s mint in Salt Lake City, making coins from California gold. He also continued to work part time with the financial records of the church, and at least into the 1860s it was he who read the financial report of the trustee-in-trust in general conference. Yet he increasingly directed much of his personal energy into private business and public service. He needed to, for after marrying five additional wives, he had many mouths to feed. In total, he was the husband of ten women and father of forty-two children, though four of his wives left him for various reasons. When he died at age sixty-five, he left four living widows, thirty-three living children ranging in age from ten to forty-three, and one child on the way.

Clayton’s private and public business activities were highly varied. In 1850 he set up a bookshop in Salt Lake City’s Council House. He also opened a boarding house for emigrants who were passing through. In 1849 he was appointed public auditor for the State of Deseret, and in 1852, after the Territory of Utah was organized, he was appointed territorial auditor as well as territorial recorder of marks and brands. He was reappointed to these positions after returning from his 1852–53 mission to England and continued in this service until his death in 1879.

Neither of these positions paid enough to sustain all his needs, and so he took on whatever additional work he could. In 1867 he was appointed treasurer of the newly incorporated Deseret Telegraph Company. With encouragement from Brigham Young, he established a foreign collection agency intended to collect money in Europe for immigrants who had been unable to collect from those who owed them. When Zion’s Cooperative Mercantile Institution (ZCMI) was established in 1868, Clayton became its first secretary. He threw himself into the new cooperative effort so intently that it consumed nearly all his time and forced him to give up nearly all his other businesses. He finally resigned in 1871 and went into the stock business to try to increase his earnings. He also ventured into such private business efforts as filing land claims, acting as an attorney, lending money, merchandising, working in the lumber business, farming, and speculating in mining. Some of these businesses, including some partnerships, did not serve him well, and he was never really comfortable financially.

At the same time, Clayton’s talents were recognized by Brigham Young, who tried to help him reestablish some of his businesses after he left ZCMI. One way was by introducing him to the School of the Prophets on November 10, 1873, where he was unanimously admitted as a member. In introducing him, President Young described him “as the most capable man in the community to make out Wills in strict conformity to law and recommended the bretheren to avail themselves of his services.” [7]

Record Keeping

Clayton kept numerous kinds of records. Some were secular in nature, while others were directly involved with Joseph Smith and the church. He thought of these, including his journals, as sacred records that would help preserve for all time the workings and activities of the kingdom of God.

Nothing was intentionally whitewashed. Some of Clayton’s records, especially his personal journals and letters, are filled with comments on various problems and controversies within the church, and even criticism of some leaders. Nevertheless, his devotion to Joseph Smith probably blinded him to any of the Prophet’s weaknesses. The Prophet came off almost perfect in anything Clayton wrote about him. “If I were in England,” he wrote to his friends in Manchester in December 1840, “I would raise my voice and testify that Joseph is a man of God, which will roll forth unto the ends of the earth and gather together all the good there is on the earth.” He also wrote that the Prophet was “no friend to iniquity but cuts at it wherever he sees it. . . . He has a great measure of the spirit of God. . . . He says ‘I am a man of like passions with yourselves,’ but truly I wish I was such a man.” [8]

Clayton wrote to William Hardman in March 1842, “My faith in this doctrine, and in the prophet and officers is firm, unshaken, and unmoved; nay, rather, it is strengthened and settled firmer than ever. . . . For me to write any thing concerning the character of president Joseph Smith would be superfluous. All evil reports concerning him I treat with utter contempt. . . . I will add that, the more I am with him, the more I love him; the more I know of him, and the more confidence I have in him; and I am sorry that people should give heed to evil reports concerning him, when we all know the great service he has rendered the church.” [9] Such was the Joseph Smith who appeared in anything Clayton wrote.

It may be that some of Clayton’s records are lost, but here is a brief review of the extant records that directly reflect various aspects of the history of the church.

Personal journal from Manchester to Nauvoo. As mentioned, Clayton began keeping his personal journal in January 1840 while doing full-time missionary work in Manchester. It is a marvelously detailed volume that reveals the concerns and problems as well as the brotherhood and spirituality of the Manchester Saints, along with Clayton’s own selflessness and sense of responsibility as a church leader. Through this journal we see different sides of human nature as expressed within that early Mormon community. We see working-class people with all their foibles and problems but also with faith and concern for each other. We see their love for and generosity to William Clayton, and we see his gratitude as he frequently recorded the food and even water they gave when he visited them. We see him weeping at times over the problems faced by some branch members. And we also see him struggling to overcome weaknesses of his own.

