Understanding the Physical and Metaphysical Geography of the New Testament

George A. Pierce

George A. Pierce, "Understanding the Physical and Metaphysical Geography of the New Testament," in New Testament History, Culture, and Society: A Background to the Texts of the New Testament, ed. Lincoln H. Blumell (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 485-496.

George A. Pierce is an assistant professor in the Department of Ancient Scripture at Brigham Young University with a joint appointment to the BYU Jerusalem Center for Near Eastern Studies.

The New Testament is replete with geographic place-names, terms, and imagery that provide details for the audiences of the various books. To fully appreciate the efforts of the New Testament authors to include geographic details into their compositions, this chapter will discuss the importance of geography for scripture study, give an overview of the physical regions and sites of the New Testament with case studies that provide an awareness of the life setting of the text, and illustrate the metaphysical, or spiritual, geography of the New Testament. Those who study and teach the New Testament are encouraged to consider how geographic elements influence the interpretation and application of a story.

The question of the relevance of New Testament geographic details often arises for a modern reader given the separation of both time and distance from the original physical settings. In their assessment of the New Testament’s historical geography, Anson Rainey and Steven Notley observe that “the narrative of the New Testament from its beginning to end assumes the reader is familiar with the physical setting that served as a stage for the unfolding drama.”[1] While not intending to write works on geography or the natural world like Strabo (c. 63 BC–AD 24) or Pliny the Elder (AD 23–79), the authors of the New Testament included geographic regional and place-names, topographic indicators, and other elements to help situate their narratives of real people and real events within real locales for their audiences. The inclusion of such details by the New Testament authors presupposes that those places meant something to the original audience either within their sociopolitical context or as cognitive maps of past events associated with various places.

Given the importance of the regions and place-names associated with the Savior’s ministry to the original audiences of the Gospels, an understanding of their geography aids in comprehending the events of the Savior’s life and their significance. Thus, geography, history, and archaeology help establish and illuminate the context of the New Testament, and in turn, context may nuance the understanding and application of a text.[2]

Before examining the physical geography of the New Testament, some aspects involving geographic statements within the text should be noted. First, the authors’ own awareness of geographic reality (first- or secondhand) is apparent; that is, the authors connected events with places and included those places where necessary in their accounts. Throughout the New Testament, the intentional use of region or place-names is a purposeful element in the narrative, not merely filler material. Second, because the authors of the New Testament did not provide maps with their writings, movement had to be conveyed by description; the audiences were either familiar with the territories and places or relied on secondhand knowledge to fill in mental gaps. Certain textual components like those describing the maritime landscape such as the coastal zone (Mark 4:1, 5:21); bodies of water like the Mediterranean and the Sea of Galilee and their waves (Matthew 8:23–27; Mark 6:49; John 6:17–19; Acts 27), and ships (Matthew 8–9, 14:32–33; Mark 4:1, 36; John 21; James 3:4) would be familiar even to those who did not live directly adjacent to the sea.

Third, for the ancient inhabitants of eastern Mediterranean lands, their orientation within the physical world was typically toward the east rather than the north, as privileged on modern maps. Directions within the New Testament are expressed as “up to Jerusalem” (found in the Gospels, Acts, and Galatians) or “down to Capernaum” (Luke 4:31) and refer to topographic situations and changes in elevation rather than any association with cardinal directions (e.g., up=northward and down=southward). Thus, at the end of his second missionary journey, Paul’s travel from Ephesus to Jerusalem and Antioch as recorded in Acts 18:22 relates both of these directions: “And when he had landed at Caesarea, and gone up [in elevation to Jerusalem situated southeast of Caesarea], and saluted the church, he went down [in elevation] to Antioch [about 300 miles north of Jerusalem].” The references of “going up” to Jerusalem or descending from the holy city are more than directional or topographic because the concept of ascending was also ideological as one always “ascended” to the Temple even from higher elevations. This concept is emphasized in Psalm 24:3–6 and the psalms of ascent (Psalms 120–34), which may be connected to pilgrims traveling to the Temple Mount or the Levitical priests ascending the fifteen steps between the Court of the Women and the Court of Israel at the temple.

