R. Lanier Britsch, "By All Means: The Boldness of the Mormon Missionary Enterprise," in Go Ye into All the World: The Growth and Development of Mormon Missionary Work, ed. Reid L. Neilson and Fred E. Woods (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2012), 1–20.

R. Lanier Britsch is a professor emeritus of history at Brigham Young University.

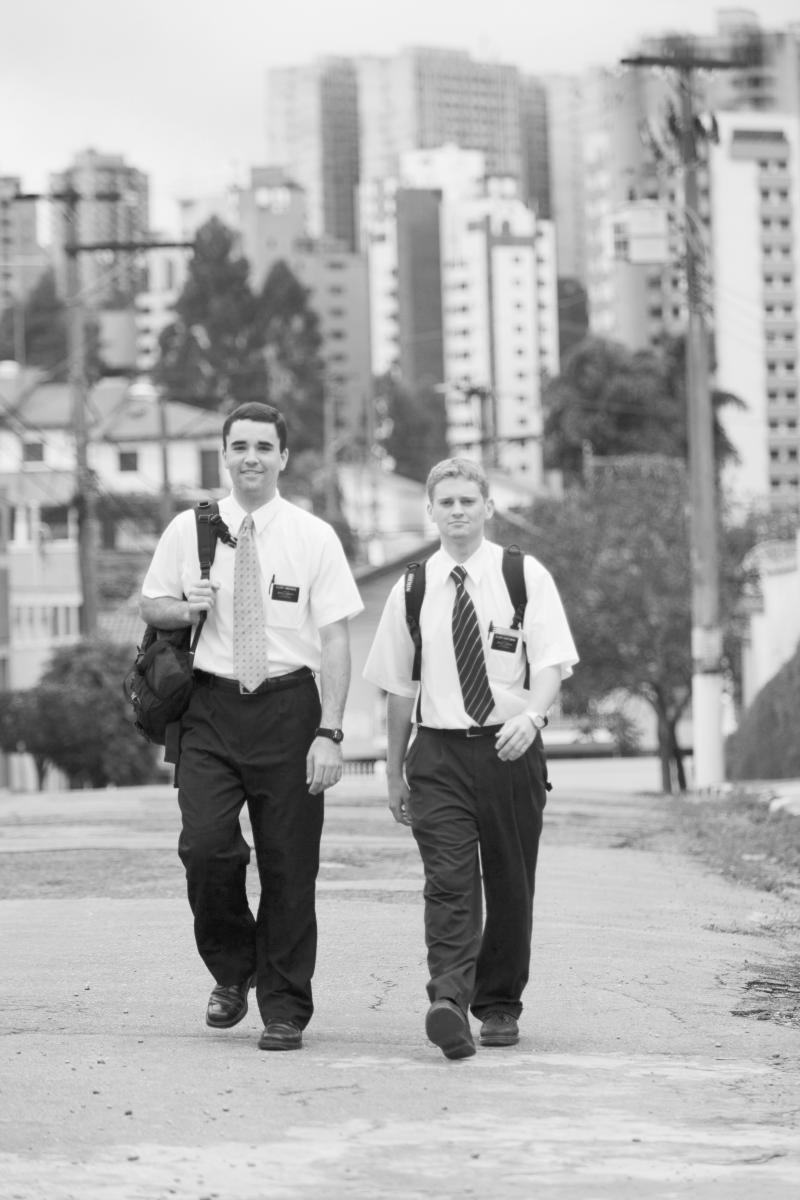

Latter-day Saint missions are filled with young men and women with limited scholarly or work preparation, but they are usually quite well prepared to do what they are asked to do—that is, to preach Christ Jesus and his gospel. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Latter-day Saint missions are filled with young men and women with limited scholarly or work preparation, but they are usually quite well prepared to do what they are asked to do—that is, to preach Christ Jesus and his gospel. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Many authors have written one-volume histories of the world, and quite a few have written one-volume histories of the Church. However, only a small number have written one-volume histories of Latter-day Saint missionary work. One reason for the latter fact is that the history of the Church and the history of its missions are almost totally integrated. Unlike the missions of most other denominations, in which missions and missionary work are a specialized branch of church service, Latter-day Saints are all involved: “Every member a missionary,” at least theoretically.

Our missions are filled with young men and women with limited scholarly or work preparation, but they are usually quite well prepared to do what they are asked to do—that is, to preach Christ Jesus and his gospel of faith, repentance, baptism, reception of the Holy Ghost, and enduring to the end. In addition to our young missionaries, we also have, and have had from the early days of the Restoration, mission presidents with mature understandings of the gospel and of humankind. These men and their wives usually have a cultural understanding of the peoples whom they serve as well as the parental understanding and wisdom to guide their young charges. [1]

There are many distinguishing features in the Church’s way of doing missions. Probably the most important observation I can make is that we do it our way, the way the Lord has instructed. The Church’s approach has some resemblances to the Protestant and Roman Catholic ways of doing missionary work, but from 1830 on, our missionary work has been done without other churches’ models.

