Clothing and Textiles in the New Testament

Kristin H. South and Anita Cramer Wells

Kristin H. South and Anita Cramer Wells, "Clothing and Textiles in the New Testament," in New Testament History, Culture, and Society: A Background to the Texts of the New Testament, ed. Lincoln H. Blumell (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 638-658.

Kristin H. South is a member of the History Department at The Waterford School in Sandy, Utah.

Anita Cramer Wells received a master’s degree in library and information science from Drexel University, teaches early-morning seminary, and volunteers as an editor for Book of Mormon Central.

“For I was an hungered, and ye gave me meat: I was thirsty, and ye gave me drink: I was a stranger and ye took me in: naked, and ye clothed me” (Matthew 25:35–36). With these words, Jesus reminded his disciples of the importance of kindness to others while also listing the basic necessities of life––food, water, shelter, and clothing. Each of these elements is so fundamental to daily functioning that people can sometimes imagine they have always been the same as they are today, or overlook them entirely. Yet textual and archaeological discoveries allow us to better understand and visualize the sartorial context of New Testament times. This chapter will outline some of what is known from the biblical era about clothing, the last item on Christ’s list of fundamental life elements.

Clothing, including nontextile elements such as jewelry, footwear, and even armor, receives numerous mentions in the New Testament, indicating its importance as a marker of status, both worldly and spiritual. When Jesus counseled his disciples to regard the body as more than its raiment (Matthew 6:25), he was acknowledging the common human tendency to judge others––and ourselves––based on the clothing that we wear. Modern social science has shown that clothing is, in fact, one of the most direct and accurate markers of social standing (4 Nephi 24–25) and that we notice it immediately when meeting someone new.

The role of clothing as a way of displaying social status is ubiquitous in New Testament usage: when John the Baptist wore clothing made of coarse camel hair with a leather belt (Mark 1:6), we can surmise quickly that not only his clothing, but also his prophetic vision, his blunt honesty, and his role in society would be the opposite of those “clothed in soft raiments” who were “gorgeously apparelled” (Luke 7:25). Likewise, when the father in the parable of the prodigal son wished to welcome the wayward home, he was clothed in the best robe available, along with a ring and a pair of shoes (Luke 15:22). The change in the appearance of this hungry and desperate young man would have been striking and would have clearly shown to all who saw him that he had returned to his status as a son of the household instead of the servant among pigs that his riotous living had reduced him to becoming.

Because clothing serves such an important function in marking our place in society, we can often forget that its visual cues provide symbolic understanding: there is nothing inherent in the placement of precious stones and metal upon one’s head that creates a king, but the crown is a universal symbol of royalty nonetheless. When a mocking crowd adorned Christ in a costly dyed robe, along with a crown of thorns and a reed for a scepter (Matthew 27:29; John 19:2, 5), their intention to subvert and twist the symbolism of royalty was immediately apparent.

This chapter begins with a summary of what is known of actual clothing from New Testament times, then discusses what was distinctive about the clothing of the Jews from whom the earliest Christians were drawn. It then surveys the ways that clothing references add to the richness of New Testament teachings, including with respect to that most significant series of events, the crucifixion, burial, and resurrection of Christ.

Ancient Evidence

Despite the many references to textiles in scripture, actual evidence of ancient clothing culture can be difficult to locate. This is due in part to the antiquity of the time, two millennia ago, but also to the fragile nature of clothing. With regular use, cloth breaks down and is eventually discarded or reused in other forms, such as cleaning cloths, pillows, rugs, or filling materials (hence Isaiah’s prophecy that the earth would “wax old like a garment” in 51:6). The lifecycle of clothing is acknowledged in a parable in Matthew 9:16 (Mark 2:21) when Jesus asked rhetorically if a person would attempt to mend an old piece of cloth by patching it with a new one. The obvious answer––no––is predicated on the realization that the organic materials constituting cloth soften and lose their strength over time and that such an attempt to combine the strong new cloth with a weakened older one would lead to an even larger hole. In a more general sense, Jesus was referencing the mundane and familiar in order to point out the futility of attempting to categorize him and his movement in old ways. He was the new cloth or the new wine (Matthew 9:17, Mark 2:22) whose ministry and mission required new understanding.

The first line of inquiry into ancient clothing culture, then, must come from the biblical sources themselves and from other associated writings that describe and define ancient wardrobe options. In addition, while archaeological remains are scanty, they do exist and have played an extremely important role in opening up the study of ancient clothing. Artistic representations from the time can also shed light on ancient customs, as can modern parallels, if used cautiously.

Ancient Textile Terminologies

Because the New Testament has come down to us in Greek, a look at the original Greek terms translated as “cloak,” “robe,” and so on can also be useful. Many of these terms have now been matched to actual archaeological finds, so we have direct knowledge of the type of clothing Jesus meant when he urged his followers to give to a litigious neighbor his cloak [himation] as well as his already-taken coat [chiton] (Matthew 5:40).

The himation, usually translated as “cloak” (but spelled “cloke” in the King James translation) was a billowing outer garment, worn by both men and women. For men, it was usually draped over the left shoulder and under the right arm, in order to keep the right arm more easily accessible, while women wore it fastened at the shoulder with a brooch. The classical himation of Greco-Roman use was a large rectangular piece of cloth worn wrapped around the body, but a local fashion (illustrated in the burial statues of Palmyra, in Syria, and in the Fayum portraits in Egypt) was a more tightly fitted himation, often with woven-in patterns such as a large H along one end or the shape of the Greek letter gamma (Γ) in each of the four corners. The Roman pallium for men or palla for women was an adaptation of the himation, a colorful mantle that could have several colors in striped or checked patterns. Women might wear it as the himation or bring it across the back of the head to cover their hair as well. With this context, Jesus’s admonition to give away one’s cloak betrays an astonishing generosity: a himation was laboriously handwoven, and its size and corresponding amount of thread made it an expensive item. (Insert Image: Image 1 Roman Woman and Himation)

This bronze miniature from the 1st to 2nd century shows a Roman woman covered in a himation, including part of it draped over her head. Its generous size allows it to envelop her and conceal her inner layers of clothing.

This bronze miniature from the 1st to 2nd century shows a Roman woman covered in a himation, including part of it draped over her head. Its generous size allows it to envelop her and conceal her inner layers of clothing.

The most common element of daily clothing was the chiton. Originally a Semitic term [k-t-n, (Hebrew kuttoneth)], the English term “cotton” is ultimately derived from this word. In antiquity, however, a chiton was a sleeveless tunic of linen or wool, woven in one or two pieces, with narrow colored stripes (clavi) down either side from the shoulder to the bottom end of the garment. A chiton could be of any color, and examples from eastern Mediterranean lands include red, purple, blue, green, yellow, pink, peach, and orange.

