Imaging a Global Religion, American Style: Mormon Pageantry as a Ritual of Community Formation

Megan Jones

Megan Sanborn Jones, “Imaging a Global Religion, American Style: Mormon Pageantry as a Ritual of Community Formation,” in By Our Rites of Worship: Latter-day Saint Views on Ritual in Scripture, History, and Practice, ed. Daniel L. Belnap (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2013), 317–348.

Megan Sanborn Jones is an associate professor in the Department of Theatre and Media Arts at Brigham Young University.

Communities are to be distinguished, not by their falsity/

genuiness, but by the style in which they are imagined. --Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities

On July 24, 1997, an audience of over sixty-five thousand people gathered at Brigham Young University’s Cougar Stadium in Provo, Utah, to watch the Sesquicentennial Spectacular, Faith in Every Footstep, and celebrate the “remarkable pioneer heritage” shared by “all the citizens of this state.” [1] This multimillion-dollar production was performed the next night to another sold-out stadium and was broadcast over the Church satellite system to Church buildings across the world. The transmission of the event was intended to unite all members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints with the same pioneer spirit that is celebrated annually on the state holiday in Utah. In turn, the pioneer spirit shared in the broadcast pageant would serve as the basis for the construction of a global Mormon community.

Mormon pageants attempt to fix Mormon identity into a unified worldwide community through the ritualized articulation of the mission of the Church. However, pageants frequently present a complex and often contradictory representation of that community. Homi Bhaba, in The Location of Culture, suggests that cultural identity is a metaphor that exists within shifting dynamic space rather than being an ideology that is static and easily locatable. This notion of a metaphor resonates with Mormon pageants, where the spectacular elements serve as a visual symbol of the more abstract notions of specific doctrinal beliefs and a religious identity. Mormon pageants create a sense of community by crossing borders such as spiritual versus secular, global versus local, and efficacy versus entertainment and creating a unified vision of Mormon community. The result is an imagined Mormon community formed through performance that is global in its substance, but American in its style.

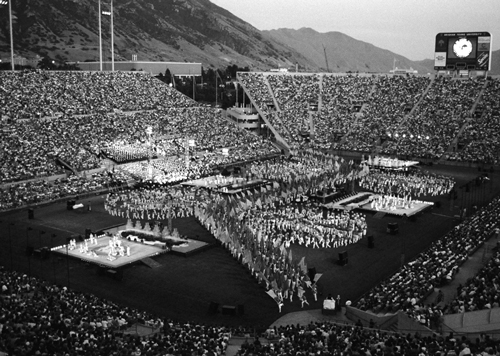

The Sesquicentennial Spectacular of 1997 was indeed spectacular. Set on four stages and a five-hundred-foot “Mormon Trail,” lit by one hundred and twenty automatic light fixtures, and with sound coming from thirty-two speaker clusters, it involved a twelve-thousand-person cast who performed around campfires, maypoles, and dancing-water fountains, with three thousand balloons, six hundred flags, two hundred confetti cannons, fourteen handcarts, and a wagon train, all under a sky of fireworks.

Fig. 1. The opening number of the Spectacular played to sold-out crowds at BYU’s Cougar Stadium. Photos courtesy of Mark Philbrick/

Ann Seamons, the co-chair of the weekend’s events (which included dance performances, a specially-constructed frontier living history museum, work stations for family history, and the rendezvous site for the hundreds of participants in a Mormon Trek reenactment) commented, “This truly was a celebration of the Savior. It was for the pioneers, but it was because of Him that they came.” [2] Seamons’s statement is more complex that it may seem at first glance. She assesses the sesquicentennial events as a celebration and identifies the cause of the celebration with the Savior through the more primary celebration of the pioneers’ arrival in Salt Lake City one hundred and fifty years early. For her, celebrating the one is celebrating the other. Her use of the pronoun “they” slips between referents—both the pioneers of the past came to Utah because of their commitment to their religion (the Savior) and by extension, the audiences attending the Sesquicentennial Spectacular are also coming to the show to celebrate the Savior. Considering the extravagance of the weekend, the notion that audience members actually had Jesus Christ in mind seems unlikely. But for Latter-day Saint audiences, particularly those from the Intermountain West, the intersection of spectacular theatrics and deep spiritual commitment is familiar.

The connection between theatrical and spiritual events also emerges in the work of performance theorist and artist Richard Schechner. Schechner’s work was significantly impacted by his close partnership with renowned anthropologist Victor Turner. The marriage of Turner’s liminality theories and Schechner’s environmental theatre work came together into the field now known as performance studies. Turner builds his notions of liminality on Arnold Van Gennep’s seminal work The Rites of Passage, in which he outlines that the initiate in rites of passage goes through three phases: separation, liminal period, and reassimiliation. The liminal period is the transition before the initiate is transformed into her or his new role. Turner defines liminal as “neither here nor there, . . . betwixt and between the positions assigned and arrayed by law, custom, convention, and ceremonial.” [3] Much of Turner’s work focuses on events and people who are “betwixt and between.”

Richard Schechner, in his famous 1968 publication “Six Axioms for Environmental Theatre” suggests a performance setting that is liminal—no dividing line between performer and actor, performed in a totally transformed or found space, and flexible focus. Schechner’s interest in the ranges of performances in life from human behavior to the performing arts to ritual to play examined the same topics as Turner, but from a different lens. [4] Together, the two men hosted a series of conferences where the connections between their two areas of study were explored and expanded. [5] This new interdisciplinary field opened up the possibility of examining performances simultaneously as theatre and ritual.

Ritual and Theatre

Latter-day Saints have been called a peculiar people, but perhaps even more so, they are a pageant people. Pageants are an integral aspect of historical and contemporary Mormon performance. In 1849, one of the earliest recorded pageants, a “jubilee,” was held to commemorate the arrival of the Saints in the Salt Lake Valley. This elaborate celebration revolved around a procession that included:

Twelve bishops, bearing banners of their wards.

Twenty-four young ladies, dressed in white, with white scarves on their right shoulders, and a wreath of white roses on their heads, each carrying the Bible and the book of Mormon; and one bearing a banner, “Hail to our Chieftain.”

Twelve more bishops, carrying flags of their wards.

