The Greek New Testament Text of the King James Version

Lincoln H. Blumell

Lincoln H. Blumell, "The Greek New Testament Text of the King James Version," in New Testament History, Culture, and Society: A Background to the Texts of the New Testament, ed. Lincoln H. Blumell (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 691-706.

Lincoln H. Blumell is an associate professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University.

According to the explicit instructions of King James that the translation of the Bible he patronized be based on manuscripts written in the original languages of the Bible (see chapter 37)––Hebrew for the Old Testament and Greek for the New Testament––the two committees assigned the task of providing a translation for the New Testament employed the Greek texts of the day.[1] The Greek text that was ultimately used as the basis for the KJV New Testament was one produced by the French Calvinist Theodore de Beza (1519–1605).

From Beza Back to Erasmus

Beza came from a prominent Catholic family at Vézelay in Burgundy and had studied law at Orleans before settling in Paris, where he began a career as a lawyer in 1539. Though he would earn a reputation as a capable litigator, his real passion was for classical literature, and he would eventually earn some notoriety for publishing a collection of Latin poetry in 1548. Shortly after the publication of this work, he fell seriously ill. When he recovered, he took it as a sign of divine providence and abandoned his legal career in favor of ecclesiastical pursuits. Later that same year, he went to Geneva and joined the Calvinist movement and formally renounced the Catholic faith. In 1549 he became a professor of Greek at the academy in Lausanne, and in 1558 Calvin invited him to return to Geneva so he could hold a professorship at the newly founded academy.

During Beza’s time as a professor of Greek at Lausanne, he became interested in the New Testament—so interested, in fact, that he determined to publish his very own edition. First, in 1556 he published an annotated Latin edition of the New Testament, and then in 1565 he added a Greek text. Over the course of the next forty years, Beza would go on to publish nine different editions of the Greek New Testament.[2]

The translators of the King James Bible made extensive use of Beza’s 1588–89 and 1598 editions.[3] In these editions, Beza provided the text of the New Testament in three columns: in the left the Greek, in the middle a Latin translation of the Greek, and in the right the Latin Vulgate. For his Greek text, Beza was principally indebted to an earlier Greek text produced by Stephanus, who was in turn dependent on Erasmus; consequently, Beza’s text was virtually the same as these earlier editions. However, it should be noted that Beza did attempt with his editions to find older Greek manuscripts upon which to base his Greek text. At times Beza did consult the Peshita, a Syriac translation of the Bible,[4] for various readings, and he also would consult what has since come to be known as the Codex Bezae.[5] This ancient codex, which came into Beza’s possession sometime after 1562, dated to the fifth or sixth century and contained on the left-hand page the Greek text in a single column and on the right-hand page the Latin text in a single column.[6] Additionally, it also appears that Beza consulted a second ancient manuscript, Codex Claromontanus, which he had found in Clermont, France. This codex, like Codex Bezae, dated to the fifth or sixth century and contained the Pauline epistles written in parallel columns of Greek and Latin. [7] Unfortunately, however, because these two manuscripts differed in many respects from the generally received Greek text of the time, Beza tended not to include the variant Greek readings in his actual text but merely mentioned the variants in his annotations.[8] Consequently, some of these variants, which clearly had an ancient pedigree, never made their way into the KJV translation since they were not in Beza’s Greek text but were confined to the notes. Therefore, even though Beza would consult the Syriac Peshita, Codex Bezae, and Codex Claromontanus, his editions of the Greek New Testament were virtually identical to an earlier Greek New Testament published by Stephanus that was based on much later manuscript evidence (i.e., the Greek NT text of Erasmus [see below]).