Starting in the third century AD, a new fashion emerged, and people took to wearing tunics with long, wide sleeves (dalmatica) or with long, tight sleeves (sticharion). Both types were usually woven in separate sections with the sleeves sewn onto the tunic.

Women were expected to cover their hair in public (1 Corinthians 11:5–6). The Hebrew ma’aforet is the same as Latin mafortium (Greek mafortus) and seems to reference a piece of cloth meant to be worn as a veil or headdress both for women and for priests. They could be dyed as well and were usually mentioned in wedding dowries as part of an ensemble that also included a dalmatic. So commonly were the two items mentioned together that they came to be known by a compound word: dalmaticomafortus. This combination was most commonly known in the eastern Mediterranean world and hence is a strong candidate for the most usual wardrobe of New Testament women. Arab women at this time were often veiled across the face, while Greek and Hebrew women covered only their hair. Egyptian Christian women of the following centuries were often buried with their hair plaited and covered in netlike sprang headgear made of green, yellow, and red wool, which they would have worn in life too.

This image of nailless sandals, from 4th-century Egypt, shows the multiple layers of leather that were used to make sandals in Judea as well.

This image of nailless sandals, from 4th-century Egypt, shows the multiple layers of leather that were used to make sandals in Judea as well.

According to both written tradition and archaeology, Jewish footwear consisted of multiple layers of leather pressed and stitched together with leather thongs to form a nailless sandal. This was in distinction from the sandals worn by members of the Roman military, whose metal hobnails made a loud clatter as one approached and also left a distinctive footprint in the dust. The prohibition on wearing sandals with nails thus protected the population in times of danger by letting them know when a soldier was approaching. When John the Baptist declared himself unworthy to loosen or bear the shoes of his cousin Jesus (for instance, Mark 1:7; Acts 13:25), he was probably speaking of these nailless sandals.

Archaeological Textile Finds

This extreme fragility of cloth and its tendency to deteriorate over time makes it difficult to state with certainty what New Testament–era clothing would have looked like. The problem is true of organic materials in general: in many parts of the world, only stone monuments and pottery fragments remain to attest to the lifestyles of ancient peoples. Luckily, however, the dry, arid climate of ancient Judea has allowed some textiles to be preserved, most notably in areas beyond the rush of regular human interference. Important instances of such preservation have been discovered at infrequently used caves (Qumran, the Cave of Letters), a desert cemetery on the banks of the Dead Sea (Khirbet Qazone), and the famous hill fortress of Masada.

The Bar Kokhba Revolt, AD 132–35, set Jewish revolutionaries against the ruling Roman authorities. Barred from entry into Jerusalem, many Jews fled to live and hide in high, barren caves near the Dead Sea. Christianized Jews, too, although not participating fully in the revolt––how could they view Bar Kokhba as the Messiah when they already believed in Christ?––were punished by Roman authorities and denied entrance to Jerusalem, but the documents in the caves indicate it was the participants in the revolution and their family members who hid in the caves. Thus, we are examining the wardrobes of Mosaic law–observant Jews when we look at the clothing from the Cave of Letters and Murabba’at. The burial site of Khirbet Qazone, very nearby on the other side of the Dead Sea, contains a population buried in very similar items of clothing. Dated to the first to third centuries AD, it appears to have served predominantly Nabataean but also Jewish populations.

What we find at each of these sites is clothing of a high quality, consistent in type across religious and national divides. At Khirbet Qazone, the major types of clothing included tunics, mantles, and scarves or veils for women, plus some possible loincloths. Nearly all were made of wool. The veils were made in bright colors––yellow, pink, scarlet––and two of the tunics were apricot colored, showing that women’s clothing went far beyond the undyed hues of browns and beige. At the Cave of Letters, another burial site, an entire cache of items that constituted a woman’s personal belongings was found, including a mirror, cosmetics, weaving items, and articles that an astute scholar has recognized as a brassiere (strophion) and ragged cloths for use during menstruation.

Textiles at Murabba‘at employed twill techniques and crepe, colored with apricot, yellow, green, blue, brown, and red dyes. The finds also included a fragment of a rug of a type described by Athenaeus, a Greek-speaking Egyptian of the third century AD, in his conversations among “Dinner-Table Philosophers”[1] as the height of luxury: purple, with loops of wool on both sides. Regardless of original quality, the finds in this most desperate of habitable places had been patched and reused. Some linen was torn to strips, which in some cases appeared to have blood on them.

“Desperate” also describes the famous last stand of rebels at the hilltop fortress Masada in AD 73. Excavations at Masada in the 1960s revealed numerous textiles. These pieces include fragments of a variety of objects of daily wear: socks, hairnets, tunics, mantles, and cloaks, but the conquering Romans seem to have made off with everything of real value.

Textile finds from more distant surrounding areas, such as the deserts of Jordan and Syria and the wealthy and well-preserved neighboring region of Egypt, provide additional clues to the cloth options of the day. The spice route that brought myrrh and frankincense up from the south of the Arabian peninsula included several fortified way stations at which excavators have discovered fabric remains that shed light on the textile culture of the wealthy Nabataeans traders who frequented the route. At ‘En Rahel, a Negev way station in use from the mid-second century BC to the first century AD, textile fragments of goat hair, wool, and camel hair were all found. A ring-shaped cushion found at ‘En Rahel would have been placed on the head to facilitate the carrying of jars and other burdens. Sha’ar Ramon and Mo’a, two other points in the Negev along the Incense Route in use from the first to the third centuries AD, also included a large majority of wool textiles, with additional pieces of goat hair and camel hair. Linen, the most common textile fabric in neighboring Egypt, is represented in very few pieces at these sites, but does exist. Additional finds of textile-making implements––thread, fleece, and spindle whorls––shows that weaving and spinning were performed on site.

In sum, the evidence––literary and archaeological––indicates that clothing options in ancient eastern Mediterranean lands during New Testament times were fairly limited and mirrored those of other ethnicities and nationalities throughout the Greco-Roman sphere of influence. Both men and women wore shapeless but colorful rectangular tunics, often with two narrow stripes of color as the only decoration. The tunics were complemented with outer cloaks or mantles and, in the case of women, veils or headscarves. Intimate underlayers of linen could include loincloths and brassieres plus more closely fitted tunics. Religious differences in clothing among the Jewish population, called for in the Mosaic law, are discussed below. Christians, however, dressed very much like their neighbors.[2]

Artistic Representation

In addition to literary and direct archaeological evidence, scholars look to ancient art to see how people represented themselves. However, due to Jewish religious restrictions on creating potentially idolatrous artwork, there is a dearth of direct biblical information. Yet wall paintings in the synagogue and house church at Dura-Europos in Syria, statuary throughout the ancient world, and mosaics at Ravenna, Italy, provide useful and interesting information about ancient fashion and society, often clarifying textual references and showing how textiles were meant to be worn.

