The Eternal Nature of the Family in Egyptian Beliefs

Michael D. Rhodes

Michael D. Rhodes is a professor emeritus of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University.

Some of the most powerful rituals are those performed within the home. Latter-day Saint family life is replete with ritualized events from family home evenings to the annual father’s blessings prior to school. Even rituals that we think may be unique, such as the sealing rites in the temple, may be found elsewhere in family settings. As Michael Rhodes demonstrates, the Egyptian ritual traditions from writing letters to the dead to postures of the dead as clay figurines may have been instituted to perpetuate the family bonds into the afterlife, a concept readily understandable to the Latter-day Saint.

An aspect of ancient Egyptian culture and religious beliefs that strikes a resonant chord with Latter-day Saints is the great importance they placed on the family. For the Egyptians, their relationship with spouse, siblings, parents, children, ancestors, and descendants was of greatest consequence. One significant result of this was that unlike most of the other civilizations of the ancient Near East, the Egyptians never practiced the killing of unwanted children by exposure.[1] In the Book of Abraham we also see this same strong sense of family emphasized. Abraham indicates that he “sought for the blessings of the fathers” and “became a rightful heir, a High Priest, holding the right belonging to the fathers. It was conferred upon me from the fathers; it came down from the fathers, from the beginning of time” (Abraham 1:2–3).

Egyptians had the sacred responsibility to ensure a proper burial for deceased family members and to provide for their subsequent funerary cult.[2] Especially noteworthy, however, was their conviction that the family structure would continue after death. In this paper I will look at the inscriptional, artistic, and literary evidence for this belief among the ancient Egyptians. The literary evidence falls into two categories: letters to the dead and religious texts, including the Book of the Dead and the Coffin Texts. These religious texts, which are mostly found in the coffins of deceased Egyptians, contain, among other things, rituals that the Egyptians performed in the temple while they were still alive in anticipation of performing those same rituals after death in order to obtain a place with the gods in the hereafter.[3]

Inscriptions

The earliest inscriptional evidence for the belief in the continuation of the family after death is found in the Old Kingdom tomb of Djau at Deir el Gebrâwi. Djau lived during the reign of the 6th Dynasty king Pepy II, who ruled from 2246 to 2152 BCE. The relevant portion of the inscription is as follows: “But I caused myself to be buried in a single tomb with this Djau so that I might be with him in one place. Not, however, because I did not have an authorization to build two tombs, rather I made this so that I might see this Djau every day, and so that I might be with him in one place.”[4] Even though he had the authorization (from the king) as well as the resources to build his own tomb, Djau here explains that he was buried with his father (also named Djau), because he wanted to be with him after death.

Statues and Tomb Paintings

Fig. 1. Statue of a husband and wife, circa 2450 BCE

Fig. 1. Statue of a husband and wife, circa 2450 BCE

Funerary statues and tomb paintings from all periods of Egyptian history also portray the closeness of the family relationship among the Egyptians and highlight the belief that this relationship would continue in the next life. Husband and wife, parents and children, are depicted together in the hereafter in familiar and intimate poses, often embracing each other, illustrating the strong bonds that held a family together. These statues and tomb paintings were intended to both depict and create the ideal afterlife. They were thus an eloquent expression of exactly what the owner wanted the afterlife to be like. A good example is a statue of a man and wife from the Old Kingdom found at Gîza shown in figure 1. It dates from the Fifth Dynasty around 2450 BCE.[5] The wife stands next to her husband with her right arm around his waist and her left arm gently touching his left arm. Both have a slight smile and seem to radiate the joy they find in each other’s presence. The entire scene presents a touching picture of domestic love and intimacy that reaches beyond this mortal life.

Another Old Kingdom example is that of Memisabu and his wife (shown in figure 2), also found at Gîza. This statue is also from the Fifth (or possibly early Sixth) Dynasty and dates to around 2350 BCE.[6] As in the previous statue, Memisabu’s wife, who is much shorter than he is, has her right arm around his waist. But here Memisabu has his left arm around the shoulder of his wife with his hand resting tenderly on her left breast.

Fig. 2. Memisabu and his wife, circa 2350 BCE.

Fig. 2. Memisabu and his wife, circa 2350 BCE.

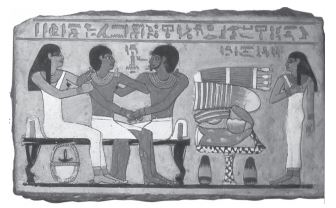

An example from the Middle Kingdom is found on the tomb Stela of Amenemhat, found in Asasif in Western Thebes shown in figure 3.[7] It is from the late Eleventh or early Twelfth Dynasty and dates to around 1980 BCE. Amenemhat is shown sitting between his father and mother, who lovingly embrace him, while his wife stands to the right in front of an altar covered with offerings.

Fig. 3. Amenemhat with his parents and wife, circa 1980 BCE.

Fig. 3. Amenemhat with his parents and wife, circa 1980 BCE.

Tomb Inscriptions

The written texts accompanying some tomb paintings also express the Egyptians’ great longing for being reunited with their family. The following are some examples.

