The Sandwich, or Hawaiian, Islands, May 1895–July 1895

Reid L. Neilson and Riley M. Moffat, eds., Tales from the World Tour: The 1895–1897 Travel Writings of Mormon Historian Andrew Jenson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2012), 35–87.

Since June 1846, when the ship Brooklyn en route from New York to California with a company of about two hundred Saints onboard, touched at Honolulu, the place was figured somewhat prominently in the history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The two hundred and fifty missionaries who have been sent from the headquarters of the Church to labor on the Hawaiian Islands have all landed at and departed from Honolulu excepting those who have not yet returned. Most of the elders en route for the other islands of the Pacific (the Society Islands excepted) as well as New Zealand, Australia, and India have called at Honolulu on their way out and back.

—Andrew Jenson [1]

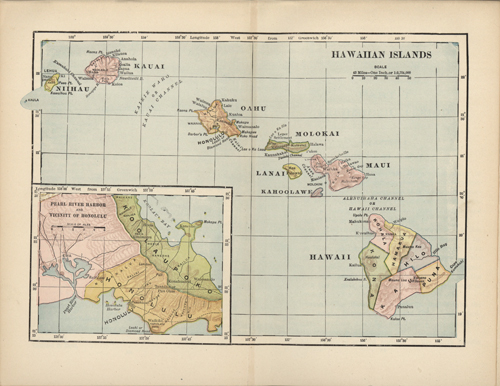

The Hawaiian Islands, W.D. Alexander, A Brief History of the Hawaiian People (New York: American Book, 1899), 12

The Hawaiian Islands, W.D. Alexander, A Brief History of the Hawaiian People (New York: American Book, 1899), 12

“Jenson’s Travels,” May 31, 1895 [2]

La‘ie, O‘ahu, Hawaiian Islands

(Map of Hawaiian Islands from A Brief History of the Hawaiian People by W. D. Alexander, 1899, p.12)

Thursday, May 30. After attending to some writing and business matters in Honolulu, Brother Edwin C. Dibble hitched up the mule team which Elder Matthew Noall had brought over from La‘ie, and took Brother Noall and family and myself out for a ride. This was the American Decoration Day, which is observed here the same as in the United States. I was surprised to see so many Stars and Stripes floating from business blocks and private residences, but was reminded that nearly everything in the Hawaiian nation is patterned after American institutions, and that the new government is in such close sympathy with the United States that a visitor, were he to judge from the spirit and influence surrounding him, might easily imagine himself on Uncle Sam’s domain. [3]

On my arrival at Honolulu yesterday I was somewhat disappointed at the appearance of the place; but as I traveled up and down its principal streets I liked it better and better. The neat, cozy residence of the more wealthy citizens surrounded by fine tropical orchards, the extensive parks, respectable business blocks, government buildings, well-paved streets, and macadamized roads cannot fail to make a favorable impression upon the stranger. The appearance of Honolulu and vicinity, as viewed from the sea, is deceptive as to size and extent, owing to the dense shrubbery growing along the seashore from Diamond Head on the southeast to the Kamehameha schools on the northwest, a distance of six miles. It is after the visitor lands and begins to observe the leading features of the city and the novelty of everything around him that he is struck with the great change from American or European scenery. A wealth of tropical foliage with its brilliant colors and the dwellings with their broad verandas shaded with vines covered with flowers attract attention wherever one goes. There are also stately royal palms, whose trunks are as smooth and round as if they had been turned on a lathe, and carrying in their tops mammoth pinnated leaves twenty and thirty feet long and of proportionate width. The beautiful algaroba with its graceful leaves, fir palms, pepper and eucalyptus trees, and many other kinds of beautiful shade trees are seen on every hand. The fruit-bearing trees are even more numerous. Most of them have been imported from Mexico, South America, and the East and West Indies. Among them are date and coco palms, cherimoyas and mountain apples, mangoes, bananas and pomegranates, tamarinds and breadfruit, the rose apple (producing a delicious fruit of the taste and fragrance of the rose), the avocado pear (transplanted from South America), and many others. Among the great variety of flowers which pleases the eye are magnificent oleanders, fuchsias, geraniums, and morning glories, which, generally speaking, for size and luxuriance eclipse anything of the kind in the United States.

The present number of inhabitants in Honolulu is about 25,000, made up of about 10,000 natives and half-whites; about 4,500 Chinese; 2,000 Japanese; and the remainder Americans and Europeans. The Chinese occupy one section of the city and the Portuguese another, but the bulk of the population live intermixed. Notwithstanding this mixture of races, there has never been much exhibition of race prejudices or jealousies, as is shown by their free commercial and social intercourse. The English language is predominant and strangers familiar with it will find no difficulty in getting along, either on the streets or in the stores.

All the newspapers published on the Hawaiian Islands are published at Honolulu. There are ten or twelve periodicals published in English; some of these are daily, others weekly and monthly. Four or five papers are published in the Hawaiian and two each in Chinese, Japanese, and Portuguese.

The harbor of Honolulu was discovered by the captain of a trading vessel, November 21, 1794, who named it Fairhaven, and Honolulu, in the Hawaiian language has the same meaning. Though small, it is perfectly safe in all kinds of weather, being completely landlocked. Its entrance is through the coral reef which surrounds the islands and is deep enough to admit the largest ships afloat in the ocean.

Honolulu is the capital of the Hawaiian Islands, and the only town of commercial importance in the group. The business part of the city is situated near the harbor, Fort Street being the principal thoroughfare. The private residences, most of which stand in their own gardens, extend two miles up the historical Nu‘uanu Valley, two miles toward the suburban town of Waikiki and two miles westward.

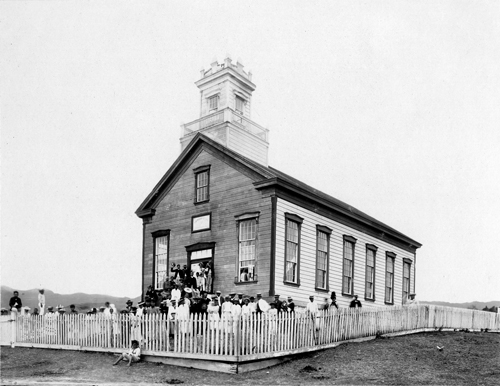

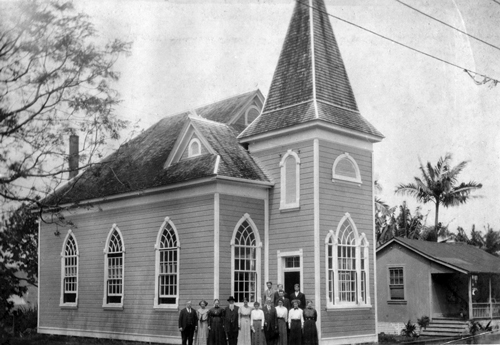

Since June 1846, when the ship Brooklyn en route from New York to California with a company of about two hundred Saints onboard, touched at Honolulu, the place was figured somewhat prominently in the history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The two hundred and fifty missionaries who have been sent from the headquarters of the Church to labor on the Hawaiian Islands have all landed at and departed from Honolulu excepting those who have not yet returned. Most of the elders en route for the other islands of the Pacific (the Society Islands excepted) as well as New Zealand, Australia, and India have called at Honolulu on their way out and back. Nearly all the elders who are appointed to labor on the different islands of the Hawaiian group sail from and arrive at Honolulu as they are assigned to their respective fields of labor from time to time. It is also the common post office address for all our missionaries laboring on the Hawaiian Islands. On the arrival of mails from America, all letters and papers addressed to the missionaries find their way to Box 410, Honolulu, where the president of Honolulu Branch receives them and redirects all mail matter to those of the elders who are laboring outside of Honolulu, he always being posted in regard to their whereabouts. This is done right at the post office without being obliged to pay extra local postage. There has been a branch of the Church in Honolulu since 1853, and at the present time it is the largest branch in the mission, containing as it does about 560 members. Elder Edwin C. Dibble is president. The branch has a fine meetinghouse erected in 1888 under the superintendency of Elder Matthew Noall. The main building is a frame structure, 30x50 feet with a well-proportioned tower on the east end. It stands on Punchbowl Street, about a mile from the harbor. Adjoining it is the missionary’s cottage, with four rooms on the main floor, which has been the temporary home of many an elder in past years, and may do service as such for many years to come.

Honolulu Branch chapel, also known as the "one-eyed church." Courtesy of Brigham Young University- Hawaii.

Honolulu Branch chapel, also known as the "one-eyed church." Courtesy of Brigham Young University- Hawaii.

In our drive today we visited the beautiful suburban town Waikiki, where we called on an old faithful member of the Church called Holika. She is the president of the Relief Society in Waikiki, and during her long experience in the Church she has made the acquaintance of many of the elders from Zion who have labored as missionaries on these islands. She mentioned a number of them, but seemed particularly interested in President Joseph F. Smith, who was among those who have visited in her home. She lives in a native hut with thatched roof, but owns a comfortable lumber dwelling standing nearby, the interior of which she keeps very tidy and clean; the walls are covered with photographs of elders and other Saints. We also visited the Kapiolani Park, lying on the seashore and extending out to the Diamond Point; and returning we drove to the top of Punchbowl Crater, from which a fine view is obtained of Honolulu and harbors, also of the country bordering on the noted Pearl Harbor westward, as well as toward the interior of the island.