Using Joseph Smith as his instrument, the Lord created his missionary system early in the Restoration. As prescribed by revelation, the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles make up the Missionary Committee of the Church. Virtually everything regarding missionary work flows down from this committee. The Prophet Joseph received many revelations regarding missionary work and its urgency. In the very first verses of the first section of the Doctrine and Covenants, the Lord proclaims his mission and purposes: “Hearken, O ye people of my church, saith the voice of him who dwells on high, and whose eyes are upon all men; yea, verily I say: Hearken ye people from afar; and ye that are upon the islands of the sea, listen together. For verily the voice of the Lord is unto all men, and there is none to escape; and there is no eye that shall not see, neither ear that shall not hear, neither heart that shall not be penetrated. . . . And the voice of warning shall be unto all people, by the mouths of my disciples, whom I have chosen in these last days” (D&C 1:1–2, 4). The first section also speaks of the “weak things of the world” coming forth to break down “the mighty and strong ones” and the gospel being “proclaimed by the weak and the simple unto the ends of the world” (D&C 1:19, 23). Because “every member [is] a missionary,” all of us—“the weak and the simple”—have a duty as Latter-day Saints to spread the gospel. Our modern scriptures are filled with missionary admonitions. How often we find words such as “go forth,” “open your mouths,” “serve him with all your heart, might, mind and strength,” “exhort,” “declare,” “preach,” “teach,” “testify,” “warn,” and so on (D&C 1:5; 33:8; 4:2; 19:37; 43:15; 88:81).

Our missionary system is founded on principles that are based on revelation. Over the years, policies and procedures have varied a great deal. For example, during the first several decades of our history, most missionaries were married. They usually served for an indeterminate period of time or for “a season.” Often they served alone, with numerous examples of such elders serving alone in India, Burma, Siam, Hawaii, and elsewhere. So policies and procedures have changed over time. Teaching methods have been developed, refined, and modified. Even the nature and extent of the burdens and responsibilities of mission presidents over missions and within missions have changed considerably. But these changes have occurred within the bounds of revelation from the Lord and his inspiration to the Missionary Committee of the Church.

Whenever someone tries to boil history down to a few summary statements, there is a major danger (actually an almost perfect probability) that something very important will get left out. Even so, it is useful to divide the history of our missions into two long periods: old missions, from 1830 to 1970, and new or contemporary missions, from 1951 to the present. First of all, it is important to note that “old” in this case does not imply an old and entirely outdated message. After all, the first missionaries used the Book of Mormon as their religious tract. What “old” refers to is the organization of missions and the administration of the Church and not necessarily the doctrine and principles that missionaries taught. Also, note the nineteen-year overlap between old and new missions; this was President David O. McKay’s presidency. In actuality, there is no break between the old missions period and the new missions period. In 1951, David O. McKay became President of the Church, but he and most of his juniors had been part of the Missionary Committee for decades. During the 1950s and 1960s, there was a confluence of inspiration and opportunity; we will return to what happened during the McKay years later in this discussion.

The history of Church missions can be seen as an upward-shooting arrow that is crisscrossed by periods of expansion and contraction caused by external forces such as wars, depressions, demographics, international relations issues, government problems, and so on. These forces sometimes affected the entire Church (macro-forces) and sometimes only one mission area or region (micro-forces). Examples of macro-forces would be the Martyrdom of the Prophet, the Utah War of 1857–58, the Mountain Meadows Massacre (1857), the Great Depression of the 1930s, and World War II (1939–45). Examples of micro-forces would include Hawaii in the 1850s and 1860s, Tonga in the 1920s (as will be discussed later in this chapter), and Switzerland today. [2]

The period from 1830 until mid-1844 was a period of heady, even bold, expansion. Despite devastating problems in Ohio and Missouri, the missionary thrust was generally upward. The average number of missionaries called from 1830 to 1844 was 127 per year. The Church grew from a small number of members on April 6, 1830, to 26,146 members at the end of 1844. [3] Successful missionary work was being done in the British Isles, and the Church’s first foreign-language mission was under way in what is now called French Polynesia. Most of the 26,146 members were converts, not children of record.

The second half of 1844 began a six- or seven-year period of missionary contraction. The average number of missionaries called from 1845 until 1851 was fifty-two per year. But surprisingly, the total number of Church members more than doubled to 52,165 during this period. Another fact that almost seems counterintuitive to the contraction of missionary work is that in 1850, the Church opened missions in the Sandwich Islands, Scandinavia, France, Italy, and Switzerland. Just think about it: The Martyrdom of Joseph and Hyrum took place in June 1844. The Nauvoo Temple was more or less completed in January 1846, but the majority of the Saints were driven out of Nauvoo in February 1846. The Saints suffered their way to Winter Quarters and endured countless hardships. In 1847, they began settlement in Great Salt Lake Valley and proceeded to regroup. Despite these significant challenges, missionary work went forward.

