"From the Crossroads of the West"

Lloyd D. Newell

Lloyd D. Newell, “'From the Crossroads of the West': Eight Decades of Music and the Spoken Word,” in , ed. Scott C. Esplin and Kenneth L. Alford (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, Salt Lake City, 2011), 305–322.

Lloyd D. Newell is a professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University.

Mormon Tabernacle Choir and Orchestra at Temple Square in the Salt Lake Tabernacle. (© Intellectual Reserve, Inc.)

Mormon Tabernacle Choir and Orchestra at Temple Square in the Salt Lake Tabernacle. (© Intellectual Reserve, Inc.)

We have in our home a gift from my mother, an old upright Philco radio that she listened to as a young girl on the family farm in Central, Idaho. It belonged to her parents, my grandpa and grandma Lloyd, and is a cherished heirloom. Even with its antique tubes and wiring, it still works. Its wooden frame is smooth and surprisingly unmarked for all the history it embodies. Only the station identifier for Salt Lake City radio station KSL is missing, perhaps from repeated use. Today the radio is prominently displayed in our home. For me, it is a visual and aural link between the early years of Music and the Spoken Word and today.

My mother told me that on Sundays her family would tune in to KSL and the Tabernacle Choir broadcast of Music and the Spoken Word. In my mind’s eye, I can see my grandparents, my mother, and her siblings gathered around the Philco in their clapboard farmhouse. The tiny town of Central was far from everything except the slightly larger towns of Grace and Soda Springs, and even they seemed worlds away. So on Sundays, when they could listen to the Tabernacle Choir from Salt Lake City, it was a small miracle. Week after week they invited the familiar strains of Music and the Spoken Word into their home like a trusted friend.

“From the Crossroads of the West, we welcome you to Temple Square in Salt Lake City for Music and the Spoken Word with the Mormon Tabernacle Choir.” These opening words of the broadcast go out today not only to farmhouses in southeastern Idaho but to a weekly audience that numbers in the millions. Some two thousand television, radio, and cable stations in many parts of the world carry Music and the Spoken Word, which has become the longest continuously broadcast program in the world. Besides bringing this little taste of Salt Lake City into living rooms throughout the world, the broadcast has also brought the world to Salt Lake City. Every week, thousands come to see and hear the choir live and in person, helping make Temple Square the most visited place in Utah and one of the most visited places in the United States. President Gordon B. Hinckley, whose involvement with the broadcast lasted nearly forty years, said, “No medium has touched the lives of so many for so long as has the weekly broadcast of Music and the Spoken Word.” [1] As one of Salt Lake’s most recognizable institutions, the broadcast has been touching lives now for more than eight decades, and it still does so today.

The Beginnings

Radio was a new medium and nationwide phenomenon that fascinated the public during the 1920s and 1930s, broadcasting music, variety, and comedy shows to an audience hungry for entertainment. During the Depression, radio became more than an amusement; it was a source of solace and relief from everyday troubles, if only for a few minutes. Radio also reflected the political and economic tensions of the day. For example, Franklin D. Roosevelt periodically reassured the nation by radio during “fireside chats” in the 1930s and ’40s. Radio was truly in its golden age and at the center of American culture.

In the early 1920s, approximately five hundred radio stations were established by various individuals, businesses, and organizations, creating a “broadcasting boom.” [2] All across the country, people began to recognize radio’s tremendous possibilities—and Salt Lake City was no exception. Leaders of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints saw radio’s potential and encouraged the creation of a Salt Lake City station that today has become a recognized national broadcasting leader.

KSL began in 1922 as a tiny station that broadcast from a tin shed on the roof of a building in downtown Salt Lake. Known then as KZN, an NBC radio affiliate, it was an offshoot of the Church-owned newspaper, the Deseret News. The initial broadcast, which took place at 8:00 p.m. on May 6, 1922, was a message from President Heber J. Grant. President Grant’s counselor, Anthony W. Ivins, said on that occasion, “When the ‘Mormon’ pioneers entered the Salt Lake Valley, in 1847, at which time the Pony Express was the most rapid means of communicated news from one point to another, they little dreamed that before a period of seventy-five years has passed, their children would talk to the world by wireless.” [3] Two years later, thousands of faithful members listened to the first radio broadcast of general conference. The next year, radio listeners in Salt Lake City could tune in to a local program that showcased the Mormon Tabernacle Choir’s Thursday night rehearsals.

