Enlarging the Memory of Mormonism

Historian Andrew Jenson's Tales from the World Tour, 1895-97

Reid L. Neilson

Reid L. Neilson, “Enlarging the Memory of Mormonism: Historian Andrew Jenson’s Tales from the World Tour, 1895–97,” in Preserving the History of the Latter-day Saints, ed. Richard E. Turley Jr. and Steven C. Harper (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2010), 165–86.

Reid L. Neilson was managing director of the Church History Department of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when this article was published.

On March 26, 1895, Danish-American historian Andrew Jenson filled out a U.S. Department of State passport application in the presence of his plural wife, Emma. He was hopeful that the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles would approve his petition to personally visit all non–North American Latter-day Saint missions and local units to gather historical data.

Andrew Jenson’s passport form provides twenty-first-century observers with the basic biographical details of his life: He was born on December 11, 1850, in Torslev, Denmark. As a young boy with his parents, Jenson and his family immigrated to Utah in 1866—a move clearly motivated by their conversion to Mormonism. He became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1873. Because photographs were not attached to nineteenth-century American passports, Jenson provided the required personal physical description: Age—forty-four-years old; stature—five feet, seven inches; forehead—regular; eyes—hazel, sometimes gray; nose—aquiline (hooked); mouth—ordinary; chin—rounded; hair—light brown; complexion—fair; and face—oval. To complete the statement, “I intend to return to the United States . . . ,” Jenson wrote, “in 1897 or 1898.”[1] Regardless of what Emma may have thought of her husband’s pending lengthy journey, he was eager to go.

Weeks later, Andrew Jenson received word that the church leadership had authorized his global fact-finding mission.[2] The intrepid Dane departed from Salt Lake City on May 11, 1895, and did not return to the “City of the Saints” until June 4, 1897. Over the course of his twenty-five-month solo circumnavigation of the world, Jenson passed through the following islands, nations, and lands, in chronological order: the Hawaiian Islands, Fiji, Tonga, Samoa, New Zealand, the Cook Islands, the Society Islands, the Tuamotu Islands, Australia, Ceylon, Egypt, Syria, Palestine, Italy, France, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Prussia, Hannover, Saxony, Bavaria, Switzerland, the Netherlands, England, Wales, Ireland, and Scotland.[3]

Jenson’s global tour was an unprecedented adventure in Latter-day Saint history. In fact, no member of the First Presidency or Quorum of the Twelve had ever visited the isles of the Pacific (with the exception of Hawaii) or the continents of Asia and Australia. As the South African Mission (1865–1903) was then closed and the Japan Mission (1901–1924) had not yet opened, Jenson became the first church member to visit all the existing non-North American Latter-day Saint missions since the Mormon evangelization of the Pacific basin frontier commenced in the 1840s.

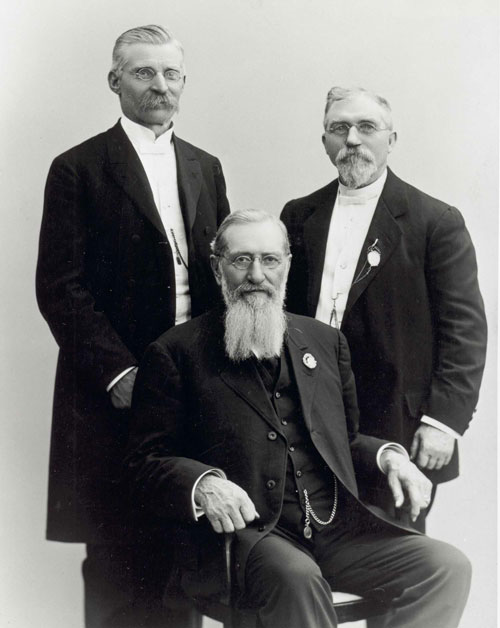

A portrait of President Joseph F. Smith with Andrew Jenson and Oluf Anderson taken while President Smith was visiting the Scandinavian Mission, of which Jenson was president. (Courtesy of Church History Library.)

