Greco-Roman Philosophy and the New Testament

Bryce Gessell

Bryce Gessell, "Greco-Roman Philosophy and the New Testament," in New Testament History, Culture, and Society: A Background to the Texts of the New Testament, ed. Lincoln H. Blumell (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 178-193.

Bryce Gessell is a PhD student at Duke University studying the history and philosophy of science.

When we read the New Testament, we enter a world that is in many ways foreign to us: the most important events happened two millennia ago, they took place in a distant land, and they were lived by people whose society contrasts sharply with our own. While these barriers do not stop us from feeling the power of Christ’s words in the Sermon on the Mount, for example, he still spoke those words at a particular time and place to a particular group of people. As Nephi put it, he spoke “unto men according to their language” (2 Nephi 31:3). Language is more than just a form of communication—it is a way of seeing the world and one’s place in it (see 1 Nephi 1:2). In this chapter, I will use the word language in Nephi’s broad sense. The more we know about the language of the New Testament, the more we will draw from the fertile richness of its pages.

This chapter considers the philosophical part of that language. Philosophy embraces some of the deepest questions we can ask: What is existence, and how do existing things relate to each other? How do we come to know the world? How should we live in that world and with one another? Though it is not possible to deal with the nuances of any one philosopher here, this chapter will offer an overview of the major Greco-Roman philosophies before, during, and shortly after the time of Christ. By familiarizing ourselves with the philosophical languages spoken among these groups, we will see how their answers to deep questions form an essential part of the New Testament and our reading of it.

The Beginning: Ancient Greek Philosophy

Western philosophy begins with a group of thinkers in Miletus, an ancient city located in modern-day Turkey.[1] The “Milesians”––Thales (ca. 600 BC), his pupil Anaximander (ca. 610–546 BC), and Anaximenes (ca. 585–528 BC)––were interested in questions about what the world was made of and how it worked.[2] Instead of relying on gods and fate to explain things, however, the Milesians began to answer their questions in terms of natural principles. Thales, for example, thought that the primary constituent of all existing things was water: “from water come all things and into water do all things decompose.”[3] Anaximenes, on the other hand, took air to be the most fundamental element. Other figures with alternative views arose elsewhere, such as Heraclitus of Ephesus (ca. 500 BC), Empedocles of Acragas (ca. 495–435 BC), and Democritus of Abdera (ca. 460–370 BC).[4]

The general name for these early philosophers is “Presocratic,” but that term is somewhat misleading. Though the Milesians did in fact precede Socrates, other Presocratic authors were his contemporaries. And while these early theorists tend to answer philosophical questions in many different ways, they share a commitment to certain methods for answering. Rather than appealing to supernatural beings, they are more likely to use natural phenomena in explaining the world; thus they are commonly called “natural philosophers.” Natural philosophy is the ancestor of modern science—it is a way of approaching the world that uses causes within the natural world in order to explain it. The departure from mythology toward a more scientific sort of investigation is one of the early marks of Western philosophical inquiry.

Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle—the major voices of Greek philosophy—followed the early natural philosophers. There are no more important philosophers in the ancient world than these three. We will, however, cover them only briefly here, for they were not so directly influential in the New Testament world as their later notoriety might suggest.

Socrates (469–399 BC)[5]

A one-time soldier in the Peloponnesian War, Socrates lived his later years in Athens. He wandered the city looking to engage (or trap, depending on whom you asked) its citizens in conversation on ethical topics such as the nature of piety or love. His Socratic method consisted of asking questions designed to attack or defend a certain point of view or to establish accepted principles in some investigation. He considered himself a “gadfly” who took up the responsibility of stirring the state and its people into action.[6] He was eventually charged with impiety and corruption of Athens’s youth; he was found guilty and executed.

We know of Socrates from works by Plato, Xenophon, and (to some extent) the playwright Aristophanes. Since Socrates wrote nothing himself, it can be difficult to tell which views in these works really belonged to the historical Socrates and which belonged to the authors themselves.[7]

Plato (424–347 BC)[8]

Plato was Socrates’s disciple and established his own school in Athens called “the Academy.” He wrote voluminously on virtually every topic in philosophy. His texts are mostly dialogues, or conversations, between a main speaker (often Socrates) and his companions (sometimes called “interlocutors”). He held that the world we now inhabit is a shadow of a higher, more perfect, and unchanging reality—the world of the “Forms.” Mundane objects are what they are because they “participate in,” or stand in some relation to, certain Forms. A dog is a dog, for instance, because it participates in the form Dog; the same is true for humans, chairs, and other things. The objects we know and experience daily are but imperfect copies of more genuine realities.

For Plato, the function of philosophy is to free the soul from the prison of the body in order for it to contemplate the Forms more directly. His allegory of the cave may be one way of thinking about this process.[9] By gaining knowledge, we free ourselves from the deceptive and harmful images of things experienced in bodily reality. Philosophy gradually leads our soul from captivity as we begin to grasp the real nature of existence. The truest light—the Form of the Good—illuminates us upon our leaving the cave. For Plato, our souls had knowledge before birth and will outlast our bodies after death.