It was about this time that KSL station manager and pioneer broadcaster Earl J. Glade had a brilliant idea—a nationwide, weekly broadcast of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir. [4] He first had to convince the choir that it could be done, and then he convinced the management of NBC. It was an ambitious plan to originate a national radio program from a remote and virtually unknown western outpost. Even choir conductor Anthony Lund had his reservations: “We can’t sing with this great choir and have it come over a little kitchen radio.” His concerns about the acoustics were legitimate—how would the choir’s unique sound, which reverberates so beautifully in the cavernous Tabernacle, come across on radio speakers? To address these concerns, KSL’s technicians hung a massive red curtain in the Tabernacle and covered the first ten rows of benches with old carpet from the station’s offices. [5] With those audio problems addressed, KSL’s newest radio program was ready to begin, though it is unlikely that anyone with KSL or the choir foresaw the magnitude of what they were starting.

First Broadcast, July 1929

The first broadcast of what would become known as Music and the Spoken Word took place on Monday, July 15, 1929, at 3:00 p.m. in the Tabernacle on Temple Square. On that hot summer afternoon, KSL ran a wire from its control room to an amplifier more than a block away in the Tabernacle, where the only microphone KSL owned had been suspended from the Tabernacle ceiling to capture the sound of the choir and organ. Nineteen-year-old Ted Kimball, son of organist Edward P. Kimball, climbed a fifteen-foot stepladder to speak into the microphone and announce the songs. NBC headquarters informed a KSL engineer by telegraph when to start the program. Hand signals to Ted Kimball marked the cue to begin. The microphone was live throughout the broadcast, and Ted stayed perched on the ladder for the duration of the broadcast. Ted approached the task “with some trepidation.” He later recalled, “[My father] was more concerned with the job that I would do than he was with his own part [as organist] in the broadcast.” [6]

The choir began its broadcast with “Gently Raise the Sacred Strain,” a hymn written in 1835 that still opens the broadcast today. The first program included six selections:

Chorus from Die Meistersinger, by Richard Wagner

Sonata in B-flat Minor, first movement, by Boslip

“The Morning Breaks,” by George Careless

“An Old Melody,” arranged by Edward Kimball

The finale from Elijah, by Felix Mendelssohn

“The Pilgrim’s Chorus” from Tannhäuser, by Richard Wagner

From the first time Music and the Spoken Word was sent out over NBC’s thirty-station network, the program was favorably received, although some technical difficulties and a line hum caused some of the stations to cut off the debut broadcast early. By the next week, the technical problems had been resolved, and the program was on its way to making broadcasting history. On July 23, 1929, a telegram was received from M. H. Aylsworth, president of NBC: “Your wonderful Tabernacle program is making great impression in New York. Have heard from leading ministers. All impressed by program. Eagerly awaiting your next.” The program was off and running. The New York City Telegraph gave this praise: “Somewhere in the world there may be more than one brilliant choral organization other than the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, but there is no broadcasting in America today to equal the one that comes from the air over the National Broadcasting System.” [7]

The broadcast continued for three years on the NBC network, with the time and day varying from week to week. In 1932, despite efforts by NBC to retain Music and the Spoken Word, KSL switched to the new CBS Radio Network when CBS President William Paley offered to carry the weekly nationwide broadcasts of the Tabernacle Choir on a regular Sunday morning time slot. [8] On September 4, 1933, the broadcast began its Sunday morning run and remains to this day the longest continuous network broadcast in history.

