The Crucifixion

Gaye Strathearn

Gaye Strathearn, "The Crucifixion," in New Testament History, Culture, and Society: A Background to the Texts of the New Testament, ed. Lincoln H. Blumell (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 358-376.

Gaye Strathearn is a professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University.

A number of years ago some members of the Church heard that I was working on a paper about Christ’s crucifixion.[1] They asked me why I was bothering with that topic: Why would I want to spend time studying the Crucifixion? Their questions highlighted for me how little we discuss the cross in classes, except perhaps to note that it took place. This modern situation is a long way from Brigham Young’s direction to the missionaries that if they wanted to be successful on their missions they would need to have their minds “riveted—yes, I may say riveted—on the cross of Christ.”[2] My response to my friends’ questions was that, although we may not often talk much about it, the cross was not just a historical event, it was a central part of Jesus’ atoning sacrifice and is an important doctrine taught in our standard works. I have often thought about that exchange as I have continued to try to understand more fully the implications of the cross for my salvation.

In an effort to more fully understand and appreciate the importance of the cross and its doctrinal implications, I will discuss four aspects of crucifixion. First, I will discuss the literary and material culture evidence for crucifixion in the ancient world. In doing so we will be better placed to understand the descriptions on Jesus’s crucifixion in the Gospel accounts. While many texts mention crucifixion, they generally do not provide detailed descriptions of it. Nevertheless, we will see that most of the elements mentioned in the Gospel accounts of Jesus’s crucifixion are compatible with the nonbiblical texts and material culture. Second, I will discuss some of the medical research into the physical causes for Jesus’s death on the cross. Given the variety of ways that crucifixions were performed in antiquity, the limited ancient sources and the ethical limitations for modern research, it is difficult to do more than hypothesize the causes. Even so, important insight can be gleaned into the physical trauma. Third, I will discuss the doctrine of the cross as taught in both the New Testament and in our Restoration scripture. In doing so, we will see a consistent theme of the importance of the cross in the teachings of Christ’s redemption of humanity. Finally, I will look at just one example of personal application of the doctrine of the cross. Throughout the paper, I will argue that the cross is anything but a marginal footnote—rather it is an integral part of the Savior’s atonement, and is therefore something that deserves our attention and careful study.

Crucifixion in the Ancient World

The Gospel accounts of Jesus’s crucifixion provide relatively few specific details. While there is some level of agreement among the accounts for certain aspects, there are also aspects unique to each Gospel. During his arraignment before Pilate, Jesus was scourged and mocked (Mark 15:15–17, Matthew 27:26–31; John 19:2; see also the Book of Mormon prophecies: 1 Nephi 19:9; 2 Nephi 6:9; Mosiah 3:9). According to John, he then carried his cross to the place of execution (John 19:17), although the Synoptic Gospels record that Simon of Cyrene was conscripted to carry it (Mark 15:21; Matthew 27:32; Luke 23:26). The place of crucifixion was known as the Place of the Skull, variously identified by the Aramaic “Golgotha” (Mark 15:22; Matthew 27:33; John 19:17) or the Latin “Calvary” (Luke 23:33), which John places “nigh to the city” (19:20).

The Gospels are united in recording that Jesus was crucified along with two others (Mark 15:27; Matthew 27:38; Luke 23:33; John 19:18). None of the Gospel accounts of the Crucifixion make explicit mention of how he was attached to the cross, although Thomas’ declaration in John 20:25 insists on seeing and touching “the print of the nails” in the hands of the resurrected Jesus.[3] All of the accounts, however, do note the derision of people who were watching the Crucifixion (Luke 23:35–37) or were passing by (Mark 15:29–32; Matthew 27:39–43).[4] They all record that Jesus was able to speak while he was on the cross (Mark 15:34, 37; Matthew 27:46, 50; Luke 23:43, 46; John 19:26–28, 30). Only John records that the Jews came to Pilate asking him to break the victims’ legs so that their bodies would not remain on the cross during the Sabbath, although he notes that when the soldiers came to Jesus he was already dead, and that one of them pierced Jesus’ side with a spear (John 19:31–34). All four Gospels record that Joseph of Arimathea asked Pilate for Jesus’s body so that he could bury him (Mark 15:43–45; Matthew 27:57–59; Luke 23:50–53; John 19:38), but John alone identifies Nicodemus as the one who brought spices to prepare the body for burial (John 19:39–40). Only Matthew records that guards were posted at the tomb (27:62–66).

While scholars debate many of the specific details about Jesus’ life and ministry, the historicity of his crucifixion is not in question. The writings of both Jewish and Roman historians, Josephus (37–ca. AD 100) and Tacitus (ca. AD 56–120) confirm the Gospels’ record that Jesus was crucified by Pilate.[5] As brief as the Gospels’ details are, their combined accounts provide one of the most detailed accounts of any ancient crucifixion. Ancient sources frequently mention crucifixions taking place, but they rarely give extended details. Nevertheless, they can help readers of the New Testament better understand the nuances of Jesus’s crucifixion.

Crucifixion has been defined as “execution by suspension,” although generally it does not include “impalement or hanging.”[6] The Persians seem to have invented the practice,[7] but many ancient groups, including the Romans and Jews, carried it out as a form of capital punishment.[8] Even though Christians generally have a set idea of what ancient crucifixion looked like, the term covered a wide range of practices. Seneca, a Roman philosopher (4 BC–AD 65) wrote, “Yonder I see crosses, not indeed a single kind, but differently contrived by different peoples.”[9] Sometimes the suspension took place on a tree,[10] a pole,[11] or on a variety of cross types, either crux commissa, which is in the form of a “T” (e.g., the Puteoli and Paletine crucifixion graffiti)[12] or the crux immissa, also known as the “Latin cross,” which has “the crossbar below the top of the stave but above the middle”[13]: ✝ (the usual form used in Christian art). Usually victims were crucified while alive, but sometimes it was after they were dead.[14] Sometimes the victim was even crucified upside down.[15] We know that at least in some places the practice of crucifixion was closely regulated.[16]

In Roman times, this form of punishment was used for a variety of crimes, including arson, desertion, disobedience, piracy, theft, or murder.[17] But Josephus emphasizes that in Roman Judea the most frequent reason for crucifixion was political rebellion.[18] For example, in 4 BC the governor of Syria, Quintilius Varus, crucified 2,000 Jews because they incited a rebellion after the death of Herod the Great.[19] On another occasion, he documents that Marcus Antonius Felix, the Roman procurator of Judea (AD 52–58), crucified a limitless number of brigands who had followed Eleazar in his rebellion against Rome.[20]

Although much of our artwork of Jesus’s crucifixion portrays a fairly sanitized version of crucifixion, the cruelty of it was well known in the ancient world. Josephus describes it as a “most miserable death,” a fact that is born out in the literature.[21] Seneca describes the suffering this way:

Tell me, is Death so wretched as that? He asks for the climax of suffering; and what does he gain thereby? Merely the boon of a longer existence. But what sort of life is lingering death? Can anyone be found who would prefer wasting away in pain, dying limb by limb, or letting out his life drop by drop, rather than expiring once for all? Can any man be found willing to be fastened to the accursed tree, long sickly, already deformed, swelling with ugly tumours on chest and shoulders, and draw the breath of life amid long-drawn-out agony? I think he would have many excuses for dying even before mounting the cross![22]

We have a few accounts of individuals who survived the ordeal because they were taken down from the cross before death.[23] Its popularity as a form of capital punishment was fostered by the fact that the torture could be extended for long periods of time, it was humiliating, and its public nature served as a deterrent for others. One text attributed to a Roman rhetorician from Hispania named Quintilian (ca. 35–ca. 100 AD) says, “When we crucify criminals the most frequented roads are chosen, where the greatest number of people can look and be seized by fear.”[24] This description corresponds with John’s account that Jesus was crucified “nigh to the city” (19:20). The fact that there were passersby probably indicates that the site was close to a road of some kind.