Aristotle (384–322 BC)[10]

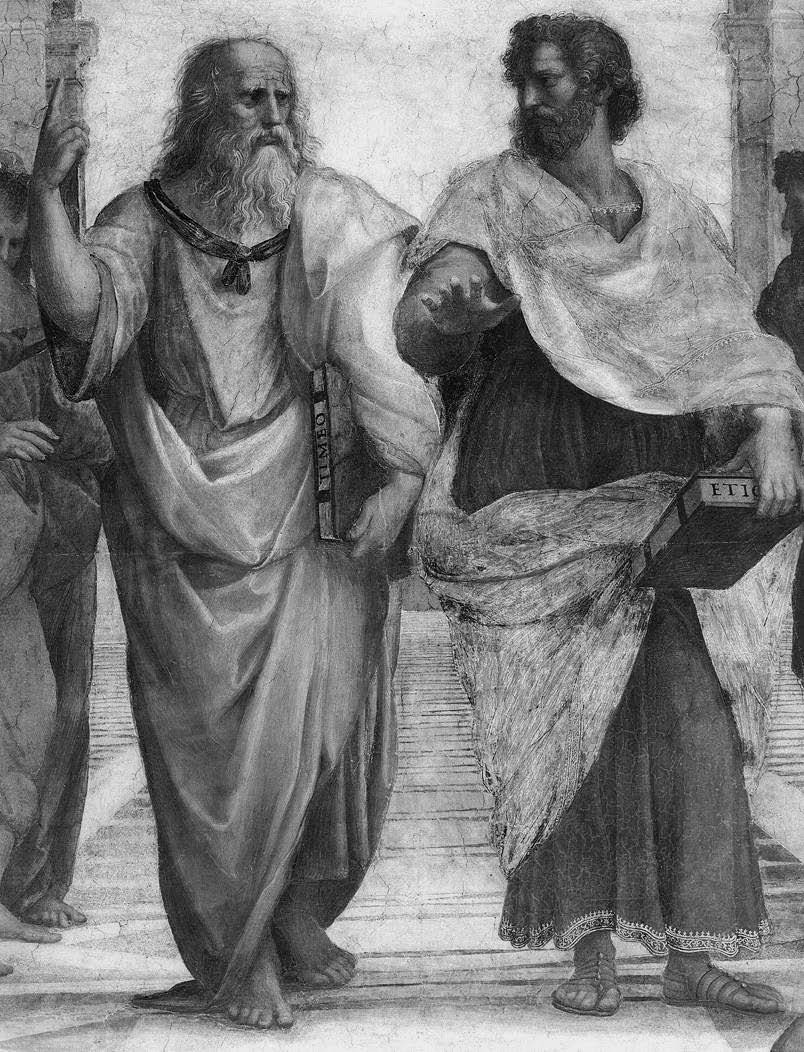

Plato (left) and Aristotle (right), as depicted in Raphael’s

Plato (left) and Aristotle (right), as depicted in Raphael’s

The School of Athens (1510-1511). Plato’s gesture

toward the heavens and Aristotle’s toward the earth

are thought to represent the different approaches they

took to explaining the natural world. Plato holds a copy

of the Timaeus, his dialogue on cosmology and natural

philosophy; Aristotle carries his Ethics, likely the Nicomachean

Ethics, a work on virtue and happiness.

Aristotle in turn was Plato’s student at the Academy. Following Plato’s death, Aristotle began to tutor Alexander the Great but later returned to Athens to found his own school of philosophy, the Lyceum. Aristotle also wrote on many topics and developed systematic theories in logic and science. Unlike Plato, however, Aristotle did not believe that higher forms of knowledge required the soul to apprehend the Forms. He saw knowledge as a result of information gained about the external world from the senses. On this view, more general knowledge comes from the mind’s capacity to abstract away from particular truths in order to grasp universal ones, as it appreciates the essences of various objects.

In Raphael’s painting The School of Athens, Plato is shown talking to Aristotle with his finger pointing upward, while Aristotle responds by gesturing toward the world below. INSERT IMAGE 1 This famous image illustrates the different approaches these philosophers are thought to have taken on questions about the world and humanity.

Early Greek philosophy in conclusion

The language of Western philosophy begins with the thinkers we call the “Presocratics” before moving to their Athenian successors, including Plato and Aristotle. These figures introduced many of the terms, methods, and insoluble problems that are fundamental to the practice of philosophy. In many ways, the philosophical shifts discussed below—and much of Western philosophy in general—stem from questions and answers proposed by Plato and Aristotle.[11] As we will see, this is as true for religion as it is for philosophy.

Hellenistic Philosophy, Wisdom, Epicureanism, and Stoicism

After the major figures of Greek philosophy, we begin to find movements and philosophical doctrines more directly associated with the New Testament. We also begin to see greater development of philosophical terms and concepts that will eventually impact Christian theology. In a familiar passage from the book of Acts, we read about Paul encountering certain philosophical movements:

And they that conducted Paul brought him unto Athens: and receiving a commandment unto Silas and Timotheus for to come to him with all speed, they departed. Now while Paul waited for them at Athens, his spirit was stirred in him, when he saw the city wholly given to idolatry. Therefore disputed he in the synagogue with the Jews, and with the devout persons, and in the market daily with them that met with him. Then certain philosophers of the Epicureans, and of the Stoicks, encountered him. And some said, What will this babbler say? other some, He seemeth to be a setter forth of strange gods: because he preached unto them Jesus, and the resurrection. And they took him, and brought him unto Areopagus, saying, May we know what this new doctrine, whereof thou speakest, is? For thou bringest certain strange things to our ears: we would know therefore what these things mean. (For all the Athenians and strangers which were there spent their time in nothing else, but either to tell, or to hear some new thing.) Then Paul stood in the midst of Mars’ hill, and said, Ye men of Athens, I perceive that in all things ye are too superstitious. For as I passed by, and beheld your devotions, I found an altar with this inscription, TO THE UNKNOWN GOD. Whom therefore ye ignorantly worship, him declare I unto you. (Acts 17:15–23)

Here Paul meets adherents of two philosophical groups, the Epicureans and the Stoics. Both groups play a critical role in the philosophical background of the New Testament. These systems of thought belong to an era known today as the Hellenistic period. In ancient Greek, the country of Greece was known as Hellas (Ἑλλάς). Though Plato and Aristotle were also Greek, we use the term Hellenistic philosophy to refer to the period following Aristotle.[12] The period is worth looking at in greater detail.