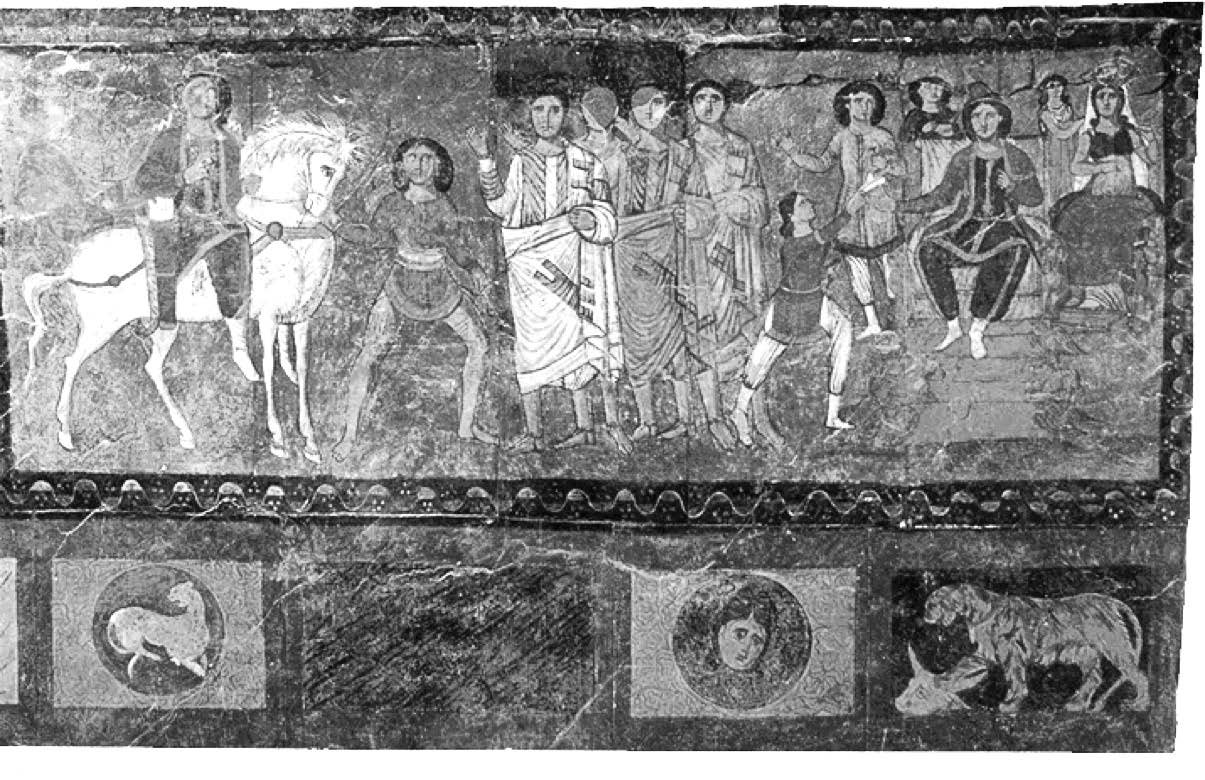

Image of Haman leading Mordecai before the thrones of Ahasuerus and Esther. From the synagogue at Dura-Europos. Note the varieties of clothing shown, including short tunics or chitons, long outer himations, and Ahasuerus dressed in the Persian style, with long trousers beneath his tunic.

Image of Haman leading Mordecai before the thrones of Ahasuerus and Esther. From the synagogue at Dura-Europos. Note the varieties of clothing shown, including short tunics or chitons, long outer himations, and Ahasuerus dressed in the Persian style, with long trousers beneath his tunic.

Dura-Europos, on the eastern edge of modern-day Syria, was excavated in the 1930s and yielded evidence for the earliest-known Christian house church, from the mid-third century. It contained multiple frescoes on Christian themes, such as Jesus healing a paralytic; the Good Shepherd, and the three Marys visiting Christ’s tomb. Although fashion is not the intentional topic of the frescoes, they reveal what Christians in the third century wore, or considered appropriate for people in Christ’s time to have worn. The clothing of the women always goes to their feet, while the men are usually dressed in typical Greco-Roman fashions––shorter tunics with cloaks. Frescoes in the nearby synagogue show people in current fashions but also portray men in Persian-style fitted tunics over trousers, perhaps archaizing the stories from the past that were depicted on the walls.

Ravenna became the capital of the western Roman empire in AD 402, after the emperors had declared Christianity the official religion of the empire. Art-filled buildings appropriate to a capital and to a center of Christian worship were built in the following two centuries and have been preserved, creating a legacy of historic importance. The clothing depicted on the walls at Ravenna is rich in color and design, as might be expected of the rulers of a vast and still-powerful empire. Christian figures are depicted in lush, well-preserved detail. The mosaics at Ravenna reveal an upper-class strata of society who wore richly decorated, colorful, and flowing pieces of clothing, along with jewelry and decorative hair ornaments. As such, they serve better to demonstrate a hierarchical ideal than to detail everyday wear.

Mosaic at Ravenna.

Mosaic at Ravenna.

Modern Parallels

Another potentially interesting source of information about ancient clothing is the parallels we can draw from the modern lifestyles of those in the region who continue to live according to traditional––often nomadic––patterns of life. Such parallels, however, must be drawn with great caution. Just because a way of life appears old or unusual to our eyes is no promise of its antiquity. Nevertheless, it does appear to be true that some aspects of life in the region have not changed significantly since ancient times. One such area is the nomadic lifestyle of those who herd sheep and goats throughout the area, covering their heads from the desert sun. Of significance to Christianity because of the frequent scriptural allusions to Christ as the Good Shepherd and Christian followers as his flock, some biblical scholars have made much of the parallels between modern shepherding practices and what they may illuminate about ancient times.

One such report, of note for textile studies, comes from a nineteenth-century British vicar who observed Palestinian shepherds wearing a flowing tunic-style robe that they could secure at the waist with the addition of a belt, creating a pocket in which to carry a baby lamb against their own bodies. This image of a loving shepherd, cuddling a lamb close to his heart, carries obvious resonance with the Good Shepherd as described in Isaiah 40:11: “He shall gather the lambs with his arm, and carry them in his bosom.”

In addition, literary, archaeological, artistic, and ethnographic evidences can provide a surprising amount of factual detail about ancient clothing practices despite the fragility of textile remains.

“Strength and Honor”: Women’s Work with Fibers and Dyes

Around the world throughout history, the making and shaping of textiles has been the work of women. This was true in ancient Israel as well. Among the idealized traits of a faithful Israelite wife were her abilities to work the raw materials of fibers into completed, dyed cloth available for household use or sale: “She seeketh wool, and flax, and worketh willingly with her hands. . . . She layeth her hands to the spindle, and her hands hold the distaff. . . . She is not afraid of the snow for her household: for all her household are clothed with scarlet. She maketh herself coverings of tapestry; her clothing is silk and purple. . . . She maketh fine linen, and selleth it; and delivereth girdles unto the merchant.” As a result of all of this industry and wisdom, “strength and honour are her clothing” (Proverbs 31:13, 19, 21–25).