Generally Roman citizens, especially the upper classes, were spared from enduring crucifixion. In fact, Cicero, an influential Roman orator and politician (106–43 BC), argues that not only should they not be subject to it but that it should be kept even from their “thought, eyes, and ears.”[25] There were, however, some exceptions although they were strongly denounced by Cicero and the Roman historian Suetonius (ca. AD 69–after 122).[26] At the other end of the spectrum, however, slaves (both men and women), criminals, and foreigners were frequently put to death on a cross. It was so frequent that the phrase “in (malam) crucem ire,” which can be translated literally as “go to an (evil) cross,” became a slang expression for telling someone to “go to hell.”[27] One gets a sense of the inevitability slaves must have felt about crucifixion from one’s declaration in a play by the Roman playwrite, Plautus (ca. 254–184 BC): “I know that the cross will be my tomb; there my ancestors have been laid to rest, my father, grandfather, great-grandfather, great-great-grandfather.”[28]

By Roman times, some form of torture usually preceded crucifixion. These tortures most frequently included scourging,[29] but other techniques such as “fire and sword”[30] and “fire and hot metal plates”[31] are also noted in the descriptions.

John’s account of Jesus carrying his own cross finds a parallel in the writings of a Greek biographer named Plutarch (AD 46–120). He records that “every criminal who goes to execution must carry his own cross on his back.”[32] Scholars now believe that the term “cross” here is a reference to only part of the cross—the patibulum, or the horizontal part of the cross, on which their arms were extended. The vertical pole, in these cases, would have already been in place at the site of execution.[33] Other texts suggest that Plutarch may have overstated the fact when he said that everyone had to carry their cross. For example, the lex Puteolana (“laws of Puteoli”), which regulates how crucifixions were to be carried out, suggests that carrying the patibulum was optional—to be decided by the contractor in charge of the crucifixion: “If [the contractor] wants [the condemned slave] to bring the patibulum to the cross, the contractor will have to provide the wooden posts, chains, and cords for the floggers and floggers themselves” (ll. 8–9; emphasis added).[34] The floggers were used to goad the victim carrying the patibulum to continue moving to the place of execution. This was part of the torture and humiliation associated with crucifixion.

Once the victim arrived on site he or she was attached to the cross. In many of the literary accounts of crucifixion, the descriptions are often ambiguous about how this took place. Frequently they use language describing the victim as being “raised on a cross,” being “lifted up” on a cross, or being “fixed” to the cross, but without giving specific details of how it took place. Some were clearly bound by ropes or, as the Pereire gem shows, with fetters.[35] In other cases, both nails and ropes were used.[36] But in some it is clear that they were attached with nails. Josephus describes two crucifixions where he specifically says that they were nailed to the cross. He records how Florus, the procurator of Judea from AD 64–66, crucified Romans of equestrian order, who were Jews by birth: he “whipped, and nailed (Greek prosēloō) [them] to the cross before his tribunal.”[37] Likewise, in his description of Titus’s siege of Jerusalem, he describes the soldiers capturing Jews who were trying to escape the siege: “So the soldiers out of the wrath and hatred they bore the Jews, nailed (Greek prosēloō) those they caught. . . to the crosses.”[38]

Right anklebone with nail. Jehoḥanan crucifixion.

Right anklebone with nail. Jehoḥanan crucifixion.

Courtesy of Kent P. Jackson.

The only archaeological evidence we have for someone crucified in the first century is the remains of an individual named Jehoḥanan ben Ḥagqol whose bones were found in an ossuary at Giv’at ha Mivtar in Jerusalem in 1968. We know that he was crucified because the nail was still in his right calcaneum (i.e., heel bone). When the nail was originally inserted it must have hit a knot of wood because the tip of the nail is bent, and thus could not be removed. The position of the nail indicates that Jehohanan’s feet were nailed on either side of the upright beam of the cross,[39] a position also indicated in the Puteoli crucifixion graffito of Alkimilla.[40] There was no evidence in the case of the Jehoḥanan remains that the bones of the arms or hands were nailed to the cross, so he may have been tied to the patibulum.[41] Therefore, Thomas’s plea to “see in his hands the print of the nails, and put my finger into the print of the nails” of the resurrected Jesus (John 20:25) is consistent with what we know about crucifixion from the literary and material culture of the period.

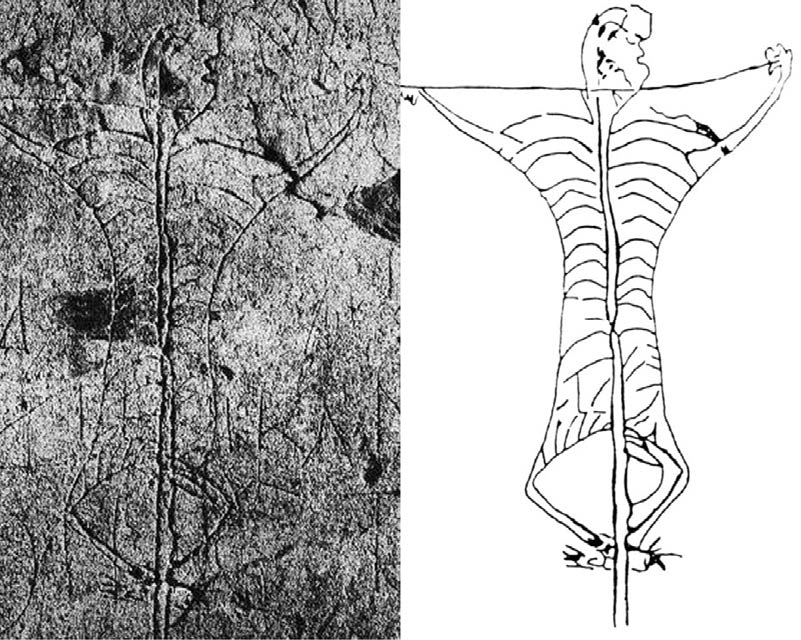

Puteoli graffito. The Crucified Alkimilla. Trajanic-Hadrianic

Puteoli graffito. The Crucified Alkimilla. Trajanic-Hadrianic

era. Puteoli: Via Pergolesi 146, Taberna 5. West Wall. Drawing by Professor Antonio Lombatti.

Courtesy of Antonio Lombatti.

Early Christian apologists Irenaeus and Tertullian both mention there was a seat (sedile) on the cross for Jesus’s crucifixion, although that detail is not mentioned in the Gospel accounts.[42] Both the Puteoli and Palatine graffitos appear to include a sedile in their depictions of crosses.[43] These seats were not meant to relieve but to exacerbate the suffering of the victim.