From the perspective of mission history, the year 1852 is very important. For a five-year period, we again see the quest for expansion. The boldness of Church leaders at the time again deeply impresses me. Only five years after the Saints began to settle in the Salt Lake Valley, the Brethren called a special conference that was held August 28–29, 1852. This event is well remembered because it was then that the Church came into the open about polygamy. But this conference was one of the great missionary moments. Can you imagine men such as Richard Ballantyne, founder of the Church’s Sunday School program, sitting next to his wife, Hulda, in the Bowery hearing his name read out that he was called to serve a mission in Hindustan? He was not alone. Ballantyne and eight other men were called to Hindustan (India), and four were called to Siam (Thailand). Four elders were called to Hong Kong, China. Others were sent to Australia, the Sandwich Islands, Great Britain, and elsewhere. One hundred eight men were sent to almost all points of the compass. A mere twenty-two years after the founding of the Church, the Brethren were seemingly ready to convert the whole world. Unlike their Protestant counterparts, who for several centuries, from the Reformation until the late 1800s, believed the Great Commission to “teach all nations” applied only to the original Apostles, Joseph Smith and Brigham Young knew it was the entire Church’s current obligation to teach every people.

In 1857, a macro-event occurred that brought the missionary thrust of 1852 to a rapid halt. Because of the impending invasion of Albert Johnston’s forces, President Young called all missionaries home. By this time, some missionary efforts, including those in India, Siam, and China, were already closed. But other fields, such as the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii), which had over four thousand members on record by 1854, were left entirely without missionary leadership. The macro-problems in Utah—the Utah War and the Mountain Meadows Massacre—caused many micro-problems elsewhere.

The Hawaii case is an instructive example. In 1854, the Church established a gathering place on the island of Lanai. [4] The colony was already in trouble when the elders departed in 1857, but the absence of authorized missionary leaders allowed the adventurer Walter Murray Gibson to take leadership of the Church in the islands in 1861. He set himself up as “Chief President of the Islands of the Sea and of the Hawaiian Islands” and proceeded to dispense priesthood offices at a cost. He also managed to obtain a title to the lands in Lanai. Because of his inappropriate behavior, he was excommunicated in 1864. Still believing that a gathering place could bless the Hawaiian Saints, President Young authorized the purchase of Laie in January 1865. [5] It would be interesting to know what might have happened if Johnston’s forces had never threatened the Saints in Utah, but such speculation is, of course, moot. What did result, however, is the island gathering place of the Saints called Laie, with its Laie Hawaii Temple, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, and the Polynesian Cultural Center.

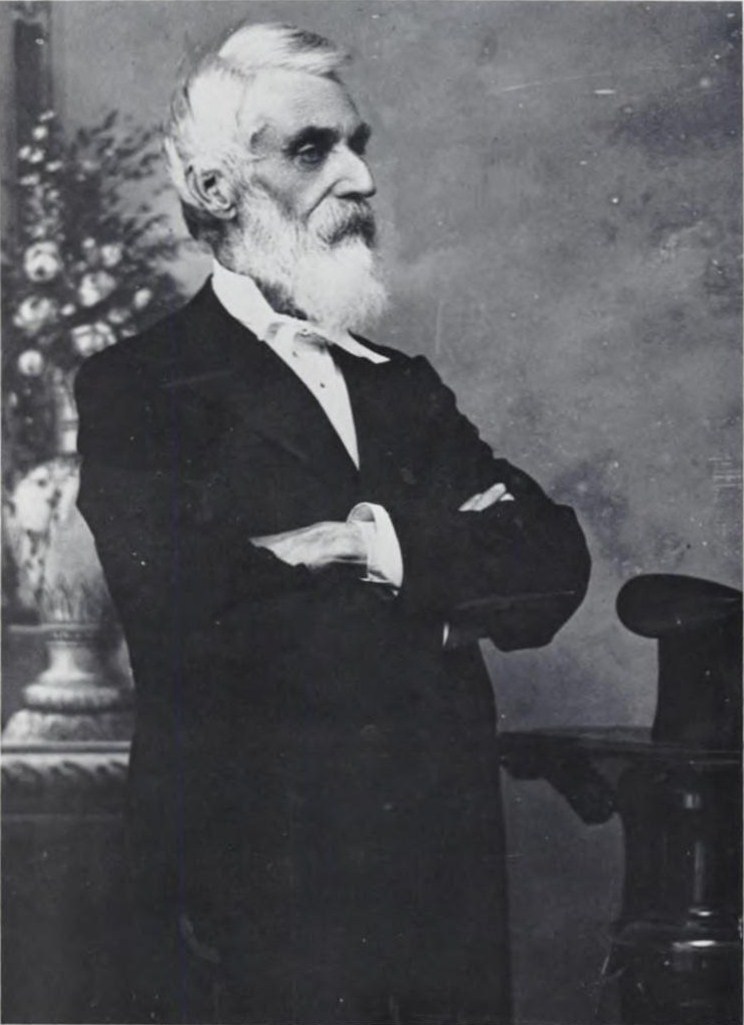

Due to missionaries being called home in response to the impending Utah War, Walter Murray Gibson took advantage of the situation and appointed himself as leader of the Church in Hawaii in 1861. Wikimedia Commons.

Due to missionaries being called home in response to the impending Utah War, Walter Murray Gibson took advantage of the situation and appointed himself as leader of the Church in Hawaii in 1861. Wikimedia Commons.