Hellenistic philosophy

Hellenistic philosophy includes much more than Epicureanism and Stoicism. The Cynics, for example, began a philosophical movement around the time of Plato, before the beginning of the Hellenistic period.[13] Antisthenes (445–365 BC), their alleged founder, was a contemporary of Plato and was, like Plato, a student of Socrates. Later Cynics developed a philosophy of life based on virtue and harmony with nature. The goal of a Cynic was εὐδαιμονία (eudaimonia), or “happiness.” “Vanity” (τῦφος, tuphos) stands in the way by clouding the mind with delusion. A life free from corrupting influences like bodily temptations, wealth, and social power eliminate vanity and lead to eudaimonia. The Cynic lifestyle was sometimes taken to ascetic extremes, most famously by the eccentric Diogenes of Sinope (404–323 BC), sometimes called “Diogenes the Dog” (the Greek word for “cynic” meant “dog-like”). A famous (and perhaps apocryphal) story shows his philosophical commitments in action. Diogenes used a cup to drink out of the river but one day came across a child drinking with his hands. Disgusted with himself, Diogenes cast away his cup and exclaimed, “A child has beaten me in plainness of living.” He threw his bowl away in a similar manner upon seeing a child eat on a piece of bread instead of a plate.[14]

A critical feature in much of Hellenistic philosophy is a shift away from natural philosophy and issues about the general properties of existing things (called “metaphysical” issues). This shift brought a renewed emphasis on ethics and ways of living life. In Plato, Aristotle, and many of the Presocratics, we find philosophers asking questions about the world and its place in the universe: their interests range from inquiries about the tiniest constituents of matter to the earth’s place in the cosmos as a whole.

As we will see below, many Hellenistic philosophers are willing to address questions about the natural world. Like Plato and Aristotle, they have ideas about what causes things to happen in nature, and some of these ideas are comprehensive and systematic. But their purpose in offering such explanations is not necessarily to gain an understanding of the world for its own sake. Rather, in many cases these post-Aristotelian philosophers take an interest in nature in order to frame and justify their own views about how to live. The qualities of divinity, the way we gain knowledge about our environment, the way we reason—all these issues matter in determining the correct approach to personal conduct.

A major part of this shift toward ethics is the influence of Socrates. Though he left no written record, Socrates’s self-conscious reflection on moral issues—and his stubborn commitment to his ideals—had a long-lasting effect on Greek philosophers. The Hellenistic focus on proper conduct parallels the emphasis of Christ himself and his apostles in much of New Testament scripture. In the Gospels, Christ says nothing about whether the earth goes around the sun or whether atoms are the fundamental building blocks of everything else, but on nearly every page we find guidance about how to see ourselves and relate to others.

Hellenistic philosophy is a rich tradition with many branches to explore.[15]

Worldly wisdom and philosophy in the New Testament

We began this section by quoting Paul’s experience in Acts 17. The New Testament addresses Greek philosophy in other ways as well, though they are not always so obvious. The first chapter of 1 Corinthians is a good example. After greeting the Church at Corinth and praising Christ, Paul begins a denunciation of the world and its learning:

For the preaching of the cross is to them that perish foolishness; but unto us which are saved it is the power of God. For it is written, I will destroy the wisdom of the wise, and will bring to nothing the understanding of the prudent. Where is the wise? where is the scribe? where is the disputer of this world? hath not God made foolish the wisdom of this world? For after that in the wisdom of God the world by wisdom knew not God, it pleased God by the foolishness of preaching to save them that believe. For the Jews require a sign, and the Greeks seek after wisdom: But we preach Christ crucified, unto the Jews a stumbling block, and unto the Greeks foolishness; But unto them which are called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ the power of God, and the wisdom of God. Because the foolishness of God is wiser than men; and the weakness of God is stronger than men. For ye see your calling, brethren, how that not many wise men after the flesh, not many mighty, not many noble, are called: But God hath chosen the foolish things of the world to confound the wise; and God hath chosen the weak things of the world to confound the things which are mighty. (1 Corinthians 1:18–27)

The key word in the passage is “wisdom,” or σοφία (sophia). According to Paul, God will “destroy the wisdom of the wise”; despite the Greeks’ seeking for it, this worldly wisdom is not enough to know God. Paul chooses his words carefully in this passage. The Greek word φιλοσοφία (philosophia) is a combination of the words philo- (“love”) and -sophia (“wisdom”); therefore, philosophy is literally the “love of wisdom.” Paul describes the Greeks as wisdom-seekers, but he has in mind their tendency toward philosophy and worldly knowledge. Perhaps he would have said of the Hellenistic philosophers of his day, as we read in 2 Timothy, that they were “ever learning, and never able to come to the knowledge of the truth” (2 Timothy 3:7; see Acts 17:21).