Finally, the physical geography described serves to illustrate a theological purpose creating a theological geographic aspect to the text.[3] For example, Simon Peter’s confession of Jesus as the Christ (Matthew 16:16) occurred at Caesarea Philippi in the northernmost part of the Holy Land and near the upper limit of Israel’s Old Testament border. Jesus then physically and theologically moved from the periphery of the Holy Land to the religious core of Judaism as he proceeded to Jerusalem to accomplish the Atonement.[4] Further, this theological geography includes place-names or references to Old Testament stories with place-names that illustrate why a place was holy. In this way the story of Jacob’s dream in Genesis 28:10–22 explains the place-name Bethel as “the house of God,” and Jesus makes an allusion to being the physical embodiment of this concept as he described “the angels of God ascending and descending upon the Son of man” (John 1:51). References to Old Testament places and events such as Sodom and Gomorrah (Matthew 11:23–24; Mark 6:11; Luke 10:12; Jude 1:7), the patriarchal narratives (Acts 7), or the Exodus and experience at Sinai (Hebrews 3:16; 11:27; Jude 1:5) in recorded speeches or within the written discourse acknowledged the Church’s heritage and tied the believers in Christ to the theology and salvation history of Israel. Likewise, the inclusion of tribal territories such as Zebulon and Naphtali and subsequent quotation of Isaiah 9:1–2 in reference to the commencement of Jesus’s ministry (Matthew 4:12–16) links the postexilic villages of Nazareth and Capernaum with Old Testament Israel through text and geography, deftly illustrating Jesus as the fulfillment of Isaiah’s prophecy. Such elements of theological geography and references to Israel’s past assume that the original audience had familiarity with the historical and prophetic material of the Hebrew Bible. These issues serve to inform the modern reader of the complex nature of geographic information gleaned from the New Testament.

Physical Geography

With their focus solely on the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, the Gospels are limited in their geographic scope to the area shaped by the kingdom of Herod the Great (ruled 39 BC–4 BC).[5] As a vassal of Rome, Herod controlled territory bordered by the province of Syria to the north, the self-ruling cities of the Decapolis to the east, and the kingdom of the Nabateans to the south. Herod’s reign extended over the regions with familiar names to the New Testament reader such as Galilee, Samaria, Perea (Transjordan; KJV, “beyond the Jordan”), Judea, Idumea, and areas northeast of Galilee.[6] Herod’s prolific construction projects included either renovations or new buildings at Samaria (called Sebaste in the Roman period), the creation of a port and Roman administrative center at Caesarea Maritima, fortresses and palaces at Masada and Herodium, as well as numerous other ventures at various sites. In Jerusalem, Herod oversaw the completion of fortifications, a palace, an aqueduct system, the expansion of the Temple Mount platform and colonnades, the construction of the Antonia Fortress adjacent to the Temple Mount enclosure, and renovations to the temple structure itself.

