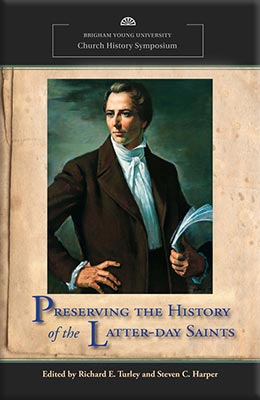

Ignored and Unknown Clues of Early Mormon Record Keeping

Robin Scott Jensen

Robin Scott Jensen, “Ignored and Unknown Clues of Early Mormon Record Keeping,” in Preserving the History of the Latter-day Saints, ed. Richard E. Turley Jr. and Steven C. Harper (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2010), 135–64.

Robin Scott Jensen was a documentary editor with the Joseph Smith Papers Project when this article was published.

For the past several years, the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) has aired a program titled History Detectives that follows historians who research viewers’ questions. These “detectives” attempt to solve historical mysteries based on intriguing documents, passed-down artifacts, or even family lore. A critical backdrop to the early nineteenth-century culture of record keeping is found in comparable contemporary record keeping and in the archival theory of similar record-keeping practices. (As a trained historian, I envy how everything seems to fall into place.)

The show compresses the entire research period into a ten- to fifteen-minute segment, and the culmination of each “case” comes in the final exciting explanation. Yet the show’s appeal lies not only in finding out the ultimate answer to each question but in seeing the process that led to that answer. What could be more exciting than watching historians scouring boxes of documents or going through rolls of microfilmed old newspapers?

In a similar vein, think of this paper as a Mormon History Detectives case file. It will analyze three puzzles found in early Mormon record-keeping.

Understanding Mormon Record-Keeping Practices

First, a short primer on Mormon record-keeping practices and an introduction to ledger volumes will set the background. Early Mormon historians benefited greatly from the sources made available by the record-keeping practices of clerks, scribes, and historians. Before the history-writing efforts in Missouri, which led to the critically important “Manuscript History of the Church,” scribes recorded minutes into minute books. Before Oliver Cowdery began what is now known as the 1834–36 history, scribes copied loose letters into a blank book, thereby preserving the letters’ contents. Joseph Smith and his scribes and historians could eventually write a history because they had the material from which to draw. Surviving histories either would not exist or would be dramatically different if individuals had not kept administrative, personal, and communal records.

Today, scholars of Mormonism should feel compelled to study early Latter-day Saint record-keeping in depth, building upon the critical work of Dean C. Jessee and others who have analyzed the work of early Mormon scribes. [1] An understanding of even the minute details of record-keeping practices can help historians write better history as they recognize why the sources were created and what information can be extracted from these sources.

Such an understanding begins with the records themselves, as they are the most helpful sources in uncovering information about their creation, use, and storage. Supplementary information may come from record keepers’ accounts, though at times this information is misleading. A critical backdrop to record-keeping culture is found in comparable contemporary record-keeping and in the current archival theory of similar record-keeping practices.

The Introduction of Ledger Volumes

An important development in Mormon record-keeping occurred when early Mormon scribes began keeping different types of records in bound, blank ledger volumes. The three examples highlighted below come from elements found on or just inside covers of these ledger volumes. Before we consider each example, a short history of the ledger volume in early Mormon record-keeping is in order.

Joseph Smith began his own record-keeping practices by writing down scripture. The translation of the Book of Mormon, the recording of his revelations, and his revision of the Bible eventually resulted in hundreds of pages of text. The Prophet did not initially write any of this text in a ledger volume. The best available extant sources indicate that the introduction of ledger volumes into Mormon record-keeping began in the spring of 1831 with the creation of Revelation Book 1, titled “A Book of Commandments and Revelations.” [2] This was followed in 1832 by four more volumes in rapid succession: Revelation Book 2, titled “Book of Revelations” and known more contemporarily as the “Kirtland Revelation Book”; the 1832 history and Letterbook 1, which share the same volume; Minute Book 1, also known as the Kirtland High Council Minute Book; and Joseph Smith’s first journal—the only volume not strictly a twelve-by-eight-inch ledger volume. [3]

Many scholars might see this change in record-keeping material as inconsequential at best. But it was actually a dramatic shift in medium and represented a profound change in how record-keeping was viewed.

Recent archival studies have explored the meaning behind the use of record-keeping materials. [4] The act of purchasing, maintaining, and preserving a ledger book as opposed to using loose-leaf paper indicates a desire to keep more permanent records. Current historians consequently can access a tremendous array of primary sources. The manner in which each ledger volume was used also provides valuable information. For instance, unless a volume was damaged in some way, one can easily see if pages are missing. In addition, scholars can estimate the amount of usage by surveying the wear and tear of a volume.

A thorough analysis of records—including an examination of how they were kept, what they were kept in, and why they were kept—provides information and raises questions that can lead to a better understanding of a record’s historical context. This paper does not analyze the provenance historiography—or evolving interpretations surrounding the provenance—of early Mormon manuscripts, nor does it anticipate future scholarship historians might explore. Instead, it reveals how a greater understanding of the records created by early Latter-day Saints can provide a window into Joseph Smith’s thinking as well as that of other early church leaders.