The purpose of this paper is not to detail Jenson’s travels abroad but rather to sketch out the events and forces that propelled the historian on this fact-finding mission and to suggest several enduring legacies of his experiences. Jenson’s world tour was a watershed event in Mormon history. After sixty-five years of persecution and decades of exile in the American West, the church was emerging from the shadows of plural marriage, theocracy, and isolationism and adopting a new identity as part of the American mainstream and global Christianity. In fact, while Jenson was abroad, the Territory of Utah would gain American statehood. Up to that point, as historian Richard E. Turley Jr. has pointed out, the Church Historian’s Office, which sponsored Jenson’s two-year journey, had largely been focused on chronicling the history of Brigham Young and the Mormon colonization of the Great Basin Kingdom. “By the end of the century, a great opportunity existed to document and preserve the history of the Church throughout the world,” and Jenson would single-handedly jumpstart the office’s transition from a provincial to a global worldview.[4]

Jenson’s success abroad would also solidify and elevate his employment status to full-time in the Church Historian’s Office. And Jenson’s tour of the borderlands of Mormonism would later enable him to compile the Encyclopedic History of the Church, with entries on every important place in the Latter-day Saint past. While visiting the missionary outposts of Mormonism in Polynesia, Australasia, the Middle East, and Europe, Jenson trained local Latter-day Saint clerks in proper record-keeping procedures and would, in time, help formalize and standardize Mormon history-writing standards.

Enlarging the Memory of Mormonism

The idea to tour the church’s non–North American missions seems to have been the culmination of Jenson’s years of hard work domestically. In 1889 he began a series of visits to local church units to collect ecclesiastical and pioneer records. During these outings Jenson gathered information from whatever official records he could find as well as personal writings from the early settlers. A letter from the church historian informed stake presidents and bishops of Jenson’s task and encouraged them to cooperate. This official endorsement proved useful and ensured that Jenson traveled in relative comfort.[5]

Jenson often took the opportunity to address local congregations on the importance of record keeping. In the span of a little more than five years, he visited practically every stake and ward of the church in Idaho, Utah, Nevada, Arizona, Colorado, Mexico, and Canada, as well as important historical sites in the eastern United States. By March 1895 he had completed his assigned task on behalf of the Church Historian’s Office. Over the next few weeks he resumed his work indexing a history of Joseph Smith that had been published in the church’s British Millennial Star and drafting a history of the apostle Charles C. Rich and some of his associates.[6]

That April, Jenson prepared a report of his activities for his file leader Franklin D. Richards, church historian and president of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. He informed Richards that he had now visited all North American stakes and most of the wards, branches, priesthood quorums, and auxiliaries that had existed since the 1830 organization of the church. Jenson had traveled almost forty thousand miles on behalf of the Church Historian’s Office in the process. “In all my travels, public discources [sic] and private conversation I have endeavored to follow your instructions to the letter,” he wrote. “I find that a thorough reform in record-keeping throughout the stakes of Zion is necessary; the public Church records, in almost every instance, are kept in a very imperfect manner; hundreds of the original records kept in older wards years ago have been lost entirely, and others are found in the hands of private individuals and parties who have no right to them whatsoever.” Jenson further noted to Richards that he had made it a point of his visits to instruct local leaders: “I have given suggestions to clerks, recorders and others as to what ought to be written and what might be left unwritten. My instructions have generally been well received by all concerned, and as a rule I have also been well received personally and treated with due kindness.”[7]

Church leaders were impressed with Jenson’s North American labors, and after much discussion they determined to send him on an extended fact-finding mission around the world. (It is interesting to note that while the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles debated the merits of such a journey into early April, in anticipation of their decision Jenson had secured his passport by late March.) As an official representative of the Historian’s Office, Jenson was expected to replicate his domestic labors abroad so that he would have enough materials to later write histories of all the church’s missions, districts, and branches.[8]

Jenson spent the balance of April 1895 fulfilling his family and ecclesiastical responsibilities in anticipation of his projected two-year absence. He baptized his daughter Eleonore Elizabeth in the Salt Lake Tabernacle basement font and witnessed the birth of his son Harold Howell. Jenson also moved his historical materials, personal papers, and books from Rosenborg Villa, his home in southern Salt Lake Valley, to his residence a few miles north. “I took the documents to my new study in the second story of my 17th Ward home, and for several days I was busy arranging the papers in the respective shelves and pigeon holes which I had provided,” he wrote.[9] Concerned that Jenson was not paying the proper attention to his family, especially his newborn son and wife Emma, who had just endured childbirth, Elder Richards encouraged his ambitious employee to curtail his history-gathering activities until his departure. “I advised Andrew Jensen [sic] not to go to San Pete but visit & bless his family till his long journey,” Richards noted in his diary.[10]