In the Eighteenth Dynasty tomb of Djehuti, Djehuti says to the god Amon: “May you grant that I go down to the Beautiful West and join my father and mother.”[8]

In the Nineteenth Dynasty tomb of Pedju, the wish is expressed: “May he join his father and mother. May the Lords of the God’s Domain say to him, ‘Welcome, welcome in peace.’”[9]

In the Eighteenth Dynasty tomb of Renni, the text states: “See now, he belongs to his brothers and sisters and is with his brothers and sisters.”[10]

In the Eighteenth Dynasty tomb of Neferhotep, a team of oxen draws a sled with his coffin on it. The animals are addressed with the following words: “May you say: ‘O cattle, pull with a willing heart, without being discouraged. . . . [Repeated four times.] Neferhotep, justified, is with you. Pull him to the west of Thebes, the district of the righteous ones. May his brothers from the <time> of the god and his forefathers join him.’”[11]

Neferhotep then says: “May I see my father. May he give me his hands and may he say to me, ‘Welcome.’ May my mother embrace me and say to me, ‘How fortunate is that which has happened to you.’”[12]

Letters to the Dead

Another practice that indicates the Egyptians’ strong belief in the continuance of the family in the hereafter is the writing of letters to deceased family members. These letters were written by living family members—husbands, wives, sons, daughters, brothers, and sisters—and left at the tomb or in the tomb chapel near the tomb of the deceased. The contents of the letters included greetings, hopes that the departed was well, pleas for the departed to intercede on the behalf of the living in problems they were facing, and requests that the departed bring people who had committed some offense against the living to justice in the court of judgment in the afterlife.

One such letter was written on the back of Tenth Dynasty stela from a tomb chapel in Nag’ ed-Deir. In this letter Merirtifi writes to his wife, Nebitef: “A message from Merirtifi to Nebitef: How are you? Is the West taking care (of you) [as you] desire? Look, I am your beloved on earth, (so) fight for me, intercede for my name!”[13] Later in the same letter he asks her to cure him of an illness in his limbs and pleads with her to appear to him to confirm to him that she will help him.[14]

In another letter on an ostracon dating from the Twenty-First Dynasty, Butehamon writes to his wife Ikhtay: “What is your condition? How are you? . . . If I can be heard where you are, tell the lords of eternity to let your brother (i.e., husband) come to [you]”[15]—a poignant plea to be reunited with his wife in the hereafter.

These letters to the dead make it clear that the living felt a strong bond with the dead and that they expected to eventually join them in the afterlife and continue in the family relationships they enjoyed while on earth

Book of the Dead

Fig. 4. Vignettte showing Ani and his wife Tutu, circa 1250 BCE.

Fig. 4. Vignettte showing Ani and his wife Tutu, circa 1250 BCE.

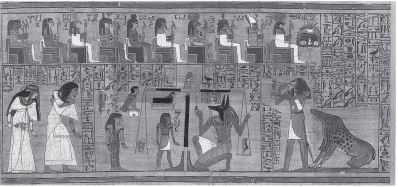

A common feature in the Book of the Dead is the depiction of the husband and wife together in the afterlife. A good example is the vignette accompanying chapter 30B of the Book of the Dead belonging to the Royal Scribe, Ani, who lived during the Nineteenth Dynasty (shown in figure 4). This papyrus dates to around 1250 BCE. In this vignette Ani and his wife Tutu watch as his heart is weighed on scales against an ostrich feather representing ma’at, truth or justice.

Anubis checks the accuracy of the balance, while Thoth stands by recording the results. The monster Ammit, who has the head of a crocodile, the fore-body of a leopard, and the rear-body of a hippopotamus, waits to gobble down any heart that does not balance with truth. In front of the scales is Ani’s human-headed Ba. There too stand Meskehenet, the goddesses of birth, and Renenet and Shay, the goddess and god of destiny. Twelve gods and goddesses holding was-scepters are enthroned behind a heaped offering table as witnesses to the judgment.[16] After successfully passing through this judgment, Ani and his wife will be introduced into the presence of Osiris, the god of the Dead to live forever with the gods and, according to Egyptian beliefs, to become gods themselves.

The Book of the Dead also contains a couple of written references to the hope of being reunited with one’s family in the hereafter. In chapter 52 it reads: “My family, consisting of my father and my mother, has been given to me.”[17] In chapter 110 the dead person exclaims: “O Qenqenet, I have come in to you. I have seen my father and recognized my mother.”[18]

Coffin Texts

Probably the most detailed description of the Egyptian hope of being reunited with the family after death comes from the Coffin Texts. Coffin Text spells 131–46 deal with this theme. They can be roughly divided into two groups based on their content. Spells 131–35 describe the obtaining of a legal document with an official seal from the gods that authorizes the reuniting of the dead person with his or her family. In spells 136–46 the dead person attempts to bring about this reuniting by the use of prayer, force, or threats.[19]

Let us consider some passages from this group of spells.[20] Coffin Text spell 131 is an example of the first group having the form of a legal royal decree.

The sealing of a decree concerning the family (regarding) the giving of a man’s family [to him] in the hereafter.