The Saints in Honolulu are generally poor, and since the overthrow of the monarchy a great number of them, refusing to take the oath of allegiance to the new government, have been thrown out of employment. Nearly all the natives seem to be opposed in their hearts to the dethronement of the queen, and look upon the whole affair as a treacherous scheme concocted by the “missionaries” and other white adventurers, who have grown rich on the expense of the Hawaiian people in many instances. They look hopefully to the United States government for justice and think that their queen will shortly be restored to the throne and the present temporary government be forced to vacate in her favor. Though everything is quiet and peace reigns supreme at present, it is evident that the troubles are not yet over, nor is the dissatisfaction by any means confined to the natives, but many influential people among the whites—those particularly who failed to become officeholders under the new government—are not in sympathy with the present administration.

Our brethren here are taking no part whatever in political affairs, but they have in many instances suffered under the suspicion that they were in sympathy with the other white people, who pretend great friendship for the natives, but who in reality are their secret enemies. On this account whole branches of the Church have actually withered away or died spiritually; and the elders laboring on the respective islands have had experiences in this connection different to anything had by their predecessors in the ministry. There are numerous instances where natives have resurrected their belief in their ancient gods, at least in part thinking that by this means they may obtain their rights and have their own government reestablished. An effort is being made, so I am told, on the part of the present government and its friends to convince the world that the Hawaiian people are in full accordance with the new government and that the opposition is confined to a few “soreheads” only; but I am fully convinced through information which I have already obtained from the most reliable sources that this is a mistake. The natives generally speaking are opposed to the change of government, and though many of them were not in close sympathy with the queen prior to her dethronement, they condemned in the strongest terms the usurpation, which they think was practiced in connection with the overthrow of the monarchy.

Friday, May 31. I paid a visit to the government buildings in Honolulu, when I had a pleasant interview with Honorable Sanford B. Dole, the president of the Hawaiian Republic. He is a tall, stately gentleman of military bearing and pleasant address. He wears an extra long beard, which has given occasion to numerous jokes on the part of his political opponents. In my interview with him, he declared himself a friend of the Mormons, and having visited the La‘ie Plantation on several occasions, he knew our people to be of a practical and industrious disposition, and wished us success. He only objected to one thing, he said, in connection with our practices, and that was our inducing the natives to emigrate to Utah, and then after their arrival there neglect to care for them, and thereby put the Hawaiian government to the expense of paying their transportation back. I assured him that if any of the natives had been persuaded to go to Utah against their will I was not aware of it; and so far as neglecting them after their arrival, I know this to be a fact that no other class of emigrants had been cared for by the Saints like the Hawaiian people. In the first place the Church has bought a large tract of land on the island of O‘ahu at an original cost of something like $14,000, and this land had for thirty years been worked as a plantation and stock ranch by missionary labors in the interest of the Hawaiian people; and a few years ago also a ranch was bought by the Church in Utah for the special benefit of those natives who had emigrated to the headquarters of the Church, and had ever since been conducted in their interest, under the direction of competent men who had labored as missionaries on the islands and knew how to care for the Hawaiians. [4] If, after all this special care and outlay of means in their behalf, some of them get dissatisfied and wanted to return to their native islands, it must be for other causes. It certainly was not on account of any neglect on the part of the Church or its representatives to care for them. The president seemed pleased with my explanation and expressed a desire to converse with our presiding elder on the islands, as I suggested he could obtain from him full particulars on our missionary operations here better than from me who had just arrived.

At 1:30 p.m. I left Honolulu with a mule team, in company with President Matthew Noall, his wife and three children, bound for La‘ie, thirty-two miles distant. The ride up the beautiful Nu‘uanu Valley was very interesting, and after traveling six miles from Honolulu, we found ourselves on the top of the so-called pali, which is a precipice 1,200 feet high with mountains on either side reaching a height of over 3,000 feet. The view from the top of the pali looking northward is grand beyond description. The ocean can be seen also in looking southward. The road leading down the pali is cut out in the face of the solid mountain most of the way and is very steep. In less than half a mile the traveler drops down over a thousand feet. Both wheels of our vehicle were tied in making the descent and all hands walked down including the mules. Having reached the foot of the mountain the journey was continued in a northwesterly direction along the coast, passing through a number of native villages and one sugar plantation. In three of these villages, namely, Kaneohe, Ka‘alaea, and Kahana, there are branches of the Church. After a romantic ride, part of the way traveling on the sands of the seashore, we arrived at La‘ie about midnight.

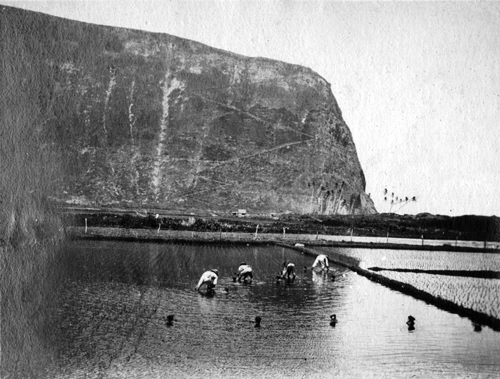

In my travels today, and ride in and around Honolulu yesterday, my attention was continually drawn to new features. Never before having visited a country within the limits of the tropics, I had the pleasure for the first time in my life to see sugarcane fields, rice fields, kalo patches, coconut groves, banana groves, palm trees, breadfruit trees, mango trees, etc., etc., not to mention tropical jungles, and the many varieties of shrubbery, flowers, and grasses which are not met with in a colder climate. But perhaps the most interesting and striking feature of all is the peculiar volcanic formation of the country itself. The almost-perpendicular mountains terminate in ridges so sharp and narrow that it would seemingly be impossible for any one to walk along them even in single file, were it possible to climb to the top. The mountains cover most of the island, the fertile land suitable for cultivation being very limited.

“Jenson’s Travels,” June 3, 1895 [5]

La‘ie, O‘ahu, Hawaiian Islands

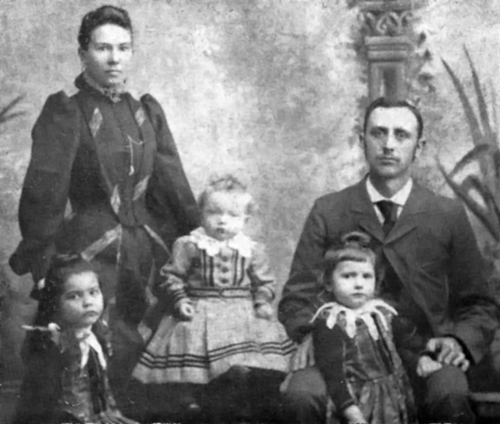

Saturday, June 1. In the morning I was introduced to the missionary brethren and sisters at La‘ie. [6] There were twelve of them besides eleven children, twenty-three souls all told. Their names and positions are as follows: Elder Matthew Noall, (Photo of Noall family) of the 22nd Ward, Salt Lake City, president of the Hawaiian Mission and manager of the La‘ie Plantation; Sister Elizabeth D. Noall, wife of Matthew Noall, mission president of the Relief Societies on the Hawaiian Islands and director of the domestic work of the women’s department of La‘ie; Elder John Brown, general assistant, and Sister Elizabeth S. Brown, wife of John Brown, assistant in domestic duties; Elder Walter Scholes of the First Ward, Salt Lake City, foreman at the plantation, and Sister Phoebe L. A. Scholes, his wife, assistant in domestic duties; Melvin M. Harmon of St. George, Utah, schoolteacher and president of the La‘ie Branch; Sister Alice C. W. Harmon, wife of Melvin M. Harmon, storekeeper; Elder George H. Fisher of Oxford, Idaho, clerk of the mission and president of the O‘ahu Conference; Sister Laura L. Fisher, wife of George H. Fisher, assistant schoolteacher; Elder George H. Birdno of Thatcher, Arizona, traveling elder in the O‘ahu Conference and blacksmith at La‘ie; Sister Ellen C. Birdno, wife of George H. Birdno, assistant in domestic duties. The missionary children’s names are as follows: Vera E. Noall, 9 years old; Nora R. Noall, 7 years; Matthew F. Noall, 5 years; and George L. Noall, 1 year, all children of Matthew and Elizabeth D. Noall; William Wallace, 15 years; Matilda, 12 years; and Jane, 7 years, children of John and Elizabeth S. Brown. Walter A Scholes, two months old, the youngest child at the missionary home, son of Walter and Phoebe L. A. Scholes (he is the last child born at Lanihuli, which is the name given to that particular spot of La‘ie where the mission home is situated). Irvin W. Harmon, 2 years, son of Melvin M. and Alice C. W. Harmon (he was also born on the plantation); Henrietta Johnson, 5 years, daughter of George H. and Laura L. Fisher; Jessie E. Birdno, 2 years, daughter of George H. and Ellen C. Birdno. Young William Wallace is assisting with the cows; the other children who are old enough attend school. Sister Birdno is a daughter of Benjamin Cluff, who labored as a missionary on these islands from 1864 to 1870, having his family with him. While here, two children were born to him, one being Ellen, now the wife of George H. Birdno. She was born on the La‘ie Plantation in a house still standing December 2, 1869. With the exception of Brother Brown, all our missionaries at La‘ie, and in fact all in the mission at the present time, are young people, who are passing through the experiences of their first mission.