No missionaries were called in 1858. Although there were years when as many as 250 elders were called, the average number called from 1859 to 1877 was 96. Somehow, during these years of meager missionary numbers, the Church continued to grow. In 1877, the year of Brigham Young’s death, there were 115,065 members on record. I find this very strange. Why did the Church continue to grow? The macro-force, or ongoing problem, during these years and until 1890 was polygamy. But during the years following Brigham’s death and until the Manifesto in 1890, the Church continued to grow. In those thirteen years the Church added 73,198 members. This is the kind of information that makes a missions historian strain for a good explanation. I can only explain this growth by acknowledging the work of the member missionaries (and a lot of fairly procreative large families).

Following the Manifesto in 1890, we see another period of expansion. Between 1890 and 1900, the number of missions almost doubled from twelve to twenty, and the average number of missionaries called each year climbed to 612. In 1899, the number of missionaries sent passed one thousand for the first time (1,059). But it did not stay that high.

The next macro-event was World War I, from 1914 to 1918. While events in Europe had some general effect on the Church in Utah, the number of missionary calls was directly affected. In 1914 and following, Church authorities withdrew missionaries from continental Europe. Then the total number of missionaries fell seriously in 1917 and 1918, to 543 and then to 245, respectively. These kinds of figures tend to emphasize how small the Church was at the time. Every week now, around 580 elders and sisters receive their calls to serve. But in 1918, Church membership still fell short of a half a million (495,962).

A poignant example of a micro-event that resulted from World War I was the near closure of the fledgling mission in Tonga. Beginning in 1918, high-placed anti-Mormon officials in the Tongan government began planning the ouster of the Church from those islands. Eventually, in 1922, the Tongan legislative assembly passed a law making it illegal for Mormons to enter the country. The general content of this law had been approved by British officials in the Pacific (Tonga was a British protectorate) and in London. The mission staff was very small when this law was passed, but because of length of service, financial problems at home, health, and so forth, missionaries continued to return home, leaving many mission posts impossible to operate. The mission president, M. Vernon Coombs, used every avenue open to him to try to bring a change in the law. His letters, personal meetings with officials and people of influence, and petitions finally brought a proposal to repeal the law to the floor of the legislative assembly on July 3, 1924. He had gained enough friends that the repeal vote carried.

As I have written in Unto the Islands of the Sea, this matter concluded as follows:

President Coombs sent a telegram to Salt Lake City informing President [Heber J.] Grant of the good news. On October 25, 1924, Brother Coombs received a letter from the First Presidency congratulating him on the “splendid accomplishment” but informing him of a tentative decision to withdraw missionaries from Tonga. Church leaders in Utah felt that the expenditure of time and money in Tonga was out of proportion to the results obtained. No new missionaries would be sent until a final decision was made.

The next day President Coombs posted a letter to the First Presidency that contained his most profound expressions of affection for the Tongan people and the mission. “But oh, Brethren,” he wrote, “if it is not too late, let me plead for my people. This is the hardest proposition that I have ever faced in my life, and Brethren, I would rather lay down my life for them than to run off and leave them leaderless. They are my people, I have made my greatest sacrifices for them and have used my God-given talents in their behalf; I have bought them with seven years of my youth. I have rejoiced when they have rejoiced and have gone down in sorrow with them. I do not want to persuade you against your better judgment, but if we could have only four missionaries we could, at least, hold our own. . . .”

His arguments had the desired effect. On November 28, 1924, the First Presidency wrote: “We are in receipt of your letter of October 26 containing a very earnest appeal for the continuation of the Tongan mission and have decided that it shall continue.” Missionaries would be sent “at once.”

President Coombs did not receive this letter until February 14, 1925. [6]

This was four months after Coombs wrote his letter and seven months after the exclusion law was repealed. These events in Tonga would not have happened if things had been different in England. There was considerable anti-Mormon opinion in Britain during and following World War I. Government officials in England could have stopped the exclusion law before it was ever brought to the legislative assembly in Tonga, but no problems were anticipated and the law was allowed to go through. Had President Coombs not defended his people both in Tonga and in Salt Lake City, it is very likely that Tonga would not have the highest percentage of members of any nation in the world today. The efforts of one person sometimes greatly affect history.

Moving on, the period of missionary contraction that began during World War I was somewhat relieved during 1925 to 1929, when mission calls topped one thousand for five consecutive years. But another macro-event, the Great Depression, brought a plunge in mission calls down to 399 in 1932. Later in that decade, calls went over one thousand again from 1937 to 1941. But then World War II changed all those numbers. The total number of mission calls from 1942 to 1945 was only 1,717, or an average of 429 per year. Missionaries were withdrawn from Europe and the Pacific in 1939 and 1940. In the South Pacific, only the mission presidents and their wives remained for the war years.

At the end of the war, there were thirty-eight missions worldwide. Missions had come and gone, but the number had slowly edged up over the decades, revealing a continuing desire of the Church and its leaders to reach and teach all people. The immediate postwar years saw rapid increases in mission calls until 1951. The highest number of mission calls to that date came in 1950—3,015. Many young men, including large numbers of World War II veterans, were available and eager to serve. But then the next macro-event came in the form of the Korean War. For two years, missionary numbers dropped. Married men who were Seventies in the stakes of the Church were asked to fill the gap. Some did, and the number of missionaries increased in 1953. My friend Dwayne Anderson, a married man, was called to serve in Japan. He didn’t learn Japanese, because his mission president had him work full-time with LDS servicemen’s groups. He later served as mission president in Japan and did a wonderful work. There were others like him. In 1953, the Korean War ended, and the expansive missionary thrust that started then has continued unabated to the present. Before we discuss the era starting with David O. McKay, however, it is important to discuss some of the characteristics of “old missions.”