Beyond all that, the diary provides wonderful insight into the process of emigration, as Clayton describes in detail the preparations he and his family made as well as the voyage across the ocean. After that, the diary becomes more sketchy, but it still provides insight into the problems of Zarahemla and Clayton’s decision to leave. It ends on February 18, 1842, with Clayton listening as “Joseph read a great portion of his history.” [10]

Nauvoo journals. Clayton made the first entry in his three Nauvoo journals on November 27, 1842. For some reason there is a more than eight-month-long gap after the end of the Manchester journal, though it is possible, even probable, that Clayton kept some kind of record that has been lost. But the Nauvoo journals provide intimate details of both the secular and spiritual life of Nauvoo through the eyes of one of Joseph Smith’s most devoted followers. The journals are a bit difficult to follow, for the entries are not always strictly chronological. Apparently Clayton began writing in one journal, moved to another for some reason, and then moved back to the original. As a result, the researcher must move back and forth between volumes. Sometimes there are two entries for the same day. It is not clear why.

Nevertheless, the journals are a tremendously important though still somewhat untapped source for insights into various aspects of Nauvoo life as well as the life of Joseph Smith. Clayton was candid about the problems as well as the positive things he saw in Nauvoo. Through his eyes we see the building of the temple and the activities of the Quorum of the Anointed and the Council of Fifty. We learn about Joseph Smith’s public as well as private life, his problems and frequent need to flee Nauvoo to escape his enemies, his business activities, and the events leading to the Martyrdom. We also learn about plural marriage and what it meant to William Clayton.

Clayton spent considerable time assisting the Prophet in his real-estate business and other secular activities. The land office business probably consumed more of Clayton’s time than any other business activity, as he was constantly looking at property, showing and selling lots, meeting land agents, making out-of-town business trips for the Prophet, and keeping the records. He reported on much of this work, though often tersely, in his Nauvoo journals. On occasion he went to Carthage to pay taxes, he sometimes went on other trips to obtain supplies, and he frequently spent time examining the books of various business ventures. On September 21, 1843, for example, Joseph Smith instructed him to spend the next month on the Maid of Iowa, a little stern-wheeler the Prophet partly owned, to set in order its books. Clayton stayed there only a few days, but the fact that Joseph trusted him with such errands was a source of great satisfaction.

Clayton’s multifaceted temperament may be seen in the “Reflections” he recorded on New Year’s Day, 1845. Still agonizing over the brutal murder of Joseph Smith, he described the problems of 1844 in language that oozed bitterness and disgust at the “ungodly generation” that allowed it all to happen. Nevertheless, he saw the Martyrdom of the Prophet as fulfilling at least some important purpose. It would permanently stain the wicked state of Illinois “with the innocent blood of two of the best men who ever lived on the earth,” and it would indelibly write in the hearts of the Saints the memory of that horrible day. In this, at least, Clayton was prophetic, for the story of the Martyrdom has taken its place alongside the First Vision and the coming forth of the Book of Mormon as one of the three most oft-repeated stories in Mormon piety.

Clayton’s year-end reflections were not all negative. He was delighted that he had received two new “companions,” by which he meant two new wives, Margaret Moon and Alice Hardman. He also had a “good prospect of adding another crown to my family which is a source of great consolation to me.” Here he referred to sixteen-year-old Diantha Farr, whom he would marry on January 9. He was also thankful that the Saints were united in sustaining the Twelve as leaders and that, on the whole, the year ended “with the blessing of the Almighty God in the midst of his Saints and their never seemed to be a better feeling than at present.” All this and more, including a long but tender prayer of thanksgiving for all his blessings, reveals much about Clayton himself as well as about life among the Saints in Nauvoo.

As one of Joseph Smith’s scribes, Clayton was on the committee that originally began to prepare Joseph Smith’s History of the Church for publication. It is well known that much of this history was not written or dictated by Joseph himself but rather was based on journal entries of his scribes and other people. When these entries were made part of the History, the third-person references to Joseph were simply changed to the first person, an accepted practice at the time. Other changes were made to the text, though they usually were minor. George A. Smith and Wilford Woodruff finished the work in 1856 and published it serially in the Deseret News. A half-century later, B. H. Roberts edited the text, and the church published it in six volumes. Clayton’s Nauvoo journals were among the valuable resources for this history. [11]

For example, some of the revelations now included in the History and in the Doctrine and Covenants were originally recorded in Clayton’s journals. On the evening of February 9, 1843, for instance, Clayton was at the home of Joseph Smith, along with several other people, when the Prophet gave them historical as well as doctrinal instruction. Among other things, he told them of the two kinds of beings in heaven: angels, or resurrected beings, and the spirits of just men “made perfect.” He then described three keys by which they could distinguish between angels, spirits of just men, or “the devil as an angel of light.” The entry in Clayton’s journal became, practically verbatim, the entry in the History and, later, section 129 of the Doctrine and Covenants. Something similar is true for much of section 130, recorded on April 2, 1843, as well as a few other sections.