The examples that follow will help uncover information about the creation, usage, and repurposing of three record-keeping “cases.” Like the previously mentioned PBS show, this paper not only gives some intriguing answers to the puzzles presented here but also shows the strategy and importance of the analytical journey itself. Therefore, conclusions are purposefully drawn out, arguments are tentative, and evidence is presented at a fairly slow pace. These examples are not meant to be exhaustive, nor are the solutions typical of document analysis. Rather, they underscore the necessity of carefully studying the sources. Not all documents have hidden meanings under the ink, but all share a story to those willing to search. An improved understanding of the documents helps sharpen the focus on the facts, which leads to a more accurate reconstruction of history.

Case #1: Possible Bookkeeping Notations

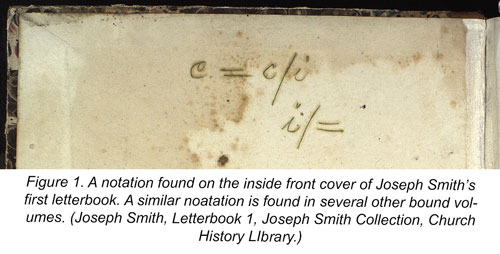

In the inside front cover of many ledger volumes used by early Mormon clerks, an opaque notation appears in pencil—apparently unrelated to the content of the volume (see figure 1). The following are examples of these notations (“|” indicates a new line):

- "c c/

i | pep" (could be transcribed "pe/=") (from Revelation Book 2) - "c = c/

i | i\=" (from JS Letterbook 1) - "c c/

i | pep" (from Minute Book 1) - "i/

n[?] | 12/=" (from the Quorum of the Twelve Minute Book) - "c/

i" (from the Far West and Nauvoo Elders’ Certificates book) - "c u/

d | i/=" (from the Egyptian Alphabet volume) - "c o/

i | u/ i" (from the Elders’ Quorum Minute Book) [5]

As can be seen in the examples, commonalities throughout the notations are the prevalent use of c, i, and the slash mark (/ or \). The differing notations are related both in their makeup and style. Upon reflection, the notations appear to be a set of archival markings due to their fairly prominent placement, their temporary nature (written in graphite), and their obscurity—as if they were linked to an unknown, database-like cataloging system. Exactly what the notations’ letters and symbols meant is currently lost to this generation.

The theory that archivists made these notations at a later date loses merit when the single Community of Christ volume, the Elders’ Quorum Minute Book, is taken into consideration. As far as can be determined, this volume was at no time in the custody of the LDS Church in Utah or even in Nauvoo. [6] Its notations, therefore, may have appeared soon after the volumes were begun (some of these records were updated into the 1840s and beyond), or, due to their prominent position, the notations may have been added to the volumes before the volumes were even inscribed by the original user.

Comparing the notations and attempting to decode their meaning forces a deeper analysis. Most of these volumes appear to have been begun in the early 1830s. [7] The relatively narrow time frame for the creation of these volumes may indicate that the books were purchased or otherwise acquired during a similarly narrow window of time. This conclusion seems more plausible when the creation of the notations is taken into consideration: a short period of time would likely result in similar, across-volume notations. If the volumes were purchased over a five-year period, for instance, it is less likely that a similar notation was created either before the volumes were inscribed or early in the process.

The terse notations might compare loosely to early forms of bookkeeping or accounting terms, but at the same time, no obvious meaning can be deduced from any guidebooks of the period. [8] If the notations are indeed somehow related to accounting terms, they may have been a regional or personal adaptation of those terms—perhaps a single storekeeper’s notations now lost to history.

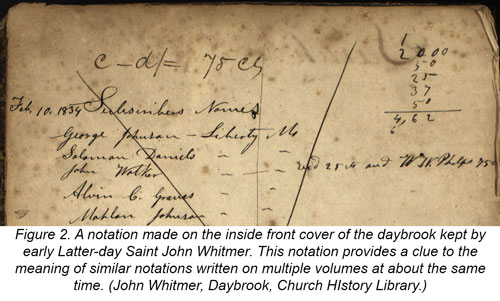

A significant clue to this mystery—which seems to hint at a storekeeper’s notations—comes from another volume with a similar notation: the John Whitmer Daybook, begun around the same time as most of the other volumes. [9] The notation near the beginning of the volume reads “c-d/= 75 cs” (see figure 2). If the “cs” (the reading may be “cts” with the t uncrossed) is a shortened form of cents, this notation seems to buttress the theory that these unknown markings may have been an effort to mark the book before purchase—with the price, for instance. This does not preclude the possibility that it might also be a storekeeper’s notation indicating the type, format, or quality of the volume.

Unless a new source or notation is discovered, or unless new insight on nineteenth century record-keeping practices is gained, historians may never know the exact meaning of the notations in the volumes. One can assume, however, that these volumes were purchased or created during a short window of time—indicating that these volumes are a grouping in the early Mormon record-keeping story.