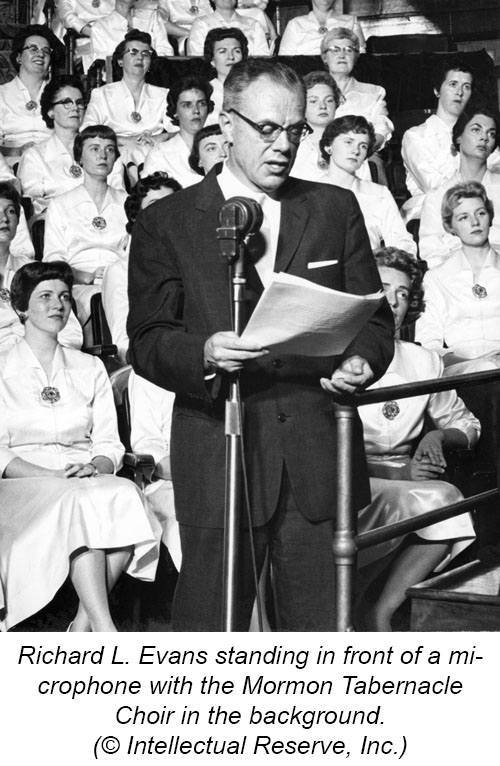

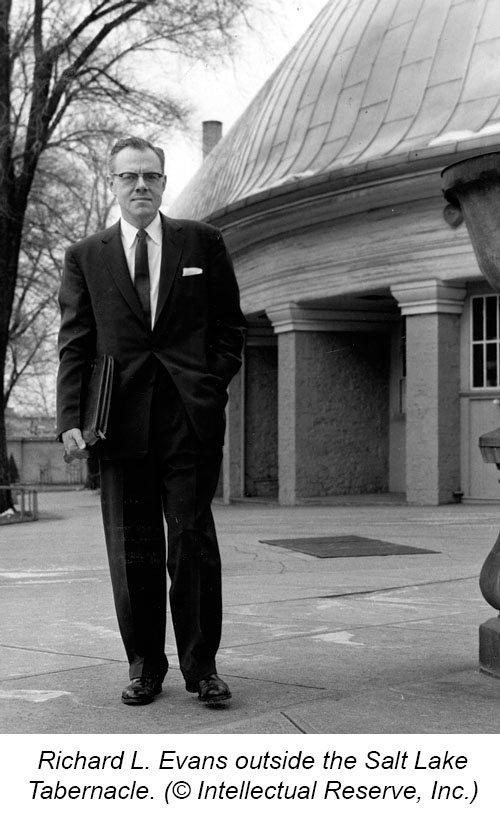

Ted Kimball announced the first few broadcasts and then left to serve a full-time mission. Several other announcers followed until June of 1930, when a twenty-four-year-old announcer from KSL, Richard L. Evans, was chosen to announce the music for the program. Over the next forty-one years, he and the choir would bring unprecedented fame both to Music and the Spoken Word and to its home in Salt Lake City, the “Crossroads of the West.” [9]

Richard L. Evans Era, 1930–71

When he began as announcer, Evans simply announced the titles of compositions and gave the station identification, as his predecessors had done. In time, he began to relate the title of a song to some point of philosophy or moral profundity. These short thoughts flowed from the music and evolved into two- to three-minute nondenominational sermonettes. Listeners were so pleased with the additions he made that he began crafting weekly inspirational messages. His trademark sermonettes were known for their simple eloquence and uncommon wisdom.

Evans served as announcer, writer, and producer of Music and the Spoken Word through four decades. His name and voice are forever linked to the broadcast. Truly, he was the individual who created Music and the Spoken Word as we know it today. His indelible contribution is still imprinted on each broadcast. The closing words he wrote many decades ago remain unchanged today: “Again we leave you from within the shadows of the everlasting hills. May peace be with you this day and always.” [10]

Born in Salt Lake City on March 23, 1906, Richard L. Evans was raised by a single mother, his father having died when Richard was just ten weeks old. At his mother’s knee, Richard was taught the principles of the gospel and the importance of strong faith. When he was sixteen years old, an inspired patriarch blessed him that he would have a “bright career,” that he would “stand in holy places and mingle with many of the best men and women upon the earth,” and that he would serve the Lord in “distant lands, travel much and see many wonderful things.” The patriarch also blessed him that his “tongue [would] be loosened and become as the pen of a ready writer in dispensing the word of God and in preaching the gospel to [his] fellow men.” [11] He excelled in school and was the editor of his high school newspaper and yearbook, a champion debater, and recipient of the Heber J. Grant scholarship award.