Some of the entries in the History, based on Clayton’s journal, reveal the potential problems with this kind of history. The story of the infamous Kinderhook plates is an example. On May 1, 1843, Clayton recorded the following:

I have seen 6 brass plates which were found in Adams County by some persons who were digging in a mound They found a skeleton about 6 feet from the surface of the earth which was 9 foot high [tracing of plate] The plates were on the breast of the skeleton. This diagram shows the size of the plates being drawn on the edge of one of them. They are covered with ancient characters of language containing from 30 to 40 on each side of the plates. Prest J. has translated a portion and says they contain the history of the person with whom they were found & he was a descendant of Ham through the loins of Pharaoh king of Egypt, and that he received his kingdom from the ruler of heaven & earth. [12]

That same entry, with some slight modifications, appeared in the History as follows:

I insert fac-similes of the six brass plates found near Kinderhook, in Pike county, Illinois, on April 23, by Mr. Robert Wiley and others, while excavating a large mound. They found a skeleton about six feet from the surface of the earth, which must have stood nine feet high. The plates were found on the breast of the skeleton and were covered on both sides with ancient characters.

I have translated a portion of them, and find they contain the history of the person with whom they were found. He was a descendant of Ham, through the loins of Pharaoh, king of Egypt, and that he received his kingdom from the Ruler of heaven and earth. [13]

The problem here is that the Kinderhook plates were a hoax, and because we know this, the entry seems to show that Joseph Smith was hopelessly duped. It must be noted, however, that in his diary Clayton did not quote Joseph directly—he only reported what he thought was happening. Whether Joseph actually told Clayton that he had translated the plates, or whether Clayton was simply reporting what he heard from a variety of sources, is not clear. The latter appears to be the case, especially when one realizes that Clayton’s account contains several inaccuracies. The so-called “discovery” took place in Pike County, not Adams County, and there was no skeleton with the plates, only some bones.

Further, William Clayton’s account is not consistent with a similar account by Parley P. Pratt, which was also probably obtained by hearsay rather than from the Prophet himself. There is no evidence of any direct statement by Joseph Smith about the authenticity of the plates and no evidence that he ever attempted a translation. As historian Stanley B. Kimball has demonstrated, all kinds of stories about the plates were circulating, but Joseph Smith did not get involved with the plates at all. [14] What is clear is simply that the unfortunate entry got into the History before any of its editors knew the truth.

A different kind of problem arises from an account in the History that was reported to have come from Clayton’s journal but that actually did not—at least not from the journals now extant. On May 18, 1843, Joseph Smith and William Clayton were in Carthage, where they dined with Judge Stephen A. Douglas at the home of Sheriff Jacob Backenstos. Some of that conversation is recorded in Clayton’s journal, but not the way it later appeared in the History. However, in putting the conversation in the History, the editors did not follow their usual pattern of entering whatever they could gather without citing the source. Instead, they took pains to state that “the following brief account . . . is from the journal of William Clayton, who was present.” That account, which is not actually in Clayton’s Nauvoo journal, includes the now-famous statement: “Judge, you will aspire to the presidency of the United States; and if ever you turn your hand against me or the Latter-day Saints, you will feel the weight of the hand of [the] Almighty upon you; . . . for the conversation of this day will stick to you through life.” [15]

The question is where this expanded version of Clayton’s original entry came from. If, somehow, it really came from Clayton, there are only two possibilities. One is that Clayton wrote in more than one journal that day, perhaps in a source that is no longer extant. The other is simply that Clayton, who was still working with the church historians when they were putting all this together, was asked about the prophecy and, drawing on a vivid memory of the occasion, provided the expanded account. It is certainly possible that the account reflected the gist of that dramatic confrontation, even after many years.

Beyond what he wrote in his journals, Clayton also recorded many other important words of Joseph Smith. The famous King Follett sermon, for example, was eventually amalgamated and placed into the History from four different sources, including a transcription by Clayton. In addition, Clayton recorded the famous revelation on marriage, now known as section 132 of the Doctrine and Covenants.

Clayton’s Nauvoo journals end on January 30, 1846, as Clayton was preparing to leave Nauvoo and head west.

Pioneer journal. Clayton’s most well known and widely available contribution to church history is the journal he began on February 8, 1846, and ended on October 21, 1847. It was published by the Clayton Family Association in 1921 with the title William Clayton’s Journal and has been republished several times since then. One of the finest firsthand accounts of the memorable crossing of the plains, it allows the reader to see the experience through the eyes of one who was not a leader but, rather, a faithful follower and veritable workhorse in his commitment to building the kingdom. [16]

Clayton seemed to know that his pioneer journal would be read by future Saints, and one can see a kind of historic sense in many of his entries. For one thing, possibly to satisfy what he thought would be the natural curiosity of his readers, he recorded the now-famous tally in the 1847 pioneer company of 143 men and boys, 3 women, 2 children, and “72 wagons, 93 horses, 52 mules, 66 oxen, 19 cows, and 17 dogs, and chickens.” [17]

Included in the journal are such significant stories as the crossing of the Mississippi River in midwinter; the terrible conditions on the plains of Iowa; the events that led to Clayton’s writing of “Come, Come, Ye Saints”; Clayton’s difficulties in taking care of his family and personal needs while at the same time writing for Heber C. Kimball, making maps for Willard Richards, and acting as camp clerk while crossing Iowa; the settlement at Winter Quarters; the experiences of the vanguard company that scouted out the trail to the Great Basin; Clayton keeping an accurate record of the mileage they traveled each day from Winter Quarters to the Salt Lake Valley and eventually contributing to the construction of the pioneer “roadometer”; the events on the return trip he and several others made to Winter Quarters; and the story of his planning and writing the important Latter-day Saints’ Emigrants’ Guide. [18]

