Religious Aristarchy of the Kingdom, 1851–1869

First get the families united, then get the wards, the towns, the cities, and the counties regulated, and you will have every part of the territory right. . . . I would like to see the work of reformation commence and continue until every man had to walk to the line; then we should have something like union.

—Jedediah M. Grant, 13 July 1855.[1]

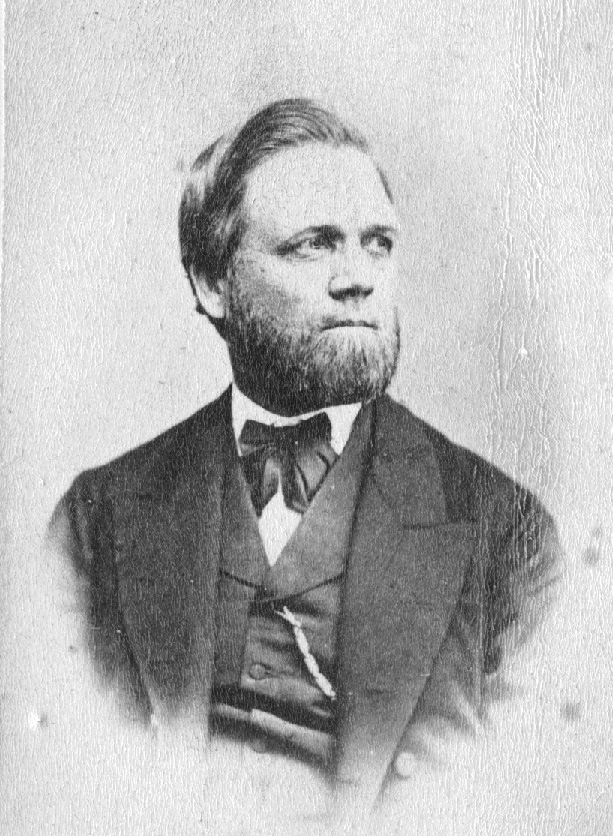

Electioneer Experience: Franklin D. Richards. Franklin D. Richards became president of the British Mission—the largest of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—on 1 January 1851. Although he was only thirty years old, this was already his second time as a leader in Europe. It would not be his last. From the moment of his call as an electioneer at age twenty-three, Richards catapulted into church leadership. While electioneering in the East, he learned of Joseph’s death and obediently returned to Nauvoo. In 1845 church leaders sent him to Michigan to gather funds for the temple. Traveling a thousand miles in frigid weather, he collected an impressive five hundred dollars. After receiving his temple ordinances in early 1846, Richards responded to a call to join his brother and fellow electioneer Samuel W. Richards on a mission to England. After helping his pregnant wife and infant daughter cross the Mississippi River, he and Samuel headed for England. The last letter he read before embarking overseas explained that his wife lay at death’s door and his newborn son had already crossed that threshold.

Upon arrival in Liverpool, leaders appointed Richards to preside in Scotland, with Samuel assisting. Soon Richards was a counselor to Orson Spencer, president of the British Mission. In February 1848 Richards took leadership of a company of European Saints heading for Salt Lake City. The last letter from home that he read before departing again broke his heart. After contracting an illness in the Mormon Battalion, his brother Joseph had died. Compounding that tragedy, his own infant daughter had succumbed at Winter Quarters.

In October 1848 he and his wife arrived in Salt Lake City. Richards sold everything to construct a crude adobe home. Freezing in that rudimentary abode was not the only shock of the winter. On 12 February 1849, Brigham called twenty-eight-year-old Richards to the apostleship. Then, as was typical in theodemocratic governance, the following month he joined the Council of Fifty and the Assembly of Deseret. October saw him headed to England again, this time as president of the British Mission. He established the European infrastructure of the Perpetual Emigrating Fund (PEF), oversaw multiple publications, and presided over a spike in converts—more than sixteen thousand. In 1852 he personally led a PEF company to Salt Lake, where he reentered what was now the territorial legislature and traveled south to help bolster the floundering Iron Mission.

His work done in southern Utah, he returned to Salt Lake City only to be sent again to England. This time, however, all of Europe was one mission, with Richards at its head. European missionary work flourished under his touch, including the opening of several new countries to proselyting. In 1856 he and fellow electioneer Cyrus H. Wheelock led another PEF company to Utah. Richards was also partly responsible for two handcart companies that encountered disaster that season. They had started the trek to Utah late and were caught on the high plains in subzero snowstorms. Despite the heroics of rescue parties, 210 of the nearly 1,000 emigrants perished. The blame fell at the feet of Richards and electioneer colleague Daniel Spencer, who was in Nebraska supervising emigration. Brigham rebuked them publicly, saying that they should “have known better than to rush men, women, and children on the prairie in the autumn months . . . to travel over a thousand miles.”[2]

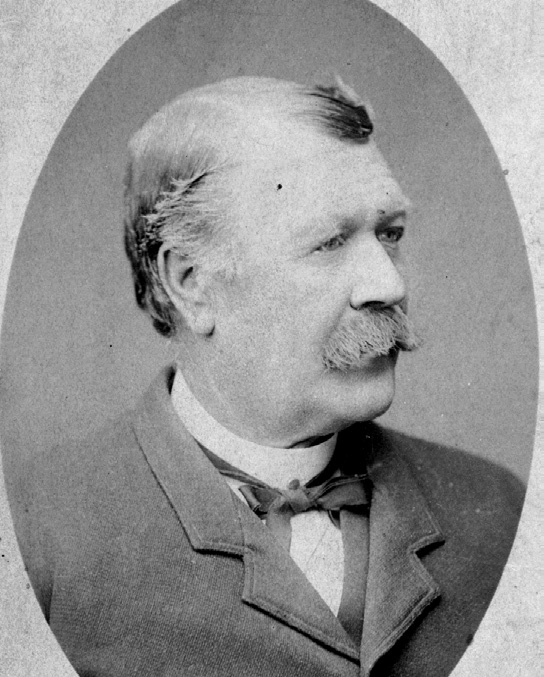

The career of Franklin D. Richards is the epitome of the electioneers’ stunning postcampaign success. Courtesy of Church History Library.

The career of Franklin D. Richards is the epitome of the electioneers’ stunning postcampaign success. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Yet whatever blemish Brigham’s words gave Richards, the prophet still trusted him as a leader. In the following three months Richards was reelected to the legislature, renamed regent of the University of Deseret, and made a brigadier general in the Nauvoo Legion. Brigham sent Richards to southern Utah in 1859 to reorganize all the settlements politically. For the next seven years, Richards was a religious, political, social, and economic leader in the territory. In 1860 he had thirteen wives and seven thousand dollars in wealth. His fourth mission to England began in 1866, once again as president of the European Mission. Converts and emigrants continued to increase under his watch, which ended in late 1868.

Arriving back in Utah, Richards was immediately assigned to Ogden. The intercontinental railroad was nearing completion, bringing with it a flood of gentile influence that concerned church leadership. Ogden was ground zero for this coming clash, and Brigham wanted Richards in charge. He became not only president of the Weber Stake but also a member of the territorial legislature and Weber County probate judge. In these positions he effectively defended theodemocratic Zion in Weber County from the infringements of gentile culture and the federal government for two decades.