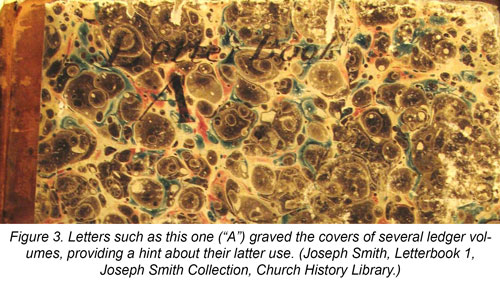

Case #2: Alphabetic Arrangement

The second “case” is an alphabetic puzzle found on the covers of seven volumes throughout the collection of the Church History Library. Each cover is adorned with a letter (or letters) of the alphabet:

- A (Letterbook 1; begun in 1832)

- A | B (Revelation Book 2; begun in 1832)

- A | C (Minute Book 1; begun in 1832)

- D (Joseph Smith’s 1835–36 Journal)

- F (Joseph Smith’s 1832–34 Journal)

- G (Joseph Smith’s March–September 1838 Journal)

- H (Missouri Teachers Quorum Minute Book; begun in 1834) [10]

Note the absence of the letter E and the nonchronological arrangement of the volumes. Three books of documents seem to be grouped first—letters, revelations, and minutes. Three journals then seem to be grouped together, but as volume E—if it ever existed—is missing, this may or may not be a grouping of journals.

The alphabetic collection is not a comprehensive grouping of volumes containing historical documents or all of Joseph Smith’s journals. Revelation Book 1 contains no letter on its cover, nor does Letterbook 2. [11] The Missouri Teachers’ Quorum Minute Book appears to be alone among quorum records with a letter assigned to its cover. The covers enclosing the Elders’ Quorum Minute Book and the Quorum of the Twelve Minute Book are devoid of any letters. [12] Two volumes, Revelation Book 2 and Minute Book 1, have two letters on the front cover, both bearing an A and then bearing a B and a C respectively. On some volumes, the letter is the only thing gracing the cover. For most, however, the letter or letters seem to be part of a title or positioned around an already-existing title (see figure 3). These notations do not appear to predate the use of the volumes as Mormon records.

That these letters were used as a classification system seems clear. The style of several letters is quite similar, and the grouping of the journals seems to be somewhat methodical—although the absence of the letter E might indicate a nonjournal volume amid that genre (which is the case, as we will see shortly).

Due to the similar style of some of the letters, it seems likely that the letters were written at the same time, meaning that the alphabetical system was started after the latest volume was created in 1838—well after many of these volumes were complete. Had the volumes been lettered shortly after their creation or while they were being used (presumably indicated by an ordered lettering system—in other words, earliest records with earlier letters of the alphabet), the ordering would have suggested either an anticipation of a system of recall or filing, or a system that was already in place for office needs. The fact that no system was in place is not surprising considering the limited nature of early 1830s record-keeping and the nonsystematic way of handling records during the nineteenth century. This attempt to identify volumes largely out of use by 1838 with an alphabetic lettering system indicates a method of storage or secondary use.

Record managers today will understand this record life cycle: the records were no longer actively used by church clerks and instead became archival records, or records preserved for a use other than their primary purpose. A system of storage or secondary use suggests that the volumes were repurposed and were assembled, identified, and stored according to this later need. Such a need arose out of the history-writing effort in Nauvoo.

In 1838 Joseph Smith continued his multiyear effort of creating a history by writing an autobiography that would fill six large manuscript volumes when it was completed well after his death. [13] Initially the history consisted of dictation from memory, interspersed with the occasional revelation as copied from the 1835 Doctrine and Covenants. Beginning in 1843, scribes Willard Richards and William W. Phelps dramatically changed the format of the history—namely, by copying into the history many more documents from earlier records, thereby transforming a memoir into a documentary-history effort. [14] The inevitable need to compile and classify such earlier documents for ease of reference, use, and cross-reference would have arisen at this time.

memory, interspersed with the occasional revelation as copied from the 1835 Doctrine and Covenants. Beginning in 1843, scribes Willard Richards and William W. Phelps dramatically changed the format of the history—namely, by copying into the history many more documents from earlier records, thereby transforming a memoir into a documentary-history effort. [14] The inevitable need to compile and classify such earlier documents for ease of reference, use, and cross-reference would have arisen at this time.

This reconstruction is more than just conjecture. Fortunately for the droves of people clamoring for a better understanding of Mormon record-keeping, a document exists that sheds light on this alphabetic lettering system. Revelation Book 2 served its primary purpose as a register of copies of revelations dictated by Joseph Smith. Half of the volume was left blank, however, and Richards and Phelps used a few blank pages at the end of the volume to record their notes on the history-writing effort in Nauvoo. They provided this explanation for the purpose of the notes: “Material facts left out of the history of the church are noted here that they may be brought in. in their place.” [15]

As Richards or Phelps discovered documents not incorporated into the history, they would record that document in their notes, with the volume and page number if the document was found in a manuscript volume. The abbreviations they used when referring to the cited manuscript volumes took the form of an alphabetical system of assignment. What is more, the document description allows one to independently determine the letters they assigned to each volume; it confirms the letters found on the covers. In addition, the notes cite the missing E volume, which, based upon a comparison of the document cited in the notes, turns out to be Minute Book 2. Minute Book 1, with its dual letters of A and C, is referenced in the historical notes Phelps and Richards compiled as C. It is possible the A was added at a later time when the understanding of C was lost, or perhaps the A was added first and revised to C. [16]

Minute Book 2 as volume E reinforces the concept that this system of letters was put in place and inscribed on the volumes after 1838. Minute Book 2, also known as the Far West Record, was not created until 1838, when Ebenezer Robinson copied earlier records of minutes from John Whitmer. [17] Assigning E to a volume created in 1838 before F, which was created in 1832, again indicates the nonchronological nature of the classification system. No obvious reason exists why the scribes did not inscribe a letter on the cover of Minute Book 2. The differences between all the volumes in this group are many, but Minute Book 2 is the only volume bound in full leather. However, other Nauvoo-era volumes bound in full leather have writing on the cover, providing proof enough that scribes were willing to inscribe upon this type of volume.