Matthew and Elizabeth Noall family. Courtesy of Brigham Young University-Hawaii.

Matthew and Elizabeth Noall family. Courtesy of Brigham Young University-Hawaii.

They are doing well and seem to have the spirit of their calling upon them, most of them also getting along nicely in acquiring the language. Peace and union seem to prevail at the missionary home, and everyone has duties to perform. Prayers are held in the parlor, which is designated as the prayer room, morning and evening. The time for prayers and meals is always announced by the ringing of a bell. All the missionaries take turn in praying, and most of them in doing so use the Hawaiian language. Before the evening prayer a short catechism on the Book of Mormon is had, conducted by the president of the mission. A chapter having previously been selected which the missionaries are supposed to read and study before prayer time, in order to be prepared to answer such questions as may be put to them. Regular missionary meetings are held on Wednesday evenings at which the principles of the gospel, Church history, and other subjects are studied; and testimony meetings are held every Sunday evening. The first Sunday, as well as the first Thursday of each month, is observed as fast day at the missionary home. Elder Noall himself being a hard worker, his example is generally followed by the other missionaries; hence everybody seems quite busy in discharging the different duties assigned them all day long. But at meal hours some little time is spent in profitable conversation, and a few good-natured jokes occasionally pass around in order to dispel the monotony which otherwise might be felt. Considering the inexperience of most of the inmates of Lanihuli, and the different dispositions and temperaments of the several brethren and sisters there, whose lives are thrown so close together, I have nothing but praise for them; they are doing well and are endeavoring to represent the cause of truth in a worthy and consistent manner, and as they get older it is to be hoped they will still become wiser and better and that all of them may throughout all time to come have occasion to look back with great pleasure and satisfaction upon their first mission. When I speak of a first mission, I of course do not include Brother and Sister Noall, who performed a long and very successful mission to these islands from 1885 to 1889 and who arrived here on this their second mission December 18, 1891. They have both acquired the Hawaiian language to a wonderful degree of perfection, and Sister Noall, on account of her proficiency in the language, is sometimes called “the white Hawaiian” by the natives, who are very fond of her and would like her to stay with them forever. No other missionary sister, so far as it is known, has ever learned the Hawaiian language like she has, but it is to be hoped that others will follow her example, and that hereafter our missionary sisters as well as the elders will put forth their best efforts in trying to acquire the language, without which they are necessarily incapable of doing much good among the natives.

Sunday, June 2. This is my first Sunday in the Hawaiian nation. I attended the Sunday School in the La‘ie meetinghouse from 8:30 to 10:00 a.m., their general meeting from 10:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m., after which general testimony meeting in the afternoon and missionary meeting at Lanibuli in the evening. By the assistance of President Noall I addressed the Sunday School and the general meeting at some length. After the meeting the natives crowded around to shake hands with the malahini (“stranger”), and I was greeted with many warm-hearted “aloha nui” (“much love”), to which I soon learned to respond in their tongue. The open, frank countenances and the honest expressions of the eyes which looked into mine when they greeted me made a deep impression upon me, and at once made me feel tenderhearted towards a race which was once highly favored of the Almighty, but who became dark skinned and degraded through sin. May the promises made concerning the remnant of the house of Israel speedily be fulfilled upon this branch thereof! In the afternoon I listened to the natives bearing testimony of the truths they had heard in the forenoon. The speakers were Lalelale, who during his discourse grew quite warm and eloquent; Hiapo‘ole, a home missionary known locally as the native orator; and Moki Nakua‘au, the La‘ie Sunday School superintendent and one of the most intelligent natives on the islands; and the latter’s wife, Kekuewa, quite a refined sister, was the fourth and last speaker. In the evening I addressed the missionaries on the importance of keeping public and private records.

After a preliminary perusal of statistical reports and other documents yesterday, I learn that the Hawaiian Mission embraces all the Hawaiian Islands, and that according to the statistical report of December 31, 1894, it comprises five regularly organized conferences of the Church and two large branches (La‘ie and Honolulu) reporting direct to the president of the mission. The five conferences contain seventy-nine branches, which, together with the two already mentioned, make a total of eighty-one organized branches of the Church in the Hawaiian Mission at the present time. The total membership at the beginning of the present year was 4,048, of which 420 were elders, 144 priests, 142 teachers, 122 deacons, and 3,220 lay members (1,297 males and 1,923 females). Adding 851 children under eight years of age belonging to families in the Church, we have 4,899 as a total number of souls divided into 1,473 families. This represents fully one-eighth of the whole native population of the Hawaiian Islands, as the official census of 1890 showed only 34,436 natives and 6,186 half-castes in the whole kingdom, or 40,622 altogether. In 41 of the 81 branches of the Church in the Hawaiian Islands, there are meetinghouses of which two (those of La‘ie and Honolulu) are fine and commodious structures, and the rest are small lumber or frame houses excepting one or two which are mere native huts with thatched roofs, but they were also built and are now used for houses of worship. There are 40 Sunday Schools in the mission, 39 Relief Societies, and 26 Mutual Improvement Associations for both sexes. At the present time there are 16 elders and six missionary sisters from Zion laboring in the mission. Of these all the sisters and four of the brethren spend most of their time on the La‘ie Plantation. The remaining elders are distributed upon the different islands of the group as follows: Two are laboring as missionaries on the island of Kaua‘i; two on the island of O‘ahu outside of Honolulu and La‘ie; one at Honolulu; three on the islands at Maui, Moloka‘i, and Lana‘i; and four on Hawai‘i. The elders in the missionary field are visiting from branch to branch, generally remaining a week at a time in each branch and spending their time holding meetings with Saints and strangers, visiting from house to house, and studying the language. Their fields of labor are generally changed every six months, or at the general conferences of the mission, which almost from the infant days of the mission have been held in April and October of each year. At those general conferences, which for many years have been held at La‘ie on the island of O‘ahu, all-important business pertaining to the mission is attended to and a good and enjoyable time is almost invariably had by both elders and natives. The conferences are continued for several days, and are generally held on the same dates as the general conferences of the Church in Zion. Those occasions are also made times of general reunions for the missionaries, who as a rule have been separated for five or six months at a time, and occasionally a concert or two is given in addition to the numerous meetings held.

The experience of the elders in these islands is in many ways different to that obtained by our missionaries in any other country where the gospel is being preached by the Latter-day Saint elders at the present time.

The first great difficulty which confronts an elder on his arrival here is the language. There is a similarity between all so-called civilized languages; at least an English-speaking person will find many words that he is acquainted with in his study of the German, French, Spanish, Danish, Dutch, Italian, and many other tongues, the English being a compound of all their languages, and a number of others not mentioned. Hence any of our elders possessing ordinary intelligence and some grammatical knowledge who may be sent to any of the countries of Europe where the languages referred to are spoken would soon “catch on” to many words familiar to him, and this would enable him to feel somewhat at home at once and quickly add to his stock of words. But it is not so with the Hawaiian language. To learn that means the breaking of new ground entirely. Hardly a sound, or even a grunt, seems familiar; at first everything is new and strange, excepting the natural expressions of the face exhibiting joy or sorrow; or to be more plain, the weeping and laughing of the Hawaiian people seems to be done on the same principle and requires about the same effort as that of other mortals. But many of our elders are doing and have always done very well in acquiring the peculiar language spoken here, though it necessarily takes time. No other class of people who have frequented these islands, or who have even become permanent residents here, have made such a record for learning the language as have our elders. This can be accounted for in several ways. First and foremost our elders, if in the line of their duty, have the Spirit of God to quicken their understanding, brighten their intellect, and improve their memory. Then they are, as a rule, men of great determination and willpower; and as their hopes for reward are based upon the sure promises of the Savior, and not upon the uncertain and perishable things of this world, they are willing to work harder, and consequently make better progress, than those who continually stop to consider whether “it will pay or not.” In my own experience as an elder, I have often done things in the interest of the Church of Christ which money could not have hired me to do; and on the same principle our elders as a rule will exert themselves more when they are working for that great boon salvation, which the children of the world call “working for nothing,” than they would if they were being paid for their labors in cold coin or its equivalent.