In some cases, in an effort to heighten the shame of the punishment, the victim was crucified nude. The woman Alkimilla, for example, in the Puteoli crucifixion graffito is not clothed and Artemidorus Daldianus, a second-century AD diviner from Ephesus, writes, “They are crucified naked (Greek gymnoi) and the crucified lose their flesh.”[44] But the evidence is ambiguous because although the Greek word gymnos is generally translated as naked, it can also be used to describe those who are “lightly clad, without an outer garment.”[45] The Palatine graffito shows the victim wearing a short tunic. At least some early Christians believed that Jesus was crucified naked. In the second century AD, the bishop of Sardis named Melito (died ca. 180) lamented Jesus’s crucifixion: “O frightful murder! O unheard of injustice! The Lord is disfigured and he is not deemed worthy of a cloak for his naked body, so that he might not be seen exposed. For this reason the stars turned and fled, and the day grew quite dark, in order to hide the naked person hanging on the tree, darkening not the body of the Lord, but the eyes of men.”[46] Melito’s lament is supported by the Pereire gem depicting Jesus naked on the cross. However, possibly in an attempt to preserve Jesus’s modesty, the Acts of Pilate, a fourth-century text, states, “And Jesus went out from the praetorium, and the two malefactors with him. And when they came to the place, they stripped him and girded him with a linen cloth and put a crown of thorns on his head.”[47]

Both Deuteronomy 21:22–23 and the Temple Scroll from the Dead Sea Scrolls (11Q19 64.11–13) demand that those who “hang on a tree” should not be left there overnight. The body must be buried that day. Of course, this was not the normal practice with crucifixion. Its purpose was to extend the suffering for as long as possible. Once the victim had died, the bodies were usually left on the cross where their flesh was eaten by birds and wild animals[48] as a deterrent to all who saw them. Hence the slave’s lament, mentioned above, that the cross would be his tomb, as it had been for his ancestors.[49]

All four Gospel accounts mention that Joseph of Arimathea came to Pilate and gained permission to take Jesus’s body and bury it. By Roman times, this practice was permitted in some cases once death had been verified:

The bodies of those who suffer capital punishment are not to be refused to their relatives; and the deified Augustus writes in the tenth book of his de Vita Sua that he also had observed this [custom]. Today, however, the bodies of those who are executed are not buried otherwise than if this had been sought and granted. But sometimes it is not allowed, particularly [with the bodies] of those condemned for treason. . . . The bodies of executed persons are to be granted to any who seek them for burial.[50]

Philo, a Jewish philosopher living in Alexandria (20 BC–ca. AD 50), knew of men who had been crucified and were taken down from the cross and given to their families for burial prior to the Emperor’s birthday celebration.[51]

If, however, the person on the cross had not died before the end of the day, in order to comply with the mandate of Deuteronomy 21, other strategies were needed. John says that the soldier broke the legs of the other victims but did not need to do so to Jesus because he was already dead (19:31–33). That the Romans broke people’s legs as a form of severe punishment is well attested,[52] but there is little evidence to suggest that it was associated with crucifixion—probably because crucifixion was not meant to be sped up.[53] There is, however, some support for John’s description of the soldier piercing Jesus’s side with a spear (19:34). Quintilian writes, “Crosses are cut down, the executioner does not prevent those who have been pierced from being buried.”[54]

Many features included in the Gospels’ accounts of Jesus’ crucifixion are compatible with what we know about crucifixions from the literary and material culture of the ancient world. Although we may never know the full extent of Jesus’s sufferings on the cross, these accounts more fully deepen our understanding of the sacrifice Jesus made for us. We will now turn our attention to trying to understand what it was about crucifixion that led to Jesus’s death on the cross.

Cause of Death during Crucifixion

Modern researchers have tried to explain the physical causes for Christ’s death on the cross. The process of discovery is made difficult by a number of factors: (1) crucifixion was performed in different ways, and these different methods may have influenced the pathophysiology leading to death; (2) we have only two types of sources from which to understand the effects of crucifixion: one archaeological discovery and literary texts, which provide only limited clues regarding the physiological effects of crucifixion; and (3) it is impossible to ethically recreate the process of crucifixion in order to study its physiological effects, although there are accounts of crucifixion from modern times.[55] One study attempted to humanely reconstruct crucifixion postures to study its effects on limited aspects of physiology, such as respiratory functioning, oxygen saturation and blood pressure.[56] While this study resulted in serious questions about the role of asphyxiation as a cause of death, such attempts “cannot be considered directly comparable to crucifixion.”[57]

Current thoughts suggest that a combination of medical factors, such as shock and trauma-induced coagulopathy, ultimately led to Christ’s death on the cross. First, hypovolemic shock may have resulted from blood loss, dehydration and tissue trauma. The scriptures record that during the physical and spiritual anguish that transpired in Gethsemane, Christ bled “at every pore” (Doctrine and Covenants 19:18; see also Luke 22:44) and that before his crucifixion he was subsequently beaten repeatedly and scourged. Profuse sweating and deprivation of fluids may also have contributed to his dehydration, as evidenced by the Savior crying out in thirst (John 19:28). Decreased blood perfusion to the bodily tissues may have resulted in a cascade of biochemical events further compromising organ functioning, including blood acidosis, and a systemic inflammatory response. These changes associated with traumatic shock can lead to death within several hours. Trauma-induced coagulopathy, resulting in a blood-clotting deficit and bleeding diathesis, is an additional complication that could have further accelerated death.[58] Other medical hypotheses have included heart failure, syncope, asphyxia, arrhythmia plus asphyxia, and pulmonary embolism, any of which could have been present together, with none being the sole cause of death.[59]

With this overview of ancient crucifixion practices in relation to the Gospel accounts, and a brief summary of medical hypotheses about the possible causes of death with crucifixion, we are now in a place to understand the doctrinal aspects of crucifixion in our scriptural texts.

The Doctrine of the Cross

Jesus’ teachings about the cross and discipleship

During his mortal ministry, Jesus frequently used the invitation to take up one’s cross as a symbol for an invitation to discipleship (Matthew 10:38, 16:34; Mark 8:34, 10:21; Luke 9:23, 14:27). Just after Jesus had promised Peter that he would give to him the sealing keys, Jesus began to speak openly about his destiny to go to Jerusalem, where he would “suffer many things of the elders and chief priests and scribes, and be killed, and be raised again the third day” (Matthew 16:21; see also Mark 8:31; Luke 9:22). Peter immediately tried to assure his Master that this would not happen, to which Jesus responded by saying, “Get thee behind me, Satan: thou art an offence unto me: for thou savourest not the things that be of God, but those that be of men. Then said Jesus unto his disciples, If any man will come after me, let him deny himself, and take up his cross, and follow me” (Matthew 16:23–24). Luke, who uses a slightly different form of the verb (arneomai), adds, “Let him deny himself, and take up his cross daily, and follow me” (Luke 9:23; emphasis added). What does it mean to “take up our cross”?

In this context, it means that disciples must deny themselves. Both Matthew and Mark use the Greek word aparneomai, suggesting that discipleship entails the breaking of every link that ties people, even to themselves. It is about being able, like Jesus, to submit our will to the will of the Father (see Mosiah 15:7; Luke 22:42). Everyone who heard Jesus compare discipleship to the cross would have understood the impact of his teaching because of their familiarity with what crucifixion cost. His teachings were more than the abstract metaphor they are to modern readers because crucifixion was a very real part of their lives.

Becoming a disciple meant giving up everything—even our will—to follow Jesus. As Elder Neal A. Maxwell taught, our will is “really the only uniquely personal thing we have to place on God’s altar.”[60] Just as there was a cost for Jesus on Calvary, there is also a cost to be a disciple. In fact, in other settings, Jesus also taught, “And he that taketh not his cross, and followeth after me, is not worthy of me” (Matthew 10:38; emphasis added), and even more pointedly, “Whosoever doth not bear his cross, and come after me, cannot be my disciple” (Luke 14:27; emphasis added).