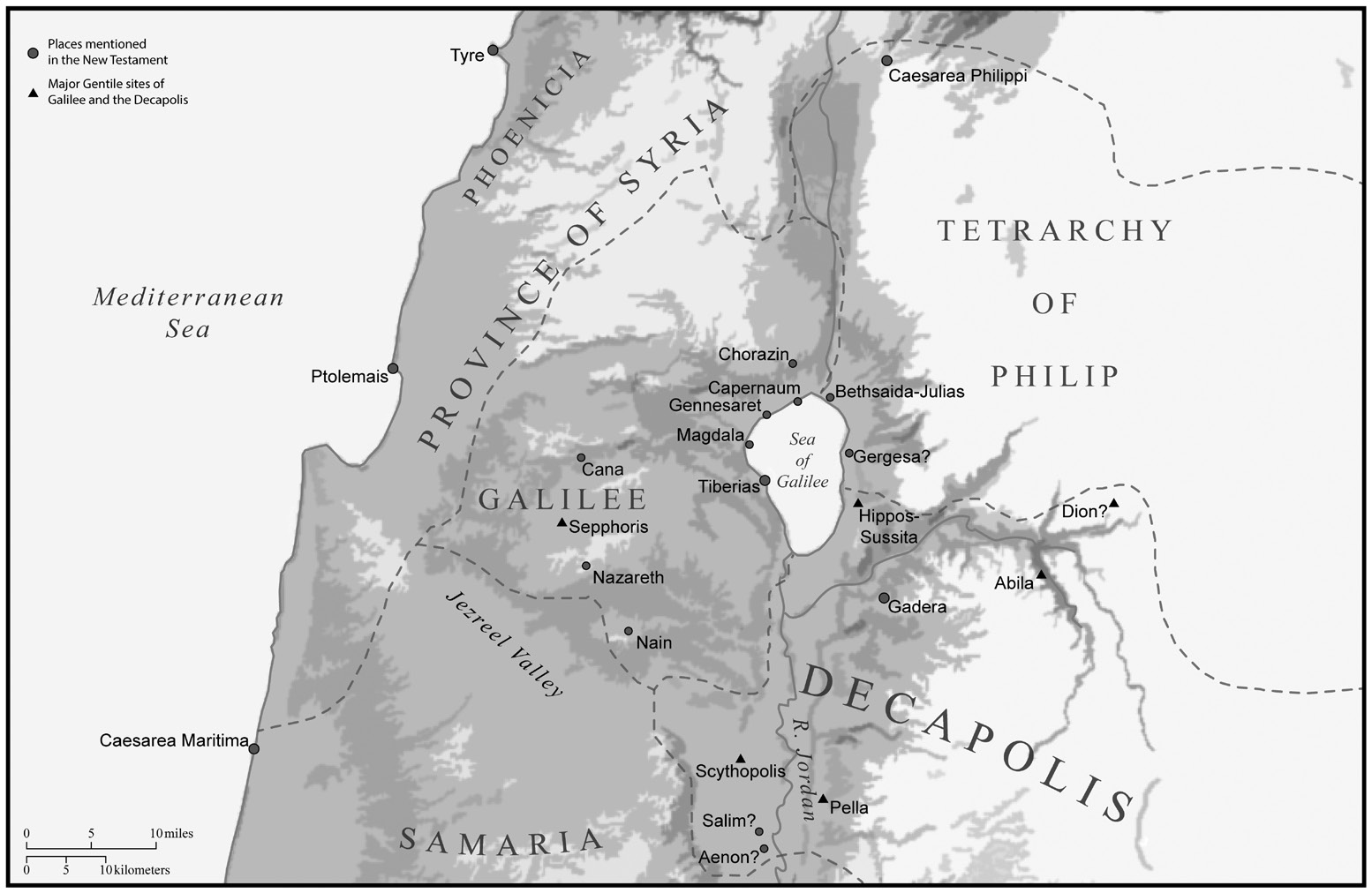

Regions and places in Galilee mentioned in the Gospels. Map by George A. Pierce.

Regions and places in Galilee mentioned in the Gospels. Map by George A. Pierce.

Geography serves as a structure for the sequence of Jesus’s ministry as presented in the Synoptic Gospels. Jesus’s birth in Bethlehem of Judea and childhood in Lower Galilean Nazareth are briefly mentioned in Matthew and Luke with Jesus’s birth there fulfilling Micah’s prophecy: “But thou, Beth-lehem Ephratah, though thou be little among the thousands of Judah, yet out of thee shall he come forth unto me that is to be ruler in Israel; whose goings forth have been from of old, from everlasting” (Micah 5:2). With minimal explanation, the allusion to Jesus’s ancestor David by referring to Bethlehem, David’s birthplace, as “the city of David” (Luke 2:4, 11) invites the audience to interpret the angelic proclamation that “the Lord God shall give unto him [Mary’s son] the throne of his father David: and he shall reign over the house of Jacob for ever; and of his kingdom there shall be no end” (Luke 1:32–33) in light of the promise made to David that “thine house and thy kingdom shall be established for ever before thee: thy throne shall be established for ever” (2 Samuel 7:16).[7] Little is said of Nazareth other than Matthew’s association of the village with either the Hebrew natzor (one who is kept or protected, referring to the divine warnings and protection) or nētzer (branch) found in Isaiah 11:1, Jeremiah 23:5, and Zechariah 3:8.[8] Contempt for Nazareth’s status as an obscure, unimportant locale, evinced by archaeology, is shown in Nathaniel’s statement “Can there any good thing come out of Nazareth?” (John 1:46) and the Pharisees’ opinion “Search, and look: for out of Galilee ariseth no prophet” (John 7:52).[9] However, as George Adam Smith noted, the chief lesson of Nazareth lies in its position near major trade routes close to Sepphoris, a thriving Gentile center, the temptations that the youth of Nazareth faced daily, the proximity of biblical events contrasted with the worldly power and consumption, and the possibility of emerging spotless in the face of such enticements.[10]

Apart from the birth and infancy narratives of Matthew and Luke, the Synoptic Gospels generally focus on his ministry in Galilee, a journey to northern cities such as Sidon and Caesarea Philippi, a later ministry in Judea and Perea, and a final period in Jerusalem prior to his death and resurrection.[11] In contrast, the Gospel of John, while including Galilean episodes, mainly concentrates on Jesus’s ministry in Judea and Samaria.[12] While events at some inland villages such as Nazareth, Cana, and Nain are recounted,[13] all four Gospels associate the Savior’s Galilean ministry with villages and towns surrounding the Sea of Galilee such as Capernaum (Matthew 4:13, 8:5; Mark 9:33; Luke 4:31), Chorazin (Matthew 11:21; Luke 10:13), Bethsaida (Matthew 11:21; Mark 6:45; 8:22; Luke 9:10; 10:13; John 1:44; 12:21), and “the country of the Gergesenes [Gadarenes/

View of Caesarea Philippi.

View of Caesarea Philippi.