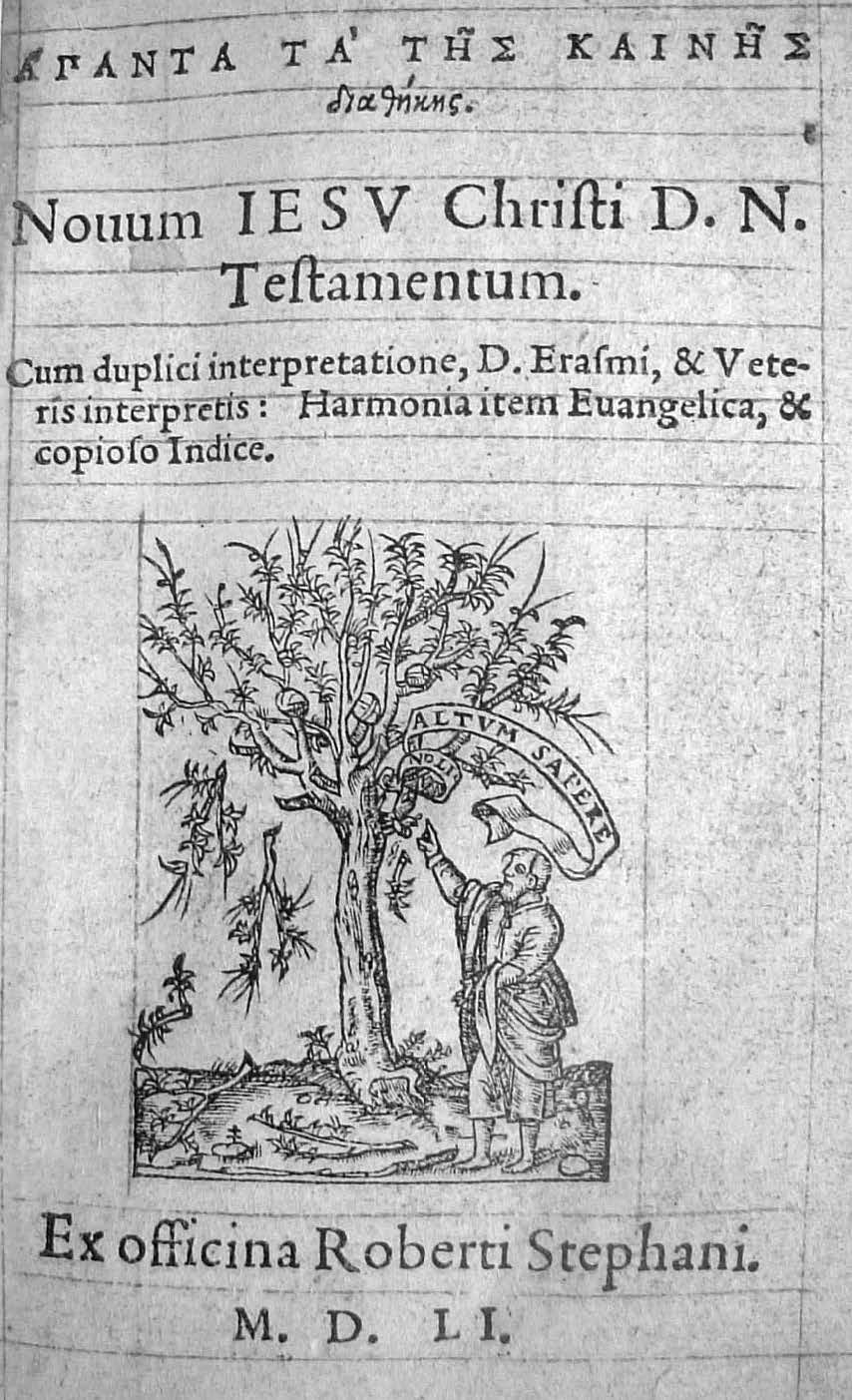

Robert Estienne (1503–59), more commonly known by the Latin form of his name, Stephanus, was a famous Parisian printer and publisher who had a penchant for printing classical and ecclesiastical literature. Besides producing his famous Thesaurus Linguae Latinae in 1532, which was used for many subsequent centuries, he also published a number of Bibles.[9] He published three editions of the Latin Vulgate (1528, 1532, and 1540) and two editions of the Hebrew text of the Old Testament (1539 and 1544–46). After 1544 he turned his attention primarily to publishing Greek texts and during his lifetime published four different editions of the Greek New Testament (1546, 1549, 1550, and 1551). INSERT IMAGE 1 In his first two editions, he relied principally on the earlier Greek New Testament text published by Erasmus but also, to a lesser extent, upon the text published under the direction of Francisco Ximenes de Cisneros, which is known as the Complutensian Polyglot. His third edition (1550) was noteworthy because it was the first Greek edition of the New Testament to include a critical apparatus where textual variants and alternative readings for select passages were noted.[10] His fourth and final version (1551), the one which Beza principally relied on for his editions of the Greek New Testament, was also very noteworthy because, for the first time, Stephanus introduced versification into the New Testament. The versification introduced by Stephanus was subsequently followed and applied in the KJV New Testament, and it is used in virtually all Bibles today.[11]

Title page, 4th edition of New Testament (1551). Robert Estienne. Public domain.

Title page, 4th edition of New Testament (1551). Robert Estienne. Public domain.

As Stephanus’s New Testament editions relied heavily on the Greek New Testament produced by Erasmus, and, to a lesser extent, on an edition produced under Francisco Ximenes de Cisneros, it is worthwhile to discuss these two editions. However, of these two earlier editions, Erasmus’s is by far the most important, at least for the purposes of the present study. It essentially formed the basis of almost all subsequent Greek New Testaments published in the sixteenth century because it was the first widely used Greek New Testament text to appear after the invention of the printing press.[12] Consequently, the Greek text underlying the King James Bible is essentially the text produced by Erasmus, even though it came to the KJV translators via Stephanus and Beza.

Desiderius Erasmus (1466–1536), the famous Dutch humanist from Rotterdam, was ordained a Catholic priest in 1492. Shortly thereafter, he decided to pursue a doctorate in theology and in 1495 went to the University of Paris. During the course of his studies in Paris, he determined to seriously take up the study of ancient Greek, since the majority of early Christian literature was written in Greek. As he became more immersed in the study of ancient Greek, he felt he could best pursue his interests elsewhere. So he left Paris in 1499 without finishing his doctorate and eventually enrolled at Cambridge. After only one year, he left, again without obtaining his doctorate, and moved to Italy to pursue his study of ancient Greek. At the time, Italy was the real center of Greek learning because a number of scholars had left Constantinople and relocated to Italy when Constantinople fell into Muslim hands in 1453. Erasmus would receive his doctorate at the University of Turin in 1506.

In 1511 Erasmus returned to Cambridge, where he would hold a professorship in Greek. This lasted only about three years, however, because the promised financial support for this position never fully materialized. In the summer of 1514, Erasmus left for Basel, Switzerland, where he was approached by a well-known printer named Johannes Froben about the possibility of producing a Greek New Testament.[13] Erasmus did not immediately agree to the project and returned to Cambridge in the spring of 1515. However, when a mutual friend, Beatus Rhenanus, approached Erasmus on behalf of Froben with a promise that if he should produce a text Froben would pay him handsomely, Erasmus readily agreed.[14] By the summer, Erasmus was back in Basel, and work was promptly undertaken on the project.

Erasmus hoped that there might be some readily available manuscripts of the Greek New Testament in Basel that he could use. However, the only manuscripts he could find required some degree of correcting, and there was no one manuscript that contained the entire New Testament. In total, Erasmus used seven different manuscripts to create his edition of the New Testament, and all but one of them were owned by the Dominican Library in Basel.[15] The manuscripts were all minuscules, meaning that they were written in the cursive, lowercase Greek script common in medieval manuscripts.

The manuscripts relied on by Erasmus may be outlined as follows:[16]

1. Codex 1eap, a minuscule containing the entire New Testament except for Revelation, dated to about the twelfth century.

2. Codex 1r, a minuscule containing the book of Revelation except for the last six verses (Revelation 22:16–21), dated to the twelfth century.

3. Codex 2e, a minuscule containing the Gospels, dated to the twelfth century.

4. Codex 2ap, a minuscule containing Acts and the Epistles, dated to the twelfth century or later.

5. Codex 4ap, a minuscule containing Acts and the Epistles, dated to the fifteenth century.

6. Codex 7p, a minuscule containing the Pauline Epistles, dated to the eleventh century.

7. Codex 817e, a minuscule containing the Gospels, dated to the fifteenth century.

e = Gospels (Evangelists), a = Acts, p = Pauline Epistles, r = Revelation

In total, then, Erasmus had three manuscripts of the Gospels and Acts, four manuscripts of the Pauline epistles, and one manuscript of Revelation. Since Erasmus was in such a hurry, he simply submitted Codex 2e and 2ap to the printer, compared these two manuscripts with the others, and wrote in any corrections or emendations for the printer in the margins or between the lines of the two manuscripts.