In connection with the criticism of worldly wisdom in 1 Corinthians 1, we find the New Testament’s only use of the Greek word φιλοσοφία (“philosophy”) in Colossians 2:

As ye have therefore received Christ Jesus the Lord, so walk ye in him: Rooted and built up in him, and stablished in the faith, as ye have been taught, abounding therein with thanksgiving. Beware lest any man spoil you through philosophy and vain deceit, after the tradition of men, after the rudiments of the world, and not after Christ. (Colossians 2:6–8)

Here we see a marked split between two ways of viewing philosophy. For Plato, the acquisition of knowledge through philosophy was the key to liberating the soul from the prison of the body. Before philosophy, one’s soul was “imprisoned in and clinging to the body, and . . . it is forced to examine other things through it as through a cage and not by itself, and . . . it wallows in every kind of ignorance.”[16] The true course is to be a person “who has truly spent his life in philosophy” and so will be “of good cheer in the face of death and . . . very hopeful that after death he will attain the greatest blessings yonder.”[17]

In contrast to Plato, Paul warns against the seductive power of the sorts of philosophies the Greeks used to seek truth. He claims that these worldly manners of thought, handed down in the teachings of men, may “spoil” us. The way we use spoil today gives a misleading impression of the meaning in this verse. The Greek word is a form of συλαγωγέω (sulagōgeō), which means “to gain control of by carrying off as booty . . . in imagery of carrying someone away from the truth into the slavery of error.”[18] Note the powerful reversal of the Platonic metaphor. Leaving Plato’s cave and ascending to the light and truth required philosophy; on Paul’s interpretation, it is as though philosophy takes one away from the light and back down into the darkness (see 2 Corinthians 4:5–6; Ephesians 5:14). Once again Paul has chosen his words with great care and foresight. Just before his warning about philosophy, he reminds his audience that only “in [Christ] are hid all the treasures of wisdom (σοφία, sophia) and knowledge” (Colossians 2:3). The love of wisdom, separated from the treasure of Christ, leads to nothing but ignorance.

Returning now to Paul’s encounter with the Epicureans and Stoics, on meeting Paul, some of these philosophers said that he seemed “to be a setter forth of strange gods,” while others asked themselves, “What will this babbler say?” (Acts 17:18). The epithet babbler is σπερμολόγος (spermologos), an insult made to one who unsystematically gathers pieces of information to create a patchwork view of the world.[19] The term seems to be an inside joke. Both Plato and Aristotle were comprehensive philosophers: their ideas reached from the smallest bits of matter to the largest bounds of the universe and touched on almost everything in between. Both the Epicureans and the Stoics inherited this Greek concern with system-building. At least at the time they spoke to Paul, Christian thought must have seemed to those at Mars’ Hill as hardly even worth being called a patchwork. To see how fledgling Christianity differed from these Hellenistic views, let’s take a closer look at both schools of thought.

Epicureanism

Like other movements in Hellenistic philosophy, the principle aims of Epicureanism involved morality: they concerned the way one should live. Epicurus (341–270 BC), the school’s founder, was born about two decades after Aristotle. Some of Epicurus’s original writings have survived, detailing his ideas about physics, astronomy, and ethics.[20] He divided philosophy into three groups: Canonic (Logic), the treatment of which comprises the introduction to his system; Physics, which deals with nature; and Ethics, which treats life and conduct. The hallmark of Epicurean physical theory is atomism, which posited indivisible, fundamental particles whose interactions give rise to the objects and events we experience (the earliest atomists, Leucippus and Democritus, date back to the fifth century BC). Experience itself is the arbiter of truth, which forms a philosophical view of knowledge now called “empiricism.”[21]

In contemporary usage the adjective epicurean describes a person who is preoccupied with sensual pleasures, but this use of the term is not faithful to Epicurean ethical theory. Epicureanism was a form of hedonism––the idea that pleasure is the ultimate good—but the “pleasures” Epicurus had in mind were not necessarily the same as the sensual pleasures of the body we often think of when we hear the epithet. In fact, Epicurus tended to describe the good life in negative terms—that is, as the absence of mental distress and physical pain. This state, called ἀταραξία (ataraxia) or “ataraxy,” is the goal of life for Epicurus. Intense physical pleasures might even bring their own kind of trouble, for we feel distress at not having them after getting a taste of what they are like.

Epicurus’s emphasis on what is material, or made of matter, led him to claim that the soul too is made of atoms. The physical soul was an important part of Epicurus’s teachings on death. The soul cannot last forever because it is made of material things; therefore it is not immortal, and concerns about immortality should not motivate us any one way in action: “a right understanding that death is nothing to us makes the mortality of life enjoyable, not by adding to life an illimitable time, but by taking away the yearning after immortality.”[22] Epicurus, however, was not an atheist. He told Menoeceus, the recipient of his letter on ethics, that he should “believe that God is a living being immortal and blessed. . . . For verily there are gods, and the knowledge of them is manifest; but they are not such as the multitude believe.”[23] Common notions of God are impious and false, in fact, and only a true understanding of the divine could help one live the correct kind of life. That true understanding characterizes God as an untroubled being, uninvolved in human cares and concerns.

Epicurus died in 270 BC, but his philosophical system long outlived him. Philodemus (110–40 BC) and Lucretius (99–55 BC) were two important figures in the later Epicurean tradition. The latter’s only surviving work is a poem called On the Nature of Things (De rerum natura). This text discusses atoms and the void they move in, criticizes religion, and extols simple goods, thereby covering the crucial issues in Epicureanism as well as many other topics.[24] Epicureanism following Lucretius enjoyed a prominence that lasted several hundred more years.