I could choose almost any mission in the Pacific as an example of how things used to be done, but I want to focus on President Samuel Edwin Woolley of the Hawaiian Mission. Woolley served as mission president from 1895 until 1919. He was thirty-six when he started, and he was in his sixties when he was released. Although his mission was unusually long, much of what he did was not unusual for pre–World War II mission presidents. Not all mission presidents managed sugar plantations and the community connected with them, but most “old mission” mission presidents had tremendous authority and ecclesiastical power. They were the president of the Church in their missions.

President Woolley, like his counterparts elsewhere, was an extremely hard worker. He was up and off to work every morning at an early hour. He was the luna, the leader of workers on the Laie plantation—both Hawaiian natives and haole missionaries. He negotiated and signed contracts with the Kahuku Sugar Mill. He bought additional lands on which to grow sugarcane. He was responsible for missionary housing in Laie and throughout Hawaii. He supervised the construction of chapels. He supervised the local general store. He assigned missionaries to their areas and companionships. He was the president of district and branch presidents. He conducted district conferences and spoke at them. He approved and often interviewed brethren for priesthood ordinations and often conferred the priesthood. He supervised translation and printing projects. For example, the Cannon-Napela Hawaiian Book of Mormon, Ka Buke a Moramona, was republished in 1905 under his presidency. Woolley gave countless blessings to the sick, discouraged, brokenhearted, lonely, downtrodden, halt, and maimed. He was responsible for Church record keeping and submissions. He guided the language and theological training of new missionaries. He kept Laie Elementary School functioning. From time to time, he had dealings with the government which were usually quite amicable. He presided over Church courts. He watched on with a fatherly eye as his son, Ralph, served as general contractor of the Hawaiian Temple while it was under construction. And he was a husband and father.

Most “old mission” mission presidents in the Pacific did similar things. Just as the Laie Plantation required much of Woolley’s time, school systems in Samoa, Tonga, and New Zealand required much attention from their presidents. Every mission president couple had to be medical practitioners, counselors, psychologists, healers of arguments and hurt feelings, conveyors of good and bad news, and head theologians and defenders of the faith. Some mission presidents were required to give unusual leadership in times of disaster, such as hurricanes and earthquakes. Other mission presidents had other strange responsibilities, such as being responsible for (but not captain of) the eighty-two-foot schooner Paraita in French Polynesia. Other mission presidents had to guide the members to safe financial footings, while other presidents focused on basketball teams, musical groups, or brass bands.

Another mission president responsibility was hosting General Authorities and other visitors. The Hawaiian Saints were blessed to have General Authority visits in 1864 and then regularly from the 1880s on. President Joseph F. Smith lived in Laie for two years in the mid-1880s. President George Q. Cannon visited the islands in 1900 to celebrate the jubilee of the founding of the mission in 1850. Possibly Joseph F. Smith’s most remembered visit to Laie was in May and June of 1915, when he received inspiration to build the Hawaiian Temple. [7] In 1919, President Heber J. Grant and his counselors visited Hawaii to dedicate the new temple. President Samuel E. Woolley was the host for such visits from 1895 on.

Farther south, in Samoa, Tonga, French Polynesia, and New Zealand, General Authority visits were a treasured rarity. Elder McKay visited these islands in 1921. His visits were the stuff of inspiring memories. For example, at the Hui Tau, the great conference in New Zealand, Elder McKay spoke at length in English while his Maori listeners understood his message without an interpreter. But after Elder McKay’s 1921 visit, almost twenty years passed before Elder Rufus K. Hardy of the Seventy, and then Elder George Albert Smith, visited this area in the late 1930s. The next General Authority visit came from Elder Matthew Cowley just after the war.

This discussion has two points: First, the mission presidents and their wives were completely engaged in these special visits. It was their chance to both show off their mission and to gain much-needed counsel on seemingly countless issues and matters. Second, the long lapses between visits allowed the persona of the mission president to expand beyond what any president desired. Essentially, the mission president was like the president of the Church in his mission. This remained true in Hawaii until 1935, when the Oahu Stake was created. But even after that, all of the outer islands were under the mission president until stakes were created on those islands in the 1960s and 1970s. In the South Pacific, stakes were organized in New Zealand in 1958, Samoa in 1962, Tonga in 1968, and French Polynesia in 1972. But much of every island group remained in the hands of the mission and mission president until well into the era of contemporary missions.

But mission presidents were not the only missionaries serving in the old missions. In my view, the missionaries of the old missions were required to be braver, more creative, and more innovative than most elders and sisters today. I must qualify this statement, though. The Church still has many missionaries in economically underdeveloped nations and areas where every day brings physical and cultural challenges. Generally, old mission missionaries also spent fewer hours proselyting and spent considerable time visiting members and learning about local culture, music, and so forth. Often missionaries held branch leadership positions that might, in some instances, have been relinquished and given to local Saints. Realistically, though, many missionaries literally held small groups and branches together. These missionaries were not blessed to have the Anderson-Bankhead plan for teaching investigators or the plans prepared by the Missionary Department starting in the 1960s or in Preach My Gospel. Until 1961, with the exception of a couple anomalies, almost no missionaries received Church-sponsored language training prior to entering their field of labor.