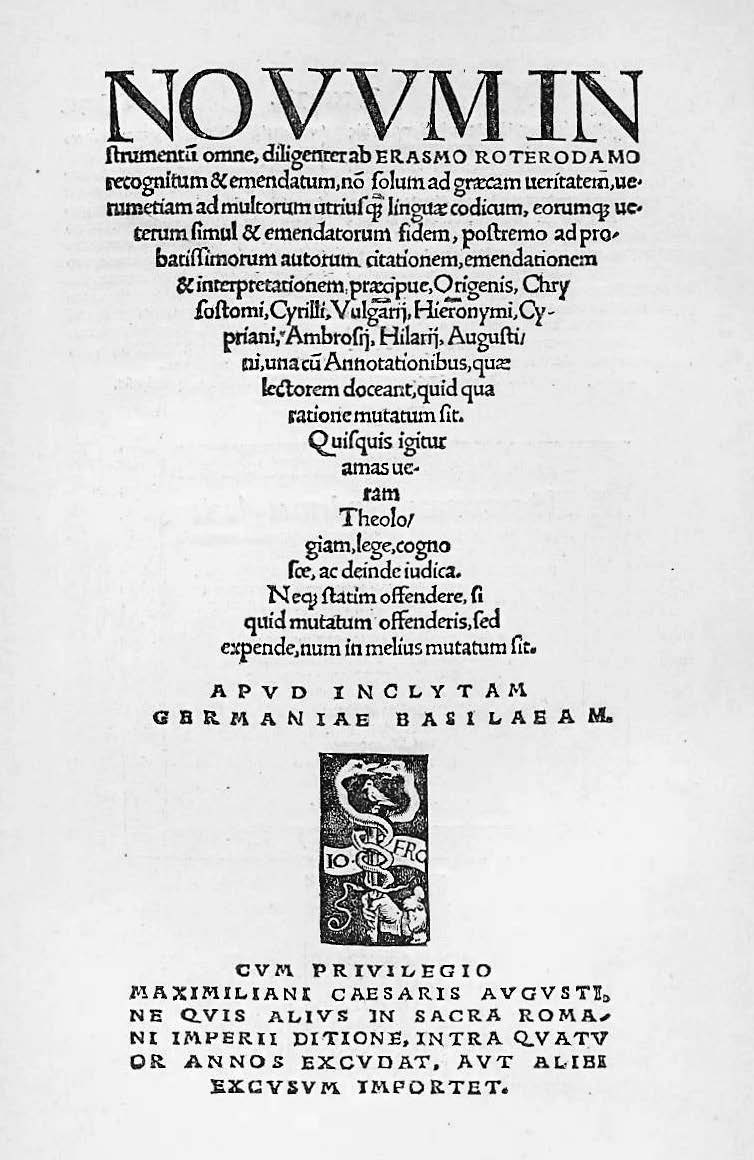

Remarkably, it took Erasmus only a couple of months to finish his edition, and by October 1515 the manuscript was headed to the press. INSERT IMAGE 2 Part of the reason for the extreme haste with which the project was undertaken was that the printer, Johannes Froben, was aware that another version of the Greek New Testament, the Complutensian Polyglot, was also going to be published, and he wanted to ensure that his version came out first. The production of the Complutensian Polyglot was overseen by cardinal primate of Spain Francisco Ximenes de Cisneros (1436–1517).[17] It was printed in 1514, but it was not sanctioned by the pope until 1520 and consequently was not published and widely circulated until 1522. Since Erasmus’s copy was the first printed Greek New Testament on the market, it became the standard text.

Title page, 1516 edition of Erasmus’s Novum Instrumentum omne. Public domain.

Title page, 1516 edition of Erasmus’s Novum Instrumentum omne. Public domain.

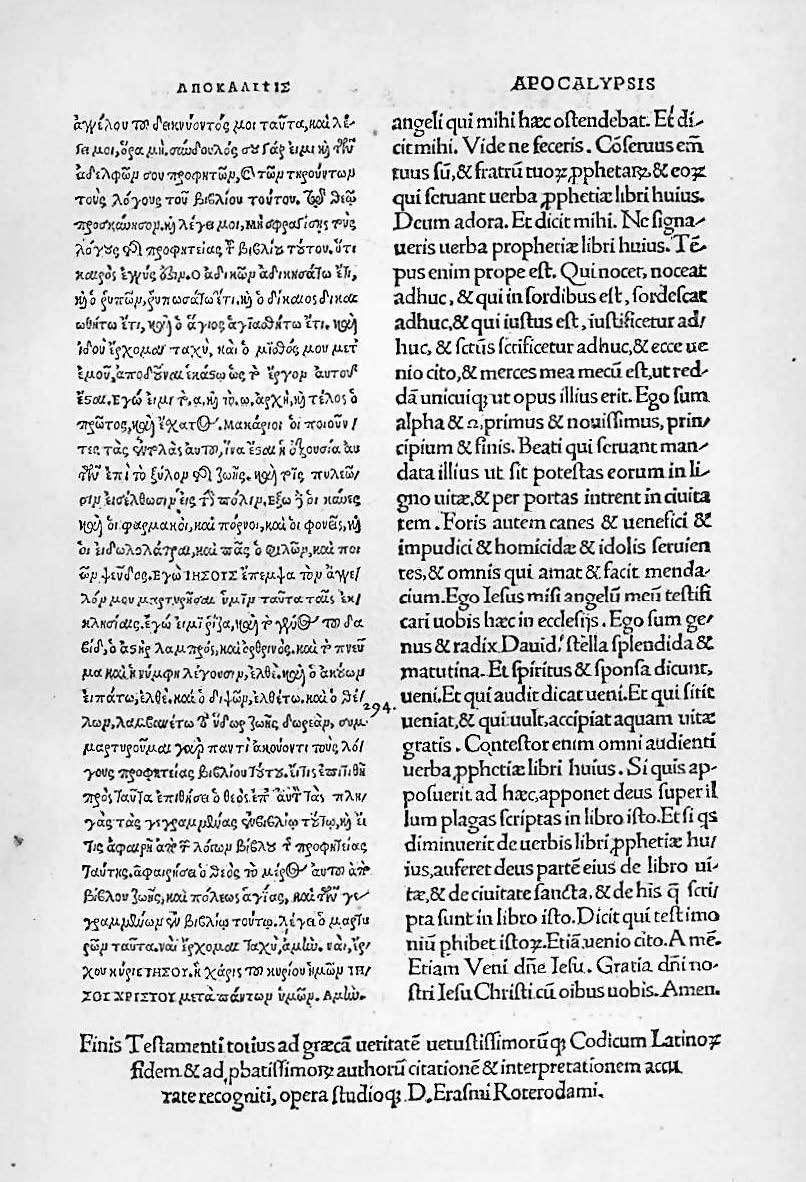

By March 1516 the first edition of Erasmus’s Greek New Testament was printed; it was entitled Novum Instrumentum Omne.[18] INSERT IMAGE 3 The book was a Greek-Latin diglot printed with two columns per page: the Greek text always in the left-hand column and the Latin text always in the right-hand column. The annotations were printed following the text.[19] Owing to the extreme haste with which the first edition of Erasmus’s Greek New Testament was produced and printed, it was loaded with various typographical errors, literally numbering in the hundreds. Besides the typographical errors, however, there were other serious problems with the first edition. These errors arose directly from Erasmus’s haste and use of inferior (late) biblical manuscripts. For example, the manuscript that he relied on for the book of Revelation lacked the final page upon which was written the last six verses (Revelation 22:16–21). To remedy this problem, Erasmus simply used the Latin Vulgate and translated these verses back into Greek. However, the translation supplied by Erasmus was different in many respects from earlier Greek texts and subsequently had the effect of altering and changing certain Greek readings. Elsewhere, when Erasmus ran into difficulties with these Greek manuscripts, he simply provided his own Greek translation based on the Latin text and subsequently introduced a number of Greek variants into the New Testament that were previously unattested in the Greek.[20]

The last page of Erasmus’s Greek New Testament

The last page of Erasmus’s Greek New Testament

(Revelation 22:8–21). Public domain.