Twenty-four silver greys [older men], each having a staff, painted red on the upper part, and a branch of white ribbons fastened at the top, one of them carrying the flag. [6]

After the parade, the residents participated in a round of addresses, poem, and toasts. This annual celebration has been formalized into an official Utah state holiday, which in turn has become an LDS-culture-creating theatrical event. Just as the speeches of the 1849 jubilee celebrated the glorious, not-so-distant past, later pageants such as the Pioneer Day celebrations in Salt Lake City have simplified the past into forms that can be memorialized and repeated—in other words, ritualized.

To examine performances like Mormon pageants as being simultaneously theatre and ritual is to recognize the interplay between the notions of sacred and secular, global and local, and efficacy and entertainment. Rather than considering these terms in binary opposition, performance studies suggest that they are both poles on opposite ends of a continuum. Rarely, if ever, will a ritual performance be entirely sacred with a goal only of efficacy, nor will a theatrical work be totally secular and entertaining. Both ritual and theatre are created through a manipulation of the local as a metaphor for the global. Performances move along the line of these continuums both during the performance itself and in relation to other works that are similar to it.

Pageants are a liminal space, where participants and audiences members are caught between the everyday world and the utopian world a ritual is meant to invoke. As productions entirely written, conceived, directed, composed, built, lit, and performed by members of the Church, pageants provide a significant religious activity for thousands of Saints outside their daily lives. Participation allows these members to step out of their usual environment into a time and space that is dedicated to a transformative event. Pageants also require a major time commitment to service in the Church that is meant to strengthen the LDS community and the individual participants. Rodger Sorenson, the artistic director of the Hill Cumorah Pageant from 1997 to 2004, suggests: “I think that, quite frankly, that “perfecting the saints” is the strongest thing that the Hill Cumorah Pageant does. . . . It takes 650 members every year and performs the Book of Mormon, which is the foundation scripture. Participants creatively and imaginatively live those lives. They relate directly to someone playing the Savior.” [7]

Ellen E. McHale, a non-LDS folklorist who participated in the Hill Cumorah Pageant in the summer for 1983, echoes Sorensen’s thoughts. For her, “it was the shared group experience that had the greatest impact that summer.” [8] She argues that the pageant becomes a “rite of intensification” where participants go through the three phases of a ritual. They are separated from their home environment, go through a transition in their role, changing from member to scriptural character, and are aggregated with their fellow participants (actors, missionaries, and audience) into a new religious community.

She also remembers specific testimonies where participants emphasize the individual growth they encountered. One woman bore this testimony in the closing meeting of the pageant:

“I’m really grateful for the chance that I’ve had to be here at pageant. I decided before I came that I needed to come here to strengthen my testimony, and I also made it a goal to change my personal testimony and I wanted to gain that testimony for myself. . . . I’m so grateful I came here because I felt yesterday in the Sacred Grove that it’s true. . . . I am going to go home, and I am going to be a stalwart member of the Church, and I’m not going to be comfortable any more in a rut of taking the Church for granted.” [9]

Participants are not the only Saints whose lives are perfected through Mormon pageants. Overall, most of the audience members for the various pageants are also active members of the Church. While the established annual pageants certainly play to a more mixed audience of members, inactive members, and nonmembers, commemorative pageants like the Sesquicentennial Spectacular play to an almost exclusively member audience. Audience members, too, are brought into the liminal space of the pageant, an ordinary space made special through the rituals enacted there. With their emphasis on music, dance, and special effects pageants are clearly secular performance, but their topic and intent is spiritual. They may use entertaining humor, carefully selected design schemes, and sweeping musical scores to delight and impress audiences, but the underlying purpose of the pageant is to effect change in the lives of those watching.

It is this last point, the deeply embedded goal of efficacy, which moves Mormon pageantry firmly into the realm of ritual, for without it pageants would be no more than an expensive spectacular in the style of halftime shows or large holiday celebrations. As ecological anthropologist Roy Rappaport emphasizes, “Rituals tend to be stylized, repetitive, stereotyped, often but not always decorous, and they also tend to occur at special places and at times fixed by the clock, calendar, or specified circumstances. . . . Ritual not only communicates something but is taken by those performing it to be “doing something.” [10] The performers in pageants are absolutely convinced they are “doing something”—they are using performance as a medium for the Spirit of the Lord to touch the lives of those watching in such a way that they will either embrace the gospel, strengthen an already-gained testimony, or come away with a renewed commitment to the project of family history.

Mormon Historical Pageantry

Today, the Church runs seven annual pageants. The best known is the largest pageant in the United States, the Hill Cumorah Pageant, titled America’s Witness for Christ, which has been heralded as America’s equivalent of Germany’s Oberammergau passion play. [11] Much smaller in scale is the Clarkston Pageant—Martin Harris: The Man Who Knew—where audiences are invited to a local meetinghouse for a barbecue dinner before the show begins. [12] In addition, the Church continues to stage other pageants that celebrate important dates and events. Much like rituals that are dictated by time and event, these celebratory pageants mark special events in Church history or the world. The repetition of the celebrations either annually or at commemorative years ritualizes the stories told into myths of origin, passage, and divinity.

Since 1995, there have been two such commemorative pageants—The Light of the World pageant for the 2002 Winter Olympics held in Salt Lake City and the 1997 Sesquicentennial Spectacular, Faith in Every Footstep, performed at the 150th anniversary celebration of the arrival of the pioneers in the Salt Lake Valley. David Glassberg calls these types of celebratory pageants “public historical pageantry” and points to their widespread production in the early twentieth century in the United States, especially in smaller communities, which used the historical imagery to define a sense of identity and direction. He argues: “The social and cultural transformations that historical pageants both embodied and attempted to bridge . . . continue to shape the way we use the past to inform the present. Like the generations before us, we look to history for public confirmation of our personal experiences, family traditions, and ethnic heritage, as well as some level of collective identity and common culture.” [13] The same tactics that informed the early pageant’s labor of community formation is at play in the 1997 Sesquicentennial Spectacular. The images of a common history presented by the staged review of the formation of any community, state, or in this case, global religious culture, provide a focus for unifying loyalties. At the same time, this narrative provides a structure for individual memories and a larger context within which to interpret new experiences. This is true even for members without a pioneer heritage. The frequent repetition of the stories and wide dissemination of the narrative provides a shared history for all members of the Church.