Saturday, May 11, 1895, was the day scheduled for Jenson’s departure. “My folks packed my valises and lunch basket, and everything being ready, I called the family into the library, where I united with them in earnest prayer,” he recorded in his autobiography. Jenson then gave priesthood blessings to his two wives, children, and in-laws. “In blessing and praying with the family we were all melted to tears and the spirit of God was with us.”[11]

Late that afternoon he left his home and made his way with family and friends to the Union Pacific Railway station in Salt Lake City. At 5:20 p.m. his train pulled out, bound for Ogden, Utah, and from thence, the Pacific Northwest and British Columbia.[12] From the deepwater Canadian port of Vancouver, he crossed the Pacific Ocean by steamer, arriving in Honolulu, Hawaii. He remained in Hawaii for two months, touring the branches and districts of the Hawaiian Mission. Jenson next boarded a steamer heading to Suva, Fiji, although the isles of Melanesia hosted no Latter-day Saint congregations or missionary outposts. After the Fijian Islands he toured the Samoan Mission, at the time comprising the island nations of Samoa and Tonga.

New Zealand was next on his itinerary. In a matter of weeks Jenson came to love the Maori Latter-day Saints and their devotion to the gospel. From New Zealand he traveled east to the Society Islands and French Polynesia. Here, in the region of Mormonism’s earliest venture into the Pacific world in 1844, he stayed for nearly two months. Next he went to Australia, where he met with the members and missionaries of the Australasian Mission. Afterward Jenson made his way to the Middle East via the Indian Ocean. After Cairo and Jerusalem, he made a circular tour of Europe. He collected Latter-day Saint historical data from England, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Germany, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Wales, Ireland, and Scotland.

Jenson’s Tales from the World Tour, 1895–97

Jenson kept meticulous records during his global adventure. Not only was he gathering history; he was making it himself. Before leaving Utah he arranged to have the editors of the Church-owned Deseret Weekly News serialize his travelogue letters. Jenson hoped that Latter-day Saints in Utah would take an interest in his journey and catch the vision of proper Mormon record keeping.

His first letter, written on May 13, 1895, from Portland, Oregon, was published two weeks later on June 1 under the series title “Jenson’s Travels.”[13] Over the next year Jenson drafted regular letters chronicling his adventures in places that most Latter-day Saints would never have the means, time, or reason to visit personally. He penned his eightieth and final letter to his Deseret Weekly News readers during the summer of 1896, but it was not published until February 19, 1898, one and a half years later. “The letters have been written under many difficulties, quite a number of them on ship board, when my fellow passengers would be wrestling with seasickness or idling away their time in the smoking parlors, playing cards or other games,” Jenson explained. “The last sixteen communications, which have not been dated, were mostly written on board the steamer Orotava, on my voyage from Port Said, Egypt, to Naples, Italy, but not submitted to the editor of the ‘News’ till after my return home, June 4, 1897.”[14]

He concluded his travelogue by expressing hope that his two years abroad on behalf of the Historian’s Office would lay the foundation for future historical studies of global Mormonism. “During my mission I circumnavigated the globe, traveled about 60,000 miles, preached the Gospel on land and on sea, whenever I had the opportunity, and gathered a great deal of historical information, which I trust will prove beneficial and interesting when it is prepared hereafter and incorporated in the history of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints of the Nineteenth century.”[15]