In 1519 a second edition was produced[21] in which a number of typographical emendations were made, and again in 1522 a third edition was published in which a few substantive changes were made. Perhaps the most significant change between the second and third editions was the insertion of what has come to be known as the “Johannine Comma,” comprising 1 John 5:7b–8a: “7aFor there are three that bear record bin heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost: and these three are one. 8aAnd there are three that bear witness in earth, bthe Spirit, and the water, and the blood: and these three agree in one” (KJV, emphasis added). In the first and second editions of Erasmus’s Greek New Testament, he did not include either verse 7b or 8a because they were not found in any Greek manuscript of the New Testament he had consulted. Thus, 1 John 5:7–8 read: “7For there are three that bear record: 8the Spirit, and the water, and the blood: and these three agree in one.” However, he came under increasing fire from a number of ecclesiastical quarters because these verses were long thought to be important Trinitarian proof texts. Erasmus therefore remarked that if he could find them in a single Greek manuscript, he would include them in a subsequent edition. A Greek manuscript suddenly appeared with these verses, so he included them in his third edition. Scholars have long recognized that this particular manuscript, which dates to the sixteenth century, was produced for the very purpose of including these verses![22] It is evident that verses 7b and 8a were not original but were later added to 1 John to promote Trinitarian theology.[23]

By the time of Erasmus’s fourth edition in 1527, which proved to be the definitive edition (although a fifth and final edition came out in 1535), some of the more serious text-critical problems with his manuscript were finally addressed. By this time the Complutensian Polyglot was available, so Erasmus judiciously made use of it and corrected certain readings that he had either created via his Latin-to-Greek translations or were the result of the generally inferior nature of the manuscripts he had consulted in Basel to create his Greek text. Notwithstanding the many improvements that were made in the fourth edition, a number of problems still persisted, but because Erasmus’s Greek New Testament was the first widely accessible copy of the New Testament, it gained natural popularity that gave it a status of prominence. In fact, the Greek text of Erasmus would eventually become the standard Greek text of the New Testament for the next two hundred years because it was largely transmitted by Stephanus and Beza. In a 1633 edition of the Greek New Testament produced by two Dutch printers, Bonaventure and Abraham Elzivir, which was basically a reprint of Beza’s 1565 edition, they made the following remark in the preface: Textum ergo habes, nunc ab omnibus receptum, in quo nihil immutatum aut corruptum damus (“Therefore you have [dear reader] the text, now received by all, in which we give nothing changed or corrupted”).[24] From this remark, the Greek text produced by the Elzevirs, which came via Erasmus to Stephanus and then to Beza, came to be regarded for many centuries as the Textus Receptus, the received or standard text of the New Testament.

Conclusion

While the King James Bible effectively set the standard for all subsequent English translations of the Bible and its New Testament translation was regarded with special reverence for many years, it has come under increasing criticism in the past century. The central criticism leveled at the King James New Testament has not so much to do with the actual English translation, though it is not without some problems, but rather with the textual basis of the Greek subtext. The textual basis for the King James New Testament is essentially a handful of late Greek manuscripts that range in date from the twelfth to the fifteenth century and that were known to Erasmus during the time he put together his Greek New Testament. Over the course of the last four hundred years, a number of Greek manuscripts, as well as fragments of other manuscripts, have been discovered that predate by over one thousand years the “Erasmian” text used by the translators of the King James New Testament. In fact, complete copies of the Greek New Testament have been discovered that date to the fourth century (i.e., Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus).[25] One of the most significant contributions of these “newly” discovered texts is that they sometimes contain readings for various verses that differ markedly from those found in the King James Version. These textual variants, as they are called, are significant because in many cases it is near certain they more accurately represent the original text of the New Testament.

Consequently, the King James New Testament, which was produced long before many of these manuscripts came to light, contains some readings that are clearly secondary interpolations not attested in the oldest and most reliable New Testament manuscripts. While this is clearly a shortcoming of the King James New Testament, these textual discrepancies do not substantially affect more than twenty to thirty verses in the entire New Testament, and in only about five or six of them do these variants significantly alter the meaning of a verse or passage. Therefore, the shortcomings of the King James New Testament should not be exaggerated, all the same, neither should they be disregarded and ignored.

In the table that follows, I provide twelve passages that serve to highlight some of the most significant textual variants that either affect the KJV text of the New Testament or for which there is some scholarly discussion regarding New Testament variants.

Passage | KJV Translation | Text-Critical Issue | |

| 1. | Matthew 24:36 | “But of that day and hour knoweth no man, no, not the angels of heaven, but my Father only.” | Based on ancient manuscript evidence, it strongly appears that a phrase was later dropped out of this verse so that the second half should read: “… not the angels of heaven, nor the Son, but only the Father.” Thus, originally, it was more empathic that in mortality Jesus did not yet know the exact timing of the Second Coming. As the verse presently reads in the KJV this is already evident based on a close reading. |

| 2. | Matthew 26:28 | “For this is my blood of the new testament, which is shed for many for the remission of sins.” | There is relatively strong support from ancient witnesses that the adjective “new” (καινή, kainē) was added to Matthew 26:28. While Luke 22:20 does employ the adjective, thus “new Testament” (better rendered “new covenant”), as does 1 Corinthians 11:25 (compare Jeremiah 31:31–34), it was not what Matthew wrote. However, in light of the references in Luke and Paul it is certainly not wrong to call it a “new covenant.” |

| 3. | Mark 9:29; compare Matthew 17:21 | “And he said unto them, This kind can come forth by nothing, but by prayer and fasting.” | Based on ancient textual witnesses, it seems quite likely that the phrase “and fasting” (Greek. καὶ νηστείᾳ, kai nēsteia) was later added to the verse. Thus, it is probably best to omit this phrase. Compare New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) Mark 9:29: “He said to them, ‘This kind can come out only through prayer.’” |