At twenty years of age, Evans was called to the British Mission, where he served as associate editor of the Millennial Star and wrote the centennial history of the mission. [12] Not long after his mission, he got a job as an announcer with KSL Radio and began announcing the Tabernacle Choir broadcast.

These assignments allowed him to develop a close relationship with President Heber J. Grant. On one occasion, Richard spoke with President Grant about his desire to work on a doctorate degree and possibly to pursue broadcasting job opportunities that had opened up to him in several large eastern cities. When he asked President Grant’s advice, the prophet “looked at him with a twinkle in his eye and said, ‘I think I’d stick around if I were you.’” And so he remained in Salt Lake City. [13] Richard’s brother commented that “as his life unfolded, Richard recognized that . . . the President’s advice had changed his whole life—and for the better.” [14]

At age thirty-two, Evans was called by President Grant to become a member of the First Council of Seventy. After Elder Evans had served in that position for fifteen years, President David O. McKay announced Richard’s name at the October 1953 general conference as the newest member of the Quorum of the Twelve. After a sustaining vote, President McKay introduced Richard by saying, “Elder Evans whom you know and have known because of his work on the radio and his service in the stakes, and whom the entire nation knows,—Richard L. Evans,—will now speak to us.” [15]

As a special witness of Jesus Christ to the world, Elder Evans would take on new and demanding activities and assignments. All the while, he would remain the voice of Music and the Spoken Word, rarely missing a broadcast, still producing it, and writing and announcing its weekly message.

A year after Evans call to the Twelve, to commemorate the choir’s twenty-fifth year of weekly broadcasts, Life magazine summarized the program’s legacy with these words:

Those who know this program…need no arguments for listening to it, or no introduction to its producer and commentator, Richard L. Evans . . . or to the disciplined voices. . . . Millions have heard them, and more millions, we hope, will hear them in years to come. It is a national institution to be proud of, but what matters more is that Americans can be linked from ocean to ocean and year to year by the same brief respite from the world’s week, and by a great chord of common thoughts on God and love and the everlasting things. [16]

In 1959, Music and the Spoken Word was voted America’s most popular classical and religious program in a national listeners’ poll. Elder Evans understood the tremendous power of broadcasting and other media to shape opinions and spread goodwill, so he worked tirelessly to share these gifts with a broader audience. With others, he was instrumental in bringing Music and the Spoken Word to a television audience in 1962.

Elder Evans was also busy with civic affairs, most notably with the Rotary Club. Over three decades, he rose from local offices to become president of Rotary International in 1966. During that year, he and his wife addressed audiences in sixty countries and in twenty-five states in the United States. It would be impossible to calculate the goodwill he generated as he traveled, spoke, and met with dignitaries and officials from around the world. Elder Evans’s service in Rotary International helped countless individuals become better acquainted with the Church, with Salt Lake City, and with the choir’s broadcast. In 2006, Rotary International held its annual worldwide convention in Salt Lake City, bringing many thousands of visitors to Utah. Several speakers mentioned Richard L. Evans, and the president of Rotary International told me personally that many members still have fond memories of Richard L. Evans and his distinguished service to Rotary. [17]