Southern exploring expedition. Clayton apparently wrote only two small journals after the conclusion of the pioneer journal—at least, only two exist today. One was a short journal he kept in 1852 when he was appointed camp historian for Brigham Young’s second trip to southern Utah. The group had an ambitious mission: “visiting the southern settlements; exploring the country; ascertaining the situation of the Indians; making roads; building bridges; killing snakes; preaching the gospel; and doing and performing all other acts and things needed to be done, as they may be led by the Good Spirit.” [19]

The expedition lasted only a month, and Clayton kept a daily journal, though in a rather unusual place. Beginning on April 21, 1852, and concluding on May 16, 1852, it is found in the back of Edward Hunter’s account book, 1857–79. [20] One must turn the account book upside down to read the journal. It provides interesting descriptions of the early Mormon settlements they passed through, meetings with American Indians, and some brief exploring.

British mission journal. Clayton’s final journal covers his 1852–53 mission to England. He was part of a group of nearly one hundred missionaries called during a special conference on August 28 and 29, 1852, to go to the nations of the world. Their assignment was not only to preach the gospel but also, for the first time in church history, to preach publicly the doctrine of plural marriage. By that time Clayton was the husband of four living wives and the father of fifteen children, with two more on the way. His enthusiasm for the gospel, however, left no question in his mind—he would go wherever and whenever the living prophet sent him.

The mission turned out to be a bittersweet experience. He loved being back in England and reuniting with old friends. But he got into difficulty for two reasons: someone accused him of drunkenness, and someone else accused him of immorality. The drunkenness charge may have been true, for Clayton had an off-and-on problem with alcohol. Nevertheless, he convinced the mission president that it was not a problem then, and therefore he was not disciplined. But the charge of immorality was most likely connected to his enthusiastic advocacy of plural marriage, which clearly clashed with some English sensibilities. In any case, he became controversial enough that he was finally advised to return home after fewer than six months on his mission. His missionary diary, along with a poignant letter written to his friend Thomas Bullock, provides a telling story of one Latter-day Saint’s faith, determination, exhilaration, and disappointment. [21]

Temple records. Other than his personal journals, perhaps no records were more important to William Clayton than those he kept of the Nauvoo Temple. From the time he went to work for the Prophet until he left Nauvoo four years later, he was bound to the temple as much as to the church itself. He kept its records, wrote its history, and participated in its sacred ceremonies.

By the time Clayton received these records, the construction of the temple was well on its way. As the edifice continued to rise, Clayton kept track of donations, purchases, and all other financial transactions. His authorized salary was two dollars per day. At first he worked in the counting room of Joseph Smith’s red brick store, but because the work was so voluminous and he needed more room, the temple committee eventually erected a small brick office for him near the temple site.

Joseph Smith introduced the sacred temple endowment ceremony first to his private prayer circle, sometimes called the “Anointed Quorum” or the “Quorum of the Anointed.” Clayton became a member of this select group in January 1844. He must have been tempted to write about what he was learning in his diary, but, believing as he did that sacred things must be kept sacred, he simply noted his attendance at the prayer circle meetings and left out the details of the ceremony itself. Once in a while he did provide a few comments that reveal the special nature of those meetings, which continued after the death of Joseph Smith.

One such occasion came on Sunday, November 30, 1845, when a select group of men, all members of the Anointed Quorum, met in the temple for the dedication of the attic, where the temple endowment would soon be given to the general membership of the church. William Clayton kept the minutes, which he recorded in his personal journal. During the meeting the group donned their temple robes and rehearsed parts of the temple ordinances “to get them more perfect.” [22] Another such occasion came a week later, when several members of the Anointed Quorum again met in the temple, dressed in their ceremonial robes. It became a kind of testimony meeting, with prayer, the administering of the sacrament of the Lord’s supper, expressions of gratitude from several people, and an address by Brigham Young that Clayton recorded, at least in part. Among other things, the new church leader said

that a few of the quorum had met twice a week ever since Joseph and Hyrum were killed and during the last excitement, every day and in the hotest part of it twice a day to offer up the signs and pray to our heavenly father to deliver his people and this is the cord which has bound this people together. If this quorum and those who shall be admitted into it will be as dillegent in prayer as a few has been I promise you in the name of Israels God that we shall accomplish the will of God and go out in due time from the gentiles with power and plenty and no power shall stay us. [23]

Clayton’s journal is the only place where we find some of these details, for much was left out of the published History of the Church.

On December 10 the full endowment ceremony was conducted for the first time in the temple, and of course it fell to Clayton to keep the records. From that day until they began to flee Nauvoo nearly two months later, the Saints flocked to the temple to receive their endowments and other temple blessings, thus ending the exclusive nature of the Anointed Quorum.