Franklin D. Richards was the epitome of the electioneer cadre’s stunning postcampaign success in becoming a crucial component of the aristarchy in the Great Basin kingdom. In 1844, as a poor, inconsequential young man, he had volunteered to campaign for his prophet. By 1869 he was a territorial elite and Brigham’s right hand in defending the theodemocracy they both had advocated for as electioneer missionaries and later had helped establish in the West. Priesthood office and positions came his way during the election campaign and continued throughout his life. As he wrote presciently during the campaign, “[I am] on my way to perform this important mission [to campaign for Joseph Smith], the faithful and acceptable performance of which involves my future prosperity in church life.”[3]

One might credit all this to nepotism—he was the nephew of apostle Willard Richards. However, Willard Richards and other Nauvoo-era apostles had hundreds of nephews, sons, brothers, and other male relatives. None rose as Franklin did, so quickly and so high. Those that came close were, like Franklin’s younger brother Samuel, also electioneers. It was apparent to church leaders from the early days of electioneering that Franklin and others like him had the right attributes to be entrusted with leadership responsibilities. Early postcampaign assignments fulfilled well led to more and more responsibilities until the electioneer cadre for the kingdom became the critical core of the aristarchic cadre of the kingdom—the workhorses of Zion.

* * *

The electioneers’ contributions to the Great Basin Kingdom from 1851 to 1869 occurred against the background of significant religious, political, social, and economic events and trends. Shaping these events while being shaped by them, the electioneers endured as a critical corps in building and strengthening Zion despite looming threats to its existence such as the Utah War, the Civil War, and the Transcontinental Railroad. With thousands of Latter-day Saint immigrants arriving in the valley each summer, established towns in Deseret grew in population even as church leaders created new settlements. This intensified the need to create municipal governments and to fill important roles in the theodemocracy in order to better direct this expansion. As before, it often fell to the capable electioneers to help lead settlements, counties, and even the nascent Utah Territory in all aspects of life.

In 1860, the midpoint of the time period under discussion, the average Latter-day Saint male in the Great Basin was nineteen years old and had British parents and several siblings. He labored in construction or agriculture and was a priest or elder.[4] By comparison, the average electioneer was fifty years old, with American-born parents and multiple wives. He was a prosperous landed farmer and a high priest with local or even territorial religious, political, and economic responsibilities. By calling on the electioneers’ experience along those lines, church leaders could continue creating theodemocracy in the Great Basin.

Church leaders orchestrated the building up of Zion at a rapid pace throughout the 1850s and 1860s. In 1851, with Salt Lake City as the new headquarters of Zion now secure under the wings of a church-dominated territorial government, Brigham increased the urgency of the gathering effort. He made four decisions that enabled many Saints to flock to Deseret and receive temple ordinances that would set them apart from the world and cement their commitment to the cause of Zion. Electioneer veterans factored in each decision. First, he ordered the evacuation of the faithful but destitute Saints still camped along the Missouri River. Second, he increased the number of missionaries and expanded their fields of labor. Third, these same missionaries were to strongly encourage their converts to gather to Zion, and even provide financial assistance for doing so. Fourth, Brigham expanded the number of colonizing missions in the Great Basin to create space for new arrivals and to protect Zion from outside settlement. To see that these measures were carried out, Brigham and other leaders regularly turned to the electioneers.

Evacuation of Western Iowa

In 1849 church leadership created the Perpetual Emigrating Fund, whereby Latter-day Saints donated money to “promote, facilitate, and accomplish the emigration of the poor.” Emigrants were expected to repay the costs so the program could continue in perpetuity. Brigham charged fund officers Ezra T. Benson and Jedediah M. Grant (both electioneer veterans) to evacuate the Saints stranded in western Iowa. In a general epistle to the church, Brigham declared that Benson and Grant were “sent expressly to push Saints to this valley.”[5] And push they did. Benson and Grant told the Saints in Iowa “not to be afraid of the plains, but to encounter them with any kind of conveyance that they can procure, with their handcarts, their wheelbarrows, and come on foot, pack and animal, if they have one, and no other way to come.”[6] In 1851 twenty-five hundred Saints reached the Salt Lake Valley. The following year more than six thousand pioneers made the trek—the largest flow of the two-decade emigration. When Benson and Grant returned to Salt Lake in August 1852, they left Iowa “almost entirely vacated by the Saints.”[7]

With most Saints in North America gathered, Brigham commenced construction of the Salt Lake Temple. On 6 April 1853, Saints throughout the region gathered to witness priesthood leaders dedicate the cornerstones. Four of the eight officiators were electioneers. Presiding bishop of the church Edward Hunter laid the southwest stone, declaring, “I have acted in the priesthood and the part allotted me, with the love and fear of God before my eyes, by the aid of His Spirit to the best of my ability, and I hope acceptably in the sight of God and those who preside over me in this latter-day work.”[8] His counselor and electioneer comrade Alfred Cordon offered the stone’s dedicatory prayer. John Young gave the oration at the placing of the northwest cornerstone, followed by a dedicatory prayer from fellow electioneer George B. Wallace. Electioneer Joseph Curtis, who had made the fifty-mile trip from Payson, captured the solemnity of the moment, recording, “O Lord, may I never forget.”[9]

Expanded Missionary Work

Although the church was now headquartered in the West, some former electioneers continued to labor as missionaries throughout the United States. However, the church’s public pronouncement of plural marriage in 1852 made Latter-day Saints pariahs and limited their missionary success. The Utah War and Civil War further disrupted proselyting efforts. George W. Hickerson, serving in Mississippi in 1854, wrote to his wife, “My labours [are] . . . all traveling and no preaching. It is very seldom I get the opportunity to preach. [A]s a general thing the people that have heard don’t want to hear anymore, and those that have not heard do not wish to hear, for the name of a Mormon is enough for them.”[10]

In August 1852, at a special conference of the elders in Salt Lake City, church leaders called 110 missionaries to proselyte around the world. This extraordinary meeting was an echo of the April 1844 meeting that selected the electioneers. In fact, this new missionary force was the largest since Joseph’s campaign. Naturally, electioneers figured predominantly—twenty-four in all.[11] Throughout the 1850s and 1860s, electioneers served as missionaries, most often as presiding officers. Amasa Lyman, Charles C. Rich, Lorenzo Snow, Franklin D. Richards, and Chauncey W. West took turns presiding over the European Mission. In France, Andrew Lamoreaux presided, fulfilling a prophecy Joseph made in 1839. In tears, Joseph had told Lamoreaux that when he completed this future mission he would die and not return to his family. While accompanying converts immigrating to Utah, Lamoreaux died of cholera in St. Louis.[12] George C. Riser worked with such zeal and success as the German Mission president that the authorities imprisoned him.[13] Daniel Tyler presided over the Swiss, Italian, French, and German missions with few conversions despite continual travel and labor.[14]

The largest segment of missionaries, including electioneers, served in Europe. European Saints felt “more highly favored” to hear from a former electioneer missionary “of the old stock” because they “had a knowledge of Joseph, the prophet, and an acquaintance with him.”[15] Great Britain continued to be fertile ground for converts. For two decades, electioneers serving as missionaries found proselytes there.[16] Dan Jones, one of the last electioneers to have seen Joseph alive, continued to fulfill the prophecy that he would preach with great success in Wales. Under his leadership, thousands converted and emigrated to Utah.[17]

Fifty-two of the 110 missionaries left for California to find passage to their missions in Asia, Australia, and the islands of the Pacific. A dozen were electioneers. The combined one-way total for all their voyages was more than six thousand dollars. They dispersed to find work and soon raised the money. Between January and April of 1853, they began sailing to their destinations. Curiously, wealthy but disaffected California electioneers John S. Horner and Samuel Brannan financed several of the electioneer missionaries. While not devoted to Brigham, disaffected electioneers often remained loyal to their electioneer colleagues.

Brigham assigned electioneer veterans to lead the Asia Mission. Nathaniel V. Jones opened India and served as mission president for three years.[18] Elam Luddington and Chauncey W. West, assigned to Siam, worked with two other missionaries in Calcutta, India, and then Bangkok. Luddington later wrote that the group traveled thirty thousand miles on three different ships, baptizing sixteen converts.[19] Chapman Duncan and Hosea Stout landed in Hong Kong in April 1853. Upon arrival the men found “the situation and conditions in that country entirely the reverse from what [they] expected.”[20] Unable to speak Chinese, the missionaries approached the small European population, all of whom rejected them, even disseminating lies about the missionaries’ intentions. With money and welcome running out, the missionaries returned to California.