Elder Evans’s death was unexpected. He was only sixty-five years old when he died just after midnight on November 1, 1971, in Salt Lake City. Elder Evans worked vigorously, as usual, up to his final days, when he became ill from a viral infection. Just before he died, he lay in his hospital bed when the Sunday morning broadcast of Music and the Spoken Word, which had been recorded previously, began. His voice and words, on nationwide broadcast, encouraged faith in the future: “There are times when we feel that we can’t endure—that we can’t face what’s ahead of us . . . that we can’t carry the heavy load. But these times come and go . . . and in the low times we have to endure; we have to hold on until the shadows brighten, until the load lifts. . . . There is more built-in strength in all of us than we sometimes suppose.” [18]

Upon his death, the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles issued a statement to commemorate his life and contributions:

Numerous people the world over have happily boasted that “Richard Evans is my church.” For forty-two years, under intense pressures, Elder Evans has returned to the microphone nearly every week with a message of depth and faith and freshness and inspiration.

As limitless approaches are made with the people all over the world by missionaries and others of us, we are greeted with the statement: “I listen every Sunday morning to Richard L. Evans.” This apostle touched the hearts of millions. [19]

At the opening of the April 1972 general conference, President Harold B. Lee, First Counselor in the First Presidency, extended cordial greetings and then spoke of one who was missing:

It is with subdued hearts that we remember our beloved Richard L. Evans. His voice, his spirit, and his admonitions and counsel were one of the highlights of his association as a General Authority of the Church. Richard L. Evans didn’t just belong to the Church; he belonged to the world, and they claimed him as such. We know that there are heavenly choirs, and maybe they needed an announcer, and one to give the Spoken Word. If so, maybe the need was so great that he is called to a higher service in that place where time is no more. [20]

President Lee’s words must have comforted those who had been mourning the death of this remarkable man. They also highlight the breadth of his influence. Salt Lake City claimed him as its own, but he truly belonged to the world. Through his church, civic, and broadcast work, he brought the world to the Crossroads of the West. Now, decades later, people from around the world continue to visit Salt Lake City each Sunday morning, and some of this can be traced back to the extraordinary work of Richard L. Evans.

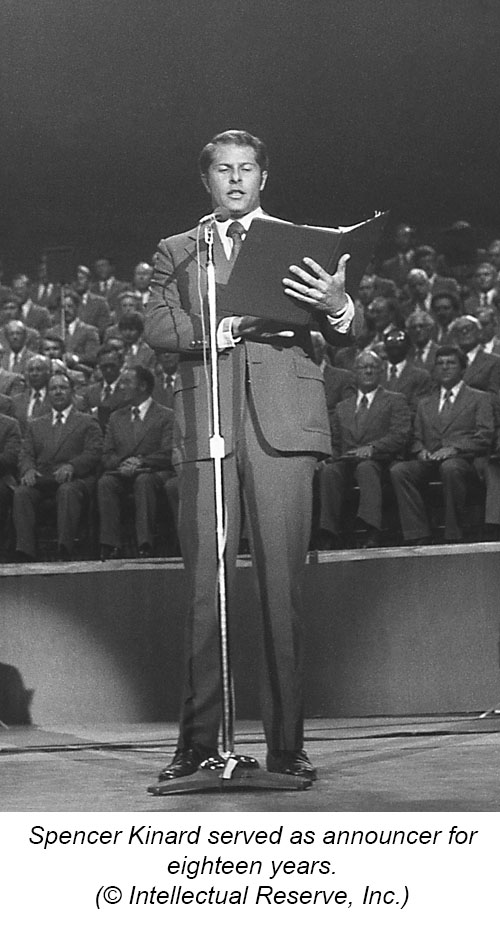

Spencer Kinard and the Spoken Word, 1971–90

As a reporter for KSL Television, in November 1971, J. Spencer (Spence) Kinard was assigned to cover the funeral of Richard L. Evans. Ironically, he was also determined to break the story of who was going to replace Richard L. Evans as announcer of Music and the Spoken Word. Several months earlier, Spence Kinard had moved to Salt Lake City after working with CBS in New York. Meanwhile, Alan Jensen, a man who had substituted for Richard L. Evans from time to time, continued to announce the weekly broadcast on a temporary basis.