In choosing what will be represented by historical pageants, what is remembered becomes all the more powerful in light of all that has been excluded by privileging this one particular version of history. In many ways, the pageant event’s narrative sets up a juxtaposition between what is perceived as the progress of modernity and reliance on tradition and between mass society and the intimacies of community. Ultimately, pageant celebrations such as the Sesquicentennial Spectacular supply an orientation toward future action, defined by the relationship between the culture shaped by the event and the world that is defined as outside the community.

Finally, as Glassberg suggests, historical pageants are not merely celebratory, but serve a specific ideological agenda and have material repercussions. He says that these pageants are built on “the belief that history could be made into a dramatic public ritual through which the residents of a town, by acting out the right version of their past, could bring about some kind of future social and political transformation.” [14] This notion of transformation is at the heart of the connections between theatre and religion.

Earlier scholars of religion, ritual, and drama saw ritual and theatre as diametrically opposed. [15] Ritual was private, sacred, real, and believable, while theatre was popular entertainment, trifling, constructed, and overtly make-believe. By suggesting that all behaviors are performances, performance studies foregrounds the similarities between theatre and ritual. Theatre is like ritual in its staging—focus is tightly controlled, gestures have meaning, significant elements echo and repeat. Theatre, like ritual, is ephemeral—once performed, it disappears. Perhaps most importantly, theatre is like ritual in the shared experience that the audience has around the performative event—both those watching and those participating come together in communitas.

Communitas is Turner’s notion of the state of communion and of community that is achieved by participants in a ritual. For Turner, there is a wide range of communitas. On one end is normative communitas, where participants are united in a ritual act that is meant to effect a common response but one that not all may actually achieve. Latter-day Saint participation in the sacrament each Sunday might be an example of normative communitas where each member is meant to achieve oneness with the Spirit, but not all actually will. On the other end is spontaneous communitas, where all united through the ritual are truly connected and irrevocably transported by the event. Early Church pentecostal events might be examples of spontaneous communitas. For example, Elder George A. Smith testified that “on the evening after the dedication of the [Kirtland] Temple, hundreds of the brethren received the ministering of angels, saw the light and personages of angels, and bore testimony of it. They spake in new tongues, and had a greater manifestation of the power of God than that described by Luke on the day of Pentecost.” [16]

Presumably, this “manifestation of power” of “hundreds of brethren” displayed the markers of spontaneous communitas as described by Turner: “When the mood, style, or ‘fit’ of spontaneous communitas is upon us, we place a high value on personal honesty, openness, and lack of pretensions or pretentiousness. We feel that it is important to relate directly to another person as he presents himself in the here-and-now, to understand him in a sympathetic way, free from the culturally defined encumbrances of his role, status, reputation, class, caste, sex, or other structural niche. Individuals who interact with one another in the mode of spontaneous communitas become totally absorbed into a single synchronized, fluid event.” [17] Pageant performance moves between these two modes of communitas. For performers, the participation in a pageant might allow them to move to transformation through spontaneous communitas. There has been some interest from a variety of fields on the experience of ritual performers. [18] My interest, however, is more on the audiences attending Mormon pageants and how their encounters with this theatre-ritual performance serve to transport or even transform them into members of a Mormon community. [19]

Community and Culture

While the terms community and culture are discrete ideas, each relating to specific group dynamics, they reflect the bifurcated way Mormons view themselves and are viewed by others. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is not a nation in terms of a group with discreet boundaries beyond which other nations exist. The entire proselytizing mission of the Church, however, is a global attempt to convert the world in preparation for a millennial “kingdom of God.” This idea of a literal future kingdom is echoed by observers of the Mormon phenomenon, as is manifested by articles such as Time magazine’s “Kingdom Come: The Mormon Financial Empire,” which appeared the year before the Sesquicentennial Spectacular. Organizationally, the Mormon community refers to the geographically bound congregational units of wards, stakes, and regions. But as each of these units is part of a worldwide institution, the Mormon community can justifiably be seen more as an international than a national entity.

The concept of an LDS culture points to the idiosyncrasies that define Mormon life beyond doctrinal peculiarities. While these cultural behaviors may vary according to geographic region, there are clearly identifiable tropes that are common to all LDS communities. Even more identifiable may be the social, linguistic, and ideological mores that emerge from Utah Mormon culture. The nucleus of the Church in Salt Lake City defines in great part the actions, behaviors, and responses of its borders: modeling culture, organizing community, and planning for the global community.

There is a tendency to conflate any member of the LDS religion to its center in Utah both in popular culture and in ethnographic and cultural studies. In the Encyclopedia of World Cultures, for example, “Mormons” appears only in Volume I: North America. According to this entry, Mormons are located “in the intermountain region of the western United States, especially in the state of Utah, a distinct cultural region labeled by cultural geographers as the Mormon Region.” [20] Despite current statistics that show the majority of the members of the LDS religion live outside the continental United States, this view of Mormons living in western America persists.

There is a shift from the geographically insular beginnings of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to its current mission of global expansion. The early years of the Church were marked by a community gathering that eventually saw most American Mormons as well as converts from Europe migrate west to the Great Salt Lake. Once this central capital was established, the Church then sent out settlers to colonize much of the west up into Canada, as far south as Mexico, and among the islands of Polynesia. The concentration of members, however, was in the state of Utah, and there it has remained. The demographics are such that while Utah now no longer has the sheer numbers of members as even California, it still retains the highest percentage of members of any place in the world.

Today, the Church no longer encourages immigration. There have been directives for members to become involved members of their own communities, for students to attend local universities, and for converts outside the United States to remain in their own countries and strengthen the Church from there. For all these efforts, however, Utah remains in popular imagination for both those within and without Mormonism as the cultural center, while those within Utah consider the rest of the world to be “the mission field.” As a result, Utah is molded by a very particular weight. To outsiders, even members from the Mormon diaspora, it is a place with behaviors, practices, and language that create a culture that in many ways has no doctrinal relation to the teachings of the Church, but which reflects itself back into their communities.

The particular cultural shape that a community assumes will always be in large measure predetermined for the individual contemplating his or her place in it. At the same time, the individual’s sense of identity draws on the historical narratives in circulation. For Mormons, the communal sense of a shared history is reaffirmed by the Church’s powerful and pervasive vision of the past that is enacted and repeated for all members from the pulpit, in approved Church educational materials, and through media representations like the broadcasting of the Sesquicentennial Spectacular.