In addition to his published correspondence, Jenson also chronicled his movements and activities in an almost-daily journal, a habit he had begun decades earlier as a young man. While his voluminous handwritten diaries remain unpublished in the Church History Library, the Danish-American historian did excerpt and print entries spanning his life as the Autobiography of Andrew Jenson in 1938, just three years before his death. Jenson devoted 161 pages (227–388) of autobiographical text to his 1895–97 world tour, or about 24 percent of the entire book. A careful comparison of the two published accounts reveals that Jenson likely used his more detailed letters as the basis for his corresponding journals. Jenson’s serialized letters total more than 210,000 words, while his parallel Autobiography passages total about 98,000 words. There is significant overlap between the two records, although “Jenson’s Travels” ends in July 1896, when he departed from the Holy Land to tour the church’s missions in Europe. Fortunately, Jenson’s Autobiography supplies the details of his final nine months in Europe as well as his homecoming in America. Reading all of “Jenson’s Travels” together with Jenson’s non-overlapping Autobiography sections provides readers with a fascinating account of his adventure.[16]

Jenson’s personal writings offer twenty-first-century readers a unique window into the Latter-day Saint past, as well as life around the world at the end of the nineteenth century. Each of his letters and Autobiography entries provides a snapshot of a particular place and time, as Jenson describes in great detail daily life and worship for native Latter-day Saints in their homelands. In terms of studying “lived religion,” few sources come close to the scope of Jenson’s writings.

In addition, Jenson tells the story of missionary life in the church’s non–North American evangelism outposts. From his letters and journal one learns that Mormonism was experienced somewhat differently by Euro-American elders and sisters and their native charges. Jenson also sheds light on the relationship between Mormon and non-Mormon missionaries in various lands as they competed for new converts, especially commenting on the strained relationships between the representatives of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints in the Pacific. He offers historical overviews of the settlement and colonization of each land and isle he visits, together with a précis of subsequent Mormon beginnings.

Always resourceful, Jenson relied on interviews with church members, missionaries, leaders, former members, other religionists, locals unconnected with religion, government officials, librarians, museum curators, newspaper editors, site docents, and anyone else whose ear he could bend. For more than two years he often worked sixteen hours a day, gathering materials to take back to Utah in his capacity as a professional (meaning paid) historian and amateur anthropologist, ethnographer, sociologist, and geographer.

While Jenson’s published letters and Autobiography offer details about the public historian, they are silent about the inner man. Jenson was quick to reveal his feelings about race, place, and space around the world, yet he was hesitant to disclose his thoughts on his family, friends, and coworkers. His writings are littered with references to his continual bouts of seasickness on the oceans, but they lack entries about homesickness for his children and wives back in Utah. Between May 1895 and June 1897 he made almost no mention of his relations. One notable exception occurred when his wife Emma traveled to Europe for a surprise meeting. Jenson devoted just a handful of sentences to their reunion, and then Emma again disappeared from his narrative. Another anomaly occurred months later when he asked the Lord in prayer if he should remain in Europe or return to Utah. Jenson wrote that he was delighted when he felt impressed to go home. Yet readers are left wondering if he was more excited to be reunited with his babies or his books, his family or his files. He noted after his train pulled into the Salt Lake City depot, twenty-five months after he left for Vancouver, “I soon caught sight of my wives, Emma and Bertha, and four of my younger children, namely, Minerva, Eleonore, Eva and Harold. They gave me a hearty welcome.” Yet that same day he went back to work unpacking his boxes and preparing his files for further historical duties.[17]

A number of reasons might account for Jenson’s lack of transparency in his personal writings. To begin with, Jenson knew that whatever he wrote would soon appear in print in one of Utah’s largest newspapers, the Deseret Weekly News, and eventually in a memoir. He was mindful that the eyes of church leaders and laity were following him as he circumnavigated the globe. Thus, everything he wrote was filtered and packaged for general Latter-day Saint consumption. Moreover, he knew that failure abroad would likely curtail domestic opportunities in the future. Jenson wanted Latter-day Saints at home to view him as competent and courageous, especially as he was spending church funds. He wanted to be seen as in control of his surroundings, mission, and emotions. And it appears that Jenson was: he never noted even fleeting moments of self-doubt or discouragement. Yet it is also possible, given his past strained relationships, that some of his coworkers in the Historian’s Office were silently rooting for his failure, jealous that he could undertake such a journey while they remained fettered to their desks in Salt Lake City.