In February 1972, President N. Eldon Tanner called Spence Kinard to be the new announcer for Music and the Spoken Word. The following Sunday, Kinard received a blessing from President Tanner, was introduced to the choir, and began the weekly announcing assignment. President Tanner encouraged him with these words: “Spence, we don’t want you to start over; we want you to pick up where Richard Evans left off.” [21] It was a frightening thought for the thirty-one-year-old announcer. He knew he could not fill Richard L. Evans’s shoes; he could only do his personal best, relying on inspiration and divine help.

Kinard recalls, “I was reporting murder and mayhem Monday through Friday and preaching peace and love on Sunday.” That changed a few months later as Kinard was promoted to be news director of the ever-growing KSL television station. The daunting part of the choir broadcast, he soon realized, was “not the delivery, but the content. What to prepare? What to write? What to say?” [22] For the first few years, Kinard, like his predecessor, continued to write the spoken word message every week, and then the inspired idea was born to invite other writers into a rotation and to turn production over to Bonneville Communications. [23]

As broadcast outlets expanded across the country during Spence Kinard’s eighteen years of service, more stations began to carry Music and the Spoken Word. Meanwhile, the program continued to receive awards and strengthen its reputation as a national treasure.

Lloyd D. Newell and the Choir Today, 1990–Present

In October 1990, Spence Kinard resigned from his position as announcer of Music and the Spoken Word, and I was asked by choir president Wendell Smoot to fill in for him “until further notice.” In the meantime, the position was opened for Churchwide auditions. Hundreds of people applied, and more than seventy-five formally auditioned in front of the camera in the Tabernacle. All the while, I continued to do the weekly announcing. In January 1992, based on the recommendation of the search committee and a final decision by President Hinckley, I was officially called and set apart as the “voice of the Spoken Word and announcer for the Tabernacle Choir.”

People both within and outside the Church are often surprised to find out that this is not my full-time job—it’s my Church calling. I occasionally receive letters to “Reverend Newell” at addresses such as “Church of the Crossroads of the West”—and my two predecessors received similar letters. I explain that, like members of the choir, I serve as an unpaid volunteer and that our program is meant to inspire and uplift through music and message. This is not our “worship service”; it’s not a sacrament meeting. It’s an inspirational program of music and message to feed a spiritually hungry world. Frequently, it prompts a desire for more information about who we are and what the teachings of the Church are; always, it creates goodwill and builds bridges of understanding, respect, and appreciation.

In addition to the weekly broadcasts, I accompany the choir as it travels to sing in concert halls throughout the world, as my predecessors did. Although Salt Lake City is the home of the broadcast, Music and the Spoken Word has also been broadcast from various other halls at locations from San Diego to New York City and more than a score of U.S. cities in between. The broadcast has also originated from World Fairs around the world, including Montreal, Toronto, San Antonio, Seattle, and Chicago. It has even been sent over satellite from many locations outside the United States, including Mexico, Germany, Canada, England, New Zealand, Australia, Hungary, Austria, and Israel. I will never forget delivering the spoken word from the BYU Jerusalem Center on Mount Scopus, overlooking the Mount of Olives; from Royal Albert Hall in London; from the Kennedy Center in Washington DC; or from the spectacular Palau de la Música Catalana in Barcelona, Spain—to name just a few.

Since its first broadcast, the program has run continually for more than eighty years, nearly the lifetime of radio, and has been broadcast well over four thousand times. The choir continues to receive more and more recognition, and has won countless awards. In November 2003, the choir received the National Medal of Arts (the nation’s highest award for the arts) from President George W. Bush in an Oval Office ceremony. In April 2004, in conjunction with its seventy-fifth anniversary, Music and the Spoken Word was inducted into the National Association of Broadcasters Hall of Fame, joining broadcasting legends Bob Hope, Edward R. Morrow, Bing Crosby, Benny Goodman, and Paul Harvey. It is one of only two radio programs to be so inducted, the other being the Grand Ole Opry. It received two Peabody Awards for service to American Broadcasting in 1944 and 1962, and was twice awarded the Freedom Foundation’s “George Washington Award” (in 1981 and 1988). In 1960, the choir won the Grammy Award for Best Performance by a Vocal Group or Chorus with a recording of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.” In 2006, the choir was honored as a Laureate of the Mother Teresa. In late 2007, Spirit of the Season, a Christmas album recorded by the Mormon Tabernacle Choir and the Orchestra at Temple Square, was nominated for two Grammy Awards: Best Classical Crossover Album and Best Engineered Album, Classical. And in November 2010, by a vote of the American listening public, Music and the Spoken Word was inducted into the National Radio Hall of Fame in the “National Pioneer” category. [24]