It would be totally incorrect to imply that the overall missionary system was not carefully organized prior to the 1960s and 1970s. But from that time forward, I believe, the Church’s greater numerical size and financial strength have allowed its leaders to do a number of things that were not realistic in earlier decades. Some colleagues of mine have referred to the contemporary missionary system as the “MBA system.” While I do not subscribe to this analysis, I do believe the administration of the system has been more professional during the last fifty years.

But what changed between the old and the contemporary systems, and what remained the same? The things that have remained the same all relate to missionary testimony, willingness to sacrifice for the Church, and the desire of individual missionaries to give their all to create better and more effective ways of teaching the gospel. One thing that impresses me greatly is the way Latter-day Saints take ownership of the missionary program. Since the beginning of the Church, members and full-time missionaries have created countless ways to reach their nonmember relatives and friends. Systematized methods of teaching the gospel were created by missionaries who were eager to be more successful in converting their investigators. This still goes on today. Recently, a friend shared his innovation. He keeps a ward mission computer log of how his non-LDS neighbors are doing: How many children do they have? Does the family need welfare support? Are neighbors calling on them and truly making those people part of their lives? Have they attended LDS Church meetings? He shares all of this and much more by email with the bishopric, the auxiliary presidents, quorum leaders, and others who can make a positive difference. The member innovations continue. How many Mormon blogs are there, for instance?

There are many policies and procedures that changed beginning in the McKay era. Most of these changes relate to more centralization and formalization of missions. Let me list a few: The Missionary Department is a well-organized, smoothly operating institution. [8] One of the reasons the Missionary Department runs so well is due to the increased resources the Church can now direct to it, including financial and human resources. In earlier times, the Church did not have six Seventies who could devote themselves full-time to this office. Now it does. Nor could the Church afford to employ a staff of competent professionals to manage the affairs of the Missionary Department. Now it can.

With an increase in resources, and the centralization and formalization of missions, the presidency of David O. McKay marked a time of significant change in missionary work. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

With an increase in resources, and the centralization and formalization of missions, the presidency of David O. McKay marked a time of significant change in missionary work. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Other important changes beginning in the early 1960s include the formalization of the time when mission presidents begin their service in their fields of labor—July 1 of the year when they take over—and their length of service. Now most mission presidents serve for only three years. Beginning at about the same time was the mission presidents seminar. It is now a well-established pattern to have this three-day meeting each year a few days before the new mission presidents and their wives go into the field. Another change is the seminar each February for new Missionary Training Center Presidents and directors of visitor’s centers. Obviously there was no need for such meetings before Missionary Training Centers existed. In addition, the length of service for regular full-time elders and sisters has been set at two years and at eighteen months, respectively. Prior to this time, missionaries serving in difficult language areas such as Japan, Taiwan, and Hong Kong were asked to serve for three years. This number was later reduced to thirty months, the number of months for speakers of European languages. But now we hardly remember such times. Twenty-four months or eighteen months of service has since been long established. In 1960, the age for young men to enter the mission field was changed from twenty to nineteen. At the same time, the age for young women was changed from twenty-three to twenty-one. In 1959, 2,847 missionaries were called, though the international situation and conscription laws had some bearing on this figure. The next year, the number jumped to 4,706, and in 1961, it jumped again to 5,793, up 2,946 in two years. For my friends and me, these were heady times. We didn’t know we were part of a revolution, but we felt that things were changing—and they were. The number of missionary calls continued to increase, adding around a thousand missionaries a year until 1974.

It was at that same time, 1960, when the Missionary Committee of the Church put forward the first official missionary teaching plan. Before this, there were a variety of systems that had been created in various missions. In Hawaii, we had a seven-lesson plan that I thought was pretty effective. We memorized it and passed off the discussions with our senior companions. Similar work was being done everywhere. But the new series of lessons was more compact and better thought out. Missionary work has continued to grow more effective since that time.

I noted earlier that there were thirty-eight missions in 1945. That number grew steadily; by 1960, there were fifty-eight missions. This growth was largely involved with the human resource factor. As missionaries became available, the Brethren could expand the Church’s outreach. At the same time, President David O. McKay became the most traveled Church President to date. While earlier Presidents of the Church had been restricted in their travel to horses, wagons, trains, ships, and slower aircrafts, after 1960, President McKay flew around the world in jets. The world shrank, and the membership of the Church began to see the whole world as a possible mission. The leaders of the Church became more familiar to the Saints, and the Saints became more familiar to the leaders wherever the Church was established.