An important insight into this alphabetical classification system is the manner in which early church historians compiled the history. It appears that Nauvoo-era historians took a survey of the documents in the church’s possession and adopted a secondary use for the volumes as historical records. The notes the Nauvoo historians created indicate which volumes Richards and Phelps were scouring in 1843 to supplement the history already written. Their view of an imperfect history (“Material facts left out of the history of the church are noted here”) should warn current historians who might assume the early portions of the history are without error. (For instance, the fact that the historians did not have access to early conference minutes of the church explains why some dates and other details are wrong in the manuscript history.) [18] Current historians should also be aware of the volumes double-checked for inclusion in the history. Because Revelation Book 1—a source that provides many early revelation dates—is not found in the list of volumes on the notes, nor does it appear to be used in the early or later history portion, adjustments should be made to the dates of early revelations found in the manuscript history that contradict the dates found in Revelation Book 1, based on careful research and comparison of other primary sources. The manuscript history is of great importance, but this case underscores how historians can better identify potential historical fallacies by identifying the sources that the compilers consulted.

Case #3: Topical Classification of Old Testament Terms

Finally, this paper will discuss an example of a Mormon-scripture-related project which, had it been completed, likely would have out-scaled any other theological project during Joseph Smith’s lifetime. This project not only would have offered tremendous insight into the theological cosmology of church leadership but would have shaped early Latter-day Saint hermeneutics on multiple facets of the religion. As it stands, it provides limited but important insight into the development of Mormon theology. The project is virtually unknown by anyone today, however, and only scant remnants of it exist from three ledger volumes not traditionally known as being part of the project. One reason for the project’s obscurity is the obscurity of the clues left behind. Historians who concern themselves only with the content rather than the context of the records reinforce this challenge. One must remember to view these documents not just as they are today but as they were used from the first day they were created.

tremendous insight into the theological cosmology of church leadership but would have shaped early Latter-day Saint hermeneutics on multiple facets of the religion. As it stands, it provides limited but important insight into the development of Mormon theology. The project is virtually unknown by anyone today, however, and only scant remnants of it exist from three ledger volumes not traditionally known as being part of the project. One reason for the project’s obscurity is the obscurity of the clues left behind. Historians who concern themselves only with the content rather than the context of the records reinforce this challenge. One must remember to view these documents not just as they are today but as they were used from the first day they were created.

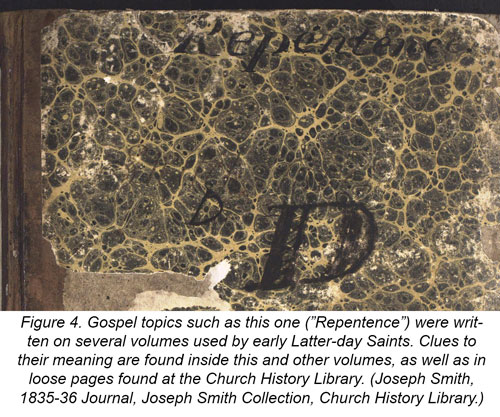

Three ledger volumes display gospel-related words on the covers (the front and back of two volumes and the front cover of one). The words are featured prominently at the top of each cover, giving the appearance of titles. The three volumes, with their gospel-related topics, are currently known as the following manuscript books (see figure 4):

- Joseph Smith’s 1835–36 Journal (“Repentence” and “Sabbath Day”)

- A ledger volume of the Egyptian Alphabet (“Faith”)

- Elders’ Quorum Minute Book (“Second Comeing of Christ” and “Gift of the Holy Ghost”) [19]

If document specialists had been left with only the words on the covers, little could be determined about the meaning behind these topics. Upon opening the books, however, it becomes apparent that the first page of each volume is related to the words upon the cover. Two of the three volumes include scriptural passages relating to the word on the front of the volume (the third volume—the Egyptian Alphabet volume—is missing these initial pages). Notations such as “Scriptures relating to the Gift of the Holy Ghost” directly tie the scriptural citations to the gospel topic.

For instance, the front cover of Joseph Smith’s 1835 journal bears the term “Repentence” and the back cover uses the term “Sabbath Day.” Opening the front cover of the volume, one finds seven lines of “Scriptures relating to Repentince” (see figure 5). The back cover opens to a page containing “Scriptures relating to the Sabbath day,” which includes six lines of scriptural references.

All three volumes carry numbers in addition to the gospel-related terms. The minute book has the number 3, the journal displays the number 9, and the Egyptian Alphabet was numbered 10. The similar nature of the ink characteristics and positioning of the numbers on the volumes suggest that the numbering is related to the gospel terms. If the volumes were numbered sequentially, at least ten volumes would have been created as part of this scripture-related project. The 1835 journal (repentance and Sabbath day) might indicate that the volumes were arranged alphabetically according to topic. However, the Elders’ Quorum Minute Book has “Second Coming of Christ” and “Gift of the Holy Ghost” on its covers, not in any obvious order.