The Epicureanism alive in the time and regions of the New Testament was more or less the same as the traditions outlined by Epicurus himself. The book of Acts tells us that these Epicureans, or those that knew them, had erected an altar with the inscription “TO THE UNKNOWN GOD” (Acts 17:23). Such a god is not exactly the god of Epicurus, who affirmed that god was known to some degree. But the spirit of the inscription fits the mindset of Epicurean philosophy. Paul’s speech to these philosophers emphasizes the personal nature of God and his involvement in human affairs: “God . . . made the world and all things therein” (17:24); God “hath made of one blood all nations of men for to dwell on all the face of the earth” (17:26); in God “we live, and move, and have our being” (17:28).[25] Attributing characteristics like these to a divine being represented exactly the kind of common and superstitious notions of divinity that Epicurus had railed against. In a similar vein, Paul then mentions the Judgment and the Resurrection: “Because he hath appointed a day, in the which he will judge the world in righteousness by that man whom he hath ordained; whereof he hath given assurance unto all men, in that he hath raised him from the dead” (17:31). Verse 32 reports the reaction among his listeners—“some mocked: and others said, We will hear thee again of this matter” (see 17:18 as well). It may be that these two groups correspond to the Epicureans and Stoics, respectively.[26] The Epicurean philosophers gathered on Mars’ Hill may have been familiar with Christian doctrine, and their derisive reaction typified the Epicurean attitude toward most religions. In particular, they could not have accepted resurrection from the dead. Epicurean ideas on the soul demanded that it be paired with a body in order to perceive, and without the body the soul’s atoms could not maintain their continuity as a soul. The atoms would disperse into nothingness, and the soul would cease to exist. For Epicureans, the dispersal of the soul’s atoms is the end of life, with no possibility of reassimilation to a past identity.

Two hundred years or so after Paul, Epicureanism began to give way to other philosophical systems, including Neoplatonism and Christianity itself. The influence of Epicurus’s thought is far-reaching, however, especially in comparison to some other Hellenistic philosophies. Pierre Gassendi, a French philosopher in the first half of the seventeenth century, brought Epicurus’s ideas to prominence once again in his 1649 book Animadversiones. Ironically, one of Gassendi’s main motivations was to reconcile Epicureanism with the Christian notion of God.

Stoicism

The other philosophers mentioned in Acts 17 are the Stoics. Stoicism as a Hellenistic school of philosophy began with Zeno of Citium (334–262 BC), who was born twelve years before the death of Aristotle. Because Zeno’s original writings are lost, our knowledge of his views comes from reports made by later writers. In Zeno’s case, however, these reports are sometimes extensive. We know, for example, that he wrote a lengthy work called the Republic, perhaps as a response to Plato’s dialogue of the same name. One commentator said that Zeno’s Republic can “be summed up in this one main principle: that all the inhabitants of this world of ours should not live differentiated by their respective rules of justice into separate cities and communities, but that we should consider all men to be of one community and one polity, and that we should have a common life and an order common to us all, even as a herd that feeds together and shares the pasturage of a common field.”[27]

Like other Hellenistic systems, Stoicism encompassed a range of doctrines on the natural world, but these served as a means to support and encourage the more important ethical views. We now understand the word stoic to refer to a person who is resolute in the face of pain or opposition. Unlike epicurean and perhaps cynic, our modern term stoic does preserve some of the original meaning of the philosophical doctrine. For Stoic philosophers, the ethical ideal is the “sage” (σοφός, sophos, the adjective form of the Greek noun for “wisdom”—thus “the wise man”). A sage makes correct judgments, or judgments in accordance with nature, in order to understand the world correctly. Correct understanding frees the sage from passions, or dominant emotions, which would otherwise destroy his happiness. As one Stoic author put it, “It is not things themselves that disturb men, but their judgements about things. . . . Whenever we are impeded or disturbed or distressed, let us blame no one but ourselves, that is, our own judgements.”[28] Therefore, a sage actively creates a life by a process of ἄσκησις (askēsis), “training” or “practice,” in order to apprehend the world correctly, make appropriate judgments, and live in accordance with reason.

Although we have few actual writings of the early Stoics, Stoicism flourished among some later Roman authors, many of whose works have survived: Seneca (4 BC–AD 65), Epictetus (AD 55–155), and Marcus Aurelius (AD 121–180) are three of them.[29] These authors, especially Epictetus and Seneca, lived during the New Testament period.

We also see Stoic influence in many important concepts and terminology of Christian scripture. For the Stoics, the λόγος (logos, “word, account, reason”) is the universal reason that is basic to all existence. This same word appears in prominent passages of the New Testament, most notably at the beginning of John (1:1), where Christ is referred to as the λόγος (logos). Other important terms, such as πνεῦμα (pneuma, “breath, spirit”) and ἀρετή (aretē, “virtue, excellence”), have an important history in Stoicism as well as in Greek philosophy more broadly.

Let us return to Acts 17 one last time. Earlier we saw that, on hearing of the resurrection of the dead, the Epicurean and Stoic philosophers had two different reactions. The Epicureans mocked Paul’s doctrine because their atom-based physics precluded any possibility of a resurrection. The Stoics, on the other hand, reacted differently: “We will hear thee again of this matter” (17:32), they said. Stoicism was also a materialist philosophy and held that God was an active principle inherent in all of nature. This version of theism is sometimes called “pantheism,” from the Greek word πᾶν (pan), which means “all” or “everything”: everything is God. God therefore exists in this world, not outside or apart from it; we also exist as parts of the divine whole, and so perhaps a sort of resurrection could be possible.[30]