Such teachings must have become even more poignant to the earliest Christians as they watched their master arrested, scourged, humiliated and crucified. How would they explain the paradox of their God being crucified? How would they transform “the offence [Greek skandalon] of the cross” (Galatians 5:11) into the doctrine of the cross that emphasized the symbol of God’s transformative power? For this, in the New Testament, we are indebted to the teachings of Paul.

Paul’s response to “the offence of the cross”

The accounts of Jesus’s crucifixion in the four Gospels focus on the events of the trial and the subsequent crucifixion, with no attempt to discuss the significance of those events. In other words, the crucifixion accounts are generally more interested in the historical events than they are with the doctrinal implications. In Acts, the Crucifixion is at the heart of the teachings of Peter and John (Acts 2:23, 36; 4:10). Likewise, Paul reminds the Corinthians that he “determined not to know any thing among you, save Jesus Christ and him crucified” (1 Corinthians 2:2).

It is clear that the Christian message that Jesus, as Son of God, was crucified, was troubling to both Jews and Gentiles. In his letter to the Galatians, Paul acknowledged that under the law of Moses, “cursed is every one that hangeth on a tree” (Galatians 3:13; see also Deuteronomy 21:22–23).[61] We also know that some people mocked Christians for worshipping a God who was crucified. One example is the second-century Cynic philosopher Lucian, who once lived among Christians in the land of Israel. He later wrote a satire that mocked Christians who “have sinned by denying the Greek gods, and by worshipping that crucified sophist himself and living according to his laws.” Further, Jesus was a man “whom they still worship—the man who was crucified in Palestine for introducing this new cult to the world.”[62] In the literature, we also see Christians and pagans in dialogue over the value of the crucifixion. In the second century, Justin Martyr, a Christian apologist, acknowledged the charges: “It is for this that they charge us with madness, saying that we give the second place after the unchanging and ever-existing God and begetter of all things to a crucified man.”[63] In the second or third century, Minucius Felix’s Octavius tells of a pagan retort against Christians: “To say that a malefactor put to death for his crimes, and wood of the death-dealing cross, are objects of their veneration is to assign fitting altars to abandoned wretches and the kind of worship they deserve.”[64] A graphic representation of the disdain that pagans had for the Christian worship of a crucified god is a graffito carved into plaster on a wall near the Palatine Hill in Rome that is probably dated from the second or third century.[65] It depicts a boy at the foot of a crucified man that has the head of a donkey. The crude inscription reads, “Alexamenos worships [his] God.”[66]

![Palatine graffito and drawing of the same. The inscription reads “Alexamenos worships [his] God.”](/sites/default/files/pub_content/image/5687/NT_History_3-11-19_Page_379_Image_0001.jpg) Palatine graffito and drawing of the same. The inscription

Palatine graffito and drawing of the same. The inscription

reads “Alexamenos worships [his] God.”

![Palatine graffito and drawing of the same. The inscription reads “Alexamenos worships [his] God.”](/sites/default/files/pub_content/image/5687/NT_History_3-11-19_Page_379_Image_0002.jpg)

It is probably this type of criticism of Christianity, what Paul calls “the offence of the cross,” that he responds to as he emphasizes its importance. He acknowledges this type of taunt when he declares, “For the preaching of the cross is to them that perish foolishness; but unto us which are saved it is the power of God. . . . For the Jews require a sign, and the Greeks seek after wisdom: but we preach Christ crucified, unto the Jews a stumblingblock [Greek skandalon], and unto the Greeks foolishness” (1 Corinthians 1:18, 22–23).[67] In this passage, Paul reconfigures the traditional understanding of crucifixion from a symbol of shame into a symbol of the transformative power of God. He understands this power as the power to redeem the sinner and to transform them from the “old man” (Romans 6:6) into a new creature. President Joseph F. Smith describes this process as becoming “soldiers of the Cross.”[68] Thus Christ’s crucifixion became the symbol of what must happen to all. Speaking of his own spiritual transformation, Paul taught the Galatians, “I am crucified with Christ: nevertheless I live; yet not I, but Christ liveth in me: and the life which I now live in the flesh I live by the faith of the Son of God, who loved me, and gave himself for me” (Galatians 2:20). He therefore glories in the cross: “But God forbid that I should glory, save in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ, by whom the world is crucified unto me, and I unto the world” (Galatians 6:14). Being crucified with Christ enables “that the body of sin might be destroyed, that henceforth we should not serve sin” (Romans 6:6). With that destruction of the body of sin through the cross, God is able to bring unity to the Church that is otherwise rife with enmity (Ephesians 2:16).

It is therefore not surprising that Paul weaves the cross throughout the fabric of his teaching. In 1 Corinthians he identifies two particular doctrines that are inseparably tied to the cross. In both cases he uses technical language for “the transmission of religious instruction”: he delivered unto the Saints what he had received of the Lord.[69] The first of the doctrines tied to the cross is that when the saints gather to partake of the Lord’s Supper they are in effect “proclaiming [Greek katangellō] the Lord’s death till he come” (1 Corinthians 11:26). In other words, individually and collectively they are standing as witnesses to proclaim their involvement in appropriating “the cross both for redemption and lifestyle as those who share Christ’s death in order to share Christ’s life.”[70]

The second place where Paul weaves the cross into the doctrine that he received and delivered to the Saints is with the Resurrection. “For I delivered unto you the most important things [Greek en prōtois] which I also received, how that Christ died for our sins according to the scriptures; and that he was buried, and that he rose again the third day according to the scriptures” (1 Corinthians 15:3–4). The most important things that Paul taught to the Corinthians were (1) the Crucifixion and (2) the Resurrection. Paul here chooses to use the Crucifixion as the symbol for Jesus’s atoning sacrifice. For Paul and the early Christians, the cross was inseparably tied to the Resurrection (e.g., Romans 6:3–6; Galatians 2:20). Paul proclaims that he was willing to sacrifice everything that was once important to him “that I might know [Christ] and the power of the resurrection” and that to do this he would need to be “made conformable unto [Christ’s] death [i.e., to be like Christ in his death; Greek summorphizō]” (Philippians 3:10). Without the events on the cross, there would have been no Resurrection, and without the Resurrection “then is our preaching vain, and your faith is also vain” (1 Corinthians 15:14). In other words, the Resurrection gave meaning to the cross, and the cross gave meaning to the Resurrection. They were two sides of the same coin. In the ancient Mediterranean, this combination of the cross and the Resurrection was something unique to Christianity: it transformed the fear and shame of crucifixion into a powerful doctrine and symbol of God’s power to overcome the spiritual vicissitudes of life.

