Chiasmus

Donald W. Perry, “Chiasmus,” in Preserved in Translation: Hebrew and Other Ancient Literary Forms in the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 1‒6.

"bitter for sweet, and sweet for bitter" (Isaiah 5:20)

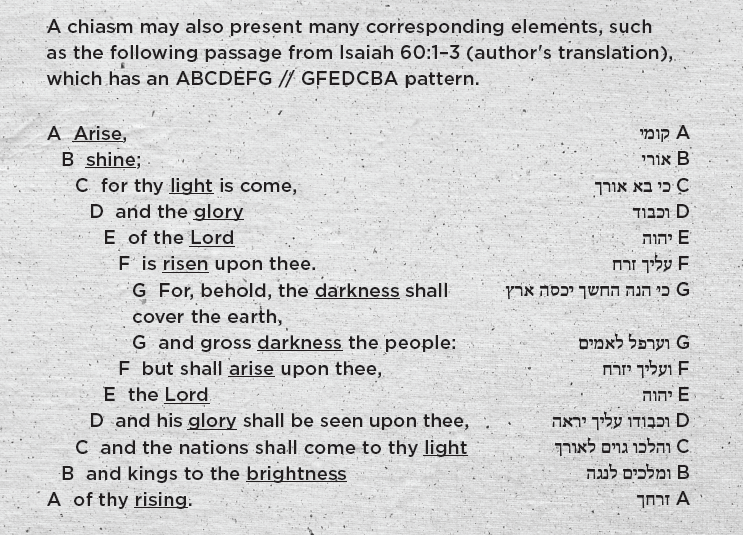

In recent years, one of the best-known forms of parallelism in the Bible has been chiasmus. Chiasmus is an inverted parallelism; it presents a series of words or ideas followed by a second presentation of similar words or ideas, but in reverse order.[1] The Old Testament has hundreds of chiasms (the book of Isaiah alone has more than one hundred),[2] varying in length from four lines to entire chapters (see, for example, 1 Kings 17–19).[3]

The following examples from the Bible and the Book of Mormon have been formatted to highlight their symmetry and to make them more readable. Key expressions are underlined to show their paired relationships.

Three examples of simple chiasmus are found in Isaiah 5:20:

A Woe unto them that call evil

B good,

B and good

A evil;

A that put darkness

B for light,

B and light

A for darkness;

A that put bitter

B for sweet,

B and sweet

A for bitter!

Here the terms evil and good are presented once and then again in reverse order, a simple chiastic inversion. The verse features two other simple chiasms based on darkness/light and bitter/sweet.

Another simple example is Isaiah 6:10:

A Make the heart of this people fat,

B and make their ears heavy,

C and shut their eyes;

C lest they see with their eyes,

B and hear with their ears,

A and understand with their heart.

The Book of Mormon contains more than three hundred instances of chiasmus,[4] each one unique, impactful, and inspiring.[5] This is a remarkable number. Second Nephi 9:20 is a beautifully simple chiasm about God’s omniscience:

A For he knoweth

B all things,

B and there is not anything

A save he knows it.

While this example is very brief, it contains clear-cut parallelisms, is nicely balanced, and delivers a forceful testimony about the knowledge of God.

In only a few lines, Alma 34:10 features a chiasm that presents essential truth about Jesus’s infinite and eternal sacrifice:

A there should be a great and last sacrifice;

B yea, not a sacrifice of man,

C neither of beast,

C neither of any manner of fowl;

B for it shall not be a human sacrifice;

A but it must be an infinite and eternal sacrifice.

Mosiah 3:18–19 gives us a chiasm focusing on Jesus Christ and his atoning blood:

A they humble themselves

B and become as little children,

C and believe that salvation was, and is, and is to come, in and through the

atoning blood of Christ, the Lord Omnipotent.

D For the natural man

E is an enemy to God,

F and has been from the fall of Adam,

F and will be, forever and ever,

E unless he yields to the enticings of the Holy Spirit,

D and putteth off the natural man

C and becometh a saint through the atonement of Christ the Lord,

B and becometh as a child,

A submissive, meek, humble . . .

Jesus Christ is clearly the focus of this passage, as can be seen by the use of the key expressions atoning blood of Christ, Lord Omnipotent, God, and atonement of Christ the Lord. This passage also gives prominence to six primary mirrored words and phrases: humble/

Mosiah 2:5–6 provides another example of a chiastic passage:

A And it came to pass that when they came up to the temple,

B they pitched their tents round about,

C every man according to his family,

D consisting of his wife, and his sons, and his daughters,

D and their sons, and their daughters, from the eldest down to the youngest,

C every family being separate one from another.

B And they pitched their tents

A round about the temple.

On the surface this chiasm may not seem very profound, but it actually teaches an important truth about family togetherness—and about families centering themselves in the temple.

Why did biblical and Book of Mormon authors use chiasmus in their writings? For one thing, repetition of words in balanced, symmetrical structures encourages and enhances learning and memorization. Also, repetition of key points or themes emphasizes the crux of a prophetic message. Finally, chiasmus encourages reading of important texts by making them aesthetically pleasing to the reader.

Notes

[1] See Welch, “Chiasm, Chiasmus,” 5:78. For an important examination of chiasmus in the ancient world, see Welch, Chiasmus in Antiquity. For the significance of chiasmus, see Welch, “What Does Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon Prove?”

[2] For a list of chiastic structures in the book of Isaiah, including key words and scriptural references, see Parry, Harmonizing Isaiah, 257–65.

[3] Elder Jeffrey R. Holland identified a chiasm spanning several chapters in the Book of Mormon (3 Nephi 11:8–18:39). See his book Christ and the New Covenant, 275.

[4] As a young missionary, John W. Welch discovered examples of chiasmus in the Book of Mormon, and in the decades since he has published a number of important articles on the topic; see the bibliography herein. For a study of chiasmus in Mesoamerican texts, see Christenson, “Chiasmus in Mesoamerican Texts.”

[5] See Parry, Poetic Parallelisms in the Book of Mormon. For a list of chiasms in the Book of Mormon, see the index of poetic forms on p. 565. A forthcoming paper of mine deals with chiasmus in the Hebrew Bible (specifically the Leningrad Codex) versus the Dead Sea Scrolls texts of Isaiah: “Chiasmus in the Text of Isaiah: MT Isaiah versus the Great Isaiah Scroll (1QIsaa),” in Chiasmus: The State of the Art, ed. Welch and Parry.