The northern sojourn in the Synoptic Gospels marks a turning point in Jesus’s ministry from a concentration on preaching, teaching, and healing in the environs around the Sea of Galilee to a determination to go to Jerusalem to accomplish the Atonement. The highlight of the northern journey of Christ is clearly the confession of Peter at Caesarea Philippi. An understanding of the site and its monumental buildings adds a nuanced layer to the discussion between Jesus and his disciples and Peter’s answer recorded in Matthew 16:13–19. The physical setting is given as “the coasts [i.e., region] of Caesarea Philippi” where Jesus asked the disciples about the prevailing public opinion of his identity with various responses given related to Old Testament prophets such as Elijah, Jeremiah, or even John the Baptist. When the question was posed to the disciples, Peter responded, “Thou art the Christ, the Son of the living God” (Matthew 16:16), and Christ commended Peter for receiving revelation from God, then stated that his Church would be built on the revelation that he is the Christ, promising keys of authority to Peter (Matthew 16:17–19). While the location may be quickly passed over in a reading of the text, the context of the discussion adds weight to the statements made. Caesarea Philippi was built by Herod Philip, the son of Herod the Great, in 2 BC at a sanctuary of the pagan deity Pan called Paneas (modern Banias) dated to the third century BC and situated near one of the headwaters of the Jordan River.[15] (Figure 2: View of Caesarea Philippi) Herod the Great had built a temple to Caesar Augustus known as an Augusteum at the site. The worship of the emperor Augustus is closely tied to his autobiographical work, Res Gestae Divi Augusti (“The Deeds of the Divine Augustus”), a composition that documented the various acts and benefactions that Augustus performed in his lifetime, which would accord him the right of veneration and the status of a divine son of a divine father, Julius Caesar.[16] Thus, the difference between the Roman imperial cult, centered on Augustus and his deeds, and Jesus Christ and his gospel is clearly shown here at Caesarea Philippi. The disciples must make the choice as to what is more important: what their temporal context considers to be the works of a divine son or what spiritual revelation and the ministry of Christ have testified to them. The contrast between the world and Savior echoes into the modern era.