But perhaps its most remarkable accomplishment is its longevity. In a world so noisy and full of distraction, Music and the Spoken Word is a welcome reprieve, a faithful companion, a trusted friend. This program of music and message “from within the shadows of the everlasting hills” gently reminds its listeners of life’s purposes and the everlasting things.

From the Crossroads

Central to the broadcast, from its earliest days, is the city from whence it originates. Salt Lake City is the home of the choir; it is the home of most of the members of the choir; it is the place where each week thousands gather to see and hear the choir live and in person. Each week I open the broadcast with the words “We welcome you to Temple Square in Salt Lake City” and close it with “Originating with station KSL in Salt Lake City.” It is reasonable to assume that when countless people across the globe think of Salt Lake City, they think of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, and when the people think of the choir, they think of Salt Lake City. When we are on tour outside Utah, everyone in attendance at the concert knows (or learns) that we come from Salt Lake City. For many years some in the media even referred to the choir as the “Salt Lake Tabernacle Choir.” Indeed, the choir and the broadcast, in a real way, are ambassadors that represent Salt Lake City and the Church to the world.

Each week, before Music and the Spoken Word begins, I ask the live audience, “Who is here for the first time?” About two-thirds of the audience—which numbers in the thousands—raise their hands. Week after week, people gather from far and wide to Salt Lake City to see and hear this beloved program live. Through all the ups and downs and twists and turns of the past eighty years, the essence of this beloved broadcast remains the same: inspirational music and messages that lift hearts, comfort souls, and bring us closer to the divine. Listeners who experience this inspiration in their homes around the world feel drawn to “the Crossroads of the West” to experience it in person. Truly, Music and the Spoken Word not only brings Salt Lake City to the world, but also brings the world to Salt Lake City.

Notes

I acknowledge my use of the following books in the preparation of this article: Charles J. Calman, The Mormon Tabernacle Choir (New York: Harper and Row, 1979); Richard L. Evans Jr., Richard L. Evans: The Man and the Message (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1973); and Heidi S. Swinton, America’s Choir (Salt Lake City: Shadow Mountain, 2004). Portions of this article were published previously in Richard L. Evans, J. Spencer Kinard, and Lloyd D. Newell, Messages from Music and the Spoken Word (Salt Lake City: Shadow Mountain and Mormon Tabernacle Choir, 2003). This article is a revised treatment of an earlier article: Lloyd D. Newell, “Seventy-Five Years of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir’s Music and the Spoken Word, 1929–2004: A History of the Broadcast of America’s Choir,” Mormon Historical Studies 5, no. 1 (Spring 2004): 127–42.

[1] Swinton, America’s Choir, 101.

[2] Swinton, America’s Choir, 103.

[3] Quoted in Swinton, America’s Choir, 102. See also http://

KSL (originally designated KZN) began life as the radio arm of the LDS owned newspaper Deseret News. It is Utah's oldest radio station. KZN’s first broadcast came on May 6, 1922 in the form of a talk by then-LDS Church president Heber J. Grant. In 1924, it changed its call letters to KFPT, and then adopted its current call letters, with their association to Salt Lake, in 1925 after they became available (they had previously been used by an early radio station in Alaska). Earl J. Glade (later a four term Salt Lake City mayor) joined the station in 1925 and guided KSL's operations for the next fourteen years. Power boosts over the next decade brought the station to its current 50,000 watts (daytime broadcast power) in 1932. It broadcast at several frequencies over the years before settling at 1160 kHz in 1941.