Twenty-one missionaries traveled to the Society Islands to continue the work begun in the mid-1840s. The conditions were so difficult that all but three returned home. Not coincidentally, the three who remained were dedicated former electioneers: Sidney A. Hanks, Jonathan Crosby, and Simeon A. Dunn.[21] They converted hundreds until 1853, when after a change in government they were banished.[22] Hanks managed to remain for eight years until he was accidentally rediscovered by other missionaries. They communicated his situation to Brigham, who promptly released him to come home.[23] Nathan Tanner, William McBride, Lorenzo Snow, and Ezra T. Benson all served in the Sandwich Islands (Hawai‘i), converting sizable congregations.[24] Charles W. Wandell introduced the church to Australians in 1851. When he returned home in 1853, August A. Farnham presided and, along with Josiah W. Fleming, continued the church’s growth.[25]

Prolonged and extensive missionary work in faraway lands took its toll on electioneer missionaries and their families. A few even died during their exertions. Levi Nickerson, called to Great Britain, became sick during extreme weather in Iowa. Severely ill, he lingered for a year before being found dead in his tent, orphaning six children in Utah. In tragic irony, he died only miles from where his father perished seven years earlier.[26] Stephen Taylor passed away in the eastern United States, and William Burton died in England.[27] Willard T. Snow, a territorial legislator and member of the First Quorum of the Seventy, became violently ill in Denmark.[28] He died en route to convalesce in England. Thomas Atkinson and his companion died when their steamer, Ada Hancock, exploded in San Pedro Harbor.[29]

Upon arriving home from Australia, Augustus A. Farnham met a small boy playing near his house. He called, “Hello, sonny, what’s your name?”

The child answered, “Gussy Farnham.”

“Is that so—that’s my name, too,” Augustus responded. When he entered the house, he found his wife packed and ready to leave for the East. No amount of persuasion could prevail on her to stay. The child was his own son—born after he had departed for his assignment. His wife also took their daughter, a tragic end to his five-year mission.[30]

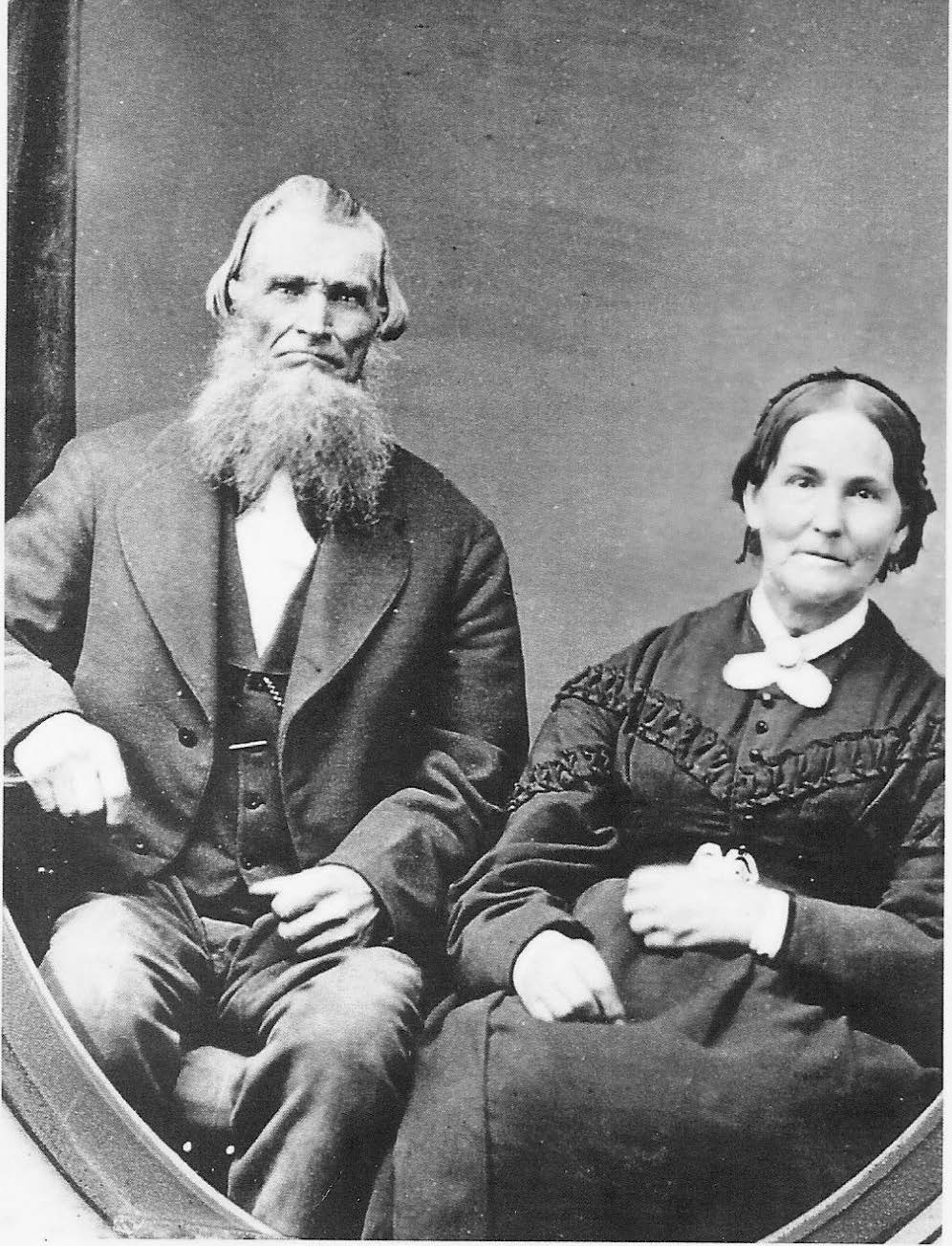

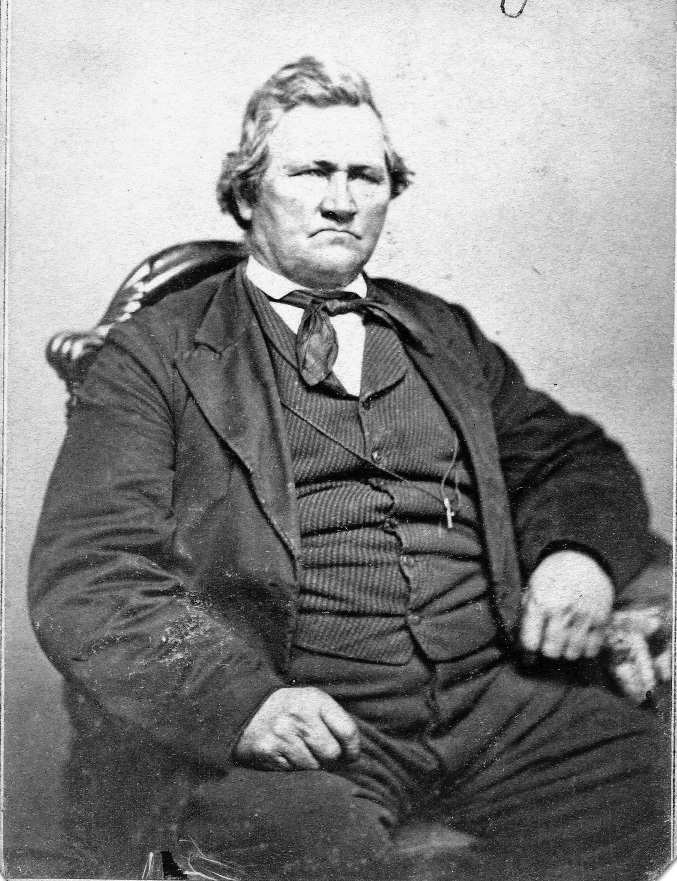

Israel and Elizabeth Barlow courageously sacrificed throughout their lives to build up Zion’s theodemocracy. Courtesy of Israel Barlow Family Association.