Besides the three ledger volumes that bear scriptural terms, three looseleaf pages in the Joseph Smith Collection and one grouping of thirty-six pages that later made up the 1839 draft history—all at the Church History Library—include similar scriptural references. These pages cite scriptures relating to four different terms: “Covenants,” “Baptism,” “Priesthood after the order of Aaron,” and the “order of the High Priesthood.” The three sheets appear to have been cut or torn from a ledger volume, but they seem to have come from makes of paper that are different from each other as well as from the volumes in the set. Thus, evidence exists that two to three other ledger volumes might have existed in this work. The thirty-six-page grouping, however, indicates that material other than blank books was used. The extant manuscripts provide a total of nine topics, with scriptural citations likely having been created for all nine topics. (As mentioned, the Egyptian Alphabet volume is missing its initial pages, but citations likely existed.)

What are the scriptures cited? Many of the citations come from “Genesis,” but, as we shall see, this is not a simple collection of Old Testament citations. Several unusual characteristics give us clues. As opposed to citing the scriptures by chapter and verse—standard practice then as now—the references in these volumes are to section (normally with roman numerals) and paragraph number. Additionally, and perhaps most significantly, the scriptural references patterned after a particular gospel topic do not match the scripture cited in the King James Version of the book of Genesis. In essence, a person attempting to use these gospel topical guides would not find any scriptures to which the index purports to direct. Something else is going on. Even a novice in Mormon studies would recognize why the Latter-day Saint biblical citations do not match the King James Version of the Bible—the Mormons are citing the Joseph Smith Bible revision.

A single sentence on a one-page document provides the critical clue in determining the purpose of these Biblical topical indexes: “This day commenced classifying the different Subjects of the Scriptures and revewing the same,” signed by “F. G. Williams, Scribe,” and dated “Kirtland the 17th July 1833.” [20]

The summer of 1833 was an important time in the development of Mormon scripture. On July 2, 1833, two weeks before the date of the statement above, Joseph Smith and Frederick G. Williams finished the revision of the Bible. The revision was the Prophet’s effort to restore the many important truths in the Bible that he believed had been lost through mistranslations. [21] An attempt to index, arrange, or “classify” the newly revised Bible according to gospel topics would have been a natural outgrowth of that completed project.

Because many of the scriptural citations make reference to the book of Genesis, one would assume that the revision of the Bible manuscript dictated by Joseph Smith would provide the meaning of the citations. However, a comparison of the scriptural citations with the extant manuscripts of the Old Testament revision Williams would have had in his possession reveals a few problems.

Part of the difficulty comes in not knowing the manuscript or chapter/

This poses a problem with finding the scriptures intended for citation. For instance, when looking at scriptures related to the topic of the Sabbath day, the first reference (“Section 3 Paragraph 1”) matches up with the third series of inserted paragraph or verse numbers in the Old Testament manuscript 2 (there is no numerical heading for this chapter/

The discrepancies between Williams’s section numbers in the scriptural citations to any extant manuscript might be explained by introducing a nonextant manuscript into the scenario. As scribe for this classification system, Frederick G. Williams may have compiled the ledger volumes as he was creating a new, second copy of the Old Testament manuscript—perhaps incorporating all redactions in preparation to publish it. He also may have indicated the section numbers on a separate manuscript and used the existing paragraph numbers on the extant manuscript. It is possible to determine for all the citations the likely paragraph and chapter numbers for the current Bible revision, allowing for insight into the theological implications of the newly finished Bible revision (see Appendix).

Incredibly, as many as ten volumes full of scriptural citations from Joseph Smith’s Bible revision were attempted as a major scribal project as early as 1833. Such an ambitious work was never completed, but this particular failed ambition was not an isolated incident in Mormon record-keeping; never-finished projects were common. For example, Oliver Cowdery never completed the history he began in late 1834. In Joseph Smith’s first diary, many more days went unrecorded than recorded.

With two topics per ledger volume, a total of about twenty topics may have been used, and potentially more volumes or loose compilations begun. While twenty topics may sound meager for a search of scriptures, a lean topical approach to the scriptures is consistent with at least two contemporary works of biblical analysis. For instance, The Biblical Analysis; or A Topical Arrangement of the Instructions of the Holy Scriptures by J. U. Parsons breaks the Bible into twelve topics, which are further broken into subtopics. [24] A Topical Question Book contains forty lessons on various biblical topics. [25] Had the Mormons truly been creating a topical guide to the Bible revision, a breakdown of around twenty topics with various subtopics would have fit into a larger pattern of biblical study for the time. Perhaps this could best be thought of as a prototype of the seven “section” lessons on only one gospel topic, later published in the 1835 Doctrine and Covenants as the “Lectures on Faith.” A series of lectures on twenty topics would have been a tremendous theological undertaking for any organization, but especially for the fledgling church.

Taken together, these three volumes served an entirely different and lofty purpose before the use of the individual volumes took over. These volumes were initially intended to be a collection of gospel topics but were retooled as a minute book, a Joseph Smith journal, and a volume on the Egyptian language. Other volumes were possibly used for different purposes or were simply discarded. Historians who focused on the final purpose of these volumes actually missed a critical understanding of their original purpose.

Conclusion

This paper is not meant to be a comprehensive description of cover-related record-keeping practices, nor are the cases discussed here intended to represent Mormon record-keeping in general. Rather, these cases provide a new way of looking at Latter-day Saint sources. Historians should not focus on only the content of these sources. This approach hides many important clues that give insight not only into the sources themselves but into Mormon record-keeping and Mormon thought. Instead, historians should also analyze how documents were created, why they were created, and how they were later used. Doing so can only improve their scholarship.