Because wool takes dye very readily and linen does not, brightly colored ancient clothing is most often made of wool. (Silk, which also dyes easily and can accept bright and brilliant hues, was far more expensive and difficult to obtain.) According to some ancient sources and modern archaeological finds, weavers of Judea became well known for their work in wool, developing a distinctive method of dyeing and weaving their wool to create shaded bands of color that started out lightly dyed at the edges and gradually moved to intensely colored in the centers of the bands.

Linen was the everyday fiber of the ancient Mediterranean world. The Mishnah, a collection of oral rabbinic tradition from the third century AD, describes the preparation of flax and the weaving and use of linen, making a local origin for most everyday linen likely. It also specifies that people might expect to obtain their wool from Judea and their linen from Galilee while noting that fine Egyptian or Indian linen was required as part of the uniform of the high priest. Of the two, the more expensive was Egyptian linen.

Fine Egyptian linen, also known as “byssos” or “king’s linen,” was produced, at least during Pharaonic times, in Egyptian temples and reserved for priests, kings, and statues of the gods. Made from the finest underripe green flax, this is surely the linen that was used in the ancient Israelite temples as well. Marking great wealth and status, it was distinguished from everyday clothing by the degree of its refinement. Ancient cloth from Egypt, now in museums around the world, demonstrates why this might have been so: Egyptian linen could be woven to an extremely fine standard, with high thread counts and individual strands so thin that the gauzy cloth was insubstantial enough to see through. Latin sources referred to such linen as linea nebula (“misty linen”) or ventus textilis (“woven wind” or “woven air”).

Such cloth would have been confined to the upper strata of society due to the expense of making it and its impractical nature. The wearing or use of such fine linen, like costly purple garments, would have been a very visible social marker, much coveted among the status seekers of antiquity. Church father Tertullian, in the early third century AD, instructed women to shun the costly garments popular in his time and instead to clothe themselves in “the silk of uprightness, the fine linen of holiness, [and] the purple of modesty.”[3]

Everyday linen, however, was a more substantial cloth that grew softer and more absorbent with every washing. In the world of the Bible, as in European societies for centuries following, linen was the fiber of choice for soft, odor- and stain-repellent undergarments, and today the word “linens” refer to bedding, regardless of the fiber of their make. Linen is made from the soft, flexible inner fibers of the flax plant (linum usitatissimum). These fibers are made available through the retting process (“ret” is related to the word “rot”) by which the plant is soaked in water long enough for the tough outer fibers to be softened and loosened, after which they are stripped to obtain the flexible inner fibers. When Rahab of Jericho hid the Israelite spies on her roof in Joshua 2:6, she was able to do so because her roof contained multiple bundles of flax soaking in the sun. We thus learn that Rahab was involved in that most ancient of female professions, the preparation of flax fiber for weaving linen.

Although available for import from India and experimentally grown as early as 700 BC by Sennacherib in Nineveh, cotton never became a regular aspect of biblical clothing culture. Literary evidence for its use in Palestine, at Jericho, has been dated only to AD 575, but several archaeological findspots next to the Dead Sea demonstrate its existence there in small quantities in the Roman era. Similar in feel and use to linen, cotton eventually became the most common fiber for daily use in modern times, but in biblical and classical antiquity, linen and wool were far and away the most common sartorial staples.

According to Proverbs 31:22, an honorable Israelite wife could also have worked in purple. In reality, purple was a very costly and rare dye, the use of which was limited to elites. When Jesus wanted to stereotype a wealthy man in his parable of Luke 16:19, he declared that a “certain rich man” habitually dressed in “purple and fine linen.” The purple mentioned here is the expensive and scarce royal purple, obtained by combining the glands of thousands of murex snails to harvest the pigment-rich bromine they secrete. It is of note that Lydia, an early convert at Philippi, was a seller of such purple dye, or of cloth that had been treated with it (Acts 16:14). As such, she would have been accustomed to dealing with a wealthy clientele and was probably quite prosperous herself.

Royal purple, also called true purple, Tyrian purple, Phoenician purple, or imperial dye, was one of very few dyes known to antiquity that would keep its color over multiple washings and exposure to sunlight. This colorfastness, combined with the brilliance of the color itself, made it extremely valuable, while the difficulty of obtaining it raised its expense and desirability to the point that Roman rulers firmly proscribed its use, allowing only those of very high social standing to wear no more than narrow bands of purple in carefully defined areas. Archaeological finds in Egypt have shown, however, that even low-ranking officers, some soldiers, and possibly their civilian companions did make use of it as a display of affluence and influence.

If sumptuary laws could be proclaimed, however, they could also be circumvented. False purple was very popular among those who could not afford true purple, or whose social circumstances did not allow their use of it. This imitation dye, created by the combination of a red (usually madder) and a blue (plant-derived indigo) resembled true purple. In one cemetery in Egypt, filled with third- to sixth-century Christians, for instance, false purple clavi (vertical stripes) are the most common color in use apart from undyed wool and linen.

Facility with textiles continued to be a mark of a woman’s good character into New Testament times. The disciple Tabitha was praised for all “the coats and garments” (Acts 9:39) she had made in her lifetime for the widows, evidence of the good works that provoked a miraculous resuscitation from the dead by Peter.

Laying the Warp: Old Testament Continuities

Because the Jewish people of the New Testament era attempted to live the Mosaic law, any view of clothing in the time of Jesus must be filtered through the lens of their religious past. Throughout the Old Testament, clothing performed important symbolic and social functions that the people of the New Testament understood and referenced.

The Bible starts with a creation account that depicts Deity covering the bare planet earth with water and land, plants and animals. The sky is accessorized with heavenly bodies and glowing lights. God clothed his creation from the beginning; light and water are both seen as garments for the earth in the imagery of Psalm 104. In reference to this event, the Lord even asks Job, “Where wast thou when I . . . made the cloud a garment thereof, and thick darkness a swaddlingband for it?” (Job 38:4, 9). Humankind was the next adornment to come, and Job described that creation in wardrobe terms: “Thou hast clothed me with skin and flesh” (Job 10:11). Yet that naked state of innocence in the garden eventually gave way to millennia of fashion choices. From Adam and Eve’s attempt to make leaf aprons that the Lord replaced with garments (of skin, symbolizing the sacrifice of the Lamb, but that word ‘or is also a homophone with the Hebrew word for light) to the specifications for priestly clothing in the Israelite temple thousands of years later, how humans covered their mortal body mattered in the Bible and to God.