In this section we have taken only a brief tour through the many branches of Hellenistic philosophy, two of which—Epicureanism and Stoicism—are particularly important for the New Testament era. We saw that the common language of these branches was moral philosophy. While they did attempt to supply answers to questions about the nature of existence, the essence of matter, and our access to reality, their primary goal was to outline the proper way to live. We have also had a glimpse at some of the influence Hellenistic philosophy had on the languages and events of the New Testament itself. Paul’s meeting at Mars’ Hill is the most obvious case, but other concepts and discussions, such as σοφία (sophia, wisdom) or Paul’s exhortation against certain philosophies in Colossians 2, witness how far Greek learning extended into early Christianity.[31]

Roman Philosophy and Plotinus

The New Testament was written at a time when the ancient Mediterranean world was dominated by Rome. The Roman Empire reached far and wide and even included Jerusalem in the Roman province of Judea. In Paul’s extensive missionary travels, he never ventured outside the empire’s borders. While the geographic boundaries of the Roman Empire were relatively clear, the boundaries of what we now call “Roman philosophy” were less so. For example, in discussing the major Hellenistic philosophies, we have already named a number of important Roman philosophers: Philodemus, Lucretius, Seneca, and Marcus Aurelius. The lines between Roman philosophers and Greek and Hellenistic philosophies became blurred as Roman thinkers presented Greek philosophy in their own work, albeit from a different perspective. To this group could also be added Marcus Tullius Cicero (106–43 BC), known for his involvement in Roman politics and literature. He dealt with many philosophical issues across a prolific corpus, treating friendship, laws, divinity, and other topics. His work is a good guide to both the Roman reception of Greek philosophy and the later dissemination of Hellenistic thinking in other authors.[32]

Even though many “Roman” philosophers were in some ways carrying on the traditions of some Hellenistic schools, talking about Roman philosophy can still be useful. For one, the early Christian era points toward a changing understanding of the relationship between Christianity and philosophy. In some of the writings of Paul, we saw a deliberate warning against Greek philosophy and an implicit criticism of certain Greek philosophical ideas. These ideas spanned the duration of the New Testament, but by the time we come to later thinkers of the Roman period, we have left the events of the New Testament behind. There is still far more to say about those events, however, and their relation to philosophy. The flourishing of Roman thought helps us understand the roots and development of other philosophical systems. Some of these were to outlast Epicureanism and Stoicism, both of which lost favor in the decades following Paul.

In fact, these new Roman philosophical developments were in part a return to the important Greek thinkers of the past. From the time of Plato and Aristotle, there had always been Platonists and Aristotelians. Several hundred years after their deaths, though, there began a more conscious revival of their thinking. The most important figure in this evolution of ancient philosophy was Plotinus (ca. AD 204–270). Plotinus lived at the beginning of a period we now call “late antiquity,” which continued into the medieval era. In considering Plotinus and other philosophers of late antiquity, we venture beyond the limits of the New Testament. This discussion will help us understand, however, how the languages of the New Testament combined with philosophy to have a powerful effect on later thinkers.

In a series of works called the Enneads, which were compiled by his student Porphyry, Plotinus outlined an original philosophical system based on the metaphysical teachings of Plato.[33] Some of these teachings are already familiar to us: Plato believed that the Forms made up true reality and that they inhabited a world apart from this one. True knowledge was apprehension of the Forms. Accordingly, Plotinus’s system contained three basic parts—the “One” or the “Good,” intellect, and soul. The One is the most fundamental part of all reality and, like the principles of some Presocratics, is the explanation for the other phenomena we observe. The One is not a compound of anything but is simple. It must be simple if we are to use it as a ground to explain everything else, for if it were not simple, we would have to explain its existence in terms of some other thing. The other two principles of Plotinus’s system, the intellect and the soul, are derivations from the One.

Plotinus’s Enneads contain discussions of ethical topics, with chapters titled “On True Happiness,” “On Beauty,” “On Love,” and so on. But with his doctrines on the One, Plotinus is noteworthy for his role in refocusing philosophical questions on metaphysical issues. This new focus, in a sense just a return to the concerns of Plato and Aristotle, would last long into the medieval period (and in some ways continues even today). Nowhere is this more true than in Neoplatonism, the philosophical school founded by Plotinus, in which later stages of Christian theology saw a more conscious evolution in step with philosophical thinking. Below we will explore some of these connections as well.

Neoplatonism

For the intellectual world following the New Testament, the most important strain of thought we have yet to discuss is Neoplatonism. Plotinus is the founder of this school, which carries on Plato’s interest in questions concerning the fundamental nature of reality and our relationship to it. The term Neoplatonism is a modern one, however. Historians use it to designate developments in Platonic thought after the death of Plato and his closest followers in Athens.

We may wonder, though, why understanding Neoplatonism matters for the New Testament. After all, Plotinus lived long after Christ, the apostles, and Paul; his views could not have had any effect on the philosophers who gathered to hear Paul at Mars’ Hill, for example. Yet there are good reasons to discuss Neoplatonism in this context. One is that it is the most important philosophical influence on post-apostolic Christian thought until Thomas Aquinas in the thirteenth century. Another reason is that Neoplatonism was also a major player in the larger world in which the New Testament, as we know the text today, was shaped. Knowing a little about the philosophical language of those who shaped it will prepare us to explore many important issues, such as the role of philosophy and theology in determining why the New Testament exists in its current form.

Using the ideas of Plato as a base, Neoplatonist philosophers undertook to rationalize many ancient doctrines and produce perhaps the widest-ranging and deepest system of thought then developed. We should also note that the two main views rejected by Neoplatonism were Epicureanism and Stoicism. Neoplatonic thinking had a decidedly mystical slant; this mysticism deemphasized the importance of the body and empirical reality in general, which did not fit well with the materialism of the two most important Hellenistic movements. More fundamental than body was mind—that is, νοῦς (nous, “intellect”). The cause of intellect traces back to the One. Like Platonism, Neoplatonism is not an idealist philosophy, idealism being the theory that ideas or mental reality are the only things that exist. For Neoplatonists, matter exists and derives its existence from an emanation of the One. For some Neoplatonist thinkers, matter was also related to the existence of evil. This view stands in contrast to other strands of Neoplatonism in which moral depravity is not due to passive matter but instead is possible in the human soul itself.