The Great Horus, Lord of the Field of Rushes.[21]

Geb, Chief of the Gods, has decreed that my family, my children, my brothers, my father, my mother, my servants, and each of my fellow-citizens be given to me, and that they be protected from the (evil) deeds of Seth, and from the census of the Great Isis, on the shoulders of Osiris, Lord of the West.

Geb, Chief of the Gods, has said that my family, my children, my brothers, my father, my mother, all my servants, and each of my fellow-citizens be released to me immediately, and be protected from any god or goddess, from any glorified man or woman, and from any dead man or woman.[22]

In this spell the dead person is promised that not only his family but even his servants and fellow citizens will be reunited with him in the hereafter, and they will be protected from anyone who would do them harm. This spell is modeled on royal decrees of the period, with the god Geb taking the place of the earthly king.

In spell 134, Thoth announces the issuance of the decree reuniting the dead person with his family. “The sealing of a decree concerning this family of mine. . . . Thoth said to me: ‘Let a decree be sealed for you.’ Thus he said. How good is this decree, this good document of the Lady of Appearances who gives (me) my family.”[23]

Spell 136 also refers to the reuniting of the dead person with not only his immediate family but also his relatives and associates. “Reassembling the family in the hereafter.[24] May my human association of which I have spoken be given to me. May my family, my children, my brothers and sisters be given to me. So also their relatives and <my> associates wherever they may be.”[25]

Spell 141 mentions the dead persons searching for his family in heaven, in earth, and in the waters. “N seeks out his family in heaven, on the earth, and in the waters.”[26]

There is an interesting similarity here between this passage and one in the hypocephalus of Shishaq found in Facsimile 2 of the book of Abraham. In lines 9–10 Osiris is addressed: “O Mighty God, Lord of heaven and earth, of the hereafter, and of his great waters.”[27] The dead person is thus searching for his family throughout the entire realm over which Osiris rules. A similar passage is found in spell 146 below.

The ending of spell 143 gives its purpose, which is “the assembling of the family of N for him in the hereafter, and the giving to him of his family in the hereafter.”[28]

Spell 146 also describes the dead person’s search for his family, so that they can be reunited with him in the hereafter, and his joy at this reuniting.

The assembling of a man’s family in the hereafter.

O Re, O Atum, O Geb, O Nut! Behold, this N. He is going down to the sky, he is going down to the earth, he is going down to the water. He is seeking out his father, he is seeking out his mother, he is seeking out his children and his brothers and sisters, he is seeking out his subordinates who used to make things for this N on the earth. He is seeking his concubine whom he knew, because this N is indeed he[29] whom the Great One created. Let there be assembled for this N his family and his concubines, who seized the heart of this N (with joy). Let (also) his subordinates be assembled for N, who did things for this N on earth. [30]

But if his family is assembled for this N, which is in the sky, in the earth, in the hereafter, in the primeval waters,[31] in Place of Mourning,[32] in the inundation, in the flood, in the Temple of the Greatest of the Bulls, in Busiris, in Mendes, in Heliopolis, in Letopolis, in Pe of the Great One, in Babylon, and in Abydos, then . . .[33]

Have you been given a decree for this family of yours? This N has gone down rejoicing with his heart joyful, for this family of his has been given to him.[34]

The assembling for him in the hereafter of family, father, mother, friends, companions, children, wives, concubines, subordinates, servants, and everything which a man ought to have.[35]

There is one other passage in the Coffin Texts not belonging to this group of spells that mentions the reuniting of the dead with his family: spell 173. “My father and mother, my brothers and sisters, my fellow citizens, and my entire family have been given to me.”[36]

Summary

Surviving inscriptional and artistic evidence from ancient Egypt all points to a very strong sense of family in this life and the firm belief that this family structure, including even servants, would remain intact after death. The authority for this reuniting is modeled on Egyptian royal documents, which included an official seal, with a god taking the place of the king as the authorizing agent. The Egyptians believed that they would not only be reunited with their family members in the next world, but also with their friends and associates. The relationship between husband and wife and parents and children is portrayed with great tenderness, and the joy at seeing each other again is emphasized. The Egyptians firmly believed that life after death for those who live a moral, righteous life would be a continuation of all that was good in this life, including especially the family relationships that were of such great importance to them in this life.

Abbreviations

CT = Adriaan de Buck, The Egyptian Coffin Texts, 7 vols. (Chicago: Oriental Institute, 1935–61).

Wb = Adolf Erman and Hermann Grapow, Wörterbuch der Ägyptischen Sprache, 5 vols. (Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs, 1926).