| 4. | Mark 16:9–20 | “9 Now when Jesus was risen early the first day of the week, he appeared first to Mary Magdalene, out of whom he had cast seven devils. 10 And she went and told them that had been with him, as they mourned and wept. 11 And they, when they had heard that he was alive, and had been seen of her, believed not. 12 After that he appeared in another form unto two of them, as they walked, and went into the country. 13 And they went and told it unto the residue: neither believed they them. 14 Afterward he appeared unto the eleven as they sat at meat, and upbraided them with their unbelief and hardness of heart, because they believed not them which had seen him after he was risen. 15 And he said unto them, Go ye into all the world, and preach the gospel to every creature. 16 He that believeth and is baptized shall be saved; but he that believeth not shall be damned. 17 And these signs shall follow them that believe; In my name shall they cast out devils; they shall speak with new tongues; 18 They shall take up serpents; and if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them; they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover. 19 So then after the Lord had spoken unto them, he was received up into heaven, and sat on the right hand of God. 20 And they went forth, and preached every where, the Lord working with them, and confirming the word with signs following. Amen.” | Mark 16:9–20, known as the “Longer Ending of Mark,” is absent from a number of early and important ancient manuscripts. Thus, it is commonly thought that Mark ended at 16:8. However, the “Longer Ending” is nonetheless attested in some important ancient witnesses. Additionally, there are two other endings of Mark, little known outside of scholarship, that are also attested. The “Shorter” or “Intermediate Ending” adds material equivalent to about 1–2 verses after 16:8 and is attested in a few eighth-century manuscripts: “But they reported briefly to Peter and those with him all that they had been told. And after this Jesus himself sent out by means of them, from east to west, the sacred and imperishable proclamation of eternal salvation.” There is likewise another “Longer Ending” attested in a fifth-century manuscript: “And they excused themselves, saying, ‘This age of lawlessness and unbelief is under Satan, who does not allow the truth and power of God to prevail over the unclean things of the spirits. Therefore reveal your righteousness now’—thus they spoke to Christ. And Christ replied to them, ‘The term of years of Satan’s power has been fulfilled, but other terrible things draw near. And for those who have sinned I was delivered over to death, that they may return to the truth and sin no more, that they may inherit the spiritual and imperishable glory of righteousness that is in heaven.’” While there are four different endings of Mark attested, the two best-attested endings are those ending at Mark 16:8 or 16:20 (the one presently in the KJV).[26] |

| 5. | Luke 22:43–44 | “43 And there appeared an angel unto him from heaven, strengthening him. 44 And being in an agony he prayed more earnestly: and his sweat was as it were great drops of blood falling down to the ground.” | These verses are absent in some important ancient manuscripts while they are present in others. Thus, some modern Bibles either omit these verses altogether or place them in brackets to highlight their questionable character. However, the ancient manuscript evidence is such that the verses are attested in the earliest manuscript evidence before they are then omitted by later manuscripts. Likewise, we know from ancient Christian writings that in the middle of the fourth century AD, in the wake of the Council of Nicea, some Christians adhering to the Nicene Creed began to purposely omit these verses from their copies of the scriptures (see Epiphanius, Ancor. 31.3–5). Thus, these verses should be regarded as authentic but suppressed and deleted by some future Christians.[27] |

| 6. | John 5:3–5 | “3 In these lay a great multitude of impotent folk, of blind, halt, withered, waiting for the moving of the water. 4 For an angel went down at a certain season into the pool, and troubled the water: whosoever then first after the troubling of the water stepped in was made whole of whatsoever disease he had. 5 And a certain man was there, which had an infirmity thirty and eight years.” | John 5:3b–4 is missing from most modern translations because there is almost no textual support from any ancient manuscripts. At some point verses 3b–4 were added to explain why the water was “troubled” (or “stirred up”) in verse 7. Since the pool of Bethesda was a mineral spring, the stirring of the water was caused by air being released up through the water. It is clear therefore that someone added the story about the angel long after the Gospel of John was written, and it is best to read the story without this angelic explanation. |

| 7. | John 7:53–8:11 | 53 And every man went unto his own house. 1 Jesus went unto the mount of Olives. 2 And early in the morning he came again into the temple, and all the people came unto him; and he sat down, and taught them. 3 And the scribes and Pharisees brought unto him a woman taken in adultery; and when they had set her in the midst, 4 They say unto him, Master, this woman was taken in adultery, in the very act. 5 Now Moses in the law commanded us, that such should be stoned: but what sayest thou? 6 This they said, tempting him, that they might have to accuse him. But Jesus stooped down, and with his finger wrote on the ground, as though he heard them not. 7 So when they continued asking him, he lifted up himself, and said unto them, He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her. 8 And again he stooped down, and wrote on the ground. 9 And they which heard it, being convicted by their own conscience, went out one by one, beginning at the eldest, even unto the last: and Jesus was left alone, and the woman standing in the midst. 10 When Jesus had lifted up himself, and saw none but the woman, he said unto her, Woman, where are those thine accusers? hath no man condemned thee? 11 She said, No man, Lord. And Jesus said unto her, Neither do I condemn thee: go, and sin no more. | The entire story of the woman taken in adultery in John 7:53–8:11 is almost certainly an interpolation as it only appears in one known manuscript before the eighth century: Codex Bezae of the fifth or sixth century. Likewise, in later manuscripts it is sometimes placed after John 7:36 or 7:44, at the end of the Gospel (i.e., after John 21:25), or after Luke 21:38, which suggests it was not original to this section of John. Because a story about Jesus forgiving a woman of sins was known by Christians already in the second century (Papias in Eusebius, Hist. eccl. 3.39.17), and this is the only time in the Gospels such a story is told, there is perhaps some ancient basis for it. Nevertheless, its placement here in John is clearly an interpolation, and it is likely that there are elements of the story that are clearly secondary.[28] |

| 8. | 1 John 5: 7–8 | “7 For there are three that bear record in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost: and these three are one.8 And there are three that bear witness in earth, the Spirit, and the water, and the blood: and these three agree in one.” | The entire underlined section comprising 1 John 5:7b–8a is an interpolation and not part of the original text. This famous interpolation, often referred to as the “Johannine Comma,” was added to Greek manuscripts in the sixteenth century and first appears in a Latin manuscript in the eighth century. Someone inserted the phrase to serve as a Trinitarian proof text. In this section of 1 John, the point is being made that Jesus had a corporal body, and it has nothing to do with the Godhead (Father, Word, and Holy Ghost). Modern bibles have universally omitted this passage so that it reads: “7 There are three that testify:8 the Spirit and the water and the blood, and these three agree” (NRSV, 1 John 5:7–8). |

| 9. | Acts 23:9 | “And there arose a great cry: and the scribes that were of the Pharisees’ part arose, and strove, saying, We find no evil in this man: but if a spirit or an angel hath spoken to him, let us not fight against God.” | The last phrase of this verse appears to have been added based on the ancient manuscript evidence. Thus, the second half of this verse is better rendered as follows: “We find no evil in this man: what if a spirit or an angel spoke to him?” |

| 10. | 1 Peter 2:2 | “As newborn babes, desire the sincere milk of the word, that ye may grow thereby:” | Early manuscripts widely preserve the following reading: “that you may grow thereby unto salvation.” It therefore appears that the phrase “unto salvation” (εἰς σωτηρίαν, eis sōtērian) was lost at some point. |

| 11. | Revelation22:14 | “Blessed are they that do his commandments, that they may have right to the tree of life, and may enter in through the gates into the city.” | The reading “they that do his commandments” is only attested in very late manuscripts, whereas the earliest widely attested reading is: “Blessed are those who wash their robes.” As the Greek phrase “that do his commandments,” οἱ ποιοῦντες τὰς ἐντολὰς, could look like the phrase “who wash their robes,” οἱ πλύνοντες τὰς στολὰς, perhaps the rendering represents a simple misreading that was perpetuated in later manuscripts. For “robes washed,” see also Revelation 7:14. |

| 12. | Revelation 22:19 | “And if any man shall take away from the words of the book of this prophecy, God shall take away his part out of the book of life, and out of the holy city, and from the things which are written in this book.” | The phrase “book of life” is an error that appears in the KJV because Erasmus made an error in his Greek version of the New Testament. The reading here should instead be “tree of life.” When Erasmus provided the last six verses of Revelation, he relied on a copy of the Latin Vulgate where a scribe had mistakenly miscopied the correct word ligno (“tree”) as libro (“book”). |