The doctrine of the cross in the Restoration

A Newsweek article once claimed that “Mormons do not . . . place much emphasis on Easter,”[71] meaning that we do not place much emphasis on celebrating Good Friday and the Crucifixion.[72] Our practice of emphasizing our distinctive teachings of Christ’s suffering in Gethsemane seem to have begun when Elder Joseph Fielding Smith taught:

It is impossible for us to comprehend the extent of his suffering when he carried the burden of the sins of the whole world, a punishment so severe that we are informed that blood came from the pores of his body, and this was before he was taken to the cross. The punishment of physical pain coming from the nails driven in his hands and feet, was not the greatest of his suffering, excruciating as that surely was. The greater suffering was the spiritual and mental anguish coming from the load of our transgressions which he carried.[73]

Later Elder Smith remarked, “It was in the Garden of Gethsemane that the blood oozed from the pores of his body. . . . That was not when he was on the cross; that was in the garden.”[74] My point is not to devalue in any way the pivotal part that Gethsemane rightly plays in our theology. My intent is only to remind us that just as the early Christians understood the doctrine of the cross as being inseparably connected with the Resurrection, so our Restoration scripture teaches that it was also inseparably connected with Jesus’s atoning and redeeming sacrifice.

Both the Book of Mormon and the Doctrine and Covenants repeatedly refer to Jesus’s “sufferings and death” in association with their teachings on his atonement and redemption. In the Book of Mormon, this phrase is at the very heart of some important sermons. For example, when Alma the Younger was secretly preaching the words of Abinadi, he combined Jesus’s sufferings, death, and resurrection in his discussion of the redemption of the people: “Yea, concerning that which was to come, and also concerning the resurrection of the dead, and the redemption of the people, which was to be brought to pass through the power, and sufferings, and death of Christ, and his resurrection and ascension into heaven” (Mosiah 18:2; emphasis added). When Aaron, the son of Mosiah, preached to the Amalekites in the city of Jerusalem, we read, “Now Aaron began to open the scriptures unto them concerning the coming of Christ, and also concerning the resurrection of the dead, and that there could be no redemption for mankind save it were through the death and sufferings of Christ, and the atonement of his blood” (Alma 21:9). Likewise, when he preached to King Lamoni’s father, Aaron declared, “And since man had fallen he could not merit anything of himself; but the sufferings and death of Christ atone for their sins” (Alma 22:14; emphasis added). Finally, when Mormon wrote to his son Moroni, he implored that Christ’s “sufferings and death . . . rest in your mind forever” (Moroni 9:25). In the Doctrine and Covenants, Jesus uses this phrase as he advocates with the Father on our behalf: “Father, behold the sufferings and death of him who did no sin, in whom thou wast well pleased; behold the blood of thy Son which was shed, the blood of him whom thou gavest that thyself might be glorified; wherefore Father, spare these my brethren that believe on my name, that they may come unto me and have everlasting life” (Doctrine and Covenants 45:4–5).

In addition to these passages that tightly connect Jesus’s death with his sufferings, the Book of Mormon and Doctrine and Covenants on occasion use the cross as the symbol of Jesus’s atonement. In Nephi’s vision of the tree of life, he learns that the tree represents the love of God (1 Nephi 11:21–22). He then is shown some of the evidences of that love as he sees vignettes of Jesus’s birth and mortal ministry. As part of that revelatory experience, Nephi “looked and beheld the Lamb of God, that he was taken by the people; yea, the Son of the everlasting God was judged of the world; and I saw and bear record. And I, Nephi saw that he was lifted upon the cross and slain for the sins of the world” (1 Nephi 11:32–33; emphasis added). The evidence of God’s love for his children is that his Son was crucified for the sins of the world, a teaching remarkably similar to Jesus’s teaching to Nicodemus: “And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, even so must the Son of man be lifted up: that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have eternal life. For God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life. For God sent not his Son into the world to condemn the world; but that the world through him might be saved” (John 3:14–17). Thus, both the Bible and the Book of Mormon reinforce the central place of the cross as a symbol both of God’s love and of Jesus’s atoning sacrifice.

On day two of Jesus’s visit to the Americas, he responded to a question from his disciples, “Tell us the name whereby we shall call this church” (3 Nephi 27:3). Jesus responded with two qualifications for the Church: it must bear his name, and it must be “built upon [his] gospel” (verses 5–10). Then he gave a definition of his gospel that included the following teaching about the cross: “And my Father sent me that I might be lifted up upon the cross; and after that I had been lifted up upon the cross, that I might draw all men unto me, that as I have been lifted up by men even so should men be lifted up by the Father, to stand before me, to be judged of their works, whether they be good or whether they be evil—and for this cause have I been lifted up; therefore, according to the power of the Father I will draw all men unto me, that they may be judged according to their works” (3 Nephi 27:14–15).

What is important for our discussion is that when Jesus himself described his gospel and the Atonement, he described it in terms of the cross: “My Father sent me that I might be lifted up upon the cross” (verse 14). Notice the purpose of him being lifted up on the cross: so that he could draw all men unto him to be judged.[75] The rest of his definition of the gospel then outlines what people must do to make sure that day of judgment is a day of rejoicing: repent, be baptized in his name, endure to the end, and be sanctified by the Holy Ghost, “that [they] may stand spotless before [him] at the last day” (verse 20). Although in this passage being “lifted up” is associated with judgment, we have already noted that similar language in 1 Nephi 11 and John 3 use the phrase in association with God’s love for his people. Being “lifted up” is also a frequent way to describe salvation (1 Nephi 16:2; Doctrine and Covenants 5:35; 9:14; 17:8).

The Doctrine and Covenants includes one of the most powerful scriptural passages about Jesus’s atoning sacrifice in Gethsemane (Doctrine and Covenants 19:16–19; see also Luke 22:44; Mosiah 3:7), but it also includes verses where redemption is specifically identified with the cross. In sections 53 and 54, Jesus declares to both Sidney Gilbert and Newel Knight that he “was crucified for the sins of the world” (Doctrine and Covenants 53:2; 54:1), and the revelation to President Joseph F. Smith on the redemption of the dead teaches, “And so it was made known among the dead, both small and great, the unrighteous as well as the faithful, that redemption had been wrought through the sacrifice of the Son of God upon the cross” (Doctrine and Covenants 138:35).

All these passages from our Restoration scripture support the biblical message of Paul that Jesus’s crucifixion was an essential part of his Atonement. The doctrine of the cross—that Jesus’s death on Calvary was “for the sins of all men, who in Adam had fallen”[76]— has been taught by the Prophet Joseph Smith and our Restoration scripture.[77] The events on the cross are an essential part of our personal and collective redemption, and so Elder Jeffrey R. Holland has described Easter Friday as “atoning Friday with its cross.”[78]

“The wounded Christ is the Captain of our souls”[79]

As important as this doctrinal understanding of the cross is, there is one more reason why understanding the cross more fully is important for modern Saints. When Jesus first came to the temple in Bountiful, the people were not initially sure who had appeared to them. Even though after the third time they finally understood the words of the Father, “Behold my Beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased, in whom I have glorified my name—hear ye him,” when they saw Jesus descending out of heaven and standing in the midst of them, “they thought it was an angel that had appeared unto them” (3 Nephi 11:7–8). So Jesus declared to them:

Behold, I am Jesus Christ, whom the prophets testified shall come into the world.

And behold, I am the light and life of the world; and I have drunk out of that bitter cup which the Father hath given me, and have glorified the Father in taking upon me the sins of the world, in the which I have suffered the will of the Father in all things from the beginning. . . .