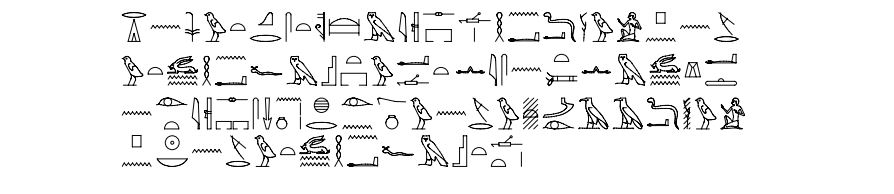

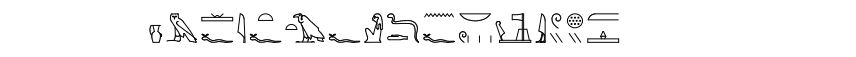

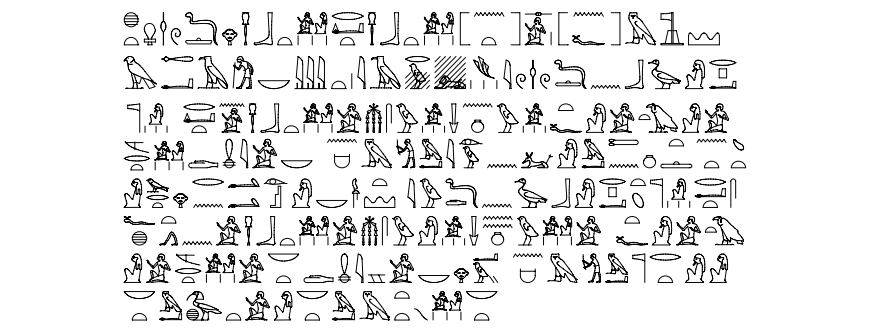

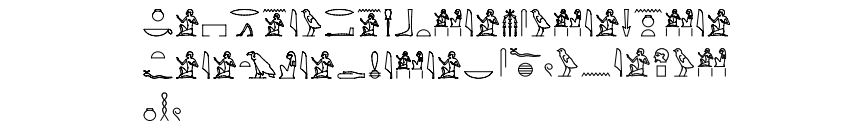

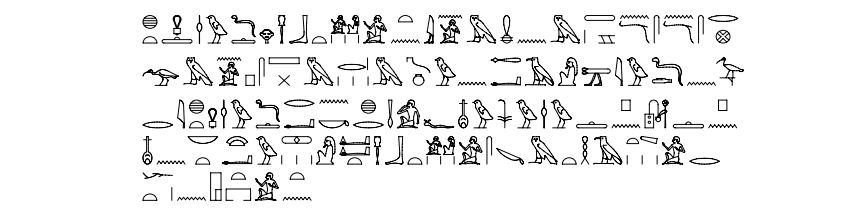

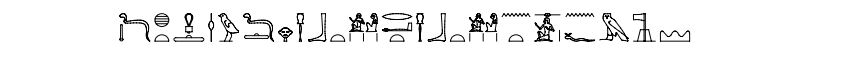

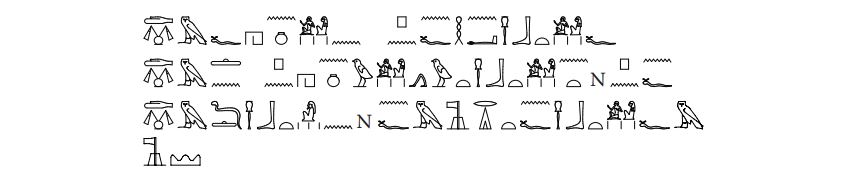

Appendix: Hieroglyphic Texts

Tomb Inscription of Djau[37]

rdi.n(=i) swt qrz.t(i=i) m iz wo eno Jaw pn n mrw.t wnn(=i) eno=f m s.t wo.t. n is n tm wnn xr-o n(=i) n ir.t iz.wy snw ur ir.n(=i) nw n mrw.t maa(=i) Jow pn ro nb, n mrw.t wnn(=i) eno=f m s.t wo.t.

But I caused myself to be buried in a single tomb with this Djau so that I might be with him in one place. Not, however,[38] because I did not have an authorization to build two tombs, rather I made this so that I might see this Djau every day, and so that I might be with him in one place.

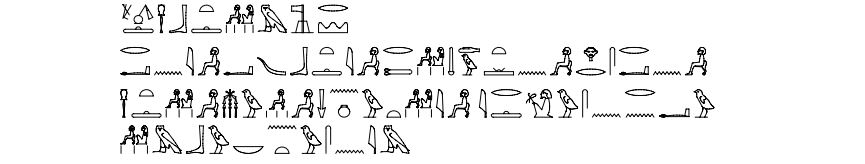

Prayer to Amon in the Tomb of Djehuti[39]

di=k h(a)=i r imnt.t nfr(.t) xnm=i it=i mw.t(=i)

May you grant that I go down to the Beautiful West and join my father and mother.

Tomb of Pedju[40]

xnm=f it=f mw.t=f. jd n=f nb.w xr.t-ncr, ii.wy zp 2 m etp.

May he join his father and mother. May the Lords of the God’s Domain say to him, “Welcome, welcome in peace.”

Tomb of Renni[41]

m=cn r=f sw n snw.w=f, m snw.w=f.

See now, he belongs to his brothers and sisters and is with his brothers and sisters.