Appendix: Ancient Texts of the New Testament

In what follows, I provide a brief overview of the principal ancient manuscripts that preserve the Greek text of the New Testament. These texts form the basis upon which scholars today attempt to determine and reconstruct the earliest readings of the New Testament.

Codex Alexandrinus

A fifth-century AD codex that contains every book in the New Testament except portions of Matthew (chapters 1–24), John (chapters 6–8), and 2 Corinthians (chapters 4–12). This codex also includes 1 and 2 Clement as well as the majority of the Septuagint (LXX).[29] It is called the Codex Alexandrinus because its earliest known location was the city of Alexandria in Egypt. It is written with capital Greek letters (uncial script) and is laid out with two columns per page. Cyril Lucar, Patriarch of Alexandria during the early part of the seventeenth century, sent this bible as a gift to King James I of England. James subsequently died (in March 1625) before it arrived, and so it was instead presented to his successor Charles I in 1627. Today it is housed in the British Library.

Codex Bezae

A fifth- or sixth-century codex that contains many of the books in the New Testament with the exception of Matthew chapters 1, 6–9, and 27; Mark chapter 16; John chapters 1–3; Acts chapters 8–10 and 22–28; Romans chapter 1; James; 1 and 2 Peter; 1, 2, and 3 John; Jude; and Revelation. In various places, this bible contains a number of unique readings that are not attested elsewhere, though many of these readings probably represent later interpolations to the various New Testament books. This ancient bible is a Greek and Latin diglot, meaning that it contains on the left-hand page the Greek text in a single column and on the right-hand page the Latin text in a single column. It is called the Codex Bezae because it once belonged to Theodore Beza, a sixteenth-century French reformer, who donated it to Cambridge University in 1581. This bible is still in the possession of Cambridge University.

Codex Sinaiticus

A fourth-century codex that contains complete copies of every book in the New Testament. It also contained the Epistle of Barnabas and the Shepherd of Hermas along with the Septuagint. It could even potentially be one of the fifty bibles commissioned by Constantine in the year AD 331 and produced under the direction of Eusebius of Caesarea. This bible is written with four Greek columns per page. It was discovered by Constantin Tischendorf in the 1850s at St. Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai (hence the name Codex Sinaiticus), and he subsequently took it back to St. Petersburg. In 1933 this codex was purchased by the British government for ₤100,000.00. This codex is presently housed in the British Library.

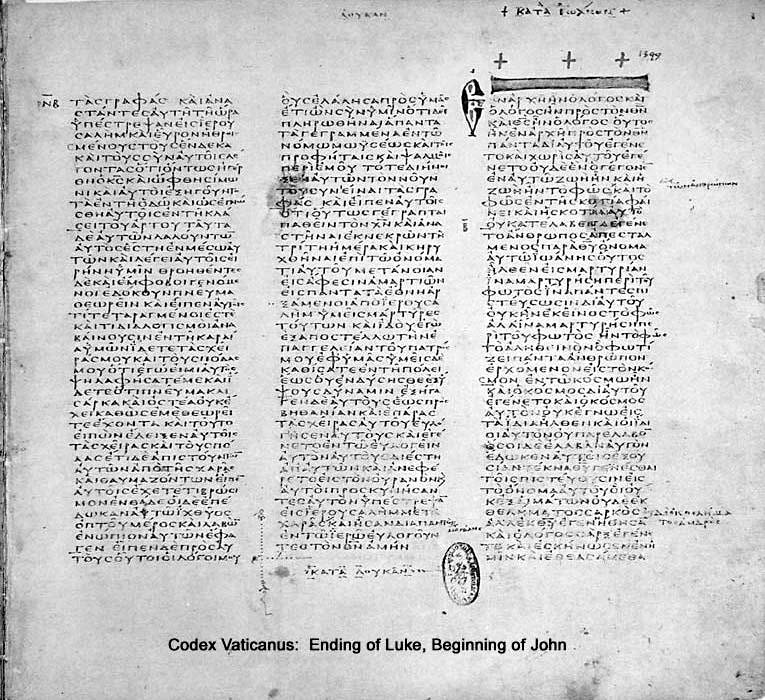

Codex Vaticanus, page with ending of Luke and beginning of John. Public domain.

Codex Vaticanus, page with ending of Luke and beginning of John. Public domain.

Codex Vaticanus

A fourth-century codex that contains complete copies of all the books in the New Testament with the exception of part of the Epistle to the Hebrews (chapters 9–13), all the pastorals (Titus and 1 and 2 Timothy), and Revelation. Like Codex Sinaiticus, it may have even been one of the fifty bibles commissioned by Constantine and produced under the direction of Eusebius of Caesarea. It is written with capital Greek letters (uncial script) and is laid out with three columns of text per page. It is called the Codex Vaticanus because it is in the possession of the Vatican Library.