The law of Moses specified some clothing guidelines that were important in both the Old and New Testament: tassels must be present on coat corners for men; clothing should not be woven of mixed fabrics (sha’atnez); and cross-dressing was forbidden. Numbers 15:38 and Deuteronomy 22:12 specifically required Jewish men to wear tassels on the corners of their garments with an interwoven blue thread. During New Testament times, this injunction was fulfilled by the addition of tassels (tzitzit) to the four corners of the himation, or outer mantle. The prayer shawl (tallit) developed in postbiblical times as a way of continuing to keep this commandment even after men stopped wearing four-cornered clothing layers. Such archaeological details are difficult to trace in the ancient world, but at Masada, a small fragment of cloth with the special woven-in blue (tekhelet) of these shawls has been found, and a bundle apparently meant to be used as tassels came from the Cave of Letters.

Another evidence of people keeping to the Law comes from the excavations at Masada: in every instance, clothing fragments were made of a single type of thread: either linen or wool, but never a mix (sha’atnez) of the two. Combinations of linen and wool were common in the ancient world (and the homespun “linsey-woolsey” of recent centuries continued this tradition) but were forbidden in Mosaic law: Leviticus 19:19 and Deuteronomy 22:11 both prohibit the mixing of woollen and linen. The clothing at Masada seems to have avoided such mixing, despite being of high quality and including items imported from regions beyond Judea. At the Cave of Letters, textiles were found in which the weaver’s mark, a small design sewn with woollen thread onto linen cloth, had been picked out, in order to preserve the single-type purity of the cloth. Both of these finds demonstrate that Jews of the period of the New Testament observed the rule of avoiding the mixture of diverse types of threads. Christians, however, especially once Christianity had moved beyond its Judaic origins by accepting non-Jewish converts, had no such Mosaic scruples: many early Christian burials in Egypt contain cloth of mixed wool and linen, most often using linen as the warp and colored wool as the weft threads.

The archaeological jackpot at Qumran, site of the find of the Dead Sea Scrolls, less famously included linen wrappings for the sacred books. The majority of each wrapping was undyed, but the portions with blue dye may have had a protective or symbolic meaning. The prohibition on mixed threads was applied here, as well, with the result that the color was a less intense hue, due to the resistance of linen to dyestuffs. Once these purpose-woven cloths had been used to protect sacred books, they could no longer simply be discarded, so they were placed in the caves with the scriptures and subsequently preserved in the undisturbed dry heat.

Apparently gendered clothing distinctions mattered enough in the law that cross-dressing was prohibited (Deuteronomy 22:5). Such a prohibition makes it clear that according to the law, a person’s gender could be––and should be––distinguished by their clothing. By New Testament times, men’s and women’s clothing differed not in type––a tunic for either was constructed in the same way––but in color and length. Women wore more brightly colored garments, while men were expected to dress in more muted tones. Women’s hair should always be covered, while men’s did not have to be. A woman’s tunic extended to her feet, while a working man’s tunic was only knee-length. When men wore longer tunics, it signaled higher status, beyond the roles of daily work. Thus, Jesus criticized the scribes “which love to go in long clothing” (Mark 12:38) as part of their assumption of social superiority, while the “long white garment” (Mark 16:5) of the angel waiting in Christ’s tomb, and Christ’s postmortal description as one “clothed with a garment down to the foot” (Revelation 1:13) indicated a supernatural being whose situation was beyond mortal cares. In comparison, when the prophet Elijah ran before King Ahab, he first “girded up his loins” (1 Kings 18:46), whereby he tucked the tail of his tunic inside his belt to be able to move easily without his clothing getting in the way. The concept of having loins girded, thus ready for movement and labor, contrasts with the long robes of the rulers and would-be rulers whose wealth and status and clothing choices were meant for leisure.

Jesus and his followers knew the Old Testament well, and aspects of clothing culture run through all of those stories. From the little coat that Hannah sewed and delivered annually to her prophet son Samuel at the temple (1 Samuel 2:19) to Tamar’s symbolic act of tearing her royal “garment of divers[e] colours” once she had been raped (2 Samuel 13:18–19); from King David’s change of clothes signifying the end of mourning his baby’s death (2 Samuel 12:20) to his high-flying linen ephod that distressed his wife Michal (2 Samuel 6:14), biblical clothing communicated messages beyond function for warmth and protection. Clothing was used to delineate status, as disguise to hide status or alter relationships, as part of a legal setting, and to show emotions and interactions with the divine.

As in most societies, the cost, quality, and style of clothing indicated rank in the biblical world. When Haman was asked to imagine the highest honor possible for King Ahasuerus to bestow, his first suggestion was that “the royal apparel be brought which the king useth to wear” (Esther 6:8), which was then ironically put on his nemesis, Mordecai. Clothing Daniel “with scarlet” (Daniel 5:29) and a gold necklace announced his role as third ruler in Belshazzar’s kingdom. In Tamar’s situation referenced above, a virgin in the king’s court was allowed to wear a special garment that showed her marital eligibility, and tearing and removing that was a reflection of Tamar’s physical attack and changed situation. For teenage Joseph, his prime position as firstborn son of Jacob’s favorite wife, Rachel, was clearly demonstrated by Jacob’s homemade gift of “a coat of many colours” (Genesis 37:3; the Hebrew word indicates a decorated, possibly long-sleeved robe). This coat, later to be mutilated by the brothers as part of their deceit, led to Joseph’s kidnapping and eventual future in Egypt. When David cut off a corner of King Saul’s robe rather than assassinate him (1 Samuel 24:4–11), he sent a message about his respect for authority but also about Saul’s vulnerability and David’s mercy. War failure was even vividly shown by wardrobe decisions: once when the Israelites lost a battle, the victors shamed the soldiers by shaving half their beards and sending them home with their clothes half cut off (2 Samuel 10:4).

Since clothing was such a societal marker, its misuse was frequent in scripture as an act of deception. In the early patriarch stories of Genesis, this comes up generation after generation: Jacob used his brother Esau’s clothes to confuse his aging and blind father, Isaac, into giving him the birthright blessings (Genesis 27:27). Then Jacob himself was hoodwinked at his wedding to Rachel when “in the morning, behold, it was Leah” instead (Genesis 29:25). Joseph’s brothers put goat’s blood on his coat to make Jacob think his son was dead (Genesis 37:31–32). Tamar conceived twins by her father-in-law Judah, Joseph’s brother, when she posed as harlot by removing her widow’s garments and covering herself with a veil (Genesis 38:14). Royalty occasionally preferred not to be known as such: King Josiah disguised himself as a common soldier to participate in battle, which led to his untimely death (2 Chronicles 35:22); King Saul “disguised himself, and put on other raiment” to consult a witch (1 Samuel 28:8); and King Jeroboam’s wife was sent to the prophet Ahijah in a futile disguise (1 Kings 14:2). The Israelite settlers were deceived into a problematic treaty by an entire group’s clothing when the neighboring Gibeonites pretended to have journeyed from a distant land wearing old shoes and old garments (Joshua 9:4–6). The Book of Mormon account also begins with a story rooted in Jerusalem and this pattern of biblical clothing disguise when Nephi “took the garments of Laban and put them upon [his] own body” (1 Nephi 4:19), which, on that dark evening, fooled not only Laban’s servant Zoram but also Nephi’s own brothers.