Susan Bennett, in her work on theatre audiences, suggests that an audience’s experience of performance is modeled on two frames: the outer frame is a cultural construct defined by the selection of material for production and the spectator’s definitions and expectations of performance. The inner frame contains the performance event itself and the audience’s experience of the fictional stage world. Bennett suggests it is the intersection of the two frames that forms both the audience’s cultural understanding and experience of performance. She states, “Cultural assumptions affect performances, and performances rewrite cultural assumptions.” [21] This mutually dependent connection between a community’s culture and the performances it creates points to the ways in which Mormon pageant performances enact a particular style of community.

The Sesquicentennial Spectacular

Examining the content of the Sesquicentennial Spectacular’s production numbers and the style of their articulation reveals tensions in three specifics sites: spiritual/

The transformation expected Mormon pageants generally, and the Sesquicentennial Spectacular specifically, parallels the Church’s mission: to (1) proclaim the gospel, (2) perfect the Saints, and (3) redeem the dead. Taken together, these goals are each aspects of community formation—the Latter-day Saint community is made up of a unified group of established or new members who work together to build their testimonies of the gospel through active engagement with the past (the dead), the present (the Saints), and the future (spreading the gospel to the world). The culture of the LDS community is inextricable from its mission, and pageants enact, celebrate, and reaffirm this mission as a ritual of community formation.

Spiritual/ secular

Cougar Stadium seats sixty-five thousand people, and every seat was full for both nights of the Spectacular. Add to this the six thousand participants from the MTC, the crew running the entire production, the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, the Mormon Youth Symphony, most of the Apostles of the Church with their security details, and visiting dignitaries with their entourages, and one can see how parking was a big problem. While this seems an unimportant detail, the event of getting to an event is an integral aspect of the overall performance experience. Audiences were forced to park sometimes miles away and walk with crowds of people. Traffic was stopped to make room for the pedestrians all traveling together in a pilgrimage to the stadium. There audiences were greeted by a medley of sacred hymns and welcomed by Elders M. Russell Ballard and Jeffrey R. Holland.

The access to the production was one of the semiotic structures, or meaning-making systems, framing the Spectacular that reveals how pageant performance crosses lines of spiritual and secular. The secular elements are clear: required tickets; a football stadium reworked as a performance stage; prerecorded music; high-budget costumes, sets, and props; and fireworks. At the same time, Mormon pageants are never intended to be just entertainment; they are conceived as a spiritual message and produced in order to send that message to the hearts of the audience members. This was made clear by the introduction the production, which was performed like a typical Sunday meetings. The Spectacular was presided over by a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, who introduced the program to follow. President Gordon B. Hinckley shared opening remarks and called on Elder Thomas S. Monson for an opening prayer. In addition to the spiritual agenda, the spiritual message of the Spectacular was so much a part of the production that each element of the event was carefully selected to provide an atmosphere in which the Spirit could enter in.

In Latter-day Saint culture, outward signs of the Spirit are frequently emotional—flushed face, pounding heart, quickened breath, and weeping. As these signs, particularly tears, are evident to those viewing the person so moved, the repetition of particular behaviors becomes ritualized. In other words, the more people who publicly connect their crying to feeling the Spirit, the more feeling the Spirit is likely to evoke crying. The phenomena of emotional outpourings as a sign of spiritual sensitivity is so pervasive that Church rhetoric at times reverses the cause and effect: congregants are advised that if they find themselves crying in a spiritual setting, they might be feeling the Spirit.

Being touched by emotions is not exclusive to the realm of spirituality, however. Secular performance can also move audience members to laughter, terror, and tears through the careful manipulation of the elements of theatre; music, lighting, acting, story, and compositional choices all have the ability to evoke strong emotion. In pageants like the Sesquicentennial Spectacular, the spiritual and the secular are far from an opposition, they in fact overlap. The pageant was undeniably moving—a swelling score, beautiful composition, and particularly touching scenes such as the death of a baby brought into larger-than-life focus through projection on stadium display screens. The emotions that were felt by the audience were caught in a spiritual-secular loop. Did audience members cry because they felt the Spirit or because the scene was particularly well staged? This question is frankly unanswerable, but clearly, spiritual and secular borders are crossed in how the past is invoked through this ritual/

All pageants, whether annual or commemorative, include aspects of Church history: scriptural, Restoration, or pioneer stories. I have argued elsewhere that the staging of Church history in reenactments or pageants is an alternate way for believers to proxy their ancestors, or redeem the dead. [22] Witnessing a repeated performance of the past is a way to hold that moment open in the memory of the viewer. In his essay “History, Memory, Necrophilia,” Joseph Roach suggests that some performances reveal an “urgent but often disguised passion: the desire to communicate physically with the past, a desire that roots itself in the ambivalent love of the dead.” [23] Building on his work in Cities of the Dead, Roach suggests that effigy is not only the noun meaning a portrait, a likeness, or an inanimate reconstruction of a living being, but that effigy is also a verb, little in use, that evokes the presence of an absence, particularly to “body forth” something from the distant past.

Perhaps the most-repeated episode in pageant performance is pioneers in wagons and handcarts. The Sesquicentennial Spectacular was no exception—one of the highlights of the evening was a parade of hundreds of “pioneers.” Typically accompanying the pioneers in such performances are the requisite costumes and conveyances. Also accompanying them is the unspoken echo of the pioneer stories deeply embedded in Mormon oral tradition. While the audience knows that the actors are not really pioneers, in a sense, they could be pioneers. The performance slips between past and present as the past is effigied for the audience, if not through realistic staging, then certainly through metaphorical interventions. The literal embodiment of the dead brings to the forefront the doctrinal imperative to redeem these dead as the pioneers are (re)created before the audience’s eyes.

The production of the Sesquicentennial Celebration was entitled Faith in Every Footstep. This slogan circulated throughout Church literature for almost a year before the event, with the intent of reminding Church members of their pioneer heritage and prompting them to reexamine their own lives for an understanding of the ways in which faithfully following current Church doctrine is a labor not unlike that of the early pioneers. As Elder Holland, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, suggested in his opening remarks, the Sesquicentennial Spectacular’s presentation of music, dance and “our unique expression of testimony” should encourage audience members to “pick up the flickering pioneer torch, rekindle it, and go forward to even greater heights.”