Arise and come forth unto me, that ye may thrust your hands into my side, and also that ye may feel the prints of the nails in my hands and in my feet, that ye may know that I am the God of Israel, and the God of the whole earth, and have been slain for the sins of the world. (3 Nephi 11:10–11, 14)

Here stood the Son of God in a glorified, resurrected body; a body that was perfect in every way, except for the fact that, as prophesied by Zechariah (Zechariah 13:6), Jesus chose to retain the marks of his crucifixion. For the people of 3 Nephi, this retention was one of the tangible proofs that this being was not an angel but was in fact the Savior of the world. And after they each went forth one by one and “thrust their hands into his side, and did feel the prints of the nails in his hands and in his feet. . . . They did cry out with one accord, saying, Hosanna! Blessed be the name of the Most High God! And they did fall down at the feet of Jesus, and did worship him” (3 Nephi 11:15–17). In this instance, the signs of the crucifixion were a reason to rejoice!

Elder Holland suggests one reason why the marks of Jesus’s crucifixion should also cause us to rejoice:

When we stagger or stumble, [they are a reminder that] He is there to steady and strengthen us. In the end He is there to save us, and for all this He gave His life. However dim our days may seem, they have been a lot darker for the Savior of the world. As a reminder of those days, Jesus has chosen, even in a resurrected, otherwise perfect body, to retain for the benefit of His disciples the wounds in His hands and in His feet and in His side—signs, if you will, that painful things happen even to the pure and the perfect; signs, if you will, that pain in this world is not evidence that God doesn’t love you; signs, if you will, that problems pass and happiness can be ours. . . . It is the wounded Christ who is the Captain of our souls, He who yet bears the scars of our forgiveness, the lesions of His love and humility, the torn flesh of obedience and sacrifice. These wounds are the principal way we are to recognize Him when He comes.[80]

Conclusion

Jesus’s crucifixion on the cross is one of the central tenets of Christianity. Before the Battle of the Milvian Bridge (AD 312) when Constantine the Great saw the sign of the cross emblazoned in the sky with the Greek phrase “With this sign you shall conquer,” he may have legitimized the cross as the symbol of Christianity, but he did not invent it. As we have noted, it was Jesus himself who linked the symbol of the cross with discipleship, and Paul is the first we have record of who transforms the shame and humiliation of crucifixion into the symbol of God’s transformative power. The cross was one element in the trilogy of that transformative power that takes place through Gethsemane—the cross and the Resurrection. These elements do not stand alone but are interwoven with each other. Although Latter-day Saints may have for a time concentrated on Gethsemane and the Resurrection, such a focus does not do justice to our scriptural texts, which teach the importance of the cross in that trilogy, so much so that at times those scriptural texts even employ the cross as the symbol of the Atonement. As Paul taught the Romans, we are “reconciled to God by the death of his Son . . . , by whom we have now received the atonement” (Romans 5:10–11). Thus, there is much to be gained from a careful study of Jesus’s crucifixion.

Further Reading

Bergeron, Joseph W. "The Crucifixion of Jesus: Review of Hypothesized Mechanisms of Death and Implications of Shock and Trauma-Induced Coagulopathy." Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine 19 (2013): 113-16.

Chapman, David W. Ancient Jewish and Christian Perceptions of Crucifixion. Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 244. Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck, 2008.

Cook, John Granger. Crucifixion in the Mediterranean World. 2nd ed. Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 327. Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck, 2019.

Longenecker, Bruce W. The Cross before Constantine: The Early Life of a Christian Symbol. Minneapolis: Fortress, 2015.

Maslen, Matthew, and Piers D. Mitchel. "Medical theories on the Cause of Death in Crucifixion." Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 99 (2006): 185-88.

Millet, Robert L. What Happened to the Cross? Distinctive LDS Teachings. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2007.

Notes

[1] Gaye Strathearn, “Christ’s Crucifixion: Reclamation of the Cross,” Religious Educator 14, no. 1 (2013): 45–57, and reprinted, with modifications, in With Healing in His Wings, ed. Camille Fronk Olson and Thomas A. Wayment (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2013), 55–79.

[2] Brigham Young, Journal of Discourses, 26 vols. (London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1854–86), 12:33–34. See also Robert L. Millet, What Happened to the Cross? Distinctive LDS Teachings (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2007), 113.

[3] Two early Christian texts assume that Jesus was nailed to his cross. Ignatius, writes that he was “truly nailed (Greek kathēlōmenon) in the flesh for us under Pontius Pilate and Herod the tetrarch” (To the Smyrnaeans 1.2), and the Gospel of Peter says that after the Crucifixion, “the Jews drew the nails from the hands and feet of the Lord and laid him on the earth” (6.21).

[4] However, John records that when the apostles reported to Thomas that they had seen the resurrected Jesus, Thomas’ response indicates that nails were used in his hands (John 20:25).

[5] Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 18.63–64). For a discussion of the text critical issues of this passage, see David W. Chapman, Ancient Jewish and Christian Perceptions of Crucifixion, Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 2. Reihe 244 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2008), 78–80. Tacitus, Annals 15.44.

[6] John Granger Cook, Crucifixion in the Mediterranean World, Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 327 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2014), 2.

[7] J. Schneider, “σταυρός,” in Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, 10 vols. (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1971), 7:573.

[8] Josephus records that on at least one occasion a Jew, Alexander Jannaeus, crucified eight hundred other Jews (Jewish War 1.96–98; Antiquities of the Jews 13:379–80). It has been argued that the Nahum Pesher from the Dead Sea Scrolls makes reference to Alexander’s crucifixions: “Its interpretation [of Nahum 2:13] concerns the Angry Lion [who filled his den with a mass of corpses, carrying out rev]enge against those looking for easy interpretations, who hanged living men [from the tree, committing an atrocity which had not been committed] in Israel since ancient times, for it is horrible for the one hanged alive from the tree” (4Q169 3–4 I 6–8). See Chapman, Ancient Jewish and Christian Perceptions of Crucifixion, 57–66.

[9] Dialogue: De Consolatione ad Marciam 20.3. Josephus also notes that crucifixions took place in different forms: “So the soldiers out of the wrath and hatred they bore the Jews, nailed those they caught, one after one way, and another after another, to the crosses, by way of jest; when their multitude was so great, that room was wanting for the crosses, and crosses wanting for the bodies” (War 5:451).

[10] Deuteronomy 21:22; Galatians 3:13. For a discussion of Jewish interpretation of Deuteronomy 21:23 as form of crucifixion, see Chapman, Ancient Jewish and Christian Perceptions of Crucifixion, 117–47.

[11] John Granger Cook shows an example on a flask made of African red slip ware depicting a criminal suspended on a stake and being attacked by wild beasts. In these cases, the execution was a combination of crucifixion on a pole and being attacked by wild beasts. “Crucifixion as Spectacle in Roman Campania,” Novum Testamentum 54 (2012): 77–80.

[12] In a mock legal prosecution attributed to Lucian, the author argues that the cross (Greek sTAUros) receives its name from the Greek letter Tau: “Men weep and bewail their lot and curse Cadmus over and over for putting Tau into the alphabet, for they that their tyrants, following his figure and imitating his build, have fashioned timbers in the same shape and crucify men upon them; and that it is from him that the sorry device gets its sorry name (stauros, cross). For all this do you not think that Tau deserves to die many times over? As for me, I hold that in all justice we can only punish Tau by making a T of him.” Consonants at Law: Sigma vs Tau, in the Court of the Seven Vowels 12, English translation from A. M. Harmon in The Works of Lucian, 8 vols., Loeb Classical Library 14 (Harvard University Press, 1972), 1:408–9.

[13] Bruce W. Longenecker, The Cross Before Constantine: The Early Life of a Christian Symbol (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2015), 12–13.

[14] “They were accordingly scourged and subjected to torture of every description, before being killed, and then crucified” (Josephus, Jewish War 5.449).