Israel and Elizabeth Barlow courageously sacrificed throughout their lives to build up Zion’s theodemocracy. Courtesy of Israel Barlow Family Association.

Upon Israel Barlow’s call to Great Britain, his wife asked that he stop in Nauvoo to rebury their infant son James, who had been hastily interred at their former farm. Barlow struggled to find the grave because the farm’s layout had changed. He eventually found the coffin and the remains scattered and all but destroyed. He quickly and brokenheartedly reburied them. As he turned to leave, he heard a voice plead, “Daddy, do not leave me here.” Obedient, Barlow carefully moved the remains to Nauvoo’s public cemetery. He wrote to his wife that the decision brought “a very peculiar calm and peace of mind which before I did not feel.” Barlow placed the remains in a new coffin and buried it in the cemetery with a “rude stone” to mark the grave.[31]

Pondering over the new resting place of his firstborn son, Barlow “felt a desire to dedicate [him]self” to the work of Zion so that he might have his son again in the Resurrection. Melancholy, he wrote to his wife that he had fulfilled her request, adding grape and apple seeds from their former farm in the envelope. He concluded, “If I have desire to glory in anything, it is in aiding to build up that kingdom, and I do most candidly confess that I do feel to glory in the cause I am engaged in, for it seems all glorious to me at times.”[32] While Barlow was in England, his family suffered. Two sons died and another came perilously close. Local priesthood leaders, including Barlow’s electioneer companion David Candland, did what they could to minister to the family.[33]

Emigration

Brigham sent electioneer veterans Abraham O. Smoot, Willard Snow, and Samuel W. Richards to coordinate the PEF in England. Leaders there chose Smoot to captain the first PEF company. The relative smoothness of the operation opened the floodgates for European Saints to emigrate. Over the next decade and a half, several electioneers led companies of converts to Zion.[34] Richards, while presiding over the work in England, testified before the British House of Commons to allay concerns regarding the Latter-day Saint emigration. While he and his brother Franklin (also a former electioneer) presided in England, more than fourteen thousand Saints traveled to Utah.[35] Electioneer missionaries helped converts emigrate from other nations as well, most notably Australia. In 1856 Augustus A. Farnham and Joseph Fleming sailed from Sydney with a company of Saints bound for Zion. Joseph A. Kelting led another group the following year.[36]

Church leaders in St. Louis were the linchpins in this intercontinental mass migration. St. Louis became the major way station for European Saints to rest while PEF agents provided wagons, oxen, and supplies for the trip across the plains. Throughout the 1850s, Brigham placed trusted electioneers in St. Louis to preside over the Saints and to supervise the PEF. Starting in 1852, Horace S. Eldredge served there for two years. It was not an easy assignment. Cholera plagued emigrants, and Eldredge himself became sick. Yet he worked tirelessly to comfort and arrange the affairs of thousands of converts. Hundreds of Saints contributed to purchase a gold ring for him, a token of their gratitude.[37] Brigham chose Aaron F. Farr to replace Eldredge, followed by Milo Andrus. Erastus Snow next oversaw a two-year period, expanding and strengthening St. Louis as a Latter-day Saint outpost. He organized a stake of Zion, published the St. Louis Luminary, and constructed a new outfitting post.[38]

Colonizing Missions

In 1850 church leaders sent a colonizing mission south in search of iron ore. This decision was part of Brigham’s goal to be free from the gentiles through economic self-sufficiency. Apostles George A. Smith and Ezra T. Benson (electioneer) led the group, dubbed the Iron Mission.[39] Church leaders selected several electioneers for the expedition.[40] By summer a town existed with school, mills, stores, and surrounding farms.[41] Edson Whipple’s journal details the roles he played. Called by Brigham to join the colony, Whipple was appointed by local leaders as associate justice of the nascent county. They also selected him as a militia captain. Of the plans presented to lay out the settlement, Whipple proudly wrote, “Mine was accepted and adopted, and Parowan was built up according to my plan.” Local church leaders nominated Whipple, and he was subsequently elected to the Parowan City Council.[42]

Latter-day Saints also colonized San Bernardino, California. Brigham wanted the colony to become the primary way station for emigrating converts coming from San Diego and up the “Mormon Corridor” of settlements to Salt Lake City. Again, electioneers were in the lead. In 1851 Brigham selected electioneer apostles and California veterans Amasa Lyman and Charles C. Rich to lead a company of more than four hundred Saints to San Bernardino. Lyman and Rich recruited families for the mission, including men from the electioneer cadre.[43]

The experiences of two electioneers illustrate the successes, the difficulties, and ultimately the failure of the venture. Jefferson Hunt, former commanding officer of the Mormon Battalion and veteran of the California trails, was an obvious choice for the company’s scout. Using his contacts in California, Hunt negotiated the massive purchase of land, personally guarding the twenty-five thousand dollars in gold coins. His impeccable reputation among Californians won important concessions for the Saints. He was so highly regarded that the governor appointed him commander in chief of the California Militia. Hunt represented the Saints in the California legislature and served as an assemblyman in San Bernardino County. Concurrently, church leaders placed him on the colony’s high council. Hunt bought half interest in the colony’s sawmill and held the mail contract between San Bernardino and Salt Lake City. Unfortunately, he and the others abandoned San Bernardino in 1857 because of the Utah War. He sold his interest in the sawmill for one-tenth its value and moved back to Parowan.[44]

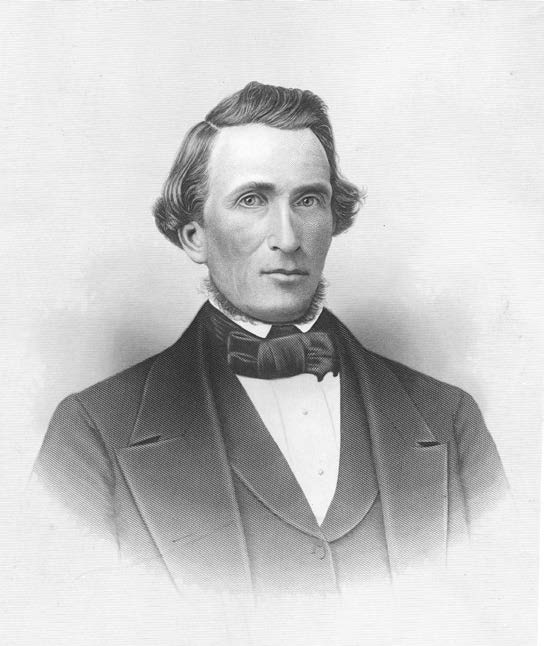

Jefferson Hunt served in the

Jefferson Hunt served in the

Mormon Battalion and in the Deseret and California legislatures and helped settle San Bernardino, California. Courtesy of Myron Taylor.