Appendix

The scriptural citations found in two ledger volumes, three loose pages, and a thirty-six page grouping all contain Genesis references with section and paragraph numbers in roman numerals. The similarities between the verses inserted into Old Testament manuscript 2 and the references in the ledger volumes and loose pages allow scholars to identify the modern citation. The references are based upon each new paragraph or run of paragraphs, not by section numbers. All roman numerals have been changed to Arabic numbers.

[Joseph Smith, 1835–36 Journal, Joseph Smith Collection, Church History Library]

Repentance

Section | Paragraph | Modern Reference |

5 | 4–5 | Moses 5:5b–9 |

6 | 2 | Moses 5:14–15 |

6 | 6–7 | Moses 5:21b–27 |

7 | 1 | Moses 6:1 |

8 | 10–11 | Moses 6:23–30 |

8 | 18–20 | Moses 6:49–54 |

8 | 22 | Moses 6:56b–57 |

9 | 5 | Moses 7:9–10 |

9 | 7 | Moses 7:12–13 |

10 | 3 | Moses 8:16–17 |

10 | 5 | Moses 8:20–21 |

10 | 7–8 | Moses 8:23–26 |

Sabbath Day

Section | Paragraph | Modern Reference |

3 | 1 | Moses 3:1–3 |

9 | 22–26 | Moses 7:54–66 |

[Egyptian Alphabet Ledger Volume, Church History Library]

Faith

The page where the scriptural references would have been written is no longer in the volume, but some of the original wet ink transferred to the opposite page. While it is impossible to tell what was in all of the scriptural citations, the beginning of a word—probably Scriptures—is seen on that page, with possibly an F and a G.

[Elders’ Quorum Minute Book, Community of Christ Library-Archives]

Second Coming of Christ

Section | Paragraph | Modern Reference |

9 | 23–26 | Moses 7:58–66 |

The following group of scriptures is found several pages into the Elders’ Quorum Minute Book and does not have a heading. This seems to be a second copy of the scriptures related to the topic “Gift of the Holy Ghost,” found at the back of the volume.

Section | Paragraph | Modern Reference |

Unknown | Unknown | |

Unknown | Unknown [26] | |

8 | 11 [27] | Moses 6:25–30 |

8 | 19–20 | Moses 6:51–54 |

8 | 23–24 | Moses 6:58–61 |

8 | 26–27 | Moses 6:63–68 |

9 | 11 | Moses 7:21–27 |

10 | 7 | Moses 8:23–24 |

This small section of scriptures is found several pages into the Elders’ Quorum Minute Book and does not have a heading. Sections 1, 6, 8, 9, and 10 (the highest section number of any of the scriptural references) are the only sections with paragraph numbers this high.

Section | Paragraph | Modern Reference |

Unknown [28] | 16–19 |

Gift of the Holy Ghost

Section | Paragraph | Modern Reference |

2 | 1 | Moses 2:1–2 |

5 | 5 | Moses 5:9 |

8 | 1 | Moses 6:7 |

8 | 11 | Moses 6:25–30 |

8 | 19–20 | Moses 6:51–54 |

8 | 23–24 | Moses 6:58–61 |

8 | 26–27 | Moses 6:63–68 |

9 | 11 | Moses 7:21–27 |

[Three loose leaves, Joseph Smith Collection, Church History Library.]

Baptism

Section | Paragraph | Modern Reference |

8 | 19–20 | Moses 6:51–54 |

8 | 23–24 | Moses 6:58–61 |

8 | 27 | Moses 6:64–68 |

9 | 6 | Moses 7:11 |

10 | 7 | Moses 8:23–24 |

Priesthood after the Order of Aaron

Section | Paragraph | Modern Reference |

1 | 9 | Moses 1:15b–16 |

3 | 9–10 | Moses 3:19–20 |

3 | 12–13 | Moses 3:23–25 |

4 | 6–8 | Moses 4:14–19 |

4 | 12 | Moses 4:26–27 |

5 | 1–6 | Moses 5:1–11 |

6 | 1–2 | Moses 5:12–15 |

6 | 5 | Moses 5:18–21a |

6 | 7 | Moses 5:26–27 |

8 | 1 | Moses 6:7 |

Order of the High Priesthood

Section | Paragraph | Modern Reference |

1 | 1 | Moses 1:1–2 |

1 | 3–14, 16–25 | Moses 1:3b–42 |

2 | 1 | Moses 2:1–2 |

2 | 8 | Moses 2:26–27 |

3 | 8 | Moses 3:18 |

4 [6] [29] | 1–2 | Moses 5:12–15 |

4 [6] | 13 | Moses 5:41–42 |

4 [6] | 20 | Moses 5:58–59 |

7 | 1–3 | Moses 6:1–6 |

8 | 1–11 | Moses 6:7–30 |

8 | 13–16 | Moses 6:35–46 |

8 | 19–20 | Moses 6:51–54 |

8 | 22–27 | Moses 6:56b–68 |

9 | 1–13 | Moses 7:1–34 |

9 | 21–22 | Moses 7:53–57 |

10 | 4 | Moses 8:18–19 |

10 | 7 | Moses 8:23–24 |

[36-page grouping in 1839 history draft, Church History Library.] [30]

Covenants

This document contains some material not found in the book of Moses in the current Pearl of Great Price. Differences or important distinctions between the King James Version and the Joseph Smith Bible revision manuscript are noted in endnotes.