But while the language is a great detriment to the elder for the first year or so after his arrival, he has advantages which no other mission possesses. At La‘ie, the Church plantation, he has a temporary home—a pleasant home—where he at least once in a while can associate freely with his friends, while he himself is being made comfortable so far as food and shelter is concerned. No other country visited by our elders has missionary headquarters like those at La‘ie. Besides this the Hawaiian people are a very warm-hearted and hospitable people. They make the stranger, and especially those whom they recognize as their friends, welcome to the best they have. And though their bill of fare and sleeping accommodations are not always up to the standard that an American could desire, he is made to feel at home, and as soon as he learns to “eat poi and raw fish” he need not as a rule go hungry while traveling among the natives of these islands.

A geography of the Hawaiian Islands used in the public schools contains the following:

“The Hawaiian Islands are in the North Pacific Ocean. They lie between longitude 154˚40΄ and 160˚30΄ W, and latitude 22˚16΄ and 18˚55΄ N. There are eight islands inhabited, namely, Ni‘ihau, Kaua‘i, O‘ahu, Moloka‘i, Lana‘i, Kaho‘olawe, Maui, and Hawai‘i. Three small islands are not inhabited, namely, Lenua, north of Ni‘ihau; Ka‘ula, southwest of Ni‘ihau; and Molokini, between Kaho‘olawe and Maui.

“The Hawaiian Islands form a continuous chain, running from northwest to southeast. The islands are volcanic formation and contain many extinct craters, while on the island of Hawai‘i are two craters which are active. The soil is fertile in some places, but a large area is unfit for cultivation.

“There are no large rivers, but almost every valley has its rivulet. Showers are frequent on the windward side of the islands.

“The climate is mild and much cooler than places in a similar latitude on any of the large continents. The northeast trade winds blow for about eight months of the year. Southerly winds prevail during the months of November, December, January, and February. These frequently blow very strongly and are then called Kona storms. Thunderstorms are of very rare occurrence and are seldom severe.

“The population of the islands is to be found chiefly along the shores, on a strip of land varying from one to four miles in width. The interior, except in the case of a few deep and fertile valleys, is very sparsely inhabited. The population in 1890 numbered 89,990 people, of which 34,436 are Hawaiians; 6,186 part-Hawaiian (half-caste); 1,928 Americans; 1,344 British; 1,034 German; 8,602 Portuguese; 15,301 Chinese; and the remainder other foreigners.

“The principal industry is the cultivation of sugarcane and the manufacture of sugar. Next in importance is the cultivation of rice. The raising of cattle stands third in the list of industries. Coffee is also raised and bananas as well as other tropical fruits are grown in considerable quantities.

“The Hawaiian Islands extend from northwest to southwest [sic] for a distance of about four hundred miles; hence, it requires considerable interisland travel for our missionaries while performing their duties as elders in this part of the world. But there are regular steamship connections between all the principal islands. The fare however, is very high for first-class accommodations, but only $2 for an adult passenger from island to island for deck passage.” [7]

“Jenson’s Travels,” June 4, 1895 [8]

Lanihuli, La‘ie, O‘ahu, Hawaiian Islands

Monday, June 3. The brethren at the mission house at La‘ie saddled up their horses, which Elders Matthew Noall, Walter Scholes, and myself mounted, and took a long ride over the plantation and along the seacoast. By this means I became acquainted with topographical and industrial features of La‘ie, which property consists of nearly 6,000 acres of land. This was purchased early in 1865 with a view to making it a gathering place for the Hawaiian Saints. It will be remembered that the natives at that time were forbidden by law to emigrate to other countries; and thus being prevented from gathering to Utah like converts from other parts of the world, it was thought best to provide a local gathering place. The property cost $14,000. La‘ie has a coastline of about three and a half miles; the La‘ie landing where steamers occasionally call to take on and unload freight is about a mile and a quarter from Lanihuli, the missionary home. The purchase extends inland for a distance of about four miles, or to the top of the mountains which form the boundary line between the districts of Ko‘olauloa (in which La‘ie is situated) and Waialua. Of the 6,000 acres only about five hundred acres can be classed as level and fertile lands; another five hundred acres is grazing land, consisting mostly of low hills and rolling country; then there is about 2,500 acres of timber or forest mountain land, and nearly the same amount of mountain grazing country. Of the 500 acres tillable land, 160 acres are planted this year with sugarcane; 150 acres are rented to Chinamen for rice fields; 18 acres are planted in kalo, and ten acres in potatoes; and 75 acres are covered by so-called kuleanas (“small lots”) which were owned by natives at the time the purchase was made in 1865. The town site of La‘ie covers about one hundred acres. The mission home called Lanihuli stands on elevated grounds about a quarter of a mile from the center of the village of La‘ie and about the same distance inland from the seashore (nearest point). The premises consists of the new and commodious cottage of modern architecture, one of the finest upon the island of O‘ahu outside of Honolulu—built under the direction of Elder Matthew Noall in 1893. (Photo of Lanihuli mission home) It is a two-story frame building containing nine rooms in the lower story besides hall closets, bathroom, etc., and seven upper rooms, mostly used as sleeping apartments. About 160 feet to the southeast stands the old mission house, which was there in 1865 when the purchase was made; it is now used as a schoolhouse, in which Elder Harmon and Sister Fisher are teaching the English government school. Adjacent to this building is another small cottage occupied by Elders Brown and Birdno and their families, and near the new mission house is a smaller two-room cottage occupied by Brother Fisher and family. Elders Noall, Harmon, and Scholes live with their respective families in the new mission house. During my temporary stay at La‘ie, I will occupy an upper room with a window facing the east from which I have a beautiful view of the coast, the reef, the breakers out in the ocean, also the valley of La‘ie and the steamboat landing beyond. Only a portion of the native population reside in the village; the remainder live on lots and parcels of land at different points of the plantation, some of them as far as two miles away.

Lanihuli mission home in La'ie. Coutesy of Church History library, Salt Lake City.

Lanihuli mission home in La'ie. Coutesy of Church History library, Salt Lake City.

Nearly a quarter of a mile from the mission house stands the beautiful La‘ie meetinghouse built in 1882–83 at an expense of nearly $8,000. (Photo of I Hemolele chapel) It occupies an elevated piece of ground and can be seen to advantage a long distance off. It is known among nonmembers of the Church as the Mormon Temple—a distinction which it perhaps duly deserves, it being the finest house of worship on the island of O‘ahu outside of Honolulu. About sixty yards away to the northwest is the old meetinghouse erected in 1866 soon after the purchase was made; it was used for all public gatherings prior to the erection of the new meetinghouse. Between the meetinghouses and the mission home on one side and the village of La‘ie on the other, lies an open piece of prairie land covered with a beautiful carpet of fine grass called maniania, which served as playground for the children and occasionally for the grown-up natives. This extensive natural lawn is the means of keeping everything clean and pleasant around the mission house as there is no dust flying through the air, though the wind blows at La‘ie almost without cessation. Yes, at La‘ie wind has often been commented upon. It prevents trees and flowers from growing, and the missionary sisters from wearing bangs. Many attempts have been made in former years to raise fruit and shade trees on the La‘ie property; but every trial in that direction has proven a failure so far except in places where they are protected from the wind either by hills or buildings, and then they only grow as high as they are protected. A few trees planted on the shielded side of buildings at La‘ie are proof of this assertion. But while the wind prevents trees from growing on exposed grounds, it is a harbinger of health and vigor to the inhabitants. The air around La‘ie is always good and pure, as it is constantly blown in from the mighty ocean. To inhale it freely means life and renewed strength of mind and body. While the air at times is awfully hot and oppressive at Honolulu, and at many places on the eastward side of the islands, it is always good and pure at La‘ie; the missionaries who, when visiting the capital, are perspiring and feel uncomfortable under the oppressive heat, are always sure to obtain immediate relief when they return to mission headquarters. The town site of La‘ie is laid off like most of our town sites in Utah into regular blocks, the streets crossing each other at right angles, but the natives have not built their houses in conformity to the streets; they seem to face every way as if each builder has sought to make his house face different to that of all his neighbors. Most of the houses rest upon stilts. In their erection the upright timbers have been left long enough to raise the floor several feet from the ground. In countries where unhealthy vapors constantly arise from the ground, such a mode in building would certainly be a great improvement on the present style of architecture. Another peculiar feature in connection with the dwellings on the Hawaiian Islands is the absence of chimneys. In a country where it is perpetual summer there is no need for that particular commodity which is so very essential in a more northern clime.

Hemolele chapel in La'ie. Courtesy of Brigham Young University-Hawaii.

Hemolele chapel in La'ie. Courtesy of Brigham Young University-Hawaii.