Another possibility for the lack of private detail in his writings was that Jenson was having the adventure of a lifetime and did not suffer from bouts of homesickness or feelings of inadequacy. He seemed to treat his world tour like all the other extended missionary labors for which he was set apart. Aside from seasickness and shifting weather, Jenson experienced few trials in his travels. He appeared willing to endure anything for the cause of Mormon history writing—it was both his vocation and his avocation. Furthermore, life on the road was simple: he only had to worry about food, transportation, housing, and record keeping. Back in Utah, he had to juggle his work, church, and family commitments. He was constantly being pulled in multiple directions. But for two years he was left alone to his passion for history.

Jenson also enjoyed the celebrity of touring the church’s missions as an official representative of the presiding Brethren. Back at church headquarters, he was merely an overworked and underappreciated clerk in the Historian’s Office with an uncertain future and minimal stipend. But “traveling through the West and the nation, working with bishops, stake presidents, and mission presidents and staying in their homes, he was treated very much like a General Authority,” historian Louis Reinwand points out. “Almost invariably, he was given an opportunity to speak in local wards, and was often called upon to speak in stake conferences.”[18] Mission presidents, branch presidents, and local members did their best to accommodate his wishes and make his visits comfortable. Even non-Mormon heads of state and captains of industry in Hawaii, Tonga, Samoa, and French Polynesia agreed to be interviewed by him. Feasts and meetings were held in his honor, especially in the Pacific Isles. Perhaps Jenson rarely complained in his personal writings because there was not much to fuss about.

Jenson returned to Utah and church headquarters on June 4, 1897, twenty-five months after saying good-bye to his loved ones. He had traveled nearly 54,000 miles over land and sea by steamship, schooners, boats, trains, carriages, and jinrikisha (rickshaws), and on the backs of horses, camels, and donkeys. In addition to his historical labors, he accomplished much church work. He delivered more than 230 sermons and discourses, baptized two converts, confirmed eleven new members, blessed six children and eight adults, ordained four men to the priesthood, set apart one sister, and blessed many who were sick. Jenson further logged that he had enjoyed great vigor despite his arduous schedule: “In all my travels I enjoyed good health considering that I had been subject to so many changes in climate and diet, and returned home well satisfied with my labors. I worked hard and was in this respect perhaps more zealous than wise, for I often stuck to my task 16 hours a day.”[19] Weeks after his return, Jenson shared tales of his world tour from the pulpit in the Salt Lake Tabernacle.[20]

Legacy of Jenson’s World Tour and Historical Labors

What was the heritage of Jenson’s expedition to Mormonism abroad? How did his two-year fact-finding mission help shape the balance of his life and the Latter-day Saint historical enterprise? To begin with, Jenson’s history-gathering prowess secured him a full-time position at home in the Historian’s Office, something his previous labors failed to accomplish. On October 19, 1897, four months after his return, the First Presidency called Jenson as assistant church historian, a position he had sought for years. He was sustained by church members at the following general conference in April.

The significance of this formal calling to Jenson personally and the church institutionally cannot be overstated. It provided Jenson and his family with financial security, professional respect, and ecclesiastical support. In return, Jenson devoted the next four decades of his life to the gathering and writing of Mormon history. “Andrew Jenson’s contributions to Latter-day Saint historical literature seem almost incredible, especially in the light of his background,” Reinwand writes. “At each stage in his career Jenson exhibited a rare dedication and resourcefulness. His limitless energy and ambition—his capacity to endure, even to enjoy, the drudgery of historical research and writing—made it possible for this otherwise unpromising convert-immigrant to become one of the foremost historians of the Latter-day Saints.”[21]

During his sixty-five-year career, which began in 1876 and ended in 1941, Jenson was constantly in the harness of Mormon history. He was the “author of twenty-seven books, editor of four historical periodicals, compiler of 650 manuscript histories and indexes to nearly every important historical manuscript and published reference work, zealous collector of historical records, faithful diarist, and author of more than five thousand published biographical sketches,” according to historians Davis Bitton and Leonard J. Arrington. “Jenson may have contributed more to preserving the factual details of Latter-day Saint history than any other person. At least for sheer quantity his projects will likely remain unsurpassed. Jenson’s industry, persistence, and dogged determination in the face of rebuffs and disappointments have caused every subsequent Mormon historian to be indebted to him.”[22] It would be almost impossible—and quite irresponsible—to write on nearly any aspect of the Latter-day Saint past without first reviewing and referencing Jenson’s historical spadework.