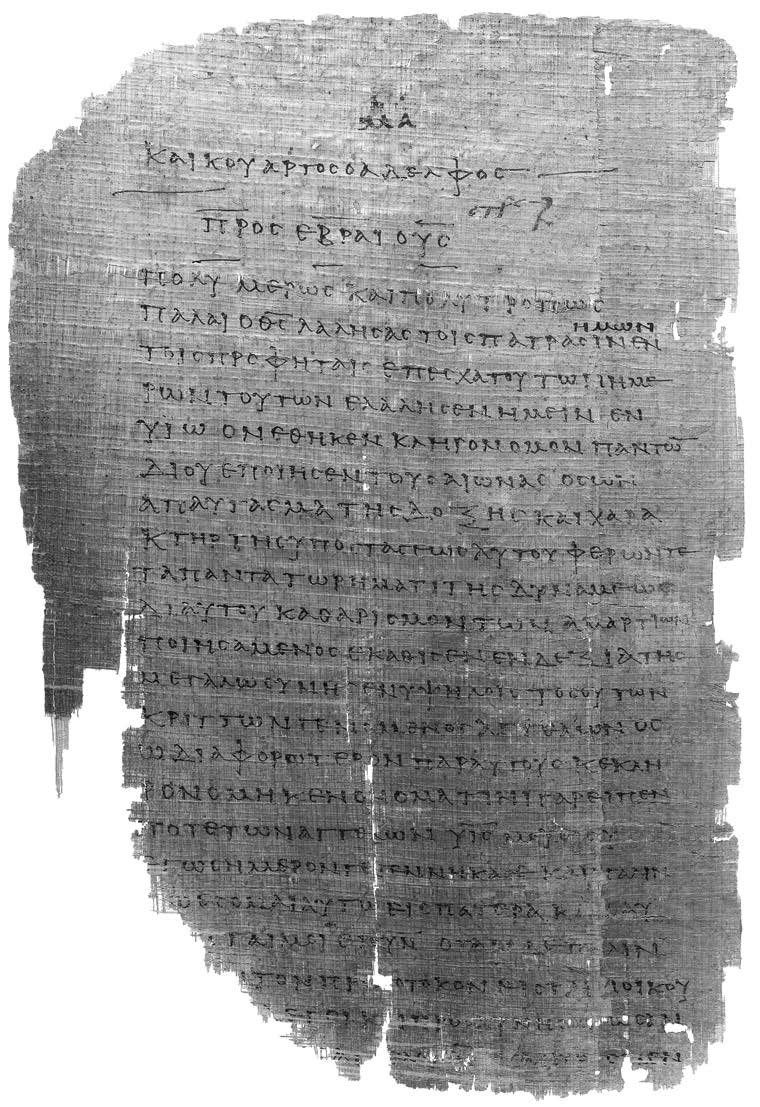

Papyri

Page from ?46, end of Romans and start of Hebrews

Page from ?46, end of Romans and start of Hebrews

(ca. AD 200). Courtesy University of Michigan.

Various papyri discovered from Egypt that date between the AD second and sixth centuries help supplement our knowledge of the text of the New Testament, as such fragments preserve the earliest attestations of select New Testament passages. To date, there are about 125 known New Testament papyrus fragments (numbered 1, 2, 3, and so forth) that range in length from fragments containing a verse or two to entire codices containing a certain book of the New Testament. These fragments are very useful for the textual history of the New Testament since they are the earliest evidence we have and can predate the oldest ancient bibles (mentioned above) by as many as 200–250 years. Notable fragments include 52, a small fragment that contains John 18:31–33 on one side and 18:37–38 on the other and dates to the first half of the AD second century (earliest known piece of the New Testament); 46, the oldest substantial New Testament manuscript that dates to ca. AD 200 and contains many of Paul’s letters; 66, a virtually complete codex of John’s Gospel that dates to ca. AD 200.[30]

Further Reading

Blumell, Lincoln H. "A Text-Critical Comparison of the King James New Testament with Certain Modern Translations." Studies in the Bible and Antiquity 3 (2011): 67-127.

Brandt, Pierre-Yves. "Manuscripts grecs utilisés par Erasme pour son édition de Novum Instrumentum de 1516." Theologische Zeitschrift 54 (1998): 120-24.

Burke, David G., John F. Kutsko, and Philip H. Towner, eds. The King James Version at 400. Assessing Its Genius as Bible Translation and Its Literary Influence. Atlanta: SBL, 2013.

De Jonge, Henk Jan. "Novum Testamentum a nobis versum: The Essence of Erasmus' Edition of the New Testament." Journal of Theological Studies 35 (1984): 394-413.

Elklertson, Carol F. "New Testament Manuscripts, Textual Families, and Variants." In How the New Testament Came to Be, edited by Kent P. Jackson and Frank F. Judd Jr., 93-108. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2006.

Metzger, Bruce, and Bart Ehrman. The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration. 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Notes

[1] A very similar version of this paper was first published by the author in “The Text of the New Testament,” in The King James Bible and the Restoration, ed. Kent P. Jackson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2011), 61–74. I thank the Religious Studies Center for permission to use this piece as the basis for the present chapter.

[2] A tenth and final edition of Beza’s Greek New Testament was published posthumously in 1611. Only four of the editions published by Beza (1565, 1582, 1588–89, and 1598) were independent editions, as the others were simply smaller reprints. See Bruce Metzger and Bart Ehrman, The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration, 4th ed. (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 151–52.

[3] See F. H. A. Scrivner, ed., The New Testament in Greek: According to the Text Followed in the Authorised Version Together with the Variations Adopted in the Revised Version (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1908), vii.

[4] In 1569 a Syriac translation of the New Testament was first published by Immanuel Tremellius. In Beza’s subsequent editions (post-1569), he consulted the Syriac. On Tremellius’s Syriac New Testament, see Kenneth Austin, From Judaism to Calvinism: The Life and Writings of Immanuel Tremellius (Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2007), 125–44.

[5] This codex was subsequently named after Beza. The reason for the different spelling, Bezae instead of Beza, is that it reflects the Latin genitive case, which typically expresses possession. Codex Bezae literally means “Codex of Beza.” In 1581 Beza donated this bible to Cambridge University, where it remains to this day.

[6] This codex contains most of the books in the New Testament, with the exception of Matthew 1, 6–9, and 27; Mark 16; John 1–3; Acts 8–10 and 22–28; Romans 1; James; 1 and 2 Peter; 1, 2, and 3 John; Jude; and Revelation. It is believed that prior to coming into Beza’s hands, this codex had come from Lyon, France. On the history of Codex Bezae, see David C. Parker, Codex Bezae: An Early Christian Manuscript and Its Text (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 46–48.

[7] This codex contains the Pauline Epistles. The first seven verses of Romans (in Greek) are missing due to a lacuna. Additionally, Romans 1:27–30 and 1 Corinthians 14:13–22 are the additions of later hands. The ordering of the Pauline epistles is standard, and Hebrews is placed after Philemon. On this codex, see Kurt Aland and Barbara Aland, The Text of the New Testament: An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism, trans. Erroll F. Rhodes (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1995), 110.

[8] Metzger and Ehrman, Text of the New Testament, 151.

[9] For an in-depth biographical sketch of Stephanus, see Elizabeth Armstrong, Robert Estienne, Royal Printer: An Historical Study of the Elder Stephanus (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1954).

[10] Since his critical apparatus contained a number of textual variants, it created a stir in Paris and provoked a series of severe attacks from the Sorbonne. To escape the hostilities the following year (1551), he moved to Geneva, where he would later become a Calvinist.

[11] The chapter divisions as we know them today were first introduced in the thirteenth century by Stephen Langton.

[12] There are a couple of reasons why it took over half a century after the invention of the printing press in the middle of the fifteenth century for a printed edition of the Greek New Testament to appear. First, since Latin was the official ecclesiastical language of the church and Jerome’s Vulgate was regarded as the biblical text, Greek was initially seen as secondary in importance. Second, Greek fonts were more difficult to manufacture than Latin fonts, especially since Greek required a number of diacritical marks. See Metzger and Ehrman, Text of the New Testament, 137–38.