Temple history. As he kept the records of the Nauvoo Temple, Clayton also began to compile the notes from which he would write his history of the temple. He was so sure that future generations would want to know of the unique efforts and faith-promoting stories that went into the construction of this sacred building that he reported some of them in his history. Early in 1844, for example, Hyrum Smith asked the women of the church to pledge one cent per week for glass and nails, promising them their first choice of seats in the temple when it was finished. [24] When Clayton wrote his temple history in 1845, he noted that many women paid a year in advance and that already two thousand dollars had been received.

He also told of other subjects that did not find their way into the published History of the Church, such as an unusual contribution from the women of the La Harpe and Macedonia branches. Convinced that a new crane was needed to speed construction, in July 1844 they offered to provide the means to build it. The committee accepted the offer, and by the end of August the crane was complete and in operation.

A version of Clayton’s temple history was first published in the Juvenile Instructor in 1886 under the title “An Interesting Journal.” The editors of the magazine had mistitled the work, however, for it was not a “journal” as such; it was a manuscript history. They also made some grammatical changes and shortened or paraphrased some of the sections. The Juvenile Instructor version was published again in 1991 in a book of Clayton documents. A literal transcription from Clayton’s original manuscript was published in full, for the first time, as an appendix in the second edition of this author’s biography of William Clayton. [25]

Book of the Law of the Lord. When Willard Richards turned over to Clayton all the records pertaining to the temple, the collection included the “Book of the Law of the Lord.” Clayton then became one of several scribes who contributed to this record. This large, leather-bound book primarily contains a list of tithing contributions for the building of the temple, and 370 of its pages are in Clayton’s handwriting. The book also contains some manuscript sources used in compiling Joseph Smith’s History of the Church, and Clayton wrote about sixty-one of these pages. The language was written mostly in the third person and was later changed to first person for the sake of the published history. The book also contains some direct dictation from Joseph, such as a letter to Emma that Clayton entered and then presumably copied and sent her. [26]

Among the more tender items Clayton recorded in the “Book of the Law of the Lord” were Joseph Smith’s reflections on the loyalty of his friends, dated August 16 and 23, 1842. These reflections eventually found their way into the History of the Church. They were precipitated by the arrest of the Prophet and Orrin Porter Rockwell on August 8 for their alleged role in the attempted murder of Lilburn W. Boggs, former governor of Missouri. The Nauvoo municipal court released the two on a writ of habeas corpus, whereupon the Adams County officers appealed to Illinois governor Thomas Carlin. When the officers left, Joseph went into hiding. The Prophet remained in hiding for several weeks, being visited only clandestinely by a few trusted friends, including William Clayton.

On August 11 Joseph sent word that he wanted to meet with his scribe as well as a few others. After dark that night, Clayton, Emma Smith, Hyrum Smith, William Law, Newel K. Whitney, George Miller, and Dimick Huntington took a skiff to an island in the Mississippi. They were soon joined from the Iowa side by Joseph Smith and Erastus Derby. The group decided that Joseph should be taken to another location up river and continue to hide out until the danger passed. It was a deeply emotional time. Five days later the Prophet began to dictate his feelings to his scribe; he continued that dictation on August 23. Together the two dictations formed a long, tender soliloquy that captured the love Joseph had for his friends as well as the meaning of genuine friendship. He said, in part:

My heart was overjoyed as I took the faithful band by the hand, that stood upon the shore, one by one. . . .

I do not think to mention the particulars of the history of that sacred night, which shall forever be remembered by me; but the names of the faithful are what I wish to record in this place. These I have met in prosperity, and they were my friends; and I now meet them in adversity, and they are still my warmer friends. These love the God that I serve; they love the truths that I promulgate; they love those virtuous, and those holy doctrines that I cherish in my bosom with the warmest feelings of my heart, and with that zeal which cannot be denied. I love friendship and truth; I love virtue and law; I love the God of Abraham, of Isaac, and of Jacob; and they are my brethren, and I shall live; and because I live they shall live also. [27]

The “Book of the Law of the Lord” also contains the original manuscripts of some of Joseph Smith’s revelations in Clayton’s handwriting. An example is section 127 of the Doctrine and Covenants, which is a letter about baptism for the dead.

Because Clayton believed his responsibility to keep church records was sacred, he must have felt devastated after an experience around the time of Joseph Smith’s martyrdom. At 1 a.m. on Sunday, June 23, 1844, he was roused from his bed with the message that Joseph Smith wanted to see him. Joseph and his brother Hyrum, aware of plots to kill them, had determined to flee across the Mississippi. When Clayton met him at the river, Joseph whispered to him some alarming instructions about the records of the kingdom of God (that is, the Council of Fifty). He was either to give them to a faithful man who would take them to safety, or he was to burn or bury them. The devout scribe could hardly bear either to part with or destroy the sacred records he had worked so hard to compile. He hurried home, gathered up not only the private records but also all the public records he possessed, and buried them. Ten days later, after Joseph Smith was dead, Clayton dug up the records, only to find that in his haste he had not adequately waterproofed them, and moisture had seeped in and damaged them. One can only imagine his horror.