Henry G. Boyle reluctantly moved his young family to San Bernardino when electioneer colleagues Amasa Lyman and Charles C. Rich recruited him. A Mormon Battalion veteran, Boyle did not wish to return to the land of his earlier suffering. Little did he know that his grief was just beginning. A year after arriving, Boyle’s young wife died. “She has been a faithful good Mormon,” he wrote, “and I feel the loss to be very great.” A widower with young children, Boyle served several missions, including a “gold mission.” Continued time away from his small family destroyed his peace. So too did seeing former friends excommunicated for dissent. “It is a painful thing to be a witness of,” he penned; “it makes my blood chill in its veins. God grant that I may never depart from the truth.”[45] He too fled San Bernardino in 1857 owing to the Mormon War. “I think I shall feel like I have been released from hell when I shall have got away from here,” Boyle wrote. He never returned to San Bernardino.[46]

When the Civil War stopped cotton shipments, church leaders decided to create a colony in southern Utah to produce cotton and other amenities. The “Cotton Mission” settled present-day St. George in 1862 with several hundred families. Electioneer apostle Erastus Snow directed the effort, declaring, “I feel to go body and spirit, with my heart and soul, and I sincerely hope that my brethren will endeavor to do the same.”[47] In the first company, and over the years, numerous electioneers participated in colonizing St. George. For example, Lysander Dayton built the first home there and served on the high council, and Lewis Robbins served as Washington County’s representative to the territorial legislature until he tragically died in an accident at the temple site.[48]

Henry G. Boyle experienced the

Henry G. Boyle experienced the

difficulties of creating theodemocracy in San Bernardino, California.

Courtesy of Church History Library.

Difficulties sometimes outweighed success in these and other colonies in the Great Basin kingdom. As it turned out, the Iron Mission yielded very little iron, and for decades Utah’s “Dixie” failed to produce enough cotton for the effort to be viable. The church’s hope for a stronghold in California evaporated with the abandonment of San Bernardino. Even smaller colonies were not immune to the troubles of planting theodemocratic Zion. The experiences of James Pace and other electioneers who settled Payson, Utah, illustrate the difficulties. Pace led several Saints to southern Utah Valley in 1850. Brigham ordained him branch president and named the settlement in his honor—Payson. Pace recorded, “During the remainder of the season nothing of importance transpired excepting the ordinary routine of trials, confusions, and difficulties at tending the building up of a new settlement with all classes of men to do it with, including all their peculiarities and notions of right and wrong.”[49]

The aforementioned difficulties came to a head in late 1851. Pace excommunicated James McClellan but refused to go to the high council in Provo to explain his action. The council promptly removed Pace as branch president and placed McClellan in his stead. Electioneer and Paysonite Joseph Curtis recorded that the series of events created “quite a sensation throughout the branch.” “Unpleasant feelings” persisted among the members there, threatening unity and progress.[50] Brigham intervened by sending Pace on a three-year mission to England with fellow electioneer Calvin Reed. Curtis looked after Pace’s family by threshing wheat, administering priesthood blessings, and otherwise shepherding them. Peace prevailed for a year in the settlement now presided over by Bishop Blackburn. However, in June 1853 Charles Shumway was disfellowshipped for “unchristian conduct.” The next day, a penitent Shumway pleaded for forgiveness and Blackburn restored him to fellowship. Less than a month later, a letter from Pace accused Blackburn of trying to steal his wife while he was away on his mission. Blackburn denied the charge. When two weeks later an American Indian shot and killed a settler, the outside threat dampened the internal dissension and the settlement literally closed ranks. In December 1855, the First Presidency stopped in Payson while traveling to central Utah. They held a conference at the home of Pace, who had just returned from England, to settle the issues dividing the community. The next day, the residents, including Pace, submitted to rebaptism to demonstrate their commitment to obey the gospel and their appointed leaders.[51]

Yet colonizing itself also further cemented electioneers to the cause of Zion. During these years they overcame obstacles and accomplished remarkable feats in settling hundreds of towns in the Great Basin. As ecclesiastical and political leaders, they directed many of the fledgling colonies. Because church leadership carefully selected those who led each new outpost of Zion, it is no coincidence that they so often turned to the familiar, faithful, and capable electioneer veterans. Many electioneers assisted in building multiple settlements. Daniel Allen settled seven towns while plying his trade as a shoemaker. Nine settlements benefited from talented carpenter David Savage. John D. Chase served as mayor of Moroni, as bishop in Manti, and as a member of the Juab (Utah) and Carson Valley (Nevada) high councils, with a mission to England squeezed in. Chapman Duncan colonized Big Cottonwood and Parowan before leaving on a mission to China in 1852. Upon his return, he settled Carson Valley and then became the county recorder and probate judge in St. George. He later struck out on his own, founding Duncan’s Retreat. George G. Snyder aided in settling eleven settlements in California, in Nevada, and throughout Utah. During that time he also served a mission in England and was a bishop and probate judge. These and many other electioneers responded to calls from church leadership to build, community by community, the Zion they longed for. Their experience and leadership were invaluable to church authorities.

Reformation

However, a decade of living in the wilderness took a spiritual toll on the Saints. To counter what he saw as backsliding, in late 1855 Brigham instigated a “home missionary program.” It was the beginning of what is often called the “Mormon Reformation”—a concerted effort to stem apostasy, increase devotion, and build unity among the Saints.[52] “Many are stupid, careless, and unconcerned,” Brigham declared. “They . . . are off their watch, neglect their prayers, forget their covenants and forsake their God, and the devil has power over them.”[53] One reason for Brigham’s harsh correction was three straight years of grasshoppers, canyon fires, and harsh winters destroying crops and livestock. He saw these events as the chastening hand of God because the Saints were backsliding. It was the biggest crisis yet of the Great Basin kingdom. Zion seemed to be collapsing.

Jedediah M. Grant, a former electioneer and later a member of the First Presidency and mayor of Salt Lake City, led the Reformation, a constant effort that eventually cost him his life. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Jedediah M. Grant, a former electioneer and later a member of the First Presidency and mayor of Salt Lake City, led the Reformation, a constant effort that eventually cost him his life. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Brigham turned to the rod of repentance. Later reminiscing, he said, “One day, I told a number of the brethren how I felt, as well as I could; and Brother Jedediah M. Grant [former electioneer] partook of the Spirit that was in me and walked out like a man, like a giant, and like an angel, and he scattered the fire of the Almighty among the people.”[54] Grant, a counselor in the First Presidency, attended a four-day conference in Kaysville in which he delivered a thunderous message of repentance that was powerful and unforgiving. “The church needs trimming up, and . . . you will find in your wards certain branches which had better be cut off.” The solution was simple: “First get the families united, then get the wards, the towns, the cities, and the counties regulated, and you will have every part of the territory right. . . . I would like to see the work of reformation commence and continue until every man had to walk to the line; then we should have something like union.” [55] Grant created a catechism that included spiritual and temporal questions. It became the model for similar versions used by home missionaries throughout the church charged with watching over their fellow Saints.

Electioneer leaders stepped into line. In December 1856, Provo Stake president Jonathan O. Duke and his counselors reported, “Catechizing the Saints . . . by the catechisms got up by the First Presidency of the Church, which the Lord has graciously been pleased to pour out his Spirit on the Saints in these valleys, and a great reformation is tak[ing] place in settlements.”[56] Joseph Holbrook remembered Grant visiting his ward for a two-day conference. After the members had been rebaptized, Grant emphasized that “every brother and sister be careful to sin no more for fear a more terrible scourge should wait them, as they could not commit iniquity with the same degree of allowance as they could before they received their covenants in the waters of baptism.” Holbrook stated that after rebaptism they were all “catechized as [to] what we had been guilty of in our every act so that we might now begin anew to possess eternal life.”[57] Like so many others, Holbrook promptly married a plural wife to show his devotion.

The Reformation’s reach extended even to England. In February 1857 apostle Ezra T. Benson, Phineas Young (both electioneers), and other leaders in England met together. “We then took into consideration the president’s [Brigham] letter on reformation,” Phineas wrote, “and unitedly agreed to reform our lives, repent of our sins and do better than we had ever done, and fast the next day.”[58] That evening they renewed their covenants through rebaptism, an act repeated in branches throughout the church. Meanwhile, Brigham, Kimball, and Grant kept up the pressure, rebuking the Saints for “lying, stealing, swearing, committing adultery, quarreling with husbands, wives, and children, and many other evils.”[59] Grant continued thundering his message of reformation from settlement to settlement until he suddenly died from rheumatic fever.