Functioning as part of communal customs, clothing was a component of ancient legal transactions and covenantal relationships. Jonathan gave David his robe, garments, and weapons (1 Samuel 18:3–4) to cement their covenant of friendship. Boaz covered Ruth with his skirt and gave up his shoe in both a personal promise and a legal testimony that demonstrated his intention to marry her (Ruth 3:9, 4:7). After Joseph lost his coat and family, his story continued in Egypt where another chapter of his story pivoted on the evidence of a lost garment that Potiphar’s wife held up as proof that he had attempted to seduce her (Genesis 39:12). Clothing is also detailed in the Old Testament as part of war plunder, obligatory donations, and prison uniforms (Jeremiah 52:33).

Beyond earthly social mores and authority, clothing played a part in interactions with the divine. Moses removed his shoes to show reverence (Exodus 3:5), and temple clothing was a vital part of worship and holiness. Passover celebrations were to be eaten while dressed for departure (Exodus 12:11), which makes the angel’s instructions to Peter in Acts 12:8 to dress hastily on that Passover occasion even more relevant. The Lord showed his power through clothing: making wardrobes last miraculously through the forty years of wilderness wandering (Deuteronomy 8:4) and preserving lives and clothing to emerge unscathed from Nebuchadnezzar’s fiery furnace (Daniel 3:21, 27). Prophets used clothing items to symbolize the fate of nations: Jeremiah followed the Lord’s instructions to wear an unwashed linen belt and then hide it (Jeremiah 13:1–11), Isaiah spent three years dressed like a slave at the Lord’s command (Isaiah 20:2–3).

Clothing could also be used as a vehicle to express strong internal emotions. When the prophet Elijah’s mantle descended on Elisha at his departure, it was an indication of the transfer of prophetic authority (2 Kings 2:12–14), and Elisha tore his own clothes in mourning and to symbolize that his former position was no more. With this powerful way to show grief, at least ten Old Testament characters tore their clothes, both men and women, from Reuben to King David to Mordecai to Athaliah. In the New Testament this occurs as well, when Paul and Barnabas, both raised as Jews, rend their clothes to protest false worship in Lystra (Acts 14:14). Joel 2:13 prefigured Christ’s message of internal change rather than mere external compliance, urging the people to “rend your heart, and not your garments, and turn unto the Lord your God.”

Priestly Robes

Not only was clothing part of interactions with the divine, it had elements spelled out by God particularly for those interactions. Priests were substitutes for Deity in the temples, so their appearance was intended to be otherworldly, and every object in the temple, including clothing, was set apart and sanctified only for temple usage. Guidance for the priestly wardrobe is extensive in the law of Moses. While little is written about the clothing required for later priests in Herod’s Temple, they would have followed the ancient prescriptions as closely as possible. Thus the following guidelines, written centuries earlier, would have applied to Caiphas, Annas, and Zacharias as they carried out their various temple duties.

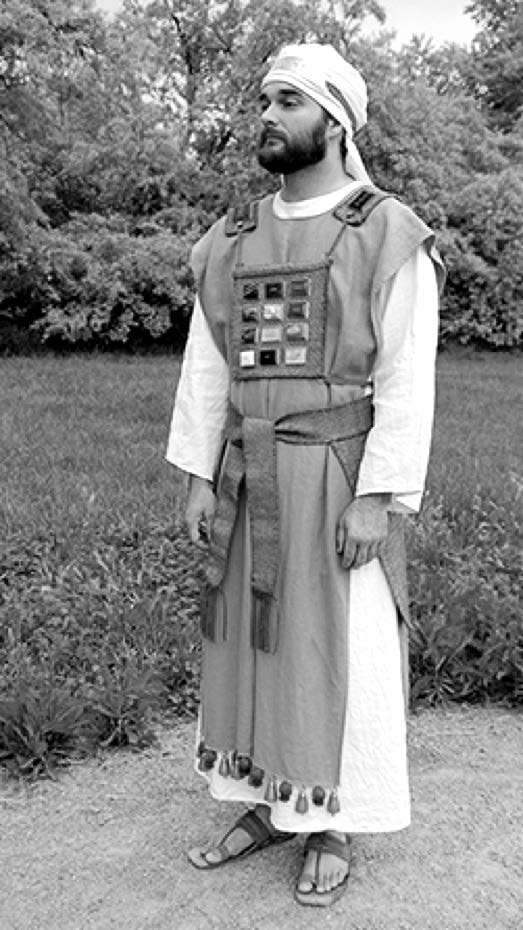

Exodus 28 proclaims that the clothes of the priests are to be for glory and beauty, and details how the ordinary priest wears a hat, belt, pants, and tunic, with the high priest adding the breastplate, ephod, robe, and golden headband to the outfit. The pants and tunic are made of white linen, the hat was a fabric strip wound around the head, and the belt woven with four threads: fine white linen, blue, purple, and scarlet. The sleeveless robe was woven of blue threads with a hem of decorative pomegranates and golden bells. The expensive golden breastplate would have served to mark out the priest wearing it as a singularly important servant of God. He symbolically carried the twelve tribes of Israel before the Lord by means of the named jewels adorning it. The headband was fastened in place by blue thread, and said “holiness to the Lord,” dedicating the priest and the people to God.

While the Bible does not specify

While the Bible does not specify

every aspect of the high priest’s

wardrobe, this recent replication

follows as many details as are given in the Old Testament descriptions.

Rules dictated how the priestly clothing was to be treated, laundered (imagine how the required animal sacrifices would have soiled the white robes), and recycled, with elaborate symbolism and tradition growing up around each element of that process. The priests’ clothing was first worn after a ritual anointing and blessing (Exodus 40:13). The high priest was forbidden from going about with a bare head or from tearing his clothes (Leviticus 21:10); it is thus intriguing that Matthew records that during Jesus’s trial the high priest broke that law and “rent his clothes” as he charged Christ with blasphemy (Matthew 26:65). Ezekiel foresaw a future heavenly temple where the priests were clothed only in linen, with no wool allowed (Ezekiel 44:17). Of course, Jesus as the great High Priest was prefigured by these images and ideas.