Fig. 2. Elder Jeffrey R. Holland introduced the Spectacular. Note some of the “spectacular elements” like the water fountain surrounding the stage.

Fig. 2. Elder Jeffrey R. Holland introduced the Spectacular. Note some of the “spectacular elements” like the water fountain surrounding the stage.

The production started with a restaging of the history of the Latter-day Saints. Wildly simplified yet containing many of the now-monumentalized moments of Latter-day Saint history, this historical reenactment contributed to the building up of the Mormon community. In the retelling of the story through music and stylized and repetitive movement, the narrative became unifying history that bound all audience members (all Church members) in the face of ridicule and persecution. In his work on the Mormon Trail, Wallace Stegner suggests the impact of this type of historical ritual: “Any people in a new land may be pardoned for being solicitous about their history: they create it, in a sense, by remembering it.” [24]

The prologue to the Spectacular, surprisingly reminiscent of the 1849 jubilee, saw hundreds of children and young adults dressed in yellow carrying an enormous flower garland which lined the stadium path. Following the children were President Gordon B. Hinckley and his two counselors, Thomas S. Monson and James E. Faust, each walking hand in hand with some of their grandchildren. Presidents Hinckley and Monson introduced the event that outlined the activities of the day, congratulated participants, and invoked a blessing on the evening’s performance.

As part of President Hinckley’s comments, he asked the audience to remember specifically “the great trilogy” of pioneer events—the first wagon trains west from Winter Quarters, the march of the Mormon Battalion, and the ocean passage of the ship Brooklyn. His emphasis on the seminal pioneer events being celebrated points to the ways in which communal memory is formed around what Michael Raposa suggests are “repeated acts of attention directed by members to significant episodes in its sacred history.” Raposa continues: “Ritual participants develop the capacity to extend in memory and in hope their bonds of connectedness to various individuals and events, many located in an ancient past or a distant future that they as individuals have never experienced. Nevertheless, the meaning of their own lived experience is in great measure shaped by this sacred past and future, in much the same way that any given scientific experiment presupposes a complex history of investigation and defines its immediate purpose in terms of inquiry’s long-term objectives.” [25]

The Church history segment of the Spectacular functioned in just this way. The opening number by the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, “We Are the Mormon Pioneers,” began with the story of the Church from its beginnings with Joseph Smith and traced the conversion and immigration of one family to Nauvoo, Illinois, then on to Utah. The history created by these performers confirmed the image of the typical Mormon family with an attractive blonde wife, her tall, dark, and handsome husband, and their three lovely girls. Their trials included being driven out of Nauvoo by a mob and losing a newborn baby boy on their journey across the plains. The family faced their trials through song and dance—another area where the sacred and secular were blended.

The music in the segment included an eclectic mix, from songs written specifically for the spectacular, such as “A Witness and a Warning”; to religious hymns, specifically “Come, Come, Ye Saints”; to songs from Broadway musicals, like “Children of the Wind” from Rags. The songs all served the story of Polly and George and were carefully staged as musical theatre highlights, but because of the subject matter and the production elements, inspired the same respect as sacred music. The songs simultaneously functioned as secular and spiritual and were highlighted with modern dances of represented aspects of the journey and square dances performed around the fires of the pioneer campsite. The story of the settlers continued in this manner until they reached the Salt Lake Valley.

A voiceover presentation then recounted the arrival of the Saints in the valley (one hundred fifty years earlier to the day). Sick from a fever, Brigham Young saw the valley from the back of a wagon and stated, “It is enough. This is the right place. Drive on.” This quote is commonly shortened to “This is the place”—a phrase whose repetition is so ritualized in popular Mormon culture that it served as a bridge between past and present for pageant audiences.

Fig. 3. The wagon train reaches the Salt Lake Valley.

In the pageant song, the lyrics remind the audiences, “Brigham Young said, ‘This is the place. / This wide open space is my home.’” Hearing this, the audiences are connected to Raposa’s “ancient past. . . that they as individuals have never experienced.” In the final segment of the Church history sequence of the pageant, sacred and secular become nearly indistinguishable. The very secular space of Cougar Stadium is made sacred through the ritualized musical chant “This is the place”—a fulfilling of geographical prophecy. As Latter-day Saint audiences connect with a sacred space that has been invoked, they are reminded that they are intimately connected to this sacred past and that they owe at least a debt of gratitude or possibly even salvation to those who came before.

Global/

The opening remarks of the Sesquicentennial Spectacular included this statement: “As citizens of this State, we share a remarkable pioneer heritage.” This suggests the audience is made up of Utah citizens, not necessarily all aligned with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, but also recognizes that it was the Church’s pioneer project that founded the state. The audience identified in the statement is complicated by the fact that advertising for the production was limited to announcements from church pulpits to congregations. Even with this limited advertisement (and competitively priced tickets), the Spectacular sold out within a few hours.

The show itself was filmed during its production and broadcast live through the KBYU network (the BYU student-run public access station) to anyone receiving the channel in Utah and Southern Idaho, and was televised over the Church satellite system, which is linked to major Church buildings in most Western countries. The result was a production, ostensibly created for a state celebration, which in fact had a very specific audience base. Viewers were limited not just to members of the Church, but members in the United States and those countries whose chapels support a satellite system.

One of the major intents of the Spectacular, however, was to celebrate the modern pioneer spirit, which was represented by the Church’s global expansion. The middle segment of the pageant was entirely devoted to celebrating how pioneers made a literal journey for Christ and how people all over the world are now coming to him in other ways. As the voiceover that introduced the segment intoned, “And so they came, and still they come today.” The staging of this global vision, however, was imagined for the almost exclusively Caucasian Latter-day Saint audience defined by the narrow dissemination of the production. The result was a crossing of global and local lines where the local—Utah Mormon—was introduced to the global—nations from around the world—in a style that corresponded far more to the local than the global.

The tensions between the imaginary global and local reality highlight the Church focus on the individual and his or her growth in the gospel, or the mission to perfect the Saints. All members are meant to grow in the gospel, participate in civic responsibilities, and strengthen their local communities. For Utah Mormons, these injunctions overlap as the civic community and the church community are nearly identical. The local is the global, so working towards perfection of the Saints of necessity is perceived as also working towards the perfection of the larger population.