Bridging the McKay, Smith, Lee, and Kimball presidencies was the development of another very important part of the mission system—the Missionary Training Center (MTC). It came about partly because of what could be called an accident. The original idea for what later became the MTC came when twenty-nine missionaries who had been called to Argentina and Mexico could not readily obtain visas. While they waited for their visas, they stayed in a Provo hotel and were taught the Spanish language. Gathering missionaries together for training was, of course, not without precedent. Beginning in 1925 the Church operated what was known as the Mission Home (the full title was Church Missionary Home and Preparatory Training School) on part of the space now occupied by the Conference Center in Salt Lake. It consisted of two older homes. Those of us who started our missions there remember the sleeping quarters and classrooms with window blinds that were pulled down, covered with missionary admonitions and scriptures. Before the Provo MTC was opened, the Salt Lake Mission Home expanded into two other locations. These facilities served long and well until being closed in 1978. But during the Mission Home’s last seventeen years, its purposes were being invaded successively by the Missionary Language Institute in Provo; the Language Training Mission (LTM) in Provo, with its extensions in Laie, Hawaii, and Rexburg, Idaho; and finally the Missionary Training Center in Provo. The MTC’s first phase was completed in 1976. From that time on, missionary and language training have been conducted at the Provo MTC and fourteen other MTCs outside of the United States. The MTC experience has greatly enhanced the abilities of missionaries to effectively teach the gospel.

Another change that occurred in the 1960s and 1970s was the development of the Translation Services department of the Church. Prior to that time, many non-English scriptures, tracts, and other published items were prepared in the field as well as by the Missionary Department in Salt Lake. Translation and publication is now focused in Salt Lake and at satellite offices in many nations.

A development that lasted for only about ten years was the Labor Missionary program. Primarily in the Pacific and Asia, many chapels were constructed by men who dedicated two or more years to literally building the Church. The Church College of New Zealand, the Church College of Hawaii (now BYU–Hawaii), and the Polynesian Cultural Center are examples of important projects with lasting influence built by the Labor Missionary program. The program started in Tonga with the construction of Liahona College (high school) in the early 1950s. [9] Through the labor missionary program, the Church on the islands was transformed from a shabby, antiquated church to a modern one that has shone brightly ever since for all to see.