[15] “Some hang a man head downwards” (Seneca, Dialogue: De Consolatione ad Marciam 20.3); “some hang their victims with head toward the ground” (Josephus, Jewish War 5.451).

[16] In 1956 a marble inscription (lex Puteolana) was found in a taberna (single room shop) close to the amphitheater of Puteoli, a municipality in Campania, Italy. It gives specific requirements for workers who were contracted to perform crucifixions: “Whoever will want to exact punishment on a male slave or female slave at private expense, as he [the owner] who wants the [punishment] to be inflicted, he [the contractor] exacts the punishment in this manner: if he wants [him] to bring the patibulum to the cross, the contractor will have to provide wooden posts, chains, and cords for the floggers and the floggers themselves. And anyone who will want to exact punishment will have to give four sesterces for each of the workers who bring the patibulum and for the floggers and also for the executioner. Whenever a magistrate exacts punishment at public expense, so shall he decree; and whenever it will have been ordered, the contractor must be ready to carry out the punishment, to set up stakes/

[17] See the list in the subject index under “crimes leading to crucifixion” in Cook, Crucifixion in the Mediterranean World, 518.

[18] Cook, “Crucifixion and Burial,” New Testament Studies 57 (2011): 197–198; Chapman, Ancient Jewish and Christian Perceptions of Crucifixion, 78–86.

[19] Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 17.295; Jewish War 2.75.

[20] Josephus, Jewish War 2.253.

[21] Josephus, Jewish War 7.203.

[22] Seneca, Epistles 101.13–14, English translation by Richard M. Gummere in Loeb Classical Library 77 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1925), 3:164–65.

[23] Herodotus records that one Sandoces was crucified by Darius because he was bribed to give an unjust judgment. When Darius found out that Sandoces had ably served the royal house, he changed his mind and ordered that Sandoces be taken down (7.194). Another example is Josephus’s account of when he viewed a crucifixion and recognized three of the victims. He appealed to Titus to take them down. Although all three were cared for, he notes that “yet two of them died under the physician’s hands, while the third recovered” (Life of Flavius, 420–21). In addition to these two examples, Ovid indicates that those who were being crucified still offered prayers in hope of surviving the ordeal (Ovid, Letters from the Black Sea 1.6.37–40). For a description, see Cook, Crucifixion in the Mediterranean World, 92–93.

[24] Quintilian, Declamations 274.13, English translation in Quintilian: The Lesser Declamations, 2 vols., ed. and trans. D. R. Shackleton Bailey, Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006), 1:259.

[25] Cicero, For Rabirius on a Charge of Treason, 5.16.

[26] Cicero condemned Gaius Verres, the governor of Sicily, for not taking into account Publius Gavius’s claims of citizenship when sentencing him to be crucified (Against Verres 2.5.157–62). For a discussion of Cicero’s contempt for crucifying Roman citizens, see Cook, Crucifixion in the Mediterranean World, 62–74. Suetonius condemned Galba for crucifying a guardian who had poisoned his ward. This man also pleaded for a mitigating sentence because of his citizenship. Galba famously honored that citizenship by ordering the guardian’s cross to be constructed higher than usual, and painting it white (Suetonius, Galba 9). See also Josephus, Jewish War, 2:308.

[27] W. T. MacCary and M. M. Willcock, ed., Plautus, Casina (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976), 111. See also Cook, Crucifixion in the Mediterranean World, 52–53n9.

[28] Plautus, Miles Gloriosus, 372–73, English translation by Wolfgang De Melo in Loeb Classical Library 163 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011), 180–81.

[29] Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 12.255–56; Jewish War 2.307; Dionysius of Halicarnasus, Roman Antiquities 5.51.3; 12.6.7; Cicero, Against Verres, 2.5.160–62.

[30] Philo, Flaccus, 10.84.

[31] Cicero, Against Verres, 2.5.163.

[32] Plutarch, “On the Delays of Devine Vengeance,” Moralia 7.554 A, B, English translation by Philip H De Lacy and Benedict Einarson, Plutarch’s Moralia, 15 vols.; Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1959), 7:215. See also the description in Chariton’s romantic novel, Chaeras and Callirhoe, where Chaereas describes his ordeal of carrying a cross and being delivered to the executioner (4.3.5).

[33] “Let him carry the gibbet [Latin patibulum] through the city and then let him be put on the cross” (Plautus, The Charcoal Play, 2).

[34] Latin text with English translation in Cook, “Envisioning Crucifixion,” 265–66.

[35] Xenophon of Ephesus says that using ropes was an Egyptian practice: “They raised the cross and bound him to it, tying his hands and feet tight with ropes.” The Story of Anithia and Habrocomes 4.2.1, English translation by Jeffrey Henderson in Loeb Classical Library 69 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), 311. The Acts of Andrew says that Andrew’s feet and armpits were bound with ropes, without the use of any nails (148). The Pereire gem is, according to Roy D. Kotansky, “the earliest representation of the crucified Jesus, in any medium.” “The Magic ‘Crucifixion Gem’ in the Britism Museum,” Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 57 (2017): 632. It shows the crucified Jesus being attached to the cross with fetters. This gem is difficult to date. Cook simply assigns it to a time “when the Romans were still practicing crucifixion” (Crucifixion in the Mediterranean World, 425). J. Spier and Felicity Harley, however, are more specific in their dating. They suggest that “the style of carving, material, and inscription are all typical of the large group of Greco-Roman magical amulets originating in Egypt and Syria during the second and third centuries.” Picturing the Bible. The Earliest Christian Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), 228.

[36] Pliny, Natural History 28.10.46.

[37] Josephus, Jewish War 2.308.

[38] Josephus, Jewish War 5:451. Philo uses the concept of nailing (Greek prosēloō) people to the cross as a metaphor in one of his philosophical discussions (On Dreams That Are God Sent 2.213).

[39] Joseph Zias and Eliezer Sekeles, “The Crucified Man from Giv’at ha Mivtar: A Reappraisal,” Israel Exploration Journal 35 (1985): 22–27.

[40] The Puteoli crucifixion graffito is variously dated between the late first and mid third century. Cook believes that it “is probably from the era of Trajan.” Cook, Crucifixion in the Mediterranean World, 6.

[41] Zias and Sekeles, “The Crucified Man,” 26–27.

[42] Irenaeus writes, “The very form of the cross too has five extremities, two in length, two in breadth, and one in the middle, on which [last] the person rests who is fixed by the nails” (Irenaeus, Against Heresies 2.24.4). Likewise, Tertullian describes, “Every piece of timber which is fixed in the ground in an erect position is a part of a cross, and indeed the greater portion of its mass. But an entire cross is attributed to us, with its transverse beam, of course, and its projecting seat” (Tertullian, Against the Nations 1.12.3–4).

[43] The Palatine graffito also has a board for the victim to stand on.

[44] Artemidorus Daldianus, Oneirokritika 2.53. English translation from Cook, Crucifixion in the Mediterranean World, 192.

[45] Walter Bauer, William F. Arndt, F. Wilbur Gingrich, and Frederick W. Danker, A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and other Early Christian Literature, 3d ed.; rev. and ed. Frederick W. Danker (Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press, 2000), s.v. γυμνος; Cook, Crucifixion in the Mediterranean World, 192, n. 149. See also Cook, Crucifixion in the Mediterranean World, 193–94; Raymond Brown, The Death of the Messiah: From Gethsemane to the Grave. A Commentary on the Passion Narratives in the Four Gospels, 2 vols., the Anchor Bible Reference Library (New York: Doubleday, 1994), 2:952–53. My thanks to my colleague Nicholas J. Frederick for his help with this reference.