Grant’s untimely passing was not the only result of the Reformation of 1855–57. There was a spike in religious devotion, seen in dramatically increased church attendance, tithing receipts, communal unity, and especially plural marriage.[60] Electioneer David Fullmer recorded that the Reformation had “turned away the anger of the Lord” and that he had never seen such a time of unity and blessings since he had come into the church.[61] Unfortunately, the excessive and hyperbolic rhetoric of the Reformation, intended to instigate commitment, gave enemies of Zion ammunition to accuse the Saints of provoking violence and was a precursor to the Utah War. Furthermore, rushed marriages led to a later rash of divorces, including among electioneers.[62] Overzealous leaders and home missionaries also created hard feelings among some of their charges. For the electioneers, perhaps their reactions were much like that of James Pace: “I participated in the Reformation, then prevalent among our people,” he wrote, “though not to the extent of wild enthusiasm that some manifested.”[63]

Dissidents

During the years of 1851–68, some electioneers chose to break with Brigham and the cause of theodemocratic Zion. Others who had previously dissented continued their lives outside the faith. Many people in both categories ultimately found a religious home in the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (now known as the Community of Christ), organized in 1853. Disaffected electioneers were at the center of its genesis. After Joseph’s assassination, Zenos H. Gurley Sr. chose to follow James J. Strang, serving as an effective missionary for that spin-off movement. In 1851 Gurley denounced Strang when the latter began practicing plural marriage. Gurley and Jason Briggs, brother of electioneer Silas H. Briggs, claimed to have received a revelation authorizing them to reorganize the faithful under the leadership of Joseph Smith III. Briggs took temporary leadership of the movement on 8 April 1853, calling Gurley to join him as an apostle. The “New Organization,” as it was called, numbered fewer than three hundred but boldly announced its claim and called on Joseph’s son to lead. On 6 April 1860, exactly thirty years since the organization of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Joseph Smith III assumed leadership of the now retitled Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. He was ordained as president by none other than Zenos Gurley.[64]

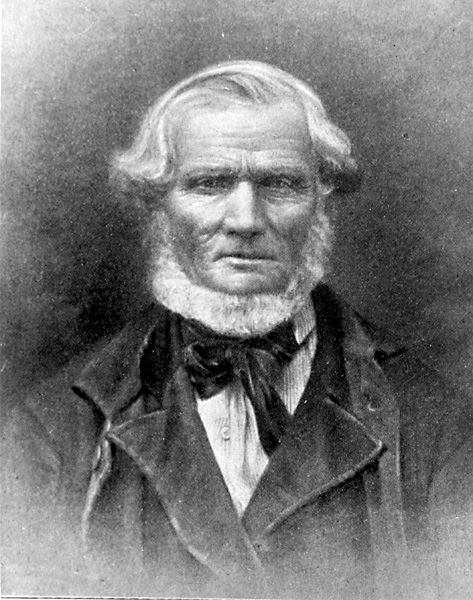

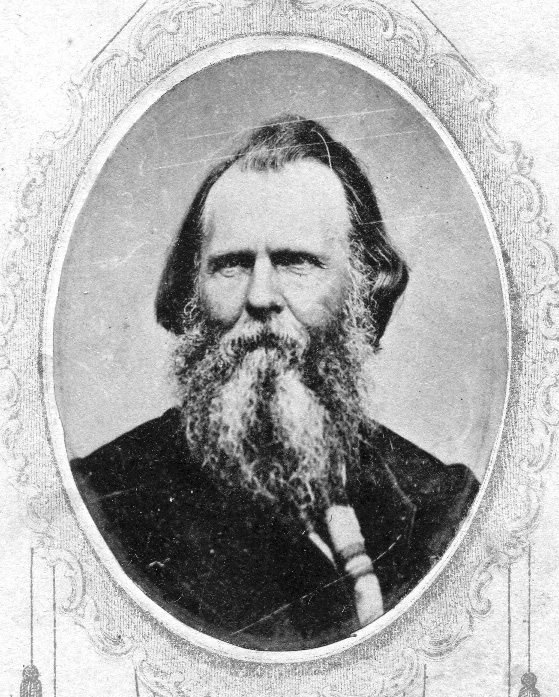

Former electioneer Zenos H.

Former electioneer Zenos H.

Gurley declared a revelation to

“reorganize” the church and later

ordained Joseph Smith III as president of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. 1868 photo by R. Thompson courtesy of the Community of Christ.

The Reorganized Church outlasted all other alternative sects of the Latter-day Saint movement. It dismissed plural marriage, temple ordinances, and “political Mormonism” as products of Brigham. Many midwestern and eastern Saints who chose not to follow Brigham, or who were remnants of failed offshoot movements, joined the Reorganized Church. Over time they also claimed some converts from Brigham’s fold, including a few electioneers. Generally, such men were weary of Young’s heavy hand and the demands of colonization, or they rejected plural marriage.[65]

Perhaps the RLDS Church’s most significant electioneer conversion was prolific proselytizer George P. Dykes in 1863. Dykes, a longtime Utah resident, used his contacts to create inroads for the RLDS Church in Utah and soon led a congregation of three hundred. In a letter to a friend who “expressed surprise” at his conversion, Dykes laid out his case. He declared that only the “posterity” of Joseph could lead and “[the fact] that young Joseph is the lawful head of the church . . . is positively evident from many scriptures.” Dykes was grateful that with “divine assistance [he was] turning scores from darkness to light and from the power of Satan to God, who are once more rejoicing in the fulness of the everlasting gospel.”[66] Yet only two years later Dykes left the RLDS Church as suddenly as he had joined.

Other electioneers found more solitary routes to fill the void of their former faith. Increase Van Deuzen rejected Strangism when Strang began teaching polygamy. In 1860 he returned to Kirtland, Ohio. That same year, he interrupted a meeting in the temple, walking across the tops of the pews and then leaping up on the pulpit. He turned and faced the alarmed audience and stripped off his coat, tearing it to shreds. He commenced stamping and hissing and swinging what remained of his coat while shouting repeatedly, “Now is come the time of your trial!” Frightened women fled the temple, and all experienced a very memorable meeting.[67] Stephen Post continued to support Sidney Rigdon, serving as his spokesman and single-handedly keeping the struggling movement alive.[68] David Judah became an apostle in the small “Hedrickite” movement centered in Independence, Missouri. The group purchased, and owns to the present day, the famed temple site there. Judah led the movement’s only known proselyting effort, an unsuccessful mission to American Indian tribes.[69]

George P. Dykes presided over

George P. Dykes presided over

Indiana during Joseph’s campaign, became a prolific missionary in Europe, and for a time headed the RLDS Church in Utah. Photo by Olson and Kearney courtesy of the Community of Christ.