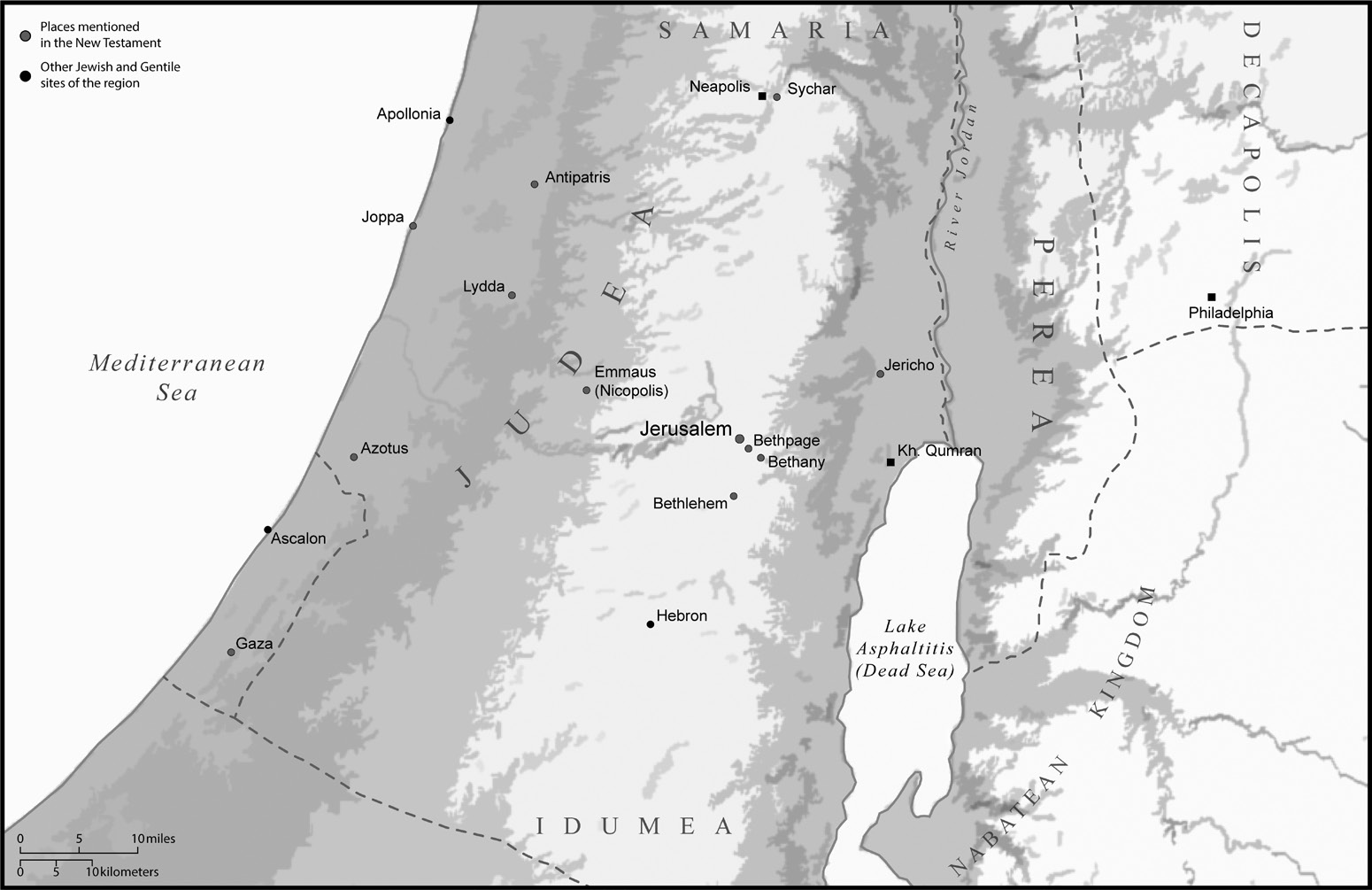

In addition to the confession of Jesus as the Christ in contrast to Augustus and his cult and the location being far removed from the core of Judaism, the location of Caesarea Philippi is also important as there Jesus announced his determination to go to Jerusalem “and suffer many things of the elders and chief priests and scribes, and be killed, and be raised again the third day” (Matthew 16:21). Located near one of the headwaters of the Jordan River, military forces throughout time intent on invading the region, such as the Arameans, Assyrians, Babylonians, and others, would stop to replenish their water stores before campaigning southward through Galilee and into the Old Testament kingdoms of Israel and Judah. From Caesarea Philippi, Christ’s prophecy of his passion and the events in the Synoptic Gospels intimate that Jesus would symbolically conquer the Holy Land as he moved south to Jerusalem. The Jerusalem known by Jesus would have been the epicenter of Jewish religious life with the central focus being the temple. With the conclusion of renovations to the temple in c. AD 26 originally started by Herod the Great, the temple and its associated structures would have inspired the awe of visitors like the Galilean disciples recorded in Matthew 24:1. The sites associated with Christ’s last days and the Atonement in and near Jerusalem such as the upper room, Gethsemane, Pilate’s praetorium, Calvary, or the tomb may not have their exact locations identified and marked for modern visitors, and traditions associated with such sites require careful analysis.[17] Yet the significance of those events add only to the centrality of Jerusalem within the biblical tradition as a place where Jehovah would set his name and establish a place to worship (Deuteronomy 12:11), where Jesus would suffer, die, and rise again (Matthew 16:21), and from which the apostolic Church would grow and spread throughout the Roman Empire.

The expansion of the early Church is predicted by the Savior in Acts 1:8: “Ye shall be witnesses unto me both in Jerusalem, and in all Judæa, and in Samaria, and unto the uttermost part of the earth.” Still steeped in Judaism, the Church in Jerusalem had an affinity with the temple and found its converts in the Jews of the diaspora who returned to Jerusalem to celebrate the pilgrimage feasts such as Passover, the Feast of Weeks (Pentecost), or the Feast of Tabernacles and those from various parts of the Roman empire who chose to stay in Jerusalem (Acts 2–7). Following the martyrdom of Stephen, the Church spread from Jerusalem into parts of Judea and Samaria due to the missions of the Apostles Peter and John and others, including Philip, a deacon, who preached in Samaria and to the Ethiopian eunuch before ministering in coastal sites like Azotus (Old Testament Ashdod) and Caesarea Maritima (Acts 8). Coastal sites such as Jaffa and Caesarea also witnessed events connected to Peter and the spread of the gospel to the Gentiles (Acts 10). The rapid expansion of the Church is documented within Acts as those who believe in Christ moved northward and westward due to persecution in Jerusalem and Judea. Congregations are noted in Damascus (Acts 9:2), Phoenicia (coastal Lebanon), Cyprus, and Syrian Antioch where the followers of Jesus were first called Christians (Acts 11:19, 26).

Regions and places surrounding Judea mentioned in the Gospels and Acts. Map by George A. Pierce.

Regions and places surrounding Judea mentioned in the Gospels and Acts. Map by George A. Pierce.