Section | Paragraph | Modern Reference |

9 | 20–21 | Moses 7:49–53 |

9 | 28 | Moses 8:2 |

10 | 12 | Genesis 6:17–18 [31] |

11 | 5 | Genesis 9:1–3 [32] |

11 | 8–11 | Genesis 9:8–17 [33] |

Notes

[1] Dean C. Jessee, “The Writing of Joseph Smith’s History,” BYU Studies 11, no. 4 (Summer 1971): 439–73; Howard C. Searle, “Early Mormon Historiography: Writing the History of the Mormons, 1830–1858” (PhD diss., University of California, Los Angeles, 1979).

[2] See Robin Scott Jensen, Robert J. Woodford, and Steven C. Harper, eds., Manuscript Revelation Books, facsimile edition, first volume of the Revelations and Translations series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, and Richard Lyman Bushman (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2009). A ledger volume may have been used to record the conference minutes begun in June 1830. The current version of these minutes, however, is likely a copy of a copy of the original, and thus one cannot know for certain. The pattern of Mormon record-keeping in general—and minute-taking specifically—would hint that the minutes were possibly kept on loose pages that were copied into a ledger volume—likely by John Whitmer sometime after 1833. The current version of these minutes is available in “The Conference Minutes and Record Book of Christ’s Church of Latter Day Saints,” also known as the Far West Record or Minute Book 2, found at the Church History Library, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City (hereafter CHL). Minute Book 2 is a record book created in 1838 that copies an earlier, nonextant record.

[3] This paper uses the nomenclature of the citations found in the Joseph Smith Papers. Kirtland Revelation Book (also known as Revelation Book 2), Revelations Collection, ca. 1831–76, CHL; Joseph Smith, Letterbook 1, Joseph Smith Collection, CHL; Kirtland High Council, Minutes, December 1832–November 1837 (also known as Minute Book 1 or Kirtland High Council Minute Book), CHL; Joseph Smith, 1832–34 Journal, Smith Collection.

[4] See, for instance, James M. O’Toole, “Between Veneration and Loathing: Loving and Hating Documents,” in Archives, Documentation, and Institutions of Social Memory: Essays from the Sawyer Seminar, ed. Francis X. Blouin Jr. and William G. Rosenberg (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2006), 43–53; Mark A. Greene, “The Power of Meaning: The Archival Mission in the Postmodern Age,” American Archivist 65 (Spring/

[5] Revelation Book 2, Revelations Collection; Smith Letterbook 1, Smith Collection; Minute Book 1; Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, Record, February–August 1835 (also known as Quorum of the Twelve Minute Book), CHL; Far West and Nauvoo Elders’ Certificates, 1837–38, 1840–46, CHL; “Grammar & A[l]phabet of the Egyptian Language,” Kirtland Egyptian Papers, ca. 1835–36, CHL; Kirtland Elder’s Quorum, Minute Book, Community of Christ Library-Archives.

[6] Personal e-mail correspondence with former Community of Christ archivist Ron Romig, February 11, 2009.

[7] The only exception is the Far West and Nauvoo Elders’ Certificate volume that seemed to have commenced in 1836. This does not preclude the clerks from owning the volume in the early 1830s and simply not using it until 1836.

[8] For instance, see Lyman Preston, Preston’s Treatise on Book-keeping: or, Arbitrary Rules made Plain: in Two Parts (New York: Robinson, Pratt & Co., 1842); James H. Coffin, Progressive Exercises in Book Keeping, by Single and Double Entry (Greenfield, Mass.: A. Phelps, 1836).

[9] The John Whitmer Daybook was passed down through family members until it recently was acquired by the Church History Library. This separate provenance adds further weight to the argument that these notations were made before or shortly after the volumes’ initial use.

[10] Smith Letterbook 1, Smith Collection; Revelation Book 2, Revelations Collection; Minute Book 1; Joseph Smith, 1835–36 Journal, Smith Collection; Joseph Smith, 1832–34 Journal, Smith Collection; Joseph Smith, March–September 1838 Journal, Smith Collection; Teachers Quorum Minutes, December 1834–December 1845 (also known as Missouri Teachers Quorum Minute Book), CHL.

[11] “Book of Commandments and Revelations” (also known as Revelation Book 1), CHL; Joseph Smith, Letterbook 2, Smith Collection.

[12] Kirtland Elder’s Quorum Minute Book; Quorum of the Twelve Minute Book.

[13] See Jessee, “The Writing of Joseph Smith’s History”; Searle, “Early Mormon Historiography.”

[14] An interesting yet undocumented theory places many of these original volumes in the possession of William W. Phelps after his excommunication in 1838. After he returned to fellowship in the church, and especially after he moved to Nauvoo, a dramatic surge in the use of primary sources for the history occurred, which would be explained by the return of these important documents. An alternative explanation for the increased use of primary documents would simply be a difference in historical approaches by the various scribes who worked on the history. The author is indebted to archivist Christy Best for the theory involving William W. Phelps.

[15] See Jensen and others, Manuscript Revelation Books, 659. See also 410.

[16] Jensen and others, Manuscript Revelation Books, 658–65; Minute Book 2, Smith Collection.