Interestingly, pageants targeted for nonmember audiences and those for member audiences, like the Spectacular, are not discernibly different. The same stories are told in the same style; similar-sounding music backs the performances; the emphasis is always on spectacular effects; and the doctrinal messages of endurance, sacrifice, the living Christ, and the restoration of the gospel are indistinguishable. The apparent disregard for audience demographics could be read a number of ways—that the basic principles and important stories of the gospel are basic and appropriate for all people, that the Church is always preaching to those who know the least about the Church because those with more knowledge will still understand, or that the official history of the Church is made acceptable primarily for an exterior view rather than an interior one. Each of these views, however, shows once again that the local style infuses the global articulation.

This analysis also points to one of the more formal functions of ritual. A number of ritual scholars have argued the same point—that “ritual is a way of maintaining the social-political status quo and of keeping in power those who are already in power.” [26] Obviously, a religious pageant celebrating a sacred moment from its history is not going to use the performance as a space to call the event, belief in the event, or belief more generally into question. Instead, pageants are used to maintain continued consistency in the way in which the past is remembered. Eric Hobshwam calls this aspect of ritual “inventing tradition.” [27]

While inventing tradition, or maintaining the status quo, is ethically neutral, it is easy to see how this controlling aspect of ritual might lead to problems of representation depending on what version of an official history, culture, or tradition the powers that be wish to reaffirm. In the Sesquicentennial Spectacular, the casting and costuming complicate the global/

Frederick N. Bohrer suggests how exoticism functions in Western culture in his critical analysis Orientalism and Visual Culture. For Bohrer, the object of exotic interest is always assimilated—it must resist expectations to a certain extent in order to be exotic, but in the end, it cannot be totally different from what the audience already imagines. As a result, the exotic object “is ultimately (even if only provisionally) assimilated in the very norm it begins by challenging.” [28] Two of the dances that were performed back to back in this segment of the Spectacular might serve to illustrate this point.

The first was a production of Native American dances, performed by Living Legends. Living Legends is a group devoted to Native American, Latin American, and Polynesian dance performed exclusively by BYU students from these various ethnic backgrounds. [29] The dance itself was a collection of a number of different tribal dances selected not for their spiritual meaning or tribal importance but for their showy costumes and flashy tricks.

Fig. 4. Living Legend performance of a Native American Hoop Dance.

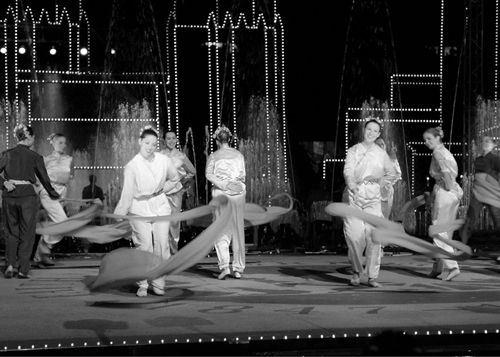

The next was an “Asian” dance performed by Folk Dancers dressed in silk pantsuits and waving silk streamers. The music, style of dancing, and dancers themselves (all Caucasian women with eye makeup to look Asian) give no clue as to what specific country they are meant to represent. Instead, they give a general feel of an exotic Eastern dance.

The intent of both of these numbers is clearly to represent (along with Polynesian, Scandinavian, Cossack, and Jewish dances) as many different countries as possible. The style of ethnicity, however, reveals that these international dances are foreign only insofar as the difference is pleasing to the Utah audience while still being familiar enough to Western culture for comfort.

Fig. 5. The BYU Folk Dance Team’s Asian dance. Note the cityscape outline of lights behind the performers.

I am not unaware that the industry standard for folk dance companies is to present a wide range of ethnic dances with little or no consideration for “authenticity” in casting. Pointing out the use of clearly Caucasian women to represent Asia is not necessarily a call to rework folk dance traditions. It is, however, a perfect example of how the Sesquicentennial Spectacular presented a global vision in a specifically American style. If the emphasis for pageant organizers was to truly celebrate the international spirit of the Church, they could have cast the show using a wider variety of ethnic groups. My point is that the pageant was not trying to represent the global reality of the production, but that instead, was reinstating a uniquely American vision of the larger world.

Beyond the obvious issues of ethnic representation, these vignettes affirm the American (local) center of the “world” being constructed through the pageant. This is made most clear with the introduction of enormous cityscapes of lights as the backdrops for this segment of the Pageant. Central behind the main stage where the dancers were performing was an enormous Salt Lake Temple and buildings from Temple Square. Further along the stadium were other cityscapes: Paris with the Eiffel Tower, London and Big Ben, a Pagoda town, and another Asian-looking city. The representations here fix a particular image of community for the audience that corresponds less to the actualities of the community, or even to the desire for global community alluded to by introductory speakers. Instead, the reality is a global vision in a sanitized, spectacular style that points more to the way in which Americans view the world. The ritual of community making here is controlled to keep the style of the performance in a way that is comfortable to the official culture and promotes a very particular saint to be perfected.

Efficacy/

The highlight of the Spectacular was its finale entrance of six thousand missionaries from the Provo Missionary Training Center who marched onto the field carrying flags from the different countries in which they would be serving. A voiceover greeted the audience on behalf of the missionaries in all the different languages represented by the flags. The missionaries seemed delighted to be in the production and the audience seemed even more delighted to watch them. Despite obvious instructions for decorum, many of the missionaries could not resist playing to the cameras filming them with a youthful excitement that was far more entertaining than moving. Their singing of “Called to Serve” with the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, however, also brought the audience to their feet as they sang along with real belief in the missionary message to proclaim the gospel.