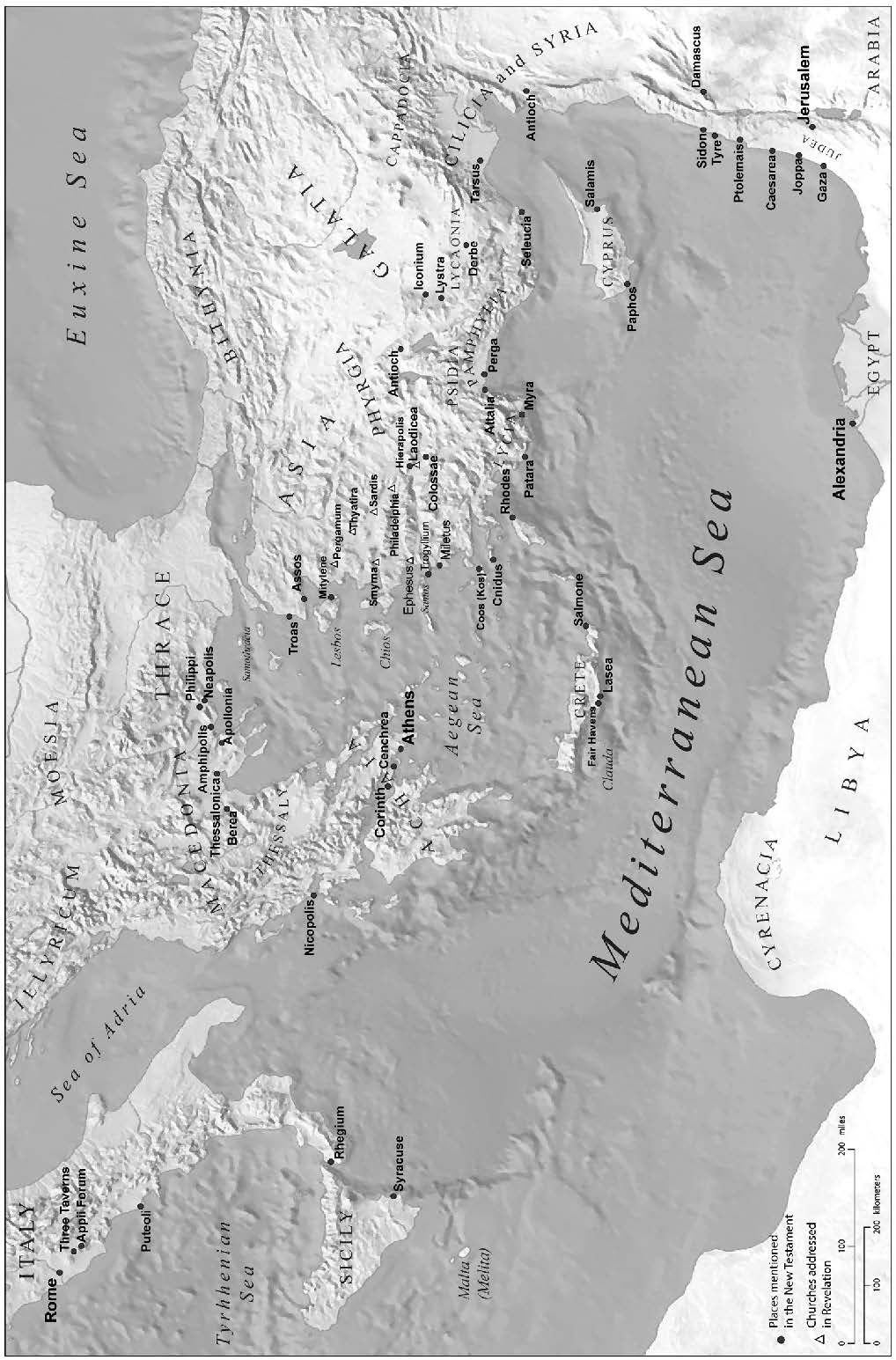

The conversion of Saul, later known as the Apostle Paul, marks the beginning of the next phase of Church growth “unto the uttermost part of the earth.” Following his conversion, baptism, a period of study in Arabia, and time in his hometown of Tarsus in Cilicia, Paul started to travel to preach the gospel in various regions of Cyprus, Asia Minor (modern Turkey), Macedonia, Greece, and eventually Italy. Paul’s companions varied throughout the journeys (e.g., Barnabas, Mark, Timothy, Silas, and Luke), and the locales varied as well as he and his companion(s) visited towns, establishing congregations of believers, and revisited those flocks on subsequent journeys to give further instruction and encouragement. Further enlargement of the Church is reflected in the addressees of other epistles such as “the twelve tribes scattered abroad” (James 1:1), “the strangers scattered throughout Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia, and Bithynia” (1 Peter 1:1), and the seven churches in Asia Minor named in Revelation 1:11.

Certain places that Paul visited are reflected in the titles of epistles found in the New Testament such as Galatia, Colossae, Ephesus, Macedonian Philippi, Thessalonica, and Corinth. Here again, the history and culture of various places such as Thessalonica aids the modern reader in understanding the events that transpired at a certain site and how those events affected the missionary work of Paul and inspired epistles containing doctrinal teachings. In the Roman period, Thessalonica was considered the capital of Macedonia and a commercial hub along the Via Egnatia, an east–west route connecting Byzantium (later Constantinople, modern Istanbul) to Dyrrhachium on the Adriatic Sea (in modern Albania), the closest port to the Italian peninsula.[18] The city was founded in 315 BC and named after Alexander the Great’s half sister. Thessalonica fell under Roman control in 168 BC, and the Romans dismantled the Macedonian aristocracy. Through deft political maneuvering, the city of Thessalonica found itself allied with victorious Roman powers in the turbulent years of the second and first century BC, siding with the Roman general Metellus against a local rebel named Andriscus, supporting Mark Antony and Octavian against Brutus and Cassius following Caesar’s assassination, and backing Octavian in his civil war with Mark Antony. Thessalonica was awarded the status of being a “free city” without a Roman garrison and was able to govern itself according to its own laws and customs.[19] Inscriptions indicate the presence of Jews and Samaritans in Thessalonica and throughout Macedonia, a situation encountered by Paul on his second missionary journey (Acts 16:13; 17:1; 10). According to his custom, Paul preached to the Jews in the synagogue at Thessalonica about Christ’s sufferings and resurrection, and some Jews and Gentiles were converted to the gospel (Acts 17:1–4). The Jewish population that rejected Paul’s message, aided by hired rabble, accused Paul and Silas, saying, “These that have turned the world upside down are come hither also; whom Jason hath received: and these all do contrary to the decrees of Caesar, saying that there is another king, one Jesus” (Acts 17:6–7), after which Paul and Silas were quickly sent to Berea. The accusations by the Jews reflect the culture of the city of Thessalonica in that the news of disturbances in places like Philippi had reached Thessalonica, and the city’s status as a free city would be jeopardized if chaos ensued. The preaching of “another king, one Jesus” may have been interpreted as a prediction of the emperor’s death, which was contrary to imperial decrees enacted by Augustus and Tiberius, and the beginning of a potential revolt against Rome aimed at restoring the Macedonian monarchy. These elements showcase the precarious nature of Paul’s missionary efforts in navigating the history and culture of a place and the reaction of Jews unpersuaded by Paul’s preaching, and how the gospel spread despite opposition and the necessity to move hastily to other towns. Because of his brief time with the Thessalonians, the epistles that he wrote, considered to be some of the earliest written portions of the New Testament, contain foundational teachings for the early Christians about the Second Coming.