[13] There may have been earlier negotiations between Froben and Erasmus about producing a Greek edition of the New Testament, but this is not certain. See Metzger and Ehrman, Text of the New Testament, 142.

[14] Metzger and Ehrman, Text of the New Testament, 142.

[15] One manuscript, which contained Acts and the Pauline letters (Codex 2ap), was obtained from the family of Johann Amerbach of Basel. See William W. Combs, “Erasmus and the Textus Receptus,” Detroit Baptist Seminary Journal 1 (Spring 1996): 45.

[16] On these manuscripts, see Metzger and Ehrman, Text of the New Testament, 142–44; P.-Y. Brandt, “Manuscrits grecs utilises par Erasme pour son édition de Novum Instrumentum de 1516,” Theologische Zeitschrift 54 (1998): 120–24; Aland and Aland, Text of the New Testament, 4–6; C. C. Tarelli, “Erasmus’s Manuscripts of the Gospels,” Journal of Theological Studies 44 (1943): 155–62. Codex 1eap simply means that this codex contained e (Gospels [= evangelists]), a (Acts), and p (Pauline Letters).

[17] Though Francisco Ximes de Cisneros originally conceived of the project and played a critical role in its publication, there were numerous other scholars who helped out. When the project was completed, it occupied six volumes. The first four volumes covered the Old Testament, the fifth volume the New Testament, and the sixth and final volume contained various Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek dictionaries and study aids. While the fifth volume was completed and printed in 1514, its publication and dissemination had to wait until 1517, when the four volumes of the Old Testament were completed. As a set, its publication was further delayed until Pope Leo X sanctioned it, which he did in 1520. Thus, it did not begin to be distributed widely before 1522. The name of this bible is derived from the Latin name of the town Alcalá (Latin: Complutum), where it was printed. The word polyglot is of Greek origin and simply refers to any book that contains a side-by-side version of different languages of the same text. For the Old Testament, the pages contained the Hebrew text, Jerome’s Latin Vulgate, and the Greek Septuagint in three parallel columns. For the New Testament, there were simply the Greek and Latin texts in parallel columns. For a more detailed treatment of this bible, see Julián Martín Abad, “The Printing Press at Alcalá de Henares, The Complutensian Polyglot Bible,” in The Bible as Book: The First Printed Editions, ed. Kimberly Van Kampen and Paul Saeger (New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press, 1999), 101–18; Metzger and Ehrman, The Text of the New Testament, 138–42.

[18] Erasmus chose the phrase Novum Instrumentum instead of Novum Testamentum because he believed that the word Instrumentum better conveyed the idea of a decision put down in writing than did the word Testamentum, which “could also mean an agreement without a written record.” See H. J. de Jonge, “Novum Testamentum a nobis versum: The essence of Erasmus’ Edition of the New Testament,” Journal of Theological Studies 35 (1984): 396. In the second edition of Erasmus’s Greek New Testament, he would change the title to Novum Testamentum.

[19] De Jonge, “Novum Testamentum a nobis versum,” 395, describes the first edition as follows: “The Latin and Greek texts of the Gospels and Acts fill pages 1–322, the texts of the Epistles and Revelation pages 323–4 and a second series of pages numbered from 1 to 224. Immediately after this, the Annotationes fill pages 225–675.” It was designed more as a new Latin translation than a Greek one, where the Greek came to be used to support his various Latin readings.

[20] Metzger and Ehrman, Text of the New Testament, 145. In 1518 the Venetian printer Aldus Manutius issued a Greek New Testament that was essentially a copy of Erasmus’s first edition. In fact, it so closely copied Erasmus’s text that many of the typographical errors were simply reprinted. Somewhat ironically, in later years Erasmus would not infrequently defend certain of his readings by reference to the Aldine version without realizing that this version was simply a copy of his own text.

[21] All told, between the first and second editions about 3,300 copies were produced. See Metzger and Ehrman, Text of the New Testament, 145. When Luther issued his German translation of the New Testament in 1522, he relied principally on Erasmus’s 1519 edition.

[22] This manuscript, known today as Codex Montfortianus or as Codex Britannicus by Erasmus, dates to the early sixteenth century. It contains the entire Greek New Testament written in miniscule script with one column per page. It has long been recognized that this manuscript was basically produced to induce Erasmus to include the Johannine Comma, since there was now a Greek manuscript that contained these verses. It is currently housed at Trinity College in Dublin. See Aland and Aland, Text of the New Testament, 129.

[23] On the dubious nature of the Johannine Comma, see Bruce Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, 2nd ed. (New York: United Bible Societies, 1994), 647–49; Michael Welte, “Earliest Printed Editions of the Greek New Testament,” in Van Kampen and Saenger, Bible as Book, 120–21.

[24] Quoted in Metzger and Ehrman, Text of the New Testament, 152.

[25] Codex Vaticanus is a fourth-century codex that contains complete copies of all the books in the New Testament (see Appendix). It may be noted, however, that Erasmus might have known about Codex Vaticanus even though he did not use it in any substantial way in the making of his Greek New Testament. In his Annotationes in Novum Testamentum, when defending his omission of the Johannine Comma (1 John 5:7b–8a) in the first two editions of his Greek New Testament, Erasmus reports that he had the librarian of the Vatican consult a very ancient copy of the Greek New Testament and that it did not contain these verses: “To this Paolo Bombasio, a learned and blameless man, at my enquiry described this passage [1 John 5:7–8] to me word for word from a very old codex from the Vatican library, in which it does not have the testimony ‘of the father, word, and spirit.’ If anyone is impressed by age, the book was very ancient; if by the authority of the Pope, this testimony was sought from his library.” Translation of the Latin text is my own. Latin text taken from Anne Reeve and M. A. Screech, eds., Erasmus’ Annotations on the New Testament: Galatians to the Apocalypse (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1993), 770.

[26] For a more in-depth discussion of the endings of Mark, see Lincoln H. Blumell, “A Text-Critical Comparison of the King James New Testament with Certain Modern Translations,” Studies in the Bible and Antiquity 3 (2011): 89–95. This article can be accessed online at http://

[27] For an in-depth discussion of these verses, see Lincoln H. Blumell, “Luke 22:43–44: An Anti-Docetic Interpolation or an Apologetic Omission?” TC: A Journal of Biblical Textual Criticism 19 (2014): 1–35. This article can be accessed online at http://

[28] For a more in-depth discussion of this passage, see Blumell, “A Text-Critical Comparison,” 107–13.

[29] The Septuagint or LXX, as it is commonly known, is simply the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible.

[30] For a useful introduction to the various New Testament papyri, see: Philip W. Comfort and David Barret, eds., The Text of the Earliest New Testament Greek Manuscripts: New and Complete Transcriptions with Photographs (Wheaton, Il: Tyndale House, 2001).