The eventual publication of the Encyclopedic History of the Church was a second major legacy of Jenson’s global fact-finding mission. The Encyclopedic History is a condensed version of Jenson’s mission, district, stake, ward, and branch manuscript histories. Having visited nearly every local unit and historical site of the church, Jenson was uniquely qualified to compile such a reference work. He gathered much of the material he used for the many non–North American entries during his 1895–97 world tour. “On my extensive travels I have collected a vast amount of historical information, by perusing the records and documents, which have accumulated in the various stakes of Zion and the respective missionary fields. And also by culling from private journals and interviewing many persons of note and long experience in the Church,” Jenson reported to Richards upon his return in 1897.

I have also sent and brought to the Historian’s Office hundreds of records from foreign missionary fields, which were not needed abroad any more, and many more such records which I packed for shipment in different places can be expected here soon with returning Elders. My notes being gathered under different conditions and under many difficulties—often hurriedly—need careful compilation and arrangements before they can be used for history. They, however, constitute the foundation and outline for histories of nearly every stake, ward, branch, quorum, association, etc., of the Church, in its gathered state, and of every mission, conference, branch, etc., abroad, from the organization of the Church to the present time.

At the same time, Jenson admitted to Richards that it would “require years of patient toil and labor” to shape these primary source materials into accessible narratives.[23]

Over the next several decades, Jenson would personally shoulder that load as he labored to chronicle the rise and spread of Mormonism around the globe. When it was completed, the Encyclopedic History was first serialized in the Deseret News. Officially endorsed by the Corporation of the President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, it was published in 1941—Jenson’s first work copyrighted by the church. “With the publication of the Encyclopedic History of the Church I feel that my life’s work is nearly done, so far as the writing of books and historical articles are concerned,” he wrote in the volume’s preface in March 1941. “I shall soon pass on to the great beyond, leaving behind a great work yet to be done and plenty of able men and women to do it. I have done my best to contribute to the history of the Church, covering the first century of its existence, but a greater work will be done by future historians as the Church grows.”[24] Jenson died that November, just months after his final book came off the Deseret News Publishing Company press in Salt Lake City.

A third major legacy of Jenson’s world tour was the subsequent improvement and standardization of Mormon record keeping. Recall that in April 1895, while the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles were still debating whether to send him abroad, Jenson reported to Elder Franklin D. Richards on his North American history-gathering efforts thus far and pointed out the sorry state of domestic church documentation. His disheartening report may have been the catalyst that prodded church leaders to send him around the world to gather and preserve Mormonism’s global past.

Jenson’s worst fears concerning the state of local records abroad were realized as he toured the church’s non–North American missions and witnessed firsthand the deplorable state of their preservation. In June 1897 he again reported to Richards, this time on his findings in the Pacific Islands, Australasia, the Middle East, and Europe. “In some of my previous reports I have referred to the very imperfect state of our records as kept of late years throughout the Church,” Jenson wrote. “I would earnestly recommend a thorough reformation in regard to record keeping. There is a lack of system and uniformity throughout the Church, and in the recording of ordinance work, and in the making of minutes and rolls, statistical reports, annual reports, etc., etc. Each mission, stake and ward seems to have its own peculiar system, or no system at all; and until regular forms and blanks are furnished from headquarters for use throughout the entire Church, this irregularity must necessarily continue.”[25]

As assistant church historian, Jenson oversaw the creation, dissemination, and collection of standardized forms and reports used by all church missions and local units. During much of the twentieth century, all the church’s missions were responsible for sending in annual historical reports, including detailed statistics to the Church Historian’s Office, where Jenson toiled.

Postscript

Through his own hard work and the seeming hand of Providence, historian Andrew Jenson found his niche as a laborer in the cause of Mormonism. He pursued the goal of collecting and writing comprehensive, accurate, and useful histories of the church with a rare passion. Acquiring, documenting, and publishing church history was not purely a scholarly or historical pursuit for him—the untiring Danish-American believed it was a spiritual labor with eternal ramifications.