Regions and places in the Roman Empire mentioned in Acts–Revelation. Map by George A. Pierce.

Regions and places in the Roman Empire mentioned in Acts–Revelation. Map by George A. Pierce.

Metaphysical Geography

The Bible begins and ends with cosmic geography, namely Eden and the New Jerusalem, and the New Testament contains numerous references to metaphysical geography, considered as real as physical locations within the text.[20] While the scope of this chapter precludes a lengthy discussion, the concepts of darkness and light, heaven and hell as literal places, and the reality of the kingdom of heaven or kingdom of God on earth are evident throughout the New Testament. The central message of Jesus Christ in the Gospels, echoed by the authors of the epistles, is the establishment of the kingdom of heaven, sometimes referred to as the kingdom of God (Matthew 4:17, 23).[21] This kingdom is depicted as a metaphysical reality “promised to them that love him” (James 2:5) and a fulfillment of prophecies concerning the gathering of Israel (Isaiah 52:7–12) and the establishment of an everlasting kingdom (Zechariah 14:9–17). The author of Hebrews described it as “a kingdom which cannot be moved” (Hebrews 12:28), and Peter stated that it would be an “everlasting kingdom of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ” (2 Peter 1:11). While the expectation of the Jewish populace during Jesus’s ministry equated the appearance of the Messiah with the establishment of a physical kingdom of God, the reality presented by Christ was a kingdom that would need incubation and growth and be fully realized at his Second Coming. The coming of the kingdom is a process and not an event.

Salvation is pictured as moving from darkness into light (1 Peter 2:9; 1 John 2:8–11), and perseverance can be seen in the encouragement to dwell in the light (1 Timothy 6:16). The place of rest or reward designated as heaven, found throughout the New Testament, is augmented by titles such as heavenly places (Ephesians 1:3, 20; 2:6), paradise (Luke 23:43), or features like “mansions” (John 14:2). These environs are contrasted with places of imprisonment, punishment, or judgment such as “perdition” (1 Timothy 6:9), “hell” (Matthew 16:18; 23:33; Luke 10:15), “the deep” (Romans 10:7), “mist of darkness” (2 Peter 2:17), “everlasting chains under darkness” (Jude 1:6), “outer darkness” (Matthew 8:12), and “prison” (1 Peter 3:19). While most mentions of hell as a place of punishment use the Greek words gehenna (originally Aramaic) or hades, 2 Peter 2:4 describes the work of Christ in the spirit world and states that Christ visited Tartarus, the Greek name given to the abyss of torment and suffering for the wicked in the underworld, and this is the only place in the New Testament where this specific location in the netherworld is used. The specificity of this statement in 2 Peter augments the description of the gospel being preached “to them that are dead” in 1 Peter 4:6. The use of the place-name Tartarus implies the extent to which the gospel was preached—not merely in the spirit world, the abode of the dead or the grave, but also in the lowest parts of the underworld to spirits being punished or imprisoned in “chains of darkness.”[22]

Conclusion

Geography in the New Testament is more than extraneous detail given by the authors to entertain the audience. Each place-name, physical or metaphysical, was purposefully included to evoke a cultural memory, inform about the sociopolitical or economic condition at the time of the event, or inspire action to achieve or continue in the faith. The Gospels reveal the ministry and atoning sacrifice of Jesus Christ within the regions of Judea, Samaria, and Galilee while also establishing the reality of the theological kingdom of heaven and the expectations of its citizenry. Starting from a kernel in Jerusalem, geographic notations within Acts and the epistles show the rapid growth of the Church through the mid-first century AD as the message of the gospel was accepted by Jews and Gentiles across the eastern Roman Empire. These elements should not be ignored by the modern reader but should serve as an impetus to understand the context of the narrative, which in turn affects the interpretation and application of the narrative. By connecting to the geography of the New Testament, the modern reader should gain further admiration and appreciation for the events and people that have most affected the history of the world and an increased devotion to the Savior and his gospel.