There are no continuous living streams on the La‘ie property, though in times of rain there are a number of riverlets and creeks which find their way from the mountains to the ocean, such water being utilized as much as possible for irrigation purposes. But the surface water thus obtained being inadequate, five artesian wells have been sunk on the property, namely three by the plantation company and two by the Chinese, who have rented lands for raising rice. The largest of the plantation wells which is about 300 feet deep, gives forth water at the rate of 469 gallons per minute, through a 7 5/

Considerable stock is kept on the La‘ie Plantation, and of late years the kinds have been greatly improved. There is good grazing during the winter season; but the species of grass growing on the Hawaiian Islands seems to contain so few nutritious properties that cattle and horses who feed in grass knee deep keep poor, the consequence is that even milk is a scarce article on the plantation where they milk sixteen cows. But from all these less than a gallon of milk a day is obtained. I am informed that one good cow properly fed in Utah will give as much or more milk than ten cows on the Hawaiian Islands. Horses and mules on the islands are also poor, except such as are fed on grain and hay imported from California.

To prevent the La‘ie Plantation cattle from straying off onto other people’s property a wire fence three miles long was built recently on the north line of La‘ie, or between that and the Kahuku ranch extending from the sea to the mountains. Four miles more of fence, also built recently, divide the grazing part of La‘ie into four paddocks, or separate pasture enclosures. Material is also on hand for a fence to be built on the other side—on the line between La‘ie and the Kaipapa‘u lands. The sea on the northeast and the mountains on the southwest serve as the best possible fence in those directions.

Cane growing and sugar manufacturing was once a very profitable industry on the Hawaiian Islands, and for years almost every other industry was neglected in its favor, but now the competition in the sugar line is so great that the industry does not pay, unless the cheapest kind of Japanese and Chinese laborers are employed and the best and most modern machinery used in making the sugar, and the article turned out on a large scale. Much of the lands at La‘ie which has been used for raising cane during the past thirty years is now run down to such an extent that it cannot produce good crops any longer; hence some of the lower lands have been discarded, and about sixty acres of new and higher lands taken up, which depend almost exclusively upon mountain streams fed by rainwater to mature the crops. In order to save and utilize the water, quite an extensive reservoir was built in the Wailele Gulch in 1893. A sixteen-foot aeromotor, with a capacity of 10,000 gallons per minute, has also been imported and built for the purpose of raising water from one of the artesian wells onto higher grounds. During the busiest season from fifty to eighty natives are employed on the plantation; their labors are directed by the manager and his assistant or assistants.

Both men and women are employed, and I am specially requested by one of the missionary sisters to record the facts as a point in favor of woman’s rights that the women are among the most faithful laborers and excel many of the men in doing the same kind of work. As an exception to the general rule, but as a true reward of merit, the manager of the plantation has paid for actual work done, and thus the women who work faithfully got higher wages than some of the men.

The old cane mill erected in the days of Harvey H. Cluff has stood idle for about six years. It, together with the blacksmith shop, stands about half a mile south of the mission house.

Our ride along the coast was very interesting to me. A small peninsula extends quite a distance out into the ocean from the grounds on which the village of La‘ie is situated; and there are three small rock islets a short distance out from the shore.

“Jenson’s Travels,” June 9, 1895 [9]

Kahana, Ko‘olaluloa, O‘ahu, Hawaiian Islands

Tuesday, June 4. I commenced my regular historical labors at my temporary home at La‘ie by perusing the mission records and examining old documents on file. It reveals the fact that there are no very early records of the Hawaiian Mission on hand at headquarters. If records of any kind were ever kept from 1850 to 1874, then present whereabouts are not known to anyone here. The earliest genealogical record—that is, a record of baptisms, confirmations, blessings, etc.—dates back only to 1874. There are scraps of history as far back as 1879, but the regular mission record containing minutes of general conferences and statistical matters commences in 1882. Statistical reports are on file since 1886.

Wednesday, June 5. By a thorough perusal of different documents and records I got an insight into the present status of the Hawaiian Islands and mission.

Thursday, June 6. This day was observed as a fast day at La‘ie, and a meeting of the missionaries was held at 11:00 a.m. at Lanihuli. In the afternoon the officers of the Relief Society met in the prayer room and had a splendid little meeting.

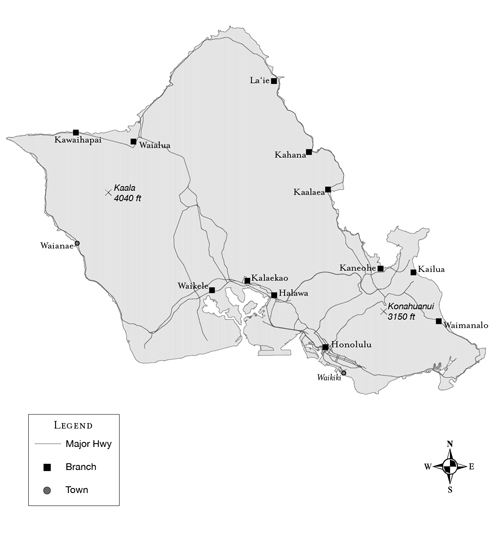

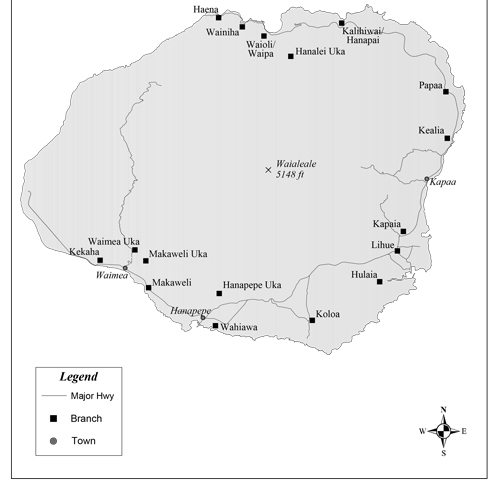

Friday, June 7. Elder George H. Fisher, president of the O‘ahu Conference, assisted me in my historical labors. The O‘ahu Conference embraces all the Saints residing on the island of O‘ahu outside of La‘ie and Honolulu. O‘ahu is the most important island of the Hawaiian group though not the largest. It has an area of 600 square miles. Its extreme length from Makapu‘u Point on the southeast to the Kahuku Point on the northwest is forty-six miles; its average breadth is twenty-five miles, and its population was 31,194 in 1890. In agricultural importance O‘ahu stands fourth as compared with the other islands. There are two mountain ranges on the island of which the eastern (the Ko‘olau Range) is the longest and contains a number of deep valleys, one of which, Nu‘uanu, intersects the range giving access from one side of the island to the other. The fertile lands lie in the valleys and along the lower spurs of the mountains and extend almost to the sea. There is very little woodland except high up in the valleys and on the mountains. Honolulu is on the south side of the island; La‘ie on the northeast or opposite side. The two places are thirty-two miles apart. There are 1,438 Saints on O‘ahu, including children, namely, 677 in the Honolulu Branch, 364 in the La‘ie Branch, and 397 in the O‘ahu Conference, which comprises ten branches, namely, Kahana with 154 Saints, [10] including children; Ka‘alaea, 27; Kailua, 32; Waimanalo, 21; Kalaekao, 23; Halawa, 17; Waikele, 25; Kawaihapai, 20; and Waialua, 43.

Branches on O'ahu described by Andrew Jenson during his tour of 1895.

Branches on O'ahu described by Andrew Jenson during his tour of 1895.

The Kahana Branch embraces the Saints residing in the village of Kahana, which is situated in a beautiful little valley extending inland from the Kahana Bay. The place is eight miles southeast of La‘ie. The branch has a lumber meetinghouse, 38x20 feet, built in 1878; it also has a Sunday School, Relief Society, and Mutual Improvement Association for both sexes. J. Paulo is president of the branch.

The Ka‘alaea Branch comprises the Saints living in a scattered condition along the shores of Ko‘olau Bay, in the district of Ko‘olaupoko, and on the northeast shore of O‘ahu. The branch has a lumber meetinghouse (dedicated by Elder Matthew Noall on September 24, 1893), which has a central location on elevated ground near the seashore and is about sixteen miles southeast on La‘ie or nearly midway between that place and Honolulu. Nakapuahi presides over the branch.

The Kane‘ohe Branch consists of the Saints residing in the settlement of that name, situated in the district of Ko‘olaupoko, on the northeast coast of O‘ahu, almost twenty-two miles southeast of La‘ie and ten miles north of Honolulu.

The Kailua Branch embraces the Saints residing in a native settlement of that name, situated about five miles southeast of Kaneohe, or about eleven miles by road northeast of Honolulu, in the district of Ko‘olaupoko. Holi is president of the branch.

The Waimanalo Branch consists of Saints residing in and near the sugar plantation of that name in the district of Ko‘olaupoko, near the southeastern extremity of the island of O‘ahu, fifteen miles by wagon road northeast of Honolulu and about thirty miles southeast of La‘ie. The Saints own a lumber meeting house which is situated near the foothills several miles inland and in the outskirts of the town. There is also a Sunday School, Relief Society, and Mutual Improvement Association. Wai‘ale‘ale presides over the branch.

The Kalaekao Branch consists of the Saints residing on the dry, sandy, and sultry beach near the Pearl Locks, about eight miles of roundabout road northwest of Honolulu. Maukeale is president.