The priestly religious regalia symbolized righteousness, majesty, and divine power, as a number of scriptures indicate: “Let thy priests be clothed with righteousness” (Psalm 132:9); “Thou [Lord] art clothed with honour and majesty” (Psalm 104:1); “[God] hath clothed me with the garments of salvation, he hath covered me with the robe of righteousness” (Isaiah 61:10). Ezekiel used clothing as a metaphor for God’s magnificent bounty and care as the Lord symbolically dressed and provided for his adulterous bride Jerusalem: “I clothed thee also with broidered work, and shod thee with badgers’ skin, and I girded thee about with fine linen, and I covered thee with silk” (Ezekiel 16:10). And Isaiah reassured the mourners in Zion that restoration would bring “the garment of praise for the spirit of heaviness” (Isaiah 61:3), allowing a wardrobe shift to indicate the promised joy. This idea is carried forward into the New Testament, as everyone who overcomes the world would be “clothed in white raiment” (Revelation 3:5), making one and all heavenly priests.

Apart from the temple priests, other groups of highly religious Jews who wanted to distinguish themselves from one another did so in part through their apparel. Essenes dressed in simple white linen clothing, perhaps likening themselves to a community of temple priests. The aristocratic Sadducees, purportedly descendants of the priestly Zadokites, would have donned ritual robes if serving in temple duties. Pharisees, the fraternity to which Paul belonged and whose descendants became the Jews of rabbinic times, wore clothing that was distinctive and recognizable, and even criticized by Jesus: “they make large their phylacteries [tefillin], and enlarge the borders of their garments” (Matthew 23:5). Tefillin, leather straps connecting miniature boxes of scripture to be worn on the body, were created as the literal way to honor Deuteronomy 6:4–9 and keep the law before one’s eyes and next to one’s heart continually.

Temple Veil

When the ancient temple was built, Exodus 26 specified its various curtains of fine-twined linen, goat’s hair, embroidered hangings, and especially a blue, purple, and scarlet veil made of “fine-twined linen of cunning work” (Exodus 26:31) that would delineate and protect the Holy of Holies as sacred space. It was embroidered with cherubim, angelic figures. The temple veil was about sixty feet high and thirty feet wide. This is the veil that was torn in half from top to bottom at Jesus’ crucifixion (Matthew 27:51), symbolizing that through Christ’s death, the presence of God was now accessible to all (Hebrews 6:19–20). Doctrine and Covenants 101:23 suggests that the Lord himself is still veiled, or covered, until the Second Coming, at which time he will be revealed in all his power and majesty.

New Testament Threads from Christ’s Life

From the babe in swaddling bands, through his burial in linen clothes in the garden tomb, to his prophesied return in “dyed garments” (Doctrine and Covenants 133:46), Jesus was clothed in a physical body that wore particular fabrics. Clothing is an element of his sermons, his parables, his miracles, his transfiguration, his crucifixion and resurrection, and his glorified return.

Mary “wrapped him in swaddling clothes” (Luke 2:7), which were not the rags of Nativity art but rather narrow bands common to all well-cared for infants, made for that purpose and perhaps even embroidered with lineage identifications.[4] Such swaddling bands foreshadowed his eventual ministry of binding up the broken, and his burial wrapped in a tomb.

A powerful healing miracle recorded by three Gospel writers (Matthew 9:20–22, Mark 5:27–30, Luke 8:43–46) pertained to Jesus’s clothes. The woman with an issue of blood had faith that “if I may touch but his clothes, I shall be whole” (Mark 5:28). Luke adds the detail that she “came behind him, and touched the border of his garment” (Luke 8:44). This border was likely the wool tassel fringe (tzitzit) required by Numbers 15:38 to remind Jews of the law. Such an identification allows for the beautiful fulfillment of the prophecy in Malachi 4:2 that the Lord will bring “healing in his wings” (‘wings’ is from the Hebrew word kanaph, which also means border of a garment). This woman may have been remembering the miraculous power found in Elijah’s mantle (2 Kings 2:8), later echoed in Paul’s healing miracles of Acts 19:12, where “handkerchiefs or aprons” were brought from his body to the sick (and repeated by Joseph Smith with his red silk handkerchief in Nauvoo).

For the peasant fishermen who accompanied Jesus to the Mount of Transfiguration, the change in his raiment there was unforgettably otherworldly. Matthew described it as “white as the light” (17:2), Luke records that it was “white and glistering [Greek exastrapto: to flash out like lightning, be radiant]” (9:29), and Mark says that “his raiment became shining, exceeding white as snow” (9:3). Joseph Smith’s modern encounters with heavenly beings also recorded that their “brightness and glory defy all description” (Joseph Smith—History 1:17).

Burial Garments

Textiles play multiple roles in the central event of the New Testament, the crucifixion and resurrection of Christ. From dressing Christ as a king, ironically proclaiming his true status through their mockery (John 19:2–5), to soldiers gambling over who would be allowed to keep his clothing (Luke 23:34, John 19:23–24), to the angelic heralds in “shining garments” (Luke 24:4) announcing Christ’s resurrection, the everyday reality of the importance of clothing was never forgotten, even in this most mournful––and joyful––of moments.

Christ’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, at the start of his momentous holy week, had important textile details: he sat upon a young donkey covered with two of his disciples’ garments as a saddle (Luke 19:35) and was welcomed by multitudes who lay down palm branches and “spread their garments in the way” (Matthew 21:8). Later, he had performed a tender symbolic service to his apostles when he “laid aside his garments; and took a towel, and girded himself” (John 13:4) to prepare to wash their feet. This towel (Greek lention) was a linen cloth of a type worn by servants but also used to cover nakedness during crucifixion, thus prefiguring his upcoming death.

As part of his trial and its related torment, Jesus’ clothes were again removed. His scourged, bloody body was dressed in royal mockery, with a purple or scarlet robe described by Luke as “gorgeous” (23:11) and a braided crown of thorns (Matthew 27:28–29; Mark 15:17; John 19:2–3). Mark reports that after the mockery, “they took off the purple from him, and put his own clothes on him” (15:20) en route to the crucifixion. However, these were again removed at the cross and the soldiers cast lots to divide his clothing. Jesus had an unusual coat (chiton), described by John as “without seam, woven from the top throughout” (19:23). A Judean tunic was usually woven of two pieces held together at the shoulders, but this kind Jesus wore was more common in Egypt and required the use of a wider loom. The prophecy in Psalm 22:18 was thus fulfilled: “They part my garments among them, and cast lots upon my vesture.”

In the first century AD, the final burial could take place right after death (“primary” burial) or be delayed until only the bones remained (“secondary” burial). Primary burial was an especially costly business, requiring not only a full sepulcher for the body, rather than a smaller ossuary for the bones alone, but also the expense of linen in which to wrap the person being buried. Burials described in the New Testament are primary, with an accompanying need for linen to wrap and complete the burial.