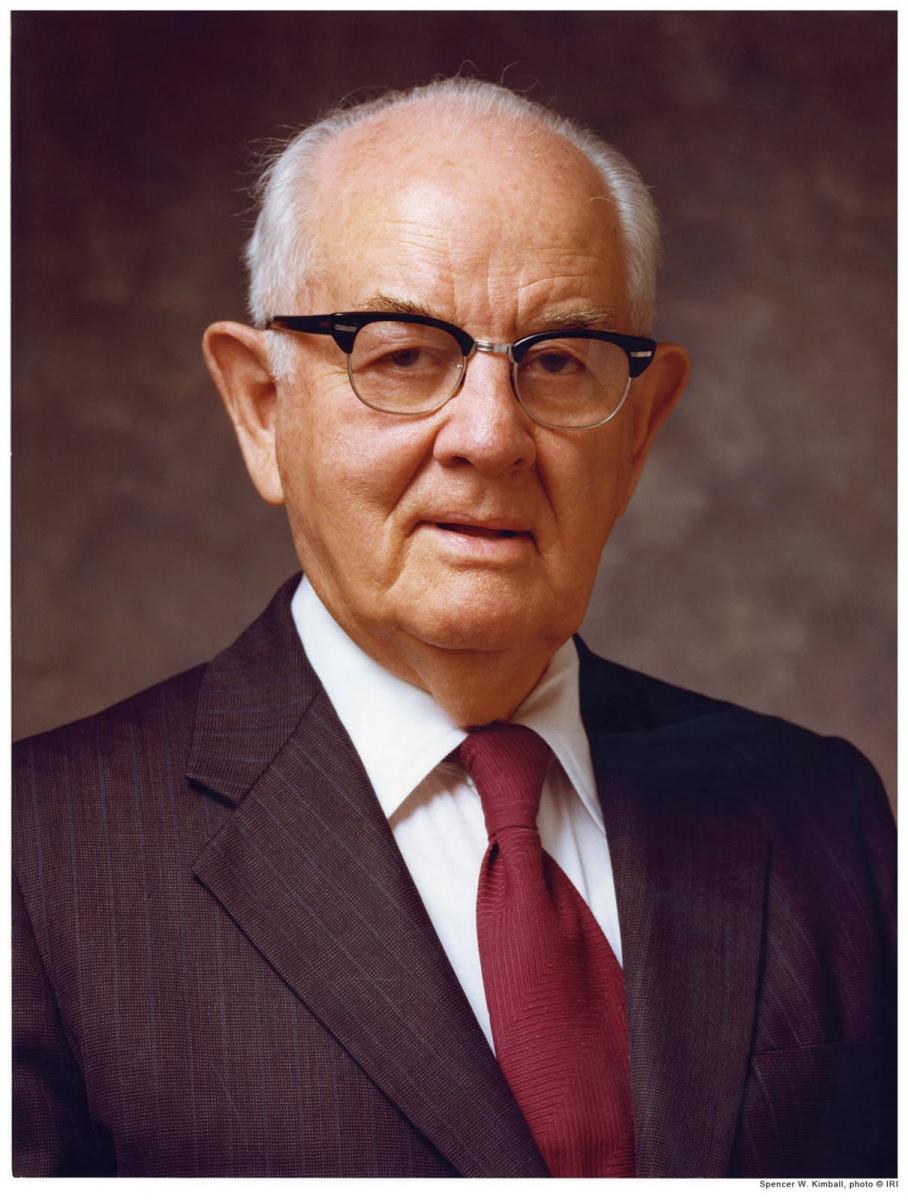

Obviously, the missionary efforts of the Church were picking up steam during the 1950s and 1960s. But something happened in 1974 that unleashed the often latent hopes and desires of Church members everywhere. I will never forget my feelings when President Spencer W. Kimball called us all to greater service. Under his vision, the Church lengthened its missionary stride. President Kimball’s address “When the World Will Be Converted” moved us like no missionary address before. During his presidency (1973–85), total missionary numbers grew from 17,258 to 29,265. The Church quickened its pace. Total numbers of members grew from 3.3 million to 5.9 million. In a way, however, the 3.3 million figure is more significant than the final 5.9 million. President Kimball represented the coming together of vision and opportunity. The Church had reached such a size, such a critical mass, that his call could be heeded in a dramatic way. The saying “Success breeds success” was never truer. Given the fact that the Church has now passed the fourteen-million member mark, it is clear that the subsequent leaders of the Church, Presidents Benson, Hunter, Hinckley, and Monson, have not slackened the pace.

The presidency of Spencer W. Kimball marked a time of rapid growth in total Church membership. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

The presidency of Spencer W. Kimball marked a time of rapid growth in total Church membership. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Among many important developments during President Kimball’s presidency are two changes that greatly furthered the expansion of the Church. First, I want to mention the revelation in June 1978 that all worthy males could hold the priesthood. This change greatly enlarged our ability to go into all the world. Second, the organization of the Seventies as General Authorities and later, under President Hinckley, the creation of Area Seventies, greatly lessened the issue of a cultural gap in the Church. Leadership in the Church has been internationalized. We no longer need to worry about cultural adaptation or misunderstanding in any area of the world where local leaders have been called as members of Area Presidencies.

I titled this address “By All Means” for a reason. In a literal sense, the Church has used every righteous means available to take the gospel to the world. And the ways and means continue to expand. The outreach of the Church through its affiliated institutions and groups is amazing. In an effort to make friends for the Church and to help people everywhere know who the Latter-day Saints are, the Church has sent the Tabernacle Choir and numerous BYU–Provo, BYU–Idaho, and BYU–Hawaii performance tours to many parts of the world. The Church has built a state-of-the-art radio and television broadcast facility at BYU in Provo. This facility broadcasts BYU football and basketball games, as well as other standard programming, to many millions of people. Major athletics are a priority missionary tool for the Church. The Church sponsors the Polynesian Cultural Center (a project of the First Presidency), visitors’ centers, humanitarian programs and projects, the China Teachers Program, family history and genealogy work, and other projects. More direct efforts include up-to-date Internet offerings that are created to teach the gospel and testify through Church leaders and members alike.

I became serious about the study of Mormon missions in 1964, when I wrote my master’s thesis on the 1850s mission of the Church in India. What has amazed me is how much has happened since then. In 1980, I completed a draft of a book on the Church in Asia, but it was not published at that time. In 1995, I got back to that project, and I had to add seven new nations to the story. Missionary history needs constant updating. The Church has boldly pushed onward as more countries have opened for missionary activity. The expansion of the missions has been remarkable. In 1951, when President McKay took office, there were 42 missions and 1.14 million members. As of 2011, there are 340 missions and 14.1 million members. The expansion of membership in the Lord’s Church will continue until it fills every nation and every clime and finds its place in every honest heart.

Notes

[1] Incidentally, Heber C. Kimball became the first mission president when he served in the British Isles beginning in 1837.

[2] The Swiss government refused to grant visas to Mormon missionaries from outside their borders.

[3] Throughout this essay, missionary numbers and total LDS membership figures are derived from the Deseret News 2011 Church News Almanac (Salt Lake City: Deseret News), 189–92.

[4] For more information on this topic, see R. Lanier Britsch, “The Lanai Colony: A Hawaiian Extension of the Mormon Colonial Idea,” Hawaiian Journal of History 12 (1978): 68–83; Fred E. Woods, “The Palawai Pioneers on the Island of Lanai: The First Hawaiian Latter-day Saint Gathering Place (1854–1864),” Mormon Historical Studies 5, no. 2 (Fall 2004): 3–35.

[5] For more information on the history of Laie and Mormonism in Hawaii as a whole, see R. Lanier Britsch, Moramona: The Mormons in Hawaii (Laie, HI: Institute for Polynesian Studies, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, 1989); Riley M. Moffat, Fred E. Woods, and Jeffrey N. Walker, Gathering to Laie (Laie, HI: The Jonathan Napela Center for Hawaiian and Pacific Islands Studies, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, 2011).

[6] R. Lanier Britsch, Unto the Islands of the Sea: A History of the Latter-day Saints in the Pacific (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1986), 444–45.

[7] It has been renamed several times, from the Hawaiian Temple to the Hawaii Temple to the Laie Hawaii Temple today.

[8] For more information, see my chapter titled “Administration and Organization of Missions,” in A Firm Foundation: Church Organization and Administration, ed. David J. Whittaker and Arnold K. Garr (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2011), 595–610.

[9] Actually, the builders there were volunteers. The word missionary was not applied until 1955.