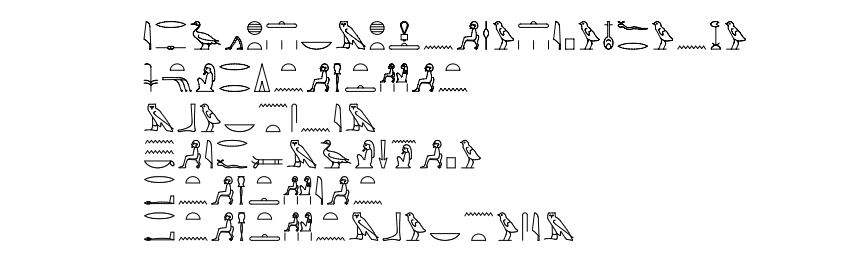

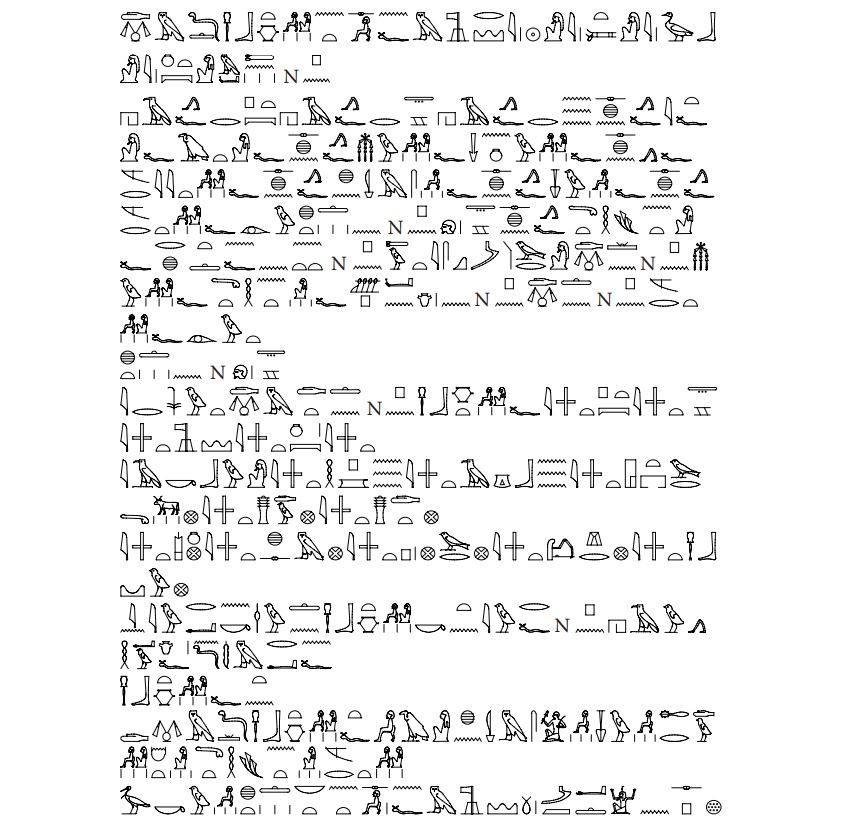

CT 131: II, 151–52

utm wj er ab.t rdi.t ab.t [n.t] s [n=f] xr.t-ncr. Er oa, nb su.t-iarw.w. iw wj.n Gb, rpo.t ncr.w rdi.t(w) n=i ab.t=i, msw.w=i, snw.w=i, it=i, mw.t=i, mr.wt, dmi nb, nem m-a irw n Stx, m-o cnw.t n.t Is.t wr.t, er rmn.yw Wsir, nb imnt.t. iw jd.n Gb, rpo.t ncr.w rdit sfu.t n=i ab.t=i, msw.w=i, snw.w=i, it=i, mw.t=i, mr.wt=i nb.t, dmi nb er o.wy, nem m-o ntr nb ncr.t nb(.t), m-o au nb au.t nb.t, m-o m(w)t nb m(w)t.t nb(.t).

Sealing of a decree concerning the family (regarding) the giving of a man's family [to him] in the hereafter.

The Great Horus, Lord of the Field of Rushes.[42]

Geb, Chief of the Gods, has decreed that my family, my children, my brothers, my father, my mother, my servants, and each of my fellow-citizens be given to me, and that they be protected from the (evil) deeds of Seth, and from the census of the Great Isis, on the shoulders of Osiris, Lord of the West.

Geb, Chief of the Gods, has said that my family, my children, my brothers, my father, my mother, all my servants, and each of my fellow-citizens be released to me immediately, and be protected from any god or goddess, from any glorified man or woman, and from any dead man or woman.

CT Spell 132: II, 154–55

ink pr.n=i, iw rdi n=i ab.t=i, msw.w=i, sn.w=i, sn.wt=i, it=i, mw.t=i, dmi.w=i nb. sfu.w n=i tp.w nwe.

I have come forth (from the dead). My family, my children, my brothers and sisters, my father, my mother, and all my fellow-citizens have been given to me. The prisoners have been released to me.

CT Spell 133: II, 158

rdi n=i ab.t=i nb mdw.t.n=i er=s.

My entire family, concerning which I spoke, has been given me.

CT Spell 134: II, 159

utm wj er ab.t=i tn

ii.n=i m min m iw-nsrsr, gm n=i psv m ra.w m nw n oa ic.

iw jd.n Jewty r=i, utm wj rdi n=k. ur=f. nfr.w(y) sw wj pn, sv pn nfr n Nb.t uo.w, dd.t ab.t=i svm.t ae.wt=i r-ut n ew.t=i tn.

Today I have come from the Island of Fire, and I have found a share from the mouths of those great ones who partake.