Further Reading

Aharoni, Yohanan. The Land of the Bible, trans. A. Rainey. Philadelphia, PA: Westminster, 1976.

Avi-Yonah, Michael. The Holy Land: A Historical Geography from the Persian to the Arab Conquests 536 B.C. to A.D. 640, trans. A. Rainey. Jerusalem: Carta, 1972.

Notley, R. Steven. In the Master’s Steps: The Gospels in the Land. Jerusalem: Carta, 2015.

Rainey, Anson F., and R. Steven Notley. The Sacred Bridge: Carta’s Atlas of the Biblical World. Jerusalem: Carta, 2006.

Notes

[1] Anson F. Rainey and R. Steven Notley, The Sacred Bridge: Carta’s Atlas of the Biblical World (Jerusalem: Carta, 2006), 349.

[2] Adrian Curtis, Oxford Bible Atlas, 4th ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 4.

[3] Curtis, Oxford Bible Atlas, 7.

[4] Gary M. Burge, Lynn H. Cohick, and Gene L. Green, The New Testament in Antiquity: A Survey of the New Testament within Its Cultural Contexts (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2009), 189.

[5] Several names are typically used to describe the entire region such as Israel, Palestine, Syria-Palestine, or others. Names such as “Israel” or “Palestine” are misleading and historically inaccurate. The Galilee was neither part of the Roman province of Syria nor the province of Judea until the former kingdom of Herod was incorporated into a newly created province of Syria-Palestine by the emperor Hadrian in AD 135 following the Bar Kokhba Revolt, who chose the name “Palestine” based on the association with the Philistines who were forcibly exiled from the territory in the sixth century bc.

[6] The extents of this area are nearly those of the kingdom of Israel during the reigns of David and Solomon as described in the Old Testament. The Hasmonean dynasty gradually incorporated these areas into their Jewish kingdom following the successful revolt against the Seleucids in 164 BC.

[7] Luke’s reference to Bethlehem as the “city of David,” while connecting Jesus to David via Bethlehem, stands in contrast to the Old Testament usage of the phrase translated as “city of David.” That particular epithet refers specifically to the Jebusite stronghold called the “fortress of Zion” conquered by David and made into a royal residence until Solomon built a separate palace (see 2 Samuel 5:7, 9; 1 Kings 3:1).

[8] Rainey and Notley, The Sacred Bridge, 349–50.

[9] For the paucity of first century AD remains at Nazareth, see Vassilios Tzaferis and Bellarmino Bagatti, “Nazareth,” in The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, vol. 3, ed. E. Stern (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1993), 1103–06.

[10] George Adam Smith, The Historical Geography of the Holy Land, 4th ed. (New York: George H. Doran Company, 1896), 432–35.

[11] D. A. Carson and Douglas J. Moo, An Introduction to the New Testament, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2005), 77, 134, 169–72, and 198.

[12] Carson and Moo, An Introduction to the New Testament, 257.

[13] For recent work identifying Cana of Galilee as modern Khirbet Qana, see C. Thomas McCullough, “Searching for Cana: Where Jesus Turned Water into Wine,” Biblical Archaeology Review 41, no. 6 (November/

[14] The site of the miracle of the swine, in which Jesus cast out unclean spirits from one or two persons into a herd of pigs, is located at Gergesa in Matthew 8, Gerasa in Mark 5, and Gadera in Luke 8. The location of Gergesa (modern Kursi) has been more accepted than Gadera or Gerasa based on the topography and proximity to the Sea of Galilee, a position that has been maintained since the third century AD (see “Origen’s Commentary on the Gospel of John” in The Anti-Nicene Fathers: The Writings of the Fathers Down to AD 325, vol. 9, ed. A. Menzies (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1906), 371.

[15] Zvi Ma’oz, “Banias,” in The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, vol. 1, ed. E. Stern (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1993), 136–43, and Vassilios Tzaferis, “Banias,” in The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, vol. 5, ed. E. Stern (Jerusalem: Carta, 2008), 1587–92.

[16] Alison E. Cooley, ed., Res Gestae Divi Augusti (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

[17] For differing viewpoints on the location of the Crucifixion and the tomb of Jesus, see Gabriel Barkay, “The Garden Tomb—Was Jesus Buried Here?,” Biblical Archaeology Review 12, no. 2 (March/

[18] H. L. Hendrix, “Thessalonica,” in The Anchor Bible Dictionary, vol. 6, ed. D. N. Freedman (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 523–27.

[19] Burge, Cohick, and Green, The New Testament in Antiquity, 280–81.

[20] Curtis, Oxford Bible Atlas, 3–4.

[21] The kingdom of heaven is mentioned fifty-five times in Matthew, twenty times in Mark, forty-six times in Luke, and five times in John; Burge, Cohick, and Green, The New Testament in Antiquity, 155.

[22] It should be noted that according to Joseph F. Smith, Christ did not personally visit the “wicked and disobedient who had rejected the truth” but organized messengers from among the righteous dead to share the gospel with those in darkness (Doctrine and Covenants 138:29–30).