[4] Earl Glade was the moving force behind getting the program started and served as its first producer.

[5] See Swinton, America’s Choir, 103.

[6] Quoted in America’s Choir, 102. “The Choir’s 300 members practiced for a month before the first live broadcast, holding a final ‘radio dress rehearsal’ the week before. The chief divisional engineer of NBC called it an ‘epic’ event, with 10,000 radio fans eagerly awaiting the program. In the early broadcasts, the announcer would aim the one microphone in the direction of whichever section was singing at the moment.”

In July of 1999, when we celebrated the seventieth anniversary of Music and the Spoken Word, we used an early microphone much like the one used during the first broadcast. Speaking into this mike—one that was used by Richard L. Evans for many years—was a thrill I will not soon forget. As it turned out, television personality Oprah Winfrey was in the audience that Sunday and came up after the broadcast to speak briefly to the choir. She thanked them for inspiring her and said that she grew up listening to the choir. Having a famous broadcast personality in the Tabernacle, in awe of the choir, on the Sunday we were commemorating seventy years, is a memory to long cherish.

[7] Quoted in Swinton, America’s Choir, 104.

[8] The CBS radio network and its affiliates began to air various choirs over the radio airwaves in the 1930s, among them the “Wings Over Jordan” choir. In addition, other radio stations began to air the Metropolitan Opera, the Grand Ole Opry, and other musical programming. Music and the Spoken Word began as a CBS network broadcast and is still carried over the network today, making it the longest network broadcast in the world.

[9] The Salt Lake City area became known as the Crossroads of the West after the transcontinental railroad connected the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads on May 10, 1869, at Promontory Summit, Utah Territory.

[10] The epitaph on Richard L. Evans’s tombstone in the Salt Lake City Cemetery reads, “May Peace Be With You . . . This Day and Always.”

[11] Evans, Richard L. Evans, 23. lder

[12] The history was subsequently published in 1937 under the title A Century of Mormonism in Great Britain (Salt Lake City: Deseret News).

[13] Evans, Richard L. Evans, 45–46.

[14] David W. Evans, My Brother Richard L., ed. Bruce B. Clark (Salt Lake City: Beatrice Cannon Evans, 1984), 27.

[15] David O. McKay, in Conference Report, October 1953, 128.

[16] In Richard L. Evans, From the Crossroads (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1955), 14

[17] One of Elder Evans’ fellow Rotarians, Lowell Berry, led the push to endow a professorship in Elder Evans’ honor when the Apostle passed way. The Richard L. Evans Chair of Religious Understanding has played a significant role in improving interfaith relationships and reflects the type of outreach that Elder Evans and the Choir have been known for around the world.

[18] In Evans, Richard L. Evans, 85.

[19] “Statements from the Leading Councils of the Church,” Ensign, December 1971, 11.

[20] Harold B. Lee, in Conference Report, April 1972, 3.

[21] Quoted in America’s Choir, 109–10.

[22] Quoted in America’s Choir, 109–10.

[23] Since the 1970s, Music and the Spoken Word has been produced by Bonneville Communications, a division of Bonneville International Corporation, and distributed internationally as a public service broadcast. Bonneville International Corporation is a holding company for numerous broadcast properties and has supported the broadcast since 1964. A wonderful, synergistic teamwork occurs as the choir leadership and Bonneville work together in the production and distribution of the program. Today a few writers are used on a rotating basis once or twice a month; I write the remaining messages, then I oversee and edit each message with the excellent assistance of Ted Barnes of Church editing.

[24] For more information on the choir’s history and accolades, see Lisa Ann Jackson, “From the Crossroads of the West,” Ensign, July 2004, 68–73. See also Terryl Givens’s People of Paradox, Oxford University Press, 2007, chapter 13, which situates the choir in the context of both LDS culture and the broader culture and discusses the public perception and national appeal of the choir.