Thoth said to me: “Let a decree be sealed for you.” Thus he said. How good is this decree, this good document of the Lady of Appearances who gives (me) my family, and who governs my lands according to the land registry of this administrative district of mine.

CT Spell 135: II, 160e

dd-mdw utm wj er ab.t, rdi.t ab.t n.t s n=f m xr.t-ncr.

A recitation for sealing a decree concerning the family, to give a man’s family to him in the hereafter.

CT Spell 136: II, 160f, 164c–g

dmj ab.t m xr.t-ncr.

rdi n=i ob.t=i rmc mdw.t-n=i er=s. rdi n=i ab.t=i ms.w=i snw.t=i, ir.w=sn rmn.w(ti) m bw nb nt.w=sn im.

Reassembling the family in the hereafter.

May my human association of which I have spoken be given to me. May my family, my children, my brothers and sisters be given to me. So also their relatives and <my> associates wherever they may be.

CT Spell 137: II, 165f–g, 166c–d, 166i, 167c

ir sa u.t nb m utm n=i wj.w ipw nfr.w n uA.w n swt r rdi.t n=i ab.t=i tn m bw nb ntw=sn im.

nnk ir=f tm sa(=i pw) sn=i pw.

rdi.t(w) n=i ab.t tn.

rdi.t(w) n=i ab.t tn m bw nb nt.w=s im.

If anything be withheld concerning the sealing for me of these good decrees . . .[43] in order that this family of mine might be given to me wherever they may be.

Now to me belongs everything, this son of mine and this brother of mine.

May this family be given to me.

May this family be given to me wherever it is.

CT Spell 141: 174c–d

sun N pn ab.t=f m p.t m ta m mw.

N seeks out his family in heaven, on the earth, and in the waters.

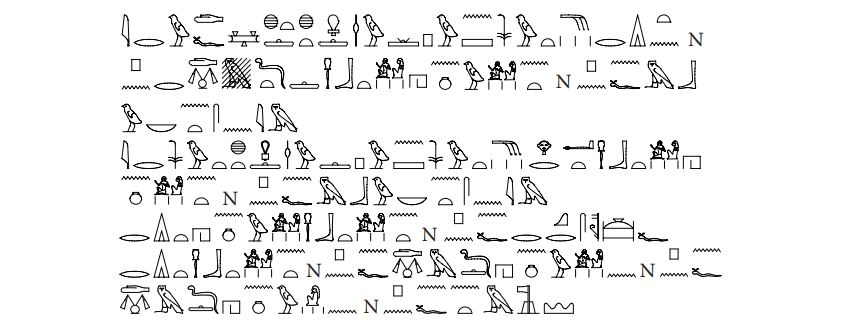

CT Spell 142: II, 174f–g, j-k, 175c–d, g–h, j

ir wdf u.t utm wj pw n vsw.wt r di.t n N pn, r dmj ab.t hnw n.t N pn n=f m bw nb nt(y)=sn im.

ir swt utm wj pw n vsw.wt er di.t ab.t hnw n.t N pn n=f m bw nb nt(y)=sn im.

rdi.t hnw ab.t n.t N pn n=f r qrs=f.

rdi.t ab.t n.t N pn n=f, dmj hnw n N pn n=f.

dmj hnw n N pn n=f nt(y) m xr.t-ncr.

If anything delay the sealing of this decree of ——,[44] to give to N <his family>, to assemble the family and associates of N to him wherever they are, . . .

But if this decree of ——,[45] is sealed concerning the giving of the family and associates of N to him wherever they are, . . .

The giving of the associates and family of N to him at his burial.

The giving of the family of N to him, and the assembling of the associates of N to him.

Assembling the associates of N to him who are in the hereafter.

CT Spell 143: II, 176a, i–j, 177i–j

dmj=f hnw n N pn n=f eno ab.t=f.

dmj.n N pn hnw, iw.t ab.t N pn n=f.

dmj ab.t n N n=f m xr.t-ncr, rdi.t n=f ab.t=f m xr.t-ncr.

May he assemble the associates of N for him together with his family.

N has assembled associates so that his family of N might come to him.

The assembling of the family of N for him in the hereafter, and the giving to him of his family in the hereafter.

CT Spell 144: II, 177k

ra n dmj ab.t

A saying for assembling a family.

CT Spell 146: II, 180a–84b, 195a–96c, 201a–c, 205b–d

dmj ab.t n.t s n=f m xr.t-ncr.

i Ro, i Itm, i Gb, i Nw.t. m=cn N pn ha=f r p.t, ha=f r ta, haf=f r mw. sun=f it=f, sun=f msw.w=f snw.w=f, sun=f mry.t=f, sun=f unms.w=f, sun=f smaw.w=f, sun=f mr.t=f ir.w u.t n N pn tp-ta. sun=f mt-en.t ru.t.n=f, n-nt.t N pn cwt is qma Wr. dmj n N pn msw.w=f, mt-en.wt=f, vsp.n ib n N pn. dmj n N pn mr.t=f irw.t u.t n N tp-ta..

ir swt dmd.t(w) n N pn ab.t=f imi.t p.t, imi.t ta, imi.t xr.t-ncr, imi.t nw, imi.t iakbw, imi.t e(o)py, imi.t agb, imi.t Ew.t-wr-ka.w, imi.t Jdw, imit, Dd.t, imi.t Iwnw, imi.t Um, imi.t P-Wr, imi.t Xry-oea, imi.t Abjw.

in iw rdi n=k wj.n ab.t=k tn. iw r=f N pn haw, eow ib=f njm, rdi n=f ab.t=f tn.

dmj ab.t, it, mw.t, unmws.w, smaw.w, xrdw.w, em.wt, mt-hn.wt, mr.t, bakw.w, u.t nb.t n.t z n=f m xr.t-ncr.