Other Nauvoo records. As indicated earlier, William Clayton also kept tithing records—not just those having to do with donations to the temple but other such records as well. In addition, he made numerous entries in the record book of the Nauvoo Masonic Lodge. [28]

Minutes of the Council of Fifty. The Council of Fifty was another highly confidential body established by Joseph Smith and consisting of men he felt he could trust, for their loyalty had already been tested. It was a quasi-secular body set up to plan and work for the eventual establishment of the political kingdom of God on earth. Among other things, the council planned and directed Joseph Smith’s run for the presidency of the United States, directed Nauvoo’s industrial development after his death, and exercised important political influence in the Territory of Utah. It was officially organized on March 11, 1844, and the next day William Clayton was appointed “Clerk of the Kingdom,” a title he no doubt relished.

The meetings of the Council of Fifty were confidential, so Clayton made only brief notations in his personal journal, but he apparently kept careful notes and spent long hours recording them in the official minute books. [29] Anticipating a glorious future for the kingdom, he once wrote that in these meetings “the principles of eternal truths rolled forth to the hearers without reserve and the hearts of the servants of God [were] made to rejoice exceedingly.” [30] On April 11 they even voted to make Joseph Smith their “Prophet, Priest, and King,” confirming him with “loud Hosannas.” [31] Although the Council of Fifty was ostensibly a secular body, it had great spiritual significance for its clerk.

Heber C. Kimball’s journals. It is not surprising that others occasionally wanted to make use of Clayton’s talents as a record keeper and scribe. Before Heber C. Kimball left England in 1840, he asked Clayton to write his history, which Clayton was happy to do. He worked on it almost until the day he emigrated. Kimball had good reason to assign this task to Clayton. He was an extremely busy church leader, and Clayton was not only a good friend but also a better writer and penman. A comparison of the handwriting, spelling, and general grammatical skills of the two clearly shows that Clayton had the advantage.

The history Clayton prepared for Kimball was probably the document that later became “History of the British Mission,” which was signed by Kimball, Orson Hyde, and Willard Richards and published in Joseph Smith’s History of the Church under the date of March 23, 1841. It covered the history of missionary work in England from the time Kimball first arrived in 1837 to April 6, 1840. [32]

This was not the end of Clayton’s ghost-writing for Kimball. As the Saints were preparing to leave Nauvoo and at the same time administer the sacred temple ordinances to thousands of people, Kimball asked, or perhaps assigned, Clayton to keep a temple journal for him. By this time Clayton was heavily overworked, but he took on the task anyway. The journal, which Clayton wrote in the first person as if he were Kimball, gives interesting details regarding the hectic activities in the temple between December 10, 1845, and January 7, 1846. [33]

Kimball called on Clayton’s talents again as the vanguard company left Winter Quarters in 1847 to go west and scout out the location for the new settlement of the Saints. But Clayton was occupied with many other tasks, such as keeping his own journal; working as assistant to Thomas Bullock, the camp scribe; and keeping track of the distances traveled each day. Kimball, however, asked him again. By May 21 Clayton was well behind in the task, so Kimball suggested that he leave several blank pages, start from the present, and then catch up later. Clayton wrote in his own journal on that day: “He furnished me a candle and I wrote the journal of this day’s travel by candle light in his journal, leaving fifty-six pages blank.” [34]

Emigrants’ Guide. While crossing the plains with the vanguard pioneer company, Clayton kept track of the mileage traveled each day. At first he tried to estimate the distance, but soon, recognizing the inaccuracy of such a method, he suggested to several people that an odometer be attached to a wagon wheel. Frustrated when nothing happened, he finally resorted to measuring the circumference of a wagon wheel and then counting the revolutions as he walked beside the wagon all day. The odometer was eventually constructed, and he got his more accurate count, both going to the Salt Lake Valley and returning to Winter Quarters. Back at Winter Quarters he constructed a table of distances, showing the mileage between various suggested stopping points along the way and indicating that it was exactly 1,032 miles between the two points.

The value of this information for Mormons as well as other overland migrants was immediately apparent, and early in 1848 Clayton was able to get his work published. Titled The Latter-day Saints’ Emigrants’ Guide, the volume provided details for every mile along the way. Each major stream, hill, swamp, or other landmark was listed, along with brief descriptions of what the traveler might find there. The guide helped provide a small income for Clayton, as it was sold to willing Saints as they set out on their unfamiliar journey across the plains. It also served thousands of other pioneers bound for Oregon or California. It was copied, at least in part, by compilers of other emigrant guides and for that reason has been recognized for contributing significantly to the saga of the West.