[46] Melito of Sardis, Peri Pascha 97.

[47] Acts of Pilate, 10:1. English translation in Whilhelm Schneemelcher, ed., New Testament Apocrypha, Volume 1: Gospels and Related Writings, rev. ed.; trans. R. McL. Wilson (Louisville, KY: Westminster/

[48] Suetonius, The Life of Augustus 13:1–2; Juvenal, Satire 14:77–78; Acts of Andrew 148.

[49] Plautus, Miles Gloriosus, 372–73.

[50] Corpus Iuris Civilis, Pandectae 48.24.1–3. English translation by Alan Watson in The Digest of Justinian, 4 vols. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009), 4:377.

[51] Philo, Flaccus 83. For a detailed discussion the burial of crucified individuals, see Cook, “Crucifixion and Burial,” 193–213.

[52] For examples, see Suetonius, The Life of Augustus 67.2; Ammianus Marcellinus 14.9.8; Polybius 1.80.13.

[53] One late Christian text, the Acts of Andrew, does combine the ideas of breaking legs with crucifixion, although it is a negative example: the proconsul, Aegeates, sent Andrew, “to be crucified, ordering his executioners to leave his sinews uncut [i.e., to leave his knees alone; tas ankulas kataleiphthnai], as he thought, that he might punish him more.” English translation in Schneemelcher, New Testament Apocrypha, 2:147.

[54] Pseudo Quintilian, The Major Declamations 6.9.

[55] Cook, Crucifixion in the Mediterranean World, 430–35.

[56] F. T. Zugibe, The Crucifixion of Jesus: A Forensic Enquiry (New York: M. Evans, 2005), 85–89, 107–2.

[57] Joseph W. Bergeron, “The Crucifixion of Jesus: Review of Hypothesized Mechanisms of Death and Implications of Shock and Trauma-Induced Coagulopathy,” Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine 19 (2013): 114.

[58] See the medical review by Bergeron, “The Crucifixion of Jesus,” 113–16.

[59] Matthew Maslen, Piers D. Mitchell, “Medical Theories on the Cause of Death in Crucifixion,” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 99 (2006): 185–88.

[60] Neal A. Maxwell, “‘Swallowed Up in the Will of the Father,’” Ensign, November 1995, 24.

[61] In Jewish literature, crucifixion was seen as one type of Deuteronomy’s “hanging on a tree.” For a detailed discussion, see Chapman, Ancient Jewish and Christian Perceptions of Crucifixion, 117–77. Like Paul, a number of early Christian writers felt the need to reconcile Jesus’s crucifixion with this passage in Deuteronomy (Justin Martyr, Dialogue of Justin Martyr 93–96; Irenaeus, Against Heresies 3.18; Tertullian, Against Marcion 3.18; 5.3).

[62] Lucian, The Death of Peregrinus, 13, 11, in Lucian: Selected Dialogues, trans. Desmond Costa (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 77.

[63] Justin Martyr, First Apology of Justin 1.13.4. English translation in Cyril C. Richardson, ed., Early Christian Fathers (New York: Collier Books, Macmillan, 1970), 249.

[64] Minucius Felix, Octavius 9.4. English translation by R. R. Glover and G. H. Rendall in Loeb Classical Library (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1984), 337.

[65] George M. A. Hanfmann, “The Crucified Donkey Man: Achaios and Jesus,” in Studies in Classical Art and Archaeology: A Tribute to Peter Heinrich von Blanckenhagen, ed. Günter Kopcke and Mary B. Moore (Locust Valley, NY: J. J. Augustin, 1979), 205–7, pl. 55, 1.2; Peter Lampe, From Paul to Valentinus: Christians at Rome in the First Two Centuries, trans. Michael Steinhauser, ed. Marshall D. Johnson (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2003), 338; G. H. R. Horsley, New Documents Illustrating Early Christianity: A Review of the Greek Inscriptions and Papyri Published in 1979 (North Ryde, NSW: Ancient History Documentary Research Centre, Macquarie University, 1987), 137.

[66] The charge that Christians worshipped a god with an ass’s head is one that early Christian writers had to deal with. For example, see Tertullian, To the Nations 11, 14; and Minucius Felix, Octavius 9.3. Jews also had to deal with this type of charge. Josephus recounts that Apion claimed a man by the name of Zabidus entered their temple and “snatched up the golden head of the pack-ass.” Josephus shows his disdain for the account by inserting the comment “as he facetiously calls it.” Josephus, Against Apion 2.114, English translation by H. St. J. Thackeray in Loeb Classical Library 186 (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1926), 339.

[67] For a detailed discussion of what Jews thought about crucifixion, see Chapman, Ancient Jewish and Christian Perceptions of Crucifixion, 211–62.

[68] Joseph F. Smith, Gospel Doctrine: Selections from The Sermons and Writings of Joseph F. Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1986), 91.

[69] Gordon D. Fee, The First Epistle to the Corinthians, The New International Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1987), 548. This is one of the few places where Paul seems to be quoting from the Jesus tradition. We do not know where or how he received this information.

[70] Anthony C. Thiselton, The First Epistle to the Corinthians, The New International Greek Testament Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2000), 887.

[71] Kenneth L. Woodward, “What Mormons Believe,” Newsweek, September 1, 1980), 70. The word “Easter” is found only once in the King James version of the Bible (Acts 12:4). It is a translation of the Greek word pascha, which is usually translated as Passover.

[72] The word “Easter” is found only once in Acts 12:4 (KJV). It is a translation of the Greek word pascha or “Passover,” which is what many English translations prefer (NRSV, NIV, ESV).

[73] Joseph Fielding Smith, The Restoration of All Things (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1945), 199; See also idem., Seek Ye Earnestly (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1970), 119–21. I am grateful for the help of my colleague Robert L. Millet in bringing the quotes of the Restoration Prophets to my attention.

[74] Joseph Fielding Smith, Doctrines of Salvation, comp. Bruce R. McConkie (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1954–56), 1:130. See also Bruce R. McConkie, Doctrinal New Testament Commentary (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1979), 1:774–75.

[75] Compare John 12:32–33, where Jesus says, “And I, if I be lifted up from the earth, will draw all men unto me. This he said, signifying what death he should die.”

[76] Joseph Smith, History, 1838–1856, volume C-1 [2 November 1838–31 July 1842], 1014, https://

[77] Many of the prophets have taught the importance of the cross. For example, see John Taylor, The Gospel Kingdom: Selections from the writings and discourses of John Taylor (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1987), 114; Joseph F. Smith, Gospel Doctrine, 91; Heber J. Grant, Charles W. Penrose, and Anthony W. Ivins, in James R. Clark, Messages of the First Presidency, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1967), 5:208; Ezra Taft Benson, Teachings of Ezra Taft Benson, ed. Reed A. Benson (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1988), 14; Gordon B. Hinckley, Christmas devotional, December 8, 1996, as cited in Church News, December 14, 1996, 3–4.

[78] Jeffery R. Holland, “None Were with Him,” Ensign, May 2009, 88.

[79] Jeffrey R. Holland, “Teaching, Preaching, Healing,” Ensign, January 2003, 42.

[80] Holland, “Teaching, Preaching, Healing,” 42.