Following Plotinus we find multiple developing branches of Neoplatonism. Plotinus’s student Porphyry (AD 234–305) gathered Plotinus’s writings into the Enneads, and he also wrote original works in some areas of natural philosophy. One piece worth noting here is Κατὰ Χριστιανῶν (kata christianōn), or Against the Christians.[34] By Porphyry’s time, the Christian religion was already spreading widely and there were many new converts and established believers throughout the Roman Empire. Against the Christians assailed the burgeoning movement on all fronts, from ad hominem attacks against Christ and the apostles to philosophical critiques of the nature of God and the Resurrection. Fellow second-generation Neoplatonist Iamblichus (AD 245–325) took a different course, writing mostly on mathematics.[35]

Porphyry’s polemic illustrates one side of a broader development in early Neoplatonism. On the one hand, Porphyry and others used philosophy to criticize Christian doctrine as well as the habits and customs of the believers. But other Neoplatonists were beginning to concern themselves more with reconciling the two systems. The appeal of Neoplatonism to an interested Christian thinker would have been obvious. The similarity between the One of Neoplatonic metaphysics and the Christian God spoken of in the Bible is readily apparent; once that connection is made, the believer gains access to many other useful philosophical resources, including some dealing with the mind, the soul, and their relation to God. Neoplatonism also emphasizes spiritual or mental reality over and above bodily reality, which in some ways coheres with the New Testament’s emphasis on what lies beyond this earth. In fact, unlike Epicureanism and other Hellenistic views, Neoplatonism already had all the pieces in place to unite with many theological ideas in early Christianity. It would not be long after Paul’s death before Christians had turned a full 180 degrees in their attitude toward Greek philosophy.

As a living philosophical movement, Neoplatonism lasted well into the medieval period. Like Epicureanism, it even played a role in seventeenth-century philosophy, this time among the so-called “Cambridge Platonists.” More importantly for our purposes, it influenced some of the earliest Christian philosophers, a few of whom we will meet briefly in the final section.

Conclusion

Christianity continued to develop in step with philosophy. Neoplatonism emerged with the work of Plotinus in the third century AD, following a group of Christian philosophers and theologians known now as the “church fathers.” These figures, such as Irenaeus (second century AD), Clement of Alexandria (AD 150–215), Tertullian (AD 155–240), and Origen (AD 184–253), contributed to an enormous body of theological literature written in both Greek and Latin. Others played an equally fundamental—and generally more orthodox—role in the development of Christian theology, like Ambrose (AD 340–397), Jerome (AD 347–420), and Augustine of Hippo (AD 354–430). Augustine in particular had wide philosophical influence that extends far beyond Christianity. Although the church fathers agree among themselves on certain issues within Christian theology, there is still great variation among their views. Though they are not part of the Greco-Roman background of the New Testament proper, they still belong both to the background that many readers bring to the text and to the history of New Testament interpretation that has developed around them.

In this chapter we have discussed the philosophical language of the New Testament world. This language has many dialects: from its beginnings in the Presocratics and its flowering in ancient Greece to the Hellenistic philosophers and their intellectual heirs, a few long-running philosophical movements had an outsized impact on the New Testament. The most important of these are Epicureanism and Stoicism, which Paul encountered directly and which run as an undercurrent beneath many scriptural passages.

Given the influence of Greek and Roman thinking in the early communities of Christianity, it may be surprising that we do not see even more explicitly philosophical material in Paul’s letters or the Gospels. We have seen how Paul warily treats some of these issues, worrying always that the influence of worldly wisdom will spill over into the minds and hearts of the faithful. What might he have thought when later theological developments began to fold many ideas of Greek and Roman thinking into Christianity itself? The legacy of the church fathers and other thinkers witnesses the checkered history of the interaction between Christian doctrine and philosophy—an interaction that began within the philosophical milieu of the Roman Empire and continues today.

Though not often articulated or appreciated, Latter-day Saint thought encompasses many interesting and important philosophical positions in dialogue with both the scriptures and other movements in Christian thought. The more we understand the language of these positions and how they relate to each other, the more we can value and live the beautiful system of thought given fullest expression in Joseph Smith and his successors.

Notes

[1] Western philosophy is not the only philosophical movement of this time; both Chinese philosophy and Buddhism can claim ancient origins. For an accessible exploration of these topics, see Bryan W. Van Norden, Introduction to Classical Chinese Philosophy (Indianapolis: Hackett, 2011).

[2] For Presocratic primary sources in English and Greek, see Daniel W. Graham, ed., The Texts of Early Greek Philosophy: The Complete Fragments and Selected Testimonies of the Major Presocratics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010); and S. Marc Cohen, Patricia Curd, and C. D. C. Reeve, eds., Readings in Ancient Greek Philosophy from Thales to Aristotle (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1995). References to Presocratic philosophers are made with Diels-Kranz numbers (see tinyurl.com/

[3] Graham, Texts of Early Greek Philosophy, 29.

[4] See Graham, Texts of Early Greek Philosophy.

[5] For Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, as well as most other figures discussed in this chapter, more comprehensive introductions to their lives and thought are found in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy (iep.utm.edu) and Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (plato.stanford.edu).