While visiting early church history sites in 1888, Jenson and his companions Edward Stevenson and Joseph S. Black encountered a number of Mormon schismatic groups. Stevenson shared with Jenson a principle that Joseph Smith had taught him in Nauvoo: “Where the true Church is, there will always be a majority of the saints, and the records and history of the Church also.”[26] Jenson apparently took this counsel to heart, for thereafter he believed that the legitimate Restoration movement would possess the physical history of Mormonism. He devoted his adult life to enlarging the institutional memory of the church and protecting what he considered to be the sacred records of the final dispensation.

Jenson preached the importance of record keeping in his many sermons and general conference addresses. “If it had not been for the writers . . . who belonged to the original Church, what would the doings of Christ mean to us?” Jenson asked the Latter-day Saints on one occasion. “And if somebody had not recorded the many other beautiful sayings of Christ and his apostles, what would we have known of the ministry of Christ and of his apostles? We would merely have had some vague ideas handed down by tradition that would lead astray more than lead aright.”[27] In other words, if not for the writers and historians of past dispensations, there would be no sacred history in the form of Hebrew and Christian scripture. The same would hold true in this dispensation, he often taught, if church members failed to keep contemporary ecclesiastical and personal histories.

Jenson had a sense of cosmic foreordination as a latter-day historian. Reflecting on the idea of “noble and great ones” chosen in the premortal life to perform specific tasks, he speculated on his own fortune:

For 4000 years I had perhaps been keeping a record of what had taken place in the spirit world. The Lord having chosen me to become a historian kept me waiting these many years from the time Adam and Eve were placed in the Garden of Eden. Then about 86 years ago (earth time) the Father of my spirit came to me and said: My son you have kept a faithful record of your brothers and sisters (my sons and daughters) who have been sent down to earth from time to time and now it is your turn to go and tabernacle in mortality. . . . At length I found myself as the Danish-born Andreas Jensen who later became universally known as the Americanized Dane Andrew Jenson the historian. Lo here I am on hand to do the work unto which I was appointed.[28]

This sense of destiny, coupled with an unmatched work ethic and passion for history, shaped Jenson’s life and work. One merely needs to search the Church History Library catalog for works by Jenson to get a glimpse of his labors.

Global Latter-day Saint history is church history. Church members need to realize that much of their most interesting history took place abroad. They must remember that the “restoration” of the gospel occurs every time a new country is dedicated by apostolic authority for proselyting. In other words, the original New York restoration of 1830 was in many ways replicated in Great Britain in 1837, Japan in 1901, Brazil in 1935, Ghana in 1970, Russia in 1989, and Mongolia in 1992. Mormon historians need to refocus their scholarly gaze from Palmyra, Kirtland, Nauvoo, and Salt Lake City to Tokyo, Santiago, Warsaw, Johannesburg, and Nairobi. Non–North American stories need to be told with greater frequency and better skill.[29]

In this sense, Jenson was a man ahead of his time. In the final years of the nineteenth century, the workhorse of the Church Historian’s Office had the foresight and willingness to dedicate two years of his life to documenting the global church and its membership. As Louis Reinwand points out, “Jenson played a vital role in keeping alive the ideal of a universal Church. He was the first to insist that Mormon history include Germans, Britons, Scandinavians, Tongans, Tahitians, and other national and cultural groups, and that Latter-day Saint history should be written in various languages for the benefit of those to whom English was not the native tongue.”[30] Back in 1895, when Jenson completed his passport application in anticipation of his two-year world tour, he likely had little inkling of the far-reaching effects his fact-finding mission would have on his life and on Mormon history.

Notes

[1] Andrew Jenson, passport application, March 26, 1895, in U.S. Passport Applications, 1795–1925 (online database), http://

[2] I consciously use the term global rather than international when referring to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints around the world. The Webster’s Third New International Dictionary defines global as “of, relating to, or involving the entire world” and international as “of, relating to, or affecting two or more nations.” Historically, the term international church has described Mormonism beyond the borders of the United States, which privileges American members: the leaders and laity living in the Great Basin are assumed to be at the center while everyone else is relegated to the periphery.