Schechner proposes that the efficacy/

| Efficacy/ |

Entertainment/ |

|

Results Timeless time—the eternal present Performer possessed, in trance Traditional scripts and behaviors Transformation of self possible Audience participates Audience believes Criticism discouraged Collective creativity |

For fun Historical time and/ Performer self-aware, in control New and traditional scripts and behaviors Transformation of self unlikely Audience observes Audience appreciates, evaluates Criticism flourishes Individual creativity |

The Spectacular’s final segment, which celebrated the missionary spirit of the Church, is typical of how this ritual/

Mormon pageants are first and foremost vehicles to proclaim the gospel. While the majority of audiences may be made up of members of the Church, the intended audience of the productions is always a nonmember one. For example, the Nauvoo Pageant was developed specifically as a missionary project. The cast is a mix of twenty professional actors and a chorus of one hundred and forty families who volunteer for the production. The goal of cast members is clearly stated by pageant organizers: “Participation in the Nauvoo Pageant cast is a missionary experience for families and individuals. Participants will have many opportunities to share the gospel message with audience members and other visitors in Nauvoo while hosting the [pre-show] celebration and performing in the pageant.” [31]

When not rehearsing scenes, cast members are taught techniques for sharing the gospel, including a “welcoming dialogue” that introduces audiences to the show and invites them to accept a copy of the Book of Mormon or fill out referral cards so that full-time missionaries can contact them in their homes. While celebratory pageants like the Sesquicentennial Spectacular don’t have proselyting as their primary function, they are still created with a non-Mormon audience member in mind. This was particularly evident in the rhetoric used to introduce the pageant, which let audiences know that it was a production of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, that Utah was founded by Mormon pioneers, and that the production was a celebration of a Utah State holiday. Additionally, a portion of the introduction welcomed the visiting dignitaries who were attending the event, making these nonmembers a central part of the audience, even though their actual numbers were so small as to be insignificant.

The importance of the missionary aspect rests in its goal of conversion—the strongest efficacy goal of the pageant. In his address to the Church at General Conference in April 1997, just months before the Spectacular, President Gordon B. Hinckley suggested: “This great pioneering movement of more than a century ago goes forward with latter-day pioneers. Today pioneer blood flows in our veins just as it did with those who walked west. It’s the essence of our courage to face modern-day mountains and our commitment to carry on. The faith of those early pioneers burns still, and nations are being blessed by latter-day pioneers who possess a clear vision of this work of the Lord.” [32]

Most important for this pioneer spirit is the way in which Church members share their beliefs with their friends and neighbors. Proclaiming the gospel is an imperative for the fifty thousand full-time missionaries and for “member-missionaries” alike. The missionary aspect of the Sesquicentennial Spectacular ritualized its message though its careful mediation of efficacy and entertainment. The objective of the finale is clear—to inspire the audience with the zeal of missionary work through the erasure of difference and collective creativity. The unifying white shirts and dark pants or skirts worn by the thousands of missionaries in the stands erased differences, just as the flags signifying the many countries where the missionaries would serve foregrounded the global scope of that unity. Singing the hymn “Called to Serve” brought the audience into a unified community due to its culturally specific meaning.

Fig. 6. Missionaries singing “Called to Serve” as part of the finale number.

This beloved hymn is a sign within the structure of Mormon culture, and as such has a particular significance that can only be discovered through knowledge of the codes that give it meaning. This may be true of all ritual—one must be a member of the community in order to access the community-specific meanings embedded in the performance. Members of other faiths might view this production number and still gain pleasure from its aesthetic qualities. The sight of the missionaries that prompted a standing ovation was undeniably entertaining. But to move from entertainment to efficacy, from theatre to ritual, one must already be a part of the Mormon community to understand the full impact of this song on the proceedings.

Sometimes the pageant, however, was only entertaining. Of particular note was the variety of special effects that punctuated every segment of the show. Joseph Smith pulled golden plates out of a cavity that glowed from within; fireworks shot into the sky three separate times. Some of the pageant was clearly on the side of efficacy, becoming overt preaching of the mission of the Church. Most of the pageant, however, moved back and forth between entertainment and efficacy. Audiences responded to these segments as ritual or theatre depending on their particular connection to the liminal space created and their openness of entering into communitas and into the Mormon missionary spirit.

Conclusion

Benedict Anderson, in his work Imagined Communities, argues that even the “most messianic nationalists do not dream of a day when all the members of the human race will join their nation in the way that is was possible, in certain epochs, for, say, Christians to dream of a wholly Christian planet.” [33] The Sesquicentennial Spectacular disproves his point with its repeated rhetoric of the future kingdom of God where the LDS gospel will spread over the whole earth. This mission of the Church to bring about a new kingdom of God on earth stands contrary to Anderson’s argument that nations are imagined as being limited because even the largest of nations has finite, if flexible, boundaries defining the interior and separating from other exterior nations. Members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints do indeed imagine a day in which every human being on the planet will be joined.

Harold Bloom suggests that while missionary zeal is not limited to the Mormon faith, the Church pursues its vision to a unique degree, that “no other American religious movement is so ambitious, and no rival even remotely approaches the spiritual audacity that drives endlessly towards accomplishing a titanic design. The Mormons fully intend to convert the nation and the world.” [34] The last Spectacular number before the finale, “Pioneers of the Heart” underlines this far-reaching goal. A young Caucasian man sang to the audience that as human beings, we have crossed all boundaries of modern technology, as:

We have learned to split the atom

Computers link the earth

We have lived to see a man walk on the moon,

We’ve saved the Amazon’s rainforests

And the whales of Newfoundland,

Breaking down the gap between generations

Building bridges connecting every nation

We are pioneers of the heart.

The woman who earlier played Polly the pioneer, now dressed in contemporary clothes, joins him in the song. Her appearance models for the audience the shift they are meant to effect—to take inspiration from the lives of the pioneers to become modern-day “pioneers of the heart.”

The song was illustrated by images of charity that made clear the style of this international message. The first tableau was a white doctor and a sister missionary bringing health care to a Latina and her two children, all dressed in Hispanic clothes. The next scene depicted a senior missionary couple teaching English to a group of Hawaiian children dressed in muumuus and leis. Finally, two Caucasian male missionaries were teaching a Latino family about Jesus. The number seemed to suggest that the modern-day pioneer is an American missionary who brings the non-discriminatory message of Christ’s love to all secular nations, most of which are third world.

In 1960, almost 90 percent of all Mormons lived in the continental United States, predominantly in Utah and the Great Basin region of the Rocky Mountains. By 1997, the time of the Sesquicentennial Spectacular, less than half of all Mormons worldwide resided in the United States, with less than 16 percent of Church members in Utah. [35] The worldwide reality of the Church stands in sharp contrast to the American vision being propagated by official Church representation.