Letter books. Clayton kept other kinds of records that were not church records but, to some degree, provide insights, at least into the lives of church members. His numerous letter books, now housed in the Bancroft Library in Berkeley, California, are filled with day-to-day business transactions in connection with his work as territorial auditor and recorder of marks and brands. For the most part they are repetitious and dull, but tucked amid the tedium are many personal letters that cast light on topics of concern to both Clayton and the church during the first three decades of the Utah experience.

In addition to all this, Clayton was frequently appointed to take the minutes of conferences and other church meetings.

Loyalty to the Prophet

William Clayton believed his record keeping was a sacred calling. He also felt called, partly through his writing, to build all the support he could for Joseph Smith and to preserve the most positive image of the Prophet as possible. In the process, he wrote of many events that eventually found their way into the history of the church. An account he wrote on September 3, 1842, of an ill-fated attempt by a Missouri sheriff to arrest the Prophet illustrates at least one aspect of William Clayton’s fierce devotion to Joseph Smith. It appears in History of the Church. [35]

The Missouri sheriff and two other men arrived in Nauvoo early in the afternoon of that day. They had planned to arrive during the night, but after they left Quincy they lost their way. Fatigued and “sore from riding,” they hitched their horses where they could not be seen and crept quietly to Joseph Smith’s home. When they entered they found only John Boynton, for Joseph was dining with his family in another room. They questioned Boynton as to the Prophet’s whereabouts, but Boynton evaded a direct answer by simply saying that he had seen Joseph early that morning. Meanwhile, Joseph slipped out the back door, hurried through the tall corn in his garden, and soon hid himself in the home of Newel K. Whitney. Emma confronted the officers and permitted them to search the premises, even though they admitted they had no search warrant. Perhaps such a search would delay them, giving her husband more time to make his escape. Unable to find their quarry, the Missourians left. Later that night the Prophet moved to the home of Edward Hunter, where, Clayton wrote, “He [could] be kept safe from the hands of his enemies.” [36]

The equally interesting part of this account is Clayton’s vivid editorializing, for it demonstrates not only his loyalty to the Prophet but also his ire against those who would threaten him in any way. “This is another testimony and evidence of the mean, corrupt, illegal proceedings of our enemies,” he fumed, “not withstanding the Constitution of the United States” that included guarantees against unreasonable search and seizure. “Yet these men audaciously, impudently and altogether illegally searched the house of President Joseph Smith even without any warrant or authority whatever. . . . They appeared to be well armed, and no doubt intended to take him either dead or alive; which we afterwards heard they had said they would do; but the Almighty again delivered His servant from the bloodthirsty grasp.” [37] Clayton never moderated his words when praising the Prophet and denouncing his enemies.

Conclusion

Without historians who write the books and articles we read, there would be no Latter-day Saint history. Without the documents of the past, there would be little for the church historian to write about. Without the scribes, secretaries, diarists, and others who created the documents, the stuff from which church history is created would not exist.

At the same time, the nature of history usually reflects the nature and predilections of the historian, as does the nature of the documents on which the historian relies. William Clayton’s predilections included his unfailing testimony of the gospel and his loyalty to Joseph Smith. To the degree that his records affect anything in the written histories of the church, those predilections are perpetuated. Most Latter-day Saints will never know his name, but through his contributions they can better understand the man he revered most deeply, the Prophet Joseph Smith. We owe much of our knowledge of early Latter-day Saint history to the work of obscure figures such as William Clayton.

Notes

[1] History of the Church, ed. B. H. Roberts (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1978), 6:409. For a list of all these clerks and their major contributions, see Dean C. Jessee, “The Writing of Joseph Smith’s History,” BYU Studies 11, no. 4 (Summer 1971): 439–73.

[2] Tithing and Donation Record, 1844–46, 220–22, Church History Library, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City; William Clayton, Nauvoo Journals, January 29, 1845, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City.

[3] Much of the information in this article was taken from James B. Allen, No Toil nor Labor Fear: The Story of William Clayton (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 2002).

[4] See James B. Allen and Thomas G. Alexander, eds., Manchester Mormons: The Journal of William Clayton, 1840 to 1842 (Santa Barbara: Peregrine Smith, 1974).

[5] William Clayton, “History of the Nauvoo Temple,” ca. 1845, reproduced as Appendix 2 in Allen, No Toil nor Labor Fear, 423. This work is a revised edition, with two added appendices, of Trials of Discipleship: The Story of William Clayton, a Mormon (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1987).

[6] Reproduced in Allen, No Toil nor Labor Fear, 73–74; original in Pioneer Memorial Museum, Salt Lake City.

[7] Minutes, November 10, 1873, School of the Prophets, Salt Lake City Records, Church History Library.

[8] Clayton to the Saints in Manchester, December 10, 1840, as copied by William Hardman, January 26, 184[1], Church History Library.

[9] Clayton to William Hardman, March 30, 1842, as quoted in Millennial Star, August 1842, 75–76; emphasis in original.

[10] The original journal is located at Brigham Young University but has been published as Allen and Alexander, Manchester Mormons.