[17] “The record [kept by Whitmer] was subsequently obtained . . . and brought to our house, where we copied the entire record into another book, assisted a part of the time, by Dr. Levi Richards.” (Ebenezer Robinson, “Items of Personal History of the Editor,” Return 1 (September 1889): 133). Minute Book 2 is in the handwriting of Robinson and Richards, as Robinson recollects. The copied manuscript makes anachronistic reference to the 1833 publication of the Book of Commandments, indicating Whitmer copied from earlier minutes and added some commentary. Synopsis of a meeting on January 1, 1831, Minute Book 2, p. 2, Smith Collection.

[18] See, for example, the minutes of conferences held on June 9, 1830; September 26, 1830; and June 3, 1831; and the (mis)remembering of those dates in the Manuscript History. Minute Book 2, pp. 1–4; Manuscript History of the Church, 1838–56, pp. 41, 54, 118, CHL.

[19] Smith, 1835–36 Journal, Smith Collection; “Grammar & Aphabet of the Egyptian Language,” Kirtland Egyptian Papers; Kirtland Elder’s Quorum Minute Book.

[20] Frederick G. Williams, note on scriptural references, Smith Collection.

[21] A one-sentence description of the Smith Bible Revision does not do justice to the complexities and historiographical and theological implications of this important manuscript in early and current Mormon thought. A reproduction of the entire manuscript with important historiographical updating is available in Scott H. Faulring, Kent P. Jackson, and Robert J. Matthews, Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible: Original Manuscripts (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2004). Robert J. Matthews, “A Plainer Translation”: Joseph Smith’s Translation of the Bible, A History and Commentary (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1975) is still the best work on the subject, but commentary in Kent P. Jackson, The Book of Moses and the Joseph Smith Translation Manuscripts (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2005) and H. Michael Marquardt, The Four Gospels According to Joseph Smith (Longwood, FL: Xulon Press, 2007) is important to consult.

[22] For instance, the heading of current Genesis 11 was originally inscribed as “Chapter IX,” but a 13 and an 11 were both added at a later time (Faulring and others, Joseph Smith’s New Translation, 634). Several of Williams’s citations do not match either the original chapter designation or the inserted chapter or paragraph numbers.

[23] This is currently Moses 7:54–66.

[24] J. U. Parsons, The Biblical Analysis; or A Topical Arrangement of the Instructions of the Holy Scriptures. Adapted to the use of Ministers, Sabbath School and Bible Class Teachers, Family Worship, and Private Meditation (Boston: William Peirce, 1837).

[25] Joseph Banvard, A Topical Question Book, on Subjects Connected with the Plan of Salvation, Arranged in Consecutive Order; with Hints for the Assistance of Teachers. Designed for Sabbath Schools and Bible Classes (Salem, MA: John P. Jewett, 1843).

[26] Wax covers the first two lines of the scriptural citation.

[27] Wax covers part of this line; there could be more than eleven paragraphs.

[28] Wax covers part of this line.

[29] All paragraph numbers for section “IV” are on the same line. There is no paragraph 20 in section 4 or 5; Williams likely intended to write “VI.”

[30] See Dean C. Jessee, ed., The Papers of Joseph Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1989), 1:255.

[31] The Joseph Smith Bible revision manuscript adds some detail to the current verses in Genesis with respect to covenants: “But with thee will I establish my covenant, even as I have sworn unto thy father Enoch, that a remnant of thy posterity should be preserved among all Nations” (Faulring and others, Joseph Smith’s New Translation, 626).

[32] The heading to this portion of the Joseph Smith Bible revision manuscript states in part: “The covenant which God made to Noah” (Faulring and others, Joseph Smith’s New Translation, 629).

[33] The Joseph Smith Bible revision manuscript reads (angle brackets indicate insertions in the text): “And God spake unto Noah, & to his Sons with him Saying, & I, behold, will establish my covenant with you which I made unto your Father Enoch concerning your seed after you. And it shall come to pass, that evry living creature that is with you of the fowl, & of the cattle, & of the beast of the Earth that is with you, which shall go out of the Ark Shall not altogether perish; Neither shall all flesh be cut off any more by the waters of a flood; Neither shall there any more be a flood to destroy the Earth; And I will establish my covenant with you, which I made unto Enoch Concerning the remnants of your posterity. [9] And God made a covenant with Noah And said this shall be the token of the covenant I make between me & you. And for every living creature with you for perpetual generation & I will set my bow in the cloud. And it shall be for a token of a covenant between me & the Earth. And it shall come to pass, when I bring a cloud over the Earth, that the bow shall be seen in the cloud; And I will remember my covenant which I have made between me & you for every living creature <of all flesh>. And the waters Shall no more become a flood to destroy all flesh, & the bow shall be in the cloud; & I will look upon it, that I may remember the everlasting covenant which I made unto the father Enoch; that, when men should keep all my commandments; Zion should again come on the Earth, the City of Enoch which I have caught up unto myself. [10] And this is mine everlasting covenant <that I establish with you> that when thy posterity shall embrace the thruth And look upward; then Shall Zion look downward. And all the Heavens shall shake with gladness. And the Earth shall tremble with Joy; & the general assembly of the Church of the first born, shall come down out of Heaven. And possess the Earth And shall have place untill the end come. [11] And this is mine everlasting covenant which I made with thy father Enoch. And the Bow shall be in the cloud. And I will establish my covenant, unto thee which I have made between me & thee for evry living creature of all flesh that shall be upon the Earth. And God said unto Noah This is the token of the covenant, which I have established between me & thee, For all flesh that shall be upon the Earth.” (Faulring and others, Joseph Smith’s New Translation, 630–31).