The assembling of a man’s family in the hereafter.

O Re, O Atum, O Geb, O Nut! Behold, this N. He is going down to the sky, he is going down to the earth, he is going down to the water. He is seeking out his father, he is seeking out his mother, he is seeking out his children and his brothers and sisters, he is seeking out his subordinates who used to make things for this N on the earth. He is seeking his concubine whom he knew, because this N is indeed he[46] whom the Great One created. Let there be assembled for this N his family and his concubines, who seized the heart of this N (with joy). Let (also) his subordinates be assembled for N, who did things for this N on earth.

But if his family is assembled for this N, which is in the sky, in the earth, in the hereafter, in the primeval waters, in Place of Mourning,[47] in the inundation, in the flood, in the Temple of the Greatest of the Bulls, in Busiris, in Mendes, in Heliopolis, in Letopolis, in Pe of the Great One, in Babylon, and in Abydos, then . . .[48]

Have you been given a decree for this family of yours? This N has gone down rejoicing with his heart joyful, for this family of his has been given to him.

The assembling for him in the hereafter of family, father, mother, friends, companions, children, wives, concubines, subordinates, servants, and everything which a man ought to have.

CT Spell 173: III, 52

rdi n=i it=i mw.t=i snw.wt=i dmi.w=i ab.t=i mi qd.

My father and mother, my brothers and sisters, my fellow citizens, and my entire family have been given to me.

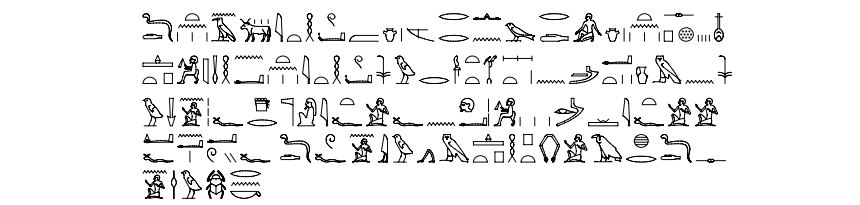

Book of the Dead Chapter 52, 5[49]

iw rdi.t(w) n=i ab.t=i n.t it=i mw.t=i

My family, consisting of my father and my mother, has been given to me.

Book of the Dead Chapter 110[50]

Qnqn.t, ii.n=i im=t. ma.n=i it=i. ip.n=i mw.t=i.

O Qenqenet, I have come in to you. I have seen my father and recognized my mother.

Tomb of Neferhotep[51]

The 18th Dynasty Theban tomb of Neferhotep dates from the time of Ay (1323–1319 BCE).[52]

jd=tn, na ka.w, ite m ib mrr, nn wrd ib=tn. sp 4. Nfr-etp, mao-urw, eno=tn. ite sw r imnt.t Was.t, spa.t n maoty(.w). xnm.n sw sn.w=f jr <rk> ncr it=f n tp-oy.w.

ma(=i) it=i. di=f n(=i) o.wy=f. jd.w=f n=i, ii.w m etp. ept (w)i mw.t(=i) ur jd=s n=i, w(a)j-wy upr n=k.

May you say: “O cattle, pull with a willing heart, without being discouraged . . . . [Repeated four times.] Neferhotep, justified, is with you. Pull him to the west of Thebes, the district of the righteous ones. May his brothers from the <time> of the god and his forefathers join him.

“May I see my father. May he give me his hands and may he say to me, ‘Welcome.’ May my mother embrace me and say to me, ‘How fortunate is that which has happened to you.’”

Notes

[1] Wolfgang Helck and Eberhard Otto, Lexikon der Ägyptologie, 7 vols. (Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, 1975–92), 2:101.

[2] . Helck and Otto, Lexikon der Ägyptologie, 2:101.

[3] . Claas J. Bleeker, “Initiation in Ancient Egypt,” in Initiation, ed. C. J. Bleeker (Leiden: Brill, 1965) 49–58; Jan Assmann, “Death and Initiation in the Funerary Religion of Ancient Egypt,” in Religion and Philosophy in Ancient Egypt (New Haven: Yale Egyptological Seminar, 1989), 135–59; John Gee, “Prophets, Initiation and the Egyptian Temple,” Journal for the Society for the Study of Egyptian Antiquities 31(2004): 97–107.

[4] . Kurt Sethe, Urkunden des Alten Reichs (Leipzig: Hinrichs’sche Buchhandlung, 1932–33), 146–47; translation by author.

[5] . Painted limestone; 56 cm in height; Vienna, Kunst-historisches Museum, ÄS 7444.