[11] It is instructive to compare what Clayton originally wrote with what finally appeared in the published History. Such comparisons are included, in parallel columns, in an appendix to my biography of Clayton, No Toil nor Labor Fear, 385–413.

[12] Clayton, Nauvoo Journal, May 1, 1843.

[13] History of the Church, 5:372.

[14] Stanley B. Kimball, “Kinderhook Plates Brought to Joseph Smith Appear to Be a Nineteenth-Century Hoax,” Ensign, August 1981, 66–74; Ben McGuire, in FAIR: Defending Mormonism, http://

[15] History of the Church, 5:393–94; Clayton, Nauvoo Journal, May 18, 1843.

[16] The Church History Library has both the published Clayton pioneer journal and the original unpublished pioneer journal. The latter includes entries from November and December 1847 that describe Clayton’s activities after he returned to Winter Quarters.

[17] William Clayton’s Journal (Salt Lake City: Clayton Family Association/

[18] William Clayton’s Journal; W. Clayton, The Latter-day Saints’ Emigrants’ Guide: Being a Table of Distances, Showing All the Springs, Creeks, Rivers, Hills, Mountains, Camping Places, and All Other Notable Places, from Council Bluffs, to the Valley of the Great Salt Lake (St. Louis: Mo. Republican Steam Power Press/

[19] Editorial, Deseret News, May 1, 1852.

[20] Located in the Edward Hunter Collection, 1816–84, Church History Library.

[21] William Clayton to Thomas Bullock, February 5, 1853, Thomas Bullock Correspondence, Church History Library; William Clayton, Diary, August 1852–March 1853, Church History Library.

[22] Clayton, Nauvoo Journal, November 30, 1845; History of the Church, 7:534–35. The latter entry is based almost verbatim on the Clayton journal except that a few items from the journal are omitted, such as the fact that the participants were dressed in their temple clothing and that they rehearsed the ceremonies.

[23] Clayton, Nauvoo Journal, December 7, 1845.

[24] History of the Church, 6:298–99; Allen, No Toil nor Labor Fear, 426–27.

[25] Allen, No Toil nor Labor Fear, 415–42; “An Interesting Journal,” Juvenile Instructor 21 (January 15–May 15, June 15–July 1, August 1–October 15, 1886): 23, 47, 60–61, 79, 106–7, 122–23, 141–42, 157–58, 186–87, 202–3, 230–31, 246, 258–59, 281, 290–91, 310–11; George D. Smith, ed., An Intimate Chronicle: The Journals of William Clayton (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1991), 525–53. The original manuscript of the temple history is housed in the Church History Library.

[26] Dean C. Jessee, comp. and ed., The Personal Writings of Joseph Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1984), 525–37, 690–91. Additional information on the “Book of Law of the Lord” has also been provided personally by Dean C. Jessee as well as by Alex Smith’s “Joseph Smith’s Nauvoo Journals: Understanding the Documents,” delivered at the annual conference of the Mormon History Association, Casper, Wyoming, May 2006.

[27] The entire dictation is recorded in History of the Church, 5:107–9, 124–28; Jessee, Personal Writings of Joseph Smith, 530–37. History of the Church indicates that Joseph Smith began this dictation on August 16 and continued it on August 22, but Dean Jessee says it was continued on August 23.

[28] Jessee, “Writing of Joseph Smith’s History,” 456.

[29] For example, his personal journal entry for Sunday, August 18, 1844, indicates that on that day he was “at the office copying the record of the Kingdom.”

[30] Clayton, Nauvoo Journal, “Reflections,” recorded January 1, 1845.

[31] Clayton, Nauvoo Journal, April 11, 1844, records the vote: “Prest J. was voted our P. P. & K. with loud Hosannas.” This important entry says much about the goals of the Council of Fifty, but it does not say that Joseph was actually ordained a king. The evidence for such an ordination is still debatable.

[32] History of the Church, 4:313–21.

[33] This journal has been published in Smith, An Intimate Chronicle, 199–258. Smith calls this a Clayton journal, for it is in Clayton’s handwriting. But it was never intended to be thought of that way and, at least in my opinion, should be included in a compilation of Kimball journals rather than Clayton journals.

[34] William Clayton’s Journal, 169.

[35] The History of the Church does not specifically state that the account quoted here is by William Clayton, but it does indicate that it was written by “the Prophet’s secretary.” The evidence that leads me to conclude Clayton is the secretary in question is that (1) the first part of the account reflects specifically the idea that Clayton received in the Hollister letter (see D. S. Hollister to William Clayton, September 1, 1842, Church History Library); (2) at this point Clayton was Joseph Smith’s scribe; and (3) the language of the account, especially where it denounces the Missourians, is much like Clayton’s language in other places. The same heated tone is evident in many of his statements about the Prophet’s detractors.

[36] History of the Church, 5:145–46; George Miller to William Clayton, September 4, 1842, and D. S. Hollister to William Clayton, September 1, 1842, Church History Library.

[37] History of the Church, 5:145.