Halawa Branch embraces the Saints residing in a little village or creek bed near the main road about eight miles northwest of Honolulu, near Pearl Harbor, in the districts of ‘Ewa and Wai‘anae. Some of the members are addicted to the habit of drinking awa and others are affected with leprosy. Kameka, the former president of the branch, was taken to Moloka‘i as a leper in March 1895, since which time the branch has had no presiding officer.

The Waikele Branch consists of the Saints residing in a scattered condition on the south side of O‘ahu in a district of country extending from Halawa westward for a distance of twelve miles. It includes Kualakai and Honouliuli and a number of very small hamlets situated on the numerous small streams which put into Pearl Harbor from the mountains on the north. It is an old branch of the Church dating back to the fifties and has had many presiding officers. Kalanea now presides.

The Kawaihapai Branch comprises the Saints residing in a stock-raising and rice farming district situated near the western extremity of the island of O‘ahu in the district of Waialua. The village of Kawaihapai is situated on the sea coast about four miles east of Ka‘ena Point and about twenty miles from La‘ie. The branch has a small meetinghouse and a Relief Society. Kaiona is president.

Waialua Branch comprises the Saints residing in the town of Waialua, one of the most important seaports of O‘ahu, situated on the northwest coast of the island, about twenty-eight miles northwest of Honolulu, and sixteen miles by roundabout coast road from La‘ie. The branch, which is presided over by Petero Umi, has a meetinghouse and a Relief Society.

From the foregoing it will be seen that there are five meeting houses, two Sunday Schools, four Relief Societies, and two Mutual Improvement Associations in the O‘ahu Conference.

In the afternoon (June 7) I attended the weekly meeting of the La‘ie Primary Association. Sister Noall presides over the association, assisted by all the other missionary sisters. I addressed the children in English for about half an hour. There are only two Primary associations in the mission; the other one is at Honolulu. In the evening four native sisters and two native brethren visited the missionary home to sing for us. A number of beautiful pieces were rendered, the first one being composed especially for the occasion by Sister Miriama Kekuku.

Saturday, June 8. I continued my historical labors and also attended a Relief Society meeting, which I addressed by the assistance of President Noall as interpreter.

Sunday, June 9. I accompanied Elder Noall and wife to Kahana, a village eight miles distant, where we attended meeting and had a good time with the Saints. After returning to La‘ie I delivered a lecture on Church history, according to previous appointment. Brother Noall interpreted in this meeting as well as in Kahana. In the evening I addressed the missionary brethren and sisters at Lanihuli.

The Kahana Branch is perhaps a good sample of a genuine native branch of the Church on the Hawaiian Islands. In dress, manners, conversation and general deportment, they exhibit the characteristics of the race to which they belong. Both men and women came to meeting barefooted; but otherwise their persons were properly protected. The women all wear loose dresses of the Mother Hubbard style; the men’s clothing consists of shirt and trousers.

“Jenson’s Travels,” June 14, 1895 [11]

Wailuku, Maui, Hawaiian Islands

Monday, June 10. At 6:10 a.m. I left La‘ie on a tour to some of the other islands of the Hawaiian group in search of material for Church history, accompanied by President Matthew Noall and wife and their little baby boy George. We started for Honolulu with a horse team, and instead of taking the nearest and more direct road to that city, we concluded to go a more roundabout way, in order to visit a branch of the Church in another locality, and also to see other parts of the island. Hence instead of starting out in a southeasterly direction we took the road leading northwest, and after traveling three miles we reached the famous sugar plantation of Kahuku, which is situated near the northern extremity of the island of O‘ahu. Here an incorporated company has expended about a quarter of a million dollars, in the construction and importation of a sugar mill, steam plows, pumps, windmills, houses, sheds, etc. About one thousand acres are cultivated in cane, and about three hundred men, mostly Japanese, are employed. In passing through we saw about one hundred and fifty of these, clad in their light working attire of blue, engaged in planting cane in true oriental style. These Japanese are paid from $10 to $12 per month for their labors, out of which they board themselves; but wood for cooking purposes is furnished them free. The natives (Hawaiians), of whom a few also are employed on the plantation, receive $18 per month for the same kind of labor. Of course overseers, foremen, etc., get more. A cluster of white-washed lumber shanties built adjacent to the mill constitute the Japanese part of Kahuku, while the officers’ quarters are situated on the opposite side of the road, and consist of a number of fine and comfortable frame cottages. During the last two years the managers of the La‘ie Plantation have had their cane ground and sugar manufactured here, as the old mill at La‘ie, bought by the Church many years ago, is incapable of doing work suitable to the times. It is claimed that it lost about 30 percent of the saccharine matter in the process of extracting and manufacturing, which loss in these days of close sugar competition, destroyed all the profits of the cane industry; and it was found cheaper and better to let the Kahuku company do the work on shares.

A short distance west of the mill, near the old village of Kahuku, the company has built one of the finest and most modern steam pumps operated on the islands. It pumps water from a bottomless spring (which yields forth any quantity of water desired) to the higher ground, from which the water is turned into the cane fields for irrigation purposes.

Continuing our journey from Kahuku we change our course of travel from a northwesterly direction, and followed the coast for several miles until we reach the small village of Waimea, situated on the head of a little bay and at the mouth of a picturesque gulch of very narrow valley with high mountains, almost perpendicular on either side. This place is notable, historically, as the place where two naval officers were killed in 1792. They landed from a ship that was taking provisions to Vancouver’s expedition, and getting into a quarrel with the natives lost their lives. At Waimea the longest bridge on the island was constructed and opened on the occasion of Queen Lili‘uokalani’s visit to La‘ie in August 1891.

Sixteen miles from La‘ie we reach Waialua, the principal town on the northwest coast of O‘ahu. This place, which nestles beautifully in its tropical foliage and extensive orchards, is built along a fine bay affording good anchorage and at the mouth of one of the chief streams of the islands. There is a branch of the Church presided over by Petero Umi, whose large and commodious dwelling built over fifty years ago, has for several years afforded comfortable shelter for scores of Utah elders, who have visited the Hawaiian Islands as messengers of truth and salvation. The Saints at Waialua own a good and substantial meetinghouse in which regular services are held every Sabbath, and the branch, though not so large as it was years ago, is in a fair condition.

At Waialua we leave the coast and take the road leading almost through the center of the island in a southeasterly direction to the celebrated Pearl Harbor, on the water edge of which, about ten miles from Honolulu, American real estate men have located Pearl City, which they are booming for all it is worth, and undoubtedly for as much more as they can get out of it. A suburban railway connecting the place with Honolulu has already been built. Passing on we enter the suburban town of Moanalua, where there are several members of the Church; and at 6:10 p.m., twelve hours to a minute after leaving La‘ie we drove through the gate to the grounds of the branch headquarters at Honolulu to be welcomed by Elders Edwin C. Dibble, George H. Fisher, and George H. Birdno, who are laboring as missionaries on the island of O‘ahu. In our journey of forty-five miles today we saw some beautiful natural scenery, and a few lovely spots here and there between the rugged volcanic mountain systems of the island. Traveling from Waialua to Pearl Harbor, we had the irregular peaks of the Ko‘olau Range on our left and the Wai‘anae Mountains on our right. The clouds rested heavily upon the mountain tops; the winds blew, and the rain descended upon us now and then; and between times the tropical sun, as he peeped through the openings in the clouds, gave us a sample of his heating power. Utah is good enough for me!

Tuesday, June 11. This is a national holiday in the Hawaiian Islands known as Kamehameha Day. It is celebrated as the birthday of the great king Kamehameha I, the first who conquered the smaller chiefs of the different islands and founded the Hawaiian Kingdom with himself as the first king. But it is not certain that he was born on June 11. Horse racing at the Kapiolani Park was the order of the day; but instead of participating in the sports, some of us elders and Sister Noall went to Waikiki and attended the anniversary meeting of the Relief Society held at that place under the direction of Sister Koleka. We had a good meeting; many short speeches were made, aloha given and taken, means donated and disbursed, $2 being voted for me specially to help me on my journey. I spoke through Brother Noall as interpreter for a few minutes. The meeting being over, we all repaired to the adjacent grove in front of Koleka’s house, where a native feast was prepared, the food being spread on the green; eighty-five people sat down to eat, with Brother and Sister Noall and myself at the head of the “table,” or mats which were used instead of tables. The food was exceptionally good, at least at our end of the table. It consisted of poi, fresh meat, pie, bread, cakes, watermelon, etc., and while the natives with great adaptability conveyed the poi from the huge calabashes into their mouths with their fingers, while chatting in their own characteristic style, we alakais were provided with spoons; hence we escaped the rather “unpalatable” ordeal of soiling our fingers in native style. But even provided with a spoon, the poi I eat will cause no one in Hawaii to go hungry. I can eat poi already, but—well, I would just as soon try something else. After the feast, several members of the Honolulu choir who were present entertained us by singing several beautiful songs, closing with the popular piece called “Aloha ‘Oe.” They also sang the national air “Hawai‘i Pono‘i.” Then we all returned to Honolulu.