[3] Autobiography of Andrew Jenson, 386–87. My forthcoming documentary history chronicles Jenson’s entire journey (Reid L. Neilson, Enlarging the Memory of Mormonism: Andrew Jenson’s 1895–97 World Tour, forthcoming). The Religious Studies Center at Brigham Young University has generously supported the research and editing of this documentary history.

[4] Richard E. Turley Jr., “Gathering Latter-day Saint History in the Pacific,” in Pioneers in the Pacific: Memory, History, and Cultural Identity among the Latter-day Saints, ed. Grant Underwood (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2005), 148.

[5] Autobiography of Andrew Jenson, 193–94, 387.

[6] Autobiography of Andrew Jenson, 227–28, 387.

[7] Autobiography of Andrew Jenson, 227–28.

[8] Autobiography of Andrew Jenson, 228. In subsequent years these presiding quorums discussed the idea of sending other Church leaders and representatives abroad. In an April 1896 meeting of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, Francis M. Lyman proposed that at least one apostle should annually visit each of the Church’s non–North American missions. “He favored a trip around the world at least once a year by one of the Apostles,” one attendee noted. “He felt the Apostles should be in a position from personal knowledge through visiting our missions to be able to report their condition correctly to the Presidency of the Church.” Minutes of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, April 1, 1896, Anthon H. Lund Collection, typescript in Quinn Papers, Yale University Library. Moreover, Heber J. Grant, as a junior apostle, contemplated touring the missions of the Pacific on several occasions, including while serving in Japan as mission president between 1901 and 1903. Ronald W. Walker, “Strangers in a Strange Land,” in Qualities That Count: Heber J. Grant as Businessman, Missionary, and Apostle (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 2004), 249; Gregory A. Prince and Wm. Robert Wright, David O. McKay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2005), 358. The First Presidency also encouraged and financed an exploratory tour of China by two enterprising missionaries—Alma Taylor and Frederick Caine—on their way home from Japan in 1910 to determine whether they should resume the evangelization of the Chinese. See Reid L. Neilson, “Alma O. Taylor’s Fact-Finding Mission to China,” BYU Studies 40, no. 1 (2001): 177–203.

[9] Autobiography of Andrew Jenson, 228.

[10] As cited in Perkins, “Andrew Jenson: Zealous Chronologist,” 155–56.

[11] Autobiography of Andrew Jenson, 231.

[12] Autobiography of Andrew Jenson, 231.

[13] “Jenson’s Travels,” Deseret Weekly News, June 1, 1895.

[14] “Jenson’s Travels,” Deseret Weekly News, February 19, 1898.

[15] “Jenson’s Travels,” Deseret Weekly News, February 19, 1898.

[16] Jenson published his own account in Danish as Jorden Rundt: En Rejsebeskrivelse Af Andrew Jenson [Around the World: A Travelogue of Andrew Jenson] (Salt Lake City: [s.n.], 1908). I am in the process of editing and annotating both “Jenson’s Travels” and relevant portions of his Autobiography in preparation for publication.

[17] Autobiography of Andrew Jenson, 386.

[18] Reinwand, “Andrew Jenson, Latter-day Saint Historian,” 38.

[19] Autobiography of Andrew Jenson, 386–87.

[20] See “Sunday Services,” Deseret Weekly News, July 3, 1897.

[21] Reinwand, “Andrew Jenson, Latter-day Saint Historian,” 46.

[22] Bitton and Arrington, Mormons and Their Historians, 41.

[23] Autobiography of Andrew Jenson, 388.

[24] Andrew Jenson, Encyclopedic History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Publishing, 1941), iv; emphasis added.

[25] Autobiography of Andrew Jenson, 388.

[26] Autobiography of Andrew Jenson, 153.

[27] Andrew Jenson, in Ninety-Seventh Semiannual Conference of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1926), 54–59, as cited in Paul H. Peterson, “Andrew Jenson Chides the Saints,” BYU Studies 39, no. 1 (2000): 198.

[28] As cited in Perkins, “Andrew Jenson: Zealous Chronologist,” 248.

[29] Reid L. Neilson, introduction, to Global Mormonism in the Twenty-first Century, ed. Reid L. Neilson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2008), xv.

[30] Reinwand, “Andrew Jenson, Latter-day Saint Historian,” 45.