[6] . Limestone; 62 cm in height; New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 48.111.

[7] . Tomb of Amenemhat (R4); painted limestone; 50 x 30 cm; Cairo, Egyptian Museum, JE 45626.

[8] . Kurt Sethe, Urkunden der 18. Dynastie (Leipzig: Hinrichs’sche Buchhandlung, 1906–9), 445. Erich Lüddeckens, Untersuchungen über religiösen Gehalt, Sprache und Form der ägyptischen Totenklage (Berlin, Reichsverlagsamt, 1943), 147.

[9] . Erich Lüddeckens, Untersuchungen über religiösen, 146.

[10] . Erich Lüddeckens, Untersuchungen über religiösen, 40.

[11] . Norman De Garis Davies, The Tomb of Nefer-hotep at Thebes (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1933), pl. LVIII–LIX, c, and p. 67; author’s translation.

[12] . De Garis Davies, Tomb of Nefer-hotep at Thebes, pl. LVIII–LIX, c, and p. 67; author’s translation.

[13] . R. B. Parkinson, Voices from Ancient Egypt: An Anthology of Middle Kingdom Writings (Normon, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991), 142.

[14] . Parkinson, Voices from Ancient Egypt, 142.

[15] . Edmund S. Meltzer, ed., Edward F. Wente, trans. (Atlanta: Scholars Press, Letters from Ancient Egypt, 1990) 218.

[16] . British Museum papyrus BM10470 belonging to the Royal Scribe, Accounting Scribe for Divine Offerings of All the Gods, Overseer of the Granaries of the Lords of Tawer, Ani.

[17] . Richard Lepsius, Das Todtenbuch der Ägypter nach dem Hieroglyphischen Papyrus in Turin (Leipzig: Georg Wigand, 1842), 52, 5.

[18] . Edouard Naville, Das Aegyptische Totenbuch der XVIII. bis XX. Dynastie, vol. 2 (Berlin: A. Ascher, 1886), 256.

[19] . Herman Kees, Totenglauben und Jenseitsvorstellungen der alten Ägypter (Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs`sche Buchhandlung, 1926), 308–9.

[20] . All the relevant passages of these spells with hieroglyphic text and translation can be found in the appendix. All translations are by the author.

[21] . Written in a serekh. This is the Horus name of the ruler under whose authority the decree is made—in this case Geb. This is the standard heading for a royal decree, cf. Hans Goedicke, Königliche Dokumente aus dem alten Reich (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1967), passim.

[22] . CT II, 151–52.

[23] . CT II, 159.

[24] . CT II, 160f.

[25] . CT II, 164c–g.

[26] . CT II, 174c–d.

[27] . Michael D. Rhodes, “A Translation and Commentary of the Joseph Smith Hypocephalus,” Brigham Young University Studies 17 (Spring 1977): 265. The present translation differs slightly from that given in the original publication.

[28] . CT II, 177i–j.

[29] . The text has cwt “you” (2 per. m.s.).

[30] . CT II, 180a–184b.

[31] As mentioned above in connection with spell 141, the places searched: heaven, the earth, the hereafter, and the primeval waters, are those regions over which Osiris rules according to a passage in the Shishaq hypocephalus.

[32] iakbw - a place in the hereafter, Wb 1:34, 16.

[33] CT II, 195a–196c. The text then describes various good things that will be done for the gods.

[34] CT II, 201a–c.

[35] CT II, 205b–d.

[36] CT III, 52d.

[37] . Sethe, Urkunden des Alten Reiches, 146–47.

[38] . For n is before n see Elmar Edel, Altägyptische Grammatik, 2 vols. (Rome: Pontificium Institutum Biblicum, 1955, 1964), 2:415.

[39] . Sethe, Urkunden der 18. Dynastie, 445. Lüddeckens, Untersuchungen über religiösen, 147.

[40] . Lüddeckens, Untersuchungen über religiösen, 146.

[41] . Lüddeckens, Untersuchungen über religiösen, 40.

[42] . Written in a serekh. This is the Horus name of the ruler under whose authority the decree is made, in this case Geb. This is the standard heading for a royal decree (cf. Goedicke, Königliche Dokumente aus dem alten).

[43] . I cannot make any sense of nua.w n swt. Faulkner also could not translate it; Raymond O. Faulkner, The Ancient Egyptian Coffin Texts, 3 vols. (Warminster, England: Aris & Phillips, 1973) 1:119n3.

[44] . vsw.t is not found in Wb.

[45] . See previous footnote.

[46] . The text has cwt “you” (2 per. m.s.).

[47] . iakbw: a place in the hereafter, Wb 1:34, 16.

[48] . The text then describes various good things that will be done for the gods.

[49] . Lepsius, Das Todtenbuch der Ägypter nach dem Hieroglyphischen Papyrus in Turin, 5, 52.

[50] . Naville, Das Aegyptische Totenbuch der XVIII. bis XX., 256.

[51] . Davies, The Tomb of Nefer-hotep at Thebes, pl. LVIII–LIX, c, and 67.

[52] . Davies, The Tomb of Nefer-hotep at Thebe, LXIII–LIX, c, and 67.