Wednesday, June 12. After attending to several duties during the day, Elder Matthew Noall, wife and child, and myself boarded the steamer Likelike and sailed from Honolulu at 6:30 p.m., bound for the islands of Maui and Hawai‘i. The evening was windy and the sea rough, and we had no sooner got outside the harbor than the little vessel began to pitch and roll in a most disagreeable manner. Well, the consequence, as one might suppose, was that all hands, except the sailors and cooks, got seasick. And genuine, straightforward seasickness it was, too. My immediate traveling companions—I hate to mention names when I write of unpleasant things—were among the greatest sufferers. And it lasted all night and until long after sunrise the next morning. And the historian was like the rest. His experience on five voyages across the Atlantic, and a 2,500-mile voyage on the Pacific counted for nothing in these Hawaiian waters, or at least not onboard the Likelike. In vain did he endeavor to copy the theory of the Christian Scientists and imagine himself well. He was sick, and it was of no use denying it; and he did not, after two or three attempts; but the next morning he recorded in his private journal that one of the most miserable nights of his life was spent onboard the Likelike en route from O‘ahu to Maui.

Thursday, June 13. Being more under the influence of seasickness than sleep. I found myself on the deck of the Likelike at 2:00 in the morning looking for land. I had observed that the vessel had ceased her pitching and rolling to a certain extent, as if she was on the leeward side of something. And sure enough there it was! In the beautiful tropical moonlight the mountains of Moloka‘i could be seen distinctly on our left, and the noble heights of the island of Lana‘i on our right. I thought of Walter M. Gibson on his rock “Temple” as some termed his “sacred” house on Lana‘i; but being nearsighted I could not see it. And, though so sick, I also looked for the leper settlement on Moloka‘i, but I was informed by a fellow passenger that it was on the other side of the island. Passing on we saw another land ahead of us. This I was told was the island of Maui; but judge of my disappointment when I learned that our place of destination was on the windward side of the island, and that we in passing its most northwestern point would be exposed to the heavy rolling seas worse than ever. But there was no help, for the vessel was bound for Kahului and not for Lahaina.

Well, the daybreak came at the proper hour, but the wind blew and the sea rolled just the same; the sun rose—one of the passengers said in the west—but the wind, sea, and seasickness continued as in the middle of the night. No relief. Breakfast was announced, but though every stomach was empty, the invitation to replenish it was unheeded; the steamship company saved the meal which was due the passengers who had paid cabin fare, and the purser no doubt made a proper entry in the profit and loss column.

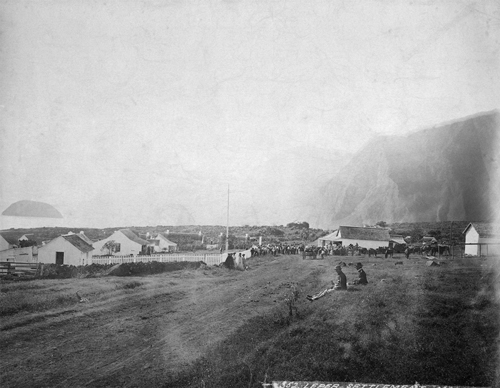

Wailuku from the east looking up 'Iao Valley. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Wailuku from the east looking up 'Iao Valley. Courtesy of Church History Library.

But all trouble had an end. At 8:30 a.m. the rattling of chains announced the fact that the anchor was being cast into the sea, and the passengers were informed that Kahului Bay had been reached at last, and that they were at liberty to land. Well, that was easier said than done. How could the poor suffering specimens of humanity, who had spent such a dreadful night onboard, be lowered into the small boats while the sea yet persisted to rock-a-bye the good Likelike as if she was still in midocean. But the task was accomplished much easier than anticipated. The steps were lowered; the passengers descended one at a time to the lower end, and when a heavy sea would bring the boat up within hailing distance of the steps, he or she would drop into it; and while waiting for another wave, another passenger would prepare to drop. In this manner all the passengers who intended to land at Kahului descended and were finally rowed ashore and landed in safety. Once more on terra firma we looked for our friends who were expected to meet us; but as none were in sight, we hired a carriage, which took us four miles through Wailuku (photo of Wailuku) into the lower end of the historical ‘Iao Valley, to the residence or Kuai ‘Aina, the president of the Wailuku Branch, where we also had the pleasure of meeting three of our brethren from Zion. They were Elders Wm. H. Mendenhall, president of the Maui Conference, Henry Moss, and Lewis R. Jenkins. These brethren had been waiting for us a whole day, the steamer which brought us being one day behind her regular time. After washing in the creek, we ate a little rice, bread, and fruit, but the effects of the seasickness remained with us all day. We now spent most of the day at the house of Kuai ‘Aina, who was kind to us, conversing with our fellow missionaries and some natives who came to see us. We also perused books and wrote historical and descriptive notes. Towards evening Brother Noall and I visited Keau, an old member of the Church, residing in the lower end of the town of Wailuku, and at 6:30 we commenced a two-and-a-half-hour meeting with the Saints of the Wailuku Branch in the lumber meetinghouse, standing on the north side of the creek at the foot of the cactus-covered mountain. (Photo of Wailuku Branch.) Brother and Sister Noall and I were the speakers, Elder Noall interpreting for me. We had a good time, and the natives, of whom about fifty were present, seemed highly pleased and after the meeting shook hands with us very warmly. We returned to the house of Kuai ‘Aina and spent the night—my only night on the island of Maui.

“Jenson’s Travels,” June 14, 1895 [12]

Waikapu, Maui, Hawaiian Islands

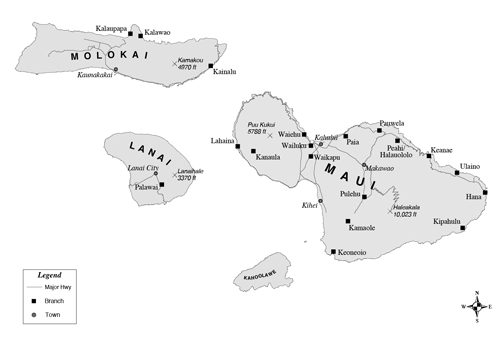

The Maui Conference embraces all the Saints residing on the islands of Maui, Moloka‘i, and Lana‘i, and according to the statistical report December 31, 1894, it consisted of nineteen branches; namely, fifteen on Maui, three on Moloka‘i, and one on Lana‘i. (Map of Maui branches) The names of the branches with the total number of souls in each are as follows: Waiehu, 56; Wailuku, 132; Waikapu, 85; Pulehu, 149; Pa‘ia, 19; Peahi, or Halauololo, 56; Pauwela, 24; Kama‘ole, 58; Ke‘anae, 41; Ula‘ino, 29; Hana, 46; Kipahulu, 22; Keone‘o‘io, 38; Lahaina, 69; Kana‘ula, 54. All those are on the island of Maui. The three branches on Moloka‘i are Kalawao, with 78; Kalaupapa, with 149; and Kainalu, with 54 souls belonging to the Church. The branch on Lana‘i called Palawai has only thirteen members. The totals for the whole conference give 102 elders, 42 priests, 48 teachers, 49 deacons, and 75 lay members: namely, 275 males and 430 females. Adding 218 children under 8 years of age, the total of souls belonging to the Church in the conference is 1,164 divided into 422 families. This makes Maui the largest conference in the Hawaiian Mission. It will be remembered also that Maui is the cradle of Mormonism on the Hawaiian Islands, this being Elder George Q. Cannon’s first successful field of missionary labor.

Branches in Maui, Molokai, and Lanai described by Andrew Jenson during his tour of 1895.

Branches in Maui, Molokai, and Lanai described by Andrew Jenson during his tour of 1895.

Maui ranks as the second island of the Hawaiian group in point of size and agricultural importance. The island is formed of two mountain masses joined together by a low isthmus, the northwestern part being the smaller. The mountains of that part of the island are very rugged, and are pierced by several deep valleys. On the northern side the cliffs form steep precipices, facing the sea. On the west the land is more undulating and spreads out into pasture lands. The southeastern or main part of the island is filled up by the great mountain Haleakala (the house of the sun), whose summit is 10,030 feet above the level of the sea; it is also the largest extinct volcano in the world. The rim of the crater is nearly twenty miles in circumference; its depth is 2,700 feet below the highest point. The view from the brink takes in the whole crater in all its grandness, while the hills on its floor, which are from five to seven hundred feet in height, appear like ant hills. The rim of the crater is broken in two places by gaps, known respectively as the Ko‘olau and Kaupo gaps. Through these, in past times, the lava ran to the sea. The northeastern coast is rugged, forming a succession of palis, or precipices, facing the sea. The southern slope is rocky, and marked here and there by old lava flows. The western slope is gentle and covered with grass, which affords good pasture. The area of the whole island is 760 square miles; its length is 48 miles; average breadth, 30 miles; population in 1890, 17,357. The island is divided into four civil or political districts, named respectively, Lahaina, Wailuku, Makawao, and Hana.