[6] Plato, Apology 30e.

[7] This is called the “Socratic problem.” See tinyurl.com/

[8] For Plato’s primary sources in English, see John M. Cooper, ed., Plato: Complete Works (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1997); quotations in this chapter are from this edition. Greek editions can also be found in the Oxford Classical Texts series as well as in the Loeb Classical Library (loebclassics.com). Greek and English versions of many of Plato’s works are available for free online at the Perseus Project (perseus.tufts.edu). References to Plato’s works are made with Stephanus numbers (tinyurl.com/

[9] Plato, Republic 514a–520a.

[10] For Aristotle’s primary sources in English, see Jonathan Barnes, ed., The Complete Works of Aristotle: The Revised Oxford Translation (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984). The standard Greek editions of his work are part of the Oxford Classical Texts series; see also the Loeb Classical Library (loebclassics.com). As with Plato, the Perseus Project (perseus.tufts.edu) hosts free versions of Aristotle’s work in both Greek and English. References to Aristotle’s works are made with Bekker numbers (tinyurl.com/

[11] Alfred North Whitehead, an early-twentieth century philosopher and mathematician, wrote that “the safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato.” Process and Reality, ed. David Ray Griffin and Donald W. Sherburne( London: Free Press, 1978).

[12] More precisely, the Hellenistic age begins with the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and ends with the Roman victory at Egypt in 30 BC.

[13] Unlike the works of the more prominent philosophers like Plato and Aristotle, most of the original writings of the Cynic philosophers are now lost. We know about them through the descriptions of other writers. For a discussion of the available sources and translations of many important Cynic texts, see Robert Dobbin, The Cynic Philosophers: From Diogenes to Julian (London: Penguin, 2012).

[14] Both stories are reported in Diogenes Laërtius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers (see next note).

[15] Other important philosophical systems of this period are the Skeptics (also called Pyrrhonism), the Cyrenaics, and the Hellenistic Judaism of Philo of Alexandria. As with the Cynics, we do not possess many original sources from authors in the Hellenistic period. Diogenes Laërtius, who lived several hundred years after Christ, gathered many philosophical doctrines and stories in his Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Both the Greek text and an English translation of Lives are available online as part of the Loeb Classical Library (loebclassics.com). A recent English edition of textual fragments with commentary is A. A. Long and D. N. Sedley, The Hellenistic Philosophers (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987). For Philo, see Charles Duke Yonge, The Works of Philo (Peabody, MA: Hedrickson Publishers, 1995).

[16] Plato, Phaedo 82e.

[17] Plato, Phaedo 63e.

[18] See συλαγωγέω in Frederick William Danker, A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001). This work, sometimes called “BDAG” for the initials of current and former editors, is one of the most authoritative lexicons for New Testament Greek.

[19] See σπερμολόγος in Danker, Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament.

[20] The tenth book of Diogenes Laërtius’s Lives, cited earlier, deals with Epicurus (see tinyurl.com/

[21] The main opposition of empiricism is “rationalism,” or the idea that we have knowledge that is somehow independent of sense experience.

[22] Diogenes Laertius, Lives 10.124.

[23] Diogenes Laertius, Lives 10.123.

[24] For an English translation of De rerum natura, see tinyurl.com/

[25] Paul continues in the same verse: “as certain also of your own poets have said, For we are also his offspring.” Here he quotes from the Stoic poet Aratus (315–240 BC), who wrote a long work called Phenomena.

[26] This view is based on the Greek μὲν . . . δὲ construction in Acts 17:32, along with a parallel to verse 18, where the philosophers are first mentioned. See Jerome H. Neyrey, “Acts 17, Epicureans, and Theodicy: A Study in Stereotypes,” in David L. Balach, Everett Ferguson, and Wayne A. Meeks, eds., Greeks, Romans, and Christians: Essays in Honor of Abraham J. Malherbe (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1990). The possibility has also been suggested by other authors.

[27] See Plutarch, On the Fortune or the Virtue of Alexander (tinyurl.com/

[28] Epictetus, quoted in Long and Sedley, Hellenistic Philosophers, 418.

[29] For primary sources of these authors, see the Loeb Classical Library (loebclassics.com). For collected fragments, see Long and Sedley, Hellenistic Philosophers.

[30] Human beings, consisting of a “heavy” body and a “light” soul—though both are material—have a kind of personal identity during life. Upon death, our still-existent parts return to form part of the whole once again, but we are no longer differentiated by an identity. It may have been the identity-preserving nature of the Resurrection—as opposed to the weaker, impersonal “immortality” of typical Stoicism—that piqued the interest of these philosophers. The last important Stoic philosopher was Marcus Aurelius. By his time, Stoicism had dropped most of its interest in questions about the natural world and was focused exclusively on ethics. The original Stoic division of knowledge into logic, physics, and ethics still existed, but Aurelius’s writings were more personal in nature. His Meditations, sometimes called To Himself, was a series of reflections on his life and duty as an emperor and adherent of Stoic philosophy. See tinyurl.com/

[31] Other passages with possible Greek philosophical influences include Romans 1–2 and 2 Peter 3. For an introduction to these issues along with a discussion of Stoicism in several apocryphal texts, see Tumoas Rasimus, Troels Engberg-Pedersen, and Ismo Dunderberg, eds., Stoicism in Early Christianity (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2010).

[32] See tinyurl.com/

[33] The Enneads are available online in the Loeb Classical Library (loebclassics.com).

[34] Some of this material is online; see tinyurl.com/

[35] For texts and interpretation of Iamblichus, see tinyurl.com/