The message of the Sesquicentennial Spectacular, Faith in Every Footstep, recognizes the global reality of the Church with its performed suggestion that individuals who join the Church are joining a community of believers who are bound by Christian ethics and specific doctrines, no matter their race or citizenship. However, when this spiritual migration is being performed in front of a giant cutout of the Salt Lake City temple, in a stadium sitting in the middle of Utah Valley, surrounded by the Rocky Mountains, it becomes difficult to divorce joining the Church from joining its geographical center. The weight of the reality of the space may have been too much for the pageant to overcome.

The Sesquicentennial Spectacular in particular preaches the unifying message of the mission of the Church through the interplay of the spiritual and secular, global and local, and entertainment and efficacy binaries. While each of these sites of tension shows the complex nature of representation, in each case, the pageant eventually reaffirms an image of the Mormon community that is chiefly American in its style.

Notes

[1] All quotes from the production come from a personal video recording of the KBYU broadcast of the Spectacular. I will not cite the quotes beyond this note.

[2] Jeff McClellan, “Mormon Pioneers Settle at BYU,” BYU Today, Fall 1997; http://

[3] Victor Witter Turner, The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure (Chicago: Aldine Publishing, 1969), 95.

[4] Schechner actually proposes eight distinct yet overlapping situations of performance: (1) in everyday life, (2) in the arts, (3) in sports and popular entertainment, (4) in business, (5) in technology, (6) in sex, (7) in ritual—sacred and secular, and (8) in play. Richard Schechner, Performance Studies: An Introduction (New York: Routledge, 2006), 31.

[5] Schechner’s essay “What is Performance Studies Anyway?” reviews, from his point of view, the development of the field. He suggests that Performance Studies itself is “inherently ‘in between’ and therefore cannot be pinned down or located exactly. Richard Schechner, “What is Performance Studies Anyway,” in The Ends of Performance, ed. Peggy Phelan and Jill Lane (New York: New York University Press, 1998), 360.

[6] Davis Bitton, ed., The Ritualization of Mormon History and Other Essays (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994), 173.

[7] Rodger Sorensen, telephone interview with the author, January 29, 2007.

[8] McHale, “Witnessing for Christ,” 36.

[9] McHale, “Witnessing for Christ,” 40.

[10] Roy A. Rappaport, Ecology, Meaning and Religion (Richmond, CA: North Atlantic Books, 1979), 175–178.

[11] Terryl L. Givens, People of Paradox: A History of Mormon Culture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 268.

[12] The other pageants are the Arizona Easter Pageant, Jesus the Christ, which is the largest outdoor Easter pageant in the world; the Mormon Miracle Pageant in Manti, Utah; the Castle Valley Pageant, which reenacts the settling of a pioneer town; the Oakland Temple Pageant, which celebrates key points in religious history from the life of Christ to the Restoration; and the Nauvoo Pageant, a Church history musical that includes short historical vignettes that are staged in Old Nauvoo throughout the day.

[13] David Glassberg, American Historical Pageantry: The Uses of Tradition in the Early Twentieth Century (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990), 289.

[14] Glassberg, American Historical Pageantry, 4.

[15] Ronald Grimes, Rite out of Place: Ritual, Media, and the Arts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 135.

[16] George A. Smith, in Journal of Discourses (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1974), 2:215.

[17] Victor Witter Turner, From Ritual to Theatre: The Human Seriousness of Play (New York: Performing Arts Journal Publications, 1982), 48.

[18] For works that deal specifically with participants in Mormon pageants, see Gerald Argentsinger, “The Hill Cumorah Pageant: A Historical Perspective,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 13, vols. 1–2 (2004): 58–69; Ellen E. McHale, “‘Witnessing for Christ’: The Hill Cumorah Pageant of Palmyra, New York,” Western Folklore 44, vol. 1 (1985): 34-40; and Heidi D. Lewis, “‘Speaking out the Dust’: Religious Reenactments with the Specific Iconic Identity of Place” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 2006).

[19] Schechner differentiates between transformation (literally changing who a person is) and transportation (being moved, or touched by a performance, then returning to how things were before). Schechner argues that most performance is transporting, but rarely does a real transformation occur (Performance Studies: An Introduction, 72).

[20] David Levinson, ed., Encyclopedia of World Cultures (Boston: G.K. Hall, 1991), 1:246–247.

[21] Susan Bennett, Theatre Audiences: A Theory of Production and Reception (London: Routledge, 1997), 2.

[22] Megan Sanborn Jones, “(Re)living the Pioneer Past: Mormon Youth Handcart Trek Reenactments,” Theatre Topics 16, no. 2 (2006): 115.

[23] Joseph Roach, “History, Memory, Necrophilia,” in The Ends of Performance, ed. Peggy Phelan and Jill Lane (New York: New York University Press, 1998), 23.

[24] Wallace Stegner, The Gathering of Zion: The Story of the Mormon Trail (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964), 2.

[25] Michael L. Raposa, “Ritual Inquiry: The Pragmatic Logic of Religious Practice,” in Thinking Through Ritual, ed. Kevin Schilbrack (New York: Routledge, 2004), 21.

[26] Grimes, Rite Out of Place, 135.

[27] Schechner, Performance Studies, 82–83.

[28] Frederick N. Bohrer, Orientalism and Visual Culture: Imagining Mesopotamia in Nineteenth-Century Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 11.

[29] While the grouping of these cultures may seem arbitrary to those outside LDS culture, the group’s original name, the Lamanite Generation, clues LDS audiences into their unified heritage. Each of these groups is considered by Mormons to be the descendants of the original settlers in the Promised Land (the Americas and the Polynesian Islands), as described in the Book of Mormon.

[30] Schechner, Performance Studies, 80.

[31] “2007 Family Cast Information,” Nauvoo Pageant website, accessed January 15, 2007, http://

[32] Gordon B., Hinckley, Thomas S. Monson, and James E. Faust. “Faith in Every Footstep: The Epic Pioneer Journey (Video Presentation),” Ensign. April 1997, 64.

[33] Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 1983), 7.

[34] Harold Bloom, The American Religion: The Emergence of the Post-Christian Nation (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992), 93–94). Bloom’s opinion is mirrored by statistics that show a more than 57 percent mean percentage increase per decade in conversions. Following a projection that sets a growth rate below the average at 50 percent, by the year 2080, there will be more than 265 million Mormons. Gary Shepherd and Gordon Shepherd, Mormon Passage: A Missionary Chronicle (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 11.

[35] Shepherd and Shepherd, Mormon Passage, 11.