After his death, Jesus was buried in a borrowed tomb. On this point, all four Gospels agree. Details of the wrapping of the body, however, differ. In preparation for burial, Joseph of Arimathea wrapped Jesus’ body in a “clean linen cloth” according to Matthew 27:59. This description is notable for what it does not say: the tomb itself is described, in the following phrase, as “new,” but the linen is merely clean. Mark, however, states that Joseph of Arimathea went out “and he bought fine linen . . . and wrapped him in the linen” (Mark 15:46). Bought for the occasion by a man of wealth, this linen would most likely have been new. Luke cannot settle the question: he does not state anything more definite than that linen was used for the wrapping (Luke 23:53). John, however, gives a new set of details: whether new or used, the linen was accompanied by a significant quantity of unguents and spices. Jesus’s close followers then “wound [his body] in linen clothes with the spices” (John 19:39–40). John ends this recital of facts with this tantalizing but incomplete editorial: all of this was done “as the manner of the Jews is to bury.”

The burial of Lazarus gives us a little more information: according to John 11:44, Lazarus (and presumably all people buried after “the manner of the Jews”) had his hands and feet “bound . . . with graveclothes” and his face covered with a “napkin.” The “napkin” that covered the face was a simple towel. The Greek soudarion refers to the equivalent of a modern handkerchief: a cloth used for wiping away sweat and blowing the nose. The graveclothes (keiria) mentioned here could have been purpose-woven for use in burial––the term implies narrow linen bands used to bind up a corpse after it has been wrapped in shrouds––or torn strips of linen taken from existing cloth. Parallels of both kinds have been found in great quantities in Egyptian burials.[5]

When Lazarus miraculously returned to life, he was still bound hand and foot with his burial wrappings, and presumably came stumbling and blind from the tomb. Jesus, on the other hand, had a thorough transformation. Thus, clothing culture enriches the symbolism that brackets the birth and death of Christ: wrapped in linen both in birth and in death, his resurrection included a complete change of his earthly body into something transcendent, accompanied by a total change of garb. His burial clothes remained in the tomb, neatly folded and left behind (John 20:6–7; Luke 24:12). The angelic visitors who guarded the tomb and informed its visitors of Christ’s whereabouts were notably arrayed in shining white garments. Could such brilliant white garb (Matthew 28:3) be an extension and symbolic transformation of the undyed linen of burial clothing?

Conclusions

Clothing is personal yet social. It both reflects and creates our social identity. Wardrobe variations, from top to bottom, from inner to outer layers, from season to season and year to year, are layered and multifaceted, but we, as humans bound by social traditions, know how to understand the many unspoken messages sent by each variation. These highly visible signals allow us to classify people by age, gender, status, career, wealth, and historical era.

Clothing is superficial yet universal. James recognized the ungodly but common tendency to use those very social signifiers listed above as indications of a person’s complete worth. He warned his church assembly not to afford more “respect of persons” to those wearing “goodly apparel” than those in “vile raiment” (James 2:1–4). Isaiah likewise warned against extravagant artifice in women’s adornment (Isaiah 3:16–24), and similar apostolic concern is found in 1 Timothy 2:9. Galatians 3:27 pleads with the newly converted to avoid all divisions and distinctions, but rather to “put on Christ.”

Clothing is essential yet fleeting. Job wryly noted, “Naked came I out of my mother’s womb, and naked shall I return thither” (Job 1:21), but for each step in between, the proper clothing for every occasion is socially assigned. This short survey has shown that in New Testament times, despite a more limited wardrobe vocabulary than is available in modern times, people were able to discern sharp social divides based on sartorial distinctions. Jesus, in his teachings, parables, and symbolic actions, made frequent and effective use of these common threads.

Clothing is eternal yet ever changing. Throughout history, images of scriptural people have been clothed in the wardrobe ideas of the time that the art is made. This human tendency attests to the changeable nature of fashion but also to our impulse to “liken all scriptures unto us” (1 Nephi 19:23). When we can see scripture characters dressed like us, we can use their clothing to symbolically ascribe to them attributes that dress naturally conveys: modesty and moderation; affluence and arrogance; poverty and humility; occupation, marital, or spiritual status. Adorned in clothing like us, they are more readily understood in our time and in our terms. Perhaps, in this way, we naturally follow Christ’s admonition to clothe the stranger: by placing historical, scriptural strangers in a familiar setting, we come to understand and love them as our neighbors. The ultimate promise of eternal life and of the New Testament is that God will clothe us, if we seek first his kingdom and righteousness, more gloriously than Edenic garments of skin, and more beautifully than the lilies of the field (Matthew 6:28–34).

Further Reading

Barag, Dan, et al. Masada. Israel Exploration Society, 1994.

The official report for the excavations at Masada, including an extensive and authoritative section on the textiles.

Gaspa, Salvatore et al. Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD. Zea E-Books, 2017.

Excellent articles explaining the connection between ancient terms and the clothing they referenced.

Geikie, Cunningham. The Holy Land and the Bible: A Book of Scripture Illustrations Gathered in Palestine. Vol. 1, J. B. Alden, 1888.

“Modern” nineteenth-century observations of daily life in the Holy Land.

Markoe, Glenn, ed.. Petra Rediscovered: The Lost City of the Nabataeans. Harry N. Abrams in Association with the Cincinnati Art Museum, 2003.

Excavations at Khirbet Qazone and the textile finds there.

Nielsen, Donna B. The Holy Child Jesus: Notes on the Nativity. CD-ROM.

Suggestions regarding swaddling bands.

Schrenk, Sabine, ed. Textiles in Situ: Their Find Spots in Egypt and Neighbouring Countries in the First Millennium CE. Abegg-Stiftung, 2006.

Articles on excavated textiles from the Cave of Letters, the Negev, and southern Jordan.

Sebesta, Judith L. and Larissa Bonfante, editors. The World of Roman Costume. University of Wisconsin Press, 2001.

Josephus, Talmud, and Midrash references.

South, Kristin H. and Kerry Muhlestein. “Regarding Ribbons: The Spread and Use of Narrow Purpose-Woven Bands in Late-Roman Egyptian Burials.” In Drawing the Threads Together: Textiles and Footwear of the First Millennium AD from Egypt. Tielt, Belgium: Lannoo Publishers, 2013.

Discussion of archaeological finds from early Christian burials in Egypt.

Notes

[1] Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae 5.26.

[2] Epistle to Diognetus 6.4.

[3] Tertullian, On the Apparel of Women 2.13.

[4] The New Revised Standard Version renders Luke 2:7 as “band of cloth.”

[5] Purpose-woven burial tapes in Egypt were sometimes made of a mixture of undyed- and red-stained linen. Such red and undyed burial tapes came to be directly associated with Christian burials in Nubia by the sixth century AD and may have symbolically referenced blood or had a connection with the “scarlet thread” that saved Rahab and her family (Joshua 2:18). In the modern Christian (Coptic) church in Egypt, a red ribbon plays an important symbolic role in baptisms and marriages.