A small number of electioneers simply left the faith all together. Phillip H. Buzzard originally followed Strang but became disaffected and left for California before settling down in Iowa and creating a freight company between Iowa and Utah. He remained nominally a Latter-day Saint until one visit to Utah. Ordered to pay tithing because of his wealth, Buzzard vehemently objected and eschewed the church permanently. He later moved to Spokane, Washington.[70] Joseph M. Cole remained in the Midwest and in 1856 fought alongside his nephew in the “Bleeding Kansas” skirmishes sparked by attempts to make the proposed state of Kansas a slave state.[71] Daniel Gardner left Utah and the church for the Washington Territory in 1854, becoming a justice of the peace, schoolteacher, and minister for the United Brethren Church.[72] Omar Olney returned to his native New York, becoming a very successful lawyer and author. Perhaps seeking to explain his past, he wrote a scorching exposé of the church.[73] Lester Brooks followed Strang after Joseph’s death but by 1854 had become a leader of the national movement of the Spiritualists.[74] Elijah Swackhammer, after following Rigdon, left the Latter-day Saint tradition altogether. The most radical and eccentric of the dissenters, he joined a group centered in Utica, New York, called “the Reformers.” They advocated free love and social communities, and they believed evil did not exist. Swackhammer continued to lecture on the Reformers’ philosophy for more than a decade and became an associate of abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison. A later census shows him listed as a “reverend” in New York.[75]

Some Great Basin electioneers, like Bushrod Wilson, felt persecuted within Brigham’s theodemocratic Zion. Wilson chafed under the leadership of the small village of Palmyra in Utah County: “I left Palmyra getting nothing for my farm and houses. I have been mobbed by the gentiles for being a Mormon, and at last I have been mobbed by the Mormons because I was not willing to do all that they told me to do, so I left for California.”[76] Arriving in San Bernardino, Wilson saw firsthand the struggle for political leadership in the colony. In April 1854 he wrote that “Br. J. Grouard and Frederick Van Leuven and Ruben Herron [were] disfellowshipped or cut off from the church for opposing the council of the church in politics. My faith in such doings is weak. I hate usurpation and tyranny.”[77] Wilson stayed in San Bernardino after the Saints evacuated three years later.

At least two dissident electioneers rejoined the flock during these decades. John Duncan, a veteran of the famous Zion’s Camp, initially joined Rigdon’s church after Joseph’s death. He moved to Pittsburgh, where he lived even after Rigdon’s movement collapsed. Following the Civil War, Duncan’s son Homer, who had gone west with the Saints, went to Pittsburgh to search for his father. Finding him, Homer Duncan brought John back into fellowship with the Saints.[78] In 1868 John attended his first Zion’s Camp reunion. Only twenty-nine veterans remained, and at eighty-nine years of age, he was the oldest. He enjoyed reuniting with former colleagues, who amicably called him “Father Duncan.”[79]

James Burgess was the other returning prodigal. As a recent English convert, he electioneered in Vermont. When Joseph was killed, Burgess continued his mission for another year. After marrying Lydia Stiles, he returned to Nauvoo, where he worked on the Nauvoo Temple, received his endowment, and was sealed to Lydia. Upon the evacuation of Nauvoo, Burgess and his campaign companion and fellow Englishman Alfred Cordon returned to Burlington, Vermont, in search of work. Cordon eventually went west with the Saints, but Burgess stayed in Vermont working as a carpenter. In 1863, now living in Iowa, Burgess joined the RLDS Church, becoming an effective missionary for almost a decade. In 1872 he moved to Utah and reunited with the Saints, living until 1904. Fitting capstones of his religious life were the two sons he named Joseph—the first born in 1847 in Vermont and the second born to his third wife fifty-three years later in Utah.

Ecclesiastical Leadership

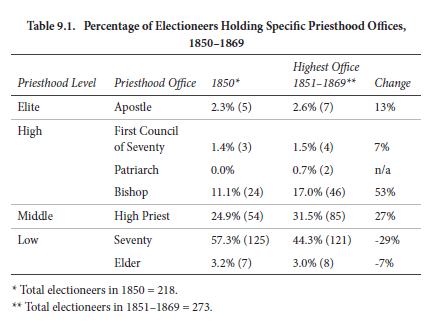

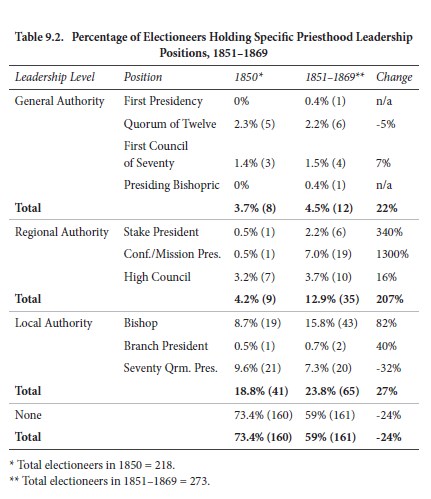

Surviving electioneers experienced changes in priesthood office from 1851 to 1869 (see table 9.1). Continued movement from the office of elder and seventy to high priest was natural with increasing age and wide opportunities to act in those offices. What is remarkable, though, is the increase in electioneers holding the office of bishop, patriarch, or Seventy in the First Council of Seventy, particularly the office of bishop. While the growth of Zion required more bishops, their numbers remained small until the large increase in electioneers called as bishops—further evidence of how their belief and experience in preaching and living the ideals of Zion and theodemocracy were qualifying attributes that church leaders valued. In Latter-day Saint settlements, the bishop presided over all the religious, social, political, and economic activities of his ward. Bishops were the major workhorses for Zion and theodemocracy—and a very disproportionate number of them were electioneers. The number of electioneers chosen as local, regional, and general authorities increased as well (see table 9.2). Most impressive was the rise in leadership positions at the regional level and bishops at the local level: stake president (340 percent of electioneers), conference/

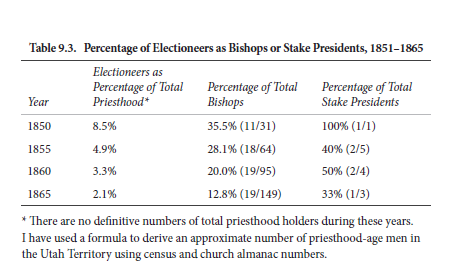

In fact, despite their small numbers among total priesthood holders, the electioneers represented a significant percentage of the regional and local leadership of the church (see table 9.3). In 1850, despite accounting for less than 10 percent of the priesthood population, they accounted for 35 percent of all bishops and 100 percent of all stake president positions. Such numbers reveal the electioneers as the backbone of the aristarchy. Over time, as they died and church growth produced more leaders and leadership positions, the electioneers’ influence slowly diminished. Yet even in 1865, when they represented only 2 percent of the priesthood population, they still accounted for six times that many bishops and fifteen times that many stake presidents.

* * *

Whether in missionary work, gathering, colonizing, or leading the Great Basin kingdom, throughout the 1850s and 1860s Church leaders made the electioneers the preeminent part of the aristarchy tasked with building and guiding Zion. Because the fusing of religious and political governance was inherent to theodemocracy, the creation of the Utah Territory was a boon to the church’s kingdom-building enterprise, giving the church hierarchy legally sanctioned governance to protect and guide the growth of Zion. To ensure optimal success, Brigham and his associates determined they would nominate and elect to political offices their general, regional, and local ecclesiastical leaders. In their combined roles, electioneer veterans such as Chauncey W. West became the workhorses of theodemocratic Zion, striving to bring the power of unity to their people. Although their apex of influence was in the late 1840s through the 1850s, the aging yet ever-capable cadre of electioneers continued to significantly build, shape, and lead the church through the 1860s.

Notes

[1] Jedediah Grant, in JD, 3:60.

[2] Brigham Young, “Remarks,” Deseret News, 12 November 1856, 283, as quoted in Christy, “Weather, Disaster, and Responsibility,” 23.

[3] Franklin D. Richards, Journal No. 2, 27 May 1844, 3.

[4] See Wahlquist, “Population Growth in the Mormon Core Area,” 132–33.

[5] First Presidency, “Sixth General Epistle [22 September 1851],” Deseret News, 15 November 1851, 2.

[6] Brigham Young to Ezra T. Benson, Journal History of the Church, 31 January 1852. The letter itself directed Benson and Grant to say similar words to the Saints in Iowa.

[7] First Presidency, “Eighth General Epistle [13 October 1852],” Deseret News, 16 October 1852, 2.

[8] Jenson, “Hunter, Edward,” Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 1:231–32.

[9] Curtis, Reminiscences and Diary, 96.

[10] “Letters of a Missionary, George Hickerson,” Utah, Our Pioneer Heritage (database).