The Maui Conference is presided over during the present term (from April to October, 1895) by Elder William H. Mendenhall, assisted by Elders Henry Moss and Lewis R. Jenkins. Their headquarters are at the town of Wailuku, which is noted as the place where one of the first branches of the Church was organized in the Hawaiian Islands, and is still one of the largest branches of the Church in the mission. It has a meetinghouse, a Sunday School, a Relief Society, and a Mutual Improvement Association. The town of Wailuku is one of the historic places on the islands. It was in the valley of ‘Iao lying immediately back of the town where Kamehameha I, in 1790, defeated the king of Maui. On that occasion the stream is said to have been choked up with dead bodies, and therefore the name Wailuku (the water of slaughter) was given to the creek. It was at Wailuku also that Walter M. Gibson held some of his greatest conferences with the natives and sold his “Priesthood” certificates to them. Wailuku has a present about 2,000 inhabitants. It is situated on rising ground about two miles inland, or three miles from the landing place of Kahului, on the north coast of Maui, with which it is connected by railroad. It is surrounded by the Wailuku Plantation cornfields.

The Waiehu Branch comprises the Saints residing at the plantation and village of Waiehu, which is situated about two miles inland from the northern coast of Maui and about four miles north of Wailuku. The branch has a lumber meetinghouse, a Sunday School, a Relief Society and a Mutual Improvement Association; Kahalokai is president.

Waikapu Branch consist of the Saints residing in the village of that name beautifully situated on the narrow neck of land connecting the two sections of the island of Maui, and commands a beautiful view of Mount Haleakala and the sea both north and south. The branch has a neat little meetinghouse, a Sunday School, Relief Society, and a Mutual Improvement Association.

The Pulehu Branch, the largest in the conference and one of the first branches organized on Maui, comprises the Saints residing in a scattered farming district known also as Kula on the northwestern slope of Mount Haleakala. The meetinghouse belonging to the branch is centrally located near the main road twelve miles southeast of Wailuku and about midway between the southwestern and northeastern coast of the island. There is also a Sunday School, a Relief Society, and a Mutual Improvement Association. Palo has presided over the branch since 1892.

The Pa‘ia Branch comprises the Saints residing at or near the plantation of Pa‘ia, which is situated near the north coast of Maui, about ten miles east of Wailuku, with which town and Kahului it is connected by railway.

The Peahi (or Halauololo) Branch consists of Saints residing in the scattered settlement of that name situated inland about three miles from the north coast of Maui, and about fifteen miles east of Wailuku. There is a lumber meetinghouse somewhat centrally located; also a Sunday School, a Relief Society and a Mutual Improvement Association. Palu Kekauhuna is president of the branch.

The Pa‘uwela Branch consists of the Saints residing in the native village of Pa‘uwela, situated about one and one-half miles inland from the north coast of Maui, and about nineteen miles east of Wailuku. The president’s name is Kalakana.

The Kama‘ole Branch comprises the Saints residing in and about the native village of that name situated in the district of Makawao on the western slope of Mount Haleakala, in the neighborhood previously mentioned known as Kula. The village is about twenty miles southeast of Wailuku, and about eight miles inland from the seaport town of Makena. The branch owns the best Latter-day Saint meetinghouse on the island, and has also a Sunday School and a Relief Society. Uilania Kaluau presides.

The Ke‘anae Branch embraces the Saints residing in the two coast villages of Ke‘anae and Honomanu, mostly in the latter place where the president, Iona, resides. Honomanu is situated in a deep gulch, near the northeast coast of Maui, and about twenty-five miles southeast of Wailuku.

The Ula‘ino Branch consists of Saints residing in a typical native town of that name situated on the northeast coast of Maui, in the Hana District, and about seven miles southeast of the seaport town of Ke‘anae. The branch owns a little meetinghouse of the genuine native order, with thatched roof, rock floor, a door five feet wide, and provided with mats for seats instead of benches. The branch is presided over by David Ho‘opai, and has a Sunday School.

The Hana Branch comprises the Saints residing in the village and plantation of Hana, situated on the coast and near the eastern extremity of the island of Maui, in the district of Hana. The branch owns a lumber meetinghouse centrally located in the native village. There was once a large branch at this place, having all the usual auxiliary organizations; but during the past few years it has retrograded considerably. Wahahu presides over the branch at present.

The Kipahulu Branch consists of the Saints residing in the seaport town and plantation of Kipahulu situated on the southeastern coast of Maui, in the district of Hana, and about ten miles southwest of the town of Hana. The name of the president is Kauhane.

The Keone‘o‘io Branch consists of the Saints residing in a small fishing village situated on the barren lava rocks on the south coast of Maui, in the district of Makawao, and about six miles southeast of the seaport town Makena. S. D. Kapono presides over the branch, which also has a Sunday School organization.

The Lahaina Branch comprises the Saints living in the historic town of Lahaina, situated on the west coast of Maui. It is an old branch and has a long and interesting history, the material for which is partly on hand. The branch, which is presided over by Kapae, has a meetinghouse, a Sunday School, a Relief Society, and a Mutual Improvement Association.

The Kana‘ula Branch consists of Saints residing in a native village of that name situated in a deep gulch about four miles inland or southeasterly from Lahaina, on west Maui. The branch has a lumber meetinghouse, with thatched roof centrally located; also a Sunday School, a Relief Society, and a Mutual Improvement Association. Hika is branch president.

The island of Moloka‘i is forty miles long and seven miles wide; its area is 270 square miles, and the population is 1890 was 2,632. The northern part of this island is very precipitous, the cliffs extending to the extreme east. The southern side of the island has a narrow belt of flat land, which broadens toward the west. Moloka‘i is one of the least visited of all the Hawaiian Islands, and has but a few foreign residents. Kalaupapa is a peninsula on the north side of the island. The cliffs which surround it are over 2,000 feet high. The only access to the peninsula is by sea, or by a narrow path down the face of the cliffs. At this place is the leper settlement, to which all who have this terrible disease are ordered sent. The lepers live in houses which they build for themselves, or which are erected by the Board of Health. Food is sent from Honolulu and from the adjoining valleys, at the expense of the government.

Of the three branches of the Church on Moloka‘i, two are at the leper settlement, namely Kalaupapa and Kalawao. Both of them have meetinghouses, schoolhouses, Relief Societies, and Mutual Improvement Associations. J. B. M. Kapule presides over the Kalawao (Photo of Kalawao) Branch and S. Kekai over the Kalaupapa Branch. The Kainalu Branch consists of Saints residing in a scattered fishermen’s settlement situated on the east end of Moloka‘i, presided over by Kaulili. There is a meetinghouse and Sunday School at this place.

The island of Lana‘i, lying west of Maui and south of Moloka‘i, is one of the least fertile islands of the Hawaiian group; its area consists of 150 square miles; its length is 19 miles, its breadth, 10 miles. The hills are covered with grass and sheep raising is the chief industry. The water supply is obtained chiefly from rain, since there is only one stream on the island, and this does not reach the sea all the year round. Palawai, the highest elevation, is 3,200 feet above the sea level. The readers of the News will remember that Lana‘i was the island designated as a gathering place for the Hawaiian Saints at an early day. The first Saints gathered there in 1855, and when the American elders returned home in 1858, there were several hundred of them gathered to the island. During the Gibson career, from 1861 to 1864, the property known as Palawai was purchased by Saints for money contributed by the natives, but Gibson had the deed to the same made over in his own name; and after he was excommunicated from the Church by the Apostles in 1864, he refused to deed over the property to the Saints who had paid for it, or to the Church. It remained in his possession till his death and is now owned by his heir or son-in-law who resides at Lahaina, on Maui.

Kalawao, ca. 1890. Courtesy of Brigham Young University-Hawaii Library-Archives.

Kalawao, ca. 1890. Courtesy of Brigham Young University-Hawaii Library-Archives.

“Jenson’s Travels,” June 16, 1895 [13]

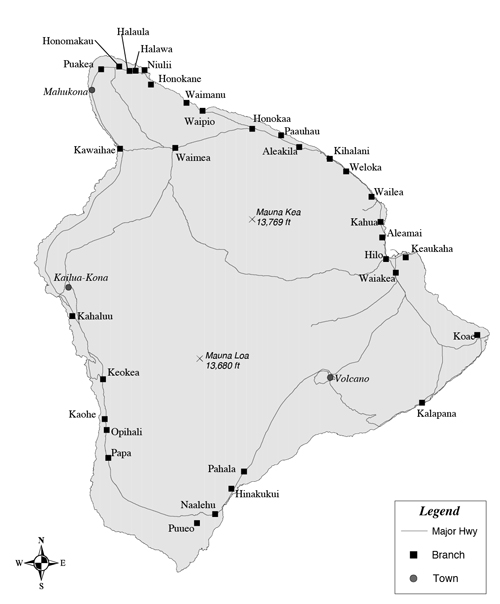

Hilo, Hawai‘i, Hawaiian Islands