[11] Some of those called were already on their missions. Electioneers sent to Europe—England: Daniel Spencer, Millen Atwood, Benjamin Brown, Osmon M. Duel, James Pace, Levi Nickerson, John S. Fullmer, and Duncan McArthur; Wales: Dan Jones; France: Andrew L. Lamoreaux; Germany: George C. Riser; Gibraltar: Nathan T. Porter. Electioneers sent to Asia—Hindustan: Nathaniel V. Jones; Siam: Chauncey W. West; China: Hosea Stout and Chapman Duncan; West Indies: Alfred B. Lambson and Aaron Farr. Electioneers sent elsewhere—St. Louis: Horace S. Eldredge; Australia: Augustus Farnham, Josiah W. Fleming, and William Hyde; Sandwich Isles (Hawai‘i): William McBride and Nathan Tanner.

[12] See “Andrew Lamoreaux,” Utah, Our Pioneer Heritage (database).

[13] See Susan Easton Black, “George C. Riser,” Latter-day Saint Vital Records II Database (hereafter “LDSVR”).

[14] See Black, “Daniel Tyler,” LDSVR (database).

[15] Paxton, “History of John S. Fullmer,” 6.

[16] Electioneers who served in Europe between 1851 and 1868 but were not called in 1852 included Nathaniel H. Felt, Samuel W. Richards, Jonathan Crosby, Jacob Gates, Henry J. Doremus, Abraham O. Smoot, George Snyder, Franklin D. Richards, and Chauncey W. West.

[17] See Black, “Dan Jones,” LDSVR (database).

[18] See Black, “Nathaniel V. Jones,” LDSVR (database).

[19] Luddington, “Luddington Family,” folio 4.

[20] Hosea Stout to Brigham Young, 27 August 1853.

[21] See “Society Islands Mission,” Utah, Our Pioneer Heritage (database).

[22] See “Society Islands Mission,” Enduring Legacy (database).

[23] See “Society Islands Mission,” Enduring Legacy (database).

[24] See Jenson, “Benson, Ezra T.,” Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 1:101.

[25] See Black, “Augustus A. Farnham,” LDSVR (database); and “Augustus A. Farnham,” Utah, Our Pioneer Heritage (database).

[26] See Black, “Levi Nickerson,” LDSVR (database).

[27] See Black, “Stephen Taylor,” LDSVR (database); and Black, “Appleton Milo Harmon,” LDSVR (database). Harmon wrote a poem about Burton’s death.

[28] See Anderson and Bergera, Joseph Smith’s Quorum of the Anointed, 144.

[29] See Black, “Thomas Atkinson,” LDSVR (database).

[30] “Augustus A. Farnham,” Utah, Our Pioneer Heritage (database).

[31] Israel Barlow to Elizabeth Barlow, 12 September 1853.

[32] Israel Barlow to Elizabeth Barlow, October 1853.

[33] See Israel Barlow to Elizabeth Barlow, 30 November 1854.

[34] See Jenson, “Richards, Samuel Whitney,” Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 1:718–19. Company leaders who were electioneers included Milo Andrus, John S. Fullmer, Israel Barlow, Lorenzo Hatch, Joseph France, Cyrus Wheelock, John O. Angus, and Samuel and Franklin Richards; other electioneers helped in different ways. For example, Howard Egan donated one hundred gold coins from his California trips.

[35] See Larson, Prelude to the Kingdom, 133.

[36] See “Ships Sailing from the Islands,” Utah, Our Pioneer Heritage (database).

[37] See Black, “Horace S. Eldredge,” LDSVR (database). See also “Ships Sailing from the Islands,” Utah, Our Pioneer Heritage (database).

[38] See Farr, Journal, 41; Milo Andrus, Autobiography; and Erastus Snow, Autobiography, 17–18.

[39] See Larson, Prelude to the Kingdom, 172.

[40] These electioneers included Ezra T. Benson, Chapman Duncan, Aaron F. Farr, Nathaniel Felt, Elisha Groves, John D. Lee, Elijah Newman, Elijah F. Sheets, William P. Vance, Edson Whipple, James Harmison, Joseph L. Robinson, and Jefferson Hunt. Others joined the colony later.

[41] See May, Utah: A People’s History, 72; and Duncan, “Biography,” 12.

[42] Jenson, “Whipple, Edson,” Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 561–62.

[43] The electioneers in this company were Henry G. Boyle, Ellis Eames, Jefferson Hunt, Harley Mowrey, Justus Morse, Calvin Reed, Henry Sherwood, Nathan Tanner, and William Hyde.

[44] See Elliott, Biographical Sketch of Jefferson Hunt, 12–14.

[45] Boyle, Reminiscences and Diaries, 1:14.

[46] Boyle, Reminiscences and Diaries, 1:146.

[47] Quoted in Larson, Prelude to the Kingdom, 185–86.

[48] See Wilkerson, Lewis Robbins: A Biography, 2–3.

[49] Pace, “Biographical Sketch,” 10.

[50] Curtis, Reminiscences and Diary, 92.

[51] See Curtis, Reminiscences and Diary, 91–109 (quotation on p. 98).

[52] Peterson, “Mormon Reformation of 1856–1857,” 61.

[53] Brigham Young, “Necessity of Home Missions—Purification of the Saints—Chastisement—Honesty in Business,” in JD, 3:115 (8 October 1855).

[54] Brigham Young, in JD, 5:168 (30 August 1857).

[55] Jedediah Grant, in JD, 3:60 (13 July 1855).

[56] Jonathan O. Duke, Reminiscences and Diary, 13 December 1856.

[57] Holbrook, Life of Joseph Holbrook, 134–36.

[58] Phineas Young, Diary, 4 February 1857.

[59] Woodruff, Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 4:448.

[60] See Daynes, More Wives than One, 101–10, 118, on the spike in plural marriages.

[61] Salt Lake Fifth Ward Fellowship Meeting Minutes, 28 June 1857, as found in Peterson, “Mormon Reformation of 1856–1857,” 76.

[62] At least twelve Reformation marriages of electioneers ended in divorce.

[63] Pace, “Biographical Sketch,” 11.

[64] See Speek, James Strang and the Midwest Mormons, 282, 320.

[65] Thirty-three cadre members joined the RLDS Church. Almost all had previously left The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

[66] George P. Dykes to Mrs. King, 8 August 1864.

[67] The incident was recorded many years later in Van Deuzen’s obituary in the Painesville Telegraph, 10 August 1882, 3.

[68] See M. Guy Bishop, “Stephen Post: From Believer to Dissenter,” in Dissenters in Mormon History, ed. Launius and Thatcher, 190–92.

[69] See Jenson, Historical Record, 5:14.

[70] See “Buzzard, P. H.,” Polk County 1880 Saylor Township Biographies.

[71] See Reader, “The First Day’s Battle at Hickory Point,” Samuel James Reader Papers.

[72] See Gardner, “Daniel and Lorena Gardner.”

[73] See Hand, ed., History of the Town of Nunda, 167.

[74] See N. P. Tallmadge, Spiritualists Memorial to Congress, as found in Hardinge, Modern American Spiritualism, 128–33; and Tuttle and Peebles, Year-Book of Spiritualism for 1871, 226.

[75] “The Cause and Cure of Evil,” New York Times, 2 September 1858, 4; and Religious Society of Progressive Friends, Thirteenth Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Progressive Friends held at Longwood Chester, PA., 5–8th of June 1865 (Hamorton, Chester Co., PA: Isaac Mendenhall, 1865), 6.

[76] Wilson, Journal, 3.

[77] Wilson, Journal, 3.

[78] See Morrell and Deeben, “History and Genealogy of John Chapman Duncan,” 8.

[79] “From Monday’s Daily,” Deseret News, 14 October 1868, 285.